...hand-crafted oak floors.

From forest to floor

...hand-crafted oak floors.

By now we’ve all come across the ‘dark academia’ trend across films, series, and social media: dominated by gothic architecture, it’s an aesthetic for the reclusive intellectual and keeps an eerie mystery in the air. Academic spaces have continuously been romanticised: high schools are settings for dark fantasies (think: Wednesday or Harry Potter), while university life has infiltrated everything from children’s animations to bingeable Netflix series like The Chair.

There is no doubt that these spaces have an appeal beyond learning itself — and that appeal is architectural as much as it is aesthetic. Physical environments curate experiences — wonderlands, in Hubo Studio’s design of schools, or indoor playgrounds in the case of Meshworks Architecture. Between the two of them, celestial installations and flaming orange slides might be the exact opposite of dark academia, turning schools into places of adventure that make a different kind of fantasy tangible.

We move beyond the building when we speak to Dr Huda Tayob, based at the Royal College of Art in London, for a researcher’s perspective on Education. Her co-curated digital exhibition and ongoing work towards an open-access curriculum invites all to engage in pressing conversations in the architecture field.

Out of the digital space and back into the realm of the university campus, Office 24-7 Architecture gives us a class in designing sleek, lightweight structures and Ikemeleng Architects are inspired by geological forms — by the knowledge to be housed in the building itself.

More and more architects are intuitively, carefully, so gracefully informed by other forms of intelligence (after all, education isn’t only about studying books!). The MAAK rebuilds District Six from (literal) rubble, showing a nuanced understanding of traumatic histories, while Mariam Issoufou Architects questions the segregation of sacred and secular knowledge. Emotional and bodily intelligence are at the forefront of community centres and sports centres, even in the most fraught communities where sensitive design brings the possibility of healing.

These stories, and the issues we curate, are here to open dialogues. It’s what Scape is all about: giving you an ever-evolving forum for many voices, multiple truths, and meaningful exchange. Join the conversation; reach out with your ideas, projects, opinions, and let’s shape the industry together.

Sameeah Editor

• Smooth and soft playground surfacing.

• Ultra-durable, flexible and impact resistant.

• Low maintenance & sustainable.

• Excellent shock absorption with high elasticity.

• Suitable for indoor or outdoor multi-sport areas, playgrounds, landscaping and public parks.

• Allows children to play without risk of injury.

• South Africa’s only internationally compliant wet pour playground surfacing system. (SANS and SABS compliant and accredited).

• International HIC (Head Injury Criteria) standard certified.

• Licensed installers throughout Sub-Saharan Africa.

• Available in 15 colours or multiple blends.

In Their Playful Approach to Educational Spaces, Hubo Studio Finds Logic in Outlandish Ideas

Photographer: Elsa Young

For award-winning architecture firm Hubo Studio, play drives their architects’ designs. Exploring design through the eyes of a child — deeply imaginative, fuelled by creative spirit, and, most importantly, fun — Hubo Studio fosters educational centres that inspire curiosity, creativity, and growth. Their architects undertake thorough research before embarking on a new project. From facilitating workshops with educators to engaging with students, the Hubo Studio team is invested in a holistic design practice that is grounded in the people and communities their projects are meant to serve.

We spoke to architect and founder of Hubo Studio, Asher Marcus, to find out more about the studio's unique approach to designing educational centres.

Hubo Studio has become a leader in the design of educational spaces. Tell us about your journey here.

I’ve never really worked outside of the educational space. My wife and I used to run children’s clubs, and she’s also a paediatric psychotherapist, so we’ve always worked with children. And our whole family goes to school in the morning. For a little while, I worked in the commercial architecture world, but it was quite draining. The projects I was involved in didn’t allow me to experiment and explore different designs. Then I found myself working on the King David Sandton Library project and realised how energised I was by educational spaces. We had a small budget, but I poured my heart and soul into that project, and we created this beautiful wonderland. The truth is, we never stop learning. So, I never really left the educational space because we are all on a learning journey throughout our lives.

What do you think education builds lack?

Much of the way educational spaces are created and viewed is broken. There is often a disconnect between the children and the leadership. But with the way we design, we really see the children as our clients. We are designing for the children, which is why the field research we do is so important to our practice. We host workshops with the students to find out what they want in their educational space and unpack their needs.

What was an exciting insight you’ve gained from a workshop with students?

There was a workshop we did where a lot of children expressed a desire for ziplines and slides at the school. While that concept alone seems ridiculous, what we realised is that the children were wanting a deeper, more interesting connection between spaces. It was really useful to dissect these ideas and to delve deeper into what these ideas point to.

Is there something you’d love to challenge your team to design, and why?

We often work on private schools because they tend to have the opportunity to explore design differently. But I’d love to challenge the team to create an accessible model of what we do to reach schools that really need it and to be able to expand our work of reinventing education on a larger scale. The challenge here is not just creating a dynamic space, but one that is responsive to the school itself and meets the needs of these children. I’d want the design to play into the strengths of that school and explore what learning opportunities there are in less privileged spaces to support these children in becoming innovators and world leaders.

How important is it to have an understanding of pedagogical philosophies as an architect designing in the ‘education’ niche?

For the Redhill Learning Centre, the school follows the Reggio Emelia philosophy, which originates from Italy. What was really

exciting about translating Reggio Emelia into a South African context was that the philosophy doesn’t rely on materiality to exist. It isn’t this exclusive, elitist ideal — it’s very much rooted in everyday practice. It’s quite egalitarian in that way. Because of this, we didn’t have this archive to depend on. When we were designing the school’s Piazza, which is an essential element of Reggio Emelia schools, we were essentially working with something that didn’t exist. We had to marry these two different cultures and imagine an ‘African Piazza’.

How do you see educational spaces evolving in South Africa over the next 10 years? What types of projects do you envisage working on?

We have an amazing opportunity in South Africa to create something very special. People are weirdly progressive and willing to think as world leaders without realising it. We're already leading so much of what the world does. So much is happening here within the educational space. There's a real, earnest desire to progress.

“Hubo Studio explores design through the eyes of a child — deeply imaginative, fuelled by creative spirit, and, most importantly, fun.”

“We really see the children as our clients.”

stiles.co.za | info@stiles.co.za

The Auckland Park Preparatory School STEAM Centre, Designed by Meshworks Architecture, Spotlights Adventurous Learning

A pioneering educational space inspiring creativity and exploration, the Auckland Park Preparatory School (APPS) STEAM Centre provides new spaces for handson learning, moving away from conventional, static learning modes.

The school's interconnected design — merging a maker space, computer lab, performance area, and library — supports a dynamic curriculum promoting curiosity and movement.

Location: Auckland Park, Johannesburg Size: 624 m²

Photographer: Sarah de Pina

With its striking cubic form — 9 x 9 x 9 m at the heart of the campus — the centre serves as a vertical landmark, thoughtfully and seamlessly integrated into the school’s village-like context. Bagged brickwork is a nod to the existing architecture, while an upper-level sanctuary nestles into the tree canopy. The ‘shop window’ of the ground-floor maker space reveals the vibrant learning experience within.

The centre’s internal palette of geometric linoleum, warm carpets, glossy steelwork, natural plywood, and colourful furniture is a bold expression aligning with the rich curriculum. This material choice adds to a spatial sequence that is equally engaging and functional. Diverse learning environments are connected by dynamic flooring and steel balustrades that guide movement through the building. With linoleum flooring and plywood contributing to a low-impact materials palette, the building is a model of sustainability. Openings are strategically shaded and oriented, maximising natural light and encouraging cross ventilation. The centre even generates its own energy.

