12 minute read

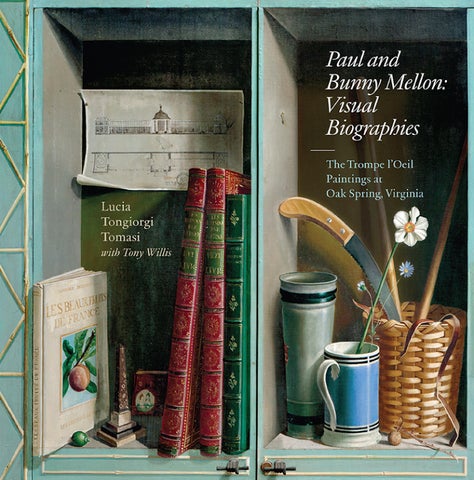

“Counterfeit”: The Trompe l’Oeil and Botanical Art

“Counterfeit”: The Trompe l’Oeil and Botanical Art I

As already noted, the verb “to counterfeit” denotes the production of a replica or copy of an object that is so realistic it could be mistaken for the object itself. Deployed in treatises on the visual arts since the Renaissance, the word was used in different European languages to refer to the realistic portrayal of natural history specimens. Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), in whose writings the term can be found, produced many such counterfeits, demonstrating their ability to imitate “fragments” of the natural world dal vivo so perfectly that the viewer was taken in by the illusionistic effect. The subject portrayed had an almost palpable “presence” that caused the viewer to forget the hand of the artist.45

Thus, the accentuated realism and mimetic precision that had characterized still lifes and trompe l’oeils since their origins were also central to the Renaissance practice of representing the world of nature, particularly subjects such as plants and animals, as is also demonstrated by the floral still life. As early as the second half of the sixteenth century, the first treatises on botany and zoology printed in Europe were also accompanied by illustrations based on drawings dal vivo. This ushered in a completely new pictorial typology, that of the scientific illustration. Such works not only made a fundamental contribution to the birth of modern science, but assumed an important place in the panorama of the visual arts in the early modern age.46

Like the trompe l’oeil, this new genre was based on the art of “showing” (ostensio in Latin) in a clear and tangible manner, referring in particular to the practice of observation and experimentation, two pillars of the scientific revolution. The specimen was first studied and then portrayed with the greatest possible exactitude. In the following centuries, artists gifted with a “scientific eye” produced paintings on subjects from the natural world that bear numerous analogies to the trompe l’oeil, and Bunny Mellon acquired many such examples for her collection at the Oak Spring Garden Library.

One of the finest practitioners of this form of painting to emerge during the Renaissance was Jacopo Ligozzi (1547–1627); his portrayals in body color (or tempera) 47 of plants and animals from the collections of the Medici family (today conserved in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence) are meticulously accurate but are also suffused with a vivid immediacy. Other outstanding naturalistic painters followed, from Nicolas Robert (1614–1685), peintre en miniature to Louis xiv, to the intrepid naturalist and scientific illustrator Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717). In the nineteenth century, Pierre Joseph Redouté (1759–1840) would earn an international reputation as “the Raphael of flowers” for his exquisite paintings, which are still greatly admired today. 48

In the accurate portrayal of natural specimens, as in the trompe l’oeil, greater understanding of the physical phenomenon of vision played a crucial role. With the invention of the microscope a hitherto invisible world was revealed, from the reproductive parts of the flower to the anatomy of the insect. During the course of the seventeenth century, further important advances in the field of optics were made by scientists such as Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton, whose discoveries markedly influenced the visual arts. 49

In fact, optical devices would play an increasing role in the work of artists. Accustomed to using the microscope as a visual aid in their

Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, Still Life of Variegated Tulips, Roses, a Hyacinth, a Primrose, a Violet, Forget-me-nots, a Columbine, Lily-of-the-valley, a Cyclamen, a Marigold and a Carnation, all in a glass vase, with a Butterfly and a Housefly, detail, 1606, oil on copper, private collection (previously in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon).

Attributed to Simon Bening, Madonna and child and Latin text (with detail) with borders of flowers and insects, body color on vellum, from Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis ad Usum Romanum (Bruges, 1524), folio 103v and 104r Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

work, in the eighteenth century artists began to experiment more often with the possibilities offered by the camera obscura, which used a series of lenses to produce images that were almost photographic in their detail and clarity. The challenge faced by both the scientific illustrator and the trompe l’oeil painter was the same—how to capture their subject matter faithfully and in minute detail—even if in the first case the subject was “live” and “natural” and the artist was seeking to mirror or mimic nature, while in the second case the subject was “inanimate” and “artificial” and the artist’s objective was to recreate the apparent reality of a mise-en-scène.

