TWU LOCAL 100 STANDING STRONG FOR EQUALITY IN THE WORKPLACE AND IN OUR COMMUNITIES

TWU LOCAL 100 STANDING STRONG FOR EQUALITY IN THE WORKPLACE AND IN OUR COMMUNITIES

This year, MARTA reflects on the journey of equity and progress. Our five civil rights buses, featuring Dr. King and his courageous foot soldiers, continue to inspire us to move forward – together.

PROUD TO SUPPORT

DeMark Liggins, Sr President & CEO

Martin Luther King Jr. Founding President

Ralph D. Abernathy President 1968 - 1977

Fred L. Shuttlesworth President 2004

Dr. Bernard LaFayette, Jr Chairman

Joseph E. Lowery President 1977 - 1997

Dr. Charles Steele, Jr. President Emeritus

Martin Luther King III President 1998 - 2003

Howard Creecy Jr. President 2011

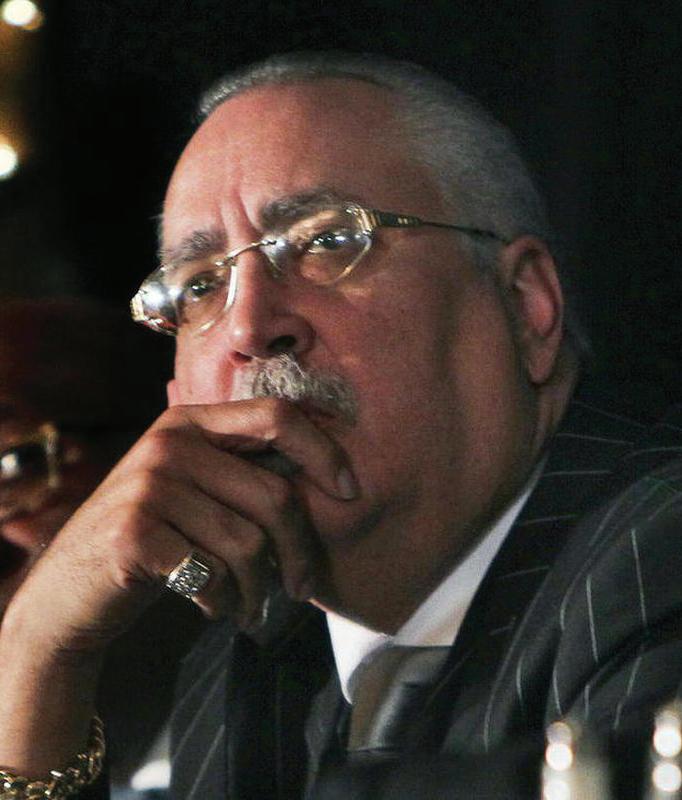

By: DeMark Liggins, SCLC National President & CEO

As we stand at the threshold of 2025, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) remains steadfast in its mission, even as we face a landscape marked by political division, rising Christian Nationalism, and systemic inequality. Reflecting on the profound insights of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?”, we find ourselves confronting many of the same struggles Dr. King outlined over five decades ago.

"As the SCLC looks forward to 2025," President Liggins observes, "the challenges have not changed despite the angst and anxiety surrounding the incoming administration. We need to remind the country that we have the same need to have urgency of justice, address economic inequality, acknowledge that poverty is violence, and that now as it has always been nonviolent strategy and action work."

Dr. King’s call to action resonates as powerfully today as it did in 1967. His exploration of justice, economic equality, and nonviolence offers a roadmap not only for understanding the work that remains but for confronting the urgent demands of our time.

In “Chaos or Community?”, King declared that "the curse of poverty has no justification in our age." He argued that a guaranteed income was not only a moral imperative but also an achievable solution to systemic poverty. Today, as economic inequality widens and inflation outpaces wages, his words remain painfully relevant.

The SCLC has always recognized that economic justice is central to civil rights. Poverty is not merely a lack of resources but a form of violence that undermines human dignity and stifles opportunity. In 2025, addressing economic inequality must be a cornerstone of our work.

Programs like SCLC’s Poverty’ Tour are designed to address systemic economic disparities by advocating for policies that expand access to living wages, affordable housing, and equitable education. Yet, we face a political environment where partisanship often prioritizes corporate profits over human needs.

President Liggins emphasizes, "Economic inequality is not a partisan issue; it is a moral one. Dr. King understood this, and so must we. It is time to demand policies that uplift working families and dismantle systems that perpetuate generational poverty."

King’s unwavering commitment to nonviolence was not merely a tactic but a philosophy rooted in

SCLC National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

love, justice, and moral courage. He wrote, "Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars."

In an era of escalating political violence and divisive rhetoric, the SCLC remains committed to nonviolent action as the most powerful tool for social change. The Kingian Nonviolence Program includes workshops and initiatives to train activists in the principles of nonviolence, ensuring that our response to injustice is rooted in dignity and strength.

"The temptation to meet violence with violence is strong," President Liggins warns. "But history has shown us that nonviolence is not only the ethical path—it is the most effective one."

Confronting Christian Nationalism

We Join the SCLC in Honoring the Memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. May his dream become a reality for all people.

P ro vide s equa l oppo rtun ity fo r a ll, rega rd le ss o f ra ce , co lo r, re lig ion , se x, se xua l o rien ta tion , gende r iden tity, na tu ra l o rig in , age , sta tu s a s a p ro te cted ve te ran o r qua lified ind ividua l w ith a d isab ility .

One of the more alarming contemporary challenges is the rise of Christian Nationalism, which distorts the teachings of faith to justify exclusion and oppression. This ideology stands in stark contrast to the SCLC’s foundation, which was deeply rooted in a theology of liberation and justice.

King envisioned a faith that united rather than divided, writing, "We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools." In 2025, the SCLC must reclaim this vision, advocating for an inclusive faith that prioritizes love, equality, and justice over political power.

The SCLC’s interfaith alliances will play a critical role in countering the misuse of religion as a tool for division. By fostering dialogue among faith leaders and communities, we can reaffirm the true purpose of faith as a force for unity and progress.

The Urgency of Justice

Dr. King often spoke of the "fierce urgency of now," a call that resonates deeply as we navigate today’s social and political climate. The SCLC’s work in 2025 will require not only urgency but also perseverance, as we confront systemic racism, voter suppression, and the erosion of democratic norms.

The incoming administration’s priorities are a source of both concern and opportunity. While partisanship often hinders progress, the SCLC will continue to push for policies that reflect the values of justice and equality.

