43 minute read

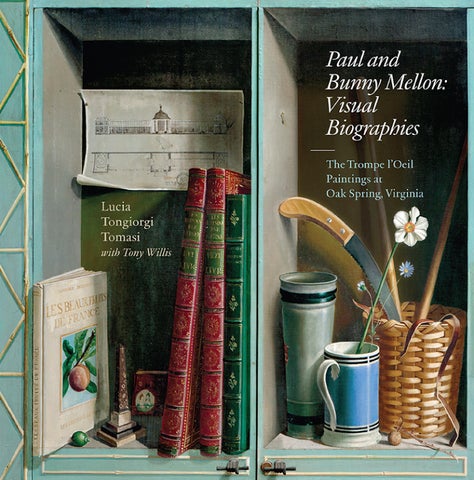

The Decoration of the Greenhouse by Fernand Renard

The Decoration of the Greenhouse by Fernand Renard I

Bunny inherited a passion for gardening from her maternal grandfather. As her own knowledge of gardening and garden history grew, she came to appreciate the activity as a rich and complex cultural phenomenon, a harmonious convergence of nature, botany, horticulture, art, and material culture that was perfectly consonant with her own interests, tastes, and aspirations as a gardener. It was this vision that inspired her, not only in the layout of the grounds for the family’s new home, a gracious mansion of whitewashed stone at Oak Spring, but also in the building of a formal greenhouse to complement the estate’s vast expanse of flower beds, orchards, lawns, and meadows, in which she could carry out horticultural experiments and cultivate seedlings and plants for her garden.

All of Bunny’s gardening projects reflected her refined intuition, but she allowed herself to be influenced by examples from the past, finding ideas that she could apply in a manner that harmonized with her own vision for her garden. Thus, she turned to the French tradition for the design of her formal greenhouse, which was then constructed by the New York architect H. Page Cross (1910–1975). A brief letter from Bunny’s secretary to the architect sent early in 1959 shows how closely she followed the project from beginning to end. After providing Cross with Renard’s address, which he had apparently requested, the letter continues, “Mrs. Mellon also asked me to say…that she is not yet ready to go ahead with the greenhouse. She is sure you understand that she does not want you to go ahead, but she wanted to make certain there would be no misunderstanding as she will want to make some modifications.” 72

The formal greenhouse was no mere conservatory, but a carefully designed and functional building consisting of two long wings, each wide enough to accommodate two rows of plantings—one bed along the inner stone wall and a bench along the length of the outer glass wall. Bunny then devised a pleasing architectural feature to vary the utilitarian aspect of the building—a quadrangular pavilion intended to serve as a vestibule with a hidden workbench, while also providing access to the two wings, each of which ends with its own small pavilion. The vestibule is a beautiful and unusual space, with diffuse light streaming through the glass doors to the right and left, and evocations of eighteenth-century French Orientalism in its architecture and decor.

Perched on the roof of the pavilion is a lead urn in the eighteenthcentury style containing a magnificent floral arrangement beautifully wrought from several kinds of metals. This piece of garden sculpture was conceived by Jean Schlumberger (1907–1987), a French jewelry designer who came to the United States after the Second World War and became one of Tiffany & Co.’s most celebrated collaborators. Bunny admired the sophistication and imagination of the artist’s work, which included a vein of whimsy, particularly in his interpretations of nature. She and “Johnny” became close friends and in 1959–60 she asked him to propose some ideas for the decoration of her greenhouse. In the archives of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation are eight studies by the artist pertaining to this commission.73

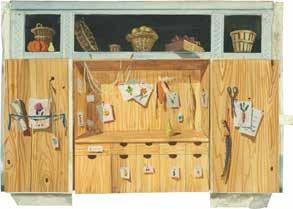

Bunny devoted a great deal of thought to the layout, furnishing, and decoration of her pavilion. She had wooden cupboards built into the walls of the room, drawing inspiration from L’Art du Menuisier (The Art of the Joiner), an exhaustive treatise on woodworking that was published in several volumes from 1769 to 1774 by the celebrated Parisian cabinetmaker André Jacob Roubo (1739–1791) under the

Bunny Mellon in her formal greenhouse at Oak Spring, 1962. Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photography, New York.

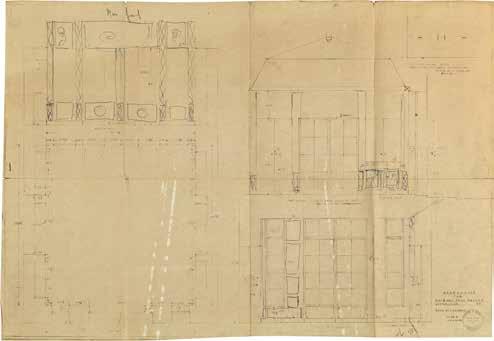

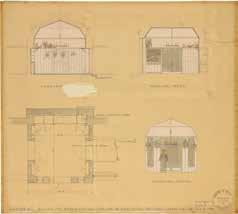

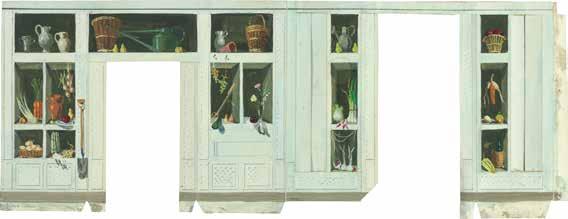

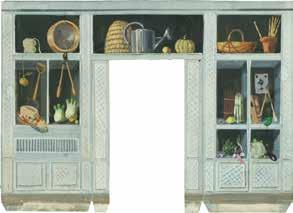

Three architectural plan proposals from Cross & Son Architects: “Central Block of Greenhouse for Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, Upperville, VA, Feb. 21, 1958” (above); “Greenhouse for Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, Upperville, VA, Made by C. Handback Jan. 26, 1959,” (left); “Mellon Greenhouse Made by C. Handback, Rec’d 2/4/59” (right), Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

