Fall 2021, Spring 2022

Fall 2021, Spring 2022

Each year, Roger Williams University convenes Student Academic Showcase and Honors (SASH) events in April, to share outstanding work by undergraduate and graduate students in presentations, panel discussions and exhibitions. SASH represents our collective intellectual accomplishments as a University during the academic year.

The Cummings School of Architecture has sought to make the most of this event and opportunity, and has created a school-wide exhibition of outstanding work from all courses and levels of study, which is then exhibited in the School’s atrium spaces over the year. This year and going forward, SASH work is also collected into a print and online and print booklet.

The work collected demonstrates the character of teaching and learning here at the School, and is the product of interactive relationships between students, faculty and external partners in classroom and field courses, design studios and course workshops.

Particular thanks to Professors Nathan Fash and Olga Mesa for organizing the collecting the work, and for working collaboratively with Heather Wilson, the Cummings School’s Portfolio and Documentation Specialist.

Sincerely

Stephen White, AIA, Dean

Cummings School of Architecture

Program Directors

Architecture

Art & Architectural History

Preservation Studies/

Preservation Practices

Urban and Regional Planning

Portfolio and Documentation Specialist

Associate Dean

Nathan Fash, AIA, Associate Professor

Olga Mesa, Associate Professor

Randall Van Schepen, Ph.D., Associate Professor

Elaine Stiles, Ph.D., Assistant Professor

Ginette Wessel, Ph.D., Assistant Professor

Heather Wilson

Gregory Laramie, AIA

Dean Stephen White, AIA

Andrea Adams

Edgar Adams

Aleksandra Azbel

Rubén Alcolea

Timothy Bailey

Steven Banak

Mauricio Barreto

Julia Bernert

Julian Bonder

Aaron Brode

Eric Busch

Ginette Castro

Noel Clarke

Bilge Celik

Anthony Corr

Andrew Cohen

Nicole Cuff

Michael Decoulos

Bob Dermody

Keith Doucot

Nathan Fash

Gail Fenske

Nicole Gaenzler

Vincent Giambertone

John Hendrix

Karen Hughes

Melissa Hutchinson

Rich James

Sarah Kennedy

Myoung Kim

Nermin Kura

Gregory Laramie

Kristopher Lawson

Alyssa Lozupone

Ryan Ludwig

Richard McBride

Olga Mesa

Samantha Moscardelli

James Moses

Cynthia Murphy

Xuanyi (Maxwell) Nie

John O’Keefe

Eleftherios Pavlides

Robert Pavlik

Anne Proctor

Marthe Rowen

Christopher Ryan

Blair G. Shanklin

Kellan Simpson

Elaine Stiles

Randall Van Schepen

Hanisha Thirth Bennabhaktula

John Tschirch

Roberto Viola Ochoa

Kristen Weigel

Ginette Wessel

Melanie Weston

Stephen White

Junko Yamamoto

Dingliang Yang

Tyrone Yang

Leonard Yui

Fall 2021 Teaching Firms: Schwartz/Silver Architects

Peter Kleiner, AIA

Warren Schwartz, FAIA

Jon Traficonte, AIA

VARI Design

Dingliang Yang, Principal

Xuanyi (Maxwell) Nie

Spring 2022 Teaching Firms:

Maryann Thompson Architects

Maryann Thompson, FAIA

Jeff Vogel

Hacin + Associates

David Hacin, FAIA

Matthew Manke

Joshua Lentz (M.Arch’12)

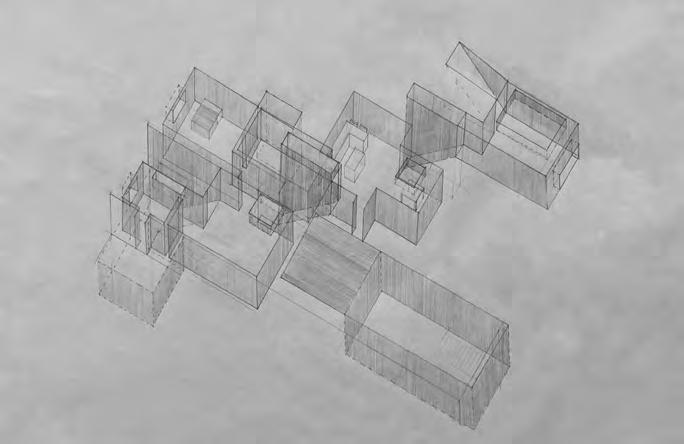

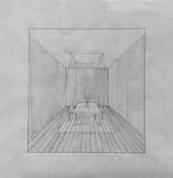

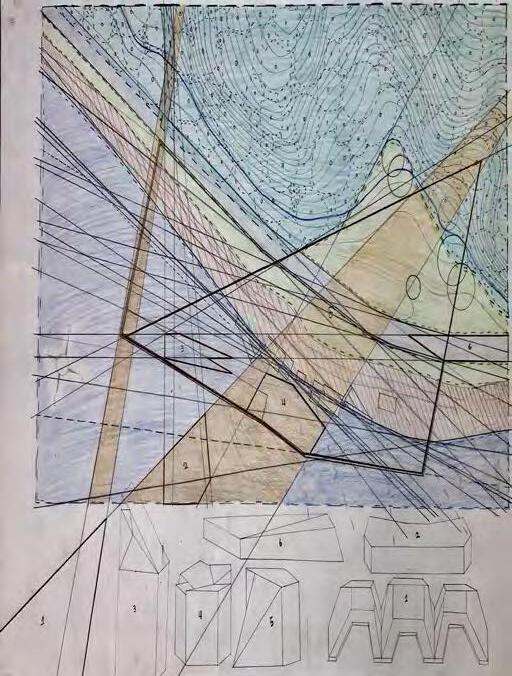

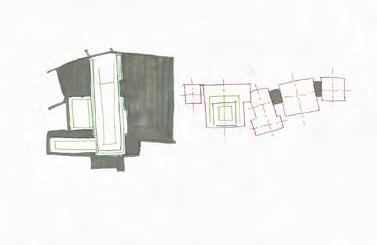

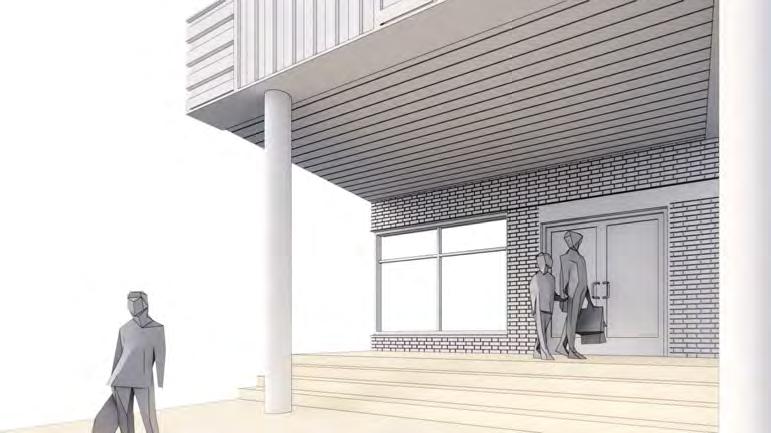

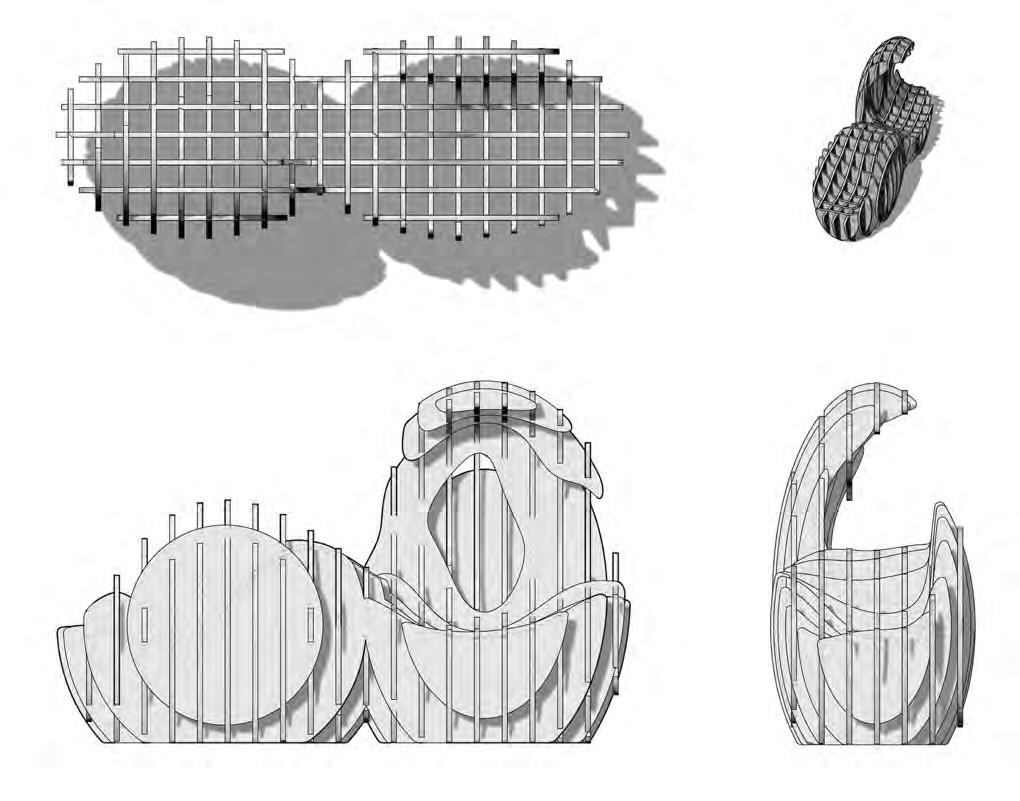

The Core Design Studios introduce students to the fundamental design concepts and principles necessary to develop a variety of projects that range in scale and duration. Students begin to form a vocabulary for making spaces and forms that includes human scale, proportion, site, structure, enclosure, materiality and typology. Students are asked to generate a point of view by considering a number of ethical issues that affect their work and its relationship to the communities they are designing for. And lastly, students learn the variety of skills necessary to make and communicate their ideas.

