POPART WOMEN BETWEEN US AND THEM: IDENTITY IN EASTERN EUROPEAN POP ART

Editor’s note: “PopFem” magazine is honored to invite you to the exhibition Women Between Us And Them: Identity In Eastern European Pop Art. By delving into the stories of female Pop artists in Eastern Europe, you will become aware of how gender is a social construct that crosses the borders of art. Color, Pop Art and much more await you inside. You just have to use your ticket. We hope you enjoy it.

“The accepted story of Pop Art, as in many modernist tales, is one of male subjects and female objects” (Minioudaki, 2007, p.402).

In the inspiring canvas of Pop Art, women, as objects of representation and as artists, emerge as one of the cornerstones of this artistic movement. However, analyzing the role of women in this field means going beyond mere aesthetic representation, introducing a whole range of possibilities that intermingle the concepts of identity, ideology and political narrative. Within the latter, women become the epicenter of “us” and “them”, and Pop Art becomes the mirror that will reflect the cultural complexities of an entire era.

The exhibition Women Between

Us And Them: Identity In Eastern European Pop Art will focus on unraveling the mysteries hidden by Pop Art in Eastern Europe (compared to the rest of the Western world), in relation to women, both in their role as a creator, as well as in her role as a representative. Starting from the definition of Pop Art and its characteristics, the development of this movement in the Eastern Bloc will be reached, exploring all its nuances. It will investigate how Eastern Pop Art influenced feminine conception, addressing important issues such as feminism, cultural and national

symbology and, derived from this, the tension between local and global identities. Next, the comparison between female and male artists from the East and the West will reveal the dynamics of power and subordination that defined the role of women in this Pop movement. Women artists acquired a different position with respect to the representation of the body, sexuality and femininity, in contrast to the male gaze. Thus, the story of “us” and “them” shaped an entire tradition of reception and criticism that has characterized the role of women and the understanding of Pop Art from a

PAGE| 4

POPFEM

male-dominated perspective.

Finally, the reception and criticism of Pop Art in Eastern Europe will be examined, focusing on how the works of women artists were perceived and valued within this panorama. In that way, this journey will allow to conclude with a reflection on the concept of “us” and “them”, observing how these categories continue to shape the understanding of Pop Art and the role of women. As the art historian Kalliopi Minioudaki stated, the

development of Pop Art has been based on accepting this discourse and looking at women from the eyes of men: “The accepted story of Pop Art, as in many modernist tales, is one of male subjects and female objects” (Minioudaki, 2007, p.402).

PAGE| 5

590123412345768 MAY 2024 TICKET FOR THE EXHIBITION: WOMEN BETWEEN US AND THEM ONE PERSON Ticket valid for this exhibition. You can enjoy the visit as much as you want. We hope you like it.

Entering the world of Pop Art means immersing yourself in an entire universe full of colors, shapes and meanings that challenge traditional roles and break the codes imposed on society. Pop Art meant a before and after in the way of perceiving art and popular culture. But what really is Pop Art? What makes it special? In order to answer these questions, it is necessary to delve into a whole history of origins, manifestations and influences, discovering the essence of this new world.

First of all, it is essential to start with the definition of Pop Art, as an artistic movement that emerged in the United Kingdom around 1950 and later reached the United States. As is known, the end of the Second World War meant a break down in the sphere of the artist, shaping new ideologies and new consumer habits.

Due to this and inspired by the aesthetics of everyday life and the consumer goods of the moment, this artistic movement represented a new window from which to see the world and art itself, a more social and global one, not for a few, but for anyone who would like to look through this renewed vision. In opposition to elitist culture, Pop Art was born as a reaction to established ideals, making use of popular images, isolating them and combining them with a tone of irony and parody. If the origin is treated as such, the movement emerged in the United Kingdom, following the debates raised in the Independent Group, about the new North American culture, in which the romantic solemnity of British art of the forties was questioned.

In response, the promoters of Pop Art made triviality the central theme of this movement, with the desire to

PAGE| 6

Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, Hamilton

escape from classist art, an art that reduces the creative capacity of the artist and prevents representing the world as one really wishes to do so. Under Duchamp’s motto, that art should be intelligent, pop artists addressed banal themes, but from sophisticated aesthetic means, demanding an absence of prejudices, both on the part of the artists and on the part of the audience themselves. The director of the Valencian Institute of Modern Art, Consuelo Císcar, has defined Pop Art as: “An eminently citizen art, born in large cities, and completely alien to Nature. [...] It uses known images with a different meaning to achieve an aesthetic stance” (Císcar, 2009, cited by Busselo, 2021, p.9). In short, in a single sentence: Pop Art seeks to extract art from certain cultural spheres and transpose it into daily life.

