SA'S HOME OF ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN

...herringbone oak floors in beautiful hotels.

From forest to floor

Hardwood Flooring, Cladding & Decking Manufacturers

...herringbone oak floors in beautiful hotels.

From forest to floor

Hardwood Flooring, Cladding & Decking Manufacturers

Timeless and luxurious flooring.

Smooth, versatile and hygienic.

Seamless indoor to outdoor flow.

Ideal for residential and hospitality.

Suitable for commercial and retail.

Impact and scratch-resistant.

Stain-resistant.

Slip-resistant.

Low maintenance and durable.

Eco-friendly and sustainable

100% UV stable and colour-fast.

Can be applied directly over tiles, eliminating grout lines.

Quick and neat installation by certified national applicators.

Available in 36 colours.

Available in 60 countries worldwide.

by Alex Oelofse

This month, we explore the architecture of impact — projects that shape cities, shift conversations, and stretch the possibilities of space. From commercial landmarks to reimagined spaces and urban-scale design thinking, Big Builds celebrates ambition, adaptability, and human-centred vision.

We are proud to feature the much-anticipated Amazon campus, with insights from both Paragon Architects and Design Partnership, the interior architects. A project of scale and precision, it’s a striking example of collaborative excellence.

Equally captivating is our feature on the Longkloof Precinct, with a behind-the-scenes tour in our Scape Sessions, led by Pierre Swanepoel of dhk. It’s a rare opportunity to see how an entire precinct can be reimagined through thoughtful design and a long-term architectural hand.

From there, 1 Osborne invites us to explore what it means to create an iconic commercial building in the suburbs, while Bone Design Studio takes us on a scenic tour through the quirky, Wes Anderson-inspired Trade Hotel — a delight of detail and narrative.

In our Adaptive Reuse section, we chat to the greats Jo Noero, Heather Dodd, and Thomas Chapman who are part of the vital conversation on reinvention and the responsible repurposing of space.

Our human-centric features include an energising discussion with Roland of Young Urbanists on what walkable, livable cities could and should look like. We also sit down with Elphick Proome to talk about the legacy and vision behind landmark builds that shape the identities of their cities.

We’re also proud to showcase work from two Scape Awards of Excellence jurors — MAD Architects and Snøhetta — whose big builds are shaping architectural dialogues across continents. And finally, we welcome a special contribution from Pieter Mathews, who shares his love for brutalist architecture, his standout projects, and his thoughts on the Oscar-winning film The Brutalist.

More and more, we find our pages packed with bold voices, ambitious thinking, and diverse perspectives. We’re genuinely excited about what this platform has become, and we’re inviting all of our firms to get involved — whether through the Scape Trade Emporium or the Scape Awards of Excellence.

Next month, I am excited to introduce our Editor, Sameeah, who will kick off our Education Issue on this page.

My team and I are working to build something big here. Please join us.

Rich, jewel-toned tiles in hues like burgundy, garnet, deep purples, ochre, and dusky pinks from Tile House’s collection create enveloping interiors that feel both luxurious and comforting.

Sensory design

These saturated colours evoke warmth and depth, transforming walls and floors into immersive canvases that cocoon the senses. Burgundy and garnet tiles, for instance, add a sense of opulence and intimacy, while ochre and deep pinks introduce earthy vibrancy and softness.

Incorporating gold-accented patterns elevates this richness. Gold mosaic tiles bring a sense of grandeur and timeless elegance — its reflective quality interacts with ambient light, casting a warm glow that enhances the surrounding colours and textures while creating a dynamic, luminous quality to the space.

To introduce tactile depth and visual intrigue, Tile House creates threedimensional tiles. Patterns like undulating waves or geometric forms create surfaces that shift with the light, adding movement and complexity. These 3D elements not only engage the eye but also contribute to a sense of being enveloped as the textured surfaces invite touch and exploration.

Exploring different terrains

Offering styles for every taste, Tile House sometimes turns to the past for a modern take on historically-inspired design. The Moroccan Zellige is handcrafted with irregular colours and a glossy finish, following the look of ancient Moroccan tiles. Similarly, Tile House’s Mediterranean tiles offer a playful exploration of colour with hues of terracotta, cobalt, mustard yellow, and deep sea green. Or, moving closer to the modern era, the Victorian encaustic tiles are patterned in rich, muted tones — great for hallways, fireplaces, and bathrooms.

Dynamic spaces

These richly coloured tiles invite a sense of play to interiors. High gloss tiles catch and reflect light beautifully: these can be placed near natural or accent lighting for a dynamic space. Playing with patterns, colours, and shapes bring out the unique personality of a space. Smaller tiles in rich colours can feel more intricate and delicate, while larger format tiles in bold tones make a contemporary statement. Tile House's collection of mosaicked and patterned tiles can be mixed and matched for a maximalist style or contrasted with plain tiles for a more subtle textural element.

Together, these elements — rich colours, patterns, and textures — craft spaces that are both visually stunning and emotionally resonant. They transform interiors into sanctuaries that feel intimate and embracing, offering a retreat that is as luxurious as it is comforting.

Journey to Zuberi Flooring’s Exceptional Workmanship at Their Brand-New Cape Town Showroom

Joe van Rooyen’s award-winning practice, JVR Architects and Interiors, designed an immersive experience at Zuberi Flooring’s brand-new showroom in Cape Town. As specialist manufacturers of Southern African flooring, Zuberi crafts premium engineered wooden flooring, solid hardwood flooring, decking, and cladding. Their ethos — family and sustainability — is at the heart of their home in the Mother City.

More than a gallery

JVR conceptualised the new showroom as an experience that would immerse visitors in an environment that embodies Zuberi’s ethos as a family-owned, forest-to-floor business. At the showroom, one is inspired by the sense of possibilities created by Zuberi’s products — not just the colours, patterns, and applications, but also the creativity inspired by their unique skills and expertise.

The 300 m2, easy-access showroom is housed in a striking new building in Cape Town’s design district — on the ground floor of The Rose on 117. Its five-metre-high ceilings, reminiscent of a factory or warehouse, resonate with Zuberi’s manufacturing identity. Fourth-generation owners, Michael and Lloyd Dillon, endorsed the style for its generous natural light. The layout incorporates a foyer, seating areas, deck (overlooking Table Mountain), kitchen, coffee station, and meeting room.

At home in the workshop

The showroom presents a warm, homely interior. The industrial scale of the space has been brought down to comfortable human proportions with a series of 2,7m-high screens, shelves, and dividers that maintain a sense of cohesion while simultaneously creating distinct areas.

The interior layout is carefully designed to strike a fine balance between openness and privacy for clients during consultations. Two beautiful stone workbenches are situated in a ‘laboratory’ area

where staff can demonstrate the possibilities and applications of products, by sanding, oiling, staining, and curing samples. Visitors leave with the scent of sawdust and oils along with their bespoke samples.

Circular elements dominate throughout the design, from the cylindrical storeroom to the arched doorways and art deco inflected curves of the shelves and screens. The curved edges not only soften the interiors, but also open lines of sight that cleverly provide glimpses of adjacent areas, creating curiosity and prompting an intuitive journey through the showroom.

A wide range of Zuberi’s wood products and applications — including flooring, stairs, cladding, ceilings, and decking in various designs — is incorporated into every aspect of the showroom design. Each change and variation is architecturally motivated: sometimes the design elements are playful, prompting moments of delight; sometimes they are functional. Always, the refinement and the attention to detail testify to the skill and craftsmanship of Zuberi’s products.

Zuberi celebrates local high-end products and design, a niche the brand occupies itself. The beehive-like interior of the storeroom and jars of ethically-sourced honey, placed next to Zuberi’s exclusive oils and stains, bring awareness to Zuberi’s support for a community initiative linked to Zimbabwean forest concessions, a project that protects biodiversity and provides a source of income for local communities.

