Holding the Baby

Milk, sweat and tears from the frontline of motherhood

nELL FRiZZELL

PENGUIN BOOK S

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases names of people, places, dates, sequences and the detail of events have been changed to protect the privacy of others. The information in this book has been compiled as general guidance on the specific subjects addressed. It is not a substitute and not to be relied on for medical, healthcare or pharmaceutical professional advice. Please consult your GP before changing, stopping or starting any medical treatment. So far as the author is aware, the information given is correct and up to date as at time of printing. Practice, laws and regulations all change and the reader should obtain up-to-date professional advice on any such issues. The author and publishers disclaim, as far as the law allows, any liability arising directly or indirectly from the use or misuse of the information contained in this book.

TRANSWORLD PUBLISHERS

Penguin Random House, One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London sw11 7bw www.penguin.co.uk

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by Bantam an imprint of Transworld Publishers Penguin paperback edition published 2024

Copyright © Nell Frizzell 2023

Illustrations © Becky Barnicoat 2023

Nell Frizzell has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

As of the time of initial publication, the URLs displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Transworld Publishers is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Transworld Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

isbn

9781529176834

Typeset in 12/14.5pt Bembo Book MT Pro by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin d02 yh68.

Penguin Random House is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

1

To the National Health Service. And to my son.

Contents 1 How long will I feel like this? 1 2 Are parents the most tired people alive? 13 3 Should I buy a free-standing, self-swinging robotic hammock? 33 4 Why am I so lonely? 34 5 Hey, is this normal? 50 6 When should I have sex again? 53 7 Will a £49.99 rotating animal mobile really stimulate my baby’s senses? 71 8 Aren’t all mothers working mothers? 72 9 Why are pets more acceptable than babies? 89 10 How often should I wash my baby? 98 11 Can my child survive on pasta, cheese and peas? 99 12 Am I losing my mind? 102 13 Should I let my child put things off the floor in their mouth? 124 14 When did my home start feeling like a prison? 125 15 When is it safe to put a baby in a swing? 141 16 Why am I so angry all the time? 143 17 What about men? What can they do? 157

Viii nELL FRiZZELL 18 Is it safe to move my body in public? 159 19 Baby, are we born this way? 174 20 What happened to all my friends? 178 21 Should I clean my house? 191 22 Why am I crying? 204 23 Why am I back in my hometown? 206 24 Has becoming a parent ruined my relationship? 215 25 How should I talk to unpregnant people? 219 26 Is my toddler a psychopath? 236 27 How do I get this kid off my tits? 238 28 Baby concrete: would you like the recipe? 251 29 Should I have another baby? 253 30 Should I let my child watch television? 268 31 Why is childcare so expensive? 270 32 So, what’s the answer? 294 33 What next? 315 Exclusive Paperback Chapter: What Makes a Good Mother? 324 More resources 329 Notes and sources 333 Acknowledgements 339

How long will I feel like this?

Standing on the overground, surrounded by the inky dark of night, smelling of perfume, with a bottle of sparkling wine in my bag and not a single wet wipe about my person, I was hit by one thought like an absolute body blow: nobody on this whole train can even tell I’m a mother.