PAGE| 7

Representation of popular culture and mass culture: as mentioned, the themes seek to escape from grandiloquence and, therefore, focus on elements of everyday life, such as advertisements, daily consumer products, comics, celebrities of the moment and common objects.

Use of iconic images: Pop artists select iconic and recognizable images from popular culture, in order to transform them into works of art. For example, Marilyn Monroe or Elvis Presley have been some of the best-known protagonists, represented by pop artists.

Visual style: breaking the mold and underlining the desire to be different, Pop Art is characterized by its striking and colorful visual style, with bright colors that catch the viewer’s attention, applied with printing and screen printing techniques.

PAGE| 8

Marilyn Monroe, Andy Warhol

Whaam!, Roy Lichtenstein

Intersection with advertising: Pop Art intersects with advertising and often includes it, taking inspiration and making use of advertising elements, such as slogans or brand logos.

Depersonalization: objects and themes are portrayed with a certain superficiality, since art stops imitating life and it is life that begins to imitate art. Thus, this movement tends to depersonalize the images and objects represented, eliminating individual characteristics, with the purpose, once again, of showing the uniformity of mass culture.

Irony and social criticism: although Pop Art celebrates popular culture, it also has an ironic and critical component, questioning the values and norms of consumer society. However, criticism usually comes in a subtle or underlying way.

Repetition and seriality: another technique usually used by pop painters is the repetition of elements. Often, the works are configured through the repetition of the same image or theme, with the aim of emphasizing the repetitive nature of mass culture and the mass production of this new way of seeing the world.

PAGE| 9

Marilyn Diptych, Andy Warhol

Campbell’s soup cans, Andy Warhol

Woman in the shower, Roy Lichtenstein

After analyzing the emergence and general characteristics of Pop Art, it can be said that the meaning of this movement lies in the ability to challenge and subvert the conventions of traditional art. The images and objects of consumer society are the point that marks the distinction between high and low culture, between “us” (pop artists) and “them” (high culture), democratizing the form of consuming art and broadening the perspective, managing to capture the criticism and contradictions of the era of consumerism and globalization. Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein in the United States or Richard Hamilton in the United Kingdom are some of the most important figures who managed to embody the essence of pop language. As Hamilton stated: “The art of tomorrow will be popular, designed for the masses: ephemeral, with short-term solutions, expendable, easily forgettable; low cost, mass produced; young, aimed at youth; witty; sexy; gimmicky; glamorous; a big business” (Richard Hamilton, 1957, cited by Busselo, 2021, p.11).

PAGE| 10

Woman crying, Roy Lichtenstein

Pop Art as an artistic movement, born in the United Kingdom, subsequently spread to other parts of the world, not only to the United States. One of the main pop centers has been Eastern Europe, where this movement acquired particular nuances, defined by the political, social and cultural context of the region, after the Second World War. The countries of Eastern Europe, under the Soviet regime, were subject to a whole set of censorship policies that maintained control of art production, promoting socialist realism, as the official art form of the Soviet Union. Socialist realism was an artistic movement, whose purpose was to expand class consciousness and knowledge of social problems, which meant that any piece that came out of these canons was contested by the regime. For this reason, many artists worked under the pressure of underground, turning Pop Art into a form of cultural resistance and a way of constructing their own artistic identity. Through the iconography belonging to popular culture, the techniques and characteristics seen in the previous section, Pop Art became the means to question the socialist ideal, the influence of consumerism and mass culture.

However, despite descending from the same root, it is essential to establish the distinction between Western and Eastern European artists. Unlike the West, the “them”, the artists of the East, the “us”, used pop language to show the flow of their national identities and to spread messages with political connotations, criticizing the unfulfilled promises of the regime, under aspirations of modernity

and freedom. Eastern European Pop Art reflected the tension between communist ideology and Western mass culture, embodying the tensions between East and West and resorting to a constant struggle of identities. Artists such as Jerzy Zieliński, in Poland; Ion Grigorescu, in Romania; and Gyula Konkoly, in Hungary, used Pop Art to subvert the official narrative. While it is true, within this entire context, Pop Art in Eastern Europe had a significant impact both locally and internationally. So much so, that the reception of these works was seen from a perspective of resistance and rebellion against the regime and established norms, creating a new way of understanding and representing contemporary reality.

PAGE| 11

At the coast, Gyula Konkoly

Having established a general definition of Pop Art and a brief introduction to this movement in Eastern Europe, it is time to continue with one of the main aspects of this artistic trend: the narrative of “them” and “us”. As has been observed, this duality is not shown from a single perspective, but rather adapts depending on who is the issuer of the artistic work. Until now, the contrast between “them” and “us” has been used as a way of personifying the distinction between high and low culture, and between East and West. Nonetheless, there is still another link in this chain of Pop Art that completes this narrative: female representation. As mentioned at the beginning, the main objective of this work is to unravel the mysteries that cover the figure of women in Pop Art, seen from the perspective of female artists, the “us”, and from that of male artists, the “them”. Yet, before studying these contrasts, it is necessary to explore the relationship between Pop Art and women.