The showroom’s furniture was sourced from local designers like Studio 19, Houtlander, Wiid Design, and James Mudge. Certain walls are clad with handmade, painted tiles by Veelvlak Surfaces.

Architecturally, every detail is involved in curating an immersive journey: from workshop craftmanship to local artistry. Zuberi’s Cape Town home ultimately pioneers a bold and visionary approach to design, allowing visitors to see, feel, and experience their products in an environment that inspires.

“In the ‘laboratory’ area staff can demonstrate the possibilities and applications of products. Visitors leave with the scent of sawdust along with their bespoke samples.”

The Amazon Campus Is a Beacon for the City, a Workplace Futureproofing Ecology and Culture, and an Ecosystem Nurturing Community

When Paragon Group’s architects handed over the building, it was an envelope whose contents were yet to be filled. The loose narrative, passed from Paragon to Design Partnership, was simple but tricky to execute: design an iconic building that, at the same time, is informed by its context — by the Liesbeek River home to Leptopelis frogs, the Raapenberg Sanctuary for birds, and the architectural typology of the area.

From shell to icon

Architects rarely hand over a shell. But the Amazon offices in Cape Town began with a skeleton of a building — a doublevolume masterplan to house Amazon’s homeplace amongst a lush green environment and ample light. Paragon’s framework gave Design Partnership, responsible for the interiors, flexibility for their own interpretation. Director of Paragon, Anthony Orelowitz, describes the process as ‘writing half the chapters of a book and passing it on to someone else to complete the story’. He adds, ‘Design Partnership did an incredible job with their architectural intervention. Theirs and ours have melded to create what I think is a beautiful set of buildings.’ This synergy between the architects and interior designers is felt throughout the building: in its dynamic, changing aesthetics from the façade to internal murals.

While expressing the building in a warehouse industrial, almostbrutalist manner, the structure is attuned to its context, both ecologically and architecturally. The central buildings are regulated grids, housed in a concrete shell articulating a modern look. Raw materials were selected: stripped and exposed concrete and floorto-ceiling glass maximise the light and views, and blue, oxygengenerating tiles complement the raw concrete. From the highway in the distance, one can spot the distinct tiles, designed bespoke to match Amazon’s primary colours.

‘Iconic buildings need to add value to the city,’ Anthony explains. Defined by its strong forms and recognisable Amazon blue, the precinct has become a visual marker in the city, one that he calls a ‘piece of specialness’ in the urban landscape.

The journey begins at the podium — lush, green, welcoming. As one wanders further into the vicinity, an industrial structure, crafted from handmade copper, reveals itself. It is a striking feature testifying to the range of intrigue housed within the space. As a natural, pure form of copper, its colour darkened from gold to brown, and now edges on green.

With its extensive reach around the world, Amazon has a clear vision behind the rhythm of their buildings: a rhythm that pre-empts staff needs — social and private, intimate and communal. They understand that for staff to thrive, they need to feel comfortable. But this building impresses beyond comfort. Anthony explains, ‘It’s like a journey of discovery for the people who work in the building. Every day you can find a space that matches your needs.’

Using architecture to foster relationships ensures what Anthony calls ‘futureproofing for the current and future culture’. For Design Partnership, this includes the preservation of local artistry, choosing art and craftmanship to define the campus's character.

'South African and African-born artists were commissioned for bespoke installations, while employee involvement in art selection ensured a meaningful connection to the space,' says Carina Share, one of the directors at Design Partnership. This investment in local talent not only supports economic development but also enhances the authenticity of the workplace experience.

Location: Cape Town, South Africa | Size: 115 000 m2

“It’s a journey of discovery for the people who work in the building. Every day you can find a space that matches your needs.”

“The plans echo the aspirational vision for the ideal working place.”

Fynbos and veld

With the building being so close to the river, the architects had to design around the floodplain and not dig more than three metres underground. The buildings sit on podiums and have been built to integrate with the landscape — surrounded by trees, indigenous planting right up to the edges, and earthy materials that hide the buildings' base. The ‘Lily Pads’, an organic route that wraps around the buildings, is flanked by high veld grass, making it feel as though you are walking through Fynbos and veld on the Upper Deck. Plants are layered in different heights and colours, a vision from Paragon fulfilled by the landscapers.

As for the Leptopelis frogs, special ‘highways’ protect this species: following an immense research scheme, the ‘frog highways’ were built with barriers and small openings in the fence, which prevents

them from escaping and being hurt. The once-concrete walls of the Liesbeek River were broken down, its edges softened and restored with indigenous plants and fish.

Curating the workplace

The design is rooted in the ARC — Amazon Restoration Conservation — concept, inspired by conservation principles: nurturing community, much like ecosystems ensure survival. Design Partnership, in collaboration with Interior Architects London (IA), followed this strategy: optimised for efficiency, the workplace balances social interaction and productivity, offering a variety of spaces from focus-driven zones to collaborative spaces. Alongside the casual lounges and outdoor terraces, curated amenities such as an auditorium, training facilities, and dining spaces reflect a holistic approach to the workplace experience.

MEET THE TEAM

Architect: Paragon Group | Interior Architects: Design Partnership, IA Interior

Architects | Project Lead: Cushman & Wakefield | Contractor: GVK Siya Zama

Furniture Provider: Steelcase, Nowy Styl, Ahrend | Project Manager: Procrit Engineer: Sutherland & DSE | Engineer Security: QCIC Security Group | Acoustic Engineer: SRL | Cost Manager: RLB | Lighting Design Consultant: Pamboukian Light Design | Green Consultant: Solid Gree Consulting | Art Consultant: Momo Gallery Telecoms Design: Hargis | AV Design: EOS IT Solutions, Omega Digital Landscaping: Contours Landscapes

Inspired by Cape Town’s natural ecosystems, the design layers biophilic elements — greenery, greenhouses, and terrariums — enhancing environmental performance and employee wellbeing. The campus supports biodiversity, housing 20 critically endangered plant species.

The ‘treehouse’, a central architectural feature in the reception, anchors the campus as a central hub for collaboration, training, and curated dining. More than just an office, the Cape Town campus embodies IA and Design Partnership’s approach to future-focused, humancentric design where innovation, sustainability, and culture come together to create a thriving workplace.

Beyond its physical design, the campus fosters a strong sense of community and inclusivity. It's more than just a workplace, providing spaces for knowledge sharing, cultural engagement, and social interaction. Spaces are distinguished from each other, each meeting the different needs of employees. These defined spaces — and the people that will inhabit them — informed key aspects of the workspace, from art selection to environmental features, fostering a sense of ownership and belonging.

It's an office unlike any other. The Amazon campus in Cape Town emerges as an ecological landmark. Designed to support the company's shift to a full-time office presence, the campus reimagines the traditional workplace by integrating conservation, wellness, and adaptability.

Furniture: Pedersen + Lennard, Ergoform, Arkivio, Entrawood, Haldane Martin, Tabletops, Krost Office Products | Stone Top: Sangengalo Flooring: PentaFloor, Traviata, Polysales | Tiling: RVV Tile Gallery, Kalki Ceramics, Wolkberg Casting Studios, Lime Green Sourcing Solutions | Ironmongery: Assa Abloy | Paint: Dulux, Paintsmiths | Pebble Seats and Tables: Igneous Concrete | Planters: Igneous Concrete, Indigenus | Speedgates: Frost International | Bamboo Decking: MOSO Africa, Master Decks | Blinds: Alplas | Waterproofing: Aspect | Fabrics: Hertex, Sunbrella, Home Fabrics, The Mill, Warwick | Wood Finish: Osmo | Joinery: RMS Shopfitting | Lighting: MOS Products, Regent Lighting Solutions | Ceiling: OWA

Orelowitz Founder and Director, Paragon Group

@paragongroupza www.paragon.co.za

Carina Share, Director @designpartnership www.dp-group.com

Vivid Architects’ Sophisticated Commercial Establishment in Claremont

Situated amongst apartments and boutiques, this high-end commercial development joins the renowned Citadel offices as a stylish workplace in the heart of Claremont. At a bustling intersection, 1 Osborne commands attention with its rhythmic slats and warm tones. The seven-floor property is a testament to efficient layout: its core is encircled by office spaces and flanked by service areas discreetly positioned to the southeast.

