ROOTS OF RESILIENCE: TRANSCENDING ANTISEMITISM IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND THE SOVIET UNION

Nº 1 | MAY 2024

edit

reportage ROOTS OF RESILIENCE: TRANSCENDING ANTISEMITISM

Write and

SARA RUIZ BELMONTE Present the

IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND THE SOVIET UNION For the magazine ECHOES OF THE PAST Eötvös Loránd University Budapest, Múzeum krt. 4/a, 1088 TEL. (06 1) 411 6700

1. Introduction: Roots of resilience

2. What is antisemitism?

3. Exploring the roots of antisemitism

3.1. Religious origins

3.2. Socioeconomic origins

3.3. Political-nationalist origins

4. Antisemitism in the Russian Empire

4.1. Discriminatory policies

4.1.1. Pale of Settlement

4.1.2. Antisemitic legislation

4.1.3. Pogroms

4.1.4. False accusations

4.2. Pre-revolutionary and revolutionary Russia

5. Antisemitism in the Soviet Union

5.1. The Leninist period (1917-1924)

5.2. The Stalinist period (1924-1953)

5.3. The post-Stalinist period (1953-1991)

5.4. Continuities and changes

6. Impact of antisemitism and Shoah denial

7. Legacy of antisemitism in the Present Day

8. Conclusion: Echoes of the past

9. Bibliography

PAST ROOTS OF RESILIENCE: TRANSCENDING

ANTISEMITISM IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND THE SOVIET UNION

Editor’s note: Dear reader, welcome to the magazine Echoes of the past. This project was born with the purpose of remembering yesterday and giving a voice to those who were forgotten. By opening this window to the past we aim to learn from it, in order to better understand our present and forge a conscious future.

“Antisemitism is not an opinion, it is a passion. At first reason is appealed to justify that passion; later, it is appealed to justify violence” (Sartre, 1948, p.30).

In the vast expanse of human history, the experience of the Jewish people in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union has been a narrative replete with resilience, hope and suffering. Over the centuries, Jews have waged a constant battle against one of the most persistent prejudices in society:

antisemitism. Understanding this battle and unraveling the mysteries that the Jews experienced during these turbulent periods is necessary to comprehend History. In the Russian Empire, community life was defined by

fear and discrimination, suffering, day after day, the limitations of antisemitic policies, the inexplicable violence of pogroms and false accusations that only increased hatred and stereotypes. With the arrival of the Soviet Union,

PÁGINA| 4

ROOTS OF RESILIENCE: TRANSCENDING ANTISEMITISM

deceptive hopes for equality and justice turned into oppression and persecution, marking Jews as enemies of the state. For all these reasons, the following lines seek to reveal the forms of expression of antisemitism in these periods, taking into account its complexities, its impact and its legacy in the contemporary world. Confronting past, present and future, the aim is to reflect on the shadows that paint our history. Echoes of the past and the report Roots of Resilience: Transcending Antisemitism

In The Russian Empire And The Soviet Union invites the reader to remember the voices of the forgotten, in the hope of building a new society based on empathy, justice and equity.

What is Antisemitism?

Antisemitism. (s.f.). Hate Jews as a group or “Jew” as a concept. There are three types of antisemitism: religious, political and racist.

“Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews that can be expressed as hatred of Jews. The physical and rhetorical manifestations of antisemitism are directed at Jewish or non-Jewish persons and/or their property, at the institutions of Jewish communities and at their places of worship” (IHRA Definition of Antisemitism, 2024).

What does the word antisemitism mean? The word “antisemitism” was coined in 1873, by the German journalist Wilhelm Marr, in his pamphlet titled, The Road to the Victory of Germanism over Judaism. In this way, using“antisemitism”, Marr referred to the rejection of Jews, defining them as an ethnic group, a “race”, and not only as followers of a specific religion. Therefore, here lies the main difference between anti-Judaism, used by Christians; and antisemitism, that expresses racial hatred. Although initially the hostility towards the Jews was based on religion; the emergence of the word“antisemitism” made this hatred based on racial and biological reasons. Thus, the German journalist gave a pseudoscientific character to the“antisemitism”, blaming Jews for a whole variety of social and economic problems. While it is true that the word “semitic”, the etymological origin of “antisemitism”, did refer to a group of languages and peoples; in practice, the term “antisemitism” has been used to describe prejudice and discrimination only against Jews.

PÁGINA| 5

MAY 2024

JEWS BEING TRANSFERRED ON TRAINS

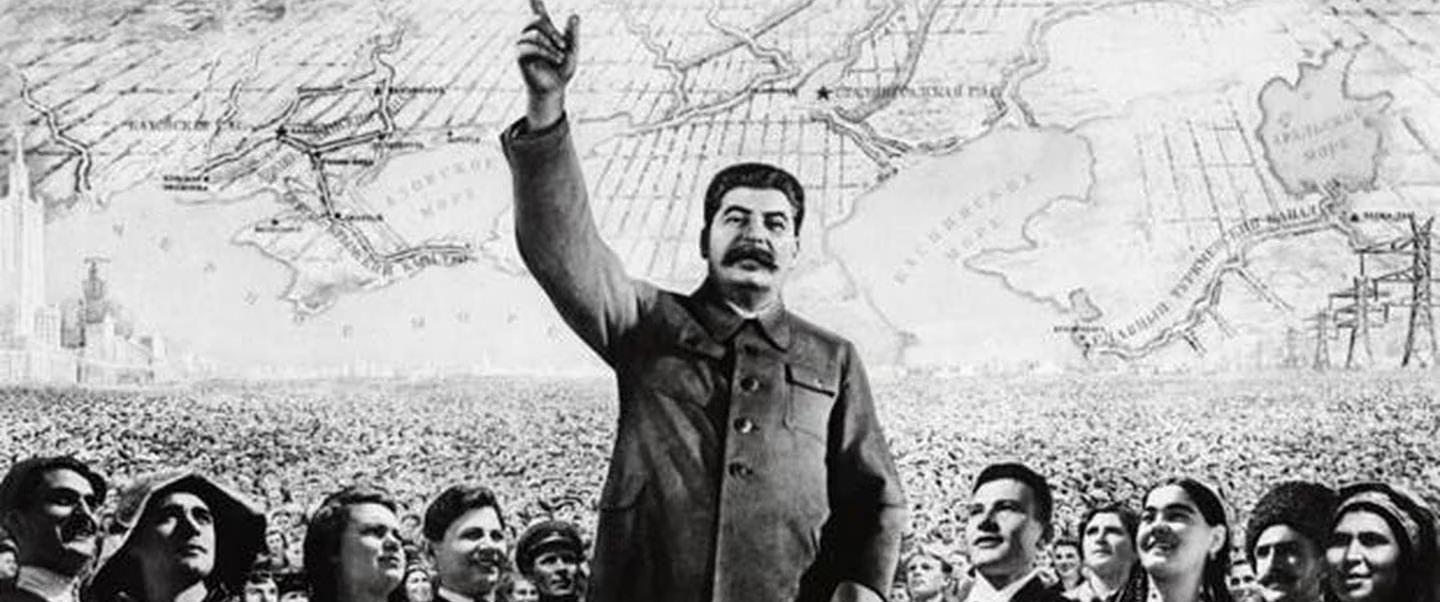

STALIN

EXPLORING THE ROOTS OF ANTISEMITISM

Antisemitism in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union is not another chapter in the history of hatred towards Jews, but rather represents the continuity of a complex narrative, full of suffering, prejudice and community resistance. But why use the word “continuity”? The roots of antisemitism date back to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, bringing together a whole set of religious, economic, social and political factors. However, with the passage of time, the establishment of the Russian Empire and the subsequent arrival of the Soviet regime, antisemitism mutated and took on new forms, reflecting a long tradition of mistrust, hostility and conspiracies. For this reason, the first step of this essay is to delve into the true origin of antisemitism, in order to understand the causes that fueled hatred towards the Jews, until reaching the means of expression that were achieved in the Russian-imperial period and in the Soviet Union. In this way, the structure of this point will allow to study the religious, socioeconomic and political-nationalist origins, to subsequently develop an entire history of transmission and causation that the Jewish community experienced.

PAGE |6

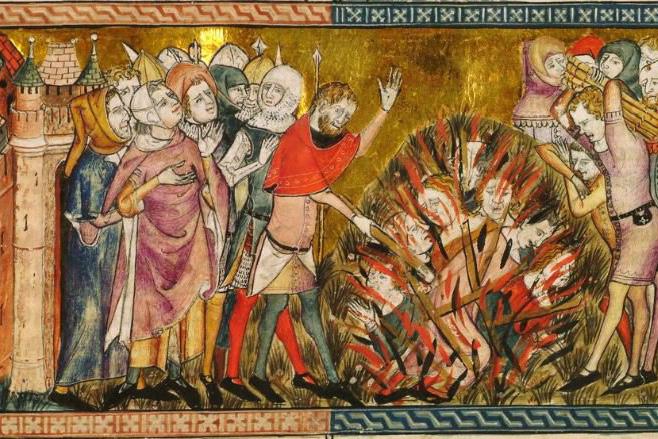

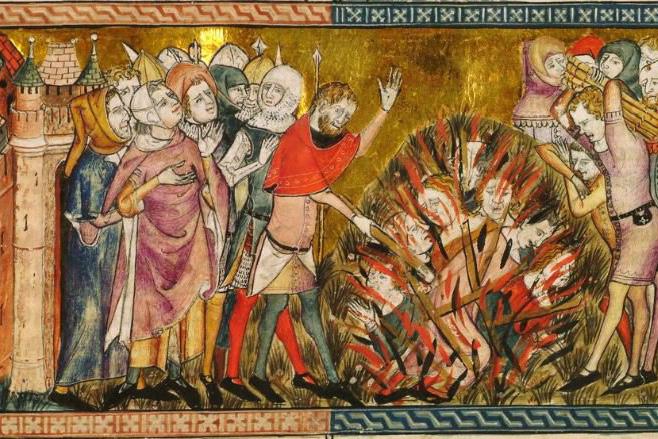

RELIGIOUS ORIGINS

The first link in the chain to be able to draw a complete outline of the evolution of antisemitism is the religious origins, based on Christianity during Antiquity and the Middle Ages. This origin is found in the gospels and the separation of Christianity from Judaism. Early Christians, based on the gospels, provided explanations about the trial and crucifixion of Jesus Christ and asserted that the death of the Messiah was a consequence of religious differences with respect to Judaism. Thus, these Christians blamed the Jews for persecuting Jesus, sowing the seeds of hostility and giving rise to the first persecutions. Likewise, during the 2nd century AD, in the Eastern Roman Empire, continued opposition arose because many Christian bishops created the so-called “adverse literature,” in which Jews were seen as adversaries. Therefore, the first ideas of conspiracy began to spread, and Jews were seen as a group that refuted Christianity within the framework of their contemporary culture, justifying persecution and murder.

