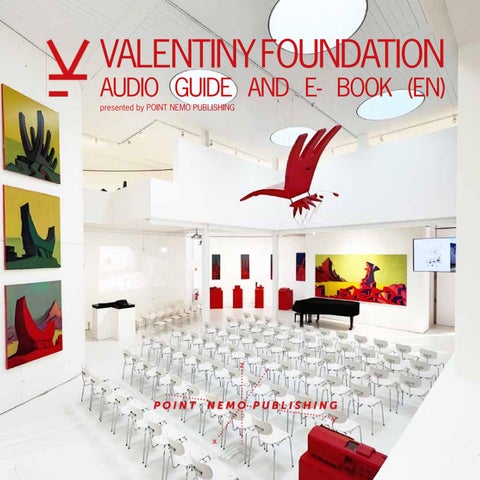

VALENTINY FOUNDATION

AUDIO GUIDE AND E- BOOK (EN)

presented by POINT NEMO PUBLISHING

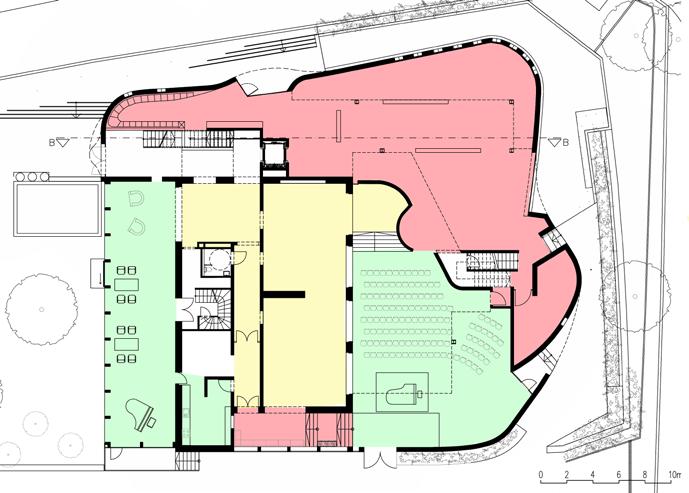

Project details

Gross site area

Site area are above ground

m²

m²

m²

Gross volume

Exhibition area

6247,34 m³

477,18 m²

Client Architect Electrical engineer

de Schengen

Structural engineer

Mechanical engineer

Safety engineer

Supervisory Office Vinçotte Luxembourg

Participating companies

Wooden structure Jean Schmit Engineering E3 Consult

Steffen Holzbau s.a.

Shell construction OBG GmbH

Glass facade Annen GmbH

Construction Site & Technical Data

THE BUILDING - KEY FACTS

PERMENANT EXHIBITION, COLLECTIONS AND GALLERY

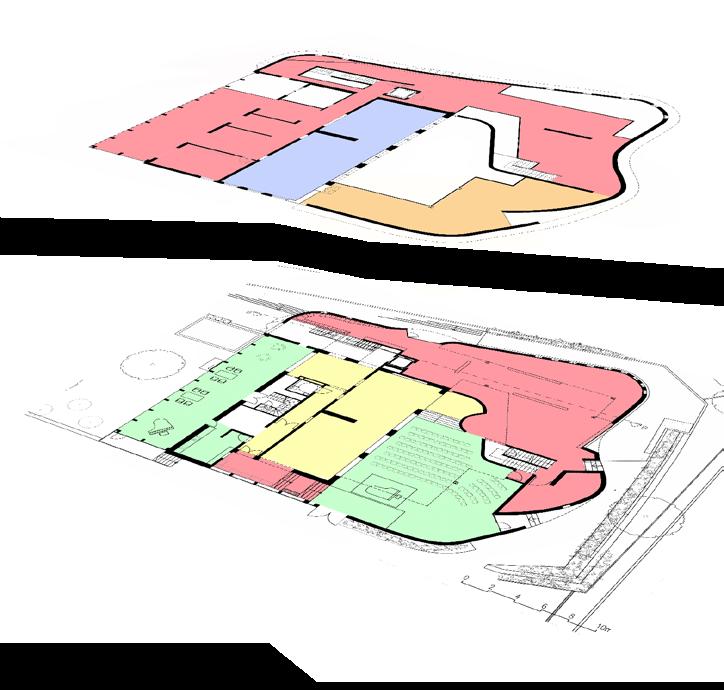

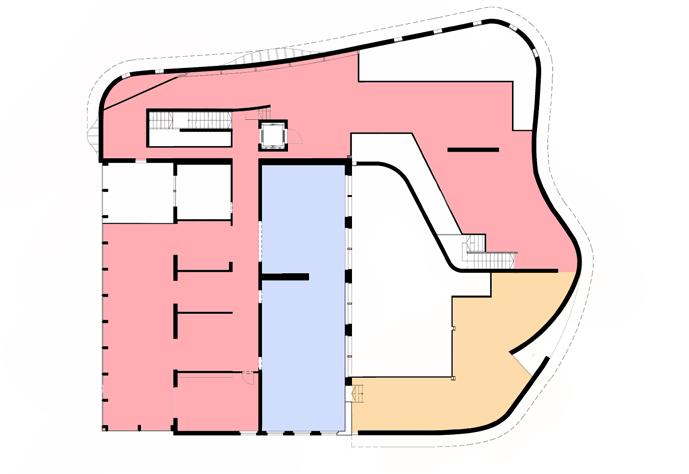

FIRST FLOOR YOU ARE HERE

GROUND FLOOR

Permanent Exhibition Edith Burggraff, François Valentiny & Valentiny hvp Architects

Permanent Loan Rob Krier & Roswitha Grützke

Collection Valentiny - Burggraff

Gallery Spaces (for rent)

Grand Hall & Bar (for rent)

THE GUIDED TOUR MANUAL AUDIO GUIDE...

As you explore the Valentiny Foundation, you‘ll encounter QR codes linking to audio tracks on key themes in the work of Valentiny hvp Architects. Across 14 stations, the series „Stories from the Inside“—written by Ian De Toffoli and based on interviews with François Valentiny—offers personal insights and untold stories behind the projects, originally published in 2021 in the context of the publidation „40 Years Valentiny hvp Architects“.

Additional stations A, B, and C provide context on the permanent exhibition, the artistic collaboration of Valentiny-Burggraff, long-term loans by Roswitha Grüzke and Rob Krier, and highlights from the Valentiny-Burggraff Collection.

Take your time, listen closely, and discover the many layers of thought, history, and creativity within the exhibition.

You’ll also find videos presenting page sequences from the book 40 Years Valentiny hvp Architects, offering deeper insights into the content on display at the Foundation. The book’s graphic design was created by Studio Polenta, the text‘s written by Ian de Toffoli.

THE GUIDED TOUR MANUAL

& E-BOOK!

Guided Tour Station 1

„For the purpose of preserving and conserving our archives and a good part of my architectural creations, we have decided, as a family, with the partners of the office and with the municipality of Schengen, to found an institution of public interest – the Valentiny Foundation.

The foundation wants to contribute – in close collaboration with other institutions such as the University of Luxembourg, the Luxembourg Centre for Architecture or the Order of Architects and Consulting Engineers of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg –to the training of architects and to missions of an architectural, pedagogical, social or touristic nature. It is a place that intends to promote architecture in the broadest sense; round tables, conferences and workshops can be held there.

Together with my friend Rolf Tarrach, former Rector of the University of Luxembourg, we came up with the idea that the students of the Master in Architecture could use some of the areas as drawing workshops. This conception was fully compatible with the university‘s didactic philosophy of creating university cells across the country.

This would have been beneficial for the Schengen municipality and very attractive to foreign students, who would have benefited from the European fame associated with the name Schengen.

Alas, as is sometimes the case in this small Grand Duchy, political decision-makers are not always up to the task. After a change of government, the implementation of this idea was suspended.

As the independence and freedom of university education are apparently not a given in Luxembourg, we have had to change our concept.

With the hiring of my brother Fernand Valentiny as Director

of the foundation, the rules have changed. His entrepreneurial spirit and energy have enabled us to develop a much more effective operating strategy. Little by little, our range of activities multiplied and diversified, and now includes three main lines of business.