The Cavendish Street entrance of 1 Osborne features handmade tiles, natural timber, and lush landscaping that softens the transition between commercial and residential zones. Durable off-shutter concrete, painted brickwork, and timber look aluminium screens were selected to balance longevity with low maintenance.

Size: 6500 m²

Location: Claremont, Cape Town

Strategic function, aesthetic pride

Entry points are thoughtfully planned, with staff accessing the building directly from the subterranean parking — an engineering feat that maximises land use while maintaining an unobtrusive presence. Visitors, on the other hand, are welcomed at street level via a sophisticated reception area. The ground floor is a dynamic urban space, hosting a vibrant restaurant deck with an in-house roastery, restaurant, boutique coffee house, and a coworking ‘slow lounge’ — meeting the evolving needs of modern professionals. From various points inside, sweeping views stretch from Constantiaberg to the iconic Table Mountain.

The aesthetic harmony of the façade serves a dual purpose: integrating contemporary design with the urban environment and minimising solar gain through a combination of punctured brickwork and aluminium fins that emulate the warmth of timber.

The use of balconies adds depth while providing natural shading and filtered light throughout the day. Extensive greenery — including creeping plants — envelops the structure, integrating nature into the corporate environment while promoting sustainability. This is supported by solar panels, a borehole irrigation system sustaining extensive planting, and the building’s energy-efficient HVAC and lift systems. To further encourage green commuting, bike storage and electric vehicle charging stations are readily available.

The site originally housed an ageing apartment block, overdue for transformation. Following nearly three years of negotiations, the re-zoning process commenced, backed by local councillors who envisioned the project as a catalyst for revitalising the area near the Cavendish Square Shopping Centre. Just as the project was set to break ground, the Covid-19 pandemic struck, prompting the developers to reassess and adapt their plans.

Architects: Vivid Architects, Bruce Burmeister Architects | Quantity Surveyors: Hope Warren Schultz Quantity Surveyors | Structural Engineer: DeVS-SiVEST | Wet, Mechanical, and Electrical Engineering: Triocon | Façade Engineers: PDK Civil & Construction Contractor: Isipani Construction | Landscape Architect: AT Landscape Architects

“The re-zoning of the site, driven by strategic foresight, has shaped a new architectural identity for Claremont.”

This resulted in a design that could seamlessly transition from commercial to residential use if needed. Magma Property Group, the developers, collaborated closely with renowned hospitality brand Singita, who are also the shareholders, to shape a bespoke design that aligns with their commitment to environmental consciousness and elegance. The architectural vision for 1 Osborne matched these expectations: a cutting-edge building that resonates with the surroundings and the needs of modern, corporate tenants.

Suburban revitalisation

Vibrant neighbourhoods like Claremont and Newlands have attracted financial services companies as business hubs for many years. The re-zoning of the site, driven by strategic foresight, has not only attracted corporate tenants but also shaped a new architectural identity for Claremont.

1 Osborne reimagines what a modern corporate building can be: sustainable and sophisticated, an urban landmark whose aesthetic adds value to Claremont’s architectural landscape.

Tiles: Tile House | Vinyl Flooring: KBAC Flooring | External Paving: Revelstone | Mats: COBA Flooring | Timber Ceilings and Portal: Oggie Hardwood Flooring | Sanitaryware: Geberit, Duravit, Hansgrohe | Ironmongery: dormakaba | Feature Face Screen: Façade Solutions | Shopfronts and Glass Balustrades: Mazor Group | Painted Facebrick: Corobrik | Plastered Façade: Marmoran | Steel Balustrade: Sparcraft | Paint: Plascon | Waterproofing: Mapei | Signage: Ultrasigns

“The seven-floor property is a testament to efficient layout.”

@vividarchitects

www.vividarchitects.co.za

Bruce Burmeister, Architect and Founder

Bruce Burmeister & Associate Architects

When it comes to timeless style and enduring beauty, few materials rival the elegance of natural stone. The Tuscania Limestone tile from Stiles captures that essence — reimagined through the innovation of Italian porcelain craftsmanship.

Pierre du Plessis, the Stiles showroom manager at Paarden Eiland, Cape Town, gave us the inside scoop on what makes this tile a standout for homeowners, architects, and interior designers. ‘It’s a very popular tile with a timeless aesthetic that will be relevant for many years to come,’ says Pierre.

Mediterranean charm

Crafted in Italy, the Tuscania Limestone is a large-format porcelain tile with a soft matte finish. It reflects the strength, beauty, and versatility of authentic Tuscan limestone — a material renowned for its subtle pastel tones and Mediterranean charm.

‘These tiles work well with modern and contemporary interior design styles as well as coastal, Scandinavian, and Japandi aesthetics,’ Pierre explains. ‘They have a classic stone look with soft movement, delicate veining, and subtle colour variation.’

Ice, Beige, Ash, and Coal

The lighter tones, Ice, Beige, and Ash, are ideal for creating neutral, warm, and minimal interiors, much like the tone-on-tone palette made famous by Kim Kardashian's Hidden Hills mansion. Equally, interior designer Shea McGee famously said, ‘I use limestone in many of our projects for its ability to be a neutral foundation for a room that is both refined and rustic. ’The fourth colour of the

collection, Coal, is a bolder and more dramatic shade that works beautifully in moody, textured spaces.

Exceptional versatility

Available in a matte rectified finish for indoor use, a slip-resistant finish for outdoor areas, and as a paver for patios, stairs, and pool surrounds, the Tuscania Limestone tile creates a cohesive aesthetic throughout an entire property. The soft warmth of the limestone works well with woods ranging from walnut to pale oak and with natural materials like seagrass or linen.

The result? A harmonious design language and flow throughout the home. ‘If you look through the property all the way to the pool,’ Pierre says, ‘the eye sees one uniform surface, a seamless transition from interior to exterior.’

Durable, elegant, and effortlessly chic, Tuscania Limestone is more than just a tile, it's the foundation for beautiful, balanced living spaces.

Visit your nearest Stiles showroom to experience the collection in person or find them online at www.stiles.co.za

5 Modern Finishes

Attivo comes in 5 modern finishes complete with matching bathroom accessories to create the perfect cohesive space

Elphick Proome’s Landmark Architecture Revives African Cityscapes

Having designed landmarks across the African continent, from South Africa to Ghana, Angola, and beyond, Elphick Proome designs identity-rich buildings that integrate sustainability at their core.

“We don’t want to reinvent the wheel; we want to evolve the wheel into the next project.”

www.eparch.co.za

Your buildings have a distinct aesthetic, and others are quite monumental. What is your approach to creating ‘building identity’?

Our endeavour is to have functional façades from which we derive the form and skin of the building — in other words, it’s identity. The Unilever project we did almost a decade ago was a very large dry fluids plant. The exterior skin of the complex derived from the components of the factory. We wanted to outwardly demonstrate the nature and functionality of the building: the entire mechanism of their operation was driven by conveyor belts, so we used that as a metaphor in generating the peripheral elements and the sectional form of the building. In the end, it had a sense of movement, which was outwardly legible.

Many of your projects work well not only metaphorically, but functionally too — especially in their resilience to harsh climates in certain parts of Africa. How do you design for this?

Our work is contextually responsive: one of the tenets of our design approach. We integrate sustainability all the way from façade to architectonics — having flexibility within the arrangement: thinking about floor plates, natural lighting, and ventilation.

