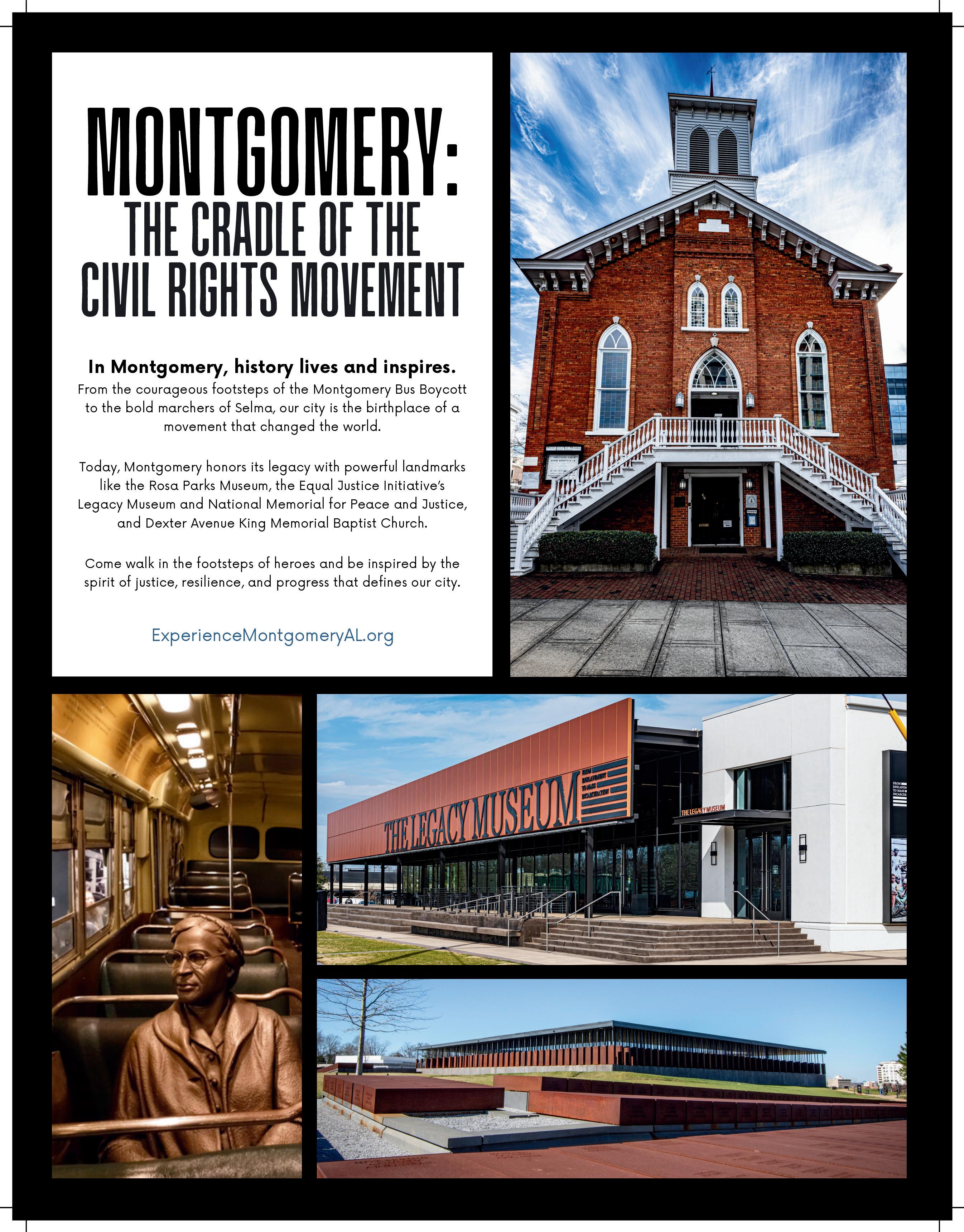

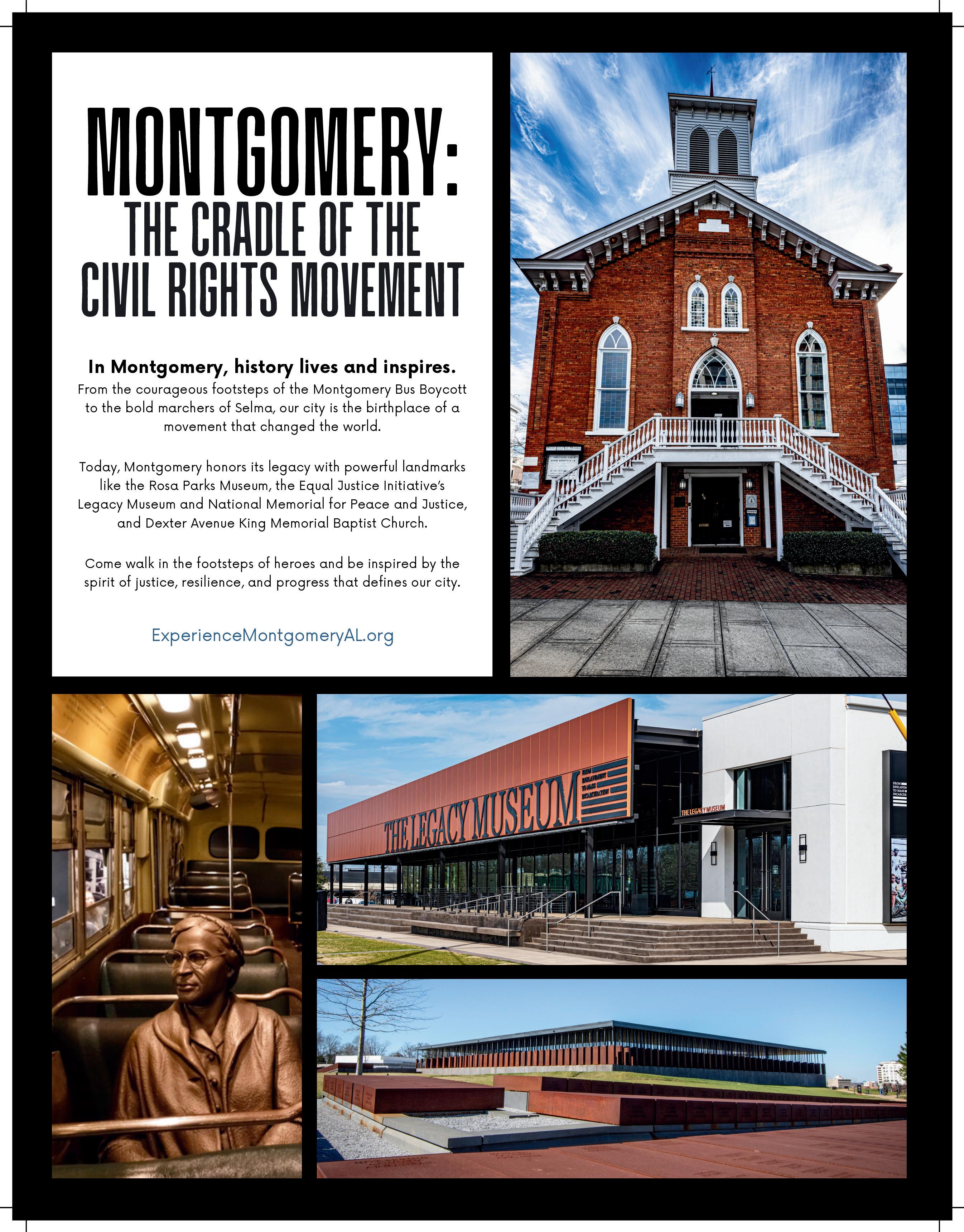

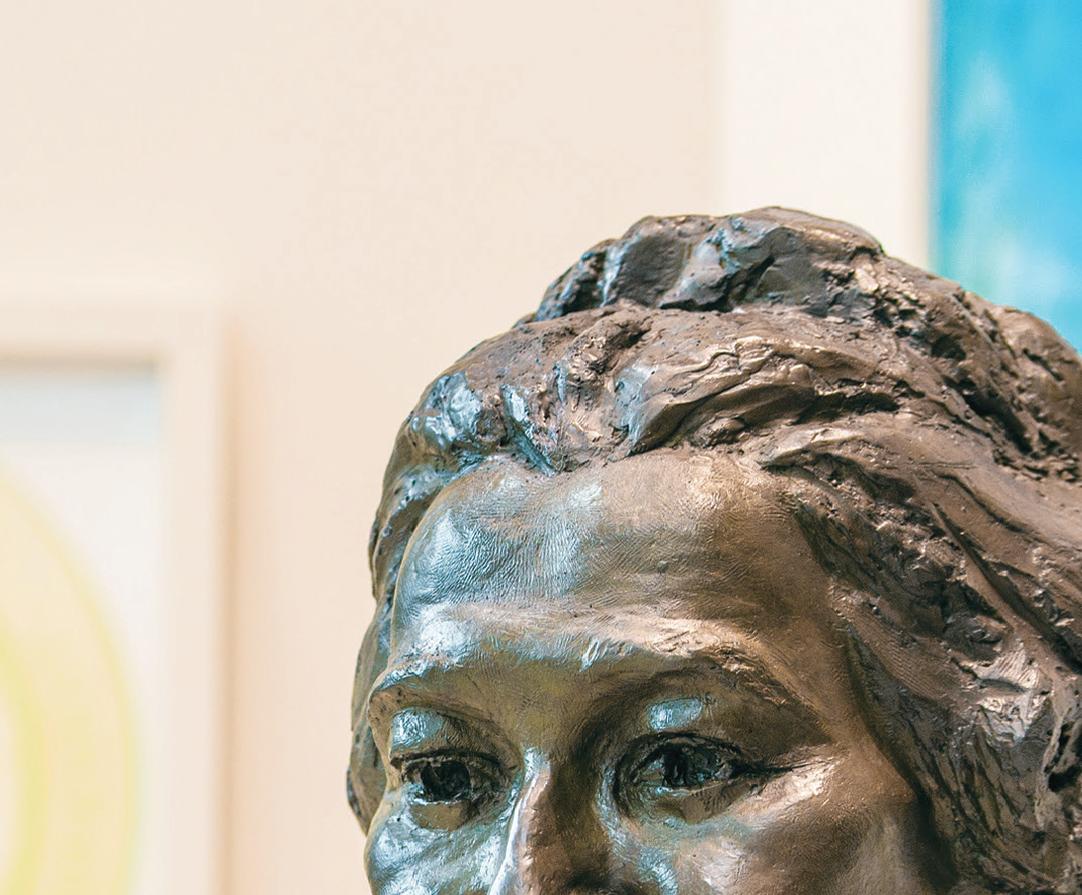

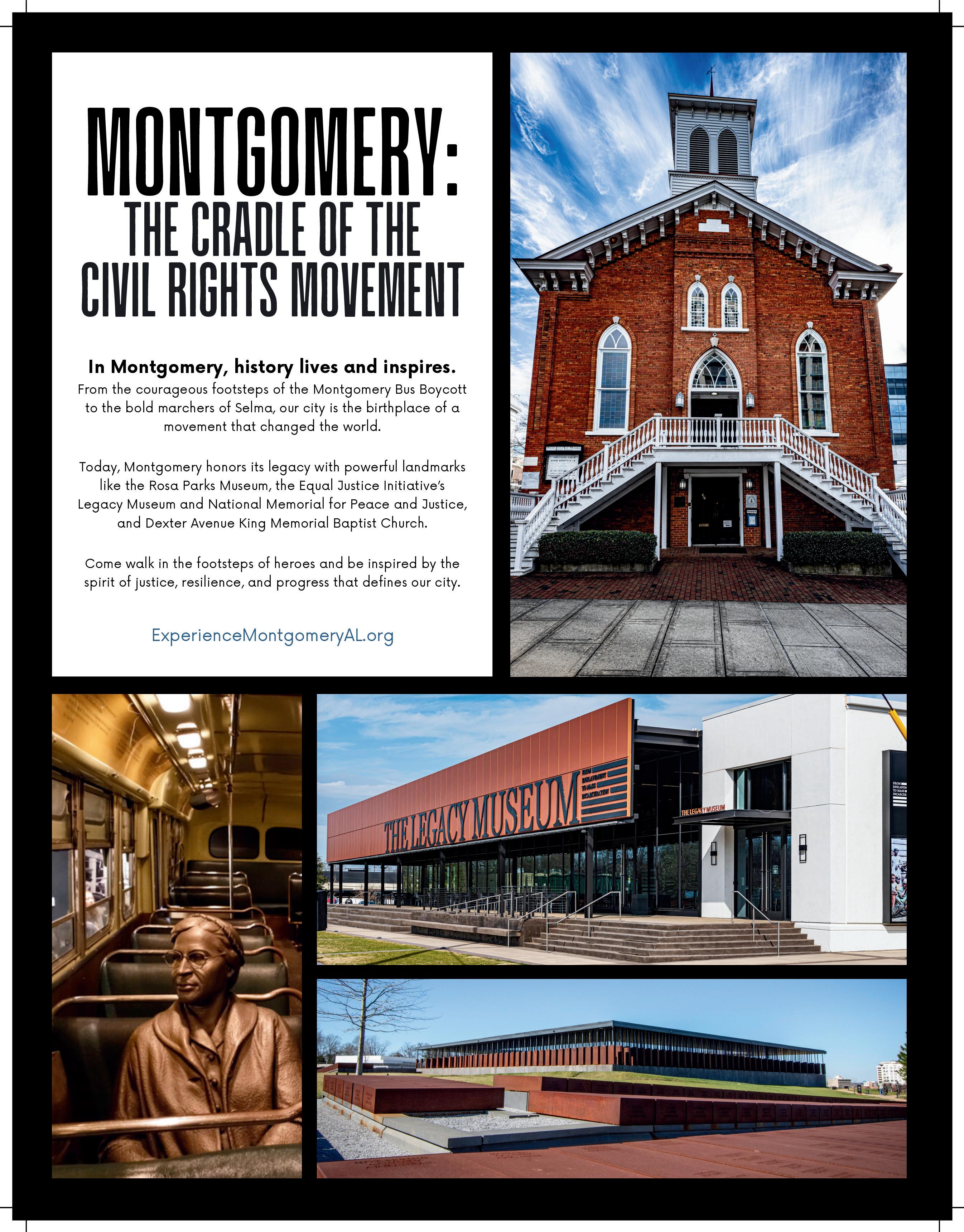

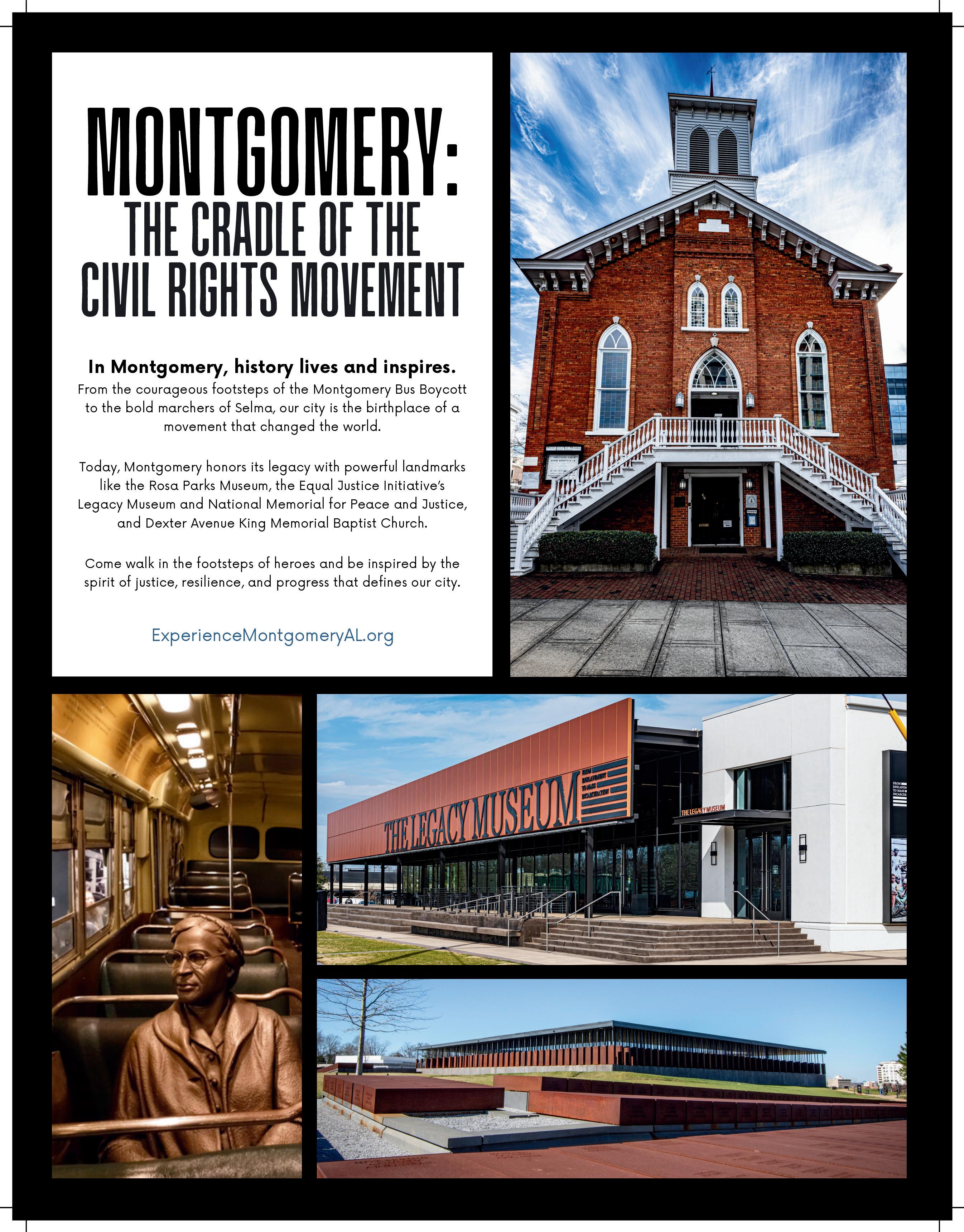

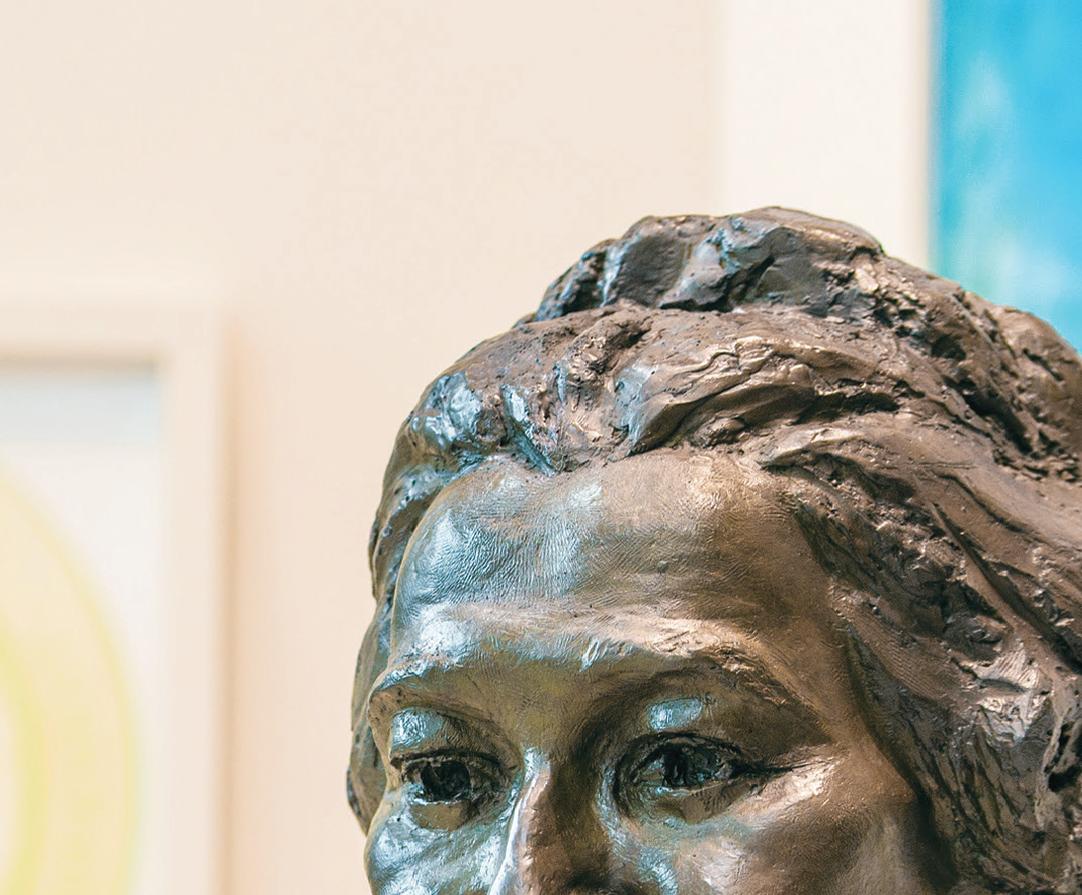

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks’ simple act of bravery helped inspire and lead the Civil Rights Movement. Today, visitors can step back in time and experience the sights and sounds that forever changed our country. Troy University’s Rosa Parks Museum honors one of America’s most beloved women who helped lead by her actions.

Plan your visit and learn all about the life and legacy of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

For ticket information and hours, visit troy. edu/rosaparks or call 334-241-8615

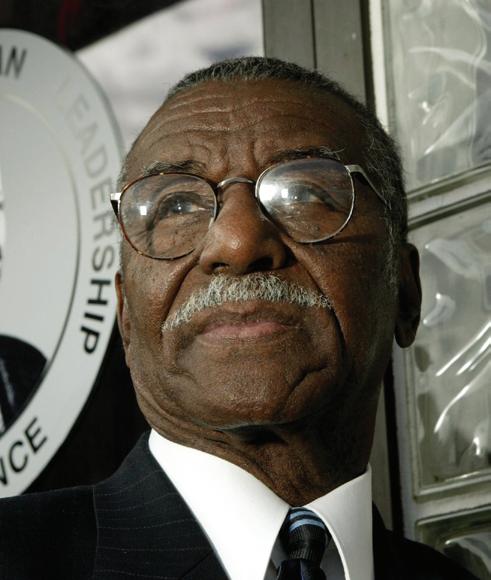

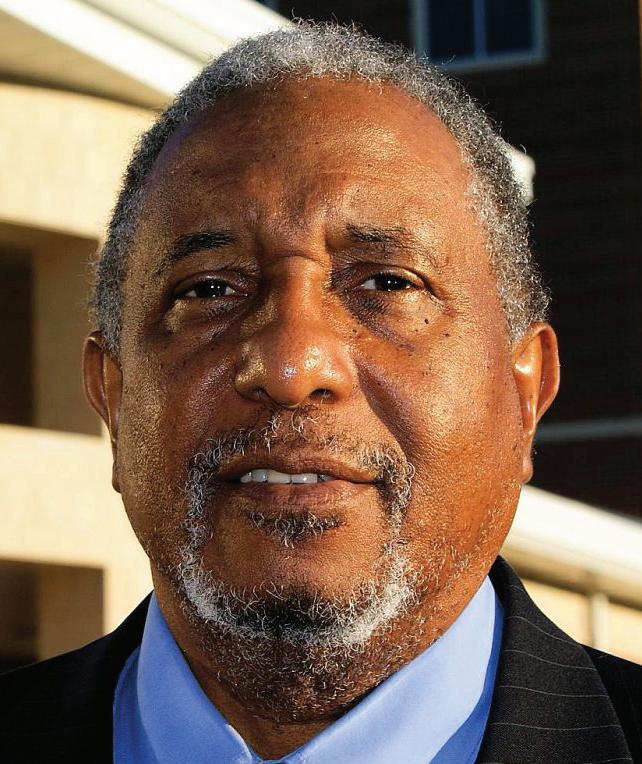

DeMark Liggins, Sr President & CEO

Martin Luther King Jr. Founding President

Ralph D. Abernathy President 1968 - 1977

Fred L. Shuttlesworth President 2004

Dr. Bernard LaFayette, Jr Chairman

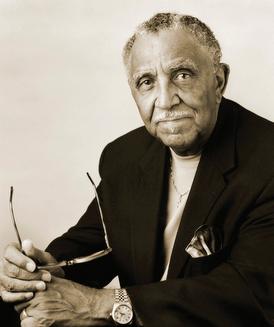

Joseph E. Lowery President 1977 - 1997

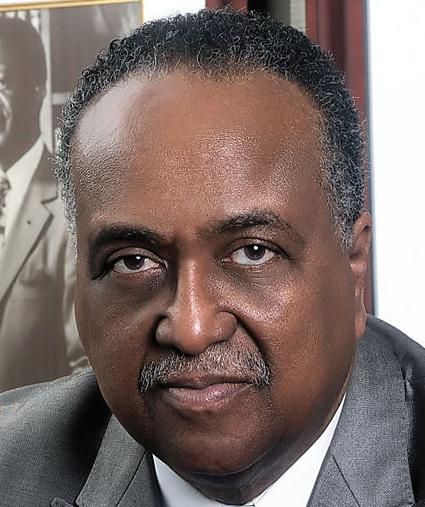

Dr. Charles Steele, Jr. President Emeritus

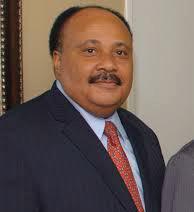

Martin Luther King III President 1998 - 2003

Howard Creecy Jr. President 2011

Kaiser Permanente is committed to health care for all. That starts in our communities — with care teams that reflect and respect the members we serve.

In pursuit of our mission and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of equality, we take bold, community-led action to address the biggest factors that shape people’s health. We partner with organizations that share this vision, so we can all come together to foster healthier, more vibrant communities.

kp.org/equity

By: DeMark Liggins, SCLC National President & CEO