Later, in the Middle Ages and with the establishment of the papacy of Leo I, the Catholic Church was echoed throughout Europe and the relationship with the Jewish community began to depend on the pope and the emperor. Yet, the date that marked a turning point was the year 1215 AD, since the signing of the Lateran Council established guidelines that referred solely and exclusively to the Jews: they had to distinguish themselves, through clothing; they were not to hold public office; and the converts could not preserve their ancient practices. In addition, accusations of the “blood libel”, which would argue that Jews used the blood of Christian children in rituals, increased, as did periodic massacres in times of crisis, such as the Black Death. Finally, the Middle Ages also witnessed the creation of an entire iconography, using pamphlets and manuscripts, that stereotyped the image of the Jew: beard, hooked nose, bag of coins and unusual clothing: “When talking about Jews, it remains all too easy to fall back on malicious clichés” (Eugster, 2024).

PAGE | 7

As has been seen when analyzing the religious origins, these were the trigger that created an entire stereotype of the Jew, in which some of the most relevant prejudices were those related to money, speculation and economic interests. Hence, it is also interesting to study the socioeconomic factors that led to the origin of this primitive antisemitism. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Jewish community suffered all kinds of restrictions, including: the prohibition of owning land; to dedicate yourself to agriculture; to participate in public life; and to join artisan guilds and other urban professions. Accordingly, one of the few opportunities to survive was to engage in money lending. Nonetheless, usury, prohibited by the Catholic Church, became an activity typical of the Jews, viewed with contempt and resentment. In England, during the reign of Henry II and John Landless, and with the economic crisis experienced, the Jews were crucial, as well as unpopular, as in numerous cities of the Holy Roman Empire.

In times of economic and social crisis, arguments against Jewish lenders were a constant that led to increased Jewish segregation. In many European cities, Jews were forced to live in ghettos, that is, in walled areas that isolated them from the rest of the urban population. For example, Venice established the first ghetto in 1516, which was closed at night, so that its residents could only go out to work during the day. The case of Rome, with Pope Paul IV, was similar, but with an even more radical justification, since through a papal bull, the Jews were confined to avoid contaminating Christian doctrine, through speculation. Therefore, the combination of all types of restrictions, both, social and labor-related, and forced segregation, exacerbated economic resentments and began to shape the first expressions of antisemitism, fueling a focus of hatred that would endure to the present day.

PAGE |8

Just as religion and socioeconomic factors are important, there are two fundamental concepts that cannot be forgotten when it comes to studying the origins of antisemitism: politics and nation. To do this, it is necessary to travel back to the 19th and 20th centuries, with the emergence of the so-called nation-states and nationalism itself. When the nationstate is mentioned, reference is made to a form of political organization that has a delimited territory, a stable population, an effective government, its own sovereignty and is identified with a set of values, traditions and national symbols. Likewise, nationalism is an ideology that promotes the feeling of devotion towards the nation, with the desire to establish a state, highlighting the importance of national identity and the preservation of culture, language and traditions. In this manner, as a result of both concepts, a new narrative began to emerge characterized by “us” and “them”, that is, the Jews, the others. Within these nation-states that aspired to obtain cultural and ethnic homogeneity, the Jewish community is the other, the disruptor that fragments the stability of a culture and a supposedly pure nation that desires to obtain unity and national cohesion. So, nationalism and the nation-state complement each other to provide a pseudo-intellectual basis for antisemitism, legitimizing exclusion and persecution.

“The Ratification of the Treaty of Münster”

By Gerard Terborch, 1648

The Treaty of Münster, between Spain and Holland, was one of the treaties that led to the Peace of Westphalia, where the concept of the “nation state” was born.

PAGE | 9

ANTISEMITISM IN THE RUSSIAN EMPIRE

Having explored the origins of antisemitism, it is time to delve into one of the most significant part of this narrative: antisemitism in the Russian Empire. From the diverse origins of antisemitism, to its transmission and causation, hatred towards the Jewish community was not only cultural, but in this period it took root through institutionalization, making use of discriminatory government policies and acts of violence. However, before beginning, it is important to establish what the Russian Empire was. In this sense, the Russian Empire was a political entity, from the late 16th century until the Revolution of 1917, which encompassed numerous regions of Eastern Europe, Central and Northern Asia, and parts of the Caucasus and the Far East. The predominant form of government was tsarism, an autocratic monarchical system, led by the figure of a tsar who controlled power and wealth. As well, society was divided into classes, which increased political and social tensions, due to the numerous demands for reforms and the emergence of revolutionary movements that would bring down the empire in 1917.

Despite the many centuries of history of the Russian Empire, the Jewish question gained relevance after the annexation of Poland, between 1772 and 1795. Over the course of a century, the presence of the Jews and their legal status became the subject of political debate, taking place the emergence of the so-called “antisemitic culture” (De Michelis, 2001, pp.15-16, cited by Comensoli, 2019, p.12): the status of the Jews did not depend on the limitations to which were subject after their conversion, but it was a deeper issue in Russian culture. In this way, as Dr. Comensoli states: “The Jewish question was not only limited to a problem of integration, but it was strictly related to the growing fears towards modernity as a consequence of the socioeconomic changes” (Comensoli, 2019, p.12). For this reason, in the following lines, taking into account all the origins, Jewish stereotypes and the growing role of this community in the economy, the forms of expression of antisemitism in this period will be addressed: from discriminatory policies and antisemitic legislation, to pogroms, false accusations and revolutionary practices.

PAGE |10

TRANSMISSION AND CAUSATION

The first link of this study of antisemitism in the Russian Empire are the discriminatory policies that institutionalized hatred and marginalization of the Jewish community, reinforcing the stereotypes and prejudices, already explained in the origins. Local authorities implemented a whole series of laws with the sole objective of restricting the rights of the Jewish community, limiting their opportunities, both economic and social. Because of this, at this point, various policies that personified, in every sense of the word, antisemitism will be explained.

PAGE | 11

With the reign of Empress Catherine II (17631796), the approach to the Jewish question changed at the end of the 18th century, coinciding with the fear of many European autocracies after the triumph of the French Revolution. Thus, this change was reflected in many of the antisemitic provisions taken by the empress, such as the establishment of the Pale of Settlement in 1791: the western border region of the Russian Empire where the settlement of Jews was permitted. Although there was no single provision regarding the creation of this area, Tsar Nicholas I, in 1835, officially defined the borders and name of the Pale of Settlement: “Jews are allowed permanent residence: (a) In the provinces: Grodno, Minsk, Ekaterinoslav. (b) In the districts: Bessarabia, Bialystok” (Nicholas I, 1835, cited by Mendes, P. and Reinharz, J., 1995, p.379). According to the historian Nathans (2002), the rise of Nicholas I represented a change of perspective regarding the Jewish question, since this tsar abandoned the idea of conferring autonomy to the Jewish community and changed the

political approach established by Alexander I and headed toward greater assimilation.

As far as this region is concerned, the shtetl emerged as a form of identity and organization of the Jewish community. These Jewish villages predominated in the Pale of Settlement, in which daily life, tradition and culture flourished despite the difficult conditions imposed by the tsarist government: “The shtetl became the embodiment of a Jewish spirituality” (PetrovskyShtern, 2014, p.10). The shtetl were communities closely linked to all Jewish traditions, which was a challenge to overcome the antisemitic legislation that the government imposed in this area. The inhabitants faced education quotas, restrictions on land ownership and the practice of professions, as well as violence carried out by local authorities, through pogroms, an extreme manifestation of antisemitism in the region. The decline of the Pale of Settlement began with the great waves of migration to America in the early 20th century and culminated in its formal disappearance during the Russian Revolution.

PAGE |12 DISCRIMINATORY

Likewise, after the creation of the Pale of Settlement, antisemitic forms of expression expanded to all types of government practices. Depending on the reigning tsar, legislation and limitations on the Jewish community evolved from legal restrictions to forced relocations and expulsions. For this reason, the reigns of Nicholas I, Alexander III and Nicholas II will be analyzed, studying their most representative measures of antisemitism.

Firstly, during the reign of Nicholas I (1825-1855) and after the definition of the Pale of Settlement, this tsar enacted another series of measures that limited the freedoms of the Jews. In 1827, the Military Conscription Decree was ratified, which obliged Jewish citizens to serve in the tsarist army for a period of 25 years, which meant that many young men, through the use of violence, were forcibly re-conscripted, separated from their families and subjected to forced conversion to Christianity. This same year, the Kyiv Expulsion Law was also issued, which established the expulsion of Jews from Kyiv, one of the most important cities in the Pale of Settlement, the seat of Jewish culture. In addition, in 1844, Nicholas I abolished the kahal,

the theocratic organizational structure of the Jewish community, dealing a significant blow to the autonomy and self-government of Jews in the Russian Empire. Secondly, under the reign of Alexander III (18911894), the so-called May Laws were enacted in 1882. These prohibited Jews from establishing new housing outside cities and shtetls, purchasing or renting land in rural areas, and opening shops on Sundays and holidays, increasing economic pressure and limiting livelihood opportunities. Furthermore, this tsar ordered the expulsion of the Jewish community from the city of Moscow, causing enormous relocation and plunging families into extreme poverty. Finally, under Tsar Nicholas II (1894-1917), state antisemitism did not cease, but rather increased. The existing restrictive policies were maintained and the government encouraged and allowed the pogroms that will be studied in the next point. Therefore, exploring the legislation, carried out by three of the tsars of the Russian Empire, it has been possible to observe how these forms of antisemitic expression formed an oppressive system that sought to control and marginalize the Jewish population, reflecting the extreme level of antisemitism.

