POLICY HIGHLIGHTS Financing growth and turning data into business: Helping SMEs Scale Up OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship Co-funded by the European Commission

About the OECD

The OECD is a unique forum where governments work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co ordinate domestic and international policies.

About the Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities

The Centre helps local, regional and national governments unleash the potential of entrepreneurs and small and medium sized enterprises, promote inclusive and sustainable cities and regions, boost local job creation and implement sound tourism policies.

full book

The

is accessible at https://doi.org/10.1787/81c738f0 en

Highlights

Firms that scale up have long raised policy attention for their strong potential in terms of job creation, innovation, competitiveness and economic performance However, and despite an abundant academic literature, the conditions of SME growth remain overall poorly understood. As governments aim to build resilience and speed the recovery from the COVID 19 crisis as well as the transition towards more sustainable and inclusive growth, scalers are called to play a key role.

The potential of improved scale up policies is significant. For instance, while scalers represent only 13 15% of SMEs in Finland, Italy, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and Spain, they accounted for 47% to 69% of all new jobs generated by non micro SMEs between 2015 and 2017. In addition, most scalers maintain their new scale over time, and many succeed to grow again shortly after, signalling that during their transformation, they have gained capacity on a permanent basis, while some have even initiated a virtuous circle of changes.

Scalers are also much more diverse than commonly thought The typical scaler is neither a knowledge intensive nor a high

tech firm, nor a start up. In fact, most of them are mature firms operating in low tech sectors. In addition, they adopt a variety of trajectories in transition to, during and after, scaling up. There is therefore potential for achieving greater socio economic benefits through different types of firms, going beyond the segment of high tech start ups. This diversity in scale up profiles and trajectories demands a rethinking of scale up policies. Although the evidence is mixed, a (too) narrow focus on specific sectors, such as knowledge intensive firms or start ups, is likely to be suboptimal.

Effective policy design requires a better understanding of scalers’ transformation process and related scale up drivers. The identification of potential scalers (including the probability of sustaining new scale) is difficult to anticipate, as it reflects a number of factors, including not just broader economic framework conditions, quality of entrepreneurial ecosystems and the health of the economy, but also specific innovation, investment, and network expansion strategies of the firm (Figure below)

Click or tap here to enter text. Click or tap here to enter text.

SME performance and scaling up drivers

Scaling up drivers

Innovation

Network expansion

Highly interconnected and mutually reinforcing, these scaling up drivers are mobilised in different ways and at different times by different types of scalers who may operate in different contexts and market conditions. This makes it difficult to pick winners and turns policy design into a more complex endeavour than the prevailing vision suggests. Governments can indeed act across multiple policy domains with a superposition of policy systems. At the same time, this diversity also opens the policy toolkit, as intervention can range from targeted support to more structural measures, e.g. for building entrepreneurial

ecosystems or improving policy system governance

The present work aims to understand how OECD countries can better promote SME scale up (Box below) It highlights a large diversity in the mix of policy objectives, instruments, and governance arrangements across countries, with a view to informing the design of multidimensional scale up policies. In addition, the report takes a deep dive into two specific dimensions identified as relevant for scalers’ transformation process: improving SME access to scale up finance and improving SME data governance.

R&D, disruptive innovation Digital adoption Business development

Investment Human capital Physical capital

Intangible assets

Domestic market International trade Cooperation, partnerships Digital platforms

Unleashing SME Potential to Scale Up: a multi-year research project

The OECD project on Unleashing SME Potential to Scale Up is carried out with the support of the European Commission. Its pilot phase (2019 21) is articulated across two pillars:

• A measurement pillar to better understand the internal drivers and barriers to SME high growth, through empirical work based on business microdata, and

• A policy pillar to analyse national policy mixes and approaches to unleash the potential of scalers through a mapping of relevant initiatives and institutions across the 38 OECD countries.

Leveraging firm level data from five OECD pilot countries (Finland, Italy, Portugal, Slovak Republic and Spain), the measurement pillar aimed to capture the heterogeneity of scalers, the changes these firms undertake before, during, and after a high growth phase, as well as the sustainability of their new scale. The work assesses in an internationally comparable way the factors that accompany growth, i.e. the dimensions through which the firm reached new scales or growth milestones, taking into consideration its capacity to operate in a sustained manner at a larger scale.

To identify the features that distinguish scalers from other firms, the analysis compares them with their “peers”, i.e., firms in the same sector, founded around the same time and of similar size before the scaler enters its high growth phase. “Scalers” are identified through employment- or turnover based (high) growth. High growth enterprises are defined as firms with at least 10 employees that grow 10% per year on average in employment and/ or turnover over 3 years.

Findings of the measurement work that have informed the policy work were published in a summary report “Understanding Firm Growth. Helping SMEs scale up” (OECD, 2021[1]).

