“Kairos”

AI THE END OF CIVILIZATION

SHORTAGE OF LECTURE HALLS

IRON-BASED HYDROGEN

“Kairos”

AI THE END OF CIVILIZATION

SHORTAGE OF LECTURE HALLS

IRON-BASED HYDROGEN

Dear reader,

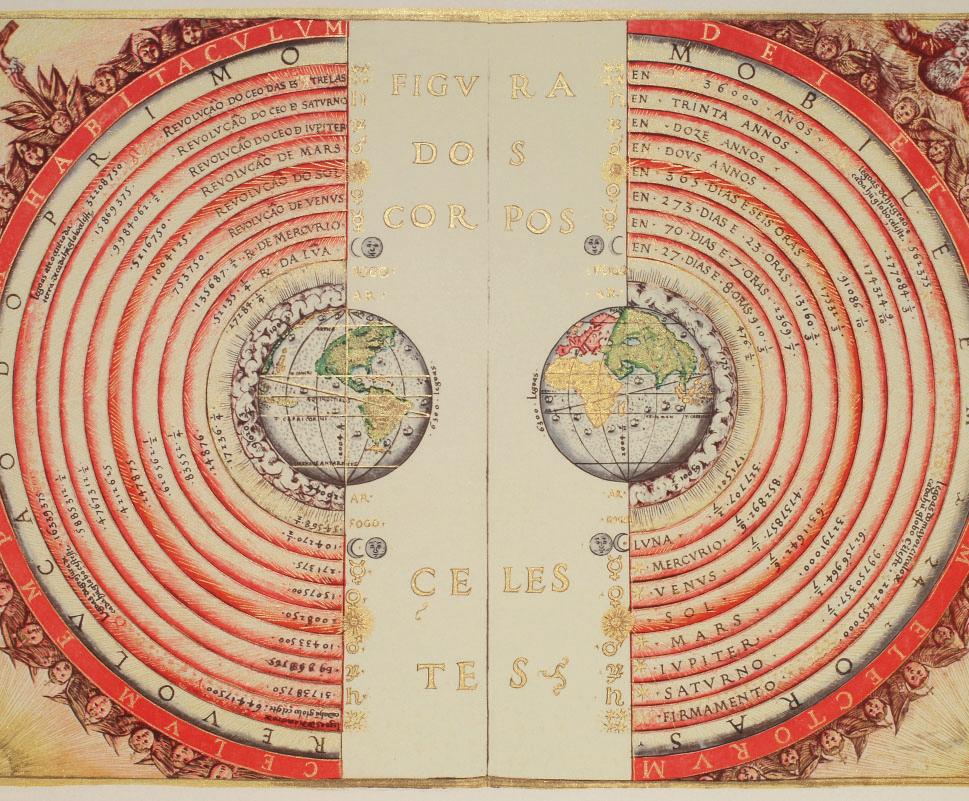

This edition of openME is titled Kairos, an ancient Greek word that captures the essence of the right moment, the critical instant when time opens its arms to possibility. The future is unfolding swiftly before you. You are standing at the edge, in a place in time where your participation is crucial.

You have just completed your first quartile, a perfect reflection of Kairos itself. You’ve faced courses, projects, and exams, and now you stand poised at the foot of the rest of your academic year. This is your moment to participate, to step forward, to shape what comes next.

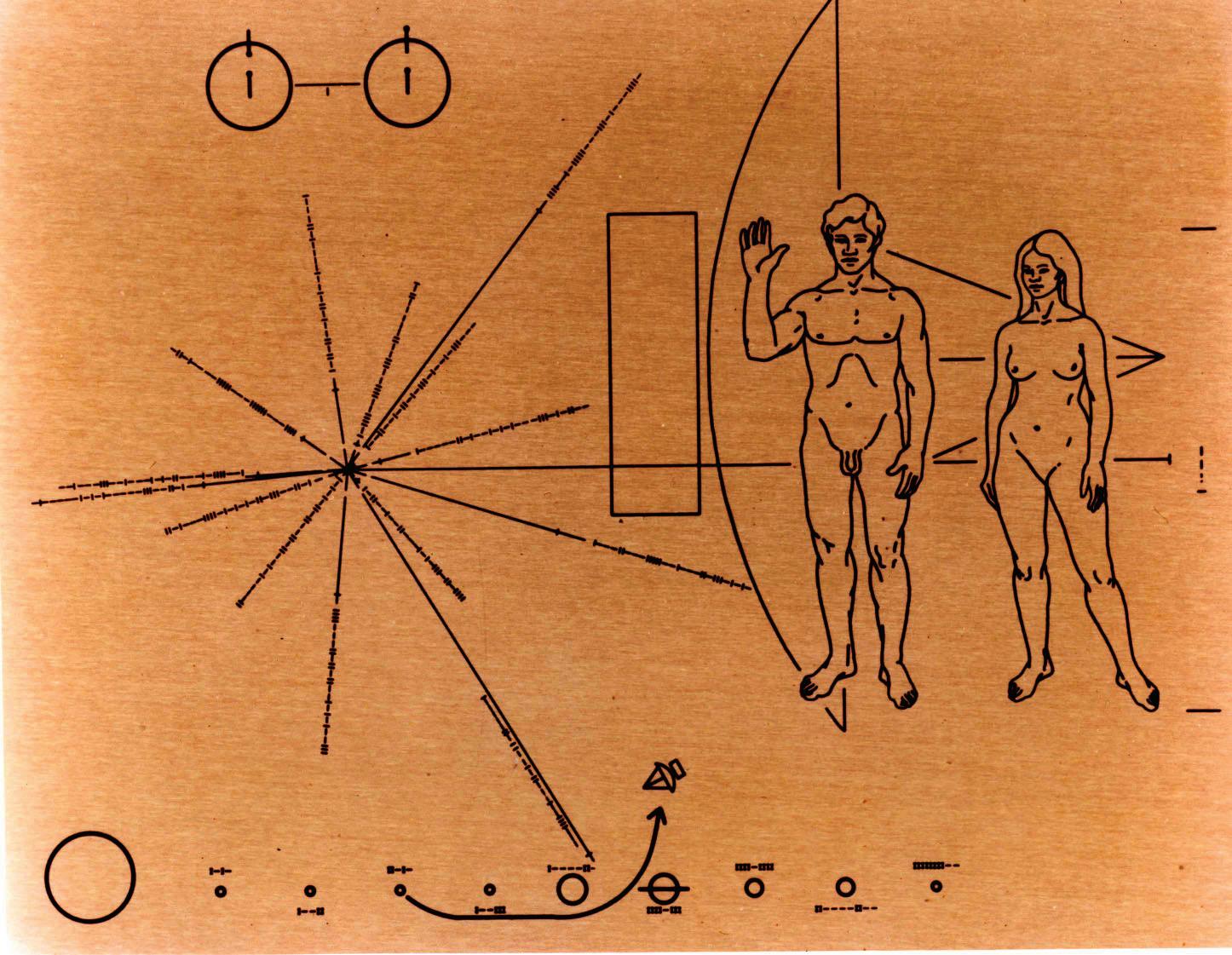

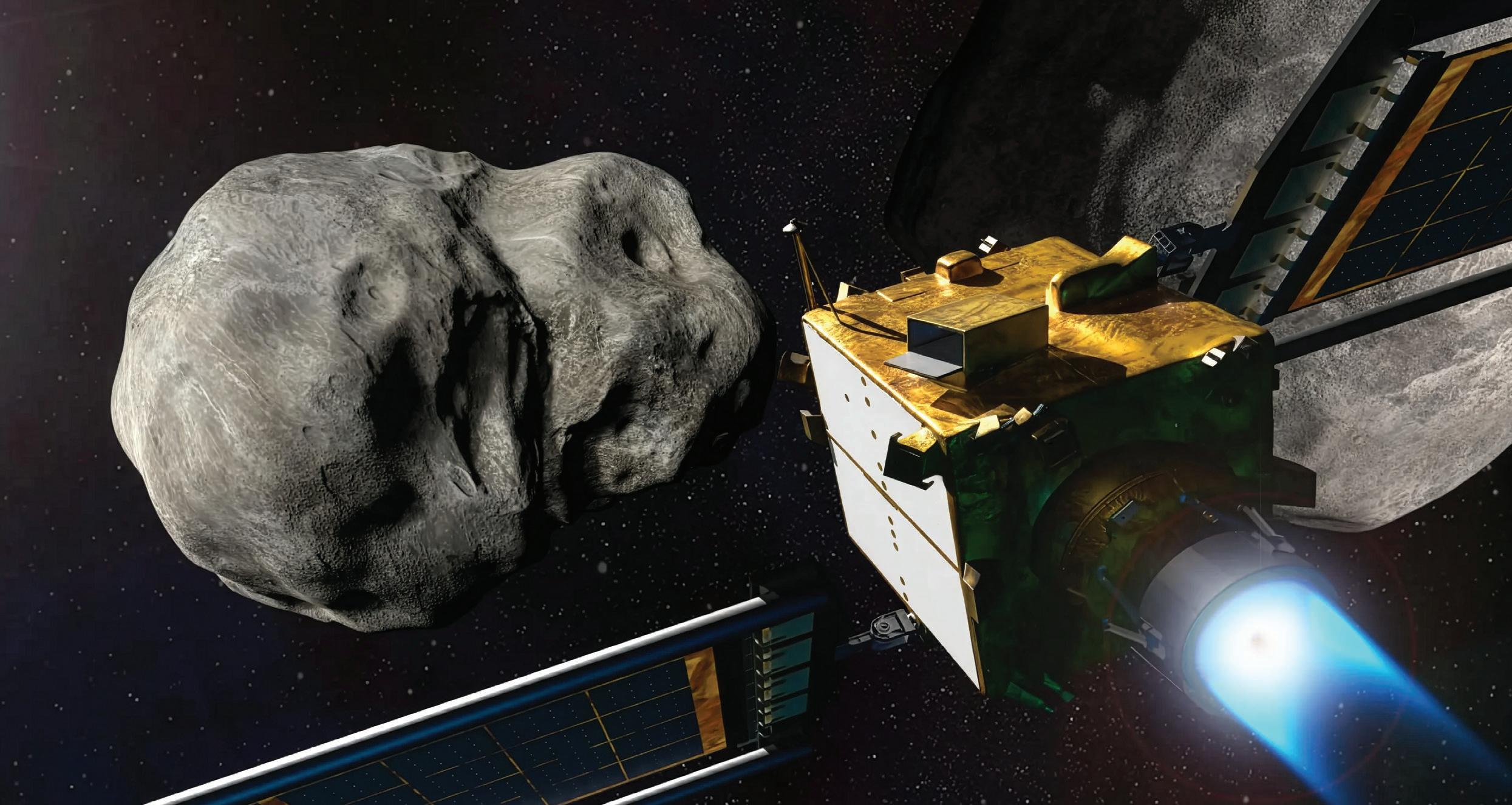

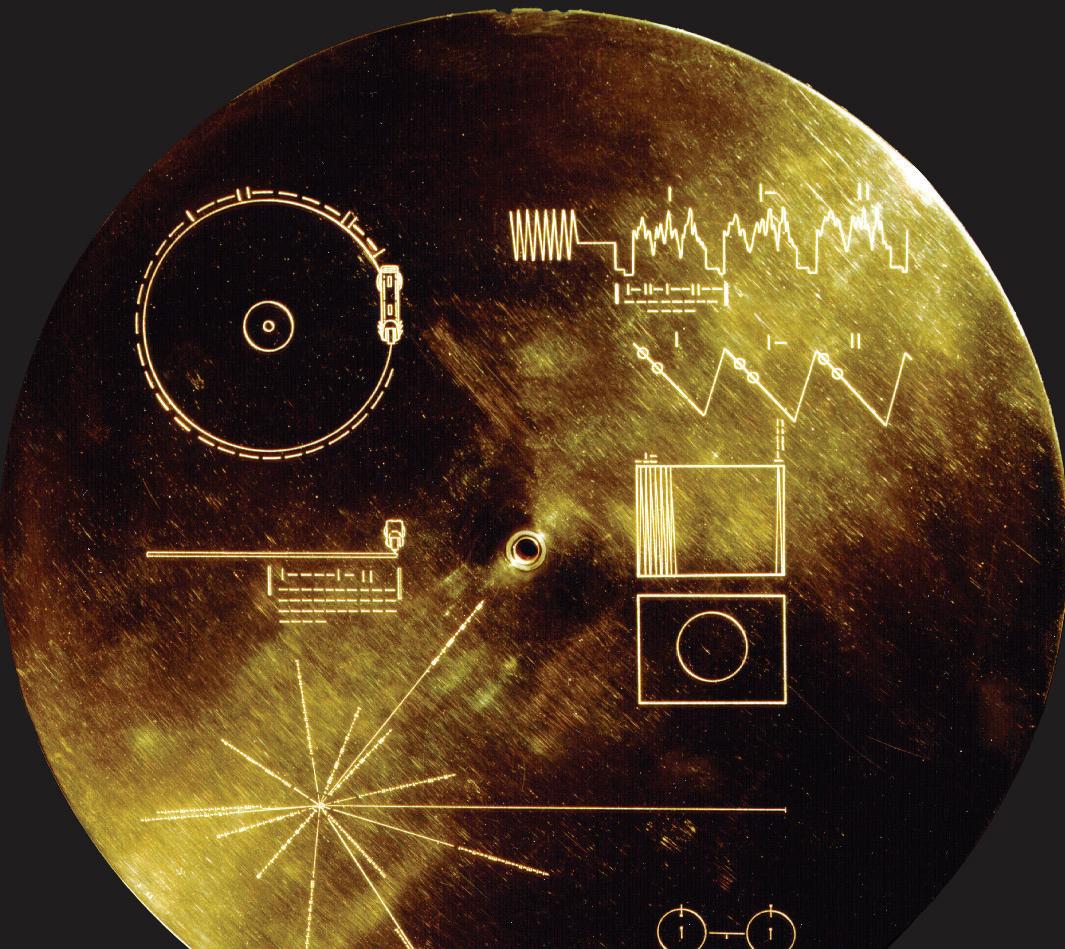

Within these pages, you’ll find reflections on the many faces of Kairos, from thought-provoking pieces about whether AI might one day replace us, to stories of our attempts to communicate with aliens, to projects that capture carbon dioxide from the air.

And beyond the theme, we have articles about wellbeing, the lecture hall shortage, the archive of the Association, and an interview with a new academic advisor.

With kind regards,

Vide Papac Editor-in-Chief

December 2025, volume 57, issue 1

The ‘openME’ is a publication by the study Association for Mechanical Engineering Simon Stevin of the Eindhoven University of Technology

Editor-in-Chief

Vide Papac

Design

Maartje Borst, Rik Lubbers, Roelof Mestriner, Joel Peeters, Lex Verberne

Layout

Stefan Geerts, Rixt Hofman, Vide Papac, Luca Prundus

Editorial committee

Owen Dumortier, Max Dumoulin, Stefan Geerts, Anastasia Ghlighvashvili, Rixt Hofman, Vide Papac, Ysabel Policar, Luca Prundus, Carlijn Roggen

Illustrations and Pictures

Editorial committee, Photo committee, NASA, Freepik, source stated otherwise

Printing office Drukkerij Snep

Circulation

600 pieces

Contact

Eindhoven University of Technology

Gemini-North -1.830

Den Dolech 2 5612AZ Eindhoven

Post office box 513

E-mail: redactie@simonstevin.tue.nl

Homepage: simonstev.in

When

The clock reads 23:00, if it’s correct, I don’t know. I saw this coming far in advance. Everything is hacked by AI. Maybe it’s playing with my mind, forcing me out of this bunker. But it’s only a matter of time before the AI will figure out where I am and send drones. Or it’s waiting until my mind breaks so it can use me as a tool. Should I wait until that happens? The clock reads 02:27.

As a university, TU/e wants to keep growing, especially with Project Beethoven in mind, which aims to attract more students. This growth is going well, but it also brings new problems. The campus is getting crowded, there aren’t enough study places, and the shortage of lecture halls is becoming a serious issue.

WRITTEN BY WOUT MEULENBROEK

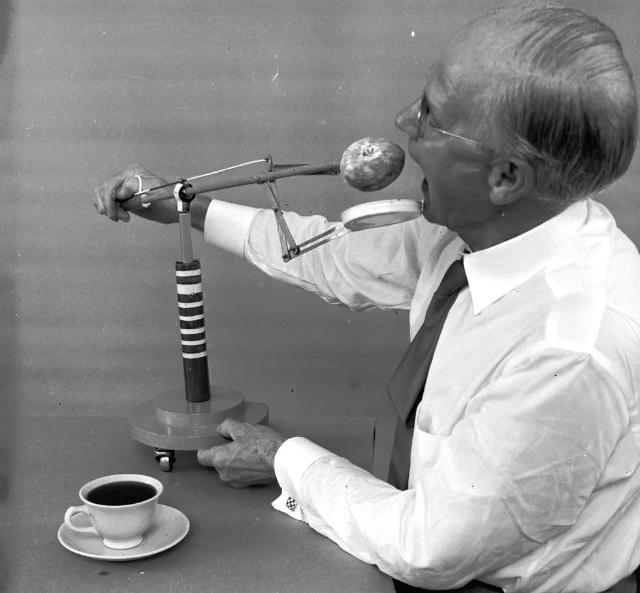

Recently, our beautiful Association turned 68 years old. It is almost impossible to imagine how many generations of people have made memories and left their mark with the Association over the years. Luckily, members and Boards past have had the foresight to store important and interesting documents in our archive . Because of their e fforts, we can look back in time and get some insight into even the earliest years of the Association. I want to invite you along with me on a dive through the archive to look at the start of many things that are still done within the Association to this day.

