17 minute read

Bunny Mellon: Creating Gardens and a Library Legacy to Inspire and Educate

Bunny Mellon: Creating Gardens and a Library Legacy to Inspire and Educate I

Gardening is a way of life. As long as I remember I have never been without a plant or something growing. Seeds were a wonderment.

bunny mellon

Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon was a talented garden designer and horticulturist. She was also a lifelong bibliophile who assembled an extraordinary collection of rare books, manuscripts, and works of art. Her passion in both areas profoundly influenced many in the worlds of horticulture and the fine arts. She also thought deeply about both pursuits. Bunny would often say, “The quality of a garden does not depend on size. Gardens are personal reflections of the tastes, hopes, and desires of each garden maker.” 1

Bunny Mellon was born in New York City on August 9, 1910, at 777 Madison Avenue (today 45 East Sixty-Sixth Street) in a beautiful apartment building that was built only two years before her birth. A nurse who cared for her as a baby gave her the nickname “Bunny” and she was known by that name for the rest of her life. She was the eldest of the three children of Gerard Barnes Lambert (1886–1967) and Rachel Parkhill Lowe (1889–1978). On her father’s side, her family was prominent in business and she spent her early adolescent years at the family estate, Albemarle, in Princeton, New Jersey. Bunny attended the prestigious Miss Fine’s School (now Princeton Day School) with her brother, Gerard Barnes Lambert Jr. (1912–1947), and younger sister, Lily Lambert (1914–2006).

Bunny’s paternal grandfather, Jordan Wheat Lambert (1851–1889), attended Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, Virginia, where he studied chemistry and business. He established the successful Lambert Pharmacal Company in Saint Louis, Missouri, and in 1879, with the help of Dr. Joseph Joshua Lawrence (1836–1909), formulated a mouthwash with antiseptic properties called Listerine. The product was named after Sir Joseph Lister (1827–1912), the discoverer and promulgator of the practice of antiseptic surgery. Jordan left his flourishing company to his sons, Albert Bond Lambert (1875–1946), Jordan Wheat Lambert Jr. (1878–1917), Marion Liscome Jarvis Lambert (1881–1923), Gerard Barnes Lambert, and John David Wooster Lambert (1889–1976).

Upon graduation from Princeton University and Columbia University, Bunny’s father Gerard served in the First World War. After his military service, he went to work in the family company and became the driving force behind the advertising agency Lambert and Feasley, which was also located in Saint Louis, Missouri. Gerard promoted Listerine with great success as a cure for halitosis, and the Lambert family made a fortune from his canny style of advertising. Prior to the stock market crash of 1929, Lambert presciently sold most of his shares in the company. Subsequently he became president of the Gillette Safety Razor Company. His contributions included the development of the Gillette Blue Blade razor, which greatly increased the company’s profits.

Bunny’s father had many interests outside of his work. He was an erudite collector and amassed a large collection of fine art and books. Bunny described her father’s library at Albemarle: “There were books in Daddy’s library—big, huge books of gardens, of architecture, of archaeology… Everything fascinated me—and there was no one who talked to me about them so they were absorbed and made a great vault in my mind to think about.” 2

Gerard was also an accomplished yachtsman who owned and raced famous yachts, including the Atlantic, the Vanitie, and the Yankee.

Bunny Mellon leaning against a haystack, Oak Spring, ca. 1952. Photograph by Thomas Neil Darling, courtesy of Howard Allen Photography, LLC, Middleburg, VA.

100 Competing in the Kaiser’s Cup, a transatlantic yacht race from Sandy Hook, New Jersey, to the Lizard in southwest England, the Atlantic set a record for the fastest crossing under sail. It held for one hundred years, from 1905 to 2005. Gerard had acquired the Atlantic from Cornelius Vanderbilt iii (1873–1942) in the autumn of 1927. In addition, Gerard was a musician and a gifted writer. He wrote three books: All Out of Step (1956), Murder in Newport (1938), and Yankee in England (1937; reprinted in 1938).

