The Witches

BOOKS IN THE ROALD DAHL CLASSIC COLLECTION

James and the Giant Peach

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

The Magic Finger

Fantastic Mr Fox

Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator

Danny the Champion of the World

The Enormous Crocodile

The Twits

George’s Marvellous Medicine

The BFG

Revolting Rhymes

The Witches

Dirty Beasts

Boy: Tales of Childhood

The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me

Going Solo

Matilda

Rhyme Stew

Esio Trot

Billy and the Minpins

MORE BOOKS BY ROALD DAHL

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More

The Great Automatic Grammatizator

Skin and Other Stories

The Witches

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

www.penguin.co.uk www.puffin.co.uk www.ladybird.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape and in the USA by Farrar, Straus and Giroux 1983

Published by Puffin Books 1985

Reissued 2016, 2022

This edition published 2024

001

Text copyright © The Roald Dahl Story Company Ltd, 1983

Illustrations copyright © Quentin Blake, 1983

Text and archive image © The Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre, 2024

The moral right of the author and illustrator has been asserted

ROALD DAHL is a registered trademark of The Roald Dahl Story Company Ltd www.roalddahl.com

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The authorized representative in the EEA is Penguin Random House Ireland, Morrison Chambers, 32 Nassau Street, Dublin D02 YH68

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978–0–241–67766–7

All correspondence to: Penguin Books

Penguin Random House Children’s One Embassy Gardens, 8 Viaduct Gardens, London SW11 7BW

For Liccy

A Note about Witches

In fairy-tales, witches always wear silly black hats and black cloaks, and they ride on broomsticks.

But this is not a fairy-tale. This is about real witches .

The most important thing you should know about real witches is this. Listen very carefully. Never forget what is coming next.

REAL WITCHES dress in ordinary clothes and look very much like ordinary women. They live in ordinary houses and they work in ORDINARY JOBS.

That is why they are so hard to catch.

A real witch hates children with a red-hot sizzling hatred that is more sizzling and red-hot than any hatred you could possibly imagine.

A real witch spends all her time plotting to get rid of the children in her particular territory. Her passion is to do away with them, one by one. It is all she thinks about the whole day long. Even if she is working as a cashier in a supermarket or typing letters for a businessman or driving round in a fancy car (and she could be doing any of these things), her mind will always be plotting and scheming and churning and burning and whizzing and phizzing with murderous bloodthirsty thoughts.

‘Which child,’ she says to herself all day long, ‘exactly which child shall I choose for my next squelching?’

A real witch gets the same pleasure from squelching a child as you get from eating a plateful of strawberries and thick cream.

She reckons on doing away with one child a week. Anything less than that and she becomes grumpy.

One child a week is fifty-two a year.

Squish them and squiggle them and make them disappear.

That is the motto of all witches.

Very carefully a victim is chosen. Then the witch stalks the wretched child like a hunter stalking a little bird in the forest. She treads softly. She moves quietly. She gets closer and closer. Then at last, when everything is ready . . . phwisst! . . . and she swoops! Sparks fly. Flames leap. Oil boils. Rats howl. Skin shrivels. And the child disappears.

A witch, you must understand, does not knock children on the head or stick knives into them or shoot at them with a pistol. People who do those things get caught by the police.

A witch never gets caught. Don’t forget that she has magic in her fingers and devilry dancing in her blood. She can make stones jump about like frogs and she can make tongues of flame go flickering across the surface of the water.

These magic powers are very frightening.

Luckily, there are not a great number of real witches in the world today. But there are still quite enough to make you nervous. In England, there are probably about one hundred of them altogether. Some countries have more, others have not quite so many. No country in the world is completely free from witches .

A witch is always a woman.

I do not wish to speak badly about women. Most women are lovely. But the fact remains that all witches are women. There is no such thing as a male witch.

On the other hand, a ghoul is always a male. So indeed is a barghest. Both are dangerous. But neither of them is half as dangerous as a real witch .