Every January, Dr. King and his legacy returns to the center of the national conversations, and no matter how many times this country circles back, it still settles into that familiar rhythm where his face shows up on social media and TV, his quotes start moving around again like they have a life of their own, and from classrooms to pulpits to boardrooms his life becomes the reference point people reach for when they want to describe what courage looks like, what conviction looks like, what sacrifice looks like. Much of what Dr. King did, much of what he carried, and much of what he endured, he did while serving as President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and as the current President we hold his holiday with gratitude and even affection, but we also carry a very real awareness that this role is not ceremonial, it is weight, it is stewardship, and it is a responsibility to be honest about what we are living through and what we are called to do next.

And here is the truth that does not always make it into the polished tributes: remembering him is easier than living what he taught. It is easier to repeat a quote than to practice the mindset behind it. It is easier to celebrate the movement than to commit ourselves to the kind of work that makes a movement necessary. The country right now feels louder than it feels honest, we are connected to each other in ways that would have sounded like science fiction a generation ago and yet we are far from united, and even though we have information everywhere, all the time, it often feels like we are losing the ability to apply wisdom to what we know. Politics has become a daily stressor for families, the economy has people anxious from the unemployed to the under employed to the person with a decent job who still does not feel secure, and even when someone is not following the news closely, tension leaks into everything anyway, into how we talk to each other, into how we raise our children, into what we believe is possible.

So in that kind of moment, Dr. King cannot just be a historic figure we honor, he becomes a mirror and a measuring stick, because his life forces the kind of question that is uncomfortable but necessary, which is what leadership looks like when the moment is complicated, when pressure is constant, when the temptation to be reactive is always there, and when the consequences are real for real people, not just for headlines. His teachings keep insisting on moral clarity, and moral clarity is not the same thing as a clever

talking point or a trending opinion, it is the willingness to tell the truth about what is right, what is wrong, and what is required, even when that truth costs something.

When Dr. King was leading, injustice was often visible and direct, signs were posted, laws were clear, cruelty was public, and if you were paying attention you could see exactly what was happening and who was being harmed. In our era, injustice can be harder to name because it often comes through systems, policies, and decisions that are described as neutral, and that is where people get confused, because when the language sounds neutral it can make the impact feel invisible, but invisible does not mean harmless. Sometimes inequity hides behind technical words, sometimes it hides behind claims of efficiency, sometimes it hides behind security, sometimes it hides behind arguments about fairness that ignore the fact that so many people have historically been denied a fair chance to compete in the first place, so moral clarity today requires discernment, and discernment requires the willingness to look beneath the surface and still tell the truth about what a policy produces, not just what it claims.