The appreciation and importance of books influenced Gerard’s children. Many famous classics for young people by authors and illustrators such as Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel (1851–1913), Edmund Dulac (1882–1953), Kate Greenaway (1846–1901), Henriette Willebeek le Mair (1889–1966), and Arthur Rackham (1867–1939) could be found on the Lambert family’s bookshelves. Reading these tales, Bunny was inspired to learn about gardens and to create her own, beginning with a box of sand, glue, paint, and small twigs, before progressing to larger wooden boxes and seed trays. Bunny’s father encouraged this interest, and he set aside a space near the formal garden at Albemarle for her early horticultural undertakings.

Bunny’s maternal grandfather, Arthur Houghton Lowe (1853–1932), also helped instill a profound appreciation for plants and nature. Lowe was a successful businessman who established several textile mills in Massachusetts and Alabama. He introduced his young granddaughter to transcendentalism, and taught her to admire and respect nature, including through activities such as searching for wild mushrooms and other plants. He gave her a pocket-size book, Flower Guide: Wild Flowers East of the Rockies by Chester A. Reed (1876–1912), and Bunny memorized all of the plants by heart. Reed’s Flower Guide became her constant friend and traveling companion.

The positive influence and encouragement of her father and maternal grandfather, combined with her innate talent and artistic sensibilities, helped Bunny to establish her own sense of style. She began collecting books, growing plants in her room, and turning her designs into reality with vigor and confidence. Her first important rare book purchase was The Flower-Garden Display’d (1734) by Robert Furber (1674–1756), a British horticulturist who maintained a nursery near London. An early version of a nurseryman’s catalog, The Flower-Garden Display’d contains twelve magnificent colored engravings illustrating about four hundred different flowers, all grouped by the month in which they come into bloom.

Gerard Lambert wrote in his memoir, All Out of Step, about his daughter’s first gardening endeavors: “She designed and had built a small playhouse in the woods near our house in Princeton. She stood over the workmen every minute; directing them. It was of concrete blocks with a thatched roof of straw. It had a Dutch door that opened in two sections and was painted blue. There was a square walled garden in front with tiny boxwood bushes forming intricate patterns, and rare shrubs and vines. Inside, it was completely furnished. Everything there was in the scale of the house. From this first effort came many beautiful gardens, some done as professional jobs. She has this same talent in decorating and, like her father, she loves to do things over. Nothing is ever finished.” 3

As she planned and tended her new garden, twelve-year-old Bunny was able to watch the Olmsted Brothers of Boston, who were then refurbishing the grounds at the family estate. Of this period in her life, Bunny Mellon later remarked, “I feel I was born at the right time, this country was younger and people from all walks of life were working hard for a better future. There was a sense of pride and unity, and I had

my books, drawing pads, supplies, and gardening paraphernalia. This gave me a sense of stability which in turn helped me throughout my life.” 4

Bunny’s lifelong interest in rare books and manuscripts derived in part from her constant search for reference materials about plants and gardening. She took some of these books with her to Foxcroft Boarding School in Middleburg, Virginia, in the early 1920s. There she designed a small garden for Miss Charlotte Haxall Noland (1883–1969), the founder and president of the school. In any project in which she was engaged, Bunny found inspiration and guidance from her private library. “My beginning,” she would often say, “started with rare books on plants and garden plans, mostly French or Italian. They were like my bibles, a great need to satisfy my desires and queries that I had at the time. A library is built during a lifetime, it doesn’t happen overnight.”

Bunny began by designing gardens for her family. When she was eighteen, she helped her father to lay out the grounds and gardens of his new estate, Carter Hall, in Millwood, Virginia. One of Bunny’s first real commissions was to create a garden in New Jersey in 1933 for Hattie Carnegie (1886–1956), a well-known fashion designer based in New York City. During a visit to Hattie’s dress salon, the two ladies worked out an unusual arrangement—a garden in exchange for a haute couture dress and coat.