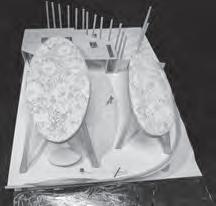

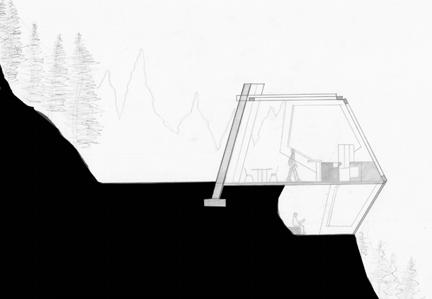

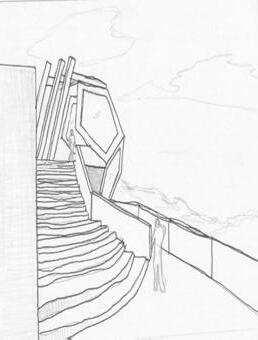

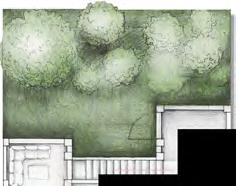

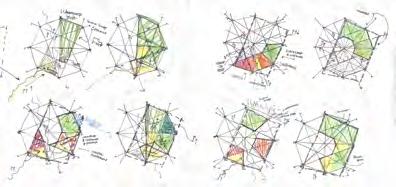

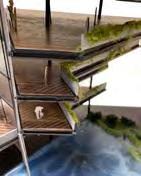

This project is located on the westface of a mountain. It is designed so that the majority of the views look to the west. The intended use of the space is for a family or other group to be able to gather, cook, eat and congregate together. The inspiration for the pavilion came from the star fruit. In the abstractions that preceded this design, the pentagon was the dominant geometry derived from the fruit. The supporting elements of the landscape utilize the same angle contained in the pentagon. Upon arrival at the pavilion the guest is presented with the choice between going to the upper or lower area of the structure. The lower area has been carved into the landscape creating a cave-like space. Its purpose is to afford the guest an area to take in the view from a unique perspective with the walls angled out from the ground giving the occupant the sense that they are suspended off the side of the mountain. The upper portion of the structure includes a cooking space with a large island and a covered dining area. On the outside of the pavilion there is another large table allowing flexibility between indoor and outdoor dining.

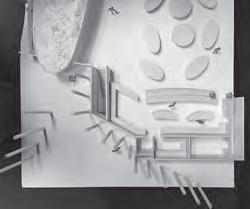

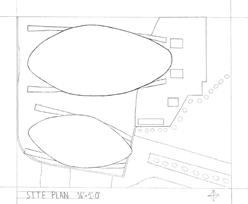

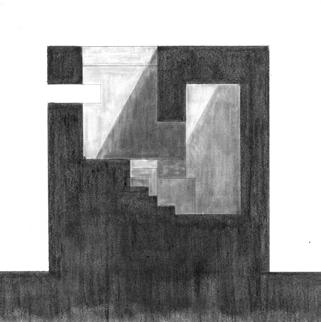

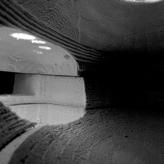

To think about the given site plan, “Perpendicular Cut,” three-dimensionally, I created a concept model. I overexaggerated the height of the island and discovered that, rather than being a solid flat mass, the island could be a huge, rocky cave with two entrances which I could build inside. The pictures above show my island design in a harsh, jagged style to match the harshness of the rocky cliff faces surrounding the island. Below are some concept sketches in which I interpreted the mood of the space. Some

ideas expressed

include solitude, enclosure, rise, light, and darkness.

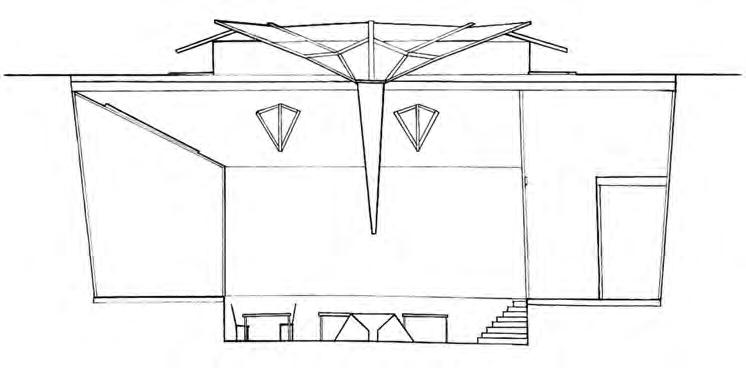

Because of the two-layered nature of this proect, two models were needed to adequately represent the space. The first is a 1/40” scale model of the whole island, which opens up to reveal the inside. The second is a 1/8” in scale model of the kitchen and dining building, which is the first to break through the surface and exist in both open air and subterranean space.

To take advantage of the various unique conditions created by the island’s shape, my design is separated into three distinct interior spaces. These spaces cling to the cave walls and are joined by a staircase which ascends from sea level to the open air. As we climb this staircase, the spaces transition from public spaces open to guests to more private, intimate spaces meant for only the residents. Each space is a cluster of geometric, crystallike forms, making the island’s interior resemble a geode. Following this theme, the windows of each space are one-way mirrors.This means that the small amount of light let in by the two openings and a large crack in the cieling bounces off the water and the buildings, creating a sparkling interior.

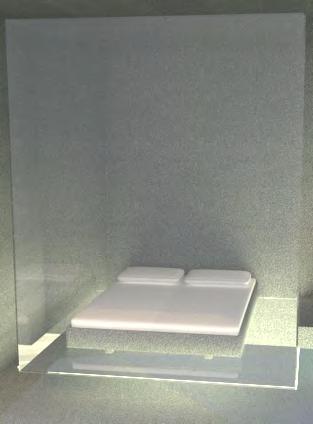

The first cluster of rooms is a public multipurpose space meant to entertain guests as well as be used recreationally by the residents. This includes a game room, a library room, and a guest suite. The second space is for cooking and eating. Because this island residence is so remote, it’s important to give the space some degree of self sufficiency. The kitchen has an attached greenhouse which takes advantage of the room’s large windows and skylight, as well as a large pantry beneath the kitchen for food storage. Attached is a more formal dining room with a bar for large gatherings. The third building includes a bright, naturally lit bedroom with a view of the sunrise, with a private study downstairs.

A continuation of the Core Design Studios which introduce students to the fundamental design concepts and principles necessary to develop a variety of projects that range in scale and duration. Students begin to form a vocabulary for making spaces and forms that includes human scale, proportion, site, structure, enclosure, materiality and typology. Students are asked to generate a point of view by considering a number of ethical issues that affect their work and its relationship to the communities they are designing for. And lastly, students learn the variety of skills necessary to make and communicate their ideas.