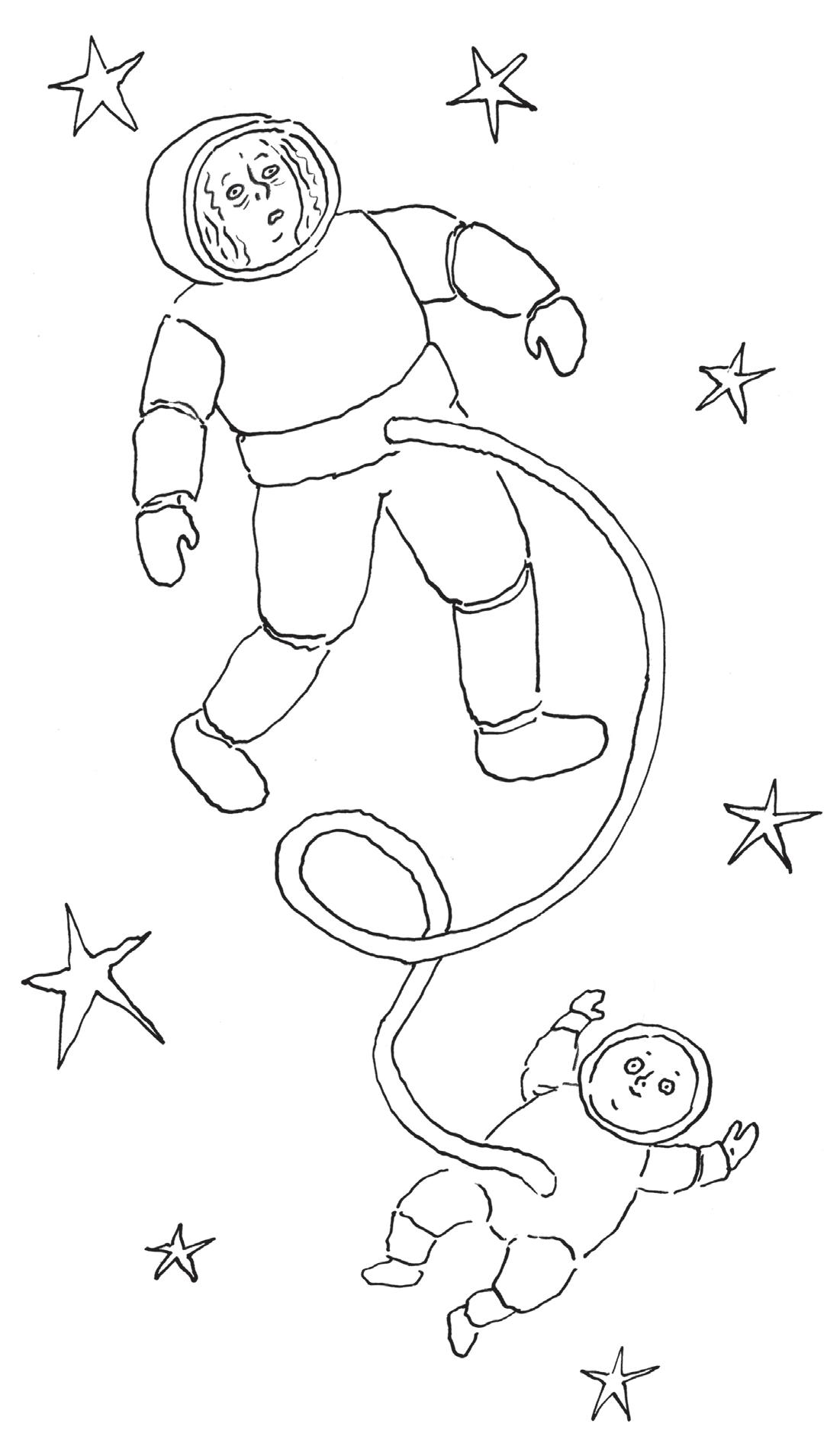

It was the first time I had left my little corner of London, at night, for over a year. As the orange train snaked through the sky above Dalston, Highbury and Canonbury, I felt like an astronaut, floating away from my base. I was hung, suspended, between excitement, fear, liberation and guilt. It was my friend Sarah’s birthday and, having a tiny baby of her own, she’d organized a drinks party at her house with the theme of ‘pyjamas and sequins’. ‘Wear a ballgown or your nightie, but nothing in between,’ she’d written to a WhatsApp group made up of friends, mothers, women from her children’s school and me – her wild-camping and outdoor-swimming

1

partner. So there I was, leaning up against the train door, in a pair of black satin pyjamas, a clatter of gold jewellery and a pair of six-inch multicoloured platform heels I’d bought for £10 from a stall on Ridley Road market.

I looked up and down the carriage at people checking their phones, doing their makeup, staring out of the window and reading free newspapers caked in train dust. Then I looked down at my flat front, my small handbag, my empty arms. There was nothing to indicate that I had just undergone the most considerable transformation of my life. No badge, no sling, no buggy, no bump. Breastmilk was gathering quietly beneath my skin – I could feel the tingle of my breasts filling up, like pins, like someone preparing a water bomb. But nothing about the sight or smell of me suggested that I was still growing a person with my body. From the way I was standing, nobody could tell that I had only recently knelt in a pool of lukewarm water and heaved a baby through my pelvis, feeling his elbows and knees knock against my ribs on the way out.

The man sitting in the priority seat playing Candy Crush had no idea that I had saved a child’s life today, when my son tried to throw a stick into the river and very nearly toppled in head-first. The love, fear, insomnia, short-term memory loss, stripped bones, hallucinogenic tiredness, fight-or-flight responses, milk production and hours of solitary confinement: nobody could see any of it. Unless I started screaming chapters of Wind in the Willows or pole-dancing on the handrail, none of these people would probably even notice I was here. And, of course, this being London, at night, on public transport, even those things were unlikely to draw much attention. How

hOLdinG ThE bAby 3

many of these people, I wondered, were parents? How many of us were secretly carrying the survival of another around in our bodies? How many were trying to slip a parental-shaped body into a public world? How many existed in a state of parental eclipse? And how long would I feel like this?

There is a phrase, coined by the US paediatrician Harvey Karp in 2002, that often gets tossed around online message boards and WhatsApp groups: the fourth trimester. This refers, in part, to the evolutionary theory that as our human ancestors learned to stand and walk – rather than clamber about on all fours like our ape cousins – we came up against a rather serious physical conundrum. Walking upright saved energy, left our hands free to pick up and grab and eventually use tools. But it also narrowed our hips, as our centre of gravity shifted to just above our legs. At the same time, our brains started to grow exponentially. Over three million years, the human brain quadrupled in size. Which brings us to the conundrum: how can a narrow-hipped, bipedal mammal give birth to a baby with a huge skull protecting a useful but massive brain? If humans gave birth at the same stage of foetal development as chimps, every labour would rip the mother to death. Even now, as Bill Bryson points out in his book The Body, the average baby’s head is one inch larger than the average woman’s birth canal. A measurement he calls ‘the most painful inch in history’. And, as we know, babies – even those pea-brained, hairy monkey babies seen in David Attenborough documentaries – need their milk-giving mothers in order to survive at first. Which meant it was worth keeping us around. And, so the theory goes, we started