As far as children are concerned, a real witch is easily the most dangerous of all the living creatures on earth. What makes her doubly dangerous is the fact that she doesn’t look dangerous. Even when you know all the secrets (you will hear about those in a minute), you can still never be quite sure whether it is a witch you are gazing at or just a kind lady. If a tiger were able

to make himself look like a large dog with a waggy tail, you would probably go up and pat him on the head. And that would be the end of you. It is the same with witches. They all look like nice ladies.

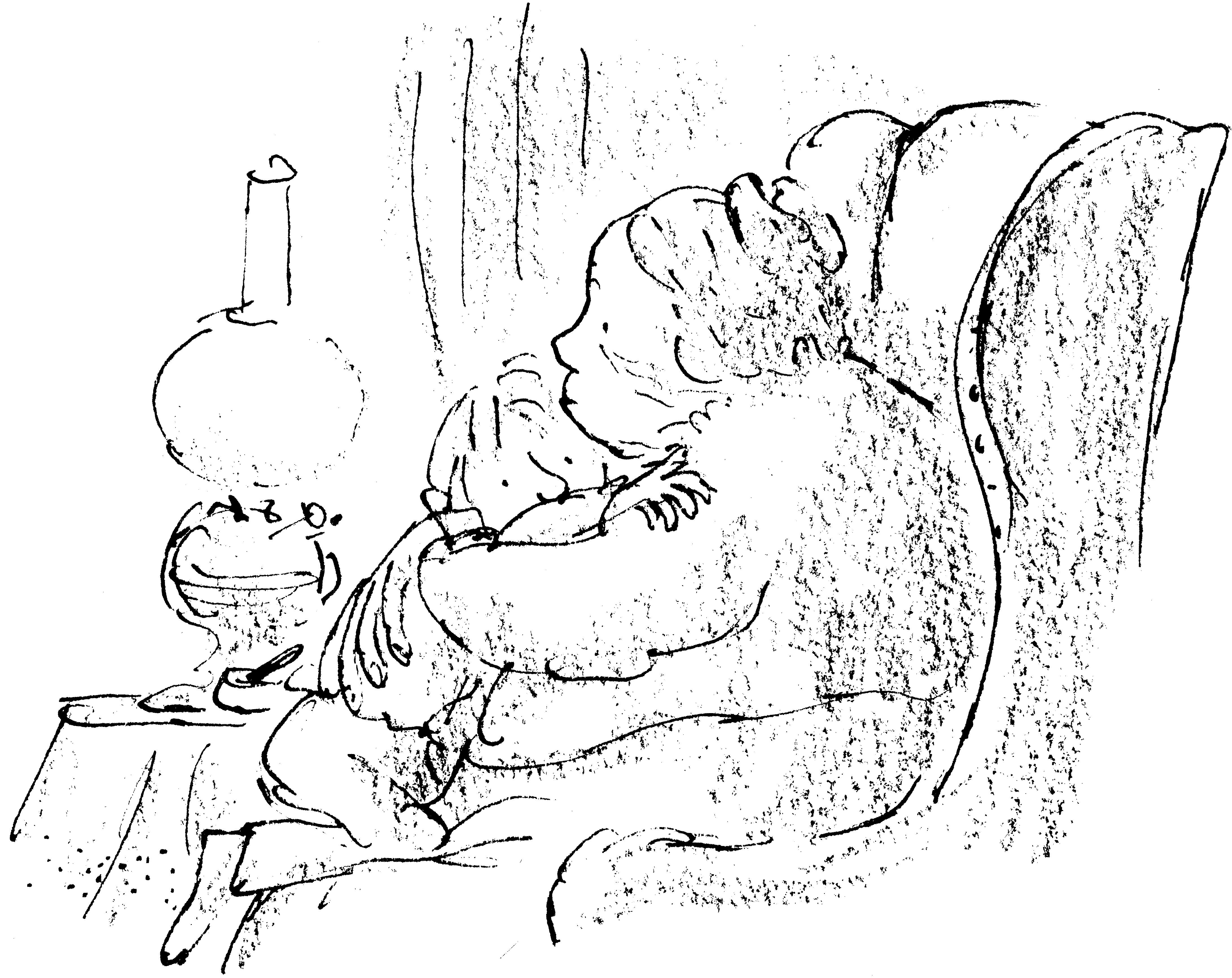

Kindly examine the picture below. Which lady is the witch? That is a difficult question, but it is one that every child must try to answer.