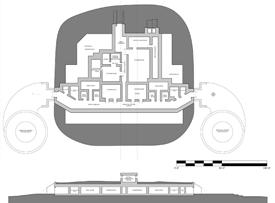

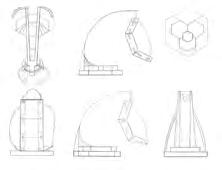

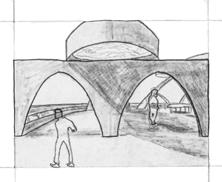

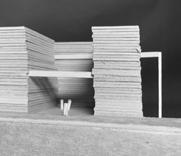

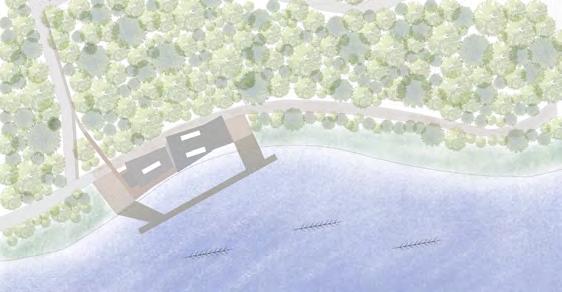

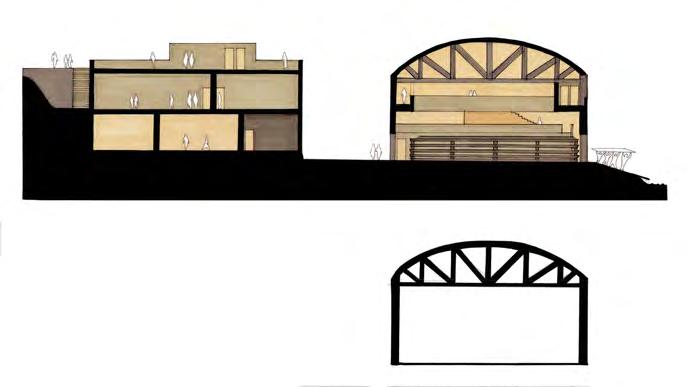

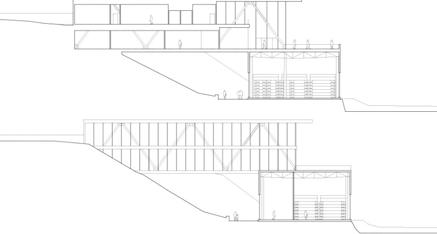

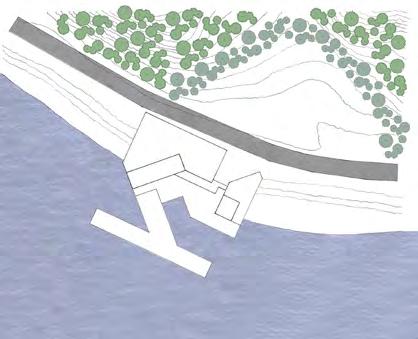

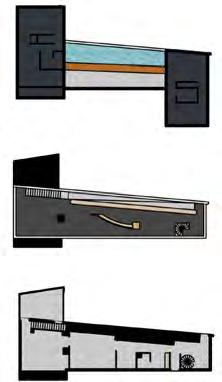

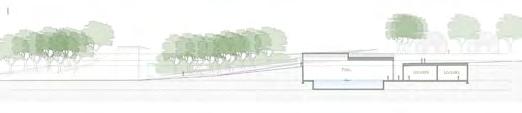

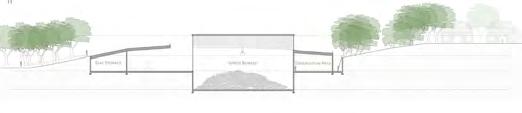

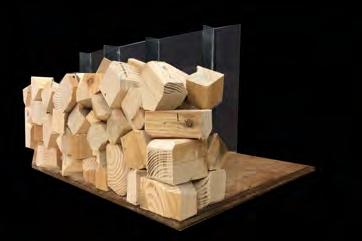

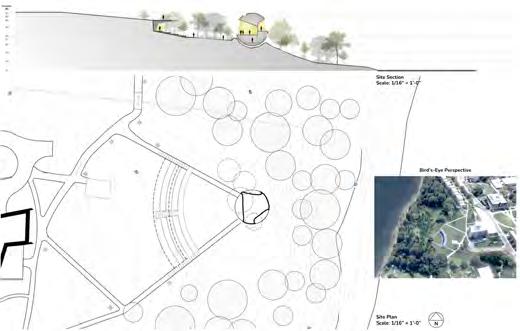

NARRAGANSETT BOAT CLUB IS A BOATHOUSE FIT FOR BOTH PUBLIC AND PRIVATE USE, SEPERATED PROGRAMATICALLY INTO THREE HEAVY TIMBER STRUCTURES WHICH SIT ATOP A CONCRETE BASE. FISSURES CUT THROUGH THE EARTH JUST AS OARS CUT THROUGH WATER, EMBRACING RISING TIDES AND ALLOWING THE RIVER TO FLOW UP AND INTO THE STRUCTURE. GLASS BREEZEWAYS PROVIDE CIRCULATION BETWEEN THE THREE MAIN STRUCTURES AND THE OUTDOOR DECK AREAS THAT LOOK DOWN INTO THE FISSURES AND OUT TOWARD THE RIVER.

At first glance, these three projects seem to have nothing in common, but after evaluating their processes is where a similarity begins to emerge. The Heartbeat was based on analyzing the characteristics of the line produced by a heart rate monitor. These were then implemented into every aspect of the structure. Light Source was composed based on a polar planimeter’s range of motion. After breaking the motions down and overlaying them on one another, I was given the forms in which the lamp was constructed. The PinkHouse came about from a plan of Site A. By analyzing the sequence of thresholds within the landscape, I was able to pick out six different forms that I felt fit the function of each room in the facility.

Each project had its respective subject matter, but the process of turning these subject matters into buildings is similar. Through a long process of researching and analyzing the subject matter, it allowed me to get a better understanding of the ideas I worked with. This was done by breaking down each characteristic in a way that created a clearer understanding of how its components coincide with themselves. I was then able to put these pieces back together to form my project, whether it be the first, second or third project.

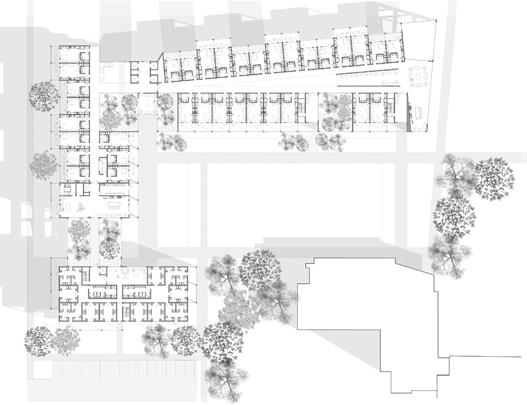

Multi-Generational Housing

Located in the Historic French Quarter of New Orleans, this multi-generational housing complex allows for the mingling and engagement of varying age groups while providing ample ADA access and entertainment spaces. The lively and exciting street scape of New Orleans has been curated and constructed within the central courtyard to provide and foster a greater sense of community and interaction. The structure begins to step back as it rises, thus creating a series of terraces to open up the central space and incorporate a greater sense of integration

Composed of 17 units, retail space, a gallery, library, and restaurant, the structure invites both the residents and the public to mingle in a common area while providing exciting opportunities to merge and intersect. Balconies and terraces produce planted spaces, communal areas, recreation sectors, and nodes of interaction in which those of all generations can share stories, ideas, and dialogues.

Materials and Assemblies I | FALL 2021

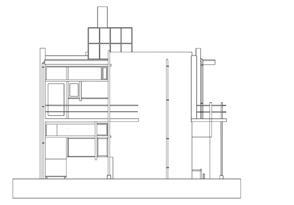

Gerrit Rietveld’s Schroder House was built in 1924 for a recently widowed woman, Truus Schroder, and her three kids. Rietveld was a furniture designer and was unconventional in his design of the house; It is known for its unusual layout and forms. Its dynamic elements allow for spaces to become dynamic and interchangeable.introduced sliding partitions that could be moved in order to create privacy or openness on the first floor. He also uses the same techniques to create fluid transitions between the exterior and interior spaces.

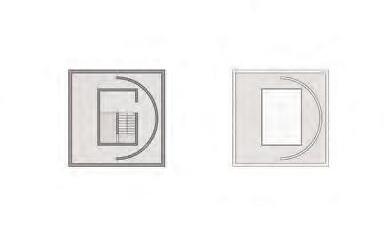

Following the De Stijl movement, the house features vertical lines and planes,

contrasted with horizontals, and accented with primary colors which were placed on structural elements. It is balanced, and asymmetrical in composition allowing no single element to dominate the design. By means of protruding, relieving, hiding, and exposing specific components, Rietveld creates an abstract design that becomes machine-like. The building is configured with a staircase at its core creating a centralized plan. The staircase thus influences the circulation which spirals inward on the ground floor and then outward once at the first floor.

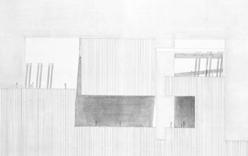

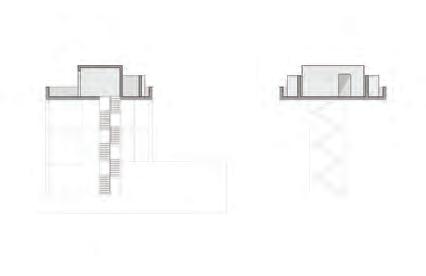

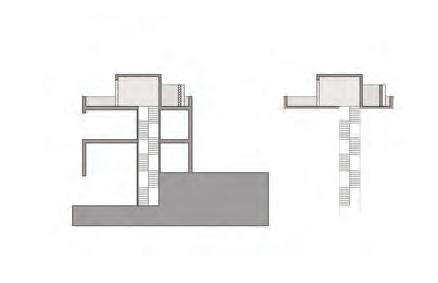

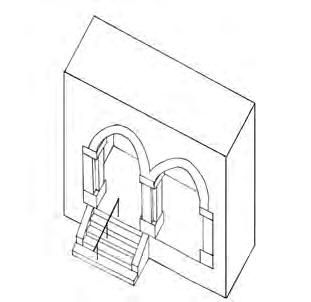

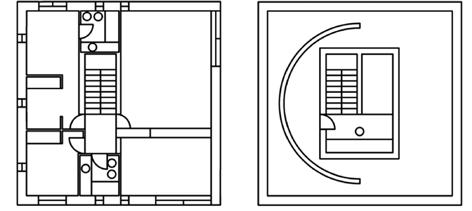

UNGERS’ “HOUSE WITHOUT QUALITIES” WAS DESIGNED TO EXPERIMENT WITH THE REDUCTION OF ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS AND QUESTION THE NECESSARY QUALITIES OF A HOME. BASED ON CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE, UNGERS FOCUSES ON CREATING AN ORDERED STRUCTURE THAT STEMS FROM GEOMETRY AND PURITY. THE RECTANGULAR PLANS AND SEEMINGLY SIMPLE DESIGN OF THE HOME PLAY WITH THE IDEAS OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SPACES THROUGH DOUBLE HEIGHT SPACES, BALCONIES, AND HIDDEN ROOMS. THESE HIDDEN ROOMS REFER TO THE PRIVATE FUNCTIONS AND CIRCULATION ROUTES OF THE HOME, SUCH AS BATHROOMS, CLOSETS, STAIRCASES, AND AN ELEVATOR, ALL OF WHICH ARE UNDISCLOSED INSIDE OF THE WALLS. UNGERS’ DESIGN REFLECTS THAT OF MEDIEVAL CASTLES WHERE PRIVATE CHANNELS AND SERVICE FUNCTIONS ARE SEPARATED FROM PUBLIC SPACES, KEEPING MATERIALS OR ROOMS UNEXPOSED. THE CLEAR ORGANIZATION AND PURPOSE OF UNGERS’ DESIGN CAN BE SEEN IN ALL ELEMENTS OF THE HOME, EXPRESSING HIS INTENTIONS OF GEOMETRY, PURITY, AND LACK OF TRADITIONAL RESIDENTIAL FEATURES.

PLANS, SECTIONS & ELEVATIONS

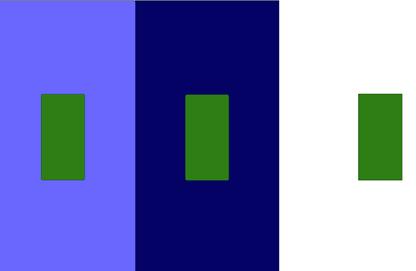

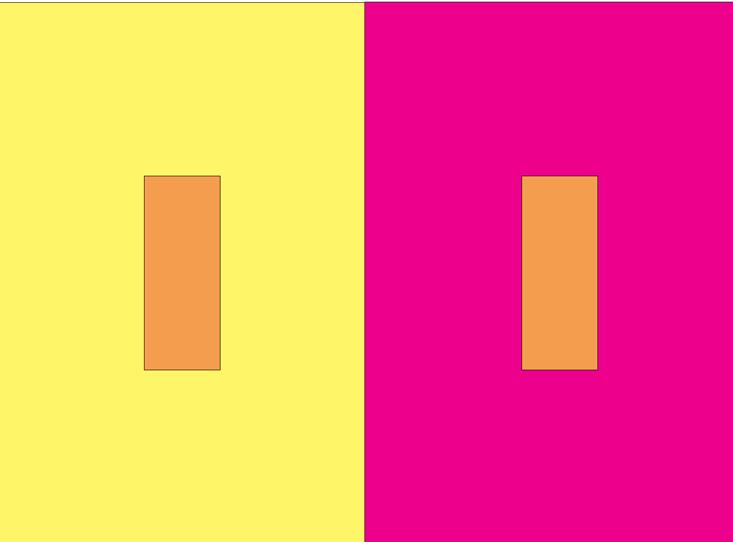

The green color is placed in the middle of two colors that help manipulate the green color to look like the other one. The green square on the left has more blue under tones compared to the green on the right which was more yellow undertones, overall contrasting with its background.