First of all, we offer a permanent exhibition of my sketches, drawings, sculptures and paintings as well as plans, models and videos of our architectural products. Thus, over 4,000 items are available in our archives.

Some areas are reserved for other artists and speakers, who can rent the premises according to their needs.

Finally, concerts and other cultural events are regularly organised at the foundation, given that it features a kitchen, a lounge area, a garden and a large hall with good acoustics.

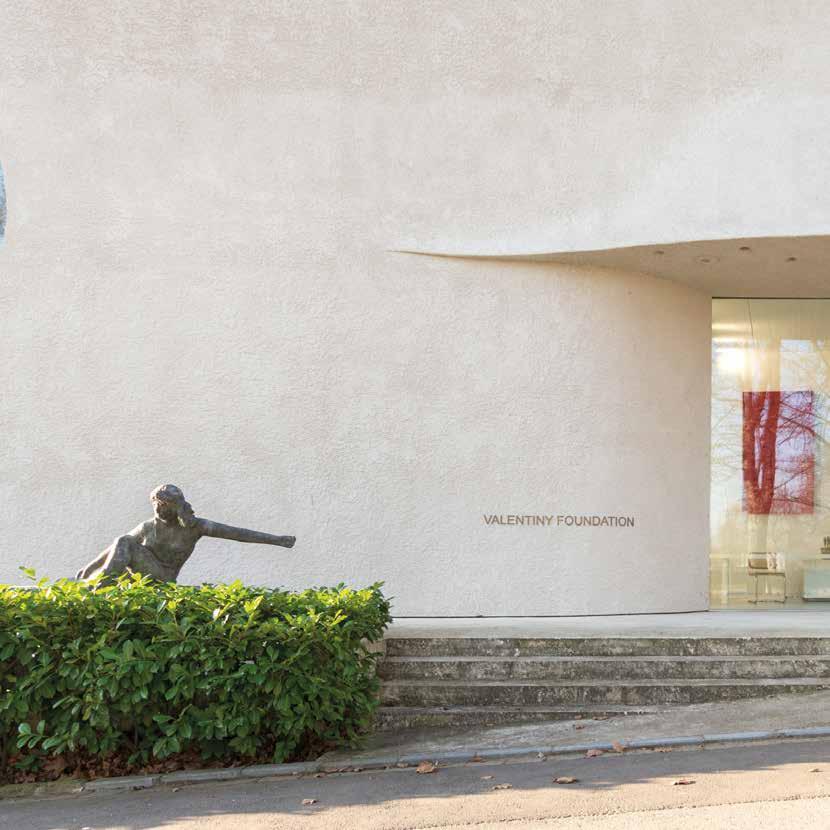

The formal language of the Foundation is in line with other public buildings that our office has designed in the Moselle region, and can be recognised by its homogeneous façade covered with the traditional Schengener Putz, which we will subsequently discuss in greater detail.”

Francois Valentiny

The Valentiny Foundation

34 Wäistrooss

2015-2016

Guided Tour Station 2 - Valentiny hvp Architects

„Hubert Hermann and I studied together. We were both in Wilhelm Holzbauer‘s Master class at the University of Applied Arts (Universität für angewandte Kunst) in Vienna. I remember that our relationship was rather distant, to begin with. Then, over time, we realised that we shared certain values, a certain vision of the world and the profession, and a mutual respect gradually took hold.

In 1980, we took part in our first major joint project, the International Building Exhibition or ‘IBA’ Contest (Internationale Bauausstellung) in Berlin, where we then built our villas on Rauchstraße with all the well-known architects of the time – a project I will elaborate on later.

It was then that we decided to set up an architectural office together, first in Vienna, then in Luxembourg, as the number of orders increased. While Luxembourg is my home country, Vienna remains my artistic domicile. We started working on our first projects, such as the café-restaurant Leo in Mödling, near Vienna, or the maison Ruppert in Schengen. These projects were developed in Wilhelm Holzbauer‘s office in Amsterdam, where we were working on the opera project he was in charge of.

In the mid-1980s, we began to receive more and more projects, and our lives suddenly took on an accelerated pace. We commuted between Amsterdam, Berlin, Luxembourg and Vienna in three-week cycles for several years – until our children had to go to school.

At one point, we had the opportunity to take an office in Luxembourg‘s capital, which we had to share with another architectural firm, Paul Bretz and Stan Berbec. But, as is sometimes the case, these two partners separated in 1988, and the opportunity to be in this office space suddenly vanished. I have to admit that I was not unhappy about it: I was not very enthusiastic about the idea of settling in Luxembourg City. This bourgeois town is too small, too cramped for me. I had the impression that life was more ‘open’ in the countryside, in my native village. I felt freer there. What’s more, I like the contrast between Vienna and Remerschen, between a real big city and an authentic village.

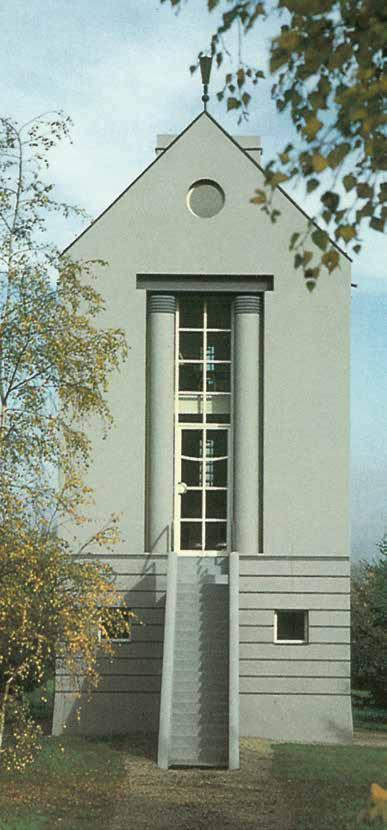

My father gave me a plot of land, on which our office is located today. It was a long and narrow plot. I immediately had the idea of

a three-storey house adapted to this location, like a foreign body amidst nature – all very symbolic, very classical. I had in mind this image of Vienna‘s architecture, which can be recognized from afar on the Ringstraße: the neo-Gothic volumes of the city hall and the neo-classical parliament designed by Theophil Hansen, which was directly inspired by Greek architecture. That‘s the reference I was thinking of when I designed our office on my ancestral lands.

In Remerschen, in order to demonstrate an urban character, it meant a lot to me that fragments of the columns of the structure, as well as its tympanum, could protrude from the surrounding nature.

There is also, in the design of this office, a strong reference to German Romanticism, a movement that began in 1770 and lasted until the mid-1850s, affecting literature, but also music and the visual arts. This period saw the sometimes artificial reconstruction of ruins, which can still be found today in some cities – just think of Peacock Island (Pfaueninsel) on Berlin‘s Wannsee, which is a perfect example of Romantic architecture. At the time, it was a question of arousing dreamlike memories, a certain nostalgia (Sehnsucht in German), a reverie.

There was also the will to create harmony between the built environment and nature through plant and green areas. Within the limits of my abilities, I have carefully maintained and cultivated, even domesticated a certain amount of nature surrounding the office for the past four decades. I like the dialogue between construction and vegetation; I admire its capacity for irrepressible exuberance.

I wanted to create an ideal place, a harmonious place, where nothing would bother me, so that my desire to be here, to work in this office would not diminish over the years. I always like being here.

That’s why I have set up a pavilion at the end of the garden. There, I can reflect on my own creative processes. This pavilion is a small construction made of glass and wood, but covered with a second ‘skin’: a canvas of steel slats, like the one we created for the KPMG building in Kirchberg. I often start from the principle of reusing ideas that have already been tested on a small scale.

The growing number of projects from outside the country has also led me to travel a lot around the world. It is also this contrast, between far away travels and reunion with this village where the winegrower walks by and takes a look at what I‘m doing, that means a lot to me. For forty years, it has remained unchanged.

