Efficiencies in Merger Control

Comments by John Kwoka

Northeastern University, Boston

OECD Roundtable

Paris 17 June 2025

Delegation Notes indicate broad agreement on some issues

• There is broad agreement on these propositions:

(1) Efficiencies play a role in mergers and in principle should be considered in merger evaluation

(2) Efficiencies consist of more than conventional cost savings. They also include

Improvements in quality and variety of products

Innovation efforts and methods ( R&D, exploiting complementarities)

Cost savings in production, distribution, transactions, finance, etc

(3) There are criteria for assessing efficiencies

Efficiencies must be inherent in (specific to) the merger

Must be verifiable by competition agency

Benefits must be at least in part passed on to consumers

Also, timely, likely, and sufficient in magnitude

Principles vs. practice: The paradox

• Despite this conviction that efficiencies are important, delegations commonly indicate that their agencies scarcely ever—perhaps never—find that efficiencies matter in actual merger analysis

• Or at least do not matter enough to reverse an agency determination of competitive problems with a specific merger

• Many examples are cited where claims of efficiencies are not accepted

• Most frequent reasons are verifiability and merger specificity

• This is the apparent paradox: Efficiencies are acknowledged as important in principle, even though they are not often found significant in practice

• Two explanations for this apparent paradox

• Theory is not as simple as often portrayed

• Empirical evidence cautions about actual effects

Theoretical explanation

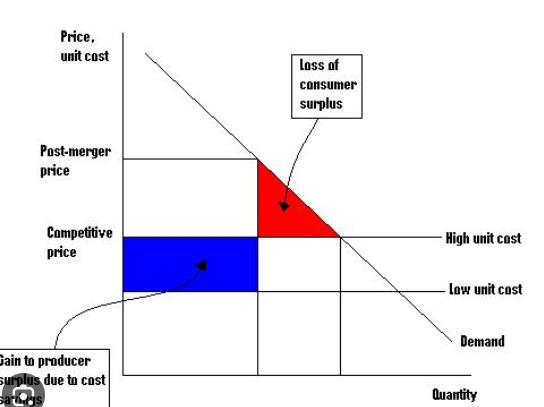

• Original theory due to Williamson implied the importance of efficiencies

• Merger both created market power but lowered cost

• Trade off between costs (red) and benefits (blue)

• Williamson concluded: “A merger which yields non-trivial real economics must…result in relatively large price increases for the net effects to be negative.”

• But Williamson called this particular demonstration a “naïve” model since it did not acknowledge “a variety of essential qualifications”

• He listed the following qualifications

• “Inference and enforcement expense

• Timing

• Incipiency

• Weighting

• Technological progress

• And the effects of monopoly power on managerial discretion”

• Williamson understood the abstract nature of his demonstration

• Explicitly stated that any of these can modify—possibly substantially--his “naïve” conclusion

• So theory does not so clearly favor efficiencies

Empirical explanation

• Empirical studies generally find little evidence of systematic efficiencies

• Rose and Sallett (2020) surveyed economic literature on efficiencies and concluded that:

• “a substantial body of work casts doubt on their presumptive existence and magnitude”

• Went on to observe that current policy has had an “overly-optimistic view of the existence of cognizable efficiencies” leading to acceptance of anticompetitive mergers

• My own meta-analysis (2015) of merger retrospectives focusing on cost savings concluded much the same

• Average cost efficiency netted out to zero

• So evidence, too, suggests little systematic efficiency benefit from merger

• Why, then, all the attention to efficiencies?

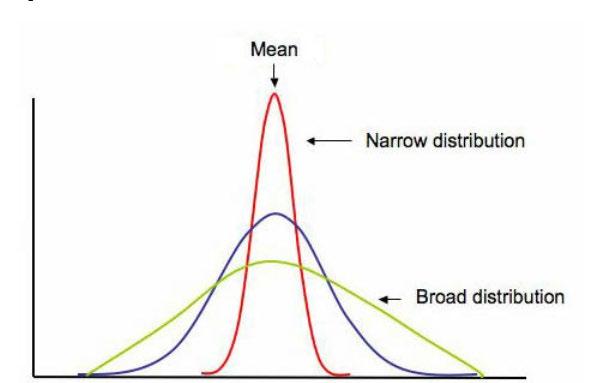

• Reason is variation—not the average--in outcomes

• On average, efficiencies do not result from mergers, so most claims should not be accepted

• But the significant variation in outcomes implies that there are some cases of substantial efficiencies, which policy seeks to identify

• Challenge for agencies is to identify unusually large and important efficiencies…

• BUT to avoid crediting others with efficiencies they will not achieve

• AND avoid having to evaluate many or most claims in order to identify very small fraction of meritorious cases

• To illustrate difficulties, early U.S. Merger Guidelines (1982) stated that guideline thresholds were written so as to allow for small routine efficiencies in most mergers

• Agencies said they would examine specific claims only in “extraordinary” cases

• But the “extraordinary” became routine as most merging parties claimed some efficiencies and agencies had to evaluate claims in most cases

• Later guidelines continued to seek—largely unsuccessfully-- methods to focus on cases with plausible efficiency claims