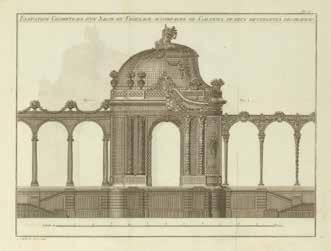

André Jacob Roubo, Elévation Géométrale d’un Salon de Treillage Accompagné de Galeries de Deux Differentes Décorations, folded engraving, from L’art du treillageur, ou Menuiserie des jardins (Paris, 1775), plate 365, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Jean Schlumberger, Design sketch and photograph of the finial on the formal greenhouse, a vase with flowers, ca. 1960, Gerard B. Lambert Foundation and Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Formal greenhouse at Oak Spring, ca. 1960s. Photograph by Louis Reens.

auspices of the Académie royale des sciences. The son and grandson of master cabinetmakers, André Jacob Roubo added to his training an apprenticeship under the architect Jean François Blondel (1681–1756). 74 His manual was a true product of the Enlightenment and reflected its ideals, which included a respect for the work of the craftsman and an appreciation of the role played by material culture not only in the economy of the country, but also in its history and culture. It is worth noting that the seventeen volumes of Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie—significantly subtitled Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers—and its eleven volumes of Planches contain many entries on tools and machines complete with illustrations. Similarly, Roubo’s manual was accompanied by 389 engravings based on drawings by the author, which depict every imaginable type of furnishing that could be made out of wood—from decorative paneling and furniture to carriages and even stages, sets, and machinery for the theater. Of particular interest to Bunny was the section on L’art du treillageur, ou Menuiserie des jardins, which presents garden furnishings (with diagrams, elevations, and enlarged details) ranging from benches and planters to various types of treillages or trellises; indeed, she adopted some of Roubo’s trellis designs for her own garden. Thus, she had the quadrangular vestibule entirely lined with cupboards, providing useful storage space and even a small cubicle to serve as a workbench and potting space concealed behind a pair of folding doors. Such was Bunny’s passion for detail that the cupboard doors are furnished with charming replicas of antique French handles made of iron cast in the form of a hand clutching a rod.

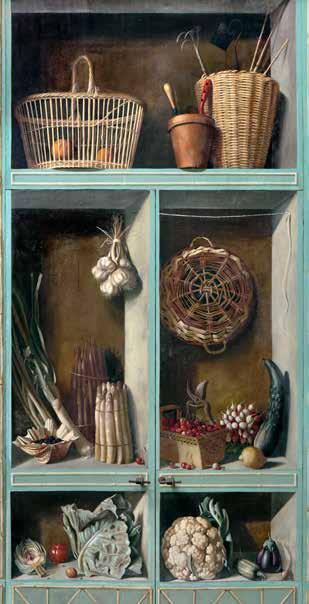

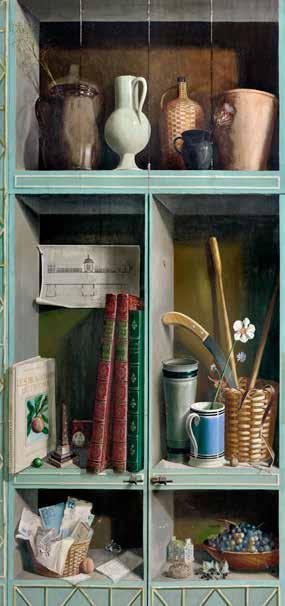

Bunny would go much further, however, and her vision transformed the greenhouse vestibule into a work of art that reflected her personality and interests. She decided to have the room decorated en trompe-l’oeil to give the impression that one was entering the studiolo of a Renaissance scholar and student of the science of nature. Like the study of Federico da Montefeltro, the cupboards lining the vestibule have been disguised by a series of trompe l’oeil shelves and cabinets. The walls are decorated with a motif of slender lengths of bamboo arranged in geometric patterns against a pale blue-green background, all directly inspired by Roubo and the eclectic vogue for chinoiserie in eighteenth-century France. The trompe l’oeil cabinets at floor level are embellished with the same bamboo latticework against a celadon-green background, with the addition of a sheaf of wheat—the symbol of agriculture for the French Republic—at the center of each pair of trompe l’oeil cabinet doors.75

This use of trompe l’oeil painting to disguise the real furnishings is a pleasing conceit, but what makes the decoration so original is that it consists of trompe l’oeil shelves filled with a vast array of objects both large and small, precious and ordinary, that invite perusal one by one. In fact, Bunny’s vision of what the room should look like and signify took her well beyond mere embellishment. While the objects depicted are all linked to her beloved garden, the composition is reminiscent of the paintings of cabinets of curiosities executed in the rigorously realistic style of the trompe l’oeil.

The painter chosen for this commission was also French—Fernand Renard, born in Paris in 1912, but of whom little more is known.76 He showed a gift for drawing at an early age and was encouraged to enroll at the École des arts plastiques in Paris, where he studied the decorative arts and fresco painting. After leaving school, he found employment designing commercial advertisements and cinema posters. A poster with the faces of the comedians Laurel and Hardy, drawn by him for a movie theater, still survives. After collaborating for a short

period with the painter Auguste Desiré Parus (dates unknown) as a glass decorator, Renard’s career was abruptly interrupted by the war. He joined the French army in 1939, was imprisoned by the Germans, and returned to France in 1945.

Settling once again in Paris, he picked up the threads of his life and his career with some difficulty, and began painting still lifes. Various exhibitions of his work were held, through which he earned a degree of recognition and had the opportunity to meet patrons of the arts from both sides of the Atlantic. While the roots of his style lay in the tradition of the northern European painters of the seventeenth century and in the French school of still life painting, Renard would later declare that his art was inspired by “my desire to evoke the significance and the charm the subject holds for me, and also by my desire to create, in the end, a beautiful object.”77 His pictures had a particular appeal for English and American collectors; the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and the socialite Anne Ford Johnson (who served on the White House Fine Arts Committee under the Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy administrations and on the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art) acquired more than one painting by Renard for their collections.78 Several paintings by Renard were also acquired by William Perry (1910–1993), a classmate of Paul’s at Yale and a neighbor of Bunny and Paul, at Oak Spring. Various still lifes and trompe l’oeils by Renard’s hand occasionally resurface at art auctions, primarily in the United States.

It is possible that Bunny’s attention was drawn to the artist by Frederick P. Victoria, who, according to surviving accounts, befriended Renard in the 1950s.79 Victoria was a well-known antique dealer in New York City who also provided decorating services, serving as an intermediary between wealthy clients and fine furniture makers, artisans,

Fernand Renard, ca. 1970. Photograph by Derry Moore.