Many works, however, belong contemporaneously to both genres— the naturalistic illustration and the trompe l’oeil—attracting and enchanting the viewer with a realism that is at once scientific and poetic, and that can be admired by turning the pages of the precious manuscripts and contemplating the paintings hanging on the walls of the Oak Spring Garden Library. Among the many outstanding works are several books of hours, of which one in particular stands out. It is attributable to the Flemish artist Simon Bening (ca. 1483–1561), a gifted miniaturist trained in the Bruges-Ghent School. His work contains superb miniatures of religious scenes and margins decorated with trompe l’oeil images of plants and flowers, drawn from the repertoire of Christian symbology—the rose, violet, columbine, strawberry, daisy, carnation, and lily—together with small birds and insects. Although charged with symbolic meaning, these flowers and animals are depicted in such a realistic style that they could have been plucked from a monastery garden and carefully set down on the page. 50

Among the noteworthy botanical paintings in the Oak Spring Garden Library collection are two large canvases by the Tuscan artist Gerolamo Pini (fl. ca. 1614–15), which represent replicas by the artist’s hand of two of the three paintings conserved in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. These five paintings are the only known works by the artist to have come down to us. One portrays forty-three exotic flowering plants, mostly bulbous species, surrounding an imposing Iris susiana. In the other, seventy-one different species are arranged around a large Fritillaria imperialis. All of the plants are depicted with great fidelity, in most cases with their bulb, while their brightly colored flowers stand out against the dark brown background of the canvas. In the lower left corner of each painting is a partially unrolled trompe l’oeil scroll that is held in place by two trompe l’oeil pins. On each are listed the names of the plants depicted in the painting, followed by the signature of the artist and, in the painting featuring the iris, the date 1614. In addition, to heighten the impression of verisimilitude, the Tuscan artist has added a humorous detail familiar to us from the tradition of trompe l’oeil painting—a tiny fly that has alighted on the cartouche in the painting with the fritillary, almost inviting the viewer to swat it. 51

Also of great note in Bunny’s collection is a series of seventeen small trompe l’oeil paintings executed in oil on copper plates by the Flemish artist Jan van Kessel the Elder (1626–1679), which depict plants, flowers, fruit, and insects against a light gray background. In one of the paintings, the artist’s name, written in letters formed from worms and insects, appears together with the date 1658. Van Kessel belonged to the Brueghel dynasty and was well-known in his day for his keenly observed, small-scale paintings on vellum or copper, the latter often used to decorate cabinets and other pieces of furniture. The series in the Oak Spring collection constitutes a harmonious whole that was almost certainly intended to provide a frame of naturalistic motifs around a larger panel. The artist’s technique complemented his

Gerolamo Pini, Flowers with an iris in the center (with detail), 1614, oil on canvas, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Gerolamo Pini, Flowers with a fritillary in the center (with detail), ca. 1614, oil on canvas, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Jan van Kessel the Elder, Study of plants and insects (with detail), 1653–58, oil on copper, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

interest in the natural world, for the sprigs of delicate flowers, plump little cocoons, colorful butterflies, and tiny insects (including a fly) are painted with painstaking realism, helped by the use of a magnifying glass and perhaps also a microscope. 52

We must also note a truly unusual manuscript that was much admired by Bunny: Recueil de Plantes by Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin (1721–1786), which consists of more than 250 drawings and paintings in pen and ink, wash, red chalk, watercolor, and body color, mostly of plants but also some animals (with a scientific description provided in the lower part of each sheet), produced by the artist over a period of almost fifty years. This collection reflects Saint-Aubin’s exploration of a wide range of styles, techniques, and compositional formulas. Included are a number of original experiments with the technique of the trompe l’oeil. Many plants seem to have been freshly gathered and laid on the page, while others have been depicted alongside trompe l’oeil drawings or engravings, such as the flowering branch of honeysuckle (Lonicera caprifolium) that protrudes from a partially rolled-up engraving in a device recalling the famous Les misères de la guerre (f. 8) by Jacques Callot (1592–1635).53 A sprig of jasmine (Jasminum officinale) has been wrapped in a watercolor depicting a palazzo with a garden (f. 2), while a yellow giroflée or wallflower (Erysimum cheiri) 54 lies on a sheet of music dedicated to an unknown “Mademoiselle de P.” (f. 46). Another painting shows the shells of two marine gastropod sea snails (Scalaria epitonium) resting on a leaf of sea kale (Crambe maritima); the author dates the sheet to 1757 and adds that the shells came from India, where they were much prized for their rarity.

