...oak sourced from sustainably managed forests.

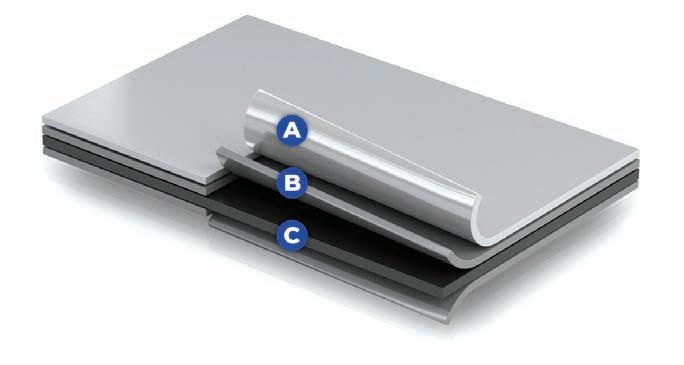

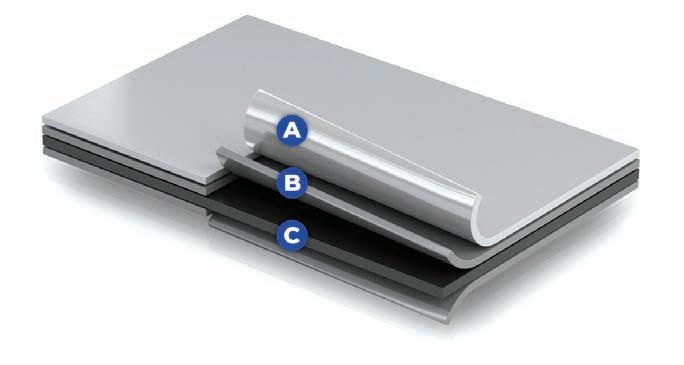

What if your choice of steel can create a new world of possibilities.

...oak sourced from sustainably managed forests.

What if your choice of steel can create a new world of possibilities.

An idea is only as good as the execution. At Safal Steel we are at the forefront of steel technology. Discover steel like you have never seen before, durable, flexible, Zincal®

Zincal® steel can last up to 4 times longer than normal galvanised steel due to its ability to perform under extreme atmospheric conditions and due to its advance thermal attributes. We offer you piece-of-mind that any vision you create with Zincal® steel can stand the test of time.

The possiblities are endless, just ask for Zincal ® .

In an era defined by environmental urgency and creative responsibility, sustainability as we know it is no longer enough. It is the foundation that must undergo continuous re-assessment, deliberation, and transformation as we move closer to a resource-pressured future. This August, Scape explores the evolving language of sustainable design through materiality, impact, and principle-driven thinking. We interrogate how architecture and interiors can do more than simply tread lightly — they can give back, regenerate, and reframe our relationship with the built environment. From vernacular traditions to altering the elements, from designs rooted in meaning to the ethics of long-term thinking, this issue is a deep dive into how intentional design commits to longevity.

We’re proud to feature insights from some of the most pioneering voices shaping this space today: Anthrop Abbott Architects, Studio Sway, Ant Vervoort, Peter Rich, Luxury Frontiers, Marc Sherratt, Gregory

Katz, and many more. Each contributor brings a different lens to what protecting our future can look like: raw, refined, radical. For Shaakira Jassat, her design intervention targets the source of everyday rituals while Frederik Labuschagne, the architect turned plant-based chef, works at the intersection of architecture and gastronomy, promoting food sustainability. Others bring neglected social aspects: gender, history, race that are all embedded in the art of preservation.

Sustainability means so many different things to different people beyond the ‘green’: from recalling memories to farm-to-fork and regenerative practices; from thinking with community to the technicalities of building processes and new materialities. Sustainability not as a checkbox, but a design instinct that dares one to take on the unthinkable.

Join us as we uncover how today’s spaces are being made for tomorrow.

Chanel Editor-in-Chief

As the green building movement continues to reshape the construction industry, flooring materials are playing a key role in driving sustainability from the ground up. One brand leading the way in this space is KRONOTEX, a German flooring manufacturer whose eco-conscious approach extends across its entire supply chain — from raw material sourcing to manufacturing and even post-consumer recycling.

Smartly sourced, globally responsible KRONOTEX sources all of its wood — the primary ingredient in its laminate floors — from forests located within a 300-kilometre radius of its production facility in Heiligengrabe, Germany. This not only ensures the responsible harvesting of wood from sustainably managed forests but also keeps the environmental impact of transportation to a minimum.

Comprising approximately 90% wood, KRONOTEX laminate flooring offers a natural, renewable alternative to conventional flooring products. The decorative layer, made primarily from high-quality paper impregnated with melamine resin, is free of harmful substances such as pesticides, plasticisers, chlorogenic compounds, and toxic heavy metals.

Sustainability that starts at the source — and never ends KRONOTEX's commitment to sustainability doesn’t stop at sourcing. The company operates under a certified ISO 14001 environmental management system, which ensures ongoing

optimisation of resource usage, energy efficiency, and waste management.

Using a cascading model, KRONOTEX recycles wood multiple times throughout its production process. Even wood scraps that cannot be repurposed into flooring are recovered and used as a renewable energy source to power the company’s operations. This closed-loop approach significantly contributes to carbon footprint reduction and positions KRONOTEX as a model of circular economy principles in action.

Durable, healthy, and easy to maintain

Beyond its green credentials, KRONOTEX laminate flooring delivers long-term functional benefits that align with the needs of both residential and commercial buildings. Its abrasion-resistant and stain-resistant surface is also lightfast — maintaining colour and integrity over time.

One standout project showcasing KRONOTEX’s impact in South Africa is the Eco Golf Estate in Pretoria. Designed with sustainability at its core, this development integrated KRONOTEX laminate floors to meet both environmental and aesthetic goals — providing an elegant yet robust solution that supports the estate’s broader commitment to green living.

Certified for peace of mind

KRONOTEX laminate flooring carries a number of internationally recognised certifications, affirming its sustainability and safety credentials, including Blue Angel — Germany’s leading eco-label for environmentally friendly products, EPD (Environmental Product Declaration) — for verified data on environmental performance across the lifecycle, FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council) — ensures that products come from responsibly managed forests, PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification) — promotes sustainable forest management through independent third-party certification.

With increasing pressure on the built environment to reduce its carbon footprint and promote healthier indoor spaces, KRONOTEX laminate flooring offers a compelling solution.

Visit swisskrono.com/global-en/ to explore KRONOTEX laminate flooring, proudly distributed nationwide by Brands 4 Africa.

Pedersen + Lennard Sets the Standard for Thoughtful Furniture Design

The duo behind Pedersen + Lennard invited us into their 'dream workshop' in Maitland, where fresh oak scents and fine-tuned grains welcome you to the authentic experience. Here, local makers thrive — a central tenet of the minimal yet somewhat playful furniture brand. You can smell the commitment to Cape craftmanship. Over the last few years, the brand has sky-rocketed, with its Scandinavian–South African design and signature cross making it instantly recognisable. From Nando’s to the V&A Waterfront, Pedersen + Lennard has found a place for their designs in everything from private residences to retail — with pieces made to last many lifetimes.

Scape spoke to the brand’s founders, Luke Pedersen and James Lennard, to learn more about the brand and its rise to icon status.

The cross that P+L is associated with is simple but so distinctly yours. What is the story behind this?

JL: We needed something to join our names, and we didn’t want to use an 'and' sign, and it turns out that it’s also a great cutaway for material because everything just falls away and leaves the logo behind. It can create cool shadows.

LP: It’s easy to recognise. We didn’t want a flashy logo. We didn’t want words because our names are quite long already. And we find we actually design for the logo: it’s not just something we put on afterwards; we consider it part of the piece. Our thinking is if we see one of our pieces from far away, you should know that it’s ours by the proportion and the overall style of the piece. Then the logo, when you get close enough, is confirmation.

What influences your designs?

JL: Exercise. All of my best ideas come to me when I'm riding my bike or surfing or running or whatever I'm doing. I think I'm so surrounded by stuff, I don't really look beyond these walls for inspiration. In previous years we used to look at magazines, but you just get bombarded and end up sketching something that somebody else has already designed.

LP: I'm driven mostly by curiosity. I'm super curious, all the time, about different things, materials, processes. What could this be? That's the question I ask myself a lot. I think I've learned a lot over the years from Enzo Miri and his whole way of thinking around direct experimentation. It's very much a process of hands-on sketching and playing. And I've learnt a lot through that.

All of your pieces are created in-house at your factory here in Cape Town. Why is it important for you to manufacture locally?

past. And, unfortunately, we've got a tough legacy to change. We really value our people and treat everyone with respect — it’s really the basics that you think are normal in these environments that unfortunately aren't. And a lot of people don't understand how obsessed we are with quality. Even the smallest thing we make here is touched by virtually everyone in the business, from the designers in the offices right through to the factory; it goes through so many hands and so much care at every step.

Is there a piece that stands out for you — either as a favourite or because of how it came together?

LP: The Osaka Chair. It came out on a Friday afternoon in one moment of inspiration for me. We’ve got a very old Italian pipe bending machine, which is my favourite. It obviously didn’t come out in that afternoon; it was stewing for a long time, but it just came together in one go. I’m always amazed at the fact that that is possible.

How do you incorporate sustainable practices into your design process?

LP: For me, it's a lot more about rationality than the buzzword of sustainability. We have a very circular system of reducing waste where our sawdust gets turned into compost mulch and we design products with our waste material. And while these are buzzwords and good things to do, it’s more about a rational way of production. It makes sense to utilise your resources to the maximum.

What do you hope the brand’s legacy will be?

“We

have a very circular system of reducing waste, where our sawdust is turned into compost mulch and we design products with our waste material. And while sustainability is a good thing, to me, it’s also about a rational way of producing."

JL: I find it so inspiring that we've got everything here. We used to outsource a lot of our production, and it made the process so scattered and complicated. Now it's all under two roofs; we can do anything we want with a click of a button. I think anyone who has an affinity for production can understand that the way we work is unique, and that’s what makes it so special.