PAGE | 13 DISCRIMINATORY POLICIES

NICHOLAS I

ALEXANDER III

NICHOLAS II

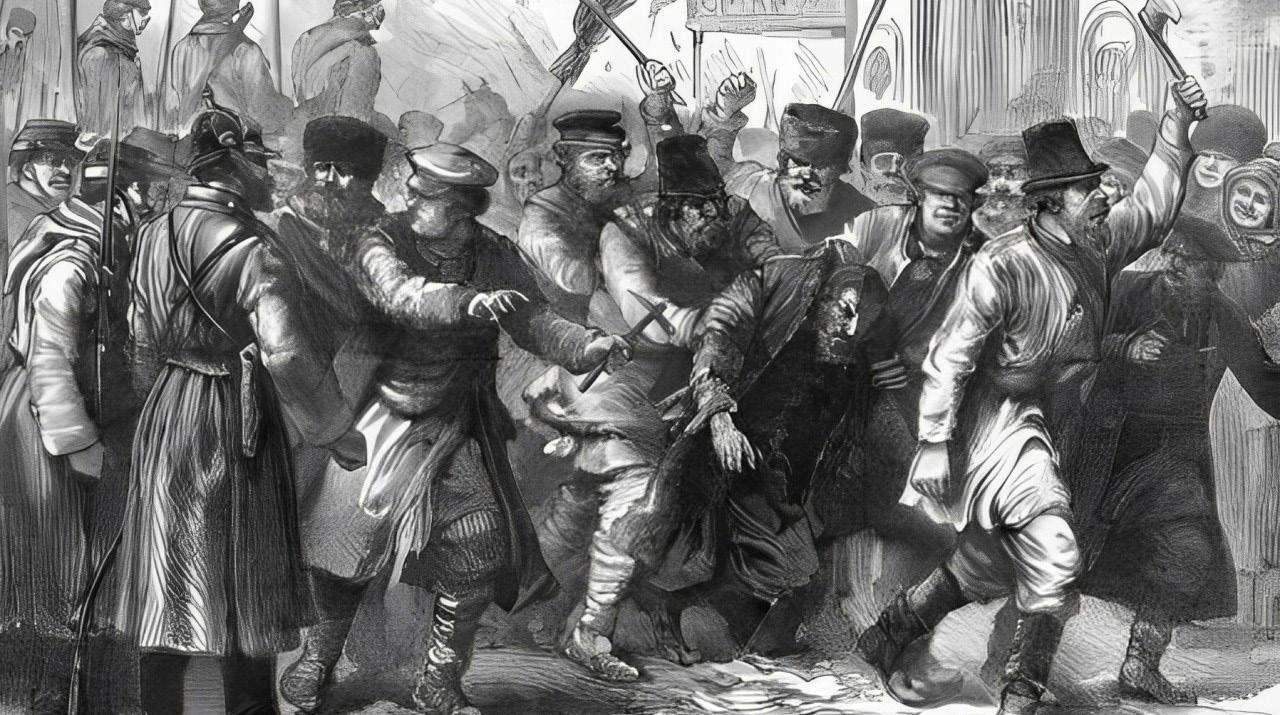

DISCRIMINATORY POLICIES: POGROMS

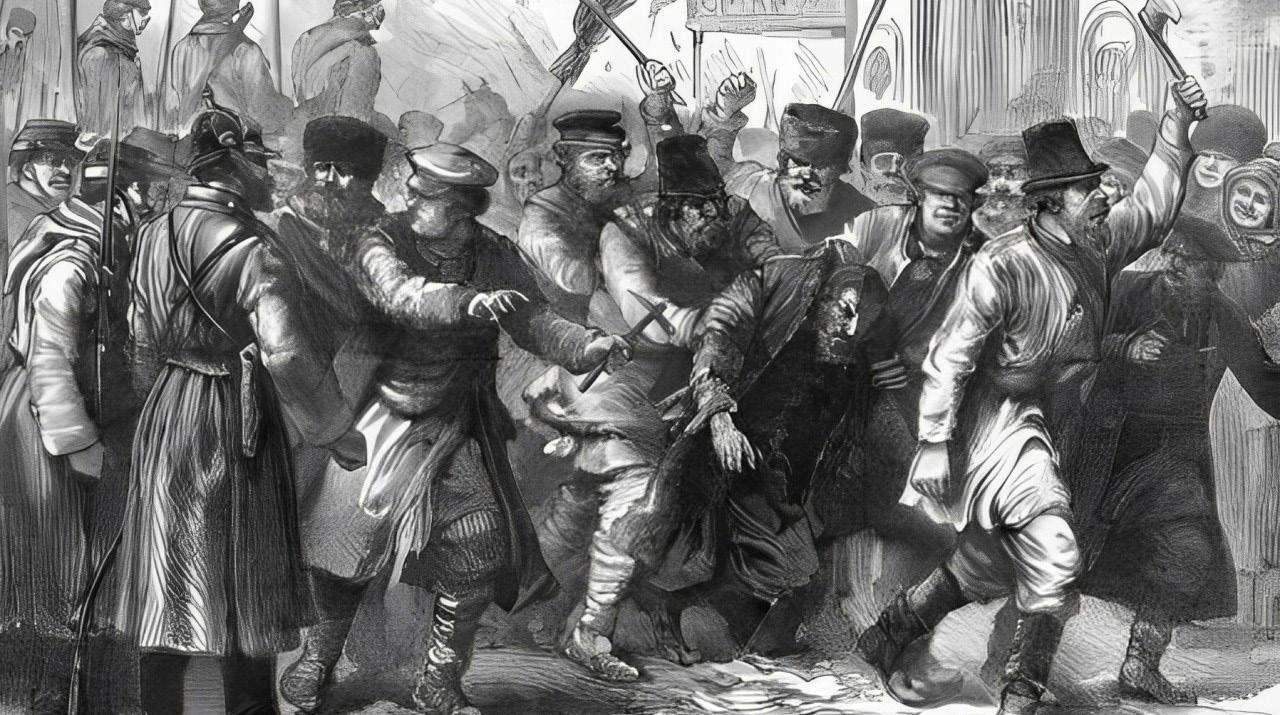

As anticipated in the previous section, one of the maximum expressions of antisemitism were the pogroms, violent attacks directed against the Jewish communities in the Russian Empire, characterized by looting, physical and sexual violence, and the mass murder of Jews. According to the historian David Engel: “Systematically organized massacres and robberies carried out with the aid of an indifferent attitude, or even of a coordinate action of the police authorities, as was the case in Russia” (Engel, 2011, p.20). These pogroms, which occurred in two waves during the period of the empire, one after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II and another during the revolution of 1905, left an indelible mark on Jewish collective memory, being a reflection of rampant antisemitism. The pogroms began at the end of the 19th century and continued until the beginning of the 20th century, determined by the population’s growing fears of the Jewish community; for religious discrimination; and for all the antisemitic policies seen above. Thus, the hatred towards this community culminated in the launching of these pogroms, which although they lasted a few days, were attacks that continued for years.

The first wave, between 1881 and 1884, constituted a turning point in history, since while in previous decades it was thought that the Jewish question would be resolved through assimilation, these pogroms eliminated any kind of hope. Similarly, the pogroms began to form the concept of a Judeo-Bolshevik ideology. The intensity of these diversified according to the Pale of Settlement area, and they were concentrated in the southern regions, corresponding to modern Ukraine. The Kyiv pogrom, in 1881, was one of the most notorious of this era, as an angry

crowd attacked the Jewish community, perpetrating acts of unparalleled violence, in which hundreds of Jews died, in which the synagogue was burned and Jewish property was destroyed. In the same year, the city of Odessa was the scene of another of the most violent pogroms, in this wave of antisemitic violence, leaving a significant number of dead and injured and contributing to the atmosphere of fear and despair that prevailed among the Jewish community. Likewise, in 1883, the city of Minsk, in western Russia, suffered another important pogrom, the result of a combination of factors among which the spread of conspiracy theories predominated. With the incitement of the local authorities and the initial association of the Jewish community with Bolshevism, Minsk witnessed destruction and hatred.

PAGE |14

1881-1884 AND 1903-1906

The second wave, during the years 1903 and 1906, continued with the extreme violence, already begun in the first. However, these pogroms were particularly brutal and widespread, spreading throughout the country and generating a devastating number of deaths, injuries and material losses. In a context of revolutionary unrest, with civil and political tensions culminating in the Revolution of 1905, pogroms were used as tools of repression and as a way to divert attention from social and political problems. In 1903, one of the most infamous pogroms of this era took place in the city of Kishinev, now Chisinau, in Moldova. After a local newspaper published antisemitic propaganda, the Jewish community suffered all kinds of torture, looting, rape and murder. Correspondingly, in 1905, Odessa experienced another pogrom, after a series of riots and clashes between different ethnic and political groups. The crowd that carried out the pogrom was incited by hatred, antisemitic propaganda and discontent with the economic situation, for which they blamed the Jews. Jewish synagogues, homes and businesses were the main targets, as well as the people themselves.

In conclusion, the pogroms involved episodes of unbridled violence and persecution against a community, leaving a legacy of suffering and trauma. Hate, intolerance and propaganda were the protagonists of this period, having devastating consequences at the community and social level and underlining the extreme need to put an end to antisemitism. As David

Engel states, for the perpetrators of the pogroms: “Jews thus merited, in their own eyes as well as those of the surrounding society, a degraded status” (Engel, 2011, p.30). Definitely, fear and distrust were echoed among the Jews of the empire, awakening a movement to defend identity and self-determination.

PAGE | 15

DISCRIMINATORY POLICIES

FALSE ACCUSATIONS

Ultimately, within this section of discriminatory policies, the false accusations suffered by the Jewish community, personified in the Beilis Case, between 1911 and 1913, will also be addressed, since it

represented a milestone in the fight against antisemitism. In March 1911, the body of a young man, Andrei Yushchinskiy, was found in a forest near Kyiv. Following the discovery, the press speculated about a possible Jewish ritual murder, resulting in the arrest of Mendel Beilis, a Jewish worker: “The tsarist regime decided to find a Jew and put him into the prisoner’s dock as a ritual murderer” (Rogger, 1966, p.616). With an investigation plagued by prejudice and antisemitism, false testimonies and manipulations were the protagonists that managed to influence the prosecution, presenting the theory of ritual murder, accusing Beilis of having used the young man’s blood. Though, with international attention focused on this case and with a team of expert lawyers, both Jewish and non-Jewish, the defense managed to demonstrate the lack of evidence. Consequently, on October 28, 1913, Beilis was acquitted of all charges and the Jewish community received the verdict as a true symbol of resistance to antisemitic policies. Therefore, the Beilis case was another example of antisemitism, but also of struggle and Jewish awareness, inspiring new discourse on equality.