That is why exhaustion makes sense for a lot of families, because political division has become normalized to a point where it is not only policy disagreements, it is hostility, it is suspicion, it is a refusal to share facts, and it is the idea that if the other side says it, it must be wrong, even if it is true. Outrage has become an industry, humiliation has become entertainment, and too many communities are tired of feeling like they are living inside an argument that never ends, especially when the argument rarely produces solutions and mostly produces more heat. In that environment, leadership cannot live on the daily chaos cycle, it cannot be pulled into whatever is trending, because trends move fast and values are supposed to last, and Dr. King’s life keeps reminding us that leadership anchored in principle can outlast seasons of confusion.

The economic pressure people are feeling is also real, and it deserves to be said plainly because there is a quiet way our society dismisses struggle unless it looks a certain way. Under employment is real. Wage pressure is real. The cost of living is real. The feeling that the economy is happening to you rather than working for you is real. There are people with degrees who still feel stuck, there are people working full time who still feel behind, there are families one emergency away from being thrown off course, and when you combine that with rising stress and rising distrust, the anxiety is not just political, it is personal, because the ground under people’s feet feels less stable than it should.

Dr. King understood that civil rights is not only about access, it is about dignity, it is about opportunity, it is about whether a society that calls itself great will create conditions where families

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

can build stability and children can imagine a future without constant fear. That is why, as his leadership matured, he spoke more directly about poverty and economics, because he knew that if people cannot live, they cannot thrive, and if people cannot thrive, democracy becomes fragile. The Beloved Community is not a poetic idea, it is a practical standard, it is the belief that a nation can have prosperity without treating poverty like a permanent feature of the landscape, and it is the belief that people should not have to be perfect just to have a fair shot.

Then there is the digital reality, which is changing everything at once, because we are more connected than ever but connection does not equal community, we have more information than ever but information does not equal wisdom, and the speed of technology has outpaced the speed of our ethics. Misinformation spreads quickly, manipulation is easier than it has ever been, data is collected and sold in ways most people do not fully understand, young people are being shaped by platforms that do not share our values, and adults are being pulled into online cultures that reward outrage and punish nuance. Dr. King dealt with distortion in his day, but what used to move by newspaper and rumor now moves by algorithm, and the algorithm does not care what is true, it cares what keeps people engaged, which is why discernment is not optional anymore, it is a basic leadership skill in modern America.

And behind all of this is the strain many people feel about democracy itself, because trust is fragile, participation can feel pointless, and some communities feel seen only when it is time to vote and ignored the rest of the time. That frustration is understandable, especially for people who have worked hard, voted faithfully, and still watched inequity persist, but the model Dr. King left was not withdrawal, it was organized engagement, because cynicism is not a strategy and the public square will not stay healthy if moral people abandon it. Democracy is not self sustaining. It requires participation, education, advocacy, and organized pressure, and that is why the Beloved Community is not just a dream, it is a strategic direction. It is that direction and that model that pushes us everyday at SCLC. During this King holiday, we refuse to remember his legacy without remembering his leadership and his love and we appreciate all of you who stand with us as we continue his work!

Written By: Dr. Bernard Lafayette , Chairman of the Board

I have been introduced to a wonderful new book that is bringing back many memories and giving me new ideas for the future. It is “Spell Freedom: The Underground Schools that Built the Civil Rights Movement” by Elaine Weiss. The narrative captures the citizenship school project (CEP), founded by four “disruptors” in the summer of 1954, that became famous at “Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee.

Myles Horton started Highlander in 1932. His story is well documented, and I suggest everyone learn about it. “He helped miners and lumbermen, farmers and steel workers organize, cooperatize and unionize. They got involved in all New Deal programs that could help them and became an official education facility for the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Highlander rejected segregation, for which Horton was despised.” Horton enjoyed calling himself a “Radical Hillbilly from Tennessee

The other three founders of the CEP were from South Carolina. Septima Clark, a teacher, Esau Jenkins, a businessman from Sea Island, and Bernice Robinson, a beautician from Charleston.

• Mrs. Clark was a 56 year old widow, mother, veteran teacher and community activist when she got word of the unanimous decision in Brown v Board of Education case. She was thrilled!

• Esau Jenkins, 44 years old, was elated to learn of the Court’s decision, but knew nothing would change unless the white men in charge of schools were pushed—by having to answer to Black voters. They needed To vote!

• Bernice Robinson was living in Charleston to care for her elderly parents. She was owner of Glamour Beauty Box salon and chair of membership for the local NAACP.

The last week of June, 1954, Mrs. Clark made her way to Monteagle and Highlander to meet with folks from various walks of life and different areas of the United States for life-changing experiences.

The author describes an incident from the Fall of 1958, when Rev. James Lawson was conducting

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

seminars to train Nashville college students in the “….. difficult mental and physical techniques of meeting violence with love.” Lawson arranged a weekend visit to Highlander to give his students “….an intense dose of Highlander-style intellectual debate and integrated living.”

I had the good fortune to be included on the trip, along with John Lewis and James Bevel. John spoke for me as well as himself when he said he was most impressed by Septima Clark. “What I loved about Clark was her down-to-earth, no-nonsense approach,” Lewis remembered. “And the fact that the people she aimed at were the same ones Gandhi went after, the same ones I identified with, having grown up poor and barefoot and black.”

Mrs. Clark reinforced our belief that the “movement was going to be powered by the tens of thousands of faceless, nameless, anonymous men, women and children,” like us, who were going to “rise like an irresistible army as this movement for civil rights took shape.” Needless to say, we left Highlander on fire!

Meanwhile, the book gives a description of the very small things that make up a movement. The adult schools were replicated across the South—known as the “Citizenship Education Project” (CEP). The CEP schools wanted to learn more than how to vote, but leaders at Highlander, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), (which took over the schools when they became too numerous for Highlander to coordinate or fund) saw them as “an efficient way to register voters.” And, Dr. King called Septima Clark “Mother of the Movement.”

Highlander was fighting one costly crisis after another, so Guy Carawan, Music Director, organized a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall in New York City to raise funds. The headliner was Pete Seeger and the MC was Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth from Birmingham. Again, I was included on the program.

My fellow SNCC leader James Bevel and myself, along with two of our schoolmates from American Baptist Theological Seminary, Joe Carter and Samuel Collier, performed as the Nashville Quartet. Another group from the South was the Montgomery Gospel Trio, composed of teenagers Jamila Jones, Minnie Harris, and Najume Mulefu, who were wearing elegant evening gowns. We sang together and as separate acts and were received well by the audience.

“We Shall Overcome” had become the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement by that time, and made its debut at Carnegie Hall that night. Guy Carawan and Pete Seeger lead the audience on guitar and banjo, respectively.

The three teachers, Clark, Jenkins and Robinson, spread out across the South to prepare Black citizens for registering to vote. Mrs. Clark recruited for the cause by sitting in church pews, diner stools, beauty shops, barber shops, listening to what people were talking about and desperate to change.

“I teach them to teach others how to use the rights and privileges the boycotters, picketers, and sitinners have obtained for them, Clark explained. “The Community has to be brought up to the level of the action of the students. We have to plan strategy moves and actually take them by the hands. They must use the lunch counters, station facilities, etc. They must learn to not give their seat to a white person on the bus.”

Mrs. Clark was the recipient of many awards and honors, including the “Living Legacy Award” from President Jimmy Carter. Highlander is now in its 93rd year of operation, but re-located in New Market, TN. Their newest

building is the “Septima P. Clark Education Center.

On March 6, 2025, “The Atlantic” published an article written by author Elaine Weiss called “Why the Trump Administration Canceled Me.” She had been scheduled to speak about her new book, “Spell Freedom” at the Carter Library but was informed by her publisher that the event had been cancelled.

According to the Trump administration, public programs, including book talks, serve an educational function, which is why it makes sense that they are under attack. A presidential executive order threatens to withhold federal funding from those K-12 schools that teach that the U.S. is “fundamentally racist, sexist or otherwise discriminatory. That cuts out a lot of history.”

Author Weiss closes the article with the following statement. “I think Clark would have some sharp words for the current administration, with its callous attempts to bend language, art, science, and history to its liking. I believe unconditionally in the ability of people to respond when they are told the truth. We need to be taught to study rather than believe, to inquire rather than to affirm.

This may not fit the current government’s definition of patriotism, but to me, it’s the right spirit in which to honor the history and guard the future of the United States. It’s the kind of patriotism we need right now.

Note: This is Part I of my review of “Spell Freedom” and will be continued.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

This November, we won a major victory when a federal court blocked an effort by the Trump administration to force the early release of sealed FBI surveillance records tied to Dr Martin Luther King Jr and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The court’s order stopped an executive push that would have overridden a binding judicial agreement and decades of settled law. That ruling matters because it confirms that history created through government abuse cannot be rushed into public view for political purposes, and that organizations targeted by that abuse still have standing to defend the terms under which the record is revealed. We did not come to this case as spectators. We came as plaintiffs, as witnesses, and as custodians of a history that the federal government once tried to undermine and has now tried to rush into public view on its own terms. The federal court’s decision to keep sealed the FBI surveillance files on Dr Martin Luther King Jr until 2027 is not simply a procedural ruling. It is a confirmation that the law still protects agreements forged in the aftermath of government abuse, and that executive power does not override judicial obligation.