The office has been extended a few times over the years. The third extension, where my personal workspace is located, is connected to the original building by a sort of covered bridge with a roof, which was added fifteen years later. It is a sturdy, rudimentary steel and glass structure, for high transparency and to let in natural light. The trees have grown in the meantime and have almost tripled in height to sixteen metres, hiding all the buildings. Everything is natural, basic, in this building. We do not have air conditioning: only fixed protective slats protect from the sun.

I am always busy trimming one part of the vegetation or letting another grow. Over the years, I have gained some experience; I have gained understanding as to how nature appropriates space, or even invades it. Animals came too, over time. Underneath the building, foxes and badgers share a den; you can see traces of wild boars in the morning: there is life here. It is precisely this exuberant invasion of nature that makes this romantic spirit come to life; it is what we see in the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich. All in all, that is what I like about this place.“

Francois Valentiny

Guided Tour Station 3

„Thanks to the Amsterdam Opera House project, on which we were working with Wilhelm Holzbauer, we were able to gather our first experiences in the field of theatres, concert halls and opera houses. This work opened up a magical world for me.

Subsequently, taking part in the competition of the Luxembourg Philharmonic Hall was an obvious choice. I remember that in 1997, the Philharmonic Hall area was not yet defined at the urban level: it was only home to a motorway and a first tower for the European institutions. The first step was to develop this area of Kirchberg, which resembled a vast plateau with a few isolated buildings, crossed by an expressway that had nothing of the urban character of the avenue it has today.

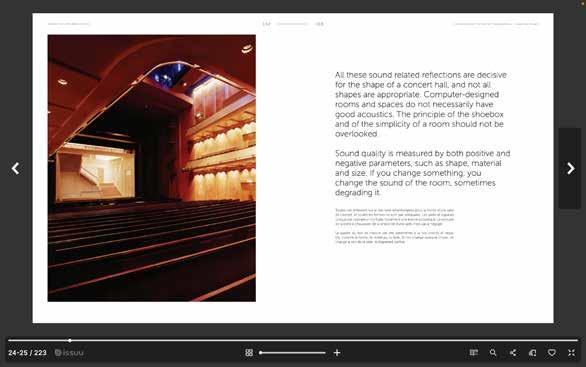

I learned a lot during this period; I was able to develop my thoughts on concert halls, the philosophy of spaces with curved walls and the advantages of shoebox-shaped halls. I was able to continue to reflect on the relationship between the height, depth and width of a hall and its acoustics, on the complexity of an orchestra pit and on the location of the choir behind the orchestra.

An opera house and a concert hall are significantly different. The former is judged on purely acoustic criteria, and the latter must also act as a theatre. In terms of functionality, opera houses are far more complex. They feature stage sides and an underside, workshops, machinery and a backstage, like a miniature city in the background. A concert hall is mainly defined by the space devoted to the orchestra and the audience.

In the olden days, operas were a major event with an entertainment function. Before and after the show, people dined, drank, talked in front of or in the dressing rooms. Nowadays, all these activities are well separated; the emphasis is on the performance itself.

Over the years, I acquired the necessary know-how regarding the curves and inclinations of the walls, so that the sound comes from everywhere. I sometimes benefited from close collaboration with experts: Müller Akkustik in Munich, or Nick Edwards from London, whom I met in Bonn as part of the Beethoven Festspielhaus project, and with whom I collabo-

rate regularly.

Over the last two centuries, the technique of the instruments has improved and the halls have become larger and larger. The perception of the music of Handel, Mozart and Beethoven, designed for palace vestibules that could accommodate up to three hundred people, was therefore totally different from that which one can have today. We used to listen to music in a different way. We should bear in mind that Beethoven never heard his music in such a monumental way as we hear it today.

However, it should also be pointed out that the halls are better furnished today than in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and of course have a different resonance. Sound varies according to the size of buildings. Nowadays, you can no longer play a symphony with a hundred musicians in front of just two hundred people. In large cities, concert halls can accommodate 1,500 or even 3,000 people. So, the question is: how do you play a symphony written for a small hall in a gigantic hall?

All the rooms have an acoustic profile that can be identified through hearing. There is a world of difference between the Berlin Philharmonic and the Vienna Opera. When the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra plays in Berlin, it does not immediately find its way there – and vice versa. The Haus für Mozart in Salzburg, which we built in 2006, is a hall that reverberates a hard sound; you don‘t have to play it as hard as was traditionally the case and the sound feedback alone can make the orchestra play differently.

All these sound related reflections are decisive for the shape of a concert hall, and not all shapes are appropriate. Computer-designed rooms and spaces do not necessarily have good acoustics. The principle of the shoebox and of the simplicity of a room should not be overlooked.

Sound quality is measured by both positive and negative parameters, such as shape, material and size. If you change something, you change the sound of the room, sometimes degrading it.

Nowadays, tenders often ask for a sound ‘like at the Musikver-

Theatres, Concert Halls and Opera Houses

ein in Vienna’ or other major references, but such comparisons are never called into question, especially when it comes to technical parameters. In Vienna, you need to take trams, bells, aeroplanes and pigeons into account. Often, places are not fully soundproofed. In some of the new theatres, you can no longer hear anything from the outside, meaning that any false note or coughing fit turns into a tragedy. Reaching perfection is not always desirable, and it may actually constitute a flaw.

I have taken all these parameters into account in many concert hall and opera house projects, such as the Musiktheater in Linz. We took part in this competition shortly after the Philharmonic Hall’s. We proposed to break the geometry of the building, with the intention of orienting the entrance hall and the gallery towards the Danube rather than towards the city, and to build an asymmetrical hall. I had to learn the hard way that asymmetrical halls cannot be built with public money.

It is also worth mentioning the Stavanger Concerthuis, a concert hall built in an industrial zone by the sea in Norway, or the Busan Opera House, a building in a megalopolis, which can show several productions simultaneously as it features several halls – the organisation of the spaces behind the stage proved to be a real logistical feat. There is also the Meistersingerhalle in Nuremberg and the Haus der Musik project in Innsbruck, whose urban structure was more of a challenge than the hall itself. Halls are correctable, but town planning is not. There were thus two layers of work at hand: one that takes into account urban planning and one focusing on acoustics.

These projects are somewhat similar, in the sense that one must constantly be in search of a certain dramaturgy of the place, without forgetting the audience’s presence. The audience is as much a part of the concert as the musicians and the sound produced. From the very beginning of the design, it is a question of determining a position, a layout, which obviously differs according to the type of building to be designed.

The creation of concert halls has become a real need for me. The joy it brings to me does not diminish with the years, unlike the joy of building homes. Even after four decades, designing concert halls never bores me and continues to fascinate me.

A new project for a multifunctional hall in Russia, in the Urals region, has just been confirmed: I am already looking forward to start working on it.“

Francois Valentiny

Guided Tour Station 4

EN „The Beethovensaal project in Bonn was broken down into three stages, each of which was subject to a new contest between a dozen competitors, such as Richard Meyer, Zaha Hadid, David Chipperfield and Arata Isozaki. As we were able to get ranked in the top two in every round, this project kept us busy for eight years. I sometimes find myself thinking: how can you work so many years on a project without ending up with a positive result?

Achieving a project is certainly the main aim of our profession, but the act of building is not comparable to the fascination of pure creation, nor to the eroticism that radiates from it. For eight years, I was extremely interested, even fascinated by this project, to the point that I would go to sleep at night with a question and wake up in the morning with the answer.

Although Bonn became the capital of West Germany after the Second World War, this small bourgeois town never got out of Cologne’s shadow. Due to a lack of courageous decision-makers and politicians, the project was abandoned after a decade of political wrangling.”

