10 minute read

The Revival of Trompe l’Oeil Painting in the United States and France, 1800 – 2000

The Revival of Trompe l’Oeil Painting in the United States and France, 1800–2000 I

The nineteenth century saw the rise of the movement known as realism (in reaction to the emotionalism of the Romantics) and the establishment of academies of fine arts in many cities across Europe. The popularity of the trompe l’oeil, however, continued unabated among the wealthy bourgeoisie and entrepreneurs, perhaps because of its accessibility in terms of subject matter and style. Nevertheless, art critics were beginning to question its nature and its validity as a form of artistic expression. Reflecting on the concept of imitation, John Ruskin (1819–1900) launched a stinging attack on the genre in his book Modern Painters. In his opinion, the trompe l’oeil artist was guilty of inveigling the viewer into admiring the skillful artifice of the painting and the technical prowess of the artist rather than seeking to present “the truth.” He observed, “The mind derives its pleasure, not from the contemplation of a truth, but from the discovery of the falsehood.”27 Meanwhile, in France at the beginning of the century, the neoclassical painter and art critic Philippe Chéry (1759–1838) dismissed this type of picture as a sleight of hand designed to exploit the credulity of the nouveaux riches.

From the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, the typology of the still life underwent a process of transformation and renewal, first at the hands of the impressionists and then by artists involved in subsequent avant-garde movements. In a rush to modernity, the trompe l’oeil was left behind; often considered to be an “optical trick” rather than “real art,” it was left to professional and amateur painters who engaged in respectable exercises in style, producing endless variations on a limited range of themes. One that was extremely popular with the public, for example, was the trompe l’oeil panel of wood to which were attached many different kinds of objects—from creased sheets of paper, handwritten letters, newspaper cuttings, printed notices, and engravings to cameos, paintbrushes, and other workaday objects—all depicted in realistic detail. Another form of the trompe l’oeil that experienced a revival in this period was the Renaissance practice of decorating walls and ceilings with illusionistic frescoes opening onto spacious landscapes or vast horizons.

While in Europe the once-popular trompe l’oeil was replaced by the revolutionary novelty of avant-garde movements, in the United States it would enjoy ever-increasing success as artists revitalized the genre and produced arresting illusionistic effects,28 reinterpreting the traditional Dutch still life in a wholly original manner. A family of artists—Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) and his sons and daughters—played a central role in this renewal,29 as may be seen in the many still lifes of Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825). One of his most original works was Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception (After the Bath); 30 perhaps recalling the story of Parrhasius, who managed to deceive his rival Zeuxis with his painting of a curtain, Peale’s canvas is almost completely taken up by an ample white towel modestly concealing Venus, who has just stepped out of her bath. Indeed, in the title to his work the artist alludes explicitly to his “deception,” using the expedient of the optical illusion conceived and realized with exceptional mastery.

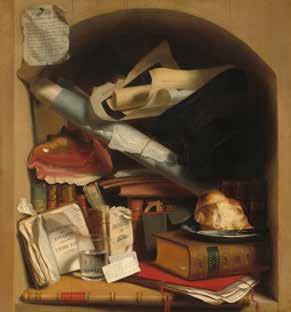

In Poor Artist’s Cupboard (ca. 1815), Charles Bird King (1785–1862) applied his skill as a still life painter to convey a moral message in a work of great emotional intensity.31 He himself earned a certain degree of success by dint of hard work and many sacrifices, but the objects arranged in the niche of this trompe l’oeil speak eloquently of the

Charles Bird King, Poor Artist’s Cupboard, detail, ca. 1815, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund and exchange).

Raphaelle Peale, Venus Rising from the Sea– A Deception (After the Bath), ca. 1822, oil on canvas, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 34-147. Photograph courtesy Nelson-Atkins Media Service/Jamison Miller.

Charles Bird King, Poor Artist’s Cupboard, (with detail), ca. 1815, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund and exchange). William Michael Harnett, After the Hunt, 1885, oil on canvas, The Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH, museum purchase 1954, 954-O-120.

