20 minute read

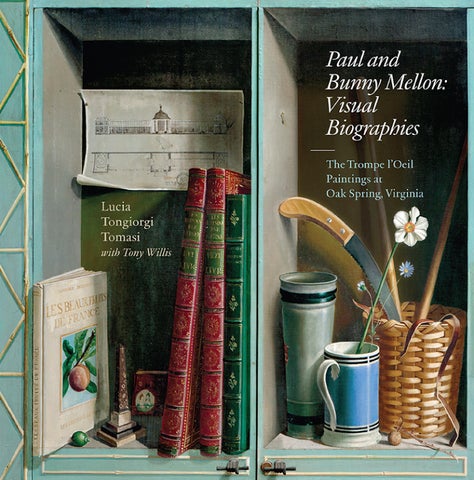

Other Trompe l’Oeils at Oak Spring

Other Trompe l’Oeils at Oak Spring I

Many trompe l’oeil paintings in different styles and of varying historical importance and artistic quality were acquired by the Mellons for their collections, particularly from the 1950s onward. While some works have since been dispersed, others still form part of the unique legacy that Paul and Bunny left behind. Among these are further paintings by Martin Battersby and Fernand Renard.

In the invoice sent in April 1958 to Bunny, Battersby included, as mentioned above, the amount due for “one painting…Tilly Losch… framed.” This work is no longer at Oak Spring, but a reproduction in a 1960 issue of Vogue gives us an idea of what it must have looked like.111 A well-known personage in the beau monde on both sides of the Atlantic, Tilly Losch was the stage name of the actress, ballet dancer, choreographer, and painter Ottilie Ethel Leopoldine, who led a tempestuous life that included marriage for a period to Henry Herbert, 6th Earl of Carnarvon (1898–1987). Born in 1903 in Vienna to an aristocratic family, she spent the greater part of her life in the United States, where she appeared in various notable stage, ballet, and film productions during the 1940s and 1950s before dedicating herself with some success to painting. She died in New York in 1975.

Martin Battersby composed a trompe l’oeil painting in Tilly Losch’s honor consisting of reproductions of photographs, portraits of the actress, and playbills of her performances attached with trompe l’oeil drawing pins and strips of wood to a panel. A butterfly is poised at the top of the painting, a symbol of this beautiful and captivating woman. It seems that the Mellons knew her, for in 1979 when the English literary agent Billy Hamilton was working on a biography of Mrs. Losch, he wrote to inform Bunny that the actress and artist had kept a diary in which “your name frequently appears, especially during the Sixties” and to ask for confirmation that there were “two of Tilli’s pictures in your husband’s collection in Washington.”112 A body color painting by the British artist, designer, and illustrator Reginald John “Rex” Whistler (1905–1944)—presently hanging in the Oak Spring Garden Library—portrays Tilly Losch dressed as Joséphine de Beauharnais for a performance of Streamline—The Private Life of Napoleon Bonaparte at the Palace Theatre in London on September 24, 1934.113

In addition to the greenhouse trompe l’oeil, various small paintings by Fernand Renard are in the collection at Oak Spring. In the archives are some cards with messages and charming sketches in tempera that were sent by the artist to Bunny from 1960 to 1978.114

Toward the end of the year 1960, by which time the decoration of the greenhouse had been completed, Fernand Renard sent Bunny a small still life painting in which various objects depicted in the greenhouse trompe l’oeil reappear. Three baskets sit on a table, one of which is filled with eggs and some stalks of wheat, and from another the handle of an implement protrudes, while strands of raffia dangle from a third basket placed somewhat in the background. Also on the table are a solitary egg, a small piece of fruit, a ball of string, and the pyramid-shaped glass bottle from the greenhouse trompe l’oeil, this time containing a few blue flowers. A creased sheet of paper bears the handwritten words “Bonne Année 1960,” while Renard’s signature is inscribed on the edge of the table. This work was undoubtedly sent by the artist as a gesture of esteem, but it has no direct connection to the commission on which he was working. 115

Jacob van Hulsdonck, Still Life of Plums, Cherries, Strawberries and a Rose, detail, early to mid-seventeenth century, oil on copper, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

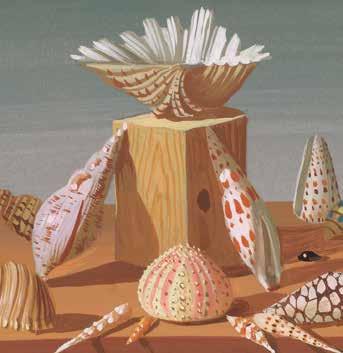

Christmas cards by Fernand Renard to Paul and Bunny Mellon, Shells on a table and White hyacinth in a blue and white pot, body color drawings, Gerard B. Lambert Foundation.