4 nELL FRiZZELL

to give birth earlier and earlier – to babies whose skulls had not yet fully fused into solid bone. To babies that cannot focus, or control their head, or sit up or do much of anything but scream and sob and sleep. While this saved a birthing parent’s pelvis from being irrevocably torn apart, it means that new-born human babies are still, to a large extent, growing and functioning as if in utero. They must feed every couple of hours; their brains, bones and bodies will be growing at a considerable and energy-hungry rate; they will seek the comfort, warmth and familiar voice of their primary carer almost all the time. And so, suggests Harvey Karp, perhaps those first few months of a baby’s life should be considered a fourth trimester – a period during which a new-born slowly and sometimes painfully adjusts to life outside the womb, and the simple survival of a helpless infant is just about all its parent can concentrate on.

Except, it doesn’t just last three months.

Ask any woman who, nine months into motherhood, is still being woken every forty-five minutes throughout the night to feed a screaming baby. Ask any parent whose eleven-month-old child does not rest unless being rocked through the air like someone strapped into the Nemesis ride during a stag do at Alton Towers. Ask anyone who has ever begun to breastfeed while on a crowded train only to realize that their six-month-old baby has chosen that exact moment to evacuate a sack full of wet shit all over their lap. Ask a parent who has peeled a sobbing and screaming eighteen-month-old, who woke up at 4 a.m., off their leg in order to catch the bus to work. The period of crucial vulnerability in which a child’s development is significantly shaped by how you, as a parent, care for

hOLdinG ThE bAby 5

them can last – depending on the style and circumstances of your parenting – for years.

But let me come to my real point. While many health professionals, as well as large institutions like UNICEF and the National Childbirth Trust, have now adopted the phrase ‘The First Thousand Days’, to highlight the critical importance of our early existence on our long-term human health, there is no equivalent to refer to the same period in the mother or primary caregiver’s life. There is no name for what the parent is living through. Nothing. Your baby is a new-born, or a baby, or a toddler or a threenager. But you? You’re just a mother. Or a dad. The parent. A one-size-fits-all state that gives no clue as to how closely your child’s survival relies on you. No sense of how far you can move through the world without them. No hint as to how much of your time, identity, body and self is absorbed by the needs of your baby.

The problem with having no easily identifiable label for this postpartum period is that it allows employers, healthcare professionals, friends, partners and even new parents to treat it as something fleeting, inconvenient, wilfully chosen and therefore the responsibility of the individual to deal with. This then allows discrimination to grow up within our institutions, our offices, our homes, our friendships and our families like fungus between toes. It allows the age-old stereotypes, frustrations and excuses to bloom like algae. It slips the responsibility of keeping the nation alive into a no-man’sland between parents, partners, employers and the state. It allows those in the midst of it to be dismissed, ignored, short-changed and misunderstood until they have no option but to turn their fury inwards or fade out. It

6 nELL FRiZZELL

allows those who have taken a child-free path to feel shut out, judged, underestimated and out of sync. It contributes to the ongoing and exhausting game of top trumps – as seen most starkly during the Covid-19 lockdown – over who has it better, who’s getting off lightly and who is suffering most.

Despite the fact that 81 per cent of women today will have a baby by the time they turn forty-five, parenthood is often treated by popular culture, friends, employers and mainstream media as a private tributary, channelling people away from ‘real life’, until they eventually meander their way back some time around their children starting school. It is an individual slog, to be undertaken within the quiet confines of the home, rather than a shared cultural phenomenon and social responsibility. ‘Real life’ – the kind that deserves to be talked about in public – takes place in offices, pubs, on sports fields and on messy night-bus journeys home. ‘Real life’, we are told, involves money, status, suits, social media and the right kind of shopping. Whatever work, comedy and drama is happening in our homes, parks, playgrounds, bathrooms and hospitals, it isn’t ‘real life’. Instead, it’s treated as a private affair to be thought about only once we’re doing it ourselves, something to shy away from in pursuit of prolonged youth, or simply too prosaic, too sensitive or too niche to discuss in a public sphere. We may fetishize motherhood and regard parenting as an inevitability for most people, but we could do so much more to support new parents, rather than pushing them out into the slow, lonely, underpaid margins of life. By recognizing this period in all its technicolour, hilarious, revolting and frustrating glory, we could do so much to

hOLdinG ThE bAby 7

knit back together a strained society. Which is why even just writing about this time in vivid personal detail and with an eye to the wider context has felt like a political act. Interesting, strange and hilarious things are happening in our private hours. It is time to discuss these experiences with the clarity, wryness, consideration and camaraderie with which we once discussed first love, first jobs and first dates.

We needed a name. I needed a name. I needed the name to describe where I was, and everyone around me needed that name in order to recognize it. I wanted a phrase that would communicate to people the feeling of having slipped behind the monolith of motherhood. What happens when, as a parent, your light is almost totally absorbed by this new responsibility; your sense of self nearly obscured by this new identity. You’re still there, but you’re also out of sight. It felt, I realized, like a partial eclipse. That was the mechanism here; that was my experience. As my son pushed out of my body, the non-mothering Nell slipped, temporarily, into his shadow. But I also knew that while the partial eclipse can describe a feeling – my feeling – it was spicy. It was a name that would provoke anger, discomfort, disagreement in many people. People who do not like parenthood – particularly motherhood – to be characterized in this way. It would therefore be useful to have a name for the time itself – one that didn’t have the potential to push people away before I’d even set out my stall. Also, as a lifetime gag-hunter, I wanted a name that would make people laugh. Or at least smile.