Women, as symbolic figures, have played a crucial role in the construction and deconstruction of new visions within Pop Art in Eastern Europe. Becoming national and cultural symbols, female images have reflected the tensions between local and global identities. Likewise, the objectification of the female body and the exploration of femininity are also key aspects in this opposition between “them” and “us”. Therefore, the fundamental purpose is to analyze how Pop Art in Eastern Europe has contributed to the narratives of identity, gender and roles, making the representation of women an element that would challenge cultural and political regulations.

PAGE| 12

As the feminist movement and its various waves gained prominence in the United States during the 1960s, changes in the relationship between Pop Art and women artists began to bear fruit in Eastern Europe. Women used to be stereotyped and conventional objects, and Pop Art could be perceived, in a certain sense, as sexist. Nevertheless, women began to destroy this conception and actively used popular culture to reflect a world dominated by men, as well as increasingly feminine principles that led to: “These women held unique positions in the history of art” (Kidder, 2014, p.7). The women turned their own images into a kind of catalyst to explore personal narrative and social critique. However, the patriarchal disposition of the world has led to the general assumption that women have not had a place in Pop Art. The British art historian, Griselda Pollock, relates: “The nature of the societies in which art is produced has not only been, for example, feudal or capitalist, but patriarchal and sexist” (Griselda Pollock, 2001, p.46).

Because of this, art produced by male artists, even when those represented were women, was included in the canon of traditional Pop Art. Within this echo of tradition, women could only fulfill two roles: housewife or sexual object, in which the female body is only a commodity destined to be consumed. Moreover, it can be said that culture is the social level at which those images of the world and definitions of reality are produced that can legitimize an order of relations of domination and subordination between races and sexes. And in addition to culture, art history deals with this cultural production, challenging the definitions of reality. Accordingly, through Pop Art, women have subverted male roles and narrative, sending messages through popular elements, so that their work is also included in the canon. Why use Pop Art to challenge the world? Because the central figure of this movement is the artist, who sends a message to achieve an effect.

In a similar vein, the main differences between female and male Pop Art in Eastern Europe, and in the artistic movement in general, are based on the way the female body is represented, in how attributes vary widely between male and female artists. Man and woman represented reality, reactions to popular

culture, mass communication and consumerism, but always from a different prism. For example, if you take the exhibition The International Girlie Show, in New York, it compiled works by Marjorie Strider and Rosalyn Drexler, along with important male figures in Pop Art such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein or Mel Ramos, already mentioned above. In it, the difference in looks, the feminine and the masculine, could be clearly observed. In her Green Triptych, Strider fought, through pop language, against misogynistic male attitudes that made the female body a simple object of gaze. In this way, pop art made by women acquired different meanings, including more personal and political aspects. Ultimately, the work of the pop artist is to break structures and give new meanings to the world. Thus, the pop woman tries to destroy this hierarchy and build her own “us”, making use of Pop Art: “The way to construct the subject is through language operations” (Magaña, 2016, p.44).

PAGE| 13

Green Triptych, Marjorie Strider

Within this entire context of Pop Art in the Eastern Bloc, female representation, by women and men authors, acquired a new meaning, associated with national and cultural symbols, since the figure of many women was used to reinforce ideals and question the communist regime. Like that, the woman served to strengthen the second narrative seen, which addressed the contrast between “them” (communism), and “us” (artists). Socialist realism, an official artistic movement promoted by the communist regime, idealizes the working class, in which women played a prominent role. Even so, pop artists in Eastern Europe challenged this representation, including all kinds of pop elements, such as bright colors or repetitions, contrasting with the seriousness of socialist realism. This representation challenged official propaganda by introducing a pop aesthetic, pointing out the discrepancy between reality and the idealization of communism.

Additionally, women were also protagonists in criticizing the elements of popular culture, questioning gender roles and the influence of consumer culture in socialist society. For example, the Polish artist Natalia LL, in her series of images Consumer Art (1972), used the image of women sensually eating food to criticize the gaze of consumer society. In it, the woman becomes the object of the manipulation of advertising and the influence of Western culture in Eastern European society, changing her role in the stream of a national identity. If the consumer society is increasingly alive, how is true identity maintained? In short, the representations of women in Eastern Pop Art served as a means to question the ideals of the communist regime, but also to criticize the extension of popular culture in socialist society, opening a new door to explore the existing relationship between the regime and the popular culture that Pop Art represented.