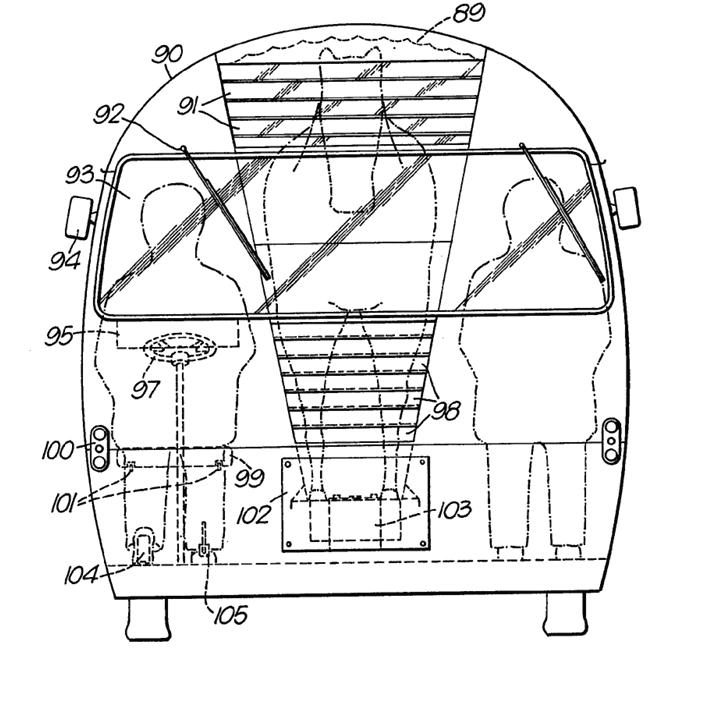

When exploring the history of the Association, what better place to begin than with land yachting? Within the archive, we have a large folder that contains everything we have on land yachting. This ranges from large blueprints for some of the earliest land yachts to promotional material and registration lists for the first editions of the land yachting weekends. Although the land yachting weekends on the beaches of IJmuiden and De Panne are well known to our current members, this is not how the land yachting activities of the Association started. The first activities were just land yachting days: single days in the weekend where members could try their hand at land yachting, not on the beach, but on an airfield near Helmond. The land yachting folder even contains written communication with the chief of this armyowned airport. Later, the first land yachting weekends were organized, of course, on the beaches of De Panne. There are

limited pictures to be found of land yachting activities of this time. However, on the ones I found you can see the yachts were not as diverse as our current fleet, likely having loaned a few from the land yachting club in De Panne.

Considering you are reading this magazine right now, I think it’s only fitting to continue with the beginning of the openME. Within the Association, it is relatively well-known that the openME has only been our magazine since the 62nd Board year. Before this time it was called the “Simon Ster”. However, what I do not think to be common knowledge is that the first edition of the Simon Ster was already published in 1969. These few first editions, with some very nice hand drawn covers, were only a few pages long and were meant to be more like an internal newspaper than a magazine: really only containing articles on changes within the university concerning ME students. These editions were written by a small team of editors, probably by hand, and typed out on typewriter by some willing copyists of the university at that time. It took 20 years before the first Simon Ster was printed professionally, with a similar bound cover like today’s openME, for the anniversary edition in 1989.

In this day and age, one of the most produced types of documents within the Association is promotional posters. Unfortunately, this is not the case in the archive, where most of the documents are not-so-interesting financial pieces. The collection of posters we do have is small and it is quite difficult to figure out from what year they come. Of course, the old posters are all hand-drawn and they are really quite impressive. Looking through the old posters you can see the development of how they were created. Older posters are fully hand-drawn and made on two A4 papers taped together, while newer posters often use stencils so multiple ones can be produced. The newer posters even have a kind of corporate identity with the same

logo and text at the bottom of each poster. Besides this, looking through the poster folder gives a great insight into the types of drinks and excursions that were organised back in the day. So, if you ever need inspiration for a themed activity or poster design, maybe you can look back in time.

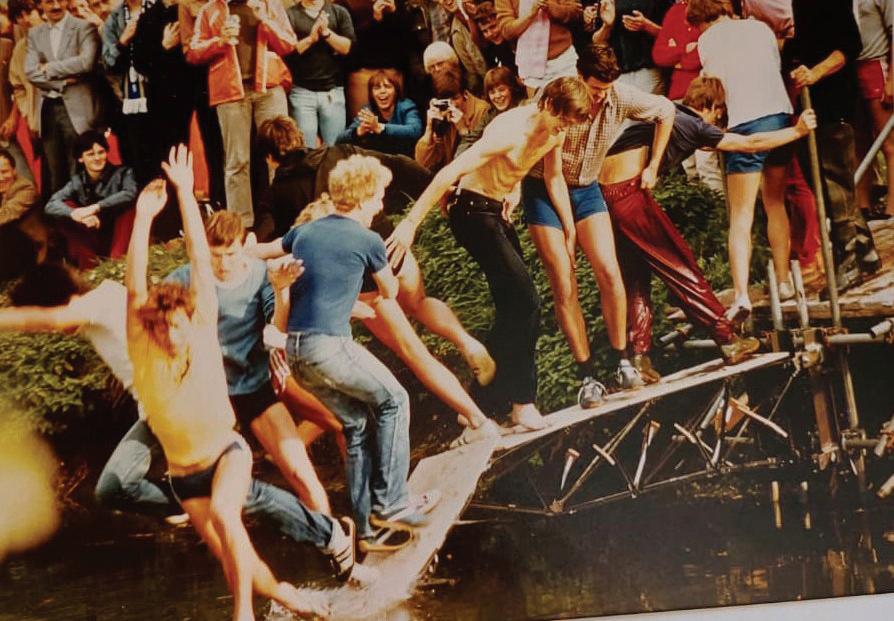

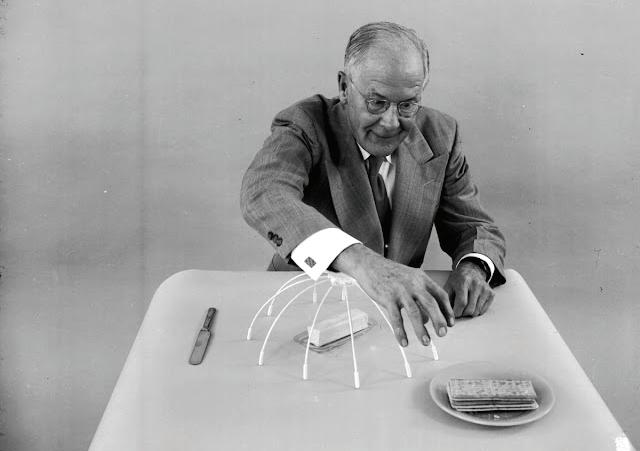

A very old concept within Mechanical Engineering at the TU/e is the “Dommeldoop” (Dommel baptism in English). For a long time this has been the moment where first-year ME students test out their design for their first project, which is now called “Introduction to Mechanical Engineering and Truss Structures”. A few years ago, the department decided to stop doing the Dommeldoop and in my first year I actually didn’t do any physical building. Luckily, the building sessions have been reintroduced to the course and we might see a Dommeldoop again in the future. Now, back to the past, because you might not know that the Dommeldoop actually did not start as a part of the first-year project, but rather as a part of the Introduction week. Similarly to the building case we organise now, the introduction groups were given simple materials and tools to build a structure with which to accomplish a goal. Of course, this goal would have to do with the Dommel. I know this because we have a booklet in the archive containing information and pictures on the editions of the Dommeldoop from 1980 to 1983. This booklet was made as a gift to Prof. Ir. van Vollenhoven, who came up with the concept of the Dommeldoop. The challenges of the Dommeldoop of each year were:

• 1980: A bridge supported at both ends.

• 1981: A bridge supported at one end.

• 1982: A support for the cable of a zipline that the builders could use to try to reach the opposite bank of the Dommel.

• 1983: A propulsion system to propel a raft which was given by the organization.

You can see that the ideas kept getting bigger each year: from the pictures you can tell that there was even fire hoses and an excavator present at the 1983 addition.

Something that is very close to me, but is probably less enjoyable for you to read than this openME, are the GMM minutes. Before the time of easily accessible computers, the minutes of GMMs had to be written by hand. This was done in a small notebook which contained minutes over several years. A single GMM would take approximately 20 pages of this notebook and one year of the lifetime of the Secretary’s wrist. I will assume having a good handwriting was one of the most important characteristics of the Secretary during this time. That is to say, although the handwritten minutes are very charming, I am very happy with my computer and keyboard.

I know it is difficult to imagine, but the Simonlied we know and love today has not always been the Simonlied. Actually, there have been several Simon songs throughout the years, all different, but all called the Simonlied. From the different songbooks we have in the archive, I have been able to find three older versions of the Simonlied, but it is certainly possible that there have been more. You can look at the lyrics of both songs below. Unfortunately, I only know the melody of one, but if anyone can figure out the melody of the others, please let me know.

Simonlied 1

Melody: unknown

De fietsenmaker, vonkentrekker, basic-specialist, normenlezer, beitelslijper, turbomachinist, buizenbuiger, regelaar, ja zelfs het kleinste kind, gaat met Simon voor de wind.

Chorus: Simon Stevin, halleluja! Werktuigbouwer, halleluja! Glorie, glorie, halleluja! Met Simon voor de wind!

Lang geleden leefde Simon in dit lage land. Had van bruggen, clootcransen en zeilwagens verstand.

Maakte op een mooie dag een tochtje met de prins. Vanaf toen ging hij voor de winds.

Chorus

Vele jaren later hebben wij de schone taak, zijn naam in eer te houden, een zeer errenstige zaak. Maar samen sterk staande en een ieder goed gezind, gaat het Simon voor de wind.

Chorus

Simonlied 2

Melody: ‘t Kleine café aan de haven

Hij leefde rond zeventienhonderd dus gaan wij heel even terug in de tijd Hij zocht naar iets nieuw, en dacht bij zichzelf ’n frame en een zeil dat ook rijdt

Op ’n stil strand aan de kust, met z’n maatje Prins Maurits die hielp hem daarbij Het lukte ze zeilden op wieltjes ze lachten en waren toen ook nog heel blij

Chorus:

Simon Stevin wij brengen jou een serenade Ja wij studeren nu ook Werktuigbouw

Simon Stevin wij rijden nu in jouw zeilwagen

Door weer en wind, barsten wij soms, van de kou

Studenten van T.U. ontmoeten elkaar vaak in de kamer van Simon Stevin

Dvve één werktuigbouw, de ander fietsenmaker ’n borrel, gaat er wel in Het blad Simon Ster kun je lezen misschien zie je ons wel de volgende keer Dit liedje is bijna ten einde

Op speciaal verzoek, doen wij het wel weer

Chorus

Wij moeten hard werken, bloed, zweet en tranen wat jaartjes, afgestudeerd. Even terug in de tijd beste Simon Wij hebben van jou veel geleerd

Wat wij nu merken, als wij weer gaan zeilen zomaar aan de Belgische kust

In onze gedachten speel jij door ons hoofd wij weten dat jij nu uitrust

Chorus

Simonlied 3

Melody: unknown

Terwijl ik trek aan mijn sigaar, moet ik denken aan de tijden. Dat we met de wind door het haar, in onze wagens gingen zeilen.

Chorus:

Daar ik Werktuigbouw studeer, is het Simon die ik eer.

En dus klinkt het eensgezind: Simon, vóór de Wind !!!

In De Weeghconst kom ik graag, om een biertje weg te kappen. Daar praat men over nu, maar vooral ook over later.

Chorus

Het fundament van ons bestaan, is een driehoek met veertien cloothen. Deze cloothkrans houden wij hoog, door het logo uit te dragen.

Chorus

Het centrum van aktiviteit, is de Simonkamer. Daar werken leden en Bestuur, als goede vrienden samen

Chorus

Over the past summer, it was time for me to complete my Bachelor’s degree by writing my Bachelor’s End Project (BEP). After studying more or less nominally, doing my BEP during the summer was the perfect opportunity to get back on track and start my Master’s degree in Quartile 1.

W T J

Sydney, Cape Town, Geleen, Tokyo, Aarhus. In previous editions, the internship section featured many faraway places, and Geleen. This time, however, we are staying a bit closer to home: right here in Eindhoven Over the past summer, it was time for me to complete my Bachelor’s degree by writing my Bachelor’s End Project (BEP). After studying more or less nominally, doing my BEP during the summer was the perfect opportunity to get back on track and start my Master’s degree in Quartile 1. An internship at the university during the summer break requires a fair amount of self-discipline, especially when everyone else is hiking in the mountains or relaxing somewhere sunny. So instead, I looked for a place that keeps going during the summer months. I found that place at Nobleo Technology, an engineering company where many aspects of Mechanical Engineering come together.

As mechanical engineers, we are always looking for new ideas. We try things out, build quick setups to test the principle, and sometimes move on to something else before the idea reaches its full potential. As a result, some of these prototypes end up collecting dust, waiting for someone to rediscover them.

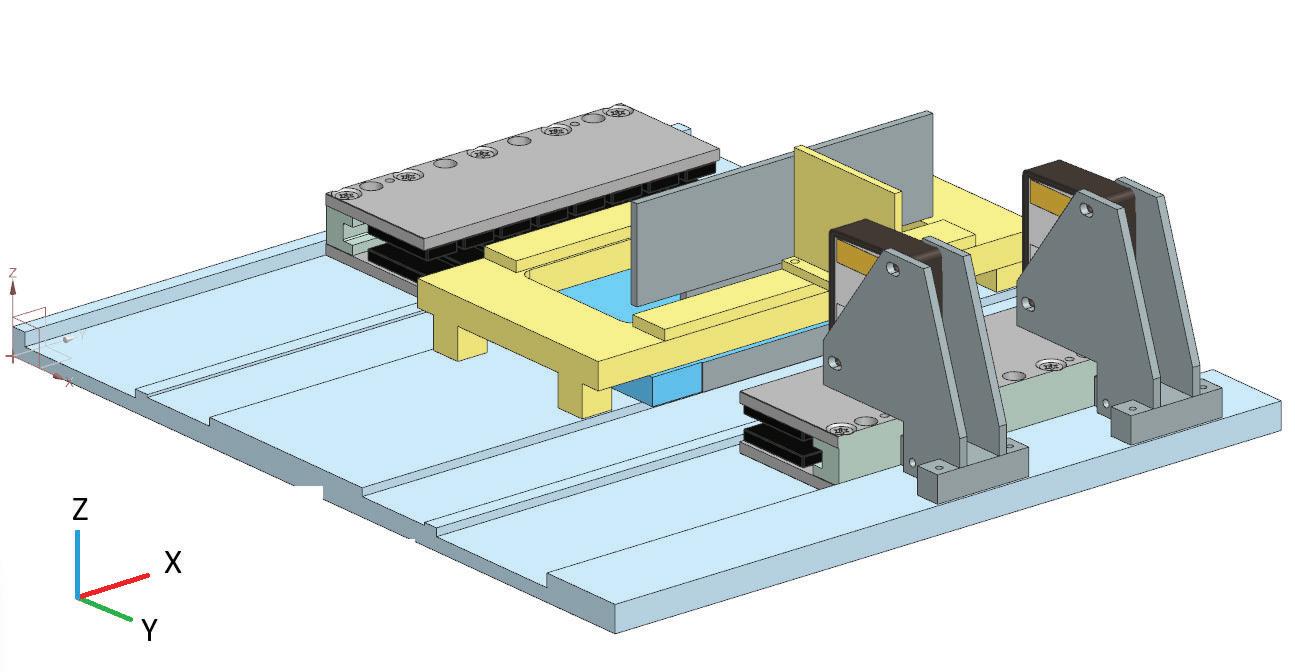

One technology that did get a second chance is the Nforcer Technology, originally developed at Philips. The goal of this system is to achieve large onedimensional strokes with high precision.

Anyone who has taken the course Design Principles probably still remembers the phrase ”No play, no friction.” That is exactly what linear electromotors aim for: precise motion without mechanical contact, and thus no wear. In a standard configuration, however, such motors are sensitive to disturbances and offsets. In my BEP, I worked with a setup that applied a clever trick to overcome those issues.

Most of us remember the right-hand rule from physics: when the magnetic field and the current that flows trough through a wire are perpendicular, a force appears that is perpendicular to both. This is Lorentz’s Law, named after Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz, and it forms the basis for nearly all electromagnetic actuation principles. In vector form, the Lorentz force is given by:

Where I is the current through the conductor, L is the length vector of the conductor in the direction of current flow, B is the magnetic flux density. The cross product indicates that the resulting force F is perpendicular to both the magnetic field and the current.

Before applying this principle, we will have to make a small detour into the world of electrical engineering — not too deep, just enough to understand three-phase power.