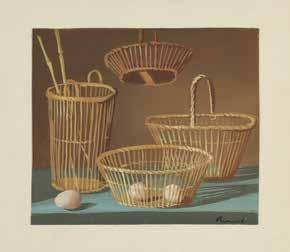

Note card to Bunny from Fernand Renard (front), Four baskets, three eggs, and two bamboo sticks, 1964, body color drawing, Gerard B. Lambert Foundation.

Four preliminary pencil drawings, one with body color, of the Oak Spring formal greenhouse, possibly by Fernand Renard, not dated, Gerard B. Lambert Foundation.

and artists. Alternatively, Bunny could have met Renard through Paul Manno, a friend of Victoria and manager of the New York office of Maison Jansen, a celebrated Parisian firm of interior decorators that would later participate in the redecoration of the White House (1961–63) for First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy (1929–1994). It seems that the French painter decorated various pieces of furniture for Maison Jansen.80 There is a wardrobe decorated in trompe l’oeil that Stéphane Boudin of Maison Jansen installed for Jacqueline Kennedy in her White House dressing room.81 While perhaps not by Renard, it does reflect the taste of the period for such refined effects.

It can be assumed that the artist began the greenhouse project at Oak Spring in 1959 and completed it the following year. He left his signature and the date—“Renard 1959–1960”—on one of the trompe l’oeil panels on the north wall of the vestibule.

Renard’s Initial Proposals for the Greenhouse Trompe l’Oeil

In seeking to meet the expectations of his cultivated and exacting patron, the decoration of the greenhouse must have presented the artist with quite a few compositional challenges. Many discussions were probably held before Bunny approved the final version and the phases in this process can be at least partially retraced in surviving proposals.

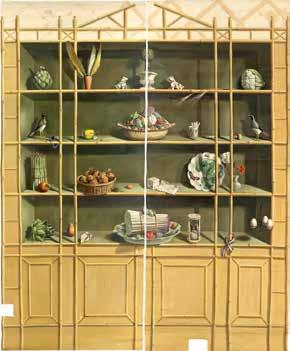

A sketch by Renard, painted on canvas and glued to a cardboard backing board, still exists and provides evidence of the design process.82 It depicts a trompe l’oeil cabinet made of yellowish-brown wood decorated with strips of bamboo arranged in a geometric pattern. Closed cupboards form the base, supporting a set of four open shelves on

Fernand Renard, Initial maquette proposal for the formal greenhouse, diluted oils on canvas, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

58 which a variety of objects have been arranged, beginning with some splendid pieces of antique porcelain: a large serving bowl; a tureen with a cover imitating an arrangement of vegetables; a plate decorated with a motif of leaves, butterflies, and insects; and porcelain tureens and boxes in the form of a cauliflower, a bundle of white asparagus, and a lemon complete with a leaf. The Mellons owned a fine collection of rare porcelain, which Bunny sometimes used to decorate her table when entertaining guests for lunch or dinner. 83

In this composition, the artist is obviously playing with the theme of the difference between reality and artifice. Alternating with the pieces of porcelain are some real fruits and vegetables—a basket of lemons sits on the shelf beneath the ceramic citrus; a small, covered tureen in the form of an artichoke with a bird-shaped handle sits on the top shelf, while a real artichoke of another variety lies on its side on the bottom shelf. Also portrayed in an almost desultory manner are a real pear, persimmon, and bunch of asparagus arranged side by side with other objects: a hanging basket containing three eggs, three feathers in a terra-cotta cup, two small seashells, a glass vase containing two carnations, a matching pair of bird statuettes with two cornflowers lying at the feet of one of them, an airmail envelope addressed to “Madame Paul Mellon,” an hourglass, a large die, and a delicate china cup in the form of a striated tulip that holds some cigarettes. The artist has also inserted a passing reference to the country of his birth (and to Bunny’s love of all things French) in the form of a tricolor ribbon looped around one of the bamboo rods that visually separate the shelves into three compartments. 84

In the restrained composition proposed by Renard, a small number of carefully chosen objects, featuring pieces from the Mellons’ collection of porcelain, have been meticulously arranged. Bathed in a golden-green light, they seem to be suspended in a world of absolute stillness lying outside of time. In this rarefied atmosphere, even the eggs in their basket appear to float as if in a painting by Magritte. As will be seen, however, Bunny had an entirely different visual idea in mind—an exuberantly chaotic arrangement of everyday objects, each of which was in some way significant to her: the gardening tools that she always had to hand; plant pots, labels, and bits of broken terra-cotta; a variety of baskets; odd objects that she came across and kept just because she liked their shapes; and of course flowers, fruits, and vegetables from her garden. She wanted the objects in her trompe l’oeil to be imbued with an uncompromising corporeality, an effect that was further accentuated by Renard’s chiaroscuro lighting.

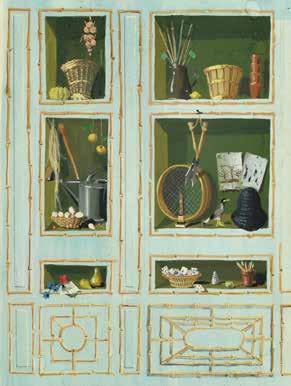

Other material in the archives of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation reveals that much work and discussion was necessary before the final design was approved. In particular, there is a small threedimensional paper model in pencil, watercolor, and body color with a proposal for the decoration of the greenhouse vestibule, which now depicts shelves crowded with a variety of objects. Attached to it is a maquette for the ceiling decoration. 85 The color scheme for the cabinets remained the warm, yellowish-brown tone of Renard’s first project, while the domed ceiling (embellished with the same bamboo motif) was tinted a pleasing pale blue-green, the background color that Bunny finally chose for the room. Recently, another eight sketches have come to light in which the artist and patron were clearly working out the grouping of the objects and the sequence of the panels, compositional solutions which, however, were not all incorporated into the final design. They provide a fascinating insight into the creative process and the close collaboration that led to the final result one can see today. 86