Source: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/sme scale up.htm

Scale up finance policies are defined here as public interventions to unleash finance for SME growth-related activities, i.e. those related to innovation, investment, or network expansion. Microdata analysis has revealed that scalers increase financial buffers before scaling up. In a context, where SME difficulties in accessing finance represent a well documented barrier to their

development, diversifying sources is likely to be key, as scalers’ financing needs vary depending on their profile and growth trajectory Policy initiatives can either be aimed at SMEs themselves (for unleashing internal resources, or addressing demand side barriers), or at the finance market and institutional actors (for external finance) (Figure below).

| 5 5

Key aspects of scale up finance policy

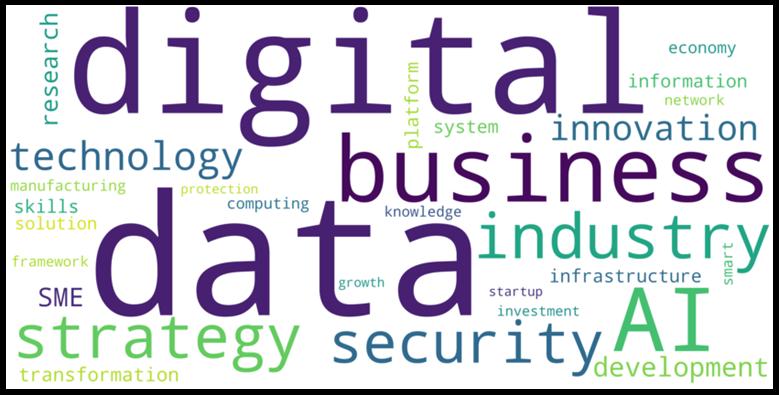

Note: Word cloud based on the description of the 709 national policy initiatives mapped in this area. Detailed information is available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship

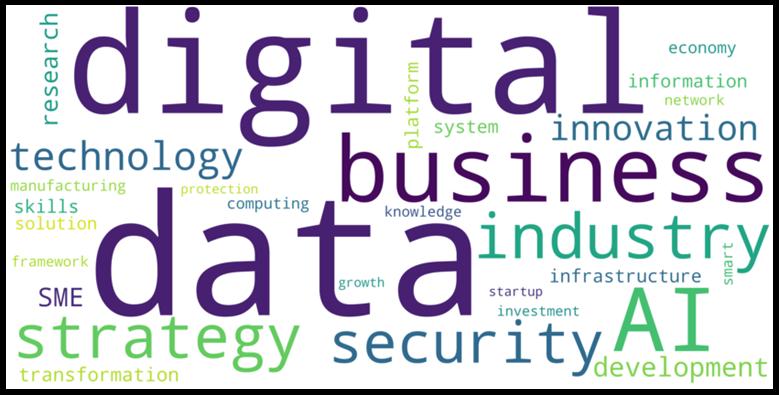

Policies in support of SME data governance are defined here as public interventions that can help SMEs turn data into value and grow. Microdata analysis has revealed that scalers are more digitalised, hence more data driven or likely to use data to scale up their business. In a context, where intangible assets and data have come to make up a significant part of a firm’s value, improved

data governance is emerging as a strategic issue for an increasing number of SMEs. Policy initiatives can be aimed at improving SME access to external data through an open and supportive data environment, or at encouraging a better exploitation and protection of data within the firm (figure below).

Key aspects of SME data governance policy

Note: Word cloud based on the description of the 487 national policy initiatives mapped in this area. Detailed information is available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship.