Francois Valentiny

Beethovensaal - Bonn

Life, Education, and Work of Edith Burggraff Station A

LAC (Cercle Aristique Luxembourg)

Schwebsange

Caves Sunnen

Caves Zenner

Teilnahme an der Ausstellung Womenart in Shanghai

Dauerausstellung im Bistrot Gourmand in Remerschen

Dauerleihgaben und Ausstellung von Holz- und Bronzeskulpturen, sowie Zeichnungen in der Valentiny Foundation in Remerschen

in Vianden (Luxembourg) als eines von vier Kindern von Sanny Huss und Emile Burggraff geboren

Solfège und Viloncello am Konservatorium in Luxembourg-Stadt

Pensionnat de la Sainte Famille LuxembourgFeldgen

Centre d‘enseignement Professionnel de l‘Etat Luxembourgeois, Paramédical

Diplôme Spécifié, Section des Beaux-Arts et Arts Décoratifs

Diplom der Fachausbildung zum Werbegestalter, Wien, Österreich

Gasthörerin an der Uni Wien, Kunstgeschichte

Grafik, Dekoration und Werbungsgestaltung für das A. Gerngross Kaufhaus in Wien

Arbeiten als freischaffende Künstlerin in den Bereichen Malerei, Zeichnung und Holzskulptur

Autobahnauffahrtsschilder für Ponts et Chaussées Luxembourg

Sommerakademie für Volksschulkinder in Esch-sur-Alzette, Schwerpunkt Architektur

Gestaltung der Bar des Bistrot Gorumand mit neun Bacchus-Malereien

Diverse Reisen Shanghai, Peking, São Paulo, Porto Seguro, Marrakesch und Ägypten.

Burggraff & Valentiny

Exhibtion Catalogue

Seiten: 200

Format: 210x210

ISBN 978-2-9199670-6-3

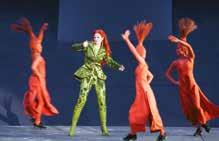

Guided Tour Station 5 - Scenographies

„After building the Trier Tower, when the city of Luxembourg became the European Capital of Culture for the second time, I was approached to design the scenography for several operas that were to take place in the Trier amphitheatre. This structure is one of the ten largest Roman amphitheatres. It is located on the edge of the Roman town of Augusta Treverorum – built in the first century AD –, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

This work was unknown to me until then, even though classes in scenography and even costume design were given at the Universität für angewandte Kunst (University of Applied Arts) in Vienna. Lagerfeld was in vogue in the 1980s.

I met the director, Bisser Schinew, who explained to me at length his conception of the different scenes. A new world was opening up to me. When it comes to opera, I have noticed a real dialogue between the different artists collaborating. Bisser Schinew and I became friends, but he unfortunately passed away a year later.

My first opera was Andrea Chénier, a work in four acts by Umberto Giordano on a libretto by Luigi Illica. It is inspired by the life of the famous poet André Chénier (1762-1794), the great inspirer of Romanticism in France and even beyond, who was guillotined during the French Revolution. It speaks of failed idealism, the dangers and abuses of power, and the impossibility of living happily in difficult societal conditions.

My idea was above all to avoid an overly historical scenography. I therefore based my efforts on a narrative architecture whose elements defining the space were constructed according to my sketches before being enlarged to full scale.

I wanted to create a contrast between a certain abstraction and the establishment of clear references and information for the viewer. The shapes I invented were close to fairy tales, featuring a certain dreamlike quality. The drawings I made in 2007 were very expressive; some were then made in different colours – I had, for example, come up with a range of grey and crimson red colours – with removable sides to make the best use of the space. Everything was easily manipulated and modulated. I was accompanied by a competent team, in particular by the technical director and the lighting director. Once the lighting director started to create

his lights, he made me change everything according to the angle with which he projected the spots on the set. Seeing how light can change everything or bring out nuances was a rewarding experience for me as an architect.

I worked on the following opera in 2007: Samson and Delilah, composed by the Frenchman Camille Saint-Saëns and based on a libretto by Ferdinand Lemaire. It tells the biblical story of Samson‘s seduction by Delilah, who cuts his hair in order for him to lose his superhuman power. This opera and the next one, Œdipus Rex, were performed at the tenth edition of the Antikenfestspiele summer theatre and opera festival in Trier’s Roman amphitheatre. For the performances, the public galleries were reintegrated into the rows of the theatre and the dramatic action placed back on the stage, with a view to go back to the amphitheatre’s antique look...“

François Valentiny

Guided Tour Station 6

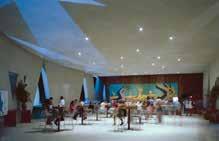

The creation of the Teatro L‘Occitane in Trancoso, Brazil, is a fascinating story with many ramifications.

A period of intense work began for me shortly after the start of the construction of the Haus für Mozart in Salzburg. At the beginning of 2004, while I was working on two opera scenography projects in Trier and the transformation of the Kongresshalle concert hall in Saarbrücken, I was appointed curator of the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

During the preparations for this event, I went to Salzburg to celebrate, as you sometimes do, the end of the season with a dinner on stage with the artistic team and some close friends. Sabine Lovatelli, a great lady of the classical music scene in South America and founder of the auditorium Mozarteum Brasileiro in São Paulo, sat next to me at the table. This meeting marked the beginning of a great friendship. We met again for some Easter Festivals (Osterfestspiele) in 2005, and subsequently on a regular basis.

During the winter of 2006-2007, Edith and I responded to an invitation from Sabine and Carlo Lovatelli to stay at their home in Trancoso, Bahia.

Bahia is a paradise on earth. It was on these beautiful Terravista beaches, surrounded by the huge Atlantic forest, that the navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral landed on the Brazilian coast on 22 April 1500, and where later, in 1583, Jesuit priests founded the Catholic church known as São Baptista dos Indios de Trancoso.

In the course of a dinner in this magical place, we met Dominique and Reinold Geiger - owners of L‘Occitane en Provence (an international retailer of beauty and home products) and great music lovers – by chance.

Throughout the evening, the conversation revolved around music, and more specifically about the personal relationship each of us had with our favourite musical theme. At one point in the discussion, Dominique told us that, since she was young law student, she had dreamed of creating a festival similar to the one in Avignon someday.

That night, circumstances were conducive to making that

dream come true. Sabine and Carlo had contacts with many musicians, while I was able to support this wonderful idea thanks to the experience I had gained in concert hall design projects, especially the one in Salzburg. Drenched with good wine, the tropical night was very long, and around dawn, the Musica em Trancoso festival saw the light.

The next day, we found a picturesque little valley opening out to the sea, boasting natural acoustics. I immediately started drawing, and four days later I was able to present the completed proposals at another dinner. One of the guests, a contractor, offered to take care of the necessary environmental authorisations. The authorities turned out to be very cooperative as the construction was ephemeral. They only asked us to place folding seats, so that the existing plants could get rain and sunlight during the day... ”

Francois Valentiny

Teatro l‘Occitane

Guided Tour Station 7

„One of our very first single-family home projects was completed between 1985 and 1987 in Schengen for the Ruppert family. There, we converted a barn overlooking the vineyards in the centre of a small Moselle village into a functional winegrower‘s house with an apartment and cellar. The façade was made of dry stone: a very classical structure. The design incorporated a void in the building itself, with a large centrally located dining room. It stood as a central area around which all the adjacent rooms came together at various levels, which was further highlighted by two skylights.

Based on this shape of the central room around which the other spaces gather and cluster – I consider this idea to be the original shape of all dwellings – we have built half a dozen other similar projects. A central space that is open at the front, featuring winter gardens at the back and lightwells to let in light from above; an idea we still use today in many buildings.

Another feature of the houses we built from 1980 to the year 2000 is the pitched roof with a semi-circular tympanum at the front, for instance for the Bortuzzo House in Bereldange, built between 1988 and 1989, and before that for the Reuter House in Bech-Kleinmacher, built between 1985 and 1987. With regard to the latter project, you can see from the floor plan that the staircase and the adjoining rooms are combined into a single element, so that you can walk around the whole house openly. The sequence of small and large rooms, closed and open rooms, and the interweaving of volumes characterise the diversity of the interiors. In reference to the Raumplan by the Austrian architect Adolf Loos (1870-1933), the construction follows a centrifugal spatial model, which results in a multitude of recess-like annexes on either side of the various areas. The height of each room goes hand in hand with its function.

It is a theme that we have developed and used as an offshoot over the years, like a brand or a symbol.

We then changed our ways and started building all-concrete houses, including the roof, like the Haus am Seitweg in Klosterneuburg, Austria - a private house developed in 1997. The southern side of the house is made of wood, while the whole structure has been raised to fit out the terrace.