LP: It's like a dream workshop. We’re really trying to address some of the ways manufacturing has been done in South Africa in the

LP: I've always been a deep believer in the value of good design. And by value, I mean what brings value everywhere: to people, to the environment, to socio-economic change. I think production is a great job creator. It's also the way to train and upskill people. So, I think, looking at our product in say, 20 or 30 years’ time, someone will have a vintage piece, and they’ll trace it back to this factory, and they'll think, ‘Wow, this is an amazing level of detail and quality.’ And they would see the culture, the people, the training — you don't make the products we make without it. And we have a lot of fun along the way.

JL: For me, like, even just knowing that the brand, the two of us, our team, design furniture that's going to last for many, many years to come is enough. Whether it stops at some point, whether it carries on with Luke’s oldest son or whoever it might be. It’s about what we’re doing right now. And that's actually enough.

@pedersenlennard

pedersenlennard.co.za

Timeless and luxurious flooring.

Smooth, versatile and hygienic.

Seamless indoor to outdoor flow.

Ideal for residential and hospitality.

Suitable for commercial and retail.

Impact and scratch-resistant.

Stain-resistant.

Slip-resistant.

Low maintenance and durable.

Eco-friendly and sustainable

UV stable.

Can be applied directly over tiles, eliminating grout lines.

Quick and neat installation by certified national applicators.

Available in 36 colours.

Available in 60 countries worldwide.

Astrid Hébert on Building Platforms That Celebrate and Connect Designers

Swiss-based 3C Group is the force behind some of the most respected platforms in global design. This year, in collaboration with Africa Design School, the first non-profit design school in West Africa, they launched the African International Design Awards (AIDA). We spoke with director Astrid Hébert about the vision behind these initiatives.

Astrid, what’s the vision that brings 3C Group’s diverse initiatives together?

We are committed to celebrating people who care deeply about what they create. Each award highlights a specific design discipline — what unites them all is our belief that creativity deserves to be recognised, nurtured, and shared.

You also oversee D5 MAG, which has grown into a platform in its own right.

We envisioned it as more than just a companion to the awards. We cover not only big names but also emerging talents, experimental projects, and the stories behind the designs. It became a platform that reflects our philosophy: that creativity is everywhere and deserves to be documented.

You recently launched the African International Design Awards. Why Africa — and why now?

The AIDA Awards aim to celebrate diversity, sustainability, and the power of design to drive change. Africa is a vibrant, exciting landscape for design, yet it remains underrepresented on the global stage.

We've partnered with the Africa Design School in Cotonou, Benin, an institution dedicated to promoting design across Africa and training the next generation of talent. They bring a deep understanding of both local context and international standards — and with Bibi Seck as our Head of Jury, we’ve brought on someone who truly embodies that global-local connection.

What excites you most about what’s next for 3C Group?

3C Group is growing not just in the number of platforms, but in the depth and quality of experiences we offer. We’re planning meaningful in-person award events where winners can connect and celebrate together.

We’re also investing in stronger partnerships with schools, brands, and industry leaders to increase our impact; the next chapter for 3C Group will focus on deepening these relationships.

For more information about 3C Group, its awards, and D5 MAG, visit 3cawards.com.

4 Liddle Street, De Waterkant, Cape Town Design District, 14A Kramer Road, Kramerville, Sandton

“fabricating & installing the BIGGEST windows & doors in AFRICA...luxury in simplicity”

Unless its a product of q.one fenestration. Then everybody does it

q.one fenestration

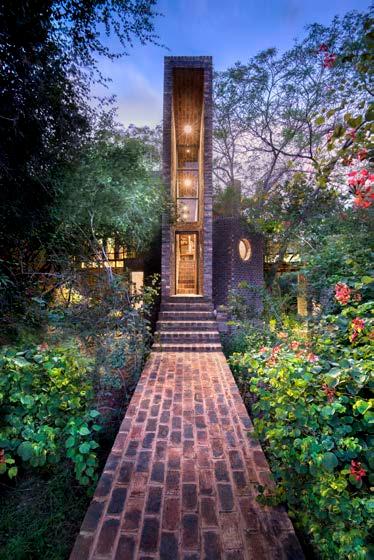

Ant from Frankie Pappas

Speaks on Architecture

That Belongs — to Place, Community, and Our Future

Frankie Pappas is a name that belongs to everyone and no one. It is the pseudonym of the architecture firm co-founded by Ant, a firm known for their bold forms and incredible synergy with the natural world. Frankie Pappas is a maverick in the architecture industry: by allowing multiple thinkers to act under one identity — preventing the idolism of a singular name — they re-write the practice of architecture as we know it. We spoke to Ant about all things local, human, and anti-ego.

“We wanted to build a space that was small and strange and useful.”

In a TedX talk from 2013, you spoke about the ‘tyranny of faith’ and how faithlessness breeds much-needed critical questions around the legacies of apartheid. I know that the talk was a few years ago — what is your assessment of faith and democracy in South Africa today?

When we speak of faith, we mean it in all its forms, but most of all as the uncritical belief in systems, stories, and slogans. For us, faith is dogma. And in South Africa, as in much of the world, dogma has a long and cruel legacy. We have placed our faith in the constitution. In reconciliation. In democracy. In politics. In big businesses.

And we have been hoodwinked.

We have been told, ‘Have faith.

We’re working to make things better.’

But the cavalry is not coming.

Faith does not build good houses or great cities.

It does not fix trains or mend broken buses.

It does not teach us to think better or act bolder.

It certainly does not challenge power. Our belief is that democracy without critical doubt becomes oligarchic fascism.

But here's the thing: we do see change coming. We know our new generations have not had their turn to shape the world they dream of.

So we do not preach apathy or cynicism.

We call for radical, uncomfortable, courageous doubt.

The kind of doubt that asks: who benefits from this version of democracy?

Who gets to call this freedom?

Who decides which cities we build and who gets to live in them?

We do not need more faith in the rainbow.

We need a clear-eyed confrontation with the storm.

A hard rain is going to fall.

How do you see indigeneity and localised practices fitting into this conversation? Vernacular architecture is, of course, a key topic in the context of cultural sustainability in South Africa.

If we are to take the topic seriously, then indigeneity can never be a style. It can never be an aesthetic. It can only be a way of thinking, understanding, and responding to place, to climate, to culture, to materials, and to community. It is not about replicating thatch or weaving or some other handiwork. It is about building with the intelligence of people who care about making their little portion of the world better, generation after generation.

So yes, indigeneity and localised practices are absolutely central to all forms of sustainability. But only if we stop treating them as an aesthetic or a branding strategy or a feel-good vibe. They must be treated as living knowledge.

“We call for radical, uncomfortable, courageous doubt. The kind of doubt that asks: who gets to call this freedom?”

Architecture is still being imposed on the world. This is wrong. It should emerge. It should come from the landscape. It should come from the climate. It should come from accessible materials. It should come from the ways people cook and gather and rest and listen to music.

Often the word ‘sustainability’, in its generic interpretation, is limited to the environment, hereby neglecting ‘human’ systemic issues. But your project, House of the Pink Spot, raises awareness of gender and sustainability (the idea that there is ‘no sustainability without women’).

The role of the architect is to look after the health of the city. Not to create community. But it is the role of the architect to create cities that are conducive to community.

So yes, we do think that the word ‘sustainability’ has become dangerous in its vacuousness. It has been flattened into a checklist of solar panels and carbon offsets. And emptied of meaning. We wrote that there can be ‘no sustainability without women’ as a provocation. A kind of angry joke. It was a response to this checklist of sustainability criteria. We were saying exactly what your question is getting at.

We wanted to build a space that was small and strange and useful. A place for rest. A place to gather. A place where women could feel safe. A place that does not pretend to solve everything, but that refuses to look away. If we want to design sustainable futures, then we have to stop pretending that environmental issues can be separated from human ones.

Our communities are not only dying. They are being killed and raped. And it is not radical to say that the people doing the killing are not the ones building little pink structures on the edges of forgotten towns.

That is what House of the Pink Spot tries to say out loud.

Frankie Pappas is not your standard design firm. It changes the practice of architecture by allowing architects to work, collectively, under a pseudonym. Is there a sense that ‘undoing ego’ is also critical for the future of (sustainable) architectural practices?

The name Frankie Pappas makes a joke at the tradition of firms being named after the founders. A joke at ego, I suppose.

But more than that, it is a deliberate decision to try and create a small space where the work matters more than the person. Where ego has to sit in the back seat. Where ideas are tested on their strength, not their origin.

Architecture, as a discipline, has been shaped by some pretty toxic dynamics. The worship of ego. The celebration of the individual. The erasure of the collective. This has not helped the profession, and it certainly has not helped the world. To me, at least, the Western world has seemed obsessed with idolising individuals — and anointing them as ‘geniuses’.

What I want to see is more energy given to the creative opportunities within this co-operative intelligence. I love the idea of genius. But there has never lived a single one. So yes, undoing ego is critical. Not just as a cultural gesture, but as a structural one.

Your other projects, like House of Cape Robin and House of the Tall Chimneys, display an exceptional grasp of materiality, both aesthetically and functionally. What are your methods to tick both boxes so beautifully?

We do not have a method, really. Just an obsession with paying attention. We believe that beauty is not something added. It is not

a finish. It is the result of care. Of intense work. Of patience. Of generosity with your time and your life.

We are not trying to invent new forms. We are only trying to discover something that may already belong to the place. When you treat materials with respect, they tend to reward you.

Do you predict that off-grid buildings and movement to towns outlying cities will eventually become the new normal?

My belief is that smaller societies are far more sustainable than larger ones.

Your decisions and actions are concentrated, local, immediate, and measurable. And you feel them.

This is why I believe in smaller, decentralised communities. Where energy, food, water, and justice are locally managed. Where accountability is intensely personal.

Where poverty is impossible to ignore or outsource.

And where sustainability is not a policy goal or a set of checkboxes, but a shared and daily necessity.

We often speak of landscape architecture in terms of functionality, aesthetics, or ecological value. But what about meaning? What about those less tangible but deeply resonant elements — memory, narrative, identity — that bind people to place? As designers, our work is not just about shaping space; it’s about shaping how people feel, remember, and connect. Meaningful landscapes are revealed through stories, uncovered through listening, and anchored in material that holds memory. And it is through this that landscapes become well-loved and withstand the test of time.