In 1932, Bunny married Stacy Barcroft Lloyd Jr. (1908–1994). He belonged to a prominent Philadelphia family, graduated from Princeton University, and had become a businessman and landowner in Clarke County, Virginia. The couple settled there and as a newlywed Bunny oversaw the construction of their new home, Apple Hill at Carter Hall, complete with a charming garden and greenhouse. In 1935, Bunny and Stacy purchased the Clarke Courier, a local newspaper based in Berryville, Virginia. Stacy was the editor and Bunny wrote the gardening column. Prior to their divorce in 1948, they had two children, Stacy Barcroft Lloyd iii (1936–2017) and Eliza Lloyd Moore (1942–2008).

On May 1, 1948, Bunny married Paul Mellon (1907–1999), the son of Andrew William Mellon (1855–1937), the wealthy Pittsburgh banker and industrialist. Paul was a widower, his first wife having died in 1946, and he had two children, Catherine (born in 1936) and Timothy (born in 1942).

Paul and Bunny shared a passion for art, and together they assembled one of the world’s paramount private collections. They surrounded themselves with beautiful works of art and donated many remarkable paintings and other objects to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond; and the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut. As a collector, Paul Mellon focused on English painting and sporting art, while Bunny’s taste inclined her toward French art, in particular impressionism and postimpressionism, due to her interest in gardening and botanical art. Bunny was also open to modern art and collected works by Diego Giacometti (1902–1985), Richard Diebenkorn (1922–1993), Mark Rothko (1903–1970), and others. With her appreciation for beauty in every form, she gravitated to and befriended creative designers such as the couturiers Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972) and Hubert de Givenchy (1927–2018); one of Tiffany’s most celebrated jewelers, Jean “Johnny” Schlumberger (1907–1987); and the inspired event planner Robert Isabell (1952–2009).

Paul and Bunny built a modest country home on Paul’s farm, Rokeby, for their combined families, known as Oak Spring. They led very private lives, spending time in their beautiful residences in Antigua,

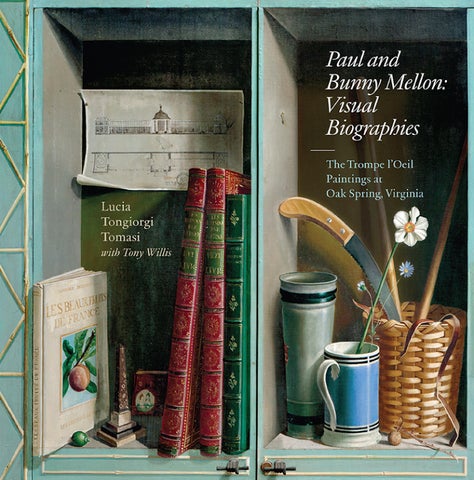

102 Massachusetts, New York, and Washington, DC. Rokeby, however, was considered “home.” Bunny planted beautiful gardens and created an English-style park. A building was erected to store the apples from the estate’s orchards and a dairy provided fresh milk, butter, and cheeses for the family. Eventually there were fourteen greenhouses on their estate. Bunny’s combined enthusiasm for art and gardening led her to have the entrance to one of the greenhouses decorated with trompe l’oeil paintings by the French artist Fernand Renard (1912–ca. 1980). Bunny Mellon won several prizes from the Horticultural Society of New York and at the New York International Flower Show for the varieties of cyclamens, gloxinias, and primulas that she cultivated in her greenhouses.

After Paul Mellon’s death in 1999, Bunny had two drying-out barns built on the estate in order to house logs from felled red and white oaks that she saved for future building projects. She was able to use the wood planks for another building constructed in 2010, called the Memory House. Now the Oak Spring Gallery, this multipurpose building is used for entertaining guests and introducing them to Bunny Mellon’s legacy. It also has rooms for archives, exhibition spaces, a digital lab, and work spaces for fellows, scholars, and artists.

While convalescing from a pulmonary illness, Bunny began to grow and sculpt woody perennials into miniature herb trees. She planted myrtle, thyme, rosemary, and santolina in clay pots, shaped or pruned them into artistic forms, and used them in her various homes as centerpieces. Others adopted her idea and now these same small herb topiaries can be found in many florists’ shops.