6

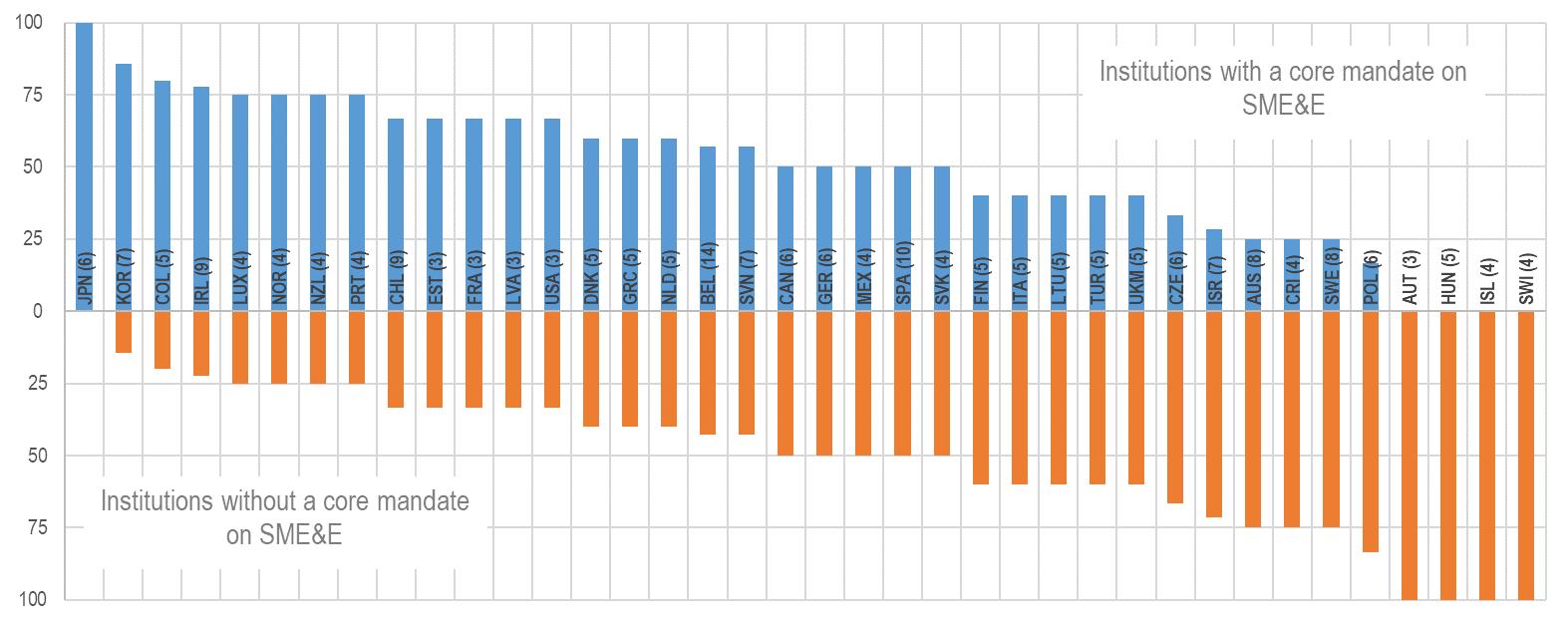

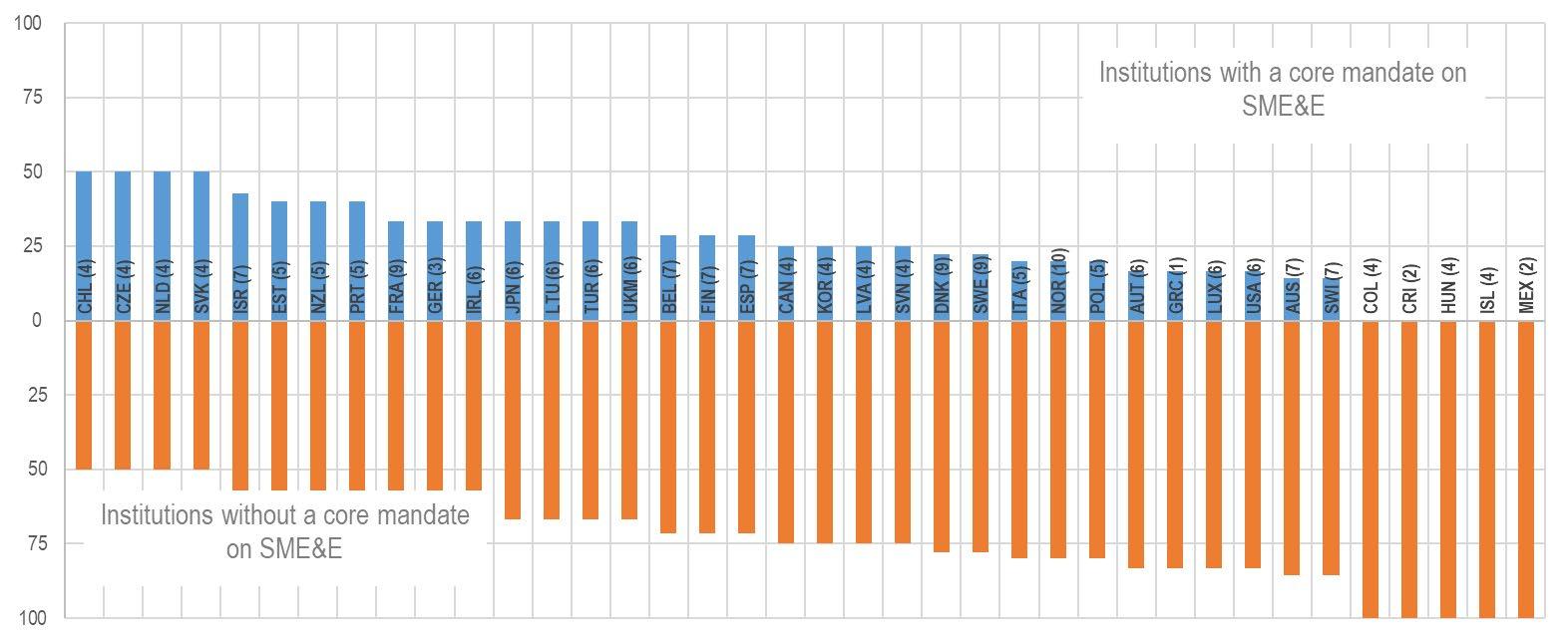

How much government attention goes to improving SME access to finance or data governance for scaling up? And in which form?