The notion of landscapes as a cultural text is not new. Writers like James Corner, Christophe Girot, and Elizabeth Meyer have long considered landscape not simply as a backdrop to human activity, but as a layered, temporal medium. Corner’s concept of recovering landscape invites us to ‘uncover’ rather than ‘impose’, calling for practices that respond to context and reveal latent meaning. Girot’s idea of ‘landing, grounding, finding, and founding’ proposes a sequence of gestures for revealing a site's identity through its topography, memory, and use.

This approach to landscape as living stories is evident in the work of Walter Hood, whose projects bring visibility to histories often overlooked. Closer to home, the new Cape Town Labour Corps

Memorial in The Company’s Garden takes up the same challenge. It reframes memorialisation not as an act of monumental permanence, but as a textured, living surface within a layered public space.

Our practice at Yes& Studio has increasingly focused on public spaces shaped by everyday use and layered histories. We are working towards a methodology of understanding space, rooted in listening, research, and contextual depth, in order to give us clues about how to design.

One such project finds its home on a key historical square in Langa, a place marked by control and surveillance under apartheid, but

also by stories of the everyday. We have viewed the entire project as an opportunity to uncover the complex stories and multiple histories of the place. In developing a narrative, we conducted interviews with community elders and, in so doing, identified themes that will impact the designs of the place.

Similarly, our work at the Adderley Street Flower Market reveals another mode of storytelling: one rooted in multigenerational trade. Here, flower sellers have occupied the same stretch of the city since the early 1900s. Theirs is a living heritage. Our work here involved co-creating a visual and oral archive with the flower sellers. We asked: who appears in your oldest market photographs? What plants did your grandmother sell? How has the market changed over time?

In both Langa and Adderley Street, meaning did not come from design intent, but from listening. It came from holding space for stories that are often overlooked, particularly those told by women.

The materiality of memory

More than shaping form or surface, materials carry embedded narratives and associations that allow a landscape to resonate at a deeper level. When chosen with care and contextual sensitivity, materials can evoke memory, mark presence, and prompt reflection.

“What about those less tangible but deeply resonant elements — memory, narrative, identity — that bind people to place?”

Words by Amy Thompson

Stone, for example, can express permanence, weight, and deep geological time. Its textures and mineral compositions speak of the land from which it was extracted, and its weathering over time can reinforce the sense of a landscape that is alive, ageing, and evolving. Rough, uncut stone may evoke the rawness of nature, while precisely cut or polished stone might suggest ceremony or reverence. The choice between them is never purely aesthetic — it’s laden with meaning.

Timber, by contrast, can convey warmth, tactility, and a connection to human scale and touch. Its grain can evoke a link to the oncegrowing tree and its susceptibility to wear and decay, which, if untreated, remind us of impermanence. Reclaimed wood, in particular, carries traces of previous use — inviting reflection on cycles of reuse and transformation.

Weathering steels like Corten patinate over time, becoming more textured as they are exposed to the elements. This weathering can be seen as a gesture of temporal marking — allowing the material itself to record time and environmental change. Polished metals, on the other hand, may signify precision and control. When metals are etched, punctured, or layered, they can begin to hold shadow,

light, and trace in ways that suggest absence or reveal what is hidden.

Materiality is not just what a space looks like; it is how a space feels, how it changes, and how it communicates. Through wear, patina, and interaction, materials accumulate stories and hold memory. They are the physical interface between people and place.

Sustainable landscape design is about injecting meaning at every turn, from the material use to the structure. In this way, you create spaces that are weighted with the stories of the past and hold space for the stories of the future.

Together, Architects, Designers, and Chefs Plate a More Sustainable Dish

“Selassie finds her approach overlapping more and more with architecture — grounded in respect for the land from which the produce originates.”

If you’re looking for ginger and smoked cream truffles infused with Ghanaian cocoa or sesame soup that tastes of Accra, Chef Selassie Adatika knows how. When Yale Hospitality invited her, she made vegan bobotie, a South African favourite, keeping the homesick student in mind. In embracing the continent’s cuisine, Selassie describes her philosophy, New African Cuisine, as an intersection of environment, economy, and sustainability.

Increasingly, Selassie finds her approach overlapping with architecture — grounded in respect for the land from which the produce originates. She says: ‘For me, it’s about reimagining how we eat and redesigning food systems... When we eat what grows locally, we honour the land and its seasons. When we support local producers, we strengthen local economies.’ Her work is grounded in traditional practices: ‘communal dining, plantforward cooking, ancient grains, and wild or foraged ingredients.’

Slowing down

Culinary designers Martin Kullik and Jouw Wijnsma, the founders of Steinbeisser, curate nomadic gastronomic experiences that challenge our eating habits through tableware that forces diners to break conventions. ‘Eating tools have a major impact on the way we behave and interact with each other. We use tools that have been crafted to contribute to a more mindful experience,’ Martin explains. ‘By using pieces that are visually unique and slightly impractical, we tend to eat more slowly but the tools also help us overcome a certain social rigidity due to a range of etiquette rules.’ Attendees are often led to feed each other using extra-long spoons and bond over the challenge of eating with unusual utensils.

Each iteration alternates chefs, location, and artists who are commissioned to produce the tableware. But this collaboration with chefs Selassie Atadika and Elif Oskan in Dornach, Switzerland was particularly special: ‘The Goetheanum is the centre of the anthroposophical movement and also the homebase of the School of Spiritual Science,’ says Martin. The institution’s agricultural section celebrated its 100th anniversary of biodynamic farming in the same year as the culinary event. Explaining that Steinbeisser has worked with biodynamic farmers from their inception, Martin remarks that the celebration of this anniversary was particularly meaningful.

For Selassie, the Goetheanum's offering brought a natural symbiosis of her Ghanaian heritage and biodynamic Swiss ingredients: ‘African cuisines have long relied on plant proteins like nuts, seeds, legumes, and pulses,’ she says. ‘I treated each ingredient with respect, pairing it with Ghanaian techniques and flavours like egusi (wild melon seeds), shito (a deeply spiced chili paste), and groundnuts. This allowed me to honour the terroir of the Goetheanum while carrying my own culinary heritage into the experience.’

While Steinbeisser's early years saw conventional materials used for tableware, like ceramics, glass, and metal, they have renewed their commitment to more experimental, biodegradable substances such as storm wood, flax, fungi, seaweed, and even paper. In their 2024 iteration, one such item was a large-scale wooden dish, made for sharing and composed of storm wood

sourced from trees that have been felled by a passing storm. By 2026, they expect to complete the transition to renewables — not only for the tableware but also for drinking vessels, which Martin says poses the biggest challenge.

For the chef that has to plate these experimental, and at times challenging, forms, it is a creation forged between edible and inanimate artistry. ‘Plating, for me, is storytelling,’ says Selassie. ‘With Steinbeisser’s experimental tableware, each plate became an extension of the narrative, a sculptural element that elevated how diners experienced the food.’ In designing the second course, Egusi Galette, Gari, Seasonal Salad, and Berry Vinaigrette, Selassie chose to match the coarse textures of the gari with a light-grain vessel. The course that followed contained a dish peeling and shedding like bark in the woods; the forest-like setting enclosed roasted mushrooms and a smooth groundnut sauce — forming a cohesive, earthy feel to the dish.

“Steinbeisser has renewed their commitment to tableware made from more experimental, biodegradable substances such as storm wood, flax, fungi, seaweed, and even paper.”

Frederik Labuschagne’s architecture-gastronomy crossover is somewhat like Chef Selassie’s in reverse: he’s a graduate from the University of Pretoria’s Architecture School turned plant-based chef since launching his restaurant, Plant., in Lucerne.

‘I approached this career change like any architectural project: methodically and with clear intentions. I wanted to be both the architect and the client of my own vision,’ Frederik says. ‘To build the necessary foundation, I gained hands-on experience working in a restaurant, which not only taught me the practical aspects of the industry but also gave me the confidence to launch my own venture.’

A feeling that lingers

Since moving to Switzerland with his family in 2018, Frederik reignited his lifelong passion for culinary traditions and techniques. A new start in a new country prompted the journey into untapped terrain. The connection between architecture and gastronomy was stunning: for Frederik, ‘both disciplines are fundamentally about creating experiences that engage multiple senses and emotions.’ While an architect curates the approach and movement through space, the chef is responsible for ‘a sensory journey from the first visual impression of a dish to the final lingering taste’. The same principles — balance, proportion, texture, colour — infiltrate both realms of curation.

His 22-seater, plant-based restaurant is an intimate experience that brings diners closer to understanding what they eat. It centres around his philosophy of ‘intentional consumption’ and questioning the status quo. The smaller scale allows the restaurant to remain authentically ‘sustainable’: reducing their ecological footprint, surrendering to the rhythm of seasonal produce, and sourcing local ingredients.

Umami

Hara Hachi Bu (腹八分目), which translates to eat until you’re 80% full, is an exercise of moderation. Japanese philosophies, particularly that of minimalism and mindfulness — ‘the idea that we should eat more focused, more deliberately’ — are embedded in Frederik’s approach. What he refers to as the ‘less but better principle’ can be seen throughout the restaurant: in their small menu and elimination of food waste.

But Japanese influences extend beyond the conceptual: the Plant. team produce their very own miso, koji, umeboshi, and kimchi served during the dining experience or available to take home. Describing the fermentation process as an ‘alchemy’ to ‘develop deep umami flavours’, Frederik displays his research-led curiosity that drives his richly flavoured plant-based offering.

The architecture of community

Situated within a heritage-protected building, the restaurant’s bar and kitchen area demanded gruelling renovations that both complied with regulations and remained appropriate for modern dining.

Now, its walls are a soothing green, and the low, warm glow emitted by the paper lanterns creates an intimate feel — intentionally chosen to push back against the grand volume induced by the high ceilings. In the evening, this ‘gentle illumination spills onto the street’ says Frederik whose architectural background equipped him with strategic spatial thinking needed to set up the space.

Stainless steel is easy to clean and creates a neutral aesthetic against which the food remains the protagonist, while the solid wood furniture, minimal and enduring, manifests the architect’s faithfulness to longevity. On these seats, regular diners have become, in Frederik’s words, extended family.

