16 minute read

Trompe l’Oeil Painting: Vision, Perception, Deception

Trompe l’Oeil Painting: Vision, Perception, Deception I

Reflecting on the relationship between “reality” and “irreality,” and on the illusionism that distinguishes trompe l’oeil painting, the French philosopher and sociologist Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007) wrote in 1977:

trompe-l’oeil is such a highly ritualized form precisely because it is not derived from painting but from metaphysics; as ritual, certain features become utterly characteristic: the vertical field, the absence of a horizon and of any kind of horizontality (utterly different from the still life), a certain oblique light that is unreal (that light and none other), the absence of depth, a certain type of object (it would be possible to establish a rigorous list of them), a certain type of material, and of course the “realist” hallucination that gave it its name[…]As a strict formal “genre,” as an extremely conventional and metaphysical exercise, as anagram and anamorphosis, it is opposed to painting as the anagram is opposed to literature. The most strikingly distinctive characteristic is the exclusive presence of banal objects.1

There are many possible readings of the trompe l’oeil, which the Italian intellectual Pietro Accolti (1579–1642) aptly described nearly four centuries ago as “a deception of the eyes.”2 It gained acceptance as a style of European painting from the end of the sixteenth to the beginning of the seventeenth century, at the same time as the still life, attracting talented artists who produced highly original works, as many continue to do to the present day.

The problems posed by the ambiguous relationship between reality and the representation of reality that characterize the trompe l’oeil—the striving for verisimilitude, the nature of the duplicate, the illusion of perspective and concrete materiality—have also interested many scholars over the centuries and have been analyzed from the perspectives of art history, psychology, perception, semiotics, and the communication sciences.

The French locution trompe-l’oeil (“to deceive the eye”) came into use in Europe during the nineteenth century. It refers to a style of painting that—through the virtuoso expedients of mimesis, perspective, and skillful use of light and shade—induces in the viewer the illusion that what are being observed are real, threedimensional objects when in reality they are actually images painted on flat surfaces.

The origins of the genre may be traced back to the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. Examples of naturalistic painting from the prehistoric period have been found on the walls of caves near Lascaux in southwestern France and Altamira in Cantabria, Spain. Ancient Egyptians often decorated the walls of their tombs with realistic images of everyday objects, but it was during the classical Greek period that artists excelled in the creation of illusionistic effects. In his encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder (23–79 ce) recounts an anecdote that testifies to the early spread of this art form. It is the story of a contest that was held between two well-known artists—Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who lived sometime during the fifth and the fourth centuries bce (but none of whose works, unfortunately, have come down to us)—in order to determine who was the more accomplished painter of visual illusions.

It is worth citing the passage from Pliny and the story that Battersby and Renard may well have known.

Giuseppe Maria Crespi, Libreria, detail, 1725–30, oil on canvas, Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica, Bologna.

Workshop of Baccio Pontelli, Private study of Federico da Montefeltros, 1472–76, intarsia, Palazzo Ducale, Urbino.

Parrhasius and Zeuxis entered into competition, Zeuxis exhibiting a picture of some grapes so true to nature that birds flew up to the wall of the stage. Parrhasius then displayed a picture of a linen curtain realistic to such degree that Zeuxis, elated by the verdict of the birds, cried out that now at last his rival must draw the curtain and show his picture. On discovering his mistake he surrendered the prize to Parrhasius, admitting candidly that he, Zeuxis, had deceived only the birds, while Parrhasius had deceived himself, a painter.3

The popularity of illusionistic painting in the classical age was followed by a hiatus during the Middle Ages, after which precocious examples of trompe l’oeil painting manifested themselves, above all in Italy. Here, beginning in the fourteenth century, some artists started to employ devices typical of this genre, although in widely divergent contexts. A diverting anecdote about Giotto (ca. 1266–1337) was recorded by the architect and art theoretician Filarete (1400–ca. 1469). During Giotto’s apprenticeship under Cimabue (ca. 1240–before 1302), the young painter painted a fly on one of his master’s works as a prank; it looked so real that Cimabue tried to shoo it away. As a mature artist, Giotto would make use of elements of trompe l’oeil in his Allegories of Virtues and Vices (1303–ca. 1305), which decorate the nave of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