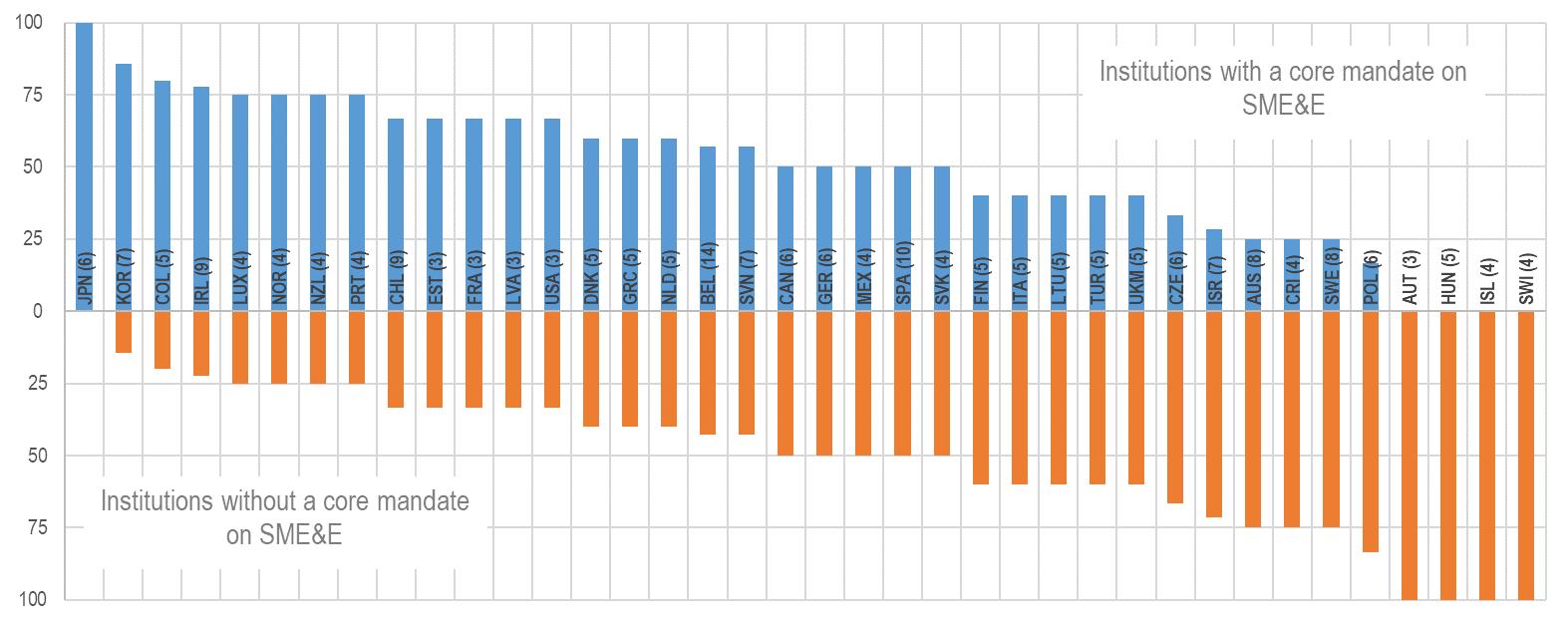

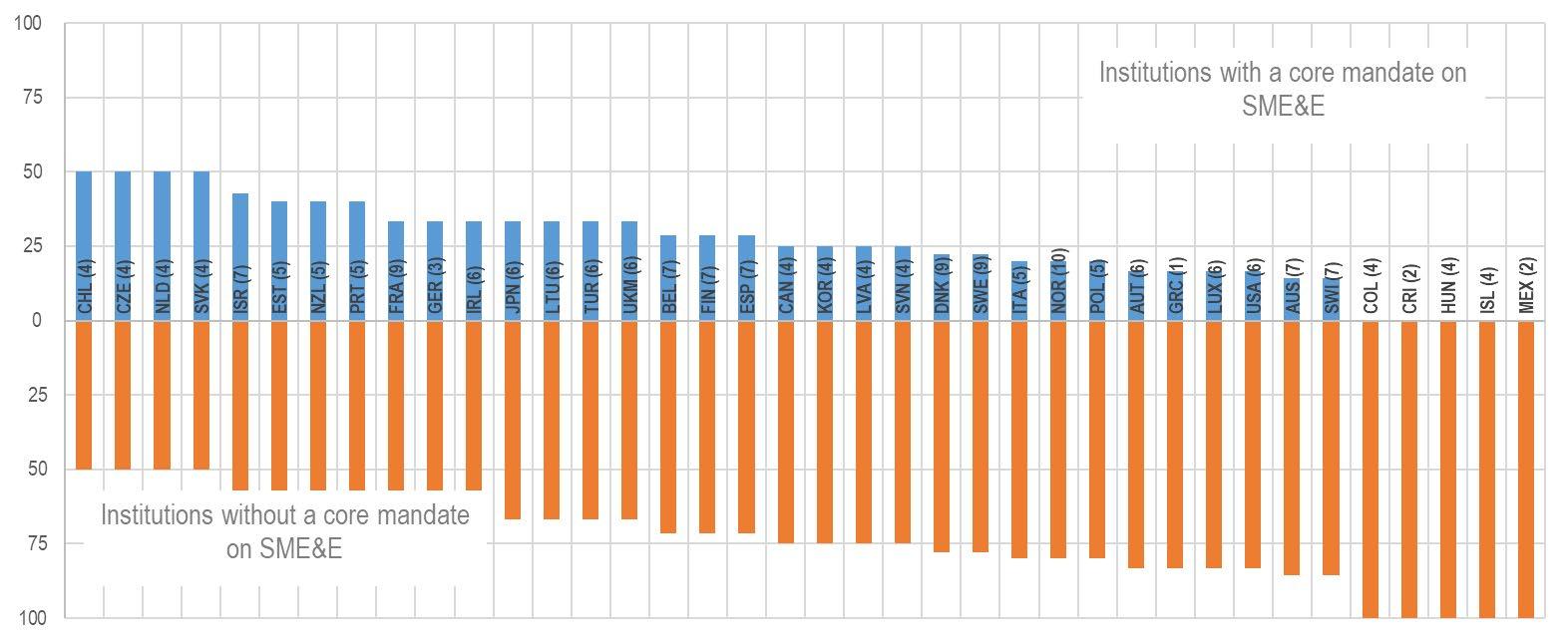

Based on an international mapping of 419 institutions across the OECD, the analysis shows that SME and entrepreneurship policy is not among the core mandates of many implementing institutions More specifically, the work identifies 210 government institutions involved in promoting growth finance for SMEs, and 209 institutions involved in improving SME data governance, of which only 50 are common to the two fields, and 54% and 26% of them

respectively have SMEs in their core mandate (Figures below). This calls for sound coordination across the board and for a further mainstreaming of SME growth considerations in both policy areas to better address the specific challenges faced by small firms This could be achieved through a strategic, structural, and whole of government approach to SME growth, and by embedding coordination mechanisms in policy design