From the structure of a formal computer lab to the comfort of informal reading pods, the centre supports learner collaboration and solitary work through a range of learning experiences. The maker space is a flexible education zone filled with tools and flooring patterns designed for robotic programming. A mini-auditorium provides an intimate cocoon-like setting for performances, recitals, and audio-visual displays, while the light-filled, multi-level library spreads out along a central trajectory. Features such as playful shelving, a spiral slide, and versatile workstations capture the joy and adventure of learning.

"We started from the premise that educational architecture should cultivate creativity, discovery, and a sense of endless possibility."

MEET THE TEAM

Architects: Meshworks Architecture + Urbanism | Quantity Surveyors: Mi-Consulting Quantity Surveyors | Structural Engineer: Pure Consulting Contractor: Billet Construction Services

Guy

Trangos and Catherine de Souza,

Principal Architects @meshworks.archi

www.meshworks.archi

Flooring: M Farrell & Sons, Gerflor |

Infinity Surfaces Announces the Awardees of the 2025 Future Designers Fund

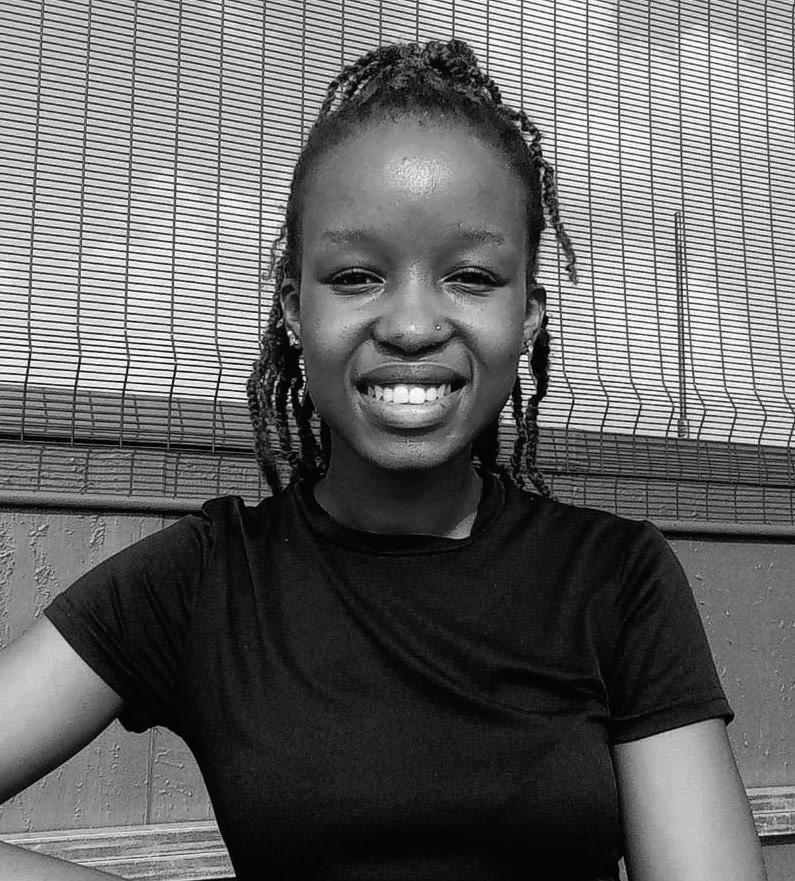

As the industry struts into another year of bold silhouettes and boundary-pushing spaces, Infinity Surfaces pulls back the velvet curtain to reveal its next crowned creatives for the 2025 Future Designers Fund. Zukiswa Mguda and Kgomotso Monnakgotla are the rising stars, tastemakers-in-the-making, and visionaries that will receive year-long support from the initiative to bring their creative ideas to the spotlight.

The next era of African design isn’t on the horizon. It’s already here. And it looks glorious.

Long-lasting impact

Developed by Infinity Surfaces, the Future Designers Fund is a carefully considered initiative that aims to support a shift in the industry and create meaningful, tangible changes in Africa’s design landscape. The fund aims to identify young, talented designers and nurture them into confident, connected creatives. Through an intentional, tailored programme, the fund is built to equip future designers with everything they need to flourish. This may include mentorship, networking, guidance, and practical tools to offer holistic, long-term support in the design world.

Meet tomorrow’s tastemakers

Zukiswa Mguda, a second-year interior design student at Tshwane University of Technology, has an innate gift for transforming everyday spaces into emotive environments. With lines that speak and palettes that whisper, Zukiswa’s design language is refined, personal, and utterly magnetic.

Enter Kgomotso Monnakgotla, a third-year interior design student at the illustrious BHC School of Design. Already turning heads with her polished concepts and daring compositions, Kgomotso doesn’t follow trends — she orchestrates them. Her flair for detail, coupled with an infectious passion for problem-solving through design, makes her a powerhouse in the making.

Designing a better future

More than a philanthropic gesture, the fund demonstrates a commitment to shifting the design landscape in Africa. Infinity Surfaces, while rooted in Italian craftsmanship and global innovation, is fiercely invested in nurturing local brilliance. Because the future doesn’t just happen. It’s designed — carefully, creatively, and with purpose.

EUROPEAN

DESIGNER BRANDS

Office 24-7 Architecture's New Teaching and Resource Centre Welcomes Learning and Leisure

When the Johannesburg General Hospital and its adjoining medical school complex opened in 1979 and 1983 respectively, the spaces were fraught with apartheid-era segregation and racially discriminatory practices.

Both the hospital and medical school are brutalist concrete structures, their cold forms symbolic of their alienating nature. After all, the hospital only opened to all races in 1990 and, in 2008, it was renamed in honour of activist Charlotte Maxeke.

Location: Parktown, Johannesburg

Size: 2 485 m²

Photographer: Natasha Dawjee Laurent

Today, the University of Witwatersrand Faculty of Health Sciences and the Medical School face growing student numbers and the need for more teaching space. However, the Faculty and Medical School, attached to and located south of the Johannesburg Academic Hospital, are situated on a tight site where there is little space for growth. Office 24-7 Architecture, founded by Nabeel Essa, led the project for the new Teaching and Resource Centre that offers teaching and study spaces for large numbers of undergraduate students. This included new construction as well as additions to existing buildings. It also entailed the renovation of two existing spaces in the Phantom Heads and Prosthodontics Laboratories, housing the largest and most up-to-date oral health simulation facility in the country.

The rooftop addition needed to be lightweight — not an easy requirement to fulfil. Yet this constraint brought opportunities to create a distinct architectural language and explore lightweight construction that regulates heat and insulates sound. As a result, the building was assembled as an entirely steel frame structure (composed of steel sheeting, insulation, and dry wall), with negligible use of concrete and brickwork. The structure offers openness, fluidity, and ephemerality against the hard, heavy, and dark spaces of the 1979 apartheid buildings.

The glazed concourse, naturally lit through a clerestory strip window, celebrates light in an environment where interior spaces were previously dimly lit. The atrium evokes this sense of lightness induced by the building’s new form too: sitting on a bulky existing concrete structure, the L-shaped atrium aligns with the balcony, sharing the same views and social connectivity brought by visual connections and layering. The porosity of the new additions shows the transformed attitude to educational spaces that welcomes, rather than alienates.

The stairs are not only entry points to the new building — they’re conduits between the open courtyard and the balcony, creating multiple fluid connections to the existing building and open-air green space. Designed with a sculptural quality and fine steel detailing, the staircase allows generous movement and invites social encounters through its built-in seating. The exterior fireescape staircases are celebrated and integrated with everyday circulation.