Another exceptional example is offered by the trompe l’oeil decoration of the private study of Federico da Montefeltro (1422–1482) in his ducal palace in Urbino (1472–76), realized entirely in intarsia—an elaborate form of wood marquetry—by Baccio Pontelli (ca. 1450–after 1492) and his collaborators. The walls of this studiolo are lined with trompe l’oeil cabinets and bookcases (some with their doors ajar in a most convincingly illusionistic manner) containing objects that denote

the interests of this intellectual, humanist, and civil and military leader: a casket, an hourglass, a lamp, a suit of armor and various weapons, books, writing implements, and scientific and musical instruments. Many of these would subsequently become recurrent objects in the repertoire of a new genre, that of the still life.4

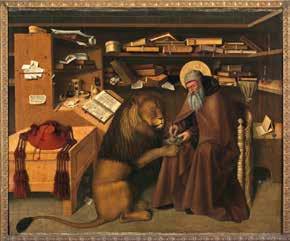

In the history of European painting, toward the end of the sixteenth century many further examples of “optical deception” may be cited alongside these, if only in the form of passages inserted by artists to demonstrate their technical bravura—from the manuscript with its pages set aflutter by the arrival of the archangel Gabriel in the Annunciation by the Master of Flémalle (fl. ca. 1420–ca. 1440),5 to the clogs cast on the floor and the chandelier with its metallic reflections in the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441).6 Also pertinent in this regard are the paintings of scholarly saints bent over their books in studioli whose appurtenances present veritable microcosms of the humanist’s world.7 Not to be forgotten are the books of hours and, from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the offizioli (manuscripts of prayers for noble laypersons), whose margins were beautifully decorated with trompe l’oeil flowers, leaves, and insects by miniaturists trained in the Bruges-Ghent School.

During the Renaissance, authors engaged in new theories of architecture and perspective wrestled with problems such as the ideal vantage point for a painting and how to create an impression of spatial depth or of a solid, three-dimensional object, thus contributing to the perfection of illusionistic effects that broadened and enriched the scope of the genre.

These early examples would be followed by many others, but it was in the seventeenth century that still life painting and its subcategory, the trompe l’oeil—two pictorial typologies that in the future would

Niccolò Colantonio, Saint Jerome in His Study, ca. 145, oil on board, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples.

14 often prove difficult to differentiate—asserted themselves. Paintings of “inanimate objects” gained recognition as a specific and independent typology that was quite the equal of traditional genres such as history painting, figure painting, and portrait painting. Not only were they sought after by refined collectors and aristocratic patrons of the arts, but they also came to be appreciated by a new class of wealthy bourgeoisie.

Beginning in the Low Countries and then spreading to Germany, Spain, and Italy, objects arranged in “formal poses”—books, playing cards, and musical instruments; decorative items and sumptuous drapery; pewter plates and fine glassware; fruit, flowers, and game (wildfowl, hares, etc.)—would come to denote the increasingly popular genre of the still life in Europe. In accordance with the rule that imposed the qualities of “stillness” and “an absence of action,” human figures were rigorously excluded from these compositions, unless in the static form of paintings, prints, drawings, medallions, and cameos scattered among the other objects. Also absent were live animals, apart from the occasional butterfly or other insect. In contrast, flowers were a regular feature due to the growing interest in gardens and in the cultivation of rare and exotic species from distant lands during this period. Some painters began to specialize in the “floral still life,” producing magnificent compositions that were greatly admired by connoisseurs—a subject that has remained popular to the present day.