For all you know, a witch might be living next door to you right now.

Or she might be the woman with the bright eyes who sat opposite you on the bus this morning.

She might be the lady with the dazzling smile who offered you a sweet from a white paper bag in the street before lunch.

She might even – and this will make you jump – she

might even be your lovely school-teacher who is reading these words to you at this very moment. Look carefully at that teacher. Perhaps she is smiling at the absurdity of such a suggestion. Don’t let that put you off. It could be part of her cleverness.

I am not, of course, telling you for one second that your teacher actually is a witch. All I am saying is that she might be one. It is most unlikely. But – and here comes the big ‘but’ – it is not impossible.

Oh, if only there were a way of telling for sure whether a woman was a witch or not, then we could round them all up and put them in the meat-grinder. Unhappily, there is no such way. But there are a number of little signals you can look out for, little quirky habits that all witches have in common, and if you know about these, if you remember them always, then you might just possibly manage to escape from being squelched before you are very much older.

My Grandmother

I myself had two separate encounters with witches before I was eight years old. From the first I escaped unharmed, but on the second occasion I was not so lucky. Things happened to me that will probably make you scream when you read about them. That can’t be helped. The truth must be told. The fact that I am still here and able to speak to you (however peculiar I may look) is due entirely to my wonderful grandmother.

My grandmother was Norwegian. The Norwegians know all about witches, for Norway, with its black forests and icy mountains, is where the first witches came from. My father and my mother were also Norwegian, but because my father had a business in England, I had been born there and had lived there and had started going to an English school. Twice a year, at Christmas and in the summer, we went back to Norway to visit my grandmother. This old lady, as far as I could gather, was just about the only surviving relative we had on either side of our family. She was my mother’s mother and I absolutely adored her. When she and I were together we spoke in either Norwegian or in English. It didn’t matter which. We were equally fluent in both languages, and I have to admit that I felt closer to her than to my mother.

Soon after my seventh birthday, my parents took me as usual to spend Christmas with my grandmother in

Norway. And it was over there, while my father and mother and I were driving in icy weather just north of Oslo, that our car skidded off the road and went tumbling down into a rocky ravine. My parents were killed. I was firmly strapped into the back seat and received only a cut on the forehead.

I won’t go into the horrors of that terrible afternoon. I still get the shivers when I think about it. I finished up, of course, back in my grandmother’s house with her arms around me tight and both of us crying the whole night long.

‘What are we going to do now?’ I asked her through the tears.

‘You will stay here with me,’ she said, ‘and I will look after you.’

‘Aren’t I going back to England?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘I could never do that. Heaven shall take my soul, but Norway shall keep my bones.’

The very next day, in order that we might both try to forget our great sadness, my grandmother started telling me stories. She was a wonderful story-teller and I was enthralled by everything she told me. But I didn’t become really excited until she got on to the subject of witches. She was apparently a great expert on these creatures and she made it very clear to me that her witch stories, unlike most of the others, were not imaginary tales. They were all true. They were the gospel truth. They were history. Everything she was telling me about witches had actually happened and I had better believe it. What was worse, what was far, far worse, was that witches were still with us. They were all around us and I had better believe that, too.

‘Are you really being truthful, Grandmamma? Really and truly truthful?’

‘My darling,’ she said, ‘you won’t last long in this world if you don’t know how to spot a witch when you see one.’

‘But you told me that witches look like ordinary women, Grandmamma. So how can I spot them?’

‘You must listen to me,’ my grandmother said. ‘You must remember everything I tell you. After that, all

you can do is cross your heart and pray to heaven and hope for the best.’

