29 minute read

A Trompe l’Oeil for the Mellons’ Living Room by Martin Battersby

A Trompe l’Oeil for the Mellons’ Living Room by Martin Battersby I

From the end of the 1950s to the beginning of the 1960s, two trompe l’oeils were commissioned by the Mellons for their estate at Oak Spring—the first presumably for Paul and the second definitely for Bunny. Like the genre itself, whose subject matter often contains tantalizing enigmas and obscure references, various points in the stories of these two works remain unclear, even to one such as myself who had the rare privilege of spending considerable time studying the collections in the extraordinary library at Oak Spring and passing many congenial hours in the company of Bunny and her husband. Because the documentation relating to these two episodes is meager, it will be necessary to make a few assumptions and use a touch of imagination in order to retrace how they came into being.

There are a few dates that can serve as guideposts to the history of these commissions, which were completed within the space of about two years. One is a handwritten invoice from Martin Battersby dated April 26, 1958, and addressed to “Mrs. Paul Mellon” that reads “For painting on two panels for doors to television screen”; another is the fact that Fernand Renard signed and dated his work in the pavilion of the greenhouse “Renard 1959–1960.” Battersby’s note also specifies the amount due for “one painting…Tilly Losch…framed,” dedicated to Tilly Losch (1903–1975), an aristocrat born in Vienna who established a name for herself as a classical dancer, actress, and painter, but this work is no longer in the collection at Oak Spring.57

The fact that the invoice was addressed to Bunny suggests that the original idea to decorate the cabinet standing to the right of the entrance to the living room at Oak Spring may have come from her. This piece of furniture contained the family’s television, and one can well imagine the couple feeling that such a modern device hardly fit with the decor of their living room, where they passed many hours when in residence, either in quiet intimacy or in the company of friends and guests, and always for an aperitif before lunch or dinner, and coffee afterward. It may be supposed that the couple discussed how they might keep the television out of sight when it was not in use and finally decided to commission a work of art for this purpose. The idea of concealing the television behind a painting, and what is more a trompe l’oeil containing allusions to the couple’s many interests— particularly those of Paul—must have seemed a particularly apt solution.

As has already been noted, Paul was an Anglophile with a deep-rooted appreciation of English art, history, and culture, so it is not surprising that the couple’s choice for this commission should have fallen upon George Martin Battersby, an English painter who had already gained a considerable reputation for his eclectic talent, which he applied in areas ranging from the decorative arts to the trompe l’oeil. Both Battersby and his patrons were passionate collectors of art and objets d’art, and what is more, Bunny found in him a kindred spirit who shared her love of French culture and her interest in fashion, which drew her first to the work of the couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga (1895–1972) in the mid-1950s, and then to Hubert de Givenchy (1927–2018), who would become a close friend.

A painter with an interest in the theater, as well as a collector, art historian, and author, Battersby was noteworthy for his exquisite taste, creative energy, and readiness to experiment with new art forms.58 Born

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, detail of left lower shelf, ca. 1959, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

38 in London in 1914 to a father who was a jeweler, he left school at an early age in order to dedicate himself to the applied arts. He worked as a draftsman for Gill and Reigate of London, a leading firm of antique dealers and interior decorators who specialized in traditional styles. At the same time, he studied architecture at Regent Street Polytechnic, as he notes in his book The Decorative Twenties. This period was followed by a brief apprenticeship at Liberty—the exclusive London shop for fabrics and fine objects for the home—where he gained valuable experience and knowledge as an interior decorator.

Battersby became enamored of the theater after appearing before the footlights in 1933. He enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art the next year, where he studied set design and perfected his French. He made good use of both skills, gaining a reputation as a scenery designer and spending time in France studying the decorative arts. He created the sets for the Old Vic’s 1938 production of Hamlet with Laurence Olivier, and in 1945 designed the scenery for three other plays by William Shakespeare produced at Stratford-upon-Avon.

As his biographer Philippe Garner perceptively observed, “Battersby’s character was well suited to work in the theatre. He was fascinated by the arts of visual illusion, by masks and by the stylization and artifices of the stage. These passions, combined with his graphic skills…provided a basis for the development of another great talent, as a trompe l’oeil painter.”59

Always prepared to explore new forms of visual expression, in his mid-twenties the artist began to take an interest in wall frescoes, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century trompe l’oeil painting, fashion, and antiques after working for the flamboyant antique dealer David Edge. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, he began to assemble his own eclectic collection, which ranged from eighteenth-century trompe l’oeil paintings and French furniture to exquisite art nouveau objects, all of which he arranged with great flair in his London flat, first in Kensington and then in Mayfair.

