25 minute read

Danny Lyon

from Play-Doc 2022

by PlayDocFest

Danny Lyon: Filmar contra os procedementos de exclusión / Filming Against Exclusion Procedures

Primeira retrospectiva internacional / First International Retrospective

Advertisement

Os desprazados. Notas sobre os filmes de Danny Lyon. T he Displaced. Notes on Danny Lyon’s Films.

Prefiro dar a este texto a aparencia de notas tomadas en limpo, pero conservando o seu carácter espontáneo. Aquí paréceme imposible facer outra cousa: ao cabo, sei demasiado pouco sobre o cinema de Danny Lyon, non sei nada dos modos de produción que lle permitiron realizar tantas películas nun período de vinte e cinco anos, e tampouco sei nada sobre a súa forma de distribución (redes de televisión por cable?, circuíto militante?). E a documentación (esencialmente I prefer to give this text the appearance of notes taken neatly, but retaining their spontaneity. It seems impossible to me to do otherwise here: in the end, I know just too little about Danny Lyon's cinema, nothing about the modes of production that have allowed him to make so many films over a period of twenty-five years, and nothing about their mode of distribution either (cable TV networks?, a militant circuit?). And there is a lack of documentation (which is essentially

estadounidense) é escasa, ou resulta aínda case inaccesible. Presentar un texto denso e vertical sobre o Danny Lyon cineasta podería dar como resultado algo semellante a unha mentira: un discurso de especialización. Pero non significa eludir estes filmes o negarse un a propoñer máis nada que unha serie de notas. Ao contrario, é obedecer ao seu sentido propio: se hai algo que pareza guiar a mirada de Danny Lyon, é precisamente un noxo profundo, orixinal e arraigado ante toda forma de dominación. Textos que lles impoñen aos homes o trazado físico e cartográfico dos seus desprazamentos. Decretos ministeriais ou rexionais que lles ditan a determinados corpos, de determinada cor ou que se expresan en determinadas linguas, que non deben cruzar tal ou cal fronteira; caso contrario, pagarán o prezo do abandono: o aceptar non vivir dunha forma que non sexa na clandestinidade, con todo o que iso comporta de pobreza, perigo e desigualdades. Textos legais escritos polos vencedores e que delimitan unhas zonas nas que entrar significa renunciar a algo da propia liberdade orixinaria. Os seus filmes levan o rexeitamento do control gravado na súa propia escritura. As películas de Danny Lyon non se ven desde hai décadas. E se ese descoñecemento procedese dos apertos mesmos en que meteron estes filmes aos seus patrocinadores nos Estados Unidos, fosen as televisións, as institucións, as redes activistas ou a crítica? As películas de Lyon non responderon espontaneamente ao traballo de caricatura da realidade que uns e outros, por razóns a miúdo encontradas, esperaban delas. Véndoas hoxe constátase que non eran nin condescendentes dabondo nin simplistas dabondo. Que lles reprochaban aos documentais de Danny Lyon? Talvez que cresen de máis na Realidade. Risos. Non querían servirse dunha fermosa e enfática voz en off para fundamentar un propósito ou unha causa que só pedise iso. Non, Lyon debeu de dicir para si, de cada vez, que poñer aí unha voz en off para falar dos inmigrantes ilegais que cruzan a fronteira por Arizona, como nesa extraordinaria escena de El Otro Lado (a súa película máis fermosa?, na miña opinión si), sería igual que falar en lugar do outro. Non esconderse tras o comentario era aínda unha decisión moi minoritaria, pois, no cinema documental dos anos 70; só Frederick Wiseman American), or it is still almost inaccessible. To present a massive, vertical text on Danny Lyon as a filmmaker might produce something like a lie: a discourse of mastery. But it is not to shy away from these films to refuse to propose anything other than a series of notes. On the contrary, it is to observe their very meaning: if there is one thing that seems to direct Danny Lyon's gaze, it is precisely a profound, original, deeply-rooted disgust for all forms of domination. Texts that impose on men the physical, cartography layout of their movements. Ministerial or regional decrees that dictate that certain bodies, of a certain colour, or speaking certain languages, must not cross this or that border, or else pay the price of abandonment: that they must accept to live in no other way than in hiding, with all that this implies in terms of poverty, danger and inequality. Legal texts written by the victors and delimiting zones; to enter these is to give up something of one’s own original freedom. The rejection of control is embedded in the very writing of his films. Danny Lyon's films have not been seen for decades. What if this lack of recognition came from the very embarrassment these films were to their sponsors in the United States, whether it was televisions, institutions, militant networks or critics? Lyon's films did not spontaneously respond to the work of caricature of reality that all such sponsors, for often opposing reasons, expected from them. Watching them today, one can see that they were neither condescending nor simplistic enough. What were Danny Lyon's documentaries criticised for? Perhaps the fact that they believed too much in Reality. Laughter. They did not want to use a nice emphatic voiceover to support a point or a cause that was just asking for it. No, Lyon must have told himself each time that putting a voice-over there to talk about illegal immigrants crossing the border through Arizona, as in that extraordinary scene in El Otro Lado (his most beautiful film?, in my opinion, yes), would be like speaking in the place of the other. Not hiding behind the commentary was still very much of a minority decision, then, in the documentary cinema of the 70s. Only Frederick Wiseman seemed to stick to it. In the case of Danny Lyon, given the populations that inhabit his films, the absence of voice-over is a determining