Façades are where the real technology comes through to regulate temperatures. Reducing heat gain and controlling the ingress of direct sun are important for these hot climates. The filter façade is not a new concept; it’s been used all around the world. We just completed a building in Nairobi where we induced ventilation through a façade and a very simple fenestration mechanism. We drew on the natural ‘chimney’ system of ventilation for the building, which the Arabs were doing 5 000 years ago. We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel, but we want to evolve the wheel into the next project.

Buildings with such a strong presence may, of course, alter the cityscape. How do you see your large-scale builds fitting in with the city-making process?

We're working on a building in Ghana at the moment which forms part of this new bulk growth that exists as a satellite to the main city. It's still part of the string of the CBD, so you have the opportunity to develop connectivity and engage with existing environments. Keep in mind, it's a 50-year process to build a city! There's a building we've just completed in Tatu City, in Kenya, as well, where we were essentially the first kids on the block. It was the first office building in an entirely new city. We had to imagine how to react to things that don’t exist yet and hope that future architects who develop buildings adjacent to ours would react positively.

In South Africa, you’re known for the Cruise Terminal, the portal to the ‘Kingdom of the Zulus’. How does that coincide with the growth of Durban?

The Terminal forms part of the Durban Point precinct — which was quite a dead urban environment. The Point dates back to the 1850s, so those buildings have fallen into terrible disrepair because of the connectivity issues and security. But the Terminal is on the other side of the harbour, and it didn’t activate the Point precinct.

Our methodology, then, was to create an expansive urban space that would help connect the promenade all the way back around and activate the Point: it's a very sustainable way of looking at cities — through generating traffic and movement with urban integration. It's a fantastic example of revitalisation where you rejuvenate a previously dead and unused part of the city and connect it to surrounding areas. By the time we finished the project, that entire street had upgraded. There were tenants and operational businesses — incredible to see.

“Our endeavour is to have functional façades in a building, which then derive form and skin to give identity.”

Rethinking sustainable design sometimes requires looking to the past and not the future. Norwegian-based, multi-disciplinary practice Snøhetta designed Vertikal Nydalen, situated in a former industrial area, to have a self-sufficient climate system based on principles of thermal mass — a tool used in architecture of the past. Intended as a ‘new town square’, the mixed-use, 18-storey building has street-level restaurants, offices, and apartments while offering public recreational spaces in the surrounding area that is being redeveloped into a car-free zone.

With PV panels, geothermal wells, efficient heat pumps, and a low energy heating/cooling system based on thermal mass, the building presents a low-carbon alternative to traditional heating and cooling systems. In addition, the angular walls enhance the organic flow of air for natural ventilation. With the spectacular view of the city and the river running past the building, the interior architects drew inspiration from light hitting the babbling water at different times of day to guide the interior colour scheme. In keeping with the building’s environmentally-conscious architecture, the wooden exterior lends itself to the warm, nature-centred aesthetic, which will turn from brown to grey over time. Both the interior and exterior of the building are made to withstand the test of time, creating a space that’s designed for the future.

Anne Cecilie Haug, Senior Architect @snohetta www.snohetta.com

dhk Architects’ Multidisciplinary Design of the Longkloof Precinct — Cape Town’s New Urban Square

Stitching together historical and contemporary contexts, dhk Architects, a leading multidisciplinary architectural studio, revived a neglected precinct in Cape Town. Featuring several precious historical buildings, the area required sensitive urban and architectural design: respecting heritage while enhancing the aesthetic and functional value of the surrounds.

The Longkloof development comprises the restoration of several historic buildings and the construction of a 154-key, five-star hotel for a leading global hospitality brand. The scheme introduces a new public square in the mixed-use Longkloof Precinct off Kloof Street in Gardens, Cape Town. Owned by Growthpoint Properties, the area is now a publicly accessible urban square featuring planting, trees, integrated wooden seating, and generous stairways.

Location: Cape Town, South Africa

Size: 16 500m2

Photographer: Sean Gibson

"The overarching vision was to create an interconnected, landscaped public realm with new street frontage as well as a secure, yet publicly accessible, external space at the heart of the precinct."

Authentic character

Comprising six separate erven, the site features historic buildings that were originally developed in the early 1900s. Over the years, the precinct became fragmented, lacking spatial cohesion and connectivity, with much of the site given over to surface car parking.

dhk’s involvement started in 2009 when they were briefed to design an office on the larger Park Street site at MLT House with surface parking behind. The design later integrated several other buildings in the precinct, including the Spar and Kloof annex building and parking (incorporated in 2011), 32 on Kloof (2013), Darter and Threshers, known as Longkloof Studios (2014), The Refinery, the former West Cliff school (2017), and No.2 Park Street, formerly Rick’s American Café (2024).

It also became clear that there was a need, and an opportunity, to fully integrate all the erven into one cohesive precinct. In 2015, dhk prepared an urban design proposal to create a vibrant publicly accessible environment to connect the surrounding context in a meaningful way while respecting heritage indicators and the existing streetscape.

'The Longkloof Precinct project was a complex design challenge that brought together all of our multidisciplinary design skills to create an honest dialogue between heritage and contemporary elements in a sensitive and respectful combination,' says Pierre Swanepoel, partner at dhk Architects.

Sensitive adaptive reuse

dhk’s design used adaptive reuse principles to revitalise the heritage buildings, introduce contemporary additions onto existing buildings, and add new-build components to fully activate the site. Ground floor retail, restaurants, and cafés enliven street edges, while a new hotel overlooking the public square contributes to the economic profile of the site. Basement parking helps to activate the public realm with greater pedestrian permeability.

The urban design response strategically locates permissible bulk (floor space) and introduces a more accessible urban language, while fragmenting building forms reduce bulk and maintain reference to historical buildings. New links through the precinct connect different parts of the city and the existing streetscape. This creates a vibrant, publicly accessible environment that enhances the active qualities of Park and Kloof Streets and emphasises pedestrian permeability. Street edges are defined with canopies and colonnades, and vehicular access is restricted to ensure a pedestrian-friendly environment.

Sustainability was prioritised through the adaptive reuse of existing buildings, preserving embodied energy. High-performance glazing reduces solar gain, while energy-saving lighting and high-efficiency systems in the refurbished buildings enhance performance. Water conservation is achieved through indigenous landscaping and efficient fixtures, while the urban design language improves pedestrian links and reduces vehicle impact.

This flagship project showcases how contemporary architecture and sensitive urban design can enrich historical areas while stimulating economic activity and creating vibrant public spaces. Derick Henstra, the executive chairman and co-founder of dhk Architects, says: ‘Longkloof is an outstanding demonstration of how precinctled urban design and sensitive, considered architectural design can be combined to add value to neglected urban environments. We are absolutely delighted with the results.’

Tiling: RVV Tile Gallery | Glazed Aluminium: Mazor Group

Ceilings and Partitions: Scheltema | Timber Decking: Decks 4 Life | Vanities: WOMAG

@dhkarchitects www.dhk.co.za

Architect, Urban Designer, and Landscape

Architect: dhk Architects | Main Contractor: Isipani

Construction | Quantity Surveyors: MLC Quantity

Surveyors & Construction Consultants | Interior

Designer: K/M2K Architecture Interior Design | Civil

Engineers: LH Consulting Engineers | Electrical, Mechanical, Fire, Structural, and Wet Services

Engineer: WSP | Project Manager: Atvantage

Electronic Services Consultant: Ethnic Technologies

Green Building Consultant: Ecolution Consulting

Audiovisual and Acoustic Design Consultant: Mtshali-Moss Projects Africa & Professional Services

Health and Safety: Safetycon | Enabling Works

Contractor: Franki

Heat a room to 30 C

Cool a room to 14 C

Heat water to 70 C

Chill water to 10 C

All from one system simultaneously!

The world’s first two-pipe heat recovery system that Simultaneously Cools and Heats

CITY MULTI R2 series offers the ultimate freedom and flexibility, cool one zone whilst heating another.