The pink color is placed in two different colors. The lighter blue makes the pink appear darker while the darker hue of blue makes the pink appear brighter and lighter in color when in reality, they are the exact same color.

A5-PART 2:

2:

Two blocks of colors are joined in the middle to create a balance third color. The use of two completely different colors create a perfect sense of balance so that no tone is being over powered. It can be seen in the blue and pink combination that the middle colors not overpowered by either color. Same goes for the yellow and blue combination. There is not an overpowering sense of blue nor yellow, both are perfectly balanced.

A1-PART 3:

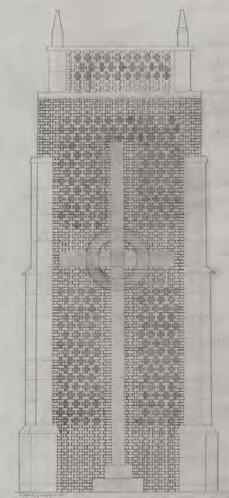

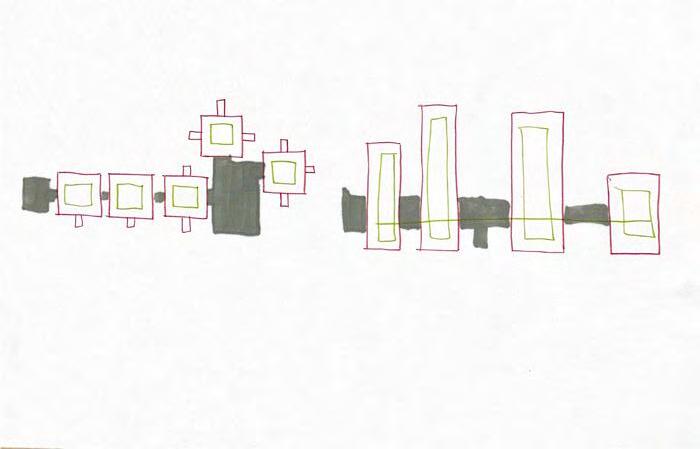

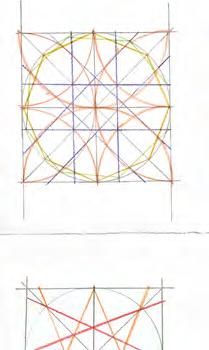

Simple lines and shades were created to help distinct circulation, hierarchy, geometry, and symmetry. The combination creates art within itself as well as identifying its key components. The shapes from diagramming create patterns and play off each other to create rhythm and movement.

A5-PART 2:

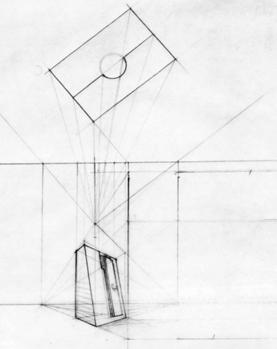

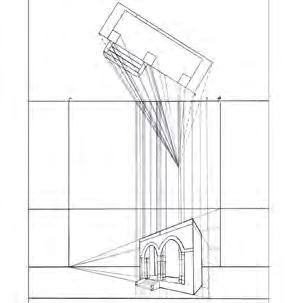

PERSPECTIVE DRAWINGS

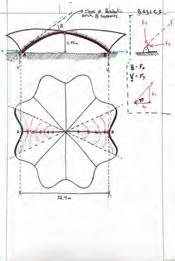

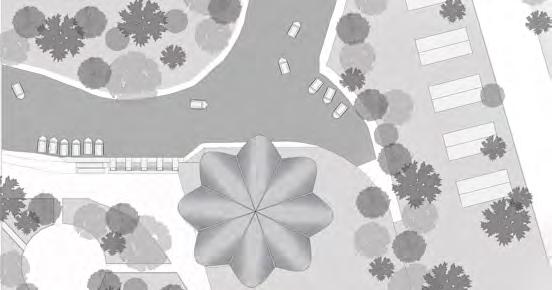

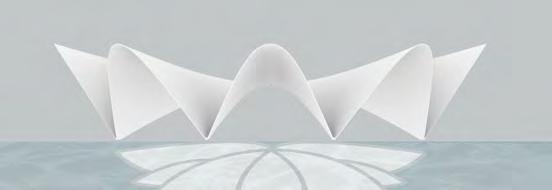

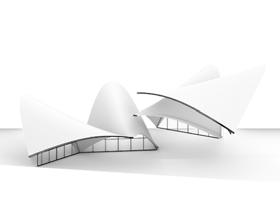

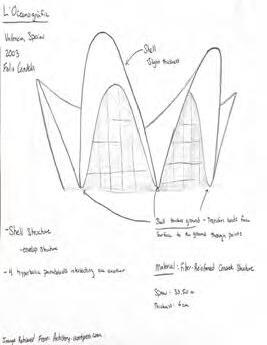

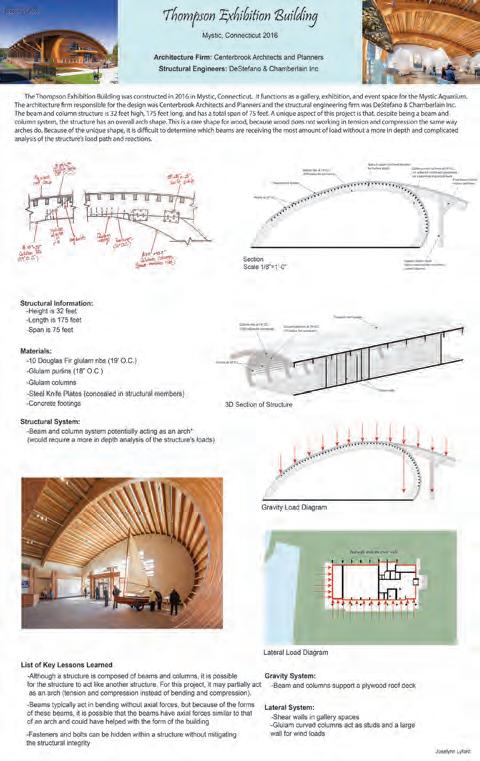

Manantiales by Felix Candela

Concrete became an increasingly popular building material during the Spanish Civil War. This was due to the fact that it represented modernization and efficiency. During the mid- 1950s Joaquin and Ferdanadp Ordonez proposed to Candela to design a restaurant for the Centro Asturiano en Calzada de Tlalpan.

The structure created a replacement for another wooden restaurant that had burned down previously. He decided to start creating full scale experiments through engineered thin shell structures.

The citizens in the city of Xochimilco refer to the structure as “La Flor”

(the flower). The system of the building is hormonally sound between the outer shell and the surrounding floating garden. It is also formed by interesting hypars with a thin roof structure that creates a dramatic open space for the dining area

The shape of each of the petals is considered a Hypar Vault; together, they form groined vaults. In this shape, forces from the weight of the form travel to the groins. These groins take the forces, and redirect them towards the supports in a similar way a standard arch would. This force acting on the support is at an angle, and therefore generates a horizontal and vertical force.

Candella performed and validated his calculations with the 3 hinged arch model, alongside ‘membrane theory for hypars’ (which he developed). after a computer analysis (which takes into account all possible forces and reactions), that the x component of the resultant forces is less than previously estimated. The reason is because of the form. The overhangs create forces that act in the opposite direction to the other horizontal forces, cancelling some force out making the resultant less magnitude. For these reasons, Candella was able to produce a wildly fluid form out of concrete, with an extraordinarily thin shell.

A continuation of the Core Design Studios which introduce students to the fundamental design concepts and principles necessary to develop a variety of projects that range in scale and duration. Students begin to form a vocabulary for making spaces and forms that includes human scale, proportion, site, structure, enclosure, materiality and typology. Students are asked to generate a point of view by considering a number of ethical issues that affect their work and its relationship to the communities they are designing for. And lastly, students learn the variety of skills necessary to make and communicate their ideas.

