On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks’ simple act of bravery helped inspire and lead the Civil Rights Movement. Today, visitors can step back in time and experience the sights and sounds that forever changed our country. Troy University’s Rosa Parks Museum honors one of America’s most beloved women who helped lead by her actions.

For ticket information and hours, visit troy.edu/rosaparks or call 334-241-8615

Honoring 25 years of the Rosa Parks Museum and 70 years of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

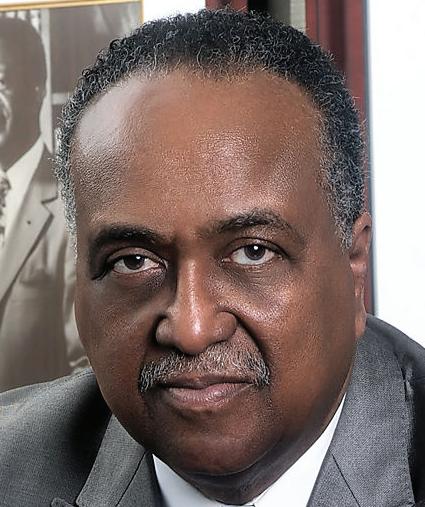

DeMark Liggins, Sr President & CEO

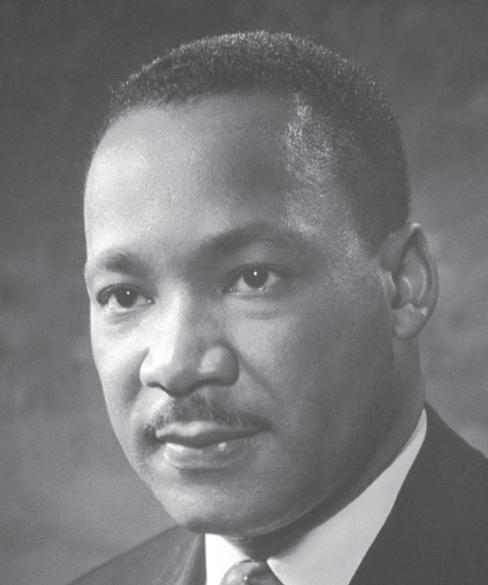

Martin Luther King Jr. Founding President

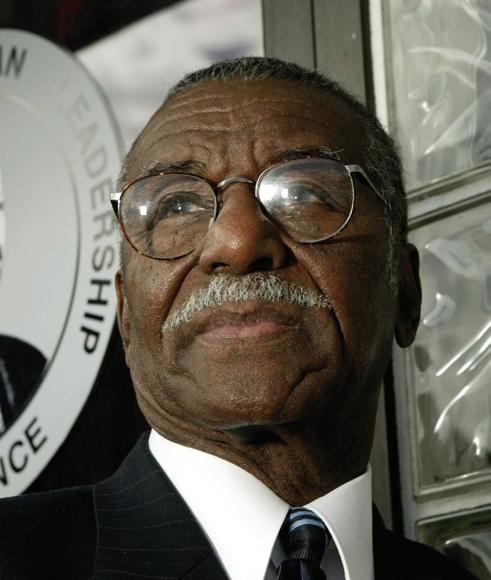

Ralph D. Abernathy President 1968 - 1977

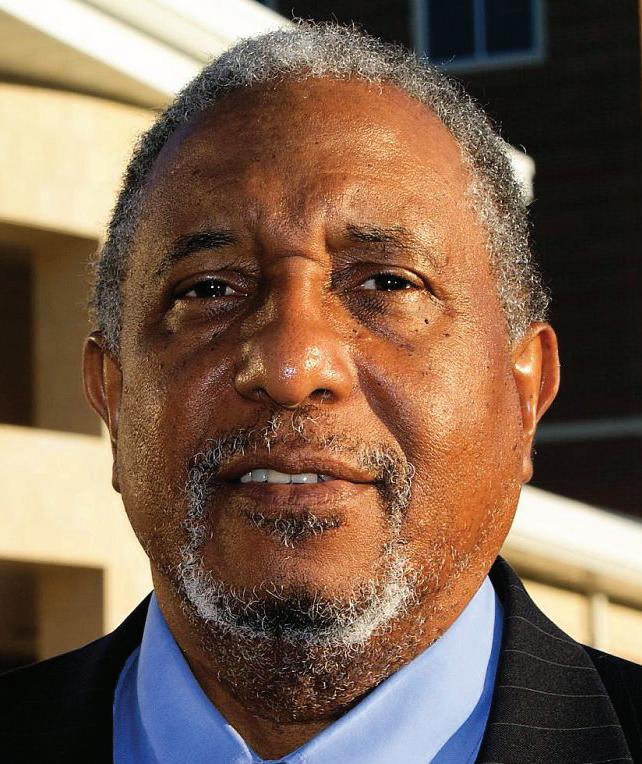

Fred L. Shuttlesworth President 2004

Dr. Bernard LaFayette, Jr Chairman

Joseph E. Lowery President 1977 - 1997

Dr. Charles Steele, Jr. President Emeritus

Martin Luther King III President 1998 - 2003

Howard Creecy Jr. President 2011

By: DeMark Liggins, SCLC National President & CEO

America is in the intensive care unit. That is the theme of this issue, and it is the feeling many of our neighbors carry in their bones. We are watching social norms strain, political norms bend, and values we once took for granted drift out of reach. These are trying times. They are hard times. People ask how a nation that pledged liberty and justice for all could wander so far from the promise that shaped us. I understand the confusion. I also understand the ground truth. At the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, we have always seen the gap between promise and practice. We honor the dream, but we live with the reality that too many have never been invited to taste it.

America’s beauty has never been only her power. It has been her promise. That promise is a moral idea that every person should have a fair shot at life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I do not pretend that this promise has been delivered equally or consistently. The communities we serve can testify that it has not. Yet the promise still calls us forward. It is the north star that keeps a free people from becoming a fearful people. And it is why SCLC stands where it has always stood. We stand in the space between what is and what ought to be, with our feet planted and our hands open, building bridges that others say cannot be built.

If America is in the intensive care unit, our task is not to argue over who gets the last word in the waiting room. Our task is to fight for the patient. That means defending the institutions that allow us to disagree in the first place. Free speech is not a luxury for peaceful times. It is a safeguard for difficult times. A free press is not our enemy when it exposes what we would rather hide. The right to vote is not a favor extended by the powerful. It is the foundation on which consent is built. Courts that can say no to the loudest person in the room are not obstacles to progress. They are the guardrails that keep power from swallowing the people it is meant to serve.

I am not naive about the moment. There is anger in the streets and anxiety at the kitchen table. There is an industry built on outrage that knows how to monetize division. But I refuse to accept the idea that we are helpless. We are not. We have tools in our hands that our parents and grandparents used when the country felt off its

axis. They organized. They voted. They testified. They built institutions that outlasted one election and one new cycle. They prayed with discipline. They loved with conviction. Love, as we say often at SCLC, is a verb. It is not soft. It is not sentimental. It is a decision to act for the good of our neighbor even when it costs us something.

Leadership in this hour will not be measured by who can deliver the sharpest line. It will be measured by who can deliver the most people from despair into duty. Legacy will not be a museum word. It will be the living story of ordinary people who choose service over cynicism. And love will not be a slogan. It will be the daily work of meeting need with presence, truth with courage, and conflict with a commitment to human dignity. This is our lane. This is our calling.