The BC controller is the technological heart of the CITY MULTI R2 series. It houses a liquid and gas separator, allowing the outdoor unit to deliver a mixture of hot gas for heating, and liquid for cooling, all through the same pipe. The innovation results in virtually no energy being wasted. Depending on capacity, up to 50 indoor units can be connected with up to 150% connected capacity.

Reusable energy at its best

A Holiday in Wes Anderson’s World? Bone Studio Fulfils the Vision

Film director Wes Anderson once controversially declared that he does not have an aesthetic. He differentiates this from his distinct way of filming — one that is reinvented with each project. The Trade Boutique Hotel is no different: refashioning its own identity as a heritage building, the hotel settles into its central place in the city.

The Trade Boutique Hotel and its restaurant, The Wes, display a mix of Wes Anderson whimsy and Parisian romance, infused with their own, quirky character — a sense of humour and joie de vivre. This eightstorey heritage building in Shortmarket Street, owned and developed by Rawson Developers, is now an aparthotel providing the best of both worlds: room service on a whim and the ability to cook for yourself, whether you’re staying in the short or long term.

Location: Cape Town, South Africa

Size: 3300 m²

“…a mix of Wes Anderson whimsy and Parisian romance, infused with their own, quirky character – a sense of humour and joie de vivre”.

The external façade severely lacked soul with its plaster band details and face brick in one solid colour. As the designers chose gradients of corals, peaches, and burgundy to personalise each passage on the inside, they applied new colour to the outside too — in a bold, ombre vision. ‘It scared us a little, but we trusted the process and it became an iconic colour on Loop Street. It shows what an impact some fun can have,’ says Nicola, designer and coowner of Bone Studio.

The lobby’s red marble tiles and the entrance foyer’s stone were preserved to retain the building’s heritage. But despite its charm, as an existing building, it was filled with surprises requiring onsite problem-solving: walls were concrete instead of brick, beams seemed to have no symmetry, and the hidden services demanded on-site re-coordination. ‘We had to commit and trust the process,’

Nicola says. ‘There was a lot of blood, sweat, and tears along the way, but in equal measure celebration and a sense of pride. We adopted a no-fear attitude throughout the process.’

There is a strict complementary system where a duller colour is paired with a brighter one, such as navy with coral... and mint with grass green. The colour range is distinguished in three themes: Ruby, Fred, and Ginger. At the restaurant, powder blues, pinks, and yellows — inspired by Wes Anderson films — form a base. They are brought to life by shrieking brights – the fuchsia pink wallpaper, carefully placed art, and mirrors that are layered with loudness. Luxury is perceptible in textural details: green velvets, Bone Studio’s custom, tiled bedside tables, and modern, Italian tiles.

MEET THE TEAM

Architects: Bruce Wilson Architects

Interior Architects/Designers: Bone Interior Design Studio

Flooring: FloorKing | Custom carpeting: Gorgeous Floors

Joinery: Leisure Kitchens | Electrical: TJR Electrical and Building | Lighting: Décor Lighting, ARC Lighting, Luna Lighting | Tiling: Tilespace | Sofas: Wunders | Headboards: ASCOT Upholstery | Beds: Contour Beds | Mechanical ventilation: Coldfact Projects | Décor: Poetry Homeware Steel TV units: Ironstone | Custom mirrors: Architectural Glass Design | Dried floral arrangements: Spinlea Farm Window treatments: The Best Blind Company | Plumbing: Summit Plumbing

@bonedesignstudio www.bonestudio.co.za

Despite the overflow of colour, decoration, and patterns, the essential materiality is functional and easy to maintain. Timber look vinyl flooring laid in a basketweave pattern, quart stone countertops, and melamine kitchen joinery were intentionally chosen for these reasons.

It’s a cinematic experience that comforts with its romantic, playful charm. Although the journey to realise this vision was challenging, the architects are content with the result: ‘When the outcome is received so well, by the public and the industry, it adds to the love.’

• Premium acoustic material

• Panel size: 2400 x 600mm

• Create a feature wall in any room

• Natural nish with black felt backing

• Sound absorbing

• Helps reduce echo

• For indoor use only

• Easy to install

Great spaces are great for business. There’s nothing quite like a fresh new look to spruce up your business and attract new faces. ‘These days, commercial spaces are expected to be energy efficient and eco-friendly while promoting productivity, collaboration, and well-being,’ says Marc Minne, CEO and co-founder of leading composite building materials manufacturer, Eva-Last.

The value of an appealing, well-designed space cannot be overstated: telling your brand story, attracting clientele, and raising employee morale.

Meeting employee and environmental needs

A few simple updates in line with the modern lifestyle are great ways to attract new tenants or customers and ensure a healthy, happy environment. From creating street appeal to adding ecofriendly finishes, businesses that prioritise mindful design upgrades reap long-term benefits that are equally functional and aesthetic, boosting job satisfaction and lowering operational expenses.

Workspaces that inspire

Environmental awareness, e-commerce, and hybrid work models have changed the way we go about our business, making it critical that your commercial space is up-to-date, comfortable, and inviting.

Today’s tenants and patrons seek more from a commercial space than just a place to work or shop — they want their environments to reflect adaptability, creativity, and harmony. A business that can

support flexible working arrangements, promote sustainability, and provide a sense of belonging stands out among the rest.

Premium materials

From large-scale developments to small office revamps, the right materials ensure longevity and align with the modern values of the business world. Eva-Last’s extensive range of composite decking, cladding, architectural beams, railing, fencing, and indoor flooring have transformed malls, office spaces, and buildings into beautiful, inspiring places of trade.

Offering sustainable materials that are not only aesthetically appealing, but also robust and well-manufactured, Eva-Last supercharges commercial environments.

The business case for a better space

Commercial spaces — from corporate offices to entertainment venues and retail outlets — provide unique opportunities to foster collaboration, elevate customer experiences, and drive overall business success.

With Eva-Last’s extensive product range and commitment to innovation, you’re not only upgrading your space — you’re building a better future for your business, your people, and the planet.

Offices, Malls, and Substations are Given a Second Life

“The building’s modernist form — a staircase-like tower — was kept largely intact, impressing with its pre-cast concrete panels and strip windows.”

Founder

@noeroarchitects

www.noeroarchitects.com

Words by Sameeah Ahmed-Arai

A scarlet eye blinks in the distance, a sharp flash against the black sky. Through morning and night, its pulse persists. Crowning one of Cape Town’s highest spires, the crimson light is a beacon amongst the dense high-rise buildings in Cape Town’s CBD. In 1993, when the building’s antenna was originally built, a helicopter was flown in to complete the work. Now, on the 28th floor of Hotel Sky, the tower’s spark is associated with the Sky-Hi Ride, a circular-seated drop overlooking the city at 146 m above ground and plunging at a speed of up to 100 km/hour.

For over three decades, the building was an office block known as the Metlife Centre. Noero Architects inherited architect Douglas Roberts’ work rather optimistically: its central location and proximity to tourist attractions and business hubs, like the International Convention Centre, placed it perfectly for the hospitality industry. Converting office spaces into a 550-bed hotel took immense courage: with an 8,4 m structural grid, three rooms are sardined at 2,2 m each and the prestressed concrete floor demanded intense accuracy — lacing all services (like pipes) between the prestressed wires without cutting them.

Architect and founder Jo Noero is sincere in his philosophy that ‘each and every building can be improved over time.’ Improvements, here, were largely on the ground floor lobby and rooftop, which includes two swimming pools that appear to ‘hang off’ the timber decks. The building’s modernist form — a staircaselike tower — was kept largely intact, impressing with its pre-cast concrete panels and strip windows. Only additional openings were added, small and indecipherable, to improve ventilation.