Shaakira

Jassat, Founder of Studio Sway, Channels

Creative Scientific Research, Radical Empathy, and Memory for Design That Renews

What do blood, feces, and urine have to do with architecture? Everything, apparently. The body, food, and waste are part of an entangled system of intimacy and memory, of production and violence. They are part of everyday practices, mediated by our learnt behaviours and by the objects that give way to our desire to consume and entertain. For Shaakira Jassat, interior architect and founder of Studio Sway, even the most repulsive states and elusive memories are part of the act of creation. ‘How do we bring back things that we've forgotten, that we've overlooked?’ Shaakira asks.

She’s visited tea farms in Sri Lanka and slaughterhouses in the Netherlands; she’s conjured tableware that resurfaces the culinary landscapes of her childhood, and she’s donned a lab coat as she uses Sporosarcina pasteurii to turn beetroot and spinach into potentially usable materials. All of this is driven by an understanding that our everyday rituals are intimate forms of life: change their architecture, and you change the fabric of our ecosystem.

Intimate encounters

'My father had this art of holding a tea saucer with one hand and just lifting it to his mouth to drink his tea. You could see the tea before you and smell it better this way, ensuring you get the full tea experience. He had to find ways to adapt his ritual to Western teaware, and I thought it was a really striking memory,' says Shaakira. Unlike the individualist nature of Western eating patterns, Eastern cultures centre meals around community. ‘With us, it's really an event. When I was young, we were like 10 people around

the table every night,’ she explains. Uncovering these memories is as much a part of sustainability, recalling in to order to preserve.

Familiar Forms, one of her latest collections, features tableware inspired by her Indian heritage, South African identity, and migratory state as she now lives in the Netherlands. Holding this cup brings an intimate connection to the homeland: like damp sand, their colours speak and smell of the African landscape. Their shapes tell the stories of transition: using an extruder, the clay was forced through a shape and the protrusions altered by hand — all point to movement, to the oceanic journey Shaakira’s grandparents undertook from India to South Africa, adapting and morphing.

Glazing, a rather technical decision, is laden with implications. As it stands, the red soil cup allows your lips to touch the rough stone, raw and grainy earth. ‘When you pour water into it, the clay also changes and it reminds you of a South African riverbed,’ Shaakira

explains. But Indian food can be oily, and without glazing it could become difficult to clean. After several studies, Shaakira chose to glaze only the inside of the plate, ensuring it is functional but that the textures of the African landscape remain exposed at its sides.

Sometimes the ritual is greater than what we can immediately see. Shaakira, fully aware of our disconnection from sources of production, visited tea farms in Sri Lanka as part of her design research. She found epic machines where tea leaves were blown, their moisture drawn out, and leaves dried. Conceptually, Shaakira sought to bring back the evaporated water to the teacup.

Tea Drop advances a known scientific mechanism, utilising phase change to absorb moisture from the surrounding environment and condense it into a water drop — all made possible by the fan, cooling and heating elements. The heating-cooling pattern that prompts condensation is a scientific cycle of its own — a ritual even the smallest particles partake in. The process is slow. It is an invitation to pause, to remember that this vapour is returning to the teapot while the process-in-reverse continues at the farms in South Asia.

A similar principle is employed in her Aquatecture project, a vertical water harvesting panel for urban areas, which too began with both scientific research and a desire for connection: the Namib Desert Beetle and Tillandsia plant species are physiologically structured to harvest water from the air and were steady companions in the early research stages.

On the other hand, her second source point — slaughterhouses — were places of trauma where Shaakira witnessed cows being stunned and killed mechanically. How, then, to break this line of production? How can we become more connected to the source of our consumption? Empathy. Radical empathy. In employing a methodology of connection in her practice — to food, to the animal other — Shaakira teaches through experience. In her second-year classes at the Design Academy Eindhoven, one of the assignments, In Your Shoes, requires students to physically embody their chosen persona: chickens, urban bats, and even a cow on its way to slaughter. Empathy exercises, like role playing, encourage students out of their comfort zone, disrupting the ordinary chain of events, the disconnection from the source, and, most importantly, altering their relationship to the subject matter. A bat impersonator may keep out their sight and tune into the possibility of echolocation as communication. This is followed by analysis to reveal design guidelines. ‘At first they find it really strange. Like, why do I have to do this? Why do I have to act weird?’ Shaakira comments. But, slowly, something changes.

The fullness of the ritual is its recognition of the beginning. It is the final water drop, transformed from vapour, dripping into the teacup. From Sri Lanka to the Netherlands, the ritual is complete.

The end is the beginning Her exploration of biomaterials has occurred in several iterations. The first, Body Mining, harvested bodily waste — hair, nails, and other waste — processing these and testing them as additives to porcelain.

In a recent iteration of her creative experimentation with organic matter, Shaakira tests the potential of eggshells, spinach, oyster shells, rice husks amongst other substances. Sporosarcina pasteurii is wellresearched and even used in experiments to harden sand with urine, turning it into bricks. Based in a lab in the Netherlands, she experiments with combining waste and organic streams, assessing their performance and creating new materials.

Shell_ter, it’s called. It breathes life at the end of the ritual. What is forgotten at the end of one ceremony becomes part of the next.

“'Isn't the egg an amazing piece of architecture? A hard protective shell with life forming within. Built by the chicken within its own body. There are secrets waiting to be unveiled in the unseeming rituals all around us, and these secrets carry massive potential for the design of our future,' says Shaakira.”

Waterway House, Canal District, V&A Waterfront, Cape Town, 8002 T. +27 (0)21 419 5445 E. info@domum.co.za

