The 2016 Newman Lecture at Mannix College

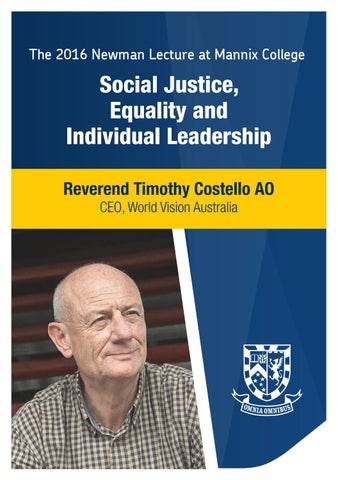

Social Justice, Equality and Individual Leadership Reverend Timothy Costello AO CEO, World Vision Australia

The 2016 Newman Lecture at Mannix College

Social Justice, Equality and Individual Leadership Reverend Timothy Costello AO CEO, World Vision Australia