Belonging is not always bound to a place. It lives in the rituals, moments, and threads of kinship that shape our sense of home and define who we are. In the following pages, we reflect on the myriad ways, both subtle and grand, that belonging manifests in stories across Hawai‘i and beyond.

Along the Hāmākua Coast of Hawai‘i Island, one feels a sense of belonging woven through the cliffs, waterfalls, and old sugarcane paths, where the echoes of generations past continue to anchor those who pass through today. On O‘ahu, the public art project Wahi Pana: Storied Places celebrates these stories, mapping cultural and spiritual sites that carry collective memory and offering residents and visitors a way to connect with the deeper history of this place. And in Honolulu’s intimate supper clubs, belonging takes shape at the table, where strangers become companions over carefully curated meals and conversation develops into a ritual.

In Taiwan’s quieter towns, a writer discovers belonging in unexpected moments: along the waves of the island’s eastern coast, among the vibrant markets of Tainan, in the enduring traditions that anchor communities amid constant change. And in Chiba, Japan, Taisuke Kawai’s high-end golf club, The Saintnine Tokyo, invites members to cultivate kinship through a shared appreciation of refinement and sport.

We hope these stories illuminate the infinite forms in which belonging unfolds in your own lives, revealing the connections that continue to shape, sustain, and guide us as we make our way through the world.

“居場所”は、必ずしも場所とはかぎりません。自分が何者かを示 す日々の習慣やちょっとしたひととき、そして人やものとのつな がりのなかにも、わたしたちの居場所はあるのです。本号では、ハ ワイだけではなく、世界のあらゆる場所で、ときにはささやかに、 ときには大げさに、居場所が顔をのぞかせる物語の数々をご紹 介します。

ハワイ島ハーマークアの海岸線では、断崖や滝、そして昔日の サトウキビ畑の小道に、世代を超えて受け継がれた記憶が今も 息づき、訪れる人々の胸に訴えかけます。オアフ島では、公共の 場所に出現したアートプロジェクト『ワヒ・パナ 物語を伝える場 所』が、文化的、あるいは精神的に人々の心に刻まれた場所を地 図でたどり、その地にまつわる深い歴史をハワイの住民と観光客 に伝えています。ホノルルの小さなサパークラブでは、見知らぬ人 同士が同じテーブルを囲み、丹精込めてつくられた食事と会話を 楽しむうちに友情が芽生え、新たな居場所を生み出しています。

台湾のどちらかというと地味な町では、思いがけない場面で“ 居場所”を見つけました。島の東の海辺や活気あふれる台南の市 場、そして絶えず変化を続ける時代に人々を結ぶ伝統のなかに。 日本の千葉では、川合泰祐さんが手がけるハイエンドなゴルフ場 〈ザセントナイン東京〉が、ワンクラス上のゴルフを楽しむ人々の 新たなつながりを育んでいます。

暮らしのなかに無限のかたちで息づく“居場所”をご紹介するこ とで、世界各地で人々をつなぎ、支え、導いている絆が浮き彫り になることを願っています。

CEO & PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

PARTNER & GM, HAWAI‘I

Joe V. Bock

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Lauren McNally

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Matthew Dekneef

MANAGING EDITOR

Eunica Escalante

SENIOR PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

MANAGING DESIGNER

Taylor Niimoto

DESIGNER

Eleazar Herradura

TRANSLATIONS

Akiko Shima

Eri Toyama

Stray Moon LLC

CREATIVE SERVICES

Gerard Elmore

VP Film

Kristine Pontecha

Client Services Director

Kaitlyn Ledzian

Studio Director/Producer

Arriana Veloso

Digital Production Designer

OPERATIONS

Gary Payne

Accounts Receivable

Sabrine Rivera

Operations Director

Sheri Salmon

Traffic Manager

Jessica Lunasco

Operations Manager

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

VP Sales

Claudia Silver VP Global Partnerships

Alejandro Moxey

Head of Partnerships, Hawai‘i

Simone Perez Advertising Director

Rachel Lee

Account Executive

Kylie Wong

Operations & Sales Assistant

場所に耳を澄ませて ビジネス

プレースタイルの新たな基準

時を超えて息づくハワイ建築 86

カヴァブーム到来 デザイン

潮の満ち引き エスケープ 100 ハーマークアに今もあるもの 110 台北のその先 食 128 ダイニング・イン

表紙

川合泰祐さん・起業家、千葉県 の高級ゴルフクラブ「ザ セイン トナイン 東京」にて 写真:リサ・ナイト

流れに逆らって

Under construction at 888 Ala Moana, Ālia rises along Honolulu’s shoreline, offering sweeping ocean views, lush terraces, and 1-, 2-, and 3-bedroom residences inspired by Hawai‘i’s beauty and designed to deliver an unparalleled living experience.

Resort-style amenities, open-air gathering spaces, and landscaped gardens are thoughtfully designed to invite relaxation, encourage connection, and enrich daily life.

that amplify

the soul of the city

Images by John Hook, Chris Rohrer, and courtesy of the City and Council of Honolulu

写真

Through Hawaiian storytelling, an islandwide art initiative invites us to rethink our connection to O‘ahu’s storied spaces.

ハワイの物語文化を軸に島全体に繰り広げられる芸術作品が オアフの地とのつながりを呼び覚ます

Translation by Mutsumi Matsunobu

翻訳 = 松延むつみ

On O‘ahu, as everywhere else on the archipelago, every place holds a story—ancestral tales carried in the earth, the sea, and the spaces where people gather. It is these stories that are at the heart of Wahi Pana: Storied Places, a public art project presented by the Honolulu Mayor’s Office of Culture and the Arts (MOCA). Inviting communities to step into the layers of history and meaning woven through the island’s landscape, the project situates new contemporary works by Native Hawaiian artists in wahi pana (legendary places) across the island, from Lē‘ahi (Diamond Head) to Hale‘iwa Beach Park.

