A Yokogawa Company

A Yokogawa Company

A Yokogawa Company

A Yokogawa Company

KBC’s Profit Improvement Program and implement untapped opportunities to boost refinery margins - fast.

KBC’s Profit Improvement Program® helps refiners identify and implement untapped opportunities to boost refinery margins - fast.

For over 40 years KBC has implemented 150+ Profit Improvement Programs, focusing on both non-investment quick wins for an immediate margin improvement and long-term strategic initiatives that maximize ROI. Using proven simulation tools like Petro-SIM® and Visual MESA®, best practices and deep industry expertise, we help you reduce energy use and emissions, increase high-value products, reduce crude costs, optimize your supply chain and enhance asset availability and utilization. Achieve measurable, sustainable results and boost your bottom line with a Profit Improvement Program.

For over 40 years KBC has implemented 150+ Profit Improvement Programs, focusing on both non-investment quick wins for an immediate margin improvement and long-term strategic initiatives that maximize ROI. Using proven simulation tools like Petro-SIM® and Visual MESA®, best practices and deep industry expertise, we help you reduce energy use and emissions, increase high-value products, reduce crude costs, optimize your supply chain and enhance asset availability and utilization. Achieve measurable, sustainable results and boost your bottom line with a Profit Improvement Program.

Discover how KBC turns opportunity into profit www.kbc.global/pip

Discover how KBC turns opportunity into profit www.kbc.global/pip

08

Miro Cavkov, Euro Petroleum Consultants (EPC), Bulgaria, explores how carbon capture, utilisation, and storage technology can be used by refiners as a tool for decarbonisation, by preserving and reusing the carbon molecule.

13

The journey toward low-carbon competitiveness is a marathon of discipline, not a sprint of innovation. Sanjay Bhargava and Michelle Wicmandy, KBC (A Yokogawa Company), consider how refinery profit improvement programmes (PIPs) can substantially increase margins and sustain real-time performance.

Cody Falcon, ABB Energy Industries, considers how industrial operations are evolving from traditional automation to autonomous systems that can adapt, learn, and operate with minimal human intervention.

21 Improvement through collaboration

Yoshito Sato, Yokogawa, details the collaboration between Shell and Yokogawa in machine vision and robotics.

31

Aadam F. Aryan, Distillation Equipment Company Ltd, UK, discusses the necessary process and mechanical considerations for successfully revamping distillation columns to improve efficiency.

