8 minute read

Metals matter

Brad Cook, Sabin Metal, USA, examines what is happening within the world of platinum group metals (PGMs), and explains the importance of responsible recycling.

Are you reading through contact lenses or have you had LASIK surgery? Have you shaved any part of your body this week? Do you ever make use of a cell phone, tablet or computer? Is your home insulated with fibreglass? Have you travelled by plane, car or boat recently? Have you ever taken ibuprofen? Do you know anyone who has a pacemaker? Ever fertilize your garden? Ever use a sticky note? If you answered ‘yes’ to any of the above, you have platinum group metals (PGMs) to thank, and at least a few creative minds somewhere in history. As of 2020, nearly 25% of all consumer products either contain PGMs or are made using PGMs.

To get an idea of its rarity, consider that all of the platinum mined in human history would fit inside a four-bedroom house. That may sound impossible, but 1 m3 of platinum weighs over 21 t. A 20 l bucket of pure platinum would weigh approximately 430 kg.

This article will discuss the supply, demand and recycling of PGMs; examine what is happening within the world of PGMs and the related effects on the market; and review how precious metal users and suppliers can best coordinate for mutual success.

PGM demand

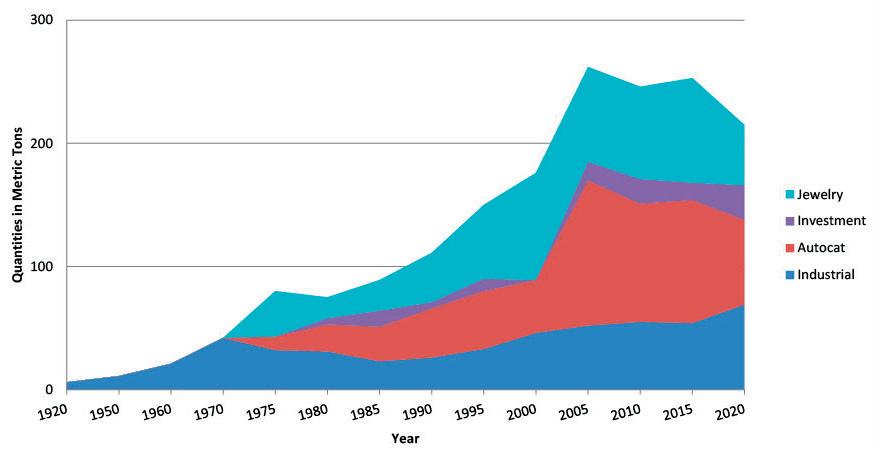

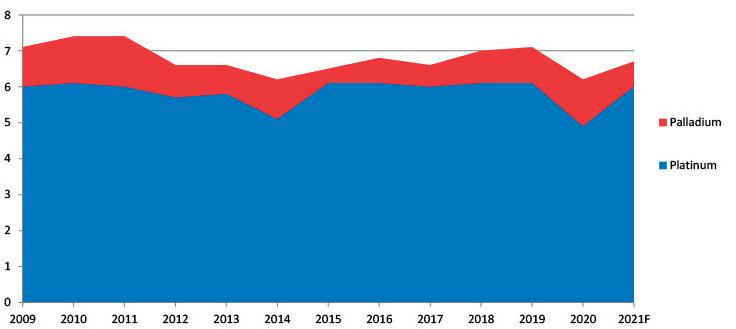

Figure 1 illustrates platinum demand by application over the last century. Demand for all PGMs has been growing steadily for decades. The 1970s saw the introduction of automotive catalysts, and at that time they all used platinum. In the mid-1990s, combustion engine manufacturers switched their convertor catalyst from platinum to palladium-based, then in 2001 they switched back. In a nutshell, roughly one-third of the platinum mined today is used for catalytic convertors, another third for industry (petroleum and petrochemical refining, chemical production, fibreglass, etc), and the rest falls under jewellery and investment.