The decoration of the greenhouse must have constituted a pivotal moment in Renard’s career as an artist. From that time forward, he would concentrate on painting still lifes, mostly arrangements of fruit, but also flowers and shells, many of which recall the objects in the trompe l’oeil at Oak Spring. During the following decade or so, various exhibitions of his work were held, primarily in New York City. In 1961, and therefore just one year after he completed his commission for Bunny, the Carstairs Gallery in New York organized a show of about twenty of his paintings. In the catalog, Renard described himself as a “painter of reality” and stated “the necessity for painting to depict the truth.” The Hammer Galleries in New York presented several exhibitions of his work, first in 1968 and then in 1972, 1973, and 1975. 87

In the archives of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation are a few letters sent by Renard to his patron. Of particular interest is a letter posted from Viviers on July 15, 1960, in which Renard thanks Bunny for telephoning him during his stay in Paris and mentions some mutual “American friends,” in particular a certain “Johnny” (Schlumberger) and his sister Jacqueline. In a second, more candid letter sent on December 18, 1961, from 10, rue Fargeau in Paris, Renard informs Bunny that his father is in poor health, and then expresses his fear that she was perhaps disappointed with his work, along with his sincere regret that this might be so. However their contact continued until at least 1978, and he was also an acquaintance during the 1960s and 1970s of Bunny’s daughter Eliza Lloyd Moore and her then husband Derry Moore. 88

Fernand Renard, Later maquette proposal for the formal greenhouse, diluted oils on canvas, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Fernand Renard, Further set of maquette proposals for the formal greenhouse, body color drawings, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Bunny Mellon in her formal greenhouse, ca. 1960, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

The Completion of the Greenhouse

A charming photograph (see page 103), probably taken in 1960, shows Bunny in the vestibule of her greenhouse, smiling and holding a basket. 89 The trompe l’oeil decoration of the room appears to be complete. It obviously constituted an extraordinary collaborative undertaking between the artist Fernand Renard and Bunny Mellon, whose role could be likened to that of a Renaissance patron of the arts. She made clear her wishes with regard to every aspect of the commission: the overall composition of the work, the themes linking its various parts, the objects that she wanted to be included and how they should be arranged, and finally the sequence to be followed in assembling the various parts of this complex work. For his part, Renard brought to the enterprise not only his technical skill in the rendition of the physicality of objects, but also suggestions based on his extensive knowledge of the European, and in particular the French, tradition of the genre, which often featured shelves bearing a miscellaneous collection of objects. He could have pointed out many examples, such as the Trompe-l’oeil à la statuette d’Hercule by Jean Valette-Falgores Penot (1710–after 1777). 90

From this joint effort an extremely sophisticated work came into being, in a creative process that granted the two parties the opportunity to interact in a unique fashion. An allusion to this conjunction of two distinctive, intelligent, and cultivated minds may be found on one of the shelves, where Renard painted a vase holding a French flag.

The final work, painted in diluted oils, portrays hundreds of objects in their natural dimensions, some quite large and others very small, in a recreation of Bunny’s world. As was so often the case in still lifes from

the past, each object was invested with personal meaning or references to the patron’s family and friends. However, unlike the trompe l’oeil painted by Martin Battersby, which contains objects that in large part allude to the ideals and cultural preferences of Paul, the panels painted for the greenhouse did not indulge in any form of veiled symbolism. This would have been inconsistent with the fundamentally open and extroverted personality of his patron. Bunny usually sought to guard her privacy, but in what was quintessentially “her realm”—the garden at Oak Spring—she was willing to show an important side of herself through a selection of objects that could “tell her story.”

Upon crossing the threshold of the pavilion, one finds oneself in a place like no other. The pronounced three-dimensionality of the trompe l’oeil shelves filled with an array of objects form a veritable continuum that may generate surprise, or even a slight sense of vertigo and claustrophobia, despite the glass doors to the left and right that open onto the two wings of the greenhouse, providing a light-filled vista of long rows of carefully tended plants. The enclosed space of the room is amplified by a multiplicity of perspectives that create, through the optical illusion of this pictorial cycle, the sensation of entering a world of “circular time” (to borrow an expression from Jorge Luis Borges), in which one is forced to return again and again to things already seen, as if standing in a hall of mirrors.

The initial impression of chaotic profusion and horror vacui dissipates, however, as one turns around the room and begins to focus on the objects one by one. It then becomes clear that they have actually been quite carefully chosen and arranged, and the result is an intricate series of still lifes composed—as Baudrillard perceptively observed—of “banal” and heterogeneous objects that have accumulated over time, as such things tend to do. For the most part they belong to the material

Bunny Mellon in her formal greenhouse, 1982. Photograph by Fred Conrad.

64 culture of mid-twentieth-century America and in particular to the activity of gardening, but they were objects to which Bunny assigned a value that was anything but abstract and theoretical.

Banal they may be, captured by the artist and portrayed on the trompe l’oeil shelves of the greenhouse with no ostentatious display of erudition, and yet—divested of their original functions and decontextualized—these objects take on an independent existence, living their own “silent lives,” immobile and passive, in an almost metaphysical dimension. With their invitation to silent contemplation, these objects speak for their owner directly and eloquently, conveying her thoughts and the sources of her inspiration.91 It will not be possible to give here a circumstantial account of every item depicted in the greenhouse trompe l’oeil; however, a summary is provided in the detailed description that accompanies this essay (pages 115–126).

At first glance, the shelves of Bunny’s imaginary Wunderkammer are filled with a seemingly haphazard collection of tools and other materials familiar to every gardener, from pruning shears in different sizes to spades, dibbers, a trowel, a scythe, balls of string, a spool of wire, lengths of raffia and leather straps, stakes with labels on which the names of plants could be written, bamboo poles, a hammer, wooden pegs, even some nails. Half hidden on one shelf is a packet of cornflower seeds, while other seeds seem to have been left forgotten in a fold of paper.

The illusion includes a variety of containers: watering cans, plant pots (including one that has been broken and four others in a nested pile), demijohns, bottles and pitchers, cups, bowls, glasses, mugs, and a large soup tureen in the form of a pumpkin (just one of the many pieces in the Mellons’ collection of antique porcelain). Baskets in different shapes, sizes, and materials (wicker, reed, wood…) sit on shelves or hang from nails; one contains letters, others are filled with fruits or vegetables. These had been collected over the course of many years and were kept in a special “Basket House.” A delicate basket fish trap (perhaps from the Greek islands) was a gift from Jacqueline Kennedy, as is disclosed by a card tied to the object with a red ribbon. 92

In this conglomeration, a few personal effects from which Bunny was rarely separated have been included, such as her beloved ivoryhandled pruning scissors, blue cloth hat, gardening coat, leather gardening gloves, and two band rings designed by Schlumberger (which will be discussed below).