I went for a cup of tea with a woman called Sharon. Sharon is a mixed-race, middle-aged psychotherapist and author, and mother of three grown-up children. So, not

8 nELL FRiZZELL

exactly my demographic, and all the better for it. As I discussed the idea – tried to sketch out this period I’d just lived through and how frustrated I felt by it having no common, named recognition – Sharon had smiled. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I called them the tracksuit years.’

The tracksuit years! It was brilliant. The hours of shapeless, absorbent, adrenaline-slick existence that, to the outside world, looks so often like nothing at all. The frenetic, indoor survival that is so easily misconstrued as cosiness. The transformation from button-fly, underwired, high-heeled public status to shapeless, private invisibility. ‘It was a phrase for the frustration at the time and it’s become a phrase of affection,’ said Sharon, her eyes glinting across the table. ‘For us, it wasn’t just to do with vomit everywhere and the practicalities of having no money. It was also about saying, “I used to have a life where I wore clothes.” ’

By tracing a line back through the tracksuit years, I want to ask some big questions. For example: what effect does parenting have on your career? Is health a private or public responsibility? If parenting is so hard, why does anyone ever do it more than once? How can we make childcare affordable and fit for purpose? How do we define the Family? Why do parents sometimes feel like they’ve moved to a whole new planet? What’s it like to, say, have your eggs harvested while listening to Sean Paul on the radio in a fertility clinic in the middle of a pandemic because you’ve decided to have a baby without a partner? (OK, well, that last one might be a tiny bit more specific, but it’s probably still worth asking.)

This is not a book of advice. It will not stop your baby crying, it will not help you save for a deposit or get a mortgage, it will not stop you making extraordinary cock-ups

hOLdinG ThE bAby 9

or introduce you to hot mums in your local area. But it will, hopefully, draw on research to point out the flaws in our system and advocate for a better alternative. It is a memoir, culminating in a manifesto. It is my story – a personal story – with all the detail and the drama I can conjure. It may look different to your story; it may challenge some of your assumptions and experiences; it may directly contradict what you think and feel and want. That is OK. We can still recognize our commonality and agree on what needs to improve. In order to build a movement, to achieve public recognition and to effect change, we don’t have to be the same: we need to unite.

Sitting on that train, my pupils like saucers from being out in the dark for almost the first time that year, my bag full of nothing but wine, keys and money, I felt a thrum of anxiety beneath the excitement. After dedicating months of sober, adrenaline-fuelled, sleepless attention to a fleshy, loaf-sized dictator, an adult let loose from their baby can have a tendency to lose their cool. How would I talk to a room full of strangers? How late would they all stay up? What would happen if my son woke at home? Would I start crying if I accidentally looked at my phone screensaver and caught a glimpse of him sitting in the bath, his hair like a pyramid of water weeds? Was it dangerous to be this physically far away from a stillbreastfeeding baby? What if I got hit by a car walking to her house and my partner became a single parent? It felt like I was pulling my son’s umbilical cord across the great night sky of north-east London, like the safety tether between space station and star sailor was becoming perilously stretched.

It was also strange to appear in public as a woman,

10 nELL FRiZZELL

rather than a mother. Of course, these two terms are not mutually exclusive, but they are, I think we can agree, different. At that moment, on that train, I didn’t feel like a woman – I felt like a mother. Only, my motherhood was temporarily invisible. I remember my friend Fia once telling me, when I was newly pregnant, that the first time her period came back after having her son she had been struck by a strange sense of loss. ‘Now I just have a regular body,’ she’d said as we sat in her garden drinking herbal tea. ‘I’m not pregnant, or breastfeeding, I don’t have a bump – everything’s just going back to normal.’ At the time, I had listened without completely understanding. Now, standing on that train, looking along the row of bowed heads, smelling the chemical tang of my perfume, the unexpected urge for a cigarette tingling through my bloodstream for the first time in years, I began to know what she’d meant. It is ever so slightly anticlimactic to feel your body returning to its former shape and status after having a baby. It is disconcerting, having undergone such an axis-shifting experience, to ‘pass’ for what many people would call a ‘normal’ woman. Without the physical signifiers of motherhood, how do you hold on to your new identity? Do you really want to? After months of being treated gently by strangers, given more room on buses, helped down steps and asked sometimes riotously intimate questions, it can be a little odd to realize that you’re now, quite literally, on your own. You’re just another person, fending for yourself. It’s true that there were times – usually when I was lugging an enormous rucksack full of muslins and spare clothes to a hospital appointment – when I longed to jettison the burden of motherhood and operate as a single

hOLdinG ThE bAby 11

unit again. But, like so many things in life, actually getting what you want can be unnerving.