The order was issued by the United States District Court for the District of Columbia and denied the federal government’s request to lift a seal that has been in place for nearly fifty years. The files document surveillance carried out by the Federal Bureau of Investigation against Dr King, Bernard S Lee, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference during the most consequential years of the civil rights movement. Under a court approved agreement reached in the nineteen seventies, the materials were transferred to the National Archives and sealed until January 31, 2027.

That agreement was not symbolic. It was the product of litigation that exposed how the federal government used its intelligence apparatus to monitor and attempt to discredit civil rights leaders. From the early nineteen sixties through the late nineteen sixties, phones were tapped, private lives were scrutinized, and personal information was collected without consent. These were not isolated actions. They were part of a coordinated effort to weaken a movement by targeting its leaders.

The cases Bernard S Lee v Clarence M Kelley and Southern Christian Leadership Conference v Clarence M Kelley forced that conduct into the open. Faced with the prospect of destroying the records or preserving them under strict judicial supervision, the parties agreed to preservation with a fixed seal. The court approved the terms. The timeline was explicit. The obligation was clear. The agreement was designed to protect both the historical record and the dignity of those who were surveilled.

The Trump administration sought to undo that clarity through an executive directive calling for accelerated review and release of records related to the era of Dr King. The justification offered was transparency. What was ignored was context, consent, and the binding force of a judicial order.

From our position inside this case, the attempt was not neutral. It was an assertion of executive convenience over constitutional process. The court rejected it.

In its memorandum order, the court reaffirmed that the seal remains in full effect and that the government failed to present a lawful basis for lifting it early. Executive preference did not outweigh a court approved agreement. Political urgency did not erase decades of settled law. The ruling was measured and precise, grounded in the principle that judicial orders do not expire at the request of the executive branch.

The court acknowledged that there is legitimate public interest in understanding the civil rights era and the events surrounding Dr King’s life and death. But it also emphasized its responsibility to respect the privacy and dignity of those who were targeted by government surveillance. The court gave weight to the objections of Dr King’s family, who have consistently asked that these particular records remain sealed until the date that was promised. Their position reflects lived experience. During Dr King’s lifetime, selective disclosures and distorted narratives were used to try to discredit him and divert attention from the substance of his work.

As an organization that stood alongside Dr King and Bernard Lee, SCLC approaches this issue with clarity. We were present at the genesis of making history. We remain present in defending it. This ruling recognizes that continuity. It affirms that plaintiffs do not disappear with time, and that institutions built to advance justice retain standing to protect the integrity of the record.

The court also addressed the practical reality of timing. With just over a year remaining before the scheduled unsealing in 2027, it encouraged the parties and the government to use this period to develop a responsible plan for release. That plan should reduce unnecessary harm while still allowing historians, journalists, and the public to study the record with accuracy. How these files are released will shape how they are understood.

From inside this process, that guidance is essential. Surveillance files are not neutral artifacts. They reflect the biases and objectives of the agencies that created them. Without context, fragments can be misused. Without care, old smears can be revived. We will not allow the same tools that were once used to undermine Dr King, Bernard Lee, and SCLC to be recycled under the banner of openness.

This decision also carries broader implications. It reinforces that courts remain a meaningful check on executive overreach, even when that overreach is framed as reform. It underscores that civil rights organizations are not relics of the past but active participants in safeguarding constitutional protections. And it sends a clear message that history shaped by state power must be handled with discipline, not speed.

SCLC views this ruling as an affirmation that the struggle for justice includes not only the right to know history, but the right for families and organizations to be treated fairly as that history is examined. The legacy of Dr Martin Luther King Jr and the movement he helped lead belongs to the nation. That history has been celebrated, contested, and at times distorted. This case and this decision make clear that it will not be handled carelessly, and that SCLC will not sit by idly while distortion is allowed to take hold.

We believe in equal opportunity for all regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, or ethnic background.

Associated Grocers

Cooperative Energy

Farmers Home Furniture

Harley Ellis Devereaux

The closer we get to the 2026 midterm elections, the more it can feel like the nation is speaking in raised voices. In seasons like this, some people step back from public life because it feels exhausting, or because it feels unworthy of their trust. Yet the healthiest moments in American democracy have never come from retreat. They come when ordinary people decide that the future is still worth their attention, their time, and their presence. Civic engagement is not simply a responsibility. It is a practice of hope. It is the decision to remain involved, even when the moment tries to convince you that involvement does not matter.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was founded on the belief that moral people of conscience can shape public life. From the beginning, our work has insisted that democracy is more than a ballot box. It is also the dignity of the voter, the fairness of the rules, the truthfulness of the story we tell about each other, and the willingness of communities to show up for one another even when it is difficult. That legacy is meant to move, not to sit still.

In every generation, the question returns in a new form: who gets to belong, and who gets to decide? The Civil Rights Movement answered that question through courage, discipline, faith, and organization. SCLC stood at the forefront of that work, helping coordinate community action and develop leaders who could sustain it. From the March on Washington to the Birmingham Movement, from Bloody Sunday to the Selma Movement, communities organized with SCLC to demand full citizenship and a nation that would honor its promises. That story is not only about the past. It is a reminder that progress is never automatic. It requires people who are willing to participate.

Today, democracy is tested in different ways. Voting rules are debated from statehouse to courthouse. Misinformation travels faster than truth. Economic pressure leaves many families tired and skeptical. Young people ask whether the system is built for them or against them. At the same time, we also see local leaders rebuilding trust block by block, neighbors finding ways to serve each other again, and communities that still believe a better future is possible. The 2026 midterms will be shaped not only by campaign messages, but by turnout, trust, and local leadership.

Midterms are not a pause between presidential elections. They are often the place where the rules of the road are set. They shape who writes state laws, how schools are governed, how public funds are allocated, and how access to the ballot is protected. They shape who oversees elections, how districts are drawn, and how communities experience public safety, health, and opportunity. These elections reach into everyday life long after the campaign signs disappear.

Participation is personal, too. It is about the grandmother who needs affordable medicine, the parent who wants a safe and excellent school, the worker who wants fair wages, the returning citizen who wants a true second chance, and the young person who wants to believe that hard work still leads to opportunity. Policies are not abstract. They land in real neighborhoods, on real kitchen tables, and in real lives. When citizens participate, they help decide whether the American Dream becomes more reachable, or more distant, for the people around them.

SCLC approaches civic engagement with a clear posture: we are nonpartisan and people centered. We are not here to serve a party. We are here to serve communities. We do not ask people to surrender their values to a campaign season. We ask people to bring their values into public life with clarity and consistency. Nonviolence teaches discipline. Faith teaches humility. History teaches patience. Those lessons guide the way we show up. We can disagree without turning neighbors into enemies. We can insist on truth without losing compassion. We can advocate strongly while remaining grounded in respect.

In that way, civic engagement becomes a form of love in action. It is how we make care for our communities measurable, not only emotional. It is how we protect rights, strengthen institutions, and open doors for those who have been pushed to the margins.

Participation rarely looks dramatic. Often it looks like a steady set of choices. It looks like checking registration early, then reminding a friend to do the same. It looks like learning what is on the ballot, including local offices that shape daily life. It looks like asking good questions at a community forum, and refusing to share information that has not been verified. It looks like helping an elder navigate voting options, or making sure a neighbor has a ride. It also looks like protection. When communities understand their rights and their options, intimidation loses its power and democracy becomes safer for everyone.

Civic life also includes the way we treat one another while we participate. It is possible to take the issues seriously without treating neighbors as enemies. In many communities, people share the same concerns: stable housing, safe schools, decent jobs, and a justice system that is fair, even when they disagree about the best path forward. SCLC calls our chapters and our members to model a better tone: listen with patience, speak with honesty, and refuse to let fear set the agenda. When we slow down enough to hear each other, we make room for truth, for practical solutions, and for a democracy that feels worthy of the people it serves.

As we look toward 2026, SCLC is not relying on one voice. We are building a chorus. President and CEO DeMark Liggins, Sr. has called the organization to lead with Legacy, Leadership, and Love. That framework matters because it keeps us rooted and forward looking at the same time. Legacy reminds us that we inherit a sacred responsibility and a proven set of tools. Leadership reminds us that we must develop new leaders, not only celebrate historic ones. Love reminds us that compassion must become programming, presence, and service that can be felt in communities.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

But SCLC is not a one person mission. In 2026, our chapter Presidents will be essential. They live close to the needs of their communities, and they translate national vision into local action through voter education, outreach, and community presence. Our National Board members provide governance, strategy, and accountability, helping ensure that civic engagement work stays aligned with our mission and that partnerships reflect our values. Our members remain the heartbeat. The movement has always been powered by ordinary people doing extraordinary work, and civic life grows stronger when members decide that participation is not optional, it is part of who we are.

In the coming year, SCLC will continue to strengthen voter empowerment through practical engagement, including work like SCLC Votes. That means meeting communities where they are, partnering with trusted institutions, and promoting accurate information and respectful dialogue. It also means follow through. Civic engagement is not only about Election Day. It is also about what happens after: holding leaders accountable, attending meetings, tracking the decisions that shape opportunity, and staying involved when it would be easier to disengage. Democracy is a living practice. It becomes healthier when communities stay present.

The American Dream has never been perfect, and for many it has felt distant. Housing costs are high. Health care feels uncertain. Wages do not always keep pace with prices. Young people wonder if stability is out of reach. These concerns deserve honesty. But the answer cannot be withdrawal. When the Dream feels threatened, the response must be deeper engagement, not less. The Dream is not a private possession. It is a public project, built through choices that citizens can influence when they participate.