While your eye may once have been led up the staircase, its postNoero transformation leads you in the other direction — down. You catch the red flash first, noticing its slender, 40-metre tower guiding you to the HOTEL SKY sign (lit in jarring red) alongside the topmost edge of the build. The futuristic light stretches to the corner, where you follow steps dropping at the building’s side — down, down, down to the lobby and right into the city itself.

“On the 28th floor of Hotel Sky, the tower’s spark is associated with the Sky-Hi Ride, a circularseated drop overlooking the city at 146 m above ground and plunging at a speed of up to 100 km/hour.”

The postmortem of an unused 1980’s shopping centre on the outskirts of Johannesburg revealed its domestic-like scale and close proximity to the Boksburg CBD, a neighbouring church, and civic buildings. Deemed to have strong conversion potential, the building’s new existence was designed by Savage + Dodd Architects, a firm with decades of experience in transforming offices and factories into housing.

‘There’s a misconception that affordable housing isn’t designed,’ says Dr Heather Dodd, co-founder of Savage + Dodd Architects and doctoral graduate from the University of the Free State. ‘But good design and bad design can cost the same amount. It’s about understanding how design really matters.’ Affordable but well-

designed spaces provide the essentials while allowing flexibility for residents to personalise their home over time — perhaps upgrading to a glass shower door or changing the kitchen cupboards.

Slava Village, accommodating 50 units consisting of studio, oneand two-bedroom apartments, contributes towards reviving the mining town in decline. Every setback brought a countering opportunity. Deep space? A chance for New York–style loft bedrooms and walkways that open into courtyards. Tight budget? Bright colours are a cost-effective way to brighten the space and distinguish areas. Describing the adaptive reuse design process, Heather Dodd says, ‘It’s like a jigsaw puzzle trying to figure out how it all fits together.’

Heather Dodd, Founder

For centuries, theorists and practitioners alike have questioned the architect’s place in building society. For Thomas Chapman, founder of Local Studio, his adaptive reuse projects have shown just how proactive architects might be, shifting the traditional clientarchitect relationship in the process.

Local Studio’s interventions almost always originate from a wellversed understanding of history — an inquiry into a building’s stories. Such is the case with this community centre and library in Soweto, Johannesburg. Lantern House was first imagined through a theoretical framework: Sub-city, an urban acupuncture intervention targeting South Africa’s thousands of defunct substations from the apartheid era. Why this typology? ‘They’re obsolete the minute they’re built,’ Thomas explains. ‘Technology modernises much quicker than buildings take to build.’

Sub-city began as a speculative project, commissioned by Interactive Africa, the founders of the Design Indaba conference, who had secured seed funding from corporate giant Sanlam for a series of urban acupuncture projects across South Africa. This complex chain became even more complicated as the project was set to become a reality. Taking on what would usually be a developer's role, Local Studio’s architects identified a burntout substation in Eldorado Park, near an existing social housing development in Soweto, which would serve as the first Sub-city prototype. What followed were months of administrative setbacks, navigating land rights and ownership. Restructuring the architect’s role began with a different kind of project pitch to appeal to investors. ‘Even something like a community centre needs a business plan,’ Thomas adds.

At only 34 m2, the substation’s tight frame was unfit for the size of the community. Local Studio chose mass timber to extend the original brick structure. Inside, the timber’s warm, electric glow spans three storeys housing a maker’s space and an amphitheatre, a library, a digital learning wing overlooking the park, and a counselling room. Its roof leaves no space wasted, featuring a terrace where one can watch over Soweto. With the body corporate effectively owning the library, Lantern House strengthens its ties with the social housing community, offering a hub for recreation and company.

Thomas Chapman, Founder

@local_studio www.localstudio.co.za

Location: Paris, France

Located in the newly developed Clichy-Batignolles neighbourhood in Paris, UNIC by MAD Architects sits beside Martin Luther King Park and the new courthouse by Renzo Piano. The project, designed in collaboration with local firm Accueil – Biecher Architectes, was the result of an international competition.

‘We worked closely with local government, city planners, and architects to ensure UNIC is a creative and iconic residential project integrated with the community,’ says MAD founder, Ma Yansong.

Facing the park’s 10-hectare green space, UNIC’s organic form is shaped by gently tapering, sinuous floor plates that create dynamic interiors. Its stepped terraces blur the boundary between architecture and nature, drawing greenery upward and offering residents a connection to the outdoors. Representing stacked courtyards, the design collapses the distance between human and landscape.

Rising 13 storeys, the upper levels provide sweeping views of Paris, including the Eiffel Tower. Its double-core structure and bare concrete façade reflect an elegant simplicity. The podium connects to an adjacent public housing complex and provides direct access to metro infrastructure, a kindergarten, retail spaces, and restaurants — enhancing social cohesion across a diverse community.

UNIC aims to foster an organic, inclusive neighbourhood in the heart of a transforming urban landscape.

Andrea D’Antrassi, Associate Partner @madarchitects www.i-mad.com

The Samsung Slim Duct air conditioner is designed to fit seamlessly into a variety of spaces, offering flexible installation options with its 2-way air inlet. Whether installed from the bottom or rear, it ensures optimal airflow

throughout the room. Its discreet design can be concealed within ceilings or elegantly showcased in exposed settings, blending perfectly with the room’s aesthetic while delivering powerful, efficient cooling and heating.

Fourways Group are the national distributors of Samsung aircons and HVAC experts to help meet all your air care needs. Contact Fourways for assistance with VRF designs.

In premium commercial design, climate control should enhance, not interrupt, the aesthetic of a space. For a recent office development in Middelburg, Fourways Group set a new benchmark in climate control by choosing the Samsung Duct S system: a smart, compact solution that delivers powerful performance while blending effortlessly into a sleek, exposed-ceiling layout. Powered by the DVM S2 VRF system and paired with 13 Hide-Away Ducted units, this installation achieves quiet efficiency, minimal visual impact, and consistent comfort across the space. Ranging from 3.6kW to 11.2kW, these units offer tailored comfort to each office, ensuring zoned climate control without sacrificing style. Installed by Speedking Cooling Services and Makulu Installation and supplied by Fourways Group, this project highlights how the collaboration of expertise results in cutting-edge HVAC solutions that enhance commercial builds.

At the heart of this installation is the Samsung DVM S2 outdoor unit. This revolutionary system brings energy efficiency, reliability, and flexibility. Designed to work seamlessly in extreme conditions, the DVM S2 uses less refrigerant, significantly reducing environmental impact while offering exceptional cost savings. Smart Pressure Control ensures consistent, optimal temperatures across all zones, while AI-driven optimisation continuously adapts to maintain a balanced, comfortable environment.

Each Duct S unit is paired with Samsung’s Wired Remote Controller (Touch Simple Type MWR-SH11N), featuring a touchscreen interface, IR receiver, quiet mode, On/Off timer function, and individual unit control for each office, making it easy to manage comfort across the workspace. For centralised control, the MCMA300BN Touch Controller provides real-time energy monitoring, remote adjustments, and smart scheduling, allowing facility managers to control the system's performance.

Sustainability meets long-term performance

One of the standout reasons for choosing the DVM S2 system was its advanced heat recovery capability. In modern office environments, some spaces require simultaneous cooling and heating. The DVM S2 has an advanced heat recovery capability, which distributes excess heat from cooled zones to areas needing warmth, drastically reducing energy consumption while maintaining optimal temperatures. Combined with smart pressure control and a low-GWP refrigerant, the system delivers a future-ready, ecoconscious installation without compromising performance, offering a smarter, more efficient climate solution for open-plan offices and dynamic commercial environments.

The Space Between Builds: The Young Urbanists Push for Better Cities Fostering Community

If you’ve been in Cape Town during peak season, you may have noticed the peculiar closures of one of the city’s busiest streets. As part of a social experiment, Bree Street was turned into a pedestrian-only area every Sunday to showcase how we can adapt our city to work for people — not cars, not infrastructure — but the communities and people that the city is meant to serve.