President Liggins underscores this commitment, stating, "We cannot wait for change to come from the top. The SCLC has always been a grassroots movement, and it is from the ground up that we will build a more just and equitable society."

One of the most significant obstacles to progress today is the deepening divide between political parties. King envisioned a "beloved community" that transcended divisions, writing, "We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny."

In 2025, the SCLC will prioritize building bridges across ideological divides, recognizing that meaningful progress requires partnership over partisanship. By fostering coalitions that include activists, policymakers, and community leaders, the SCLC will work to create a shared vision for justice and equality.

As we reflect on the themes of Chaos or Community?, it is clear that the challenges of King’s time are not confined to history. They are the challenges of our time as well.

President Liggins calls on all of us to embrace King’s vision with renewed commitment: "We are not merely inheritors of King’s legacy; we are stewards of his dream. It is our responsibility to confront the chaos of our time with the courage to build community. This is the work of 2025. This is the work of the SCLC."

By addressing economic inequality, embracing nonviolence, countering Christian Nationalism, and fostering unity, the SCLC will continue to honor King’s legacy while shaping the future of civil rights. In the words of Dr. King:

"We must walk on in the days ahead with an audacious faith in the future."

Let us walk together, with faith, determination, and the unwavering belief that justice will prevail.

SCLC National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

Corner

Written By: Dr. Bernard Lafayette , Chairman of the Board

I am thinking of how important it is for all of us to feel connected during this particular time in our history. One way to accomplish that is to help people remember that even though we may live in different towns, states, and even countries, have different ideas about things, speak different languages, we still have more in common with each other than we have differences. More “one-ness” and more “wonder-full-ness” that is magnified by sharing music with each other. The beautiful old song, “We Shall Overcome” comes to my mind, both because of it’s soothing beautiful sound and it’s even more beautiful message.

While searching for the history of the song, I came upon this article from the Library of Congress which perfectly articulates our hopes for healing and inclusiveness. I shall share it with you here.

This article has been reprinted from The Library of Congress Blogs:ISSN 2692-1731

FOLKLIFE TODAY

American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project

Although folksingers Pete Seeger, Guy Carawan, and Frank Hamilton registered copyright on “We Shall Overcome” in 1960, the song has a long and fascinating history with contributions from many activist-singers. We can trace it back to two separate songs from over a hundred years ago, the lyrics from “I’ll Overcome Some Day” written by the Reverend Charles Tindley in 1903, and the melody from a traditional African American gospel song called “I’ll be All Right.”

Pete Seeger remembers in his book, Where Have All the Flowers Gone (Sing Out, 1993), that Zilphia Horton, a folk singer and activist from the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, first heard the song in 1946 when she went to help tobacco workers with a labor strike in Charleston, South Carolina. She was struck by the moving simplicity of it and how one picketer, Lucille Simmons, would sing it very slowly and powerfully. Simmons is credited with changing the lyrics from “I” to “We.”

A year later, Horton taught it to Seeger when he came to visit the Highlander Folk School. Horton and Seeger published the song in his newsletter People’s Songs in 1948, although Seeger thinks this published version was incorrect. He notably changed the lyrics from “We Will Overcome” to “We Shall Overcome” and also added two new verses including “We’ll walk hand in hand.” He remembers his return to Highlander in 1957, when he met Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and the Reverend Ralph Abernathy. Although he knew the words to “We Shall Overcome,” he finally worked out the musical accompaniment to the tune on this visit. Folksingers Guy Carawan and Frank Hamilton changed the rhythm of the song, which helped it spread like wildfire at protests across the country, establishing it as the anthem of the struggle.

Later at the Highlander Folk School, Guy Carawan taught the song to a large group of African American college students who came to the school to learn protest music at the “Singing in the Movement” conference in 1960. These students would go on to stage protests in Greensboro, North Carolina, Nashville, Tennessee, and many other cities across the South. They called themselves SNCC– the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and established themselves as young radicals who refused to wait for change. As these students endured harassment at the sit-ins, they gained strength through this new song they had learned at Highlander.

On July 22, 2011, Seeger sat down with Joe Mosnier to do an oral history interview for the Civil Rights History Project and remembered these moments:

Seeger, Carawan, and Frank Hamilton were convinced to register the copyright on their version of the song. They donated all of the royalties to a non-profit organization they founded called the We Shall Overcome Fund, which still provides grants “to nurture grassroots efforts within African American communities to use art and activism against injustice.”

Years later in his 1972 book, The Incompleat Folk Singer (Simon and Schuster), Seeger admitted that the song had become somewhat passé. His friend Lillian Hellman, the playwright, told him, “What kind of namby-pamby, wishy-washy moaning, always ‘some day, so-o-omeday!’ That has been said for two thousand years.” Seeger asked his friend, the noted singer and activist Bernice Johnson Reagon, what she thought of that. She responded, “But still if we said we were going to overcome next week, it would be a little unrealistic. What would we sing the week after next?”

Here are the verses that Seeger liked to sing as he listed them in Where Have All the Flowers Gone:

1. We shall overcome…

2. We’ll walk hand in hand…

3. We shall live in peace…

4. We shall all be free…

5. We are not afraid…

6. We shall be like “Him”…

7. We shall stand together…

8. We shall work together…

9. The Lord will see us through…

10. We shall end Jim Crow…

11. The truth will set us free…

12. The whole wide world around…

13. Black and White together…

14. Love will see us through…

15. We shall stand together…

16. We shall overcome…

Are any of the verses above still relevant today? Here is my challenge to you! Choose a verse that “speaks” to you in a special way and teach it to another person. Then, all you elders, find a child and help him or her to participate by writing another verse and sending it to me here at SCLC. Young folk: please write the new verse in your native language along with the English translation. Hopefully, we will be able to publish some of them. Be sure to include your name, your age, and your language.