ハワイ諸島のほかの島々と同じように、オアフ島の大地にも海にも、人々 が集う場所にも、祖先から連綿と受け継がれてきた物語が宿っている。ホ ノルル市文化芸術局(MOCA)が主催する公共芸術プロジェクト「ワヒ・ パナ:ストーリード・プレイス(Wahi Pana: Storied Places)」は、こうした 土地の物語をたどる。このプロジェクトは、島の風景に織り重なる歴史や その意義をより深めるために、レアヒ(ダイヤモンドヘッド)からハレイワ・ ビーチパークに至るまでのオアフ島内の各地域に呼びかけ、島中のワヒ・ パナ(伝説の地)に、ハワイ先住民の血を引く作家による新しい現代アート 作品を設置するという試みである。

The multi-phase project, launched in 2025 and on view through 2028, marks a new kind of public art practice for Honolulu. From the beginning, curators Marion Cadora, project lead at the Mayor’s Office of Culture and the Arts, and Donnie Cervantes of Aupuni Space in Kaka‘ako and Pu‘uhonua Society, approached the project as a shift away from the complicated government procurement processes that typically saddle public art. With private funding from the Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Public Art Challenge came the freedom to look further and deeper into the creative community, to find artists at all stages of their careers who can respond uniquely and diversely to the stories of these places. It’s a subtle but profound breaking down of walls: public art as a means for voices that usually live outside the official narrative to step in and be heard.

At the heart of Wahi Pana is collaboration that feels less like a checklist and more like a conversation between artist, place, and story. “I would say [the mo‘olelo are] kind of a place of departure for the work, and it has become really individual to each site and each artist,” Cervantes says. These pieces, then, are not mere translations of old stories, but an invitation to question what we think we know about familiar places such as Koko Crater Botanical Garden or Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve. Whether you grew up here or are merely passing through, the project nudges you to consider your own place in the island’s layered histories.

The artists themselves reflect this layered approach. From established artists to emerging talents stepping into larger, community-rooted work for the first time, the resulting cohort forms a mosaic of perspectives and mediums—poetry, film, the abstract, the concrete—that connect us more deeply to the land.

One such voice is Hawaiian artist Cory Kamehanaokalā Holt Taum, who brings to life the epic journey of Hi‘iakaikapoliopele through his vivid bus wrap project, Ka Pā‘ū Ehuehu o Hi‘iaka (The Animated Skirt of Hi‘iaka). This striking graphic vinyl wrap, installed on three city buses across O‘ahu, depicts flowing pā‘ū patterns that trace Hi‘iaka’s path across the island, mirroring TheBus routes. Taum’s work draws on the mo‘olelo of Hi‘iaka, a complex deity and protector, who embarks on a journey to retrieve Pele’s lover, Lohi‘au. The skirt worn by Hi‘iaka embodies mana (spiritual power) bestowed through her ancestors and the hand of Pele, which allows Hi‘iaka to both take and give life, reflecting a balance of destruction and regeneration, vitality, and death.

Taum’s artwork invites an estimated 45,000 daily bus riders to engage with this mo‘olelo through accessible technology. Passengers can scan QR codes to hear kau (poetic chants), mele (songs), and oli (chants) that honor the landscapes and ancestors Hi‘iaka encounters on her journey.

この多段階型プロジェクトの展示は、2025年に始まり2028年まで続 き、ホノルルにおける新たな公共芸術活動のあり方を提示する。キュレー ターを務めるのは、ホノルル市文化芸術局のプロジェクト責任者である マリオン・カドラさんとカカアコのアウプニ・スペースおよびプウホヌア・ソ サエティのドニー・セルバンテスさんだ。ふたりは当初から、公共芸術の導 入につきものの煩雑な行政手続きから脱却すべく、このプロジェクトに取 り組んだ。慈善財団「ブルームバーグ・フィランソロピーズ」のパブリック・ アート・チャレンジによる民間助成金を得たことで、ホノルルの芸術コミュ ニティにより幅広くまた奥深く目を向けることが可能になった。アーティス トは、キャリアの長さや実績に関わらず、これらの場所にまつわる物語を 独創的かつ多様な形で表現できるようになった。少しずつではあるが、確 実に壁は取り壊されてきている。公的な語りの外に置かれがちな声が、公 共芸術という方法で広く世間に届けられるようになったのだ。 ワヒ・パナの核となるのは、チェックリストのような決まりきったことで はなく、アーティストと土地そして物語の間に生まれる対話のようなコラ ボレーションだ。「モオレロ(伝承)は、作品づくりの出発点のようなもので す。そこから場所やアーティストによって、まったく異なった作品へと展開 していきました」とセルバンテスさんは語る。こうして生まれた作品は、古 くから伝わる物語の単なる現代版ではない。ココクレーター植物園やハ ナウマ湾自然保護区といった馴染みのある場所について「私たちはその場 所の意味を本当に知っているのだろうか?」という問いを投げかけてくる。 このプロジェクトは、ここで育った人にも、旅の途中にこの島を訪れただけ の人にも、幾重にも重なるこの島の歴史に向き合い、自分自身の居場所を 見つめ直すきっかけを与えてくれる。

