UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia India | New Zealand | South Africa

BBC Children’s Books are published by Puffin Books, part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published 2024 001

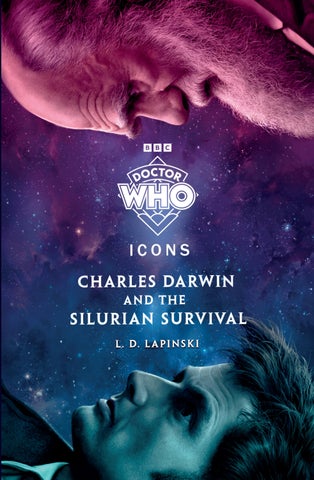

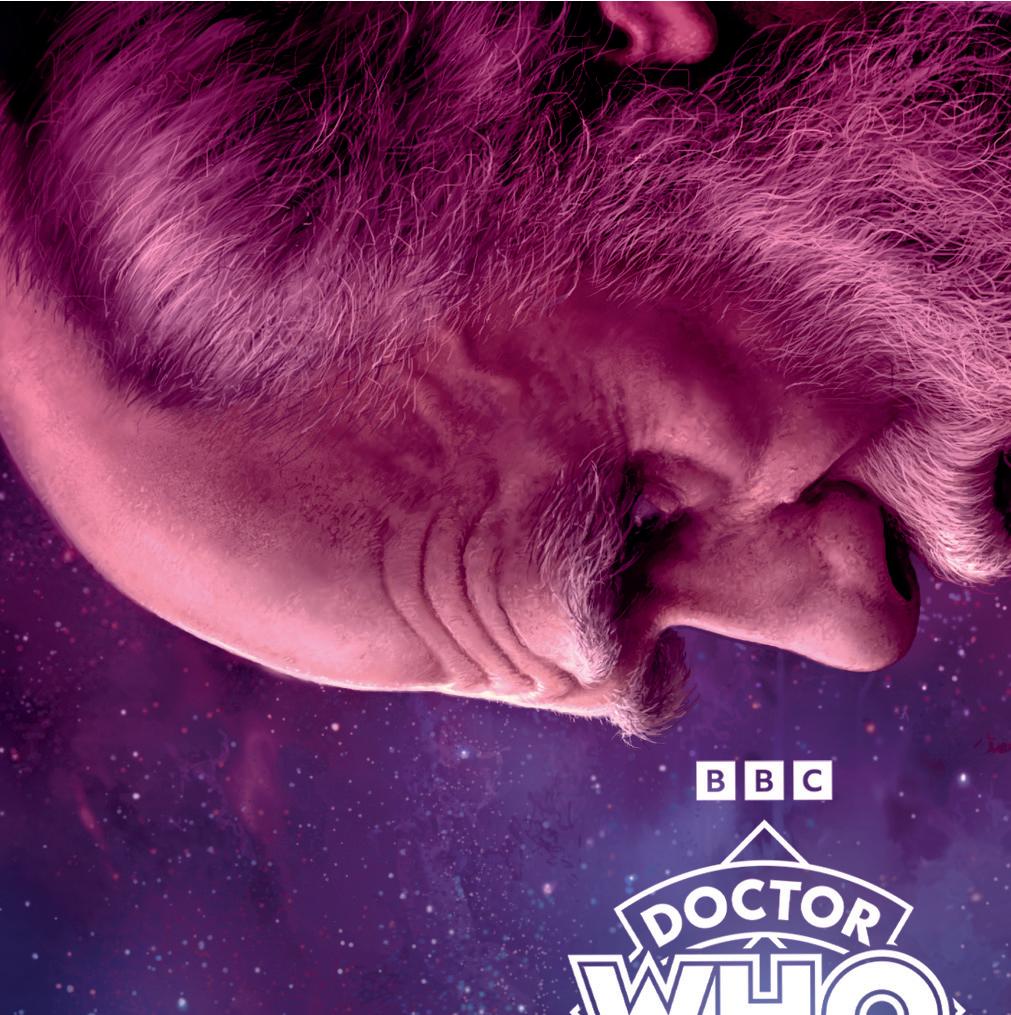

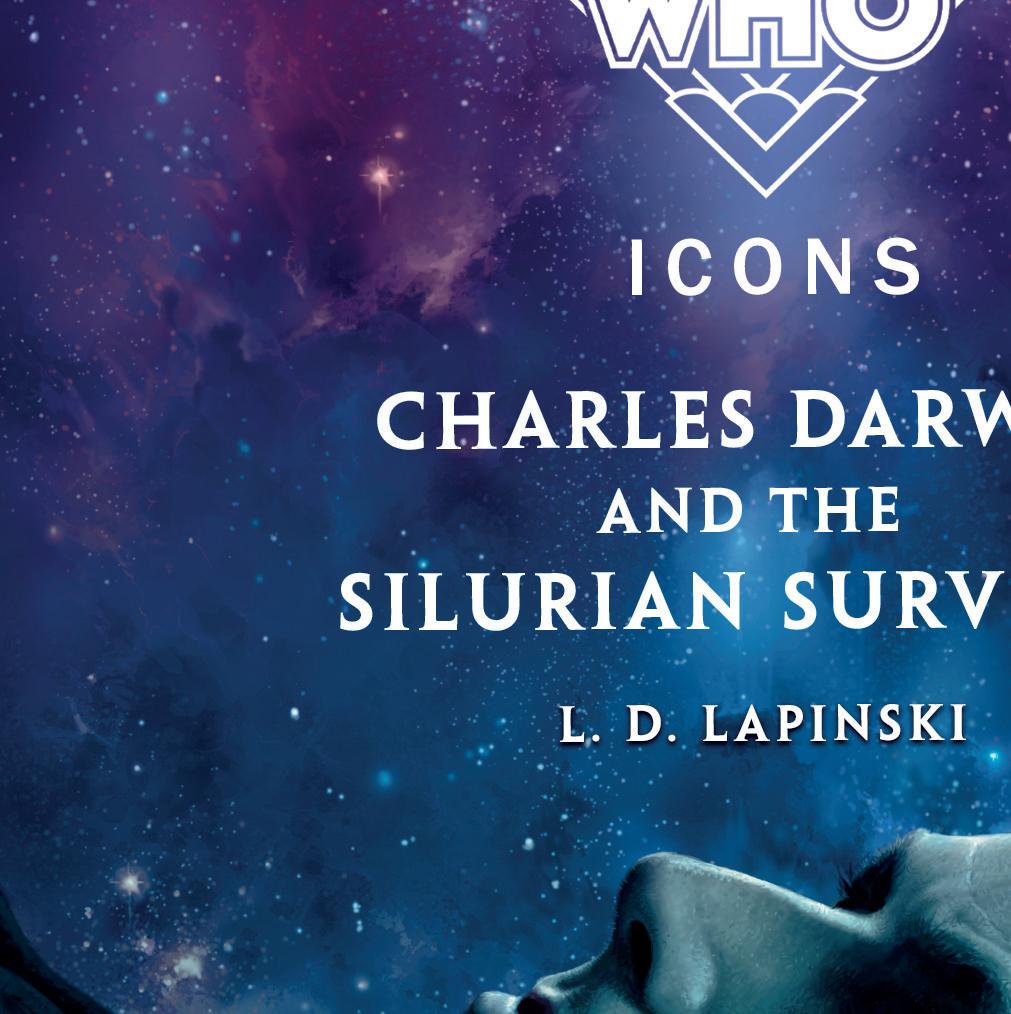

Written by L.D. Lapinski

Copyright © L.D. Lapinski and BBC Distribution Studios Limited, 2024

Extract from Frida Kahlo and the Skull Children copyright © Sophie McKenzie and BBC Distribution Studios Limited, 2024

BBC and DOCTOR WHO (word marks and devices) are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. DOCTOR WHO logo © BBC 1973. Licensed by BBC Studios.