We were in the big living-room of her house in Oslo and I was ready for bed. The curtains were never drawn in that house, and through the windows I could see huge snowflakes falling slowly on to an outside world that was as black as tar. My grandmother was tremendously old and wrinkled, with a massive wide body which was smothered in grey lace. She sat there majestic in her armchair, filling every inch of it. Not even a mouse could have squeezed in to sit beside her. I myself, just seven years old, was crouched on the floor at her feet, wearing pyjamas, dressing-gown and slippers.

‘You swear you aren’t pulling my leg?’ I kept saying to her. ‘You swear you aren’t just pretending?’

‘Listen,’ she said, ‘I have known no less than five children who have simply vanished off the face of this earth, never to be seen again. The witches took them.’

‘I still think you’re just trying to frighten me,’ I said.

‘I am trying to make sure you don’t go the same way,’ she said. ‘I love you and I want you to stay with me.’

‘Tell me about the children who disappeared,’ I said.

My grandmother was the only grandmother I ever met who smoked cigars. She lit one now, a long black cigar that smelt of burning rubber. ‘The first child I knew who disappeared,’ she said, ‘was called Ranghild Hansen. Ranghild was about eight at the

time, and she was playing with her little sister on the lawn. Their mother, who was baking bread in the kitchen, came outside for a breath of air. “Where’s Ranghild?” she asked.

‘“She went away with the tall lady,” the little sister said.

‘“What tall lady?” the mother said.

‘“The tall lady in white gloves,” the little sister said. “She took Ranghild by the hand and led her away.” No one,’ my grandmother said, ‘ever saw Ranghild again.’

‘Didn’t they search for her?’ I asked.

‘They searched for miles around. Everyone in the town helped, but they never found her.’

‘What happened to the other four children?’ I asked.

‘They vanished just as Ranghild did.’

‘How, Grandmamma? How did they vanish?’

‘In every case a strange lady was seen outside the house, just before it happened.’

‘But how did they vanish?’ I asked.