As 2026 approaches, SCLC is calling for a renewed commitment to civic life. Not because politics is perfect, but because people matter. Not because participation is easy, but because it is necessary. If you have felt discouraged, start small. Check your registration. Learn what is on your ballot. Support your local SCLC chapter and its President. Encourage a young person. Correct misinformation with calm truth. Then take one more step and invite someone else to take that step with you.

This is how democracy is repaired and renewed, one consistent act at a time. The American Dream is still worth working for. And in 2026, that work will look like people showing up together with faith, discipline, and hope.

The name alone makes it easy to dismiss.

The so-called “Big Beautiful Bill” arrived wrapped in slogans, political branding, and wall-to-wall commentary that has left many Americans either defensive or exhausted. For some readers, the politics behind the bill are reason enough to tune it out entirely. For others, support or opposition has hardened into identity. Both reactions are understandable. Neither is especially useful.

Whatever one thinks of how this legislation was framed or passed, it is now law. And like many large federal bills, it contains provisions that will shape everyday financial outcomes whether people engage with it or not. Some of those provisions will quietly benefit households that never supported the bill’s authors. Others will go unused by the people who need them most.

This article is not an endorsement. It is a practical guide. It is written precisely because the politics surrounding this law make it easy to overlook parts of it that should be used by every American, regardless of where they fall politically. There is also an uncomfortable reality worth stating plainly. To some degree, those who pushed this bill are counting on people who disagree with the politics to disengage. They are counting on skepticism to turn into silence, and silence to turn into nonparticipation. That is how complex laws quietly widen gaps between those who benefit and those who do not.

As Americans, regardless of how we feel about this law, it matters that we understand and use every opportunity a law provides. Not participating does not register as protest. It registers as absence. At its core, the “Big Beautiful Bill” is a wide-ranging federal package combining tax changes, spending programs, and regulatory adjustments. Like many omnibus laws passed by the United States Congress, it bundles together priorities that would never pass on their own. It is best understood not as a single idea, but as a collection of tools. Some are blunt. Some are precise. Some will work better for people with time, stability, and professional help. Others are accessible with basic information and follow-through. The challenge is that none of these tools come with clear instructions in the mail.

For years, many households stopped itemizing deductions because the standard deduction was large enough to make itemizing feel pointless. This bill changes that calculation for a significant number of families.

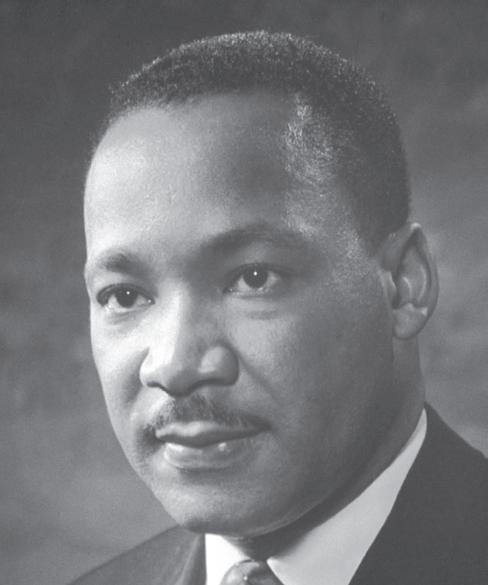

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words remind us that the time to do what is right is always present, especially when faced with uncertainty. In times when our values are tested, it is our responsibility to take action and lead with justice and fairness.

1990_SD1_1B

Several deductions that were previously capped, reduced, or unavailable are now expanded or restored. These include certain unreimbursed work expenses, education and certification costs, caregiving expenses for elderly or disabled family members, and higher limits on charitable contributions. The practical takeaway is not that everyone should itemize. It is that families who assumed itemizing was “not for people like us” may want to run the numbers again.

This matters most for households managing layered responsibilities: parents who are also caregivers, workers paying out of pocket for tools or transportation, adults investing in training to remain employable. Like many

federal laws, this one tends to advantage those with the time and resources to document expenses carefully. Receipts, mileage logs, and proof of payment now carry more weight than they did before. If recordkeeping has never been a habit, starting now matters more than reconstructing later. One of the least publicized provisions in the bill involves expanded children’s savings accounts.

These accounts are designed to help families save for education, training, and early adult expenses. Unlike older plans that focused almost exclusively on four-year college pathways, the new structure allows broader uses, including vocational training and credential programs.

Some children qualify automatically. Others may receive small seed contributions if household income falls within certain thresholds. Growth is tax-advantaged when funds are used for approved purposes. What often keeps families from engaging with these accounts is not disinterest, but pressure. Many households are focused on immediate needs. Long-term savings can feel unrealistic. Still, time matters. Even modest contributions made early can grow meaningfully over years. Families who are able to open accounts and contribute occasionally may be positioning children for options that did not exist before. Community organizations, schools, and faith groups can play a critical role here by helping parents understand eligibility and deadlines before they quietly pass.

This bill includes several tax credits tied to employment and earned income. These credits can be valuable, especially for households with children. It is important to describe them carefully. These are not rewards for effort. They are credits tied to employment status, available to those who have been able to secure work in a difficult and uneven job market. Many people who want to participate remain excluded because of regional job scarcity, discrimination, disability, caregiving responsibilities, or economic downturns. Some of these credits are refundable, meaning families may receive money even if they owe little or no tax. Others reduce tax liability directly. Eligibility

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

rules are strict. Income thresholds, filing status, and documentation determine access. Many families miss out not because they are ineligible, but because they assume they are.

Free or low-cost tax preparation services, often available through libraries and nonprofits, can make the difference between receiving a credit and leaving it unclaimed.

The bill also expands what qualifies as a health or education expense under tax-advantaged accounts. For families managing chronic illness, mental health needs, or learning differences, this can reduce the real cost of care. More services now qualify for pre-tax spending than in previous years. Education expenses are also treated more flexibly. Certification programs, technical training, and nontraditional learning paths are recognized more often. This reflects the reality of today’s job market, even if the politics surrounding the bill do not always acknowledge it. Families may benefit from reviewing benefit account rules carefully this year. Long-held assumptions about what “counts” may no longer apply. This law does not benefit people equally. But it does create opportunities for those who are able to engage with its requirements.

Practical steps include:

• Revisiting tax strategy earlier in the year, where possible

• Tracking expenses consistently, even with simple tools

• Opening or confirming children’s savings accounts

• Asking employers, where access exists, how benefits or deductions may have changed

• Using community-based financial counseling and tax assistance

• These steps are not about political agreement. They are about minimizing loss in a system that already favors those with information.

Using the provisions of this law does not signal approval of how it was named, framed, or passed. It signals responsibility.

History shows that when people disengage from complex systems out of protest or exhaustion, the systems do not change. They simply serve a narrower group. Nonparticipation rarely affects the structure itself, but it does affect household outcomes.

The “Big Beautiful Bill” may remain controversial. It may deserve criticism. But it is already shaping financial realities in quiet ways.

Tax deductibility beyond the standard deduction. Children’s savings accounts that grow over time. Credits tied to employment for those fortunate enough to find work in a challenging economy.

These tools belong to the public, even when access to them is uneven.

Ignoring them does not make a statement. Using them is one way communities protect themselves from being left further behind.

A policy shift does not need to be loud to be consequential. Sometimes it arrives quietly, framed as a technical adjustment, its implications revealed only later through budget shortfalls, enrollment drops, and diminished opportunity. That is the moment now taking shape as the U.S. Department of Education moves toward reclassifying certain academic and workforce disciplines, including teaching and nursing, as “non-professional.”

For Historically Black Colleges and Universities, this moment carries particular weight. These institutions have long served as engines of professional mobility, especially in fields tied to public service and care.

Teaching, nursing, social work, and allied health programs are not peripheral offerings at HBCUs. They are central to institutional identity, financial stability, and mission.

For generations, colleges that prepare educators and nurses have operated with an understanding of predictable enrollment and funding tied to professional classification. Programs were designed around historic averages: how many students typically enroll, how many graduate, how much aid they receive, and how those numbers translate into sustainable operations. Faculty lines, clinical partnerships, accreditation compliance, and student support systems were built accordingly. These are not flexible expenses. They are long-term commitments.

Reclassification threatens that equilibrium.

Professional designation is not symbolic. It determines how programs are counted, funded, and evaluated. Federal aid formulas, reporting categories, and eligibility standards are shaped by these classifications. When a discipline is downgraded administratively, institutions can experience reduced access to funding without any reduction in their obligations. Buildings still need maintenance. Faculty must still be paid. Accreditation standards still apply.

For HBCUs, the consequences are magnified. Many serve a student population that relies heavily on federal financial aid. When funding streams are disrupted, there is little buffer. Unlike institutions with large endowments or diversified revenue portfolios, HBCUs often operate close to the margin, a reality shaped by historic underfunding rather than mismanagement. A sudden loss of revenue in core programs forces difficult decisions, from reducing course offerings to freezing hires or delaying investments that affect student success.

The strain is not limited to budgets. Accreditation adds another layer of vulnerability. Teaching and nursing programs are governed by professional accrediting bodies whose standards assume professional status. A shift in federal classification introduces uncertainty. Even if accreditation

rules do not immediately change, perception matters. Prospective students, parents, and employers watch these signals closely. Programs once viewed as stable and respected may be questioned, not because of quality, but because of classification.

That reputational risk is real, and it travels quickly.

Beyond institutional concerns lies a broader, more personal impact, one that resonates deeply with college-educated women navigating careers, families, and futures. Teaching and nursing are fields dominated by women, and disproportionately by Black women. These professions have long provided a pathway to economic stability, social respect, and community leadership, even as they have struggled with chronic undervaluation and wage inequities.