参加アーティストの顔ぶれにも、このプロジェクトの重層的なアプロー チが反映されている。すでに確固たる評価を得ているアーティストから、 今回初めて地域に根ざした大きな作品に挑む新進気鋭のアーティストま で、多彩な才能が集結する。詩や映像、抽象表現から具象表現まで、多様 な視点と表現媒体を駆使するアーティストたちがモザイクのように集ま り、観るものにより深くこの土地へのつながりを感じさせる。

ハワイアンのアーティスト、コーリー・カメハナオカラ・ホルト・タウムさ んもそういった表現者の一人だ。タウムさんは、色鮮やかなバスラッピン グのプロジェクト「カ・パウ・エフエフ・オ・ヒイアカ(動きのあるヒイアカの スカート)」によって、ヒイアカイカポリオペレ(火の女神ペレのいちばん下 の妹)の壮大な旅路を現代に甦らせた。オアフ島内を走る3台の市バスに 施された印象的なグラフィックのビニール製ラッピングは、流れるような パウ(スカート)の模様で、島を横断したヒイアカの軌跡を表現しており、 市バスの路線とも呼応するように描かれている。タウムさんの作品は、愛 と守護を司るヒイアカが、姉ペレの恋人であるロヒアウを迎えに行く旅の 伝承に基づいいるのだ。その時、ヒイアカが身につけていたスカートは、 先祖とペレから授けられたマナ(霊的な力)を宿していたといわれている。 ヒイアカはこの力により、破壊と再生、生と死のバランスを司る生殺与奪 を象徴する神聖な存在となる。

Ualani Davis is a fourth-generation Kaimukī resident, Native Hawaiian, and art educator whose cyanotype installation at Koko Crater Botanical Garden reimagines the garden not just as a landscape of biodiversity, but as a site of resistance and reclamation. Drawing on Queen Lili‘uokalani’s song “Ku‘u Pua I Paoakalani” and the garden Uluhaimalama that was planted as a symbol of hope following the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Davis uses native plants like koa, kukui, and ‘ihi‘ihilauākea to commemorate three historic days of Hawaiian protest and celebration.

“I loved this idea that a garden could be a place of resistance,” Davis says. “That nurturing can be a form of resistance, and there are remnants of our ancestors’ resilience in the land even today.”

This was Davis’ first public art piece, and the experience taught her a great deal about the collaborative nature of such projects. She gained a deeper appreciation for the many people involved, and the dozens of hands, hearts, and minds that contribute to the public art seen throughout the city every day. Working with a skilled and supportive team revealed just how much effort goes into bringing these artworks to life.

“I hope it’s a piece that makes people curious and ask questions,” she says. “If a few more people learn the place names of the area, or look up the mo‘olelo of Kohelepelepe or Uluhaimalama, or even just listen to “Ku‘u Pua I Paoakalani”—I love the George Helm version—then I think it’s successful.”

In a collaboration between Hawaiian wood carver Jordan Souza and sculptor Amber Khan, an installation at Hale‘iwa Beach Park features a series of carved wooden forms inspired by the story of Laniwahine, the mo‘o (lizard) water guardian of the sand-dune ponds Loko Ea and Uko‘a. The sculptures will be placed on the old

タウムさんの作品は、1日あたり推定4万5000人のバス利用者に対し て、アクセスが簡単なテクノロジーを使い、この伝承との出会いを届けて いる。QRコードをスキャンすると、ヒイアカが旅の途中で出会った風景や 祖先を称えるカウ(詩的な詠唱)やメレ(歌)そしてオリ(詠唱)を聞くこと ができる。

ウアウラニ・デイビスさんは、4代に渡りカイムキに住むハワイ先住民 で、美術教師でもある。ココ・クレーター植物園にインスタレーションされ た彼女の青写真作品は、この庭園を豊かな生物多様性にあふれた風景と してだけでなく、抵抗と再生の土地として捉え直している。リリウオカラニ 女王の歌「 クウ・プア・イ・パオアカラニ(パオアカラニに咲く私の花)」、そ して1893年のハワイ王国転覆後に希望の象徴として造園されたウルハ イマラマ庭園に着想を得て、デイビスさんは、コアやククイそしてイヒイヒ ラウアケアなどの在来植物を用い、ハワイの歴史に刻まれた抗議と祝福の 3日間を偲んでいる。

「庭園が抵抗の場になる、という発想に心を奪われました」とデイビス さんは語る。「育むという行為そのものが抵抗のひとつの形となりえるの です。そして、今もなお、この土地には、祖先の強靭な力の名残が息づいて います」

この作品は、デイビスさんにとって初の公共芸術作品となった。そして、 制作の過程で、彼女は公共芸術のプロジェクトにおける共同制作の本質 について多くのことを学んだ。ふだん街中で目にする公共芸術には、多く の人々の存在と手や心、そして英知が注がれていることを知り、深い感謝 の気持ちを抱くようになった。経験豊かで支え合えるチームと共に制作を 進めるなか、デイビスさんはこれらの芸術作品に命を吹き込むためにどれ ほどの努力が注がれているのかを実感したのだ。

「この作品が、見る人の心に好奇心を芽生えさせ、何かしらの疑問を 抱いてくれることを願っています」とデイビスさんは語る。「たとえば、この 地域の地名について学んだり、コヘレペレペ(ココ・クレーター)やウルハ イマラマ庭園の伝承を調べたり。あるいは、私はジョージ・ヘルム版が好 きなのですが、『クウ・プア・イ・パオアカラニ』の曲を聴いてみようという人 が少しでも増えれば、この作品は成功だったのだと思います」 ハレイワ・ビーチパークにインスタレーションされた作品は、ハワイアン の木彫り職人ジョーダン・ソウザさんと彫刻家アンバー・カーンさんのコ ラボレーションによるもの。砂の丘に造られたロコ・エア養魚池とウコア 養魚池の水を守護するモオ(トカゲ)の姿をした半神ラニワヒネの物語に 着想を得た、一連の木彫りのフォルムで構成されている。公園の小道に並 ぶ古い柱の上に設置されたこれらの彫刻は、忘れられつつあった建造物 に新たな命と意義をもたらしている。