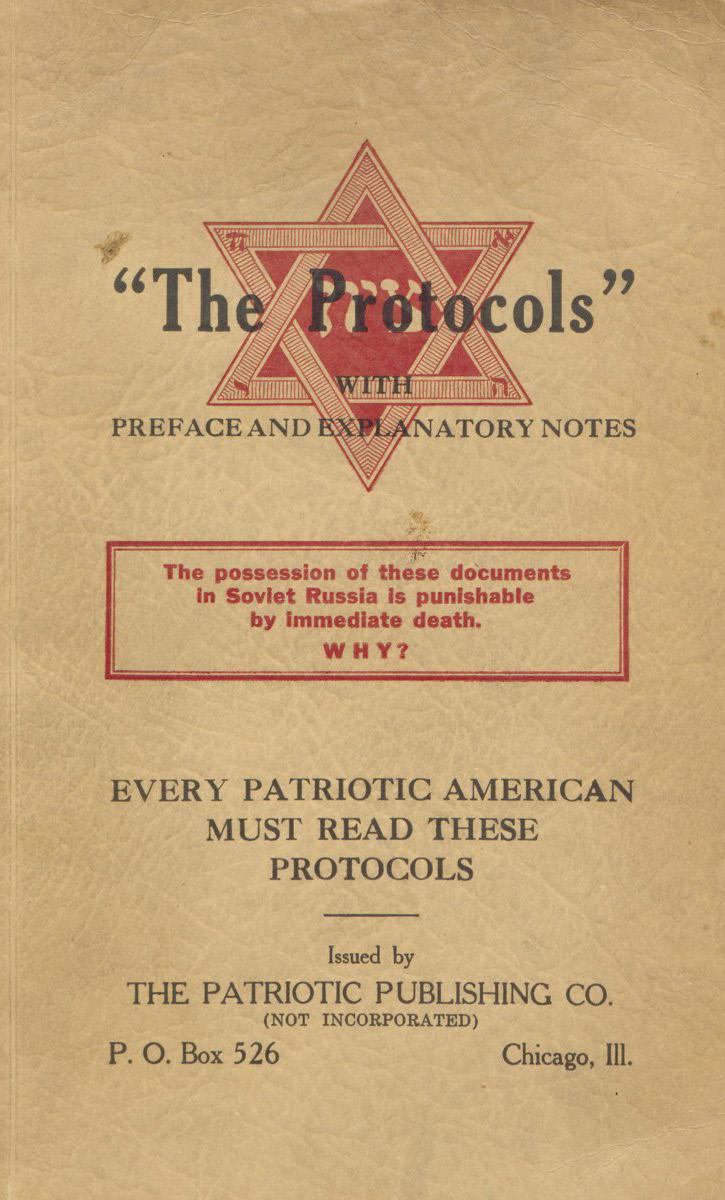

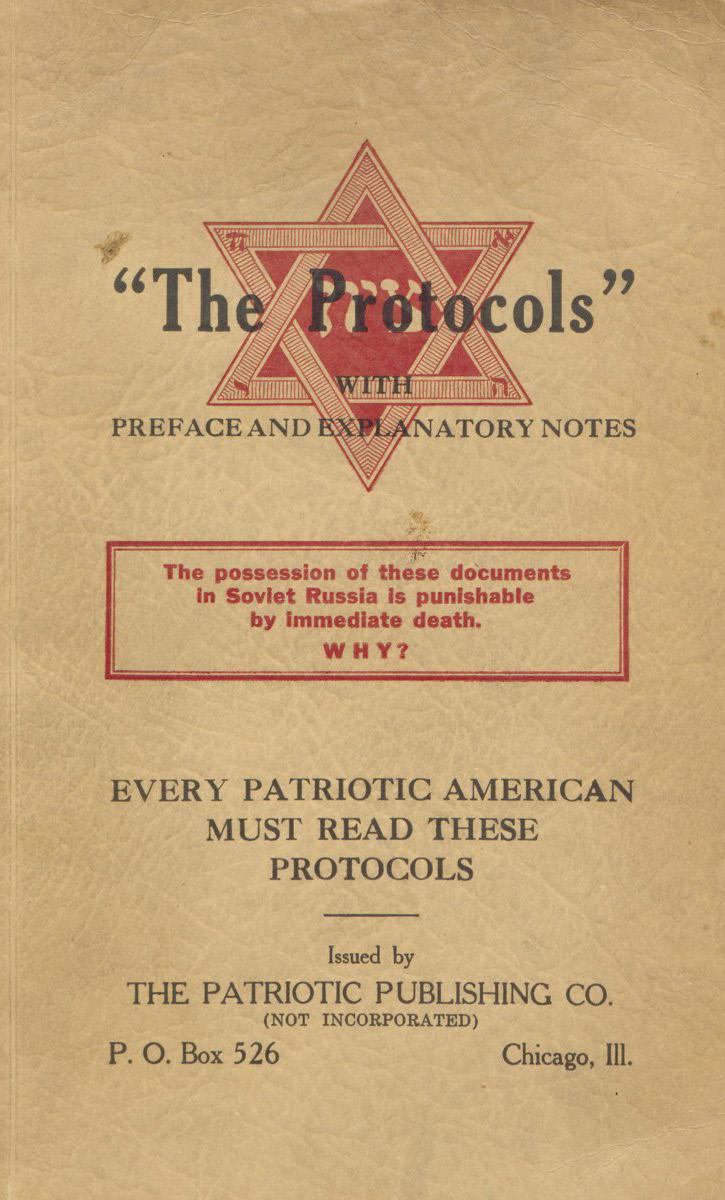

PRE-REVOLUTIONARY AND REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA

The outbreak of the pogroms was followed by all kinds of restrictions and the emergence of one of the greatest forms of expression of antisemitism in 1903, in prerevolutionary Russia: the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This false document is the creator of one of the conspiracy theories against the Jewish community, which has had the most impact throughout history: “The best-known text that caused the most damage for decades, inspiring the antisemitism of the interwar period, was that of the so-called Protocols of the Elders of Zion” (López, 2018, p.27). The text was written as if the author were one of the members of this group that, throughout twenty-four protocols, recounts the desire of the Jewish community to destroy the Christian world and impose an autocracy with a Jewish king, through the control of gold, the press and political parties. Thus, the protocols served to punish the Jewish community in the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 20th century, in which the Black Hundreds carried out pogroms: “The book was meant to serve a political function, to influence powerful individuals or mobilize large groups of people to think or act in particularly destructive and self-deluding ways” (Segel, 1995, p.4).

PAGE |16

REVOLUTION OF 1905

Nevertheless, the text became much more famous after the First World War (1914-1919), when the Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian Empires collapsed. In short, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion became one of the most important expressions of antisemitism that, as will be seen, continued alive during the period of the Soviet Union.

On the opposite side of this increase in antisemitism with the protocols, another important episode in this prerevolutionary and revolutionary period was the Russian Revolution of 1905, which required greater relevance of the Jewish question in the political debate. While it is true that it did not completely eradicate antisemitism, it created

a favorable climate to promote equality. The demands for political, social and economic reforms inspired groups from all social classes, which demanded change and greater equality of rights. As a result, many Jews joined the demonstrations, demanding an end to discriminatory and antisemitic policies and attracting international attention. In this context and in response to all the social mobilization, the Russian government implemented certain reforms, including the expansion of civil rights for Jews. Hence, despite the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the other side of the coin was this revolution that helped lay the foundations of tolerance and justice.

In conclusion, antisemitism in the Russian Empire was a deeply rooted reality, not only on a cultural level, but also on a political and institutionalizing level. Manifested through various forms, from legal restrictions, to pogroms, unfounded accusations and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, antisemitism spread fear, distrust and suffering in the lives of members of the Jewish community. However,

the turning point in the Russian Revolution of 1905 marked a before and after in the antisemitic struggle, awakening social conscience and leading to reforms that expanded rights and freedoms. Even so, this advance did not eradicate the presence of antisemitism, quite the opposite. With different forms of expression, this hatred towards the Jewish community will also be present in the period of the Soviet Union.