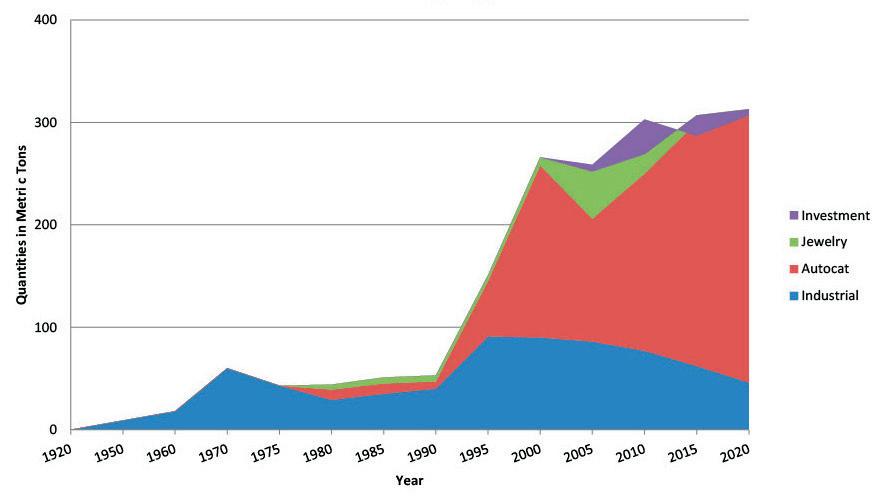

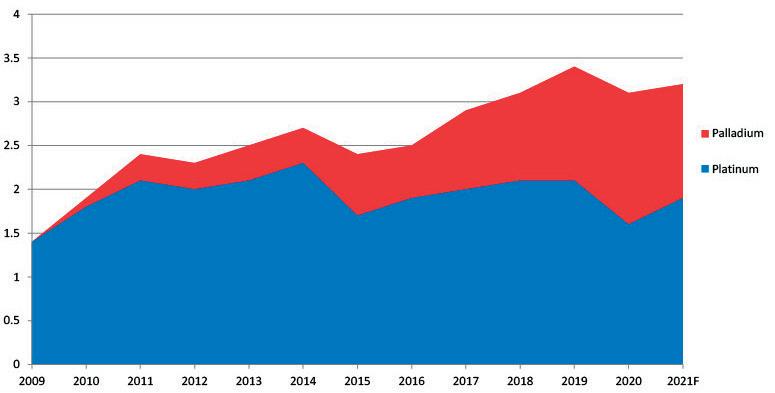

Figure 2 shows palladium demand by application over the last 100 years. Approximately 90% of all palladium that is above ground is riding around in the catalytic convertors of automobiles. Therefore, since the 1970s, the main ‘driver’ of both platinum and palladium has been the automobile market – initially in the West and more recently with the expansion of the automotive catalytic convertor in the emerging world. According to ScotiaBank, 2020 auto sales were off by over 15%, and totalled just under 64 million units worldwide.1 In 2021, there was a slight recovery to 67 million, which is still 8 million units short of 2019 levels.

PGM supply

In terms of supply, South Africa produces over 70% of the platinum and almost 40% of the palladium annually, and these mines continue to get deeper and deeper every year, while the ore quality deteriorates simultaneously (see Figure 3). In addition to this, the challenges of labour issues, water supply, and power shortages persist in this region.

Russia accounts for approximately 15% of platinum production and roughly 50% of palladium production annually. On 8 April 2022, the London Platinum and Palladium Market (LPPM) announced that it has suspended the two Russian refiners on its ‘Good Delivery’ list. This means that, as of that date, most of the fine precious metals from Russia will no longer be considered ‘Good Delivery’. The New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX) has followed suit, and the Osaka Exchange is considering similar measures. ‘Good Delivery’, as defined by the LPPM website, is “the list of acceptable refiners of platinum and palladium plates and ingots in the London market, the ‘LPPM London/Zurich Good Delivery List’, has been developed and is maintained by the London Platinum and Palladium Market (‘the LPPM’) in order to facilitate the international distribution and acceptability on technical grounds of standard plates and ingots produced by those refiners who meet the criteria for inclusion in the list; and whose plates or ingots have passed the testing procedures laid down by the LPPM.”2

These suspension announcements are expected to cause a severe tightening of the physical availability of PGMs, and potentially some disruption for automotive and industrial users. Even tougher sanctions against Russia are possible in the future.

Figure 1. Platinum demand by application.

Jewellery

Investment

Autocat

Industrial

Jewellery

Investment

Autocat

Industrial

Figure 2. Palladium demand by application.

Palladium

Platinum

Figure 3. Mined supply (million ounces troy).

Recycling

The recycling picture is mixed (see Figure 4). While the industry deserves praise for the improvement in ounces recycled (recycling met only 19% of the demand in 2010, but reached 28% in 2020), this is almost entirely due to autocatalysts being recaptured in emerging markets. The hidden concern is that more PGMs now end up in the hands of consumers than in the hands of industry, and the difference in recovery from these two groups is substantial.