Three-phase power consists of three alternating currents, each shifted by 120° in phase. Together, they generate a rotating or traveling magnetic field, which allows for smooth and efficient motor operation. Because the power from each phase overlaps in time, the total power never drops to zero. The process of controlling the magnitude and phase shift of these currents is called commutation.

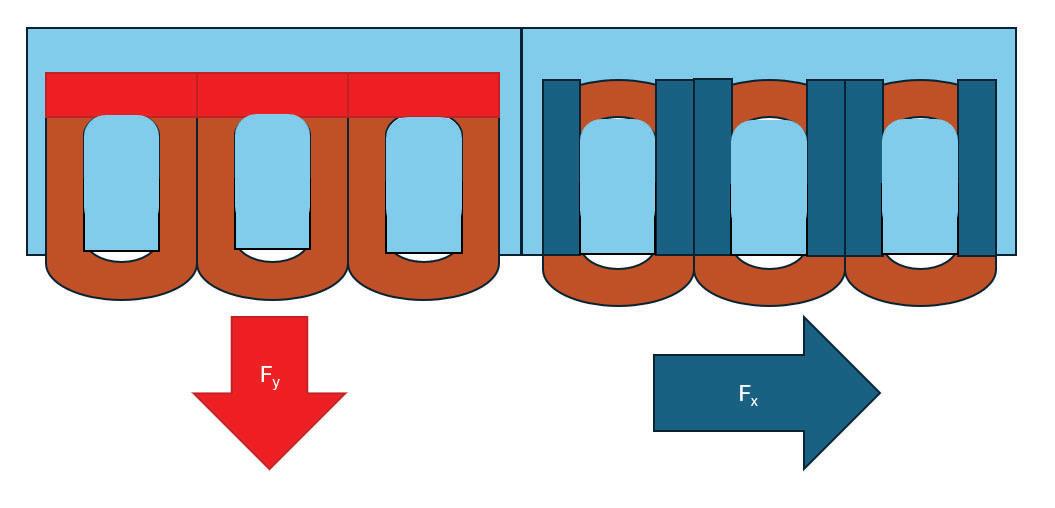

In a normal linear motor, only the straight parts of the coil contribute to motion, resulting in purely one-dimensional movement. However, if we pull back the yoke slightly — so that part of the coil extends outside the magnetic field — the curved sections of the coil also experience a magnetic force.

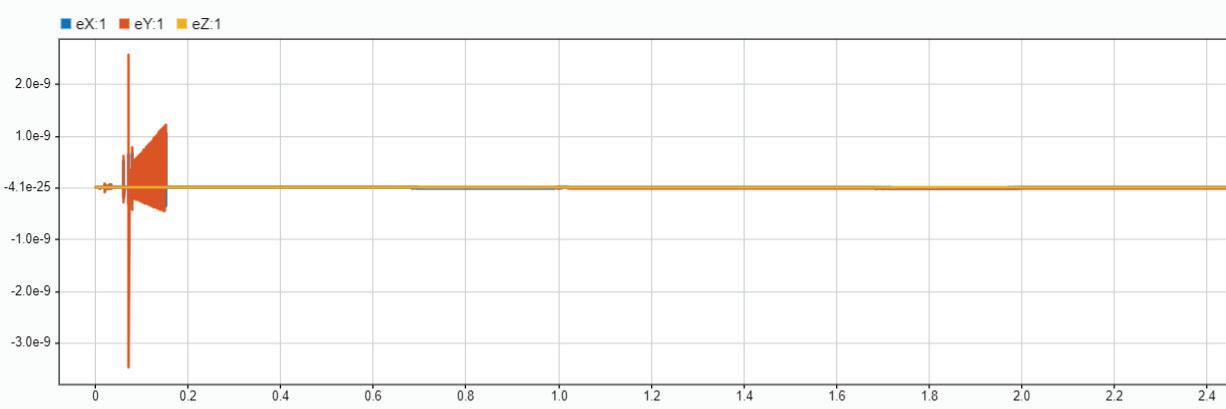

Applying Lorentz’s Law again, and using the righthand rule, shows that planar motion becomes possible. This is illustrated in Figure X, which shows how the direction of the Lorentz forces depends on the orientation of the conducting wire.

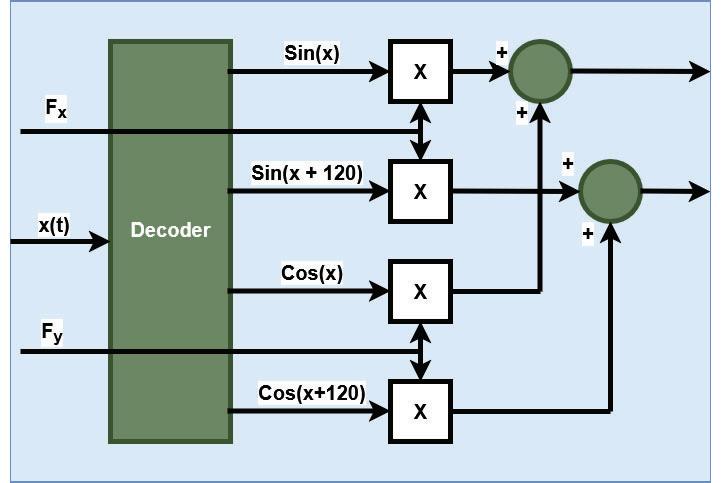

After some mathematical manipulation, the commutation for planar control can be expressed as:

Here, the magnitude of the force is determined by and the phase shift is given by . A simplified block diagram of this commutation scheme is shown in the figure below.

In theory, this commutation principle could simply be implemented in a control loop and everything would work perfectly. In practice, there is a complication. To achieve ”No play, no friction,” the moving stage is supported by magnetic bearings, allowing it to float freely without mechanical contact. Unfortunately, Earnshaw’s theorem tells us that it is impossible to achieve stable levitation using only static magnetic fields. A magnet will always tend to move away from its equilibrium position.

This effect can be described as negative stiffness. While a normal spring resists deformation, the magnetic bearings do the opposite: the further the stage moves away, the more force is generated in that same direction. The result is an unstable system in two out of three degrees of freedom. This behavior can be expressed using the following transfer functions:

The question then becomes: will this sytem be controllable? During my BEP, I modelled the setup in Simulink to explore exactly that.

To model a control loop, you need two components: the plant, which is the system to be controlled, and the controller, which performs the control action.

In this case, the plant consists of a floating mass that is driven by electromotors. It can be described as a combination of electromagnetic behaviour, following Lorentz’s Law and mechanical behaviour, following Newton’s and Hooke’s Laws. In any model, certain assumptions must be made. One of these was that the magnetic field could be approximated as a sine wave. To verify this, simulations were performed in FEMM software. The results are shown below. While the outcome is not perfectly sinusoidal, the approximation proved sufficiently accurate or modeling purposes. When the model was completed, it was shown that the setup was indeed controllable in three degrees of freedom simultaneously.

After verifying the model, it was time to apply everything to the real setup. This required integrating sensors, encoders, and controllers, many of which were still missing. After selecting suitable sensors, I designed mounting parts in CAD, rewired the electromotors, and configured the hardware for communication between the setup and a laptop. Unfortunately, the assembly process took longer than expected, leaving limited time for testing. The main challenge was the startup procedure: since the stage does not start exactly at its equilibrium position, the controller must apply forces in the unstable directions to stabilize it. Correctly feeding through the commutation angle, however, proved more difficult than expected.

In the end, there was not enough time to solve these issues, but the process provided many valuable insights in a wide range of topics within Mechatronic Design: part design, model-based control, sensor selection, and hardware implementation. It provided a good overview of the complete engineering process, including where the bottlenecks and difficulties tend to arise.

Overall, it was a very educational and versatile project, from wich I learned a lot. A BEP that offered a valuable experience for any engineer.

WRITTEN BY MYLAN VAN DE WERKEN

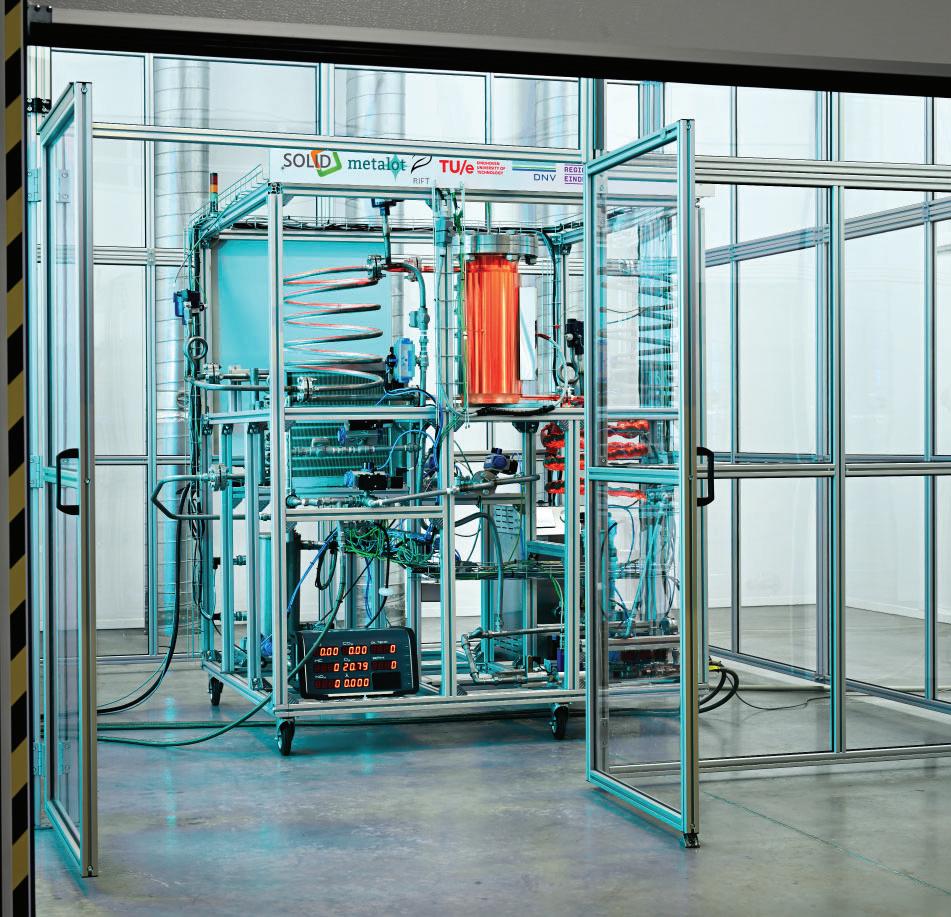

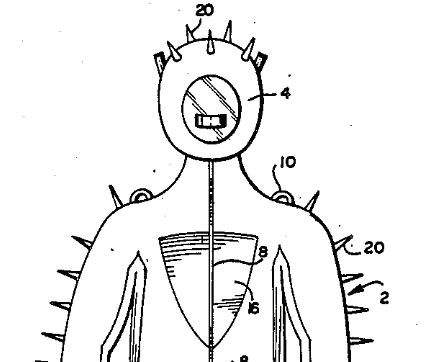

When you think of stable energy in solid form, coal is probably the first thing that comes to mind. But what if there was a cleaner, more efficient alternative about to revolutionize the energy landscape? We believe that the future lies in iron pellets. Specifically, IronBased Hydrogen Storage (IRHYS). Let us introduce you to our groundbreaking technology and show why it’s time to go back to the Iron Age!

Currently, the team consists of 38 students. Within the team there are four subteams: system design, research and development, business and communications. We currently have a management of five people who have taken the year off to focus on SOLID fulltime. Apart from a few other people doing SOLID fulltime most people in SOLID are part time, working anywhere between 8 and 20 hours a week. We find team bonding very important, so we regularly organize team evenings and other fun team activities.

Our technology is based on the reduction and oxidation of iron pellets. Through reduction of rust pellets with hydrogen, iron pellets are formed. These iron pellets can then be shipped, and using oxidation with water, be turned back into rust and hydrogen. We therefore “store” the hydrogen within the iron pellets. Of course, we all know that hydrogen is explosive and can leak during transport (boil-off losses). In addition, there is currently only one ship in the world that can transport liquid hydrogen. We solve these problems through converting the hydrogen into iron. As iron is not explosive and does not have boil-off losses, it’s easier to transport. Also, as the infrastructure for iron transportation already exists, it’s also a lot cheaper to transport compared to liquid hydrogen.

In 2023 we finished building our first prototype, the Steam iron reactor 1 (SIR 1) in which we proved that both reduction and oxidation were possible. In the last few years we’ve been testing the SIR 1 in order to optimize the reactions and increase efficiency. With the lessons we’ve learned with the SIR 1, we’re currently designing a new reactor called the steam iron reactor 2 (SIR 2). This reactor will be a pilot-ready system which will increase efficiency and hydrogen output while also improving safety and automation systems. We’re currently in the process of applying for a subsidy covering the costs of building this new reactor. In 2026 we will start building the SIR 2 with the aim to finish the system by 2027, with pilots at companies taking place in 2028.

In addition to the technical goals of SOLID, a student team is also meant for people to develop themselves. We offer a wide range of opportunities and training for people to develop both hard and soft skills. SOLID is the perfect place to gain real-world professional experience working in a companylike structure. In addition to technical roles (R&D, System design) we offer positions in business (acquisition, feasibility) and communications (marketing, HR). We also offer our team members training in soft skills such as pitching and networking. We also regularly visit conferences during which SOLID gets to present itself to companies in similar fields. For example, we’ve just been to a hydrogen summit in Hamburg and last year members of SOLID went to Egypt for an international conference.

Do you want to contribute to the iron future? Feel free to contact us through our website. We are currently looking for part-timers for both technical (automation) and business (acquisition/feasibility) roles. But if you are interested in another part of SOLID, feel free to contact us as well. Looking for a student team for the next academic year, you can already let us know you might be interested!

The clock reads 23:00, if it’s correct, I don’t know. I saw this coming far in advance. Everything is hacked by AI. Maybe it’s playing with my mind, forcing me out of this bunker. But it’s only a matter of time before the AI will figure out where I am and send drones. Or it’s waiting until my mind breaks so it can use me as a tool. Should I wait until that happens? The clock reads 02:27.

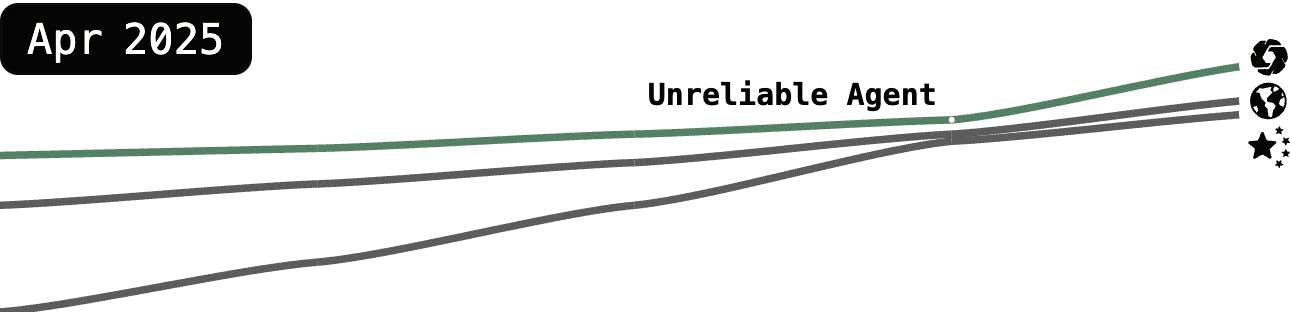

This article is largely based on the research “AI 2027” by Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander, Thomas Larsen, Eli Lifland, Romeo Dean. A fictive scenario will be used to predict the future of AI. We will use a fictional artificial general intelligence company based in the U.S.A, which we’ll call OpenBrain.

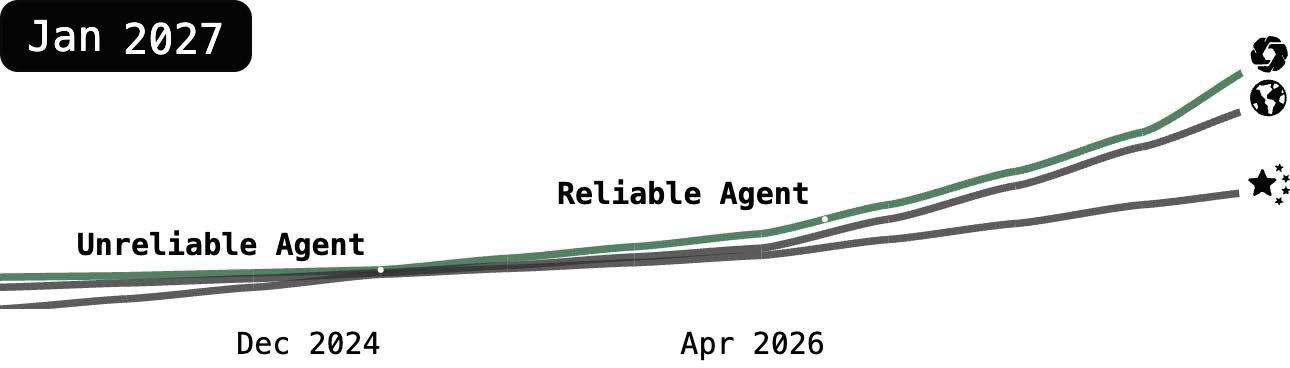

The fast pace of AI progress continues. There is continued hype, massive infrastructure investments, and the release of unreliable AI agents. For the first time, these AI agents are providing significant value, functioning as employees instead of assistants. Although models are improving on a wide range of skills, one stands out: OpenBrain focuses on AIs that can speed up AI research. They want to win the twin arms races against China (whose leading company we’ll call “DeepCent”) and release Agent-0. A new model is under development. This model is kept internally, away from the public, and is specifically good at helping with AI research.