As I type this, I am edging out from behind my eclipse. Three years after my son was born, my breasts are no longer full of milk, I have periods again, my hair has stopped falling out and I sleep through the night. I can run 10K without stopping, my belly is soft and empty, my face is etched with lines and I can hold in a piss. I am different. The transformation I’m calling the partial eclipse is, in most cases, temporary, profound and unique. It changes you and creates the future. It is familiar and it is extraordinary and it is happening to millions of people right now. To give this thing a shape, I will pull you through mine, via the bleary-eyed singalongs in overheated children’s centres and the bowls of sweaty pasta, the underpants that rolled out of my partner’s trouser leg in a midwife appointment and a choc ice in a thermos flask. There will be fish fingers, kicking trees, milkyfronted attempts at seduction, domestic maggots and a trip to IKEA. I will bring you into the hours I spent looking out of windows, trailing behind a buggy, staring into an empty sky and, eventually, cycling down the river to sleep alone in a wood.

So, how long will it feel like this? I can’t tell you. But I hope that by telling you how long I felt like this, I can prove that you’re not alone. And by exploring the questions that I reckoned with during the partial eclipse, I hope we can start to see this as a period of time that could be vastly improved, rather than as a struggle to be endured in private.

12 nELL FRiZZELL

Are parents the most tired people alive?

It’s dark. My heart is thundering. I am sitting like a uaver: slightly salty, slightly cheesy, curled away from the hard wall behind me. My neck is rigid and my lap is empty. I’m terrified. I cannot remember falling asleep. I cannot remember putting my son back into his cot beside me. I don’t remember winding him or lying him flat or even holding him at all. I have blacked out and, in that adrenaline-spiked split second between sleep and waking, I am convinced my son is dead. I see him – the entirety of the nightmare played out almost before I hit conscious thought – rolling on to the floor, unseen, into the dust beneath the bed. I imagine him kicked down the duvet as I lolled into sleep hours earlier. I picture him choked with vomit in the gap between our pillows.

I’ve had blackouts before – of course I have, I’m an absolute lad. I’ve woken up in my own bed, my face washed, my throat tasting like diesel, with absolutely no

2

memory of getting home. I’ve had to be reminded, moaning into a sofa cushion the next day, of things I’ve said and people I’ve startled while out dancing. I’ve lost coats and keys for ever. But in those cases I was always stag-wild drunk. They were accidental and queasy. They became the stuff of hen-night anecdote and fry-up entertainment.

These blackouts are different. They are pure and blank and edged on each side with fear. They take place sitting up, or while reading a letter from the council, or on a hard wood floor. As exhaustion overwhelms me, I feel myself falling, not just asleep but through space and between time and out of my body. I feel my neck turn soft, my eyes roll in the darkness. I lose any sense of having legs or bones or breath. As I feed my son, in the middle of the night, all I feel is the monotonous tug at my breasts and the unfurling of my arms. Losing hold. Catching myself just in time, I would bite the skin inside my mouth, hard, sometimes drawing blood, just to stay awake long enough to pull him off my nipple and lay him on to his bed.

Despite significant cultural changes over the last century – middle-class women’s entry into the jobs market, advanced understanding of biology, the 2010 Equality Act – we still have a painfully gendered attitude to tiredness in western culture. Staying awake for hours at a time is considered daring, selfless and physically impressive when it’s associated with, say, the military, being a financial trader or an endurance athlete – all areas still largely populated by men. But if the same level of fatigue or sleep deprivation is caused by being a nurse, a night cleaner or a breastfeeding parent – all activities still largely undertaken

14 nELL FRiZZELL

by women – then very few medals or financial bonuses get handed out. In short, male tiredness is lionized while female tiredness is ignored.

I remember one freezing, wind-blown morning in early 2018. I found myself walking around the Olympic Park in east London, pushing my son in his buggy in the hope that at least one of us would fall asleep (preferably him). He was wearing one of those padded suits that make all babies look like astronauts in pyjamas, huddled under a pale blue blanket sent to us in the post by my friend Didi. I was listening to This American Life in one ear, the other headphone tucked into my scarf in case, somehow, I missed hearing my son fatally choke right in front of me. Or a lorry tearing down the tarmac behind me. Or an eagle diving talons-first towards my buggy to claw off my son’s face. The kind of threats that rumble just below the surface of your paranoid, anxious brain as a new parent.

As I slowly rolled past a battalion of 6-foot-tall swan pedalos, I heard the radio producer Stephanie Foo explain that, despite initial suggestions that China or Russia had hacked their navigational equipment, the American navy now admitted that several lethal ship collisions at sea had been caused by the crew simply being sleep deprived. Foo spent four months researching the ‘you sleep when you’re dead’ macho culture of the US military, which belittled sailors for trying to sleep or simply put them on rotas that meant they couldn’t. Foo reacted with amazement to one sailor telling her that he once stayed awake for seventy-two hours. I listened as he described hitting the proverbial wall of exhaustion, the loss of motor skills, his problems focusing his vision, audio and visual

hOLdinG ThE bAby 15

hallucinations and finally, after two or three days, struggling to determine whether he was even awake or asleep. In low, serious tones, Foo explained that, on average, sailors were walking around on less than six and a half hours’ sleep per night; that being awake for twenty-three hours is equivalent to being well over the limit for drinkdriving; that on some tests they made twice as many mistakes. Even in my desolate, grey-whipped state, I remember fury rising within me, behind the handle of my son’s buggy. Less than six and a half hours? For a new parent or many other types of round-the-clock carers, six and a half hours is an eye-wateringly luxurious amount of sleep. At that time, pretty much every mother I knew had pushed through maybe twenty hours of wakefulness as a matter of course before embarking on another day of care work, paid work, housework and the fairly essential work of keeping their child alive. If being awake for twenty-three hours is the equivalent of being over the limit, then new parents are drunk a huge amount of the time.

