Not realised projects

Work in progress

United States

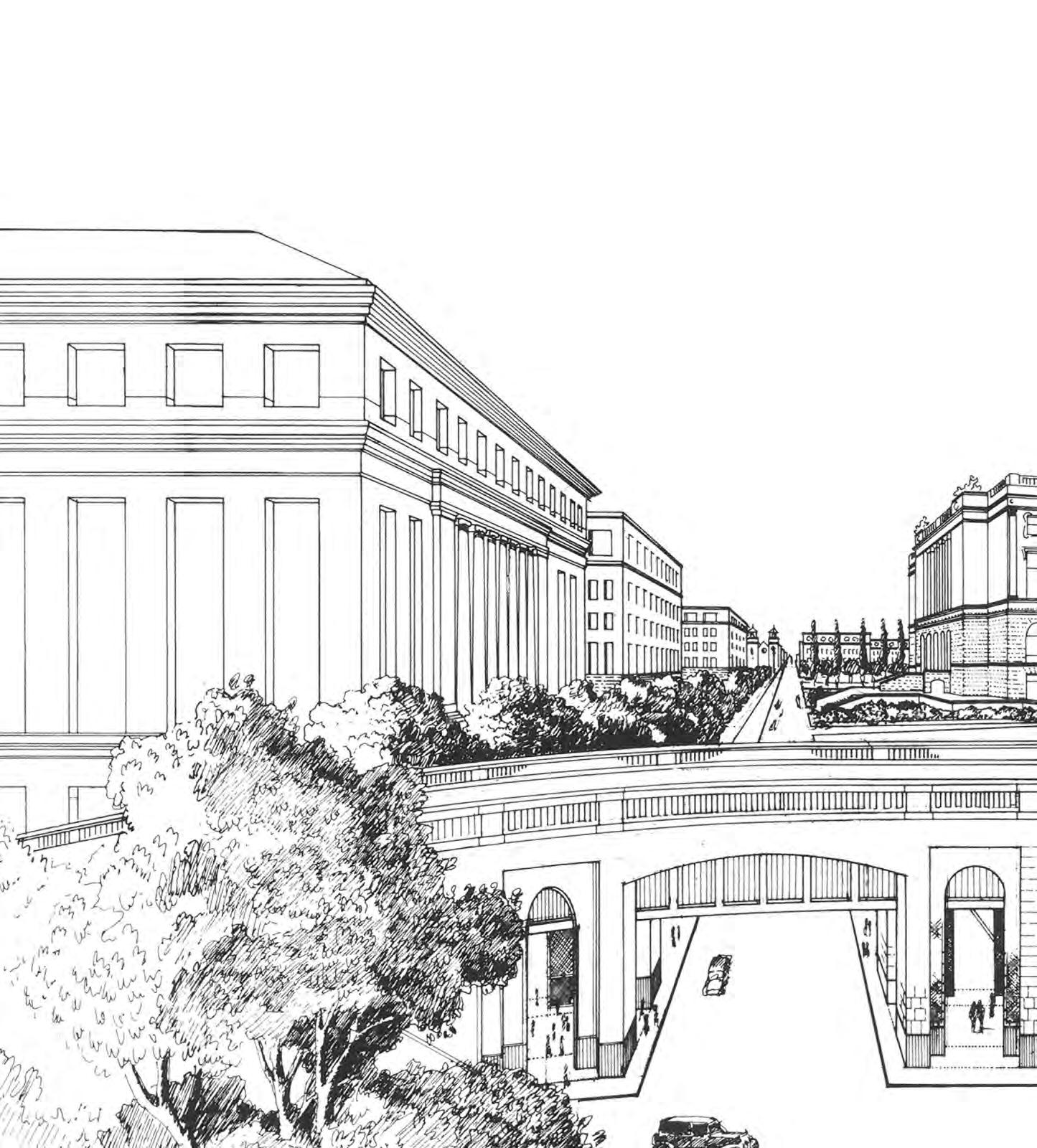

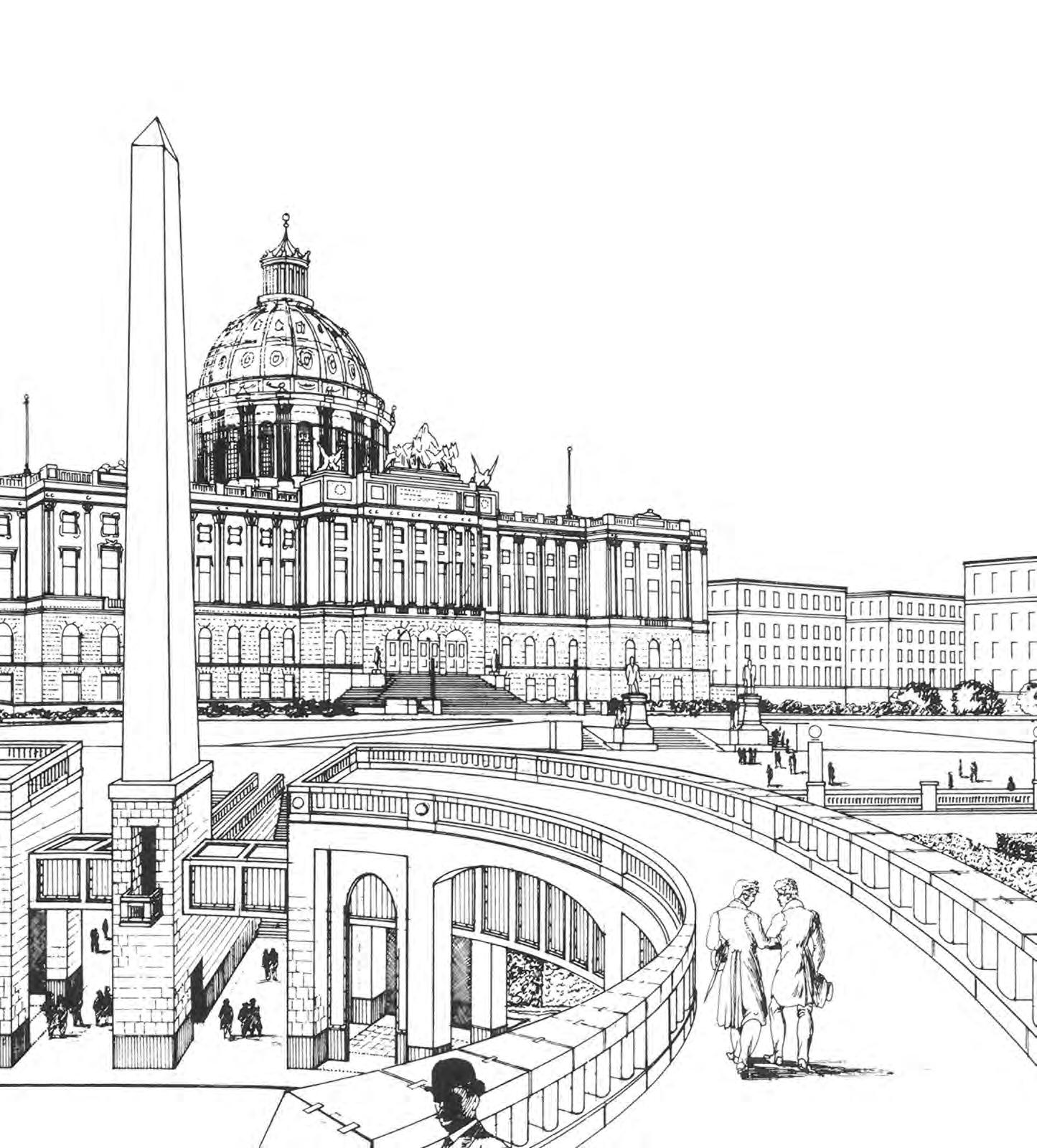

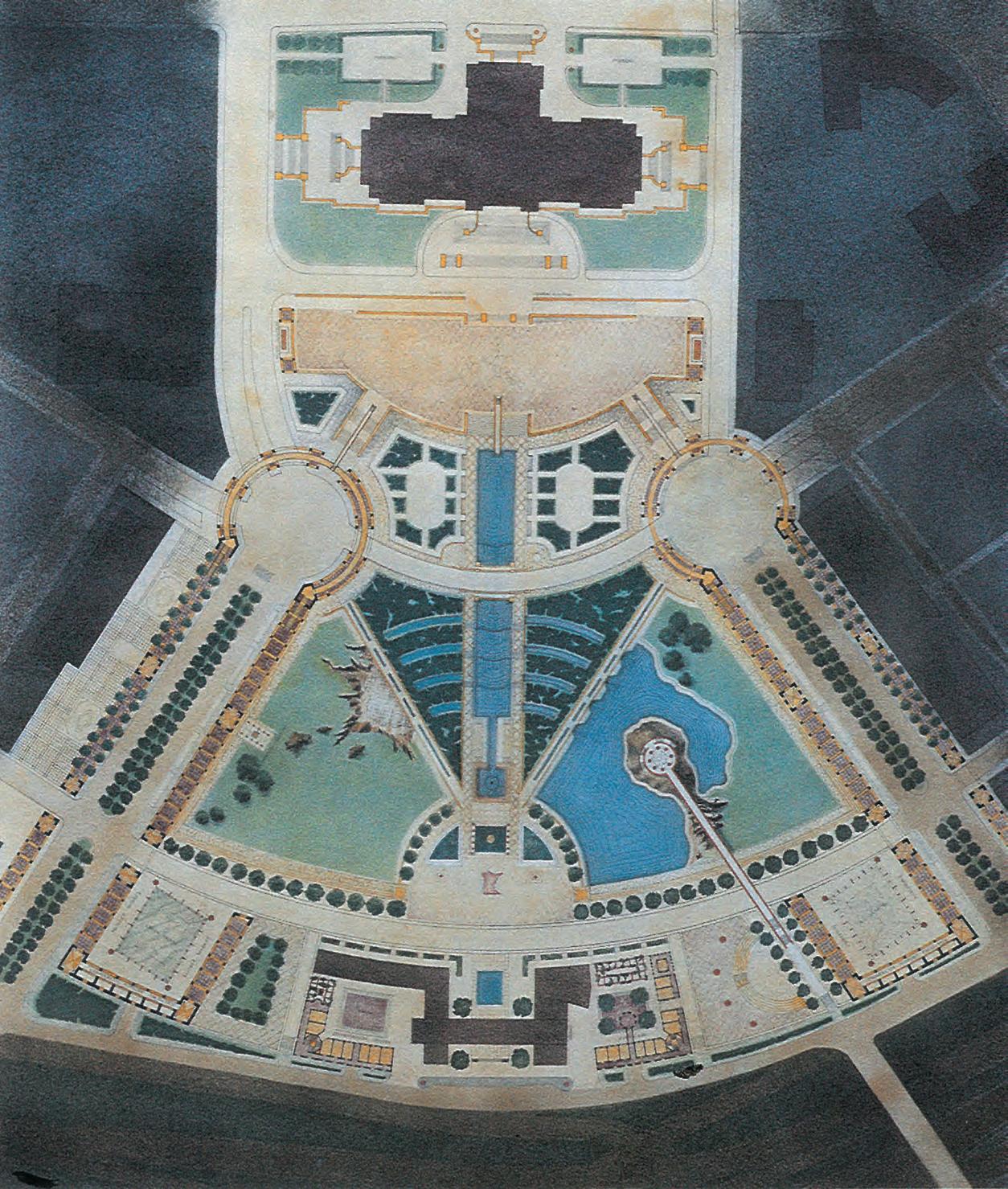

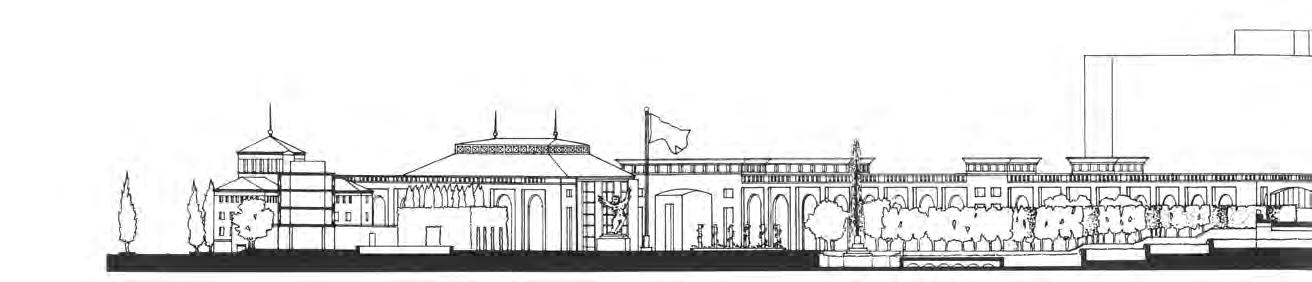

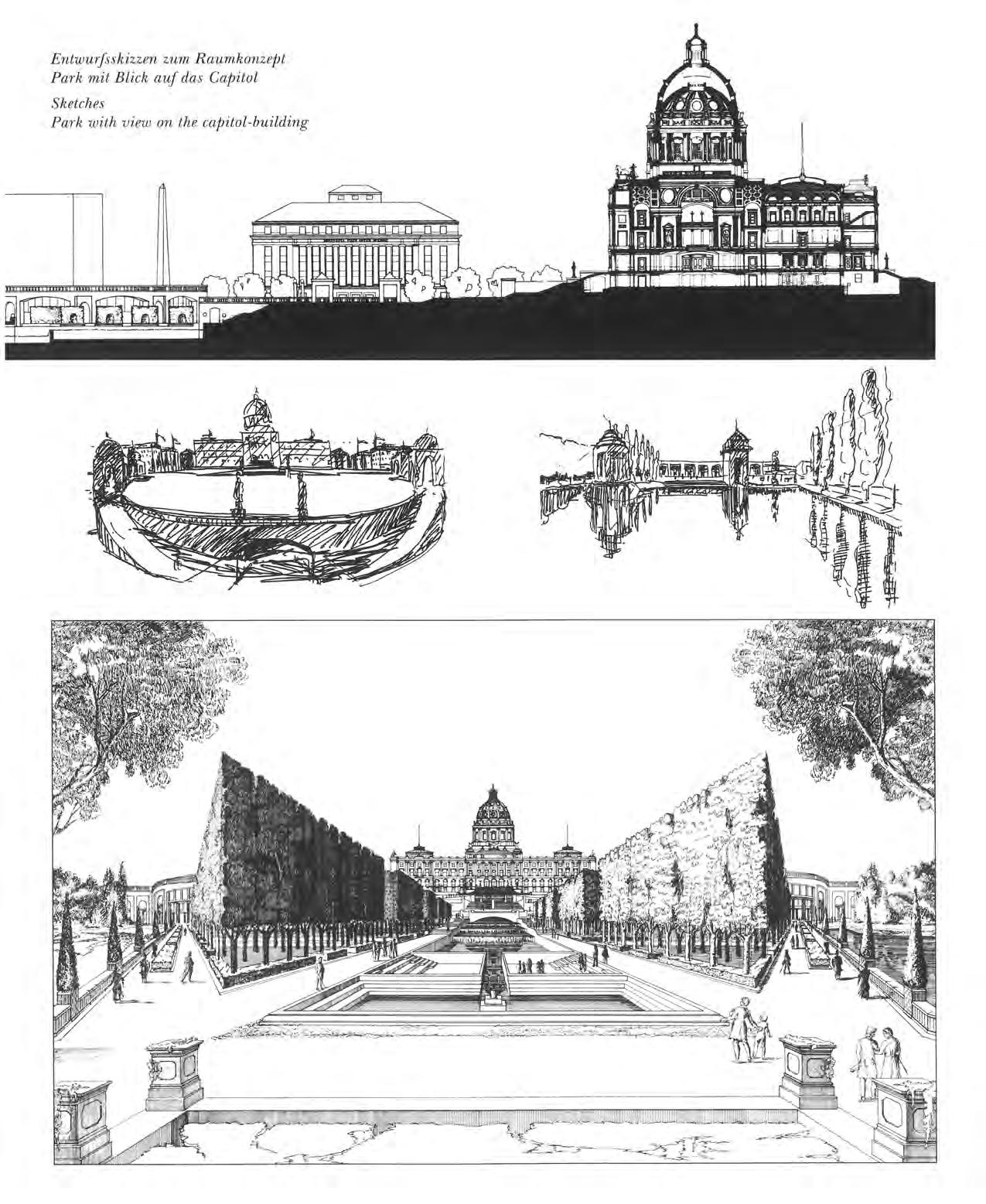

Capitol Area 1986

Germany

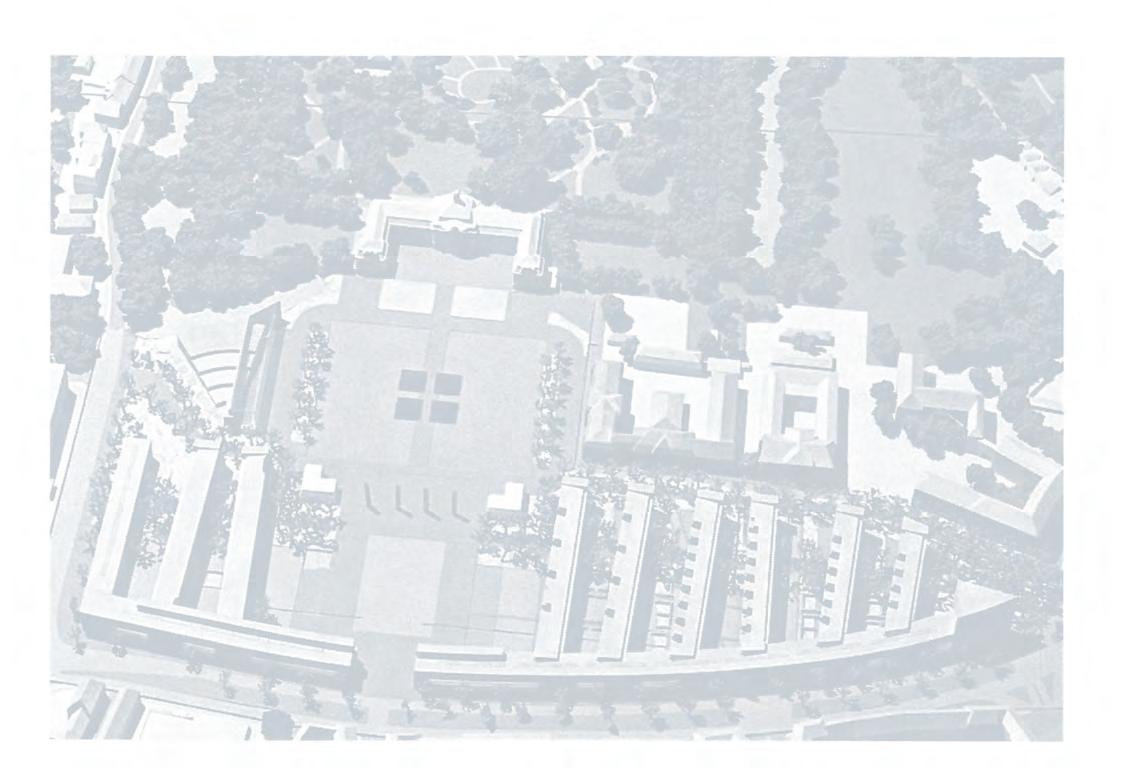

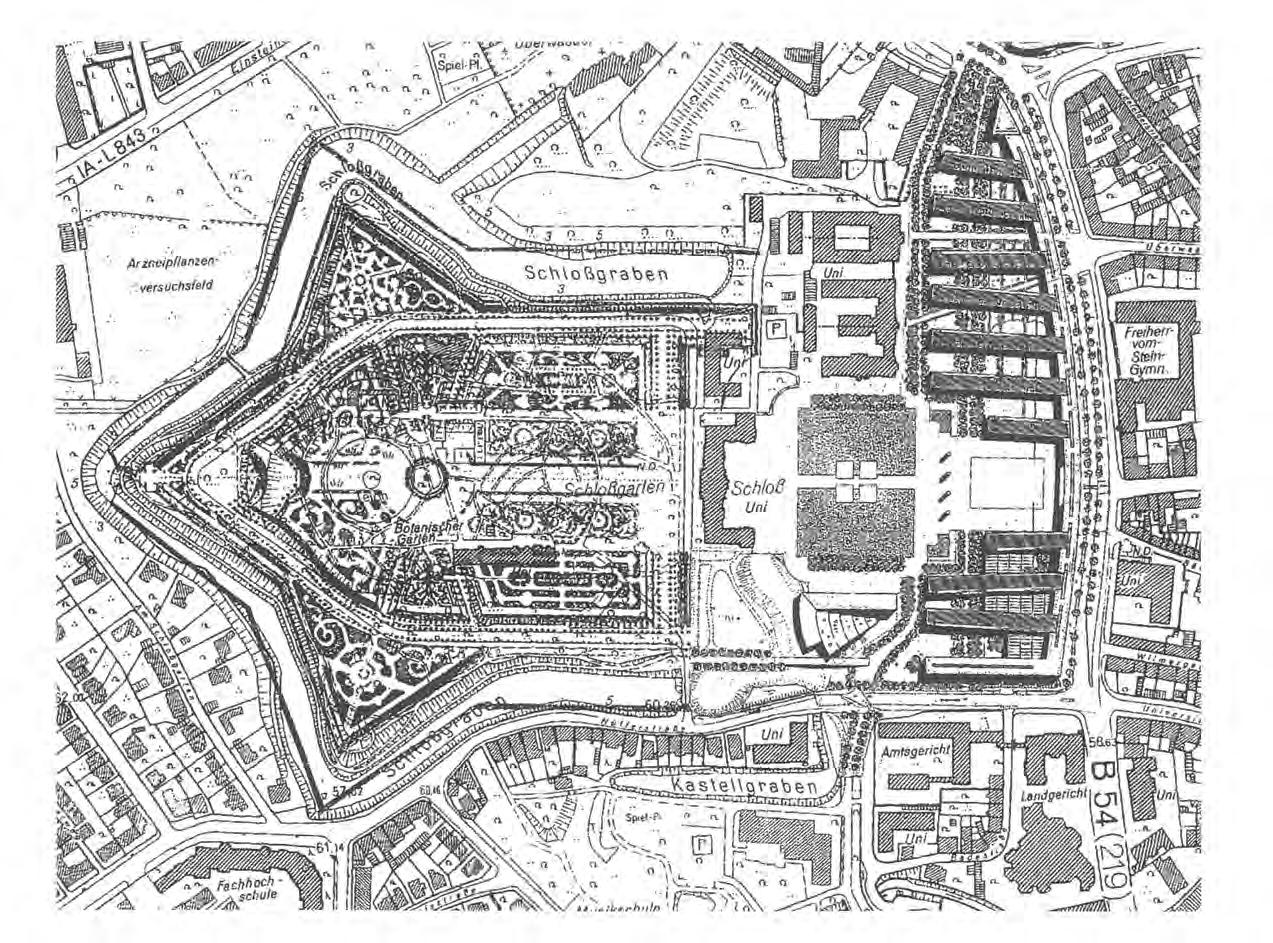

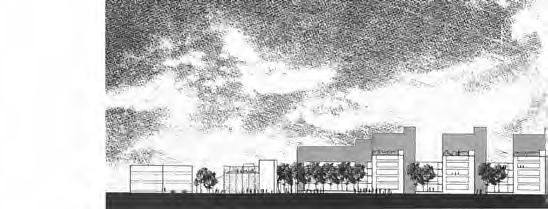

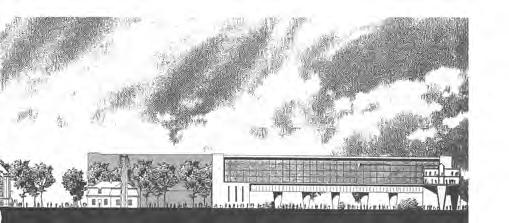

Westend University Campus 2004

Parliamentary and ministerial buildings 1995

Administrative Court 2006

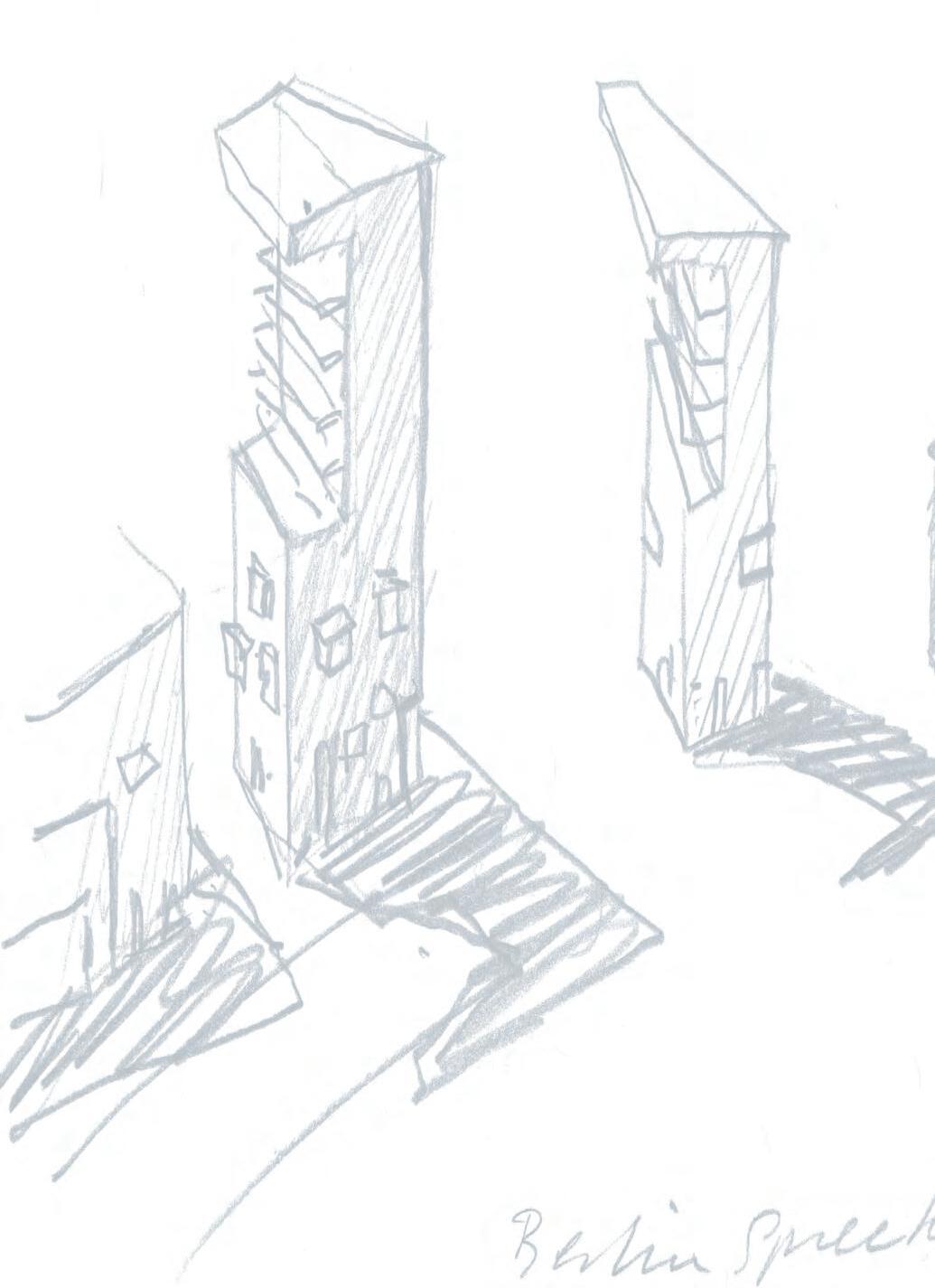

Government District Berlin Capital Spreebogen 1992

Hotel and service complex 1993–1995

Hindenburgplatz subdivision 1993

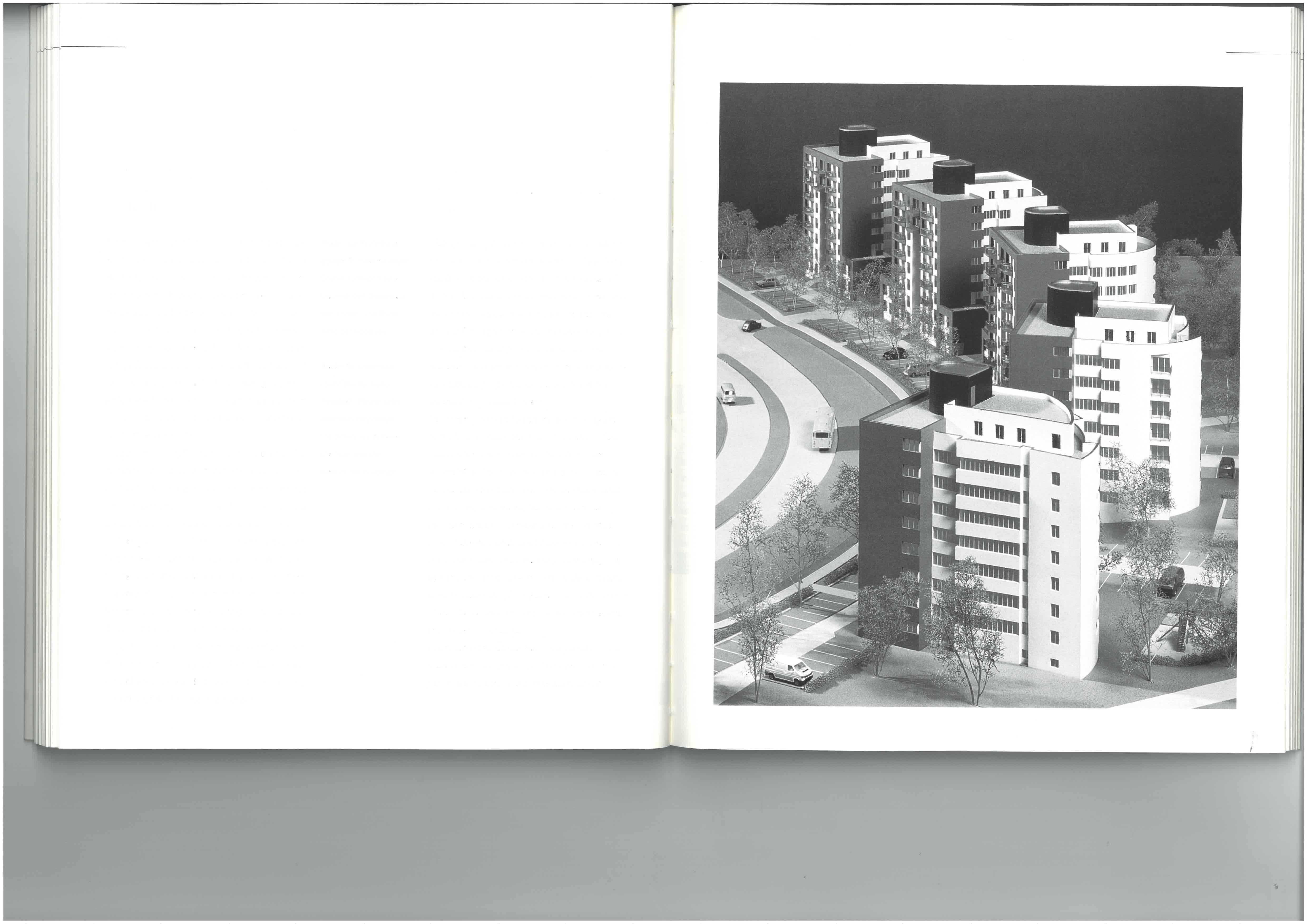

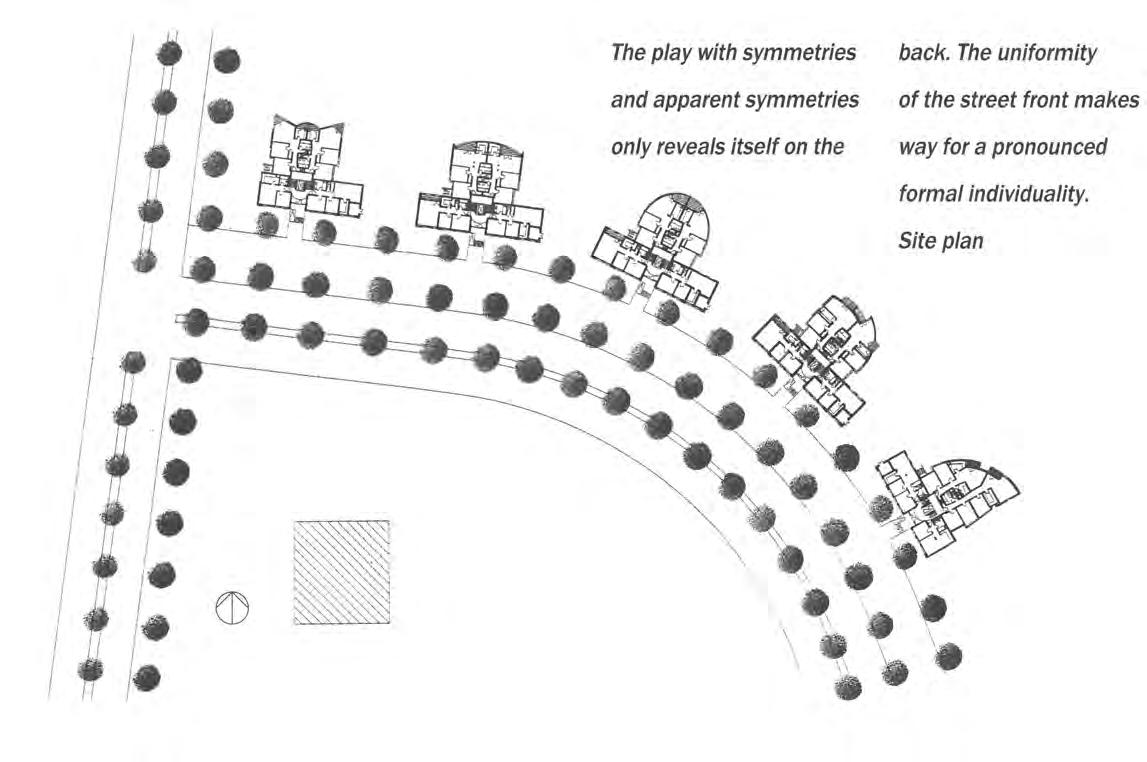

Five residential buildings 1993–1995

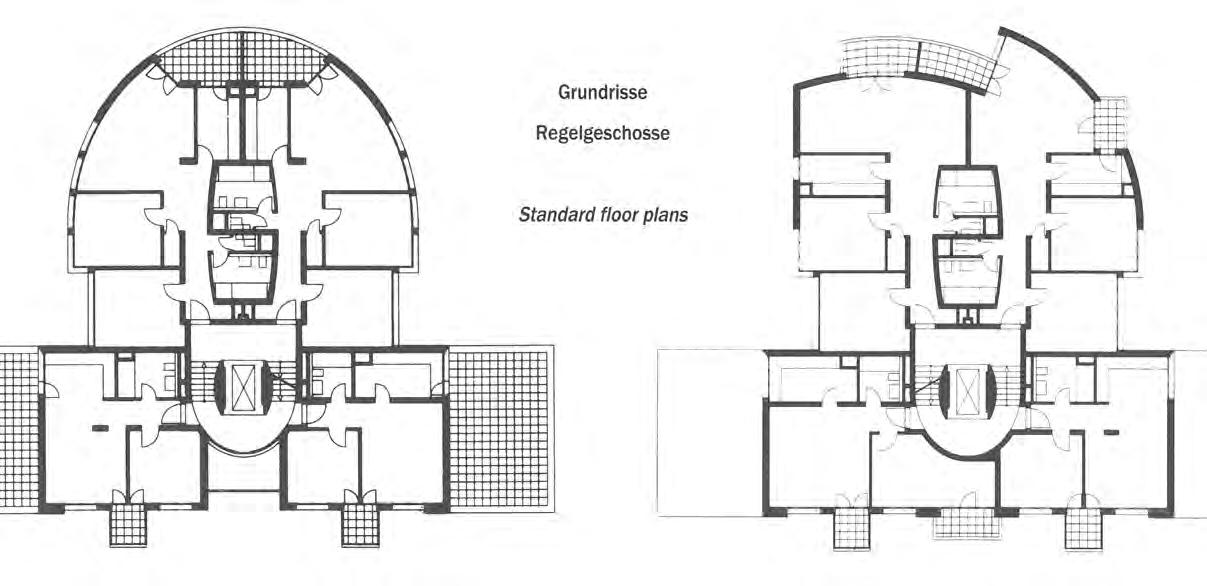

Neighbourhood centre

– shopping centre and cinema 1997–1999

Luxembourg

Conversion and extension of the Lycée classique 1993–2005