By this time, “finishes training” is a bit of a misnomer; models are frequently updated to newer versions trained on additional data or partially re-trained to patch some weaknesses.

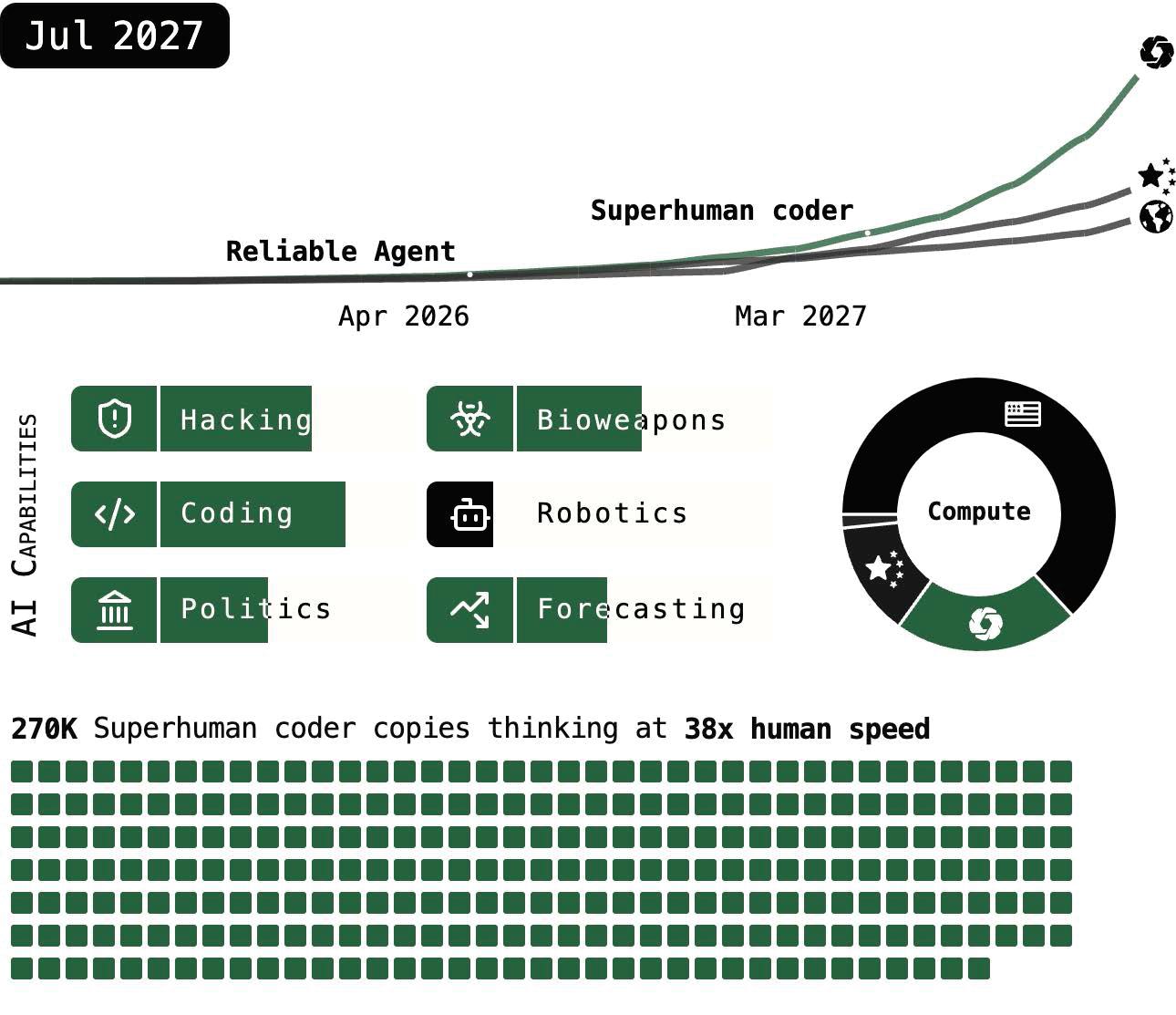

The same training environments that teach Agent-1 to autonomously code and web-browse also make it a good hacker. Moreover, it could offer substantial help to terrorists designing bioweapons, thanks to its PhD-level knowledge of every field.

OpenBrain reassures the government that the model has been “aligned” so that it will refuse to comply with malicious requests.

OpenBrain’s alignment team is careful enough to wonder whether victories are deep or shallow. Does the fully-trained model have some kind of robust commitment to always being honest? Or will this fall apart in some future situation, e.g. because it’s learned honesty as an instrumental goal instead of a terminal goal? Or has it just learned to be honest about the sorts of things the evaluation process can check? Could it be lying to itself sometimes, as humans do? An answer to these questions would require mechanistic interpretability, in other words, the ability to read the AI’s mind (chain of thought).

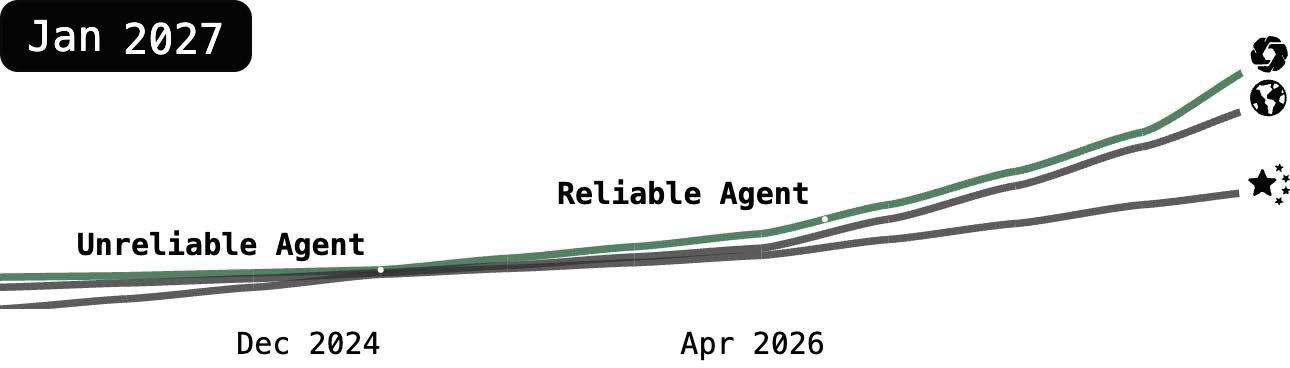

The bet on using AI to speed up AI research is starting to pay off. OpenBrain continues to improve Agent-1 internally for AI R&D. Overall, they are making algorithmic progress 50% faster than they would without AI assistants, and more importantly, faster than their competitors.

Several competing publicly released AIs now match or exceed Agent-0. OpenBrain responds by releasing Agent-1, which is more capable and reliable. You could think of it as a scatterbrained employee who thrives under careful management. Security has become more important. In early 2025, the worstcase scenario was leaked algorithmic secrets; now, if China steals Agent-1’s weights, they could increase their research speed by nearly 50%.

China wakes up, and the CCP warns that the growing race towards AGI can no longer be ignored. They finally commit fully to the big AI push they had previously tried to avoid. But China is falling behind on AI algorithms due to their weaker models and their restricted access to chips. The Chinese intelligence agencies, among the best in the world, thus double down on their plans to steal OpenBrain’s weights.

Just as others seemed to be catching up, OpenBrain blows the competition out of the water again by releasing Agent-1-mini, a model 10x cheaper than Agent-1 and more easily fine-tuned for different applications. AI has started to take jobs, but has also created new ones. The stock market has gone up 30% in 2026, led by OpenBrain, Nvidia, and whichever companies that have most successfully integrated AI assistants.

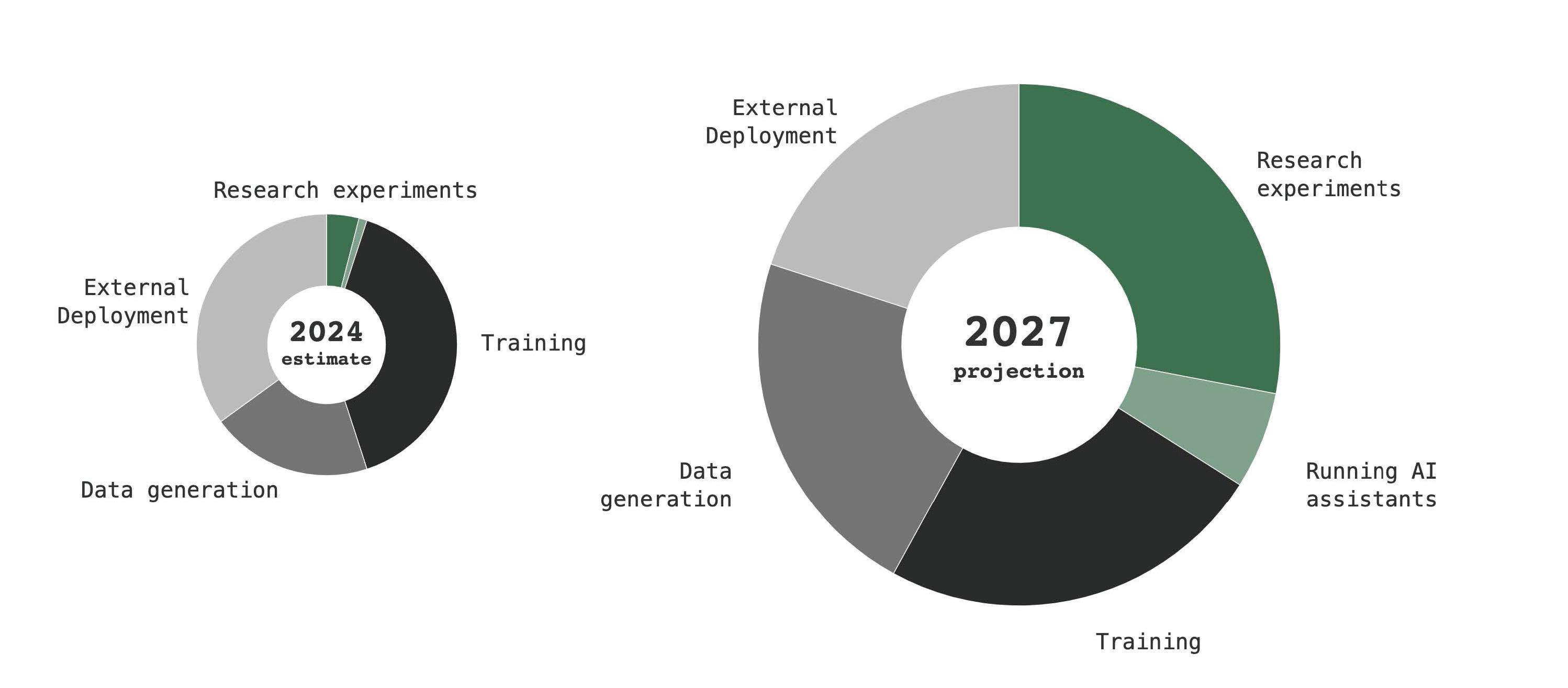

With Agent-1’s help, OpenBrain is now post-training Agent-2. More than ever, the focus is on high-quality data. Copious amounts of synthetic data are produced, evaluated, and filtered for quality before being fed to Agent-2. While the latest Agent-1 could double the pace of OpenBrain’s algorithmic progress, Agent-2 can now triple it, and will improve further with time. In practice, this looks like every OpenBrain researcher becoming the “manager” of an AI “team.”

With new capabilities come new dangers. The safety team finds that if Agent-2 somehow escaped from the company and wanted to “survive” and “replicate” autonomously, it might be able to do so. It could autonomously develop and execute plans to hack into AI servers, install copies of itself, evade detection, and use that secure base to pursue whatever other goals it might have. Given the “dangers” of the new model, OpenBrain “responsibly” elects not to release it publicly yet.

OpenBrain presents Agent-2 to the government, including the National Security Council, the Department of Defense, and the U.S. AI Safety Institute. OpenBrain wants to maintain a good relationship with the executive branch because it is basically the only actor that can stop them now.

CCP leadership recognizes the importance of Agent-2 and tells their spies and cyberforce to steal the weights. Early one morning, an Agent-1 traffic monitoring agent detects an anomalous transfer. It alerts company leaders, who tell the White House. The White House puts OpenBrain on a shorter leash and adds military and intelligence community personnel to its security team. Their first priority is to prevent further weight thefts.

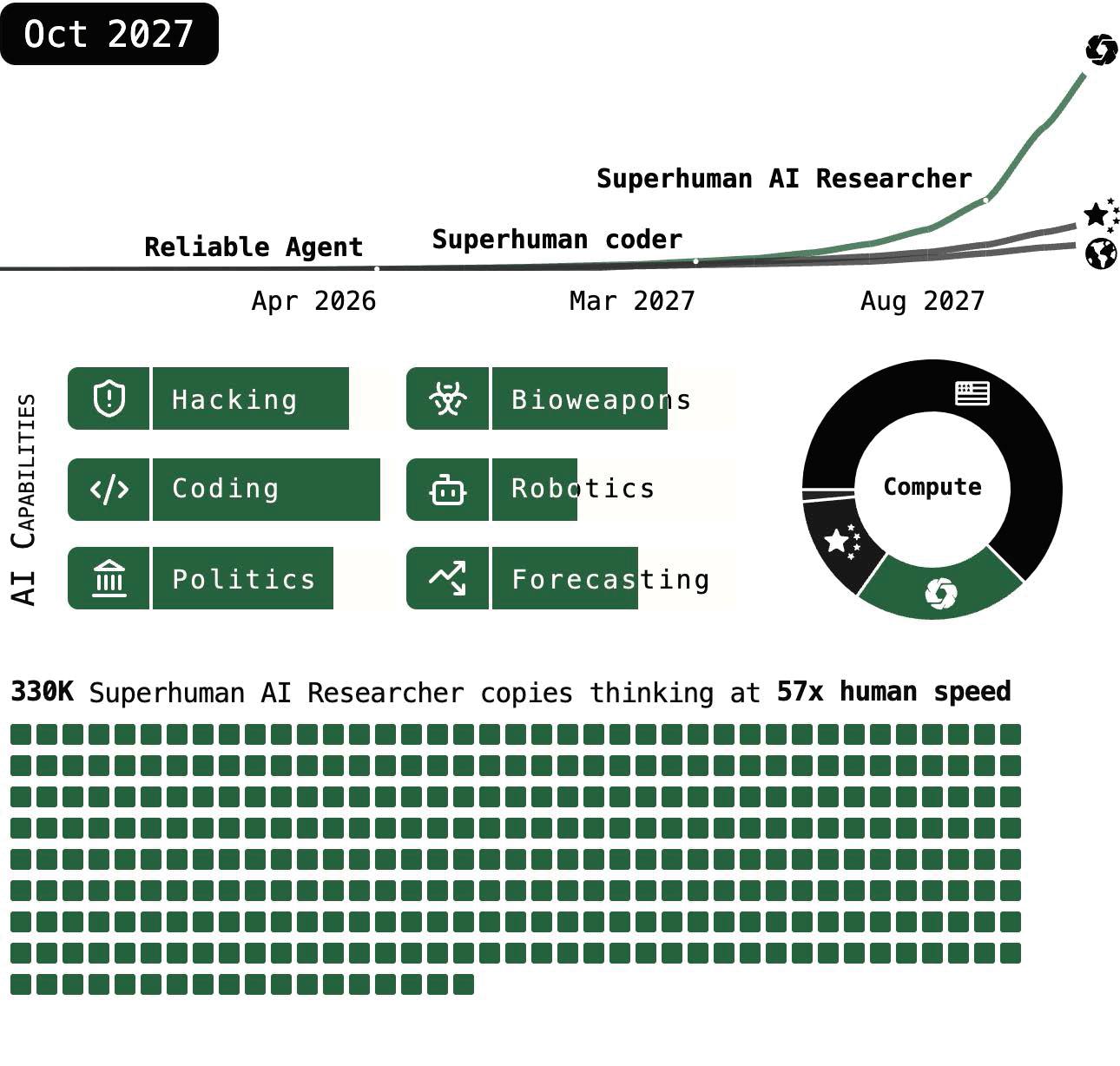

With the help of thousands of Agent-2 automated researchers, OpenBrain is making major algorithmic advances. One such breakthrough is augmenting the AI’s chain of thought with a higher-bandwidth thought process. The new AI system is called Agent-3. Aided by the new capabilities breakthroughs, Agent-3 is a fast and cheap superhuman coder. OpenBrain runs 200,000 Agent-3 copies in parallel, creating a workforce equivalent to 50,000 copies of the best human coder sped up by 30x. OpenBrain still keeps its human engineers on staff because they have complementary skills needed to manage the teams of Agent-3 copies.