The technique of oil painting, which was perfected during the second half of the fifteenth century in the Low Countries, and adopted immediately by artists across Europe, was admirably suited to the exacting demands of the genre, allowing artists to capture the smallest details—from the glint of light on a drop of water to the translucent hues of a delicate flower petal—with absolute clarity and precision.8

Sometimes artists would insert into their compositions objects, known as memento mori, alluding to the fleeting nature of existence—a skull, an hourglass, a flickering candle, or a wilting flower. Paintings that employed this device were referred to as vanitas and even if their symbolic and moral meanings were not always easy to decipher, they found favor among more cultivated collectors. One of the earliest examples was of a skull in a niche by Jan Gossaert (also known as Mabuse, ca. 1472–1532).9 Gossaert was one of the first artists to use the architectural niche as a framing device, an innovation that proved so versatile and visually effective it would be used in paintings “of things” well into the modern era.

In comparison to the still life, the trompe l’oeil was, in general, governed by a more rigid set of canons; the artist had to respect the true dimensions of the objects and convey a sense of their volume and mass. In most cases, objects were shown from a straightforward central perspective and portrayed in a clearly defined space illuminated by a diffuse, even light. Finally, to achieve the desired illusionistic effect, the artist had to master a fluid, invisible brushstroke that demanded great technical skill.10

Although, as Jean Baudrillard observed, while the preferred subjects of trompe l’oeil (and still life) artists were the “banal objects” of everyday life, they sometimes indulged in the portrayal of rare or precious objects arranged in a niche or display cabinet, bathed in warm light, and above all rendered with microscopic precision. In some cases, the artist might paint a subject and then “cut it out,” in this way creating a painted object, as in champtourné fret work or human silhouettes painted in trompe l’oeil on flat boards.

Alongside the trompe l’oeil da cavalletto (easel painting), the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries witnessed the spread, as Martin

Battersby noted,11 of “mural decoration” and quadrature (in which the artist decorated a wall or ceiling with architectural elements painted so convincingly that they appear to be a continuation of the existing architecture). There are examples of palatial mansions and country villas decorated with frescoes of imaginary interiors or panoramic vistas, one early and quite spectacular instance being the Sala delle Prospettive (1519) painted by Baldassarre Peruzzi (1481–1536) for the Villa Farnesina in Rome.12

During the Golden Age of Dutch culture, the trompe l’oeil, like the still life, reached a high point in terms of artistic expression,13 as seen in the clever trompe l’oeils and elegant vanitas produced by Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts (active 1659, died 1672) 14 and A Cabinet with Objects by Georg Hainz (1630/31–1670/1700).15 Alongside these, a classic of the genre is the Scarabattolo (Cabinet of Curiosities) 16 attributed to Domenico Remps (1620–1699), a Flemish painter who settled in Tuscany during the second half of the seventeenth century. This fascinating composition presents much of the vast armamentarium of the trompe l’oeil, from the handwritten missive stamped with sealing wax to a sheet of paper with its edges starting to curl, and from seashells, corals, and other natural history specimens to cameos and small paintings (“paintings within a painting” of landscapes, marine scenes, and even a floral still life).17 Indeed, it is worth noting that many of the objects depicted in these trompe l’oeils could also be found in the Wunderkammern (cabinets of marvels) of the baroque period in which man-made artifacts (Artificialia) were displayed alongside curiosities (Curiosa) and scientific specimens (Naturalia).18

Some of the stratagems used in the trompe l’oeil to deceive the eye—for example, objects that appear to spill out of the confines to which they were assigned and invade the space between the viewer

Jan Gossert, Skull. Back of the Carondelet diptych, 1517, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photograph by Jean-Gilles Berizzi.

Giuseppe Maria Crespi, Libreria, detail, 1725–30, oil on canvas, Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica, Bologna.