During this period, Battersby not only collected trompe l’oeil paintings, but started producing his own. He exhibited a virtuosity that added to his growing reputation and led to a series of solo exhibitions, beginning at the Brook Street Gallery in London in 1948. Others followed and he was then invited to show his work in the United States, at the Sagittarius Gallery in New York in 1956 and in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1958. It was probably on one of these occasions that he made the acquaintance of Mr. and Mrs. Mellon and other American magnates such as Grace Fairfax-Carey, Nathaniel Hill, and Elinor Ingersoll. Nathaniel Hill was a stockbroker, while his wife Elinor Ingersoll was a director of the Campbell Soup Company and president of the Preservation Society of Newport County. Mrs. Ingersoll had an immense love of French culture, having lived and studied in Paris, and in 1958 she and her husband commissioned Battersby to decorate the dining room of their Newport home—“Bois Doré”—with eleven trompe l’oeil murals. They chose a theme of famous figures often associated with Versailles, from Madame de Pompadour to Louis xiv, Marie Antoinette, Voltaire, and Molière. 60 A reproduction of one of these mural paintings appears in Trompe l’Oeil: The Eye Deceived. 61

Battersby’s fame continued to spread during the 1960s. In 1964, an exhibition entitled Art Nouveau: The Collection of Martin Battersby was held at the art museum in Brighton, the city where he finally settled and to which he left a large legacy of artwork.62 In 1969, the artist himself curated an exhibition for the Brighton Art Gallery entitled The Jazz Age, An Entertainment, which was inaugurated by the great Franco-Russian artist and designer Erté (1892–1990).

In this seaside town, Battersby dedicated himself to writing a series of books, among them The World of Art Nouveau (1966), The Decorative Twenties (1969), The Decorative Thirties (1971), Art Deco Fashion, and Trompe l’Oeil: The Eye Deceived (1974). This last work, published by St. Martin’s Press in New York, was the most substantial and original of his contributions as an art historian (although it lacks a bibliography). In it, Battersby displays his profound knowledge of the subject, writing with authority on the history of the trompe l’oeil from the classical age to the present day. The genre, whose objective in his view was “primarily to puzzle and to mystify,”63 is analyzed in a series of chapters, each dedicated to a specific category: Flowers, Sculptures, Rooms, Niches and Cupboards, Papers and Prints, and so on. The volume is illustrated with numerous examples, some of which are well-known and others less so. He included a few of his own works, among them the panel dedicated to Molière that formed part of the already cited “Bois Doré” series commissioned by Mrs. Ingersoll.

Battersby’s trompe l’oeil at Oak Spring was never published, perhaps out of respect for Paul and Bunny’s wish for privacy. It does not appear that the artist remained in contact with his patrons after the completion of the two panels and the purchase of the painting dedicated to Tilly Losch, which will be discussed in the last section of this book.

A large exhibition dedicated to Martin Battersby’s oeuvre was held at the Ebury Gallery in London from February to March 1982, but the artist was too ill to attend the opening and he died in April of the same year.

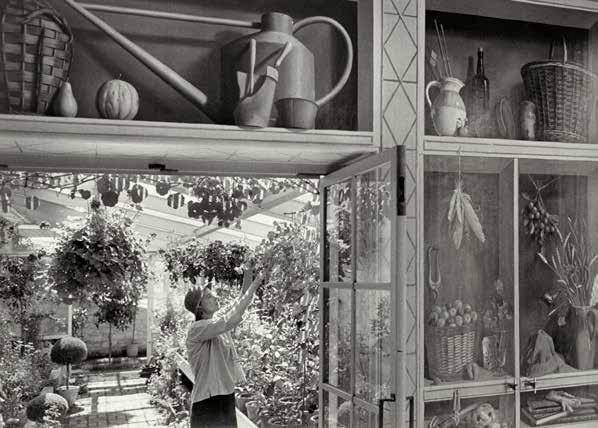

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil: The Eye Deceived (New York, 1974), frontispiece and title page. Martin Battersby with his maquette and mural panel for his “Sphinx” room at the Carlyle Hotel, Madison Avenue, New York, 1960. Photograph by Angus McBean, courtesy of Philippe Garner.