Sports hall for the Lycée classique 1993–1998

Children’s day care centre Stärenhaus 1995–1998

Extension and transformation of the primary and secondary Schools 2001–2003

Sports hall and classrooms for a primary school 2017–2020

Preschool and primary school 2002–2005

Cité des Sciences Education Building, 2nd prize 2006

University Library Luxembourg Learning Centre 2008–2018

Town Hall 1993–1996

Conversion and construction of an additional floor for the town hall 1998–1999

Construction of a multipurpose hall in the church and outdoor facilities 2011–2012

Conversion of the Koch’haus 2012–2014

Fire station 1986–1988

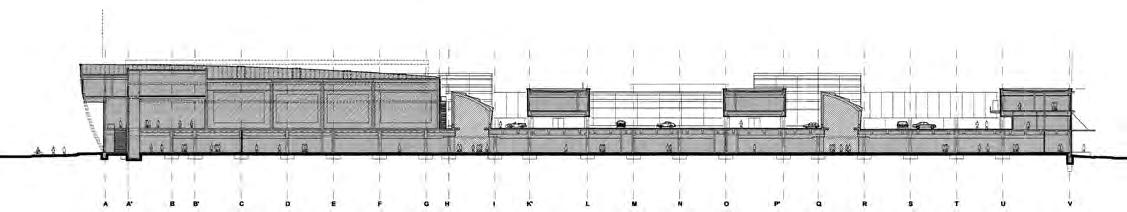

Customs facility on the Luxembourg-Trier motorway 1984–1987

DG Bank 1989–1990

Commerzbank administration building 2000–2003

Mother-Child Centre for the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg 2003–2015

Nursery for the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg 2009–2013