カーンさんにこの物語を紹介したのは、文化アドバイザーのペイジ・オ カムラさんだった。繰り返される対話やワイアルアで過ごす時間、そして自 身のルーツを考察するうち、この物語に対するカーンさんの解釈は少しず つ深まった。この伝承は「いくつもの時間軸が同時進行する多次元的な場 所」を映し出していると、カーンさんは説明する。

作品制作を進めながら、カーンさんは地元のさまざまな団体と会合を 重ね、物語と深く向き合い、そのなかで浮かび上がってきた数々の問いや それに対する回答を探求していた。この伝承を彫刻で表現するのは至難

pillars lining the park’s pathway, bringing new life and meaning to these somewhat neglected structures. Khan’s introduction to the story came through cultural advisor Paige Okamura, but her interpretation has grown through ongoing conversations, time spent in Waialua, and reflections on her own identity. She describes the mo‘olelo as revealing “a multidimensional place that carries innumerable timelines occurring concurrently.”

Throughout the process, Khan met with community groups to dive further into the questions—and answers— that arose as she sat more deeply with the story. Portraying the mo‘olelo in sculptural form presented challenges: How do you illustrate a shapeshifter? What does a wahi pana really carry?

“I’ve had to unlearn a lot,” she says. “I find myself holding space for a more sustainable and dynamic kind of energy, one that cultivates mental astuteness and a grounded awareness of this place.”

For Khan, the carving process itself was a kind of storytelling. “As we carve, we reveal something in the wood that was already there—something that just needed an intermediary to bring it out,” she says. “The story of Hale‘iwa Beach Park and Laniwahine illuminates just one layer of the many roots and realities of this space.”

Rooted in city parks, botanical gardens, and open spaces, Wahi Pana doesn’t just decorate the land—it stirs it. Ultimately, the project is more than a series of installations. While the artworks themselves are temporary, the intention is lasting: to open portals into the living mo‘olelo embedded in the island’s landscapes. In a world full of noise, Wahi Pana asks us to listen carefully. Because here, stories live in the land. And when we open ourselves to them, the land becomes a storyteller too.

の業だ。自由に姿を変える存在をどう表現するのか?ワヒ・パナ(伝説の 地)が本当に伝えたいことはなんだろう? カーンさんにとって、彫刻のプロセスそのものが物語を紡ぐ行為だった。 「彫っていくうちに、はじめから木のなかに宿っていたなにかが姿を現し てきました。それを引き出す媒介者が私だったのです」と彼女は語る。「ハ レイワ・ビーチパークとラニワヒネにまつわる物語は、この場所に幾重にも 重なる歴史や現実のほんの一層を照らし出しているに過ぎないのです」 市の公園や植物園そしてさまざまなオープンスペースで展開される「ワ ヒ・パナ」は、ただ景観を飾り立てるものではなく、大地を揺り動かすもの だ。つまりは、一連のインスタレーション以上の意味があるのだ。たしか に作品の展示自体は一時的なものだが、そこに込められた意図は永続的 で、島の風景に宿る生きた伝承への扉を開くきっかけとなる。「ワヒ・パナ」 は、騒がしさに満ちたこの世界で、静かに耳を澄ますことを促す。なぜな ら、この土地には物語が息づいているから。そして、私たちが心を開いたと き、気づくのだ。この島こそが語り部なのだと。

In Chiba, Taisuke Kawai has built an elite golf club that is anything but par for the course.

千葉で川合泰祐さんが手がける唯一無二のエリート·ゴルフクラブ

Translation by Akiko Mori Ching

翻訳 = チング毛利明子

There are certain luxuries that are out of reach even for the most lavish of purses. Consider, if you will, the Richard Mille watch. Since debuting the RM 001 Tourbillon in 2001, Richard Mille has become a coveted brand in the world of haute horlogerie, surpassing older, more established watchmakers that once defined the industry. Still, Richard Mille produces only about 5,300 pieces every year. Securing one is no small affair. And procuring the latest styles, for which the waitlists are infamously long, necessitates entry into a select circle of well-placed patrons. In the world of Richard Mille, there is no buying your way in. Rather, you must know someone. Or know someone who knows someone. Or become the person worthy of being known.

どれほど贅沢を極めても、簡単には手に入らない究極のラグジュアリーが ある。たとえば、リシャール·ミルの腕時計。2001年に最初のモデル『RM 001トゥールビヨン』を発表以来、リシャール·ミルは高級時計界の頂点に 名を連ね、かつて業界を牽引してきた長い伝統を誇る名門ブランドをも凌 ぐ人気を博してきた。とはいえ、年間生産数はわずか約5,300本に過ぎ ず、手に入れることは至難の技だ。なかでも最新モデルを入手するには、 なかなか順番が回ってこないことで知られる長いウェイティングリストに 名を連ねたのち、ごく限られた選ばれし顧客層の一員として迎え入れら れる必要があるのだ。リシャール·ミルの世界では、どんなに資産があって も、それだけでは扉は開かれない。「誰かを知っていること」あるいは「誰か を知る誰かを知っていること」、もしくは自らが「知るに値する人物になる こと」が求められるのだ。

Taisuke Kawai understands the value of prestige. Raised in the milieu of Japan’s elite set, he’s well-versed in the nuances of exclusivity, of true refinement, of the things in this world that money cannot buy. It was with this in mind that Kawai unveiled The Saintnine Tokyo in 2023, a sleek, members-only golf club that has brought a new shine to the country’s golfing scene. In the quiet satoyama landscape of Chiba Prefecture, an hour’s drive over the bay east of Tokyo, Saintnine stands as the sport’s shining city upon a hill.