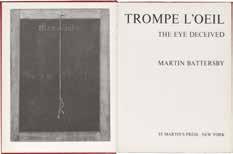

Georg Hainz, A Cabinet with Objects of Art, 1665–67, oil on canvas, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen. SMK Photograph/Jacob Schou-Hansen. Attributed to Domenico Remps, Scarabattolo (Cabinet of Curiosities), ca. 1690, oil on canvas, Museo Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence.

Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring

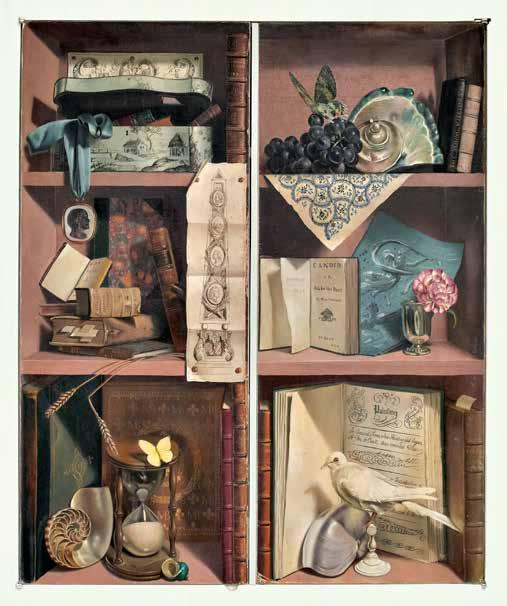

The trompe l’oeil by Martin Battersby was painted in diluted oils on canvas and attached to the two doors of a cupboard that held the family’s television. This cupboard was in turn concealed inside a cabinet designed by Bunny to harmonize with the closed bookshelves that ran along the length of one wall in the living room. Battersby completed the commission—it is not known whether in England or in loco—probably sometime from 1957 to April of the following year, when he submitted an invoice for 900 dollars.

In the composition of this work, the artist drew on his vast knowledge of trompe l’oeil painting, combining tradition with details suggested by his patrons, primarily—it may be conjectured—Paul. This was a practice congenial to the artist and satisfactory to his clients, as is reflected in the many commissions that he received.64

The two panels of the trompe l’oeil each depict three bookshelves whose insides are painted a dusky rose. The shelves are filled with an array of objects reproduced in their actual dimensions and illuminated by a cool, diffuse light (typical of the artist’s palette) falling from the right.

The layout of the composition can be traced back to the seventeenthcentury tradition of the gabinetti di curiosità, such as the already cited A Cabinet with Objects of Art by Georg Hainz (albeit with open shelves rather than a cupboard with doors) and the Scarabattolo attributed to Domenico Remps, both of which drew inspiration from the coeval Wunderkammern and Kunstkammern and are filled with finely crafted artifacts and rare natural history specimens.

In the congeries of objects depicted by Battersby, books predominate and this was no accident. Paul and Bunny were both avid bibliophiles and extremely well-read. Here there was a felicitous conjunction between their personal interests and the conventions of the genre because books, as shown above, constituted a recurrent theme in the still life and the trompe l’oeil since their inception. The twentieth-century English artist employed this traditional motif and yet, following many conversations with his patrons, found himself painting not merely a trompe l’oeil but—it will be suggested—a conceptual portrait of Paul as well.

On the shelves, a number of handsomely bound volumes are depicted, many with their titles stamped in gold on their spines. These books range from some of the great classics of Western literature to recently published works of a more popular, often satirical nature (Paul was well-known for his coruscating wit), the latter—somewhat incongruously—presented in equally fine leather bindings. The books were most certainly chosen by the Mellons themselves and one can imagine that the process gave the couple many an hour of shared pleasure during the period in which the trompe l’oeil was being composed. It is reasonable to assume that the volumes depicted in Battersby’s painting could be found in Paul’s library and served as models for the artist, although they have since been dispersed.

The Books in Battersby’s Trompe l’Oeil

On the top left bookshelf is an elegant wooden box dating to the eighteenth century, painted a pale blue-gray and decorated with watercolor sketches of country landscapes. The box contains four books with fine leather bindings, but no indications as to their titles or authors. To the right stands a more imposing volume whose beautiful binding

has a worn, antique air that belies its contents. Stamped in gold on the spine between raised bands and gold decoration are the words “Cardinal / Pirelli / Firbank,” evidently a reference to the last novel by the idiosyncratic English author Ronald Firbank (1886–1926)—Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli—which was published in 1926 (with a much more modest cover). Ronald Firbank studied at Cambridge University (as later would Paul), and in this, his last novel, recounts with biting satire the “eccentricities” of an imaginary cardinal who, among his many antics, baptizes a dog in his cathedral and dies of a heart attack while chasing—in a state of complete undress—a choirboy around the church aisles. Like many of Firbank’s works, it exposes the vacuity of modern society, where superficial, foolish, and corrupt individuals seem to flourish.