Administrative building for Ciments S.A. 1998–2000

BCEE bank building 2007–2008

Administration building for KPMG 2010–2015

Entrance building of the Rotarex Group 2011–

Office building Mediabay The Waves 2014–

Switzerland

Roche administration tower 2008

Office building B2-01 - Le Bijou 2015–2020

New headquarters of the Luxembourg Post 2017

BASEP multi-purpose complex 2018

Office building –The Flower Building 2019–

Office building –Lot E04-E10 2020–

New carpentry workshops Annen SA 2013–

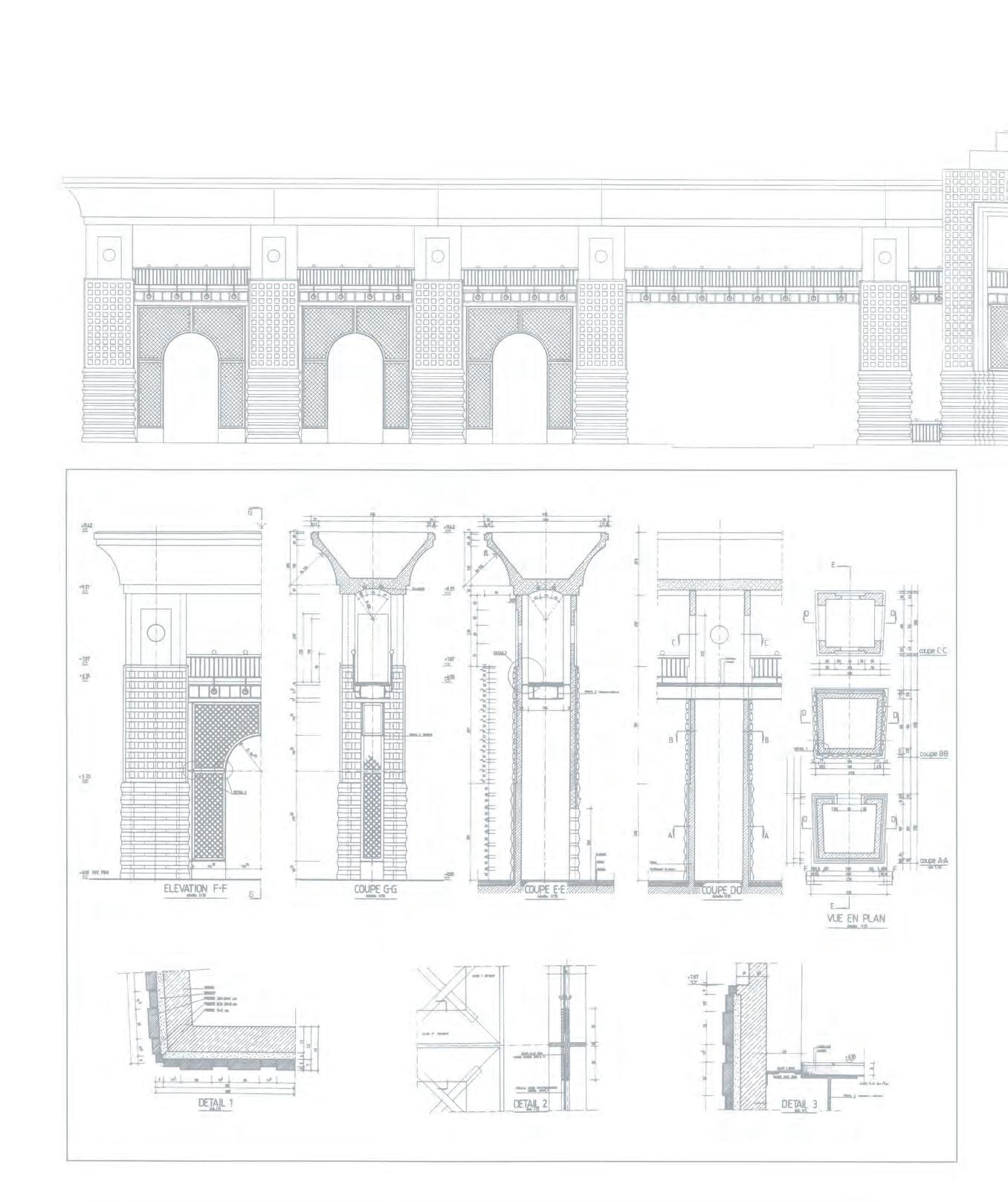

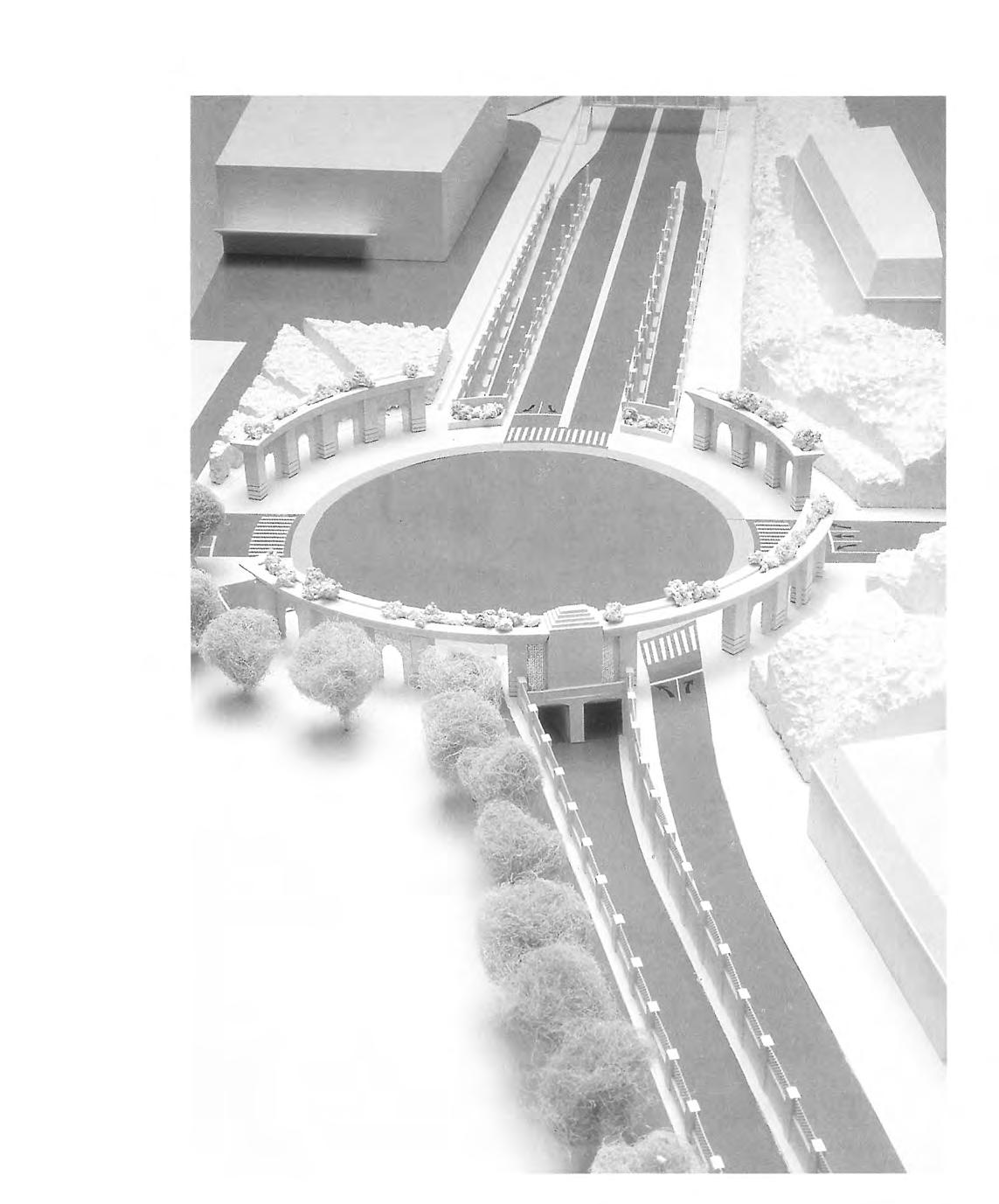

Schumann Roundabout 1981–1982

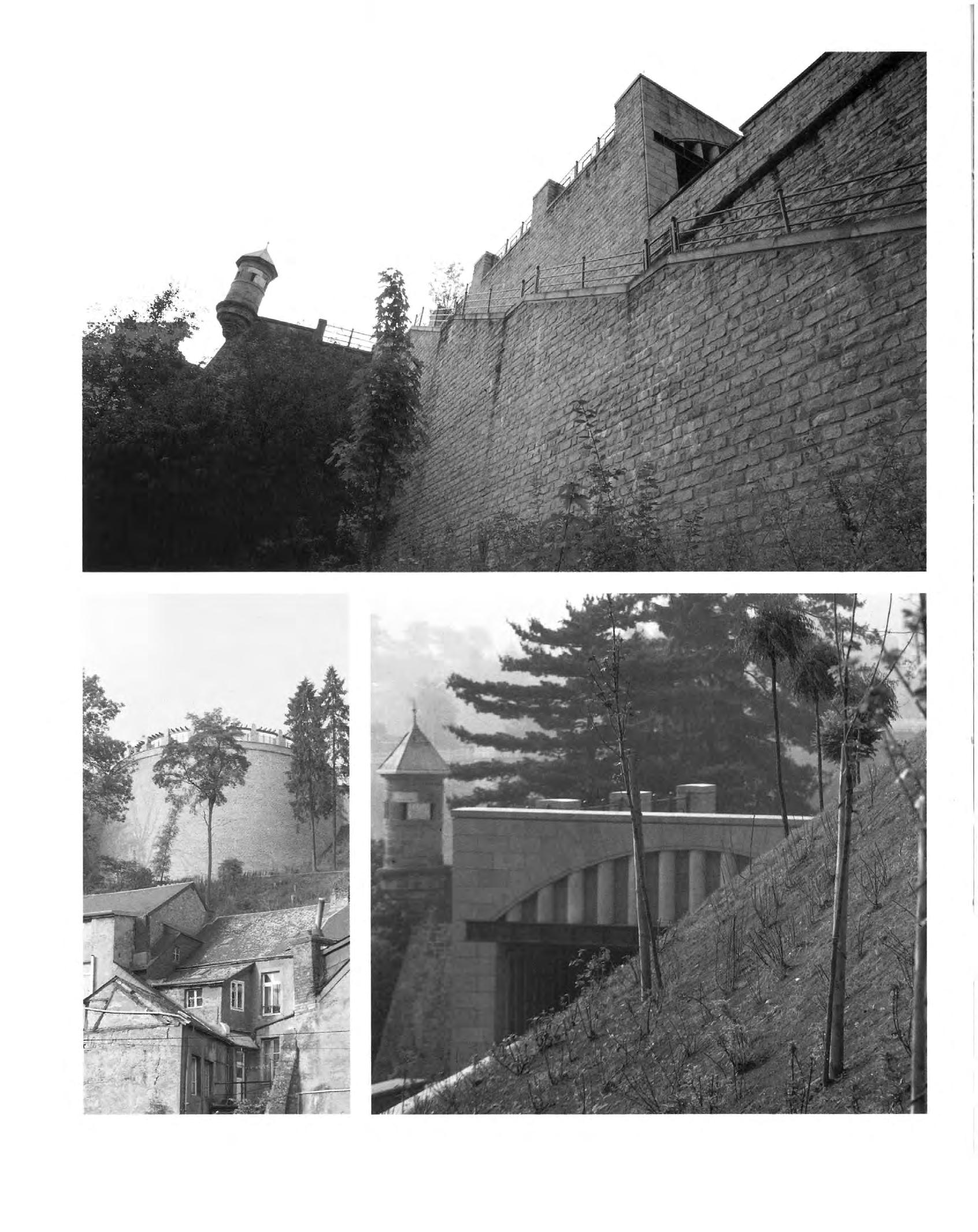

Tunnel du Saint Esprit 1984–1986

Extension of the KonradAdenauer building for the European Parliament 2003

Austria

School Centre 1984

Schweglerstrasse Comprehensive School 1991–1994

New building for the Danube Private University 2013–2018

Halls of residence for students and professors of the DPU Danube Private University 2017–