The problem, of course, is not always that your child is awake – very few small babies stay awake for twenty or more hours a day (although it’s not unheard of). It is that, often, your whole ability to sleep is shattered by the experience of parenting a new- born; the physical upheaval of labour, which often involves staying up for thirty- six hours or more; the round- the- clock, possibly hourly need to feed; the fi ght- or- fl ight mode your body slips into in order to better respond to your baby’s immediate needs; the anxiety of knowing they could die on your watch; the need to remain tethered to the diurnal schedule of the mainstream world, with

16 nELL FRiZZELL

almost all midwife appointments, doctor’s appointments, work appointments and social appointments happening between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. despite the fact that you might have been awake all night; the pain of physical healing after birth, twinned with the mental adjustment to your new responsibilities. All of it is a recipe for losing the ability to sleep. Hopefully temporarily but who knows? In her sensational and vital memoir of postnatal mental illness, What Have I Done , Laura Dockrill describes how her inability to sleep during the fi rst few days of her son’s life contributed to an inexorable slide towards what was eventually diagnosed as postpartum psychosis: ‘One day I fed him for twenty- four hours straight.’ (Her son was born small, hungry and tongue- tied.) ‘I’m not telling you this so you can call me a hero. I’m telling you so you can see how sleep deprivation can help send you to madness.’

That morning I had had three hours’ sleep. I hadn’t slept from 9 p.m. to midnight or anything magical like that. Instead, my daily rest had been broken into a oneand-a-half-hour chunk and two subsequent, flickering naps. I had sat through hour upon hour of blank, orange-stained darkness from the street lights outside our flat, waiting, coiled like a spring, for my son to start screaming again. I was the kind of tired where your body starts to feel it’s made of gravel, yet is oddly liquid; like honey as it crystallizes. I felt like if I rubbed my eyes just a little too hard, my entire skull might implode like a meringue.

You do make terrible decisions when you’re this exhausted. Terrible, dangerous, painful, life-threatening, hilarious and unexpected decisions. Which could be

hOLdinG ThE bAby 17

avoided if we designed work, public services and social expectations to meet the needs of new mothers, rather than pressing them to plough on, fit in and bear the consequences. When I asked on Twitter for people’s worst tired-and-in-charge-of-a-child stories, the replies were wincingly, hilariously recognizable. I think my favourite came from Yasmin Wilde, who wrote: ‘I remember turning up at the local department store cafe, frazzled, ready for lunch after a long morning, with pram and toddler in tow, and asking for a jacket potato. “Sorry we can’t start serving them till 12.30,” the server said. “Oh, what time is it now?” I asked. “9.15.” ’ The idea of stumbling past makeup counters and pan sets and shelves full of lightbulbs after a 3.45 a.m. start, hungry and empty and desperate for the warmth and comfort of a baked potato, only to discover that the rest of the world is just finishing their morning coffee is a perfect example of the hollow, out-of-sync weirdness of this time. I also want to thank the woman who told me that she had two advent calendars the year her son was born: one for 4 a.m. and one for 7 a.m.

One man told me: ‘My wife went in to settle the baby at night, picked him up and tried to soothe him, only realizing after a minute that she was holding him upside down.’ A person called Sarah recounted: ‘A friend of mine finally got on top of her pile of washing – only to realize when she went to make up the next feed that she had been using scoops of formula instead of washing powder. Thank god she realized before trying to force her daughter to drink a bottle of non-bio.’ In a similar detergent vein, someone called Kate told me: ‘I was so tired with my first-born that twice in one week I brushed

18 nELL FRiZZELL

my teeth with hand soap rather than toothpaste. And didn’t realize what I had done until days later.’ Or Lucy Margolis, who ‘Put the kettle on after a night of three, perhaps four, minutes’ sleep. Sat on the sofa to feed the baby, took a sip of my cuppa . . . and realized I’d made it not with a teabag, but a dishwasher tablet. (This happened more than once.)’ My old school friend Kainde Manji has a story about reversing over her buggy in the car, just eight weeks after giving birth. Thankfully the baby was safely inside the car at the time. There were stories of trying to breastfeed pillows, feeding the same twin twice and the other not at all, and of pacing around the room trying to wind a jumper. Other replies were socially crippling, like the woman who wrote: ‘Someone asked me my daughter’s name when she was three months old and I forgot it, so I just said, “Baby.”’ Or Dr Carolyn Jess-Cooke, who wrote: ‘I once phoned a high-profile magazine I was writing for and asked a very confused receptionist for the results of my urine test.’