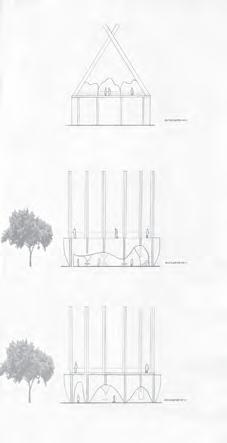

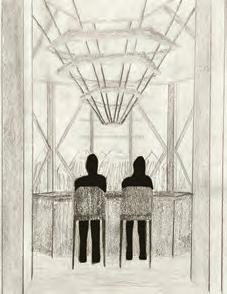

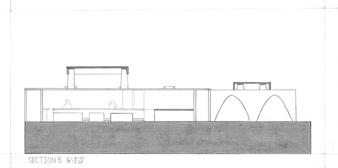

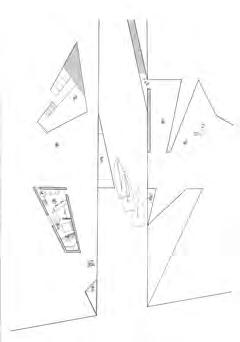

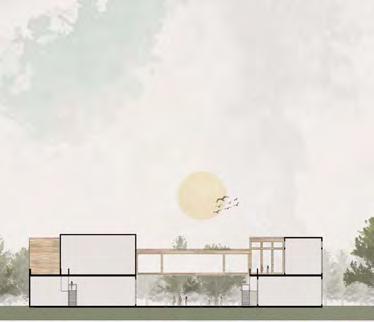

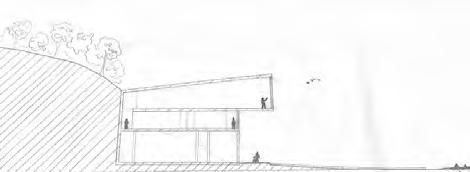

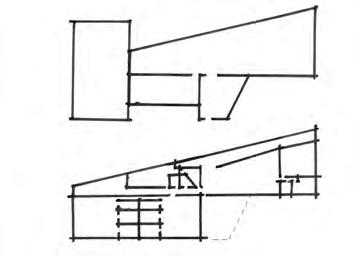

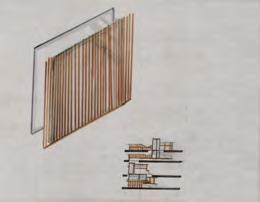

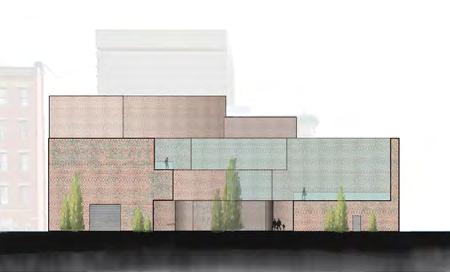

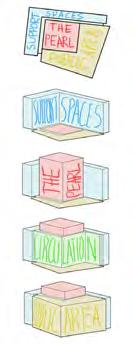

My performance center focuses on designing playful spaces that are engaging for kids and adults as well. The performance spaces are like a hidden pearl, cradled by the support spaces and public areas by acting as the shell. It functions as the core of the project and the object of fascination for children to discover. Creating a clear division between support spaces, public, and performance areas will demonstrate my parti. Lastly, the exterior plaza is included to provide a space for kids to release their youthful energy.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Corbusier, Le, and Willy Boesiger. Le Corbusier: Last Works. New York: Praeger Pub., 1970. Donadio, Rachel. “Le Corbusier’s Architecture and His Politics Are Revisited.” The New York Times. The New York Times, July 12, 2015. https://www. nytimes.com/2015/07/13/arts/design/le-corbusiers-architecture-and-his-politics-are-revisited.html. Ferleger, Brades Susan, Muriel Walker, Michael Raeburn, and Victoria Wilson. Le Corbusier Architect of the Century. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1987. Frampton, Kenneth, and Roberto Schezen. Le Corbusier: Architect of the Twentieth Century. New

(1887-1965)

Course: ARCH 322.01 Theory of Architecture

Work by: Abigail Arruda

Professor: John Hendrix

Use of computer programs distances us from the link from our hands to our minds, and asks little of us. The speed of the computer eliminates the processes of exploration and decision-making in design. Computers do not allow enough time for a design to be thoroughly thought out. They do not allow for the pleasurable process of design development connecting the hand, eye and brain. The computer does not reveal potential flaws in the design. Buildings designed on the computer can be inappropriate for their site, functionally inefficient, difficult to construct, over budget, or ugly. Unfortunately the computer serves the current image-dominated approach to architecture made necessary by media. In this screen capture of Instagram, seven of the fifteen images were created on a computer. Often the computergenerated image is not accurate to the architecture. Computers can be detrimental to designs and the design process, but architecture in the twenty-first century requires reliance on the computer. It is unavoidable in the higher education curricula of architecture programs to use a computer for architectural drawings or renderings. As technology advances and the modern world continues to change daily, computers are more and more involved in our lives. The question about the advantages and disadvantages of computers continues every day in our society.

Images left from Pinterest

Course: ARCH 322.01 Theory of Architecture

Work by: Cora McComiskey

Professor: John Hendrix

ABSTRACT

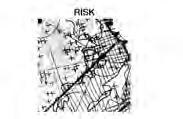

As students, we are to present deep analyses of site conditions and environmental studies as a prelude to the design process. I have spent many hours researching urban contexts and analyzing surrounding buildings, traffic patterns, and census data (as in the image). This information is important, but basing a design solely on the conditions from the current point in time– or really any point in time preceding the present– creates an architecture of staticity. In a period of six months, the neighboring businesses may be leased. In five years, there s the potential for a new infrastructural system. In twenty years, there is a possibility that the entire context has changed or, in an extreme case, no longer exists. And yet, if the design conforms to the conditions of the present, it fails to meet the conditions of the future. This possibility of rapid change is not theoretical, but has been actualized in many instances in the past. Instead of designing for the present– for the conditions that we know and understand at the current point in time– we should design in anticipation of the future. The change is not limited to external context. The occupant turnover in certain types of buildings–mainly commercial or residential– tends to be high in relation to the building’s lifespan. Environmental-based responsive architecture should not be confused with sustainable architecture. Storing rainwater, fixed solar panels, and recycling greywater are methods of sustainable architecture, and these methods are fixed, static. Environmentally responsive architecture tends to include stimuli-based sensory technology that influences the positions of mobile elements. While its impact on the human is unmatched, the flexibility of responsive architecture is crucially important when it comes to the environment. Responsive architecture is the “new” sustainable architecture, but instead of being tied to a singular condition, responsive architecture has the ability to learn and to adapt.

Course: ARCH 322.01 Theory of Architecture

Work by: Jenna Salisbury Professor: John Hendrix

Course: ARCH 322.02 Theory of Architecture

Work by: Jordan Peck Professor: John Hendrix

ABSTRACT

Historically, architecture has told us a great deal about humanity, from the Great Wall of China to Robert Venturi’s manifesto Learning from Las Vegas, which illustrated the architecture of signage that helps to give relevance to the destinations that surround us. Architecture has always had a defining trait in its imitation of nature’s shapes, mathematical formulas, and geometries, embodied in a range of earthly materials and their interaction with physics. Architecture’s journey through time is made up of a mixture of two things: the art and culture of the period, and a term called flotsam. Flotsam is the floating remnants of the past to remind us of what human life used to be, and the world that we have built is one big palimpsest, or layers of traces of the past, of the architectural ideas we believed would add something more to our lives. Architecture is a man-made reflection of the zeitgeist of the present era: what human life is and needs during that place in time. The universe is

Syncretism and Eclecticism in Architecture

Course: ARCH 322.02 Theory of Architecture

Work by: Alessandro Pinto

Professor: John Hendrix

ABSTRACT

Syncretism in architecture occurs through the mixing of foreign architectural forms and elements with the local architectural forms and elements. Eclecticism is a nineteenth and twentieth-century architectural style in which a single piece of work incorporates a mixture of elements from previous historical styles to create something that is new and original. One example is the Basilica of the Sagrada Família in Barcelona, designed by Antonio Gaudí. La Sagrada Familia utilizes three-dimensional forms of ruled surfaces, including hyperboloids, parabolas, helicoids, and conoids. Gaudi embedded religious symbolism in each aspect of La Sagrada Familia, creating a visual representation of Christian beliefs. Another example is the NeoGothic Church of St. Clare in Horodkivka (see image). This architecture is unusual for Central Ukraine – an intertwining of Romanesque and Gothic styles with a combination of natural stone with red brick. The Church of St. Clare was constructed by Polish builders, together with inhabitants of the village and the neighboring village of Zherdeli. It was constructed in an eclectic style with elements of neo-Gothic and modern twentieth-century architecture. For architects, there are often requests to do the seemingly impossible task of creating a cohesive design that incorporates two or more different design aesthetics. When mixing architectural styles, an easy strategy could be to make one style the primary aesthetic and the other a supporting one. In terms of the Pareto principle, also known as the 80/20 rule mixing styles, this strategy makes the primary style represent 80% of the design while the other style represents 20%. The need to blend two design styles elegantly is most apparent when renovating a house or creating a home addition. Another great strategy to blend architectural styles is to follow the “less is more” approach. Pare down the design styles to their most basic principles and make a design with those principles in mind. More than likely, the two styles are considered to have innate similarities. Find those similarities and turn them into the project theme.

superstructure would be attached to the columns, and the angels holding the canopy would help to aid in the visual ambiguity of the baldachin’s support system. Not only was this a great solution between the two architects, but it also showed the collaboration and partnership that was present during this time period. The bronze columns that Bernini constructed sit on marble pedestals that bear the Barberini bees on the outer faces. The presence of the papal escutcheons was highly representative of the ideas of patronage in this time. Bernini also emphasized the power of the pope by implementing the crossed keys of Saint Peter and the papal tiara as draped with a decorative cord. Such a design intertwines the pope with Christ, creating a substantial statement of power on behalf of the pope. The Baldacchino’s imposing structure reinforced the ideas of the Counter Reformation, and the Barberini bees established the power of the pope, both on a familial and institutional level. With its ornate detail, massive scale, and Christian messaging, it is unsurprising that this was one of the great works of the Baroque.

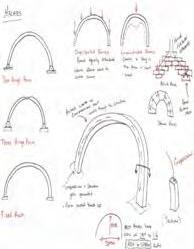

I.APPLE CANTILEVER — Partnered with Luke Strand Challenged to design and build an efficient, elegant structure to support an apple 16” off the table at a distance of 16” from any base elements.

II.TAXONOMY — CYLINDRICAL SHELLS AND VAULTS — Partnered with Luke Strand Present structural attributes of the system and demonstrate its form and how it behaves.

III.HORIZONTAL FRAMING SYSTEMS

To understand components of steel, wood, and concrete horizontal framing systems and practice drawing structural systems of each.

IV. BEAM DESIGN CHALLENGE — Partnered with Luke Strand Challenged to design, construct, and load test a 24” beam made from only chipboard and glue.

V.STRUCTURAL SKETCHES

To create 28 different, original, annotated sketches, by hand while practicing analysis skills and developing a robust structural vocabulary.

THE COURSE: Introduces the fundamental concepts of structural form and behavior through a combination of lectures and studio exercises. Basic structural forms and their taxonomy will be studied in nature and through history, using visual presentations, readings, and handson experiments. Load paths and basic load tracing through common structural systems will be investigated. An introduction to vector-based force representation will also be covered as a continuation of topics covered in Physics. In addition, the students’ studio projects will be utilized for assignments. The development of a strong structural vocabulary will also be stressed.