Architects: Office 24-7 Architecture | Quantity Surveyors: C.R.M.P. | Structural Engineer: Nurizon Consulting Engineers

Project Manager: SRSQS Quantity Surveyors | Acoustic Engineer: LINSPACE | Contractor: GVK-Siya Zama Construction

"The structure offers openness, fluidity, and ephemerality against the hard, heavy, and dark spaces of the 1979 apartheid buildings.”

Rethinking traditional principles of quiet study, the project emphasises group study and inter-student exchange as fundamental to learning. The classrooms have stackable dividing walls, allowing for multiple configurations: four extra-large classrooms open into one large exam venue, a core requirement for the university. While these arrangements are more formal, they’re complemented by the large, open concourse providing generous spaces for a relaxed study area and social interaction.

Integrating functions

In their future-forward architectural move, Office 24-7 Architecture centres sustainability: the north-facing roof houses solar panels and is designed to harvest rainwater, which is used to flush the toilets and water the garden.

Where the campus previously lacked open, green space, the new building defines, enhances, and extends the small, rectangular

patch of outdoor recreation space. The new structure’s steep, angled roof positions this open space as an entry threshold and courtyard: its angled edges frame the area as a sheltered oasis. Shaped and raised, the structure houses an open-air study and leisure space. From the concourse and cantilevered balconies, students now have 180-degree views of Johannesburg’s impressive city skyline.

Flooring: Gerflor | Ironmongery: dormakaba | Roofing: Global Roofing Solutions | Acoustic Partitions: Aluglass Bautech, Hufcor

Operable Acoustic Partitions | Surfaces: Salvocorp | Ceramic Wall Tiles: Union Tiles | Paint: Dulux | Ceiling Panels: OWA Acoustic Ceilings | Furniture: Cecil Nurse | Custom Tables: Trespa by Labfurn | Aluminium Doors and Windows: HBS Aluminium Systems, Govenders Aluminium & Glass | Insulation and Dry Walls: Saint-Gobain Africa

GAPP Architects and Urban Designers’ Masterplans and Institutional Builds Shape South Africa’s Educational Future

Rooted in flexible spatial frameworks, adaptive architecture, and visionary urban design, GAPP Architects and Urban Designers delivers educational spaces that are inclusive, sustainable, and globally competitive. At universities and public schools around the country, they create community-focused spaces inspiring learning and connection. The process begins with a thorough analysis of existing conditions, community needs and aspirations, and planning initiatives, ensuring designs align with institutional visions while remaining adjustable for future demands.

The masterplan

GAPP’s flexible spatial development frameworks establish clear movement networks and vibrant open spaces for social and academic interaction. These frameworks prioritise walkability, connectivity, and campus identity, incorporating central gathering spaces — such as landscaped gardens or public squares — to foster community and institutional pride. GAPP’s status quo analysis of the North-West University (NWU) premises identified sprawling residences and disconnected academic cores at the Mahikeng and Vanderbijlpark campuses. At Mahikeng, a reconfigured ringroad and pedestrian network now transform the university into a highly walkable core. Simultaneously, Vanderbijlpark’s east-west pedestrian corridor anchors a multi-purpose sports hall, framed by a primary public square to create a campus heart.

Multipurpose lecture facilities

Students face their most challenging learning in lecture halls. Universities are known for fast-paced lectures and students must stay alert to keep up. There is also a sense of excitement about a new class, a new face at the front, and the whirlwind of knowledge that is yet to unfold. Auditoriums are therefore an essential part to curating this experience.

However, GAPP's design, focused on creating adaptable buildings that support active and hybrid learning, goes beyond traditional models. At the NWU Potchefstroom campus, GAPP’s designs transform traditional lecture halls into mixed-practice venues incorporating acoustic panelling, student whiteboards, and digital infrastructure for hybrid teaching. Existing foyers become informal learning hubs, with study pods and meeting zones featuring sustainable materials, operable windows for air quality, and thermal insulation for energy efficiency.

At NWU, the adaptive reuse of a former engineering training faculty into offices and multipurpose lecture facilities for the Economic and Management Science Faculty resulted in a triple-volume atrium. The latter forms the main entrance along pre-existing movement routes, with its placement reinforcing the open lawn area as a key spatial asset.

GAPP’s design philosophy advocates for both environmentally- and human-conscious solutions, creating spaces that harmonise with their natural and built contexts. Further north of the country, Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley is home to The Eco Centre, which serves as the university’s recycling and maintenance hub and was designed in line with green building principles. Other sustainable principles, seen in the NWU Masterplan, reduce the need for new construction. At UWC and UCT, green building certifications and sustainable materials ensure long-term resilience, while the firm’s public school projects feature solar-powered systems and waterefficient landscaping, aligning with environmental and budgetary realities.

GAPP Architects and Urban Designers’ approach, rooted in flexible spatial frameworks and adaptive architecture, succeeds in transformative urban design. From the holistic NWU masterplan to multipurpose lecture halls across South African campuses, GAPP shapes an educational legacy that empowers future generations. Their work in public schools further demonstrates their versatility, creating adaptable, community-focused spaces that inspire learning and connection. Notably, this comprehensive approach extends beyond campuses and schools as they apply it to a wide range of urban design interventions.