Some of the other items can still be found, more than fifty years later, at Oak Spring. They may have been gifts that had a special meaning for Bunny, from the gold powder compact by Schlumberger to the little glass rabbit that recalls her nickname, a miniature obelisk (perhaps a gift from Battersby, who was fascinated by Egyptian monuments), a small house in glazed porcelain, and a curious wire basket with dangling metal discs.

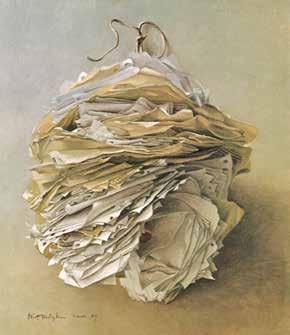

To accentuate the trompe l’oeil effect, the traditional theme of paper is represented in various forms, from handwritten notes and a basket of letters to engravings tacked to the shelves (perhaps a reference to Charles Bird King’s Poor Artist’s Cupboard). Of particular interest are an architectural drawing of the greenhouse prepared by the firm of H. Page Cross and dated November 19, 1957; one of Schlumberger’s sketches for the floral urn that decorates the roof of the greenhouse pavilion; and a poem written by Paul which will be discussed below.

The greenhouse shelves would not have been complete without books, each of which—like those in the trompe l’oeil bookcase painted

Fernand Renard, Trompe l’Oeil in the Formal Greenhouse at Oak Spring, details from west wall, 1959–60, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Fernand Renard, Trompe l’Oeil in the Formal Greenhouse at Oak Spring, details from east wall, 1959–60, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Fernand Renard, Trompe l’Oeil in the Formal Greenhouse at Oak Spring, details from west (left) and east (right) walls, 1959–60, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

by Battersby for the living room—had a special significance reflecting the interests of the artist’s patron. By the end of the 1950s, Bunny had already assembled a large collection of antique and modern books on gardens, gardening, horticulture, and plants, to which she would continue to add over a lifetime. Realizing that a place was needed to house this collection, with the encouragement of her husband an architect was chosen—Edward Larrabee Barnes (1915–2004)—and commissioned to design and construct a library on the estate. The project was completed in 1981, extended a decade later, and the result is a truly extraordinary place for research and study nestled in the rolling hills of Virginia.

The titles of many of the books in the trompe l’oeil are clearly legible and represent works to which Bunny was greatly attached. On one of the shelves appear the three volumes, bound in leather and marbled paper, of Le jardin fruitier, a treatise on the cultivation of fruit trees and fruiting plants published in 1821 by the eminent botanist and gardener Louis Claude Noisette (1772–1849). This was one of the first gardening books acquired by the young Rachel and she turned to it time and time again, finding “Noisette” an inexhaustible font of ideas and practical advice.93 Le jardin fruitier is illustrated with beautiful engravings, and Bunny chose two of them—one depicting gardening tools and the other grafting techniques—for inclusion in her trompe l’oeil. Renard reproduces them faithfully on a cupboard door in the east wall, attached to the back of one of the shelves by drawing pins; one sheet is creased and the lower edge of the other curls upward, adding to the impression of depth and tactility.

Also identifiable is a copy of the magnificent and extremely rare two-volume folio publication on the grape, Le raisin, ses espèces et variétés, dessinées et colorées d’après nature by the German botanist Johann Simon Kerner (1755–1830), published in Stuttgart from 1779 to 1810 with illustrations colored by hand. (The copy at Oak Spring is bound in red and green leather with gold tooling, with the title “Les Raisins par Kerner” and the volume numbers “i–vi Livr” and “vii–xi Livr” on the spines.)94 Also included are Les beaux fruits de France (1947) by the nurseryman and expert on roses and fruit trees Georges Delbard (1906–1999), with its elegant cover facing the viewer, as well as “Stirpium imagines lxxv quas ex horto patavino delineavit…” (1776), a superb manuscript consisting of seventy-five watercolors by the Italian botanical artist Baldassare Cattrani (fl. 1776–1810) that has never been published.95 There is even a copy of the March–April 1958 issue of the New York Botanical Garden’s periodical The Garden Journal. Finally, Bunny did not forget to ask the artist to include a volume from her delightful collection of illustrated children’s books—Kate Greenaway’s Birthday Book for Children, published in London in 1880, a first edition that shows some signs of wear.

Unlike the books from Paul’s collection featured in Martin Battersby’s trompe l’oeil painting, whose present whereabouts are unknown, all of the books that appear on the shelves of the greenhouse trompe l’oeil can be found in the library at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation.

Portrayed with scrupulous fidelity, skillfully intermingled with the other objects on display are various flowers, fruits, and vegetables, a reminder of this exceptional collector’s love of floral and botanica painting.

A purple and blue striated tulip with its bulb hangs upside down from one of the uppermost shelves, a reminder of tulipomania, the speculation in tulip bulbs that gripped the Dutch Republic in the 1630s. Bunny studied this phenomenon, perhaps the earliest example of a speculative bubble in Europe, long before it became the subject

of general interest, and assembled a considerable collection of rare tracts and illustrated manuscripts from the period. 96

Some leafy stems of Pelargonium zonale, an African geranium, are arranged in a glass; two aster blossoms and an elegant white Narcissus poeticus with a yellow and orange corona spring on long, delicate stems from a mug; and a slender, pyramid-shaped bottle holds two blue cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus). A dried branch of fennel has been placed in a redware pitcher together with a small French flag, while an artichoke balances against the rim of a small black pitcher, its top-heavy inflorescence supported by the large terra-cotta pot standing nearby. A tall redware pitcher contains an arrangement of foxtail grasses with a feather and two fading red poppies. One papery petal has fallen and rests on the shelf next to Bunny’s gardening hat.