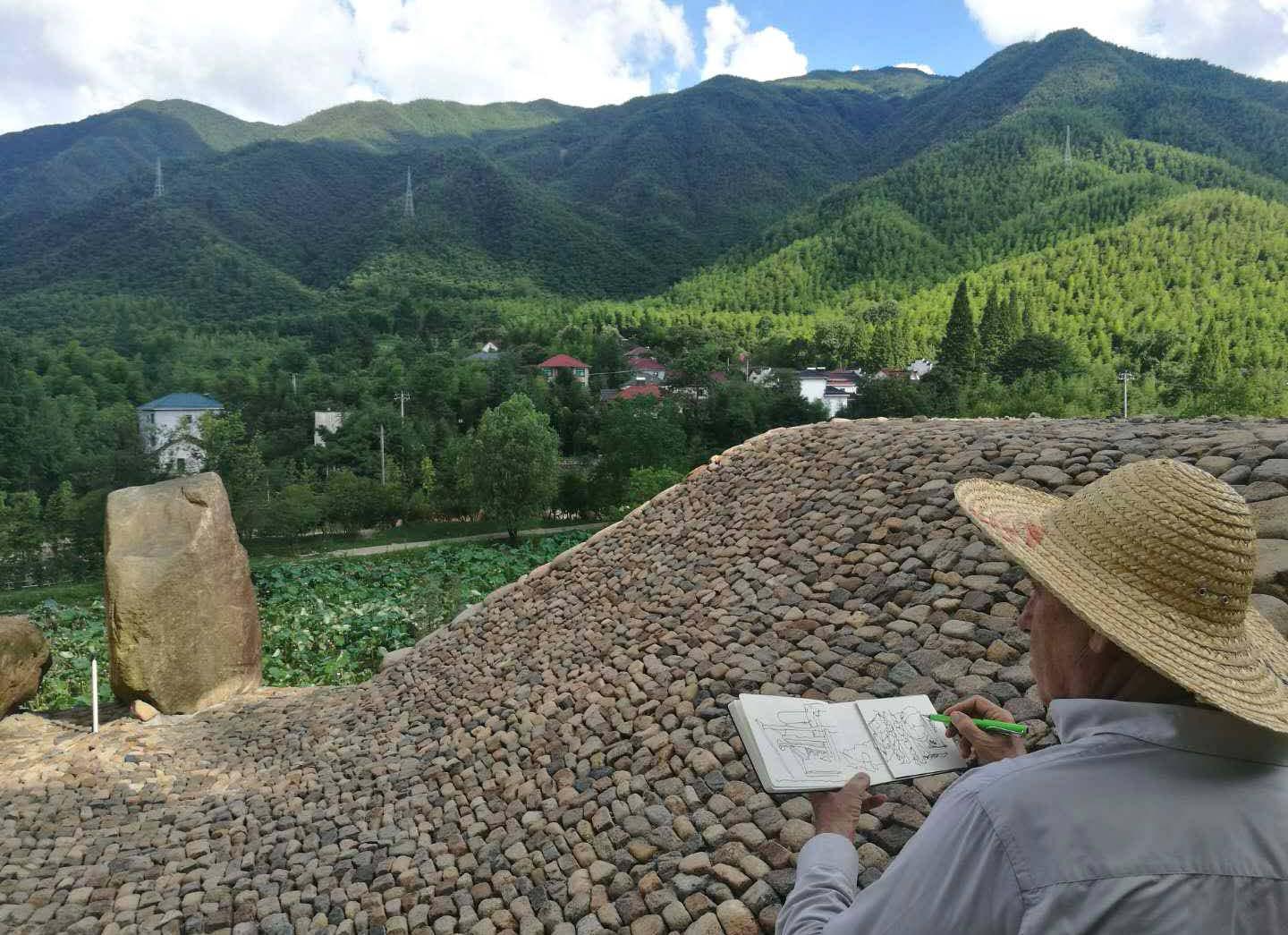

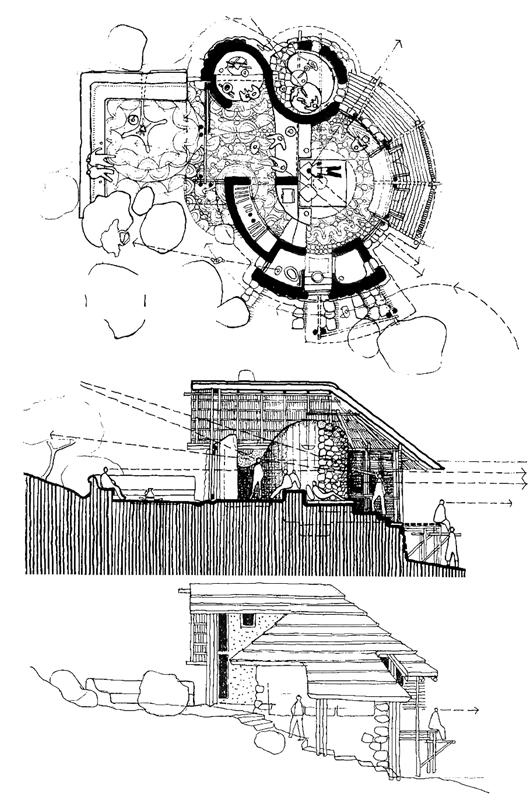

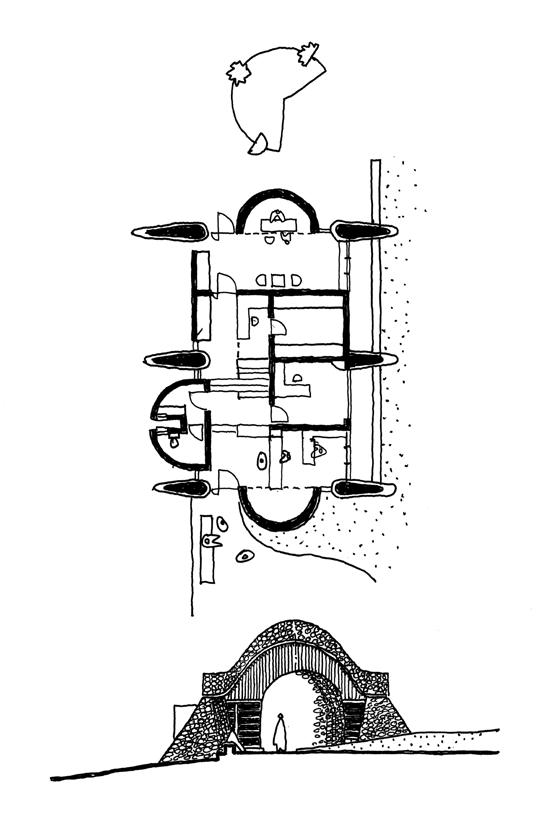

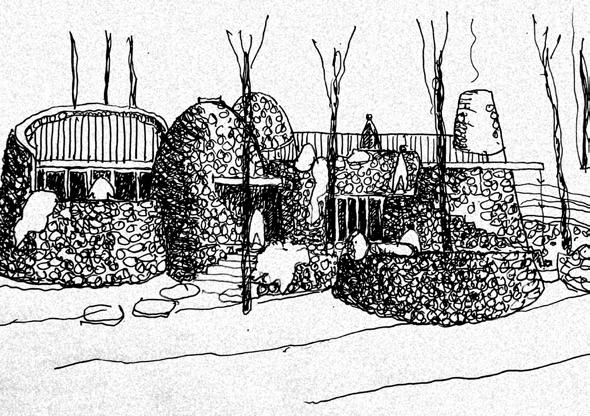

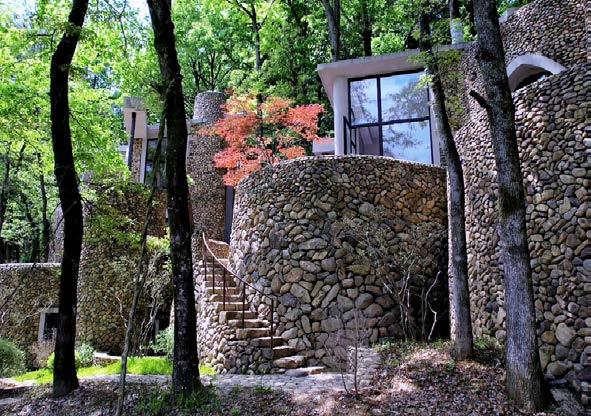

Professor Nicholas Coetzer on The Architecture of Peter Rich: Conversations with Africa

In 1893, Mahatma Gandhi was thrown off a ‘whites only’ train carriage outside Pietermaritzburg in South Africa. There is so much complexity held in that horrible act, for example, the displacement of people in the realm of the British Empire, the complexities of identity (of who is white or Indian or African for that matter), of what the British did with their trains and law and lawyering and how that set things on a certain course of interruption, that to be ‘thrown off’ is also to be ‘thrown together’.

I mention this not only because Peter Rich has become a friend of India and India has become a friend of Peter Rich — indeed, Jonathan Noble’s The Architecture of Peter Rich: Conversations with Africa, starts with a foreword by (Balkrishna) Doshi and five pages in already has Rich’s intense and powerful drawings of Ahmedabad and Ghanpur Temple demanding attention. But Gandhi’s ‘thrown off’ is also our ‘thrown together’— in the remnants of the British Empire, the simplistic divisive binary narratives of who is and who isn’t allowed and who should and who shouldn’t deny the complex reality of our world. The key word here is conversations — that points to an exchange of ideas, an interaction that shifts meaning.

Indeed, apart from Pancho Guedes, the maverick Mozambican architect and teacher, Rich’s architectural life — and indeed Noble’s book — starts the conversation with the Ndebele, a ‘tribe’ who adapted their vernacular architecture in the process of partial assimilation to Boer/Afrikaner they were being indentured to at the time Gandhi was being introduced to the brutality of racism. This simple initiating act in both Rich’s life and the chronological order of Noble’s book alleviates the all too ponderous demand to explain why a ‘white man’ should be allowed to appropriate African architecture. Noble never mentions it, or investigates it, because it is already answered by the Ndebele themselves. We are all thrown together, conversing, borrowing, seeking, adapting, inventing. The second sentence of the book is a quote that explains Rich’s

ethos: ‘An Ndebele woman said to me, ‘we see what we want to see and we make it our own,’ and that is everything.’ Indeed, the first few chapters of the book make for a fascinating reading of how Rich’s analysis and research into the Ndebele combined with a reworking of Adolf Loos’s raumplan theory into Rich’s own house in Johannesburg and subsequent house designs around South Africa. The complex play of an implied diagonal set against the dominance of an axial symmetry is beautifully explored by Rich and brilliantly explained by Noble as an example of ‘making it our own’. The ‘conversation’ continues with Rich’s most famous and iconic building, the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre, located at the pinch-point meeting of South Africa, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. My students at the University of Cape Town revere it as evidence of — finally! — an African architecture suitably valorised and celebrated. But the truth is, the project is a hybrid of African terrain and locale and formal language meeting vernacular Spanish timbrel vaults via an expat South African working in England, called Issy Benjamin, who is most famous for his Brazilian Moderne reworking of Durban’s beachfront hotels! The world is truly a wonderful and rich place full of fascinating opportunity. And that’s the point I think Noble makes in his book about the architecture of Peter Rich; he is always open to opportunity, to using useful ideas, to grabbing hold of creative spirit as it manifests and not problematising or over-determining it. The battle and courage to stay true to this cannot be

By

overemphasised. Everything in South Africa is contested — meaning, politicised and hence potentially undone — and it requires a resolute self-belief and adherence to the needs of the project and its architecture. Noble occasionally surfaces the vitality and charisma of Peter Rich as necessary in driving architecture of this kind in this context, and hints at Rich’s formative years as a possible source of his determination to overcome negativity and the limiting restrictions of ‘who can and who can’t’ . Indeed, anyone who has met Peter Rich will never forget him. His direct manner and candid tone can be abrasive to some but endears him to people who cannot suffer fools, and are willing to allow an artist to take hold and drive a project to the full extent of what it needs. This aspect is noted by Noble in the most recent work Rich is doing in Wu Shan, China and his collaboration with his maverick client, Weiping Jin, particularly through the common language of drawing and over internet WeChat hand gestures of thumbs up or down.

In compiling this rich book, Noble spent five years and 40 hours of interviews and many more hours tracking down or making key

drawings. Consequently, there is lots in it for all kinds of readers, from those catching some interesting biographical stories to those concerned with the chronological evolution of Rich’s work (although urban design and social housing projects are not included in this study). It is also a catalogue of some 80 exquisite black-line hand drawings (Rich’s drawings for the Kanniedood centre was an instrumental drawing that promoted Rich’s work to the 2018 Venice Biennale). The Architecture of Peter Rich is also illustrated by 43 colour plates ranging from Ndebele beadwork to Rich’s paintings, to photographs of Rich’s buildings, some of which were specifically commissioned for the book itself. However, notwithstanding the abundance of visual delight, Noble’s book reminds us what it is to be an architect beyond the staging of a facile scenography that clocks up ‘likes’. And all the while to make something powerful, engaging, and beautiful. Here then, are some beautiful things, not just in the buildings and drawings of Peter Rich — obviously so — but in the beautiful engagement of this complex oeuvre in Noble’s writing and the beautiful thing that this book is.

by Jonathan Noble

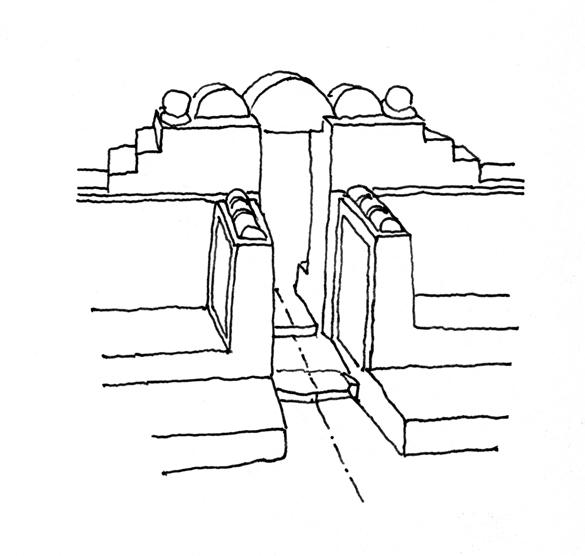

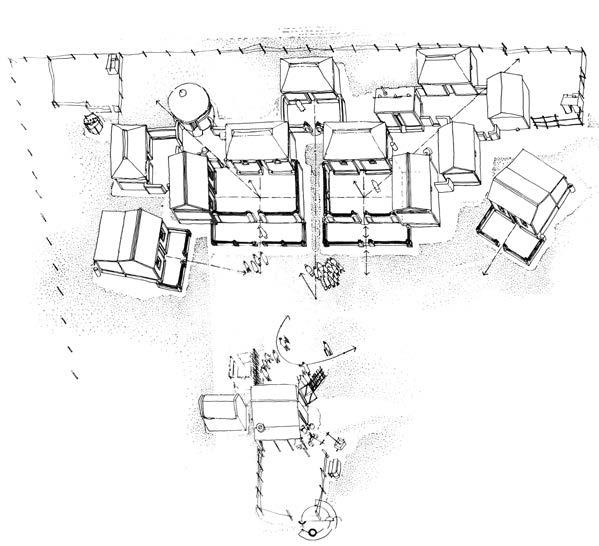

Ndebele Homesteads

From 1974 until the early 1980s, Rich studied and documented a large number of homesteads, situated on Boer farms within a 115 km radius roughly centred some 25km north of Witbank, of which eight were selected for inclusion in his master’s dissertation. Figure 2.2 shows the measured drawing that Rich made of the ‘Circular Palace’. When he discovered this homestead in 1977, some 37 km north-west of Middleburg, the buildings were in a dilapidated state, having been unattended for some years. The former occupants, Mtsweni and Henshop Makasoke, had died in 1974, having lived here since 1950. The abandonment of a homestead is in keeping with Ndebele custom, because the dwelling of the deceased is considered sacrosanct. Such homesteads are not demolished, but rather are left to decay, slowly re-uniting with the natural landscape from which the sapling, grass and mud structures were once made.