parecía acollerse a ela por entón. No caso de Danny Lyon, dada a poboación que habita as súas películas, a ausencia de voz en off constitúe un factor determinante a partir do cal as cintas se inscriben nunha postura política. A pregunta esencial do seu cinema desde finais dos anos 60 formulouna en 1985, en termos potentes e esclarecedores, Gayatri Spivak: Can the Subaltern Speak? Si, poden falar os subordinados? Pregunta política, pregunta filosófica. Pero trátase tamén, e antes de máis, dunha pregunta de cineasta; un documentalista que formula ao longo da súa vida a cuestión dos exiliados, dos emigrantes, os sen papeis e os presos tamén formula para si, en primeiro lugar, a cuestión da palabra: quen toma a palabra?, quen a asigna? Lyon podería roubarlla, roubarlle a palabra á minoría. Quen ía reparar niso? No entanto, decide non facelo, non falar por eles. Impón para si a prohibición de facelo. A partir dese momento, atopa para si mesmo un lugar de cineasta, un lugar moi cativo, estreito, mais precioso: el é o que relata unha experiencia. Non filma para tomar a palabra, senón para a transmitir. Pero como a transmite? Situándose xunta deles, filmando desde o seu carón, mais sen facer crer tampouco que é un deles. En todo momento, o lugar desde o que filma lémbranos que el é externo a eles, diferente deles. Non vai facer de emigrante mexicano, de indocumentado nin de preso. A súa posición determina outra cousa, moi sutil: dinos quen é, a saber, un fotógrafo e cineasta estadounidense, branco e libre. A súa situación non é comparable á deles. Porén, a súa liberdade non tería o mesmo sabor se non dese conta de vidas distintas da súa, vidas que loitan por poder desprazarse libremente dun espazo a outro. E esta cuestión do movemento posible no espazo Lyon convértea nunha cuestión propia do cineasta. É a cuestión que o obriga, en determinados momentos da súa vida, a deixar por un instante a fotografía para rexistrar e plasmar desprazamentos sensibles. A cuestión da posibilidade (fluxo migratorio), mais tamén da imposibilidade (cárcere, clandestinidade), do movemento, do paso dun espazo a outro, tórnase a cuestión central do seu cinema. E Lyon formúlalles esta cuestión aos Estados Unidos, o gran país que fixo da travesía do territorio e da factor in the films' political position. The essential question of Danny Lyon's films since the late 60s was put in luminous and powerful terms by Gayatri Spivak in 1985: Can the Subaltern Speak? Yes, can the subaltern speak? A political question and a philosophical question. But it is also, and first of all, a filmmaker's question: a documentary filmmaker who asks the question of exiles, migrants, illegal immigrants or prisoners throughout his life also asks, in the first place, the question of speaking: who will speak? Who will assign the turn to speak? Lyon could steal that voice, the minority's voice. Who would notice? However, Lyon decides not to do so — not to speak for them. He forbids himself to do so. From then on, he finds a place for himself as a filmmaker, a very small and tight but precious place: he is the one who reports an experience. He does not film in order to speak but to transmit what is spoken. But how does he transmit that? He stands next to them; he films from their side but without making it look like he is one of them. The place from which he films always reminds us that he is external to them, different from them. He is not going to play the Mexican migrant, the illegal immigrant or the prisoner. His position determines something else, something very subtle: it tells us who he is, i.e. an American photographer and filmmaker, white and free. His situation is not comparable to theirs. But his freedom would not have the same taste if it did not reflect lives other than his own, lives that struggle to move freely from one space to another. And Lyon turns this question of the possible movement in space into a filmmaker's question. It is the question that obliges him, at certain times in his life, to leave photography for a moment to record movements and render them sensitive. The question of the possibility (migratory flow) but also of the impossibility (prison, clandestinity) of movement, of crossing from one space to another, becomes the central question of his cinema. And Lyon poses this question to America, the great country that has made the crossing of its territory and its conquest into a history, a moral doctrine and a mythology. His films always seem to have begun without us, and in a way they end as they began: without concluding anything definitive, without punctuation. Lyon hates conclusions. Danny Lyon's