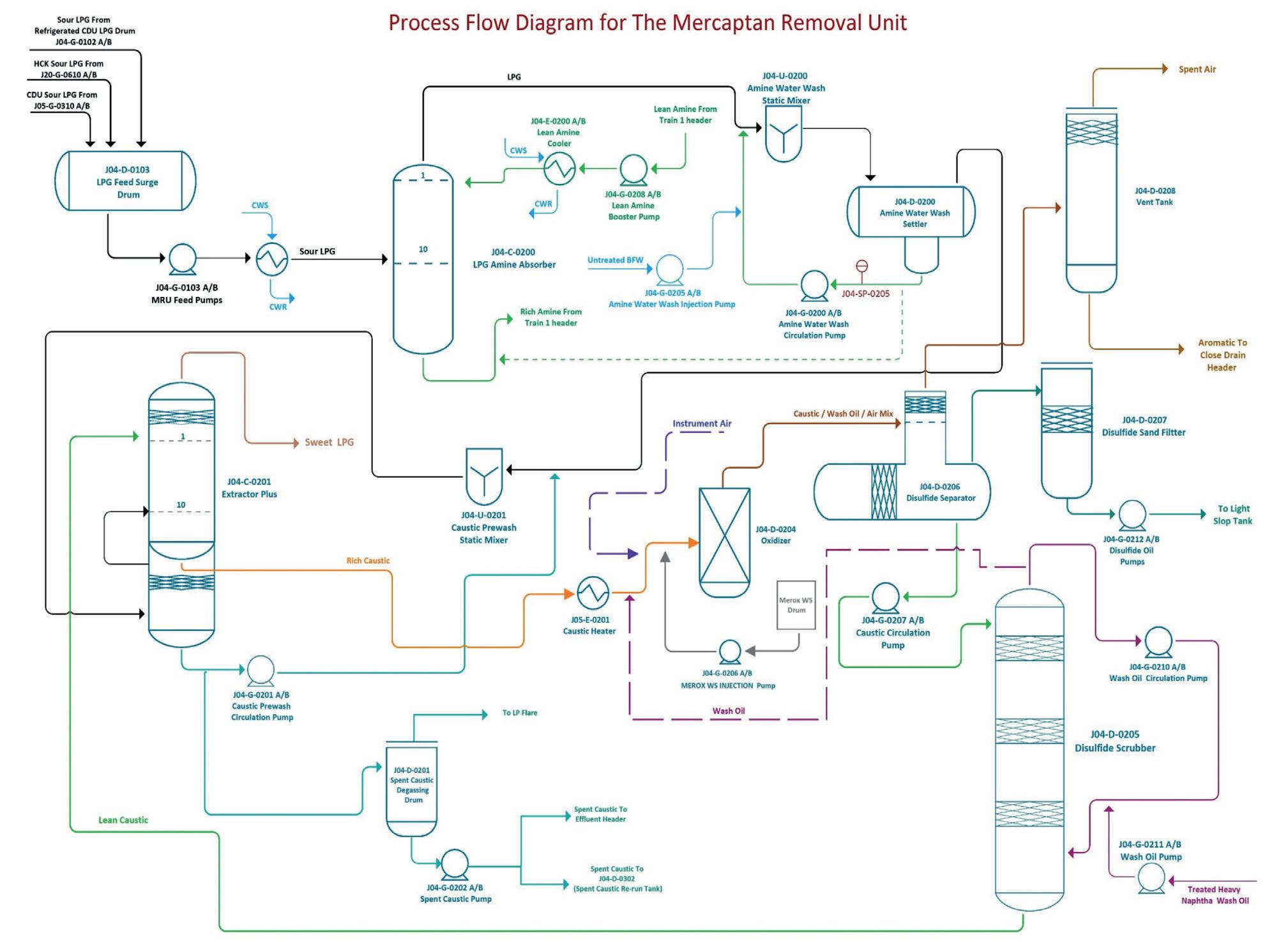

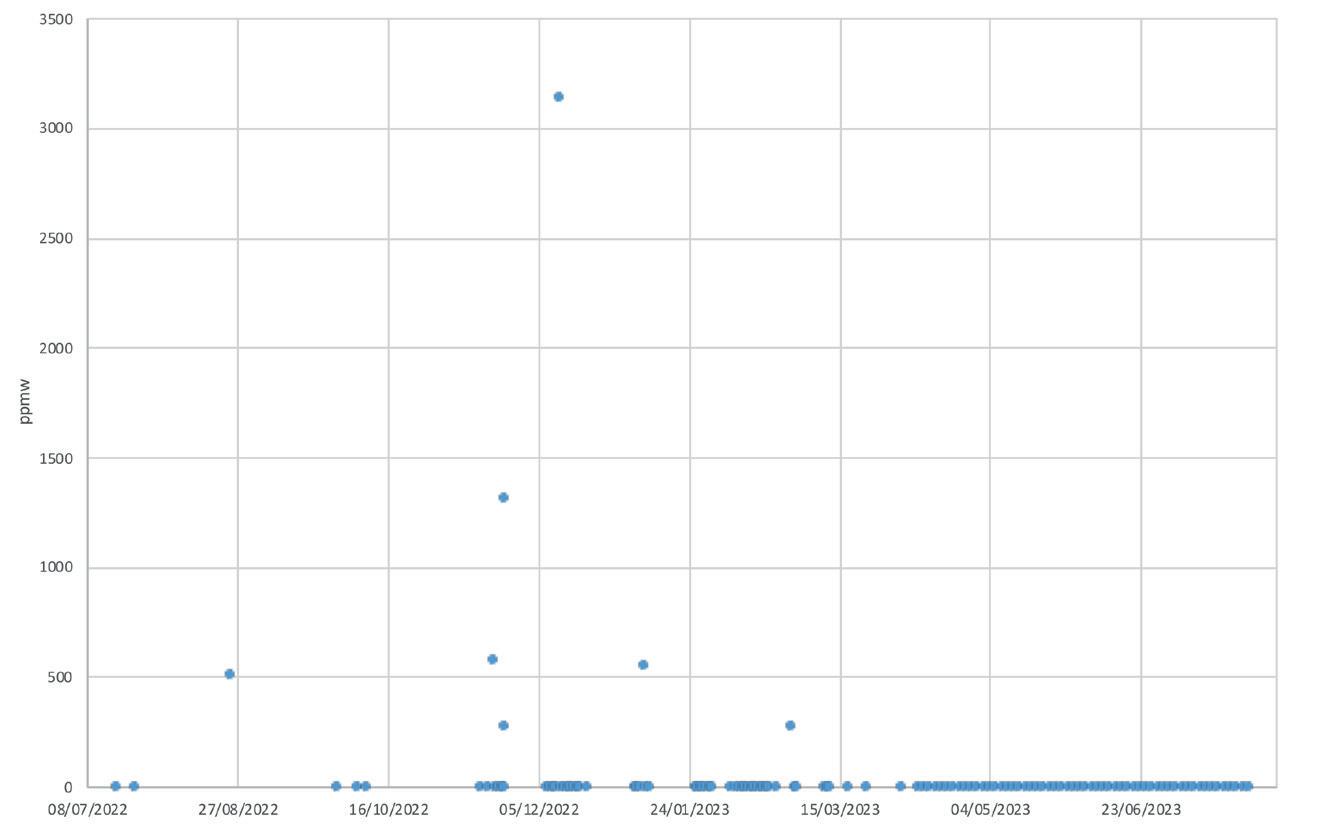

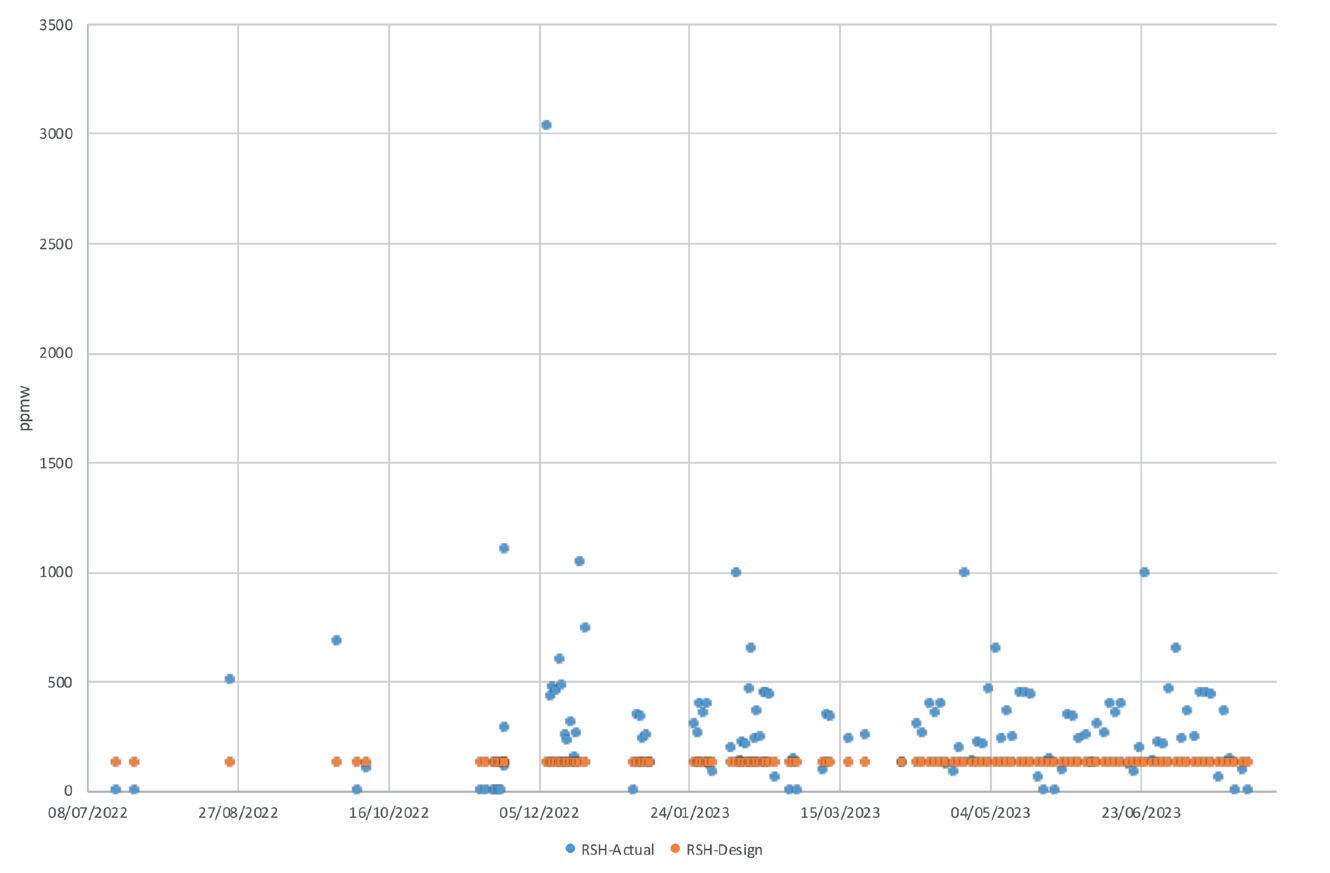

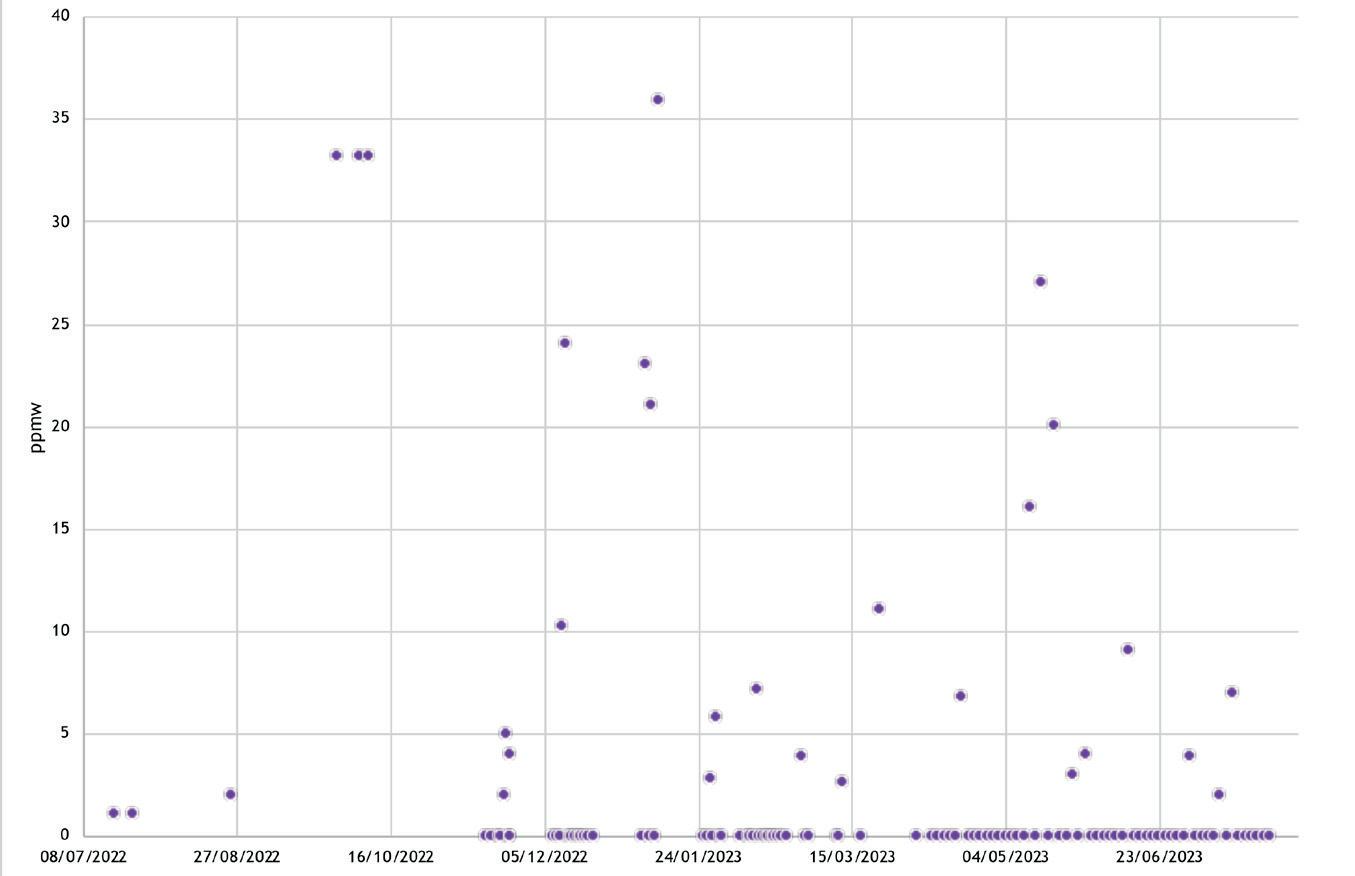

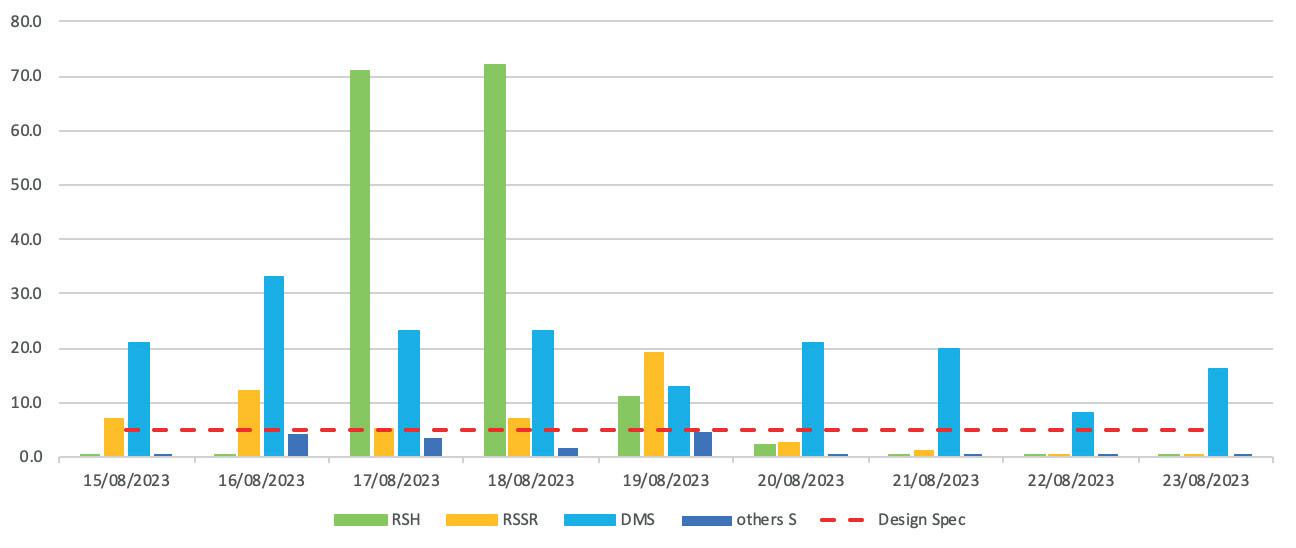

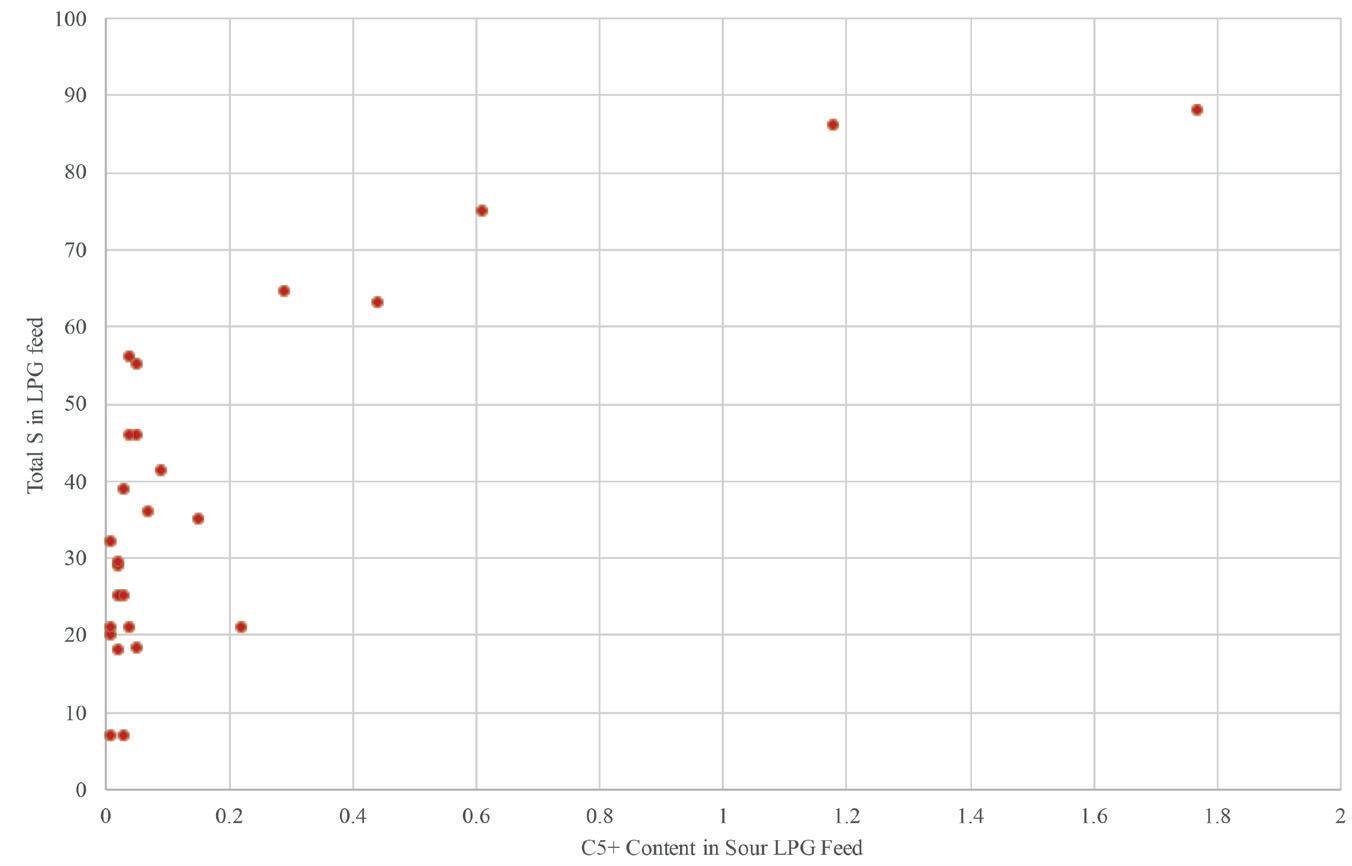

Muhammad R. Tariq and Taib B. Abang, Saudi Aramco, discuss LPG mercaptan sweetening technologies and present their findings.

36

Bert Klussmann, Sulzer, USA, considers developments in heat technology that can improve heater efficiencies alongside reducing emissions.

Al Geraskin, Integrated Global Services (IGS), Czech Republic, examines challenges facing steam cracker performance, and provides solutions that can maximise olefin production and ensure sustainability.

Hani Taan, NanoTech Materials Inc., USA, examines the properties and applications of spray-applied coatings that can protect industrial tank and piping systems from corrosion under insulation and safeguard personnel throughout operations.

Fadi Bachir, Owens Corning, outlines key factors to consider when designing an insulating system that defends against corrosion under insulation, while supporting the longevity of equipment used in hydrocarbon processing applications.

Distillation Equipment Company Ltd (DtEC) is a UK chemical engineering company, established in 1998, specialising in the design, manufacture, and supply of mass transfer equipment. With decades of experience in trays, packings, internals, and mist eliminators, whatever type and material, the company’s mission is to improve the performance of distillation and absorption columns.

Cut your CO2 emissions by 50% with the future of carbon black production

Compliant and innovative

Meets stringent environmental regulations, keeping your business future-ready

Unparalleled flexibility

Produce all ASTM grades and specialty grades seamlessly in a single plant

Sustainable Uses thermal decomposition of aromatic oils for cleaner production

MANAGING EDITOR James Little james.little@palladianpublications.com

SENIOR EDITOR Callum O'Reilly callum.oreilly@palladianpublications.com

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Ellie Brosnan ellie.brosnan@palladianpublications.com

SALES DIRECTOR Rod Hardy rod.hardy@palladianpublications.com

SALES MANAGER Chris Atkin chris.atkin@palladianpublications.com

SALES EXECUTIVE Ella Hopwood ella.hopwood@palladianpublications.com

PRODUCTION MANAGER Kyla Waller kyla.waller@palladianpublications.com

HEAD OF EVENTS Louise Cameron louise.cameron@palladianpublications.com

DIGITAL EVENTS COORDINATOR Merili Jurivete merili.jurivete@palladianpublications.com

DIGITAL CONTENT COORDINATOR Kristian Ilasko kristian.ilasko@palladianpublications.com

DIGITAL ADMINISTRATOR Nicole Harman-Smith nicole.harman-smith@palladianpublications.com

JUNIOR VIDEO ASSISTANT Amélie Meury-Cashman amelie.meury-cashman@palladianpublications.com

EVENTS COORDINATOR Chloe Lelliott chloe.lelliott@palladianpublications.com

ADMIN MANAGER Laura White laura.white@palladianpublications.com

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Nancy Yamaguchi Gordon Cope

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Annual subscription £110 UK including postage/£125 overseas (postage airmail). Two year discounted rate £176 UK including postage/£200 overseas (postage airmail).

SUBSCRIPTION CLAIMS

Claims for non receipt of issues must be made within 3 months of publication of the issue or they will not be honoured without charge.

APPLICABLE ONLY TO USA & CANADA

Hydrocarbon Engineering (ISSN No: 1468-9340, USPS No: 020-998) is published monthly by Palladian Publications Ltd GBR and distributed in the USA by Asendia USA, 701C Ashland Avenue, Folcroft, PA 19032. Periodicals postage paid at Philadelphia, PA & additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: send address changes to HYDROCARBON ENGINEERING, 701C Ashland Ave, Folcroft PA 19032.

CALLUM O'REILLY

SENIOR EDITOR

This year’s Nobel Peace Prize captured more headlines than usual – largely because of President Donald Trump’s high-profile campaigning to secure the award. Ultimately, the prize was awarded to María Corina Machado, the Venezuelan opposition leader, for her “tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela”. While Trump’s very public ambitions to win the Peace Prize dominated media coverage, the winners of one of the other Nobel Prize categories caught my attention. Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the development of a new type of molecular architecture: metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

These molecular constructions have large cavities through which gases and other chemicals can flow. By varying the building blocks used in the MOFs, chemists can design them to capture and store specific substances, and MOFs can also drive chemical reactions or conduct electricity.

The origins of MOFs started in 1989, when Richard Robson initially tested utilising the inherent properties of atoms in a new way. He combined positively charged copper ions with a four-armed molecule, and this had a chemical group that was attracted to copper ions at the end of each arm. When combined, they bonded to form a spacious crystal that was like a diamond with innumerable cavities. However, this constriction was unstable and collapsed easily. Susumu Kitagawa and Omar Yaghi then made a series of revolutionary discoveries. Kitagawa showed that gases can flow in and out of the constructions and predicted that MOFs could be made flexible. Yaghi then created a very stable MOF and showed that it can be modified using rational design, giving it new and desirable properties.

Since these discoveries, chemists have built tens of thousands of different MOFs which can be used in lots of different applications, e.g. to harvest water from desert air, separate PFAS from water, and break down traces of pharmaceuticals in the environment. MOFs can also be used to catalyse chemical reactions, capture carbon dioxide, and store hydrogen and toxic gases.

Given this rapid revolution, it is no surprise that MOFs are now making their way into industrial decarbonisation strategies. Indeed, regular readers of Hydrocarbon Engineering may recall that our November 2025 issue featured an article exploring how one MOF in particular – TAMOF-1 – is emerging as a practical, scalable solution for CO2 capture in real-world downstream applications.1 You can read the article now by logging into your account over at our website or by signing up to a free subscription to the magazine (www.hydrocarbonengineering.com/magazine).

15 South Street, Farnham, Surrey

GU9 7QU, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 1252 718 999

As the momentum behind MOF research continues to build, these materials are poised to play an increasingly important role in shaping the industry’s path toward lower emissions and greater efficiency. Future editions of Hydrocarbon Engineering are sure to feature even more insights into the growing potential of MOFs. In the meantime, this issue kicks off with an article from Euro Petroleum Consultants (EPC) looking at how CCUS is emerging as one of the defining technologies of the energy transition.

We’d like to thank all our readers and advertisers for their continued support throughout 2025, and wish you all a joyful and restful holiday season.

1. GALÁN-MASCARÓS, J. R., GIANCOLA, S., CAPELO-AVILÉS, S., and VILA-FONTES, M., ‘High performing carbon capture by TAMOF-1’, Hydrocarbon Engineering, (November 2025), pp. 40 - 44.