PAGE | 17

ANTISEMITISM IN THE SOVIET UNION

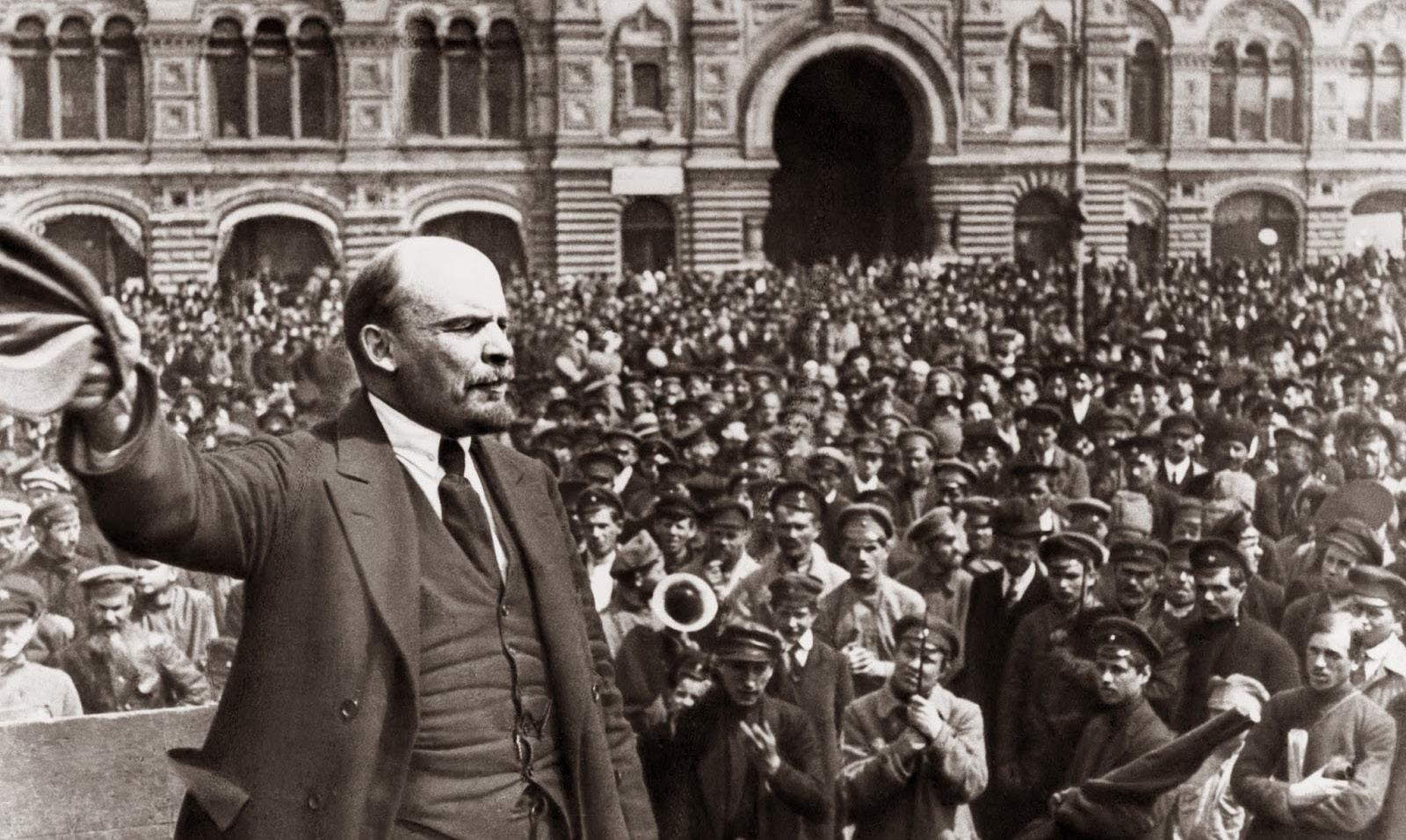

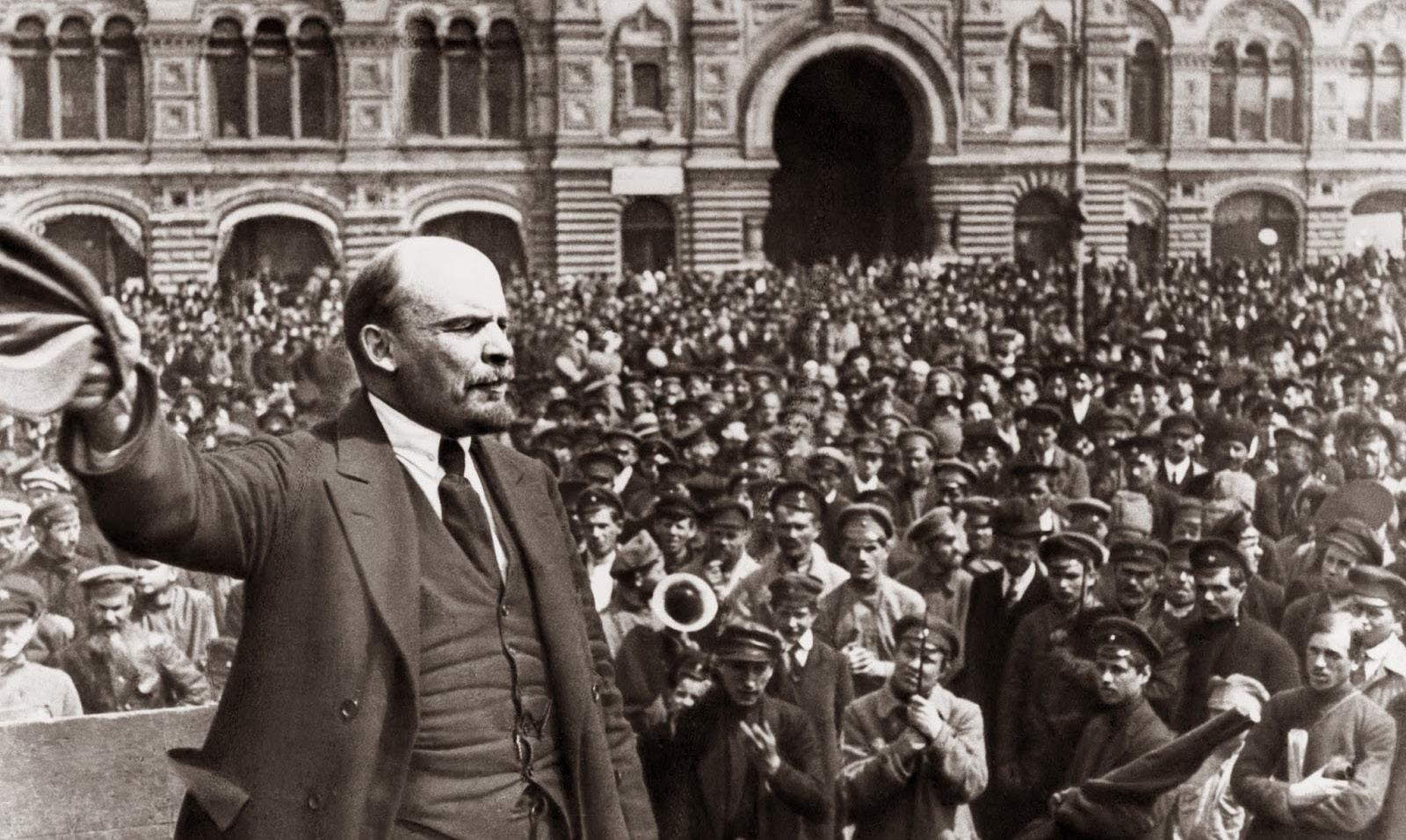

Having studied antisemitism in the Russian Empire, it is time to address the forms of manifestation of hatred towards Jews in the Soviet Union, as well as continuities and changes. Nevertheless, to understand it better, it is necessary to start from the end of the Russian Empire and the emergence of the Soviet Union, with the Revolution of 1917. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian Empire was going through a deep socioeconomic division, in which tensions between the population and Russia’s participation in the First World War further aggravated the situation, leading to extreme poverty, food shortages, inflation and deaths on the battle front. As a result of popular unrest, the February Revolution of 1917 broke out and the protests managed to eradicate the tsarist regime of Nicholas II, establishing a provisional government of liberals and socialists. In October 1917, a new revolution took place again, this time led by the Bolsheviks, headed by Lenin, who carried out a coup d’état, stormed the Winter Palace and took power, beginning a new stage for Russia: the Communist regime. Yet, between November 1917 and June 1923, the Bolshevik government (the Red Army)

clashed with supporters of Tsarism, liberals, and other groups (the White Army) in the Russian Civil War. Finally, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was created on December 30, 1922, based on the principles of Marxism-Leninism and seeking a classless society with a centrally planned economy.

Regarding the relationship between antisemitism and the establishment of the Soviet Union, it can be said that one of the most widespread stereotypes was the identification of Jews with the Bolshevik revolution, as if they had been the organizers of the socialist regime: “For those who believed in world Jewish conspiracy theories, the Bolshevik revolution was a sign that Judaism had taken power in the former Russian Empire as one more step towards planetary domination” (López, 2018, p.2). This association can be related to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, since they became much more famous after the First World War. For many Westerners, the imposition of the Bolshevik Regime confirmed what the protocols had reported about the Jewish conspiracy. Furthermore, the fact that there were figures of Jewish origin in the socialist government, such as Trotsky or Zinoviev, encouraged

PAGE |18

antisemitism. Thus, with the creation of the Soviet Union and the birth of the Weimar Republic in Germany, the protocols began to be translated into many languages, circulated massively, and many started to attribute their defeat in the war to this alleged conspiracy.

Likewise, in 1920, the British newspaper The Times showed that half of the text was plagiarized from the political satire, Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli Montesquieu, by Maurice Joly, a criticism of the imperial government of Napoleon III. However, despite the clear falsehood of the text, this demonstration was not enough to stop the Nazi regime from coming to power in 1933 and disseminating the protocols, based on the narrative of “us” and “them”: “But for the government of Nazi Germany it was not important to prove that it was true: deep conviction was enough that this conspiracy was underway and that it had to be stopped” (López, 2018, p.32). Therefore, seeing the evolution of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, from the Russian Empire to the Soviet Union, it can be stated that the story of the Jewish conspiracy was one more example of justification of antisemitic policies that perpetuated Jewish stigma and

CONTINUITIES AND CHANGES

the persecution of the community. In this way, the Soviet period constitutes an extension of the antisemitism of the Russian Empire, epitomized in the governments of Lenin and Stalin and in the post-Stalinist era.