Painted on the inside of one of the cupboards is a framed sketch of a red carnation. In another cupboard, Renard reproduces a page from Phytographia curiosa, exhibens arborum, fruticum, herbarum & florum icones, an important botanical text by the Dutch physician Abraham Munting (1626–1683) that was published in Amsterdam in 1713. It is illustrated with 245 botanical engravings to which Munting added embellishments such as landscape backgrounds and trompe l’oeil elements. In 1957, Bunny acquired a copy of this work in which each of the plates was colored by hand, with somewhat more imagination than scientific accuracy. For the greenhouse trompe l’oeil, she asked Renard to reproduce the plate of the “Arbutus” (figure 23) (possibly a chokeberry, Aronia arbutifolia) and he did so with meticulous precision, even copying the original artist’s error of coloring the flowers blue. At the foot of the plant appear a spade and a scroll, but Renard replaced the words inscribed on the scroll, “Arbutus humilis virginiana” (Arbutus unedo), with “Ex Libris Bunny Mellon 1960.” 97

Abraham Munting, “Arbutus humilis virginiana” (possibly a chokeberry,

Aronia arbutifolia), hand-colored engraving, from Phytographia curiosa (Amsterdam, 1713), figure 23, folio 125, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

68

In addition to the flowers, which add a touch of color and animation to the composition, the viewer’s eye is attracted by the fascinating array of fruits and vegetables. Sometimes a single specimen is shown sitting on a shelf; here and there one may glimpse a pear, an orange, a peach, a walnut, a few tiny berries… Tied together and suspended on a string are some branches laden with plums, while a pyramid of golden apples and two pears has been arranged on another shelf. There are baskets of strawberries, peaches, and yellow and purple plums, an oblong box with a handle filled with cherries, and even a seashell (Hippopopus hippopopus or bear paw clam) containing some red and black raspberries. Not lacking is one of the traditional subjects of the still life—a bowl of purple and green grapes, with light reflecting off the round berries.

Among the vegetables are a variety of cabbages, one of which has been cut open to expose the pattern of its closely packed leaves. There are two bundles of asparagus, another of leeks, and white and pink radishes tied in a bouquet. Four large artichokes are arranged in a wooden basket, while hanging from the shelves are various bundles of root vegetables—onions, garlic, and small white turnips. On various shelves are a curved head of celery, another of rhubarb, a small lobed eggplant, a cucumber, the cut half of an artichoke, various tomatoes and squashes, some mushrooms, and dried beans in a white porcelain bowl. Scattered here and there are small seeds, nuts, and burrs.

Within this vast assortment of inanimate objects, “living” things are absent with the exception of two tiny insects on the walls and two European butterflies (Papilio machaon and Aglais io), which seem so motionless that they could have just been taken out of an entomologist’s box. Standing equally still is a somewhat incongruous statuette of a bird, perhaps made of papier-mâché, one of many that could be found in different corners of the Mellons’ home. 98

On one painted shelf is a varied collection of shells, among which are identifiable Conus marmoreus (marbled cone), Nautilus macromphalus, Terebra guttata, Turbo sarmaticus, Conus ebraeus, Conus betulinus, Clanculus pharaonius, and what might be a Pomacea canaliculata (golden apple snail). In the foreground are a purple starfish and a tiny white cowrie shell and at the back a piece of branching red coral. Bunny was fascinated by the beauty and variety of seashells and her library included one of the most exceptional early texts on malacology, Les délices des yeux et de l’esprit, ou, Collection générale des différentes espèces de coquillages, written by Georg Wolfgang Knorr (active 1760–75) and published in Nuremberg from 1760 to 1773. This splendid six-volume edition with hand-colored illustrations was sold at auction by Sotheby’s after Bunny’s death, but another copy (whose plates have not been retouched with color) is in the Oak Spring Garden Library.99

While every object depicted on the walls of her greenhouse was certainly chosen personally by Bunny, it fell to the artist Fernand Renard to provide a suitable context by weaving into his composition references to past trompe l’oeils and still lifes, although it can be imagined that the pair discussed each of his decisions before he took up his brush. In fact, the close ties between the pictorial tradition in Europe and the decoration of the greenhouse is evinced by the many fruits and vegetables portrayed. These were a recurrent topos of the still life over the course of the centuries, beginning with the succulent displays of fruit piled high in baskets and platters in the Fruit Seller by Vincenzo Campi (ca. 1530–1591), one of the first Italian painters to be influenced by the Dutch style of genre painting,100 and the superb Basket of Fruit by Caravaggio (1571–1610).101 Many artists

depicted containers overflowing with the products of nature, such as the French artist Louise Moillon (ca. 1610–ca. 1696), who in her time was considered to be one of the best still life painters in Paris, and the great master Jean-Siméon Chardin (1699–1779). Renard’s cherries and strawberries evoke the luxuriant body color paintings of Giovanna Garzoni (1600–1670) and the “kitchen” still lifes by Jacopo da Empoli (ca. 1554–1640).102 The portrayal of solitary fruits may remind us of the painting of two citrons by Filippo Napoletano (ca. 1587–ca. 1629),103 and the works of some of the great botanical artists of the twentieth century, such as Eliot Hodgkin (1905–1987), from whom Renard may have borrowed the feather motif, and Rory McEwen (1932–1982), an artist who was greatly admired by Bunny and whose work she collected. 104

Renard may also have drawn inspiration from the celebrated work by Juan Sánchez Cotán (d. 1627), Still Life with Quince, Cabbage, Melon, and Cucumber. 105 The Spanish artist rendered the tactile quality of his objects with masterly technique and devised the expedient of suspending the glowing quince and rough cabbage, each by a single thread, so that they seem to float against the dark background of the painting. Perhaps Renard’s device of tying together branches of fruit or bunches of vegetables with string and hanging them from the shelves can be traced back to this work.

Another recurrent motif of the still life is the asparagus, a vegetable depicted by various artists over the centuries, beginning with Adriaen Coorte (1659/1664–1707 or after), who made a bundle of asparagus the focal point in several of his compositions. One such composition by Coorte may be found in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Among the series of small still lifes produced late in the career of Edouard Manet (1832–1883) are two dedicated to the asparagus, one a bunch of

Eliot Hodgkin, Robert Sielle’s Files, 1967, from Martin Battersby, Trompe l’Oeil: The Eye Deceived (New York, 1974), 97.