PAGE| 14

In relation to the previous point, the introduction of Western popular culture in Eastern Europe meant tension between local and global identities which, of course, influenced the representation of women within the dynamics of Pop Art. On many occasions, this perspective was approached from hybridity, exploring cultural influences, and highlighting the tension between the local (the communist) and the global (the world of popular culture). In this sense, many artists, such as the Polish Ewa Partum, offered, through her work Change (1974), a criticism of consumerism and globalization, and a defense of individuality, through feminine beauty. With this work and showing various versions of herself, Partum makes a plea against the pressure to conform to the global ideals promoted by both communist and Western society. In that manner, she questions each and every one of the gender norms imposed, largely due to globalization. When the feminine ideal of globalization that Partum tries

to contrast is mentioned, reference is made to feminine canons represented by North American authors such as Lichtenstein and his work Woman Crying (1965), in which a stereotype of a blonde woman is observed, with a penetrating gaze, and a fleshy and hypnotic mouth. Therefore, taking both perspectives into account, it can be said that the tension between the flow of identities also has women as protagonists, since they navigated between the cultural differences that construct their identity in a context of social and cultural change.

Another of the fundamental themes, within the context of Pop Art in Eastern Europe, is the representation of the female body and femininity itself. From the objectification to the redefinition of femininity, Eastern artists used their works to question the complexities of the female experience in a context of constant political and social change: “Everyone becomes objects of purchase and sale, including the subjects themselves” (Morales, 2018). Yet, the objective of this point lies not only in analyzing pop works, but in comparing how female artists and how male artists represented the female body, addressing and challenging objectification. While some chose to perpetuate these representations, others explored femininity in a more complex way, from a nuanced perspective. Likewise, it will be interesting to study how the British and American counterparts also offered their vision of the feminine world. How do perspectives on femininity compare in different contexts and from different genders? To answer this question, the diversity of voices and experiences in the Eastern European and global art scene must be analyzed, revealing the dynamics of power, identity and resistance: “The body is a device that lends itself to multiple readings. While some interpretations seem to preserve the male gaze of female objectification, others break with all tradition, and make us think about a paradigm shift with respect to gender and categories” (Plaza, 2019, p.39).

PAGE| 16

As already mentioned, female artists have played a fundamental role in exploring and subverting traditions regarding femininity and the body, since in these cases: “The body will appear converted into a place of experimentation and of subversion to deconstruct the normative gender” (Plaza, 2019, p.23). The essence of the woman in the painting, in the work, is presented as a voice and as an image that does not respond to traditional parameters, but rather has a very characteristic way of expressing herself, through a transgressive discourse. Pop Art has allowed artists to denounce sexual and political submission to patriarchy, challenging the very construct of so-called “gender”. As the American philosopher, Judith Butler, stated, gender is performative, in the sense that it

is not expressed through actions, but rather it is a social construction, a performance that produces an illusion that a gender exists. Consequently, pop artists subvert the norms of this supposed gender, using the body as a means of expression, through performative acts: “Performativity is not a single act, but rather a repetition and a ritual that achieves its effect through its naturalization in the context of a body, understood, to a certain extent, as a culturally sustained temporal duration” (Butler, 1990, p.15, cited by Plaza, 2019, p.24). In order to explore it in detail, at this point female artists from Eastern Europe will be studied, along with specific works, to see how they approached the representation of the female body and how they expressed their identity.

PAGE| 17

Jana Želibská: Born in Bratislava, this artist belonged to the progressive generation of conceptual artists, reframing the inspiration of Pop Art. Unique in her generation, Želibská addressed the intimate relationships between men and women and celebrated the female body from a feminist perspective. One of her main works is Som Dom (1967), in which, with a provocative and subversive approach, the artist represents a woman painted on the wall, with pink tones and flowers in the area of the vagina. This challenging and striking representation of the female body evokes the relationship between femininity, sexuality and public space. The body, painted on that wall, becomes an extension of the architecture, an extension of the urban environment. With it, the artist intends to claim the space that corresponds to her as a woman and as a painter in the public sphere.

Dóra Maurer: Born in Budapest, she is a Hungarian visual artist, with more than 50 years of career, who worked on an art full of complex systems. Her objective was to show options to the viewer, so that he could do whatever he considered with them. Her work József and Heléna (1979) explores the relationship between two individuals, a man and a woman, in order to study and question gender duality. Both appear painted as shadows, since the bodies are black spots, symbolizing the universality of the human experience, the ephemeral identity of human relationships, the fluidity of gender and the impermanence of the social. So, Maurer challenges traditional gender conventions, questioning the hierarchy of power between men and women and showing them both as mere shadows. She offers the viewer a renewed and abstract vision that transcends the limitations imposed by the objectification of the female body.