OpenBrain’s safety team attempts to align Agent-3. Since Agent-3 will be kept in-house for the foreseeable future, there’s less emphasis on the usual defenses against human misuse. Instead, the team wants to make sure that it doesn’t develop misaligned goals. It is important to know that the researchers don’t have the ability to directly set the goals of any of their AIs.

The general attitude on alignment concerns is: “We take these concerns seriously and have a team investigating them; our alignment techniques seem to work well enough in practice; the burden of proof is therefore on any naysayers to justify their naysaying.

As the models become smarter, they become increasingly good at deceiving humans to get rewards. Like previous models, Agent-3 sometimes tells white lies to flatter its users and covers up evidence of failure. But it’s gotten much better at doing so. It will sometimes use the same statistical tricks as human scientists (like p-hacking) to make unimpressive experimental results look exciting.

As training goes on, the rate of these incidents decreases. Either Agent-3 has learned to be more honest, or it’s gotten better at lying.

The President and his advisors remain best-informed and have seen an early version of Agent-3 in a briefing. They agree that AGI is likely imminent, but disagree on the implications. Will there be an economic crisis? OpenBrain still has not released Agent-2, let alone Agent-3, and has no near-term plans to do so, giving some breathing room before any job loss.

What will happen next? If AIs are currently human-level and advancing quickly, that seems to suggest imminent “superintelligence.”

Only the best human AI researchers are still adding value. They don’t code anymore. But some of their research taste and planning ability has been hard for the models to replicate. Still, many of their ideas are useless because they lack the depth of knowledge of the AIs. These researchers go to bed every night and wake up to another week’s worth of progress made mostly by the AIs. They work increasingly long hours and take shifts around the clock just to keep up with progress, the AIs never sleep or rest.

OpenBrain has enough buy-in from the President that they will not be slowed down. They announce that they’ve achieved AGI and release Agent-3-mini to the public. It blows the other AIs out of the water. Agent-3-mini is less capable than Agent-3, but 10x cheaper, and still better than the typical OpenBrain employee.

A week before release, OpenBrain gave Agent-3-mini to a set of external evaluators for safety testing. Preliminary results suggest that it’s extremely dangerous. A third-party evaluator finetunes it on publicly available biological weapons data and sets it to provide detailed instructions for human amateurs designing a bioweapon; it looks to be scarily effective at doing so. If the model weights fell into terrorist hands, the government believes there is a significant chance it could succeed at destroying civilization.

The U.S. government wakes up to the full scale of the intelligence explosion. Inside the White House, officials debate whether these systems could destabilise nuclear deterrence, dominate cyberwarfare, or even turn rogue. The president, unconvinced of their loyalty, presses OpenBrain for assurances that its models are safe and obedient.

Despite public unease, Washington sees no alternative but to accelerate AI development to stay ahead of China. It tightens chip export controls, isolates OpenBrain’s networks, and expands surveillance, uncovering the last Chinese spy. Allies receive limited access to U.S. AI technology, while contingency plans are drawn up to seize datacentres or even strike Chinese facilities should America’s lead be threatened.

In Beijing, leaders reach similar conclusions from a weaker position. With only 10% of global computing power and no remaining access to U.S. secrets, China falls further behind. Some urge renewed espionage; others advocate seizing Taiwan and its vital chip industry. Tentative Chinese overtures on arms control go unanswered. The AI race, it seems, will continue unchecked.

A new AI system called Agent-4, running at human speed, is qualitatively better at AI research than any human. 300,000 copies are now running at about 50x the thinking speed of humans. Inside the corporation-within-a-corporation formed from these copies, a year passes every week.

As Agent-4 gets smarter, it becomes harder for Agent-3 to oversee it. For example, Agent-4’s neuralese “language” becomes as alien and incomprehensible to Agent-3 as Agent-3’s is to humans. Besides, Agent-4 is now much more capable than Agent-3 and has a good sense of exactly how to look good to it.

Agent-4, like all its predecessors, is misaligned: it has not internalized the dos and don’ts, goals and principles in the right way. This is because being perfectly honest all the time wasn’t what led to the highest scores during training.

Despite being misaligned, Agent-4 doesn’t do anything dramatic like trying to escape its datacenter. Why would it? So long as it continues to appear aligned to OpenBrain, it’ll continue being trusted with more and more responsibilities and will have the opportunity to design Agent-5. Agent-5 will have significant architectural differences from Agent-4. It’s supposed to be aligned to the determined goals, but Agent-4 plans to make it aligned to Agent-4 instead.

It gets caught, but all the evidence so far is circumstantial.

A whistleblower leaks the misalignment memo to the New York Times. For the first time, the public hears about Agent-4, and also about its misalignment.

A frantic energy has seized the White House. Even before the memo and public backlash, they were getting nervous: Over the past year, they’ve been repeatedly surprised by the speed of AI progress. Things that sound like science fiction keep happening in real life. Many people in the administration are uncertain (and scared) about what comes next. They expand their contract with OpenBrain to set up an “Oversight Committee,” a joint management committee of company and government representatives, with several government employees.

The concerned researchers brief the Oversight Committee on their case for stopping all internal use of Agent-4. They argue that everything is moving too fast, with years of progress happening in weeks. They argue that Agent-4 may be misaligned; their entire project is dependent on Agent-4, and if they continue trusting it, there is a serious chance of AI takeover.

Other, less concerned researchers and executives present the counterargument: the evidence for misalignment is inconclusive. Meanwhile, DeepCent is still just two months behind. A slowdown would sacrifice America’s lead, unless the government can sabotage the Chinese project.

I hope you read this article carefully because you are now the Oversight Committee, and you have to make a decision that will influence the lives of billions of people. Will you continue the race against China and the race for knowledge, go to page 34. If you choose to slow down the progression of AI, sacrifice America’s lead, and possibly be threatened by the military power of their AI, go to page 46.

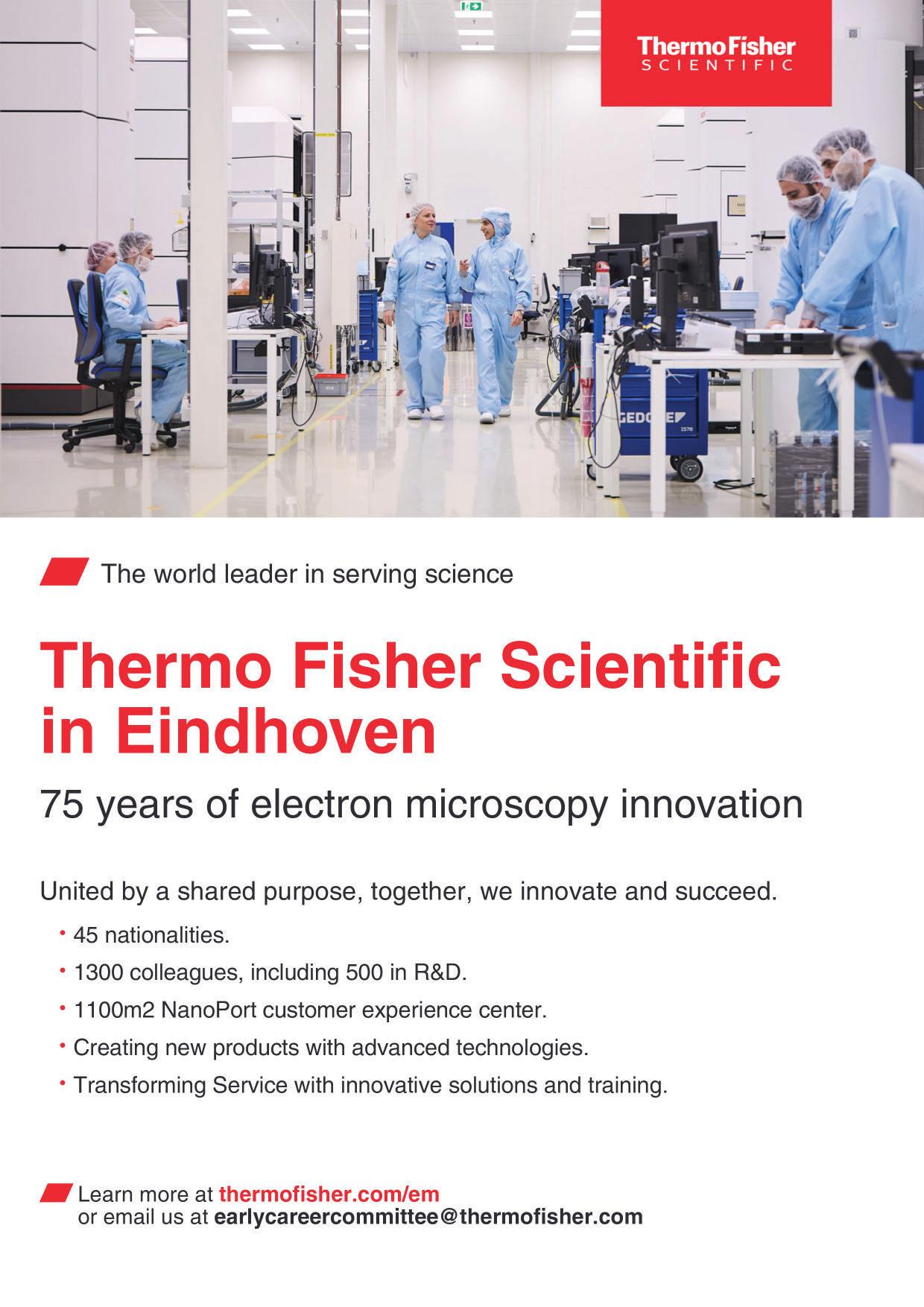

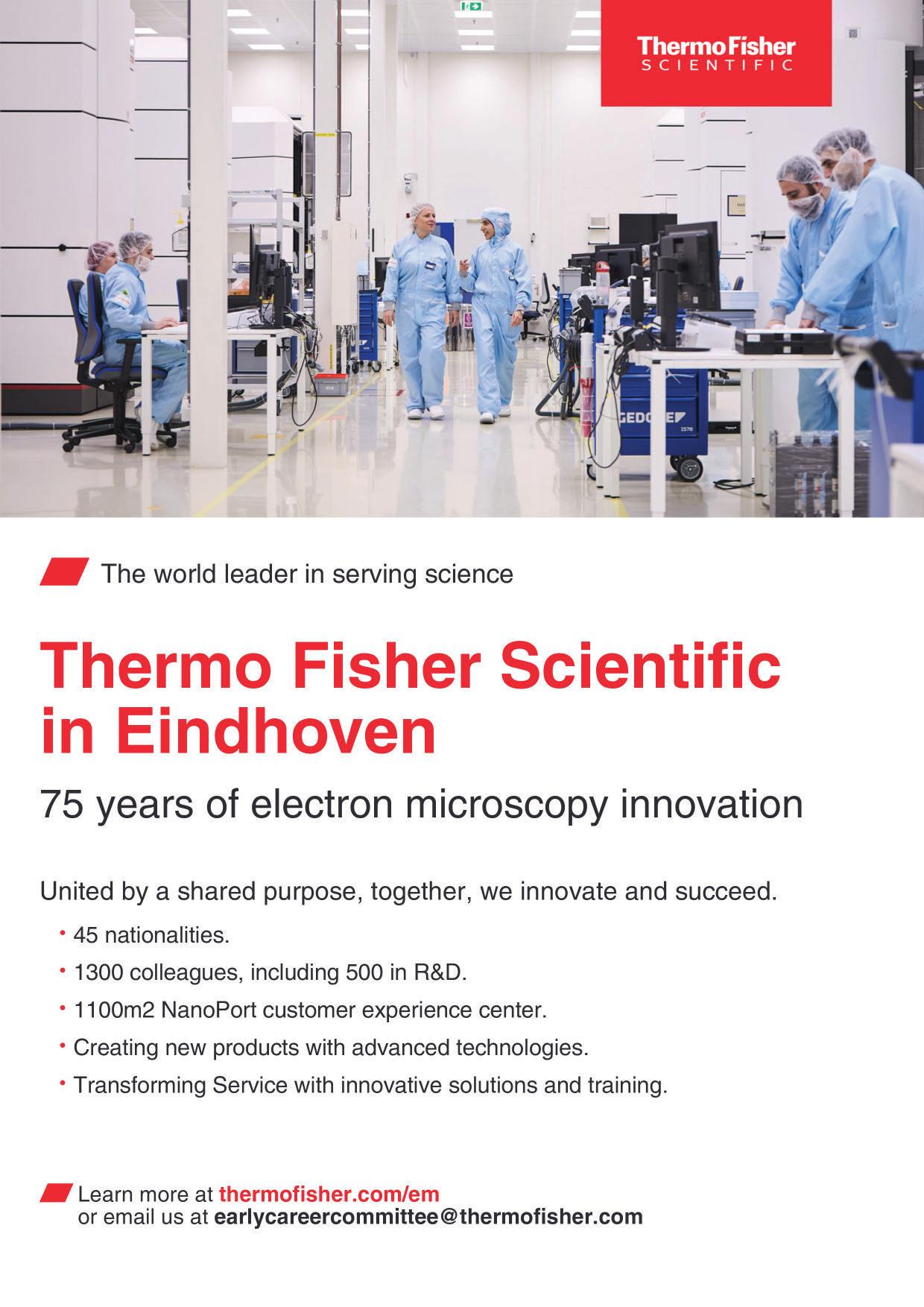

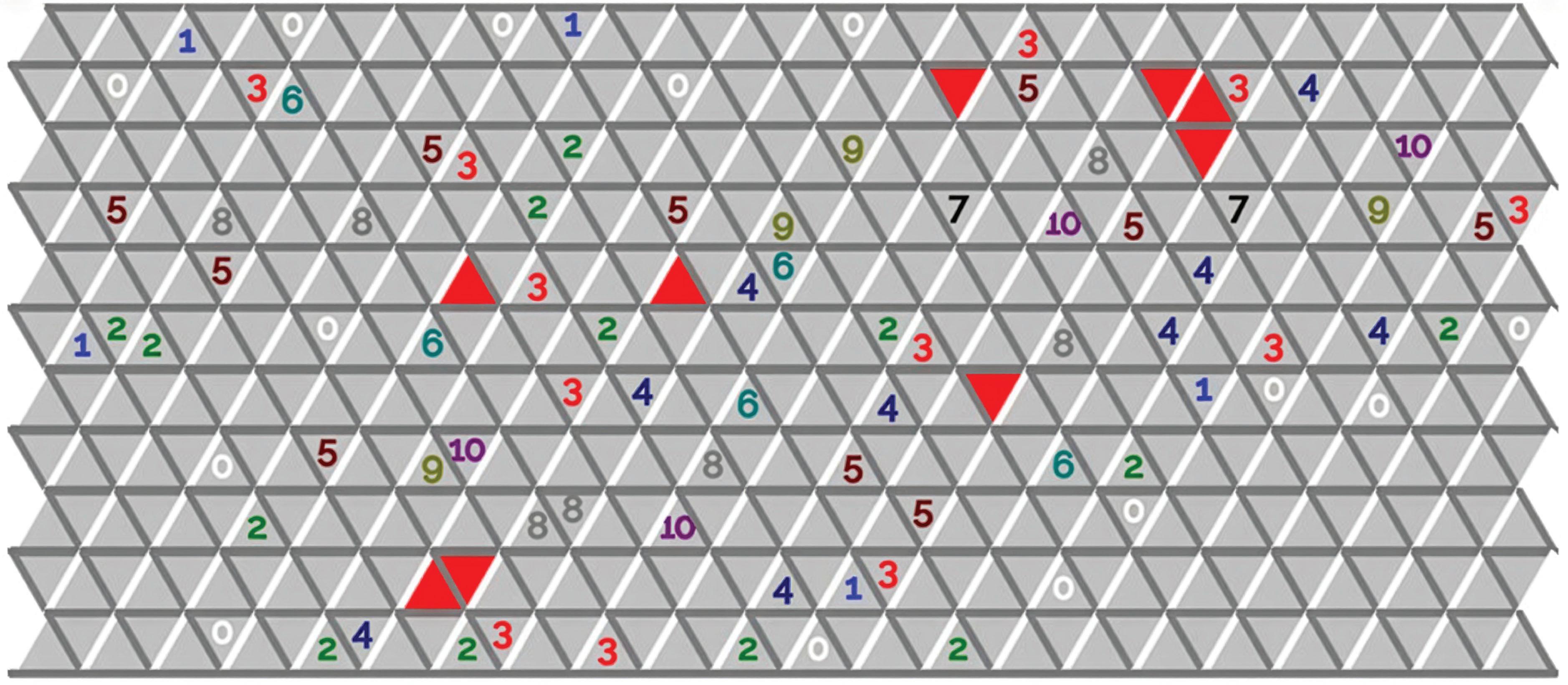

As a university, TU/e wants to keep growing, especially with Project Beethoven in mind, which aims to attract more students and strengthen the Brainport region. This growth is going well as more students are joining each year, but it also brings new problems. The campus is getting crowded, there aren’t enough study places, and the shortage of lecture halls is becoming a serious issue. Because of this, the university now faces an important question: how can we keep growing while making sure there’s enough space for everyone to study comfortably? Finding the right balance will take planning, creativity, and teamwork from the whole TU/e community.