In Wellenstein, we built the Hirtt-Gasper House, which was completed between 1999 and 2001. It was based on the theories of the Greek philosopher Socrates – theories later taken up by Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), philosopher and architect of the Quattrocento – of the Mediterranean-style house, with a roof raised on the side where the sun shines, so that the rays can penetrate deep into the house. It is a two-storey, funnel-shaped house, facing south to capture the sun.

As is often the case when an idea proves successful, we continued to develop this type of house in the context of many subsequent projects.“

François Valentiny

Single-family homes

Guided Tour Station 8

„The IBA was followed by a very long phase during which we carried out a lot of residential construction, particularly in Potsdam, where we built residential blocks 15 and 33 in Kirchsteigfeld. In Vienna, we designed the apartment building on Anton-Bosch-Gasse in Floridsdorf and the Trinkhausstraße apartment building in Simmering, as well as the five high-rise buildings in Halle-Neustadt. As for our work in Luxembourg, the residential complexes in Dudelange and Réimerwee in Kirchberg should be mentioned.

The residential construction market is paradoxical, and especially the single-family home market. You could say that it drains both a lot and little money at the same time. Some houses nowadays stand out because of a major investment in materials and interior design; however, seen from the outside, their appearance is only mediocre and does not attract attention. Other houses are very expensive and stand out as unique in the neighbourhood, but inside, everything is built too rationally: you quickly feel cramped. On the outside, they look flashy; on the inside, they look like workers‘ houses from the 1950s.

As for residences and apartment buildings, if it were up to me, I would build them with bodies of buildings linked together by open corridors as their main characteristic, all inspired by what was done in Vienna in the 1920s, or what is still done today in Scandinavian countries.

However, in our regions, I am under the impression that discussion is barely possible: project owners always prefer a traditional design to searching for something adapted to the needs of our times.

The public sector, in particular, does not like to deviate from its tailor-made programme for ideal and typical families – even though there are less and less traditional families.

A notable exception is the construction of the residential block in Dudelange, carried out in the 1990s, for which we designed open corridors. Today, they are covered with lush vegetation and look like green tunnels. An inclined structure forms a semi-transparent wall, like a privacy screen in front of the eastern façade, where the railway tracks are located. The fact that the

steel stairs and the corridors have been moved outwards means that construction costs have been considerably reduced. Building materials remain untreated and are limited to plaster, sheet metal, wooden windows, wooden panels, galvanized steel, concrete paving stones laid in a sand bed and bare screed in outdoor areas.“

François Valentiny

Residential Buildings

Museums and Galleries

Guided Tour Station 9

„When building offices, homes and sports halls, there is always a framework to comply with. In the latter case, for example, you have to think about the sports courts and the spectators. These important details are taken into account in a rational way: there is no need to set up a whole mythology for the realization of such projects. When it comes to housing, architects often work for an investor who wants to make money. It is therefore about creating a product without symbolic significance – an everyday object, if you like – with no real difference from a car, for example. The architects work their way through by ticking boxes.

The projects that have been generated lack a mystical element. Such an element is a must for museums and galleries. Visitors entering a museum or gallery must be able to leave the real world behind, if only for a short time. A museum or gallery should function as a break from the everyday, where the visitor can concentrate on what we have to offer, without being distracted by the outside world.

But for that to be possible, the given space has to allow it. Design therefore has a very important role to play, especially in museums of contemporary art, where it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between what belongs to the design of the museum and what is an object of art.

Architects must therefore find the right balance between what will later be exhibited in the museum or gallery they are building and the place in itself. Indeed, the danger of stealing the spotlight from the works exhibited is very real if the structure and design of the site outweigh its content. In exhibition rooms, visitors must be able to immerse themselves in the art on display and not be distracted from it. The ability to find this balance lies in the irrational, the mystical; a certain aesthetic sensitivity for a space.

It is not simply a question of volume: the priority must be the perception of space.

It does not mean either – as is often heard – that ‘form follows function’. This expression means nothing in the realm of architecture, especially when it comes to the creation of public institutions such as museums. Museums do not simply have a function that is found as is, according to a preconfigured scheme. Its

primary function must be that of a cultural and social expression towards the outside, towards the urban public space, towards the city. Architecture is a public art.

You thus need to have a different perception of the rules of classical functionality. Simplified schematism – which in German tends to be called plakativ – is a misunderstanding that could perhaps be attributed to the Bauhaus. This schematism should not belong to architecture, because it is reductive, too superficial. This is how ephemeral trends emerge.

But trying to discover the mystical element behind the function of a structure also raises the question of its added value.

Designing a gallery, for example, is not like designing a museum. In a gallery, the art on display changes regularly. It is more about staging the spectator. Neutral spaces that are not too ‚strong’ must be created...“

François Valentiny

Guided Tour Station 10

„During the German Romanticism period, elements often of religious or political significance, such as towers, artificial ruins and monuments appeared in natural settings. These constructions not only served as a landmark in the landscape or an aesthetic value in the composition of an ideal landscape, but were supposed to induce a kind of suggestive reverie in visitors. They symbolised the triumph of time over the work of men, and visitors, who thus kept them in their memory, associated them with a specific place. These monuments presented a real stratification of meaning. They were spiritually, politically and culturally interpretable.

These monuments are therefore supposed to both stimulate thoughts and serve as landmarks, especially in an urban landscape. When Pope Sixtus V, the sovereign pontiff from 1585 to 1590, had the Vatican obelisk – an Egyptian obelisk, transported to Rome by Caligula to adorn his new circus – moved to the place it now occupies on St. Peter‘s Square, and then had three other obelisks erected on St. Mary Major Square, in front of the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran, and in the middle of the Piazza del Popolo, he thus marked out the city of Rome. It was a sign of strong political leadership.

My admiration for towers probably began with the tour SaintMarc, a rectangular tower that served as a tea house for the Collard family from Schengen. I remember that back in 1984, while I was working in our first Hermann & Valentiny office in Vienna, I suddenly felt like calling the mayor of my native village in Luxembourg to ask him whether I could transform and rebuild the tower and then rent it.

My call convinced him and I was able to restore the old building. I closed the top floor with glass and decorated the interior as if it were a tent, using ropes, as was done in the eighteenth century, in nature, to protect oneself from the wind or the sun during a pastoral afternoon. I then designed the furniture in the same spirit. My first workshop was ready. After Vienna, this place was ideal for me, boasting a breath-taking view of the Moselle and the vineyards of the ‘Land of the Three Borders’.

This experience has shaped and strengthened my architectural philosophy: since then, I seek to recreate this ideal place in all

my projects, from our offices to large public buildings.

When, a year later, I received the commission to design the tour du mont Saint-Jean in Dudelange, I wanted to create a panoramic tower from where people would see the entire surrounding landscape, as well as the archaeological site below and the ruins of the old castle. Contemplating the ruins instils that romantic reverie that nothing is supposed to disrupt when you are at the top of the tower.

Based on these experiences, some twenty years later, I built the Turm der Träume und Sehnsüchte in Trier for the horticultural exhibition Landesgartenschau Trier.

The idea derived from a gift from the city of Luxembourg to the city of Trier. This project was commissioned by the Urban Planning Department. It was to be built on Petrisberg hill, which is very popular for its city views a good 100 metres below. It is located to the east of Trier‘s city centre, not far from the university, where former barracks erected in 1936 once stood, including the infamous Kemmelkaserne, which housed a prison camp during the Second World War. One of its most famous prisoners was the French writer Jean-Paul Sartre...“

François Valentiny

Landmarks

Guided Tour Station 11

„Nowadays, the Moselle region – where Remerschen lies, which is where our office is located – has great appeal for many tourists, with its picturesque landscapes and villages, as well as its orchard plantations that stretch as far as the eye can see in the open Moselle valley. As early as the fourth century, the Latin poet Ausone sang about the beauty of this place, at a time when the valley belonged to the Roman Empire. The region has had a wine-growing tradition since the Celts, Gauls and then the Romans, who cultivated vines here before the monasteries took over in the Middle Ages.