PAGE| 18

Sanja Iveković: Born in Zagreb, she is a photographer, performer and sculptor, dedicated to the representation of topics such as female identity in relation to the media and consumerism. Her work Tragedy of Venus (1975) shows a photograph of a woman holding a pearl necklace in her hand, creating a collage with the repetition of the image. Thus, the meaning of the work could be considered to be the exploration of the objectification of the female body and the consideration of women as an object in mass society. The necklace, a symbol of femininity and elegance, becomes an object of rejection, a sign of oppression and control when placed on the female neck. In this way, the author questions the expectations imposed socially and culturally on women, claiming how, on many occasions, society reduces us to a mere physical appearance. The use of repetition, as already seen, symbolizes alienation, lack of individuality and interchangeability.

Marina Abramović: Born in Serbia, she is an artist dedicated to performance art. Her paintings match some of the characteristics of Pop Art, in which she explores the limits of the body and the relationship of women with society. One of her most striking works in this feminist dynamic is Art Must Be Beautiful, Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975), a film directed by her. In this one, she is the protagonist, depicted aggressively combing her hair repeatedly. With it, Abramović criticizes the expectations of beauty and the objectification imposed on women, subverting the norms of Pop Art and art in general. Instead of creating a simple work, with the use of repetition, the artist prioritizes personal expression and emotional experience over a superficial aesthetic of mass culture.

PAGE| 19

Eva Kmentová: Born in Prague, Kmentová was a Czech visual artist and sculptor, known for her innovative approach and her exploration of feminine and organic forms in sculpture. Figure (1971) is one of her most emblematic creations, since, with a distinctive style, she evokes the figure of a woman, capturing the essence of the body, without resorting to a realistic representation. The simplification of the forms suggests an exploration of the essence and energy of the female body, in relation to the space that surrounds the human being. The author shows a non-canonical, fleshy body, claiming the variety of voices and experiences and challenging her own canons.

PAGE| 20

Zofia Kulik: Born in Wrocław, Kulik is an artist who combines art and a feminist perspective, in order to explore and redefine the limits of femininity. A little further away from Pop Art, in her series Splendor of Myself (1997), she carries out a multifaceted exploration of female identity and empowerment, with a narrative that questions all traditional expectations of the body. The author portrays herself with all kinds of symbolic and ornamental elements, creating a surreal world and playing with the idea of selfrepresentation. Like this, Kulik invites the viewer to reflect on the power of the female body, on the power of women and on the complexity of the female experience in the world.

PAGE| 21

Once the pop artists from Eastern Europe have been studied, it is time to compare them with some from the United States and the United Kingdom. As has already been seen, although both groups address the female body and identity, they do so from different perspectives, because the cultural and social context they lived in was not the same. While some lived in a society influenced by popular culture, others were under a communist regime. For this reason, the artistic approaches presented are different, since some are influenced by the symbols of mass society and others are influenced by censorship and restrictions imposed by authoritarian regimes. However, although the messages and the way they are sent are not the same, the underlying purpose is: to vindicate femininity and the female body as something that belongs to women and not to society.

Pauline Boty: Born in London, Booty is an English feminist artist, founder of British Pop Art and the only woman in this movement in the United Kingdom. All of her paintings and collages demonstrate the importance of femininity and sexuality, implicitly expressing a criticism of the male-dominated world. One of her most emblematic works is Sunflower Woman (1963), in which a naked woman is represented, with her body covered with different drawings, like a collage: a sunflower on her belly; a man with a gun on his chest; a woman screaming in the legs; an explosion; an owl, etc. With soft curves and in a sensual posture, the author wants to emphasize femininity and female empowerment. Yet, all the drawings that paint her body invite us to reflect on the female experience in the world, full of complexities and conflicts. The sunflower could represent motherhood; the man with the gun and the woman screaming could be violence and suffering; the explosion could be chaos; and the owl could be the insight. Thus, this multifaceted narrative about the human condition and individual experiences creates a collage that displays ideas and emotions about female identity.

PAGE| 22

Marisol Escobar: Born in France, but of Venezuelan descent, Escobar is a sculptor who contributed enormously to the pop movement, with her satirical sculptures inspired by everyday life. The Party (1966) represents female figures in the scene of a party or social event. Each figure is individually sculpted, with distinctive details in their facial expressions, so each one is different. Because of that, these figures offer a unique look at the female experience in social situations, exploring their role in public space. Subtly, the author criticizes the social construction of gender and the roles of male and female sex, how women are subject to different norms, compared to men.