PAGE | 19

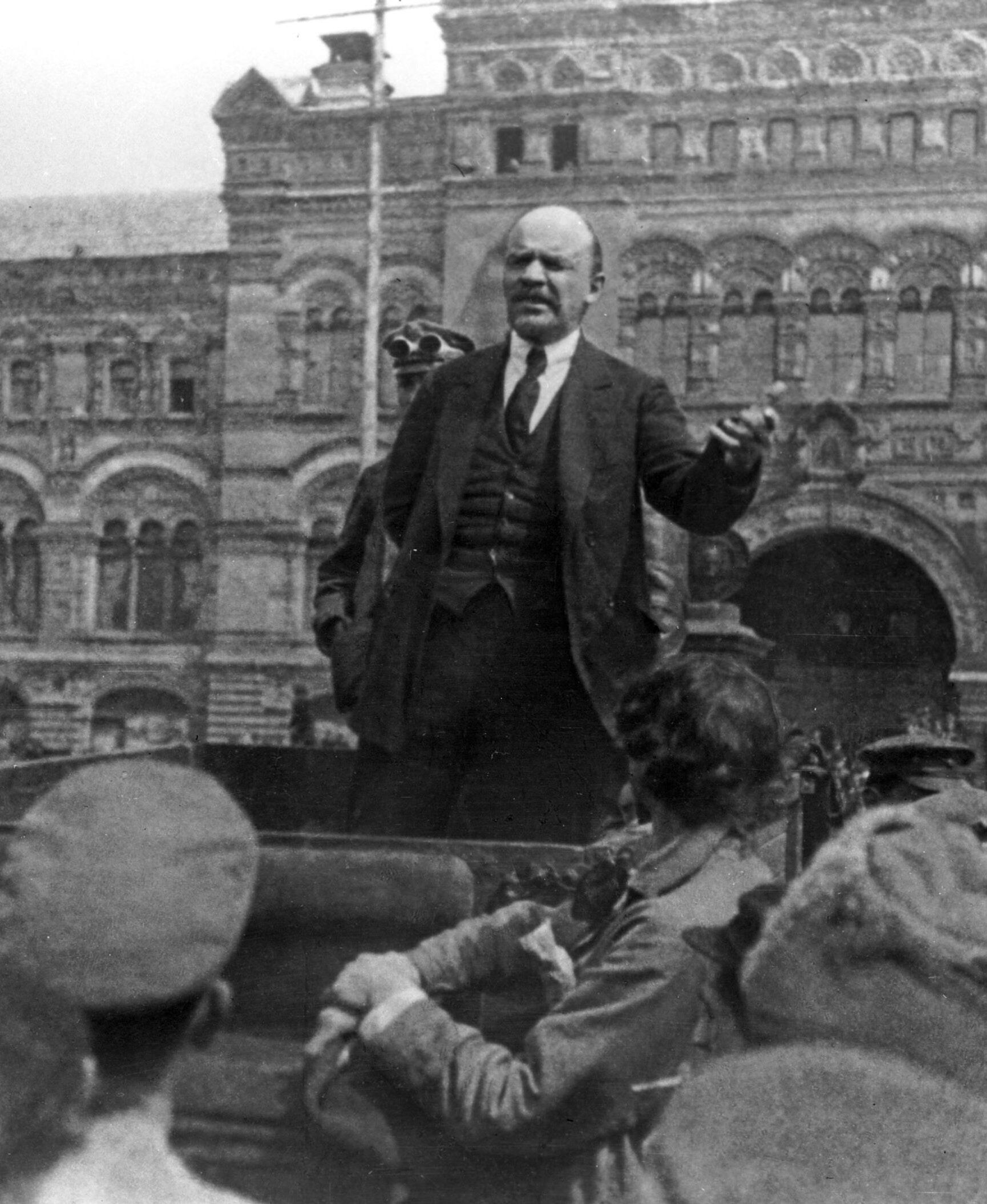

After the establishment of the Bolshevik government, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, alias Lenin, came to power, being the main leader of the October Revolution of 1917. He was appointed president of the Council of People’s Commissars and became the first and highest leader of the USSR in 1922. Despite the proclamation of equality of all citizens and the official condemnation of antisemitism by the Bolshevik government, Jews still had to face manifestations of antisemitism during this Leninist period. The official equality policy established in the 1918 Soviet Constitution, which guaranteed civil and political rights to all citizens, was not the same in theory as in practice.

Firstly, during the Leninist period the third wave of pogroms took place, between 1918 and 1921, coinciding with the years of the Civil War.

The Leninist period (1917-1924)

The main perpetrators of these violent attacks were the Whites, (opponents of the Bolshevik regime), the anarchists and nationalists, defending the purity of culture and going against those they considered the ideologues of the 1917 Revolution. One of the most notorious pogroms of this moment was that of Kyiv in 1919, in which ethnic and religious tensions were the protagonists. The pogrom lasted several days and was triggered by rumors of conspiracy against Jews, accused of supporting the Bolsheviks and hoarding food and supplies. All this, together with antisemitic propaganda. It unleashed a wave of inexplicable violence, which the authorities made no attempt to stop. So, the Kyiv pogrom was a turning point in postrevolutionary Russia, being another reminder of the horror story that the Jewish community experienced.

Secondly, Jews also had to face socioeconomic discrimination, due to all the restrictions placed on private property and state control of the economy. In this manner, those Jews who were dedicated to trade and lending were seriously affected. Equally, access to education and employment was limited for them, making up a very small list of the social opportunities they had.

One of the greatest examples of these limitations is represented by the establishment of admission quotas for Jewish students in the main Soviet universities, such as Moscow State University or Leningrad University. Because of them, places for Jewish students were very few and many of them were forced to give up higher education.

Thirdly, the issue of cultural and religious stigmatization must be addressed, since, despite attempts to promote secularization and equality, the Jewish community was stigmatized and treated at a lower level, compared to the rest of citizens. For that reason, Jewish institutions were dismantled, the use of Yiddish was prohibited and the dissolution of Jewish culture was promoted, in favor of a forced assimilation of Soviet culture, similar to the assimilation intended by the tsarist regime. As a result, many of the USSR’s synagogues were closed, becoming mere public buildings, leading to the rise of clandestine religious practices. Consequently, everything that the Soviet regime promulgated about equality and the creation of a new society based on respect was not being fulfilled, but quite the opposite, as the Jewish community was once again the object of marginalization.

PAGE |20

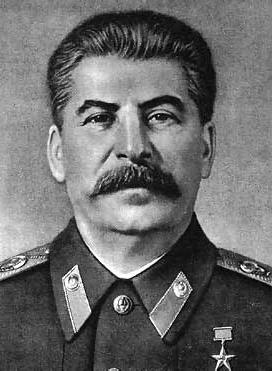

The Stalinist period (1924-1953)

Having studied the Leninist period, it is time to move on to the government of Joseph Stalin, a politician and military man who was among the Bolsheviks who promoted the October Revolution of 1917 and who later held the position of general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. During Stalin’s rule, the Soviet Union underwent major changes due to the replacement of the New Economic Policy of the 1920s by a centrally planned economy, with five-year plans that promoted rapid industrialization and collectivization. Hence, the USSR evolved from being an agrarian power to being an industrial one and became the second largest economy in the world after World War II. Regarding antisemitism during this period, one can speak of a resurgence and even of the term “Stalinist antisemitism”, which designates one of the historical forms of antisemitism derived from Stalin’s ideology, which promoted Soviet patriotism and reflected a growing distrust and hostility towards the Jewish community. In this way, it can be stated that Stalin’s regime recovered, for its benefit, all those antisemitic prejudices, previously seen, and turned against a group that did not consider a Soviet ethnic group as such, but rather an associated confessional and cultural group with the desire to set up a Jewish empire.

As with Lenin, the Soviet regime officially condemned any antisemitic act. However, the policies and practices implemented by Stalin did not respond to this reality. If before Jews were associated with Bolshevism, now they would be associated with cosmopolitan, imperialist and anti-Soviet elements. Nonetheless, when discussing antisemitism in this period, reference must be made to the

case of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee and the Doctors’ Plot. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Stalin launched a diplomatic campaign in the West to win over public opinion in democratic countries. To achieve this, one of his tools was the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, aimed at supporting Jewish communities abroad, in order to receive material aid and weapons. During the invasion of the USSR, the Nazis annihilated most of the Jews, either by shooting or by lethal gas. As such, the turbulent atmosphere led the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee to propose the idea of creating a Jewish Soviet socialist republic within the USSR, to preserve Yiddish culture. Yet, it was enough for the Second World War to end and the USSR to free itself from the Nazis for it to resume its work against “Jewish nationalism”.

In this context, Stalin and his followers began a campaign against Jewish intellectuals, accused of being “stateless cosmopolitans” and being influenced by Western values. These began to be portrayed as traitors, were arrested and, in some cases, executed, such as Solomon Mikhoels. Mikhoels was the director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater and president of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which was murdered in a traffic accident orchestrated by the Ministry of State Security in 1948. After this event, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee reduced its activity and dissolved that same year. Similarly, in 1948, the State of Israel was created, with the support of the USSR, which subsequently became suspicious of the national sentiment that was awakened in Soviet Jews. Consequently, antisemitic policies were tightened: Yiddish radio broadcasts were

terminated, theaters were closed, and Jews were expelled from universities, academies, and orchestras.

Towards the end of the Stalinist era, at the beginning of 1953, within an atmosphere of paranoia and conspiracy, several Jewish doctors were accused of being spies for the United States and Great Britain; and to prepare a plot against the members of the Politburo, to assassinate Stalin. Doctors were subjected to torture to extract false confessions, until, in March 1953, Stalin died of natural causes and the accused Jews were freed, having a profound impact on the Jewish community. Ultimately, it is also worth mentioning the Stalinist purges, which disproportionately affected Jews holding public office. Although the purges did not directly target the Jewish community, numerous members were arrested and sent to forced labor camps. For example, during the Great Purge of 1937-1938, many Jews in the Communist Party, the Red Army, and the Soviet intelligentsia were accused of being traitors and spies and were arrested or executed. In short, Stalin’s period marked a resurgence of an entire campaign of antisemitism: “Although antisemitism as such was prohibited in the USSR, there was persecution, imprisonment and executions of Jews accused of colluding with Zionism, Trotskyism and the democracies of the West” (López, 2018, pp.63-64).

PAGE | 21

The post-Stalinist period (1953-1991)

After Stalin’s death, Nikita Khrushchev took power and became the leader of the Soviet Union, part of his term coinciding with the Cold War. Thus, from 1956 the well-known “Khrushchev thaw” began, until 1964, in which political repression and censorship in the USSR decreased, due to de-Stalinization policies. Thanks to this period, the Jewish community was able to witness the lifting of some restrictions: literary works were published in Yiddish, the Moscow synagogue reopened and there was a rehabilitation process for those Jews who were victims of the purges. Regardless, the arrival to power of Leonid Brezhnev in 1964 marked a setback, since: “The Jewish community was forcibly assimilated and the remains of Yiddish culture began to disappear” (López, 2018, p.66).

Antisemitic propaganda resurfaced and Jews were portrayed in a negative way, associated with Zionism. Zionism, an ideology that proposed the establishment of a state for the Jewish people in Palestine, was linked to the bourgeoisie, which meant that those Jews who showed sympathies towards Israel were subject to antisemitic attacks.

Similarly, the Arab-Israeli conflict, namely the SixDay War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973, exacerbated the Soviet stance against Israel and Jews were viewed with suspicion within the regime. Although many wanted to emigrate to Israel, the migratory movement was prohibited due to the impact it would have, in terms of ideological propaganda, with respect to the image of the USSR as an egalitarian and equitable country. Jews who wanted to emigrate were called “refuseniks”, representing freedom and the ideal of escaping discrimination and restrictions. However, many of them suffered reprisals from the Soviet government, despite international support from human rights organizations and the Jewish diaspora. Therefore, in this context of resurgence of antisemitism, the creation of the state of Israel and new antisemitic policies, it can be stated that Soviet propaganda used criticism of Zionism as a way to justify and cover up antisemitism. In this way, the post-Stalinist period meant comings and goings in policies towards the Jews, with renewed repression that prevented emigration to the State of Israel.