Following is sheet music for “We Shall Overcome, followed by a few verses in both Spanish and English

We Shall Overcome

Nosotros venceremos, nosotros venceremos Nosotros venceremos ahora O en mi corazón, yo creo Nosotros venceremos

We shall overcome, we shall overcome We shall overcome some day

O deep in my heart, I do believe We shall overcome some day

No estamos solos, we are not alone

We are not alone today

O deep in my heart, en mi corazón

Yo creo, I do believe

That we shall overcome some day

Some day, some day

Some day, some day

We shall overcome some day

English lyrics by Zilphia Horton, Frank Hamilton, Guy Carawan, and Pete Seeger https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/26/business/media/we-shall-overcome-copyright.html

Spanish lyrics by El Teatro Campesino (Farmworkers Theater) http://19280265.weebly.com/nosotros-venceremos.html

You may watch a video of Pete Seeger singing “We Shall Overcome here: mayhttps://m.youtube.com/watch?v=1osKWCDXl40

Please send the new verse(s) you composed via email to me, Dr. LaFayette at info@nationalsclc.org

Or mail to my attention at 320 Auburn Ave, NE, Atlanta, GA 30303. In closing, my wife Kate and I wish you and yours all the good things that accompany Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! And always remember that the title of the song is “We Shall Overcome” but we are already living that dream, experiencing that state of mind since time began. Every minute of every day, we are overcoming, and we shall not be moved!

As we approach the season of reflection and reverence marked by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s holiday and Black History Month, it is important to revisit the monumental history of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)—an organization that not only shaped the Civil Rights Movement but also continues to champion the cause of justice and equality. America has rightly celebrated Dr. King’s life and legacy. Federal holidays bear his name.

A majestic memorial stands in Washington, D.C., etched with his powerful words. His childhood home and surrounding neighborhood are preserved as a National Historical Park. These tributes are deserved and monumental, yet they tell only part of the story. Oddly absent from this national narrative is the organization that Dr. King envisioned, nurtured, and used as the engine of the Civil Rights Movement: the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“The Southern Christian Leadership Conference is not merely an organization, it is a living movement,” Dr. King once said. “It is the vital force that has led the way in nonviolent direct action and the fight for justice and equality.” Founded in 1957, the SCLC was created as an umbrella organization to unite Black leaders and coordinate the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement through nonviolent direct action. It became the platform through which Dr. King articulated his dream and mobilized a nation. From the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the March on Washington, from Birmingham’s demonstrations to Selma’s marches, the SCLC was not merely present—it was pivotal. Without the SCLC, there would have been no Civil Rights Movement as we know it.

The SCLC’s strategy of nonviolence was deeply rooted in Christian principles and inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. This approach resonated not only with the Black church but also with allies from various racial and religious backgrounds, fostering a coalition that transcended traditional boundaries. The philosophy of nonviolence required immense discipline and courage. Protesters faced brutal beatings, arrests, and even death, yet they stood firm, embodying the moral high ground that ultimately exposed the injustices of segregation to the world.

The impact of the SCLC extends beyond its campaigns and victories. The organization has been graced with leaders who have received the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, including Dr. King, Rev. C.T. Vivian, Rev. Joseph Lowery, Rep. John Lewis, and Diane Nash. These luminaries not only shaped the SCLC but also served as bridges to other organizations, such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). John Lewis, for instance, held leadership roles in both the SCLC and SNCC, exemplifying the cross-pollination that enriched the Movement. Their collective work demonstrated the power of unity and moral clarity in the face of systemic injustice.

One of the most notable examples of this unity was the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech. The event, co-organized by the SCLC and other civil rights groups, drew over 250,000 participants to the National Mall, making it one of the largest demonstrations in U.S. history. This moment was not only a testament to the organizational prowess of the SCLC but also a turning point that galvanized public opinion and set the stage for legislative change.

The SCLC’s influence was not limited to its leaders. During the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, thousands of pastors and church leaders considered themselves extensions of the SCLC, embodying its commitment to Christian principles and nonviolent direct action. These clergy members played a crucial role in mobilizing communities, providing both spiritual and logistical support for marches, boycotts, and voter registration drives. In cities across the South, local SCLC chapters became hubs of activism, fostering a sense of collective responsibility and empowerment among Black Americans.

In a time when America was at a boiling point, the SCLC was the moral compass that spoke truth to power, insisting that Black Americans deserved every right and privilege promised by the Constitution. This was a radical and disruptive stance in a nation that had relegated Black citizens to second-class status for centuries. The SCLC’s insistence on full citizenship for Black Americans was not merely a demand for equality but a profound declaration of dignity and humanity.

Our efforts bore fruit in landmark achievements. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were not abstract victories; they were the result of relentless advocacy, strategic planning, and courageous action spearheaded by the SCLC. When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed these transformative pieces of legislation, the invitations extended to the leaders

of the SCLC—a testament to the organization’s central role in reshaping America’s moral and legal landscape.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, dismantling the legal framework of segregation and opening doors to equal opportunities in education, employment, and public accommodations. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 addressed the systemic disenfranchisement of Black voters, particularly in the South, by prohibiting discriminatory practices such as literacy tests and poll taxes. These legislative milestones were the culmination of years of grassroots organizing, nonviolent protests, and unwavering determination led by the SCLC.

As the movement evolved, the SCLC also adapted, addressing issues beyond racial segregation. Economic justice, healthcare, and education became central to its mission, reflecting the interconnected nature of civil rights. Initiatives like the Poor People’s Campaign, launched in 1968, sought to address the economic inequalities that perpetuated systemic racism. Although Dr. King’s assassination in the same year dealt a devastating blow to the movement, the SCLC persevered, continuing to advocate for policies that uplift marginalized communities.

The legacy of the SCLC is not confined to history books; it is a living, breathing force that continues to inspire and mobilize. Today, under the leadership of Mr. DeMark Liggins, Sr., the SCLC remains at the forefront of social justice, addressing contemporary issues such as voting rights suppression, police brutality, and economic inequality. As Mr. Liggins aptly stated, “The SCLC is the ink with which the story of the Civil Rights Movement was written.” This ink has not dried; it continues to write new chapters in the ongoing struggle for justice and equality.

As we honor Dr. King, let us also remember the organization that was his vehicle for change. The SCLC is proud and unashamed to declare that it is the enduring force behind the story of justice, equality, and nonviolence that transformed a nation—and continues to inspire the world today.

We believe in equal opportunity for all regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, or ethnic background.

Western Construction Group Inc.

Katz, Sapper & Miller, LLP

Cooperative Energy

Associated Grocers Inc.

Harley Ellis Devereaux (HED)

By: Kevin Kimble Executive Director SCL Global Policy Initiative

Dear Readers,

This is a letter we received from a New Jersey business owner. I think it sums up the plight we face quite succinctly.

Dear Mr. Liggins,

In 2020, our trucking company achieved WMBE, MBE, and DBE certifications after significant effort and expense. Over the next three years, we strived to leverage these certifications in the New Jersey cannabis industry and government contracting, only to be shutout and burdened with increased debt and unanswered questions.