A Mechanical Integrity Solution With A 360-Degree View of Your Risks, Assets, & Costs To Elevate Your Outcomes

• Comprehensive API-580/581 RBI, API-970 CCD, and API-584 IOW compliant methodologies to determine risk and set inspection priority

• Improved data accuracy and efficiency to support smarter, faster decision-making at the point of work

TA’ZIZ has announced the award of a US$1.99 billion engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contract to China National Chemical Engineering & Construction Corp. Seven Ltd (CC7), to build the UAE’s first, and among the world’s largest, integrated single-site polyvinyl chloride (PVC) production complexes.

The contract, announced at ADIPEC, marks a major step forward in delivering TA’ZIZ’s strategic mandate to drive industrial growth,

localise supply chains, and enable new value chains in the UAE.

Located within the TA’ZIZ industrial ecosystem in Ruwais, the facility will produce 1.9 million tpy of marketable PVC, ethylene dichloride (EDC), vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), and caustic soda. These chemicals are critical to serving growing demand in sectors such as construction, infrastructure, packaging, and healthcare, in the UAE and internationally. The project is expected to be completed by 4Q28.

Enbridge Inc. has announced that it has reached a final investment decision (FID) on the Mainline Optimization Phase 1 project (MLO1). MLO1 will add capacity to the company’s Mainline network and Flanagan South Pipeline (FSP) to meet customer demand for incremental egress, increasing deliveries of Canadian heavy oil to key refining markets in the US Midwest (PADD II) and Gulf Coast (PADD III).

“MLO1 is expected to add capital-efficient and timely egress capacity from Canada, supporting Canadian production and increasing connectivity to the best refining markets in North America,” said Colin Gruending, Enbridge’s Executive Vice President and President of Liquids Pipelines. “This project demonstrates the advantage of leveraging existing networks to meet growing customer demand, supporting energy security and affordability across North America.”

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Compressor International Corp. (MCO-I) has been awarded a contract by ExxonMobil to supply a footprint replacement steam turbine for its olefins plant in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, US.

Personnel from MCO-I and its parent company, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Compressor Corp. (MCO), will collaborate on the project with both teams supporting the manufacturing, testing, commissioning, and installation of the turbine. During the project, virtual assembly will be provided during the manufacturing stage and throughout the installation stage to support an efficient turnaround and help maintain continuity in plant operations.

A key technology, virtual assembly, will be used during manufacturing and installation to support an efficient turnaround and maintain plant continuity. This innovative approach involves creating a precise digital model of the components before they arrive on-site. By pre-assembling the parts in a virtual environment, the team can identify and resolve potential fit issues ahead of time, ensuring a smooth and rapid installation.

Bharat Petroleum Corp. Ltd (BPCL) and Oil India (OIL) are set to build an integrated greenfield refinery and petrochemical plant in Ramayapatnam, India, with an estimated investment of IR1 lakh crore (US$11 billion).

BPCL has signed three landmark memoranda of understandings (MoUs) with OIL, Numaligarh Refinery Ltd (NRL), and Fertilisers & Chemicals Travancore Ltd (FACT).

These partnerships mark significant milestones in BPCL’s integrated growth

strategy – spanning refining, petrochemicals, green energy, and logistics infrastructure – and reaffirm its commitment to building a sustainable and self-reliant energy future for India.

BPCL and OIL have signed a non-binding MoU to explore collaboration in developing BPCL’s upcoming greenfield refinery and petrochemical complex near Ramayapatnam Port in Nellore district, Andhra Pradesh, India. The proposed

facility, with a refining capacity of 9 - 12 million tpy, will be a cornerstone of India’s downstream expansion.

Under the MoU, the companies will evaluate opportunities for collaboration, including the possibility of OIL taking a minority equity stake in the proposed joint venture.

The project has already secured key statutory clearances and 6000 acres of land from the government of Andhra Pradesh, with pre-project activities in progress.

02 - 05 February 2026

21st International Conference & Exhibition on Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG2026) Doha, Qatar www.lng2026.com

10 - 12 February 2026

NARTC Houston, Texas, USA worldrefiningassociation.com/event-events/nartc

17 - 20 February 2026

Laurance Reid Gas Conditioning Conference Norman, Oklahoma, USA www.ou.edu/pacs/lrgcc

24 - 26 February 2026

ESF Europe: Energy & Sustainability Forum Antwerp, Belgium https://europetro.com/esfeurope

15 - 17 March 2026

AFPM Annual Meeting New Orleans, Louisiana, USA www.afpm.org/events

15 - 19 March 2026

AMPP Annual Conference + Expo Houston, Texas, USA ace.ampp.org

29 - 31 March 2026

AFPM International Petrochemical Conference San Antonio, Texas, USA www.afpm.org/events

28 - 30 April 2026

Sulphur World Symposium Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada www.sulphurinstitute.org/symposium-2026/

19 - 21 May 2026

Asia Turbomachinery & Pump Symposium Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia atps.tamu.edu

09 - 11 June 2026

Asia Turbomachinery & Pump Symposium Calgary, Alberta, Canada www.globalenergyshow.com

Pengerang Biorefinery Sdn. Bhd., a joint venture (JV) between Petronas, Enilive S.p.A, and Euglena Co. Ltd, marked a milestone with the groundbreaking ceremony for the development of the new biorefinery in Pengerang, Johor, Malaysia.

The biorefinery will have the processing capacity of up to 650 000 tpy of renewable feedstock

and is projected to produce sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO), and bio-naphtha. Feedstocks for the biorefinery will include wastes such as used vegetable oils and animal fats, and residues from the processing of vegetable oils. The new facility is targeted to commence operations by 2H28 in line with the schedule.

OMV, Austria’s integrated energy, fuels, and chemicals company, and Masdar, a global clean energy leader, have signed a binding agreement to establish a joint venture (JV) for the financing, construction, and operation of the 140 MW green hydrogen electrolyser plant in Bruck an der Leitha, Austria.

This landmark project will be one of Europe’s largest green hydrogen production facilities and marks a major step in OMV’s commitment to decarbonising its Schwechat refinery

and accelerating the energy transformation. Construction of the facility began in September 2025 and it is expected to be operational in 2027.

The JV between OMV and Masdar will be majority-owned by OMV with Masdar owning 49%. The partnership combines OMV’s strategic leadership under its integrated fuels and chemicals business and Masdar’s commercial, financial, and technical expertise in developing and operating clean energy projects worldwide.

Aether Fuels and Aster have signed an agreement to develop the first next-generation, commercial-scale SAF production facility in Southeast Asia at Aster Pulau Bukom in Singapore. Project Beacon, Aether’s commercial demonstration facility, will utilise the company’s AuroraTM technology to produce up to 50 bpd of fuel (2000 tpy of fuel). It will convert industrial waste gas and biomethane into CORSIA-certified SAF, achieving a reduction of more than 70% in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions compared to conventional

jet fuel, making it the first commercial facility of its kind. Project Beacon is expected to commence construction in 2026 and begin commercial operations in 2028.

Locating the plant on Pulau Bukom underscores Aster’s commitment to fostering breakthrough innovation within its asset ecosystem. Aster will provide renewable power, waste carbon feedstock, utilities, and site support to accelerate the development and commercialisation of Aether’s scalable solution.

By adopting advanced distillation technologies, you can significantly reduce energy consumption, enhance product quality, and improve overall process reliability. These innovations help you meet environmental targets while unlocking potential subsidies and lowering operational costs.

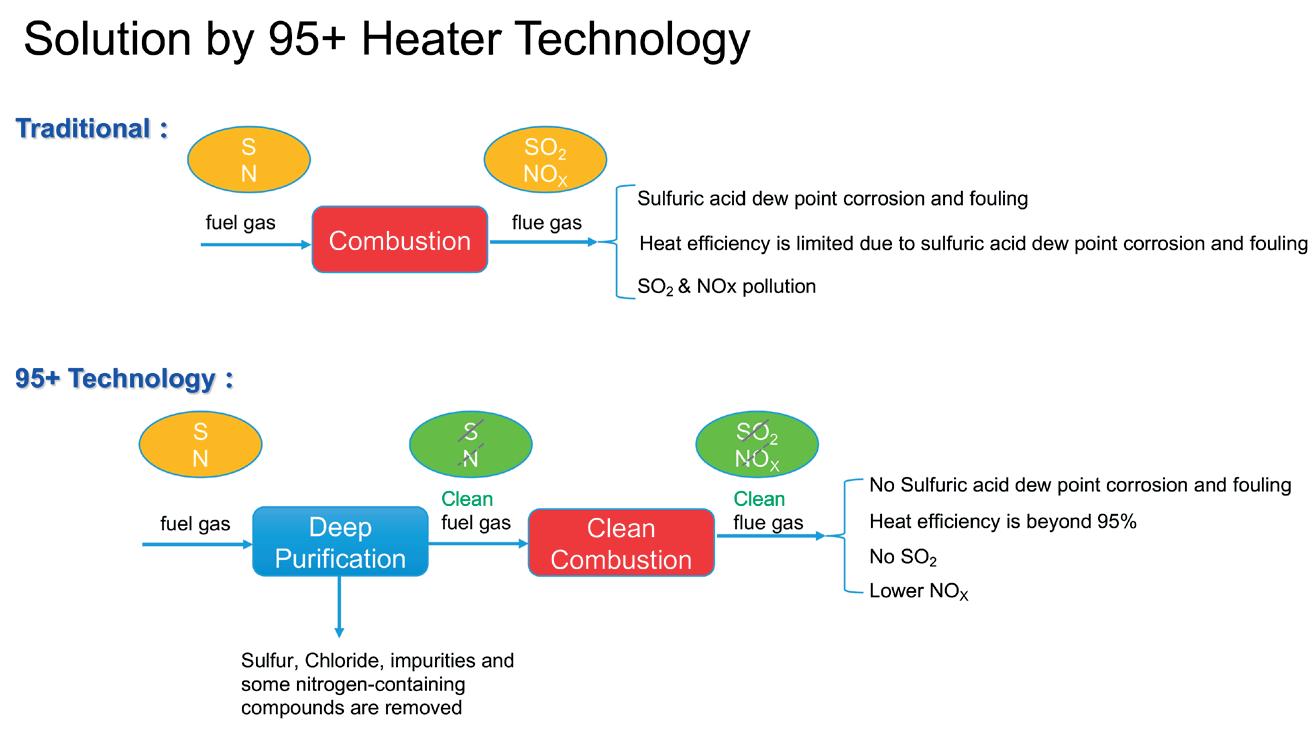

Our energy optimization strategies include advanced distillation design, thermal coupling, heat integration, and cutting-edge electrification technologies. Solutions like Divided Wall Column reduce energy consumption by more than 30%, VoltaSplit™ offer electrified distillation with up to 10× lower CO2 emissions, while Sulzer 95+ Heater Tech delivers ≥95% efficiency with minimal maintenance and fast ROI. Sulzer provide the tools to transform your plant into a model of sustainable performance.

Contact us for more information chemtech@sulzer.com

Miro Cavkov, Euro Petroleum Consultants (EPC), Bulgaria, explores how carbon capture, utilisation, and storage technology can be used by refiners as a tool for decarbonisation, by preserving and reusing the carbon molecule.

As the race to net zero accelerates, carbon capture, utilisation, and storage (CCUS) is emerging as one of the defining technologies of the energy transition. Beyond simply cutting emissions, CCUS offers a way to preserve and reuse the carbon molecule by turning a waste product into a valuable resource and forming an essential pillar of a circular, lower-carbon economy.

Achieving net zero emissions by 2050 will require ambitious mitigation actions, and large scale deployment of CCUS technologies is among the most critical. The focus is shifting from concept to implementation, with energy and industrial players deploying carbon capture systems to lower the carbon intensity of existing downstream assets while building new business models around third-party emitters.

Worldwide, CCUS projects are gaining momentum from large scale hubs in Europe and North America to emerging initiatives in Asia and the Middle East. Each represents a step towards integrating carbon management into mainstream industrial operations. Yet the challenge remains immense: industries such as refining, chemicals, and power generation still account for a significant share of global CO2 emissions.

Meeting this challenge will depend on a combination of technological innovation, strong policy frameworks, and cross-sector collaboration. For many, CCUS is no longer a distant option but a practical pathway to decarbonisation and a key enabler of the sustainable industrial ecosystem needed for the decades ahead.

CCUS is rapidly becoming one of the most critical technologies in the global effort to achieve net zero. At its core, the concept is simple: capture CO2 before it reaches the atmosphere, and either reusing it to create valuable products or storing it safely and permanently underground in depleted oilfields. The execution, however, demands sophisticated infrastructure, strong policy frameworks, and cross-sector collaboration to bring it to scale.

In practical terms, CCUS encompasses three key stages. First, CO2 is captured directly from industrial operations such as refineries, petrochemical complexes, and power plants or even removed from the air through direct air capture systems. Next, the captured carbon can be utilised as a feedstock to produce fuels, chemicals, polymers, and building materials, embedding it back into industrial value chains rather than allowing it to contribute to global warming. Alternatively, the CO2 can be stored deep underground, injected thousands of feet beneath the surface into carefully selected geological formations such as depleted oil and gas reservoirs or saline aquifers, where it remains securely trapped for the long-term.

Far from a theoretical solution, CCUS has a proven safety record. The large scale injection and storage of CO2 has been practised for decades, particularly in enhanced oil recovery (EOR) operations, where captured CO2 is injected into oilfields to boost recovery rates while simultaneously storing the gas underground. The safety of these operations hinges on robust standards and decades of geological and engineering expertise.

When it comes to transportation, CO2 is an inert, non-flammable gas. It can be safely moved in smaller quantities by trucks as seen in everyday uses like carbonated beverages or in much larger volumes through dedicated pipeline networks. For storage, the selection of sites is meticulous. Engineers target stable rock formations more than half a mile underground, typically sealed by an impermeable cap rock that prevents the gas from migrating back to the surface.

Beyond storage, utilisation opens up new economic and environmental opportunities. Captured carbon can serve as a building block for a range of sustainable materials, ranging from synthetic fuels and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) to chemicals, polymers, and construction materials. In doing so, CCUS not only mitigates emissions but also supports a circular carbon economy, where CO2 becomes a resource rather than a liability.

This dual role, as both a decarbonisation tool and a value-creation mechanism, makes CCUS uniquely important to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement. By lowering the carbon intensity of hard-to-abate sectors such as refining, petrochemicals, and heavy manufacturing, CCUS bridges the gap between today’s industrial infrastructure and the low-carbon systems of the future. Ultimately, the challenge now is one of scale and speed. The technology exists and has been proven to work safely and effectively, while currently the task ahead lies in expanding deployment through collaborative frameworks between industries, governments, and technology providers. As the world moves from climate pledges to practical action, CCUS stands out as one of the most tangible pathways to balance industrial progress with environmental responsibility.

