ARTES E LETRAS NA DIÁSPORA AÇORIANA

ARTS AND LETTERS IN THE AZOREAN DIASPORA

NONA EDIÇÃO

2024

MAIO

FICHA técnica

Director: Diniz Borges

Editorial Board: Linda carvalho-Cooley; Eugénia Fernandes, Emiliana Silva and Micahel DeMattos

Advisory Board: Onésimo Almeida, Duarte Silva, Teresa Martins Marques, Renato Alvim, Debbie Ávla, Manuel Costa Fontes, Vamberto Freitas, Irene M. F. Balyer and Lélia Pereira Nunes

Designer: Humberto Ventura - www.illustratetheweb.com

Contents 3 em poucas palavras / in a few words 5 aida batista, bicicletas de toronto 7 the bellicose nature of natalia correia 10 navigating new horizons 1 3 vozes do arquipelago: um olhar historico sobre a poesia açoriana 18 comemorando Camões 21 2

EM poucas palavras...

Diniz Borges

director

in a few words...

Não foi há muito tempo que refleti oespirito açoriano em terras norteamericanas nestes termos:

A nossa Diáspora está repleta de homens e mulheres com responsabilidade e muita dedicação. Temos, felizmente muitos seres humanos que fazem com que as nossas associações tenham vida e promovam as nossas tradições populares. Também sabemos que muitos desses homens e mulheres estão extremamente cansados.

É que por vezes os aborrecimentos ultrapassam todas diligências. Mas mais do que nunca, neste novo período das nossas vivências em terras americanas, há que ter homens e mulheres com vontade e aptidão para navegar este navio aos mares de um amanhã, que embora seja diferente, continuará a celebrar o espírito açoriano, lusitano e porque não lusófono em terras americanas. Na nossa Diáspora existe um manancial de talentos, de gente que ainda sabe lutar contra a maré, não tivéssemos vindo de ilhas abandonadas pelo Terreiro do Paço, colocadas à mercê da sua força telúrica e da criatividade do seu povo. Daí que acredito, veementemente, que com o diálogo, a abertura à crítica, uma nova visão baseada na realidade do mundo de hoje, assim como o trabalho despretensioso e verdadeiramente comunitário, possamos continuar a construir a Diáspora que todos queremos e que Portugal e os Açores necessitam, encarando os desafios de uma nova era, onde o pós-pandemia se conjuga com uma

comunidade em mudança. A mudança que, mesmo sem pandemia, sabíamos, muito bem, era inevitável e dava passos gingantes nas nossas vivências açoramericanas.

Porque acreditamos nestas novas auroras que despontem pela nossa diáspora em terras americanas e canadianas, Filamentos (artes e letras na diáspora açoriana) aqui está, com uma série de textos, nas nossas duas línguas, como forma de diálogo cultural e de nos aproximarmos, independentemente da latitude.

Not long ago, I reflectedonourAzorean Spiritintheseterms:

Our Diaspora is full of men and women withresponsibilityandalotofdedication. Fortunately, we have many human beings who make our associations come alive and promote our popular traditions. We also know that many of these men and women are extremely tired. Sometimes, challenges overtake all diligence. But more than ever, in this new period of our lives in American lands, we need men and women with the will and aptitude to sail this ship to the seas of tomorrow, which (although it will be different) will continue to celebrate the Azorean, Lusitanian and why not Lusophone spirit in American lands. In our Diaspora, there is a wealth of talent, of people who still know how to fight against the tide, had we not come from islands abandoned by Terreiro do Paço (central powers), placed at the mercy of their earthly strength and the creativity of their people. Thats why I firmly believe that with dialogue, openness to criticism, a new vision based on the reality of todays world, as well as unpretentious and truly community-based work, we can continue to build the Diaspora

3

thatweallwantandthatPortugalandthe Azoresneed,facingthechallengesofanew era, where the post-pandemic combines with a changing community. The change that,evenwithoutthepandemic,weknew very well was inevitable and was taking giant steps in our Azorean-American experiences.

As we embrace the new dawns in our diaspora in North America, Filamentos (arts and letters in the Azorean diaspora) will continue to stand as a beacon of culturaldialogue.Wealwaystrytopresent a series of texts in our two languages, a testamenttoourunityandcommitmentto bridgingthegapsofdistanceandlatitude. This is our way of bringing us closer together, fostering a sense of belonging and a shared heritage that transcends borders.

DinizBorges

PortugueseBeyondBordersInstitute CaliforniaStateUniversity,Fresno

Foto de diniz borges

Foto de diniz borges

Aida Batista, Bicicletas de Toronto

Onésimo Teotónio

“Quando muito, pode talvez dizer-se que esta última coleção intensifica uma maturidade palpavel da sua sabedoria batida pela experiencia, e manifestam o natural a vontade de quem se sente em pleno controlo das letras e da via”

Durante vários anos Aida Batista lecionou na Universidade de To- ronto, após passagens pela Roménia e pela Finlândia e regresso a An- gola como leitora do hoje chamado Instituto Camões. Apaixonou-se pela grande urbe canadiana e envolveu-se profundamente na vida da comunidade portuguesa, maioritariamente açoriana, ali residente. Foi assídua colaboradora na imprensa local e reuniu em livros muitas das suas crónicas. Tão apreciadas foram e continuam sendo, que os jornais portugueses da cidade faz em questão de mantê-la como colaboradora regular, repto que Aida Batista aceitou, para contentamento dos seus fiéis leitores e dos próprios jornais. As Bicicletas de Toronto, com uma capa sugestiva e uma atraente apresentação gráfica é a mais recente recolha dessas suas crónicas ou, pelo menos, de uma seleção delas. A sua escrita não constitui novidade para os leitores familiarizados com a autora. Quando muito, pode talvez dizer-se que esta última coleção intensifica uma maturidade palpável da sua sabedoria batida pela ex- periência, e manifesta no à vontade de quem se sente em pleno controlo das letras e da vida.