As súas películas sempre parecen comezar sen nós e, en certo modo, rematan como empezaron: sen que se conclúa nada definitivo, sen puntuación. Lyon odia as conclusións. Todos os seus filmes teñen coidado de non levantarse sobre a ilusión dun clímax.

Cabe a posibilidade de que haxa dous Danny Lyon: o fotógrafo e o cineasta. Non, síntoo, non hai máis que un. O que coñeciamos era fotógrafo; o que non coñeciamos era cineasta. Iso é todo e aí, só aí, radica a diferenza. Na contraportada do seu libro The Bikeriders, arriscada obra sobre os Anxos do Inferno, pódese ler esta presentación: En 1965, Danny Lyon, veterano de 23 anos do movemento polos dereitos civís dos estados do sur, entrou no Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, montado nunha Triumph de 650 cc e disparando unha Nikon Reflex e unha Rolleiflex. Son lendarias as súas imaxes da vida carceraria, do movemento a prol dos dereitos civís no sur e das nacións indias estadounidenses. Entre os seus numerosos libros cóntanse The Destruction of Lower

Manhattan, Conversations with the Dead,

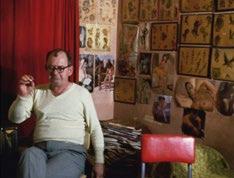

Knave of Hearts e Indian Nations. Lyon divide o seu tempo entre o val do Hudson (Nova York) e o val do río Grande (Novo México). Lyon vivía con Robert Frank e Mary na W 86th Street de Nova York cando realizou a súa primeira película, Social Sciences 127, sobre un artista da tatuaxe de Houston, Bill Sanders. Estabamos en 1969. Tamén a Robert Frank lle gustaba variar os medios e pasar da fotografía ao cinema; pero, en certa maneira, nunca procurou facer extensible a fotografía ao documental, senón que o cinema lle serviu para converter os Estados Unidos nun pequeno teatro, histérico (Pull My Daisy) ou mitolóxico (Candy Mountain). Lyon, pola súa banda, non fixo divisións. É coma se nunha escena el tivese postos os dous ollos, un para a fotografía e outro para a cámara. Pero como, que non son o mesmo? Abofé que non: son dous ollos que traballan en tempos diferentes. Un é para o Laocoonte, é dicir, vai á busca da pose máis fermosa, do instante preciso en que o suxeito se mostra na súa perfección estatuaria. O outro, por agora, non é xa There might be two Danny Lyons: the photographer and the filmmaker. No, sorry, there is only one Danny Lyon. The one we knew was a photographer. The one we did not know was a filmmaker. That is all; there, and only there, is where the difference lies.