Rosalyn Drexler: Born in New York, she is a visual artist characterized by her pop works, which evoke deep themes related to mass culture and surreal elements. Marilyn Pursued by Death (1963) is one of those provocative works, with multiple meanings. Marilyn Monroe appears being pursued by death, combining celebrity with a dark touch. In the characteristic line of Pop Art, the famous figure becomes the protagonist, along, in this case, with death, suggesting the fragility of human life, even for cultural icons. Likewise, Monroe’s presence also gives food for thought about femininity in popular culture. Her image has been the object of admiration and study, but also of criticism about gender roles and social expectations imposed on women. Hence, it can be said that the relationship between Monroe and death not only represents the fragility of human life, but also the vulnerability of women in society stalked by men and by all types of social canons.

PAGE| 23

The construction of “us”, of the female body seen from a feminist perspective, has been the work of female pop artists. Nonetheless, the other part of the equation, the “them”, remains in the hands of male artists, who have shaped a narrative that has changed perceptions of women. In Eastern Europe, the male gaze towards women goes beyond a representation, since their own interpretations, fantasies about the female body and combinations with political and social traditions have influenced this vision. They have approached identity and the body from the object of consumption and desire: “The lack of understanding of the female body and the fear that it represented is one of the most reliable proofs that the male universe distanced itself more and more from women at every moment” (Figueroa, 2011, p.13). While it is true that many of them contributed to the feminist struggle through their works, the ways of doing so were different. Therefore, in order to observe the difference with respect to women, it is important to explore the creation of these artists and their respective conceptions of the female figure.

Gyula Konkoly: Born in Budapest, Konkoly is another Hungarian painter and university professor, who mixes the elements of reality with a surrealist and pop style. His painting At the Coast (1941) shows as the protagonist a woman wearing a yellow bikini and with an athletic posture, who looks directly at the viewer. As can be seen, the woman represents, in a certain way, the canon of female beauty, with a thin, sculpted and muscular body. In the same way, the fact of showing the woman in a bikini transcends a certain look of desire and objectification of the body and its forms. After all, beauty canons are social and cultural constructions that limit the female experience in the world, through imposed norms. While it is true, this work could also be interpreted as a celebration of the supposed natural beauty of the body, with a certain spontaneity in its natural environment.

PAGE| 24

György Kemény: born in Budapest, he is a Hungarian graphic artist, trained at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. His work, Car Crash (1968), represents two scenes, each characterized by that Pop aesthetic of bright and striking colors. In both, the protagonist is a woman with large breasts, who is wearing a green dress. However, the difference is that in the first part she is calm and collected; and in the second he becomes a witness to a car accident, hence the expression on her face changes and an “AH!” appears, on the left side. In this way, as can be seen, the woman, represented with large breasts and a tight green dress, is a symbol of a form of objectification from the male gaze. Her body, which exaggerates the canons of beauty, contrasts with the feminine reality of physical attributes. Additionally, the contrast between both scenes could show a duality in the representation, that transition from tranquility to tragedy, which symbolizes the vulnerability of the woman, going from being an object of beauty to being an object that feels when seeing the crash between cars. Nevertheless, the presence of the “AH!” underlines both the intensity of the emotion, as well as its trivialization, when next to a female subject.

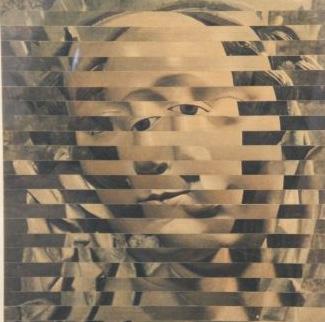

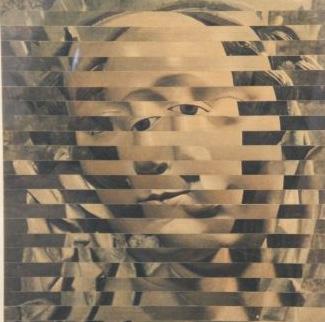

Jiri Kolar: Born in Protivin, in the Czech Republic, Kolar was a poet, writer and painter who used both the visual and written media to address his critical stance towards the regime. In his work Rollage (2002), Kolar, through this technique, cuts an image of a woman’s face into strips to later rearrange it and create this composition. Thus, he generates an effect of distortion and fragmentation that invites the viewer to reflect on the different perceptions of female identity in a society that he objectifies. On many occasions, the author uses this technique to question oppression, propaganda, and politics. Even so, although there is a clear component of criticism regarding the situation of women in society, an external vision towards the female image can also be extracted from this work, since at the end of the day he expresses his narrative from a certain emotional distance, depersonalizing the female subject and transforming her into a tool within a larger message. Rollage is not only the fragmentation of female identity, but it is also the step to reflect on the complexity of contemporary society.