The moral right of the author and copyright holders has been asserted

Set in 11.5/15.5pt Bembo Book MT Pro Typeset by Jouve (UK), Milton Keynes

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D 02 YH 68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN : 978–1–405–96994–9

All correspondence to:

BBC Children’s Books

Penguin Random House Children’s UK One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens London SW 11 7BW

Penguin Random Hous e is committed to a sustainable future for our business, our readers and our planet. is book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

The ship sailed through the darkness, leaving a white trail of churned-up salt and foam in its wake. The deep blue of the ocean – so unlike the iron-greys of home – paled as the ship and its passengers neared land, turning from night-sapphire to cut sea-glass. The clarity of the expanse near the shoreline was so pure that the very shafts of sunlight could be seen cutting through the water. But the clear shallows were not meant for the ship – experience had taught the whole crew that these islands sitting within these crystal waters were surrounded by heavy obstacles of rock that reached like claws from the sea bed, clutching and scraping at the bellies of any vessel foolish enough to attempt getting close.

L.D. Lapinski

And there had been plenty of near-misses for the ship and its crew. Not every day had been as smooth sailing. There had been nights, and days as dark as nights, when the ocean had protested having to carry them. The ship had rolled and tilted from side to side in the extreme. Every time the ship pitched violently from port to starboard, it was feared that men would be lost or that the sea itself would finally lose interest in tormenting the crew and consume the boat entirely.

The day, when it dawned, was bright and clear, the breeze warm. But this did little to help with the seasickness, bonedeep tiredness and general weariness of the young man currently leaning on the gunwale, watching the islands in the distance with a glimmer of hope in his eyes.

It had been a long, long voyage.

Initially estimated to be completed within two years, the voyage of HMS Beagle was now entering its fourth year, with the promise of a return to England finally on the horizon. But the man watching the islands – a naturalist by profession – had been more than willing to bear the hardship of a prolonged trip, for he was undertaking a highly important task.

The ship was anchored, and the wooden dinghies – so small compared to the vessel itself, yet still large enough to hold twenty men each – were being readied to be lowered into the sea.

‘Coming with us, sir?’ a sailor asked, carrying a huge water jar towards the boat. ‘Or are you still green about the gills?’ Other members of the crew overheard and laughed, not good-naturedly.

The naturalist bit back a retort and simply gave a polite smile and a curt nod. He did not dislike the crew on the whole, but there were two distinct camps on the ship – the sailors and the academics. They very rarely mixed well, despite the whole point of the voyage being for charting. There was a team of cartographers and meteorologists aboard, and then there was himself – the ship’s self-appointed naturalist. Of course he was coming to shore. The whole purpose of his being here was to go ashore as often as possible to catalogue, research and discover.

The crew shouted to one another as the naturalist filed in to join the shore party. The crew were always shouting – it was quite tiresome. The young man shifted his specimencollecting basket in his arms – it was light enough now, but by the end of the day, it would be almost too heavy to hold.

A small group of smartly dressed gentlemen went ahead of him, each carrying boxes of paints, mathematical equipment, drawing materials and other bundles. They were the cartographers: men who drew maps, filling in the missing spaces in the knowledge of the world as the ship sailed into parts once unknown. They had been all around the globe, from southern Africa to the Australias, and now to the west coast of South America and the myriad of islands that speckled the ocean close to the continent.

The dinghy was near capacity as the naturalist clambered aboard, balancing his basket in his lap. By the time the trip to shore was complete, he would have dozens of new samples to investigate and catalogue, and the world’s knowledge of this place would become broader still.

L.D. Lapinski

‘Off to collect some flowers, sir?’ one of the sailors called, as the dinghy was lowered down. The heavy ropes and metal links rattled against the belly of the ship. ‘Cook will be glad of any berries you find!’