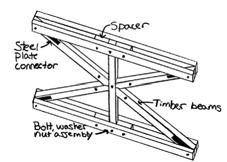

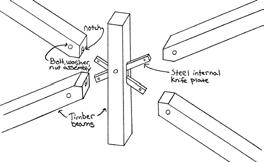

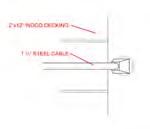

VI.STRUCTURAL CASE STUDY — Partnered with Luke Strand To construct a scale model of the structural system (of the Thorncrown Chapel, E. Fay Jones) to demonstrate its load paths and structural behavior.

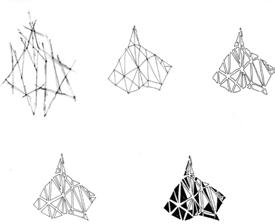

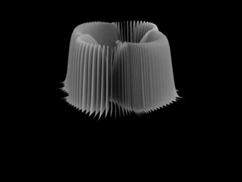

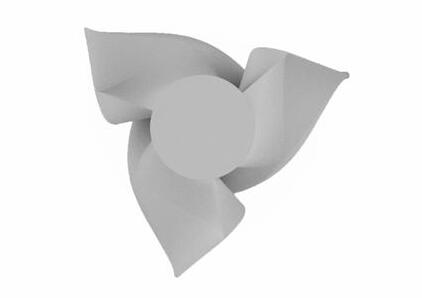

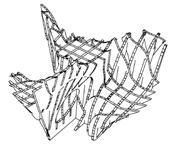

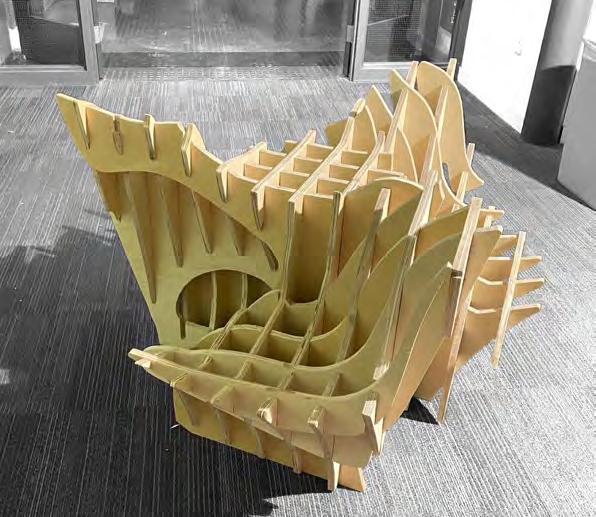

Queen of the Curve; Islamic Calligraphy Influence Lindsey Hansen and Dominick Stanco

This research explores Islamic calligraphy and its relation to Zaha Hadid’s work. As an architect born in the Middle East in Iraq, Hadid’s artistic training as a painter and calligrapher provided great inspiration for her designs. Some of the foundational principles of Islamic art, such as geometry, and the art of penmanship, both engaging linear and spatial dynamics, are prominent visual characteristics of Zaha Hadid’s signature style. Through the analysis, of a number of case studies, this paper discusses how particular letters from the Arabic alphabet, and various styles of Arabic script have been translated into architectural form, in Zaha Hadid’s buildings.

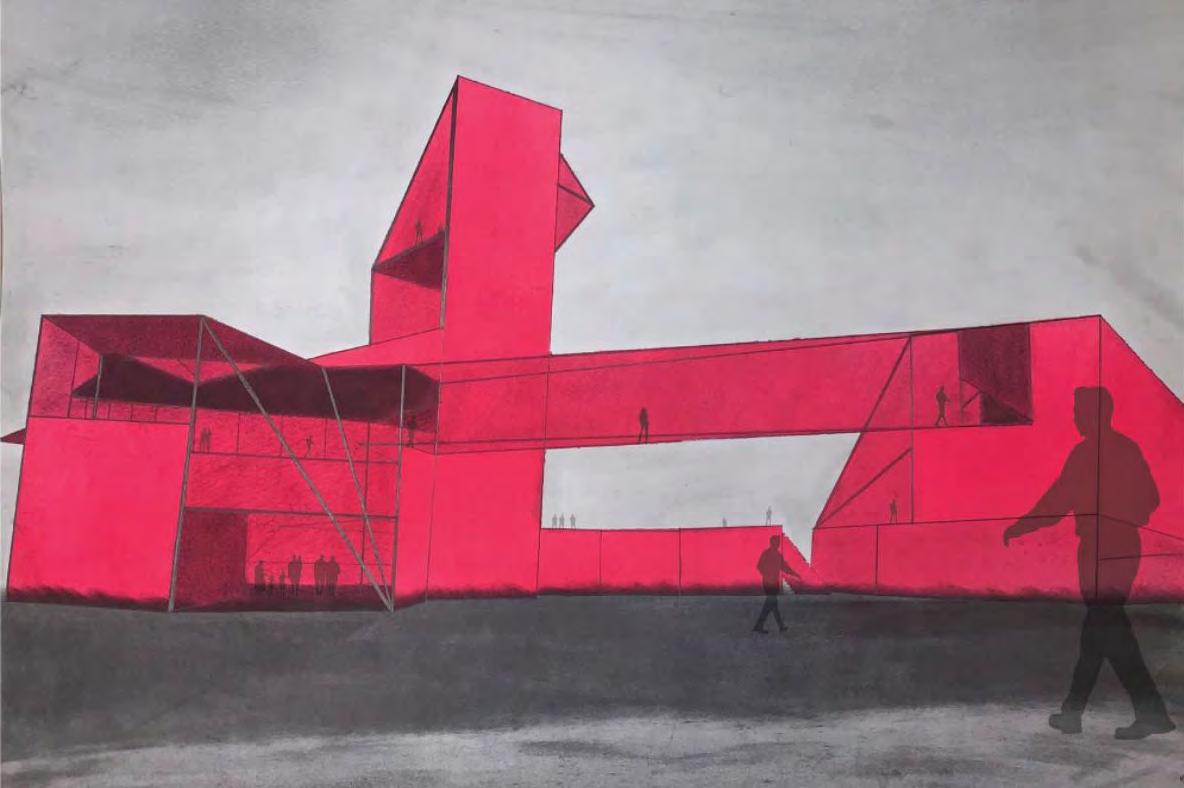

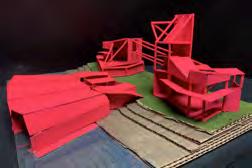

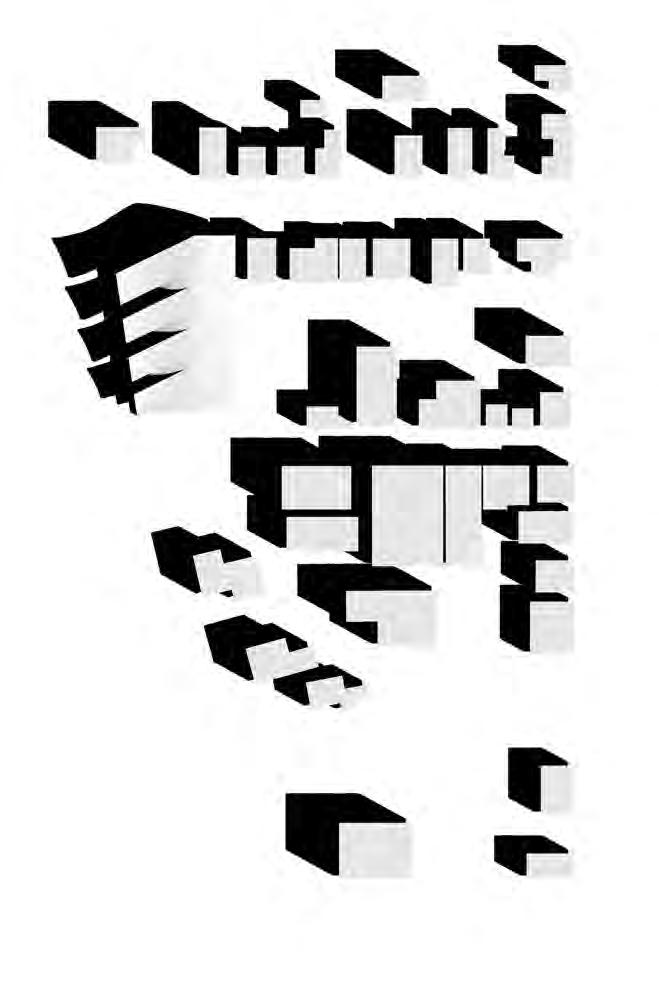

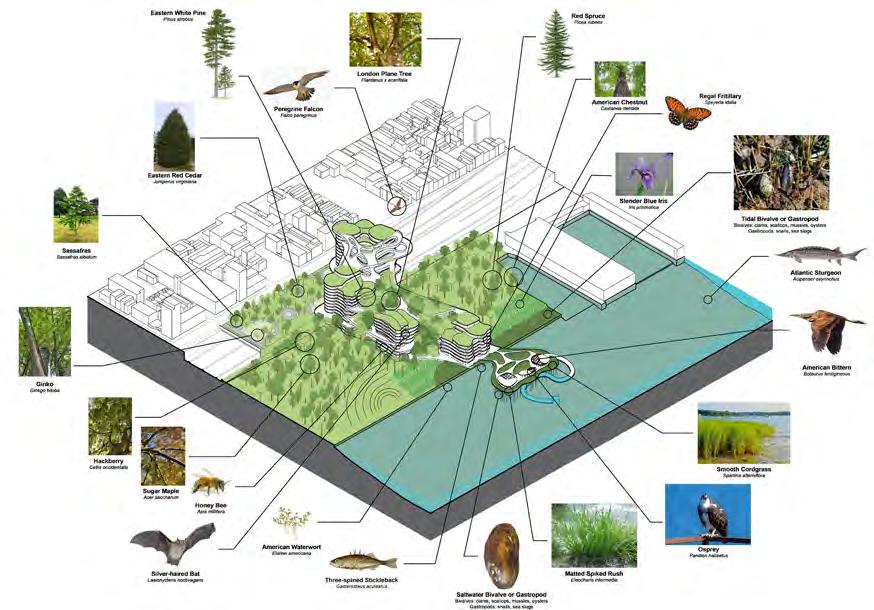

Advanced Architectural Design Studios offer student a number of thematically focused directed studios that range in subject matter based on the interest of the faculty.