“I want to change everything,” Kawai said one July evening over Zoom. “I want to create a new luxury prestige style of golf club.” It’s an ambitious goal, given the state of the sport in Japan today. Gone are the days of settai golf, when the fairway doubled as the boardroom and deals were sealed with handshakes out on the green. The approximately 2,100 private golf courses that mushroomed across the country in the ’80s and early ’90s have struggled to maintain their membership as baby boomers, the sport’s largest demographic, age out. As a result, the country’s once-vibrant golf culture appears to have lost its luster. It is from this climate that Kawai has dedicated himself to rekindling the country’s love affair with hitting the links. And there seems to be no man better suited for the task.

Born into a family of entrepreneurs, Kawai inherited a keen business instinct. “[My father] would always ask me, ‘Hey Tai, what do you think this store sells in a day? Which product is the most selling product here?’” he recalls of the impromptu economics lessons he’d often receive on trips to the grocery store in childhood. And in a culture where many stay close to home for university, Kawai’s decision to study in the United States revealed a maverick spirit, perhaps the influence of his grandfather, among the first Japanese businessmen to forge post-World War II ties with Americans.

In 2007, just a year after graduating from Montana State University, Kawai founded his first company, Mobercial, a marketing agency. That same year, Apple launched the iPhone, the large LCD screen forever changing how we consume content. Foreseeing a market shift, Kawai structured Mobercial to specialize in digital video advertisements, an approach that was perfectly suited to the rise of the smartphone era. After selling the company in 2019 to a major Japanese advertising firm, Kawai went on to build a diverse portfolio of lifestyle businesses, including premium tequila, French luxury caviar, and Champagne.

One evening over drinks, a longtime friend casually raised the prospect of opening a golf club in Japan. The friend, a South Korean unfamiliar with the Japanese golf industry, began grilling Kawai for insights. “I was talking to him about all my ideas,” Kawai says. “At the end, he was like, ‘Tai, why don’t we do this together?’” At first, Kawai

川合泰祐さんは、「格式」という価値をよく知っている。日本のエリート 層の中で育った彼は、選ばれし世界の機微や、本物の洗練、そして金銭で は決して手に入らないものを肌で知っているのだ。そうした価値観を体現 するように、川合さんは2023年に「ザ・セイントナイン・東京」を立ち上げ た。洗練を極めた会員制ゴルフクラブは、日本のゴルフ界に新たな輝きを もたらした。東京湾を越えて東へ車で1時間。千葉県の静かな里山に広が るセイントナインは、まるでゴルフ界の丘の上の輝ける都市であるかのよ うに、特別な光を放っている。

「すべてを変えたいのです」と、川合さんは7月のある夜、Zoom越しに 語った。「新しい格式のあるゴルフクラブをつくりたいのです」。現在の日 本のゴルフ界を取り巻く状況を考えると、それは極めて野心的な目標であ る。かつてのように、フェアウェイがそのまま会議室となり、商談はグリー ン上での握手とともに契約を交わしていた接待ゴルフの時代は過ぎ去っ た。1980年代から90年代初頭にかけて全国に広がった約2,100か所も の会員制ゴルフ場は、ゴルフの中心層である団塊世代の高齢化にともな い、会員の維持に苦戦を強いられている。その結果、かつて活気に満ちてい た日本のゴルフ文化は、次第にその輝きを失いつつあるという。このような 状況の中で、川合さんは再びゴルフへの情熱を日本に呼び戻すべく、全力 を注いでいる。そして、この挑戦に最もふさわしい人物が、まさに彼なのだ。 起業家一家に生まれた川合さんは、その血筋を受け継ぎ、幼い頃から 鋭いビジネス感覚を自然と身につけていった。「父は私によくこう聞いて きました。『なあ泰、この店って1日でどれくらい売上があると思う?一番 売れている商品はどれだと思う?』」と、幼い頃スーパーマーケットで何度 も繰り広げられた即興の経済の授業を振り返る。そして、国内での大学進 学が一般的な日本で、川合さんがアメリカ留学の道を選んだのは、脈々と 受け継がれてきた独立独行の精神かもしれない。そこには、戦後間もない 頃にアメリカとのビジネスの架け橋を築いた祖父の影響があったようだ。 2007年、モンタナ州立大学を卒業してわずか1年後、川合さんは自身 の初の会社となる「モバーシャル」を設立した。マーケティングを専門とす る代理店である。その年、Appleが初代iPhoneを発表。大型の液晶スク リーンが人々のコンテンツの受取り方を一変させる。変化の兆しを敏感に 察知していた川合さんは、モバーシャルの体制を整えてデジタル動画広告 に特化することにした。それはスマートフォン時代の到来と軌を一にした 戦略だった。2019年に同社を日本の大手広告代理店に売却したのち、川 合さんはプレミアムテキーラ、フランス産高級キャビアやシャンパンといっ たライフスタイルを彩るビジネスを幅広く展開する。ある晩、ビジネスパー トナーでもあった長年の友人とグラスを傾けていたときのこと、軽い調子 で、日本でゴルフクラブを開く可能性について持ちかけられた。韓国人であ る友人は、日本のゴルフ業界には疎く、川合さんにさまざまな質問を投げ かけてきたという。「私の中にあったあらゆるアイデアを彼に話したんです」

Curated by owner Taisuke Kawai, Saintnine has become a sought-after collective of athletes, actors, and executives who see the club as a cultural hub.

was taken aback. But quite quickly, he began to turn the proposition over in his head, appraising it like a gem in the light.