A estada de Aida Batpista em Toronto permitiu-lhe alargar o seu universo, algo que toda a vida foi fazendo, desde os tempos da sua originária Angola. África, Portugal e a Finlândia constituíram etapas importantes no alargar e aprofundar da sua visão do mundo, mas o trânsito da Europa para a América do Norte, já na fase outonal de uma carreira de Ensino, exigiria supostamente a qualquer um redobrado esforço. Todavia, quem como eu vem seguindo de perto os sucessivos livros da Aida, deve ter-se apercebido de que a sua adaptação ao novo continente aconteceu com uma naturalidade espantosa. Toronto e o cosmos multicultural canadiano entraram-lhe nas veias a ponto de hoje, na aposentação e regressada a Portugal, ela continuar ainda a sentir e a respirar a cidade (reconheçamos que, em termos de habituação aos nevões de Toronto, a Aida já levava um grande treino conseguido nos seus anos finlandeses).

Como açoriano, registo com particular agrado o modo como ela criou laços não apenas com a comunidade açoriana de Toronto mas também com os Açores porque, na verdade, o arquipélago está tão pró- ximo da sua Décima Ilha, a das comunidades da sua diáspora norteamericana (EUA e Canadá) que o conjunto forma quase um universo osmótico. Pelo menos é essa a perceção quando se está do outro lado do Atlântico. Em Bicicletas de Toronto, as referências às ilhas e a autores açorianos como Pedro da Silveira, Sidónio Bettencourt, Ivo Machado, Natália Correia, Victor Rui Dores, e açorcanadianos como Marcolino Candeias, Eduardo Bettencourt Pinto e José Carlos Teixeira, surgem lado a lado com alusões a José Saramago, Manuel Alegre, Fernando Pessoa, Vergílio Ferreira, Herberto Helder, Marcel Proust e Ray Brad- bury. Há até páginas especificamente sobre os Açores, uma delas nar- rando a sua corajosa subida ao Pico, incluindo o

5

Piquinho. A crónica termina precisamente com “a apoteose” do cimo da montanha, oonde a autora recorda um locutor que terminava as suas entrevistas com a pergunta: “O que dizemos teus olhos?”.

Aida Baptista responde nestes termos: “Eles dizem que a pr “Eles dizem que a prova foi penosa, mas que, a partir de agora, po- derei proclamar que, apesar da idade, subi a pulso e passo esta estátua erguida de fogo, vergada ao deslumbramento com que me seduziu des- de o primeiro encontro”.

Costumo dizer que os portugueses se crêem mais universalistas do que, de modo geral, são realmente. E não me refiro aos emigrantes, pois no caso deles isso é compreensível. Refiro-me a certos portugueses instruídos, supostamente cultos que, por um motivo ou outro têm de conviver com a diáspora. Por vezes comportam-se provincianamente como ilhéus, mesmo sendo naturais do Continente. Quem se dispuser a ler as páginas de Aida Batista – e As Bicicletas de Toronto são exímio exemplo do que afirmo – reconhecerá de imediato estar em presença do espírito de uma portuguesa de Quinhentos. Tenho consciência de que nessa altura às mulheres não era possível expressarem-se assim (além de poucas terem sido as que viajaram nas naus para a Índia). Por isso a minha linguagem é metafórica. Mas quero vincar bem que nas crónicas desta autora se respira uma notável abertura, não apenas ao mundo canadiano mas igualmente às comunidades portuguesa e açoriana, às suas idiosincrasias e à sua vida, captadas por vezes em penetrantes e percetivos golpes de pormenor incidindo sobre uma figura ou uma si- tuação do quotidiano. No seu todo elas retratam, impressionística mas fielmente, um naco da vida de emigrantes apanhados na rede complexa de um universo no qual não haviam sido

preparados para viver – uma sociedade culturalmente anglo-americana, num clima duro e hostil ca- paz de reduzir tudo a um infinito lençol de branco.

As Bicicletas de Toronto fecha com uma crónica intitulada “Ser cro- nista não foi meu sonho”. Caso para prosseguirmos glosando os versos no sentido contrário do clássico fadista: Mas foi esse o meu fado. Jovem como ela continua, não se admirem se daqui a um ano a Aida Batista nos contemplar com novo livro de crónicas intitulado As Moto- cicletas do Nepal ou A Fórmula 1 de Marte.

6

capa do livro “as bicicletas de toronto”

The Bellicose Nature of Natália Correia

Victor Rui Dores

Translated

by

Katharine F. Baker

more spacious. But almost fifty years on, what I still recall is the bar’s thick haze. Everyone there was smoking: politicians, members of the military, journalists, people in the arts and letters. I recall my waiter Bandola’s friendliness, the tables, chairs, tall bar, red upholstery, engravings on the walls, upright piano along the right-hand wall – and, dotting the open space, the small bust of La Poésie on a high pedestal.

It was courtesy of Carlos Alberto Moniz’s helping hand that I crossed the threshold of the Botequim, conceived and founded by writer Natália Correia (1923-93), for the first time one rainy night in November 1978. Back then, her salon-bar located on Largo da Graça was a nerve center for Lisboan cultural gatherings and political conspiring.

A recent arrival in Lisbon, dazzled by the capital’s magnificence, I was a student in the University of Lisbon’s School of Humanities, leading a life full of new hopes for my future. I took pride in having published my first book of poetry a year before – Poemas de Fogo e Mar [Poems of Fire and the Sea], the upshot of an emotional and romantic crisis that had scarred my adolescence on Terceira. So that night I secretly tucked a copy of the book in my overcoat pocket to offer to “Dona Natália,” this force of nature and veritable living legend.

My first impression of her Botequim was rather disappointing, because frankly I assumed it would be

Natália had turned the Botequim into her personal salon. It was there that she kept appointments with friends and acquaintances. Natália was said to be unsubmissive and insubordinate, egocentric and exuberant, argumentative and contradictory. It was also widely known that, being fond of the sensual and spiritual, she exuded freedom, daring, passion, culture and justice – she who had been the most censored author in Portugal during the dictatorship.

Wearing eye-catching scarves, with her ever-present cigarette holder and almost always a glass of whisky in her hand, Natália reveled in being the center of everyone’s attention, circulating from table to table to crack jokes and hurl criticisms and provocations at her select clientèle. And the writer was indeed selective, keeping her bar’s door shut, thus obliging anyone who wanted to enter to ring the doorbell. And the truth is that only those she wanted to admit got in.