Embassy of Luxembourg 1993–1995

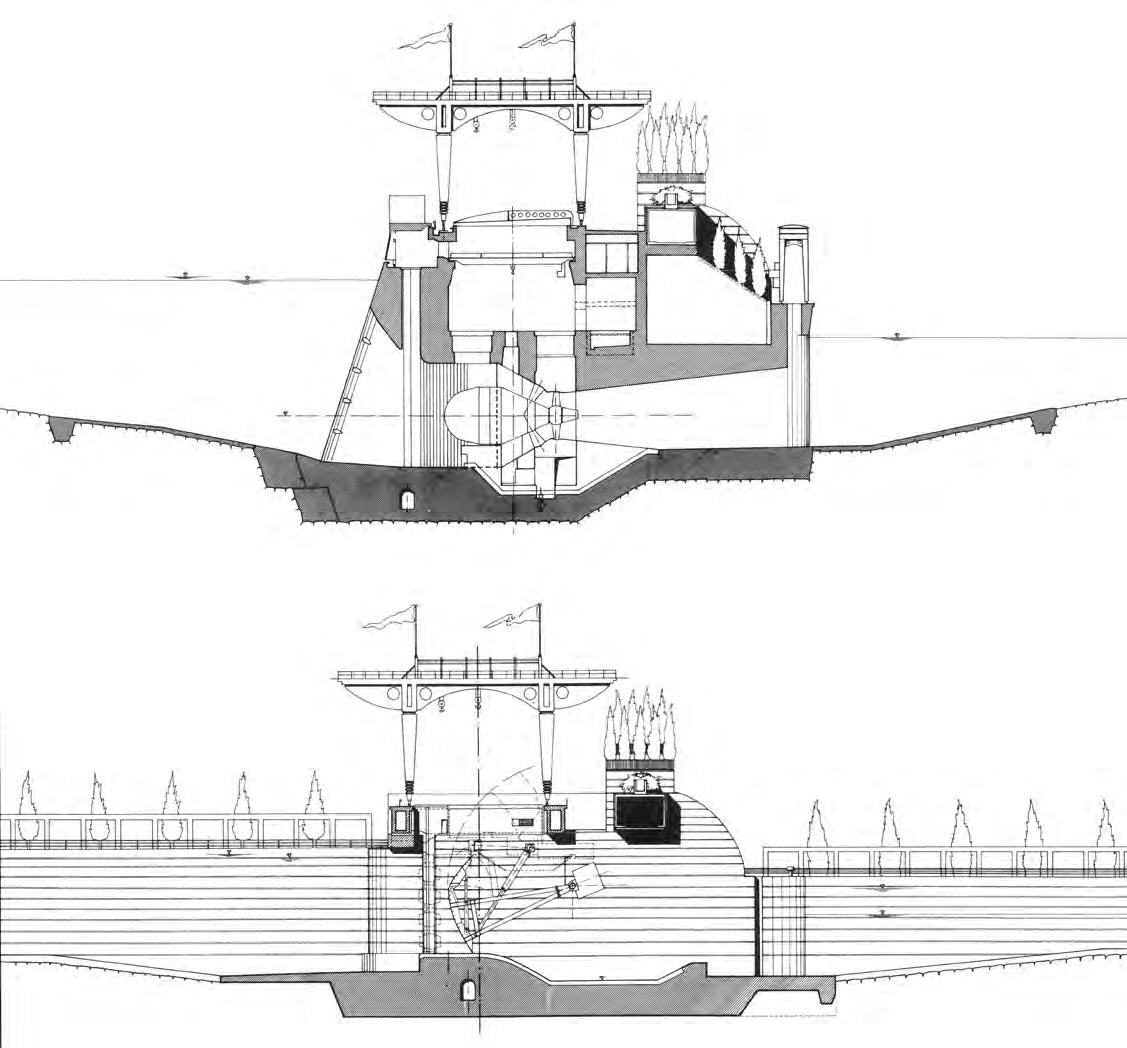

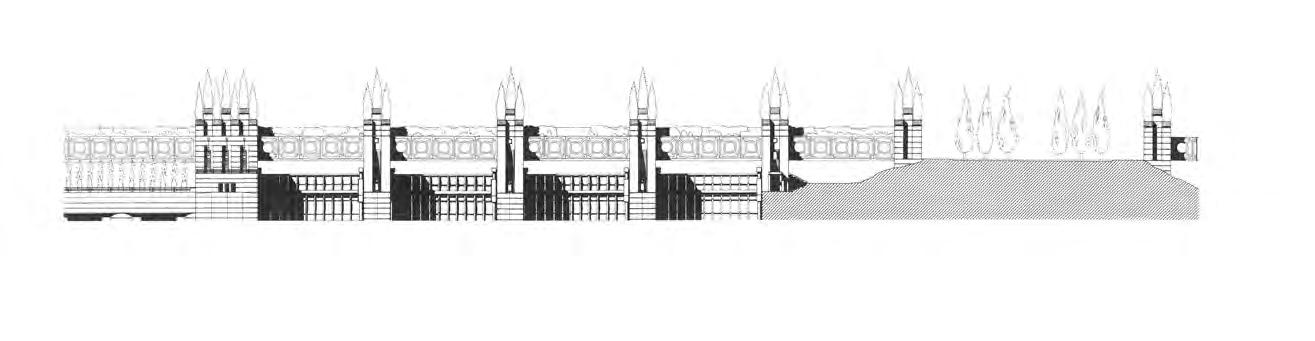

The Danube Barrage 1987

China

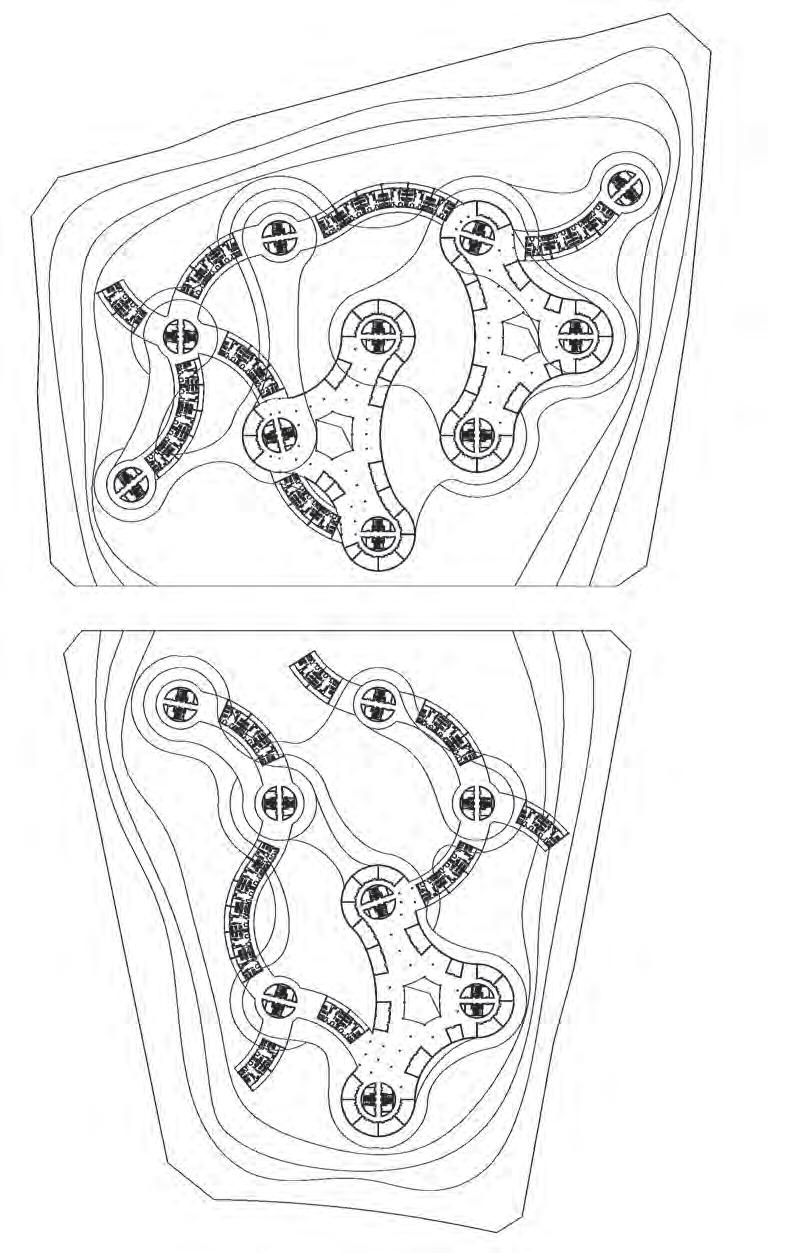

Campus planning of Yangtze River Art Engineering Vocational School 2018

Campus for an art university Campus pour une université d’art 2018

Shahe residential area building and landscape design 2018

Low-carbon city 2015

URBANISM URBANISME

Schumann

Thoughts on Urban Architecture (1991)

Gedanken zum Städtebau

Authors: Hubert Hermann and François Valentiny, from: Hubert Hermann; François Valentiny (eds.): Hermann & Valentiny Architects, Stuttgart/Zurich: Krämer Verlag, 1991, 50–62. ISBN 3-7828-1607-2

The type of services that we architects provide for society and the tasks with which society entrusts us, were more or less clearly understood until the 18th century, although the forms, methods of planning, the clients and contractors, and the time and place were different. Up to this time the creativity of the architect had been subject to a universal attitude, which clearly determined the architectural content.

Nowadays, architecture subjugates itself to industrial producibility, which strongly reduces the wealth of architectural modes of

expression. This process is still continuing, traditional trades have practically died out and industry dominates constructed reality.

If the architect was once the executor of a mystical and philosophical dictum, he is now the henchman of a purely materially orientated production machine.

Thus urban development now escapes any creative intervention. The chaotic state of affairs which arose in the Sixties and Seventies because of the failure to pursue planned visions and to create urban priority systems, has bankrupted our historical cities and turned them into traffic infested cloacas.

This functionalist and exploitative attitude must not form the basis for our approach to our cities.

Cities do not only develop from the functional capacity of their individual elements, since functional aspects are an obvious part of all planning.

Die Art der Dienste, die wir Architekten der Gesellschaft erweisen, und die Aufgabe, mit denen die Gesellschaft uns betraut, sind bis ins 18. Jahrhundert in Europa einigermaßen festgelegt, obwohl die Formen, die Methoden der Planung, der Auftraggeber und die Ausführenden, Zeit und Ort verschieden waren. Bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt ist das Schaffen des Architekten einer universellen Geisteshaltung unterworfen, die die Inhalte der Architektur eindeutig bestimmen.

Heute ordnet sich die Architektur einer industriellen Produzierbarkeit unter, die den Reichtum architektonischer Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten stark reduziert. Dieser Prozess setzt sich fort, das Handwerk ist praktisch ausgestorben und die Industrie dominiert die gebaute Realität.

War der Architekt früher Ausführender eines mystisch-philosophischen Diktats, so ist er jetzt Handlanger einer rein materiell ausgerichteten Produktion.

Dem Städtebau ist so jedes schöpferische Eingreifen entzogen worden. Durch das Versäumnis, geplante Visionen weiterzuführen und übergeordnete Stadtsysteme zu schaffen, wurde in den 60er und 70er Jahren chaotische Zustände heraufbeschworen, die unsere historisch gewachsenen Städte zu verkehrsverseuchten Kloaken abwirtschafteten.

Dieses funktionalistische und ausbeuterische Denken kann nicht Ausgangspunkt für die Stadt sein.

Die Stadt entsteht nicht nur aus der Funktionsfähigkeit ihrer einzelnen Elemente, die funktionalen Aspekte sind selbstverständlicher Teil jeder Planung.

Die Stadt entwickelt sich aus dem kulturellen Prozess ihrer Gesellschaft, deren Ursprünge Anlass zu ihrer Gestalt und Rahmen ihrer Weiterentwicklung sind. Sie ist erklärbar aus dem Ergebnis ästhetischer Ziele, die eine beliebige Stelle zu einem unverwechsel-

This text was originally published in: Thoughts on Urban Architecture

Cities develop from the cultural activities of the society which lives in them, activities whose origins mould it and form the framework for its continued development. Cities can be explained as the result of aesthetic goals, which turn any old spot into an unmistakable location. They can be explained as the result of the decision to give space a form – space that is an expression of a universal vision. The architectural intervention is part of a geographical configuration, which is inextricably linked to the history of the place and to memorable aspects of it.

Cities are not anonymous – they are built and cultivated. Cities are the manifestation of cultural development. They are not only the sum of their individual elements, they are more – they are the Will to Urbanity.

The city is a specific location.

Cities leave their mark on people, they can kill and they can enliven.

As the focus for our needs and longings, the city motivates us to change, to alienate, to play with and exploit it.

It is the result of a spiritual order and conceals within it the necessity to strive against this order.

It is changed and changes us. This assessment of our powers is our whole existence and meaning. Cities imply then the will to a precisely defined concept of the city whereby the degree to which it is habitable is closely related to the strength of its identity. Only when the surroundings are identifiable, can they become familiar in form and symbolism to their inhabitants and thus appear meaningful and comprehensible. A feeling of belonging and being at home arises from the common appreciation of its significance.

baren Platz machen. Sie ist erklärbar aus der Entscheidung, Raum zu formulieren, Raum als Ausdruck einer universellen Vision. Der architektonische Eingriff ist Teil einer geographischen Konfiguration, der unlösbar mit den Werken der Geschichte dieses Ortes und den Erinnerungen an diesen Ort verbunden ist.

Die Stadt ist nicht anonym – sie ist gebaut und gewachsen. Die Stadt ist das Manifest einer kulturellen Entwicklung. Sie ist nicht nur die Summe ihrer einzelnen Elemente, sie ist mehr – sie ist der Wille zur Urbanität. Die Stadt ist Ort.

Die Stadt prägt den Menschen, sie kann töten und sie kann beleben.

Als Brennpunkt von Bedürfnissen und Sehnsüchten motiviert sie uns, sie zu verändern, zu verfremden, mit ihr zu spielen, sie auszubeuten.

Sie ist Ergebnis einer geistigen Ordnung und birgt in sich das Verlangen, gegen diese Ordnung anzukämpfen. Sie wird verändert und sie verändert uns. Dieses Kräftemessen ist für uns Existenz und Sinn.

Die Stadt impliziert also den Willen zu einer ganz genau definierten Stadtidee, wobei die Bewohnbarkeit eng mit ihrer Identifizierbarkeit zusammenhängt. Nur wenn eine Umgebung identifizierbar ist, kann sie den Bewohnern in ihrer Gestalt und ihren Symbolen bewusst werden, und so sinnvoll und verständlich erscheinen. Aus dem gemeinsamen Verständnis ihrer Bedeutung entsteht ein Zugehörigkeitsempfinden, ein sich Daheim fühlen. Wohnen im existentiellen Sinn ist Zweck der Stadt.

Architektur ist Mittel zu diesem Zweck. Die Grundelemente einer Stadt und ihre räumlichen Zusammenhänge verschmelzen das Stadtgefüge zu einer Einheit.