Balthasar van der Ast, Basket of Fruits, ca. 1622, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

white asparagus lying on a bed of greens, and the other a single stalk, which he gave as a gift to the collector who bought the first painting, with a note: “There was one missing from your bunch.” 106

On opening some of the cupboard doors, one discovers that they have been decorated on the inside as well. These panels kindle both interest and curiosity, as virtuoso examples of trompe l’oeil painting and for the glimpse they provide of Bunny’s workaday world as a gardener. In a bravura passage of mimetic painting, Fernand Renard has depicted, as if hanging from hooks on the inside of two of the cupboard doors, a white linen towel with its border decorated in blue, a gardener’s apron, and the Burberry raincoat that Bunny wore when working in the garden in inclement weather. He has skillfully captured the folds and tactile qualities of the different materials from gabardine to linen and cotton. The French artist must have had in mind various works from the past when painting these particular subjects, from the Personal Effects in the Cupboard by the Dutch artist Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678) 107 to Raphaelle Peale’s Venus Rising from the Sea and Henri Cadiou’s Vestiaire d’usine, already mentioned above, in which lengths of cloth are draped over tables or convincingly suspended on hooks or clotheslines.

Among the few costly objects depicted in this trompe l’oeil are two gold and enamel band rings designed by Johnny Schlumberger that Bunny very often wore. 108 Their inclusion is reminiscent of the device employed by many artists—beginning with Georg Hainz and his cabinets of curiosities—of inserting precious objects into their still life and trompe l’oeil paintings, although Renard depicts the rings hanging from a loop of twine attached to the edge of one of the shelves by a drawing pin, where they almost disappear against the backdrop of larger objects.

Since the two artists, Martin Battersby and Fernand Renard, had both studied the works of the great masters of the past, certain conventional subjects appear in their work at Oak Spring. In addition to the theme of the book, there are variations on the motif of the flower in a vase—the carnation in a silver cup in one of the panels for the living room, and many passages in the greenhouse trompe l’oeil, from the dahlia in a glass and the earthenware pitcher of foxtail grasses to the red geranium in a mug, so brilliantly realized it seems to be actually sitting on the shelf that is fixed to the adjacent wall. Butterflies, which enlivened so many Dutch still life paintings from the Golden Age and are depicted more than once in the seventeen paintings on copper by Jan van Kessel conserved in the Oak Spring Garden Library, have also come to rest on the shelves of both trompe l’oeils.

The seashell is another traditional motif, although it was treated differently by our two artists. Battersby gave prominence to three large shells, each sitting on its own—two pearly nautiluses and a green turban, whereas Renard depicted an assorted collection in different sizes, shapes, and colors crowded together on a single shelf, reminiscent of the compositions of Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94–1657) and Adriaen Coorte,109 and perhaps also of the French artist Alexandre-Isidore Leroy de Barde (1777–1828). Leroy de Barde, who was appointed premier peintre d’histoire naturelle by Louis xviii, held an exhibition in Paris entitled “Cabinet des Curiosités” in which he presented a series of trompe l’oeil display cases of natural history specimens, including one with a collection of shells, all executed with astonishing realism. 110

Aesop Pops His Head into the Greenhouse

Fernand Renard must have received the commission from Bunny to decorate the vestibule of her greenhouse not long after Battersby completed his panels for the cabinet in the living room, and it seems that Paul found the contrast between the two projects quite stimulating and diverting. It certainly provided the occasion for many lively conversations as well as some teasing between the couple, who had in all likelihood already worked together with Battersby on the composition of his trompe l’oeil bookshelves.

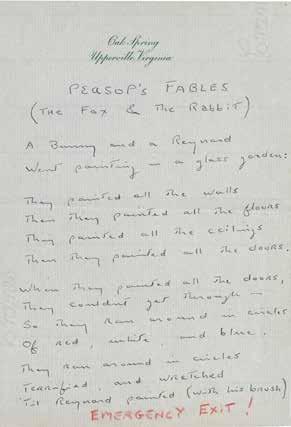

It was a delightful surprise to discover that Paul dedicated a short poem to his wife on the subject of her greenhouse trompe l’oeil. With his classical education and refined taste, he often amused himself by composing such divertissements (in fact he describes himself as a “poet amateur” in his autobiography), and it is understandable that Bunny should have wished to leave a permanent record of this charming homage and gesture of affection (which she saved, together with the original envelope). Renard therefore reproduced the sheet bearing the poem, hanging from a nail to the left of the entrance door to the vestibule. On it one can read:

Oak Spring Upperville, Virginia

PAesop’s FABLES (The Fox & The Rabbit)

A Bunny and a Reynard Went painting in a glass garden: They painted all the walls Then they painted all the floors They painted all the ceilings Then they painted all the doors.

When they painted all the doors, They couldn’t get through –So they ran around in circles Of red, white, and blue.

They ran around in circles Terrified, and wretched ’Til Reynard painted (with his brush) EMERGENCY EXIT!

In his poem, Paul assumes the guise of Aesop, the Greek author of moralizing tales who may have lived during the seventh and the sixth centuries bce. His fables told through animals exhibit an exceptional understanding of human nature and are still read today by adults and, in popularized form, by children.

Temporarily becoming “PAesop” (P + Aesop), Paul composed this cautionary tale about the dangers of being carried away by excessive enthusiasm. No doubt he found it impossible to resist the invitation to make use of the imagery evoked by the names “Bunny” and “Renard” (which means “fox” in French). However, contained in these simple verses are deeper meanings and an acute judgment regarding the trompe l’oeil paintings themselves. It did not escape Paul’s cultivated sensibility that crowding the vestibule space with images might create a sense of disorientation in visitors, amplified by the fact that they

Fernand Renard, Trompe l’Oeil in the Formal Greenhouse at Oak Spring, detail of poem from east wall, 1959–60, diluted oils on canvas mounted to wood, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

Poem written by Paul Mellon, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA.

had to turn around in a circle to follow the sequence of panels. The two little animals responsible for this scheme were beside themselves with excitement, but they too eventually found themselves desperately turning around the room without knowing how to get out, until the Renard came up with the “Alice in Wonderland” solution of painting an “emergency exit” for himself and his confederate.