Here we see the basic configuration of post-1940s Ndebele architecture. A central dwelling of the so-called ‘cone-on-cylinder’ type – a circular plan with conical roof – it has outdoor walls that reach out to form courtyards at the front, the rear and the sides. Additional one-room pavilions are attached to the courtyard walls to form a patchwork of enclosed and outdoor spaces. The alternating pattern of indoor/outdoor space is a primary feature of Ndebele architecture. It is crucial to appreciate that, thanks to a warm climate, African living takes place outdoors and that the courtyards are really outdoor living rooms. Hence the forecourt provides a common outdoor room fronting and connecting the circular dwelling and the pair of rectangular pavilions that are

positioned to either side. The circular dwelling would have served as an indoor sleeping and living space for Henshop and his wife, whilst the side pavilions would have accommodated his children. The rear court is divided into two, the left portion of which would have served as a kitchen. The doorway into the side of the main circular dwelling positioned here, would have allowed for food preparation, alternatively on the inside or in the yard depending upon the weather. The further smaller court and its pair of circular pavilions, positioned to the right, would likely have been added at a subsequent time.

The architecture is ordered with a frontal, bilateral symmetry and a sequential layering of space. The front wall of the complex is richly decorated with a ‘massive central sculpted portal’ and fertility dolllike sculptures, positioned at either end (see figure 2.3). A stepped plinth raises a pair of seating areas on the thickened, external front

wall. The central opening is announced by a pair of transverse walls that frame the entrance between the seating areas on either side. A sculpted ‘gable’, formed from a symmetry of steps, ball-onpedestal and three half round motifs placed to either side, spans over to celebrate the entrance way. And two steps up lead the path into the forecourt. The central axis of symmetry, framed by the presence of two side pavilions, focuses upon the circular dwelling, which is approached via a veranda-like fore-space, with low fronting walls that step in profile to echo the sculpted front ‘gable’. Axial entry into the main dwelling is again celebrated, this time via an embellished doorway. The dwelling shows a bilateral symmetry, with radial side rooms and a raised umsamo (seat intended for the ancestors) placed to the centre-rear of the interior. Finally, the pair of courts at the back complete this orchestrated layering of space.

Find out more at Lund Humphries.

Marc Sherratt Architects is a research-led, impact-driven practice. Having designed one of the first net-zero certified buildings on the continent, founder and architect Marc Sherratt designs for people and the environment in equal measure.

How is the use of sustainable materials evolving in the industry?

The focus has shifted to addressing embodied carbon — the emissions tied to mining, manufacturing, transport, construction, and end-of-life of materials. In South Africa, cost remains the main driver, but in the EU, reusing buildings is prioritised. Where new construction is necessary, the goal is to use material combinations with the lowest embodied carbon. These decisions are guided by data via Whole Life Carbon Assessments (WLCAs), with the UK’s RICS Version 2 being the current best practice. Reducing carbon begins with the structure, then the envelope. Making use of performance software like One Click LCA helps us measure carbon early and encourages local sourcing.

What new approaches to sustainable materials are you exploring?

In Zambia, we’ve used tree bark waste from FSC-certified forests as cladding and reclaimed steel. Rather than outlawing hardwood, we’re working on a system to formalise its use, ensuring economic and ecological responsibility while training local labour in innovative building techniques.

We’re also producing Hydraform bricks from construction waste. With research and creativity, there are always opportunities to

transform what would otherwise be left in a landfill into meaningful design elements.

Where do you draw inspiration from for sustainable design?

We study local vernacular architecture and observe how native wildlife adapts to the environment. There’s deep wisdom in what’s already there.

We start by asking: when is the building used? In rural areas, vernacular buildings separate functions by time of day. We apply a similar logic, supported by climate modelling. Fabric-first design, appropriate insulation, thermal mass, and orientation come first — ventilation then follows. If a project needs air-conditioning, we consider that a design failure (with exceptions like medical spaces).

‘Architecture with a conscience’ according to Gillian Holl

Founder and lead architect of Veld Architects, Gillian Holl, champions what she calls ‘architecture with a conscience’. Dedicated to sustainability, she speaks to the importance of working with nature for relevant, cohesive design.

Which design strategies are central to your practice?

Passive design is fundamental to our work. We prioritise natural ventilation through cross breezes and manage solar exposure using extended overhangs, screens, brise-soleils, and blinds.

We also integrate landscape as a design tool. Indigenous plants foster biodiversity and ground the building in its context. In cities, roof gardens support rewilding while improving insulation and thermal performance. It’s all about aligning with nature — not overpowering it. Ultimately, our approach to sustainability is about co-existing with nature, respecting its rhythms, and designing in dialogue with the land.

What are some low-impact materials you frequently use?

Clay brick is a go-to material. Its appeal lies in its durability, longevity, and low embodied energy. Made from natural, locally sourced materials like clay, sand, and water, it aligns with our sustainability goals while offering long-term performance. We particularly value its thermal mass — its ability to absorb and release heat slowly, which helps regulate indoor temperatures and reduce the need for active heating and cooling. We also appreciate the aesthetic and longevity of flush-jointed, colour-matched pointing, where the mortar is tinted to match the brick tone. This detail results in a monolithic, refined finish with enduring visual appeal. Despite some misconceptions around face brick in contemporary design, we find it timeless — efficient, expressive, and deeply sustainable.

We study the landscape, the movement of light, the path of wind. Sun orientation, topography, and breeze patterns become guiding elements. This informed yet intuitive approach underpins our passive strategies and grounds the design in place. It’s how sustainability becomes second nature.

"Clay

brick is a go-to material. Its appeal lies in its durability, longevity, and low embodied energy."

Known for his creative, experimental, and, at times, unconventional approach, Gregory Katz is notorious for delivering visual playfulness. We spoke to him to learn more about the techniques and materials that go into designing spaces that are resilient and timeless.

What is your firm’s philosophy on sustainability?

At GKA, roof design is a key focus as it integrates multiple sustainability variables and can transform how a building performs. In our Wing-Wing House project, we used a flat concrete roof despite concrete’s high CO2 emissions. To address this, we incorporated Penetron, a crystalline waterproofing additive that removes the need for traditional membranes. We then installed a soil bed with indigenous, waterwise grasses directly on the slab. This insulates and harvests rainwater for toilet cisterns. Reinforced concrete allowed for efficient spans and fewer material layers by pouring concrete with a fall and omitting the screed layer. The result is an insulated green roof with panoramic views and space for a solar farm.

How do you understand your role, as an architect, towards our society’s pressured resources?

Material production is incredibly energy intensive. Around 40% of global CO2 emissions come from the construction industry — cement, brick, steel, and aluminium are major contributors. There’s now a strong push within the industry to find alternatives that are less harmful to the environment. Timber and stone are examples of materials touted for their carbon sequestering properties.

Other key approaches include reducing material quantities through efficient structural design and stripping back the layers of materials that are applied to buildings while enhancing performance with proper insulation. Again, roof design remains a critical focus for us. Integrating thermal performance, water collection, structural efficiency, and biodiversity into a single element can transform how a building performs over its lifespan.

Sustainability is the foundation, says Graeme Labe

Graeme Labe’s design philosophy is rooted in the belief that enriching spaces are those shaped with environmental consciousness and integrity. As managing partner and chief design officer for Luxury Frontiers, Graeme speaks to designing spaces that exist in conversation with the natural surroundings.

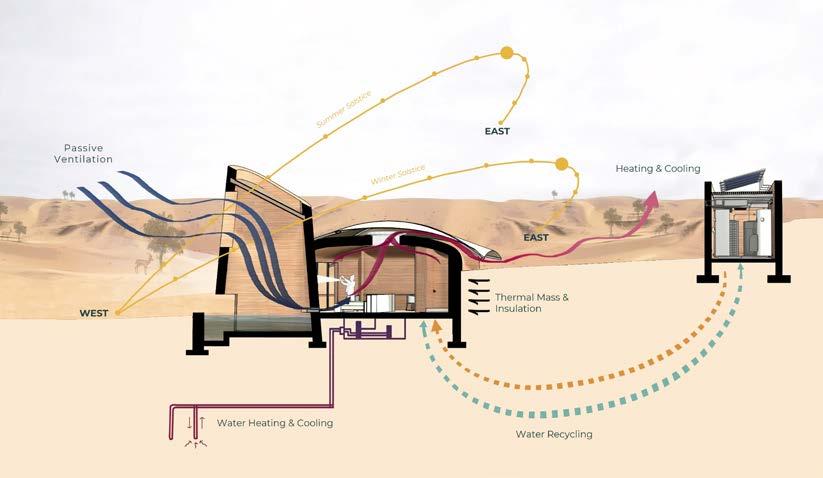

What is true sustainability for you?