Topics vary semester to semester, and include such issues as housing, sustainable design, contemporary technologies, interior architecture and preservation architecture.

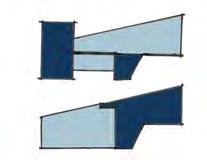

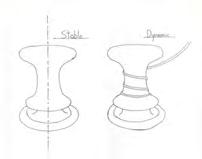

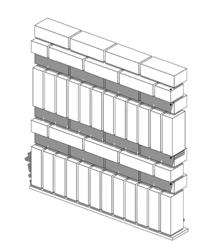

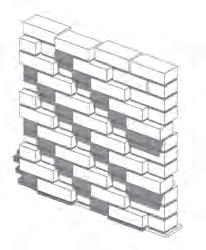

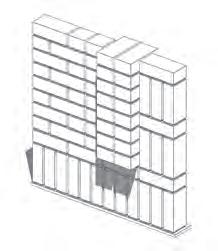

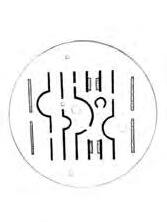

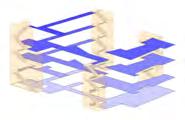

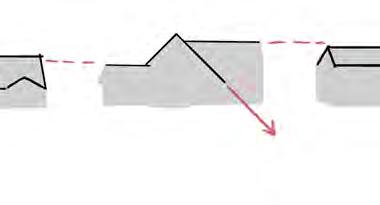

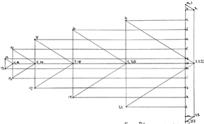

Stability Diagrams - Shear Walls

Working closely with individual faculty members, including the Teaching Firms in Residence, students are asked to address any number of current issues and themes resulting in a wide range of projects. Topics in recent semesters have included contemporary interventions in historic cities, innovation incubator facilities, speculative affordable housing, adaptive reuse, college campus design, tourism and habitat regeneration, ecological design, exploration of the legacies of slavery and the slave trade, and an interfaith community chapel. Topics are selected by faculty and vary from semester to semester.

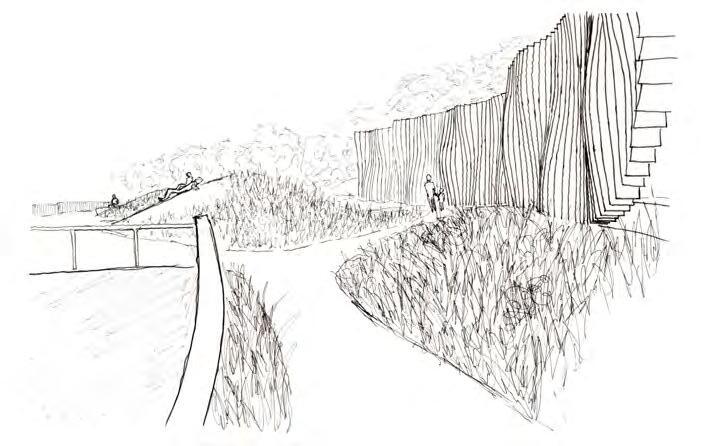

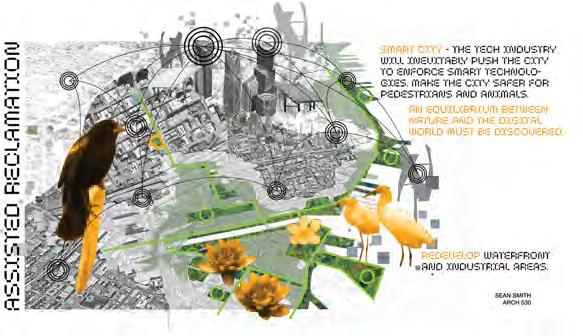

At first glance, it would seem that mapping is a straightforward task, and it certainly can be perceived in that fashion if one is to focus only on that which is easily seen. It is relatively easy, for example, to map a change in geography, the physical relationship between buildings, or a water’s edge as it relates to a land mass; however, things are often connected in meaningful ways even when they do not share a proximity or physical relationship, and the way of mapping this narrative is the challenge. In the work throughout the semester, a better understanding of how to research, discover, and elaborate on these non-tangible connections was discovered. The design perspective has changed in the way highlighted above; one must learn how to reconsider the act of mapping. With regard to representation, one must learn how to devise a number of mediums in a non-traditional way to develop relatable and communicative drawings. For example, instead of using a strictly two-dimensional image to create a map, some of the example’s blend in images of perspective/axonometric as a means

to evoke different emotions. In the A4.3 map, this quality and the use of 3D perspectives heighten the effect of the digital web.

The livelihood of San Francisco is much more complicated than one might expect. My research demonstrated that there is a striking dynamic in the attitude of the place. The city is progressively technological, built on a foundation of the digital world and associated companies, yet for as advanced as it proposes to be in the near future (as a “smart city”), there is an immense issue of homelessness and poverty. On top of this, the city represents a human endeavor to artificially manipulate land and to expend resources for means which do not address issues of climate change. Culturally, the city of San Francisco is very vibrant and strong. There is equally a beautiful array of native species; however, in order to protect these natural landscapes the city must take steps to bridge both worlds in a nondestructive way.

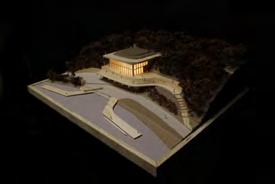

Effects of the Modernizing World: Finding a Modern Japanese Architectural Style

Course: ARCH 576 Theoretical Origins of Modern Architecture

Work by: Sean Smith

Professor: Gail Fenske

Louis Kahn’s Expression of Community Through Architecture: The Trenton Bath House

Course: ARCH 576 Theoretical Origins of Modernism

Work by: Delena Erickson

Professor: Gail Fenske

The Ames Building: A Reflection

Course: ARCH 577 Skyscrapers

Work by: Meghan Rodenhiser

Professor: Gail Fenske

ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

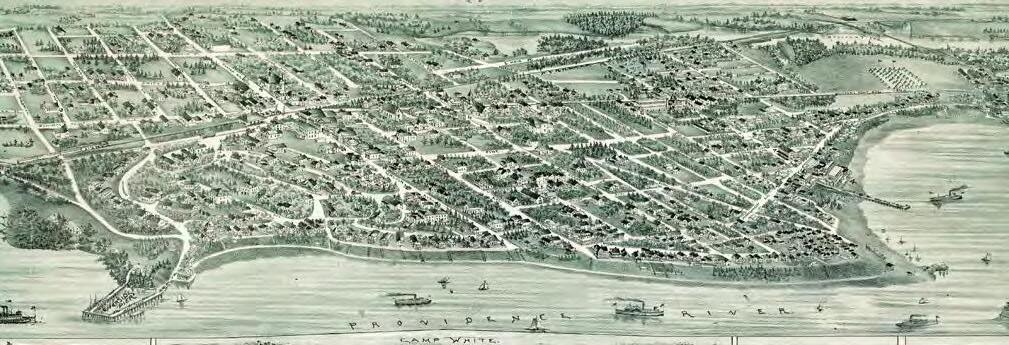

This fall, students in PRES 341/541 Building Documentation and Research Methods conducted a limited-scope cultural resource survey of commercial, civic, and institutional buildings in and around Riverside Square in East Providence, RI. The purpose of the survey was to identify and evaluate properties in Riverside Square that may be eligible for the State and National Registers of Historic Places. The survey also considered the potential for a historic district in the square. The survey was conducted in collaboration with Dr. Ginette Wessel’s Interdisciplinary Planning Workshop course, which undertook a broader Riverside Downtown Revitalization Planning Project.

The survey included completion of twenty-nine Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission Property Data Forms for properties in and around Riverside Square. Tasks included photography; collecting basic building information; archival research utilizing historic maps and photographs, census records, city directories, and title research; and secondary sources. The survey also collected information on potentially historic properties from community members at the open house event organized by PLAN 511 students at the Riverside Congregational Church.

There are several historic contexts that significantly shaped the development and built environment of the Riverside neighborhood and Riverside Square. The earliest of these contexts is the development of Riverside as a recreation and resort district from 1860 to 1930. Around the turn of the twentieth century, Riverside transitioned into a residential and commuter suburb, which had a profound effect on the physical development of the community.

The third significant context is the overall development of Riverside’s civic and religious institutions and commercial architecture from 1880 to 1970. Riverside’s growth throughout the historic period is also closely connected to the development and eventual abandonment of the Providence, Warren and Bristol Railroad from circa 1850 to 1970.

In addition to completing historic resource data forms, students evaluated properties and the potential for a historic district according to the criteria for eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places. Based on their research and evaluation, students identified eight properties that appear individually eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. They also identified a historic district comprised of sixteen contributing buildings dating from ca. 1860 to 1970.

In

In

In

The

Landmarks of Memory

Preservation keeps the landmarks of our memory visible. Sometimes these are buildings, but often they are landscapes that bring us back to a place in our past, or evoke a historical memory that is tied to place in more intangible ways.

Lessons Learned (Maybe)

The National Trust for Historic Preservation’s “Preservation for People: A Vision for the Future” (2017) recognizes the need for preservation efforts to “create and nurture a more equitable, healthy, vibrant, and sustainable community”. Rural landscapes are an important part of this type of community in many parts of the U.S. Urban renewal destroyed many vibrant communities in the 60’s and 70’s. Preservation laws and initiatives have been put in place in response to these losses. Have we learned from our mistakes?

Threats to Rural Landscapes

An often subtle and insidious type of destruction has been gathering momentum as “growth and progress” radiates out from urban centers. Suburban sprawl threatens to permanently alter the landscape, creating a homogeneous country of strip malls, housing developments, McMansions, and big box stores.

Intangible Heritage

To go beyond the built environment, to make preservation for the people, we need to broaden the scope of what we choose to pro-tect to include heritage not traditionally within the realm of “Historic Preservation”. These include festivals, foodways, legacy businesses, and elements of rural life that have been not been considered an important asset to the community.