Recently, the Murphy administration’s New Jersey Feasibility Study disclosed a disheartening reality: African Americans were awarded a mere 0.17% of government contracts. Had this information been available in 2020, our strategy would have been markedly different. Today, the new administration is phasing out the certification process and DEI initiatives, raising a critical question: How do we move forward? We cannot stand idly by as our tax dollars benefit others while we are excluded.

Now is the time to act. I am collaborating with a national organization to launch an initiative designed to succeed in New Jersey and set a precedent for the nation. We are organizing a roundtable in early January, where your involvement is essential. Together, we can ensure that opportunities are extended to our community.

Will you join us to make a difference. Your voice is crucial in shaping our future.

Respectfully,

Martin S. Mason V.P Business Development Rapid Runs Transportation New Jersey

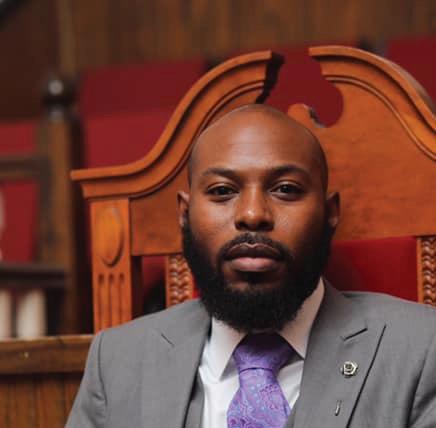

By: DeMarkus Thomas-Brown Regional Director, Good Dads

As we look toward 2025, we in Columbia, Missouri are alertly aware of the continued arduous path to equity and equality demonstrated by the adherence and acknowledgment of the God given rights and status of all Americans. With or without favorable results of an election the work of justice, the pursuit of righteousness, and the twin labors of advocacy and activism continue. We believe the SCLC will be a pivotable vehicle to activate voices in our community that will be heard in the civil and legislative arenas. The SCLC will present us with the ability to hold our governing entities accountable to adequately serve our marginalized populations, to make sure their voices are heard, and equitable solutions are implemented that work to alleviate poverty and the mass effects of systemic racism that has occurred in Columbia and Central Missouri.

Historically longevity and effectiveness in the civil rights movement is necessitated by the partnerships of various organizations working in tandem to garner communal support, strategic foresight, and legislative impact for example NAACP, SCLC, and SNCC in Selma, Alabama and Jackson, Mississippi. The ethic and value of partnership and collaboration held by the SCLC has already aided our advancements in activating the inactive through voter registration block parties and neighborhood canvasing because we know from the national to the municipal level, it’s not about who votes but who’s not voting and being able to bring action to disillusionment and vision to disenfranchisement. We worked alongside both the NAACP and the League of Women Voters to expand our reach both with outreach and constituency with our voter registration efforts this year.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) has been pivotal in uniting the call of the church with the unction of social justice. We don’t look to alienate the churches when it comes to the efforts of civil rights and justice, but to mobilize those who are nurtured by the teachings of Christ. We look to unite like mind and visioned churches in our area, moving from pew to purpose. The SCLC will provide a unified front for all churches in Columbia, equipping parishioners to assist residents in their distinct neighborhoods where lack of resources exists that would allow for the equitable thriving of those who reside in those places and spaces. The SCLC will aid as the conduit for local organizations to tackle the most critical human rights and spiritual needs.

Due to our unwavering focus on community enrichment, we’ve focused our attention to increased home ownership by black individuals in Columbia. Both national and local disproportion of home ownership by race is staggering especially when predominantly black neighborhoods are being gentrified by the evidence of pricing out those who historically resided in a neighborhood and causing demographic shifts by outside ownership. Government subsidized rental programs in Columbia have also played a part in displacing black residence

from city center to rural suburbs because of the premium pricing of the property in the city center. To combat these discriminatory practices our chapter is working with residential bulk property purchasers who will in turn sell the properties to those who have historically occupied the neighborhoods to see black property ownership increase in Columbia.

Our chapter is currently working within the Columbia Public School system to ensure and advocate for equitable educating and access for our marginalized student populous. Currently black students make up about 12% of the school population, 5% of enrollment in AP and dual credit courses, and 75% of disciplinary incidents. As we see the open attach on affirmative action and DEI programs nationally, we are working on the local level to strongly encourage our school administrators that opportunity is not access. We now have a standing memorandum of understanding (MOU) with our public-school systems that allows us to work before school curriculum to empower our students for greater achievement from those who look like most of them.

We’ve also had to look at upward mobility and economic advancements among our returning citizens. Mass incarceration has been glaring especially in the black community and when individuals return home from incarceration they are usually met with few options for employment and housing. Our chapter has been instrumental in working with housing providers that will rent to those with justice involvement in Columbia. We affectionately call them “second chance” landlords and housing. We’re working to change the trajectory and narrative for those returning to Central Missouri so that recidivism isn’t the only option and that thriving can be had for the least of these as well. In the words of Dr. Bernard Lafayette “there are stark differences between a movement and a demonstration. A people must internalize a movement, like in Montgomery, people had internalized the movement and gained enough dignity that they’d rather walk with their God given dignity than ride in the back of buses. Marches and demonstrations are temporary, movements are designed to change the conditions and there are no timetables on movements.” Though the path forward in 2025 will be wrought with difficulty, we in Central Missouri have adhered to a dream that empowers perseverance, and we look to continue forward with the momentum of the SCLC that has birthed movements.

D'Markus Thomas-Brown is currently the Regional Director at Good Dads. He previously was the Director for the Recovery Support & Reentry Opportunity Center (ROC) in Columbia, He currently serves with the Boone County Overdose Response Coalition, the Central Missouri Recovery Coalition (CMRC), and the Mid-Missouri Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Council. He is an ordained minister who also serves as a pastor of Confluence Church.

By: Autumn Smith SCLC Historian

Nikki Giovanni once said, “the art of being a woman is hiding your pain behind a smile”, and 2024 exemplified that quote for African American women policymakers. As the United States came upon the opportunity to elect the first African American woman to the highest court in the land, the imagery and humanity of African American women were challenged and degraded. Vice-President, Kamala Harris, ran for president of the United States, and during her campaign, stereotypes related to Black women were forced upon her more than actual facts. The election of 2024 was more than just the presidential election though. Election season is a time for not only elect the President, but local and state officials. As some Americans dwelled on the unfortunate loss of Kamala Harris, there were still many victories for African American women during the election season. For the first time ever, two African American women will serve in the Senate simultaneously, Representatives Angela Alsobrooks (MD) and Lisa Blunt Rochester (DE)

Just a few years ago, there were no African American women in the United States Senate, and now Alsobrooks and Rochester will serve together, bringing the total of African American women in history to serve as Senators to five.