By this point I already appreciated Natália Correia’s poetry. An islander torn from his island, I was discovering my own Azoreanness through Natálian verses:

“Não sou daqui, mamei em peitos oceânicos

Minha mãe era ninfa, meu pai chuva de lava

7

Mestiça de onda e de enxofres vulcânicos

Sou de mim mesma pomba húmida e brava”.

[I’m not from here, I nursed on ocean breasts.

My mother was a nymph, my father a downpour of lava.

A mix of waves and volcanic sulfur, I myself am a wet, angry dove.]

That night our hostess spotted Carlos Alberto Moniz as he entered the Botequim with me in tow. And because another Azorean, Duarte Brás, was already seated at one of the tables, she promptly announced with expressive sweeping gestures, “Well now, this is going to be a night for us to sing the Lira and Samacaio!”

A round of applause from the crowd.

Natália, who was always posing and posturing, approached me, disdainfully inspected me from head to toe, and after blowing a puff of smoke in my face asked Carlos, “So, whom have we here today?”

“An Azorean from Graciosa, a university student,” my friend answered.

I nervously introduced myself, and offered my little book to the great poet shyly.

Natália opened the book, flipped perfunctorily through it, read the dedication, and with a sarcastic smile on her face asked me, “How old are you, lad?”

“Going on 21,” I replied fearfully.

Then Natália at her haughtiest retorted in her dramatic booming voice, “Not much can be hoped for when you’re at the age of poetic masturbation.

And upon saying this, she returned my book and conspicuously turned her back to me as she left.

Standing there with book in hand, I swallowed hard, and according to Carlos I turned redder than a beet.

Perceiving my embarrassment, Natália increased her pace, turned back and, placing her right hand on my left shoulder, said to me with undisguised coquetry, “But continue writing. Continue writing, you’ll get there.”

Then she surreptitiously took the book from my hand, and carried it off with her as she headed for the bar.

“You’re lucky, she kept your book,” Carlos whispered in my ear.

I spent the rest of the night feeling sorry and sad for myself. Only after downing two whiskies did I muster enough courage to sing the Lira and Samacaio, chiming in with Natália, Carlos and Duarte.

8

figura de natalia correia , lisboa

Originally published as “Da natureza belicosa de Natália Correia”: https://portuguesetimes. com/admin/archive/ Edi%C3%A7%C3%A3o%202737%20 -%2006%20de%20dezembro%20 de%202023.pdf (p. 24)

Editor’s note: Katharine F. Baker and Emanuel Melo have translated Natália Correia’s travelog of her first trip to the United States at in 1950 age 26, Descobri Que Era Europeia, being published by Tagus Press as In America, I Discovered I Was European.

9

capa do livro de natalia correia “in america i discovered was european

Navigating New Horizons: The Fearless Creativity of Azorean Young Writers

Vamberto Freitas

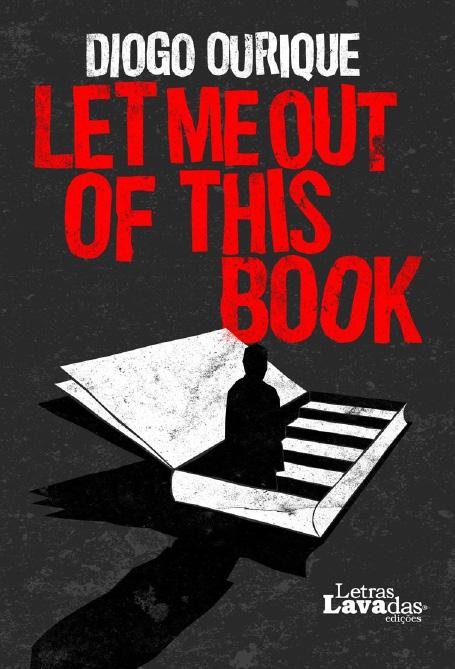

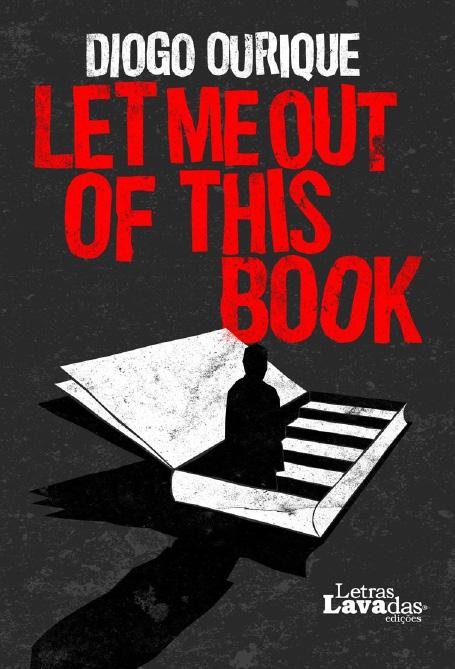

Diogo Ourique is another exceptional writer for me, apart from all his creativity while in Lisbon and now from the Azores. His first novel, Tirem- me Deste Livro (now translated into English, Let Me out of the Book), is one of Portuguese literature’s most original acts of fiction. Born in the parish of Agualva on Terceira Island, he makes no apologies for returning to his homeland. I can’t tell you enough about my admiration for him and his entire generation. A supreme writer who has multiple geographies as a point of reference, he develops his career as if the sea between us all were only, and it is, a road to the rest of the world. Let Me Out of This Book is about to be released in the United States in English translation, now titled Let Me Out of This Book, by Letras Lavadas and Bruma Publications of the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute at

California State University, Fresno, and directed by Diniz Borges.

VF- Your first novel, Let Me Out of This Book, published in 2019, was more than a surprise that perversely delighted me. After all, it had to be an Agualvense author who cracked a character's head open in the very first pages. What follows makes these pages more than subversive among all Azorean authors.

DO - The idea was to try and go in with a bang, strictly following that literary rule of trying to capture the reader’s attention from the first pages. With this prologue, I also wanted to set the tone of the work right from the start so that no one would be fooled: this is a heavy book (in terms of what it describes) with blood, victims, and evil deeds. But at the same time, by telling the story of a protagonist who realizes his status as a fictional character, the book itself ends up questioning the reality of everything that happens throughout the plot since it’s all just stories and actions imagined and written by someone else –so did they happen? Perhaps, I’m thinking now; it’s a strategy I’ve invented so that I can press the terror and the macabre at will while at the same time holding the reader’s hand and saying: “Calm down, none of this is real. This isn’t happening. So, anything goes”. This strategy ended up being very useful to me, as it allowed me, in this first literary breath, to experiment freely, to say whatever I wanted, and not to limit myself exclusively to the four walls of a story.