Now, reading back through those responses, you may notice something, as I did. That the kind of incidents we relate when discussing parental tiredness seem initially small, domestic, funny. Oh ho! Mummy’s put soap in her tea again! But actually, pretty much every single one speaks to the fact that real human health and life is frequently put at risk by chronic sleep-deprivation. Why do we do that? Why do we shrug these events off as embarrassing and unavoidable rather than dangerous and preventable? Well, if I may be so daring, perhaps because this is the kind of tiredness largely, and historically, experienced by low-status and marginalized people: women, disabled people, people on low incomes, people

hOLdinG ThE bAby 19

of colour, carers. I always think that, were the parent behaving bizarrely because of alcohol or drug intoxication at seven in the morning, there would be some justifiable concern from those around them. Meetings would be called. Social services might even be informed. But if they’re doing so out of a hallucinogenic lack of sleep, we all just sort of shrug it off as par for the course, something that can’t be helped.

So, yes, there was the father who pushed a meal tray covered in dirty dishes to the hospital changing room at two in the morning, rather than his daughter’s crib, or the woman who held a dirty nappy to her head while throwing her mobile phone in the bin. But there are also hallucinations without number: crying babies in the wallpaper, lost babies crawling out on to the roof, toddlers becoming dogs, duvets feeling like rocks. Not because the person in question had been diagnosed with postpartum psychosis (although it affects one in 500 people after birth) but because that’s what our brains do when we’re deliriously tired. And here’s the other thing: housework cock-ups are a pretty good indication that other kinds of accidents, mishaps and risks are also happening. Nearly feeding your new-born laundry detergent isn’t just a hilarious mix-up of white bottles (although I absolutely sympathize with the need to laugh it off as such, to protect your own sanity), it is the sort of thing that should prove to us that new parents need more help and support.

What about those parents who, after twenty-three hours of flickering, numbing wakefulness, fall asleep feeding, while their toddler walks out on to a balcony unsupervised? Or who temporarily pass out on a bench

20 nELL FRiZZELL

while their buggy slides into the road? Or who roll on to a sleeping new-born in the night? These are the stuff of horror stories but it is a horror story that we are currently allowing to play out behind front doors and eyelids across the country simply because we haven’t invested the time, money or creative thinking into finding another way to do things. Business, the military, Westminster and manufacturing industries may well write up reports and produce policies intended to reduce the sleep deprivation of their employees, with the intention of reducing human error, but there seems no equivalent push to address the sleep deprivation of new parents without whom – you guessed it – there would be no business, politics, military or manufacturing in the future.

Moreover, the fear of these things happening – of getting ‘caught’ or ‘found out’, of being so tired that you cannot adequately care for yourself or your child – adds to the pressure and anxiety felt by new parents, often making it harder to sleep even when it is considered safe to do so. I cannot tell you how many nights I lay awake, beside my son, vibrating with fear and worry that I would be too tired to look after him the next day. That the midwife would call the authorities. That I might be deemed a bad mother and have my baby taken away. We punish ourselves for being tired, are haunted by the spectre of something awful happening because of our tiredness, but when are we – the wider public – going to demand the kind of systematic change that would stop us getting so tired in the first place? We can’t leave it to new parents to sort out; they’re already busy.

After listening to Foo’s piece on This American Life, I read with a little trill of laughter that, according to their

hOLdinG ThE bAby 21

Comprehensive Crew Endurance Management Policy, signed off in December 2020, members of the US navy ‘must be given the opportunity to obtain a minimum of 7.5 hours of sleep per 24-hour day’, with either an uninterrupted 7.5 hours, or an uninterrupted six-hour sleep and uninterrupted 1.5-hour restorative nap. Otherwise, they claim, the risk to life and safety is considered gravely compromised. My god, what I would have done for 7.5 hours of uninterrupted sleep during the partial eclipse! I would have ripped out every one of my fingernails and walked naked down the M6 if it had meant just six hours of uninterrupted, unterrified sleep.

Like so many parents who have come before me, being deprived of sleep meant I lost vocabulary, my mood plummeted, my short-term memory effectively turned into a log flume to oblivion, I ate badly, the adrenaline coursing through my body gave me a sharp pulse of anxiety, I left tasks unfinished, I became slow and clumsy and distracted. For the first year of my son’s life – especially during those particularly gruelling sleep regressions that hit every few months – I was exhausted most of the time. When I was at the nadir of my sleeplessness I, to borrow a phrase from the Comprehensive Crew Endurance Management Policy, became less effective, had slower reaction times and struggled with making good decisions. All of which would be considered extremely dangerous if I were responsible for human life in a military setting, but was smilingly considered my lot when I was responsible for human life in a civilian, domestic setting.

The interesting thing is that, although we know the effects of not sleeping – and, guess what, they’re not good – there is still something of a scientific mystery

22 nELL FRiZZELL

about quite why sleep is so important to the healthy function of our bodies and minds. So, for example, Michael S. Jaffee, Vice-chair, Department of Neurology, University of Florida, can write that: ‘When we are sleep deprived, our bodies become more aroused through an enhanced sympathetic nervous system, known as “fight or flight.” ’ But quite why our body responds so differently to being conscious and being unconscious remains a question. Now, I don’t want to upset you when you’re tired so I won’t go into forensic detail here, but we do know that sleep deprivation increases blood pressure; that our endocrine system releases more of the stress hormone cortisol; that there is an increase in the hormone ghrelin and decrease in its counterpart lectin, which are associated with increased appetite; and that being deprived of sleep is associated with increased inflammation and decreased resistance to infection. uite why all these things occur is still unanswered but clearly, when your body is entering into a period of sleep deprivation, it responds chemically in a way that can, eventually, cause you quite serious harm. Not to mention the effect on your mind, mood and emotional health.