@gapp_ www.gapp.net

Words by Sameeah Ahmed-Arai

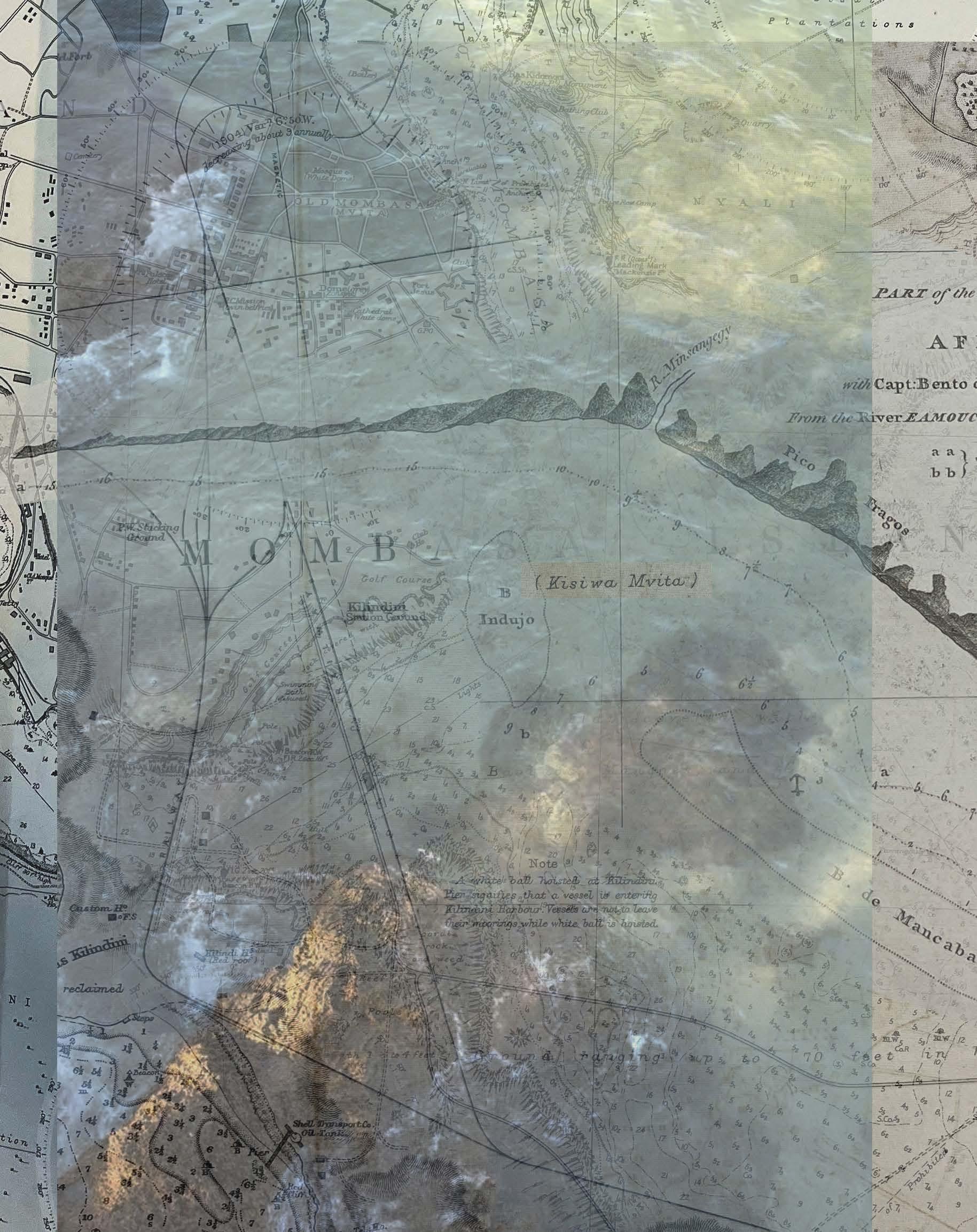

‘the whole library of the Maroons / exploded in a smoke…,’ writes poet Dannabang Kuwabong. He references two libraries: one in Dominica, burnt to the ground by rebels who destroyed millions of books on marronage, and one in Ancient Egypt. Calling these rebels ‘architects of amnesias’, Kuwabong compares the Dominican library to the historic library in Alexandria, which is believed to have been set alight by Julius Caeser when he invaded the region in 48 BCE: ancient science, philosophy, and histories lost with it.

Closer to home, the ashen University of Cape Town Jagger Library was, in April 2021, a site of collective heartbreak as scholars, students, and citizens mourned the loss of special collections, mostly African studies, and manuscripts not yet digitised. The city felt the grief of what was lost — at what we didn’t know and perhaps never will.

Location: Cape Town, South Africa

How do you re-build what has vanished? Across District Six, barren lands are stroked by dry grass, the air filled with weighted memory. Since the apartheid government exiled the neighbourhood's mixed population to the outskirts of the city in the 1960s, the area has never been the same. After the suburb was declared 'whiteonly', 60 000 residents were forcibly removed and their homes bulldozed.

If it’s true, as Dannabang Kuwabong says, that the library is a pillar of civilisation itself, and its inhabitants — destroyers or preservers — the ‘makers of civilization’, architects too must ask what form of civilisation the library retains: which memories, whose stories, and whose lives it will touch.

In The MAAK’s recent project, rubble from the demolished homes and local clay were used to create bricks for the construction of a new library at Rahmaniyeh Primary School in District Six. The structure literally embodies material memory — preserving what is left, embracing the fullness of the site’s history despite the lingering violence and grief. Their collaborative art-architecture exhibition, ‘Clay, Library, Land Studies’, presented at Cape Town Design Week last year, displayed clay tiles painted by the schoolchildren tasked with creating patterns inspired by objects of meaning. Integrating his practice with community, Max Melvill, who co-founded The MAAK along with Ashleigh Killa, compares their architectural approach to ‘midwifery’ — a vehicle to rebirth, rather than a destination.

In the next ‘act of listening’, as Max calls it, the architects were companions of the students at the school, together designing bookshelves for the interior of the building. During the workshops, imagination had no limits: from a rainbow-cloud-lava tower to castles and dinosaur-shaped shelves. Together with the Otto Foundation and Cape Town–based furniture designers Pedersen + Lennard, the team created a modular bookshelf range informed by the students’ visions. Made from folded steel and recycled plastic board, it is a playful, colourful sight infused with a youthful soul. Titled the ‘Rahmah-Rama bookshelves’, this limited-edition furniture is available for the public to collect for their own libraries.

Next to the bookshelves, a reading pit is submerged into the floor, a sunken circle lined by a pattern of bricks. Its circular form encloses and protects — like a compassionate embrace. Rahmah, from the Arabic term meaning mercy or kindness, is integrated into the library’s name and forms, a reminder to rebuild with care and kindness, even in the midst of collective dispossession.

Location: Pretoria, South Africa

In South Africa, oral histories and material culture — non-written forms — are just as important to preserve knowledge. Universities have long understood this, with their art centres, museums, and galleries preserving a different form of intelligence — a different kind of ink and mark. Mathews + Associates Architects proposes an architecture to protect public knowledge at the University of Pretoria’s Javett Art Centre where squares and galleries are designed for performances, artwork, and installations. After all, practitioners in various parts of Africa are questioning the library’s sole purpose to store words, with many seeking to create a ‘visual library’ typology.

Conceived as a ‘vault’ protecting Mapungubwe artefacts from the 11th and 12th centuries, the centre is marked by a bold, sculptural mass of exposed concrete referencing the Mapungubwe hill where the objects were found. Designed by architect Pieter Mathews who sees the provocative nature of brutalism as generative, its harsh exterior reflects the rugged environment that the Mapungubwe artefacts, permanently on display, originate from.

The art centre preserves visual and written material as a space for book and film clubs, creative writing workshops, sculptures, mixed media artworks, and notably, Willem Boshoff’s word artistry. The Word Woes exhibition, like Moonwords (38 Khoisan words for the moon), uses spatiality to re-represent language. Boshoff’s words are laid out in cabinets, above bookshelves, and against walls, a chance for the gallery — acting as a ‘visual library’ — to perform a questioning where words and architecture coalesce.

“Conceived as a ‘vault’ protecting Mapungubwe artefacts from the 11th and 12th centuries, the centre is marked by a bold, sculptural mass.”