Because that was my motivation from the start and has been throughout everything I’ve written and what I’m yet to write: to go beyond those walls, to “break the fourth wall.” It is packed with many other stories –in literature,cinema, and video games

10

–that describe people who wake up from their reality and realize that the world around them isn’t real, who break that fourth wall and speak to the public. Many of us have imagined ourselves in different skins and different lives; we’ve questioned our existence. We try to deconstruct the reality around us, analyzing it in parts, questioning dogmas, and refuting certainties. That’s what I find most interesting about art: deconstruction. Studying and getting to know the rules well so that, from there, we can dismantle them, put them in a corner, and even make fun of them.

Another famous literary rule is that you should write what you would like to read. Well, I always like to read chaos—but structured chaos that knows the rules— chaos that knows how to be chaos.

VF- Your career in Lisbon has been glittering as a comedian and in manyother activities linked to the arts and communication. How did you get here?

DO- I’ve always had a passion for humor, but I’d hardly consider myself a humorist or comedian – maybe one day, with a good dose of self- confidence and a few tranquilizers in my stomach before I go on stage. I try to incorporate humor into a lot of what I do because, in my opinion,laughter is the easiest way to get a message across or explain our points of view. Perhaps it’s again because of this need I’ve always felt for constant deconstruction – or maybe this need has been fueled by humor.

and watch comedy shows and comedy films. For some reason, content such as current political satire shows – mainly in Anglo-Saxon culture, which ends up influencing the whole world – which holds up a mirror, through humor, to what is happening around us, is so popular and audience leaders.

Humor has a significant role in deconstructing and influencing opinions, even though those who practice it professionally often try to avoid thisresponsibility, claiming that they are just jokes. But the truth is, and we know it: humor is good for us and annoys dictators. For that reason alone, I think it’s valuable.’

VF-You belong to a generation of writers I admire, and I think I've made that clear in the pages of Açoriano Oriental. When going to study on the mainland and staying there was a kind of glory before the others who stayed, what made you return to the Azores and pursue your career from here?

DO - Not only have we noted your interest as a literary critic in the most recent generations of Azorean writers, but we can only thank him for this spotlight that he constantly points out to us, guiding our path. It’s great to feel seen, appreciated, and recognized by people who are attentive to our culture and have already contributed much to it.

Because humor is all of these things: it’s deconstruction, it’s questioning, it’s digging to find the unexpected, the absurd. That’s why we like to listen to jokes, read chronicles and funny stories,

Studying on the mainland, going abroad, and getting to know the overseas world is familiar to many islanders, regardless of their chosen professional field. There is a desire for discovery, to get to know the metropolises, and to be a great cosmopolitan. But cosmopolitanism can do nothing about the “Longing for Home.” Metropolises gradually lose fun, charm,

11

and novelty – that siren song. They become the hamster wheel where we are trapped on commutes and routine days. We begin to appreciate the paradoxical freedom that the islands guarantee us since they are surrounded by sea – but they are also full of everything that is ours. They are full of what inspires us, the fresh air that nourishes us, the calm that – in our case – allows us to write, to think, to have ideas, to take it easy, not having a subway to catch or a highway to cross at rush hour to take a quick dip in distant, crowded beaches and return to a rented apartment in a complex that will never be ours.

That’s another increasingly pressing issue. I believe many of us still want to stay in the metropolis and the ecstasy of the city. But being cosmopolitan is no longer in the Portuguese pocket. Often, returning is the most economical and, lulled by the magnetism of the motherland, definitive solution.

I find myself somewhat in the middle of these two scenarios. Encouraged by a global pandemic, I returned to my homeland, and here I’ve been, watering the roots that never dried up. I stopped thinking about metropolises because I no longer felt like paying what they charged me financially or regarding quality of life. I stopped seeing the island as a port of departure to discover new worlds, and now I see it as a haven with so much still to accomplish. Here, I can see the consequences of my actions, understand the influence of what I do, and the effects of my work. The hamster wheel is not just a wheel; it has curves and countercurves, places to rest and picnic, service stations, and halts. If the opportunities aren’t there, we try to create them. And if we still can’t, then sure, let’s go abroad, be cosmopolitan, without fear – but without

ever forgetting the place, we’ll probably always return to our islands, where we can live rather than exist.

Vamberto Freitas is the Azore’s most respected literary critic, with a body of literary criticism that is truly impressive. The Azores owes much to Vamberto Freitas.

This interview was first published in Portuguese in Açoriano Oriental on the literary page BorderCrossings.

Translated to English by Diniz Borges

12

em baixo: capa do livro “let me out of this book” ao lado: foto do autor diogo ourique

Vozes do Arquipélago: Um Olhar Histórico sobre a Poesia Açoriana

de Almeida

(aula dada pela poeta Ângela de Almeida nos cursos de língua e cultura portuguesas na Universidade do Estado da Califórnia em Fresno, em março de 2024)

A poesia açoriana pode ser analisada a três níveis que são o espaço natural onde vivemos, feito de «terra-líquida» e «marsólido», essa dualidade que nos enforma em cada instante, a par de toda a natureza e que constitui uma energia psíquica ou um universo subtextual que povoa toda e qualquer escrita insular. Num segundo nível, as condicionantes da insularidade, ou seja, até que ponto a ilha e o mar ampliam ou reduzem o nosso sentimento de liberdade, até que ponto condicionam também a nossa sociabilidade, uma vez que o isolamento tem sido, ao longo dos séculos, um tema recorrente em alguns autores- veja-se, a título de exemplo, Roberto de Mesquita.? Num terceiro nível, a interação entre o mundo e o espaço ilhéu, através das viagens, dos

livros que foram chegando, mesmo quando ainda não havia imprensa nos Açores, dos meios de comunicação sociala imprensa chegou às ilhas no século XIX-, da vinda de outros povos para as ilhas, enriquecendo sobremaneira o nosso mundo interior e poético. Por exemplo, apesar de ser insular e viver numa ilha, escrevo imenso sobre o estado do mundo, surgindo o mundo natural e, sobretudo o mar, como lugar de regeneração vital.