Professional status has been one of the few levers available to push back against that undervaluation. Credentials matter. Titles matter. Classification matters. When a field is labeled non-professional, it becomes easier for employers to rationalize lower pay, slower advancement, and diminished authority. This is not speculative. Labor markets respond to language as much as to labor supply.

For Black women in particular, this shift echoes a familiar pattern. Work that is essential is often framed as less skilled. Care labor is expected but not fully valued. Progress toward closing wage gaps has been incremental and hard-won, built on education, certification, and institutional legitimacy. Reclassification threatens to erode that progress by signaling that these roles no longer carry professional weight.

This matters not only for those currently working in these fields, but for those coming behind them. College-aged women making decisions about majors and careers pay attention to how society values different paths. If teaching and nursing are recast as non-professional, enrollment may decline, not because the work is less important, but because the risk feels higher. That decline then feeds back into institutional instability, creating a cycle that harms colleges and communities alike.

HBCUs sit at the center of this ecosystem. They have historically taken seriously the responsibility of preparing Black women for professions that offer both purpose and stability. They have served as validators, affirming that these careers are not fallback options, but respected professions worthy of investment. Weakening the classification of their core programs undermines that role and narrows the pipeline into fields that are already facing national shortages.

At a time when school systems struggle to retain qualified teachers and healthcare systems grapple with nursing shortages, redefining these professions as non-professional sends a contradictory message. It suggests that the labor most critical to social wellbeing is somehow less worthy of professional recognition. That contradiction is especially stark for communities that depend heavily on HBCU graduates to staff classrooms, clinics, and public institutions.

This moment requires clarity. Classification is not neutral. It shapes who gets funded, who gets respected, and who gets left absorbing the cost of policy decisions made at a distance. For HBCUs, the risk is financial, reputational, and strategic. For Black women, the risk is professional and economic. For the broader

We Join the SCLC in Honoring the Memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. May his dream become a reality for all people.

P rovides equal opportunity for all, regardless of race, color, relig ion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, natural origin, age, status as a protected veteran or qualified individual w ith a disability

society, the risk is undermining the very workforce it claims to need.

The question now is whether policymakers will recognize the full scope of what is at stake. Administrative convenience cannot outweigh the long-term consequences of destabilizing institutions, diminishing professions, and narrowing pathways that have long supported Black women’s advancement. How teaching and nursing are defined today will determine not only how colleges survive, but how women’s work is valued tomorrow.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

Ending racial injustice requires all of us to work together and take real action. What can you do to help?

Educate yourself about the history of American racism, privilege and what it means to be anti-racist. Educate yourself about the history of American racism, privilege and what it means to be anti-racist.

Commit to actions that challenge injustice and make everyone feel like they belong, such as challenging biased or racist language when you hear it.

Vote in national and local elections to ensure your elected officials share your vision of public safety.

Donate to organizations, campaigns and initiatives who are committed to racial justice.

Let’s come together to take action against racism and fight for racial justice for the Black community. Visit lovehasnolabels.com/fightforfreedom

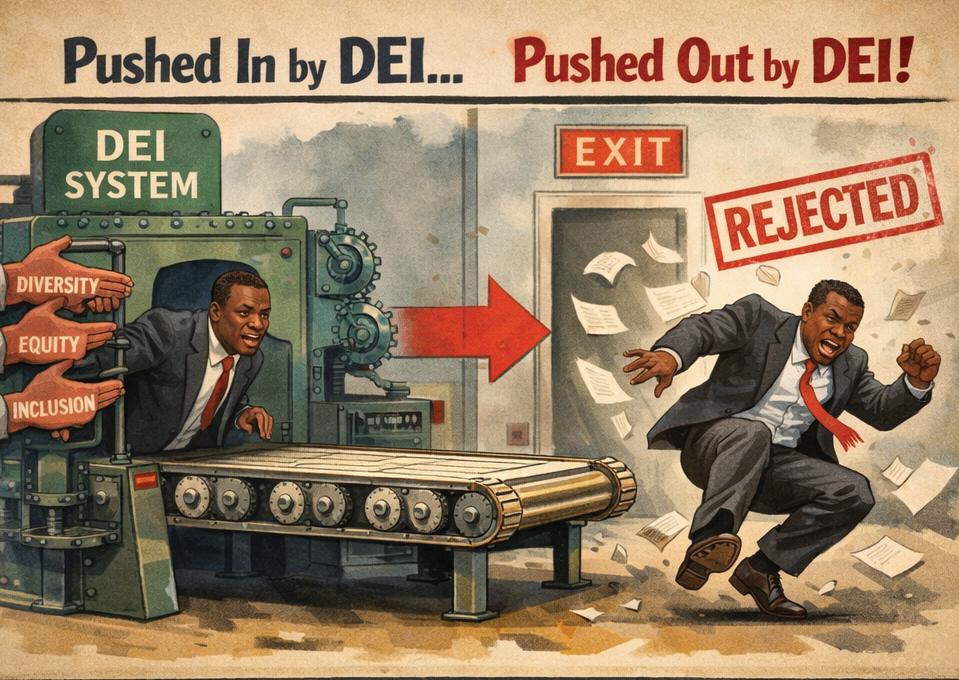

The current retreat from diversity, equity, and inclusion policies is often described as a return to neutrality or a restoration of merit-based systems. For many Black-owned businesses, that framing does not align with lived economic reality. Their experience of the American market was never shaped by neutrality, equal access, or dispassionate competition. It was shaped by exclusion that was deliberate, enforced, and sustained across generations through policy decisions, institutional practices, and informal networks of power.

As DEI frameworks are rolled back, Black entrepreneurs are once again being asked to adjust to a system that is changing without their input and rarely in their favor. The concern extends beyond the loss of programs or terminology. What troubles many business owners is that the underlying structures that restricted access to capital, contracts, and scale remain largely untouched, while the limited mechanisms that acknowledged those restrictions are being dismantled. The result is not a clean return to merit, but a reversion to conditions that historically rewarded incumbency rather than excellence.

Any serious examination of a post-DEI economy must begin with honesty about how Black-owned businesses arrived at their current position. They were not disadvantaged by accident or by a lack of preparation. They were intentionally excluded from credit markets through redlining, from supplier networks through closed procurement systems, and from asset accumulation through discriminatory housing and lending policies. These were not distortions at the margins of the market. They were central features of how the market operated. Ignoring this history does not make the market more fair; it simply makes inequity easier to deny.

Affirmative action and later DEI initiatives emerged as responses to this exclusion, not as charitable gestures but as partial correctives. They created entry points where none had existed, particularly in corporate procurement, public contracting, and certain segments of finance. Yet these entry points were often framed in ways that limited their durability. Black-owned businesses were admitted as diversity participants rather than full competitors, and their success was sometimes interpreted as evidence of institutional goodwill rather than proof of business capability. This framing allowed institutions to demonstrate progress without confronting the deeper question of whether their systems were truly open.

Over time, this approach produced a fragile form of access. Businesses gained contracts and visibility, but often without the long-term integration, capital depth, or scale opportunities afforded to their peers. The narrative that accompanied DEI participation also did quiet harm, reinforcing the idea that Black inclusion required justification beyond performance. When political and legal pressures mounted against DEI, this fragility became clear. Programs were renamed, reduced, or eliminated, and many businesses found themselves displaced not because of poor execution, but

because the category through which they were admitted was no longer defensible.

For communities that have experienced intentional disenfranchisement, this pattern is familiar. Access is extended cautiously, monitored closely, and withdrawn quickly when it becomes inconvenient. The frustration this generates is not rooted in entitlement but in recognition of a cycle that repeats under different language.

It is within this context that the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s early emphasis on Qualified Merit-Based Candidates takes on renewed significance. Under President Liggins, SCLC challenged the assumption that underserved communities required altered standards to participate meaningfully in the economy.

The QMC framework rejected the false choice between equity and excellence by asserting that Black professionals and entrepreneurs had always possessed the qualifications to compete. What they lacked was fair access to the arena.

This position matters in the current moment because it reframes merit as something that has been consistently present but selectively recognized. As institutions claim to move back toward merit-based evaluation, the critical question is not whether merit will matter, but whose merit will be visible and whose will continue to be filtered out by legacy advantage, informal networks, and unequal starting positions. A system that evaluates performance without correcting for historical exclusion does not produce neutrality; it reproduces imbalance.

The economic environment surrounding this shift adds further complexity. The retreat from DEI is occurring alongside structural headwinds that affect all small businesses but weigh more heavily on those already constrained. Access to capital remains the most significant barrier. Higher interest rates, tighter underwriting standards, and consolidation in the banking sector have reduced lending options across the board. Black entrepreneurs, who are statistically less likely to have generational wealth, collateral, or long-standing banking relationships, face these conditions with fewer buffers and less margin for error.

Policy shifts toward formally neutral procurement standards also have uneven effects. Neutrality assumes equal readiness, equal scale, and equal familiarity with complex compliance systems. In practice, it favors firms that have benefited from decades of uninterrupted participation. Businesses that entered markets later due to discrimination are penalized not only for their size, but for the history that delayed their growth in the first place. When neutrality is applied without context, it functions less as fairness and more as erasure.

Market forces compound these challenges. Technological change continues to reshape entire sectors, from retail to professional services, while automation and artificial intelligence alter cost structures and competitive thresholds. Labor markets remain volatile, and rising insurance and commercial real estate costs compress margins. For undercapitalized firms, these pressures can quickly become existential. The idea that the withdrawal of DEI occurs in a stable or forgiving economic environment does not withstand scrutiny.