Do we need more economic growth here, or should we place equal importance on preserving the land which was likely an import-ant seasonal camp for native people?

Preservation Versus the “Growth Machine”

It’s time for to protect our rural heritage before it’s too late. What can be done?

• Tax incentives for keeping farmland open

• Agricultural preservation restrictions

• Changes in zoning laws

• Collaboration with those seeking to preserve natural resources

• Community garden/farming projects

• More surveys to establish the presence of archaeological resources

• Public education and outreach to involve groups not usually associated with preservation initiatives.

The United Nations has set forth a list of sustainable development goals. These goals are to help ensure a better future for the world. They include climate action, health and wellbeing, gender inequality and division, education, poverty, and more. These goals are all encouraged to be achieved in order to create a better world and relationship among countries. Sustainable development is one of the most important issues the UN is trying to improve. The UN defines sustainable development as a "blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all." Gender inequality is a topic that is holding many countries back in ensuring a sustainable developmental design. The Gender Inequality Index (GII) is measured by health, empowerment, education, political representation and economic status. When there is a higher GII value, the more disparities between females and males and the more loss to human development in a country.

The goal of this study is to determine if there is a relationship between countries in the world that have a relatively higher gender inequality index and whether they are educating and achieving a sustainable development plan.

The map creates the conclusion that the lower the GII, the more likely a country is to have a sustainable development plan. The sustainable development plan that the United Nations recognizes can be different to all countries and their standards, however the GII is a fixed number based on a unified scale. The numbers cannot be exactly compared but the idea of their steps towards achieving sustainable action can.

The regions with the lowest inequality rate have countries with sustainable development plans. European countries have the lowest GII compared to other parts of the world. Almost all the European countries recorded have a Sustainable plan in place, with Stockholm, Sweden being named the “greenest city in the world.” Australia, Canada, The United States, and China are among the countries with a relatively low GII and an action plan in place

ThedatachartaboveshowsthetotalnumberofcountriesthatfallintoeachGender InequalityIndex(GII)category.ThelowertheGII,themoreequalityacountryhasfor thefemalepopulation.Thesecountriesaremorelikelytohavesustainabledevelopment plansinplacefortheirnation.Thiscorrelationcaninferthatcountrieswhoprioritizeequal opportunityandrightsforwomenalsoprioritizecreatingandfollowingaplantoensurea sustainabilityplan.ThechartbelowshowsthepercentageofthisdataperGIIcategory. ThepercentageofsustainabledevelopmentfallsastheGIIrises.

Many Central American countries, along with Southeast Asian countries, have a sustainable development plan in place but do not have a low GII. The map can infer that these countries take a priority in the sustainable consumption and production issues facing the world today.

On average, the Southern hemisphere had the highest GII with the lowest amount of sustainable development plans. Yemen is one of the countries with the highest GII, 0.83. However, Yemen is a country that has a national plan in place. The results are not all direct correlations however based on the results found and analyzed, there is a correlation between Gender Inequality in a country or region and the Sustainable Development initiative that country is taking.

The education percentage of females in a country is a factor used to measure GII. Education is one of the many variables used, so extracting that specific data has allowed there to be analysis between education and whether a country has sustainable development. Education is an important part of sustainable development because education is how the future generations will continue to view the world and live within it. The education of sustainable plans and future development will ensure the sustainable goals are continuing to be reached and improved for the continuous future. The countries with the lowest female population that are educated are located in Africa and South America. These regions do not have as many sustainable development plans or a relatively high GII in comparison to the European countries and the North and Central American regions.

In conclusion, this map shows a direct correlation between a sustainable development plan in a country with the education of females and the gender inequality of that country. The more educated and socially equal a country is, the more likely it is to have a network of sustainable action to ensure the future development of sustainable action plans.

Work by: Wilhelmina Giese

ABSTRACT

Differentiating itself from town and city examples, the farm driveway is a long ribbon of gravel extending from a rural road to a farmstead. Not a place for leisure activities such as sidewalk chalk, summer car washes, and rummage sales offered by its urban cousins, the farm driveway is an essential utilitarian element of the rural workplace. Investigation into the evolution of the farm driveway over the past few decades produces a bittersweet picture of the future of agriculture in the United States - one with positive elements such as the broadening of identities, increased recognition of farms as businesses, and less seclusion, but also one with negative elements and the specter of impending abandonment. Using case studies from South Dakota, this paper examines the regional spread of changes in farm driveways and their meanings across the Midwest as the farm industry continues to evolve and consolidate and its cultural landscape shifts.

ABSTRACT

First established in 1864, the rubber factory on the east side of Wood Street in Bristol, Rhode Island was a center of industry for the town over the next century. Filling an economic void left by the diminishing merchant sea trade around the same time, the factory employed significant portions of the populace until its closure in 1977. During its period of operation, the factory complex grew to an impressive size, eventually comprising forty-six buildings. Considering its size and economic importance, it is only natural that the factory had outsized impacts on the economic and physical development of Bristol from the mid-nineteenth century into the twentieth. Furthermore, the layout of the factory itself sits in a unique context within the development of industrial landscapes. Overall, the rubber factory complex as a cultural landscape reveals a great deal about the history and development of Bristol and the town’s place in the greater context of industry and trade in the United States.

ABSTRACT

Populated by neighborhoods, gas stations and strip malls, Metacom Avenue is now the main thoroughfare through the Town of Bristol, a status cemented by the construction of the Mount Hope bridge in 1929. However, it was once a pastoral setting dominated by farmland, and valued for its separation from the industry and crowds of downtown Bristol. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the avenue was home to “outlying institutions” including several asylums, hospitals, a poor farm, and the lone survivor from this era, the RI Soldiers’ Home. In the 1950s, shifting economic and social needs meant that suburban development and industry began to infringe on the “outlying institutions” and pastoral setting of the avenue. This paper examines the landscape change on Metacom Avenue between 1880-2022, and how its longest surviving institution, the Soldiers’ Home, changed along with it. These shifts in Bristol’s culture demonstrate of how the town’s social and civic priorities changed over time and the impacts of those priorities on the landscape.

ABSTRACT

Studying a cultural landscape reveals the interaction between a social group and the space to which they belong. While being an indicator of the values and beliefs of a social group, a cultural landscape has a significant impact on the formation of a group member’s identity.

At Green Mountain Valley School (GMVS), the cultural landscape is defined by a dominant project. Since its founding in 1973, the institution has established itself as a college preparatory high school that produces world-class ski racing athletes. Almost all aspects of life at the academy revolve around ski racing and show how it takes precedence over other activities. The athletic-centered direction of the school is apparent in its strategic location, the spatial organization of the campus, and the social structure of the community. Social stratification and cultural capital play major roles in the different categories that define its members.Through the analysis of the cultural landscape at Green Mountain Valley School, the dominant project can be seen influencing multiple physical and social aspects of the community.

Reading Place I: A Contemporary Landscape Perspective and Reading Place II: The Cultural Landscape of Bristol in Historical

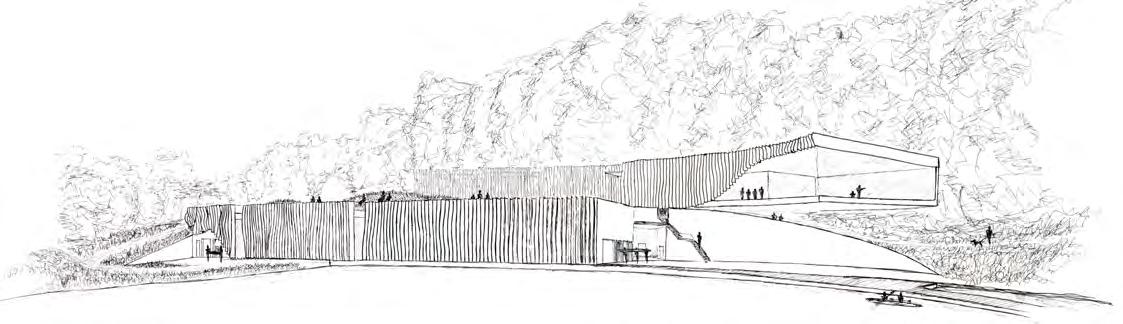

The Graduate Thesis Design Studio offers students an opportunity to speculate propositions of their own interests about what architecture should be.

As the concluding studio in their formal education, students will demonstrate a competency at integrating building systems and materials, social, formal and urbanistic concerns into the design of a building.

*The virtual world is defined by social media, the internet, and virtual/augmented reality.

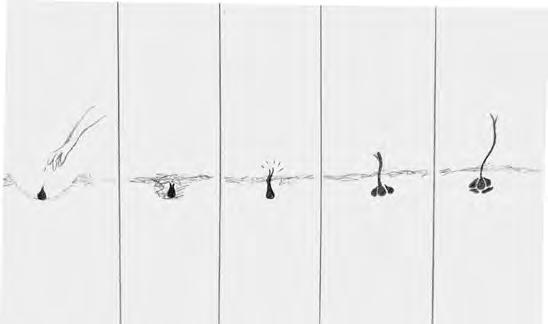

It would be futile to argue that human nature has not been drastically changed by the hand of technological advancement. The common method of interaction, in physical space, has evolved into something that is unfamiliar to human history. With this adoption of the virtual world, essential components of meaningful person to person relationships are debatably lost. This impact of the virtual world* must be recognized with regard to architecture and the built environment. Much is lost in society and the physical world, if relationships are reduced to emotionless text blurbs or low-resolution video calls. This was demonstrated during the quarantine of COVID-19. As soon as people could, they were reuniting with family and friends in physical space.

Many people, in this moment, recognized the deep need for physical interaction. Nevertheless, the virtual world holds with a steady grip, and it must be accepted that it is here to stay. Ultimately, the virtual world has introduced a certain idea of convenience. Social medias allow people to “interact” without leaving their comfort zone, and thus one can avoid the external world if they so please. In this lies the essential issue: people miss the benefits of interaction in physical space because the virtual world has provided them with tools to circumvent the process; therefore, physical collectives dwindle and a sense of community is near lost. It is essential, now more than ever, to reconsider how architectural elements can encourage interaction and rebuild collective/community value.