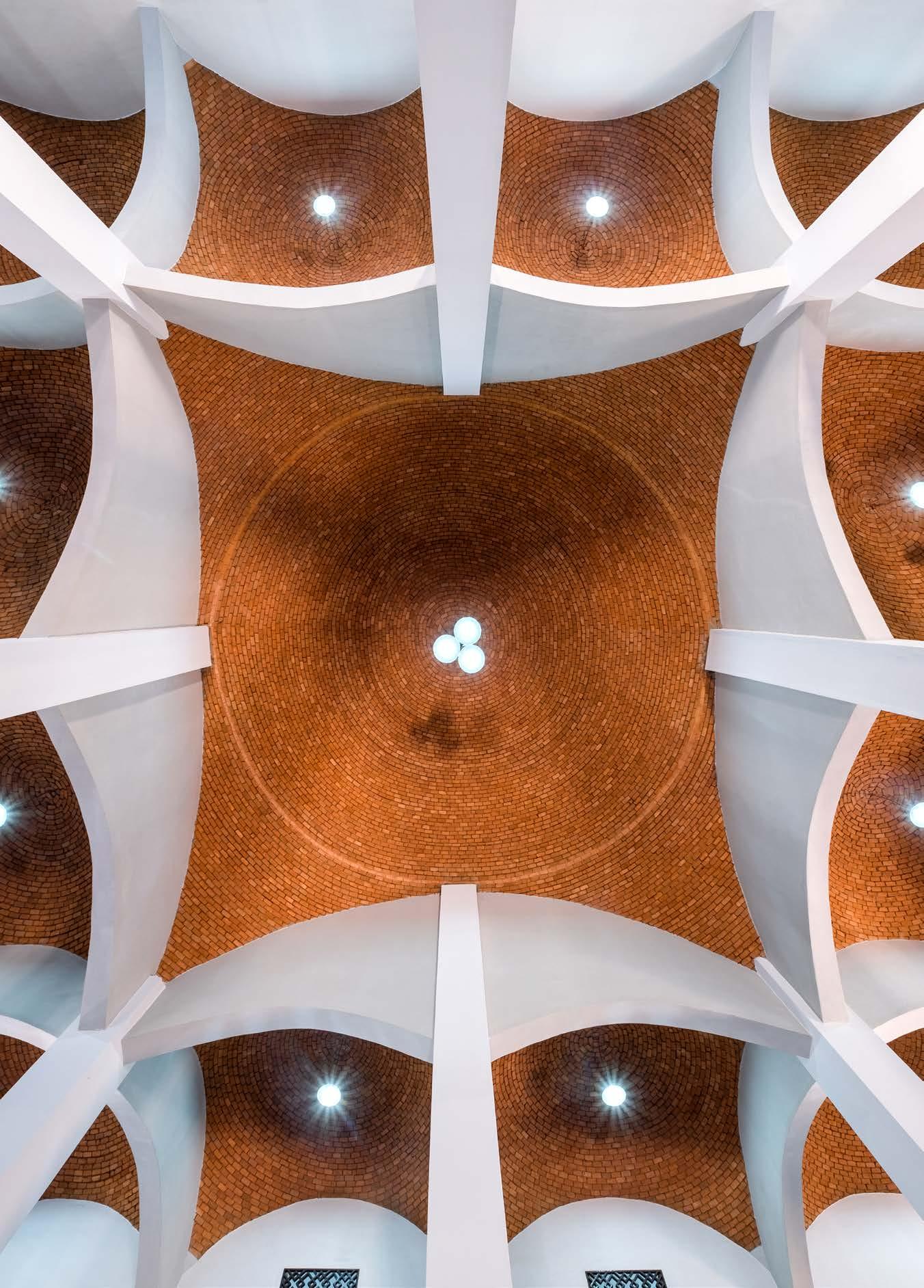

Location: Dandaji, Niger

What is the future of this ancient architectural form? In 2027, a new presidential library in Liberia, dedicated to the country’s former president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, will be opened to the public. Featuring an exhibition space designed by South African architect Sumayya Vally, the library is informed by Mariam Issoufou Architects’ localised approach.

The team has experience in knowledge preservation, having previously interrogated the demarcation of sacred and secular thought when they transformed a derelict mosque — abandoned for 20 years — into a flexible library. Hikma Library, located in the village of Dandaji, was named after Bayt al-Hikma, or House of Wisdom, a historic library from the 9th century where the Abbasid civilisation documented their wealth of scientific discoveries and theological studies. Compressed Earth Bricks (CEB) made from local soil were used, improving thermal performance and lowering energy consumption.

In undoing the binary between secular and sacred, Mariam Issoufou Architects reminds us that every form of knowledge has its place in the library, filled for wisdom once more.

Photographer: James Wang

“Hikma Library, located in the village of Dandaji, was named after Bayt al-Hikma, or House of Wisdom, a historic library from the 9th century.”

The Nature Conservation Building at the University of Mpumalanga Holds a Mirror to Geology

Ikemeleng Architects’ vision for the Nature Conservation Building unites robust material expression with spatial flexibility. Drawing inspiration from the region’s geological character, the Nature Conservation Building references stratified rock formations through three prominent projecting brick bands.

These horizontal elements are visually separated by continuous aluminium ribbon windows that allow for generous daylight and reinforce the layered design language.

Location: Mbombela, South Africa

Size: 3 757m2

Anchored like bedrock

Commissioned to serve the growing needs of the University of Mpumalanga and designed specifically for the Nature Conservation Programme within the Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Sciences, the building integrates lecture venues, laboratories, and administrative offices into a flexible, research-focused academic hub.

The building’s base — housing the lecture theatres — anchors the structure like bedrock, while cave-like voids, carved into the façades, provide shade and relief from the intense Mpumalanga sun. A deliberate material contrast distinguishes the outer ‘hard shell’ façades from the softer, more transparent courtyard-facing walls, supporting a conceptual interplay of exposure and protection.

Connecting axes

As one of the earliest buildings on the new West Campus in Mbombela, the structure plays a critical urban design role. The main entrance, located at the northeast corner, connects directly with the campus's central axis, while additional entries on the north, south, and west sides of the lower ground floor promote permeability and easy circulation.

The Lower Ground Floor contains two raked lecture theatres, a seminar room, and two large flat-floor lecture venues that can be subdivided for varied academic use. These open onto a landscaped internal courtyard, envisioned as a breakout and pause space. On the Upper Ground Floor, a welcoming reception, academic offices, and seminar rooms define the main arrival level. The First Floor continues the academic layout, with the north wing housing offices and seminar rooms, and the south wing dedicated to open-plan workspaces and specialist postgraduate laboratories.

Purposeful design

Clay face brick dominates the exterior, detailed with corbelling, stepped courses, and perforated screens to add texture and promote ventilation. Black aluminium-framed glazing complements existing campus structures and creates a bolder aesthetic.

Internally, lecture venues prioritise acoustics with carpeted raked floors, timber acoustic panels, and aluminium lay-in ceilings. In labs, seamless epoxy floors and Trespa worktops ensure durability, hygiene, and chemical resistance. Circulation areas and wet zones use porcelain tiles for their strength and low maintenance.

Energy efficiency is addressed through recessed glazing for shading and naturally ventilated ablution blocks. Each of these facilities feature perforated breeze walls for natural ventilation and exceed the required fenestration-to-floor area ratio, enhancing user comfort and sustainability.

Purposeful yet understated, the Nature Conservation Building delivers a sustainable academic environment tailored for research, collaboration, and long-term growth.

“Designed specifically for the Nature Conservation Programme within the Faculty

of Agriculture and Natural Sciences, the building integrates lecture venues, laboratories, and administrative offices into

a flexible, research-focused academic hub.”

Brickwork: Corobrik | Ironmongery: dormakaba | Ceilings: Saint-Gobain Africa | Tiles: Union Tiles | Carpets: Belgotex Auditorium seating: Rodlin Design | Sanitaryware: Vaal Sanitaryware, Geberit, Cobra, Franke, Grohe, Duravit | Lab Joinery: Trespa by Labfurn | Steel: Safintra | Toilet Cubicles: Cubicle Solutions | Furniture: Cecil Nurse, Bulk Office Solution | Acoustic Panels Joinery: ébéniste

MEET THE TEAM

Architect: Ikemeleng Architects | Structural Engineer: Calliper | Civil Engineer: GMH Consulting Engineers

Mechanical and Wet Services Engineer: Muteo Consulting | Electrical Engineer: PLP Consulting Engineers

Landscape Architect: kwpCREATE | Contractor: Trencon Construction | Project Managers: University of Mpumalanga | Cost Controller: Siyakha Quantity Surveyors | Environmental Consultant: Taktho Environmental Strategy | Health and Safety: Roamik | ICT and Security: Implementing-IT | Data: Digital Fabric

“Cave-like voids, carved into the façades, provide relief from the intense Mpumalanga sun.”

Modern education spaces need intelligent climate control for comfort and focus. The Samsung 360 Cassette meets these needs with even, quiet airflow - perfect for classrooms, auditoriums, and more!