The downstream refining sector sits at the crossroads of the energy transition, simultaneously as one of the largest

industrial emitters and as a crucial enabler of cleaner fuels and feedstocks. CCUS technologies are now reshaping how refiners approach decarbonisation, offering a realistic pathway to lower emissions while protecting the value of existing assets.

For decades, refineries have relied on steam methane reforming (SMR) to produce hydrogen, a key component in hydroprocessing, desulfurisation, and numerous hydrogen addition downstream reactions. Traditionally, this process emits significant amounts of CO2, resulting in what is commonly known as grey hydrogen. However, integrating carbon capture into SMR units transforms this process into blue hydrogen production, a major leap forward in emissions reduction. By capturing and storing CO2 generated during hydrogen production, refiners can produce lower-carbon hydrogen while continuing to leverage existing infrastructure.

This shift does not just merely reduce emissions, but it extends the lifespan of CAPEX-heavy process units such as reformers, crackers, and auxiliary pre-heat trains, allowing them to continue operating at optimal efficiency while meeting tightening regulatory and environmental requirements. For operators, the value is twofold: maintaining reliability in their core operations and simultaneously positioning their assets for a carbon-constrained future.

Beyond hydrogen, CCUS offers downstream producers an opportunity to turn captured carbon into new business value. When combined with renewable hydrogen, captured CO 2 becomes a versatile feedstock for creating specifically designed synthetic hydrocarbons varying from SAF and clean transportation fuels to chemicals, packaging materials, and even construction inputs. These carbon-to-value pathways are gaining traction, especially as alcohol(ethanol)-to-jet (ATJ) and methanol-to-jet technologies advance.

Methanol, for instance, can be synthesised via the Fischer-Tropsch process, where carbon and hydrogen react over a catalyst to produce liquid hydrocarbons. Once methanol is produced, refiners can leverage a well-established set of downstream conversion routes to create renewable fuels and sustainable chemicals. This integration not only creates circular carbon loops but also enables refiners to diversify their product portfolios in alignment with new sustainability mandates.

Regulation is a powerful driver of this transformation. Across Europe and beyond, SAF mandates are rising sharply, requiring an increasing share of aviation fuel to come from low-carbon or carbon-neutral sources. These mandates, coupled with corporate net zero commitments, are rapidly creating a market for high-quality carbon utilisation and offsets. Companies that once viewed CO2 purely as a waste stream are now recognising it as a valuable raw material, which will be one of the cornerstones of the future low-carbon product strategies.

The financial world is reinforcing this momentum. The growing weight of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions have made emissions performance a key determinant of corporate competitiveness. Investors are increasingly

Long days in the lab, late nights in the limelight. From sample analysis to pressure drop prevention, our tech service team is the science behind the show. Microscopes. Metrics. Mullets (optional). That’s the Crystaphase Experience.

rewarding companies that adopt technologies like CCUS, which demonstrate measurable, science-based pathways to decarbonisation. For refiners, the message is clear: innovation in emissions management is no longer optional, but rather a serious prerequisite for capital access, brand resilience, and long-term viability.

Carbon capture is not just a technology investment, it becomes a licence to operate in the energy system of tomorrow.

Ultimately, CCUS in refining and petrochemicals is not about replacing the sector’s foundation but reinventing it. By coupling existing process efficiency with digitalisation, hydrogen integration, and circular carbon utilisation, the downstream industry is building the bridge between today’s fossil-based operations and a net zero future. The molecules may remain the same, but the way they are produced, captured, and reused is being fundamentally transformed.

As carbon management technologies move from concept to commercial deployment, one truth has become increasingly clear: scaling CCUS will require more than adopting technology innovation, it will demand broader coordination, higher capital investment, and conviction. Despite remarkable progress in capture efficiency and integration with refining processes, cost, scalability, and regulatory clarity remain the largest barriers to mass adoption.

Globally, the scale of the challenge is immense. To reach net zero emissions by 2050, the world will need to remove up to 10 billion tpy of CO2, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). No credible pathway to net zero exists without large scale carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies, so within that portfolio, direct air capture (DAC) and carbon capture from industrial sources are poised to play central roles.

However, cost remains the critical bottleneck. Today, the end-to-end expense of capturing and permanently storing a ton of CO2 through DAC ranges between US$600 - 1000/t, depending on the region, which is far above what most industrial emitters or investors can absorb. To reach commercial viability, these costs must fall below US$200/t, and ideally closer to US$100/t, by 2050. The race to achieve that cost curve compression will determine whether CCUS becomes a mainstream industrial solution or remains confined to isolated demonstration projects.

This is not unprecedented. Solar energy costs have fallen by more than 90% over the past four decades, and similar economies of scale and innovation cycles could accelerate CCUS cost reductions. To make that happen, industry leaders argue that governments, technology providers, and refiners must work in lockstep to build the commercial and regulatory frameworks that give investors the confidence to act.

For refining, the challenge is particularly complex but also full of opportunity. Integration of CCUS within modern refinery clusters where multiple emitters can share capture, transport, and storage infrastructure offers

one of the most cost-effective routes forward. In Europe, for instance, projects are exploring regional CO2 networks that connect hydrogen reformers, power plants, and petrochemical sites to shared storage basins in the North Sea. This hub-and-spoke model allows refiners to reduce costs through shared infrastructure while creating a clear investment case for scaling up capture capacity.

Financial mechanisms are also evolving. The rise of carbon trading systems such as the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) has created a liquid market for carbon allowances, allowing refiners and industrial players to hedge against future carbon price increases or monetise captured CO2 through verified offset credits. These market-based tools, alongside carbon contracts for difference (CCfDs) and targeted tax incentives, can play a decisive role in closing the cost gap between emitting and capturing carbon.

Yet technology alone cannot deliver success. Regulatory coordination and standardisation are equally vital. Risks can stall investments where carbon storage, accounting, and crediting rules differ across borders. Industry stakeholders are calling for clear, long-term policy signals, transparent carbon accounting standards, and cross-border recognition of carbon credits to ensure consistent market dynamics.

Beyond economics and policy, the human and technological partnerships needed for CCUS success are equally critical. No single entity, whether a refiner, technology provider, or government can deliver large scale CCUS alone. Refiners bring operational experience and infrastructure, technology firms provide capture, compression, and digital monitoring solutions, while policymakers and investors supply the frameworks and financing that make these ventures possible. Only collaborative ecosystems, not isolated efforts, can turn CCUS from an engineering ambition into a functioning pillar of industrial decarbonisation.

Meanwhile, digitalisation and data transparency are emerging as powerful enablers. Advanced process simulation, digital twins, and predictive analytics are helping operators design and optimise capture units, track CO2 flows in real time, and verify emissions reductions with precision. This digital backbone builds trust in performance data, which is a crucial factor for investors and regulators, and can accelerate scaling by ensuring projects are both verifiable and financially auditable.

Ultimately, the pathway ahead hinges on a mix of technology maturity, market liquidity, and global alignment. Reducing CCUS costs to below US$150/t of CO2 will be a formidable challenge, but not an impossible one. It will require massive investment, international collaboration, and bold policy frameworks to catalyse the industrial demand and economies of scale that can drive prices down.

As the refining sector stands on the front line of industrial transformation, it is uniquely positioned to lead this charge. By embedding CCUS into existing refining, chemicals, hydrogen, power, and process networks, refiners can transform one of the world’s most carbon-intensive industries into a cornerstone of climate progress.

The journey toward low-carbon competitiveness is a marathon of discipline, not a sprint of innovation. Sanjay Bhargava and Michelle Wicmandy, KBC (A Yokogawa Company), consider how refinery profit improvement programmes (PIPs) can substantially increase margins and sustain real-time performance.

Refining today sits at the crossroads of market volatility and structural transformation. Margins have slipped back to pre-pandemic levels, with refining earnings down by approximately 50% in 2024 compared with 2023 and roughly 60% lower than in 2022. Over the next decade, refining capacity is projected to decline by up to 30% depending on region.1

Beneath those numbers lies a deeper shift. Refiners are being asked to do more with less – to run cleaner, leaner, and smarter – without the luxury of large capital expansions. The challenge is not merely economic; it is structural, operational, and human, all at once.

Operators are now expected to maximise margins with minimum CAPEX while facing a web of operational constraints. These include increasingly complex feedstocks, lower energy intensity, stricter emission obligations, and shifting product-demand patterns tied to mobility, biofuels, and the circular-economy. One empirical study found that refinery complexity, specific-energy consumption, and distillate yield

positively correlated with gross refining margin, while fuel and loss factors had negative impacts.2

For decades, the default response was to build bigger. Today, expansion alone is no longer the answer. Leadership now hinges on disciplined operational excellence – the art of extracting more value from the same assets. Increasingly, refiners are turning to structured improvement frameworks, known as profit improvement programmes (PIPs). These programmes systematically identify, quantify, and implement operational, process, and refinery-wide improvements to generate value with minimal incremental capital.

PIPs focus on enhancing yield, reducing energy use and emissions, minimising crude costs, strengthening reliability, optimising turnarounds, and building human-performance capability. They emphasise a phased, cross-functional approach: baseline definition, opportunity discovery, modelling and prioritisation, rapid implementation of quick wins, and a comprehensive sustainment programme.

Running parallel to this methodological rigour is a wave of digital transformation to sustain implemented opportunities and transform a PIP into a continuous improvement programme. Advances in digital-twin modelling, high-fidelity simulation, and advanced analytics are transforming operations. Model-based AI-driven hybrid optimisation ensures real-time performance by tightening the link between operations, planning, and maintenance. Recent research in refining operations with digital twins reports average return on investment timelines of 12 - 36 months, efficiency gains of 15 - 42%, and maintenance cost reductions of 25 - 55%.3

What began as a series of isolated improvement projects has evolved into a strategic performance-management discipline –one that connects margin recovery, operational resilience, and decarbonisation readiness into a unified agenda.

Refining margins have always been a balancing act between efficiency and volatility, but the fulcrum has grown narrower. Industry benchmarking suggests that incremental inefficiencies in energy use, yield, and reliability may quietly erode a few percent of total operating expenditure – equivalent to millions of dollars of lost value annually. While market crack spreads largely dictate external margin swings, operational inefficiencies within the refinery often represent the most addressable source of lost value.4 Closing that gap through systematic improvement has become essential.

Across the industry, benchmarking shows that structured improvement programmes can reverse this silent leakage.

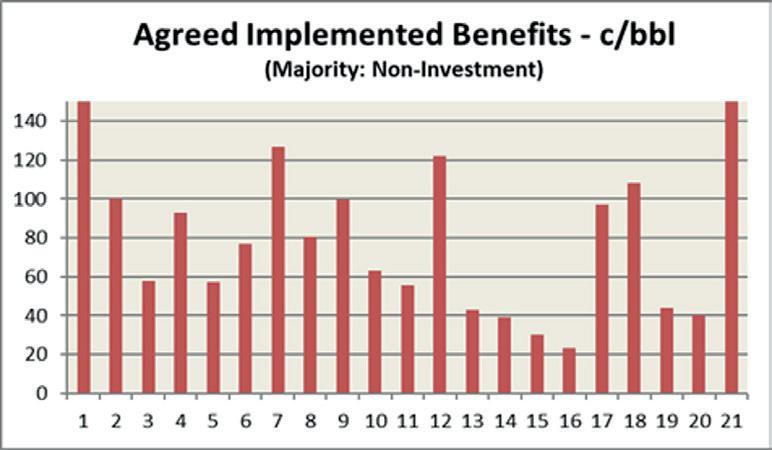

Typical implementations yield between US$30 and US$60 million in annual benefits, with payback achieved in under 12 months and internal rates of return often exceed 100%. The outcomes are tangible: 5 - 15% reductions in specific energy consumption, 2 - 5% higher availability, and measurable improvements in crude costs, process yields, reliability, and emissions intensity. These results suggest that the next competitive advantage will not come from scale, but from acting on the big-impact-creating prioritised quick-win projects that collectively define refinery performance.

The traditional PIP has evolved from a one-time operational review into a continuous, digitally enabled performance-management system. At the heart of this transition is the ability to merge engineering models, plant data, and human decision-making into a unified improvement framework. The digital AI/ML layer enables refiners to quantify, implement, and sustain performance gains across yield, energy, reliability, and emissions metrics more effectively than ever before.

Digital profit improvement programmes (D-PIPs) typically follow a five-stage methodology – define, discover, develop, deliver, and sustain – linking opportunity identification with execution and continuous improvement, as shown in Figure 1. This agile, sprint-based approach accelerates benefit realisation while embedding digital capability across the organisation.

The shift is not purely technological. PIPs are increasingly designed to deliver dual dividends: economic performance and environmental progress. Many refiners track carbon reduction directly alongside margin improvement, with potential benefits ranging from US¢35 - 70/bbl in margin uplift and US¢5 - 15/bbl in energy and emissions reduction. This dual-focus approach aligns profitability with sustainability, a defining characteristic of the sector’s new performance model.

By combining advanced analytics with empowered teams, refiners can move from reactive troubleshooting to proactive optimisation. Across implemented programmes, typical results show 40 - 80% of total benefits from yield improvements, 5 - 40% of total benefits from yield improvements from capacity utilisation gains, and 5 - 8% of total benefits from energy cost reduction (up to 15% with capital enhancements). Supply-chain alignment

commonly delivers a further 5 - 20% improvement in value realisation.

The result is not only sustained profitability but also improved reliability, energy performance, and emissions management – key metrics for competitiveness in a decarbonising market. The evolution toward digital PIPs positions refiners to achieve higher margins while building the operational resilience required for a low-carbon economy.

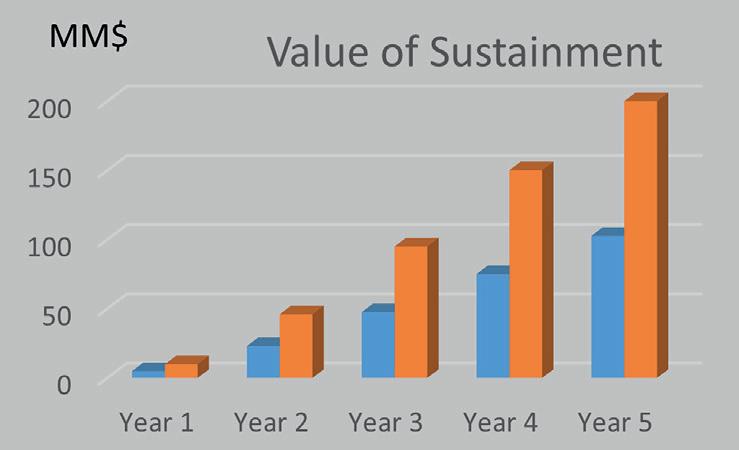

Industry-wide benchmarking shows typical improvement distribution and value-sustainment behaviour across domains, as shown in Figure 2.

A large refinery embarked on a modernisation initiative that combined structured performance improvement with digital transformation. The approach, which is now becoming common across the industry, aimed to enhance profitability, reliability, and energy performance while advancing low-carbon operations. This example demonstrates how a structured improvement framework, supported by digital tools, can deliver parallel gains in financial and sustainability outcomes.