So what do we do right now, while the monitors are chirping and the diagnosis seems bleak? We tighten our focus. We protect the vote. We insist on transparency from those who wield authority. We invest in young leaders who can carry this work farther than we can take it. We link arms with the faithful in every tradition who still believe that compassion is stronger than contempt. We show up at school board meetings and city councils and state houses, and we make the case for the common good with clarity and respect. We organize our chapters to serve and to advocate, not one or the other, but both.

I will not promise quick relief. I will promise faithful work. SCLC was born for seasons like this, not because we enjoy the storm, but because we were trained to stand in it. When the headlines tempt us to despair, we will remember our why. We fight because the promise is worth the struggle. We fight because our children deserve a country that keeps its word. We fight because our faith teaches that love rejoices with the truth.

If America is in the intensive care unit, then let us be the family that refuses to leave the bedside. Let us be the people who steady the hands of the nurses, who speak life when the room falls silent, and who plan for the day the patient walks again. The promise is still the promise. Our work is to make it visible.

DeMark Liggins, Sr. President and CEO Southern Christian Leadership Conference

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

Chairman’s Corner

Written By: Dr. Bernard Lafayette , Chairman of the Board

Violence has been lauded as the supreme solution and consistently has been excused as acceptable behavior for human beings. The tentacles of violence stretch into almost every aspect of our lives: our homes, work places, recreation, sports and music, just to mention a few. Even children’s toys and television programs express our unconscious acceptance and clear admiration for violence, reinforced by our educational and corporate systems, technical processes and institutional patterns. In almost every aspect of our lives, we have been trained to respond to conflict with violence.

In recent history, nonviolence has come to be recognized as a significant alternative for groups, communities, and whole societies to effectively deal with the conditions they face locally, nationally, and internationally. Previously, interest in nonviolence and its practice has been oriented to the theories and philosophies of particular personalities, alternative life-style groups, or small religious communities, such as the three “historic peace churches.”

During the 20th century, the successful social movements of Gandhi in India and King in the United States led to the public’s realization of completely new dimensions of nonviolent conflict reconciliation. This approach depends not on major material or technological instruments, but utilizes skills and methodologies. Nonviolence is positive, powerful, and effective because it calls forth the very best in human spirituality and intelligence from the people or groups that use it. The Six Principles of Kingian Nonviolence provide the foundation of values for nonviolence. The Six Steps outline the methodology.

Martin Luther King, Jr. made a tremendous contribution to the application of nonviolence on a broad scale in our society. Because his philosophy and methods were so effective in transforming long-held values and discriminatory social conditions, and because he based his response to repression and violence on his faith and conviction that violence was not a valid means of solving social problems, Dr. King’s life stands today as one of the greatest moral forces in history. We can recognize the impact of his continuing legacy when we see Eastern Europeans, South Africans, Asians, Middle Easterners and South Americans singing “We Shall Overcome” in countless native languages and applying his methods of nonviolence.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

In reflecting on his own experiences, Dr. King was impressed not by the strength and accomplishments of the masses, but by the capacity of a small group committed to nonviolence to create positive change when faced by large problems. In 1967 during a staff conference he said, “Now is the time to really educate and train people in nonviolence as the more noble path to social justice.” He emphasized education, enlightenment, and leadership development in every facet of his work and the campaigns he led. Significantly, the new leadership of his movement has continued to expand and extend his concept of nonviolence making it more accessible to today’s leaders.

Private and public sponsorship of studies and research about nonviolent movements and their methods of conflict reconciliation have helped to establish nonviolence as a legitimate multidisciplinary body of knowledge from which succeeding generations can learn how to address the issues of violent conflict and achieve their desires for a just peace. It has long been established that people of all ages and in all social or political settings can learn and exercise nonviolent methods, concepts and skills. By institutionalizing such training and education, society as a whole can begin to change. The policies in the boardrooms and in the halls of government, attitudes on our playgrounds and in our homes, and the selection of music on the airwaves can change positively. While the world has seen the results of Kingian nonviolence conflict reconciliation, too few have had the opportunity to study and understand its principles and methods.

Training a substantial number of people in the use of nonviolence, provides for better alternatives to violence for resolving conflicts. The goal of nonviolent conflict reconciliation is justice, a win/ win solution rather than a win/lose situation. The nonviolent approach reduces both the financial and human costs in managing conflicts. It may be the only approach where a party to a conflict is rewarded for teaching the opponent how to master his or her weapon. Nonviolent solutions not only preserve the dignity of conflicting parties, but also elevate the relationship between the opponents to one of cooperation and understanding, in which they jointly implement change and celebrate victory.

If we could but calculate the devastating tragedy and human destruction due to violence, it would be enough to warrant a study of Dr. King’s methods and philosophy. The loss of productivity, creativity, and vital resources from organizations, and communities is immeasurable. Dr. King’s campaigns and movements covered only fifteen years in this century but answer an emphatic “yes” to the question of whether we can end the senseless cycle of violence and foster positive social growth in the lives of our people and our institutions. In order to appreciate the significance of the King era, we must understand the knowledge, information, and experiences of those who were part of Dr. King’s campaigns. We need to appreciate what changed, how it came about, and what did not change.

Much of what has been written about Dr. King’s work overlooked many important issues and developments, but recently we have seen examples of fresh hope for a more extensive analysis of the dynamics and factors that contributed to King’s success. While we should not underestimate the conditions of repression and violence, especially in current economic and political institutions, we must remember that we’ve also learned that these conditions can be overcome through nonviolent action.

There are many myths about nonviolence that require an immediate response that nonviolence is peaceful and passive; that it is the opposite of violence; that it can only be used effectively by people with a long spiritual tradition living in democracy; or that it is simply a range of the techniques of demonstration, direct action, and confrontation. Nonviolence is aggressive and assertive toward changing the institutionalized policies, practices and conditions that deny people their full dignity as human beings. The word

violent derived from the Latin for force—violare (violate)—to treat with force—violentus (violent)— vehemence. Violation of their integrity, dignity, and self-respect through the exercise of stronger physical, psychological or economic forces without regard to them as human beings. The opposite of this violence is not nonviolence but a seemingly peaceful status quo that tolerates the brutal and sometimes subtle victimization of people. Nonviolence resists; it challenges the peaceful nature of unjust conditions. Martin Luther King, Jr. was arrested more for being a troublemaker and for disturbing the peace than on any other charge. Socrates was convicted for stirring up doubt in the minds of youth toward the status quo. Nonviolence comes from a long tradition of disturbing the peace and challenging contemporary conditions.

Nonviolence also analyzes conflict differently from the simplistic “we vs. them” or “good vs. evil” polarities that have been characteristic of our culture. It’s an approach to conflict that seeks to understand the factors underlying the problem and to create an effective strategy by which to address them—a strategy based upon universal values deeply rooted in all the great religious traditions. The Six Principles that we began discussing last time are the foundation of Dr. King’s philosophy. These principles outline a perspective that is important to nonviolent analysis of violent and unjust conditions. Likewise, the Six Steps of Kingian Nonviolence provide a strategy for application. These steps are not arbitrary nor linear, but are coterminous, and need to be understood separately along with how they interact over the course of a movement. Finally, they’re a set of concepts for understanding the dynamics of conflict, leadership education, organizational life, action research and tools that the practitioner can use. These topics make a significant contribution to a clearer understanding of Dr. King’s philosophy and what we can learn from the movements he led.

Something is shifting in how we talk about and act on healthcare in this country. For years, we’ve debated costs, coverage, and systems. But lately, there’s a deeper change, one that should alarm anyone who believes in kindness and shared responsibility. Increasingly, we’re drifting away from a healthcare system rooted in compassion and moving toward a cold, Darwinian approach where only the strong, the lucky, or the financially secure get to thrive, and everyone else is left to fend for themselves.