PAGE| 25

As in Eastern Europe, Western male artists have also contributed to the creation of the dichotomy between “them” and “us”. Further influenced by popular culture and mass society, they shaped the perception of an entire era. From Warhol to Lichtenstein, they were all Pop pioneers, who redefined the representation of women in visual culture. Gender roles, consumerism, identity and femininity were the most discussed topics, offering the viewer a perspective never seen before. However, unlike artists from the East and due to the historical-cultural context, in the West ideals of femininity varied, influenced by emerging feminist movements. Furthermore, the proximity to the consumer society led the male gaze to approach a commercial representation of femininity and the body, in relation to advertising, cinema and music.

Roy Lichtenstein: Born in New York, he was a pop painter, graphic artist and sculptor, known for his interpretations of comic art. His work Drowning girl (1963) is one of the best examples, which perfectly shows his style, his aesthetics of comics and popular advertising. The protagonist is a woman in the middle of the water, with an expression of anguish as she is in danger of drowning. Next to her face, the following words appear: “I don’t care! I’d rather sink – than call Brad for help!” How could it be interpreted? The representation of the woman in a dangerous situation creates a contrast with that ironic narrative of detachment, of not wanting to receive any type of help. So, conventions are subverted and the woman is not a passive victim, but rather she is a figure who wants to save herself or die, rather than accept the help of a man. This type of internal dialogue could invite reflection on the role of women in society and the division of gender roles. Despite this, the fact that it is done from the male perspective can be associated with a less nuanced and sensitive representation in relation to female identity.

PAGE| 26

Tom Wesselmann: Born in Ohio, he was a pop painter, popular for his bold and striking female nudes. Great American Nude (1966) is one of his most notable works due to the provocative approach used when representing the female body. The female figures are voluminous, often nude, with clearly defined contours. As will happen with other authors, feminist critics have described this work as an example of objectification and sexism, in which the woman’s body is seen, once again, as an object of consumption and desire. On the other hand, this work has also been praised for challenging American society’s obsession with the body and sexuality, questioning established norms of representation. On many occasions, Wesselmann has been seen as a precursor of feminism in Pop Art.

Allen Jones: Born in Southampton, Jones is a British pop artist, known for his controversial erotic sculptures, in which he transforms a woman into a piece of furniture. For this reason, the work to be analyzed is Chair (1969), in which a woman, stylized and idealized, is part of the structure of a chair, in a provocative way, with exaggerated curves and a suggestive posture that evokes pin-up models. This representation can be understood as an objectification and sexualization of the woman’s body, by explicitly transforming it into a utilitarian object such as a chair. Likewise, the provocative way of showing it gives rise to a dialectic in which desire, power and consumption intermingle. Although some critics have interpreted it as an ironic criticism of traditional gender roles, questioning the treatment that women receive; the vast majority have condemned this work, calling it sexist and degrading.

PAGE| 27

Reception and criticism of Eastern European Pop Art based on women artists

The reception of Eastern European Pop Art was influenced by a political, social and cultural context very different from the rest of the movement. The communist regime and the Cold War gave rise to unique interpretations within this artistic movement. As mass culture was introduced in the Eastern bloc, criticism, debates and new social perceptions came to the fore. In the same way, the perception of gender and female Pop artists began to emerge, challenging traditional norms and finding in Pop Art a tool with which to express their ideals, as has already been seen. Although on many occasions her presence has been made invisible, her contributions to Pop narratives have been indelible: “The juxtaposition of incongruous everyday realities, culled from the mass media, that underpins the collage aesthetics of some pop manifestations, gave female artists an invaluable tool of unmask the gap between women’s

experience at home and the ideological grip of consumerism and media culture on their lives” (Minioudaki, 2015, p.79).

In this sense, many exhibitions such as Power up: Female Pop Art (Kunsthalle de Vienne, 2011) or Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958–1968 (Brooklyn Museum, 2011), although somewhat more focused on female artists from the West, have demonstrated the importance of the female figure, analyzing its impact and overthrowing the dominant masculine structures, thus inspiring a new analysis within Pop Art. Femininity and identity are the enclaves that have allowed women to transform cultural and social norms, showing the another side of the coin. The female body, sexuality and femininity are not objects for public use, but are private realities that belong to a group: women.

In relation to the above, criticism of Pop Art has often been based on questions that analyzed how the movement has perpetuated gender hierarchies, reinforcing stereotypes and male domination. Yet, as has been seen, both male artists and female artists knew how to give it another twist and used Pop Art to their advantage, achieving new possibilities of artistic

PAGE| 28

expression, in terms of equality and representation. Despite there being many male artists who did perpetuate the patriarchal vision of society, many others, from a different perspective, also fought on the same side as women. In short, Pop Art, or, at least, a part of it, has managed to end established perceptions, canons and stereotypes and show an alternative vision of the world, through challenging, avant-garde and feminine art.