There is another small body color painting by Renard (not dated) that portrays Bunny’s daughter, Eliza Lloyd Moore, as an aspiring young artist, viewed from behind as she sits at her easel, palette and paintbrushes in hand. On the back of the painting are the words “Meilleurs voeux pour Nöel et la nouvelle année, chère Bunny, et affectueux souvenirs. F. Renard.” 116

A trompe l’oeil of notable quality by the same painter, which had been given as a gift by Bunny to one of her employees, has recently been rediscovered. It is signed in the lower right-hand corner and testifies to the artist’s technical mastery of the genre. Standing out against a dark background is a large open-weave basket and a terra-cotta pot that contains two plant stakes. Lying haphazardly on a table, as if they had just been brought in from the garden and deposited there, are four artichokes, a hazelnut, and the bract of an artichoke. In the background, the artist has added a loaf of bread and a glass of wine—two elements drawn from the traditional repertoire of Christian symbols. The loaf, which seems so real it could have just been taken out of the oven, and the fleshy leaves of the artichokes are reminiscent of the subject matter and style of the Spanish still life painter Luis Meléndez (1716–1780), whose works Renard could have seen in museums in the United States, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. 117

The trompe l’oeil was not of course limited to the works of consummate artists—paintings that have found their way into museums or wall decorations commissioned by wealthy and cultivated clients. There is a rustic stool conserved in the Oak Spring Garden Library whose seat has been decorated en trompe-l’oeil with an envelope from which a light blue card has been half drawn out. Attached to the card is a sheet of white paper with a penciled sketch of a leaping rabbit. Bunny may have been attached to this modest piece of decorative work, having loved books and illustrations featuring bunnies, such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter (1866–1943), ever since she was a child due to the nickname she had received from her nurse.

Still hanging today in the living room at Oak Spring are two small, beautifully framed oil paintings on wood of playing cards: Ace of Hearts Pierced by a Pink Carnation and Ace of Clubs Pierced by a White Tulip. Four quite similar trompe l’oeil paintings of a red rose with an ace of spades, a white and pink ranunculus with an ace of diamonds, a pink carnation with an ace of hearts, and a yellow tulip with an ace of clubs were sold at auction by Sotheby’s. 118 All six works bear the signature—“Dabos”—of the French artist Laurent Dabos (1761–1835) in the lower left corner. Dabos was born in Toulouse and studied at the local Académie des beaux arts. He became a successful portrait painter during the Napoleonic era and was even awarded the Légion d’honneur. But with the Bourbon Restoration, social conditions changed, his former clientele melted away, and he switched to the painting of genre scenes and trompe l’oeils. The works acquired by the Mellons in 1955 probably date to this period in his career. 119

Three unpretentious works on the theme of the “letter rack,” all of which appear to be by the same hand, were sold at auction by Sotheby’s. One painting is signed with the monogram of the artist George Oakes (1927–2017) and carries the date 1958 on its back. Each depicts a variety of papers (letters, cards, notices such as a playbill from the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden, etc.) and other small items (a feather, a key, pencils, a small notebook, a magnifying glass, a pair of spectacles) en trompe-l’oeil, with real strips of fabric extending across the width of the painting, apparently holding them in place. 120

On display in the family villa on the Caribbean island of Antigua were two imposing trompe l’oeil paintings entitled Fruits exotiques, 121

Laurent Dabos, Ace of Hearts Pierced by a Pink Carnation, not dated, oil on panel, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Laurent Dabos, Ace of Clubs Pierced by a White Tulip, not dated, oil on panel, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. which had almost certainly been acquired by Bunny and whose layout and subject matter recall the trompe l’oeil decoration of her greenhouse at Oak Spring. These were sold together with the property in 2016, but can be identified in photographs. The two paintings are very similar and indeed may have been conceived as pendant works. They previously belonged to a French collector (indicated by the initial “H.” on the back); both are dated 1746 and signed by Edme-Jean-Baptiste Douet (active 1745–73). 122

In the first painting, a large number of exotic fruits are arranged on the shelves of a display case—bananas, grapefruits, mangoes, avocados, cashews, cacao fruits, and so forth, some of which have been cut open to display their internal structure, while leaves and twigs seem to jut out of the picture. The inflorescence of a pineapple surrounded by its long lanceolate bracts dominates the composition; a hole has been drilled in the shelf to hold the stem. Another pineapple that has been cut in half sits on the shelf below. Two trompe l’oeil cartouches at the base of the painting provide a list of the fruits depicted.