This isn’t just a policy trend. It’s a moral one. And it raises the question: What kind of society do we want to be?

You may not hear the word Darwinism thrown around in healthcare policy discussions, but the signs are there. Decisions are being made that prioritize economic output over human need. The value of a person seems increasingly tied to their ability to pay, work, or contribute in narrowly defined ways. If you can’t afford a doctor, if you’re too sick to work, if you’re elderly, disabled, or struggling with mental illness, well, good luck. The safety nets are fraying, and in some places, they’re being intentionally dismantled.

This shift reflects a mindset where people are expected to pull themselves up by their bootstraps even when they don’t have boots. It’s a system that quietly suggests that if you’re suffering, you’ve somehow failed. That mindset has no place in a society that calls itself civilized.

Healthcare isn’t just about bodies. It’s about values. When we decide who gets access to care and who doesn’t, we’re making a statement about what and who we care about. Lately, that statement has been damning. We’re seeing policies that make it harder for people to qualify for Medicaid, proposals to slash funding for community health clinics, and efforts to roll back protections for people with preexisting conditions.

These decisions don’t come from nowhere. They come from a growing cultural cynicism, one that sees care as a transaction, not a moral imperative. One that treats illness as weakness and poverty as a personal failure. One that encourages us to stop loving each other.

Yes, loving. That’s the word we need to bring back into the conversation. Love isn’t just for family dinners and holiday cards. Love is how we build a society worth living in. Love is why we check on our neighbors, why we bring soup to the sick, and yes, why we fund healthcare for people we’ll never meet. Because we care. Or at least, we used to.

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

There’s a reason the Southern Christian Leadership Conference named love as one of its core tenets. Love isn’t passive. Love is a verb. It is revealed by our actions, not our intentions. What we do reflects what we love. If we build systems that exclude people in need, that’s not just a policy failure. It’s a failure of love.

Let’s talk about what happens when we take love out of healthcare. We get disparities that are wide and worsening. Black and Brown communities bear the brunt of chronic underinvestment and lack of access. Rural hospitals shut down, forcing people to drive hours for basic care. Mental health and addiction services are cut to the bone. Families ration insulin. People die of treatable diseases.

This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening now. And it reflects who we are becoming.

When we allow our healthcare system to operate without empathy, it becomes a machine that chews up the vulnerable. It rewards the healthy and punishes the sick. It saves the wealthy and sacrifices the poor. And that’s not just inefficient. It’s inhumane.

What if we flipped the script? What if we measured our healthcare system not by profits or efficiency but by how well it takes care of those most in need? What if we made compassion, not cost cutting, our guiding principle?

A truly loving healthcare system would ensure that no one goes without care because of their income, background, or condition. It would recognize that we’re all better off when everyone is cared for. It would treat health not as a luxury but as a shared investment. Because when people are healthy, communities are stronger, families are more stable, and yes, economies even do better.

We have models for this. Other countries have built healthcare systems grounded in the belief that health is a human right. And here at home, there are community clinics, public health initiatives, and mutual aid networks doing heroic work, often on shoestring budgets, to bring love back into the system. But they can’t do it alone. Compassion must be built into the structure, not left to chance.

The push to make healthcare more exclusive, more conditional, more transactional is not just wrongheaded. It’s cruel. And it’s time we said so.

When politicians propose cuts to Medicaid, that’s not just a budget line. It’s a decision that will harm real people, children, seniors, people with disabilities. When insurers deny coverage, when hospitals close in low income areas, when mental health is treated as an afterthought, these are choices that reflect values.

And if we don’t speak up, those values become the norm.

It’s not enough to quietly hope things improve. We need to be loud about the kind of healthcare system we believe in. One that reflects not Darwin’s survival of the fittest but the golden rule. One that says we’re all worthy of care just because we’re human.

Here’s the truth we don’t hear enough: love can be a guiding principle for policy. It can shape the way we design programs, allocate resources, and measure success. A loving society invests in public health, not just private profits. It builds systems that are inclusive, not exclusive. It doesn’t ask, what’s the least we can do, but what’s the most good we can do?

We already do this in other parts of our lives. We care for our families without asking if they’ve earned it. We look out for friends in need. We instinctively offer support in times of crisis. Why should healthcare be any different?

We need to bring that same energy to the national level. We need leaders who aren’t afraid to say that love belongs in politics, that empathy is strength, not weakness. That public services aren’t handouts, they’re expressions of our collective values.

This isn’t just a healthcare debate. It’s a reflection of who we are as a country. Are we a place where people are left to sink or swim based on their circumstances? Or are we a place where people look out for each other, especially in times of need?

We don’t have to accept a future where care is only for the fortunate. We can demand a system that sees every life as equally worthy. But to do that, we have to speak the language of love loudly, persistently, and unapologetically.

It starts with telling the truth that the move away from compassion in healthcare is a move away from who we claim to be. And it ends with a commitment to each other, to our communities, and to the idea that a truly great society is one where no one is abandoned.

Because in the end, healthcare is not just about medicine. It’s about love. And love should never be optional.

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

We believe in equal opportunity for all regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, or ethnic background.

Harley Ellis Devereaux

Johnson Lexus

In a functioning republic, power does not flow in one direction. It circulates, challenged, checked, and constantly justified in the open. But lately, some of the pillars meant to hold up that system are bending under quiet pressure. Free speech is being tightened in both public and private forums. The executive branch stretches its reach while Congress shrinks from hard votes. And far too often, loyalty to party outweighs loyalty to the Constitution.

The signs are clear. Rules that carry the weight of law but never face a recorded vote. Emergencies that never expire. Congressional oversight that flares up only when the cameras are on. Court decisions more focused on outcomes than on clearly reasoned limits. Newsrooms and social platforms quick to silence rather than correct. Universities and companies that punish dissent not because it is wrong, but because it is unpopular.

What we are watching is not politics as usual. It is a shift away from the framework that gives a republic its legitimacy: the consent of the governed. That consent does not come from polling or partisanship. It comes from laws passed in daylight, speech protected even when uncomfortable, and institutions that stay within their lane.

Free speech is where this work begins. It is not a luxury or an accessory. It is the mechanism through which society corrects itself. A nation that cannot tolerate dissent is one that cannot admit mistakes or improve. Whistleblowers, investigative journalists, community activists, none of them survive without space to speak freely. When public debate is narrowed by government pressure, private censorship, or social cost, the body politic goes numb. People stop speaking not because they agree, but because they fear the consequences of disagreement.

The response to reckless speech is not silence. It is more speech, better arguments, clearer evidence, public rebuttal. That is the democratic way, to let ideas compete in the open rather than die in the dark.

But freedom of expression does not mean much if power consolidates elsewhere. The Constitution was not designed for speed. It was designed for restraint. The president is not meant to make laws by proclamation. Congress is not meant to dodge accountability by letting agencies or executive orders carry the burden of governing. Courts are not meant to rewrite statutes with deference so extreme it blurs the lines between interpretation and legislation.

A government that governs by emergency without deadlines, without votes, without review is not acting in the spirit of the republic. It is managing the country by convenience. And convenience, while tempting, is a terrible civic compass.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

This is not a theoretical concern. It is happening across administrations and party lines. Presidents act when Congress will not, and lawmakers cheer them on so long as the policy aligns with their side. But if a tactic would be condemned under one party, it must be condemned under the other. The Constitution does not care about campaign colors. The oath of office is not conditional on who holds power.