The 2024 election marked a milestone in the history of American politics: for the first time, two African American women will serve in Congress simultaneously. This achievement not only represents a significant shift in political representation but also highlights the growing influence of Black women in shaping national policy and politics. As we reflect on this moment, it’s crucial to examine the role of Black women in the political landscape, and what this unprecedented achievement means for the future of American democracy.

Angela Alsobrooks is the United States senator-elect from Maryland

While African American women have been at the forefront of social justice movements and have long been pivotal to Democratic victories, their presence in the limelight and as elected officials have often been limited. When we think of Coretta Scott King, most people correlate her as simply Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s wife, but she was so much more. Coretta was a classically trained singer, pianist, violinist, and college graduate. Her accomplishments are often overshadowed by the work of her husband, but nonetheless, she accomplished more than most people recognize. Shirley

Chisholm is also a historic figure that is often overlooked, as she was the first African American woman elected to Congress and to run for President of the United States. Chisholm’s career and story are not a part of political pop culture, which leaves us to wonder, will her story be remembered by future generations? Both King and Chisholm's fight for social and political change was tireless and undeniable but often met with opposition for their race and gender. Even though Chisolm and King faced criticism throughout their careers, they approached it with grace and a smile on their face.

Historically, the path for Black women in politics has been fraught with systemic barriers, including racism, sexism, and a lack of institutional support. Figures such as Maxine Waters, who has served in the House of Representatives for over three decades, have paved the way, but they did so in a political environment where their numbers remained few and their contributions frequently overlooked.

Despite these challenges, African American women have continued to mobilize, organize, and lead in their communities and beyond. Their political engagement is rooted in a history of activism that spans from the civil rights movement to contemporary struggles for racial justice, economic equality, and gender equity.

Angela Alsobrooks is a Democratic representative from Maryland. In 2018 she was elected as executive of Prince George County. Alsobrooks made history as the first woman to hold this position in the county. Prior to becoming County Executive, Alsobrooks served as the State’s Attorney for Prince George’s County, where she was both the first woman and the first African American to occupy that role. Throughout her career, Alsobrooks has been a strong advocate for criminal justice reform, economic development, and educational improvements in her community. She has worked to enhance public safety, promote inclusive economic growth, and improve the quality of life for residents of Prince George’s County. Known for her leadership and commitment to public service, Alsobrooks has been a trailblazer in Maryland politics, gaining recognition for her efforts to expand access to justice and advocate for underrepresented communities.

Lisa Blunt Rochester is an American politician who has represented Delaware's at-large congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2017. As a member of the Democratic Party, she has made history as both the first woman and the first African American to hold this position in Delaware. Before her time in Congress, Blunt Rochester held various leadership positions, including serving as Delaware's Secretary of Labor and advocating for public policies related to workforce development, education, and social justice. Recognized for her ability to work across party lines, she has prioritized issues such as access to healthcare, economic equality, and climate change. Throughout her congressional career, Blunt Rochester has been a proactive representative for her constituents, championing legislation aimed at fostering equity, job creation, and a fair economy. Her leadership and dedication to public service have positioned her as a trailblazer in Delaware politics and a significant advocate for marginalized communities nationwide.

The significance of having two African American women serving in Congress is not simply symbolic. It represents a shift in the power dynamics of Washington, D.C., and it underscores the importance

National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

of diverse voices in policymaking. African American women have long been political powerhouses in local, state, and national elections, but their representation in Congress has often been limited. Having Rochester and Alsobrooks serve together creates a unique opportunity for collaboration, as they both represent distinct, yet intertwined, experiences of Blackness and womanhood.

For communities that have historically faced systemic racism, economic disenfranchisement, and political underrepresentation, having African American women in power provides a sense of hope and validation. It signals to younger generations of Black girls and women that they, too, can aspire to positions of leadership. Furthermore, their presence in Congress brings attention to the issues that disproportionately impact Black women, such as access to healthcare, reproductive justice, voting rights, and criminal justice reform.

While the achievement of two African American women serving in Congress simultaneously is historic, it also highlights the continued need for progress. Black women still face significant barriers to political entry, from voter suppression to unequal access to campaign funding and institutional support. However, the 2024 election is a testament to the power of grassroots mobilization and the growing political infrastructure supporting Black women candidates.

Looking ahead, it is clear that the rise of African American women in politics will continue to reshape the future of American democracy. Their leadership will be crucial not only in advocating for the rights of Black communities but also in influencing national conversations on race, class, gender, and the economy. The success of Rochester and Alsobrooks represents a broader movement, one that challenges the status quo and demands a more inclusive and equitable political system.

As we look to the future, the historical achievement of having two African American women serving in the Senate together should not only be celebrated but also serve as a call to action. While the barriers to political power remain significant, the progress we’ve witnessed reflects the resilience, determination, and vision of African American women who have long fought for a more just society. With leaders like Angela Alsobrooks and Lisa Blunt Rochester at the helm, we can expect continued progress in the fight for racial justice, gender equality, and political representation for all.

By: Danielle Davis

“We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.” –Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

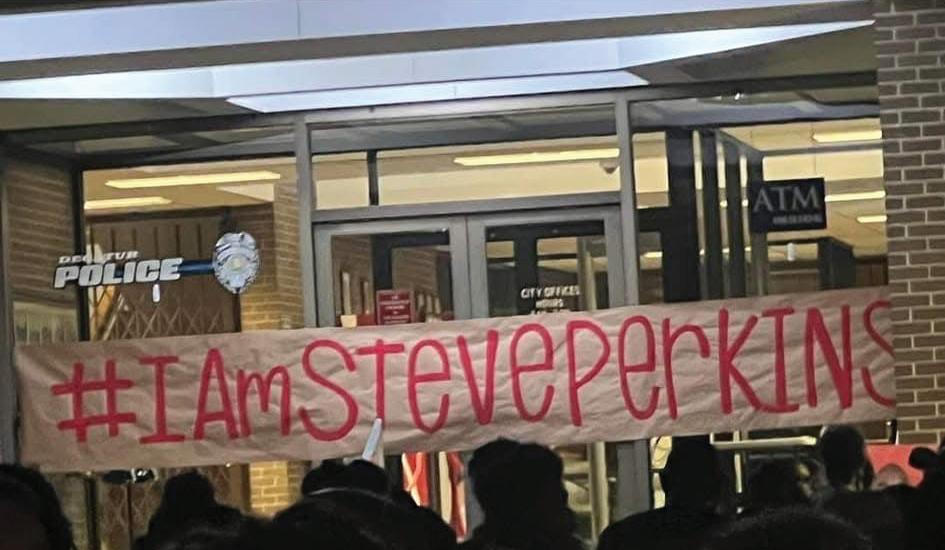

Decatur, AL – A solemn group of people stand in a circle outside Decatur’s City Hall. Among them is Nicholas Perkins, his hands tucked into his pockets, his eyes fixed on the ground as he listens to the frustration and anger echoing around him.