On the back cover of his book The Bikeriders, a daring book on the Hell's Angels, one can read this presentation: In 1965, Danny Lyon, a 23-year-old veteran of the southern civil rights movement, joined the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club, riding a 650-cc Triumph and shooting with a Nikon Reflex and a Rolleiflex. His pictures of prison life, the southern civil rights movement and American Indian nations are legendary. His many books include The Destruction of

Lower Manhattan, Conversations with the

Dead, Knave of Hearts and Indian Nations. He divides his time between the Hudson Valley of New York and the Rio Grande Valle of New Mexico.

Lyon was living with Robert Frank and Mary on W 86th Street in New York when he made his first film, Social Sciences 127, about a Houston tattoo artist, Bill Sanders. It was 1969. Robert Frank, too, liked to vary his mediums, to switch from photography to film. But in a way, Frank never sought to extend his photography into his documentary work. He used his films to turn America into a small theatre, whether hysterical (Pull My Daisy) or mythological (Candy Mountain). Lyon, for his part, drew no divisions. It is as if he had both eyes on a scene – one eye for photography, another eye for the camera.

What, they are not the same? Of course not – they are two eyes working at different times. One is for Laocoön, that is, it goes in search of the most beautiful pose, the precise moment when the subject is shown in its statuary perfection. The other one is, for the moment, no longer specific but "no matter which one." It is the eye of cinema, and the pose is melted into a series of twenty-four photographs per second in which another power emerges: that of continuity, of movement and space seen in its disturbances. It is interesting to see what Lyon the filmmaker brings to Lyon the photographer. Or vice versa

un concreto senón «calquera»; é o ollo do cinema e a pose fúndese nunha serie de vinte e catro fotografías por segundo na cal xorde outro poder: o da continuidade, o do movemento e do espazo que se deixa ver nas súas perturbacións. É interesante ver o que o Lyon cineasta lle achega ao Lyon fotógrafo. Ou á inversa. O que o seu cinema perpetúa a partir das súas fotografías. Unicamente un exame sistemático dos dous arquivos nos permitiría teorizar ao respecto, así que contentémonos cunha mera intuición: o documental talvez lle ensinou a ser menos compositivo. A tradición fotográfica á que pertencía Danny Lyon soñaba cunha escritura xornalística que, non obstante, levaba no seu interior as regras da composición clásica. As súas fotos de The Bikeriders ou Conversations with the Dead importan a composición clásica á enerxía do cotián.

O cinema documental apresúrase a desconfiar das imaxes fermosas de máis e das composicións sólidas de máis. Sobre todo un cinema que, igual que o seu, como pode verse en El Otro Lado e en Little Boy (unha película curiosa, case experimental, na que amosa uns Estados Unidos brancos invadidos pola televisión, que confronta cuns Estados Unidos non representados, invisibles: o país dos inmigrantes ilegais, o dos pobos das reservas), moi pronto aprenderá a situar a súa investigación nun lugar distinto do da composición, mais adoptando unha forma de se situar el mesmo no interior dunha serie de desprazamentos que deciden sobre a supervivencia dos seus suxeitos. Así, pois, non é tanto o encadramento como o espazo e a duración o que lle serve de muletas para facer a imaxe. Volvo de novo á súa cinta máis rica, El Otro Lado. Non obstante, todas as películas de Danny Lyon son películas que buscan ir ao outro lado. Xa non as filma desde o seu propio espazo, senón que se incorpora a outro que está separado de nós pola fronteira trazada pola lei, un espazo milimetrado no que un mexicano aínda era un mexicano hai uns segundos e se converte en ilegal uns metros máis aló.