On the middle shelf on the left side, leaning against the back wall, is a tall volume with a leather and marbled-paper cover. In front of it are other books arranged in a pile. At the bottom of the stack is a slender volume bound in leather with some indistinct decoration or writing in gold. On this rests a large tome bound in vellum with its top edge facing the viewer and four clearly visible slips of paper serving as bookmarks. The third book in the pile is a smaller, but equally thick volume bound in white leather whose spine, traversed by five raised bands, carries the words written in brownish-red ink, “Ariosto / Orlando Furioso / Venetia 1630.” This is a copy of the epic poem by the sixteenth-century Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533), published in an exceptional edition with commentary and illustrations in Venice in 1630 by Niccolò Misserini. Next to it lies a fourth book that cannot be identified as its spine is not visible. Resting on this is an English edition of the masterpiece War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910); it is opened to its title page, although the author’s name and the publisher’s imprint are hidden by the book in front of it. It is also surprisingly slender, suggesting that this edition may have consisted of more than one volume.

Leaning at an angle against these volumes is a book, elegantly bound in leather with raised bands, gold decoration, and the words “Trompe / l’oeil / by / Martin / Battersby” stamped on its spine. Here the artist has followed a widespread practice among trompe l’oeil artists and wittily camouflaged his signature in the painting.

The back wall of the lowest shelf is almost completely taken up by a large volume bound in brown leather and decorated with an alternating pattern of fleurs-de-lis and the monogram “MB,” once again denoting Battersby’s signature. Three other volumes with fine bindings and decoration occupy the shelf, but none of them carries a title or the author’s name on its spine.

On the top right-hand shelf are two small volumes: the first bears the title “The Young Visitors” [sic ] on its spine, while on the second appear the words “Ovid” and below “Venetia / 1632.”

The Young Visiters, or, Mr Salteena’s Plan is a Victorian novella penned by the English writer Daisy Ashford (1881–1972) when she was just nine years of age. Rediscovered by Ashford many years later, it underwent a complicated gestation involving numerous revisions before finally being published in London in 1919, more or less in its original form complete with spelling mistakes, with an introduction by J. M. Barrie (1860–1937), the author of Peter Pan, or, The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up. Ashford’s novella provides an ingenuous, but inadvertently critical

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, ca. 1959, cupboard with two doors, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, detail of right middle shelf, ca. 1959, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

“child’s-eye view” of the class system in England, recounting the futile efforts of Alfred Salteena, “an elderly man of 42,” to become a gentleman. The book was an immediate success, in part because many readers believed that it was actually a brilliant hoax written by J. M. Barrie himself. Its authenticity was, however, confirmed and this interesting piece of juvenilia has come to be regarded as a minor masterpiece of serious satire that confronts the obstacles to social mobility. The story was adapted for the stage in 1920, enjoying successful runs in both London and New York.

The original binding of the first edition of The Young Visiters was a simple affair, and a copy perhaps lay in the living room, where it would have been read and discussed with appreciative laughter by the couple. That the books in the trompe l’oeil bookcase should have included not only Ovid and Ariosto, but the aesthete Firbank’s Cardinal Pirelli and a “society novella” by a child shows that the couple’s approach to reading was open-minded, cultured, and not at all elitist or pedantic.

The second volume depicted is probably Ovid’s Metamorphosis: Englished, mithologiz’d, and represented in figures, a translation by George Sandys (1578–1644) of the famous poem by the Roman poet Ovid (43 bce–17/18 ce). It is known that Paul possessed a copy of this rare edition that, contrary to what is written on the spine of the trompe l’oeil volume, was printed not in Venice but in Oxford by John Lichfield in 1632. In fact, no editions of the Metamorphoses were published in Venice in 1632 and in any case it is likely that Paul would have preferred to have an English translation of this great work of Latin literature.