This experiment was hosted by the Young Urbanists South Africa — an organisation dedicated to bettering our cities for the people and the environment. ‘The Young Urbanists is made up of a diverse group of people, coming together to dream about our city,’ says Roland Postma, the managing director of Young Urbanists South Africa. Each week, the street transformed into a hub for communities to come together for activities such as picnics, silent reading, and mending clothes. By creating these car-free zones, the Young Urbanists hopes to promote safety for people, reduce reliance on cars, and open up spaces for recreation.

Urban utopia

This utopic vision for Cape Town brought about new ways of thinking through cities and reimagining how spaces can be utilised for community engagement and leisure. ‘We need people-first neighbourhoods,’ says Roland. He goes on further to note that we need affordable housing that is liveable, well-situated with access to amenities, and, alongside that, reliable public transport to connect our city.

As part of an ongoing movement to create better cities, SPACE10 published research on what constitutes an ‘ideal city’. After studying 53 cities in 30 countries, the researchers defined an ideal city as one that is safe, resourceful, accessible, inclusive, climate resilient, and most importantly, desirable — a place where people enjoy living. Establishing multiple hubs of activity within a city leads to a dense and decentralised urban layout that reduces everyday travel around the city. Part of this concept of better urban planning is creating what is known as a 15-minute city. This is where everything a person needs to survive — shops, schools, recreational spaces, work — is within a 15-minute walking distance.

The spaces between

The Bree Street experiment was about more than just challenging our reliance on cars; it was a way of pushing for more urban spaces that enrich our city’s landscape and offer greater connection for building a sense of community.

‘We can’t build something without the right land-use integration, and that’s where urban design comes in,’ Roland explains. ‘What’s missing is looking beyond buildings and focusing between buildings — coffee at, say, Paulines, taking the kids out to Greenpoint park, or walks along the promenade — these points of connection are very important for making cities liveable and desirable.’ He explains that we need more of spaces like these, especially outside of the city bowl.

Strategies for improving cities are centred around balancing the built environment with the urban landscape. A large part of the work that the Young Urbanists engages in questions the layout of our city and pushes government, civilians, and architects, to think through our city and (re)imagine our cities as liveable, equitable, and nature- and people-friendly.

Centre-periphery integration

‘We need to densify in a sustainable manner,’ Roland explains. In the context of Cape Town, this means addressing the legacies of the past, which haunt the city’s landscape. With the housing market pushing people further and further out onto the periphery, while work and education remain centralised in the city centre, Cape Town’s spatial planning echoes the discriminatory sentiments of the past. These segregationist policies during colonialism and

apartheid divided the city to limit access and movement; its spatial results continue to cut people off from the centre of activity.

People living on the outskirts are forced to be dependent on movement to and from the city centre. Increasing mobility with advanced public transport systems is part of the organisation’s mission of supporting accessibility and promoting sustainable development. Recently, the Young Urbanists integrated the railway (PRASA) timetable with Google Maps. In rethinking and reimaging our city, transformation needs to occur from all fronts, where we challenge inherited legacies of apartheid spatial planning and focus on building the contemporary African city.

And, as our cities grow, design needs to consider people, embrace nature, foster connection, and inspire communities. Our city is made up of so much more than infrastructure — it’s community that forms the heart and pulse of the city.

Roland Postma, Director

@young_urbanists www.youngurbanists.substack.com

LOW MAINTENANCE | WEATHER RESISTANT WATER REPELLANT | HIGHLY DURABLE | UV STABLE

LOCALLY MANUFACTURED | LONGEVITY IN DESIGN

specialist suppliers of large scale, low maintenance pots + planters | bench + wall paneling | seating + furniture | bollards, bins and various public space installations | custom design + landscaping essentials

+27 (0)82 443 0084 | info@igneous.co.za | www.igneous.co.za

innovators in all weather, lightweight polyconcrete

Architect Pieter J. Mathews reviews Brady Corbet’s film

The Brutalist: the story of architect László Toth who fled war-torn Europe and built his legacy in America.

Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist contains both fiction and documentary. European émigré architects, particularly those connected to the Bauhaus, had a profound impact on the post-war built environment. Figures like Hungarian-born László Moholy-Nagy and Marcel Breuer, despite their fame, struggled in the early stages of their careers.

Words by Pieter J. Mathews

Photographer: Serinus

I am convinced that secondary character precedent studies, like the German Bauhaus architects who fled the Nazis — Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe — coupled with earlier Jewish émigré Louis Kahn, provided additional source material. Corbet’s fictional László Toth is a rich collage of these real architects’ lives, embodying the tension between idealism and compromise.

Some critics argue that The Brutalist exaggerates the hardship these architects faced, given that many ultimately achieved wealth and fame in America. However, their initial struggles — poverty, cultural alienation, professional scepticism — are well documented. One would think that Breuer, already famous for his tubular Wassily chair, would have eased seamlessly into emigration; on the contrary, it was fraught with challenges. The film stands as a powerful, haunting allegory for post-war architecture and the sacrifices behind every monumental dream.

When asked why Brutalism, Corbet simply answered: 'I was always fascinated by how much people hate Brutalism.' Filmed on a modest budget of under $10 million, its 10 Academy Award nominations are no small feat. ‘Low budget, high pleasure’ — a dictum I always use.

The film’s sense of foreboding — the end of globalism, the rise of resilience, reconstruction, renewed nationalism, and xenophobia — is chillingly apt. Even the poster, showing an upside-down Statue

of Liberty, hints at an inverted world order, offering the immigrant’s disoriented gaze as a metaphor for global change.

The runtime is daunting at over three and a half hours, even with an intended break. Those prone to distraction should watch with headphones and clear their schedule. The Brutalist demands from the viewer — but rewards deeply.

Brutalist architecture: poetry and controversy in concrete

The Brutalist stirred a rush of memories. What first drew me to Brutalism was its sheer honesty — the rawness of materials, the way concrete becomes a plastic sculptural medium; its surface tells stories through the grain of timber or steel formwork. The poetic potential of concrete was something I first discovered through a book on Le Corbusier — the only architecture book I could find in our small-town library.

Brutalism is not for everyone. Stripped of decoration and embellishment, Brutalism forces a focus on form, proportion, texture, and elegance. Today, the public’s distrust of Brutalism persists, fuelled by its perceived coldness and the starkness of exposed concrete. Derived from the French term le béton brut, or ‘raw concrete’, Brutalism is centred around this material (note that it does not stem from the adjective ‘brutal’).

As a second-year architecture student, I designed a Brutalistinspired project with repetitive concrete walls and nearly failed, thanks to the dominance of postmodernism’s ‘humanising’ ethos at the time. Later, working in London, I was mesmerised by the new Lloyd’s of London building by Richard Rogers. Yet, London also revealed the dystopian side of Brutalism — grey, rain-soaked concrete social housing blocks that seemed to drain the spirit. Brutalism, I realised, is inherently polarising: inspiring admiration and criticism in equal measure.

Years later, visits to Louis Kahn’s Yale Art Gallery and Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum of American Art cemented my belief in the profound civic value of Brutalist architecture. These visits were pivotal in shaping the many Brutalist civic structures that our firm would later design.

Pieter Matthews, Founder @mathews_associates_architects www.maaa.co.za

“Corbet’s fictional László Toth is a rich collage of these real architects’ lives.”

One of these is the Javett-UP Art Centre (2019) in Pretoria. Our ‘faceted concrete Mapungubwe mountain’ was, predictably, divisive. One project manager deemed it a ‘monstrosity’ and lobbied the client to clad it. However, visiting internationally-acclaimed architect Peter Rich confirmed the beauty of the raw, handmade quality of our shuttering proof that Brutalism’s authenticity still resonates with those willing to look deeper and closer.