Congress still has tools if it chooses to use them. It can write specific time limited laws rather than delegating endlessly. It can hold oversight hearings that seek truth rather than viral moments. It can subpoena documents, confirm officials who respect constitutional boundaries, and shine sunlight on how money is spent. These are not revolutionary acts. They are acts of responsibility.

Likewise, the courts have a role, not as saviors but as stabilizers. Judicial review should be rooted in constitutional text, structural principles, and historical precedent. Deference to executive agencies is sometimes necessary, but it cannot erase the line between enforcing the law and making it. When courts speak, they should do so in plain, persuasive language. Legal reasoning is not just for lawyers. It is for citizens too.

Still, no republic runs on government alone. Civil society carries the culture that politics reflects. Churches, labor unions, universities, student groups, nonprofits, businesses, all of them shape what is acceptable and what is not. They can defend space for lawful speech, share information transparently, and model disagreement without destruction. They can refuse the ease of ideological purity tests and online mobs. They can reject the instinct to exile those who simply disagree.

None of this is glamorous work. It is not the kind of stuff that trends on social media or wins elections in thirty second clips. But it is what keeps the foundation solid.

What does real strength look like in a time like this? It is a senator voting to limit a president from their own party because the process matters more than the win. It is a president choosing to send a bill to Congress rather than twisting an executive order past its breaking point. It is a court drawing a narrow but principled line and explaining why. It is a citizen defending the speech rights of someone they oppose, because tomorrow those rights may protect someone they love.

If there is one value at risk in this moment, it is consent. Not just the formal act of voting, but the deeper idea that the people rule through transparent lawmaking, open debate, and shared limits on power. The Constitution

does not promise efficiency. It promises liberty through structure. That is not always easy to defend, especially when expedience offers short term wins. But those wins fade. The damage to civic trust does not.

In the end, the question is not whether the republic is in crisis. The question is whether citizens and leaders are still willing to do the patient work of maintaining it. That work is not dramatic. It is a daily habit. Protecting free speech. Keeping power divided. Demanding real consent, not just passive compliance. None of that will make headlines, but it might just keep the republic alive.

Let others chase the next partisan victory. The better task, the lasting one, is to hold the line on principle. Not because it is easy. But because without it, we forget what the republic was for in the first place.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

By: Kevin Kimble, SCLC Global Policy Initiave

According to a research report from 2017, Black wealth is projected to decline to zero by 2053. Despite narratives of progress and claims that America is now “post-racial,” current data on wealth, education, contracting, and legal decisions make clear that discrimination against Black Americans is more deeply rooted and more systemically unaddressed than perhaps ever before. The Supreme Court’s recent rulings effectively require that racial disparities be zero for America to count as post-racial. By that standard, Black exclusion indicates we are far from post-racial in the U.S.

The stark wealth gap is one of the most damning markers. In Atlanta, for example, the median income for white households stands at about $83,722, versus $28,105 for Black households. But income is just part of the equation: white families hold 46 times more wealth than Black families, approximately $238,355 vs. $5,180 (it was 60 times during slavery, so basically no change in almost 200 years of “freedom”). In Boston, the difference is $8 for Black families, compared to $250,000 for the average white family (source). According to a recent report, White wealth in New Jersey has doubled from approximately $300,000 to $640,000 (source), making the wealth gap $662,000 versus $20,000. New Jersey’s median household income for white families is $110,100, compared to $68,000 for Black families. These are discrepancies that haven’t occurred by mistake in some of the wealthiest states in the U.S.

Throughout history, nearly all the robber barons built a portion of their vast wealth through taxpayer-funded government contracts. The most successful modern-day businesses are no different.

It’s no surprise that Government contracting reveals one of the starkest forms of inequality when comparing how many Black contractors are available versus how many receive actual contract dollars. The numbers show that even when Black contractors are qualified and ready to bid, the share of funds they receive is almost nonexistent.

In New Jersey, the 2024 disparity study conducted by Mason Tillman Associates found that Blackowned construction firms represented approximately 9.19 percent of all available construction

businesses. Yet, despite their presence in the market, these firms received only 0.14 percent of the dollars awarded on construction contracts valued between $65,000 and $5,710,000 (source). This level of underutilization translates into tens of millions of dollars in lost opportunities and demonstrates the starkness of the exclusion when measured against availability.

In Connecticut, a disparity study covering the period from 2017 to 2021 similarly showed that Black-owned construction firms were present in the vendor pool but captured only 0.3 percent of all state contracting dollars during that time (source). When measured against their availability in the marketplace, this utilization figure is not only low but also effectively negligible, revealing a contracting system that fails to deliver opportunities proportionate to participation.

In Minnesota, the statewide disparity study (2016–2023) found that although Black American contractors made up 9.7 percent of the qualified pool, their actual utilization was recorded at only 1.7 percent of contract dollars (source). In other words, Black-owned firms captured less than two percent of available dollars in markets where they represented almost 10 percent of the supply. This gap, repeated across prime and subcontracting opportunities, makes clear that utilization for Black firms is nowhere near reflective of their readiness and qualifications.

These levels of under-utilization indicate near-total exclusion. When Black contractors make up between five and ten percent of available firms in a given sector, but consistently receive less than one percent of contracting dollars, the disparity cannot be explained away by chance or by performance factors alone. Instead, it highlights systemic barriers in bidding, access, certification, information, bonding, or other gatekeeping mechanisms that disproportionately affect Black-owned firms.

Legal Decisions & the “Post-Racial” Definition

Recent Supreme Court decisions have pulled back the tools available to counteract these disparities. The Court has increasingly endorsed a vision of equal protection that mandates colorblind law, even in a society with deeply unequal starting points.

In Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard / UNC (2023), the Court held that the race-based admissions policies of Harvard and UNC “cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause” because they: “lack sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful endpoints.”

Justice Sotomayor, dissenting, warned: “Ignoring race will not equalize a society that is racially unequal. What was true in the 1860s, and again in 1954, is true today: Equality requires acknowledgment of inequality.”

In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), Chief Justice Roberts likewise justified striking down the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance protections by writing that “our country has changed.” Ignoring that voter suppression and gerrymandering persist, disproportionately burdening Black Americans.

National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

These decisions don’t just concern education or voting, they redefine the legal standard. If America is “post-racial,” then racial disparities must already be eradicated. The law now treats raceconscious remedies as suspect, regardless of data showing entrenched inequality.

By the Court’s reasoning, to be “post-racial” means that disparities in wealth, contracts, education, and political access are acceptable. That people in the Black community do not deserve to share in the wealth of this nation or the wealth-building tools of government contracts and home ownership.

However, the factors limiting equal access to wealth-building tools are worsening significantly. Educational opportunity is narrowed as affirmative action is struck down. Therefore, if Black students cannot gain admission to Ivy League colleges, not because they lack the test scores, knowledge, or intelligence, but rather they are labeled unqualified because they lack a legacy admission guarantee, or they are not a good “culture fit”. Also, voting rights enforcement has been gutted, limiting their ability to have proper representation in Congress. So the suppression continues.

By any empirical standard, this is exclusion, not parity.

Comparison to the Emancipation Era

It is sobering to note that in 1865, Black Americans began with essentially no wealth. Today, despite decades of supposed progress, the ratios of wealth and opportunity remain closer to those original deficits than to equality.

In NJ, for instance, nearly one in ten construction businesses is Black-owned, yet virtually none of the contract dollars flow to them. That is not “progress” but structural exclusion. The disparities mirror those typical of the Jim Crow era, only now cloaked by a legal doctrine of colorblindness.