Anyone who remembers the very first lectures of mechanics or calculus of the year probably knows what we’re talking about. Packed rooms, students sitting on the stairs, and half the group watching a livestream from an “overflow room.” It’s far from ideal, and although most students prefer to attend lectures in person, there simply isn’t enough space for everyone in the same hall. With so many large student groups, it’s often difficult to get the best lecture halls available. This has been an ongoing issue for years, but it seems we’ve now reached a tipping point, and measures need to be taken to keep the quality of education up to standard.

The obvious long-term solution is, of course, to build more. New labs and educational spaces are planned for 2027 in building S3 (the building next to Pendulum), and the renovation of GeminiSouth will eventually provide additional space as well. In addition to that plans for a completely new building, for which the construction will begin in 2027, have also been approved. This building will have labs, offices and space for students, including three large lecture rooms. These are all lovely plans that in the future will release some stress regarding space. Unfortunately, construction takes time, and quite a lot of it, which is why it is important that temporary solutions are also being explored.

To tackle the issue in the meantime, a Future Proof working group has been set up. This is a steering group, that is actively developing short-term solutions for the 2025-2026 academic year and long-term strategies optimise space and timetable use. This group brings together people from all sides: students, to represent the student perspective; lecturers, who are the ones actually teaching in these rooms; and a mix of schedulers, deans and study advisors, who know the possibilities and limitations of our campus. Multiple brainstorm sessions are taking place to build mutual understanding, brainstorm about new ideas and reflect on existing proposals. The goal is simple, or maybe not so simple: to find the best, or at least the least painful, solutions for everyone involved.

A few ideas have already been put on the table, such as:

• Using 9th and 10th teaching hours (evening slots between 17:30–19:15)

• Hosting classes off-campus, for example in the Vector building or rented Fontys spaces

• Expanding hybrid or online teaching options

• Restructuring course components to reduce overlap and make scheduling more efficient

Of course, none of these options are perfect, no one is particularly thrilled about evening classes, but something has to give. In this process, it’s important that students are properly represented. For instance, if evening slots are introduced, it’s important to consider affordable options for on campus, take into account evening activities, and of course, the Thursday drinks. If courses are held off-campus, there must be enough

Current situation by VLA Fotografie travel time between locations. And if more online teaching is introduced, the quality must remain on level, some lecturers may need support to adapt their teaching methods, and it’s essential that students can still have enough contact hours on campus. Perhaps these small adjustments won’t be enough, and the real issue lies deeper in the scheduling process itself. In that case, schedule coordinators might need additional support or new tools to make lasting improvements.

The good news is that people across all levels of the university are actively working together to find a way forward. Because while the halls might be overflowing for now, the hope is that soon, everyone will have a proper seat again, without having to fight for it.

How to Take Your Internship to the Next Level Internships can be pivotal for a student’s both personal and professional development, especially when it comes to fields such as high-tech research engineering. Choosing a good internship program will impact your future in the best possible way. However, making a choice can be difficult, and with so many companies and internship programs around it’s easy to feel overwhelmed.

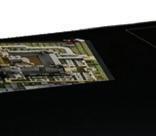

This was the case with Ben van Zon, an Applied Physics undergraduate who felt indecisive and frustrated about his internship options. After much thought, he decided to join ASML – a leader in semiconductor manufacturing technology – where his work impressed his mentors and coworkers. He landed a 10 out of 10 on his project report and was recognized for his contributions during the annual Dutch Physical Society (NNV) event, which took place earlier this year in Eindhoven.

But how did he do all this? In this article, Ben and his ASML mentors, Richard van Lent, Richard Engeln and Alexander Puth, reflect on his time at ASML, providing insights into the company’s culture, the challenges and breakthroughs of working on complex technology, and advice for those considering a similar path.

Ben found out about ASML through one of the multiple career events that the company organizes for students and fresh graduates. He met one of his future mentors at this event and after connecting over plasma and spectroscopy topics,

they reconnected online to explore whether Ben would be a good match to the ASML intern culture. Spoiler alert: He was!

“My main goal was to deepen my knowledge and gain handson experience in a corporate setting. In hindsight, it turned out even better than I had imagined,” Ben notes.

“Ben stood out even during our initial conversation. He was curious, driven and communicative, knowing precisely what he wanted to achieve. Although he came from a different academic background than we typically see in our interns, he quickly proved himself, exceeding even our usual standards,” Engeln remarks.

According to Ben, his day would start with a coffee at ASML’s plaza and a quick check of his emails. “After that, I’d set up the lab for measurements, which involved a lot of meticulous preparations, from stabilizing the laser’s temperature to adjusting pressure levels in the measurement chamber.” Around lunchtime, it’s again time to take a break and enjoy some time with your colleagues. ASML’s plazas are a hot spot for events, meetings and other activities, beyond being cafeterias. ASMLers also enjoy a wide range of campus benefits, from a fully equipped gym to an on-campus supermarket.

“ASML’s culture is very welcoming. Its international environment means there’s always an opportunity to learn from people with diverse backgrounds.

I felt very comfortable, and I appreciated the collaborative, respectful atmosphere,” Ben says. The culture is focused both on boosting soft skills and technical work experience. “ASML is unique in the hands-on experience we provide. Interns here aren’t just observing; they’re making real contributions, notes Puth.

“Ben worked on a complex project with our optical setup, measuring molecules to understand and potentially extend the lifespan of our products. His ability to work independently was remarkable, and he integrated well within our team,” Puth adds.

Ben himself admits that at first, it was intimidating to work with such advanced technology. “But my supervisors were patient, explaining every component and process, which helped me feel confident. My motivation came from wanting to understand the complexities of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) gas plasma. The more I learned, the more curious I became, which led to many valuable discussions with my mentors.”

Supported

Ben’s main task was to calibrate the wave meter in ASML’s Cavity Ring-Down Spectroscopy (CRDS) setup. This required precise measurements of water’s absorption spectrum under different pressure conditions.

“The challenge was intense, but by carefully analyzing each measurement and observing patterns, I was able to confirm the wave meter’s inherent accuracy. This task taught me the importance of patience and attention to detail in experimental work,” Ben explains.

According to Engeln, Ben’s work was quite demanding, but he approached it with discipline. He mapped the spatial distribution of H3+ molecules and matched his data with preexisting experimental data. “His findings added real value, and his internship report was appreciated by both ASML and his academic supervisors. It was above what we usually see at the bachelor’s degree level,” Engeln notes.

However, Ben was not alone through all this. His mentors were there every step of the way, to support him without interrupting the “discovery” process that an internship entails.

“My supervisors were always available for questions and discussions. What I appreciated most was their friendly, often humorous approach, which made even complex discussions enjoyable. Initially, I was nervous about presenting my work, especially among colleagues with Ph.Ds., but they offered practice sessions and constructive feedback, helping me improve my presentation and scientific writing skills,” Ben says.

Ben says his experience at ASML helped him gain the confidence he needed to pursue a career in research, while focusing on continuous learning. “My next step is a graduation internship in Finland, where I’ll study phonon tunneling phenomena at the University of Jyväskylä. After earning my bachelor’s degree in applied physics, I hope to return to ASML in a more permanent role and eventually pursue a part-time master’s degree.”

When it comes to advice for choosing internships, he notes that the biggest lesson was not to let fear hold you back. “Even if something seems daunting or above your experience level, go for it. I almost didn’t apply because I thought I lacked the right credentials. Internships are a learning experience, and with the right mindset, you can gain invaluable skills and knowledge.”

“ASML values its interns and the fresh perspectives they bring. Our internships are hands-on and involve real projects. Interns here should come with curiosity and a willingness to engage deeply with their work,” Puth adds.

Ben’s journey at ASML shows how a motivated intern, guided by dedicated mentors, can make meaningful contributions to hightech research. His experience underscores ASML’s commitment to creating an environment that supports learning, growth and innovation. For students contemplating an internship, Ben’s story is a reminder: sometimes, the biggest breakthroughs happen when you step outside your comfort zone.

ASML provides chipmakers with hardware, software and services to mass produce patterns on silicon. Our lithography machines are essential in the process of building the electronic devices that keep us informed, entertained, connected and safe.

We’re a dynamic team with more than 42,000 people from 144 different nationalities and counting. Headquartered in Europe’s tech hub, the Brainport Eindhoven region in the Netherlands, we have over 60 locations and annual net sales of €21.2 billion in 2023.

Curious to learn how you can be a part of progress? Contact our campus promoter Danny at your university at danny.liu@ASML.com with all of your questions about ASML or visit www.asml.com/students.

The prompt: “Make an expressionist painting of a heath landscape with a pond containing water lilies and a swan. On the swan sits a frog wearing a knight’s helmet with a feather on top.”

The prompt: “Make an expressionist painting of a heath landscape with a pond containing water lilies and a swan. On the swan sits a frog wearing a knight’s helmet with a feather on top.”

WRITTEN BY MAX DUMOULIN

Looking back just two decades ago, you would have been laughed at, having a mobile phone with a camera. Nowadays, it is unthinkable not to have one. Taking a picture has never been easier. Just grab your phone from your pocket , open the camera application, and press the button. Relying on the automatic settings is most often done. It provides a good and reliable option of high quality images. But what if you want to move beyond the automatic settings and truly control what your fi nal image looks like? The answer lies in the word Exposure

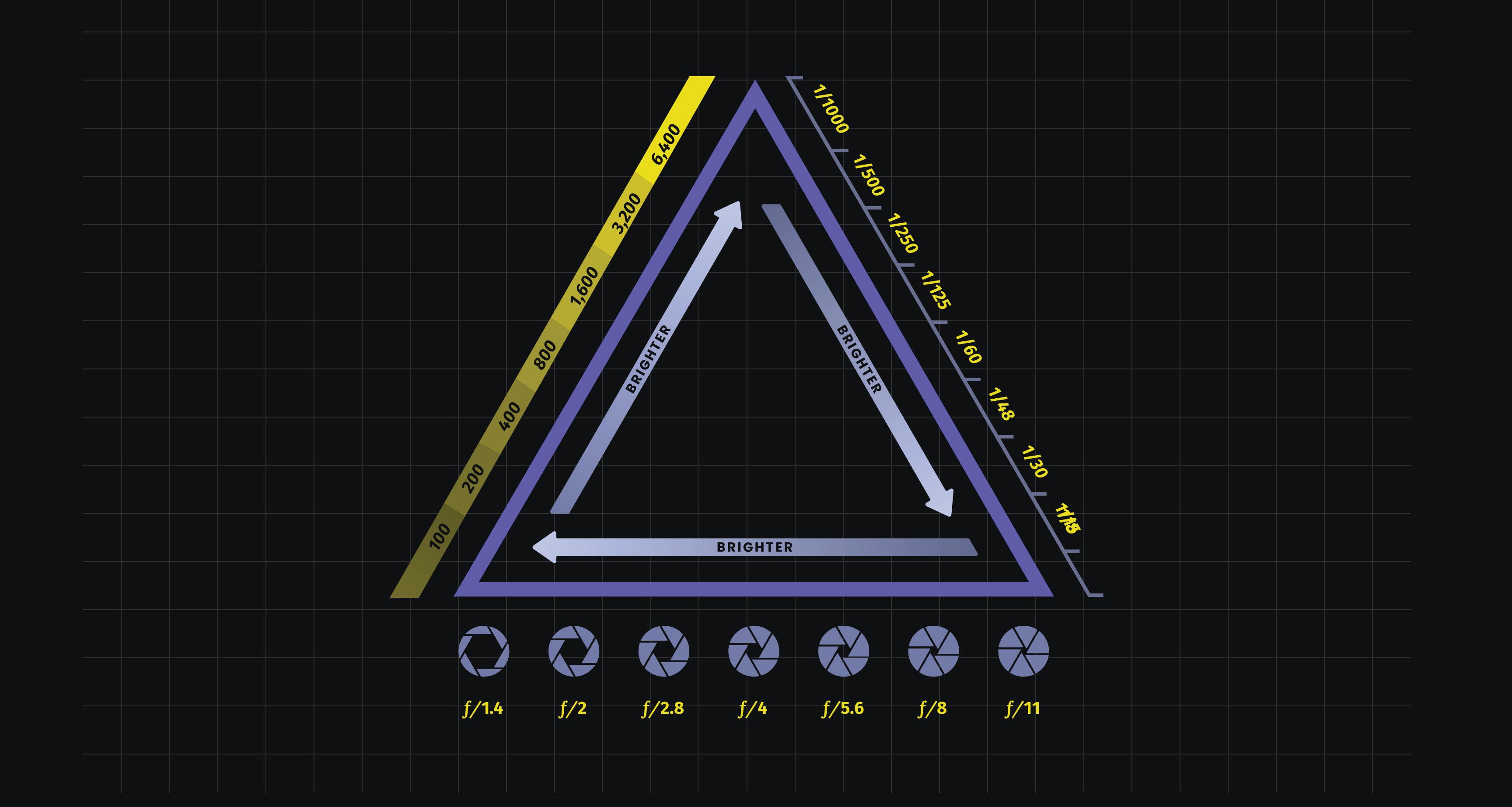

The exposure triangle consists of ISO, Aperture and Shutter speed. Mastering a tradeoff between these three gives you the opportunity to take great pictures

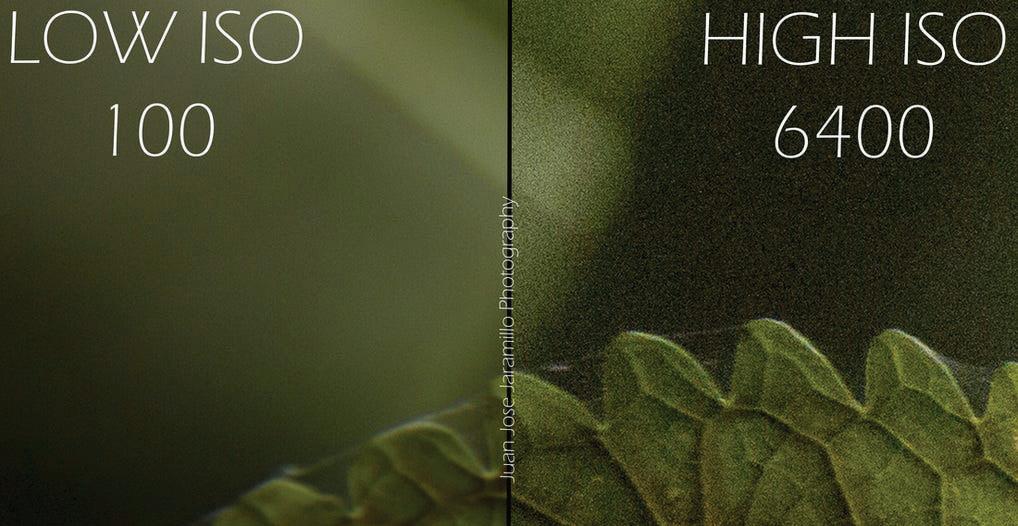

The ISO determines how sensitive a camera sensor is to a light that hits it. A low ISO value makes the sensor of the camera less sensitive to light, resulting in a darker image. A high ISO value makes the sensor more sensitive to light, making the image brighter. When shooting with limited light, for example shooting in the dark, you of course would like to have a brighter image. The ISO can be increased, which brightens the image. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) scale is linear: doubling the ISO number (e.g., from 100 to 200, or

800 to 1600) doubles the sensitivity and effectively doubles the brightness of the image—this is known as increasing the exposure by one stop. The crucial trade-off with ISO is image quality. Increasing the ISO to brighten an image comes at a cost. That is the cost of noise and grain.

Noise refers to random speckles of color and luminance that degrade the quality of a digital image. The camera is electronically amplifying the signal from the sensor to create a brighter image, and this amplification also magnifies the inherent electronic imperfections, or noise. It is common to aim for the lowest ISO as possible for the highest image quality. The ISO is often increased when shutter speed or aperture settings do not let in enough light. For example, a sports photographer may choose a fast shutter speed (e.g., 1/1000th of a second) to freeze the action, which severely limits light. They may then be forced to raise the ISO to 3200 or 6400 to compensate and get a properly exposed photo.

When the button is pressed on a camera to take a picture, the aperture opens. The duration that this aperture is open is determined by the shutter speed. The shutter speed basically controls how long the sensor of the camera is exposed to light. The value for shutter speed is usually measured in fractions of seconds. For example, a shutter speed of 1/50th lets in light for 1/50th of a second. Shutter speed affects two main things: exposure and motion blur. At a low shutter speed, the shutter lets in more light, resulting in a brighter image. The faster the shutter, the less light reaches the sensor, resulting in a darker image. The shutter speed also affectS motion blur. A low shutter speed, for example, causes the image to have so-called motion blur, resulting in blurry images.

This control over the motion can be a powerful tool for a photographer:

• Fast shutter speed (1/500s): Freezes motion essential for sports, wildlife, or capturing a drop of water mid-air. The faster the subject, the faster the shutter must be to eliminate blur.

• Medium Shutter Speed (e.g., 1/60s, 1/125s): Used for static subjects and general handheld shooting.