Not all institutions promoting scale up finance are responsible for SME and entrepreneurship policy

Percentage of institutions with/without SME and entrepreneurship as a core mandate, in total (%)

Note: Experimental indicators based on unweighted count Numbers into brackets are the number of institutions mapped in each country. For small values (few observations), interpretation should be done with caution Detailed information is available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship

| 7

SMEs do not form part of the core mandate for most institutions overseeing data policies

Percentage of institutions with/ without SME and entrepreneurship as a core mandate, in total (%)

Note: Experimental indicators based on unweighted count. Numbers into brackets are the number of institutions mapped in each country. For small values (few observations), interpretation should be done with caution . Detailed information are available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship.

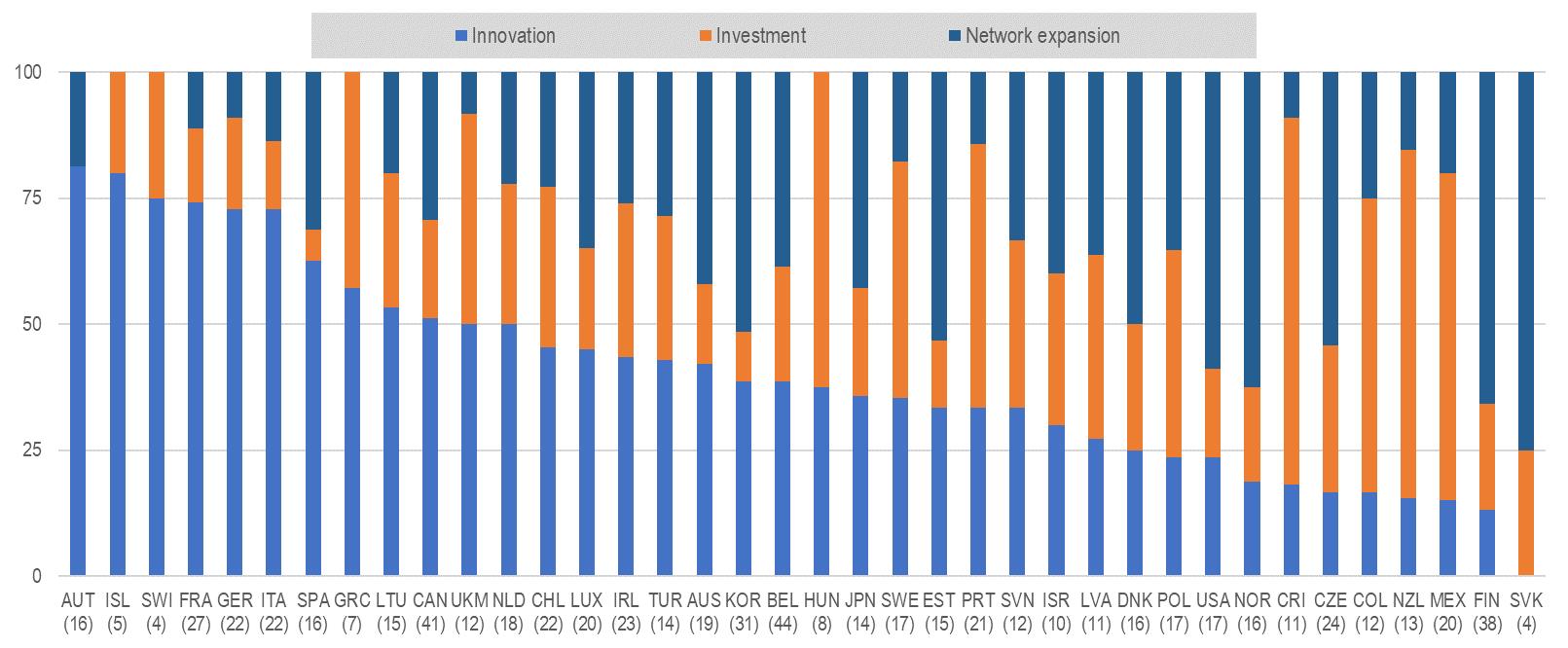

The policy mapping identifies 709 policies for strengthening SME access to scale up finance, and 487 policies for improving SME data governance, which reveal a number of differences across the two areas.