Alongside numerous splendid botanical drawings by the artists Nicolas Robert, Maria Sibylla Merian, and Pierre Joseph Redouté are various botanical paintings which Bunny appreciated not only for

Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin, Honeysuckle with flowers and a scroll with thieves fleeing an inn, watercolor and body color, from Receuil de Plantes Copiées d’ apres Nature par de Saint-Aubin, Dessinateur du Roy Louis xv (1736–85), folio 8, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, Still Life of Variegated Tulips, Roses, a Hyacinth, a Primrose, a Violet, Forgetme-nots, a Columbine, Lily-of-the-valley, a Cyclamen, a Marigold and a Carnation, all in a glass vase, with a Butterfly and a Housefly, 1606, oil on copper, private collection (previously in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon).

Daniel Seghers, Flowers in a glass vase, not dated, oil on copper, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Jacob van Hulsdonck, Still Life of Plums, Cherries, Strawberries, and a Rose, early to mid-seventeenth century, oil on copper, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

their fidelity to nature but also for their trompe l’oeil effects. One of these is Still Life of Variegated Tulips, Roses, a Hyacinth, a Primrose, a Violet, Forget-me-nots, a Columbine, Lily-of-the-valley, a Cyclamen, a Marigold and a Carnation, all in a glass vase, with a Butterfly and a Housefly by Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573–1621), which presents a veritable microcosm of the natural world, including a fly that has settled for a brief moment on the table.55 Other examples worth mentioning are the Still Life with Flowers sitting on a crumbling stone shelf by Johannes Baptiste Fornenburgh (1595–1648/49), Still Life of Plums, Cherries, Strawberries, and a Rose (early to mid-seventeenth century) by Jacob van Hulsdonck (1582–1647), and two paintings on copper by the Dutch Jesuit artist Daniel Seghers (1590–1661), in which elegant bouquets are arranged in glass vases that throw off iridescent reflections.56 Against this rich background, it is not surprising that Paul and Bunny should choose trompe l’oeil—not once, but twice—to decorate their beloved home.

notes

45. Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, “Immagine naturalistica: Tecnica e invenzione,” in

Natura-Cultura. L’interpretazione del mondo fisico nei testi e nelle immagini, ed. Giuseppe Olmi,

Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, and Attilio Zanca (Florence, 2000), 137–38.

46. Giuseppe Olmi, “Natura morta e illustrazione scientifica,” in La Natura morta in Italia, ed.

Federico Zeri and Francesco Porzio (Milan, 1989), 1:69–91; Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann,

The Master of Nature: Aspects of Art, Science, and

Humanism in the Renaissance (Princeton, NJ, 1993).

47. Body color refers to the water-based medium (thicker than watercolor but not as dense as oils) used by artists up until the modern age.

Tempera often contained “secret” ingredients added by the artists, which are not always easy to identify.

48. Susan Fraser, Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, and

Tony Willis, eds., Redouté to Warhol: Bunny

Mellon’s Botanical Art (New York, 2016).

49. Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi and Alessandro Tosi, eds., Il cannocchiale e il pennello. Nuova scienza e nuova arte nell’età di Galileo (Florence, 2009).

50. Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora:

Flower Illustration from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Time: A Selection of Rare Books,

Manuscripts, and Works of Art in the Collection of

Rachel Lambert Mellon (Upperville, VA, 1997);

Fraser, Tongiorgi Tomasi, and Willis, Redouté to Warhol. 51. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 63–66;

Fraser, Tongiorgi Tomasi, and Willis, Redouté to Warhol, 48–49; André Chastel, Musca depicta (Milan, 1984); Giotto’s Fly and the Observation of Nature, in Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and

Illusions, 163–79.

52. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 104–6;

Fraser, Tongiorgi Tomasi, and Willis, Redouté to Warhol, 56–59; Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions, 178–79.

53. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 239–45;

Fraser, Tongiorgi Tomasi, and Willis, Redouté to Warhol, 17.

54. Saint-Aubin mistakenly identified this plant as “Leucoyum luteum.”

55. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 95–98.

This work, along with many other paintings and objects from Mrs. Mellon’s collection, was sold at auction in 2014; Sotheby’s Auction:

Property from the Collection of Mrs. Paul Mellon, 21–24 November 2014 (New York, 2014), 1:196–201.

56. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 98–99, 100–103.