Cal é ese espazo que a fotografía non pode cubrir e que o cinema pode tentar salvar in extremis? Un espazo no que os sons resultan primordiais, porque alertan. O son das películas de Lyon leva en si a información que precisan para sobrevivir os que viven na clandestinidade. Ese espazo áchase sempre en confrontación cun son externo que dá – what his cinema perpetuates from his photographs. Only a systematic examination of the two archives would allow us to theorise about this, so let us make do with one mere intuition: documentary cinema may have taught him to be less compositional. The photographic tradition to which Danny Lyon belonged dreamed of a journalistic writing style that nevertheless carried with it the rules of classical composition. His photos in The Bikeriders or Conversations with the Dead import classical composition into the energy of everyday life. Documentary cinema is quick to distrust images that are too beautiful or too solidly composed. Especially a cinema which, like his own, as can be seen in El Otro Lado or in Little Boy (this funny, almost experimental film, in which he shows a white America invaded by television, which he confronts with an unrepresented, invisible America: that of the illegal immigrants, of the people of the reserves), will very quickly learn to locate its research elsewhere than in composition, but in a way in which it locates itself within a series of displacements that decide the survival of its subjects. It is not so much the frame, then, as the space and duration that become his crutches for making the image. I return once again to his richest film, El Otro Lado. However, all of Danny Lyon's films are films that seek to go to the other side. He no longer shoots them from his own space: he enters a space, separated from us by the border drawn by the law – a space graduated in millimetres, in which a Mexican was still a Mexican a few seconds ago and becomes an illegal immigrant a few metres further away. What is this space that photography cannot cover and that cinema can try to save in extremis? It is a space where sounds are paramount because they alert. The sound in Lyon's films carries the information that those who live in secrecy need to survive. This space is always in confrontation with an external sound that raises the alarm. The offscreen decides everything, Eisenstein noted. And Eisenstein knew a thing or two about playing with the rules of politics and the political. The very little editing in his films is also a result of this: to intervene as little as possible, so as not to move around in space in the place of the person being filmed, but also to allow the time for the

a alerta. O fóra de campo decídeo todo, sinalou Eisenstein. E Eisenstein sabía un par de cousas sobre como xogar coas regras da política e do político. A moi escasa montaxe das súas películas tamén é resultado diso: intervir o menos posible, para non desprazarse polo espazo en lugar da persoa filmada, mais tamén con obxecto de deixar o tempo necesario para que a información achegada polo son entre na imaxe, se despregue nela e lle resulte útil á acción que está a filmar, a cal é sempre unha acción de supervivencia. Unha nota ao final dos créditos de El Otro Lado: «A andaina polo deserto foi recreada polos seguintes traballadores indocumentados». Isto é importante: el non traballa como xornalista, para captar o instante, senón como cineasta, de ficción se é preciso, que se permite refacer a toma, noutro lugar, noutro momento, mais segundo uns parámetros de espazo e movemento que puido observar sen cámara, durante unha situación na que resultaba perigoso para os emigrantes que el acudise con cámara (poderían ser detectados). Iso non muda en nada o obxectivo das películas: dar a sensación dunha experiencia. Porén, cando chega o cinema, por veces é tarde de máis; o que sexa xa pasou. Mais o problema segue aí e aínda non se filmou. Así que hai que escenificar a acción unha segunda vez para que sexa oída na realidade. Dese primeiro visionamento das películas de Danny Lyon conservo a impresión de que para el o cinema só existe co obxecto de captar a experiencia: hai vidas, vidas invisibles, e o seu deber é captalas para contar unha historia. E para así lles dar a esas vidas clandestinas a posibilidade de un día, talvez, existir no visible. Niso consiste filmar contra os procedementos de exclusión.