Before long, they acquired an aging golf course in Ichihara, Chiba. From the outset, Kawai imagined a club that was chic and modern, designed to subvert every expectation of a clubhouse. They replaced the dated, Tudor-revival lodge with a modernist threestory venue of raw concrete interiors and panoramic glass windows overlooking the rolling fairways below. In place of membership plaques and stuffy oil paintings, bold works by modern and contemporary artists (Andy Warhol, Damien Hirst, and Kaws, to name a few) fill the walls and stairwells. A sculpture from Kawai’s personal collection, Particle-White Deer (MB) by Osaka-born artist Kohei Nawa, glitters prettily in the lobby. At the restaurant, head chef Yukihiro Ikeda, an alumnus of La Côte d’Or and Joël Robuchon, elevates golf club dining with a refined menu of Japanese, Western, and Chinese cuisines. In lieu of locker rooms, guests unwind pre- and post-round in private suites. Finnish and steam saunas beckon, the perfect remedy after a day of chasing birdies. Other amenities abound: a penthouse suite for private gatherings; in-room dining; for parents, a children’s playpark. “Everybody tells me it’s like a luxury hotel with a golf course,” Kawai says. “It’s the only one in

と川合さん。「そうしたら最後に彼がこう言ったのです。『泰、一緒にやら ないか?』って」。最初は戸惑っていた川合さんだったが、まるで宝石を 光にかざして価値を見極めるように、その提案を頭の中で何度も考え 始めた。

まもなく彼らは、千葉県市原市にある年季の入ったゴルフ場を手 に入れる。当初から川合さんの頭の中には、従来のクラブハウスの常識 を覆すような、洗練されたモダンなクラブの構想があった。時代遅れの チューダー様式のクラブハウスを取り壊し、打ち放しコンクリー トのインテリアと大きなガラス窓が印象的なモダンな3階建て の建物に建て替えた。窓からは、眼下にフェアウェイが一望で きる。会員名を記した銘板や昔ながらの油絵の代わりに、アン ディ·ウォーホル、ダミアン·ハースト、カウズなど現代アートの旗 手による作品が壁や階段を彩る。ロビーには、川合さんの個人コ レクションで、大阪生まれのアーティストである名和晃平による 『Particle-White Deer (MB)』が展示され、光の中で静かに きらめいている。レストランでは、ラ·コート·ドールやジョエル·ロブ ションで研鑽を積んだ池田幸宏シェフが、洗練された日本料理や西洋 料理そして中華料理を調理し、ゴルフクラブでの食体験を新たなレベ ルへと引き上げている。ラウンド前後には、ロッカールームではなく、専 用スイートで寛ぐ。フィンランド式とスチーム式のサウナもあり、ゴルフ 後の身体をやさしく整えてくれる。その他にも、貸切利用できるペント

Japan. There’s no good golf club that has this level of service.”

Then, there is the course itself: an 18-hole, par72 expanse of undulating greens and picturesque tree lines with a dynamic sequence of water hazards and tricky bunkers. The vision is that of famed golf course architect Kentaro Sato, who believes that a course should be indistinguishable from the surrounding natural landscape. Here, the greens are not merely a means to an end. Their grand scale and beauty are designed to be just as captivating as the game itself.

With an average age of 47, Saintnine’s membership skews decades younger than that of Tokyo’s most prestigious golf clubs, whose members are, on average, in their 70s. “This is what everyone wants to achieve in the golf industry,” Kawai says. It is all thanks to Saintnine’s highly curated membership. While other clubs outsource recruitment to agencies, Kawai personally reviews every application. Each of Saintnine’s 400 members, ranging from 35 to 60 years of age, was handpicked by Kawai himself. “My goal was not to sell memberships,” he says. “My goal was to collect the coolest 400 people to my club.”

This approach has made Saintnine among the most sought-after memberships in Japan, attracting an elite clientele of movie stars, professional athletes, and highpowered executives. Partnerships with prestige brands have followed suit, a rarity at Japanese golf courses. As a result, Saintnine enjoys luxuries found at no other golf club. In the lounge await bottles of Suntory whiskey; in the lot are the latest models of luxury cars, including Ferrari and Land Rover. Seeking a Richard Mille? At Saintnine, the only golf club in Japan to be sponsored by the brand, staying in the Richard Mille suite grants you entry into their rarified world—and a coveted step closer to the top of the waitlist.

In every detail, Saintnine embodies Kawai’s singular vision: a space where refinement, exclusivity, and modern luxury converge. It is a testament to the idea that true distinction is never bought. From the sweeping fairways to the art-filled clubhouse, from handpicked members to partnerships with the world’s most esteemed brands, Saintnine is more than a golf club. It is a statement, a culture, a lifestyle. In a world of abundance, Kawai knows the rarest pleasures are not purchased, but earned. And it is this ethos that nurtures the countless creative partnerships that have blossomed on the course. For Kawai, the most fulfilling moments are not sinking a hole-in-one or securing a new member. It is when he witnesses the lifelong bonds kindled amid Saintnine’s unique atmosphere. “That,” he says, “is the happiest moment for me.”