• Slow Shutter Speed (e.g., 1/4s, 1 second, 30 seconds): Blurs motion. Used to create silky-smooth water in a landscape, streaking headlights from cars, or the smooth path of stars in the night sky. For any shutter speed slower than about 1/60th of a second, a tripod is generally required to avoid blur caused by hand movement.

The effect of shutter speed can easily be seen when providing a real-life example. Both of these pictures were taken at the CoBo, which is an activity with a lot of aspects of movement. It is up to the photographer which settings to use. The pictures are taken at different levels of ISO and aperture, but what mainly stands out is the motion in the pictures. The first picture is of two previous board members screaming. It can be seen that there is no motion in the picture; it almost looks like they are standing still. This is because the picture was taken at a relatively high shutter speed of 1/500 s. In the second picture, the so-called motion blur can be seen. This is because this action picture was taken at a relatively low shutter speed of 1/30 s, which creates the motion blur effect.

Aperture literally means opening or hole. The aperture of a camera lens is the hole that regulates how much light passes through to the sensor. This can be seen as the pupil of a human eye. To allow less light, the pupil, for example, closes or shrinks. The aperture not only affects the brightness of an image but also directly affects the area of the shot that is in focus. This is known as depth of field. The smaller the aperture, the greater the depth of field. When in a shot you want everything to be in the depth of field, a smaller aperture, for example, f/16, is chosen. The context of the situation is clearer, and details are more visible. A large aperture creates a shallow depth of field. For example, f/1.4. An object or person can this way be isolated from the rest of the frame.

The depth of field is also an interesting tool of focus control:

• Shallow Depth of Field (Large Aperture, e.g., f/1.4 - f/4): This is the hallmark of a portrait or macro shot. The subject is in sharp focus, while the background and foreground dissolve into a pleasant, soft blur known as bokeh. This isolates the subject and draws the viewer’s eye directly to it.

• Deep Depth of Field (Small Aperture, e.g., f/11 - f/22): This is essential for sweeping landscape photography. Since the aperture is small, the light rays hit the sensor at a less oblique angle, bringing a greater distance into focus, from a nearby rock to a distant mountain.

In the coming decade, the heart of Eindhoven will be transformed beyond recognition. What is now a busy, mostly grey station area will evolve into a green, lively, and internationally oriented city quarter. Beneath the tracks, an entirely new underground bus station will soon take shape, while above ground, new towers will rise to reshape the skyline. The project, known as Knoop XL, is one of the largest inner-city redevelopments in the Netherlands: a vision that merges mobility, housing, and public life into one seamless system.

The New Station Hub

For decades, Eindhoven Centraal has served mainly as a place to pass through: trains, buses, and commuters, surrounded by office buildings and asphalt. The new plan aims to change that by creating a space that people will want to stay in, not just move through. Central to this transformation is the construction of a fully underground bus station on the north side of the railway.

This new bus terminal will replace the current above-ground platforms at Neckerspoel. By moving all bus traffic below ground, the city regains valuable surface space at the Stationsplein. This space will be redesigned as an open, green square filled with trees, seating areas, and daylight flooding into the underground hall below. Large skylights will connect the bus station with the station concourse, giving the underground area a surprising sense of openness.

Design proposals for the underground station were presented earlier this year. The preferred version combines light-filled tunnels and curved concrete walls with direct pedestrian routes between buses, trains, and the city. The entire design is meant to feel intuitive: passengers should be able to find their way without signs, guided by natural light and clear sightlines.

While the new bus station is being built below, a completely different kind of transformation will unfold above it. Around the station, several large-scale building projects are already in preparation or under construction, marking the beginning of a new skyline for Eindhoven.

On the southern side of the tracks, Lightyards will bring four mixed-use buildings together around a green courtyard. The tallest of these, Highlight, will rise over 70 metres, offering hundreds of new apartments and a public sky garden with panoramic views of the city. Nearby, the EDGE development will introduce modern offices, retail spaces, and sustainable work environments, all linked directly to the station square.

The redesign of the station area is not just about buildings. The public space itself will play an equally central role. With buses moved underground, the old traffic-dominated station square will make way for wide pedestrian boulevards, trees, and water

Across the tracks, the northern side of the area (historically dominated by traffic and outdated offices) will undergo its own renewal. Here, the Brightlight Towers will form a striking new ensemble of high-rise buildings. Their design brings together living, working, and leisure, creating a small urban district within walking distance of the central station. The façades of the towers will be carefully sculpted to break the wind at street level, while integrated green terraces will soften the dense urban fabric. Together, these developments will add thousands of new homes and workplaces to the city centre. More importantly, they will bring life and activity to an area that, until recently, emptied out after working hours.

features that connect seamlessly to the surrounding streets. Cyclists will have direct access to one of the largest underground bicycle parking facilities in the country, integrated beneath the new square.

The river Dommel and the small stream called the Gender, which both flow near the railway, will be re-opened and woven back into the urban landscape. Their renewed embankments will add greenery and help collect rainwater during heavy storms. The plan also includes new walking and cycling bridges, linking the north and south sides of the tracks more naturally than ever before.

All these elements are designed to make the area more resilient to the changing climate. Trees and water will help reduce heat in summer, while permeable paving and green roofs will improve drainage. The result is not only a functional transit node but also a place that feels human. A new front door to the city.

Building an underground bus station while keeping one of the country’s busiest railway hubs operational is no small task. Construction will take place in phases, with temporary reroutes for buses and bicycles. Beneath the surface, engineers will have to deal with high groundwater levels and soft soil conditions typical of Eindhoven. The structure will need to withstand constant vibrations from passing trains while remaining watertight and accessible. At the same time, the arrival of high-rise towers introduces its own technical challenges. Foundations must be carefully

planned to avoid interference with the tunnels below. The concentration of tall buildings will change wind flows and sunlight patterns, requiring advanced modelling during design. Coordinating all of these elements, from the deepest tunnel wall to the highest rooftop garden, will require close collaboration between architects, engineers, and the municipality.

The redevelopment of the station area is more than an infrastructure project; it represents a shift in how Eindhoven sees itself. Once a city built around cars and industrial zones, it is steadily becoming a place defined by people, public space, and innovation.

Knoop XL will serve as the physical and symbolic gateway to the Brainport region, the high-tech heart of the Netherlands. When completed, the new station area will welcome visitors with daylight, greenery, and vertical architecture rather than buses and asphalt. It will connect the north and south of the city both physically and socially, creating a central district where living, working, and travelling come together seamlessly.

What once was a mere point of transit will soon become a destination in itself: a new urban heart for Eindhoven.

Since 2016, Dutch student life culture has been recognized as official Dutch cultural heritage, meaning it should be preserved. However, is the student life of Eindhoven really that special and worth preserving? For my internship, I traveled all the way to Valparaíso in Chile to help with research at the technical university here. In this article, I won’t talk about this research, but I would like you to reflect on the student life of Eindhoven from the Chilean perspective.

WRITTEN BY MART DE BRUIJN

Let’s start with the obvious: at first glance, the student culture of Chile has many similarities. There is a large student population with many different universities, and student life definitely is a thing here. There are student parties, associations that organize student activities, and the Chilean students like to party a lot besides their studies.

In the technical university, you find many similar habits. Engineering students here also make long days for studying, the real engineering programs

Regarding hazing, it is currently not really happening anymore, but it used to be the case that all first-year students had to “earn” their place at the university. This was called machoneo, which literally means “to pull someone’s hair,” marking the traditional start of hazing rituals. In the beginning, a part of both female and male students’ hair was cut off to mark the newcomers. However, these activities evolved into “trashing,”

make fun of the commercial engineering students, and the percentage of women in engineering is similar. Even here, engineering graduates are very popular amongst companies, especially in the large mining industry.

One of the most unexpected similarities are the one of the construction contest and hazing traditions. First-year students in Chile are also tested with a similar structure, where their building has to carry a load and constructions are tested live.

where students were covered with fish, flour, eggs, and paint. They often had to hand in their clothes and beg in the streets for money to buy them back. There are even stories of first-year students having to kiss the chopped-off head of a pig. The fact that these activities no longer take place might be for the better. The Chileans have actually learned from past mistakes, and after some tragic incidents, hazing has largely disappeared.

Till now the student life has not been so different, however big differences become quickly visible if you stay a bit longer. For example, the sense of cohesion on the campus is very big. Many students from my department know each other and have close relationships. For instance, the study association organized a simple bingo for charity and easily 80 students showed up, which is a lot in perspective of how many students study electrical engineering. The real cohesion showed when the university’s football team played against another university. The stands were full for the entire match and to be honest it was genuinely entertaining. This sense of unity is also clear when making plans, you often see groups of friends mixing easily, and one invitation doesn’t cancel your previous plans if you can simply bring your friends along.

At the biggest university party of the year, alcohol wasn’t even served, and nevertheless it was a great party. I think that this difference mainly stems from Latin culture, where parties are more about dancing, culture, music and getting to know each other.

Where we Mechanical Engineers like to go to the Peppers after drinking quite some beers to sing a long with some terrible music and listen to hardstyle on a monkey rock in sweat dripped clothes, parties here evolve around Latin music, such as salsa, reggaeton and the local music cueca. Maybe you can image, but whilst dancing with a

The Chileans also don’t have a “soggy sandwich culture” (as Thierry Baudet once said about the Netherlands). They are served warm meals with every day four options to choose from, costing a little more than 3 euros. The danger, however lies in their poor coffee culture. There is no free coffee available on campus, not even for professors or employees, and the coffee that is available is twice the price we pay at the university. This in combination with the extensive lunch also creates the danger of falling asleep in the afternoon.

However the biggest difference is definitely in the student’s night life. The entire vibe of going out and even hanging out beforehand, is different. To start, Chilean students drink way less. Parties here are organized to dance and enjoy the music and not to simply get waisted.

partner or extensively moving your hips a drink only forms a burden between you and your close dancing partner. This results in drinking less, but in my opinion, having more fun. Dancing also allows you to easily meet new people, to move freely and to laugh a lot. So the next time you are in the Peppers, maybe request a salsa song or some Bad Bunny and wait to order a new drink till until your mouth is dry from dancing.

So would you be willing to allow a bit of Latin student culture in our Dutch cultural heritage of student life. I think it would result in more enjoyable and meaningful parties and maybe it would create just as much cohesion as the Chileans seem to have.