Yet acknowledging intentional disenfranchisement does not require abandoning agency or

optimism. It requires a clear-eyed assessment of where opportunity realistically exists and how it can be pursued without reliance on narratives that can be revoked. In a post-DEI economy, merit must be documented with rigor. Performance data, revenue consistency, client retention, and measurable outcomes are not simply tools for persuasion; they are safeguards in systems that no longer offer patience or presumption of potential.

Alternative pathways to market access are increasingly important. Direct-to-consumer models, specialized business-to-business services, and platform-based offerings allow firms to bypass some traditional gatekeepers. Cultural fluency, trust, and responsiveness remain competitive advantages, particularly when paired with operational discipline and technological competence. These strengths are most effective when they are translated into clear value propositions rather than assumed to speak for themselves.

Capital access, while constrained, has diversified in form. Community development financial institutions, revenue-based financing, strategic partnerships, and customer-funded growth models offer options that do not depend on external validation that may shift with political winds. These approaches often scale more slowly, but they preserve ownership, reduce exposure to sudden withdrawal, and align growth with demonstrated demand rather than speculative inclusion.

There is also renewed reason to consider collective strategies. For years, Black-owned businesses were encouraged to compete individually for limited diversity-designated opportunities. In an environment that rewards scale, stability, and risk mitigation, shared infrastructure, cooperative bidding, and pooled resources can create resilience that individual firms struggle to achieve alone. Collaboration, when structured intentionally, becomes a way to counterbalance structural disadvantage without compromising standards.

This conversation holds particular weight for adult learners, returning students, and second-career entrepreneurs who make up a growing share of the Black business community. Many carry both ambition and warranted skepticism, shaped by policies that changed midstream and opportunities that proved temporary. Their caution is not resistance to effort; it is an understanding that effort alone has never guaranteed access.

The post-DEI economy will reward clarity, preparation, and execution, but it will also test whether institutions are willing to confront the deeper inequities they have long managed rather than resolved. Symbolic inclusion has proven unreliable. Performance without access remains insufficient. Sustainable wealth creation requires both competence and structural honesty.

The QMC principle endures because it refuses to separate merit from history. It asserts that fairness is not achieved by pretending the past did not happen, but by ensuring it no longer determines who is allowed to compete. Black-owned businesses are not seeking insulation from competition. They are seeking markets where the rules are transparent, stable, and applied consistently.

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

The dismantling of DEI exposes how fragile access can be when it is built on labeling rather than integration. It also creates an opportunity to insist on what should have been the standard all along: equal footing, open competition, and merit evaluated without distortion. For communities that have been intentionally disenfranchised, this is not a radical demand. It is a reasonable expectation, and one that remains central to the pursuit of durable wealth creation in the economy that follows.

If the modern Civil Rights Movement had a classroom, Septima Poinsette Clark would be one of its master teachers, not because she chased the spotlight, but because she built the infrastructure that made mass participation possible. She helped adults learn to read, write, interpret the everyday paperwork of citizenship, and then translate that knowledge into voter registration, local leadership, and organized community power. That kind of work rarely photographs well, but it holds movements together, because it turns courage into capacity and conviction into competence.

Women’s History Month is exactly the right moment to correct the familiar imbalance that still follows Clark’s name. She is too often introduced as a helpful figure in the background, a steady hand behind the scenes, an “unsung” contributor who deserves belated praise. That framing is not just incomplete, it is inaccurate. Septima Clark was a strategist and an architect of the movement’s machinery, and in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference she helped shape one of the most practical and far reaching engines for change: citizenship education. She did not simply serve the movement. She expanded its reach, made it more durable, and insisted that ordinary people were capable of extraordinary civic responsibility.

Clark’s long road to national influence began in the places where the South’s contradictions were most obvious: schools, churches, and local institutions that depended on Black labor while restricting Black freedom. She trained as an educator and lived the daily reality that education could be treated as a privilege by the same society that demanded literacy tests at the ballot box. Over time, she became convinced that literacy, civic knowledge, and leadership training were not separate goals; together, they formed a pathway to democratic participation for people who had been intentionally shut out. Her work helped formalize that pathway in the form of Citizenship Schools, which paired practical reading and writing skills with lessons on rights, government, and the process of voting.

It is important to pause here, because “Citizenship School” can sound like a tidy program name, almost like an after school enrichment activity. What Clark built was closer to a freedom infrastructure, rooted in the needs of adults who had been denied adequate schooling and then punished for the consequences of that denial. These were not theoretical seminars. They were community classrooms designed to produce confidence, comprehension, and leadership. People learned to sign their names, to understand what forms were asking, to interpret the language that often hides power behind polite phrasing, and to move through public systems without apology. The effect was practical and immediate, and it also changed the emotional relationship people had with the idea of citizenship itself.

As the Citizenship Schools approach gained momentum, it became a major part of SCLC’s work

through the Citizenship Education Program, and Clark took on a central leadership role in directing and scaling that effort. The significance of that move is easy to miss if one imagines leadership only as who stands at the podium, who signs the letterhead, or who delivers the most quoted sermon. Clark’s leadership was operational, and operational leadership is what turns a moral cause into an organized force. She trained teachers, developed curriculum, built systems for replication, and insisted that the work must be scalable because the need was massive. The model was simple but disciplined: teach literacy and civic knowledge, train local teachers, and multiply the work across communities. That is how a movement becomes a movement rather than a moment. Even the most public faces of SCLC understood how vital this kind of work was, but understanding does not always translate into equal authority, equal respect, or equal comfort with women holding power. That brings us to the truth that belongs in any honest profile of Clark, especially one written for readers who know that history is never as clean as the commemorations suggest.

Clark’s influence inside SCLC did not unfold in a gender neutral space. SCLC was clergy led, and in that era leadership was often defined through the pulpit, which meant male leadership was treated as the default even when women were doing essential organizing and educational work. Clark was not naïve about that reality, and she did not romanticize the movement so much that she ignored its internal contradictions. She spoke plainly about sexism within the broader Civil Rights Movement, and she understood that women’s labor could be praised while women’s authority was still questioned.

She experienced that dynamic personally, including moments when men challenged why she belonged in executive decision making spaces. The pushback was not always loud, but it was consistent enough to shape the emotional climate women had to navigate in order to lead. There is a particular burden that comes with being “accepted” as a woman leader in a space that is not fully committed to women’s leadership: you are expected to be grateful for access while you are still required to prove, repeatedly, that you belong. Clark’s response to that burden was not to shrink. She led anyway, and she led in ways that made it harder to dismiss her, because her programs produced measurable results and her approach built leaders who could speak and act for themselves.

None of this requires a destructive critique of early SCLC, and a serious reader does not need a simplistic verdict. By today’s standards, early leadership cultures across many major institutions, including civil rights organizations, did not always hit the mark on gender equity. That is not a scandal to shout about, it is a reality to acknowledge, because acknowledging it is how we interpret the past honestly rather than sentimentally. At the same time, it is historically notable that women did hold significant responsibility in and around SCLC’s leadership and program work, and that those contributions were recorded in ways that help prevent their erasure. Clark’s presence and impact make clear that women were not merely supportive labor. They were builders, and they were thinkers, and they were leaders who had to negotiate their authority in real time.

If you want to place Septima Clark in her proper historical position, the task is not simply to celebrate her character. The task is to expand our definition of what counts as movement leadership. Leadership is also adult education. Leadership is also curriculum design. Leadership is also training local teachers and helping communities practice leadership like a skill. Leadership is the careful work of turning fear into readiness, confusion into comprehension, and isolation into collective

That is why Clark’s work matters beyond the biography. It offers a blueprint for how democratic power is built when people are systematically denied the tools that power requires. In a system designed to keep Black citizens dependent, confused, and intimidated, teaching people to read and interpret civic language was not small work. It was an act of defiance that looked like a lesson plan. It was also a refusal to accept that democracy is only for those who were fortunate enough to be properly educated by the very institutions that excluded them.

Clark understood that empowerment is not only emotional. It is procedural. It is what happens when someone can read a ballot, fill out a form, understand a notice, and walk into a public office with their head up. Those are the “small” victories that build into large ones, because they multiply across families, churches, and neighborhoods. They also outlast the drama of any single confrontation, because a person who has learned to navigate civic systems can teach others to do the same, and a community that has learned to practice leadership can sustain itself even when national attention shifts elsewhere.

There is another reason Clark gets overlooked, and it is not only sexism, although sexism is part of it. Movements and histories tend to reward visibility. Speeches become the narrative. Marches become the narrative. Court rulings become the narrative. Meanwhile, the people who built the training programs, coached the first time voter, designed the curriculum, and turned communities into learning communities can be reduced to footnotes. Clark is one of the clearest reminders that footnotes often hold up the page.

So yes, she was a quiet architect, but quiet should never be confused with secondary. Quiet can be disciplined, deliberate, and stubbornly strategic. Quiet can be the posture of a person who does not confuse volume with impact. Clark’s work did not need a spotlight to be transformative, because it was built to replicate, and replication is how a movement survives.

For SCLC, remembering Septima Clark is not simply an act of respect. It is an act of accuracy. Citizenship education was not decorative work on the side of “real” civil rights strategy. It was foundational capacity building that helped equip communities for sustained engagement. When SCLC’s story is told honestly, Clark belongs in the main text, not in a sidebar.

Women’s History Month gives us a chance to say this plainly and without apology: Septima Poinsette Clark should be recognized as a giant in the movement and as a giant in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s history, not because she represents an inspiring exception, but because she represents a central truth about how change happens. The movement was advanced by builders as much as by broadcasters, and Septima Clark was a builder of the first rank.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue action.