Structural Discrimination is Legally Unaddressed and has been exacerbated by recent legal rulings

Discrimination against Black Americans today is higher in the sense that: It is baked into wealth inequality, inaccessible capital, and contracting systems. Legal tools for redress (affirmative action, preclearance, race-conscious contracting goals) are being dismantled.

Courts demand proof of certain absolute disparity before remedies are allowed, an impossible standard that ensures continued exclusion.

Declaring America “post-racial” while the data show vast racial gaps is not equality. It is denial. The persistence of disparities in wealth, contracts, education, and voting power proves that discrimination remains as entrenched as ever, arguably higher in effect because law and policy are increasingly blind to it.

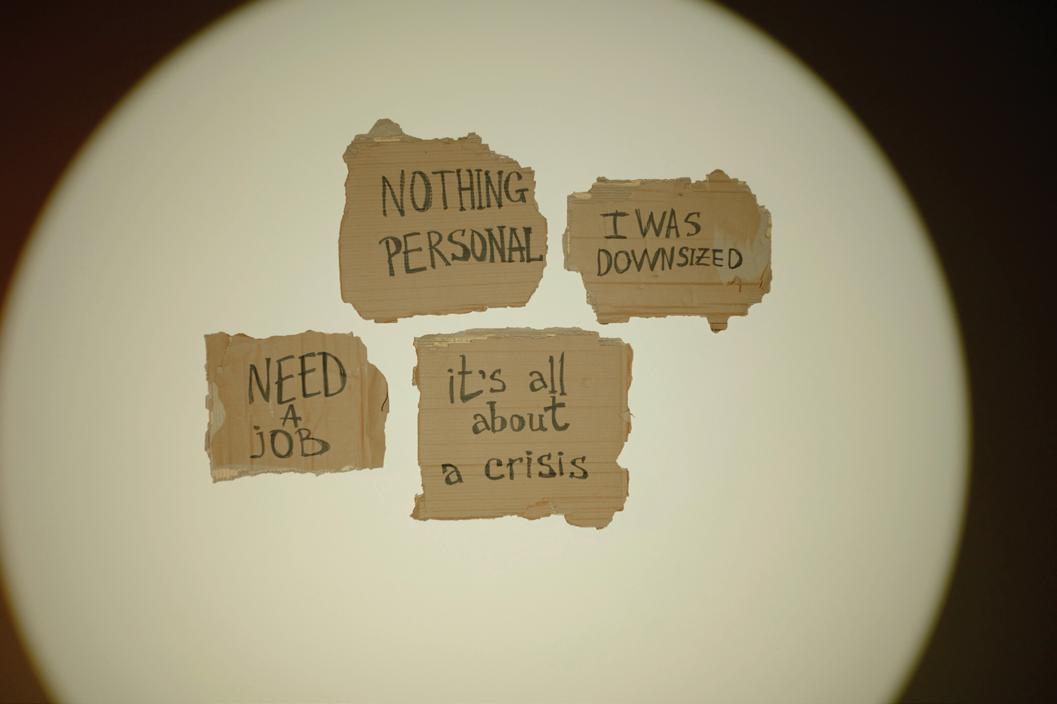

The unspoken cost of cutting DEI and what it means for Black women

In this current wave of economic “recalibration,” companies and government agencies are rolling out layoffs, budget cuts, and restructures under the guise of efficiency and fiscal responsibility. But look closer at who is being let go, whose departments are being downsized, and whose leadership roles are evaporating, and a clear pattern starts to emerge. Though rarely stated outright, the brunt of these decisions is landing squarely on the shoulders of Black women.

Let’s be honest: the rollback of DEI efforts is not just a symbolic loss. It is a material one. Real jobs, real income, real access to healthcare, wealth building opportunities, and leadership seats are disappearing. And in many sectors, especially within corporate spaces and the public sector, those losses are disproportionately affecting Black women. We are not talking theory. We are talking data, paychecks, and livelihoods.

During the racial justice reckonings of 2020, corporations pledged billions of dollars toward DEI. Chief Diversity Officers were hired at a record pace. ERGs were expanded. Companies created pipelines for underrepresented talent. For a brief moment, it felt like we were turning a corner. But that momentum has stalled. And as soon as the economy started to wobble, DEI was quietly moved to the chopping block.

Now, in 2025, we are seeing the full effects. DEI departments are being dismantled. Black led initiatives are “sunsetting.” Roles that were hard won after years of advocacy and proof of performance are being eliminated, often without replacement.

And here is what rarely gets said: Black women disproportionately held many of those roles. From program managers in DEI offices to communications leads on equity projects, to HR specialists, policy analysts, and social impact strategists, Black women were not just participants in this work, they were the architects. When the jobs go, it is not just a professional setback. It is a structural unraveling of hard fought progress.

This is not about centering gender at the expense of race. It is about understanding the layered, specific ways Black women are positioned in the workforce. According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Black women are overrepresented in public sector jobs, nonprofit roles, and administrative leadership, precisely the sectors most vulnerable to current cutbacks. These are also spaces where DEI investments were initially concentrated.

What happens when those jobs disappear? Communities lose more than income. They lose access points. Black women have long served as bridges in professional environments, connecting policy with community

impact, pushing organizations toward inclusion, and holding the line on equity even when it’s inconvenient.

And we cannot afford to pretend this is just an individual challenge. It is a community crisis. When Black women lose employment and mobility, entire ecosystems suffer. Families lose providers. Local economies lose spending power. Churches, schools, and grassroots initiatives lose volunteers and donors. The economic impact spreads wide and deep

. Still, these losses often go unspoken. Partly because they are masked under neutral sounding corporate speak: “realignment,” “streamlining,” “budget discipline.” But also because there is a social tendency to downplay the specific experiences of Black women in favor of broader racial or gender narratives. That silence is dangerous.

We can acknowledge the toll on Black women without diminishing the struggles of others. In fact, we must. Equity work requires specificity. And pragmatism. If we are serious about building resilient, inclusive communities, we have to look at where the cracks are forming and who is falling through them first.

This is not just about corporate America, either. Government agencies are undergoing their own purges. In recent years, many public facing DEI roles were filled by Black women: city equity officers, school district diversity leads, health equity liaisons. As state legislatures across the country target DEI programs, those jobs are vanishing too. And once again, Black women are taking the hit. This is not a coincidence. It is a pattern. And patterns tell stories. They tell us whose labor was valued conditionally, whose expertise was seen as trendy rather than essential, and whose presence was tolerated more than it was welcomed.

In the workplace, Black women are often tasked with doing the emotional labor of inclusion, educating colleagues, mediating culture clashes, mentoring others, all while navigating bias and under recognition. When budgets tighten, that work does not disappear. It just stops being supported. It becomes invisible, unpaid, and even more exhausting. We need to talk about this out loud.

Not because Black women need saving. But because we deserve strategy. Community strategy. Political strategy. Economic strategy. If we know where the hits are landing, we can plan better responses.

That means creating spaces to share job leads, pool resources, and sustain networks. It means advocating for equity not just in hiring but in retention and advancement. It means demanding transparency from employers and holding them accountable for the equity they promised. It also means adjusting our internal narratives. For many of us, achievement has always been armor. We were taught that if we worked twice as hard, followed the rules, and outperformed everyone in the room, we would be safe. But these layoffs have reminded us that performance alone does not guarantee protection. Especially not when the systems were never built with our security in mind. So where does that leave us?

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

It leaves us needing each other. Now more than ever. Not for inspiration or hashtags. But for survival. For collective intelligence. For building our own infrastructures that do not disappear when the market shifts.