The site launched a full-scale transformation that brought together digital tools, operational-excellence practices, and sustainability. The initiative integrated advanced process-simulation, control, and optimisation technologies to enable higher profitability and energy efficiency while reducing emissions.

With its digital backbone in place, leadership advanced toward data-driven, semi-autonomous decision-making.

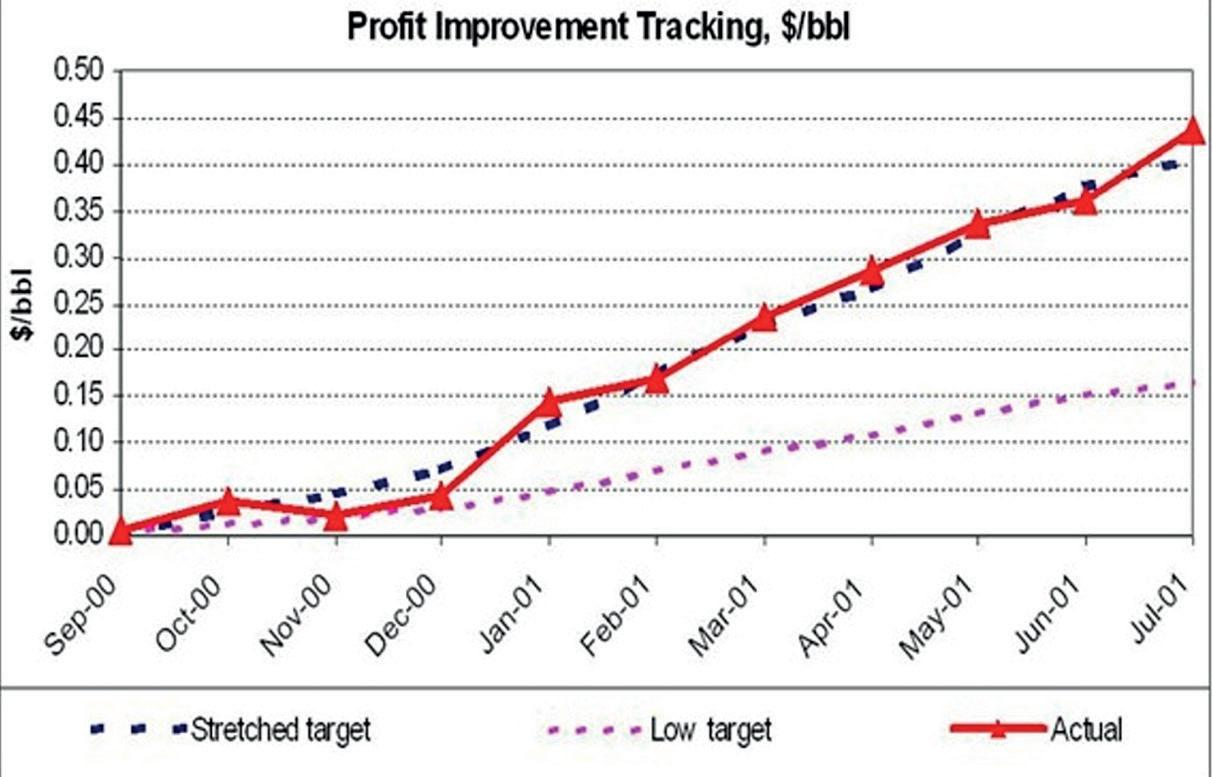

The refiner combined first-principles simulation software, upgraded advanced process control (APC) systems, and real-time optimisation dashboards to shift from reactive responses to predictive operations, as shown in Figure 3.

A multi-period utility-plant optimiser reduced energy use while increasing profits, and automating a compressor-control strategy eliminated chronic hydrogen flaring, closing a gap in both emissions and margin.

Operational planning also evolved. Linear programming models were overhauled and backcasting introduced to bridge the gap between planned and actual performance. Improved crude selection increased profits by US$30 million/yr in additional profit.

Through more than 25 targeted process improvements, the team enhanced yields and reliability while lowering energy intensity. Focused upgrades in crude separation, catalyst use, and stream routing lifted middle-distillate yields by 6.5 vol%. Refined catalyst and constraint management reduced lower-value fuel-oil production in favour of higher-value distillates, generating US$100 million in incremental profit.

Energy efficiency became a defining metric of progress. Early benchmarking revealed substantial opportunity and, within months, overall energy performance improved by about 10% through low- or no-CAPEX measures. Continued optimisation – pinch analysis, energy real-time optimisation, heat-exchanger monitoring, and multi-period optimisation – pushed performance into sustained double-digit improvements.

Hunter modular solutions help you meet sustainability standards and bottom-line goals in one build. With reduced material waste, shorter project timelines and lower lifetime energy use, our steel structures offer lasting value — protecting your people, your investment and the environment.

Figure 3. Real-time optimisation dashboard supports predictive operations and KPI tracking.

Figure 4. Profit-tracking dashboard showing how digital monitoring aligns operational actions with realised and sustained value.

Structured turnaround reviews and a dedicated gatekeeper avoided over US$8 million in unnecessary work.

Reliability-centred maintenance (RCM) and root cause analysis (RCA) programmes reduced an estimated US$30 - 45 million in production losses, increasing mechanical availability and safety performance.

Modernisation also aligned with broader regional investments in renewable-fuel capacity, including hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) production, reinforcing the link between refinery optimisation and future clean-fuel infrastructure. The results were as follows:

n US$150 million in validated annualised benefits across process, energy, reliability, and supply-chain performance.

n 6.5 vol% increase in middle-distillate yield.

n >10% energy efficiency improvement driven by low-CAPEX solutions.

n Over US$30 million/yr in potential profits via PIMS LP upgrades.

n Downtime reduction through RCA and RCM, and lower maintenance costs via gatekeeper controls.

This case demonstrates that operational performance and decarbonisation are complementary forces.

Technology initiates change, but sustained value depends on a workforce able to interpret data, act, and adapt. Industry

experience shows that up to 70% of potential value can be lost without proper sustainment and organisational alignment.

Human-performance improvement remains central to sustaining results. Continuous coaching, competency development, and structured problem-solving ensure that improvements achieved through digital tools are retained through disciplined execution. Leading operators embed structured work processes, digital dashboards, and capability-development programmes that reinforce accountability and knowledge transfer.

Digital tools such as model-based profit tracking systems now provide a live view of realised and sustained value, capturing every opportunity from identification through execution, as shown in Figure 4. They monitor progress, track benefit leakage, and maintain alignment between operational actions and financial outcomes.

Continuous-improvement mechanisms – supported by near-real-time performance tracking – help ensure that gains remain visible and measurable. Training programmes focused on operational awareness, problem-solving, and energy stewardship cultivate a performance culture that adapts to new digital tools rather than resists them. Over time, this integration of technology and human capability transforms short-term profit-improvement projects into ongoing strategic disciplines.

Field experience shows that properly executed PIPs can yield implemented profits of 5 - 10 times programme cost, generating internal rates of return exceeding 100%. Cumulative benefits of US$100 - 200 million are achievable in large, integrated sites when quick wins and minor investments are fully realised.

As the refining sector adapts to a more complex and carbon-constrained environment, PIPs have become both a business necessity and a sustainability enabler. The same model-based data-driven frameworks that uncover process inefficiencies also identify opportunities to cut energy use and lower emissions. They improve asset utilisation while accelerating the speed to margin.

Digital technologies – ranging from process simulation and optimisation to AI-enabled analytics – extend the impact of these programmes by making improvement measurable, repeatable, and scalable. Coupled with strong organisational alignment and workforce capability, they transform short-term efficiency projects into a culture of continuous improvement and a bridge to sustainable competitiveness.

The journey toward low-carbon competitiveness is not a sprint of innovation but a marathon of discipline. Digital tools illuminate the path ahead, but it is human expertise – the judgement, creativity, and operational rigour of people – that keeps progress steady.

References

1. DE MUR, A., FOLLETTE, C., GOYDAN, P., HOOD, R., and MCMILLAN, G., ‘Costs and margins dictate the future for refiners’, Boston Consulting Group (BCG), (1 April 2025).

2. JAFARI, H.R.S., ‘Report: refining margins: refinery margin systems (RMS)’, (January 2009).

3. MAHESHWARI, R.K., ‘digital twins and financial ROI: assessing tech investments in refinery operations’, Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management, pp. 826 - 838, (September 2025).

4. SHOKOUHI, M.R., KHADEMVATANI, A., and BEIKY, F., ‘Analyzing economic and financial risk factors affecting profitability of oil refinery investment projects: a case study from an Iranian oil refinery’, Energy Strategy Reviews, Vol. 52, (March 2024).

Cody Falcon, ABB Energy Industries, considers how industrial operations are evolving from traditional automation to autonomous systems that can adapt, learn, and operate with minimal human intervention.

Industrial operations are undergoing changes not seen since distributed control systems transformed the industry in the 1970s. Facilities are transitioning from rule-based automation to intelligent and adaptive systems capable of handling unexpected situations, learning from operational history, and functioning with reduced direct human oversight. This evolution addresses challenges that have reached a critical point across heavy industry.

The people that built and operate most complex facilities are leaving the workforce faster than the industry can replace their expertise. Meanwhile, the data these facilities generate has increased to a point beyond human capacity to process effectively.

Where an operator might have monitored 500 sensors 15 years ago, today’s plants can generate input from over 500 000 data points.

Processing this volume of information in real-time while making operational decisions within seconds has become impossible for human operators alone.

The barrier to implementation has shifted over the past decade. Eight years ago, the industry questioned whether the technology was ready. That debate has been settled. Now the challenge is not whether the systems work, but how much operators can trust them to make critical decisions.

Experienced operators, with decades of expertise, can approach these systems with scepticism. They have

built careers on institutional knowledge and an intuitive understanding of plant behaviour. Deferring critical decisions to software naturally creates resistance.

Consistent performance changes perspectives. When these systems repeatedly recommend correct actions, identify potential issues before they become problems, and provide troubleshooting guidance that works, that scepticism gives way to acceptance. Within six months, operators are often asking why the system is presenting recommendations rather than simply implementing them automatically. This progression from resistance to advocacy reflects the trust-building process essential for autonomous operations.

Traditional control systems excel at maintaining setpoints and responding to deviations that can be programmatically defined, but they cannot synthesise complex patterns across thousands of variables, external sources, and data types to predict future states or identify subtle indicators that precede significant problems.

Energy management is a great example. Modern industrial and downstream facilities, such as refineries and petrochemical complexes, now source power from multiple inputs: grid electricity, on-site generation, solar and wind, and battery storage to ensure a stable and reliable power supply. Optimising this selection requires real-time analysis of weather forecasts, grid pricing that changes every few minutes, predicted facility loads,

and equipment availability. A human operator might manage this decision-making for one or two sources, but the computational requirements for multiple sources with constantly changing variables exceed human processing capability.

Energy management optimisation technology handles this automatically, enabling facilities to respond to market pricing changes in real-time, shift to renewable sources when available, and maintain cost optimisation while maintaining production targets, all without dedicated personnel monitoring inputs and manually making the operational adjustments. In downstream operations, similar optimisation is increasingly applied to energy and utilities management. Integrated management systems at a refinery, for instance, can automatically balance power generation, ensuring continuous optimisation of both cost and carbon intensity.

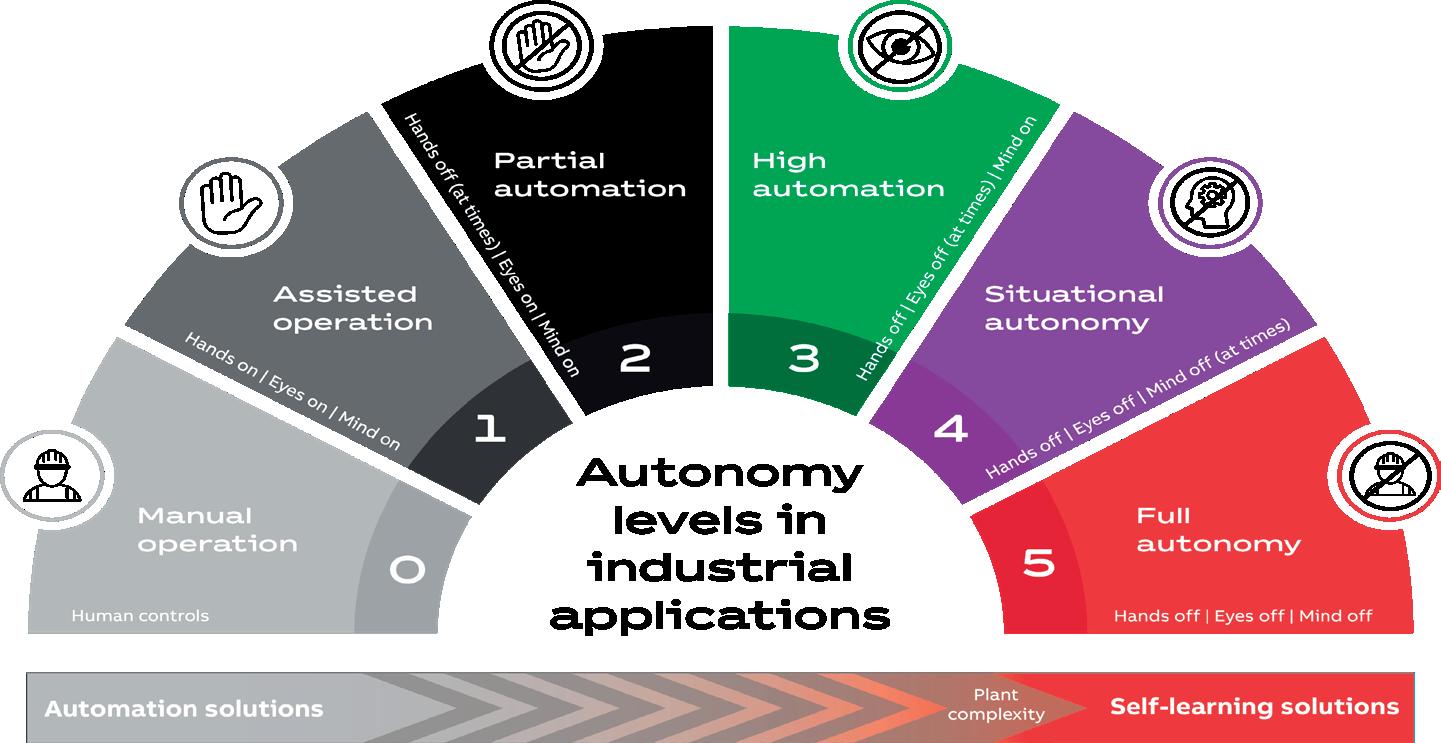

The progression toward full autonomy follows a structured framework that helps assess where facilities currently operate and plan advancement strategies. This six-level approach progresses from manual operations (Level 0) through various automation stages to full autonomy (Level 5), where systems can handle all anticipated and unanticipated situations without human intervention.