The second painting presents a more chaotic display, with cascades of bananas and other exotic fruits spilling off the shelves. Once again, a single item holds center stage in the composition—a Heliconia sp. with its showy inflorescence—and a hole has been made in the shelf for the plant’s stem. In the lower right-hand corner is a cartouche with a list of the names of the fruits and plants represented.

In the cartouche on the left in the first painting is inscribed: “Fruits des Indes occidentales peints sur les lieux, d’après nature, pour le Cabinet de Sa Majesté le Roy de Pologne, Electeur de Saxe,123 par le siuer Douet, Peintre élève de l’Academie Royale de Peinture de Paris 1746.” This statement makes it clear that the artist himself undertook the hazardous voyage to the American tropics to study its flora, and

Edme-Jean-Baptiste Douet, Still Life of Exotic Fruits, 1746, oil on canvas (two paintings), private collection.

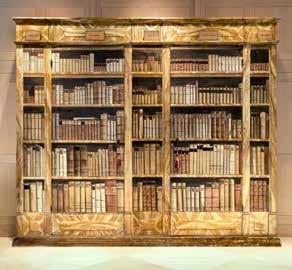

Italian cabinet in trompe l’oeil with marbled shelves and books, a nineteenthcentury scenery prop, oil on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

that these two works were painted in situ. Possibly influenced by the great flower painter Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer (1636–1699), who was also a professor at the Académie royale de peinture,124 Douet moved to Lyon in 1745 to work as a designer of floral patterns for the city’s textile ateliers. Two of his paintings were accepted for display at the 1773 Salon, one of animals and another of flowers, while the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon has a painting of a vase of tulips by Douet in its permanent collection.

Bunny must have admired the way in which Douet managed to exercise his talent and originality in these works while conforming to the canons of botanical painting, documenting the exotic flora of the American Tropics with scientific accuracy and at the same time reveling in their varied forms, unexpected colors, and marked tactile qualities. It is known that she was interested in tropical plants, above all fruit plants, and kept a garden on the island of Antigua in which various unusual species were cultivated.

Many objects other than paintings that nonetheless pertain to this pictorial genre are also conserved at Oak Spring. Most of them bear a connection with the world of books, a theme that runs through the collections of Paul and Bunny, as well as through the entire history of the trompe l’oeil.

On the first floor of the library annex is a magnificent eighteenthcentury bookcase of Italian manufacture that has been completely decorated en trompe-l’oeil, down to the veining of the wood. It is divided into five sections with a trompe l’oeil collection of books painted on panels behind which the real bookshelves lie. Each section is devoted to a different type of literature, as one can read on the plaques above each set of shelves: Ascetici, Istorici, Poeti, Miscellanea, and Proibiti. The volumes are arranged by size and by the style of their bindings,

and some of the spines bear labels that are still legible—for example, Il vitto pitagorico…discorso di Antonio Cocchi and Newtonismo per le Dame di Francesco Algarotti. Among the “prohibited” books is a volume of poetry by the abbot Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni of Genoa (1692–1768), whose works were banned not only because of their licentious content, but also because Frugoni was involved with the Freemasons. This piece of furniture, which originally belonged to the Lambert family and stood in Paul and Bunny’s home in Washington, DC, clearly harks back to the optical illusion of Libreria by the Bolognese artist Giuseppe Maria Crespi, cited above. Its trompe l’oeil fits admirably with the decor of the Oak Spring Garden Library, whose walls are lined with real shelves containing real books.

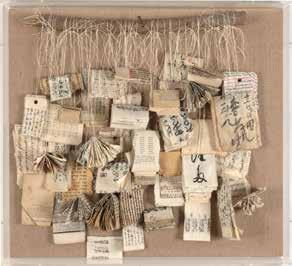

Bookmark by the American artist Jan Baker (1950–2018), given to Bunny by her daughter Eliza, is a modern work whose inspiration lies in the tradition of the trompe l’oeil and the world of the bibliophile. After earning a degree in printmaking and aesthetic studies from the University of California at Santa Cruz, Baker joined the faculty of the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design, where she taught courses on the book arts, letterpress, papermaking, bookbinding, and visual poetry in the Graphic Design department. She was also nominated as an Andrew W. Mellon Fellow of the RISD Museum in the Costume and Textile department. An indefatigable and endlessly curious traveler, she explored the arts in countries as far-flung as India, Vietnam, and Qatar. In Italy, she was captivated by the work of the great typographer and printer Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813) of Parma. Bookmark, which was created in 1995, reflects Baker’s multidisciplinary approach to her art. She collected innumerable scraps of paper with brief phrases or passages of text either printed or written by hand in various languages using different scripts, both Eastern and Western, and bound them