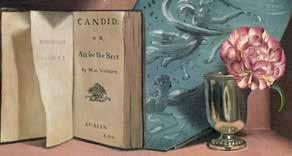

On the middle shelf is just one volume—an English edition of Candide, the captivating philosophical novella by Voltaire (1694–1778) to which the Mellons must have felt a particular affinity, having asked the artist to feature it prominently in the composition. A thread of intelligent and biting irony runs through the story of Candide, a naive hero whose unlikely adventures unfold in the mid-eighteenth century in settings ranging from Germany, Holland, and Spain to South America and Turkey, yet contain reflections on society and politics that remain pertinent today. The author presents a disenchanted vision of human nature, exposing its hypocrisy and the “léthargie de l’ennui,” but also offers much food for thought and wise suggestions on how to live a positive life.

Candide was an extraordinary success across Europe when it appeared in 1759; an English translation—Candid: Or, All for the Best—was published in London by the printer and bookseller John Nourse in the same year. The volume depicted here is a rare English edition printed in Dublin in the same year by James Hoey Jr. and William Smith Jr. that bears the same title as the English translation by John Nourse, which Battersby has faithfully copied in his trompe l’oeil.

The moral of Voltaire’s tale, as encapsulated by Candide in the closing scene—“Il faut cultiver notre jardin”—was not at all to turn one’s back on the world and think only of oneself. It is rather an invitation to act in a positive manner, in accordance with one’s abilities and the opportunities that offer themselves. This philosophy must have appealed greatly to both of the Mellons, and it can be imagined that Bunny found the celebrated metaphor of the garden especially meaningful, for she dedicated her life to the cultivation not only of her own garden, but also the vaster garden of knowledge and culture.

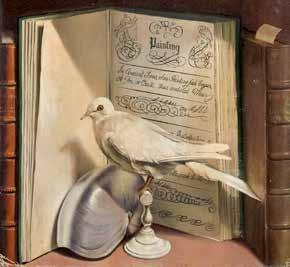

The bottom shelf on the right is largely taken up by a manuscript, Rays of Genius, collected to enlighten the rising generation (London, 1806), by the celebrated English calligrapher Thomas Tomkins (1743–1816). It is propped open to the first page of a section on the history of painting.

Although this page is partially hidden behind a pearly nautilus shell and a stuffed dove, one can admire the fine calligraphy and decorative flourishes of the author and read, “In Ancient Times, when Painting first began. A Pen, or Chalk, thus imitated Man…Distribution of…Musick to the Ears.” Tomkins kept a writing school in London, and was a friend of the poet, writer, and lexicographer Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) and of various artists, including Joshua Reynolds (1732–1792), who painted an amiable portrait of him. Among his other achievements, Tomkins designed the title page and dedication page for Robert John Thornton’s (1768–1837) magnificent flower book The Temple of Flora. Bunny acquired several copies of this florilegium, which, with its thirty-one folio-size color plates executed by various artists using techniques from engraving to mezzotint, may be considered one of the most outstanding volumes in the Oak Spring Garden Library. 65 To the left of Tomkins’s Rays of Genius stands a tall, slender, leather-bound book bearing the words “Vathek” and “Horace Walpole” on its spine; this was evidently an edition consisting of two novels—Vathek, an Arabian Tale by William Beckford (1760–1844) and The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole (1717–1797)—both of which were veritable best sellers in their time. 66

Vathek is an erotic fantasy set in the Orient and modeled on the works of Voltaire and the Marquis de Sade (1740–1814). Originally written in French, it was translated and published in English in 1787. The author, William Beckford, was a London-born novelist, traveler, art critic, and collector who inherited a fortune on the death of his father. This allowed him to amass a noteworthy collection of books and works of art and to build the (now lost) Gothic Revival country house Fonthill Abbey. His novel Vathek served as an inspiration to many other writers, including the poet Lord Byron (1788–1824). Scholarly

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, detail of right lower shelf, ca. 1959, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

46 interest in the work was revived by the Bulgarian literary theorist Tzvetan Todorov, and an elegant edition of Vathek was published in Italian by Franco Maria Ricci in 1978 as part of its series La Biblioteca di Babele, edited by Jorge Luis Borges.