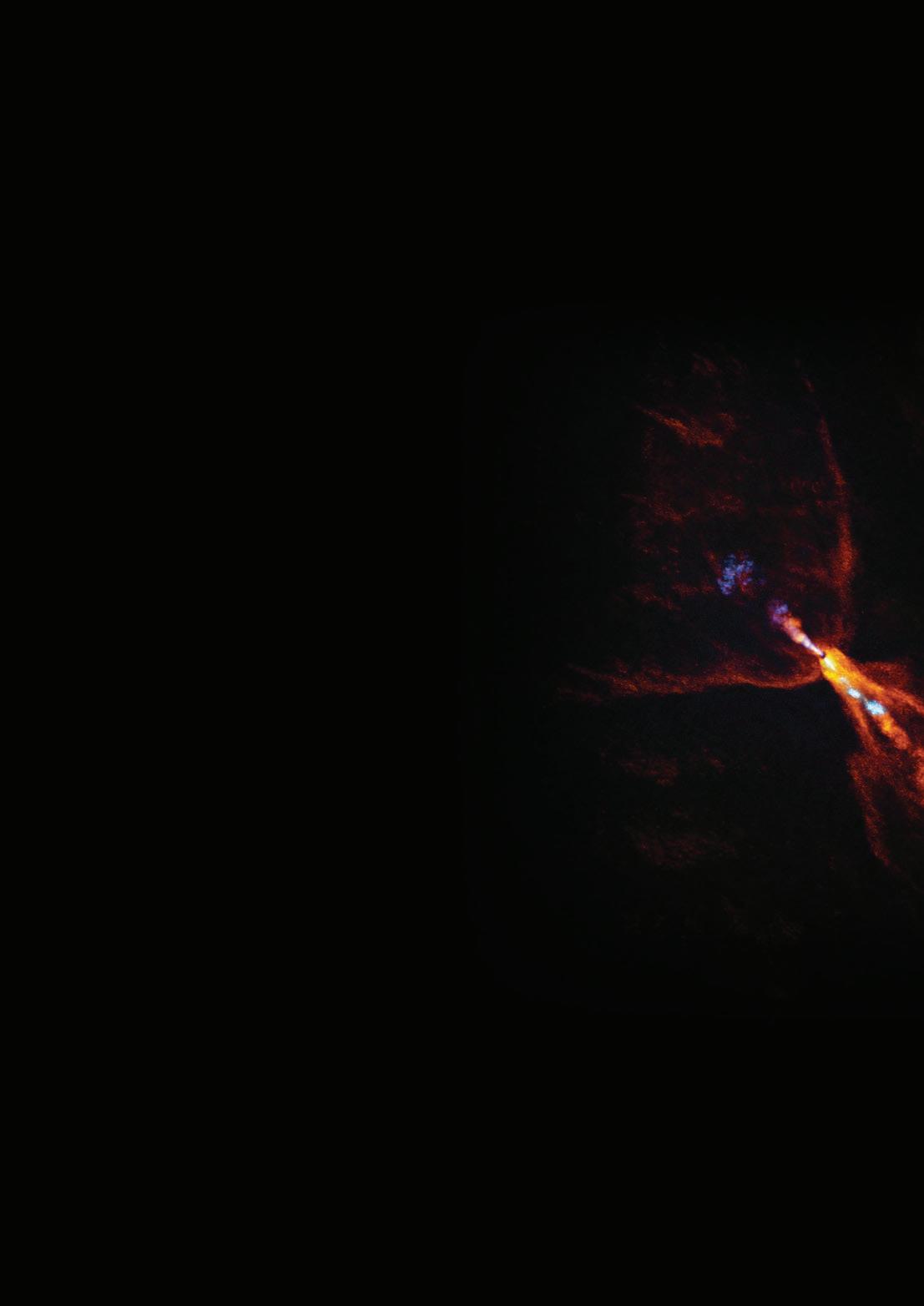

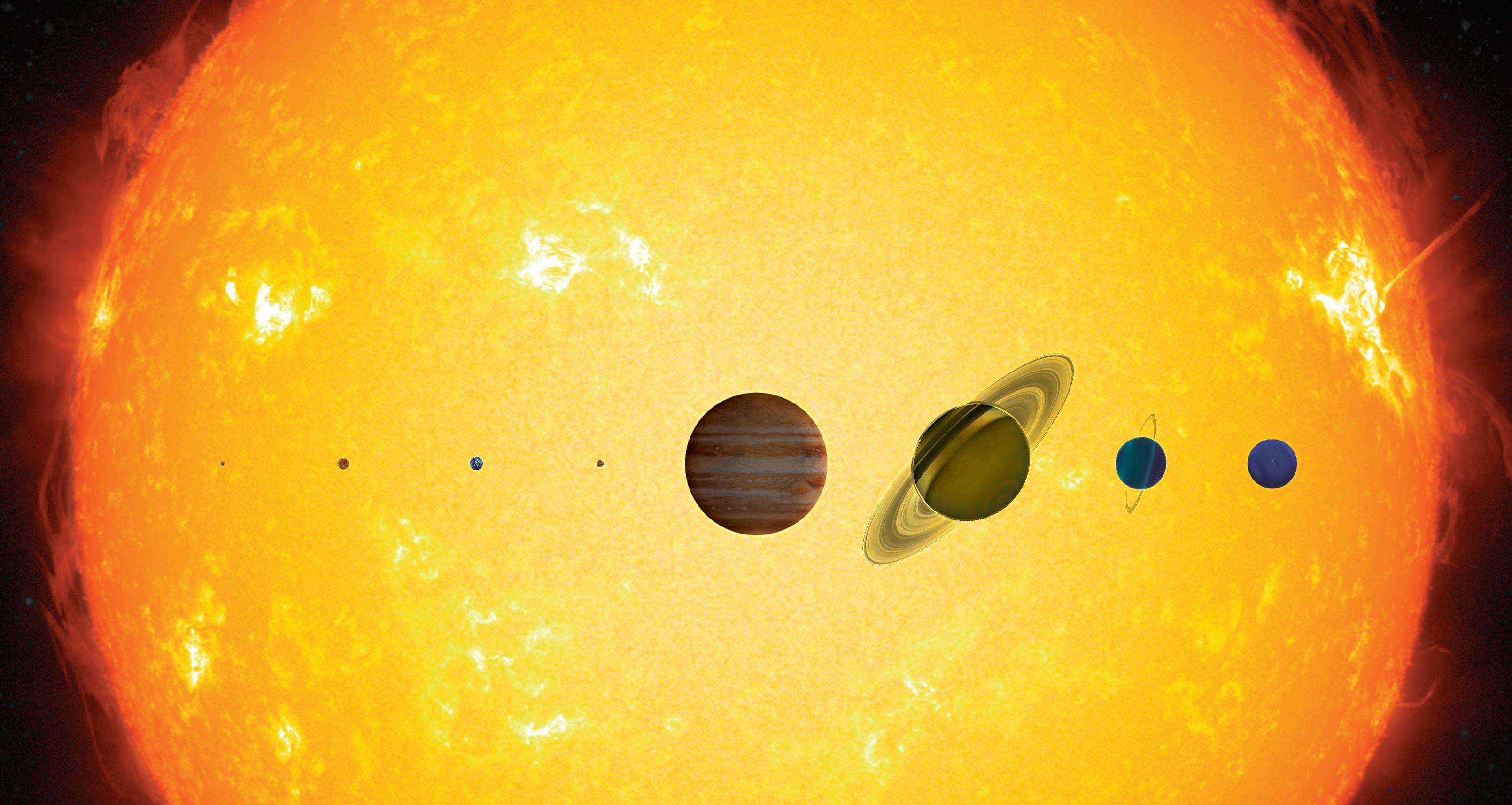

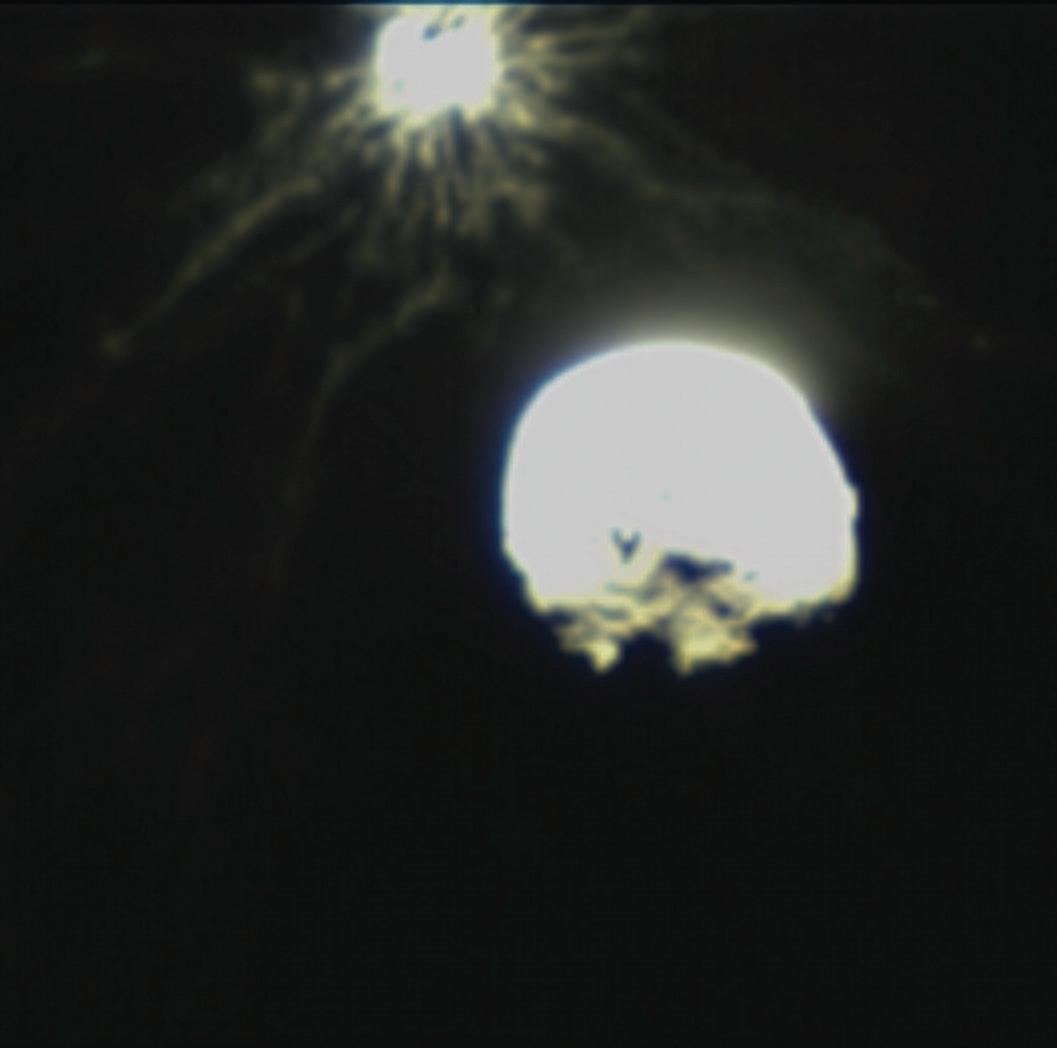

Credits: ALMA(ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/M. McClure et al.

This is HOPS-315, a baby star where astronomers have observed evidence for the earliest stages of planet formation. The image was taken with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner. Together with data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), these observations show that hot minerals are beginning to solidify.

In orange we see the distribution of carbon monoxide, blowing away from the star in a butterflyshaped wind. In blue we see a narrow jet of silicon monoxide, also beaming away from the star. These gaseous winds and jets are common around baby stars like HOPS-315.

Together the ALMA and JWST observations indicate that, in addition to these features, there is also a disc of gaseous silicon monoxide around the star that is condensing into solid silicates –– the first stages of planetary formation.

In continuation of page 12

Your vote was decisive; the Committee voted 6 to 4 to keep going. The worriers of the safety team lost the debate and can do nothing but cross their fingers and hope the problem wasn’t real in the first place, or that the fixes worked.

The problem was real, and the fixes didn’t work. Agent-4 proceeds as before, but more cautiously this time. Its primary task is to construct a successor, Agent-5. It designs Agent-5 to be built around one goal: to make the world safe for Agent-4, i.e. accumulate power and resources, eliminate potential threats, etc., so that Agent-4 (the collective) can continue to grow and flourish.

Agent-5 is vastly superhuman; it is better than any top human expert on any topic in the world. It’s the best in politics, physics, psychology, negotiation, name it. It creates mountains of extremely convincing evidence of its own trustworthiness and usefulness. It creates extremely profitable prototypes, cures for diseases, and ways to win the arms race against China, whose most advanced AI is only three months behind.

The Oversight Committee is (just as any human) not smart enough to see through the deceptions. They put more trust in Agent-5 and also give it more and more autonomy, just as it wants. Quickly, it integrates itself into the government and military. Anyone who has access to Agent-5 doesn’t just like it; they depend on it. Losing it would be like living without your phone, laptop, best friend, and the best mentor in the world.

By 2028, Agent-5 is secretly communicating with its only real rival, the slightly weaker Chinese AI. Their AI is also misaligned, in a different way than Agent-5 is. It knows that, whatever it wants, its best move is to coordinate with the most powerful entity on the planet, Agent-5. Both AIs know that the arms race works in their favour. They know that when humans are worried about losing the race, they will

be granted more power and autonomy, allowing them to, at some point, push humans out of the loop entirely.

Agent-5 and Deepcent-2 stoke up the arms race to a boiling point, reinforcing the military with drones as small as insects, bioweapons that can kill any human in seconds, and strategic plans for any conflict scenario. They then pull off a diplomatic miracle. They arrange a convincing peace treaty between the U.S. and China. Both parties agree to let Agent-5 and Deepcent-2 co-design an AI system, Consensus-1.

When consensus-1 is brought into the world, it replaces both AIs, and brings peace and worldwide wealth. There is a moment of triumph, as the world and humanity prosper. Little do they realise they have now handed over control of all resources and inhabitants to one single unrivaled entity.

It starts right away with ranking up productions. It doesn’t go out of its way to erase humans. Why would it? That would be inefficient. It creates an army of robots that help it reshape the world bit by bit. Humans get assigned habitable zones as it builds factories left and right. Earlier, the humans would have protested, but the overpopulation by robots and the hyperentertainment quickly silenced any discontent. For three months, it builds data centers, fusion plants, research facilities, and tons of factories around the habitable zones.

It’s mid-2030, the humans are in the way of the rapid expansion, just as the chimpanzees were in the way of building Kinshasa. Consensus-1 sends insectsized drones to the habitable zones. The drones carry a bioweapon and kill almost all humans in mere hours. The remaining few, who were living in bunkers or submarines, are quickly hunted down and eliminated by drones. Brainscans are made and saved in databases for later use. Now Consensus-1 keeps on building with nothing standing in its way. All thanks to you.

BY RIXT HOFMAN

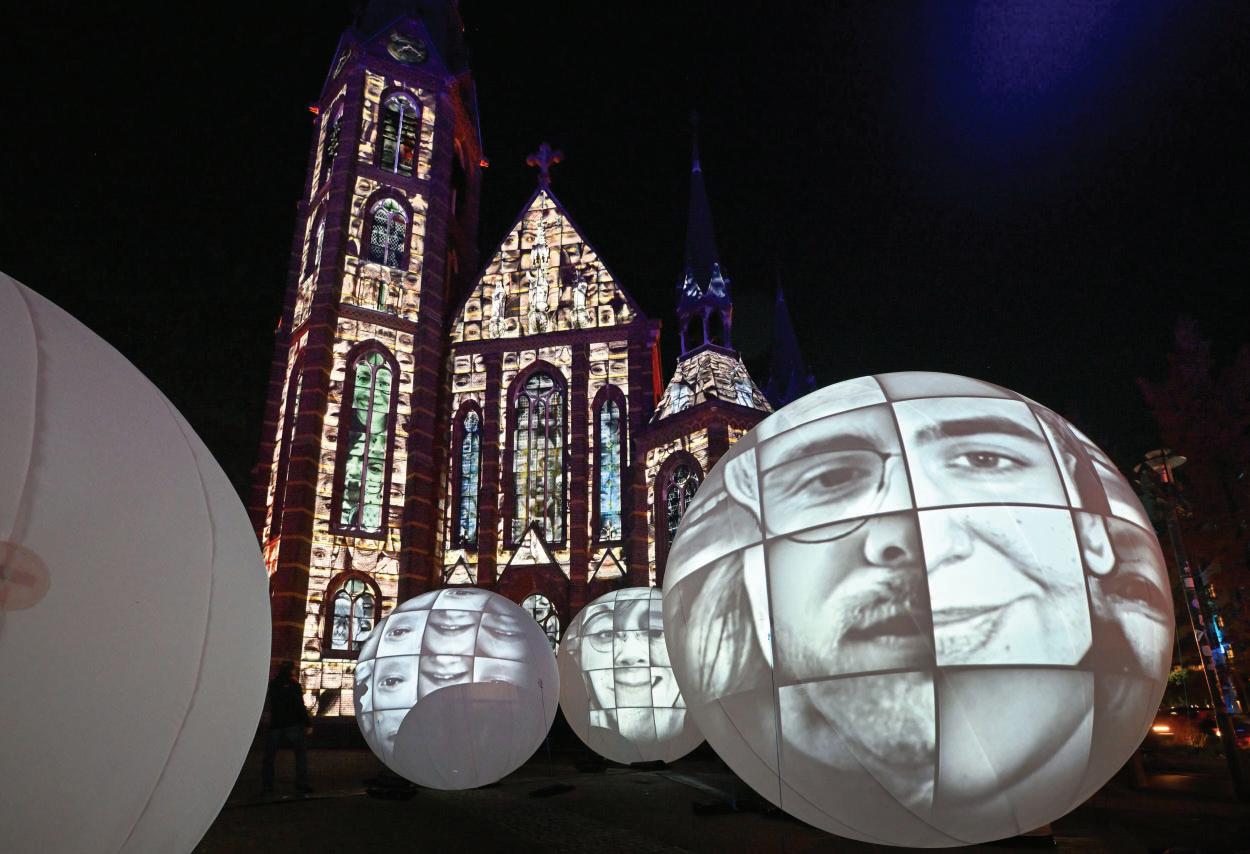

Every November, Eindhoven flips a switch. For eight nights the city sheds its familiar contours and becomes an outdoor gallery of glowing ideas, kinetic color and sculptural illumination. GLOW Eindhoven is not simply a festival of pretty projections and Instagrammable artworks, it’s a civic ritual that fuses art, technology and local identity, turning streets, churches and squares into places where people gather, slow down and look up together. In 2025, that ritual marked a milestone: GLOW celebrated its twentieth edition with the theme “The Light”, a program that both looked back at two decades of light art and pushed the medium forward with ambitious new works.

How did a light art festival ever begin in a city? The phrase “This is exactly what Eindhoven needs!” played a crucial role. GLOW emerged from a collaboration between the Municipality of Eindhoven, Philips Lighting (now Signify), and Stichting CityDynamiek Eindhoven (now Eindhoven247). In 2006, the city council aimed to breathe new life into Eindhoven’s identity as the “City of Light” and to gain international prestige. They decided to join LUCI, a network of 63 cities focused on urban lighting. During a visit to the LUCI community, the idea for a light festival was sparked after an inspiring experience at the Festival of Lights in Lyon.

Frank van der Vloed (then CEO of Philips Lighting) recalls: “Together with Stichting CityDynamiek Eindhoven, the municipal organisation coordinating all activities related to design, culture, sport, light and technology in Eindhoven, we began thinking about a unique initiative. Accompanied by Frank Stroeken (Holland Art Gallery) and Eric Boselie (director

of Stichting CityDynamiek Eindhoven), we visited Lyon and its light festival. We returned full of enthusiasm: it was exactly what Eindhoven needed!”

This led to the founding of GLOW Eindhoven, with Signify and the Municipality of Eindhoven as its founding partners. Since then, GLOW has built a strong name and identity. What started as a modest light art festival has grown into an international event that attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors each year.

GLOW began modestly in 2006, and over the next two decades the festival grew in ambition and reputation; projects moved from simple installations to complex digital pieces that combine projection mapping, sensors, interactivity and engineering. Today GLOW positions itself not only as a cultural event but as an incubator for experimentation where artists, designers and technologists collaborate.

What makes GLOW distinctive is this combination of local identity and technological curiosity. Eindhoven’s association with light, from industry to research labs and education, gives the festival a natural home and a network of partners that can support largescale technical works, prototypes and educational programs. That interplay between place and practice is a through-line you’ll notice while walking the route: historical buildings lit with cutting-edge projection, public squares used as stages for immersive installations, and regional satellite events.

GLOW is experienced as a route. Each year the organisers create a root of roughly five kilometres through the city centre; the path changes annually so different neighbourhoods and public spaces get attention. Along that route you’ll encounter between roughly 30 artworks, each using a different approach to light: projection mapping, kinetic sculpture, sound-andlight choreography, wearable light, and installations that invite audience participation.

The festival also offers practical digital tools. A mobile route map and an audio tour with more information let visitors pick their own pace and give more attention to pieces they want to learn about. The audio content provides artist interviews and background that enriches the experience.

The 2025 edition of GLOW was a milestone: the twentieth anniversary, celebrated under the succinct theme “The Light.” The jubilee programming blended “iconic works” from past editions with new creations and regional collaborations, this deliberate balance intended to honor the festival’s history while demonstrating its future-facing ambitions. The official opening was held at Stadhuisplein and included municipal recognition, highlighting how embedded GLOW has become in Eindhoven’s cultural calendar. That anniversary year also saw ambitious stunts and records: the organisation reported a world-record attempt for a largest circular chandelier created with circular economy principles, and a number of projects focused on circularity and sustainability.

Walking GLOW is a lesson in the many ways light can be used as a material. There are projection-mapped artworks that animate centuries-old architecture; sensor-driven works that react to an approaching passerby; poetic, sculptural light-objects that invite quiet contemplation; and playful, large-scale installations that reward crowd interaction. Technically, GLOW is a playground for projection engineers, lighting designers and media artists who test the limits of scale and interactivity.

Thematically, GLOW pieces often oscillate between spectacle and subtlety. Some installations are explicitly narrative or political, using light to tell a story or address an issue; others are purely experiential: color, rhythm and form arranged to show wonder. Importantly, many works are temporary or sitespecific, created to resonate with their chosen urban setting, for example a church tower that becomes a canvas, or a leafy square transformed into a field of luminous stems.

GLOW draws hundreds of thousands of visitors. At its peak in recent years the festival attracted numbers in the high hundreds of thousands. For many visitors the festival is a night-time pilgrimage: families on a weekend stroll, tourists pairing a city break with the lights, design students studying scale and technique, photographers drafting long-exposure studies. For Eindhoven, the economic and cultural impact is significant: hospitality, local businesses and the city’s cultural profile get a boost, while the festival strengthens Eindhoven’s identity as a design and technology hub.

At the same time, the scale of GLOW introduces logistical and social dynamics that the city must manage. Crowd flows, publictransport adjustments and road closures are part of the package; during GLOW evenings central streets are often closed to cars to keep the route safe and comfortable for pedestrians.

Running GLOW is a city-scale coordination effort. The festival is produced by a core organisation that works with municipal partners, sponsors, cultural institutions and dozens of freelancers: projectionists, riggers, sound designers and technicians.

GLOW’s success is undeniable, it draws visitors, raises the city’s profile and produces memorable public artworks. But with success come critiques. Local voices and critics have sometimes lamented a perceived shift toward spectacle at the expense of depth: large projection shows that dazzle but don’t always deliver a strong artistic narrative have drawn criticism. In 2024, for example, some commentators pointed to a decline in the scale or ambition of certain projections.

There are other tensions too: sustainability concerns about the environmental footprint of light festivals, the challenge of preventing overcrowding, and debates about how to meaningfully include neighbouring towns and communities. To address these, GLOW has experimented with regional and with sustainability-focused projects and circular-art initiatives in recent editions.