PAGE |22

Nikita Khrushchev

Leonid Brezhnev

Once the forms of expression of antisemitism in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union have been analyzed, it is essential to differentiate the continuities and changes observed between these two periods. When dealing with continuities, it is evident that, at both times in history, antisemitic propaganda and conspiracy theories, distributed through the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, were a constant that encouraged antisemitism, influencing both the Russian Empire as in the Soviet Union. Likewise, violence and pogroms reflect an undoubted continuity and increasing cruelty against the Jewish community. Finally, the institutionalization of antisemitism is evident, as antisemitic policies, restrictions and laws against Jewish rights were maintained. Nevertheless, while it is true that these continuities are relevant, it is also important to address changes. In the case of ideological justification, the Russian Empire used a narrative full of religious and nationalist pretexts, in defense of a pure culture; while the Soviet Union made use of political and economic reasons, as seen in the accusation of “stateless cosmopolitans” and in the relationship with Zionism. In the same way, the creation of the State of Israel introduced into the political debate an issue that had not been present in the Russian Empire: emigration and its control. One of the most important elements of the USSR constitution was the image projected abroad and, ergo, migration had to be prohibited: what would the rest of the countries think if citizens left the USSR? In conclusion, changes and continuities are present when analyzing antisemitism in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. Yet, despite the evolution of forms of expression, the consequences for the Jewish community remain devastating and cruel in both episodes of history. Although antisemitism has adapted to different social and political contexts, its presence and consequences remain the same, despite the passage of time.

PAGE | 23

IMPACT OF ANTISEMITISM AND SHOAH DENIAL

As has been seen, throughout history, antisemitism has had an enormous impact on the life of a community that has not stopped fighting discrimination, marginalization, restrictions and violence. When mentioning the word “impact”, reference is not only made to the social and economic consequences, due to significant losses of assets and limited job opportunities; but also to the psychological impact. Being under constant fear of violence and persecution broke families and broke communities that have never recovered. The scar has remained open all this time, as has the vulnerability and distrust of the “other”. What has happened to Jewish identity? Being objects of human cruelty, the sense of Jewish identity and belonging has completely changed. The development of a collective consciousness, marked by a history of persecution and suffering, has strengthened both ties and tensions within

the community. When facing discrimination, two trends have been adopted: assimilation strategies or identity affirmation strategies as a form of cultural and political resistance. What is the best option to survive? Integrate or separate? This question was, has been and continues to be key in the history of the Jews in Europe.

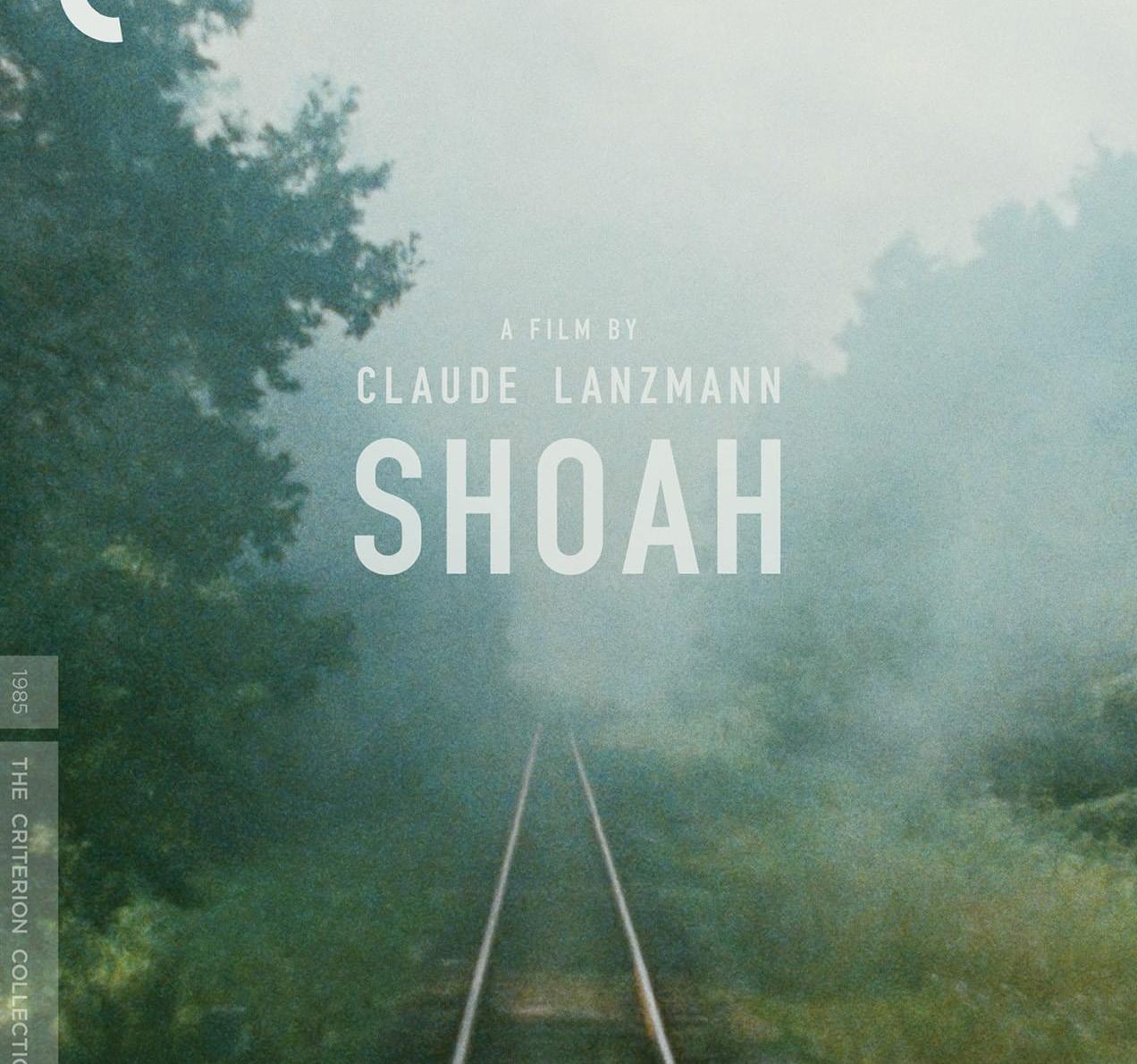

Additionally, the impact of antisemitism on identity is exacerbated by the denial, by authors of various ideologies, of the Shoah and the minimization of the tragedy during World War II. Many authors questioned whether Nazism had implemented systematic extermination policies against the Jews in Europe, giving rise to what is known as “revisionism”. Both authors, sympathetic to Nazism and leftist authors, deny the Holocaust in order to demolish one of the fundamental pillars that constituted the State of Israel. Many of them refute the fact that six million Jews died in gas chambers in the extermination camps and argue that the Shoah was an international plot to deceive public opinion. One of the most controversial left-wing writers has been Paul Rassinier, who began criticism of the Holocaust, interrelating colonialism, capitalism and Zionism. And although he did not take the antiJewish discourse, he chose the anti-Zionist position. That is, he justifies the denial of the Shoah based on the assumption that the Zionist Jews had a single objective: to create a Jewish Empire. The authors have done all kinds of juggling to cover up an extermination, manipulating documentation and covering history with a cloak of silence. However: “The survivors, the mountains of documentation, the very existence of the extermination camps, are eloquent proof of the policy of systematic extermination that the Nazis implemented with the aim of erasing the Jews from the face of the planet” (López, 2018, p.79). Taken together, the impact of antisemitism and Shoah denial have shaped the Jewish community’s experience, identity, and sense of belonging. Both phenomena have shown the need to preserve historical memory and fight against antisemitism from all forms of expression in which it can be shown, in order to vindicate the history of resilience and survival of a community that continues to face this hatred.

PAGE |24

Another fundamental aspect when studying antisemitism in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union is the legacy that it currently has in society. Are human beings aware of all the escalation of suffering that the Jewish community has suffered? The antisemitic legacy remains, even today, palpable in contemporary Russia and influential in the perception of “them” and “us”. The forms of expression of antisemitism and its evolution over time have shaped interethnic dynamics in the country. Negative stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination remain latent in some social sectors, manifested in the form of marginalization and limitation of access to the public sphere and political discourse. Thus, this whole set of factors has influenced the construction of Russian society and its impossibility of becoming inclusive and diverse. Nonetheless, antisemitism is not just a problem in Russia, it is a much more complex issue that concerns the entire world. According to the 22nd Annual Report on Antisemitism from the Center for the Study of European Judaism at Tel Aviv University, Western Jews have suffered antisemitic attacks in cities such as New York and London. In the United States alone, in 2022, 3.697 antisemitic incidents have been reported (University of Tel Aviv, 2023). Therefore, antisemitism is not only a Russian

LEGACY OF ANTISEMITISM IN THE PRESENT DAY

issue, but goes beyond its borders, becoming an issue that concerns the entire society.