Jan Baker, Bookmark, 1995, various multi-folio texts hanging by strings from a stick, mounted on burlap, with a large nail in the middle, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Piero Fornasetti, Trompe l’oeil trumeau (secretary), ca. 1955–70, architectural lithographs printed onto wood fiberboard and mounted to laminate and solid wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Piero Fornasetti, Trompe l’oeil trumeau (secretary), detail ca. 1955–70, architectural lithographs printed onto wood fiberboard and mounted to laminate and solid wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

up in small, bulky packets tied with intricately knotted strings, which she then hung in a riotous jumble from a branch of wood.

With her intimate knowledge of the creative experience connected with the contiguous worlds of paper and the book, the trompe l’oeils of artists past and present who drew on similar devices to create their optical illusions would not have escaped Jan Baker’s attentive eye. She must have been familiar with Documents on the Wall (1656) by Cornelis Brizé (ca. 1622–ca. 1670)125 and Trompe l’Oeil Panel with Shipping Documents (1764) by the little-known Dutch artist Jacobus Plasschaert (d. 1765), in which official documents and an almanac hang from a wooden panel.126 A more recent work evokes her own, in two dimensions rather than three—Robert Sielle’s Files (1967) by the English artist Eliot Hodgkin, who has already been mentioned above. In this somewhat tongue-incheek but unsettling picture, the entire canvas is taken up by a large, unwieldy bundle of papers that Hodgkin depicts with startling realism hanging from a wall by a piece of twine. Battersby found this to be such a striking work that he reproduced it in his book on the trompe l’oeil.127

A unique artifact of great psychological as well as visual impact is a rare “piece” that only recently entered the collections of the Oak Spring Garden Library, left as a legacy to Bunny by the event planner Robert Isabell (1952–2009). In great demand among those moving in the rarefied circles of New York’s high society, Isabell organized parties, weddings, and openings, as well as more solemn events such as the ceremony in 1994 for the funeral of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. He was a brilliantly creative artist, and Bunny was perhaps one of his closest friends during the last decade of his life.

This trompe l’oeil trumeau (secretary) of wood, glass, and metal varnish is decorated with reproductions of woodcuts ingeniously arranged to create a series of optical illusions. The upper part consists of a cupboard with a niche and the lower part of two drawers, with a drop front in the middle section. The first version was designed and realized in 1951 by Gio Ponti (1891–1979) in collaboration with Piero Fornasetti (1913–1988). Gio Ponti was a Milanese architect, designer, and essayist who deserves much of the credit for reviving Italian design after the war. In the original prototype, which Ponti called “Architettura” and which may be seen today in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the upper portion of the cabinet featured concave modulations in the otherwise rigorously linear design of the piece. Fornasetti subsequently produced variations on the original with a flat top, different niches, the addition of a third drawer, glass shelving, and so forth. In 1953, forty of these cabinets were produced and then, after a long pause, another ten examples in 1980, one of which was acquired by Robert Isabell.

Piero Fornasetti, like Gio Ponti, was born in Milan and was a genuinely protean artist—painter, sculptor, interior decorator, printer of lithographs and fine art books, designer of theater sets and costumes, and the creator of literally thousands of objects. With his tireless energy and his interest in all that was new in the arts, he organized many international exhibitions. Irrepressible even in his youth, he was expelled from the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera for defiance of authority and completed his studies at the Scuola Superiore di Arti Applicate all’Industria. Fornasetti met Gio Ponti in 1940 at the vii Triennale di Milano and from this chance encounter a long and rewarding collaboration was born.

In 1942, Fornasetti received a commission to paint a series of frescoes for the Palazzo Bo, the seat of the Università di Padova. The next year, however, after completing this project, he went into exile. He spent the remainder of the war in Switzerland, where he ran a

86 small printing works producing lithograph posters, and also organized cultural events. Fornasetti returned to Italy in 1946 and began a successful career as an artist and designer. Among his most significant commissions was the furnishing and decoration of the transatlantic ocean liner Andrea Doria, which unfortunately sank in 1956.

After Ponti died in 1979, Fornasetti moved to London and opened Tema e Variazioni, a shop promoting Italian design that earned him international fame. With his scintillating imagination, he produced prints, furniture, and a great variety of decorative objects that were veined with sly humor but nevertheless rooted in the classical tradition of the visual arts, from the frescoes of Pompeii to those of Giotto and Piero della Francesca, from the architects of the Renaissance to the nineteenth-century avant-garde.