Some of the strongest Brutalist influences on South African architecture began with architect Roelof Uytenbogaardt who studied under Louis Kahn. Should one pass through Welkom, the NG Kerk Welkom-Wes (1965) showcases Uytenbogaardt’s mastery of light and space. Originally a source of controversy within the church, today the building embraces tourists, complete with informational displays explaining its design. A tour of Brutalism in South Africa would encompass other notable sites too: the Afrikaanse Taalmonument (1975) in Paarl, the Windburg Voortrekker Monument (1968) by Hans Hallen, former Rand Afrikaans University (now part of the University of Johannesburg), perhaps a meal at Brasserie de Paris in Pretoria, and a trip to the Nancefield Interchange, with its iconic ‘Musina Hand Bridge’ (now shortlisted for a Fulton Award).

Nobody cares about nondescript or mundane architecture. Great architecture — and Brutalist architecture specifically, elicits opinion, debate, and reflection: sometimes to the point of polarisation, love it or hate it.

Some landscapes are iconic and rich in history, and in those cases, there’s no room for half measures. The STIHL SH 86 vacuum shredder is specially engineered for landscapers who want to put their best foot forward while saving time. The SH 86 clears, shreds and bags organic waste in one go to transform leaves and clippings into mulch that nourishes the soil, preserves moisture and suppresses weeds. With a powerful 2-MIX engine, STIHL ElastoStart, a soft-grip handle and four-point anti-vibration technology, comfort and endurance are standard and non-negotiable.

When the task at hand requires a change of pace, the SH 86 converts into a powerful handheld blower. It’s safe to say, this is an investment for every season, for life!

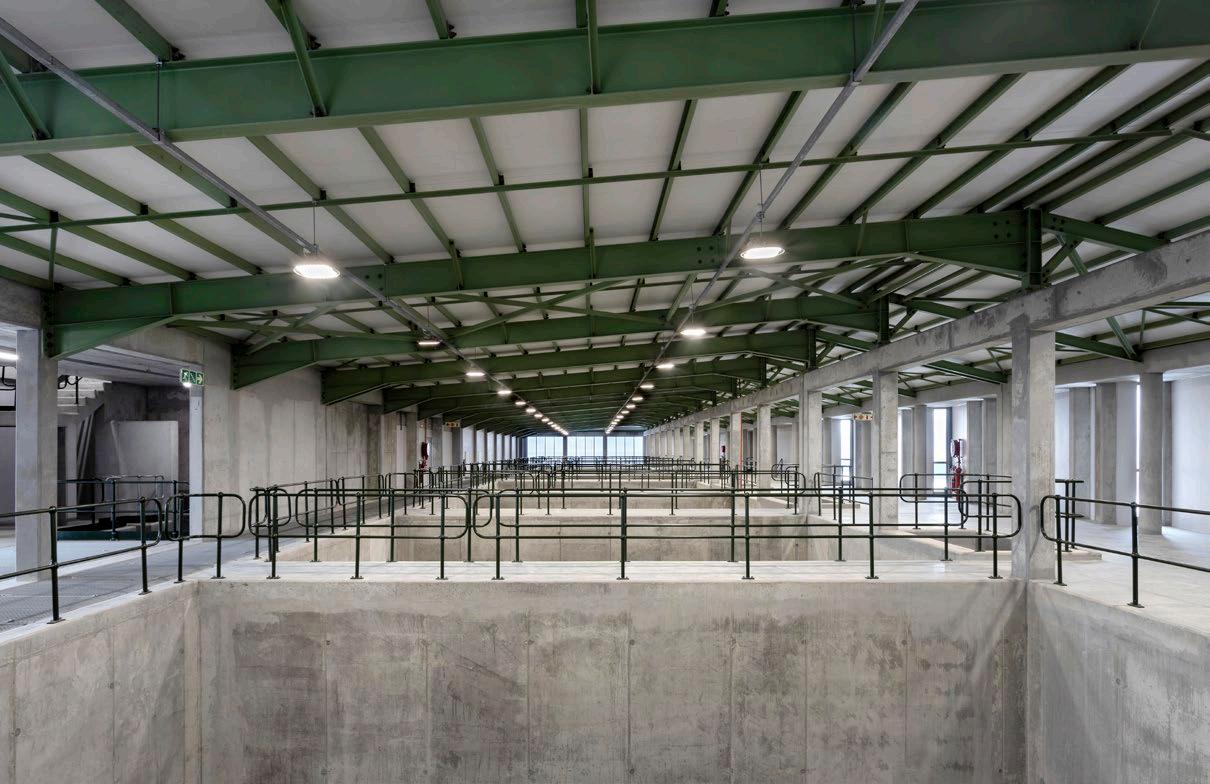

SALT Architects on the Poetics of Water Plants and Control Centres

With infrastructural projects it is easy to forget the users of the building; human interaction is often moved to the periphery of priorities. Generally, there is a perception that these buildings function only as a ‘machine’. But there are numerous people interacting with each other and the machines housed in these buildings. ‘We were adamant that the human scale must be acknowledged and that the environment is inspirational,’ says Jan-Dirk van der Walt, director at SALT Architects.

A large site, like a wastewater treatment works, holds potential urban design value to bring a sense of place to a city. SALT Architects reflects on two of their most distinguished infrastructural buildings in the Western Cape: the Cape Flats Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) Plant and what is officially known as the Athlone Wastewater Plant Control Centre and Blower House Complex.

‘The most common misconception about infrastructure is that anonymity is inevitable,’ says Jan-Dirk. While these infrastructural sites contain process-driven designs, with a logical, fixed planning language, SALT Architects’ approach highlights the poetics of infrastructure. The Athlone Blower House Complex was created in dialogue with the (derelict) Athlone Power Station on the other side of the N2, using principles of order and rhythm and making material references to the building’s context.

At the Athlone Blower House, a sheltered walkway was introduced at ground level. Its interior provides protection from the elements while guiding visitors toward the main entrance. This transitional path unfolds with shifting spatial qualities — revealing glimpses of interior programmes. The passage is animated by the interplay of volume and light shaped by the responsive forms and overhead roof slab. ‘This intervention is probably a favourite of mine; it reveals the understated but special nature of this project,’ adds Jan-Dirk.

“The operational ‘rooms’ are quite impressive, with incredible technology and machinery on display.”

Jan-Dirk van der Walt, Director Gustav

Roberts, Director

@saltarchitects

www.saltarchitects.co.za

“This

transitional path unfolds with shifting spatial qualities — revealing glimpses of interior programmes, animated by the interplay of volume and light.”

The MAR Plant’s design acknowledges the significant embedded energy inherent in the concrete structures required for water retention. With walls and floors up to 600 mm thick, the architects’ sustainable approach focused on durability and long-term resource efficiency. Smaller, thoughtful measures complement this approach, including re-using dune sand from site excavations as backfill, installing low-flow sanitary fittings and waterless urinals, and optimising passive thermal strategies to minimise the need for artificial climate control. These interventions, though modest in scale, reflect a commitment to efficiency and resourcefulness over the plant’s operational lifetime.

While access to the facility is restricted, its design extends beyond utility to celebrate the dignity of infrastructure. ‘By elevating the

experience of its operators and crafting a setting of thoughtfulness and beauty, the project communicates care and inspires pride. As a flagship initiative for the City of Cape Town, the MAR Plant is not just a technical achievement but a powerful statement of the city’s commitment to innovative and sustainable development,’ adds Gustav Roberts, director at SALT Architects.

Its design ensures it can host educational groups and visitors, serving as a tangible example of resilience in the face of water scarcity. The Cape Flats MAR plant exemplifies how architecture can transform essential infrastructure into something greater: a place that honours its users, responds intelligently to its environment, and symbolises the ingenuity needed to address the pressing challenges of our time.

Design is where art and science meet

Belgotex.co.za

Our Elite Acoustic 55 range delivers layered luxury underfoot, combining rich acoustic insulation with the enduring performance of