The actor and comedian Gabby Best has suffered from acute insomnia for over a decade. As she puts it, with years of surviving on an hour or two of sleep, she has been in training for having a new-born her whole life. ‘It made me slightly hysterical at times; quite neurotic,’ she tells me over the phone, her eight-week-old son Wilf burping gently in the background. ‘When you reach the end of a week of not sleeping, you have about 20 per cent of your personality; you’re just sort of vacant. Your memory goes, you’re forgetting words, turning up at the

hOLdinG ThE bAby 23

wrong place on the wrong day, so of course you’re full of self-doubt. You don’t trust yourself.’

Having seen her face all over Edinburgh during the festival a few years ago, I first met Gabby properly while teaching a creative writing course during the Zoom months of the Covid pandemic. She was interested in writing about the experience of chronic insomnia. ‘Although my not-sleeping now has quite a lovely purpose, with this, it’s constant, cumulative,’ she explains, talking about the 24-hour periods she has stayed entirely awake since having her son. ‘With insomnia, you’ll have a really brutal patch but then a period of recovery. And when I say a good night, I mean maybe five or six hours. But with this, you never have the chance to catch up.’ When I told her about the American navy and their seven hours, she made a noise somewhere between a howl and a yoghurt hitting a wall: ‘You’re not getting a fraction of that and you’re in charge of a person in every possible way! Carers have the worry to end all worries: has the person you are looking after died under your care? It’s such a big worry I can’t even quite look at it straight on. So you just deal with the logistics.’

Those nights, as I swam in and out of a slackening sense of unconsciousness, my breastfeeding child in my arms, I would place him, millimetre by millimetre, on to the mattress of his bedside travel cot, trying not to breathe too loudly, trying to quell the shaking of my over-extended muscles, watching his flickering eyelids with my breath held. And then, having creaked back to my own side of the bed, I would lie there. Awake. In the dark. Sometimes for hours. Because putting a child down to sleep is bomb disposal and I felt like I was trying to

24 nELL FRiZZELL

sleep on the frontline. The sheer level of adrenaline coursing through my body made it almost impossible to fall asleep, despite my delirious state of fatigue. My brain interpreted the presence of adrenaline as my being in danger; so it kept me awake in order that I wouldn’t unconsciously slip into greater danger. I was exhausted, god I was exhausted, but I was also coiled tight with fear: fear he’d die, fear I’d fall asleep on the job, fear of waking the entire block with his screams, fear I’d run out of milk through sheer physical exhaustion, fear that he would wake again and immediately start howling.

There are going to be people reading this who take issue. People who would chastise me for allowing a child to become so demanding, so irascible, such a dictator of my own physicality that I would have to edge my hands out from under his nappy inch by inch over the course of six minutes for fear that any movement might rouse him. These are often the parents of their third or fourth child. The ones who sling their fully awake baby into the nearest laundry basket or dog bed and walk away for an hour. ‘They’ll drop off soon enough,’ they chime, striding purposefully to the fridge. And it’s true, there are some children, some cottage loaves of gurgling easiness that will simply ‘drop off ’. Noise, light, movement, the honking of car horns, the slam of a front door will mean nothing to these drowsy infants. I once watched my friend Becs, standing in a beer garden, watching the football, pint in hand, chatting to her friends as her daughter Edie fell asleep in mid-air, hanging off Becs’s hip like a shelving bracket. I stared in disbelief. This was the equivalent of falling asleep beside a crank engine. Whether this was luck, training, a product of Becs’s own

hOLdinG ThE bAby 25

attitude, practice or genes, we’ll never know. But for most of us, or at least for most people at some point, the process of putting a baby down to sleep can last as long as the sleep itself.

Which leads me on to one of the most unhelpful phrases ever slammed into the sides of new parents’ heads like a frisbee: sleep when the baby sleeps. Oh how clever, you think. How neat. Of course, if, as the NHS suggests, a new-born sleeps for between eight and sixteen hours out of every twenty-four, then you’ll be able to nibble up a good eight just by conking out every time they close their thin-veiled, flower-petal eyelids. When after a feed or an exhausting few hours of waving its hands jerkily around its head the baby nods off, simply slip into a clean, cool bed and have yourself a little doze. Except, how can you? Because those little slices of silence are the only time you have even half a chance of doing absolutely anything else involved in being a functioning human. You will need to drink, take a shit, clean up the sprays of sick now pebble-dashed across your home and body, you might want to change your knickers, particularly if you are still bleeding after birth, rub some unguent into your nipples to prevent them becoming open sores. Hell, you might really indulge yourself and eat something. Likely it will be something cold and beige and will slice your dehydrated gums as you try to choke it down in three bites like a python. Your bed, if you’re lucky enough to have one, will no doubt be an expressionist painting of dried milk, sweat and sick. You will have great cornflakes of dried skin gathering across your scalp through lack of washing and you will not have opened a letter or email for two days.

26 nELL FRiZZELL