Os três níveis, acima mencionados, são importantes para percebermos a evolução da poesia nos Açores, ao longo dos séculos. Nos séculos XVI e XVII, é escasso o registo de poesia nas ilhas, oque é compreensível, uma vez que o povoamento teve início a meio do século XV.Deste modo, quem encontramos , no século XVI, é Gaspar Frutuoso , que se destacou não como poeta, mas sim como historiador indispensável dos Açores, conhecido pelos volumes de Saudades da Terra

Quanto ao século XVII, existem duas referências: Catarina de Cristo e D. Fradique da Câmara e Toledo. Quanto à primeira, não obstante as inúmeras referências em algumas enciclopédias e monografias, a verdade é que não foi possível encontrar algum poema sequer. Chamava-se Catarina Bettencourt e foi freira no Convento de S. Gonçalo em Angra do Heroísmo, tendo passado a usar onome de Catarina de Cristo. Quanto a D.Fradique da Câmara e Toledo, a sua poesia é de menor qualidade, todavia distinguiu-se, entre outros, pela tradução de tradução dos seis primeiros livros da Eneida, de Virgílio. Antes de avançarmos, convém referir que ,até à chegada da imprensa nos Açores em 1830, muitas obras literárias ficaram perdidas. Por outro lado, no que diz respeito às mulheres, muitas vezes enviadas pela família para os conventos, estavam, como

13

Angela

sabemos, entregues ao ostracismo. Deste modo, quase sempre , os poemas, de autoria feminina, eram destruídos. Outras vezes, conforme sabemos, e falando já das publicações na imprensa , a partir de 1830. assinavam com nomes masculinos. Neste século, e também no início do século XX, para se protegerem, algumas poetisas publicavam em almanaques , fora dos Açores. Outras, mais afoitas, viam a sua poesia acolhida em almanaques açorianos que abriam as portas à poesia de autoria feminina.

No século XVIII, e apesar de ainda não haver imprensa-o que levou à perda irreparável de imensos poemas, conforme se lê nos relatos da época -, graças ao empreendimento pessoal dos poetas, também auxiliado pelos valiosos livros que chegavam nos navios e por outros tantos que se liam nos conventos e que lhes chegavam através dos frades que davam aulas particulares – a escola pública só chegou aos Açores por volta de 1850 -, houve poetas que se notabilizaram pela qualidade surpreendente da sua poesia – a que não se perdeu, graças á dedicação dos jornais e dos críticos no século seguinte. Importa afirmar, a propósito destes e também de toda a poesia do século XIX e até do início do século XX, prevaleciam o soneto e as odes, notando-se uma leitura bastante consistente dos clássicos, de Camões e, já no século XIX e depois deste, de Antero de Quental. Devo ainda acrescentar que os sonetos são maioritariamente uma revelação e distinguem-se muito das outras formas (de menor qualidade). Apenas na ilha do Faial, D. Frei Alexandre da Sagrada Família, Francisco Vieira Goulart, João Pereira de la Cerda, Manuel Inácio de Sousa e Vitaliano Brum da Silveira são poetas de primeira linha na História da Poesia Açoriana. Juntamse a eles Francisca Cordélia de Sousa,

embora não possuamos qualquer registo de um único poema, todavia as referências ao seu talento literário são muitas e unânimes. Era filha do conceituado poeta Manuel Inácio de Sousa, de quem deixamos aqui um belíssimo soneto, inserido na edição crítica que oinvestigador Francisco Topa dedicou ao poeta:

Vem ver-me, amado bem, neste retiro, Onde rios de lágrimas derramo; Ouvirás o som triste com que clamo, Quando o teu doce nome aqui profiro.

Vem ver-me como aflito aqui suspiro

Nos transportes d´amor em que m´inflamo;

C´o som da roca voz com que te chamo, Verás soltar-se o pranto em largo giro.

Vem ver-me; e quando vires a mudança

De meu rosto, já triste e macilento, Talvez que abrandes mais a tua esquivança;

Mas se tiveres dó do meu lamento, Com um suspiro teu e uma lembrança, Então farás ditoso o meu tormento.

Ainda no século XVIII, três outros poetas de excelência: ManuelAntónio de Vasconcelos, que publicou belíssimas odes e foi fundador do Jornal Açoriano Oriental, José Jácome Raposo e Bento Luís Viana, ambos naturais de Ribeira Grande, João Cabral de Melo Neto e João Miguel Coelho Borges, ambos da ilha Terceira. Quanto a Bento Luís Viana, os

14

seus ideais liberais leram-no ao exílio em Paris, onde cursou Medicina e publicou alguma poesia. No que diz respeito a João Cabral de Melo Neto, estudou na Universidade de Coimbra. Apesar de quase toda a sua obra poética se ter extraviado, é possível ler sonetos de sua autoria nos Anais da Ilha Terceira e em algumas publicações periódicas.

O século XIX chegaria para a poesia açoriana com o prenúncio da imprensa e da escola pública: ambas viriam a desempenhar um papel central na vida literária, que também será enriquecida com a abertura das primeiras bibliotecas públicas em Angra, Ponta Delgada e Horta. Deste modo, o século XIX , também avivado pelo Liberalismo, abrir-se -á às tertúlias literárias, ao teatro, a uma vida cultural e a um contributo inestimável dos jornais e das revistas que então foram fundados e aos quais devemos uma divulgação ímpar da poesia nos Açores. Não é pois por acaso que o número de poetas aumenta substancialmente. Não apenas Antero de Quental (S. Miguel), Roberto de Mesquita (ilha das Flores), Carlos de Mesquita (ilha das Flores), Espínola de Mendonça, Teófilo Braga, Armando Cortes-Rodrigues, Raposo de Oliveira, Duarte de Viveiros, Rebelo de Bettencourt (S. Miguel), Fernando de Sousa, Osório Goulart, Miguel Street Arriaga, Manuel de Arriaga, Manuel Joaquim Dias(Horta), João de Matos Bettencourt (S. Jorge), Manuel António Lino, José Augusto Cabral de Melo, Ângelo Ribeiro (Terceira), Manuel Bernardo Maciel (Pico), Garcia Monteiro, Ernesto Rebelo (Faial), entre outros, mas também as mulheres que escrevem poesia, aquelas que têm a coragem de assinar o seu nome: Maria Adelina da Costa Nunes , Maria Alice Goulart, Maria Cristina Arriaga, Ema Noía de Medeiros.