Sustainability isn’t something we add later; it’s embedded from the start. It’s not a checklist or aesthetic choice, but a guiding principle. It shapes how we respond to place, climate, and community. We consider more than the physical site. We pay careful attention to the social and cultural context as well. True sustainability doesn’t stop at solar orientation or ventilation — it’s about understanding the full story of a place and designing with care.

And what does that care look like?

Our process begins with listening. The land reveals itself — light, shadow, wind, heat retained in stone. These clues shape the foundation of our work. Passive strategies are not a checklist, but a conversation between climate and structure.

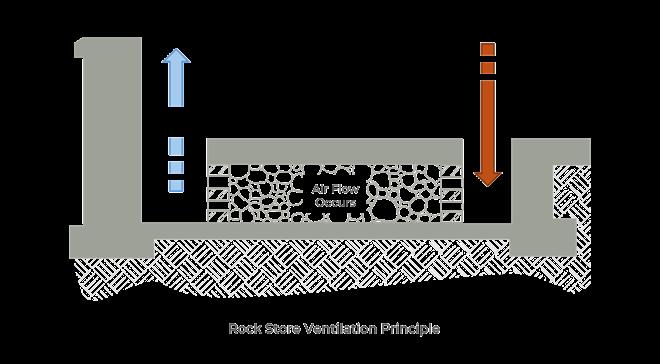

This dialogue is taking shape in a welcome pavilion for a project we’re currently working on in the Klein Karoo. Thick stone walls store and release heat, a planted roof provides shade and insulation, and orientation captures winter sun while blocking summer glare. Deep overhangs regulate light and comfort. At the heart of the building’s passive performance is a rock cooling system. This is an elemental

intervention grounded in ancient logic. Together, these systems respond to climate with quiet intelligence. The result is architecture that feels at ease in its setting.

Ancient knowledge seems to be woven into your work. Would you say this is true?

Inspiration begins with observation. One of our desert conservation projects integrates wind towers, sunken courtyards, and limited openings — drawing from regional vernaculars. Not to mimic, but to honour centuries of knowledge. This is how sustainability is remembered and reimagined.

“Inspiration begins with observation.”

Modern synthetic paints and sealers have made significant technological advances, but concerns over health, environmental impact, and sustainability have driven a growing shift toward natural solutions. Far from being a mere trend, the move to bio-based finishes reflects deeper ecological and technical considerations.

Natural coatings adhere to strict principles: avoiding petrochemical-based raw materials, ensuring environmental and biological compatibility, and using ingredients from renewable resources. Their manufacturing processes aim to be ecologically sound, with full transparency on ingredients.

Natural binders, mainly plant oils, differ from synthetic polymers. While synthetic binders offer fast drying and durability, they form surface-level films that lack deep substrate bonding, leading to cracking and peeling. In contrast, natural oils penetrate deeply and oxidise over time to form strong, flexible bonds providing breathable, non-toxic, biodegradable finishes.

Solvents in conventional wall, stone, and wood coatings, such as mineral turpentine, release carcinogenic aromatic hydrocarbons. Synthetic polymers also contain unreacted monomers (such as formaldehyde) and require plasticisers, both of which pose long-term health risks. Natural solvents like essential oils are

more compatible with the human body, having existed in our environment for millennia.

Synthetic pigments may still involve harmful heavy metals like lead or toxins in cobalt dryers, which are also serious health hazards. Mineral pigments are natural, inorganic substances, often used in art, cosmetics, and industrial applications. These ‘earth pigments’, derived from minerals, are known for their safety, durability, and historical use.

Additives in conventional paints like fungicides, insecticides, and odour-masking agents can emit destructive chemicals. Their necessity is often questionable, especially with today’s building standards and availability of non-toxic alternatives.

The eco-friendly future has already arrived

Ultimately, natural coatings provide healthier, biodegradable, and therefore ecologically sound finishes for most exterior and interior surfaces. They support long-term well-being and sustainability, proving that nature-based solutions are not a step backward but a meaningful advancement to eco-conscious times ahead.

Southern Africa’s only natural coatings manufacturer, ProNature, has pioneered this field for almost three decades, consistently applying the latest European technologies. It is achievable to paint a greener, more colourful future, and it’s time!

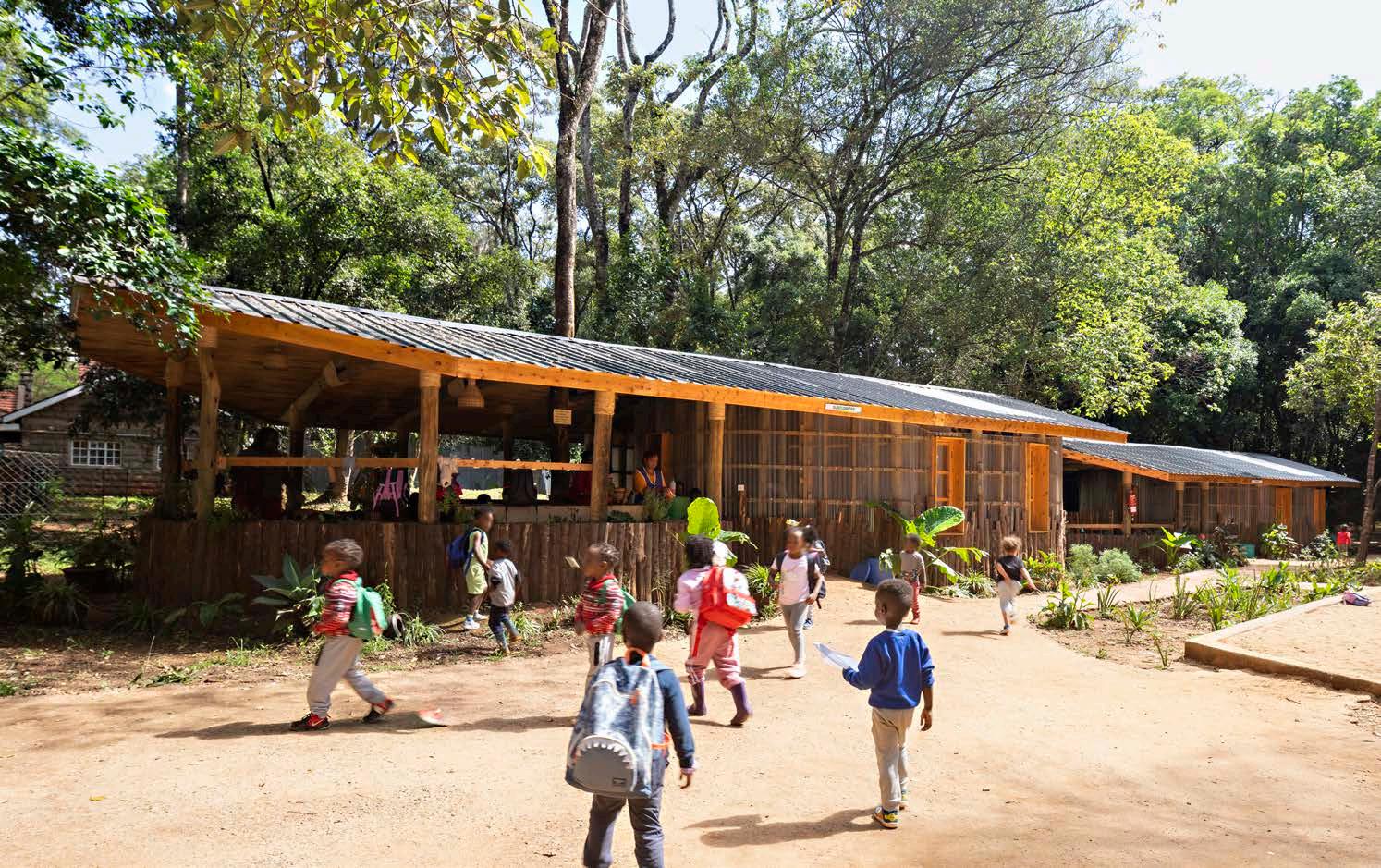

Urko Sanchez Architects Plots a Waldorf School Imbued With the Local Vernacular and Biodiversity

Conceptualised as ‘a village for kids hidden in the woods’, this Waldorf school in Nairobi exemplifies an approach that combines creativity, sustainability, and community involvement to create a truly unique learning space.

Designed by Urko Sanchez Architects, a firm based in Madrid and Nairobi, and commissioned by a local Waldorf school, the institution is deeply connected to nature and grounded in Anthroposophy. This philosophy, conceived by Austrian educator Rudolf Steiner, lays the groundwork for what makes Waldorf schools different: these institutions thrive on a learning process rooted in three dimensions — thinking (head), feeling (heart), doing (hands). Anthroposophy sees the physical and spiritual world as inherently connected, bringing a holistic approach to understand the world. Learners are exposed to academic, artistic, and practical skills.

Location: Karen, Nairobi

Size: 71 m2

Living walls

The concept was to create a small village for children nestled within the woods, preserving the old house on-site to accommodate additional classrooms and services. The plot of land is situated within a forest, rich with native tree species, and the goal was to integrate the school harmoniously into the natural environment. To achieve this, classrooms were designed as a dispersed town, strategically placed in clearings within the forest.

The classrooms have soft and organic shapes, with a spiral configuration, inspired by the Maasai Manyatta and other Kenyan vernacular architectures. A traditional Maasai home is oval-shaped, constructed from mud, sticks, grass, and cow dung. Its rounded form optimises structural stability, conserves warmth, and reflects the community’s connection to nature. This vernacular architecture blends functionality with cultural heritage and simplicity.