22 economic and psychological toll that could be taken on less fortunate artists—from the two battered volumes propped up behind the glass of water, Advantages of Poverty and Pleasures of Hope, to the creased notice on the wall announcing the imminent sale of his remaining possessions.

During the second half of the century, William Michael Harnett (1848–1892) produced trompe l’oeil paintings that were striking for their mimetic realism and original subject matter. In the wake of the Civil War, his paintings evoked an economically stable and quietly “virile” world. His most celebrated work was After the Hunt, painted in 1885. Ignoring convention, Harnett did not send the picture to the prestigious Salon de Paris, but instead unveiled it at a public venue in Manhattan. What is more, in order to stimulate debate and generate publicity, he prepared a theatrical backdrop that further accentuated the illusion created by his work. After the Hunt attracted admiring crowds and a flurry of articles by art critics and journalists whose comments ranged from bemusement to lavish praise.32

During the closing years of the century, John Frederick Peto (1854–1907) returned to a more classical style, producing balanced compositions of objects arranged on a table or shelf, or papers, letters, and newspaper cuttings attached to a panel of wood, employing the stratagem of the rebus to puzzle and beguile his viewers. It would not appear to be a coincidence that the term contrefait (to imitate or faithfully copy), which had been used since the Renaissance, was revived and applied to the genre of the trompe l’oeil by art critics and the press in the United States.33

In 1938, the art dealer Julien Levy (1906–1981), promulgator of surrealism, abstract expressionism, and experiments with every form of the visual arts from photography to cinematography, mounted an exhibition in his New York City gallery entitled Old and New Trompe l’Oeil: Illusion, Double Image, Perspective. By juxtaposing works by past masters and contemporary artists, he set before the viewer the question of the intriguing relationship between trompe l’oeil painting and surrealism (one need only recall the disconcerting canvases of René Magritte [1898–1967] and Salvador Dalí [1904–1989]), which shared the objective of rendering real space illusionistically.34 Levy’s provocative hypothesis would be taken up by Jean Baudrillard, who noted in his book De la séduction the sense of “disquieting extraneousness” that the two forms of visual representation evoked.35

In 1949, an exhibition entitled Illusionism and Trompe l’Oeil opened to great éclat at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, showing works by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Giorgio De Chirico (1888–1978), and Dalí that further contributed to the revival of interest in this style of painting.36

The Mellons’ collection included some important still life / trompe l’oeil paintings by American artists, which they donated to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Among these are Raphaelle Peale’s beautifully composed Strawberries and Cream (1816) and Still Life with Apples, Sherry, and Tea Cake (1822), as well as several evocative trompe l’oeils by John Frederick Peto including Still Life with Cake, Lemon, Strawberries, and Glass (1890) and Still Life with Oranges and Goblet of Wine (1880–90s).

In France as well, a revival of interest in the trompe l’oeil was beginning in the nineteenth century. At the Salon de Paris held in 1800, a canvas by Louis Léopold Boilly (1761–1845) entitled Collection des dessins created something of a sensation.37 This work depicts a sheaf of sketches en trompe-l’oeil that appear to have been wedged into the picture’s frame, which is real, but whose trompe l’oeil glass appears to be broken in the lower right corner, a motif that was used by artists

John Frederick Peto, Still Life with Oranges and Goblet of Wine, 1880–90s, oil on artist’s board, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. Raphaelle Peale, Still Life with Apples, Sherry, and Tea Cake, 1822, oil on wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon. Henri Cadiou, La Déchirure (The Tear), 1981, oil on canvas. Photograph courtesy Joël Cadiou.