Hermenegilda Lacerda(Horta), Filomena

Serpa, Mariana Belmira de Andrade, Maria Xavier Pinheiro (S. Jorge), Alice Moderno, Isabel Câmara Quental, Maria das Mercês do Canto Cardoso (S. Miguel), Amélia Ernestina d´Avelar (Pico), Helena Graça Rodrigues (Graciosa),Maria Palmira dos Santos Jorge (Corvo), Maria Guilhermina de Bettencourt Mesquita(Terceira), honraram a poesia e a Literatura . Deixo aqui, em jeito de homenagem a todas e a cada uma, um belíssimo soneto de Alice Goulart , que nasceu na cidade da Horta, em 1864, e publicou dois livros de poesia, tendo também publicado em alguns jornais e almanaques:

Quadros

É plena madrugada. A meiga Aurora

De rubra e nívea côr o céu colora: Doirada e branda nuvem passa e chora Límpidas gotas, que a florinha adora.

Desdobra as alvas folhas da campina

O débil lírio, que gentil se inclina:

E lá no império brilha a matutina, Argêntea estrela, celestial, divina.

Na selva trinam os febris cantores:

O oriente tem mais vivas côres: E espira a rosa virginais odores.

Enquanto d´entre as côres do arrebo, Carmim e oiro e prata, qual farol, Surge o radiante o luminoso sol! (in Reflexos d´alma,p. 45)

E o século XX traz-nos poetas de referência, que graças ao aumento das editoras e à dinâmica da imprensa, até

15

metade do século, além dos círculos literários que se formam e do destaque que a poesia merece quer em jornais quer em revistas, chegam até nós com a sua obra poética completa , pelo menos quase todos. Adelaide Sodré, Vitorino Nemésio, Emanuel Félix, Marcolino Candeias, Mário Cabral, Maduro Dias, Álamo Oliveira, Santos Barros, Ivone Xinita, Borges Martins, Rui Duarte Rodrigues(Terceira), Alfred Lewis, Pedro da Silveira (Flores), Eduíno de Jesus, Virgílio de Oliveira, Jacinto Soares de Albergaria, Natália Correia , Madalena Férin, Luís Francisco Bicudo, Adelaide Freitas, Carlos Wallenstein, Daniel de Sá(S. Miguel), Luiza de Mesquita, Oltília Fraião , Mário Machado Fraião, (Horta), Almeida Firmino, José Martins Garcia (Pico) , Norberto Ávila, Carlos Faria(S. Jorge), Frank Gaspar, José Luís da Silva (Califórnia)são alguns dos nomes que deixaram um legado muito importante de poesia. E há os poetas de ligação entre os dois séculos-XX e XXI, como sejam , entre outros, Eduíno de Jesus, Emanuel Jorge Botelho, Renata Botelho (S. Miguel), Eduardo Bettencourt Pinto (residente em Vancouver), Frank Gaspar, José Luís da Silva (residentes na Califórnia), Leocádia Regalo (residente em Coimbra), Henrique Levy, Urbano Bettencourt, Ângela de Almeida, (residentes em Ponta Delgada), Álamo Oliveira, Carlos Bessa, Luisa Ribeiro (Terceira), Daniel Gonçalves (residente em Santa Maria), Vasco Pereira da Costa (residente em Coimbra).

Não podemos também esquecer o papel fundamental que os suplementos literários desempenharam e têm desempenhado nos jornais, a partir da década de sessenta, nomeadamente , como tem acontecido também com a página literária «Maré Cheia», do jornal Tribuna Portuguesa, coordenado pelo Professor Doutor Diniz Borges, e recentemente, a revista

Filamentos, também com a sua coordenação. A revista Filamentos, os webinars, as entrevistas e as conferências desempenham um papel fundamental na agregação de uma Poesia Insular Açoriana que o mar não separa nem dissolve, antes, amplia e torna perene.

A concluir, um poema do grande e inesquecível poeta Emanuel Félix:

FIVE OCLOCK TEAR

Coisa tão triste aqui esta mulher com seus dedos pousados no deserto dos joelhos com seus olhos voando devagar sobre a mesa para pousar no talher

Coisa mais triste o seu vaivém macio pra não amachucar uma invisível flora que cresce na penumbra dos velhos corredores desta casa onde mora

Que triste o seu entrar de novo nesta sala que triste a sua chávena e o gesto de pegá-la

E que triste e que triste a cadeira amarela de onde se ergue um sossego um sossego infinito que é apenas de vê-la e por isso esquisito

E que tristes de súbito os seus pés nos sapatos seus seios seus cabelos o seu corpo inclinado o álbum a mesinha as manchas dos retratos

E que infinitamente triste triste o selo do silêncio do silêncio colado ao papel das paredes da sala digo cela em que comigo a vedes

16

Mas que infinitamente ainda mais triste triste a chávena pousada e o olhar confortando uma flor já esquecida do sol do ar

lá de fora (da vida)

numa jarra parada (In A Palavra O Açoite)

Ângela de Almeida, poeta, investigadora e ensaísta. Nasceu em 1959 na cidade da Horta e vive na cidade de Ponta Delgada, exercendo investigação científica na

Biblioteca Pública e Arquivo de Ponta Delgada, onde está a concluir uma antologia de poesia de autores açorianos, dos séculos XVI a XX. Nasceu na cidade da Horta, onde viveu até aos 16 anos. Depois, foi para Lisboa estudar: é doutorada em Literatura Portuguesa e defendeu uma tese sobre a poesia de Natália Correia. Como ensaísta e poeta tem vários livros publicados, destacando os de poesia: sobre o rosto (1989 e 1994), manifesto (2005), a oriente (2006), caligrafia dos pássaros (2018), a janela de Matisse (2024). Também publicou dois livros de viagem e uma narrativa poética. Enquanto poeta, interessa-lhe a contemplação da palavra e a sua transfiguração no plano do imaginário, criando uma rêverie, lugar de utopia, por oposição ao mundo distópico onde vive a maior parte da humanidade. É uma honra imensa ver o meu livro Caligrafia dos Pássaros/Caligraphy of the Birds traduzido pelo Professor Doutor Diniz Borges, também autor da antologia de poesia açoriana, Into the Azorean Sea

17

fotos da autora angela correia

Comemorando Camões

Rose Angelina Baptista

Nesta época (2024-25) em que comemoramos o quinto centena’rio de Luís Vaz de Camões, a poeta Roseangelina Baptista, tem trabalho imenso neste projeto de trazer Camões em várias línguas e experiências de tradutores e escritores com raízes e ligações a várias culturas, que vivem nos Estados Unidos.