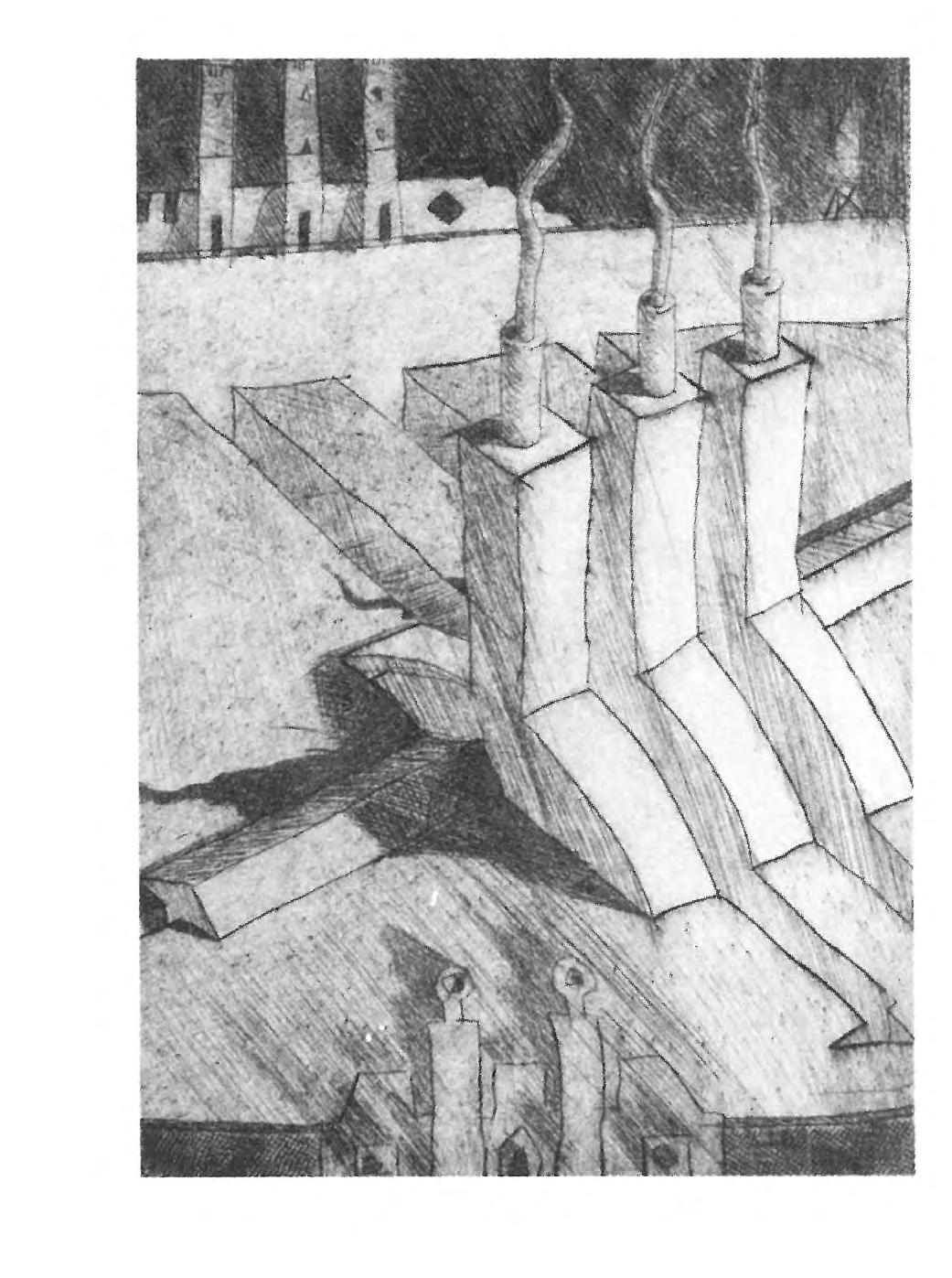

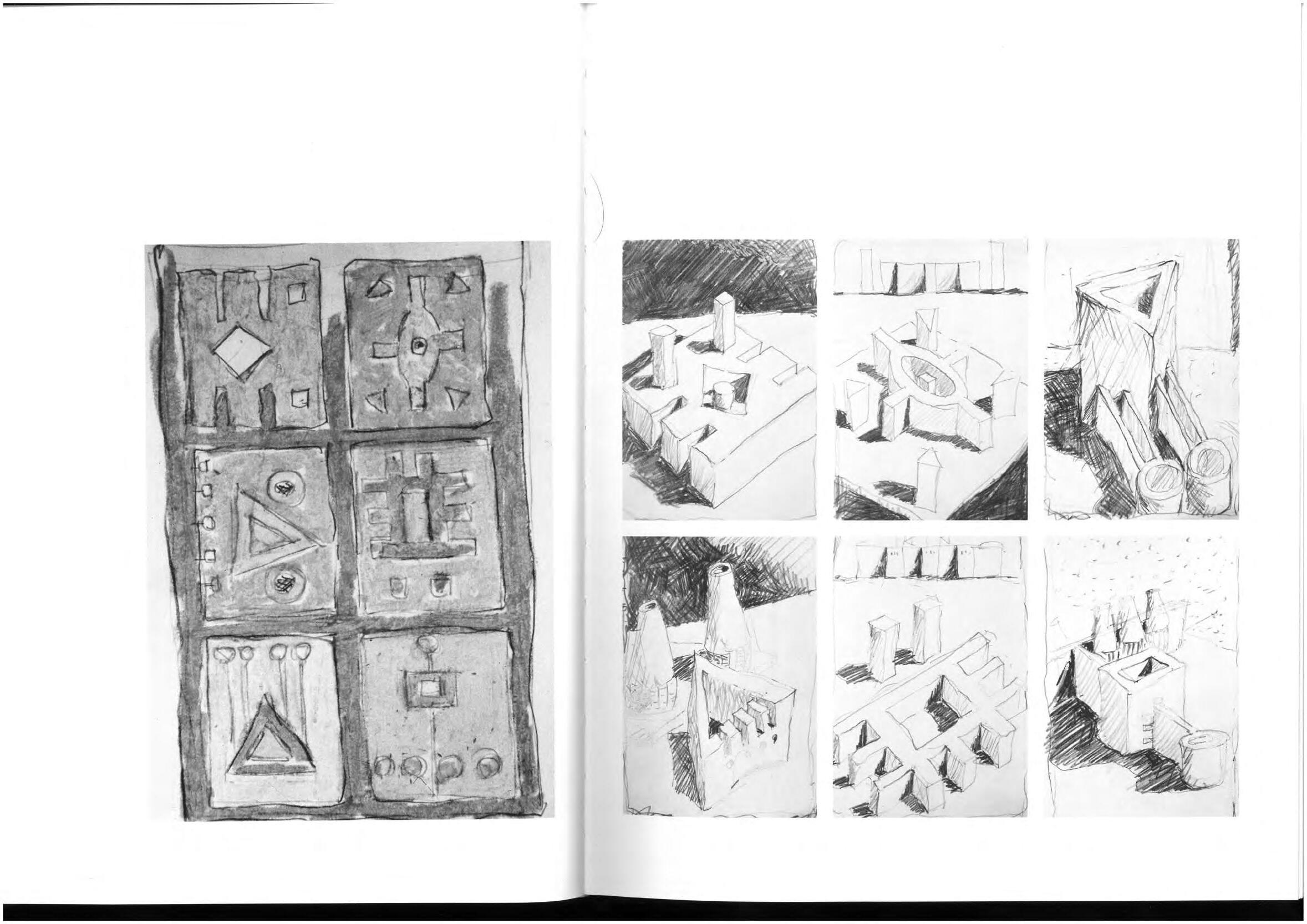

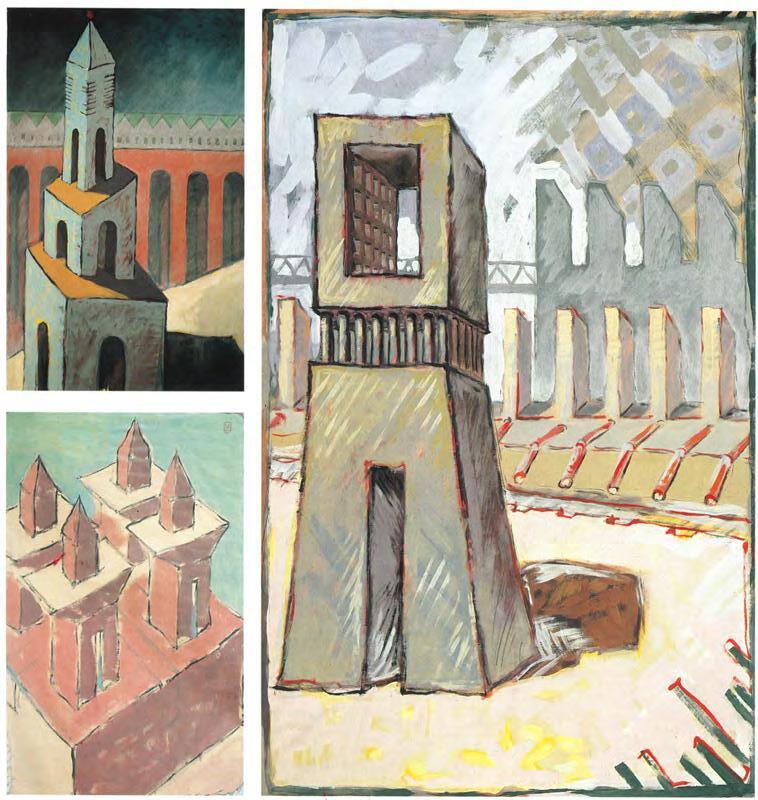

Left: Typologies of cities as a composition of square, triangle and circle, 1989 Pencil and pastel 12 x 15 cm

Right: Typologies relating to space Pencil 12 x 15 cm

The function of cities is living, in the existential sense.

Architecture is the means to this end.

The essential elements of a city and its spatial correlations melt the city structure into one unity.

Streets and squares give character to urban areas. They form a spatial continuum as a negative image of the architectural structure and of the transparency of its hierarchy. The street as a route with a specific direction to a specific destination is the expression of a movement and so it is interesting in two different ways. As the regulator of urban development it is decisive, along with the topographical conditions, in the appearance of the town and for its growth.

In the Renaissance the hierarchy of the streets defined urban development. The street is not taken to be a homogeneous unit in itself, it consists of individually contrasting buildings, where only the width of the street and the height of the buildings are subject to legal limitations.

In contrast to this are the baroque avenue and the concept of the boulevard which developed in the 19th century. In the boulevards of Paris, for instance, the meaning of the city as a metropolis is reflected, in which the dominant position is not held by the buildings but by the street. The endlessness of the

Straßen und Plätze prägen städtische Außenräume. Sie bilden als Negativform der Bebauungsstruktur und aus der Ablesbarkeit ihrer Hierarchie ein räumliches Kontinuum. Die Straße als Weg mit einer bestimmten Richtung zu einem bestimmten Ziel ist Ausdruck einer Bewegung, die für den Stadtorganismus also in zweifacher Hinsicht interessant ist. Als Regulativ städtischer Entwicklung ist sie neben den topographischen Gegebenheiten ausschlaggebend für das Erscheinungsbild der Stadt und ihres Wachstums.

In der Renaissance definierte die Hierarchie der Straßen den Städtebau. Die Straße wird nicht als ein einheitliches Ganzes aufgefasst, sie setzt sich aus individuell abgesetzten Bauten zusammen, wo lediglich die Breite der Straße und die Höhe der Bebauung einer Gesetzmäßigkeit unterliegen.

Im Gegensatz dazu steht die barocke Avenue und der sich im I9. Jahrhundert entwickelnde Begriff des Boulevards. In den Boulevards von Paris z.B. spiegelt sich die Bedeutung der Stadt als Metropole, als Großstadt, in der nicht die Gebäude, sondern die Straße die dominierende Stellung einnimmt. Die Unendlichkeit von Metropolis spiegelt sich in der fast endlosen Straße, gesäumt von Bäumen und uniformen Häusern. Ein Phänomen in der Geschichte der Architektur, das, wie wir glauben, bis heute seine Gültigkeit behalten hat.

Im Platz dagegen konkretisiert sich die zeitliche Dimension. In ihm wird die Bewegung angehalten und wird zur Dauer. Ist die

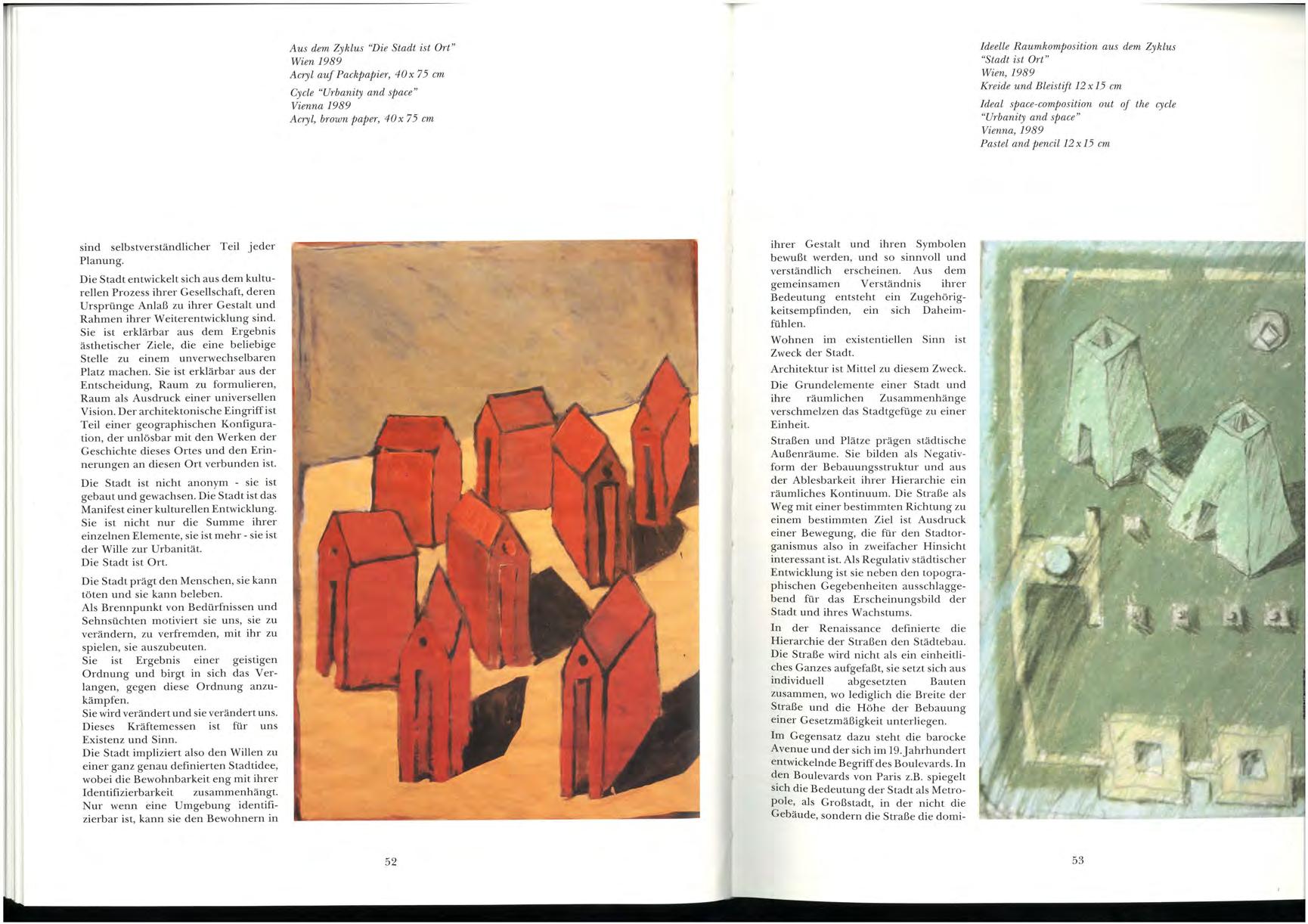

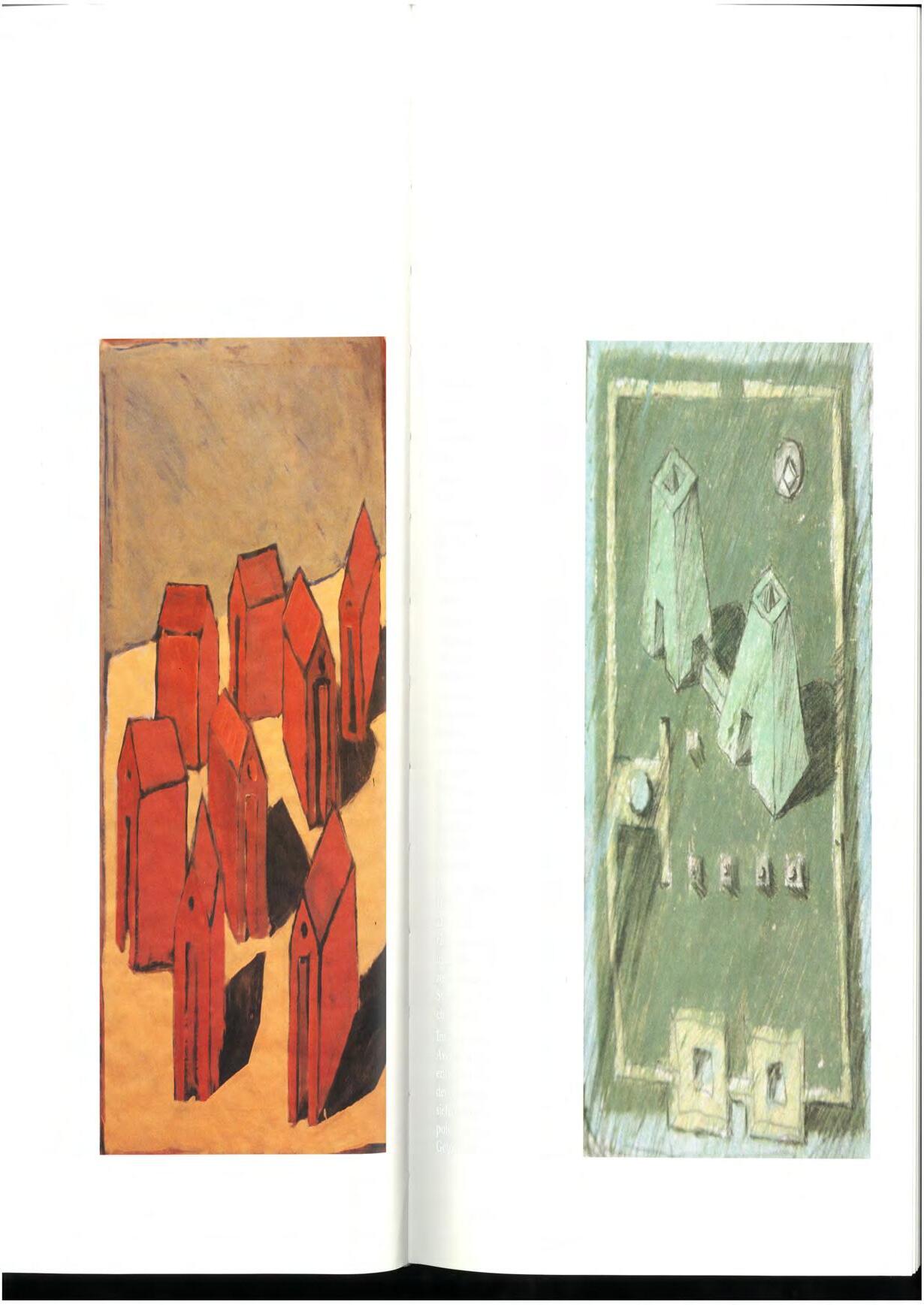

Cycle “Urbanity and space”, Vienna 1989, Acryl, brown paper, 40 x 75 cm

Ideal space-composition out of the cycle, “Urbanity and space”, Vienna, 1989, Pastel and pencil 12 x 15 cm

idea of metropolis reflects itself in the almost endless street, lined with trees and uniform houses. It is a phenomenon in the history of architecture which, we believe, has retained its validity up to the present day.