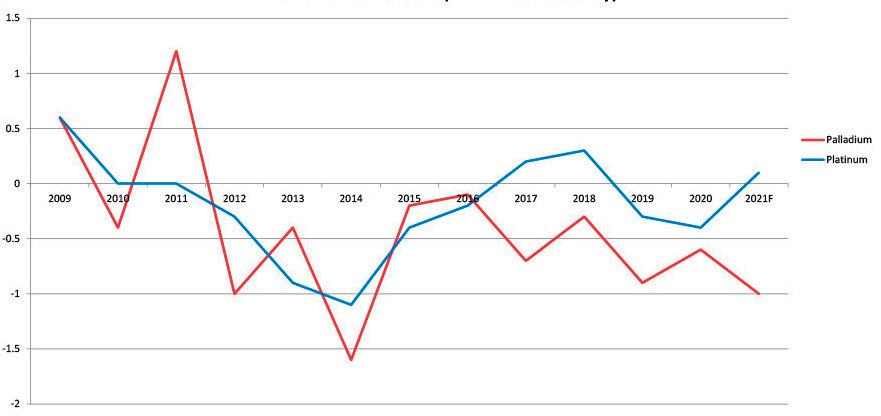

In short, there are various market forces pulling in all directions at once: the COVID-19 pandemic, the chip shortage, the logistics mess around the globe, labour shortages, Brexit, and now Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Figure 5 illustrates what happens when supply, recycling and demand are overlayed.

Total platinum supply is in surplus of demand by about 200 000 ounces troy, and this is expected to continue for several years. Palladium, on the other hand, is in deficit by over 1 million ounces troy. It should be noted that these numbers do not take into account the last few months of world events. Expectations within the precious metals industry are that palladium prices will experience sustained volatility, lease rates will remain elevated for the short-term, and the aforementioned restrictions will continue in regard to the availability of physical metal.

The sheer amount of PGMs that the world demands every year makes mining crucial, and the industry is focused upon improving existing methods and controls. There is not much that can be done about political hot spots or the deteriorating ore quality, but workers can be protected as the mines get deeper, carbon footprint can be examined and minimised, and the cost of refining can be reduced. Thankfully, there are a number of intelligent individuals working on just that.

Now, and for the foreseeable future, PGMs will remain at the cutting edge of providing answers to some of humanity’s most pressing needs, such as the following: n Conservation: automotive catalysts and the industrial filtration units that reduce emissions. n Energy: fuel cells, gasoline, jet fuels. n World health: treatments, medical devices, and pharmaceutical products that contain PGM or are made using PGM; man-made gems in precision lasers for surgery.

Clearly, however, we need to get better at recycling. We can say with confidence that the reuse of a PGM ounce will mitigate energy use and lower emissions vs mining a PGM ounce. A beautiful aspect of precious metal sustainability is that they can be refined and reused indefinitely (see Figure 6). The goal should therefore be to gather them as thoroughly as possible after each of their incarnations, and continue to maximise the number of refine/reuse cycles.

Palladium

Platinum

Figure 4. Recycled PGMs (million ounces troy).

Palladium Platinum

Figure 5. Movement of stocks (million ounces troy).

Figure 6. Molten precious metals pour.

Considering costs

In order to further perfect the refine/reuse cycle, precious metal owners must clearly understand the old adage that ‘cheaper is not better’. Losing out on a contract because a competitor bids less is always frustrating for sales and management, in any industry. However in the precious metals industry it is puzzling, because the important thing in the equation is not the processing fee or freight costs; it is proper weighing and sampling, and accurate analysis to correctly and honestly determine the precious metals content. This sort of quality in design and execution cannot – and does not – come cheap.

To put it bluntly, one must divine the equilibrium between quality of service and the cost. An insufficient or unethical service that saves money is far worse than an honest and complete service that costs a bit more. With regard to the precious metals industry, those insufficiencies come in the form of incorrect sampling, illegal disposal of wastes, and other improper behaviour. A ‘lowest-bidder’ mentality leaves companies exposed to a host of risks. All precious metals refiners are not the same – technically or ethically. Professional witnessing, compliance with anti-money laundering legislation, and the knowledge gained by the catalyst users have helped reduce actual robbery dramatically; however, the buyer must still beware.

Conclusion

The metals we call ‘precious’ were originally given that title based on their beauty. They were shiny – and people have always liked shiny. This made these metals highly sought after, which in turn made them valuable. They are still considered very valuable for their appearance, but the more we learn about these incredible elements, the more value they will continue to gain for even greater reasons.

It is important to ensure that PGMs end up with a responsible recycler. Root out and eliminate the unethical and wasteful through due diligence and investigation; forge global partnerships with industry stewards; allow for fair margins, so that research and development can be properly supported; and discard perceived limitations and challenge the status quo.

References

1. YOUNG, R., GU, L., ‘Improvement in December’s Global Auto Sales Does Little to Bolster the Year’s Final Tallies’, Scotiabank, (27 January 2022), https://www.scotiabank.com/ca/en/about/ economics/economics-publications/post.other-publications.autos. global-auto-report.january-27--2022.html 2. ’Good Delivery Rules’, London Platinum & Palladium Market’, (July 2020), https://www.lppm.com/good-delivery-rules/