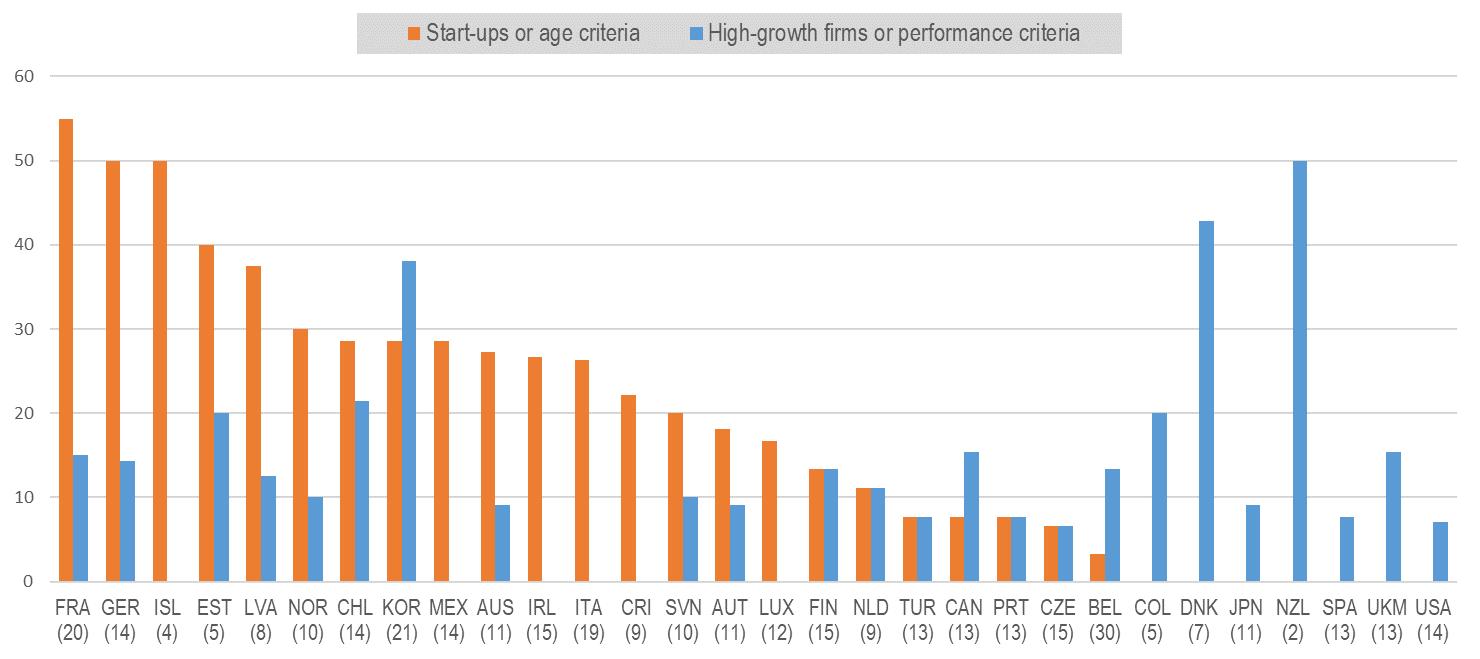

In the policy mix for SME growth finance, generic measures are the exception: 72.6% of all measures (18.7 per country on average) across OECD countries are targeted, in most cases at SMEs (38.6%), but also at certain sectors, technologies or places (15.2%). Efforts to target high potential firms (“winners”), and frequently decentralised arrangements for implementation, result in a multiplication of public support schemes and eligibility criteria, where (potential) scalers may struggle in identifying the most appropriate solution for their needs. Complementary outreach efforts, e.g. through one stop shops, could help SMEs in particular, to navigate this potentially more fragmented policy space.

By contrast, the SME data governance area (12.8 on average per country) is an emerging policy field, where efforts tend to focus on shaping the data policy system, resulting in more high level (and less numerous) measures, such as strategies and action plans. As a result, only 29% of data policy measures are SME targeted, with some data elements often weaved into broader SME digitalisation initiatives.