Most energy facilities currently operate between Levels 2 and 3. At Level 2, basic automation handles routine processes, but humans remain responsible for setting parameters and responding to anything outside normal operations. Level 3 introduces more sophisticated control systems that can manage complex processes and alert operators to issues but still requires human decision-making for abnormal situations.

The transition to Level 4 represents the most significant operational change. Here, the technology begins demonstrating situational autonomy – the ability to recognise and respond to conditions not explicitly programmed during system design. This requires incorporating learning capabilities that can identify patterns from historical data and apply successful strategies to new but similar situations.

State-based control (SBC) illustrates how these capabilities translate into operational benefits. Traditional automation systems require manual reconfiguration when process conditions

change. For example, automatically adjusting distillation column controls as a refinery unit transitions between start up, steady state, and shut down; or managing process trains within a petrochemical cracking unit as feedstock composition changes. Contrast these examples to the traditional approach that relies on an operator’s manual control adjustments during changing conditions.

SBC can recognise these state changes automatically and implement all necessary adjustments without human intervention. The system recognises and adapts to the shifts. When market conditions, operating environment, asset availability, or production targets shift, the entire adjustment process that previously required hours of skilled operator time occurs in minutes.

Anomaly detection represents another significant advancement within process control. Rather than simply alerting operators when variables exceed preset limits, systems such as ABB AbilityTM PlantInsight continuously monitor plant behaviour against learned patterns of normal operation. When subtle deviations appear, often hours or days before they would trigger traditional alarms, the system can identify potential root causes by comparing current conditions with historical events. The technology has evolved over the last decade to reduce the investigative burden on the operator with explainability in context and recommendations for resolution.

This capability proves particularly valuable during shift transitions or when less experienced operators are on duty. Instead of relying solely on individual expertise, every operator has access to institutional knowledge captured from decades of operations across all sites. When abnormal situations arise, systems can identify similar historical events and recommend proven solutions, effectively providing every operator with the guidance of the most experienced personnel, even when they are not physically present.

Such capability dramatically improves response times. Where operators previously might spend 30 minutes researching solutions to complex problems, these systems can provide proven recommendations in 30 seconds, enabling faster resolution of critical situations.

The relationship between autonomous technology and plant personnel represents evolution rather than replacement. Operators consistently report that automation of routine tasks allows them to focus on higher-value activities: process optimisation, strategic planning, and complex problem-solving that requires human judgement and creativity.

This shift addresses the skills shortage facing

A podcast series for professionals in the downstream refining, petrochemical, and gas processing industries

Sponsored by

EPISODE 14

Rob Benedict, Vice President, Petrochemicals and Midstream, American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), discusses the outcomes of the final round of UN negotiations for a Global Plastics Treaty.

EPISODE 15

David Wilson, CEO, Energy Exemplar, considers the role that oil and gas is currently playing in the booming data centre industry, and what the future holds.

EPISODE 16

Andrea Bombardi, Executive Vice President, RINA, offers technical and operational insight into some of the key challenges and opportunities of CCUS implementation.

EPISODE 17

Alec Cusick, Owens Corning Technical Lead, Technical Insulation, talks about the risks of LNG pool fires and methodologies to mitigate these risks.

industrial operations. As experienced operators retire, they take irreplaceable knowledge with them. Traditional training programmes can transfer procedural knowledge but struggle to capture the intuitive understanding that develops over decades of doing the job. Autonomous systems provide a mechanism for institutionalising this experience in software that remains available regardless of personnel changes.

The most successful implementations involve collaborative development where experienced operators work directly with system designers to capture decision-making patterns. This process benefits both parties: operators see their expertise valued and preserved, while systems gain access to knowledge that would otherwise be lost.

Industrial applications often operate in unforgiving environments where errors can have significant consequences. This high-risk reality demands different approaches to system design, testing, and implementation compared to consumer applications.

Industrial systems require fail-safe mechanisms, comprehensive override capabilities, and integration with existing safety systems. The testing and validation processes extend over years rather than months, and deployment occurs in carefully planned phases that maintain operational continuity.

These requirements explain why many industrial customers prioritise vendors with operational experience over technology startups. While startups may offer innovative algorithms or user interfaces, industrial facilities need partners who understand the operational context, regulatory requirements, and risk management strategies essential for safe implementation.

The business case for autonomous operations extends far beyond theoretical benefits to measurable operational improvements. Facilities implementing comprehensive optimisation systems typically report positive improvements in process and reductions in lifecycle cost.

Safety performance improvements prove equally significant. Autonomous systems reduce human exposure to hazardous environments, eliminate human error during critical operations, and provide consistent response to emergencies regardless of operator experience level or shift timing.

The operational efficiency gains compound over time as systems accumulate experience. These systems maintain consistent performance 24 hours per day, continuously optimising operations based on current conditions and learned patterns.

Refineries and petrochemical plants increasingly demonstrate the practical application of these technologies. For example, in refinery operations these advances in control systems have enabled the continuous optimisation of hydrocracking and distillation units, reducing unplanned downtime and improving energy efficiency.

Similarly, in petrochemical complexes, automated shutdown and start up sequences have significantly reduced manual interventions, enhanced safety, and delivered more consistent product quality.

Comparable benefits have also been achieved in offshore environments where platforms that once required hundreds of personnel can now operate with one-button start-up procedures.

In the short-term future, agent-based operations will likely become standard across industrial operations. Rather than simply providing recommendations that require human approval, systems will independently execute complex operational strategies while maintaining appropriate human oversight.

Code generation represents a particularly significant development. Current projects require two to three years for engineering and commissioning. Systems trained on millions of lines of proven control logic could generate facility-specific automation code in a fraction of the time, dramatically accelerating project timelines while maintaining proven operational patterns.

The infrastructure requirements for these advances are already emerging. Cloud, edge, and hybrid architectures enable real-time processing of massive data volumes while maintaining the security and reliability standards essential for industrial operations. Industrial cybersecurity standards and frameworks continue evolving to address the unique challenges of operating in critical infrastructure environments.

Successful implementation requires a realistic assessment of current capabilities and systematic progression towards higher autonomy levels. A facility with basic process control might achieve significant benefits from implementing advanced process control before considering more sophisticated systems. For downstream operators, phased implementation has proven particularly valuable. For example, integrating advanced analytics into existing distributed control systems within refineries can result in improvements without major system overhauls. Conversely, facilities already operating with sophisticated automation systems can progress to integrated analytics and augmented operations on the path toward autonomous operations.

This approach preserves existing investments while providing clear advancement pathways. Rather than requiring wholesale system replacement, modern architectures allow integration of advanced capabilities with existing distributed control systems, enabling phased implementation that maintains operational continuity.

Autonomous operations address industry performance challenges around productivity, safety, reliability, and quality. Success requires intelligent augmentation of human capabilities with systems that capture, preserve, and apply decades of operational expertise.

Companies leading this transition focus on meeting customers at their current automation maturity and providing clear paths toward higher autonomy levels. As trust builds through demonstrated performance, facilities move towards complex industrial processes that operate safely and efficiently with minimal human intervention.

These developments are happening now in facilities worldwide. The question for individual operations is how quickly they will adapt to realise these benefits before the competitive gap becomes difficult to close.

Yoshito Sato, Yokogawa, details the collaboration between Shell and Yokogawa in machine vision and robotics.

As the oil and gas industry continues to pursue operational excellence, safety, and sustainability, digital innovation has become a critical enabler for transformation. Within the downstream sector, leading companies are increasingly turning to intelligent automation, machine vision, and data-driven insights to improve efficiency, reduce operational risk, and meet environmental goals.

A prominent example of this shift is a strategic collaboration between Shell and Yokogawa. Shell has developed an advanced machine vision tool based on extensive experience in integrity management, remote inspections, and corrosion monitoring. Yokogawa is now integrating this capability into its platform with

the aim of making it available to industrial facilities globally in the future. As deployments expand, insights from real operating environments will inform the joint evolution of machine vision capabilities, enabling continuous improvement through collaboration. This cycle supports safer, more efficient, and more reliable operations across the global energy and manufacturing industries, contributing to the advancement of industrial operations worldwide.

This article explores the essence of this collaboration, the technology and vision behind Operator Round by Exception (ORE), and the broader implications for the downstream oil and gas sector.

Downstream facilities operate under complex, tightly regulated environments. Plant operators are responsible for performing regular rounds, visually inspecting gauges, valves, pumps, pipelines, and other equipment to ensure optimal and safe functioning. Traditionally, these inspections have been labour-intensive, prone to human error, and limited in their frequency and accuracy.

As energy markets face growing pressure to reduce emissions, improve energy efficiency, and maintain high safety standards, plant operators require more than incremental improvements. They need transformation. Digital innovation – particularly in the form of robotics, sensor networks, and AI-powered analytics – is enabling a shift from reactive to predictive operations.

Within this landscape, the collaboration between Shell and Yokogawa exemplifies how a legacy industry can adopt transformative technologies without compromising its core operational reliability.

The inefficiency of routine manual inspections is a key bottleneck in plant management. Traditionally, operators follow predetermined routes and checklists regardless of actual equipment status. This often leads to unnecessary work and delayed detection of abnormal conditions.

The ORE solution developed by Shell and integrated by Yokogawa addresses this problem. Using autonomous robots equipped with cameras and sensors, the system continuously monitors field assets. Images, thermal signatures, and audio cues are analysed in real time using AI-powered machine vision algorithms. These algorithms can detect deviations such as analogue gauge drift, valve misalignment, leakage, or unusual sounds, triggering alerts and providing contextual data to the control room.

This approach shifts operator activity from scheduled rounds to exception-based interventions. When no anomalies are detected, operators are not dispatched. When an issue is identified, ORE delivers actionable insight with supporting imagery and diagnostics, allowing targeted and timely responses.

The solution converges several technology layers:

ORE uses sophisticated image recognition models trained on vast datasets of plant imagery. These models can detect subtle visual changes that indicate abnormal operating conditions. For example, AI can quantify analogue gauge readings, recognise corrosion patterns, or detect liquid pooling near pumps. By integrating deep learning and supervised training, the system improves over time – adapting to lighting conditions, environmental variables, and asset ageing.

Autonomous mobile platforms – either wheeled or legged –serve as carriers for the sensors. These robots are capable of navigating complex industrial terrain, avoiding obstacles, and reaching equipment that may be hazardous or inaccessible to human workers.

While the current scope does not include a broad deployment of a robotic fleet, the system architecture is designed to be modular and adaptable to various robotic platforms in the future.

Data collected from field inspections are streamed to a centralised platform where it is processed, visualised, and acted upon. Edge computing is leveraged to handle real-time detection, reducing latency, while cloud systems enable scalable data storage and long-term analytics.

This infrastructure ensures that the insights generated by ORE are integrated into plant information systems, work management platforms, and digital twins.

By automating the normal and flagging the abnormal, the solution enables plants to operate with leaner staffing and faster incident response. This is particularly valuable for high-throughput, 24/7 facilities where early detection of failure modes can prevent costly shutdowns.

Digital innovations, such as the one addressed in this article, can yield tangible benefits across multiple dimensions: n Safety: reducing the need for humans in potentially hazardous areas lowers risk exposure and supports safer operations.

n Efficiency: operators can focus their expertise on addressing real problems, rather than spending time on routine checks.

A special supplement focusing on decarbonisation pathways for the downstream sector, highlighting innovative technology and solutions that will help you thrive within the energy transition.

This special supplement focuses on decarbonisation pathways for the downstream sector, highlighting innovative technology and solutions that will help you thrive within the energy transition.

Scan the QR code to download your free copy of EnviroTech 2025.

Scan the QR code to download your free copy of EnviroTech 2024.

n Asset reliability: early anomaly detection allows for predictive maintenance, reducing unplanned downtime and extending equipment life.

n Data-driven decision making: continuous visual inspection builds a historical record, which can be used to improve asset strategies and training programmes.

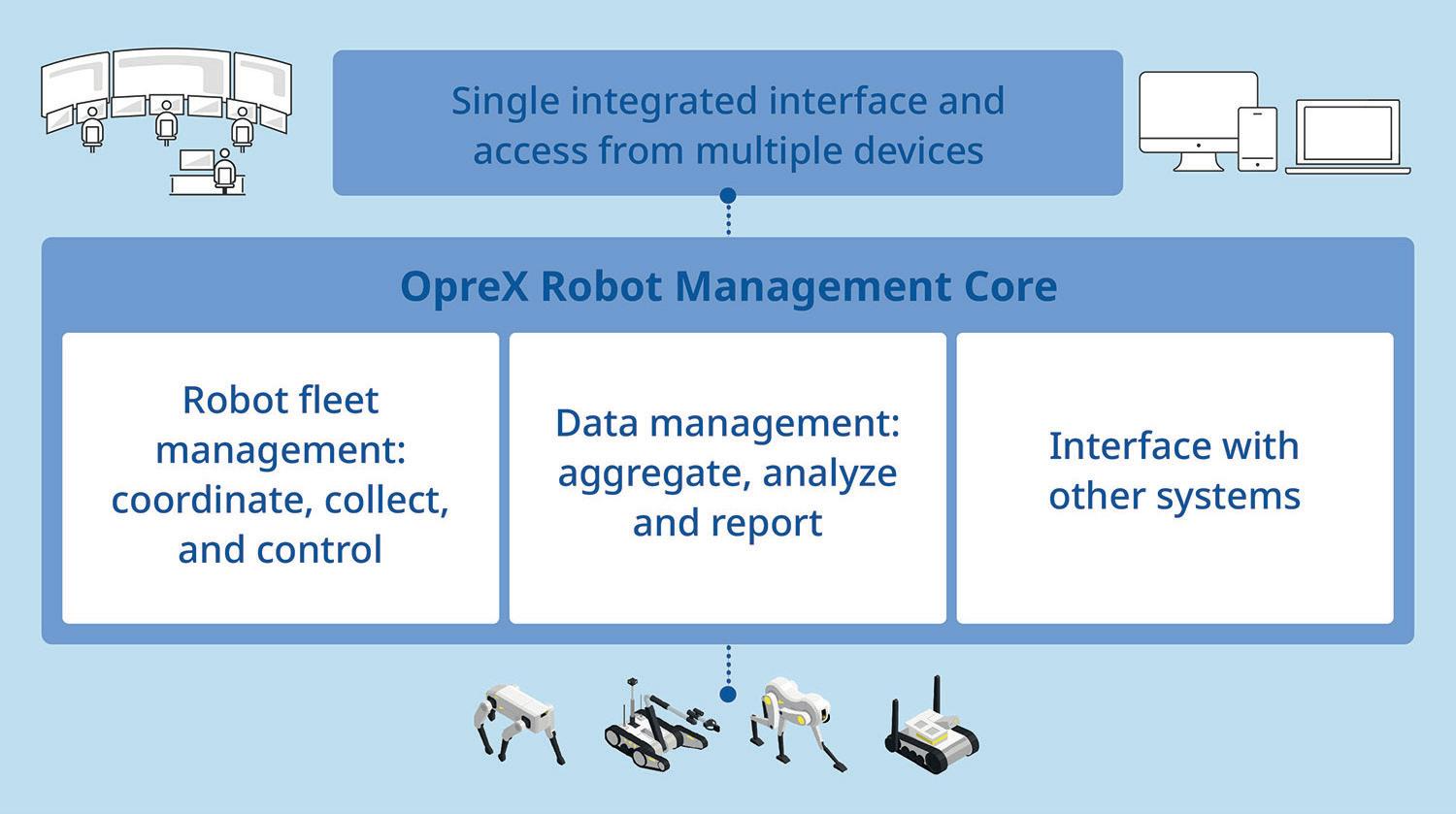

One of the critical considerations in the collaboration between Shell and Yokogawa is scalability. The design of the ORE system takes into account the diversity of downstream operations across different geographies and regulatory environments. To that end, Yokogawa has worked to develop standardised templates, deployment processes, and support structures that can be applied across multiple sites. This includes integration with Yokogawa’s OpreXTM Robot Management Core (RMC) and other digital platforms, ensuring that data from ORE can flow into plant systems without custom engineering for every deployment. Such an approach lowers the total cost of ownership and accelerates return on investment.