The second work in the trompe l’oeil volume is The Castle of Otranto, a novel by Horace Walpole published in 1764 in London. Its formula, which combines medievalism, horror, and romance, was so successful that it gave rise to a new literary genre—the Gothic novel—and indeed the second edition of The Castle of Otranto bore the subtitle “A Gothic Story.” This form of literature spread across Europe from the end of the eighteenth century to the early nineteenth century and remains popular to this day. The author, who was the son of the British statesman Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745), studied at King’s College, Cambridge, and came into a peerage as the 4th Earl of Orford. He became an expert on the arts and antiquities, compiling what was perhaps the first comprehensive biographical history of the arts in England, Anecdotes of Painting in England. Walpole’s literary reputation rests on his remarkable novel and on his vast correspondence, which has been assembled and published in a scholarly edition of forty-eight volumes by Yale University Press.

Fantastical and brilliantly written, Vathek and The Castle of Otranto both left their mark on English culture between the Enlightenment and the pre-Romantic period, and Paul must have found them greatly to his taste. Perhaps he also felt a certain affinity with their authors— wealthy, well-connected, and among the most cultivated literary men of their age.

The third book on this shelf, which has a bookmark of white cardboard between its pages, carries on its spine the words “Poems” and “Donne.” This is a volume devoted to the poetry of John Donne (1572–1631)—poet, essayist, Church of England cleric, and one of the leading thinkers of the post-Elizabethan age. Donne experienced at first hand the difficulties of this period of transition and the religious tensions between the Catholic Church and the Church of England. He drew inspiration for his poems and ideas for his essays from sources ranging from medieval tradition to the scientific revolution and, following a fresh evaluation beginning in the nineteenth century, there has been a revival of interest in his work.

It is not surprising that Paul should have asked Battersby to include in his composition a volume dedicated to John Donne. One need only think of the celebrated line from Meditation xvii in Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, “No man is an Iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a piece of the Continent, a part of the maine,” which Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) used as the epigraph to his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) and which chimed so well with Paul’s strong sense of ethics and his generosity as a philanthropist. Among the books in his final donation to the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, was a copy of Donne’s Complete Poetry and Selected Prose published in London in 1929, with a binding quite similar to that in Battersby’s trompe l’oeil, and which may have served as a model for the artist.

Other Objects in Battersby’s Trompe l’Oeil

Intermingled with the books on the trompe l’oeil bookshelves is a fascinating collection of objects. While the volumes depicted were almost certainly chosen by Paul, the artist was in all likelihood invited to suggest other elements for his composition. Thus there are

subjects linked to the traditional iconography of the still life and the trompe l’oeil, which were no doubt identified after ample discussion and brought together to convey moral messages that are not difficult to decipher, even if they are couched in metaphorical language.

On the top right-hand shelf of the bookcase, resting on an ivorycolored napkin decorated with a paisley and floral motif in blue, is a cluster of purple grapes, perhaps a reference to the famous contest between Zeuxis and Parrhasius and the importance of painting pictures that are a faithful reflection of reality. An exotic moth (probably Chrysiridia rhipheus) is posed on one of the berries. Insects constituted a regular feature in still life, floral, and vanitas paintings and were invested with many meanings, among them the notion of the beauty but also the transience of human existence. Next to the moth, the artist has depicted, quite deliberately it may be presumed, the shell of a large green turban sea snail (Turbo marmoratus). Seashells often featured alongside other natural history specimens in the cabinets of collectors in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In addition, they were a favorite subject for artists, who were attracted by the variety, harmony, and elegance of their forms. With their uncompromising materiality, they served as symbols of knowledge and immortality.

Two shells also appear on the lowest shelf to the left—a young green turban snail and the cross section of a Nautilus pompilius revealing the beautiful spiral of its chambers. Once again, the artist contrasts the permanence and solid materiality of these objects with the ephemeral existence of an insect—a small yellow butterfly (perhaps a cloudless sulphur from the Pieridae family), the quintessential symbol of change and metamorphosis, which has alighted on an hourglass, another symbol of the passage of time. Also on the lowest shelf, and to the right, Tomkins’s book is propped open by a second pearly Nautilus pompilius. 67

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, detail of right upper shelf, ca. 1959, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, detail of left middle shelf, ca. 1959, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

48

A variety of other objects populate this scene. Tucked into the elegant box on the top left-hand shelf (which has already been mentioned and, it may be guessed, belonged to Bunny) is a gleaming blue satin ribbon from which hangs a modern cameo framed in gold and bearing the image of an African woman wearing an earring. Cameos and other artifacts have always been much sought after by collectors, appearing in the paintings of curio cabinets such as those of Hainz and Remps.