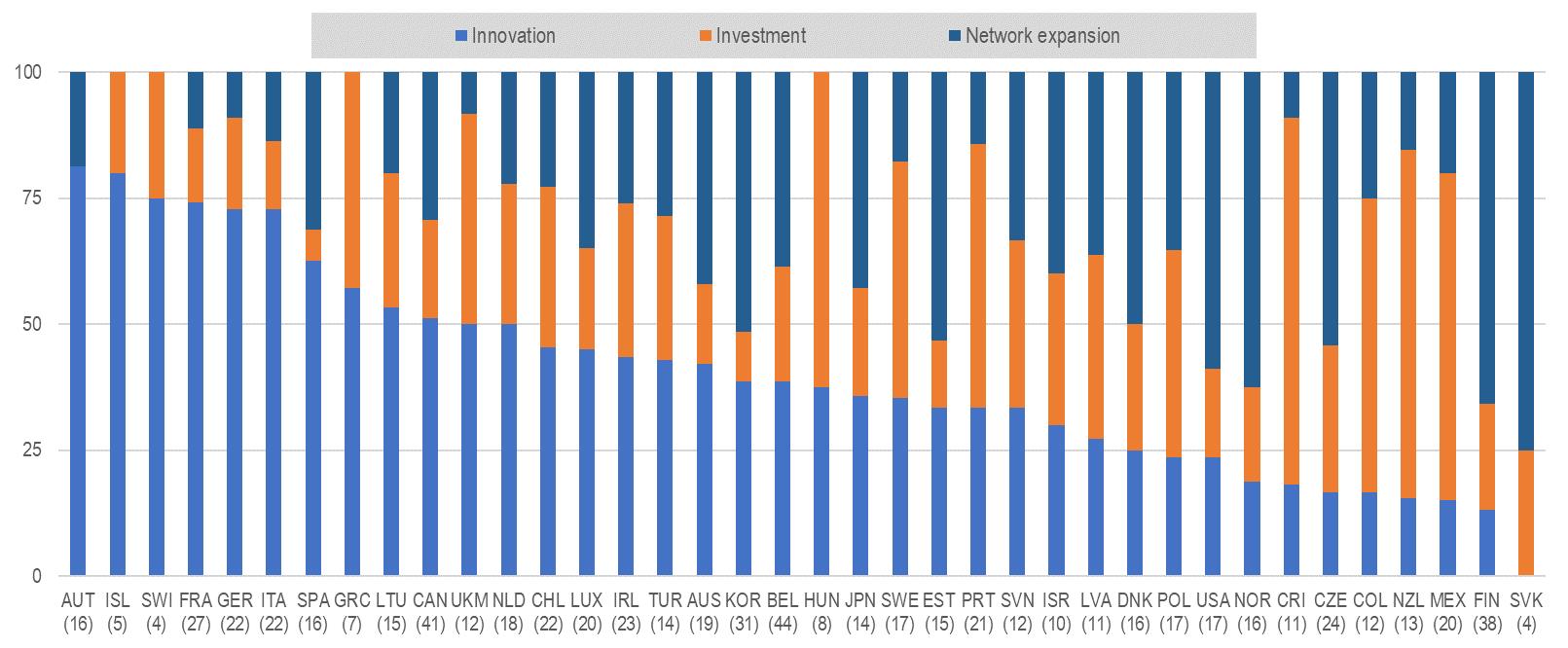

Scale up finance policy is more often oriented towards disruptive innovation and equity capital, with lesser emphasis on investment in skills or intangible assets (Figure below) In addition, the finance market plays a secondary role in national policy efforts, which rather remain focused on reducing the need and cost of external financing for SMEs through government support.

8

How far is the policy mix focused on -or targeted at- specific objectives or populations (especially SMEs or start- ups)?

Policy mixes for scale up finance are not geared towards the same drivers

Share of SME scale up finance policies, by scaling up drivers

Note: Experimental indicators based on unweighted count The analysis of network expansion does not cover indirect engagement in international trade (e.g. through supply chains, nor the use of digital platforms. For small values (few observations), interpretation should be done with caution. Detailed information are available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship

How country-specific are scale up policies in the two areas?

This overall picture hides large country differences within each domain, which can blur policy messages Canada (37), Korea (34), Finland (33), or France (32), have over 30 measures in place for financing SME growth, six to seven times as many as in the Slovak Republic and Switzerland (5). Over 75% of the measures taken in Austria, Iceland and Switzerland, aim to better finance SME innovation, while more than 60% of those taken in Costa Rica, Hungary, Mexico and

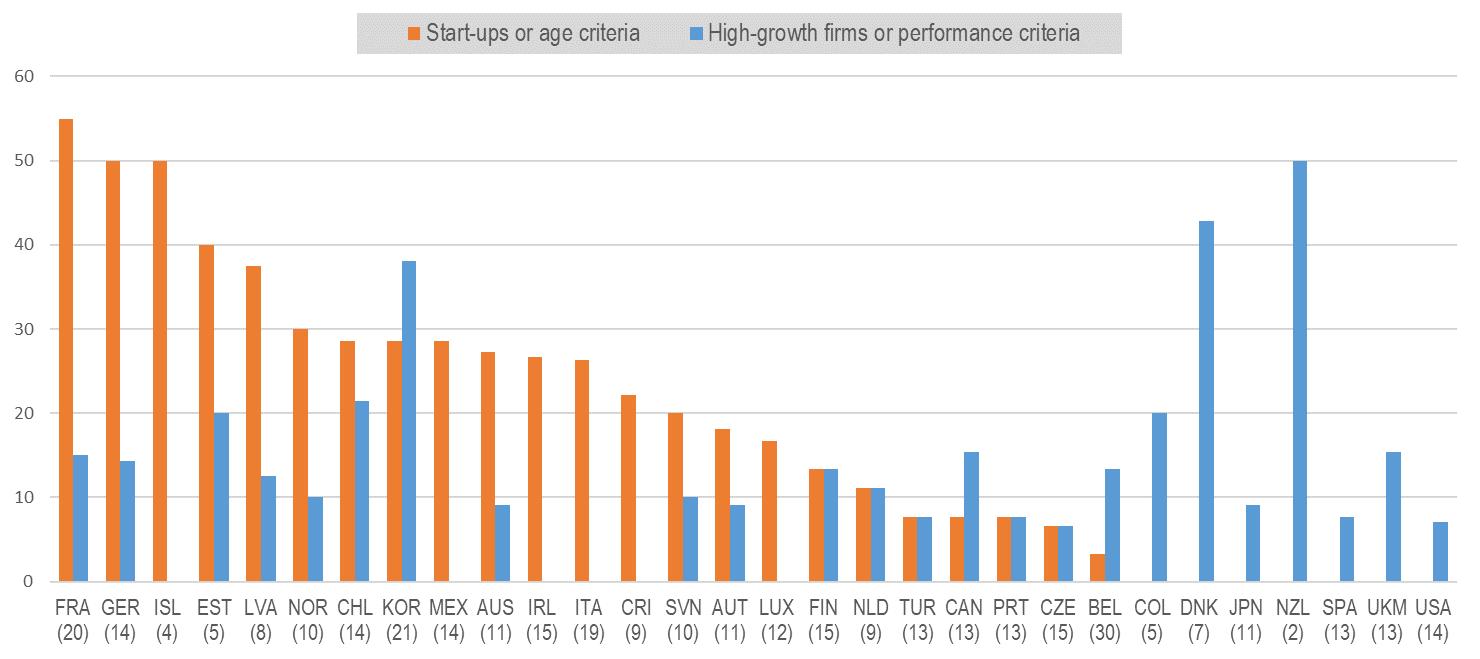

New Zealand aim to financing productive investments. While strong targeting is the most common approach for financing SME growth, not all countries are giving the same focus to start ups. France and Germany have over half of their population targeted initiatives designed with age criteria, whereas firm age is not considered in a number of other countries’ mix (Figure below)