From the journey so far, several lessons have emerged that are applicable to the broader downstream industry:

n Start with operational use cases: technology should follow the problem, not the other way around.

n Balance standardisation with flexibility: standard templates and architectures are essential for scale, but solutions must

also adapt to local conditions and evolving customer needs.

n Organisational change is as important as technology: training, mindset shift, and cross-functional collaboration are critical for adoption.

n Cloud and AI are enablers – not solutions by themselves: the real value comes from how data is used, not just how it is collected.

Looking ahead, Yokogawa aims to further enhance the intelligence and autonomy of the ORE system, potentially incorporating more advanced diagnostics, multi-modal sensing, and tighter integration with plant control systems. Shell continues to support this journey by contributing real-world operational expertise, governance structures, and a vision for digital transformation.

The collaboration outlined in this article reflects a broader shift in how industrial operations address increasing regulatory pressure, ageing assets, market volatility, and workforce constraints. In this environment, earlier anomaly detection, remote inspection, and smarter deployment of human expertise are essential. Such collaborations, including a joint R&D roadmap for the future, help to enable safer, more efficient, and cost-effective autonomous monitoring and maintenance.

Aadam F. Aryan, Distillation Equipment Company Ltd, UK, discusses the necessary process and mechanical considerations for successfully revamping distillation columns to improve efficiency.

Although distillation is energy intensive, it is still the most widely used separation method, and will remain so for many years. To reduce our carbon footprint, it is incumbent upon all engineers involved in the refining and chemical process industries to optimise the design of such columns. The performance of any distillation column can be improved with respect to capacity, separation efficiency, pressure drop, energy efficiency, fouling tendency, and mechanical integrity.

Ultimately the key consideration is cost vs benefits of the improvement.

The mass transfer equipment market divides into three segments approximately equally: new columns, revamps, and maintenance.

Revamping an existing column offers opportunities to improve the performance with respect to all of the aforementioned aspects.

Process engineers have a choice of using trays or packing (random or structured) within a distillation column. The appropriate mass transfer device to use will depend on the service and is a compromise between: n Capacity (through-put).

n Efficiency (separating power).

n Pressure drop.

n Fouling resistance.

The key difference between trays and packing is pressure drop (ΔP). The maximum recommended ΔP for a trayed column is about 20% of the tray spacing. For a 24 in. tray spacing, this is 4.8 in. of hot liquid and for an air-water system 4.8 in WG (12.0 mbar) per tray, i.e. 2.4 in. WG per ft (6.0 mbar/m) of column. Random packing (for non-foaming systems) is usually designed for a maximum ΔP of 0.5 in. WG per ft (4.0 mbar/m) whereas structured packing maximum ΔP is usually 0.25 in. WG per ft (2.0 mbar/m). Thus random packing and structured packing ΔP is approximately 20% and 10% respectively of a trayed column. Hence, when minimising ΔP is significant, packing is the preferred choice of mass transfer device.

Fouling is a perennial problem in the refining and chemical process industries. In the Kister1 2003 survey it was the top cause of column malfunctions. Packing is rarely a good choice in a fouling service except in some rare cases where ΔP is very critical (e.g. the wash zone bed of a crude vacuum tower). Here, packing is used even with the expectation that the bed will foul up. A well designed wash zone bed may achieve a run length of approximately 5 years before replacement is required, whilst a poorly designed arrangement may fail after just a couple of months.

Structured packing also offers a significant increase in capacity and efficiency. A comparison is given in Table 1 from Chen2 1984.

The comparison given in Table 1 is for standard trays and makes no distinction between the type. Capacity and efficiency rankings for the various tray types are:

n Bubble cap trays: lowest capacity and least efficient.

n Sieve trays: intermediate capacity and intermediate efficiency.

n Valve trays: highest capacity and highest efficiency.

Since 1984, high performance trays have also been introduced into the market which significantly increase both the capacity and reduce the ΔP.

Structured packing is available in two generic variants –with a 45° crimp (high efficiency) or a 60° crimp (high capacity). The relationship between crimp heights (depth) and the specific surface area (SSA) is given in Table 2.

For atmospheric operation, a comparison of typical capacity and efficiency is given in Table 3. Higher loadings and efficiency are possible for operation under vacuum. Structured packing is not recommended for high pressure (high liquid loading) systems due to reduced efficiencies.

Where pressure drop is not critical, trays remain the best choice and are the most economical. They are the most widely used mass transfer device. Anecdotal evidence suggests approximately 4 out of 5 operating columns worldwide use trays. Therefore, when revamping an existing column, it usually involves going from a trayed to a packed column or combination thereof.

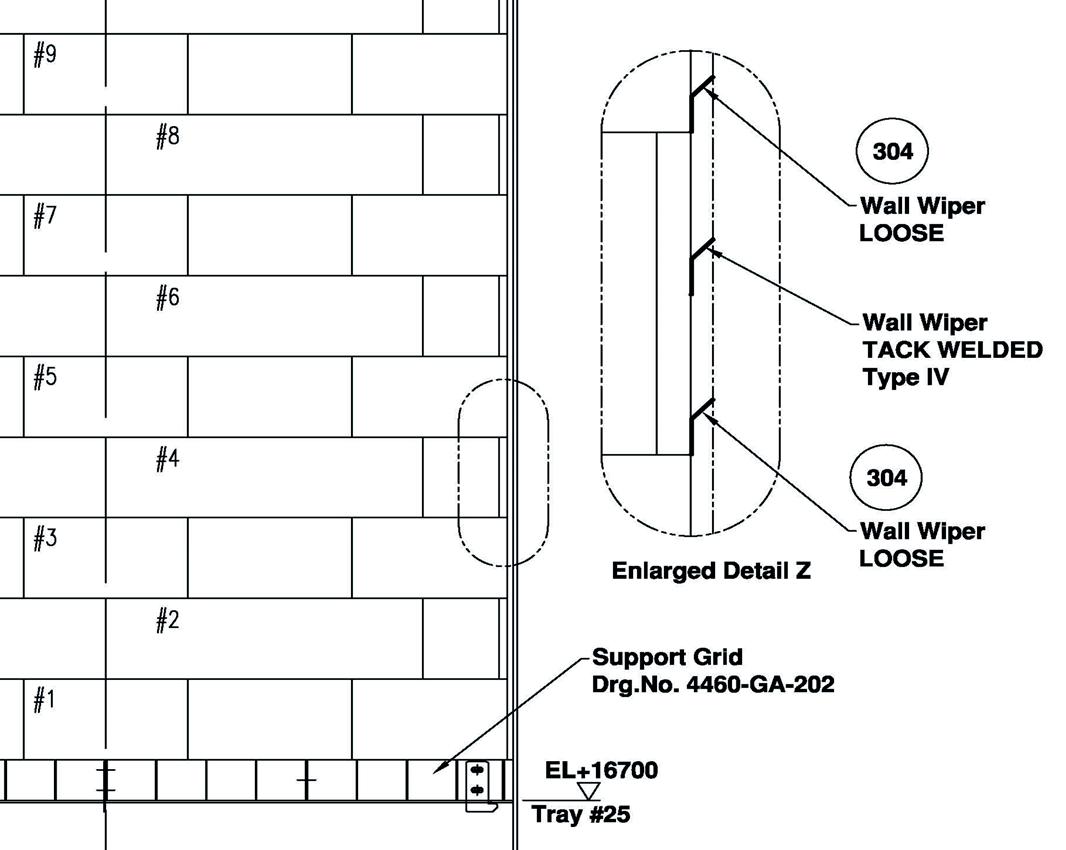

Structured packing is supplied in blocks (layers). Typical layer heights are given in Table 4.

Structured packing has inherent redistribution characteristics as opposed to random packing since, when installed, each layer is rotated 90° to the preceding one. Nonetheless, liquid will migrate towards the periphery and wall wipers are required to redirect liquid back into the packed bed as well as providing a seal to prevent vapour by-pass flow around the periphery of the packed bed. Some vendors provide only one wall wiper (to minimise cost) tack welded to the periphery of each block at the base. This is a false economy and can lead to operational problems. Rafi and Mnyapara3 2025 presented a trouble-shooting case study, where a structured packing bed using large block heights with only one wall wiper (welded at the bottom of the block) suffered a significant loss of separation efficiency due to poor initial liquid distribution. The loss in efficiency would have been mitigated if two wall wipers had been used.