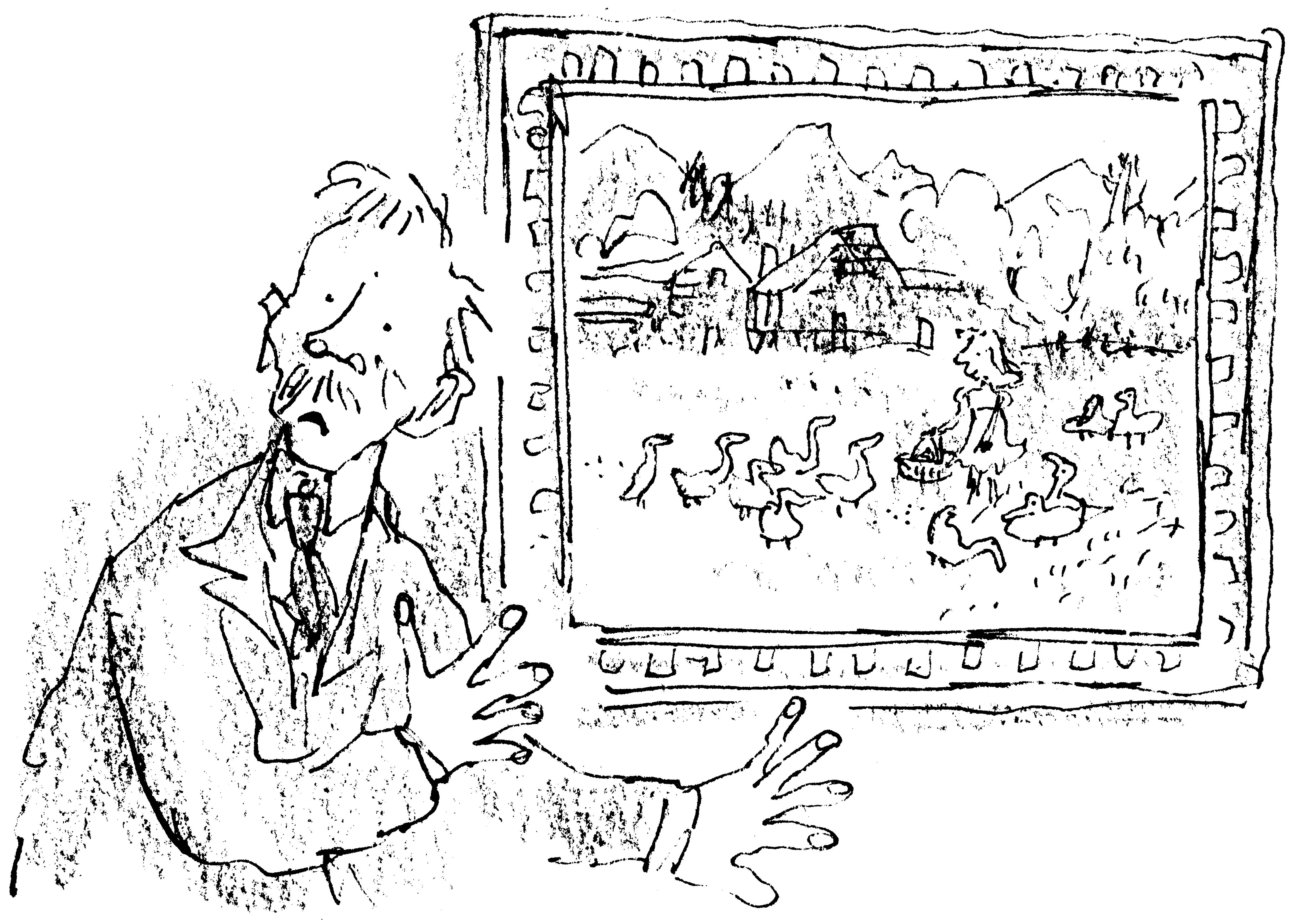

‘The second one was very peculiar,’ my grandmother said. ‘There was a family called Christiansen. They lived up on Holmenkollen, and they had an old oil-painting in the living-room which they were very proud of. The painting showed some ducks in the yard outside a farmhouse. There were no people in the painting, just a flock of ducks on a grassy farmyard and the farmhouse in the background. It was a large painting and rather pretty. Well, one day their

daughter Solveg came home from school eating an apple. She said a nice lady had given it to her on the street. The next morning little Solveg was not in her bed. The parents searched everywhere but they couldn’t find her. Then all of a sudden her father shouted, “There she is! That’s Solveg feeding the ducks!” He was pointing at the oil-painting, and sure enough Solveg was in it. She was standing in the farmyard in the act of throwing bread to the ducks out of a basket. The father rushed up to the painting and touched her. But that didn’t help. She was simply a part of the painting, just a picture painted on the canvas.’

‘Did you ever see that painting, Grandmamma, with the little girl in it?’

‘Many times,’ my grandmother said. ‘And the peculiar thing was that little Solveg kept changing her position in the picture. One day she would actually be inside the farmhouse and you could see her face looking out of the window. Another day she would be far over to the left with a duck in her arms.’

‘Did you see her moving in the picture, Grandmamma?’

‘Nobody did. Wherever she was, whether outside feeding the ducks or inside looking out of the window, she was always motionless, just a figure painted in oils. It was all very odd,’ my grandmother said. ‘Very odd indeed. And what was most odd of all was that as the years went by, she kept growing older in the picture. In ten years, the small girl had become a young woman. In thirty years, she was middle-aged. Then all at once, fifty-four years after it all happened, she disappeared from the picture altogether.’

‘You mean she died?’ I said.

‘Who knows?’ my grandmother said. ‘Some very mysterious things go on in the world of witches.’

‘That’s two you’ve told me about,’ I said. ‘What happened to the third one?’

‘The third one was little Birgit Svenson,’ my grandmother said. ‘She lived just across the road from us. One day she started growing feathers all over her body. Within a month, she had turned into a large white