Black women have always been economic anchors in our communities. That truth remains. But anchoring does not mean absorbing all the weight alone. It means we need policy advocates, corporate insiders, nonprofit leaders, and small business owners aligned and coordinated. We need to ask harder questions of our employers. Of our elected officials. Of the institutions that say they serve us.

And we need to get honest within our community, too. About the fact that gender does shape how race plays out in the workplace. About the fact that Black women’s economic security is not just a women’s issue, it is a community stability issue. It affects everyone: children, elders, partners, neighborhoods.

This does not mean Black men are doing fine. It means we need nuance. We need enough analytical depth to hold multiple truths at once. Yes, the racial wealth gap hurts all Black people. And yes, within that gap, Black women are being uniquely squeezed by the rollback of DEI. Pragmatism means we do not wait for someone else to say it. We say it ourselves. We prepare. We shift strategies. We organize.

Because the headwinds are not slowing down. But neither are we.

While this piece focuses on the rollback of DEI and its disproportionate impact on Black women, it is also important to clarify that SCLC is not advancing a defense of DEI as its institutional position. Rather, we continue to push forward with our Qualified Merit-Based Councils (QMCs); a longstanding practice of identifying talent from within our communities and creating clear, credible pipelines into opportunity. Whether through partnerships with employers, universities, or unions, we have always believed in the capacity of our people and the necessity of institutions recognizing and investing in that capacity. DEI may be in retreat in many sectors, but our commitment to channeling excellence from the communities we serve has never depended on trending terms rather it has always been rooted in proven, generational truth.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids are sweeping through communities with increasing force and fading accountability. These are not routine actions. They are calculated demonstrations of unchecked state power, carried out in secrecy and confusion, often without warrants or legal justification. Though the stated purpose is immigration enforcement, what is actually taking shape is something broader and more dangerous; a system in which power can operate without oversight, where suspicion becomes guilt, and where due process is treated as optional.

For many in Black, Brown, immigrant, and low income communities, the threat of criminalization has never been theoretical. It is part of daily life. People are treated as suspects not for what they have done, but for how they look, where they live, or whether they can afford legal representation. The current wave of ICE activity intensifies this reality, deepening long standing injustice under the cover of law.

There is no argument against enforcing the law when the target is a clear and credible threat to public safety. But that is not what these raids have become. Time and again, ICE operations have focused not on individuals a community considers dangerous, but on workers, caretakers, parents, and neighbors: people who contribute, not harm. These raids are carried out in homes, in schools, in hospitals, and in shelters. They target people who are not hiding, but living in the open, trying to build lives with dignity. These are not criminals. These are community members.

What should concern us all is not only who is being taken, but how. Agents arrive in unmarked vehicles. They often present no valid warrants. They refuse to identify themselves or wear anything clearly linking them to a legitimate law enforcement agency. People are removed without explanation. Families are left in the dark. Legal counsel is delayed or denied. These are not isolated events. This is now routine.

But there is a deeper danger to this normalization of secrecy. The more government agencies operate behind masks, without insignia, and in the shadows, the more they invite others to do the same. When law enforcement abandons transparency, it creates the perfect cover for actual criminals. What is to stop someone from dressing in camouflage, putting on a tactical vest, claiming to be ICE, and pulling someone out of a car or home?

If officers do not have to identify themselves, if they are not required to present documentation, if their vehicles are unmarked and their actions unchecked, how can an ordinary person tell the difference between the state and someone impersonating it? From armed robbery to kidnapping and worse, this opens a terrifying path. It is not just a civil rights issue. It is a public safety crisis. And we are already seeing the consequences.

No federal agency should be allowed to operate without transparency. No enforcement action in someone’s home or in a public space should happen without oversight. A government that acts without answering to its people is not upholding justice. It is exercising unchecked control.

And what starts with the most vulnerable rarely stays there. This is a pattern we have seen before. Powers created to target one group are often reused, repurposed, and redirected. Surveillance programs once aimed at immigrant communities have been used on journalists and activists. Policing strategies designed for neighborhoods of color have spread into wider civilian life. Raids that begin in silence end up defining how the state handles dissent, protest, and resistance more broadly.

We must be clear: this is not about enforcing laws. This is about normalizing fear as a tool of governance. These raids are designed to make people disappear, to leave children wondering where their parents went, to keep neighbors from asking questions. That fear is not incidental. It is central to the strategy.

When fear becomes policy, it destroys trust. Families stop reporting crimes. Workers avoid medical care. Parents fear sending children to school. Entire communities go quiet, not because they are guilty, but because they do not feel safe. And when communities go quiet, democracy begins to erode.

What is lost in this moment is not only freedom, but legitimacy. These raids do not make people safer. They destabilize families, disrupt workplaces, and weaken the very fabric of civic life. They do not build trust in government. They destroy it. And they do not reflect the values that Americans across political lines claim to believe in—equal treatment under the law, fairness, and limits on state power.

There is a role for enforcement. But it must be focused on those who pose legitimate threats, not people simply trying to survive. It must be public, not secretive. It must be governed by law, not by convenience or political pressure. And it must respect the basic rights that protect all of us, not just the privileged few.

We do not need raids on workers in the early morning. We do not need agents in schools or clinics. We do not need families torn apart without warning or cause. What we need is an approach to immigration and public safety that honors the dignity of every person and the constitutional limits of state power.

If ICE is to function at all, it must operate within a transparent and accountable framework. Communities must have a voice in defining public safety. Legal standards must be upheld at every stage. The use of force must be the last resort, not the first. Enforcement should reflect the actual needs and concerns of the communities affected. not just the priorities of political agendas.

To say nothing is to allow these practices to become permanent. Every time we accept secrecy, every time we excuse abuse of power, we shift the baseline of what is considered normal. That is how rights disappear, not overnight, but through quiet acceptance. Silence, in the face of this kind of harm, is never neutral.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. warned, “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

Ending racial injustice requires all of us to work together and take real action. What can you do to help?

Educate yourself about the history of American racism, privilege and what it means to be anti-racist. Educate yourself about the history of American racism, privilege and what it means to be anti-racist.

Commit to actions that challenge injustice and make everyone feel like they belong, such as challenging biased or racist language when you hear it.

Vote in national and local elections to ensure your elected officials share your vision of public safety.

Donate to organizations, campaigns and initiatives who are committed to racial justice.

Visit lovehasnolabels.com/fightforfreedom

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

Redlining has not disappeared. It has evolved.

Where banks once used red ink to wall off Black communities from opportunity, today the dividing lines are written in code. They are not on maps. They are buried in algorithms. These systems are hidden from view but they determine who gets a mortgage, a job interview, a student loan, or even a driver on a rideshare app.

This is digital redlining. And it is happening right now.

Every day, as we use our phones, browse the internet, or make purchases, data is being collected about us. That data builds a profile—where we live, what we read, how we speak, who we associate with, how often we move, and what we search for. Companies claim this helps deliver better service. In truth, it is used to rank and sort us.

If your zip code has fewer high-value transactions or if it is majority Black, you may be flagged as a financial risk. If your language patterns differ from the dominant norm, you may be filtered out of job opportunities. If your digital signature resembles that of people previously denied credit, you may face the same outcome. No notice. No explanation. No appeal.

These decisions are made by machines. But the machines are built by people. The data reflects society as it is—not as it should be.

Algorithms do not need to know your race to discriminate. They use proxies: income, neighborhood, education level, browser history, social media use, phone model. Each one is connected to patterns of inequality that stretch back generations. The result is familiar. Black families and communities are steered away from opportunity, not based on merit but on data shaped by past exclusion.