Blends seamlessly into any educational environment with a sleek, customisable aesthetic complimenting any architectural design.

Delivers fresh, allergen-free air - with an optional purifying panel — to support better focus, well-being, and overall indoor air quality in learning spaces.

Energy-efficient performance with digital inverter technology that reduces power consumption while maintaining optimal temperatures.

Sustainable choice, using R32 refrigerant for a lower environmental impact and supporting green building goals.

Custom airflow control with wide 360° coverage, ensuring consistent comfort in large spaces like lecture halls and auditoriums.

Built for diverse educational environment s - whether it’s a lecture hall, dormitory or recreational facilities.

Reliable in any climate, operating in extreme temperature conditions from -15°C to 50°C, making it suitable for all regions.

For your next energy-efficient project, discover the ideal air conditioning solution with Fourways Group:

JHB & Central: (011) 704-6320 · Pretoria: (012) 643-0445 · CPT: (021) 556-8292

Gqeberha (PE): (041) 484-6413 · EL: (043) 722-0671 · KZN: (031) 579-1895

The New Student Residence by TwoFiveFive Architects Is at Home in This Boho-esque Suburb

Observatory, or ‘Obs’ as it’s more commonly known, is one of Cape Town’s popular student hubs, with thrift stores, vegan cafés, bars, and record stores lining the streets. The area’s eclectic mix of architectural styles — industrial builds next to Victorian-era homes — makes it a charming, vibrant place to reside.

For students, Obs is often seen as a moderatelypriced suburb offering a wealth of experiences and easy access to the University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital. Over the years, Observatory’s rich cultural scene opened it up to artists and young professionals seeking the suburb’s diverse community and bohemian atmosphere.

Location: Observatory, Cape Town

Size: 1 989 m²

Photographer: Paris Brummer

“The area’s eclectic mix of architectural styles — industrial builds next to Victorian-era homes — makes it a charming, vibrant place to reside.”

9 on Nares, an affordable student housing project realised by TwoFiveFive Architects, is situated in this sacred hub. Meticulously designed with a budget-sensitive approach, the residence uses bricks in new ways, achieving aesthetic solutions to costly production.

Ordinary turned artistic

The façade of the 45-unit development is adorned with NFX Imperial bricks (Non-Facing Extra), which are artfully arranged to create a tapestry of patterns. This design choice not only brings a rhythmic aesthetic to the exterior but also contributes to the building's structural integrity. The façade's ‘push and pull’ dynamic creates a sense of hierarchy and form, enhancing the building's visual appeal. NFX bricks, known for their superior durability and moisture resistance, were chosen over the more commonly used NFP (Non-Facing Plaster) bricks due to their cost-effectiveness. The creative use of this ordinary material results in a playful, engaging façade, with each brick pattern transitioning into the next.

Built with character

Much like Observatory’s architectural and cultural make-up, 9 on Nares is both quirky and charismatic. Adding to the building's contemporary charm, royal blue aluminium frames are used for the windows and other fenestrations. Infusing the façade with a vibrant pop of colour, these frames create a striking contrast against the red and brown hues of the brickwork.

In embracing the eclectic energy of the suburb, the development blends with the neighbourhood's rich character, contributing to its appeal.

Andre Krige and Theo Kruger, Principal Architects

@255architects www.twofivefive.co.za

MEET THE TEAM

Architect: TwoFiveFive Architects | Structural Engineer: A19 Consulting Engineers | Electrical Engineer: FRAME Consulting Engineers Civil Engineer: Engineering Advice and Services | Principal Contractor: HFO Construction | Fire Engineer: De Villiers & Moore Consulting Engineers

Bruce Wilson Architects Drives CommunityCentred Design at The Baker

The Baker is a co-living development designed specifically for students, but far from the cramped or uninspiring housing typically associated with student life. This considered, design-led scheme offers 44 rooms across eight individual houses, each crafted to blend privacy with connection.

Brought to the market by Revo Property, imagined by Bruce Wilson Architects, and tailored by Maison and Marble, The Baker sits in one of Cape Town’s most vibrant and well-connected student neighbourhoods, a sweet spot between academic convenience and urban energy.

Location: Observatory, Cape Town

Size: 1 000 m2

Photographer: Paris Brummer

“The Baker doesn’t just meet the brief — it reframes it.”

While the individual rooms offer generous proportions and privacy, the communal areas make The Baker its own. Co-living here isn’t for cost-efficiency — it inspires the design. Kitchens, lounges, and outdoor spaces are tailored to encourage interaction and stimulate student life beyond the campus. The accommodation offers room to gather, study, and retreat: valuing communal space in equal measure to private space. At The Baker, your ‘home’ doesn’t end at your bedroom door.

Designed by Bruce Wilson Architects, The Baker balances modern design thinking with the practical needs of student life. Each of the eight houses brings something slightly different to the space, and together they form a cohesive development.

Responsive design language

The architectural language is contemporary, but it doesn’t shout. Interiors are understated and smart, finished to a high standard, and provide a level of comfort often not found in student accommodation. Different room types cater to various budgets, but across all 44 rooms, the commitment to quality remains consistent.

The entire development is also solar-powered, reducing energy costs and ensuring continuity during load shedding — a nonnegotiable for student life in South Africa.

MEET THE TEAM

Architect: BWA | Interior Designer: Maison and Marble | Project Management and Quantity Surveyors: PepperGreen Consulting

Anchored in community

For a generation of students increasingly looking for more than just a bed and desk, The Baker offers a place to connect and grow — both academically and personally. Recognising that a student’s environment directly impacts their wellbeing and performance, The Baker answers the challenge with considered spaces that foster a sense of community.

As education evolves and learning becomes more hybrid, more flexible, and more self-directed, the spaces that support students need to evolve too. The Baker doesn’t just meet the brief — it reframes it. By anchoring its architecture in community-minded design, The Baker sets a new benchmark for what student accommodation in Cape Town can be.

“...a sweet spot between academic convenience and urban energy.”

|

|

|

CCNA and TKLA Use

Methodologies for Healing in Cape Town’s Most Volatile Suburb

With the intention to co-create a place that supports wellbeing within a safe, contained environment, Charlotte Chamberlain and Nicola Irving Architects (CCNIA) and Tarna Klitzner Landscape Architects (TKLA) designed the Hope Centre in Delft, supporting social justice in a vulnerable suburb.

Delft, like many other townships, was engineered during apartheid to house black communities using infrastructure and natural systems as a divisive means — to separate and to control. The area is further alienated from surrounding neighbourhoods by buffer zones of undeveloped open spaces and poor public transport. Lack of adequate infrastructure and opportunity create a cycle of poverty, leaving the area rife with antisocial behavior and high crime rates. The Hope Centre endeavours to address environmental and social issues, which impact the health and wellbeing of citizens.

Location: Delft, Cape Town

Photographer: David Malan

Architects: Charlotte Chamberlain and Nicola Irving Architects (CCNIA) | Landscape Architects: Tarna Klitzner Landscape Architects (TKLA) | Eco Design Architects: Andy Horn | Project Manager: Violence Prevention Through Urban Upgrading (VPUU) | Civil Engineer: Naylor Naylor & Van Schalkwyk Consulting Engineers | Structural Engineer: Alan Hendrie | Electrical Engineer: IME Consultants Quantity Surveyor: Grey Quantity Surveyors | Irrigation Designer: Arid Earth | Main Contractor: Longworth & Faul, Edge to Edge Construction | Landscape Contractor: EnviroMend

“Design interventions speak to notions of being held, comforted, grounded and protected.”