Over a year ago, Nicholas stood on the steps of this same building, addressing a passionate crowd after the brutal killing of his younger brother, Stephen Clay Perkins, at the hands of a Decatur police officer.

Stephen, a loving husband, father, and beloved member of the community, was killed in his front yard during an illegal attempt to repossess his vehicle in the early hours of September 29, 2023. The tragedy shattered his family, traumatized a community, and laid bare the systemic issues festering within the city’s leadership.

Initially, Decatur Police Chief Todd Pinion released a statement claiming Stephen Perkins had refused to drop his weapon and turned it on officers. However, the narrative quickly unraveled when doorbell camera footage emerged, contradicting the police account.

Hundreds of people from all walks of life took to the streets, chanting, “I am Steve Perkins!” and “Justice for Steve!” The city was soon adorned with billboards, murals, and t-shirts bearing Steve’s name and likeness. Nick Perkins was often seen in his own “Justice for Steve” t-shirt with the unique phrase “I am my brother’s keeper.” Serving as a poignant reflection of his grief and his personal calling.

“As a big brother, I always protected Steve,” Nick recalls, “I can’t describe how it feels to have that responsibility ripped away from me. It’s a pain that never leaves you.”Standing on the city hall steps last year, Nick told a crowd of hundreds “Decatur, we have work to do.”

Almost fifteen months later, Nick stands with a smaller group—those

who have endured relentless retaliation from Decatur Police. Among them is Sarah French, a 47-year-old healthcare worker and grandmother. Tears streak her face as she reflects on her own ordeal. Sarah is one of five individuals recently convicted of disorderly conduct for allegedly participating in a peaceful protest in 2023.

Decatur’s idyllic image as a small Southern town has been shattered, revealing a dark reality steeped in systemic oppression. Over 30 citizens have been arrested, and nearly 80 claim to have been harassed, beaten, or unlawfully detained since protests began.

Am I My Brother’s Keeper?

“All that is required for evil to succeed is for good men to do nothing.”- Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

The harassment began subtly—individuals followed home from city council meetings or pulled over for minor infractions. But it quickly escalated.

• Cornelius Echols was arrested for allegedly tossing a piece of toilet paper out of his window on his way home after speaking at a city council meeting. Six police vehicles surrounded them, charging them with “criminal littering.”

• Sarah French found her home surrounded by officers on Thanksgiving, and her son was arrested months after attending a protest.

• Sierra Taylor, another protester, was punched in the face by an officer after a rally. The officer was caught on camera telling Taylor he “enjoyed” it.

• Terrence Baker, a business owner, was arrested live on Facebook for asking an officer a question. Months later, he was followed home and arrested in his driveway on baseless drug charges.

• Shoronda Acklin was chased and pulled over by five Decatur Police officers for waving at a group of protesters on her way home.

• A 66-year-old grandmother was arrested and put in jail for disorderly conduct for blowing her horn and waving at a group of protesters while she was out running errands.

These incidents are just a few of the stories from citizens of Decatur that paint a chilling picture of systemic oppression in Decatur.

Decatur’s Mayor Tab Bowling has been accused of using tactics from the 1960s when he and a police officer sprayed protesters with sprinklers and attempted to ban demonstrations entirely—a move legal experts decried as unconstitutional.

National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

Those affected claim that even Decatur’s municipal court has been complicit, dragging out cases against protesters for over a year to exhaust their resources and morale.

For many, the events following Stephen Perkins’

death are painfully familiar. Decatur has been tied to a long history of racial injustice, from the conviction of Tommy Lee Hines to the infamous Scottsboro Boys trials.

“This city has been stuck in a cycle of racist oppression for decades,” says local Pastor Patrick Tucker. “The same ‘good ole boy’ system that allowed these injustices to happen in the past is still in place today.”

Hundreds protest the murder of Stephen Clay Perkins at the hands of Decatur Police

Testimonies during court hearings have revealed even more troubling details.

An employee of the Decatur Police Department testified that Chief Pinion instructed her to monitor city council meetings and identify individuals involved in protests. Another police officer admitted in court to using a fake social media profile linked to threats and harassment against protesters.

“The targeting is deliberate,” says Cornelius Echols. “They arrest you for something trivial, keep you on bond, and then revoke it for no reason. It’s a trap designed to silence us.”

“We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice"- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Baily “Mac” Marquette, the officer who shot and killed Stephen Perkins, was indicted on murder charges and faces trial in April of 2025.

Despite the fear and intimidation, the community refuses to back down. Grassroots organizations, churches, and individuals continue to rally behind the Perkins family.

Nick Perkins says that his brother’s death thrust him into advocacy, driving him to seek justice not only for his brother but for an entire community. “I am my brother’s keeper” has become more than a phrase across a t-shirt, it has become a rallying cry for those in Decatur who feel a duty to stand up and protect those in the fight for justice.

Over the past 15 months, Perkins and his family have met with the FBI multiple times to aid in a federal investigation into the officers involved in Stephen's killing, as well as the ongoing intimidation faced by community members.

Nick and other supporters have also traveled to the State Capitol to support legislation for stronger body camera laws and have partnered with advocacy groups to provide legal aid to protesters.

Meanwhile, as part of a joint effort among advocates and a group of civil attorneys, plans are underway to file a class-action lawsuit against the city, seeking accountability for the harassment and violence endured by citizens.

Perkins in "I am my brother's keeper" sweatshirt "

As the city of Decatur grapples with its past and present, its citizens remain steadfast in their pursuit of justice.