Texto escrito por Philippe Azoury para o noso catálogo.

information brought by the sound to enter the image, unfold and become useful to the action he is filming, which is always an action of survival. A note at the end of the credits of El Otro Lado: "The desert walk was re-enacted by the following undocumented workers." This is important: he does not work as a journalist to capture the moment, but as a filmmaker, of fiction if need be, who allows himself to redo the shot, elsewhere, at another time, but according to the parameters of space and movement that he was able to observe without a camera, during a situation where it was dangerous for the migrants for him to come with a camera (they could have been spotted). This does not change the aim of the films one bit: to give the feeling of an experience. But by the time the cinema arrives, it is sometimes too late – it has already happened. However, the problem is still there and it still has not been filmed. So the action needs to be staged a second time to make it heard in reality. From this first viewing of Danny Lyon's films, I have the impression that for him, cinema only exists to capture experience: there are lives, invisible lives, and his duty is to capture these lives in order to tell a story. And thus to give these clandestine lives the possibility of perhaps existing in the visible space one day. That is what filming against exclusion procedures is all about.

Text written by Philippe Azoury for our catalogue.

SOC. SCI. 127

21′ / 1969 / EUA Sala 2 sábado Saturday ás 17:30 h

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon Son: Ed Hugetz, David Gerth Producida co apoio do American Film Institute

Filmado en Houston, Texas, en 1969, a primeira película de Lyon Soc. Sci. 127 trata sobre un excéntrico tatuador que bebe, fuma e que se aferra a unha cosmovisión caótica feita de opinións aleatorias sobre todas as cousas, desde a reveladora etimoloxía da palabra felación ás súas propias motivacións para facer unha película documental.

Llanito é a primeira película da súa triloxía filmada en Bernalillo, Novo México, e é tamén o debut na pantalla de Willie Jaramillo. A película deambula pola cidade e entre os seus habitantes, ás veces co agudo instinto dun aguia do deserto e outras cun estupor beodo, tropezando dunha escena a outra coa certeza visceral e irracional da atracción gravitatoria. Shot in Houston Texas in 1969, Lyon's first film Soc. Sci. 127 is about an eccentric, tattoo artist named Bill Sanders who drinks, smokes, and snatches at a matted worldview stitched together from haphazard opinions on everything from the telling etymology of “fellatio” to his own motivations for making a documentary film.

Llanito is the first of Lyon's trio of films shot in and around Bernalillo, New Mexico, and it is also the screen debut of Willie Jaramillo. The film meanders through the town and among its inhabitants, passing between groups of people at times with the keen instinct of a desert eagle and at others in a drunken stupor, stumbling from one scene into the next with the visceral and irrational inevitability of a gravitational pull.

LLANITO

52′ / 1971 / EUA Sala 2 venres Friday ás 19:30 h

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon

EL MOJADO

18′ / 1974 / EUA Sala 2 sábado Saturday ás 17:30 h

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon Son: Ed Bevan, James Blue, Stephanie Chrisman Producida por J.J. Meeker Cos Sawdust Boys de New Mexico

«El Mojado é unha película sobre o meu mellor amigo en Novo México, un traballador sen papeis, proveniente da zona rural de Chihuahua. El introduciume no incrible mundo dos “inmigrantes ilegais”». Danny Lyon. “El Mojado is about my best friend in New Mexico, an undocumented worker from rural Chihuahua. He introduced me to the whole unbelievable world of ‘illegal aliens’.” Danny Lyon.

LOS NIÑOS ABANDONADOS

63′ / 1975 / COLOMBIA Sala 1 domingo Sunday ás 18:30 h

LITTLE BOY

54′ / 1977 / EUA Sala 2 sábado Saturday ás 19:30 h

Estrea galega / Galician Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon Son: Paul Justman

En 1975 Danny Lyon viaxou a Colombia e realizou unha película impasible aínda que chea de lirismo, dedicada á crecente poboación de nenos sen fogar, vivindo nas rúas, abandonados polas súas familias e ignorados tanto pola Igrexa como polo Estado. In 1975 Danny Lyon traveled to Colombia and made an unblinking yet lyrical film dedicated to the surging population of homeless children living on the streets, abandoned by family and ignored by Church and State alike.