In keeping with the tradition of the trompe l’oeil, Battersby inserted into his composition objects that belong to the category of “Papers and Prints,” as he referred to them in his book on the history of the genre—letters, postcards, printed matter, and even, given his interest in collecting, “paintings [or drawings or engravings] within a painting.” Thus, behind the box on the top left shelf, attached with brass thumbtacks to the back wall, is a sheet containing sketches of scrolls. Fixed to the edges of the second shelf on the left by thumbtacks is an engraving on an oblong sheet that, judging from its creases, had originally been folded accordion-style; it depicts an obelisk on a pedestal embellished with four heads shown in profile and framed by leafy branches. The Egyptian obelisk, together with the sphinx, fascinated the English artist and he incorporated them more than once in his trompe l’oeil compositions, which were often inspired by the ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean.68

Propped casually against the back wall behind the volume of Candide is a black, gray, and white wash drawing on blue paper of a winged female figure with flowing drapery.

A touch of elegance is provided—perhaps on the suggestion of Bunny—by a footed silver cup holding a beautiful white carnation streaked with magenta. Both she and her husband were particularly fond of this flower and she had a large collection of them in her garden at Oak Spring. It is pertinent to note that in the history of painting and the “language of flowers,” the carnation has often been used as a symbol of love and as such was depicted in portraits from the Golden Age of Dutch painting.69

Perhaps the most poignant message in this painting is its appeal for peace. Held in place by the pile of books culminating in the copy of War and Peace are two stalks of wheat, the symbol of prosperity since the time of the ancient Romans.70 One is bent at an angle so that it points directly at the hourglass, which is counterpoised by the white dove standing on a wooden perch on the opposite shelf.71 The message is clear—wisdom and inspiration should be drawn from the great minds of the past and peace, well-being, and tolerance around the world must be defended.

What is quite striking about the trompe l’oeil by Battersby is the contrast it presents between the apparent immediacy of the moment captured—with books left open by their owner, loose drawings tacked to the shelves, butterflies about to take wing—and the quality of perfect stillness that imbues the picture, with each object seemingly frozen in time as the sands of the hourglass slowly run out.

Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil in the Living Room at Oak Spring, detail of left upper shelf, ca. 1959, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

notes

57. Oak Spring Garden Foundation archives.

The present whereabouts of this painting are unknown.

58. Philippe Garner, “Martin Battersby: A

Biography,” in The Decorative Twenties, by

Martin Battersby (London, 1988).

59. Garner, “Martin Battersby,” 9.

60. Cf. “Sleight of eye: in seven houses,” Vogue,

February 15, 1960, 138.

61. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 18.

62. John Morely, “Martin Battersby,” Journal of Decorative Society 1890–1940, no. 7 (1983): 5–8.

63. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 19.

64. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 18, 64.

65. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 354–58;

Nicholas Barker, Treasures of the British Library (London, 2005), 95.

66. This volume is probably Vathek / by William

Beckford. The Castle of Otranto / by Horace

Walpole / The Bravo of Venice….by M. G. Lewis, published in London by Bentley in 1836.

67. Seashells were often depicted by artists in still lifes and trompe l’oeils. Among the many examples, see Georg Hainz, A Cabinet with

Objects, ca. 1666, oil on wood, Hamburger

Kunsthalle, Hamburg; Filippo Napoletano,

Due conchiglie, 1619, oil on canvas, Villa di

Poggio a Caiano, Florence; Balthasar van der Ast, Still Life with Shells, ca. 1640, oil on panel, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam; and Adriaen Coorte, Cinq coquillages sur une tranche de pierre and Six coquillages sur une tranche de pierre (two pendant paintings), 1696, oil on paper on wood, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

68. Mural decoration for Lady Kenmare, Villa La

Fiorentina, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, in Garner,

“Martin Battersby,” 15.

69. Among the many examples, cf. Joos van

Cleve, L’Empereur Maximilien tenant un oeillet, 1510, oil on panel, Musée Jacquemart-André,

Paris; Hans Memling, Portrait of a Man with

Carnation, 1475, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin;

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Saskia with a Red Carnation, 1641, oil on oak, Staatliche

Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

70. Stalks of wheat appear in vanitas paintings by

Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts conserved in the collections of the Musée des beaux arts de

Rennes and the Statens Museum for Kunst,

Copenhagen.

71. It recalls Pablo Picasso’s famous La Colombe (1949), emblem of the World Congress of

Peace Partisans held in Paris in 1949.