There was laughter from the other crewmen.

One of the cartographers caught his eye. ‘Don’t mind them,’ he said softly. ‘Our work will benefit everyone. Even those who mock it.’

The naturalist was pleased to have been spoken to so understandingly. ‘Wise words. Thank you.’

‘Not at all. I’m sure there’s a method to your collecting of shells and wee creatures, even if it’s not for me to understand.’

The naturalist opened his mouth to explain some of his thoughts and ideas about the nature of the creatures he had discovered so far, before remembering that there were very few people on the vessel who shared his passion for the natural world. His father had reminded him often that his priorities were not necessarily in line with those of other people, and he would do well to rein in his fixations in company. He gave a polite smile instead. ‘I do believe that this work will be of great importance. Someday.’

The cartographer opened his box of measuring instruments, nodding in agreement. ‘Keep the faith, sir. I am certain that someday, everyone will know the name of Charles Darwin.’

The islands of the Galápagos were scattered and piecemeal in the area of the ocean known as the Eastern Pacific. Formed to look like little more than an afterthought of land masses,

they touched the sea with a mixture of clifftops, beaches and lumpy rock formations. Their ocean-bound existence at least meant a pleasurable breeze, which was much welcomed as the heat of the still air could be stifling.

Finding an ideal place to land took much longer than Darwin would have liked, and by the time they landed the boats on one of the beaches, the seasickness that had plagued him since Plymouth had returned. He staggered up on to the beach, noting that there was indeed such an affliction as having lost his ‘land-legs’. He vaguely wondered if they would ever return, or if he would career around England like a drunkard for the rest of his life.

The cartographers helped to ration out the fresh water and food they had brought with them before casting off back to sea again – they planned to circumnavigate the island to measure the landscape and produce accurate maps for future explorers to use.

Darwin watched them go with a heaviness in his heart – with only himself and half a dozen crewmen on the land, it made for a lonely beginning to the day’s adventure. But the island was full of promise – a dream setting for any naturalist looking to expand his mind.

The environment was rocky, with great rises of stone cascading like carved waterfalls from the horizon down to the beach. Plant life decorated these rocky falls like green foam atop stone waves. Between the white-golden strip of sand that made up the beach and the stone-littered rising landscape was a thick forest of spindly trees, all fighting for sunlight and tightly packed together. A heavy drapery

L.D. Lapinski

of moss, or something like it, clung to the branches like wet laundry hung out to dry. Ferns and leafy shrubs covered the forest floor. Even from the beach, Darwin could make out a cacophony of birdsong, and see the slow lumbering gait of the giant tortoises. He and the crew remembered the creatures from the last island they landed on. The tortoises swung their heads in the direction of the sailors, watching the men drag the supply baskets up the beach, the thick sand wedging them in place. Their eyes stared, unafraid and apparently fascinated by their visitors.

Darwin moved his shoe along the sand, turning over a shell as he did so. This island was filled with riches, just waiting to be discovered. ‘I’ll be back later,’ he said to the sailors, swinging his basket over one arm. ‘I’ve some water and provisions with me.If you make camp elsewhere, leave a note pinned on to one of these trees, will you?’

The sailor who had teased him earlier gave a friendly wave of acknowledgement. ‘Very good, sir. Good luck, sir!’ It seemed that being ashore in such a beautiful place was good for everyone’s mood. The discomfort Darwin had been holding on to lessened.

Feeling lighter, Darwin set off at a brisk pace across the island. Though small, the land had plenty to offer, and as soon as the naturalist was out of sight of the crew, he began collecting. He felt it was better to have more samples than necessary, as he could always discard them later. The island was a carpet of treasures, with shells, stones, bones and more scattered underfoot. The sea obviously came far in at high tide, bringing with it all kinds of debris and flotsam. There