Soneto LXXXI

Luís Vaz de Camões

Amor é um fogo que arde sem se ver;

É ferida que dói e não se sente;

É um contentamento descontente;

É dor que desatina sem doer;

É um não querer mais que bem querer;

É solitário andar por entre a gente;

É um não contentar-se de contente;

É cuidar que se ganha em se perder ;

É um estar-se preso por vontade;

É servir a quem vence o vencedor;

É um ter com quem nos mata lealdade.

Mas como causar pode o seu favor

Nos mortais corações conformidade,

Sendo a si tão contrário o mesmo Amor?

Sonetto 81 Luís Vaz de Camões

Traduzione di Joanne Fisher* e Roseangelina Baptista**

L’amore è un fuoco che arde di nascosto;

È una ferita che fa male anche se non si sente;

È una contentezza scontenta; È un dolore che scompare senza ferire;

Non è voler più che volere; È un solitario che cammina tra noi; Non è accontentarsi d’essere contenti;

È la cura che guadagni perdendo te stesso;

Essere schiavo per sua volontà, È servir coloro che superano il vincitore;

A chi uccider ne vuol usar lealtà.

Ma come può causare il suo favore Nel conformismo dei cuori mortali, Quando lo stesso Amore ti è così contrario?

18

desenho de luis de camoes

*Joanne Fisher is a Canadian-ItalianAmerican author who has penned over a dozen books. She is renowned for her steamy romances, historical fiction,and murder/mysteries. She has written four Christmas novellas giving them an Italian flair.Shehasalsopennedtwonon-fiction travelguidestitled«TravelingBoomers». She loves writing short stories and has collected thirteen in Baker’s Dozen Anthology.

**Rose Angelina Baptista, a BrazilianAmerican writer, is based in Central Florida. Her recent poems have appeared inTheWallaceStevensJournal,LitBreak, and Gávea-Brown. She cocurates the AlfredLewisBilingualReadingshostedby thePortugueseBeyondBorders Institute.

Soneto 81 Luís Vaz de Camões

Traduit du portugais par Anne-Marie Derouault*etRoseangelinaBaptista**

L’Amour est un feu qui brûle sans être vu, une blessure qui fait mal, sans être ressentie; un contentement qui abrite le mécontentement, une douleur qui égare sans infliger de peine.

C’est ne rien vouloir, plus que vouloir le bien; c’est marcher solitaire parmi la foule; c’est ne jamais se contenter d'être content; c’est un savoir que l’on gagne en se perdant.

c’est servir celui qui vainc, le vainqueur; c’est être loyal envers celui qui nous tue.

Mais comment ses faveurs peuvent elles susciter dans nos cœurs mortels, un tel attachement, si lamour est aussi contraire à luimême?

*Anne-Marie Derouault was born in Paris, France and lives in Central Florida. She writes free verse poetry inspired by her love of travel, nature and human beings. She published a bilingual collection “While the poem lasts – Le temps d’un poème” and had several poems appear in Brevard Scribblers anthologies Written in the Sun and the Space Coast Writers Guild anthologies Survival and Horizons.

**Rose Angelina Baptista, a BrazilianAmerican writer, is based in Central Florida. Her recent poems have appeared in The Wallace Stevens Journal, LitBreak, and Gávea-Brown. She cocurates the Alfred Lewis Bilingual Readings hosted by the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute.

Soneto 81

Luís Vaz de Camões

Traducción de Cynthia Hall* e Roseangelina Baptista**

Sin ver, Amor es un fuego ardiente, Sin sentir, una herida que duele, un contentamiento siempre descontentado, un dolor furioso sin golpe,

C’est vouloir être emprisonné volontairement;

un querer solamente para querer, una soledad entre la gente, nunca contento cuando complacido, una pasión creciendo en los pensamientos.

19

Esclavizado voluntariamente; tu derrota, una victoria; manteniendose leal con tu asesino.

Siendo tan auto-contradictorio, como es que Amor, cuando elige, trae corazónes mortales ha la compasión.

*Cynthia Hall is the author of The Happy Muse and countless articles and edited works. A beacon of creativity and inspiration Cynthia's journey from editorial reporter to celebrated author exemplifiesher literary motto: Changing the World One Word at aTime. Shecurrentlypresidesover the Space Coast Writers Guild and is an esteemedmember oftheCape CanaveralChapterofthe NationalLeague of American Pen Women. She dedicates her work to unlocking reader's creative potential. Cynthia's Puerto Rican heritage and her grandmother's teachings instilled in her a profound love for the Spanish language. She finds Spanish a melodious, romantically expressive conduit for her thoughts and emotions, adding depth and color to her vibrant storytelling palette.

**Rose Angelina Baptista, a BrazilianAmerican writer, is based in Central Florida. Her recent poems have appeared in TheWallaceStevensJournal,LitBreak,and Gávea-Brown. She cocurates theAlfred LewisBilingualReadingshostedby the PortugueseBeyondBordersInstitute.

Sonnet 81 Luís Vaz de Camões

Translated by Diniz Borges* and RoseangelinaBaptista**

It is to yearn for nothing, more than wishing well; a solitary strolling amidst the crowds; it is a never being at ease with its pleasures; a thought gained when losing something.

Its to crave being captive by one's consent;

At the service of the winner, the conqueror; its bearing loyalty to the one who kills us.

But how can love instill conformity in mortal hearts, when love itself is so contradictory in its ways?