Having previously worked together on numerous collaborative projects, CCNIA and TKLA laid clear foundations for the project by employing a conscious methodology of iterative engagement, collaborating with numerous organisations and consultants to firmly embed the project in the context of the surrounding environment, and creating a space that complements the non-profit's work of providing healthcare, HIV support, and aid for children and families.

As townships developed on the Cape Flats during apartheid, the existing fauna and flora habitats were obliterated. Today, we are left with a series of sandy, windswept neighbourhoods. These barren environments exacerbate the sense of isolation and separation the community faces. In looking for a methodology to regenerate the natural and social landscape and provide opportunities for green, healthy spaces, the architects sought to interrogate the area at a very local level.

Through collaborative workshopping, the process focused on iterative conversations and shared drawing, collaging, and modelling to create a platform for communicating and evoking ideas. This methodology begins well before the brief is defined and continues beyond the project's completion. It is a potentially messy and open-ended process, but it holds the possibility to share great ideas across collaborators.

Using this methodology, the team was able to identify emerging emotional conditions, which were developed into active design informants, framed within desires of wellbeing. The architects' collaborative design responds to emotions and desires while leveraging the interdependence between inside and outside spaces to create spaces of healing.

Design interventions speak to notions of being held, comforted, grounded, and protected, with the intention of addressing feelings of exposure and isolation that users in vulnerable environments experience. Through this project, the team moves beyond the mere provision of corporal safety. In the words of Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa, ‘Buildings do not merely provide physical shelter... they also need to house our minds, memories, desires, and dreams.’

@ccnia_architects www.ccnia.co.za www.tk-la.co.za

Reliability is at the heart of our industry, and our Professional range is no different. Product innovation coupled with our value added services gives you a distinct advantage.

Our complete coating system, spanning preparation, trim, wall and textured coatings, is designed to ensure guaranteed product performance and value from start to finish.

All Plascon Professional products with the Ecokind logo have VOC levels within the GBCSA standards for Green building ratings.

Designed for professionals.

Every architecture school is powered by its researchers who actively shape architectural pedagogy, research, and history. From probing the ghosts of Cape Dutch architecture to developing a platform for African artists, Dr Huda Tayob uses the past as a tool to intervene in our current world.

Huda works as a Senior Tutor at the Royal College of Art in London, and she has previously taught at universities in the UK and South Africa, including the Bartlett School of Architecture and the University of Cape Town.

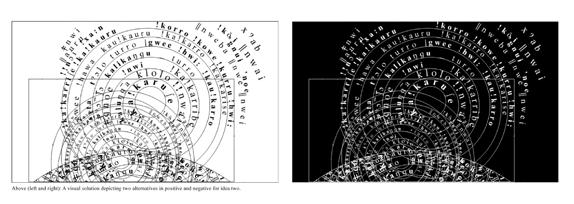

We connected with Huda to speak about her co-curated, open-access curriculum, Race, Space, and Architecture, and the digital exhibition, the Archive of Forgetfulness, which featured 22 artworks and six regionally curated projects from African artists.

“I work on Cape Dutch architecture, and when I started to look at the archives and early architectural histories, I came across stories of slave ghosts.”

Huda remaps borders and archives, multiple projects at a time. With her focus on migrant and subaltern architectures in Africa, she stays rooted to the continent. As a South African and descendant of migrants herself, Huda interrogates history from a position firmly based in her home country, but she is by no means limited to it.

You've previously mentioned that the digital exhibition, the Archive of Forgetfulness, is informed by practices of care. What does care in architectural research and pedagogy mean for you?

There are many ways to think through practices of care. In this project, it is present in the way in which the project unfolded as a collaborative practice with many involved and as a way of thinking through archival care. The theorist Abdoumaliq Simone talks about ‘practices of peripheral care', referring to practices amongst marginal groups at urban peripheries where people are living with very limited means, where there's an ethics of relating to and caring for each other that's part of daily life. This often involves multiple, small acts that are not always grand gestures and yet are central to making life liveable, often in very difficult contexts. I think that is just one way we see practices of care play out in many of the projects featured in the Archive of Forgetfulness.

Where else have you seen this dynamic?

One of my projects focuses on Cape Dutch architecture, and when I started to look at the archives and early architectural histories written in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I came across stories of ghostly figures who appear amongst these houses. These ghosts are often female slaves who were involved in domestic labour, caring for homes and owners. It is said that they are still heard up until the present in some of these homes. In archival sources there are references to a woman's footsteps being heard up until the 1960s. Interestingly, in one of the sources there is a comment made that ‘if you care, you might hear’ these footsteps.

There are stories of a woman in a garden with a Batavian brick oven, for example. This gives us a material trace to geographies, empire, and histories of slavery. But, as most of us know, even when you visit these sites in Cape Town there's very little acknowledgment of this history, while the legacies of slavery are still very much present in terms of relations of power and labour at these sites.

So how do we revisit those houses? How do we include the stories of people who cared for, maintained, and often constructed these buildings, who are not necessarily immediately present in archives or in mainstream versions of thinking about preservation and heritage?

It sounds like the ghostly figure is a really useful tool to approach spaces and research. It’s such an embodied kind of metaphor as well. Is there any resonance between this and your work on migrant architectures?

The figure of the migrant in classical urban literature, but also in a South African space, tests the limits of inherited ideas of the city. You could say that, in some ways, the ghostly figure is also similar. It's a kind of revisitation of theories and spaces with this figure who speaks to the limits of architecture and, in the case of the ghosts specifically, the limits of history. The figure of the ghost disrupts time; she is a social figure.

places and pasts. Mahmoud Darwish’s work is a really powerful text that draws out questions of memory and remembering. ‘Memory for Forgetfulness’, which was written in 1982 during the siege of Beirut, is a prose-length poem which moves from the everyday and mundane aroma and taste of coffee to the sirens and sounds of a city under siege.

The poem is a reminder to think about how history is told. Darwish’s writing reminds us of the importance of thinking and working through multiple temporalities, moments, and the collisions of history and time. And to understand that the material worlds around us are not innocent in these moments.

The open-access curriculum, Race, Space, and Architecture, which you co-curate with Suzanne Hall and Thandi Loewenson, makes learning and knowledge more accessible. My sense is that it could filter out to people who are not students in a traditional sense, but want to be part of this active process of learning?

Race, Space, and Architecture was initially developed with Suzi Hall through a research project, and in 2020 we were joined by Thandi Loewenson. It has been a useful project to open up wider conversations on the relationship of race to architecture and urban space.

In South Africa we use racial terminology as part of our everyday language; it’s very commonplace in social life. Yet we often don’t step back to consider and question the implications of institutional or structural racism especially within architecture, both in industry and academic institutions.

“The figure of the migrant, in classical urban literature, but also in a South African space, tests the limits of these ideas.”

The open-access curriculum was a fruitful way to think through these questions. It's, exactly as you say, about the boundaries around who's studying and who's not, but also how you access knowledge differently depending on where you're based — institutionally and geographically.

Speaking about archives, your co-curated project, the Archive of Forgetfulness, draws on Mahmoud Darwish's poem. Where do you see words and architecture being placed together, and what does it signal to us about transdisciplinary work?

Thinking with fiction and poetic texts has been an important way to think with other forms of storytelling, and to question how we narrate

Race is structural, but it is constantly being produced and reproduced, so it's changeable. That's quite significant. The curriculum is organised in six frames, each a transitive verb that draws attention to this fact: centralising, circulating, domesticating, extracting, immobilising, and incarcerating. The racialisation of space is not inevitable; it relies on this reproduction, with the implication that these structures can also be disrupted.