Winegrowing in Luxembourg runs along the Moselle valley, one of the northernmost regions in Europe for the cultivation of vines. It benefits from a microclimate that raises average temperatures by one or two degrees Celsius. Forty-two kilometres from Schengen to Wasserbillig, Luxembourg‘s vineyards cover more than 1,235 hectares on the slopes of the Moselle, which also serve as a border between Luxembourg and Germany.

In the twentieth century, the vineyards diversified and developed following the foundation of the Wine Institute in Remich (1925) and the creation of the National Brand (1935). Since 2014, Luxembourg wines and sparkling wines have been marketed under the label ‘protected designation of origin – Luxembourg Moselle’. The grand-ducal winegrowers of the many estates cultivate their own style of winemaking, the most common grape varieties being rivaner, pinot gris, auxerrois, riesling, pinot blanc and pinot noir. Nowadays, the Moselle inhabitants, who like to gather in their pubs, are proud of the local production. They consider their annual wine festivals as sacrosanct and are full of zest for life.

As my family has its roots in the region, it was only natural that we were interested in projects related to the winemaking tradition, even though the construction or refurbishment of wine cellars is not an easy architectural exercise.

Few common denominators exist for these different projects, in particular because of the geographical location of the structure to be put in place – the nature of the soil, in particular, may be limestone in the north of the Moselle or clayey marl in the south.

We have worked for some large Luxembourg winegrowing fa-

milies, such as the one that runs the Henry Ruppert estate; these projects are often very closely monitored by the Ministry of the Environment, as well as by the project owners with whom we work. For each of them, the aim was not only to promote the image of the winery that had launched the project, but also to contribute through the architecture to the image of the wine estate, as well as to ensure the quality of the construction. The redevelopment of the Henry Ruppert estate‘s wine cellar was particularly complex, due to its location high up on Markusbierg hill in Schengen.

The concept of the new cellar strictly follows the stages of wine production. This means that the path of the bunch travels through the different functional zones, arranged in space from top to bottom: the grapes arrive from the top of the cellar, then fall to a lower level to be pressed before moving on to the first fermentation in vats, then to storage in barrels, and finally to the bottling process.“

François Valentiny

Viniculture

Anna Valentiny (Editor)

40 Years

Valentiny hvp Architects

Stories from the Inside

One box with Five Books / Pages : 2 150

Format : 488 x 290 mm

ISBN 978-2-9199670-9-4

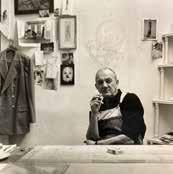

Life, Education, and Work of Francois Valentiny Station A

„Kleine Galerie“ Wien, A

Cercle Municipal de Luxembourg Forum Stadtpark Graz, A Gropiusbau IBA Ausstellung Berlin, D

Galerie Clairefontaine à Luxembourg-Ville, L

als erster von zwei Söhnen von Jeanny Harter und Proper Valentiny in Remerschen (Luxembourg) geboren

Architekturstudium an der Ecole d’Architecture de Nancy (FR) und an der Hochschule für angewandte Kunst in Wien (AT)

2002-2017

2004&2006

2006–2007

Abschluss Magister architecturae in der Meisterklasse von Prof. Holzbauer an der Hochschule für angewandte Kunst in Wien (AT) 1980

Partner von Hubert Hermann, Gründung der Architekturbüros Hermann & Valentiny in Luxemburg und Wien (LU, AT)

Assistent an der Internationalen Sommerakademie in Salzburg (AT)

Architekturbiennale in Venedig zusammen mit Hubert Hermann (IT)

Gründer und Herausgeber der ersten Luxemburger Architekturzeitschrift adato (LU)

Luxemburger Kommissar für die Biennale in Venedig

Präsident der Fondation de l‘Architecture et de l’Ingénierie in Luxemburg

Konzeption des Luxemburger Pavillon The green heart of Europe für die Weltausstellung in Shanghai (CN)

Professor für Community Planning und Green Architectural Design an der DeTao Masters Academy (DTMA) und Shanghai Institute of Visual Art (CN)

Gründung des Festival Música em Trancoso –MeT in Bahia (BR), zusammen mit Sabine und Carlo Lovatelli, Dominique und Reinold Geiger

Umstrukturierung des Büros und Geburtsstunde von Valentiny hvp Architects mit den Partnern Mag. Arch. François J.V. Valentiny, Dipl.Ing. Arch. Axel Christmann, Dipl.Ing.Arch. Daniela Flor, M.Arch. Jeanne Petesch and Architect D.E. Laurye Pexoto / seit 2023 auch M.Arch. Anna Valentiny

Gründung der Valentiny Foundation (LU)

Guided Tour Station 12Educational Buildings

„The educational building sector has changed drastically since the advent of modernity in architecture, in other words since the beginnings of the Bauhaus in the early twentieth century.

Prior to that period, schools, university campuses and colleges could be identified from afar. The purpose of those places was the transmission of knowledge: the most important mission of a society, a true cultural act that defined future generations, those who would carry the society to come on their shoulders. It gave schools a solemn character, power.

For societies, the location and expression of a school was part of its power, its influence.

High schools in metropolises stood out strongly from one another and could be easily identified in the urban landscape, as can be seen in Paris for example, through famous high-school establishments such as the Lycée Henri IV or the Lycée Louisle-Grand.

Nowadays, the situation appears to be somewhat paradoxical. On the one hand, the transmission of knowledge has become so self-evident that politics and society in general regularly end up underestimating its value and significance. On the other hand, municipalities or institutions that want to build a new school do not lack financial means, at least in Luxembourg. The result is often an imposing building, equipped with all the necessary technological gadgets; but above all a representative building, a medium through which these municipalities or institutions attempt to create their image. However, the impressive size of the building does not conceal a profound lack of reflection on the very spirit of what is built, as well as on what is done inside.

It is regrettable that the architectural modernism of the early

twentieth century made educational buildings insipid. Nowadays, people struggle to identify them in the urban landscape.

When we build schools, we try to present a response to this insipid trend by proposing open, transparent structures, both inside and outside the school. We offer views of the outside, of the playgrounds, of the green areas. While respecting the function required by the various classrooms, from language or mathematics classrooms to sports halls and chemistry laboratories, we offer places that no longer frighten students as much. We offer buildings that are less threatening, less solemn, less stifling than blockhouse buildings with their almost military rigour and harsh forms.

Yet, and in a somewhat contradictory way, I confess my admiration for old solemn university buildings, higher education buildings that are often over a hundred years old. By building the Library of the University of Luxembourg – the Luxembourg Learning Centre – we tried to recover some of the aura of the old libraries. We wanted to create a space that would be both a place for the transmission of knowledge and a meeting place, with a unique and grandiose architecture...“

François Valentiny

Guided Tour

Station 13 - Urban Planning &

„Art in public spaces, as we know it today, is a fairly recent invention.

From antiquity to the beginning of the twentieth century, obelisks, statues and monuments served as symbols of glory, power and memory. As urban determinants, they were used as strategic and orientation points in the development of cities.

In the architecture of antiquity, the great religious buildings, temples and public constructions, such as baths, often bore ornaments, sculptures, mosaics, which had a story to tell: famous passages from the Holy Scriptures or indications of the origins of the city, a place or even a cult. Very few people knew how to read and write, and the narration offered by these ornaments was also intended to keep religious stories alive, as well as to arouse fear and respect among believers and followers.

During the nineteenth century, and more specifically during the period of German Romanticism, urban planners began to decorate towns or the surroundings of villages with monuments that had a landmark function, be it towers, war memorials or even churches. Hills or valleys thereby took on a whole new meaning. There was a real enhancement of the ruins, preferably of ancient churches or temples, whose symbolism in the landscape can be understood as a specificity of this period. It brings to mind the paintings of artists such as Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), whose influence can be seen in a number of my projects, from the design of our offices to the towers I mentioned earlier.

Then, English Landscape Gardens came into being in the eighteenth century: a landscape garden whose shape and style developed back then in England as a deliberate contrast to the French Baroque garden, which previously dominated and forced nature to adopt geometrically perfect forms. English Landscape Gardens were to reflect the principle of a natural landscape, whose purpose was to delight the eye of the beholder by its resemblance to the painting of an ideal, harmonious landscape. ancient temples, then Chinese pagodas, artificial ruins, towers or caves were often added to the landscape in order to accentuate the horizon.