24 in the eighteenth century.38 The trompe l’oeil was so convincing that many visitors put out a finger in amazement to test the jagged edge of the pane. Another painting of white grapes demonstrates the artist’s skill as a still life painter.39

None of the French trompe l’oeil painters who followed Boilly during the nineteenth century, however, could match his technical skill or originality. Artists such as Albert Casaus, J. Maupin, and L. Touillon generally confined themselves to turning out competent works that simulated collages with the standard assemblage of letters, newspaper cuttings, engravings, maps, playing cards, and even banknotes.40

Then, in the twentieth century, the French painter Henri Cadiou (1906–1989) started a movement which he dubbed “Trompe l’Oeil / Réalité.” Its members, known as the trompe-l’oeillistes, promoted a new form of realism. Galvanized by the work of the surrealists, the trompe-l’oeillistes made use of illusionism to express a very modern aesthetic sensibility. One notable example is Cadiou’s trompe l’oeil La Déchirure (The Tear) (1981), in which a sheet of wrapping paper has been roughly torn to allow a coup d’oeil of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa beneath.41 In his Vestiaire d’usine, the humble belongings of a factory worker are displayed in a realistic still life composition.42 Various exhibitions of Cadiou’s work were held in Paris, beginning with Peintres de la Réalité at the Orangerie in 1934, and were followed by successful shows in Belgium, Luxembourg, and North America. Two other artists of note from the first half of the twentieth century are Pierre Gilou (b. 1938) and Jacques Poirier (1928–2002). The work of Poirier is of particular interest because of the complex cultural allusions that he wove into his compositions.43

It should also be noted that from the 1950s to the 1960s sculptors began to experiment with the creation of hyperrealistic figures using sophisticated techniques and materials such as resin, fiberglass, and silicone, of which the startlingly lifelike sculptures by Duane Hanson (1925–1996) were among the earliest. This prompted eminent scholars from the philologist and critic Erich Auerbach (1892–1957) to the art historian Charles Sterling (1901–1991), and the art theorist and perceptual psychologist Rudolf Arnheim (1904–2007), to reflect anew on the nature of perception in critical analyses that extended to the still life and the trompe l’oeil.44

notes

27. John Ruskin, Modern Painters (New York, 1856), 19–20.

28. Paul Staiti, “Con Artists: Harnett, Haberle, and Their American Accomplices,” in Ebert-

Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions, 91–102;

Mark Mitchell, “Veri maestri: Il trompe l’oeil in America,” in Giusti, Inganni ad arte, 99–108.

29. Nicolai Cikovsky, ed., Raphaelle Peale: Still Lifes (Washington, DC, 1988).

30. Ca. 1822, oil on canvas, The Nelson-Atkins

Museum of Art, Kansas City. On the theme of cloth in trompe l’oeil paintings, from canvas and bath towels to precious fabrics, cf. also

Henri Cadiou and Pierre Gilou, La peinture en trompe-l’oeil (Paris, 1989), 55–58.

31. Oil on wood, National Gallery of Art,

Washington, DC, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund and exchange).

32. Oil on canvas, The Butler Institute of

American Art, Youngstown, Ohio; see Alfred

Frankenstein, After the Hunt: William Harnett and Other American Still Life Painters, 1870–1900 (Berkeley, 1969).

33. Staiti, “Con Artists,” 92.

34. Old and New Trompe l’Oeil: Illusion, Double

Image, Perspective (New York, 1938). Mrs. Mellon was particularly struck by The Basket of Bread (1926, oil on wood panel), a trompe l’oeil painting by Salvador Dalí conserved in the

Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida. 35. Jean Baudrillard, De la séduction (Paris, 1988).

36. Illusionism and Trompe l’Oeil: An Idea Illustrated by an Exhibition, with essays by Alfred

Frankenstein, Jermayne MacAgy, and T. Carr

Hower (San Francisco, 1949).

37. Private collection, Paris.

38. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 140–42.

39. Raisins blancs, oil on canvas, Musée des Beaux-

Arts de Rouen.

40. Trompe l’oeil anciens et modernes (Paris, January 1985).

41. Oil on canvas. Cf. Giusti, Inganni ad arte, 116–17.

42. 1970, oil on wood. Cf. Giusti, Inganni ad arte, 153.

43. Cadiou and Gilou, La Peinture en trompe-l’oeil.

44. Erich Auerbach, Mimesis. Dargestellte

Wirklinchkeit in der abendländischen Literatur (Bern, 1946); Charles Sterling, La nature morte de l’antiquité à nos jours (Paris, 1952);

Rudolf Arnheim, Art and Visual Perception (Berkeley, 1954).