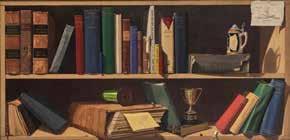

Kenneth Davies, The Bookcase, 1951, oil on canvas, Wadworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT. Photograph by Allen Phillips.

and the painting—can generate a sort of visual hallucination, almost convincing the observer that he is looking at real objects. The effect produced by this manner of conveying visual information—based on the impression of verisimilitude (in which the “false” appears to be “more real than reality itself”) and on the ambiguous borderline between the internal space occupied by the trompe l’oeil objects and the external space occupied by the viewer—may provoke a sense of disquiet and disorientation, projecting the viewer into the sphere of the imagination and even the subconscious.19

Furthermore, as in many still lifes, the objects depicted in the trompe l’oeil could contain hidden meanings, allegories, and enigmas alluding to symbolic or moral concepts, or to the personal attributes of the artist or patron. The viewer is thus presented with the challenge of decrypting abstruse allusions or solving veritable rebuses. Sometimes the trompe l’oeil painter might tease the viewer by placing his signature in a wholly unexpected, almost hidden place, unlike his fellow artists, past and present, who would sign their works with a flourish, for example framed in a real or trompe l’oeil cartouche.

Another phenomenon that came to characterize both of these pictorial genres over the course of the eighteenth century was a certain degree of repetitiveness in the subjects portrayed. For example, paintings with books as their theme were highly regarded, as may be seen in Composition aux livres by Jean Baptiste Oudry (1686–1755).20 Such works can be traced back to an older tradition exemplified by The Open Missal (ca. 1570) by the German artist Ludger tom Ring the Younger (1522–1584).21 Books would continue to provide fertile terrain as visual motifs for the trompe l’oeil artist down to the modern age.

Beginning with the single volume lying on a table, eventually entire compositions dedicated to the theme began to appear—shelves or bookcases with tomes arranged in piles or neat rows, sometimes with the title and author’s name displayed on the spine. One noteworthy example is a painting completed around 1725–30 by Giuseppe Maria Crespi (1665–1747) of Bologna, which depicts a cabinet divided into two compartments of bookshelves containing a series of leather-bound volumes. The works on the subject of music must have been consulted frequently for they are well-worn, and to enliven the composition the artist has added some sheet music, plumes, an inkwell, and other objects that might be found in a cultivated scholar’s study.22 A Still Life with Books by François Foisse (called Brabant, fl. 1740s) dates to about the same period, while a modern variation on the theme—The Bookcase—was painted in 1951 by the American artist Kenneth Davies (b. 1925); both of these can be seen in the collections of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut.23

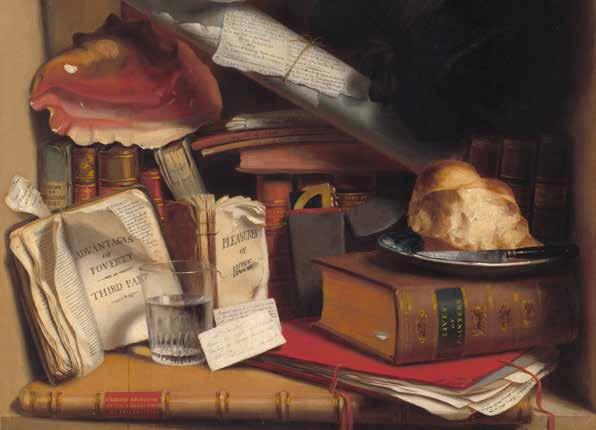

Other themes persisted in trompe l’oeil paintings, such as figures portrayed in grisaille to imitate sculptures.24 The world of music provided a rich source of motifs, with artists demonstrating their skill in the representation of the curves and varnished wood of a violin or the shiny metal of a brass instrument.25 Also popular were pictures that reproduced collections of flat objects—handwritten letters, pamphlets, newspaper clippings, maps, sheet music, engravings, drawings, and, following their invention, photographs—strung along a line attached to a wooden panel or wall.26

notes

1. Jean Baudrillard, “The Trompe-l’oeil,” in

Calligram: Essays in the New Art History from

France, ed. Norman Bryson (Cambridge, 1988), 53–62.

2. Pietro Accolti, Lo Inganno degl’occhi (Florence, 1625).

3. Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia 35–65.