Ponti and Fornasetti’s trumeau was a striking and wholly modern expression of the optical illusions to be found in the works of past artists and architects. They conceived the novel idea of covering every inch of the cabinet with woodcuts designed by Fornasetti based on illustrations from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century treatises on architecture and on actual historical buildings such as the Palazzo Alessi in Genoa and the Palazzo Marino in Milan. With their refined sense of aesthetics and maniacal attention to detail, they designed the cabinet so that in whatever combination its various parts were opened or shut, a different and intriguing perspective would be presented to the viewer—of arcades, staircases, receding lines of sculpted columns, and concave and convex surfaces—deliberately creating visual confusion and posing the half-ironic question as to what purpose this piece of furniture was actually intended to serve.

A cabinet very similar to the one at Oak Spring was displayed in the exhibition Art and Illusions: Masterpieces of Trompe-l’oeil from Antiquity

Joseph Decker, Grapes, ca. 1890/95, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

to the Present Day at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence in 2009, while other exemplars have recently been sold at international auctions. 128

In another important exhibition on the trompe l’oeil—Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting (2002–3, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC)—the first section, which was significantly entitled “The Grapes of Zeuxis,” included a simple but evocative trompe l’oeil painting of two clusters of purple grapes hanging from a vine. Grapes, together with its pendant Green Plums, was painted circa 1885 by the American artist Joseph Decker (1853–1924). It was acquired by the Mellons in 1984–86 and donated to the National Gallery of Art in 1994, just part of the generous legacy that the couple left to the museum founded by Paul’s father, Andrew W. Mellon (1855–1937). 129

It is fitting that this presentation of the trompe l’oeil paintings commissioned or acquired by Paul and Bunny, which began with an account of the contest in antiquity between Zeuxis and Parrhasius, should conclude with a picture of grapes, a subject that appears in the works of so many of the artists who over the centuries dedicated themselves to this genre. The trompe l’oeil, with its combination of realism and symbolism, technical virtuosity and erudition, by turns charming, witty, and profound, managed to enchant and draw into its intriguing web two of the most refined and cultivated art collectors of the twentieth century.

notes

111. “Sleight of eye,” Vogue, 140.

112. Oak Spring Garden Foundation archives.

113. This sketch by Whistler forms part of a group of pencil drawings and watercolors of costumes and sets for the production of

Streamline conserved in the collections of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation.

114. The cards from Renard with small trompe l’oeil paintings are dated 1964, 1976, and 1978.

Two other cards with sketches in body color, one of a vase containing crocuses and the other of a squash and a sprig of parsley in a glass, are not dated.

115. The painting’s dimensions are 3 13/16 by 5 3/8 inches.

116. The painting’s dimensions are 5 3/8 by 3 1/4 inches.

117. Gretchen Hirschauer and Catherine A.

Metzger, eds., Luis Meléndez: Master of the

Spanish Still Life (Washington, DC, 2009).

118. Sotheby’s Auction, 3:sessions 3–5, lot number 1245.

119. Oak Spring Garden Foundation archives.

120. Sotheby’s Auction, 3:sessions 3–5, lot numbers 1376–78.

121. Each painting measures 4 feet 5 inches by 7 feet 6 inches.

122. Faré and Faré, La vie silencieuse en France, 352–53.

123. Stanisław II August Poniatowski (1732–1798). 124. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 175–77.

125. This work is conserved in the City Hall of Amsterdam. Cf. Gerhard Langemeyer and

Hans-Albert Peters, eds., Stilleben in Europa (Münster, 1979), 228.

126. Giusti, Inganni ad arte, 26.

127. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 97. Cf. also Eliot

Hodgkin, 35.

128. Giusti, Inganni ad arte, 156; Rossana Bossaglia,

“Fornasetti: Between Art Deco and Neo-Deco,”

Apollo 336, no. 131 (February 1990): 92–95;

Patrick Mauriès, Fornasetti: Designer of Dreams (London, 1991); Mariuccia Casadio, Fornasetti.

L’artista alchimista. La bottega fantastica (Milan, 2009), 357; Mariuccia Casadio, Barnaba

Fornasetti, and Andrea Banzi, “Furnishing:

Fantasies and Furniture between Reality and

Illusion,” in Fornasetti: The Complete Universe (Milan, 2010), 345–49.

129. Cf. the catalog entry by Franklin Kelly in

Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions, 120–21.