The square, on the other hand, is the concrete expression of the temporal dimension. In it, motion is halted and becomes everlasting. If the street is defined mainly by the length dimension, then breadth is of equal importance for the square. The motionlessness of the square makes it the symbol of lingering and reflection.

The layout and content of the city is accentuated by the architecture of its monuments. The monument marks a special position in contrast to the multiplicity of buildings, which make

Straße hauptsächlich durch ihre Längendimension definiert, so gewinnt beim Platz die Breite eine gleichwertige Bedeutung. Die Statik eines Platzes macht ihn zum Symbol des Verweilens und des Sich-Versammelns.

Räumlich und inhaltlich akzentuiert wird die Stadt durch die Architektur ihrer Monumente. Das Monument markiert im Gegensatz zu der Vielzahl von Gebäuden, die in ihrer Konformität einen Platz oder eine Straße bilden, einen speziellen Punkt. Das Monument ist ein konkretes Identifikationsobjekt. Als primäres Element der Architektur ist es inhaltlich Zeichen eines kollektiven Willens, in dem die Gemeinschaft ihren dauerhaften Ausdruck findet. Räumlich kennzeichnet das Monument spezielle städtische Zusammenhänge und topographische Fixpunkte. Monumente sind letzte Überbleibsel der kultisch-magischen Ursprünge der Architektur.