Citation drawn from Norman Bryson,

Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still

Life Painting (London, 1990), 30; on this topic, cf. “The Grapes of Zeuxis,” in Deceptions and

Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l’Oeil Painting, ed. Sybille Ebert-Schifferer (Washington, DC, 2002), 109–221.

4. Alberto Veca, Inganno & Realtà. Trompe l’Oeil in Europa xvi–xviii sec. (Bergamo, 1980), 11–12.

5. Master of Flémalle (usually identified as

Robert Campin, ca. 1375/1379–1444),

Annunciation, 1410s, oil on oak wood, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels.

6. 1434, oil on oak, National Gallery, London.

7. Niccolò Colantonio, Saint Jerome in His Study, ca. 1445, oil on board, Museo di Capodimonte,

Naples; Antonello da Messina, Saint Jerome in

His Study, 1475, oil on lime, National Gallery,

London; Vittore Carpaccio, Saint Augustine in His Study, 1502, oil on panel, Scuola di San

Giorgio, Venice.

8. A number of still life paintings were donated by Paul and Bunny Mellon to the National

Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where they can be seen today, including: Balthasar van der Ast, Basket of Fruits, ca. 1622, oil on panel; Jan Philip van Thielen (1618–1667), Roses and a Tulip in a Glass Vase, ca. 1650/60; John Frederick Peto, The Blue Envelope, ca. 1890s, oil on wood; Henri Fantin-Latour, Still Life with Mustard Pot, 1860, oil on canvas; Claude Monet, Still Life with Bottle, Carafe, Bread, and Wine, ca. 1862/63, oil on canvas.

9. 1517, oil on wood, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

10. Miriam Milman, Trompe l’Oeil Painting: The Illusions of Reality (New York, 1982).

11. Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil: The Eye Deceived (New York, 1974), 53–74.

12. Cf. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 2; Veca, Inganno &

Realtà, 21; Annamaria Giusti, ed., Inganni ad arte. Meraviglie del trompe l’oeil dall’antichità al contemporaneo (Florence, 2009), 81–97.

13. Ingvar Bergström, Dutch Still Life Painting in the Seventeenth Century (New York, 1956).

14. The Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, has three paintings by Cornelis Norbertus

Gysbrechts: Trompe l’Oeil with Violin, Music

Book and Recorder, 1672, oil on canvas; Letters,

Papers, etc. on a Board Partition, 1659–75, oil on canvas; Trompe l’Oeil: A Cabinet of Curiosities with an Ivory Tankard, 1670, oil on canvas; and two paintings by Georg Hainz: A Table with

Drinking Vessel and Confectionery, 1645–88, oil on canvas; A Cabinet with Objects of Art, 1665–67, oil on canvas.

15. Ca. 1666, oil on wood, Hamburger

Kunsthalle, Hamburg. 16. Ca. 1690, oil on canvas, Museo Opificio delle

Pietre Dure, Florence.

17. Cf. Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions, 258–59; Giusti, Inganni ad arte, 75–80.

18. Adalgisa Lugli, Naturalia e Mirabilia. Il collezionismo enciclopedico nelle Wunderkammern d’Europa (Milan, 1983); Joy Kenseth, ed.,

The Age of the Marvelous (Hanover, NH, 1991).

19. “Trompe-l’oeil,” in L’altro occhio di Polifemo, ed. Giorgio Celli (Bologna, 1978), 189–200;

Daniel J. Levitin, ed., Foundations of Cognitive

Psychology: Core Readings (Cambridge, 2002).

20. Musée des beaux arts, Montpellier.

21. Ebert-Schifferer, Deceptions and Illusions, 184–85.

22. Libreria, 1725–30, oil on canvas, Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica,

Bologna.

23. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 100–103.

24. Michel Faré and Fabrice Faré, La vie silencieuse en France. La nature morte au xviii siècle (Paris, 1997), 276–84.

25. Veca, Inganno & Realtà, 128.

26. Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil, 122–35.