ハウススイート、ルームサービス、子ども向けの遊び場まで揃う。「いろい ろな人から『ここって、まるでゴルフ場つきの高級ホテルみたいだ』と、よく 言われます。日本でこんなレベルのサービスを提供しているゴルフクラブ は他にありませんよ」と、川合さんは語る。

そして、何よりも印象的なのがゴルフコースそのものだ。全18ホール、 パー72。起伏に富んだグリーンが広がり、美しい木立が続く。そこにウォー ターハザードや難しいバンカーが巧みに配置されている。設計を手がけた のは、ゴルフコース設計家として名高い佐藤謙太郎さんだ。佐藤さんは、周 囲の自然に溶け込むようなコースという設計思想を掲げる。このコースで は、グリーンは単なる目的地ではない。スケールの大きさと造形の美しさ は、ゴルフのゲームと同じように、魅惑的な存在として設計されている。

セイントナインの会員の平均年齢は47歳と、平均70代の東京の名門 ゴルフクラブと比べて何十年も若い世代が中心となっている。「今のゴル フ業界の誰もが、まさにこういうクラブを目指しているのです」と川合さ んは語る。その背景には、セイントナインの徹底的に厳選された会員があ る。他のクラブが会員募集を代理店に委託する中、セイントナインでは川 合さん自身がすべての申請書類に目を通す。現在の会員は400名で、年齢 は35歳から60歳。全員が川合さんによって直接選ばれた人たちである。 「私の目的は会員権を売ることではなく、最もクールな400人をクラブに 集めることだったのです」と川合さんは言う。

この独自の方針が、セイントナインを日本で最も注目を集める会員制 ゴルフクラブのひとつへと押し上げ、映画俳優やプロアスリートそして一 流企業のエグゼクティブなど、名だたる会員を惹きつける原動力となって いる。さらに、日本のゴルフ場では珍しく、名門ブランドとの提携も実現。ラ ウンジにはサントリーのウイスキー、駐車場には最新モデルのランドロー バーが並ぶ。リシャール·ミルの時計をお探しですか?セイントナインは日 本で唯一、リシャール·ミルがスポンサーを務めるゴルフクラブであり、リ シャール·ミル·スイートを利用すれば、同ブランドの選ばれし世界に足を 踏み入れ、憧れのウェイティングリストの上位に名を連ねることも夢では ないのだ。

セイントナインには、そのすべてのディテールにおいて、川合さんの一貫 したビジョンである洗練と特別感そして現代的ラグジュアリーが息づく。 真の品格とは、「決して金銭で手に入れるものではない」という理念を示 している。広々としたフェアウェイから、アートが彩るクラブハウス、選び抜 かれた会員、そして一流ブランドとの提携に至るまで、セイントナインは単 なるゴルフクラブの域を超えている。それは、主張であり、文化であり、ライ フスタイルそのものなのだ。豊かさに満ちたこの時代にあって、最も希少 な悦びとは、買うことではなく得ることだと川合さんは信じている。そして、 川合さんのその哲学によって、コース上で数多くの革新的なパートナー シップが育まれてきたのだ。川合さんにとって、最も幸せを感じる瞬間とは ホールインワンでも、新規会員の獲得でもない。セイントナインという特別 な空間の中で、一生続くような絆が生まれるとき。「その瞬間こそが、私に とって何よりの幸せなのです」と、川合さんは語る。

fosters the human spirit

カヴァブーム到来

by Martha Cheng

文 = マーサ・チェン

by Cody Faraon and John Hook

写真 = コーディ・ファラオン、ジョン・フック

In Hawai‘i and across the country, more people are drinking in the calming and convivial effects of kava, a root with a deep history. ハワイ、そして全米でカヴァを楽しむ人が 増えています。飲めば心が落ち着き、饒舌 になる。長い歴史を持つこの飲みものは、 カヴァの根っこでつくります。

“Kava is meant for conversation,” says Daya Nand, owner of Fiji Kava. “But we’re conversating, and there’s no kava.” Nand remedies the situation by pouring us each a full cup of kava. “Bula!” he says, the Fijian equivalent of “cheers,” as we clink cups and chug the murky tan liquid. Now, deeming us appropriately relaxed, he continues our chat in his kava bar, tucked under a parking ramp on Dillingham Boulevard and facing a row of auto-body shops housed in Quonset huts. In the back is the machine he had specially made in California to pulverize the kava roots he imports from Fiji. He started Fiji Kava more than 20 years ago because, as a fourth-generation Indo-Fijian, “kava is our culture,” he says. In Fiji, “if anything is messed up, the chief will call a meeting. Everybody comes, sits down, drinks kava, and they solve the problem. But if you have Heineken, you be the problem.”

Kava has been cultivated and consumed throughout the South Pacific for at least 2,000 years, its roots pounded and mixed with water to make a drink known for its calming effect. In ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, it’s known as ‘awa, and it was one of the canoe crops brought over by the first Polynesians who settled Hawai‘i. It plays a ceremonial as well as social role—the latter increasingly in kava bars that have been multiplying across the country. Galen McCleary, the general manager of Pu‘u O Hōkū Ranch on Moloka‘i, which sells its freshly frozen and pulverized ‘awa to individuals and kava bars across the Hawaiian Islands and as far as Florida, says the demand for ‘awa has grown significantly in recent years. The farm currently has approximately 15 acres in ‘awa production and is establishing about 1,000 new plants