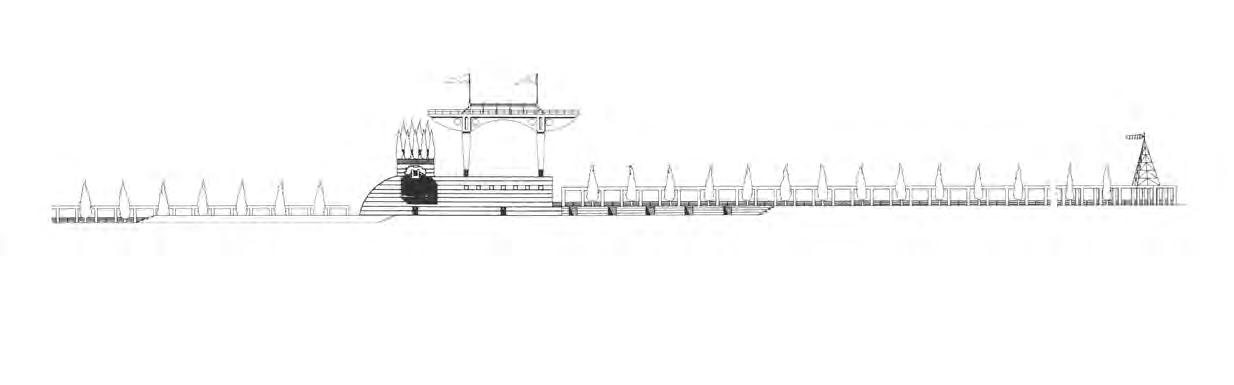

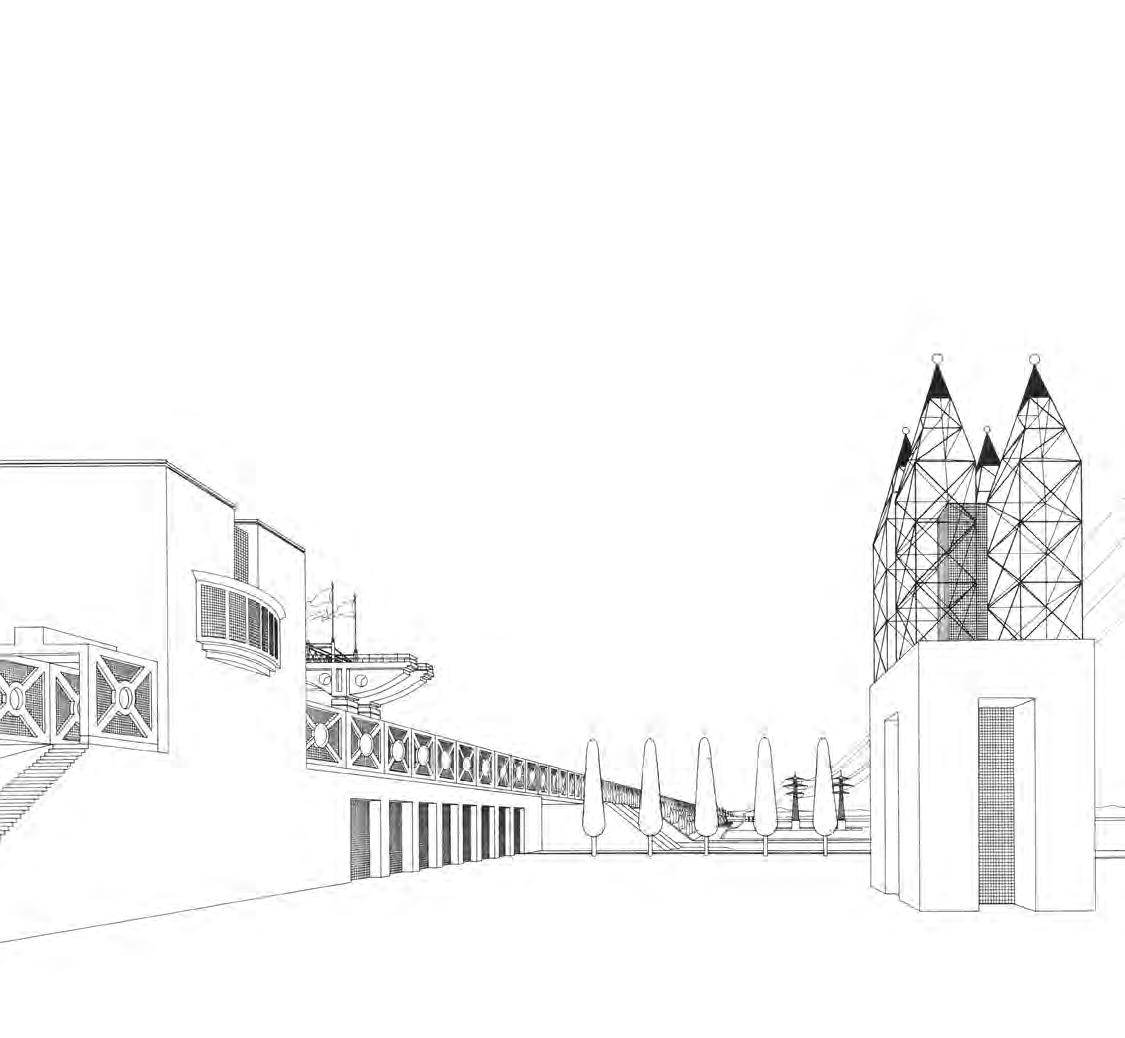

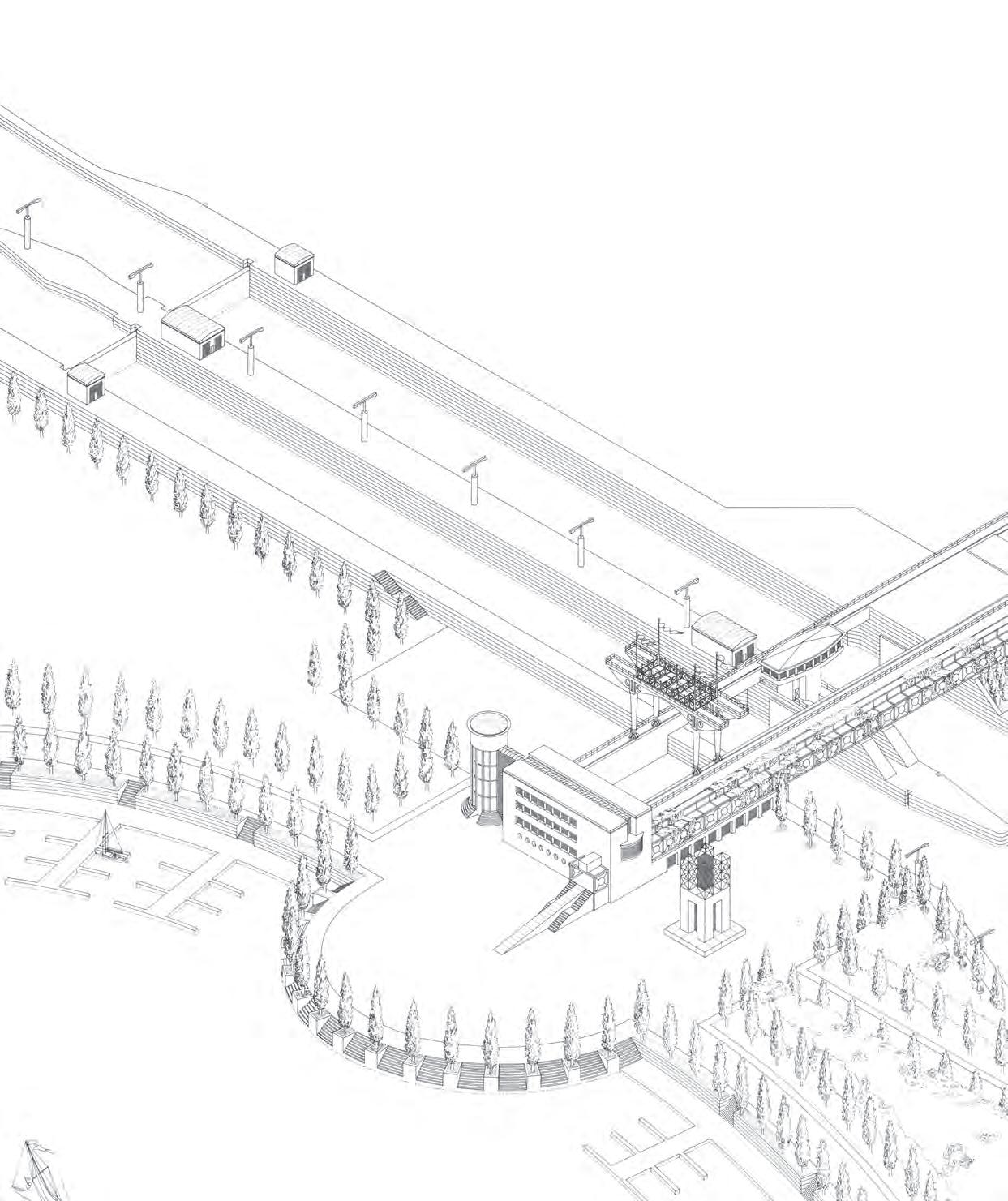

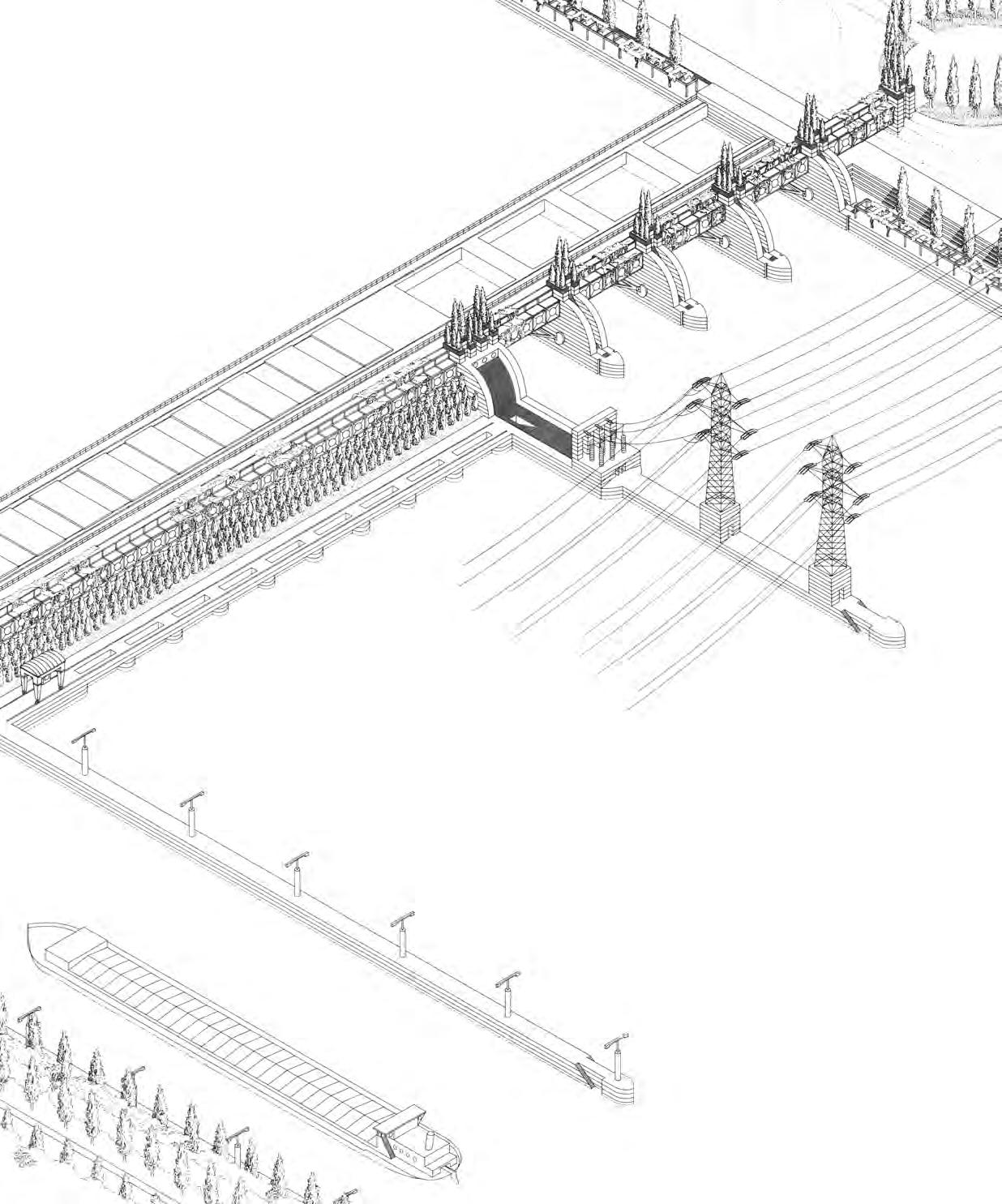

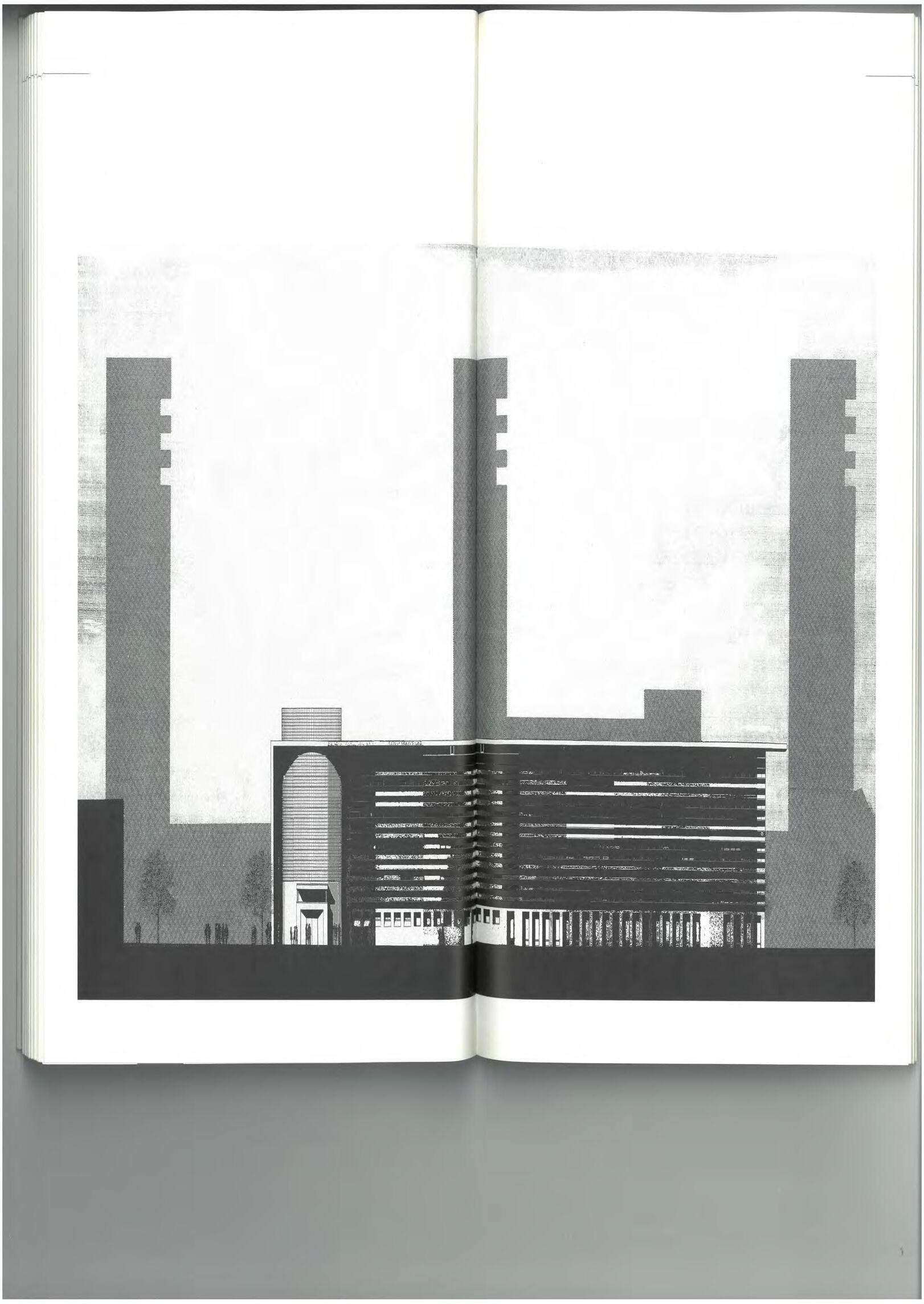

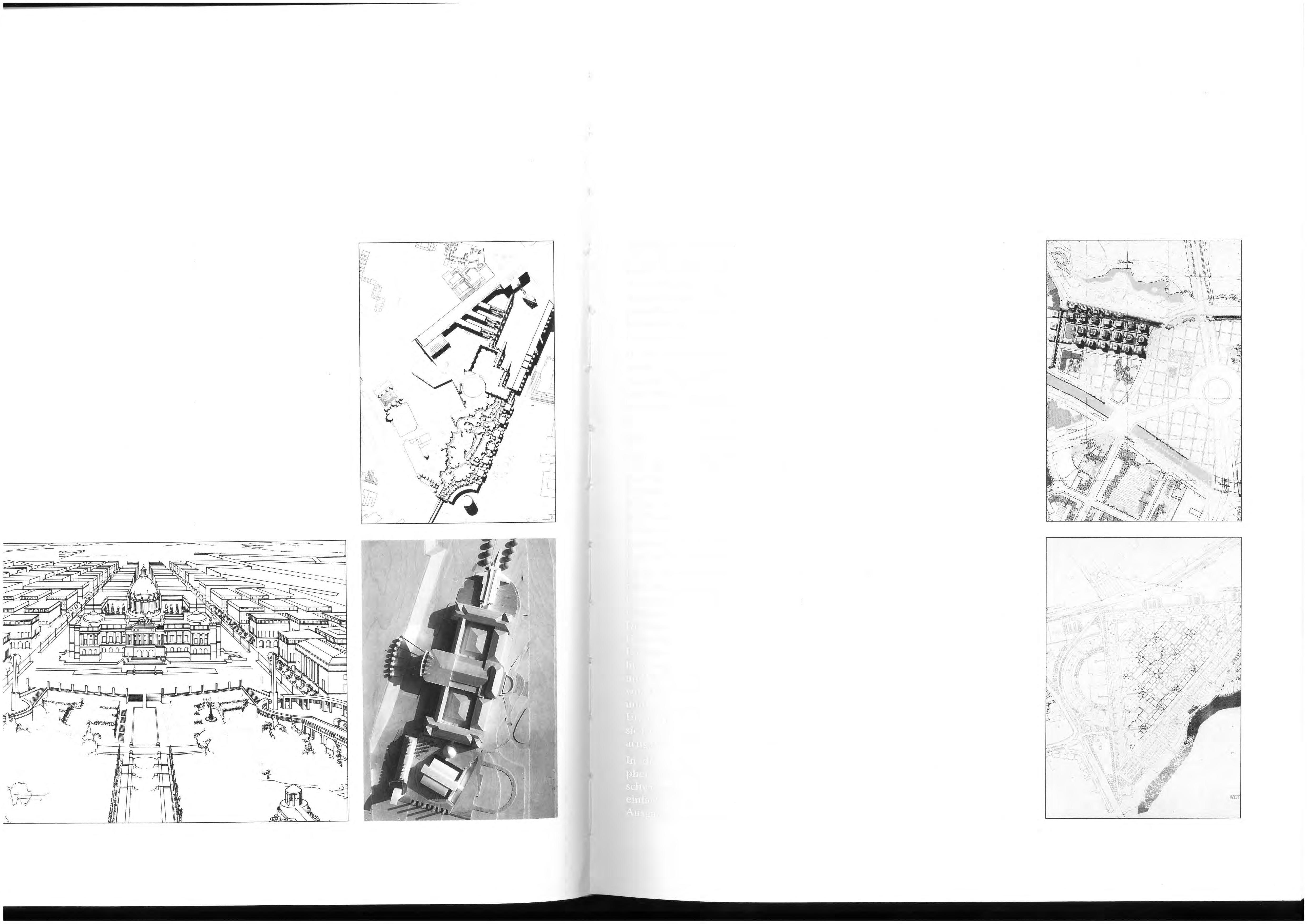

From left: Urban space for St. Paul, Minnesota, USA, 1987; Urban conception for the Anhalternahnhof, Berlin, 1984 & Urban conception for the expansion of Museum for technical science in Vienna, 1990

arises from it. The order which arises is grammar, the starting -

chitectural ability and will. It reveals a multiplicity of possibilities of interpretation and transformation, it is the origin of a complex -

Finding order in the formlessness of the peripheral areas is a difficult problem, for we lack an initial conception as a starting point. Uncontrollable spreading and the unregulated nature of development led to this chaotic situation. That is why it is valid, if we reject the radical option of demolishing the suburbs, which would certainly be a correct decision in some cases, to redefine

Individualität und architektonischem Können und Wollen. Sie eröffnet eine Vielzahl von Möglichkeiten der Interpretation und Transformation, sie ist der Ursprung eines komplexen Stadtbildes, sie ist der Rahmen für die Verschiedenartigkeit der Architektur der Bauten.

In der Gestaltungslosigkeit der Peripherie eine Ordnung zu finden, ist ein schwieriges Problem, hierzu fehlt einfach das Konzept, welches Ausgangspunkt dafür sein könnte. Ein unkontrollierbares Sich-Ausbreiten und die willkürliche Form der Bebauung führte zu diesem chaotischen Zustand. Deswegen gilt es, sieht man davon ab, die Vorstädte radikal abzureißen, was in manchen Fällen sicher eine richtige Entscheidung wäre, ganz im Sinne des Futurismus, sie neu zu formulieren.

Neuformulieren in zweifacher Hinsicht: – erstens durch Festlegen und Sichtbarmachen sinnvoller Grenzen, die der Stadt von außen her Gestalt geben und sie wieder als Einheit identifizierbar und als Antithese zum Land spürbar machen; – zweitens den Mangel an Identifizierbarkeit von Straßen und Plätzen durch das Hineininterpretieren einer Hierarchie von räumlichen und sozialen Bedeutungen wettzumachen. So können öffentliche Außenräume entstehen, die als architektonischer Faktor Aussage über das Gemeinsame der hier lebenden Menschen machen. Die Bebauung ist so zu korrigieren, dass ein räumliches Kontinuum von Straßen und Plätzen entsteht, ein Kontinuum von dreidimensional erfassbaren Räumen.

chitectural factor, make a statement about the common identity -

rected so that a special continuum of streets and squares results, a continuum of three-dimensionally comprehensible areas.

Aus der Komplexität dieser räumlichen Abfolgen können autonome identifizierbare Subzentren entstehen, überschaubare soziale Bereiche, gekennzeichnet durch die Verschiedenheit der Räume und der Architektur – eine Utopie innerhalb der gebauten Realität. Im vorigen Jahrhundert definierte der französische Städteplaner Haussmann zum ersten Mal die Stadt als technisches Problem, als ein Problem des Transportes und des Verkehrs, der großen

Urban conceptions for residential buildings Berlin Tiergarten, 1981

Autonomously identifiable subcenters can arise from the complexity of theses spatial results, overseeable social areas, characterized by the varying nature of the spaces and of the architecture – a utopia within the reality of development.

In the last century the French town planner Haussmann defined the city as a technical problem, a problem of transport and traffic, a problem of large distances. It is no longer the pedestrian that forms the focal point of the town planner’s thoughts, but the demands of the recently arrived industrial era. These thoughts were taken up in the works of the building engineer Soria y Mata and in the visions of Sant’Elia and Le Corbusier. It is no longer constructed architecture that has constituting significance but the transport vehicle. The city thus loses its definitive form, its urban character in the sense of our culture is therefore lost.

In contrast to the traditional city, the urban space in the modern metropolis is strongly dominated by the transport buildings and their symbolism. The ambivalence of urban meaning and architectural quality, together with the devastating effect of traffic, has left the historically developed city structure in an almost irreparable condition. The cities whose substance is modest and historically second rate have suffered a fatal peak of this traffic aestheticism. The engineering craft of the 19th century, incorporating it, was reduced to a service science, in which cold calculation and tastelessness cramped the intuition of architecture. The early engineered buildings were before their time, they reflected the contemporary spirit. In spite of this, they gave in to the historical context. Today, as with traffic itself, a clear aggressivity forms the basis for the planning of these buildings. So urban substance and civic living space have to play second fiddle to the transport routes, so that they are planned in a “car conscious” fashion.

Distanzen. Nicht mehr der Fußgänger steht im Mittelpunkt der Überlegungen des Städteplaners, sondern die Forderungen des angebrochenen Industriezeitalters. In den Arbeiten des Straßenbauingenieurs Soria y Mata und in den Visionen Sant-Elias und Le Corbusiers wurden diese Gedanken aufgegriffen. Nicht mehr die gebaute Architektur hat konstituierende Bedeutung, sondern das Verkehrsmittel. Die Stadt verliert damit ihre definitive Gestalt, ihr urbaner Charakter im Sinne unserer Kultur geht damit verloren.

Im Gegensatz zur traditionellen Stadt wird der städtische Raum in der modernen Metropole stark von den Verkehrsbauten und ihren Symbolen beherrscht. Die Ambivalenz von urbaner Bedeutung und architektonischer Qualität hat gemeinsam mit der verheerenden Wirkung des Verkehrs die historisch gewachsene Stadtstruktur in einen kaum reparablen Zustand versetzt. Ein fataler Höhepunkt dieser Verkehrsästhetik hat jene Städte betroffen, deren gewachsene Substanz bescheiden und historisch zweitrangig ist. Die Ingenieurkunst des 19. Jahrhunderts, wurde auf eine Dienstleistungswissenschaft reduziert, in der kaltes Rechnen und Geschmacklosigkeit die Intuition der Baukunst verdrängt. Die frühen Ingenieurbauten waren ihrer Zeit voraus, sie reflektieren Zeitgeist. Trotzdem gingen sie auf den historischen Kontext ein. Heute liegt der Planung dieser Bauten, analog dem Verkehr selbst, eine deutliche Aggressivität zu Grunde. So muss urbane Substanz und städtischer Lebensraum den Verkehrswegen weichen, um „autogerecht“ verplant zu werden.

Blinde Verkehrskonzepte haben die Proportionen, das urbane Gefüge und die Erlebbarkeit der öffentlichen Außenräume als Spiegelbild öffentlichen Lebens zerstört. Gleichmäßig werden die Fahrspuren über historische Stadtkerne gezogen, ohne Rücksicht auf das bestehende Stadtbild zu nehmen, ohne Maßnahmen für ein neues visionäres Stadtbild zu treffen.