Bunny’s most famous projects were the redesigns of the Rose Garden and the East Garden of the White House in Washington, DC. In 1961, during a visit to her home at Cape Cod, Bunny was asked by President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) to redesign the Rose Garden on the west side of the White House, close to the Oval Office. The Rose Garden was first constructed in 1913 during the administration of Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924). After much encouragement and enthusiastic support from President Kennedy’s wife and Bunny’s dearest friend, Jackie (First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, 1929–1994), the Rose Garden was revitalized as a space of beauty and functionality. Today, the White House Rose Garden is familiar to millions around the world as the backdrop to important presidential ceremonies. Bunny Mellon also began designing the East Garden, but work was not completed until the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson (1908–1973). Lady Bird Johnson (1912–2007) then named it the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden in honor of the former president’s widow. Both gardens are used frequently for White House events.

In an article that appeared in Vogue in 1965, Bunny Mellon wrote, “Too much should not be explained about a garden. Its greatest reality is not reality, for a garden, hovering always in a state of becoming, sums its own past and its future. A garden, like a library, is a whole made up of separate interests and mysteries.” 5

After President Kennedy’s assassination, Jacqueline Kennedy asked Bunny if she could assist in the design of the president’s grave site in Arlington National Cemetery. In collaboration with the architect John Carl Warnecke (1919–2010) and the landscape architect Perry Hunt Wheeler (1913–1989), a very simple but dignified memorial was created. Bunny was instrumental in selecting not only the plants, which included dogwoods and magnolias, but also the West Falmouth granite that paves the grassy site and the millstone on which the eternal flame stands.

Later, Bunny would work with the famous architect I. M. Pei (1917–2019) on the design of the grounds surrounding the John F. Kennedy

Bunny Mellon in the formal greenhouse at Oak Spring, ca. 1961. Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Photograph by Toni Frisell.

104 Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. Of their collaboration, Pei remarked: “Mrs. Mellon has the combination of sensitivity and imagery with technical knowledge that you only find among the best professionals.” 6 She also collaborated with the landscape architect Dan Kiley (1912–2004) on the layout of the grounds surrounding the East and West Buildings of the National Gallery of Art.

During her lifetime, Bunny found joy and fulfillment in designing gardens for her family and personal friends. These included gardens for her daughter Eliza Lloyd Moore in Little Compton, Rhode Island; for “Johnny” Schlumberger’s town house in New York City; for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s summerhouse on Martha’s Vineyard; for the home of the museum director and university professor Charles Ryskamp (1928–2010) in Princeton, New Jersey; and for Château du Jonchet, Hubert de Givenchy’s splendid residence south of Paris. Every garden, whether large or small, was planned down to the last detail in order to create a place of natural beauty that was distinctive and uniquely suited to the person for whom it was designed. Bunny always made a point of looking for native species suitable for planting. Another feature that characterized all her gardens was the placement of beautifully pruned trees to create striking focal points. She would often say, “Give each garden its own atmosphere. Among the many things that make each garden unique, and perhaps the most important are the tastes, needs, and ability of the people involved.” 7

In the early 1970s, at a social function in Pittsburgh, Bunny Mellon was asked about her library. She answered that she didn’t have a library or a special place for her books, and they were unfortunately scattered and kept in many locations. On overhearing this conversation, Paul Mellon was determined to help Bunny rectify this situation. With his encouragement, in the spring of 1976 Bunny Mellon hired the New York City–based architect Edward Larrabee Barnes (1915–2004), and together they designed a beautiful yet functional building nestled in the pastoral setting of Oak Spring. The Oak Spring Garden Library was completed in the spring of 1981 and Bunny Mellon’s unique collection of books—mainly on horticulture, botany, and natural history—finally had a permanent home. Two decades later, the library expanded with the help of a local architect, Thomas Beach from Earth Design Associates, and the new wing was completed in the winter of 1997.

Today, the Oak Spring Garden Library is a thriving research center housing nineteen thousand objects—from manuscripts and books to drawings, prints, and sculpture—all of which are at the disposal of scholars engaged in research and other studies. The collection includes books on horticulture, landscape design, botany (including specialized books on trees, flowers, fruits, and fruit trees), natural history, voyages of exploration and travel accounts, architecture, the decorative arts, and classical literature. There are valuable manuscripts of all kinds, from books of hours and herbals to antique treatises with hand-colored engravings. Four descriptive catalogs of the library’s collections have been published: An Oak Spring Sylva (1989), An Oak Spring Pomona (1990), An Oak Spring Flora (1997), and An Oak Spring Herbaria (2009).