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon Montaxe e son: Paul Justman Subvencionada polo National Endowment for the Arts

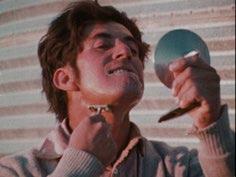

A bomba Little Boy lanzada sobre as xentes de Hiroshima, foi deseñada e probada en Novo México. Pero hai outro «little boy» chamado Willie Jaramillo. Aos dezaoito anos acaba de saír da prisión por unha serie de delitos menores. Mentres Lyon rolda as rúas preguntando a veciños e amigos por Willie, a película regresa á súa infancia, idílica en comparación co presente, e a historia dun home emerxe con máis importancia que a propia bomba atómica. The Little Boy bomb dropped on the people of Hiroshima was designed and tested in New Mexico. But there is another little boy, Willie Jaramillo. At age eighteen, he has just been released from prison for a series of minor offenses. As Lyon pounds his beat around town, asking friends and neighbors about Willie, the film jumps back in time to scenes from Willie's childhood and the history of one man's life emerges as a fact of greater significance than the atom bomb itself.

EL OTRO LADO

60′ / 1978 / EUA Sala 1 venres Friday ás 23:15 h

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon Asistente de montaxe: Alton Walpole Son: James Blue (Mexico), Michael Becker (Arizona) Realizada grazas ao apoio de The New Mexico Arts Commission, The National Endowment for the Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Parish Witness Program, American Baptist Churches

El otro lado foi filmado nos campos de cítricos do condado de Maricopa, unha vasta area agrícola próxima a Phoenix, en EUA. Nela preséntanos á familia Garey á que Lyon filma no seu fogar en México. O cruzamento ilegal da fronteira é unha reconstrución na que traballadores ilegais escenifican a súa entrada ilegal nos Estados Unidos. El otro lado was shot in the citrus groves of Maricopa County, a large agricultural area close to Phoenix. It features the Garey Family. Lyon traveled to Mexico to film the family in its, home. The illegal crossing of the border was a reenactment, using illegal workers to play an illegal entry into the United States.

WILLIE

78′ / 1985 / EUA Sala 1 domingo Sunday ás 16:30 h

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon Son: Nancy Weiss Lyon, Ed Hugetz, Jack Foley, Doug Kuntz Produción, fotografía e montaxe: Danny Lyon Asistente de montaxe: Nancy Weiss Lyon Producida coas subvencións de The New Mexico Arts Commission, The Santa Fe Council for the Arts, The Southwest Alternate Media Project, The National Endowment for the Arts

Lyon entra nas prisións e comisarías onde Willie ou os seus amigos de infancia cumpriron condena, observando e entrevistando a Willie e aos seus irmáns, aos seus compañeiros de prisión, aos alcaides e a calquera no seu círculo de coñecidos, coma se nalgún lugar existise unha pista que explicase os problemas interminables que lle perseguen sen compaixón e que parecen apoderarse da súa sorte. Lyon enters the prisons and precincts where Willie Jaramillo or his childhood friends have served time, observing and interviewing him, his brothers, his fellow inmates, wardens, and anyone else in his circle of acquaintance, as if there might be a clue somewhere to the trouble that seems to endlessly and ruthlessly seek Willie out and take a hold of his fate.

SNCC

74′ / 2020 / EUA Sala 2 xoves Thursday ás 19:30 h Utilizando centos de fotogramas inéditos filmados no Sur profundo dos Estados Unidos no apoxeo do Movemento polos dereitos civís, Lyon recrea unha das organizacións estudantís máis exitosas da historia, a SNCC (Comité Coordinador Estudantil Non Violento), a punta de lanza que puxo de xeonllos a Jim Crow. Using hundreds of unknown 35 mm stills Lyon shot in the deep south at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, he recreates one of the most successful student organizations in history, the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) the point of the spear in bringing Jim Crow to its knees.

Estrea internacional / International Premiere

Unha película de Danny Lyon