“We can’t pass this city, as it is, on to our children,” Pastor Patrick Tucker declares. “The system must change ,so future generations can enjoy the same rights and freedoms as everyone else.”

“I don't often think about the fact we are making history.” reflects Sierra Taylor “I’m just trying to see change so that our future generations don't have to worry about being murdered or beaten just for being a person of color or supporting people of color.”

Nicholas Perkins agrees. “People often remember Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, as they should. But tens of thousands of people participated in the civil rights movement.

They fought for us to have a better tomorrow. That’s who those who are fighting for justice in Decatur are—keepers of tomorrow.”

"The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy." - Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Over the fifteen months, several organizations and individuals in the community have hosted vigils, parties, and outdoor events in the spirit of honoring Stephen Clay Perkins.

The Perkins family has also turned their grief into action. They’ve established initiatives like the “Good Neighbor” Award, honoring acts of service within the community, and “Clay-Perkins Serve Day,” to do acts of service and provide meals to the homeless in Stephen’s memory.

“These acts of remembrance are a way to ensure that Steve’s legacy lives on,” says Perkins's cousin Sheree Head “Our goal as a family is to create a lasting legacy for Steve, initiatives that will forever remind this city of who he was.”

Stephen’s sister-in-law, Angela, named her new gym “Legacy Fitness,” in honor of his dream of opening his own fitness center. “We plan to paint a mural of Steve one day, so every time you come through the door; you will be reminded of Steve.”.

On October 11, 2024, Decatur Youth Services named its new gymnasium after Stephen’s, mother, Zelma Clay Perkins, to honor her sacrifice.

At the unveiling ceremony for the new gymnasium, Nick proudly addressed the crowd, saying, “In the future, when people ask, ‘Who is Zelma Clay Perkins?’ the answer will be, ‘She is the mother of the man who changed this city forever.’”

National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

In recent years, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs have become a flashpoint in America’s ongoing cultural and political battles. Proponents champion these initiatives as essential tools for addressing systemic inequities, while critics claim they promote division or even reverse discrimination. As debates over their future intensify, efforts to eliminate DEI programs in government, corporations, and higher education are gaining momentum.

For many minorities, particularly Black Americans, this shift raises a question: What exactly is being lost? As DeMark Liggins, Sr., President and CEO of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), observed, “I have a fear there is so much angst and anxiety about the elimination of these programs that we are forgetting that the programs were never working for us in the first place.”

This provocative statement reflects a painful truth for many Black Americans. Despite decades of DEI efforts, Black representation in influential spaces— whether in corporate boardrooms, elite universities, or government leadership— remains far below proportional representation. While the programs were designed to address systemic inequities, the outcomes have often fallen short of expectations. Yet the deliberate dismantling of these programs signals something even more troubling: a potential effort to undo progress rather than acknowledge and fix the flaws in these initiatives.

The current assault on DEI programs can be traced back to the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023), which overturned affirmative action in college admissions. This ruling declared that race-conscious admissions policies violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, effectively ending decades of precedent. The decision has since reverberated far beyond academia, sparking a cascade of changes in policies and practices across corporate America, public institutions, and state governments. In some cases, DEI offices have been shuttered entirely, while in others, their mandates have been significantly curtailed. Proponents of these rollbacks argue they are restoring meritocracy and fairness. Critics, however, see these moves as thinly veiled attempts to dismantle efforts aimed at addressing systemic racism and inequality.

Communities are now grappling with what these changes mean for access and opportunity. For Black Americans, the implications are profound. As Liggins notes, “Since these programs were not working as intended, it lends itself to reason there are more nefarious reasons at play for getting rid of them at all.”

A central argument used to justify the elimination of DEI programs is the pervasive myth that such initiatives allow unqualified minorities to gain unfair advantages in hiring, contracting, or admissions. This narrative, however, is fundamentally flawed.

From the perspective of organizations like SCLC, DEI efforts and race-conscious policies were never about lowering standards; they were about leveling the playing field. Historically, qualified Black candidates have been systematically overlooked, often excluded from opportunities due to implicit biases, institutional racism, or lack of access to influential networks. DEI programs aimed to rectify this by ensuring that race could be one of many factors considered to correct historical inequities.

Even with these programs in place, progress has been uneven and insufficient. While some gains have been made—such as slight increases in the presence of Black professionals in corporate leadership—these efforts have fallen far short of achieving equity. Data consistently shows that Black Americans remain underrepresented in nearly every sector, from Fortune 500 CEOs to university faculty.

If DEI programs were not fully achieving their goals, why has there been such a strong push to eliminate them? Liggins suggests that the answer lies not in the effectiveness of these programs but in the cultural and political moment. The elimination of DEI initiatives coincides with a broader backlash against social progress, fueled by the fear of a changing demographic landscape and resentment over perceived loss of privilege among dominant groups.

By targeting DEI programs, critics have found a way to undermine systemic efforts to address inequality while framing their actions as a defense of fairness. This strategic shift taps into anxieties about meritocracy and creates a scapegoat for broader societal issues, diverting attention from the structural barriers that continue to hold marginalized communities back.

The ongoing debate over DEI programs must be understood within the broader context of racial equity in America. The challenges facing Black Americans are not confined to employment or education; they permeate nearly every aspect of life, from healthcare disparities to the criminal justice system.

For organizations like the SCLC, the fight for civil rights has always been about addressing these systemic inequities head-on. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, for example, was not just about casting a ballot—it was about ensuring Black Americans had a voice in shaping policies that affected their lives. Similarly, DEI initiatives, while imperfect, were a recognition that systemic barriers required systemic solutions.

As DEI programs come under fire, it is essential to ask what comes next. How do we ensure that qualified Black Americans have a fair shot at the American Dream without the tools and frameworks that DEI programs provided?

The SCLC believes that while the outcry over the dismantling of affirmative action and DEI is understandable, it is equally important to recognize the limitations of these programs as they were

National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

previously constructed. “We must continue to press for systemic changes that bring real equality to our communities,” says Liggins. “This fight is about more than programs; it is about ensuring that every Black American has access to the opportunities they deserve.”

Conclusion

The push to eliminate DEI programs marks a pivotal moment in America’s ongoing struggle with race and equality. For Black Americans, the debate underscores a dual reality: while these programs often fell short of their promises, their elimination raises serious concerns about the motives and consequences of such actions.