This is not just an individual issue. It is structural. And it is growing.

Lending models now determine where banks invest. Often, Black neighborhoods are overlooked not because they present more risk, but because they show less profitable activity in the data. That activity is a reflection of historic disinvestment. The system reads it as a reason to continue the pattern.

In education, students are being flagged by software systems for absenteeism, test performance, and behavior. These systems do not ask why a student missed school or how discipline is applied. They only look at the numbers. A label applied in elementary school can follow a student for years. That label can influence placement, expectations, and opportunity.

In hiring, automated filters screen resumes before any human review. If your name, formatting, or educational background

does not match the model’s expectations, you are removed from the pool. If the model was trained on biased hiring data, that bias becomes permanent. You may never know why you were not considered.

This is redlining without visible lines. It is hard to detect and harder to confront.

Surveillance adds another layer. Devices now monitor more than activity. They track behavior, location, speech, habits, even biometric data. These tools are present in homes, schools, workplaces, and vehicles. The information is stored, shared, and sold. It feeds into predictive models and marketing systems. In some cases, it is used by government agencies.

Law enforcement uses facial recognition software that misidentifies Black faces at disproportionate rates. Immigration agencies track mobile phone data without requiring court orders. Public benefit systems use predictive tools to assess eligibility, compliance, or risk. The public rarely sees how these systems work. The companies that build them protect their code as proprietary. Government agencies often avoid scrutiny by using third-party vendors.

This is not just about privacy. It is about influence, control, and access.

The danger is not only exclusion from services but the quiet expansion of surveillance infrastructure. With enough data, systems can predict behavior, detect patterns, and shape outcomes. The line between convenience and control is growing thin.

These systems function without transparency. And without transparency, there is no accountability.

We at the SCLC believe that any technology used to make life-determining decisions must be subject to public oversight. Data must be accessible. Records must be correctable. Algorithms must be open to review.

Technology is not neutral. It reflects the values and structures of the society that creates it. Without active resistance, it will continue to mirror inequality rather than correct it.

This is not a future problem. It is already here.

The red lines have not been erased. They have been rewritten in code, buried in platforms, embedded in devices, and protected by secrecy. We are not standing on the sidelines. We are standing in the way of the red line. And we are not moving.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

In 2026 the Southern Leadership Conference will reintroduce one of its most essential leadership tools: the Chapter Leadership and Development training. Following a period of organizational reflection and strategic assessment the return of this initiative marks an important milestone for chapters national leadership and the broader SCLC network.

This training is not new. It has long served as a foundational element of chapter development and internal leadership infrastructure. Its renewed focus however reflects a deeper understanding of the role chapters play in sustaining the movement not through high profile events or public platforms but through the everyday decisions planning and coordination that preserve long term capacity.

This is not programming designed for public visibility. It is programming built for the daily and often unseen responsibilities that give movements their staying power: internal operations alignment strategic governance and grounded leadership.

The visible work of social change including protests rallies and public actions remains vital. These expressions of resistance and vision play a critical role in the fight for justice. But they rest on a base of logistical and administrative effort that is far less visible. Coordinating volunteers developing programs ensuring compliance maintaining records budgeting resources these actions receive little public attention but they are indispensable.

The Chapter Leadership and Development training is structured around this reality. Its purpose is to support chapter leaders in strengthening their internal systems and equipping their teams to meet the operational demands of sustained organizing. It prioritizes discipline structure and clarity as core components of effective movement leadership.

As President DeMark Liggins Sr. notes “Leadership is one of the three pillars that hold up who we are as SCLC. It is not just about leading a chant or being the face of a protest. Leadership is about what happens when the cameras are off. When capacity is being built when programs are being planned when risk is being managed and when communities are being strengthened. That is what this training is about giving our chapters the tools and knowledge to lead with integrity clarity and impact.”

This understanding of leadership is not centered on visibility but on responsibility. It emphasizes structure over spectacle and long term service over momentary recognition.

As SCLC approaches its seventieth year it continues to operate within an evolving legal civic and social landscape. The conditions that shaped the organization’s early work have shifted and new legal and operational standards have emerged for nonprofit and civic organizations.

In recognition of this changing environment SCLC has entered a two year period of internal review and structural realignment. Throughout 2025 and 2026 the national office is engaging in a comprehensive examination of its policies bylaws and chapter protocols to ensure they are legally sound mission aligned and operationally sustainable.

The Chapter Leadership and Development training will serve as one of the primary platforms for this work. Chapter representatives will be invited to review and engage with updates to organizational policy discuss necessary risk mitigation strategies and contribute to the creation of a consistent national operating framework.

The goal of this realignment is not increased centralization. It is increased clarity greater accountability across the organization and stronger cohesion between the national office and its chapters. Through shared protocols SCLC aims to prevent internal disorganization minimize liability and improve the consistency of its work across all regions.

This alignment is ultimately intended to create greater freedom for chapters to focus on what matters most: delivering programming and advocacy within communities in ways that are informed coordinated and resilient.

New Orleans holds a unique place in SCLC’s institutional memory. It was in New Orleans on February 14 1957 that the organization first emerged. Nearly seven decades later the city continues to shape SCLC’s identity and vision.

In 2026 SCLC will return to New Orleans to host the Chapter Leadership and Development training. The event will take place on Saturday February 14 aligning intentionally with what SCLC refers to as Emergence Day. This gathering is more than symbolic. It offers a reflective moment to return to foundational values while planning the next phase of national chapter development.

The training will bring together representatives from chapters across the country for workshops policy briefings leadership sessions and facilitated discussion. The program will emphasize the need for strategic alignment while recognizing and supporting the human relationships that continue to drive this work.

The updated training will cover a range of core leadership and operational topics including

- Internal leadership development and team structure

- Program planning and evaluation

- Compliance with legal and ethical standards

- Risk management and financial stewardship

- Alignment with national bylaws and chapter protocols

- Best practices in chapter operations and governance

- Tools for strengthening community based program impact

The content is grounded in real scenarios and guided by the lived experience of chapters. Training materials are being developed in coordination with legal advisors governance specialists and

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

longtime SCLC organizers. The approach emphasizes both practical implementation and mission driven integrity.

Participants will leave the training with usable materials ready to apply policies and a stronger understanding of their chapter’s role in the broader organizational landscape.

We congratulate the SCLC’s efforts to improve world peace and equality for all.

www.fnf.com

Effective organizing requires more than passion. It requires systems that can support growth withstand scrutiny and adapt to changing conditions. One of the most persistent misconceptions in grassroots organizing is the belief that structure inhibits creativity. In practice clarity and structure allow for greater flexibility more efficient operations and stronger community relationships.

The Chapter Leadership and Development training is not designed to constrain chapter energy. It is designed to support it. By establishing clear expectations and providing shared resources SCLC seeks to ensure that every chapter has the tools necessary to thrive in an increasingly complex and demanding environment.

This investment in structure is not a departure from grassroots values. It is a commitment to them.

SCLC is entering a phase defined by reflection reinvestment and operational readiness. The organization is building the internal capacity required to sustain its public commitments and deepen its presence in the communities it serves.

Chapters will continue to play a central role in this work. By equipping chapter leaders with the tools necessary to navigate compliance structure teams and build sustainable programs the national office reaffirms its commitment to a movement that is not only passionate but well governed and strategically prepared.

Additional information including registration instructions and travel logistics will be made available through the national SCLC website. A save the date and sign up form is also included in this issue.

On February 14 2026 SCLC returns to New Orleans not simply to celebrate its past but to prepare for the future. The work of organizing continues. The responsibility of leadership deepens.