Today, art has changed: it has become less elitist, it has opened up to the general public. In turn, abstract objects, sculptures, monuments and ornaments installed in public spaces replace the urbanistic references that are missing from the landscape of a city.

Modern cities have fewer landmarks, or at least they are more dispersed, less central, since they are increasingly crossed by major roads and bordered by massive constructions.

The evolution of art has meant that, today, more attention is paid to the work itself, to its skilful completion, to its message, and even to the artist. Its functionality in space is fading away. ”

Francois Valentiny

Art in Public Spaces

Guided Tour Station 14

„Administration buildings work like a village, community or small town, but on a lesser scale. Depending on the facility you want to set up, you develop a system of its own. There is no clear line to follow, no universal rules: it all depends on the nature of the activity and the forms of work that will be offered. This does not mean that the future does not hold any conventional or shared offices; however, they will be very different according to the given needs. As regards to the architecture of administrative buildings, such as in the field of housing, there are great variations between the projects that a firm like ours has, over the course of its lifetime, designed and carried out.

Today‘s offices combine a multitude of functions, reflecting a range of skills that employees must master. In order to meet the specific requirements of office work, it is first of all necessary to consider the large number of forms available, from the most traditional to the most advanced: individual offices, in other words small interchangeable squares, or combined offices, which can accommodate a certain number of people and can be modulated to a certain extent, can be built. Then, there is the possibility of building large open spaces, like in the American movies of the 1950s.

The landscape, or even the administrative district in which the building is to be built, are important parameters to be taken into account. They will influence the way external spaces, such as green spaces and plantings, will be developed.

I would like to mention the KPMG building in Kirchberg, where we decided not to set up individual offices, but to propose a more broken-down form. The open spaces can be divided into areas as required, as individual offices can be set up within the overall building module. We have thus created a flexible and completely modular space, in case the building is ever used for other functions in the future.

Such a module often ends up defining the entire design of a building, right down to its exterior appearance. Even if one always remains bound to given dimensions of height, depth and width with regard to volumes, it is possible to play with perimeter measurements to move walls, or to work with the module to gain flexibility.

The KPMG building’s façade is covered with a pattern of steel slats, like a kind of skin. As a result, even though it is one of the smallest buildings in this business district, it draws attention to itself. By installing those slats, we have created a building that stands out strongly in its image. The separation between exterior and interior allowed us to provide an aesthetic value, thanks to the repetitive rhythm of this skin, behind which lies a curtain wall.

Clad with organic-looking steel slats, the Bijou building at the Cloche d’Or was given similar consideration. The slats almost completely cover the façade, whose module is no longer visible. This design was the result of a long process where the climate and the inclination of the light had to be taken into account, all of which had to be high-quality and accurate work...“

François Valentiny

Offices and Workspaces

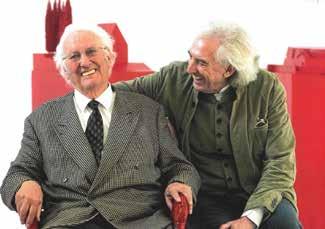

Rob Krier & Roswitha Grützke

Station B

Since 2018, the foundation has housed part of the estate of architect, urban planner, and sculptor Rob Krier, who passed away in 2024, as well as that of his life partner Roswitha Grützke, as a permanent loan. The exhibition of woven images (Grützke) and sculptures (Krier) occupies a large portion of the renovated upper floor of the existing building and is open to the public free of charge during the foundation‘s opening hours.

Rob Krier was born in 1938 in Grevenmacher on the Moselle in Luxembourg. From 1959 to 1964, he studied architecture at the Technische Universität München. As early as 1960, he took part in Oskar Kokoschka’s Schule des Sehens – the International Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Salzburg.

After completing his studies, he initially worked from 1965 to 1966 on a freelance contract with Oswald Mathias Ungers in Cologne and Berlin. This was followed by another freelance engagement from 1966 to 1970 with Frei Otto in Berlin and Stuttgart. Between 1973 and 1975, he held teaching positions in Stuttgart and Lausanne.

From 1976 to 1998, Rob Krier was a professor at the Faculty of Architecture and Spatial Planning at the Technische Universität Wien. In 1986, he also served as a visiting professor at Yale University in New Haven, USA. In recognition of his achievements, he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Stockholm in 1992. In 1996, he was named an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA).

Rob Krier passed away in 2024.

Roswitha Grützke was born in 1938 in Berlin. From 1958 to 1962, she studied at the Meisterschule für Kunsthandwerk Berlin, now the Universität der Künste. There, she received a solid craft-based education in weaving, along with instruction in design, drawing, and painting. She then worked in various weaving studios in Germany and Austria until 1967. In 1968, she passed the master craftsman examination in hand weaving.

In 1969, she participated in the 4th Internationale Tapisserienausstellung in Lausanne with one of her works. From 1972 to 2000, she taught art education at the Loschmidt vocational school in Berlin-Charlottenburg. In parallel, she held a teaching position from 1976 to 1997 at the Hochschule der Künste Berlin (now Universität der Künste), in the departments of textile design and art education.

Artistically, Roswitha Grützke came into the public eye in 1981 with an exhibition at Galerie in der Koppel 66 in Hamburg. In 1983, her work was shown at the Berliner Festspielgalerie, featuring Gobelins created in collaboration with the painter Johannes Grützke. In 1992, she took part in the International Tapestry Network Exhibition II at the Textile Museum in Washington, USA.

„Ein Telefonat zwischen Berlin und Remerschen.

Anna Valentiny im Gespräch mit Roswitha Grützke und Rob Krier anlässlich ihrer Dauerleihgaben an die Valentiny Foundation in Jahr 2018.“

Collection

Station C

Valentiny-Burggraff

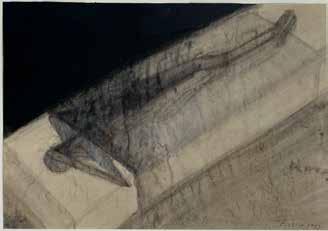

200 Jahre Revolution (Die Französische Revolution), 1989 drypoint etching

16,8 x 31 cm

Alfred Hrdlicka (1928–2009) was an Austrian sculptor, painter, draftsman, and art professor. He studied painting under Robin Christian Andersen and Josef Dobrowsky, as well as sculpture under Fritz Wotruba at the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien. In 1964, he represented Austria at the Venice Biennale. Hrdlicka’s work is marked by political intensity and often provocative figuration. Starting in 1963, he led the sculpture class at the Internationale Sommerakademie Salzburg. He held professorships in Stuttgart, Hamburg, Berlin, and from 1989 at the Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien.

Among his most well-known works are the Mahnmal gegen Krieg und Faschismus at Albertinaplatz in Vienna, the FriedrichEngels-Denkmal in Wuppertal, the Gegendenkmal für die Opfer der Gestapo in Hamburg, and the monumental cycle of figures for the Passionsspiele in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna.

Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn

Gustav Peichl (1928–2019) was an influential Austrian architect, university professor, and political cartoonist (under the pseudonym Ironimus). He studied under Clemens Holzmeister at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste Wien. In the 1960s and 1970s, he designed the distinctive ORF regional broadcasting studios throughout Austria – popularly known as the Peichl-Torte – as well as the AUVA Rehabilitation Center Meidling (1966–68).

In Germany, his major projects included the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn (1985–92) and the extension of the Städel Museum in Frankfurt (1987–91). From 1973 to 1996, he led the master class in architecture at the MAK in Vienna. Alongside his architectural work, he regularly published political cartoons in major daily newspapers.

Clemens Holzmeister (1886–1983) is considered one of the most important and internationally renowned Austrian architects of the 20th century. With his redesigns of the Salzburg Festival Hall in 1926 and 1936, as well as the construction of the Großes Festspielhaus (New Festival Hall) in 1960, he left a lasting mark on the architecture of the Salzburg Festival.