The original manuscript in Paul’s hand is conserved in an envelope on which he wrote “All my love to Bun,” a testimony to the enthusiasm that united the couple in the realization of the two trompe l’oeils at Oak Spring. Although Paul and Bunny were two highly independent individuals with different personalities and interests, the projects for the two trompe l’oeils at Oak Spring provided the occasion for a true convergence of minds in their discussions of art, culture, and ethical issues.

notes

72. Letter written by Mrs. Mellon’s secretary to Mr. H. Page Cross, dated February 7, 1959,

Oak Spring Garden Foundation archives.

73. Schlumberger’s drawing of the floral arrangement measures 11 3/4 by 9 1/8 inches and the finished piece is approximately five feet tall. Bunny most certainly would have suggested to Schlumberger that he study the floral bouquets in André Jacob Roubo,

L’art du treillageur, ou Menuiserie des jardins (Paris, 1775), plate 374.

74. Among the many larger commissions received by the master artisan-artist Roubo, worth noting is the monumental staircase which he designed for the Paris residence of the

Marquis de Marbeuf.

75. Cf. Roubo, L’art du treillageur, plates 347, 360, 363.

76. Fernand Renard was active in the United

States after the end of the Second World

War and he was better known to collectors there than in France. In the 1980s, he had an apartment in Ménilmontant, Paris, and also a house in Lot. The exact date of his death is not known, but his last communication with

Bunny was in 1978 and he likely died in

France around 1980.

77. Victor T. Hammer, Fernand Renard: Recent Paintings (New York, April 16–27, 1968).

78. Calvin Tomkins, “Love for Sale,” The Art World, New Yorker, August 11, 1997, 64. 79. Tony Victoria, email to Nancy Collins,

December 14, 2017. Tony Victoria (the grandson of Frederick P. Victoria) mentions that his grandfather received some small sketches in the form of greeting cards from

Renard, which his father saved and kept in his art collection. More photographs of Fernand

Renard, plus additional biographical details, were discovered by Elinor Crane.

80. Cf. the same communication from

Tony Victoria.

81. “Master Dressing Room,” White House

Museum, accessed November 8, 2019, http://www.whitehousemuseum.org/floor2/ master-dressing-room.htm.

82. This drawing is conserved in the archives of the Oak Spring Garden Foundation; it consists of two sections whose combined dimensions are 24 ½ by 82 ½ inches.

83. Sotheby’s Auction, 3:207–46.

84. Some of these objects were sold at auction by Sotheby’s. Cf. Sotheby’s Auction, 3:sessions 1 and 2, lot numbers 446, 467, 491, 493.

85. Maquette of the greenhouse vestibule— walls: 5 ½ inches (height) by 15 5/8 inches (circumference); ceiling: 5 ½ by 13 inches; door opening: 2 ¼ inches (width) by 3 7/8 inches (height).

86. These sketches include a penciled grid of 9 3/8 by 9 inches; a section of the ceiling with the proposed lattice motif in pale green-blue: 5 5/8 by 8 1/2 inches; a sketch showing a pair of cupboard doors opened wide to expose a preliminary version of the small potting room that Bunny wished to have built into the wall: 6 by 8 1/8 inches; and four sketches of various sections of the trompe l’oeil decoration in which one can see the definitive result gradually taking shape. Two of the four sketches measure 8 3/4 by 16 5/8 inches; the other two measure 9 1/4 by 17 inches.

87. See Hammer, Fernand Renard (April 16–27, 1968); Victor T. Hammer, Fernand Renard:

Recent Paintings (New York, February 29–

March 11, 1972); Victor T. Hammer, Fernand

Renard: Recent Paintings (New York, April 29–

May 10, 1975), with introductions by

Victor T. Hammer.

88. Derry Moore, email to Nancy Collins,

May 8, 2019.

89. Oak Spring Garden Foundation archives.

90. Musée des beaux arts de Rennes, in Trompe l’Oeil anciens et modernes, 40.

91. Cf. Alain Corbin, Histoire du silence (Paris, 2016).

92. On the card is written: “This one is a fish trap – you catch a little fish, then you put it in this and leave it in the water tying it to some reeds, so the fish will be in the water till you are ready to take him home! ox Jackie”

93. Sandra Raphael, An Oak Spring Pomona: A

Selection of Rare Books on Fruit in the Oak Spring

Garden Library (Upperville, VA, 1990), 112–19.

94. Raphael, An Oak Spring Pomona, 247–50.

95. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 217–19.

96. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 267–91.

97. Tongiorgi Tomasi, An Oak Spring Flora, 172–75.

98. Cf. Sotheby’s Auction, 3:140.

99. Sotheby’s Auction, 3:sessions 3–5, lot number 1076.

100. 1578–81, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

101. Ca. 1597–1600, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca

Ambrosiana, Milan.

102. On Moillon and Chardin, cf. Faré and Faré, La vie silencieuse en France; on Garzoni, cf. Gerardo

Casale, Giovanna Garzoni “insigne miniatrice” 1600–1670 (Milan, 1991). See Jacopo da Empoli,

Cucina con frutta e verdura, 1625, Collezione

Francesco Molinari Pradelli Marano, Bologna; and Dispensa, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence.

103. Filippo Napoletano (see n. 67), Due cedri, 1618,

Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di

Firenze, Sezione Botanica.

104. Tony Willis, “Rachel Lambert Mellon:

Her Library and Outstanding Collection of Botanical Art,” in Arte botanica del terzo millennio / Botanical Art into the Third

Millennium, ed. Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi and

Alessandro Tosi (Pisa, 2013), 47. On Hodgkin, cf. Eliot Hodgkin, 1905–1987: Painter & Collector, with an introduction by Sir Brinsley Ford (London, 1990). 105. Ca. 1602, oil on canvas, San Diego Museum of Art.

106. Edouard Manet, Bunch of Asparagus, oil on canvas, 1880, Wallraf-Richartz-

Museum, Cologne.

107. 1655, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie der

Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna.

108. Many pieces from her collection of jewelry and other objects designed and realized by Schlumberger were donated by Mrs.

Mellon to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

109. As was mentioned earlier, Coorte also painted still lifes featuring bunches of asparagus or fruit (such as a bowl of strawberries).

110. Choix de coquillages, gouache and watercolor,

Musée du Louvre, Paris.