Urban Think Tank Empower’s Social Architecture Mobilises Resilience and Ambition

Following Urban Think Tank Empower’s award-winning ‘Empower Upgrade Model’, the team turned what was once a dense informal settlement into a resilient urban ecosystem, housed within a 520 m² community facility.

By formalising homes for residents using efficient rowhouse typologies, significant space was freed up for shared infrastructure: a community centre, a public playground, and critical social amenities. This strategic densification enhances the liveability of the space through education, recreation, economic opportunity, and community-led care, which co-exist in a single, integrated precinct.

Location: Khayelitsha, Cape Town

Size: 520 m²

Photographer: Are Carlsen

The centre’s name, chosen by the community leaders, merges two locations: the Soweto settlement in Cape Town and Caracas, Venezuela where Urban Think Tank Group began. 'It was a very unexpected name, however this reiterates the need to take guidance from the community to effectively collaborate, and for the community to ultimately assume ownership of the development,' says Benjamin Kollenberg from UTTE.

The Ubuntu Empower Football Academy (185 m²), a partnership between Ubuntu Football and Urban Think Tank Empower, is a flagship initiative within the centre. Open to both boys and girls in Grades 3 to 6 (20 students per grade), the academy combines highperformance football training with a robust curriculum in numeracy, literacy, and life skills. The ambition is clear: develop well-rounded individuals capable of pursuing academic scholarships, professional careers, and local leadership roles.

Students are required to meet educational benchmarks to retain access to football training. This creates a culture where excellence in the classroom is valued equally to talent on the field. As one community member put it, ‘Kids are now trying to be the best at football and the cleverest, not the toughest or most feared.’

Serving as a social anchor, the academy draws activity and engagement into the centre throughout the day. It strengthens ‘community security’ through natural surveillance while reinforcing the importance of structured routines and purpose among the youth.

Adjacent to the academy is Nonzame’s Educare (40 m²), an early childhood development centre born from a grassroots initiative. Founded by Nonzame, a local resident and beneficiary of an Empower home, the crèche began inside her modest dwelling after she recognised the need for a safe, nurturing space for children of working parents.

The new facility expands that offering significantly, delivering a purpose-built classroom with access to shared amenities including toilets, a kitchen, and external play areas. Here, early learning is not an afterthought — it is foundational. Cognitive development, socialisation, and physical stimulation prepare children for primary school and beyond.

MEET THE TEAM

Architects: Urban Think Tank Empower, U-TT Group | Main Contractor: Bambana Management | Civil & Structural Engineers: DVH Consulting Engineers | Electrical Engineers: Laminin Construction | Solar Contractors: Allsolar | Fire Engineer: Sparq Consulting | Town Planners: Urban Dynamics Community Liaison: Ikhayalami | Landscape Architect: OKRA | Farm Implementation & Management: LUFN

“The centre was shaped through extensive consultation with the Soweto community and designed as a holistic ecosystem.”

Benjamin Kollenberg, Director and Architect @utt_empower

www.uttdesign.com

Architecture as infrastructure for empowerment

With the crèche and the football academy functioning symbiotically, children can graduate from Nonzame’s Educare directly into the Ubuntu program, both of which allow access to a kitchen (stocked with produce from the rooftop gardens), outdoor play areas, and community events infrastructure.

Both facilities were shaped through extensive consultation with the Soweto community and designed as a holistic ecosystem. The SowetoCaracas Community Centre includes a multipurpose hall, rooftop farm, coworking space, and formal infrastructure, offering a blueprint for integrated township development.

To further community upliftment, materials were sourced locally, and construction practices prioritised on-site training and employment, with over 50% of the labour force coming from within the community. Off-grid energy solutions (PV solar), passive ventilation, and water storage infrastructure reinforce the project's long-term sustainability.

With the Empower concept promoting housing as an ecosystem, the community centre is more than just a building; it forms part of a system offering social and educational support to the residents from the surrounding the development. The centre represents a shift in how affordable housing projects should be delivered — the Soweto-Caracas Community Centre’s strength lies in its relevance: rooted in daily life, in direct service of its people, and designed with them at every stage.

The Klaff Family Sports Complex Coordinates the Athlete’s Experience From Training to Recovery

Hubo Studio didn’t just build a sports centre — they created an entire sports campus composed of multiple structures.

The coffee shop, indoor and outdoor basketball courts, dance studio, fully equipped gym, and separate outdoor gym spaces come together to offer an unparalleled sports experience that is directly connected to King David High School (KDHL). Each component of the Klaff Family Sports Complex plays its own role while collectively forming a cohesive environment.

Location: Linksfield, Johannesburg

Size: 2 315 m2

One of the campus’s most ingenious features is its use of levels. The heaviest structural components are positioned at the lowest section of the site, which minimises any sense of obstruction from the street view. Instead, the building presents a thoughtfully scaled appearance with integrated branding in the plasterwork that proudly showcases KDHL.

On the lower levels, the team designed a four-storey sports arena with an ‘inside-outside’ concept in mind. The basketball court, which also accommodates futsal, netball, and volleyball, uses cross-laminated timber to create resilient and budget-conscious seating with substantial storage underneath. This space connects through a tunnel to the change rooms, allowing teams to transition seamlessly between team talks and matches. Excellent acoustics in

the change rooms foster team dynamics, while the state-of-the-art materials used throughout make a vibrant sports experience.

The gym connects directly to outdoor training spaces, allowing for activities such as race starts, scrums, and other exercises. Outdoor gym equipment, as well as amphitheatre-style seating, adds an extra dimension for athletes, making the entire space an active and engaging environment for effective training.

The entire campus breathes with shared courtyards and spaces that flow into one another. The gym housing cardio equipment features double-volume spaces with beautiful views of the playing field — allowing athletes to feel connected to the action while training.

There are two rehabilitation rooms, designed with flexibility in mind, that can easily adapt to the changing needs of physiotherapists and doctors, essential for students to receive cutting-edge treatment on-site. These rooms are complemented by ice baths for recovery, emphasising the building's holistic approach to sports — and supporting the cycle of warm up, train, rest.

Upstairs, a dedicated analysis room with ample storage is perfect for future technological integration. This room includes a screen for game reviews and team discussions, providing a designated area for in-depth analysis. The sports office shares this space, adding to its versatility.

The entire facility is designed to maximise flexibility and function while encouraging visibility and interaction. A café with a viewing deck offers a fantastic vantage point for watching rugby games or simply enjoying the surrounding activities. The building itself is punctuated by bold, vibrant colours, with the King David blue accentuating 1 400 square metres of plasterwork — crafted by a skilled local artisan. The vibrant exterior gives the structure a dynamic, energetic presence and a feeling of movement.

In essence, the sports campus is an extension of the school, offering a future-proof, versatile, and engaging environment for students to thrive both in sports and in their everyday lives.

“One of the campus’s most ingenious features is its use of levels.”

Asher Marcus, Founder @hubostudio www.hubostudio.com

Flooring: Floors International South Africa | Joinery: CEN Kitchens & Cabinetry | Lighting: Sarita Sharman Lighting | Paint: Plascon Timber Grandstands: Mass Timber Technologies | Steelwork: SM Structures | Acoustic Panels: Thula Wall Acoustic Panels | Tiles: NWT Tiles

Design is the fusion of form and function

Our Arabica carpet o ers plush comfort and lasting performance in nine co ee-inspired tones. Made with Stainproof Miracle Fibre, it pairs perfectly with vinyl oors in any space.