For decades, he was also a highly influential teacher –including at the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien (1924–1938) and in Turkey – shaping an entire generation of architects. Among his students was Wilhelm Holzbauer. In Turkey, he was commissioned by Atatürk to design key government buildings, including the national parliament building.

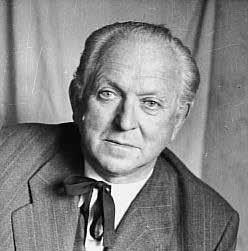

Wilhelm Holzbauer (1930–2019) was one of the leading proponents of „pragmatic modernism“ in Austria. He studied under Clemens Holzmeister at the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien and later at MIT in Boston. As a professor at the Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien, he shaped multiple generations of architects.

Among his most important buildings are the Rathaus Linz, the Landhaus Bregenz, the Terminal Tower Linz, Tech Gate Vienna, and the opera house in Amsterdam (Stopera, 1986), a multifunctional complex for music theatre and municipal administration, realized in collaboration with Cees Dam. Continuing the legacy of his teacher, Holzbauer—together with François Valentiny—designed the Haus für Mozart in 2006, a high-quality, technically modern renovation created to mark Mozart’s 250th birthday.

Salzburg

The City Hall of Amsterdam

"Einen verteufelt guten und phantasievollen Dichter“ nannte Friedrich Achleitner seinen Freund und Architektenkollegen anlässlich der Rückgabe der Briefe, die ihm Wilhelm Holzbauer zwischen 1956 und 1959 aus Amerika geschickt hatte. Daraus entstand der entdeckenswerte Band "meiself in bosdn". Beide –Sender und Empfänger – sind 2019 gestorben.

Aus Anlass seines 90. Geburtstags würdigt die Publikation "Holzbauer" nun das schriftstellerische Erbe eines der Großen der österreichischen Nachkriegsarchitektur, dessen bauliche Hinterlassenschaften bereits mehrere Bücher füllen.

Ein Leben lang trieb den Vielbauer, der zugleich ein umfassend gebildeter und belesener Mensch war, das Schreiben um; mit Tiefgang, Verve und Witz ging er es an.

Aus einem großen Konvolut haben die Herausgeber ihre Auswahl getroffen: Autobiografisches, Essays zu seinen eigenen Bauten, Aufsätze und Texte zur Architektur ganz allgemein, begleitet von (persönlichen) Fotografien und Skizzen. „

Dimitris Manikas & Markus Kristan, (Hrsg)

Holzbauer

Seiten: 425

Format: 115x180mm

ISBN 978-2-9199670-4-9

Max Pechstein (1881–1955) was a leading German Expressionist and a member of the artist group Brücke. He studied in Dresden and developed a vivid, expressive visual language characterized by bold outlines and flat areas of intense color. Among his most well-known works are Liegende im roten Raum (1910), Junge mit Fisch (1914), and Dorfstraße in Nidden (1921). His 1914 journey to Palau in the South Seas had a profound impact on his choice of subjects and motifs.

After 1933, he was denounced by the National Socialists as “degenerate,” lost his professorship, and was banned from exhibiting his work. After the war, he resumed his role as a professor in Berlin and was a co-founder of the Berliner Neue Gruppe.

Walter Pichler (1936–2012) was an Austrian sculptor, draftsman, and visionary architect. After studying at the Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien, he gained recognition in the 1960s for his radical spatial and architectural concepts, such as the Prototypes (1967) – visionary objects that blur the boundaries between sculpture, device, and inhabitable space.

Among his major works are Tragbare Architektur, TV-Helm, and the monumental chapel structures he built on his farm in St. Martin in Burgenland. Pichler exhibited internationally, including at documenta 4 (1968) in Kassel. His work combines a critique of technology and civilization with a language of archaic forms.

Prozession, 1924–1924 brush and ink 45 x 59.5 cm

Gottfried Salzmann (born 1943 in Saalfelden) is an Austrian painter who has gained international recognition, particularly for his watercolors. Since 1965, he has lived and worked in Paris and Vence. His major works feature striking urban landscapes, including the widely acclaimed watercolors New York, 42nd Street (2020), New York – Times Square from Above (2014), and Krimml (2022), as well as large-format scenes such as Dunkle Dächer in der Champagne (ca. 1970).

Characteristic of his style are fluid perspectives, transparent layers of color, and formal reduction, combining technical mastery with atmospheric depth. His works blend realistic painting with experimental techniques such as collage, photography, and overpainting.

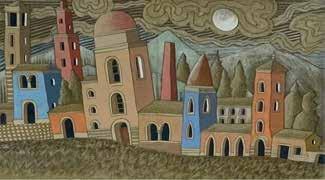

Lucien Steil (born 1956 in Luxembourg) is an architect, educator, and author known for his advocacy of classical and traditional architecture in contemporary urban design. He studied at the École Spéciale d’Architecture in Paris and has taught at institutions such as the University of Miami and the University of Notre Dame.

His work focuses on urban morphology, architectural drawing, and the integration of craft and theory. As editor and writer, he has contributed to architectural discourse through publications like The Architectural Capriccio and the INTBAU Journal, promoting sustainable urbanism and architectural heritage.

L‘ombre - Porte Saint Denise, 2020 watercolor, pastel on paper 51 x 65 cm

End of the Summer, Capriccio in Ink, Guache and Pastel on Kraft paper, 2016

Josef Zenzmaier (1933–2023) was an Austrian sculptor and bronze caster, renowned especially for his public works. After completing an apprenticeship as a stonemason, he studied at the Internationale Sommerakademie Salzburg under Oskar Kokoschka and later worked with Giacomo Manzù and Emilio Greco in Italy. In 1967, he established his own bronze foundry in Kuchl and went on to lead the bronze casting class at the Summer Academy.

His body of work includes numerous monuments, fountains, and sacred objects. Among his most notable pieces are the Denkmal für Erwin Ringel in Vienna, the Marktbrunnen in Kuchl, and three large-scale bronze reliefs above the entrance portals of the Haus für Mozart in Salzburg (2006), which lend a distinctive artistic character to the Festival Hall.

Ensemble „Accord de Schengen“

Excursion 1

Living in the Commune of Schengen Excursion 3

1 Ruppert single-family house (1984–1985)

2 Conversion of a grocery store

1 Ruppert single-family house (1984–1985)

3 and construction of an apartment and a single-family house for the family Wagener (2010–2012)

2 Conversion of a grocery store

4 Winter garden for a single-family house, family Wagener (2011–2012)

3 and construction of an apartment and a single-family house for the family Wagener (2010–2012)

5 Residence for the elderly Les Jardins de Schengen (2007–2015)

4 Winter garden for a single-family house, family Wagener (2011–2012)

5 Residence for the elderly Les Jardins de Schengen (2007–2015)

6 Four terraced houses, Op der Wollefskaul (2010–2012) 7 Conversion of the Wilzius house (2009-2010)

6 Four terraced houses, Op der Wollefskaul (2010–2012) 7 Conversion of the Wilzius house (2009–2010)

Pretemer single-family house (2010–2011)

Pretemer single-family house (2010–2011)

Conversion of the Kayser house (2009–2011)

Conversion of the Kayser house (2009–2011)

(2011–2015)

17 Single-family house Muller (1984–1985)

18 Conversion of a winegrower‘s house and dwellings Dentzscheseck (2013–2020)

WINTRANGE / SCHWEBSANGE

17 Single-family house Muller (1984–1985)

18 Conversion of a winegrower‘s house and dwellings Dentzscheseck (2013–2020)

19 Conversion and extension of the D’Haeseleer house (2014–2018)

20 Single-family house Obertin-Marx (2013–2015)

21 Hirtt house

22 Reuter house

23 Conversion of an old winegrower‘s house - Schram (2012)

24 Conversion of the Jankowitz building into a residential and office building (2004–2007)

WELLENSTEIN / BECH-KLEINMACHER

19 Conversion and extension of the D’Haeseleer house (2014–2018)

20 Single-family house Obertin-Marx (2013–2015)

21 Hirtt house

22 Reuter house

23 Conversion of an old winegrower‘s house - Schram (2012)

24 Conversion of the Jankowitz building into a residential and office building (2004–2007)