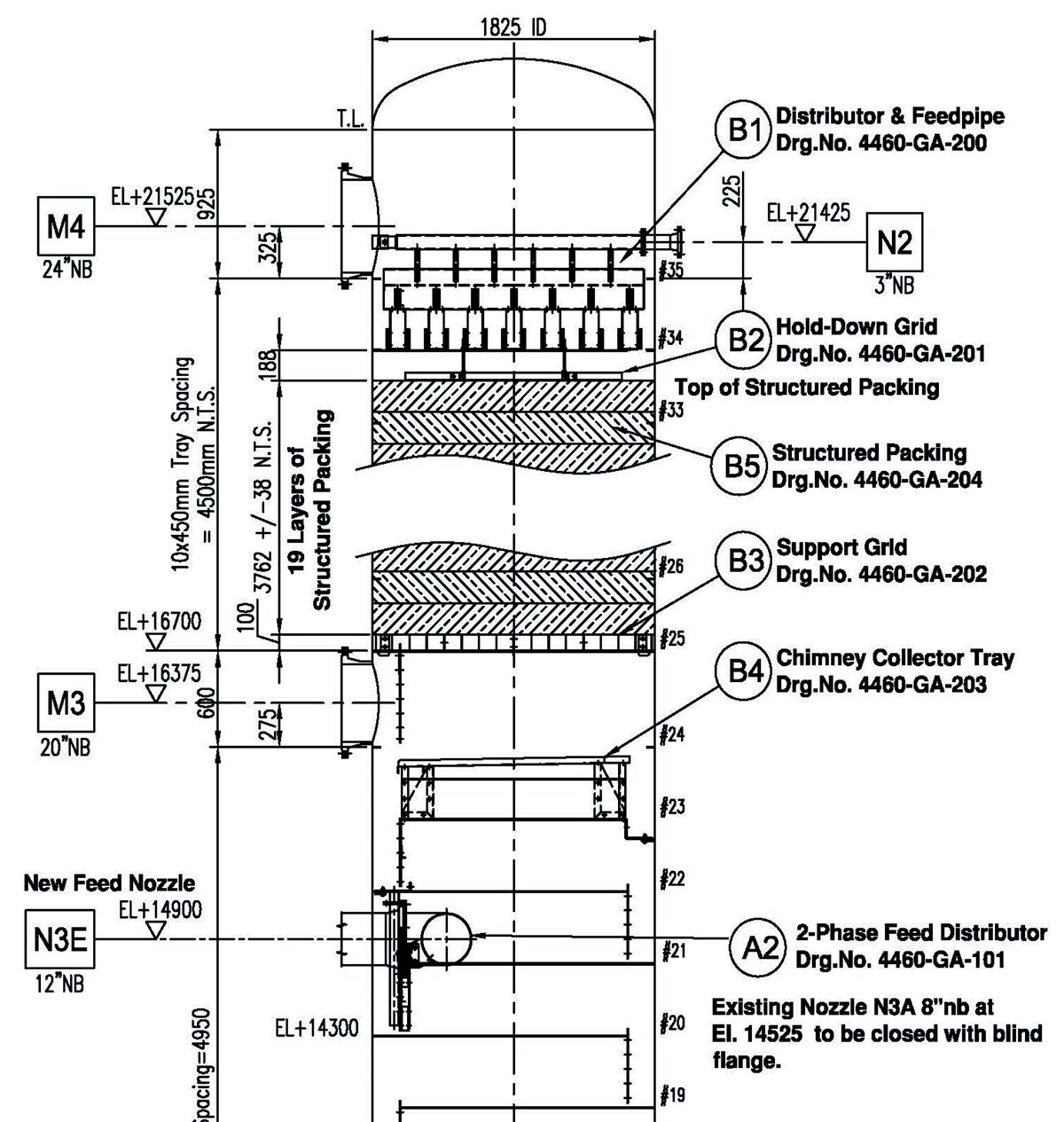

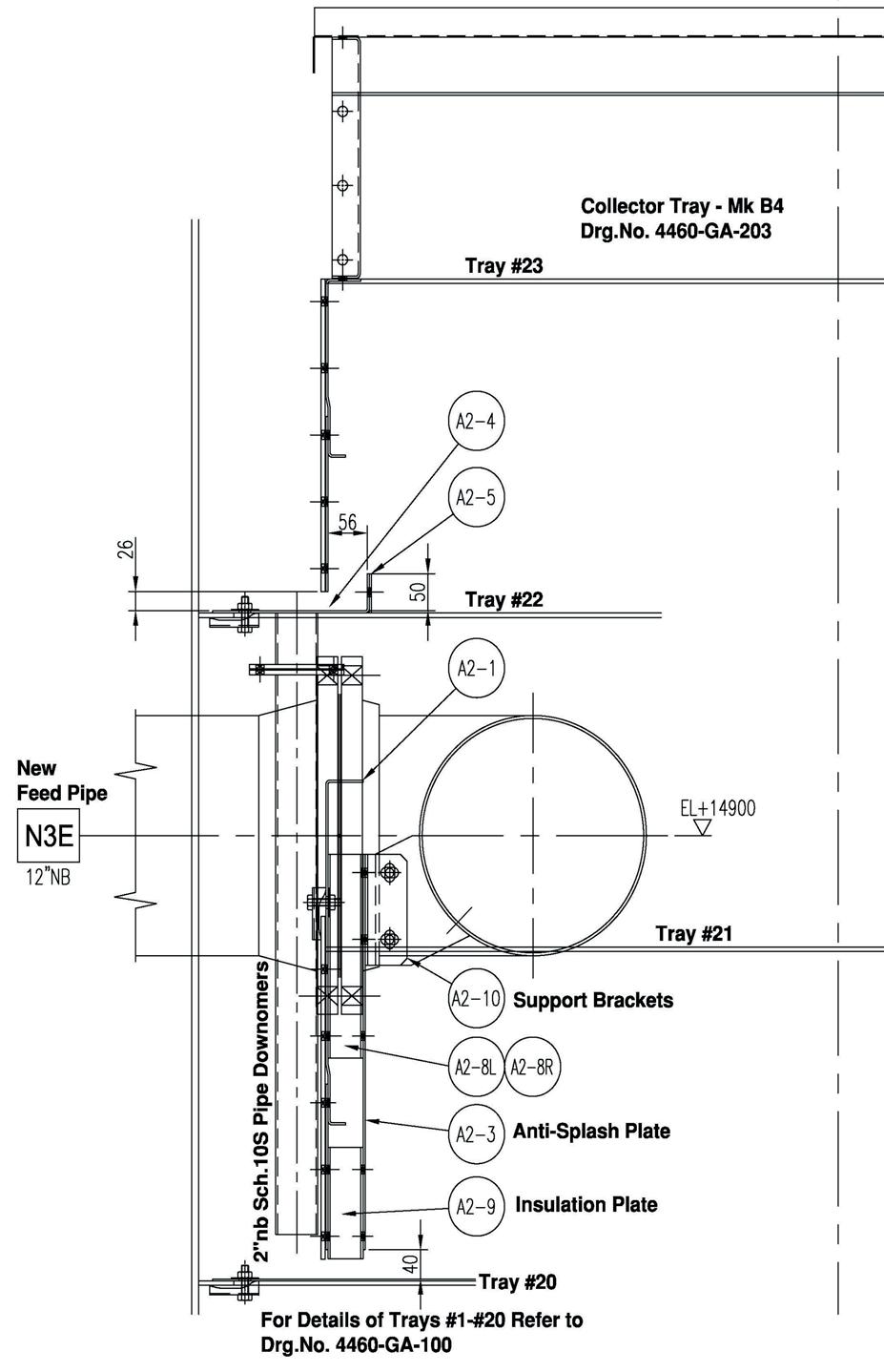

The ASME pressure vessel code states that the difference between measured diameters at any given cross-section cannot exceed 1% of the nominal diameter. This tolerance must be considered when designing mass transfer equipment (including structured packing) for new and revamped columns. For example, for the 1825 mm nominal diameter column, in the case studies given later in this article, the actual diameter at any given location may be 1806.8 mm to 1825 mm or 1825 mm to 1843.3 mm,

a difference of 36.5 mm between absolute minimum and maximum diameters. As such, two wall wipers for each block are recommended to ensure sealing at the periphery, particularly for revamps.

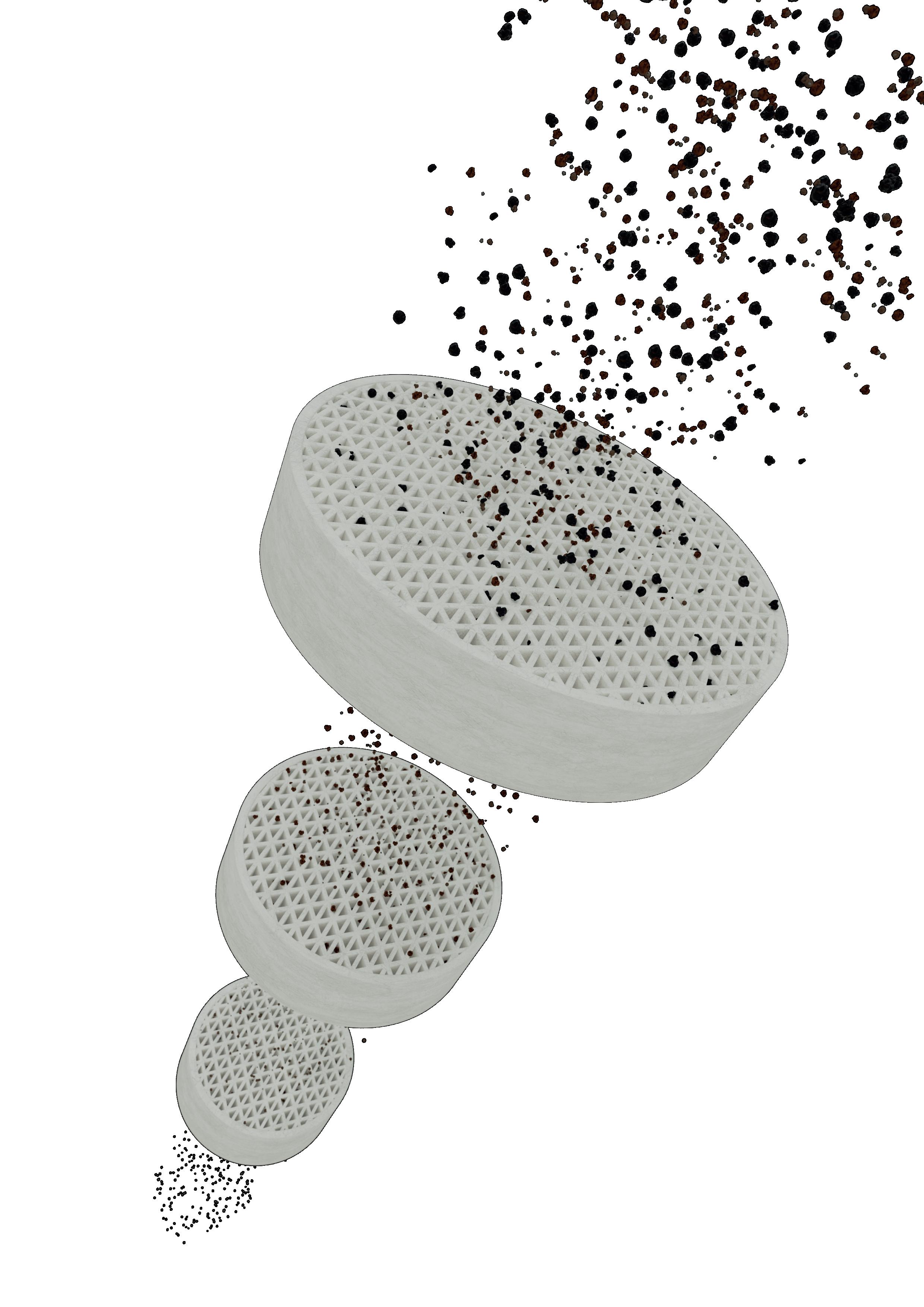

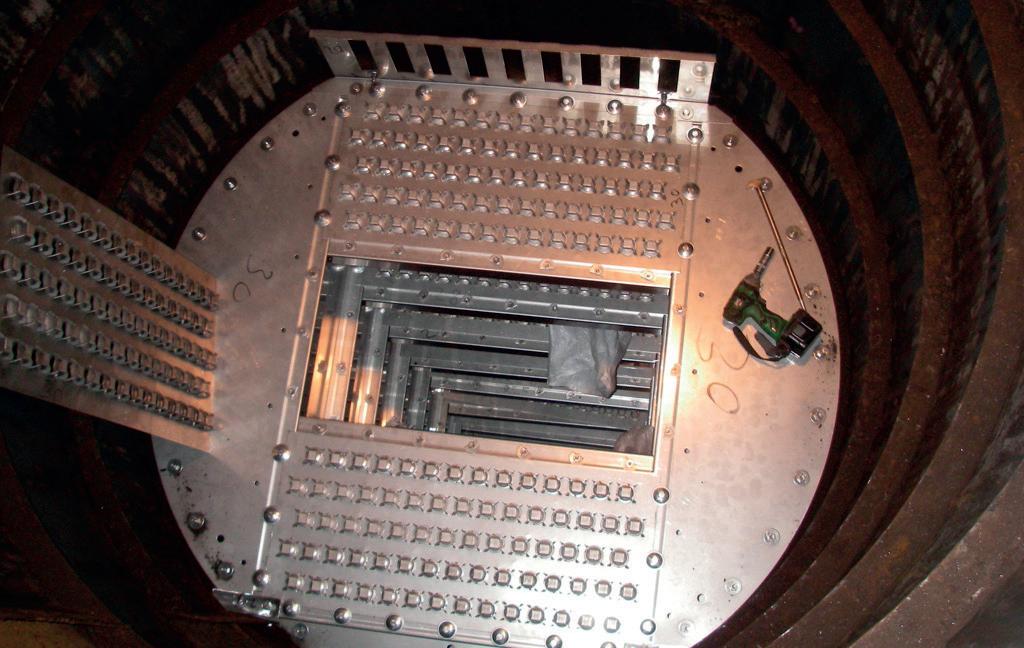

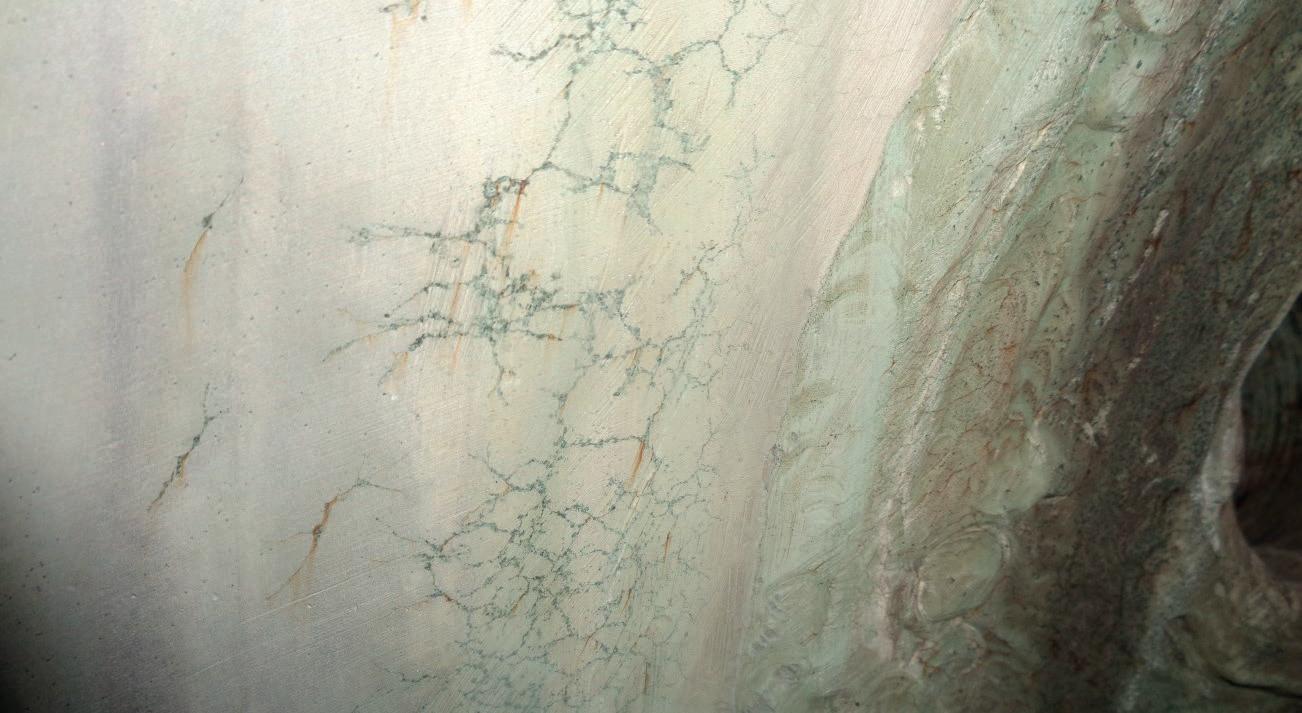

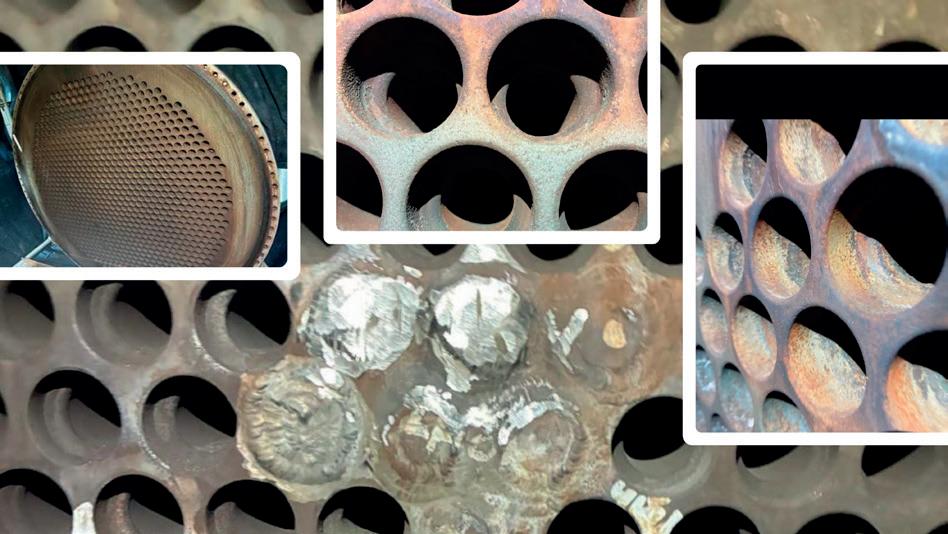

The image on the front cover of this issue of Hydrocarbon Engineering, taken during the dimensional inspection, shows a bed of M-Pak 200Y structured packing without any wall wipers. After the inspection, two wall wipers were tack welded to each block – see Figure 1. An alternative is to provide the second wall wiper loose for installation at site – see Figure 2.

A packed column, whether random or structured, is only as good as the liquid distributor. Careful consideration needs to be given to selecting and designing the appropriate type. The requirements are:

n Appropriate number of drip (distribution) points.

n Maximum uniformity of flow rates of the drip points (e.g. by maximising the operating and turndown liquid heads).

n Operating flexibility vis-à-vis liquid level at operating and turndown conditions.

n Avoid formation of drops and mists (e.g. by using drip tubes to avoid re-entrainment of liquid).

n Avoid splashing (e.g. by using drip tubes to discharge liquid close to the top of the packing).

n Avoid merging of single jets generated by the distributor (e.g. by using drip tubes).

n Maximise the open area for vapour/gas flow thus minimising ΔP (e.g. by using narrow troughs).

n Maximise fouling resistance (e.g. by elevating discharge holes from the deck).

n Reasonable cost.