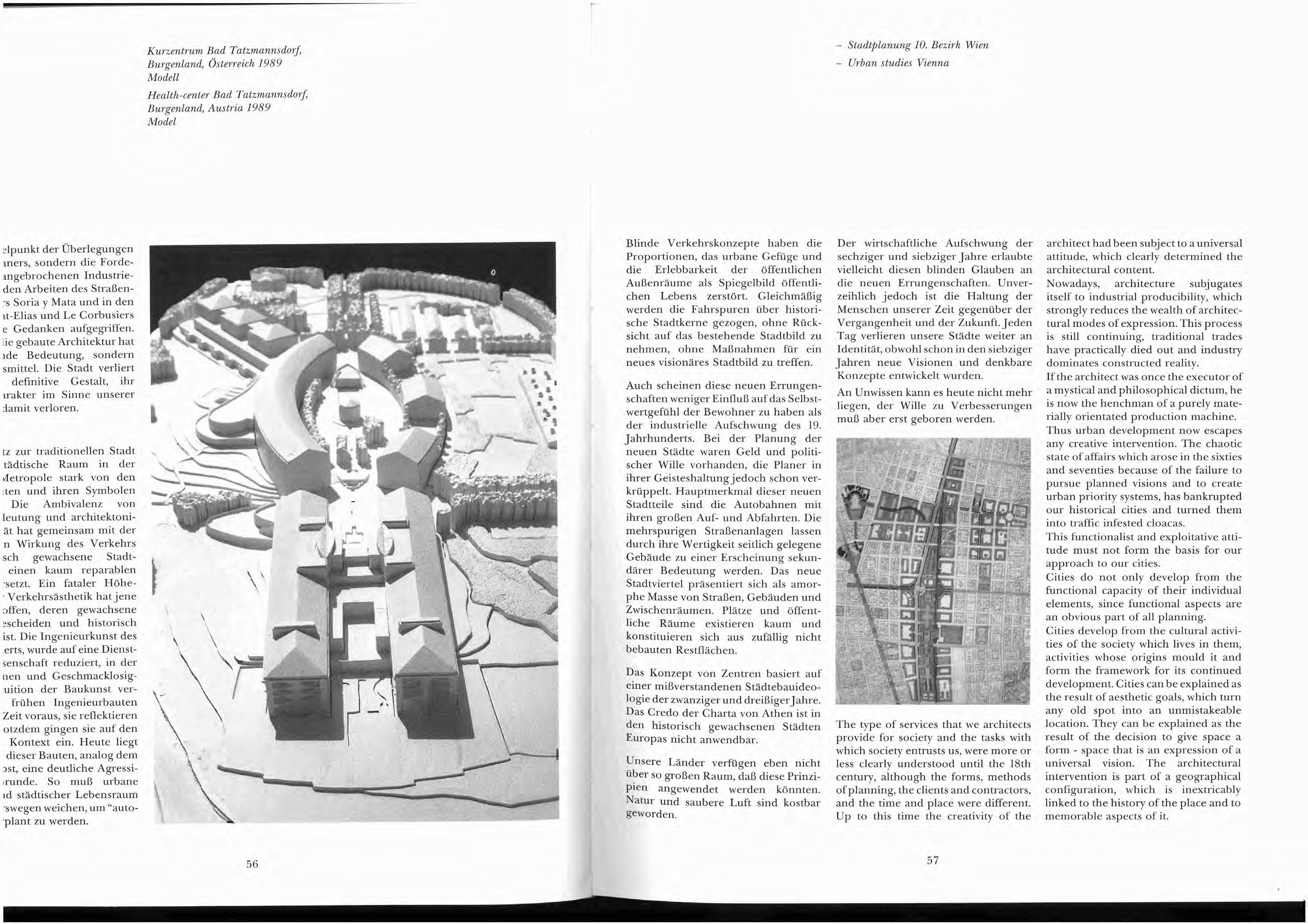

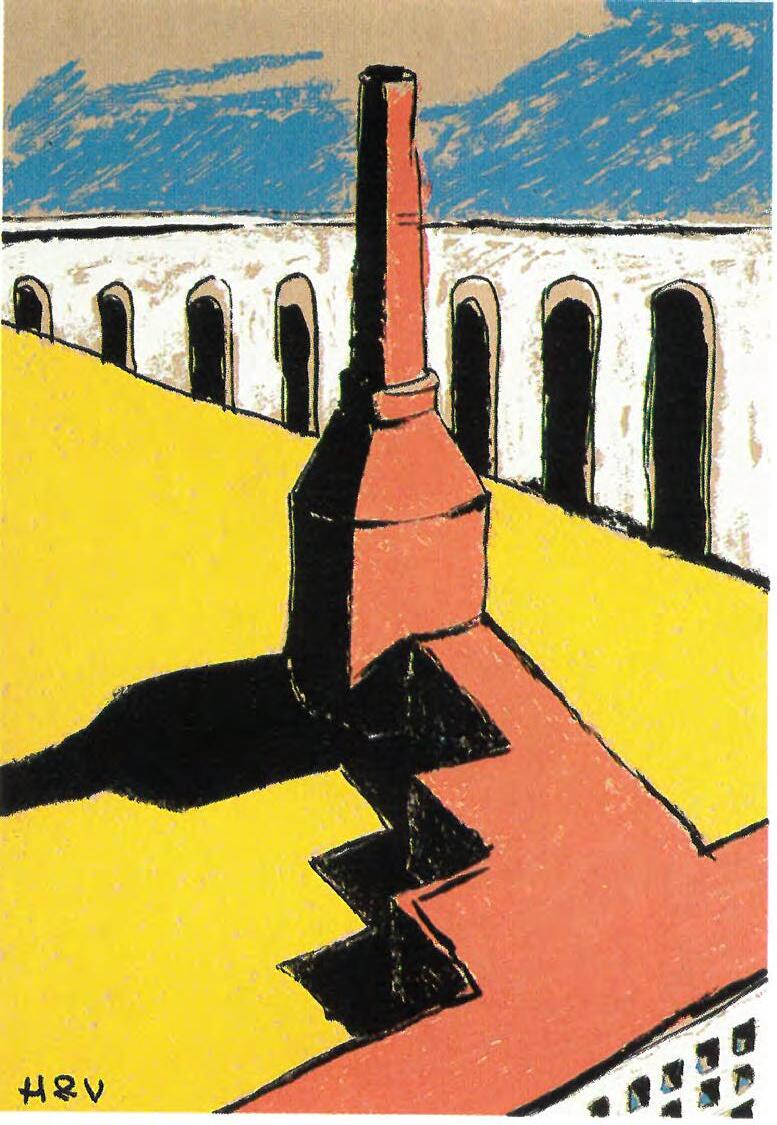

Urban studies for Vienna’s 10th district

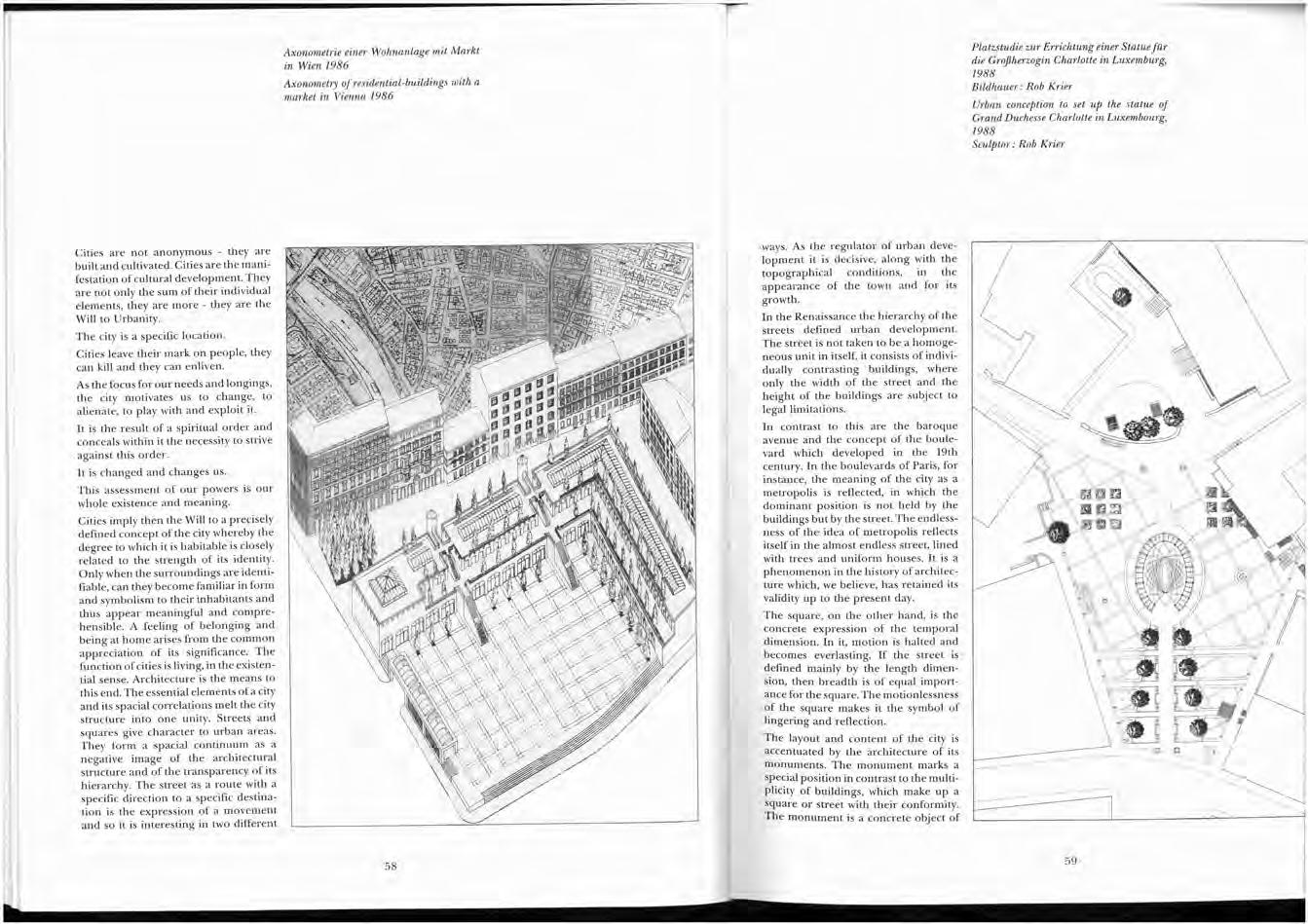

Axonometry of residential buildings with a market in Vienna 1986

Urban conception to set up the statue of Grand Duchesse Charlotte in Luxembourg, 1988, Sculptor: Rob Krier

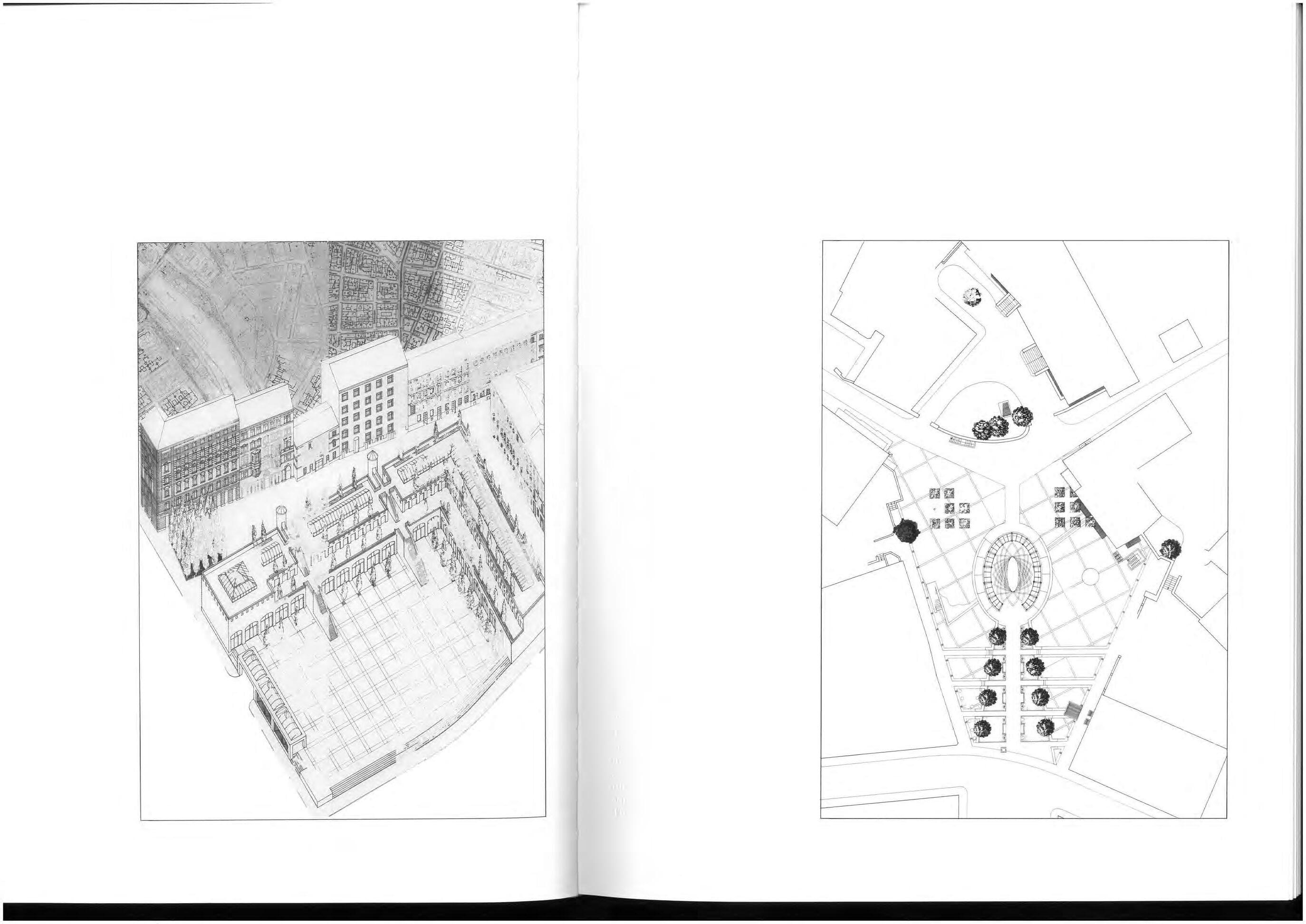

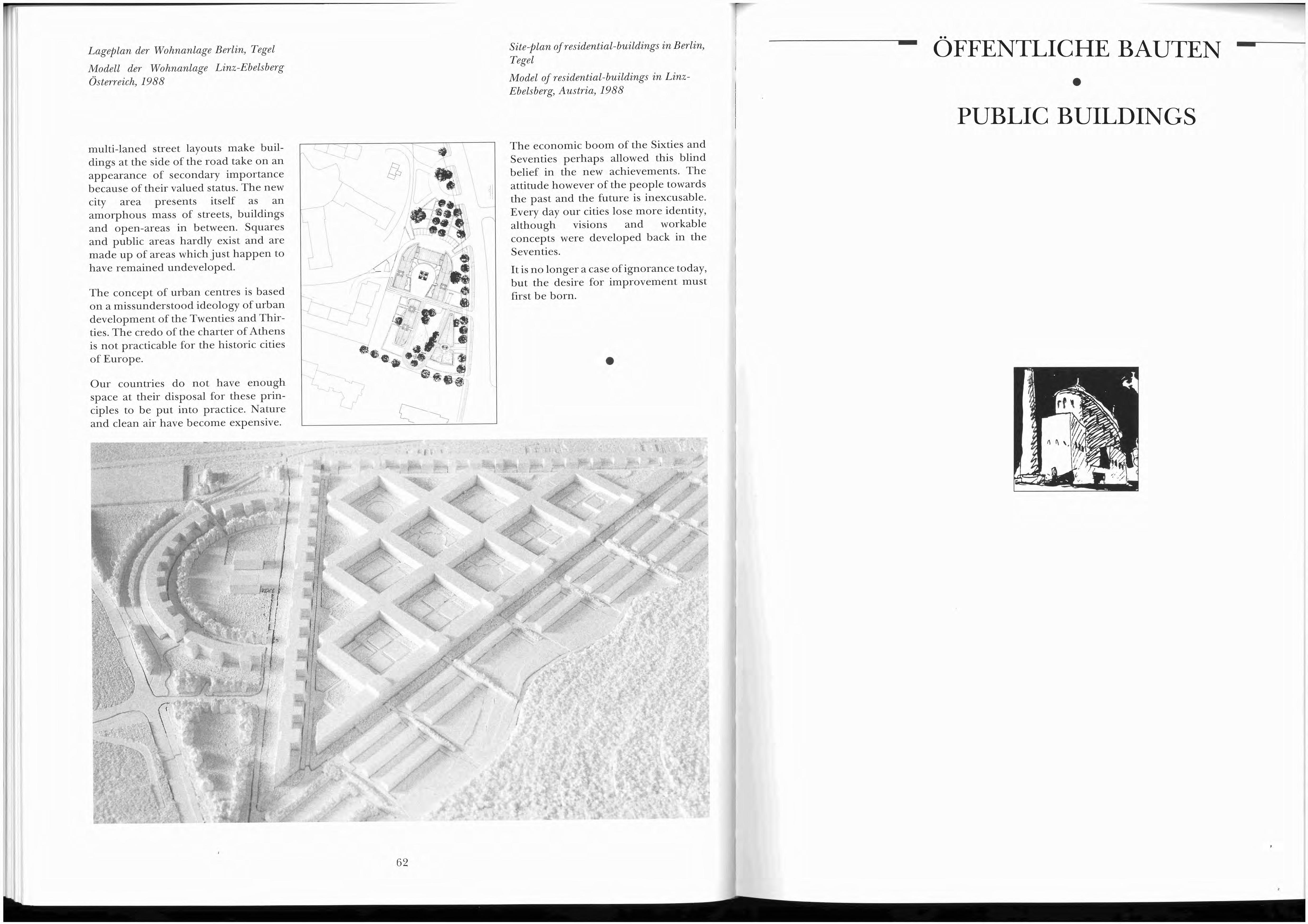

Site-plan of residential-buildings in Berlin-Tegel

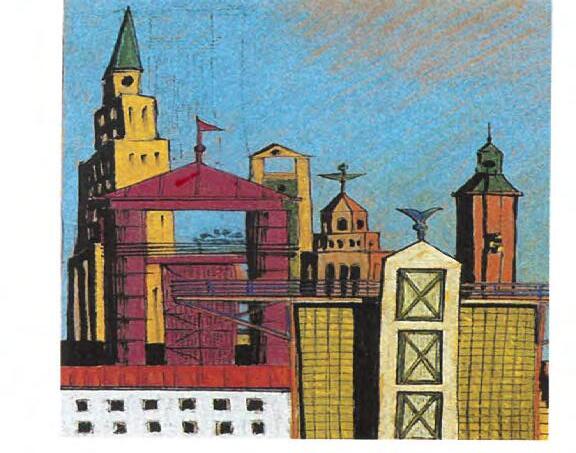

Cycle “Urbanity and space”, Venice/Luxemboug 1988/89, Acryl, brown paper, 40 x 75 cm, Variations on typologies of towers, Acryl, canvas, 1989, 60 x 85 cm

Impressions of New York, 1988, Acryl, paper 60 x 85 cm

Cycle

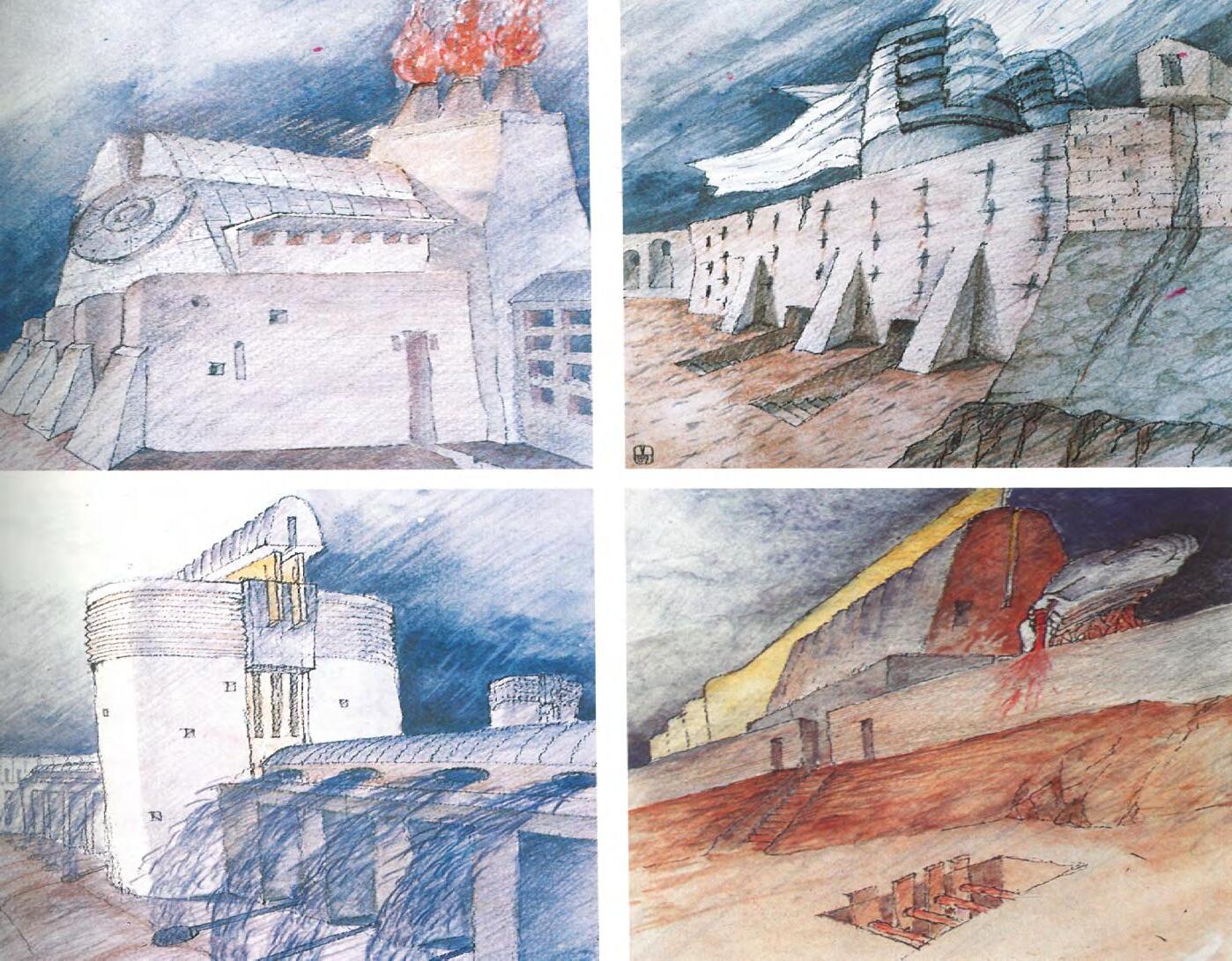

“Houses for the elements”, House of the fire, House of the wind, House of the water, House of the earth, Vienna 1989, Pastel, pencil 12 x 15 cm