9

For financing growth, some countries place a stronger focus on start-ups, but not all

Share of population targeted measures that are designed towards start ups and high growth firms

Note: Experimental indicators based on unweighted count. Numbers into brackets are the number of initiatives mapped in each country. SMEs with age criteria include young firms and start ups but incumbents as well. SMEs with performance criteria include high growth firms, scalers but also laggards For small values (few observations), interpretation should be done with caution Detailed information are available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship

To the same token, France and Hungary have 20 measures for improving SME data governance, compared to only 3 and 4 in Mexico and Iceland. Over 85% of the data policy mix in Austria, Denmark and the Slovak Republic aim to improve SME data culture and skills, compared to about 30% in Korea or Italy (Figure below).

These strong variations reflect different governance arrangements, strategies and national approaches to SME scale up, highlighting the need for further work to understand how governments effectively promote SME growth, and how these different approaches can link with SME performance and capacity to scale up.

For improving SME data governance, most countries place a focus on

two objectives

national data governance

share

initiatives

What else is needed to inform the design of scale up policies?

More evidence is needed to fully assess and inform effective scale up policy design, including on the efficiency of public intervention (e.g. through impact evaluation). Greater insights on actions taken by subnational governments could also provide an important complementary perspective, not least given their role in fostering local ecosystems

More evidence is also needed on other (firm led) drivers of SME scale up. Beyond financing and data governance aspects, further evidence is needed across a broader set of relevant policy domains, including e.g. SME network capacities (i.e. through supply chains, cooperation or digital platforms), especially in light of recent disruptions in international markets. In addition, better

evidence on investments in skills and related policies will be critical, not least with respect to emerging challenges and opportunities around the twin transition.

A rethinking of scale up policy will ultimately require broader measures and notions of scaling up, going beyond traditional economic performance indicators. The current focus on firms that scale up through turnover or employment may not fully capture the social and/or environmental benefits generated by a larger set of firms. As governments prioritise sustainable growth, appropriate consideration needs to be given to the broader socio economic gains that may be achieved if scale ups can help tackle climate change and other societal challenges.

11

awareness and skills, but not all Top

of

policies, as a

of all

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% SVK (6) DNK (13) CRI (5) FIN (10) TUR (17) ISL (4) POL (15) LVA (7) SVN (10) CHL (9) NLD (9) DEU (17) OECD (487) COL (17) LUX (9) CAN (6) IRL (17) NZL (10) KOR (13) LTU (10) Data culture and skills (awareness and training) Data use and valorisation (adoption of data analytics and technologies) Note: Experimental indicators based on unweighted count Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to one or several policy objectives at the same time. For small values (few observations), interpretation should be done with caution. Detailed information are available in the OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship

Policy messages of the pilot phase

There is a need to rethink scale up policies and open the policy toolkit:

1. SMEs that scale up bring a broad potential for job creation, innovation, and competitiveness, and can lay the economic foundations of greater resilience and sustainability

2. Scalers are not all those we think they are. Beyond the segment of knowledge intensive and high tech start ups, there is a long tail of scalers that are mature and low tech firms Moreover, most scalers sustain new scale over time, and many succeed to grow again in the next few years, signalling a durable transformation

3. The transformation of scalers is difficult to anticipate, as it reflects a diverse set of factors, including broader economic framework conditions, quality of entrepreneurial ecosystems and the health of the economy, but also specific innovation, investment, and network expansion strategies of the firm

4. The diversity in SME growth profiles and trajectories calls for scale up policies that are equally diverse. Scale up policies should also account for the fact that all scalers are not equal in terms of the socio economic benefits they bring, and there may be trade offs between the various transformations they go through.

Looking at OECD governments’ action in two relevant areas for scaling up:

5. Only 54% of government institutions involved in promoting growth finance for SMEs, and 26% of those aiming to improve SME data governance, have SMEs in their core mandate, and even fewer support both agendas This calls for better mainstreaming SME policy considerations across the board, and paying closer attention to policy coordination across policy systems and levels to support SME growth

6. The policy mix for SME growth finance displays a high degree of targeting, suggesting that complementary outreach efforts, e.g. through one stop shops, could help SMEs in particular, to navigate this potentially more fragmented policy space. In comparison, data governance is an emerging policy field where efforts focus on shaping the data policy system, with a strong prevalence of high level horizontal measures, such as strategies and action plans.

7. Across both policy domains, stronger policy attention is given to specific aspects, actors or drivers of SME growth that may leave blind spots in other areas.

• For financing SME growth, more attention goes to disruptive innovation and equity capital, and less to investment in skills or intangible assets. The role of the finance market could be further leverage to diversify sources and forms of scale up finance

• For improving data access and use, most efforts focus on building a data culture and related skills among SMEs, and less on developing SME friendly data infrastructures

8. There are large cross country variations in governance arrangements, strategies and national approaches to SMEs scaling up, which call for further knowledge sharing and mutual learning

9. More policy information, microdata and analytical work are needed, to understand how scale up policies shape and link with SME performance(s) and capacity to scale up.

12

https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/sme-scale-up.htm Co-funded by the European Commission