The library stands apart from the house. It comes into view from a gravel path overarched by an exquisitely tended arbor of Mary Potter crab apple trees that is underplanted with displays of seasonal perennials and annuals. The path leads to the display greenhouse with its magnificent trompe l’oeil mural. Bunny Mellon’s garden combines the features of a medieval walled garden with those of an English kitchen garden. Dwarf fruit tree cordons and espaliers intermingle with herbs, vegetables, and some of Bunny’s favorite flowers such as

The Old Wing, Oak Spring Garden Library, 2019, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

The New Wing, Oak Spring Garden Library, 2019, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Bunny Mellon’s gardening hats and jacket with pruning shears, 1982, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Photograph by Fred Conrad.

forget-me-nots, French poppies, sunflowers, and purple cornflowers. Every tree, plant, and flower, every piece of sculpture and every building, from the greenhouses to the toolsheds, is perfectly placed, creating magical vignettes wherever one wanders among the flower beds and landscaped grounds. Plantings are never allowed to grow very tall, so as to allow unhampered views of the beautiful Virginia countryside.

Bunny Mellon’s close friend Hubert de Givenchy wrote: “Bunny Mellon…is a perfectionist. Her gardens are enchanting and her houses refined…I have learned much from her, and I am infinitely grateful.” 8 This homage was sincere, for in the 1990s, Givenchy sought Mrs. Mellon’s advice on restoring Le Potager du Roi, the vegetable garden planted by Jean-Baptiste de La Quintinie (1626–1688) for Louis xiv at Versailles. During this four-year project, Mrs. Mellon’s personal library proved to be an invaluable resource. By studying her numerous editions of Instruction pour les jardins fruitiers et potagers by La Quintinie, Mrs. Mellon and Hubert de Givenchy were able to help restore the garden to its original glory. For her dedication and achievement, in 1995 Mrs. Mellon was awarded the medal Officier des Arts et des Lettres by the French government.

Together with her close friend Robert Isabell, Bunny designed a “Walled-In Espaliered Garden” for the 2002 Chicago Flower and Garden Show. Robert Isabell was a brilliantly creative designer and together he and Bunny built a miniature version of Oak Spring, complete with gardening sheds, a slate tile path, faux stone walls, live espaliered fruit trees, dwarf trees in pots, and flower beds filled with jonquils, daffodils, tulips, and pansies. This was one of Bunny’s last garden design projects.

Bunny Mellon passed away at Oak Spring in March 2014 during a quiet winter snowfall. With her passing, an era came to an end. Nevertheless, her remarkable achievements live on through the Oak Spring

Garden Foundation, which stewards the landscape and garden she created and the art collections she assembled. Her home and collections provide inspiration to students and scholars as they pursue their research. To quote her own words: “I am not an educated botanist, horticulturalist or landscape gardener. However, without formal training I have learned and enjoyed in a self-taught fashion all its pleasures and satisfaction. That is why for all of you who want to open this door it is there for the taking.” 9 notes

1. Rachel Mellon, personal journal, Oak Spring

Garden Library.

2. Rachel Mellon, personal journal, Oak Spring

Garden Library.

3. Gerald B. Lambert, All Out of Step: A Personal Chronicle (Garden City, NY, 1956), 130.

4. Rachel Mellon to Tony Willis, personal communication.

5. Rachel Mellon, “Green Flowers and Herb Trees,” Vogue, December 1965, 208–11.

6. Paula Deitz, Of Gardens: Selected Essays (Philadelphia, 2011), 29.

7. Rachel Mellon, personal journal, Oak Spring

Garden Library. 8. Françoise Mohrt, The Givenchy Style (Paris, 1998), 9.

9. Rachel Mellon, personal journal, Oak Spring

Garden Library.