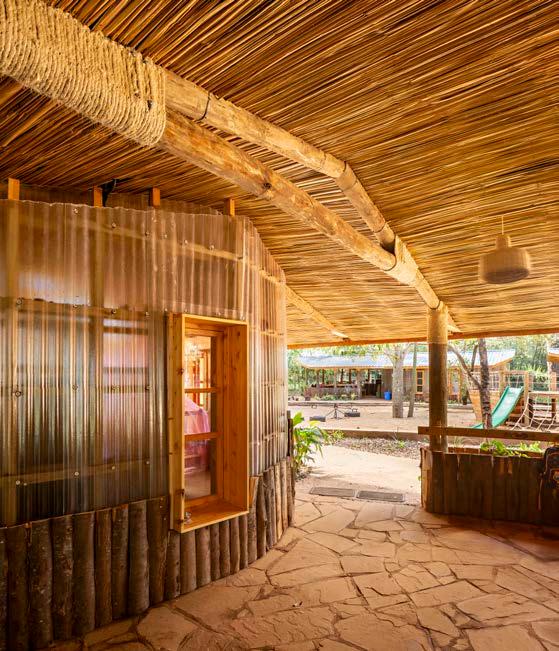

To enhance the bond between students and nature, Urko Sanchez Architects introduced ‘living walls’. While schools ordinarily function as long-term investments, this one is set to have a temporary lifespan as the plot lease expires in 10 years. The buildings needed to be constructed both quickly and cost-effectively. In the end, Urko Sanchez Architects achieved a cost of 250$/m². Considering the project’s ephemeral nature, the walls were constructed by filling the space between two polycarbonate sheets with leftover soil from excavations and a second layer of forest leaves.

MEET THE TEAM

Urko Sanchez

This innovative technique met the client's need for speed and costefficiency while offering a unique aesthetic. The polycarbonate’s transparency reveals the dynamic life within the walls — ants, bugs, plants, roots — and reflects natural light and colours into the classrooms. These evolving living walls transform the classrooms into vibrant, active environments, encouraging students to observe biodiversity up close.

The construction system was designed to be adaptable and community-driven, engaging children, parents, and teachers in the process. Whenever possible, materials from dismantled classrooms were recycled and repurposed: wooden floors and walls became parapets, and roof tiles were transformed into path boundaries. Oil drums were upcycled into toilet sinks, while tree trunks — removed to clear space for sports fields before engaging the architects — were creatively used as screens in the dining hall. An old shipping container from the previous school grounds was relocated and adapted into the new school library. Additionally, soil was mixed into classroom slabs and concrete pathways to minimise the use of cement and external aggregates, promoting a more sustainable approach.

The Waldorf School ultimately gives new life — to thought, to being, and to the built environment.

Refreshing your indoor space doesn’t have to mean a complete overhaul. With the right materials, you can achieve a dramatic transformation that enhances both aesthetics and functionality — all while being easy to install. Eva-Last’s TIER flooring, Revive Castellated Cladding, and Lifespan architectural beams offer stylish, sustainable, and easy-to-install solutions that instantly update any interior.

Whether you’re renovating a residential project, modernising a commercial space, or simply revitalising a single room, Eva-Last products are designed to meet your lifestyle and project needs. Their eco-friendliness, endurance, and classic appeal make them the savvy choice for dynamic designers, architects, and homeowners alike.

Upgrade floors with TIER

Flooring sets the foundation for any space, and TIER flooring makes it easy to achieve a high-end look with minimal maintenance and a superior, sound-dampening feel underfoot. Its water- and scratchresistant properties make it perfect for any room, including offices, hospitality venues, modern homes, and even bathrooms. Choose from a range of realistic wood-inspired finishes to create a warm, inviting atmosphere without the upkeep of traditional hardwood. And it’s completely safe, guaranteeing safe indoor air quality, free from Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs).

Whether you’re working with professionals or embarking on a DIY project, the ease and efficiency of TIER flooring make it the go-to choice for modern interior revamps.

Create a striking feature wall with Revive

Adding a feature wall is one of the simplest ways to refresh an indoor space. Revive Castellated Cladding offers a hassle-free way to introduce texture and character to any room. Whether you want a bold statement wall in a commercial lobby or a subtle, natural aesthetic in a cosy lounge, Revive delivers a timeless look with durability to match.

Its unique profile creates depth and dimension, turning an ordinary wall into a design highlight. Crafted to withstand wear and tear, Revive offers lasting beauty with minimal effort and upkeep.

Define spaces with Lifespan architectural beams

Open-plan layouts are popular, but sometimes, a little extra detail goes a long way. Using Lifespan architectural beams as privacy screens, for example, provides an elegant way to divide spaces without completely closing them off. Use them in offices to create semi-private work areas or in hospitality settings to add stylish zoning that maintains an open, airy feel.

These lightweight beams are not only easy to handle and install, but they also keep from warping, cracking, and weathering — guaranteeing that your design stays stylish and intact for years to come. With Eva-Last’s premium materials, transforming your indoor space has never been easier. Whether you’re refreshing a single room or revamping an entire commercial space, these solutions offer beauty, durability, and sustainability in one simple upgrade. Looking for inspiration? Get in touch with our team to explore the possibilities.

A Contemporary Reinterpretation of the Traditional Farmhouse Combines Rural Simplicity With Modern Ease in Cape Town’s Leafy Southern Suburbs

in the leafy folds of Cape Town’s Southern Suburbs, Farmhouse Constantia, a collaboration between JNA Group and Kritzinger Architects, offers an elegant yet relaxed take on the traditional farmhouse.

Reimagined for contemporary family living, the design of this five-bedroom home is shaped by a strong connection to its landscape, a communicative material palette, and an architecture that embraces earthiness and bounty.

Location: Constantia, Cape Town

Photographer: Karl Rogers

“The design of this five-bedroom home is shaped by a strong connection to its landscape, a communicative material palette, and an architecture that embraces earthiness and bounty.”

Movement through the landscape

Set within a private estate in Constantia, the home follows rhythms of the land. A natural pool reflects the sky and surrounding trees, anchoring the landscape with a sense of stillness.

Beyond it, an indigenous garden maze, designed by Carrie Latimer, invites exploration, its winding paths gradually drawing one inward toward the core of the home. Here, the boundary between inside and out begins to blur, giving rise to a free-flowing environment.

The ease of thoughtful design

Exposed timber beams, crafted from SA Poplar (Populus canescens), articulate the home’s architectural voice. These expressive sculptural elements introduce rhythm, depth, and texture to the interiors, speaking to a vernacular of honest construction while serving a contemporary sensibility. This is evident in the double-volume living area, where a mezzanine loft creates a sense of both volume and intimacy.

The central entertainment deck functions as the home’s social anchor. Equipped with a wood-fired pizza oven and framed by loungers overlooking the pool and garden, the space is designed for easy hosting and open-air living. Covered outdoor areas provide shelter while maintaining a constant visual and spatial connection to the landscape.

Living lightly, living well

A thoughtfully detailed and highly functional open-plan kitchen serves as a social and spatial juncture, seamlessly connecting both indoor dining and the exterior terrace. Bedrooms and bathrooms are serene, light-filled, and carefully oriented to maximise privacy while maintaining views of the surrounding greenery.

Throughout, a lightness prevails. VELUX roof windows and clerestory glazing draw in natural light, animating surfaces throughout the day. A glass-enclosed study allows for quiet focus without separating the connection to the rest of the home. At every turn, Farmhouse Constantia reflects a sensitivity to site, climate, and lifestyle. Defined by crafted detail, material wholeness, and the ease of thoughtful design — this contemporary home is rooted in nature and made for living well.

MEET THE TEAM

Architect: Kritzinger Architects | Construction: JNA Group

Projects & Roofing Divisions | Interior Decor: LIM MarcAnthony Hewson | Landscape Designer: Carrie Latimer

In a remote corner of the Karoo, perched quietly on the edge of a cliff, sits Karoo Uitkyk: a small, off-grid retreat designed for stillness, simplicity, and wide-open views.

The client wanted a place to pause. A favourite picnic spot on the farm where he’d often stop to take in the landscape became the chosen site. ‘Let’s build right here,’ he said one afternoon while standing at the edge. That was all the brief Anthrop Abbott Architects needed. What began as a simple lookout grew into a weekend hideaway for close friends and family.

Location: Karoo, South Africa

Size: 57 m2

Photographer: Leon van der Westhuizen

“To tread lightly on the land, the containers were prefabricated off-site and transported fully fitted.”

Echoes of the veld

The design is straightforward: two small sleeping cabins, each with a bathroom, and one shared space to gather — all built from converted six-metre-high cube shipping containers. Getting there requires a 4x4, but once you arrive, you’re met with complete quiet and endless horizon. 'Never underestimate 4x4 trucks. They can deliver things in places that your logic tells you is impossible,' says lead architect Leon van der Westhuizen who joined forces with Andreas Savvides to realise the project.

To tread lightly on the land, the containers were prefabricated offsite and transported fully fitted. They now rest on concrete plinths anchored into the bedrock, reducing excavation and disturbance. Timber decks fold open toward the cliff, with narrow catwalks connecting each unit along the ridgeline. The view — framed by the rhythm of the structure and the shifting Karoo light — reveals itself slowly as you move between spaces. It’s a building that’s waiting to be discovered. 'Anticipation, when used deliberately in architecture, transforms space into an experience — it's pure magic,' comments Leon.

From a distance, the cabins blend into the landscape. Exterior walls are coated in a muted olive green, chosen to mimic the colours of the surrounding veld, while vertical Thermopine battens soften the form and will silver gently with time. Inside, birch plywood linings offer warmth and texture, offset by red oxide floors, matte black steel details, and custom-built joinery. The materials were selected for their honesty, durability, and the way they age over time — becoming quieter, not louder.

Custom Kitchenette: DAM (Dokter & Misses) | Exterior Cladding: LunaWood ThermoPine | Furniture: DAM, Pedersen + Lennard, Douglas & Douglas

The retreat runs on solar power, with water systems and gas carefully integrated into the timber-clad service walls. Limited access to the site demanded that every part of the project be thoughtful, from the structural design to the delivery route. A small-footprint ethos is evident in every corner of the build.

Stone-filled gabion walls, built from local red rock, help manage rainwater runoff and gently stabilise the slope. They also echo the old kraal walls still used across the region, a quiet nod to the site’s farming heritage.

At Karoo Uitkyk, the architecture stays out of the way. It respects the harshness of the climate, the fragility of the terrain, and the power of the view. It reminds us that a small footprint in both design and intention can still leave a lasting impression.

Design is the fusion of form and function

Our Floortex range brings character to every space, combining the natural warmth of timber-inspired patterns with the durability and everyday comfort of Belgotex heterogeneous vinyl ooring.