PAGE| 29

In this long journey through Pop Art in the Eastern and Western European Bloc, it has been corroborated how women, as long as they have been an object of representation and as long as they have been an artist, have played a crucial role in the configuration of this artistic movement. Identities, body, ideologies, sexuality, femininity and, especially, “us” and “them” have been the keys that have developed the pop narrative in Eastern Europe and in the exhibition Women Between Us And Them: Identity In Eastern European Pop Art.

From feminism and symbolism in culture and nation, to local and global identities, the artistic landscape revealed has been most multifaceted and nuanced. Likewise, the comparison between female artists and male artists, both from the East and the West, has allowed us to study, from a different perspective, the dynamics of power and invisibility that will affect the female experience in this movement. The discourse of “us” and “them”, both from the point of view that contrasts men/women, and from the one that compares East/West, has proven to be a tool to analyze how women were perceived, both by themselves, as well as by men, influencing the reception and criticism of Pop Art.

Enriching the less studied contexts, as human beings we are aware of how traditional canons and stereotypes have configured a whole range of possibilities and categories, crossing the borders of art itself and giving shape to the so-called Pop Art. As Minioudaki stated at the beginning of this exhibition, challenging the traditional narrative of Pop Art, means expanding the gaze beyond male subjects and female objects, appreciating the diversity of voices and experiences, as has been done in this analysis. An

equitable understanding of the Pop legacy and the female role is fundamental to understanding the extent to which Pop Art in Eastern Europe is also a feminist art: “Recent feminist reviews of Pop have also pointed out the need for greater consideration of the perspectives situated and intersectional identities that impact the gender politics of artists who identify women in pop” (Hadler and Minioudaki, 2022, p.8).

PAGE| 30

Art, B. G. O. (2020, May 1). Boda Gallery of Art Gyula Konkoly 1941-): At the coast auction dates.https://www.bodaofart. com/aukcio.php?2-online-arveres-2020-05-01-10-konkoly-gyula-1941-tengerparton=&id=1658&nyelv=en

Busselo Furundarena, M. (2021). Pop art and its influence on the advertising of the century XXI. [Final degree project, University of Valladolid]. Uvadoc. https://uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/handle/10324/48691/TFG-N.%201659.pdf;jsessionid=7D4476D307487B96CAB3DBC1462012BD?sequence=1

Figueroa Arbeláez, A. (2011). Female image, object of art and consumer society. [Doctoral Thesis, Pontifical Javeriana University]. Repository Javeriana. https://repository.javeriana.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10554/4539/tesis257.pdf;jsessionid=9D66EF17A3

Hadler, M. and Minioudaki, K. (2022). Pop Art and beyond: gender, race and class in the global sixties. Bloomsbury. https:// www.google.hu/books/edition/Pop_Art_and_Beyond/-A9fEAAAQBAJ?hl=es&gbpv=1&dq=POP+ART+EAST&pg=PA312&printsec=frontcover

Kidder, A.D. (2014). Women Artists in Pop: Connections to Feminism in Non-Feminist Art. [Doctoral Thesis, Ohio University]. OhioLink. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/etd/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=ohiou1388760449 Magaña Villaseñor, L.C. (2016). Farewell to women as objects of consumption: use the body to reclaim the soul; the difficult path to freedom. The Artist Journal, (13), 40-48. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/874/87449339003/html/ Morales, G. (2018). Pop art and feminism. Jot Down. Contemporary cultural magazine. https://www.jotdown.es/2018/03/ pop-art-y-feminismo-en-espana/

Minioudaki, K. (2015). Feminist Eruptions in Pop, beyond Borders. The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, 73-95. https:// www.academia.edu/29678934/_Feminist_Eruptions_in_Pop_beyond_Borders_The_World_Goes_Pop_Tate_Modern_2015_73_95

Minioudaki, K. (2007). Pop’s Ladies and Bad Girls: Axell, Pauline Boty and Rosalyn Drexler. Oxford Art Journal, 30 (3), 402-430. https://www.academia.edu/9051247/Pop_s_Ladies_and_Bad_Girls_Axell_Boty_and_Drexler?rcc=same_author&rcpos=0&rcpg=0&rchid=28463266548

Plaza Morales, N. (2019). The protagonism of women represented by artists from the avant-garde to the present days. Raudem, Journal of Women’s Studies, (7), 22-45. ISSN: 2340-9630

Pollock, G. (2001). Vision, voice and power: feminist histories of art and Marxism. In Cordero Reiman, K. and Sáenz, I. (Ed.), Feminist criticism in the Theory and History of Art (45-81).

PAGE| 31