The SCLC remains committed to advocating for policies that go beyond symbolic gestures, focusing instead on meaningful changes that address the root causes of systemic inequality. The fight for justice and equity continues, and as history has shown, progress is never inevitable—it must be fought for, defended, and expanded upon at every turn.

By putting lives first, we’ve created a legacy that lasts!

For over 130 years, we have tackled some of the world’s biggest health challenges and provided hope in the fight against disease. At Merck, our mission to save and improve lives expands beyond inventing medicines and vaccines. We value diversity and inclusion in all its manifestations and strive to reduce disparities and advance racial, health, social and economic equity for our people, patients and communities.

The story of the Selma to Montgomery marches is often encapsulated by the brutal events of “Bloody Sunday,” when peaceful demonstrators were attacked on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. But the history of this pivotal chapter in the Civil Rights Movement is deeper than that fateful day in March 1965. It is a story of resilience, strategy, and quiet courage—qualities exemplified by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and its tireless efforts in Selma before and after the marches.

Among the many figures who shaped this legacy is Dr. Bernard LaFayette Jr., the current Chairman of the Board for SCLC. Dr. LaFayette began his work in Selma in 1963, laying the foundation for the campaigns that would later change the course of history. Though his contributions are often associated with his earlier involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Dr. LaFayette himself has emphasized that his work in Selma was carried out as an SCLC staff member. He has frequently recounted how he volunteered for the Selma assignment when others hesitated. “The white people were too mean, and the Black people were too afraid,” he explained. Yet, armed with quiet determination and a deep commitment to nonviolence, Dr. LaFayette undertook the challenge of organizing in a town where fear and oppression ran deep.

Dr. LaFayette’s early efforts focused on engaging young people and working with the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) to lead voter registration drives. Despite intimidation and violence from local authorities, LaFayette’s work inspired a new generation of activists in Selma. He trained community members in the principles of nonviolent resistance, helping them to see that they could challenge systemic injustice through courage and collective action. His work laid a critical foundation for the broader Selma Voting Rights Campaign.

By January 2, 1965, the momentum in Selma had reached a tipping point. On that day, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a packed mass meeting at Brown Chapel AME Church, officially kicking off the Selma Voting Rights Campaign. The campaign’s goals were clear: to confront the systemic disenfranchisement of Black citizens in Alabama and to push for federal voting rights legislation. Brown Chapel became a hub for organizing and a symbol of hope for the movement.

While Selma was a focal point, the struggle for voting rights extended beyond its borders. In

neighboring Perry County, SCLC organizer James Orange was arrested, prompting a march in Marion, Alabama, led by Rev. C.T. Vivian. The peaceful protest ended in tragedy when state troopers and local law enforcement brutally attacked the demonstrators. In the chaos, Jimmie Lee Jackson, a young Black man, was shot and killed while trying to protect his mother from an assault.

Jackson’s death galvanized the movement and spurred the idea of a march from Selma to Montgomery. The 54-mile journey would serve as both a protest against violence and a demand for voting rights. Organized by SCLC, the march was a bold and deliberate strategy to draw national attention to the plight of disenfranchised Black citizens in Alabama.

On March 7, 1965, approximately 600 marchers, led by Hosea Williams of SCLC and John Lewis, set out from Selma. They crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge only to be met with unrestrained violence from state troopers and local deputies. The images of marchers being beaten with clubs and teargassed shocked the nation and forced Americans to confront the brutal reality of segregation and voter suppression.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, moved by the events in Selma, addressed a joint session of Congress on March 15, 1965. In his historic speech, he declared, “Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.” His words and leadership paved the way for the introduction of the Voting Rights Act.

Though “Bloody Sunday” is the most well-known event of the Selma campaign, it galvanized the nation, bringing unprecedented attention and support to the Civil Rights Movement. It was not the end of the story. The marchers regrouped and, with the backing of a growing coalition of allies, organized a second march. Under federal protection, they finally completed the journey to Montgomery on March 25, 1965, where Dr. King delivered his iconic “How Long, Not Long” speech on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol. Tragically, during this time, lives were lost in the struggle, including Viola Liuzzo, a white activist from Detroit, and Rev. James Reeb, a Unitarian pastor. Their sacrifices remind us that the fight for equality is one that all Americans share, transcending race and geography. The plight of Black Americans affects the entire nation, and the struggle for justice and equity is a collective responsibility.

The Selma campaign’s immediate impact was the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a landmark piece of legislation that outlawed discriminatory voting practices. President Johnson signed it into law on August 6, 1965, affirming the nation’s commitment to ensuring that all citizens could participate in the democratic process. But the deeper legacy of Selma lies in the example set by individuals like Dr. Bernard LaFayette Jr., Rev. C.T. Vivian, James Orange, and Diane Nash, who demonstrated that transformative change begins with grassroots organizing and the courage to confront fear.

The sacrifices of Viola Liuzzo and Rev. James Reeb highlighted that the struggle for equality is not solely a Black issue but one that affects all Americans. Their willingness

to stand in solidarity underscored the interconnectedness of the fight for justice and the universal desire for human dignity and freedom.

This year, 2025, marks the 60th anniversary of the Selma to Montgomery marches. While we celebrate the achievements of the original march, it is remarkable and sobering that access to voting, the marginalization of Black Americans in wealth, income, and incarceration rates, and the continued quest to ensure everyone has access to the American dream remain as relevant today as they were in 1965.

The work of SCLC in Selma underscores the importance of sustained effort and coalition-building in the fight for justice. From the early voter registration drives to the historic march to Montgomery, the Selma movement was a testament to the power of collective action and the enduring spirit of nonviolence.

Today, as SCLC continues its mission under the leadership of figures like Dr. Bernard LaFayette Jr., the lessons of Selma remain as relevant as ever. The struggle for voting rights and racial justice is far from over, but the courage and determination that defined the Selma campaign offer a powerful blueprint for the road ahead. More than the bloodshed, it is this legacy of hope and resilience that endures.

Readers are encouraged to visit nationalsclc.org to learn about SCLC’s plans for the 60thanniversary commemoration and to sign up for more information on how to support the movement.

SCLC National Magazine/King 2025 Issue

Kaiser Permanente is committed to health care for all. That’s why we work with communities to address the biggest factors that shape people’s health. In pursuit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of equality and to honor our mission, we advance bold, community-led solutions to help keep people healthy and inspire others to put communities at the heart of health. With care teams that reflect the diverse populationswe serve, Kaiser Permanente provides high-quality, affordable care and delivers better health outcomes for all.