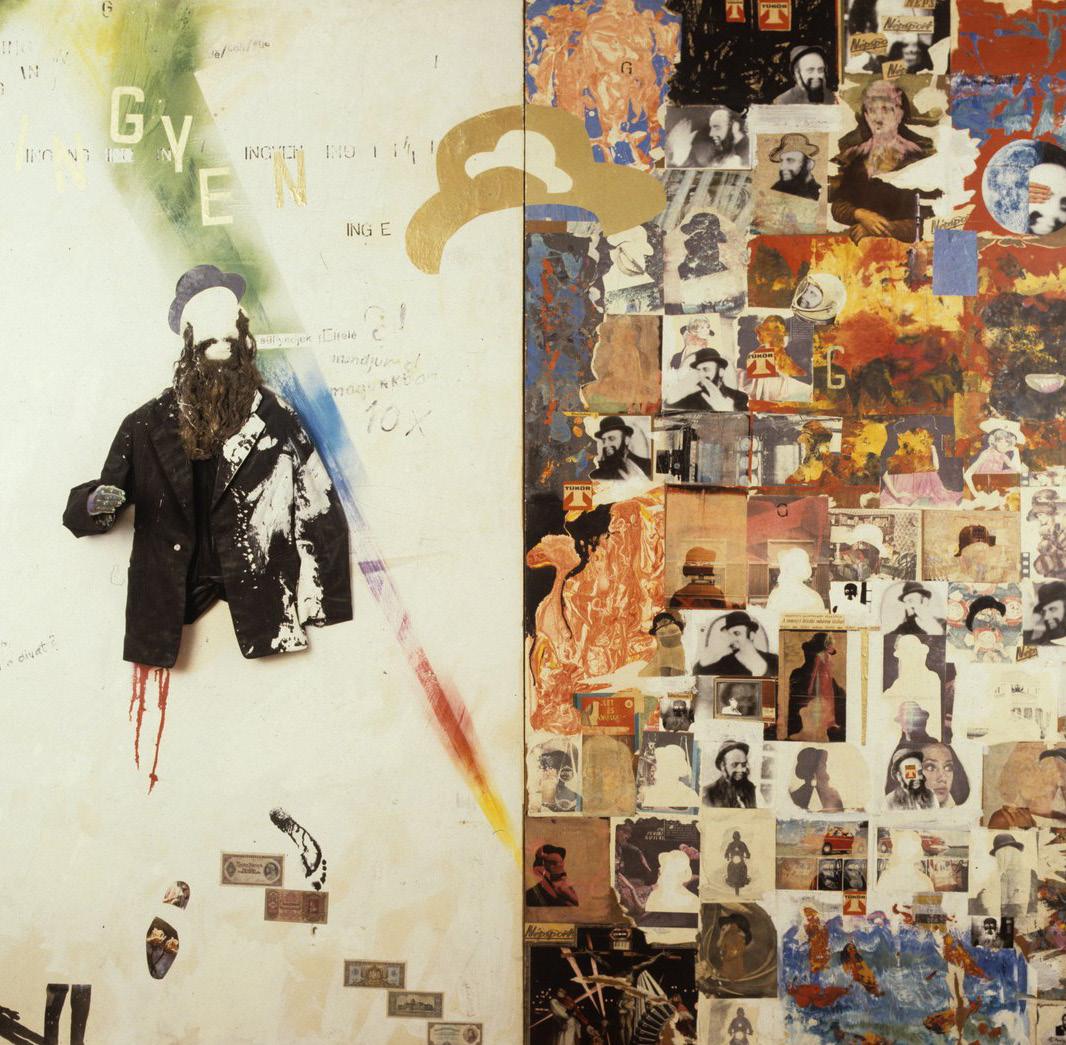

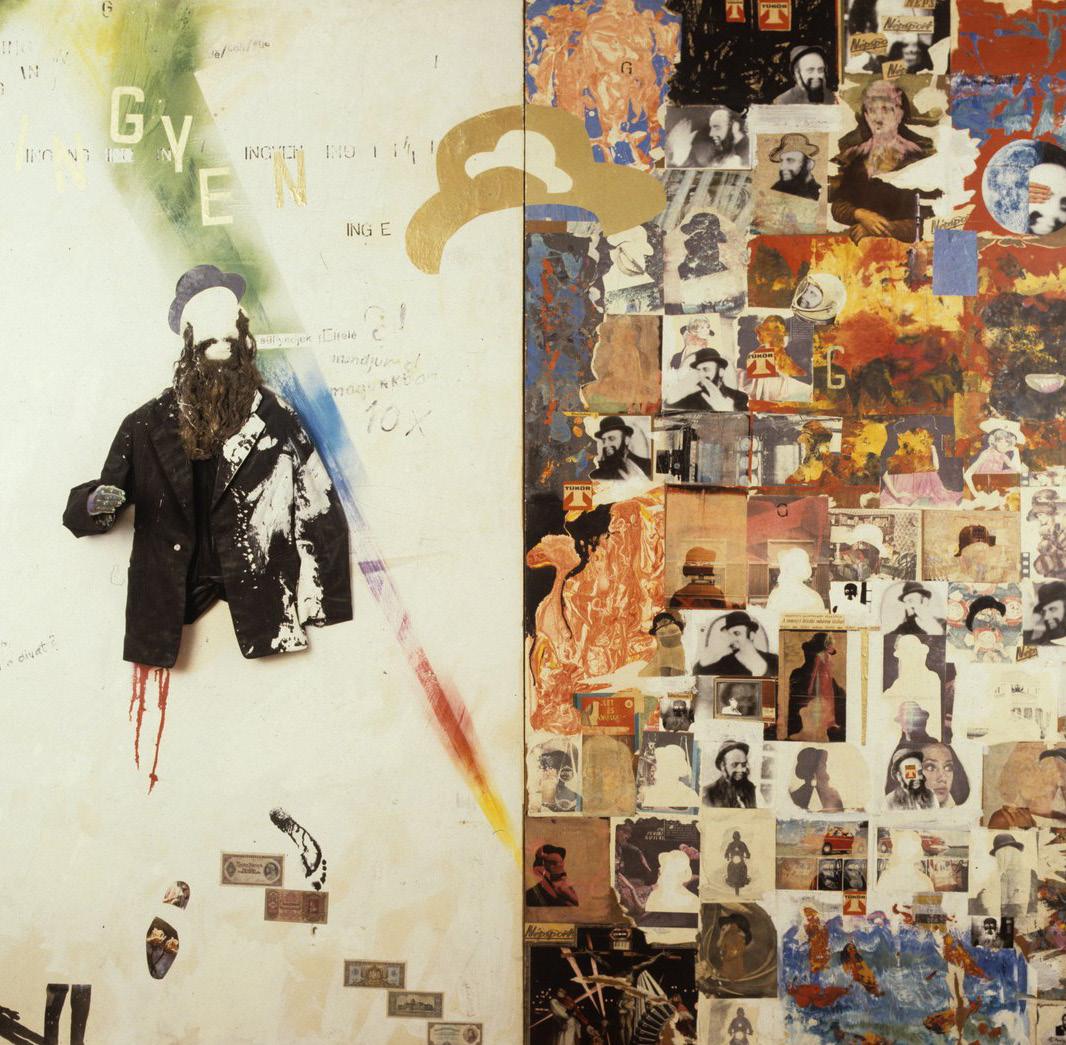

Evenly, the legacy of antisemitism has reached disciplines such as art, from which human beings can reflect on its impact. The Hungarian painter, Sándor Altorjai, knew with complete certainty how to represent, from a unique perspective, antisemitism, in order to show its importance today. In his painting Let me sink upwards, Altorjai suggests an internal and contradictory struggle, showing a metaphor for the tensions and contradictions that arise from the persistence of antisemitism in a society that supposedly aspires to equality and inclusion. The painter challenges the viewer to confront the history and reality of antisemitism, in order to move towards a new society, promoting understanding.

Ultimately, addressing the legacy of antisemitism requires a continued commitment to historical memory, awareness, tolerance, respect, and the elimination of prejudice. For Russian society and world society to move forward, it is necessary to confront and understand this chapter of history, without forgetting it. If the facts are forgotten, we may be condemned to repeat them. Only by giving it the importance it deserves can inclusive societies be built, where the past helps determine the present and the future.

PAGE | 25

After having developed each and every one of the manifestations of antisemitism in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, the absolute complexity of this phenomenon has been demonstrated. From discriminatory policies and pogroms, to antisemitic propaganda, persecutions and the definition of Jews as enemies of the state, antisemitism has sown an entire path of terror and suffering, leaving an indelible mark on the conscience of the Jewish community. Used as a political tool of control and manipulation, exacerbating social divisions and justifying acts of violence against human beings, antisemitism has become a turning point in human history. By reflecting on the past, we can become aware of the resilience of Jews to face, day by day, fear, persecution and unforgettable traumas, always trying to maintain their true culture and identity. By listening to the “voices” of those who no longer have the opportunity to tell their story, we are participants in these events, we are participants in the truth. The evolution of antisemitism in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union underscores the importance of building a society in which the values of diversity, inclusion and respect are the flag that flies over the present and the future. Remembering the echoes of the past and learning from historical lessons reaffirms the commitment to combat discrimination towards a community. Only in this way can the victims of antisemitism and any other type of racial hatred be honored, building a more just and humane world.

Attn: For all those whose voices were not heard.

PAGE |26

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Antisemitism. (n.d.). https://www.yadvashem.org/es/holocaust/encyclopedia/antisemitism.html

Comensoli, C. (2019). Russian Antisemitism in a European Perspective. [Doctoral Thesis, Ca Foscari University of Venice]. Dspace Unive. http://dspace.unive.it/bitstream/handle/10579/16871/870814-1235645. pdf?sequence=2

Definition of Antisemitism by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance - IHRA. (2024, January 31). IHRA. https://holocaustremembrance.com/resources/definicion-del-antisemitismo

Engel, D. (2011). What’s in a Pogrom? European Jews in the Age of Violence. In J. Dekel-Chen at al. (Ed.), Anti-Jewish Violence: Rethinking the Pogrom in East European History (19-37). Indiana University Press.

Eugster, D. (2024, January 24). How Christian Europe created anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages. SWI swissinfo.ch. https://www.swissinfo.ch/spa/cultura/la-europa-cristiana-foment%c3%b3-el-odio-a-losjud%c3%ados-en-la-edad-media/47778164

López Göttig, R. (2014). Soviet antisemitism. Democratic bridge. Fight against Anti-Semitism and Promotion to Religious Tolerance in Argentina. https://www.cadal.org/informes/pdf/El_antisemitismo_sovietico.pdf

López Göttig , R. (2018). Origin, myths and influences of antisemitism in the world. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. https://www.cadal.org/libros/pdf/Origen-Mitos-Influencias-Antisemitismo_Ricardo-Lopez-Gottig.pdf

Mendes, P and Reinharz, J. (1995). The Jew in the Modern World. A Documentary History. Oxford University Press.

Nathans, B. (2002). Beyond the Pale. The Jewish encounter with Late Imperial Russia. University of California Press.

Petrovsky-Shtern, Y. (2014). Golden Age Shtetl: A New History of a Jewish Life in East Europe. Princeton University Press.

Rogger, H. (1966). The Beilis Case: Anti-Semitism and Politics in the Reign of Nicholas II. Slavic Review, 25 (4), 615–629. https://doi.org/10.2307/2492823

Sartre, J.P. (1948). Reflections on the Jewish question. South Editions. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile. php/5840522/mod_resource/content/1/jean-paul-sartre-reflexiones-sobre-la-cuestion-judia.pdf

Segel, B. W., and Richard, S. L. (1995). A Lie and a Libel: The History of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. University of Nebraska Press.

University of Tel Aviv. (2023, 18 April). Antisemitism in the world: year 2022. Gov.il. https://www.gov.il/es/

PAGE | 27