Rev. Dr. Levon A. LeBan, President Southern Christian Leadership Conference, New Orleans Chapter

Considering actions that dismantle the 1965 Voting Rights Act – that adversely impact unserved and underserved citizens, enhanced voter ID laws, the limitation, reduction, or elimination of early and absentee voting, purging of voting rolls, and removing neighborhood voting locations suggests that the “right to vote is rapidly becoming the fight to vote!”

The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. noted: “So long as I do not firmly and irrevocably possess the right to vote, I do not possess myself.” Further, “I cannot live as a democratic citizen, observing the laws I have helped to enact – I can only submit to the edict of others.” Due in no small part to the efforts of Dr. King, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and others, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965. The Voting Rights Act finally gave millions of African Americans the most fundamental right in a self-governing society—the right to vote. However, in recent years, states have passed laws restricting access to ballot boxes and silencing the voices of communities of color, voters with disabilities, young people, and other historically underrepresented groups. The United States has a history of contentious challenges and changes to voting rights for its citizens. What minority citizens are experiencing today is hardly a twenty-first-century phenomenon. Entrenched subsets or groups of those in power have long tried to keep “the vote”out of the hands of the less powerful. The right to vote in America has long been antagonistic, while voting represents the fundamental core of democracy. Following the Articles of Confederation, in 1787, the country “ordain(ed) and establish(ed)” the Constitution for the United States of America. Interestingly, the framers of the Constitution did not mention that citizens have the “right to vote.”

The American “experiment” in democracy began in the late 1700s by granting [ask yourself, who were the “grantors”] the right to vote to a narrow subset of society. This subset excluded women, indigenous or Native Americans, Americans of African descent, Americans of Asian descent, Latinos or Hispanics, along with indentured servants and bondsmen. In the South, states began to erect new barriers to voting, such as poll taxes and an assortment of literacy tests– specifically designed to inhibit the vote of black and brown people. Organized efforts to end various restrictions to voting – for indentured servants and bondsmen - were subsequently mounted as early as 1792 when New Hampshire became the first state to remove its landowning requirement.In 1828, the State of Maryland permitted members of the Jewish faith to enter the ballot booth. Later, in 1856, North Carolina was the last state to drop property demands for white men.

SCLC National Magazine/ Convention 2025 Issue

By the 1860s, white males largely enjoyed universal suffrage in the United States. On September 22, 1862, following the victory at the Battle of Antietam in Sharpsburg, Maryland, President Lincoln signed “Executive Order Number 95” (more popularly known as the Emancipation Proclamation), ordering the emancipation of all slaves in states that were in rebellion and did not return to the Union by January 1, 1863. President Lincoln’s plan to reintegrate the Confederate sympathizers back into the Union was outlined in the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. However, his successor, President Andrew Johnson, vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment, granting former slaves and free African Americans full citizenship [known as the Reconstruction Amendment, the 14 th Amendment was ratified by Congress on July 28, 1868]. In 1870, two years after the ratification of the 14 th Amendment, the 15 th Amendment was adopted, granting African American men the right to vote. It was not until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, nearly one hundred years after the Civil War, that state and local restrictions were outlawed. At the federal level, South Carolina, Mississippi, and Alabama led the way with the number of African Americans serving as Representatives in Congress during Reconstruction. Two men from Mississippi, Blanche K. Bruce and Hiram Revels, served in the United States Senate. Louisiana led the way with three elected Lieutenant Governors: Oscar James Dunn, a gubernatorial candidate; P.B.S. Pinchback; and Caesar Carpentier Antoine, of whom one was briefly elevated to the Office of Governor of Louisiana – the Honorable Pickney Benton Stewart Pinchback.

Today, SCLC Chapters across the country are actively involved in voter engagement, registration, education, mobilization, and participation. We are at a point in America where the U.S. government must legislate, regulate, and promote uniform voting guidelines through Constitutional Amendments. This would result in the equitable “leveling off” of voter laws and procedures. Election laws in California will be the same as in New York – from sea to shining sea. The guidelines relating to when you can register to vote before elections would also be the same. In some cases, citizens can register on the day of an election, while in other places, registration must be completed thirty days before the election.

Dr. King asserted: “The denial of this sacred right is a tragic betrayal of the highest mandates of our democratic tradition. And so, our most urgent request to the President of the United States and every member of Congress is to give us the right to vote.” Exercising the right to vote is the great equalizer of citizenship; both millionaires and the impoverished are equal in the ballot booth. It’s often said: “A voteless people is a hopeless people and your vote is your voice!” Always remember, “vote as if your life depended on it!”

The news never lets up. Every day brings a new headline, a new policy shift, another round of decisions from this administration that carry real consequences. On television, on phones, and across social media, the cycle spins faster and louder, pulling us into constant reaction. It is easy to feel overwhelmed. Easy to feel like everything that matters is happening far away and out of reach.

But here is the truth. No matter what is happening in Washington, people across the country still face the same challenges. Families still need food. Children still need safe places to learn. Elders still need care. Communities still need repair. That is where the work begins—not in the national conversation, but in the daily lives of people who refuse to wait for change.

Across the country, people are stepping forward to meet local needs directly. They are creating food programs, launching shared aid efforts, opening free health clinics, running youth activities, and providing legal support to neighbors who are being left behind. These are not isolated acts of kindness. They are practical responses to a national reality that often ignores the communities most affected. In many places, these solutions are being led or supported by SCLC chapters and new student units that understand something essential. The most powerful response to an unjust system is to build something better in its place.

Leadership is not about waiting for the right moment. It is about acting in the moment you are given. That is one of SCLC’s founding principles. Leadership means ownership. It means recognizing that while we may not control what is done to us, we are always responsible for how we respond. It means stepping forward not as bystanders, but as builders.

This is why SCLC is renewing its commitment to chapter growth. Because when people come together to organize, they do more than survive. They create structure, relationships, and new possibilities. Our power is not only in how we protest. It is in what we build. We do not wait to be saved. We start literacy classes. We create mentorship programs. We clean up streets. We offer childcare, organize voter outreach, start community learning centers, and make sure no one around us is going through hardship alone.

This work is happening everywhere. In cities and small towns, on campuses and in rural communities, in the South, the Midwest, along both coasts, and in all the places in between. People are not waiting for perfect conditions. They are using what they have and doing what they can. One student unit turns a classroom into a weekend tutoring space. A community group sets up a supply exchange so neighbors can access household goods. A chapter makes weekly phone calls to elders. Another group organizes rides to the polls. These actions may not make national headlines, but they change lives. And they make a simple truth clear: we are not powerless.

When we say there is power in the people, we are not using a slogan. We are describing what it looks like when people come together to meet real needs. That power becomes visible in the systems we build, the support we provide, and the time we offer to one another. The solutions we need will not come from the top. They will grow from the ground.

This is what grassroots resilience looks like. It does not depend on permission. It does not wait for a green light. It begins when people decide to take responsibility for each other. It begins with the question, What can we create right now that makes someone else’s life better? This kind of work is not glamorous. It is steady, it is practical, and it is already underway. It is being led by people who understand that action is more powerful than outrage. That community is more durable than crisis. That hope only matters if it shows up in the work.

There will always be another national headline. There will always be more delays, more distractions, and more decisions made without our consent. But we do not need to lose ourselves in that noise. We can stay focused on what we build together. On what we protect. On what we pass on to the next generation.

We do not need to control the national stage in order to control what happens around us. What we need is commitment, courage, and community. That is how movements grow. That is how real change happens. Be the change you seek!