*Diniz Borges, a Portuguese-American from the Azores, founding director of the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute at the University of Fresno State in California. Journalist, Curator of the Alfred Lewis Bilingual Readings. He has published ten books in Portuguese and translatedorco-translatedsevendifferent books such as Through the Walls of SolitudeSelectedPoetryby Alamo Oliveira; Between Words Poetry Collection by Vera Duarte, Inner Snow PoetryCollectionbyAlberto Pereira.He has also organized several anthologiessuch as Into the AzoreanSea BilingualAnthologyofAzoreanPoetry.

**Rose Angelina Baptista, a BrazilianAmerican writer, is based in Central Florida. Her recent poems have appeared in The Wallace Stevens Journal, LitBreak, and Gávea-Brown. She cocurates the Alfred Lewis Bilingual Readings hosted by thePortugueseBeyondBordersInstitute.

Love is a ire that blazes, yet unseen, a wound that aches, unfelt within; it is a contentment that shelters discontent, a pain that maddens without hurting

20

The poetry of Pedro da Silveira: a panoramic reading (*)

Primeira Voz (first voice) collection and signals a territorial limit ("The land ends here" ) does not refer exclusively to literal geography. I believe that the island space, with its delimited borders, surrounded by sea and wind, or eternity, serves as a lever for reflection on another territory, which is that of poetry and its vocation to search for belonging that cannot be found either in the original place from whichit is launched or in any other place to which it goes. I would say that the subject of Silveira's poetics knows that the dichotomy between leaving and arriving is an insufficient solution for the meaning of a poem, which necessarily escapes the categories of perception we have of reality. A poem is a place adrift, whose adherence to historical or social assumptions is always slippery. The nonsense characterizes it - the act of saying that constitutes it inevitablydeviates from the route of what it wants to say. Nothing is new here: all literature is an act of transfiguration, of recognizing a world that has become detached from its referents and no longer belongs to them.

This may seem strange in a work that has often protested against its attachment to the ethereal and the abstract, whose concrete marks run through its sixty years of construction. A minimally attentive reading of Fui ao mar buscar laranjas (Went to the sea to pick oranges- the entire collection of Pedro da Silveira's poetry) will necessarily find traces of the particular history of Azorean life. Between Primeira Voz (First Voice) and A Ilha e o Mundo (The Island and the World), the imagery almost always revolves around ideas of passage and isolation, manifested by elements such as ports, quays, boats, steamers, and handkerchiefs, linked, of course, to the migratory movements that characterized the history of the islands in the 20th century. In this sense, the poems are woven around the throbbing awareness of the material conditions of the place from which they set out and replicate the departure movement. Were talking about the themes of poverty, smallness, being condemned at birth to an existence exiled from the world, and, undoubtedly, membership of a shared history: “(our eternal history of renouncing life, / waiting for heaven), / black history that the old people brought / from the old people of yesteryear.” So, on the one hand, theres the umbilical relationship with ancestry, and on the other, the knowledge that this is linked to a universal framework. Its the poem “That My Grandparents Left Me “and the poem “The Tears of All Famines” (idem). In addition, there are the doldrums, the monotony, the passivity of daily life on the island and the rituals that operate within it, the stories of the older people, the trivial conversations, the places where those who remain to socialize, perpetuating a marginalized existence that is alien to the places where so many others have left without returning. As a reader, I'm less interested in these marks of

21

Leonardo Sousa

historicity and more in the way they are transported, like motors, to Pedro da Silveiras poetic creation because it is there that a world of atomized existence is structured. After all, history gives place and voice to its spectral tenants and revitalizes them. Silveira says, at the start of Sinais de Oeste, in “Poetic Art”:

Now, this is my rationale, my science:

The true horizon is that of water and sky.

With the sea around the land senses, is lively, awakens from being land. (...)

-And our blood navigates us, pushes us to where it resides ( dreamed or real) within us, the Hereafter.

The soft, dragging landscape is resurrected through the poem, made up of a desire to cross the historical horizon of no future. In it, the living and the dead mingle without dispute and head for another pier, a moveable pier where I glimpse the correspondence with “the gesture of invention.” The poem is no longer fixed anywhere: itaddresses the Azorean islands, the “California’s lost in abundance.” Macau, in a text dedicated to Camões, reflects when it says that "your destiny, according to the law of the gods, is to sing as the days die among trees with impossible branches.” The poems universe is no longer one we can call true or strive for truth. Its intention is not to pass itself off as historical or sociological catechesis nor as an elegy for the messianic islands. On the contrary, it is to build a place that escapes its condition, that points to a destiny made from the deception of all

places. In other words, to set off towards a geography that can never be reached, except by mistake.

Silveiras poetry also does not stray so far from the abstract and the ethereal, although it sometimes communicates this intention. Its much more about escaping the formula, the “sexual verses” and the docile to build a poem that is a natural song of open space, unsubmissive to academic schools and practices; what I see in Pedro da Silveiras poetry that can correspond with island works of literature, whether Azorean or otherwise, is the fusion between place, biographical and historical subject - geography as an internal constituent of the individual -visible in constituent of the individual -visible in a “Sonnet of identity”,where, through the signs of stone, woods, and hardness, he reinforces his indomesticable nature, whose homeland and destiny are uncertain and indefinable. In the text with which his collected poetry ends, we first witness the disappearance of the omnipresent maritime element, only to see it transformed, “no longer blue serenity, but crisp or rebellious lead-green” Is this the passage of time, the confrontation with Death? The slow metamorphosis of meaning in any poem that can even be called that. The continuous search for the ultimate pier?

The unmistakable timbre of this writing is the search for poetry, where we know that “there is no poetry” And it is on the search for their voice or the whereabouts of the subject that embodies it that these poems are almost always built and launched towards a shifting and unstable destiny, from which nothing more can be expected than the oblivion of which all mortals will be reluctant prisoners, sooner or later, celebrated.

Leonardo Sousa. Poet

22

(*) SILVEIRA, P. 2019. Fui ao mar buscar laranjas. Instituto Açoriano de Cultura.

(Essay read at the Casa dos Açores in Lisbon, on 26.11.2022, during the tribute session to the Florentine writer and presentation of the Centenary Edition (Instituto Açoriano da Cultura): Fui ao mar buscar laranjas (Vol. I, collected poetry) and Só o esquecido é passado (Vol. II, collected prose, book I).

23

frente e verso do livro “misty paths” de pedro da silveira

Foto de diniz borges

Foto de diniz borges