「カヴァは会話を楽しむためにあるんだ」そう 語るのは、〈フィジー・カヴァ〉のオーナー、ダヤ・ ナンドさんだ。「こうして話をするのに、カヴァが ないのはまずいな」ナンドさんはわたしたちのコ ップになみなみとカヴァを注ぎ、「ブラ!」と声を あげた。フィジー語で”乾杯”を意味する言葉だ。 わたしたちはかちんとコップを合わせ、ベージュ 色の濁った液体を一気に飲み干した。こちらが いい具合にリラックスしたとみなし、ナンドさん はまた話しはじめた。〈フィジー・カヴァ〉はディ リングハム・ブルバードの駐車場の下にあり、向 かいにはクオンセット・ハット(トタンづくりのか まぼこ型の建物)の自動車修理工場が並ぶ。店 の奥にはカリフォルニアでつくらせた特注の粉 砕機があって、フィジーから輸入したカヴァの 根はここで潰している。ナンドさんが店をはじめ たのは20年以上前。四世代目のインド系フィ ジー人である彼は、「カヴァはわたしたちの文 化だ」と言う。フィジーでは「何か問題があ れば、酋長が会合を開く。村人たちが集まっ て腰を下ろし、カヴァを飲みながら問題を解 決する。これがカヴァでなくハイネケン(ハワ イで人気のオランダのビール)だったら、自分 が問題を起こしちまう」

南太平洋全域で、少なくとも2000年以上前 から栽培されてきたカヴァ。根を砕いて水と混ぜ た飲みものは、鎮静効果があるとして人々に親 しまれてきた。ハワイ語ではアヴァと呼ばれ、最 初にハワイへ渡ってきたポリネシア人によって 持ち込まれたカヌープラント(カヌーで太平洋を わたった人々が、食用や薬用としてカヌーに積 み込んだ植物)のひとつだ。儀式や社交の場で その役割を果たしてきたが、最近は全米で急増 するカヴァ・バーで社交的役割の比重を高めて いる。モロカイ島の〈プウ・オ・ホークー牧場〉で は、新鮮なうちに冷凍、そして粉砕したアヴァを 個人向け、そしてハワイの各島はもちろん、遠く

Translation by Eri Toyama 翻訳 = 外山恵理

a year. (It takes about three and a half years to produce a mature crop.) “The demand for it definitely outstrips our supply, and we’re trying to keep up,” McCleary says. “Part of [the rise in interest] is due to the trend of people getting off alcohol and looking for substitutes. I think during the pandemic, people who were drinking ‘awa started drinking more of it, and people who had never heard of it before have started to try it and drink it.”

Pu‘u O Hōkū started growing ‘awa in the ’90s, planting varietals that McCleary’s father, Joel, and Ed Johnston, who helped found the Association for Hawaiian ‘Awa, had collected from around Polynesia and Hawai‘i. The farm now grows 16 varieties, from the popular Hiwa to the potent Isa, which McCleary says is the strongest in kavalactones, the compounds in the kava plant that are responsible for its effects. He’s partial to Mo‘oula, which he says occupies a middle ground in strength, and is from a variety that was found above Hālawa Falls. “It’s not as well known because it’s a Moloka‘i varietal, but I love that it’s from here.”

はフロリダまで、全米各地のカヴァ・バー向けに販売している。同牧場のジ ェネラルマネージャー、ゲイレン・マクリアリーさんによれば、近年需要は 急増しており、現在15エーカーの畑に加えて、毎年約1000株を新たに植 えているそうだ。(収穫できるまで成長するのに約3年半かかる。)「需要が 供給を完全に上まわっていて、追いつくのがやっとです」とマクリアリーさ ん。「アルコールを控える人が増え、その代わりになるものを探すのがトレ ンドになっているのも影響していますね。パンデミックのあいだに、以前か らカヴァを飲んでいた人は前より頻繁に飲むようになり、それまでカヴァ を知らなかった人も飲むようになったんです」 〈プウ・オ・ホークー牧場〉がアヴァの栽培をはじめたのは’90年代。マ クリアリーさんの父ジョエルさんと、ハワイ・アヴァ協会の創設に関わった エド・ジョンストンさんが、ポリネシアやハワイの各地から集めてきた品種 を植えた。現在は人気の高い“ヒヴァ”から、カヴァの作用をもたらすカヴァ ラクトン含有量がもっとも高いとされる“イサ”まで16種を栽培している。

マクリアリーさんのお気に入りは中程度の強さの“モオウラ”で、ハーラ

On a recent Monday evening at Kava Queen Kava Bar, housed in a yellow silo in the Old Waialua Sugar Mill, two men—one wearing a shirt with an image of two musubi and the words “kinda fit kinda fat”—order kava mocktails. They carry their drinks, made with kava concentrate and layered with pineapple juice and hibiscus, to the tables outside. At the bar, Ava Taesali’s father, who is running Kava Queen this night, tells the women at the counter about an upcoming open mic night. Ava (her name means kava in Samoan, which her father says was purely a coincidence) started the bar last October. In addition to fruity concoctions, powdered kava root from Vanuatu and Fiji is prepared more traditionally—mixed with water and served in a coconut shell. I approach Micael Haskins, who looks like a regular, after seeing him down two shellfuls.

The first time he tried ‘awa was a few years ago, when he was visiting Seattle from Moloka‘i for a conference. “Funniest thing, that kava was from Pu‘u O Hōkū,” he says. He first heard about kava from a post on Facebook, and he was drawn to its cultural history and its potential as an alternative to alcohol. Now, he comes to Kava Queen when he’s on O‘ahu and, at home, prepares his own, sometimes with the fresh frozen ‘awa from Pu‘u O Hōkū and sometimes with the powdered root. He handles the task with the same care that he applies to brewing coffee, experimenting with different water temperatures and types. (He’s partial to making it with Waiākea bottled water.) He finds that ‘awa helps with anxiety as well as the body aches he acquired from playing football. And on weekends, he’ll mix up a big batch for gatherings.

‘Awa encourages conviviality. Weekly ‘awa nights with live music used to be one of the main draws at Da Cove Health Bar and Cafe on Monsarrat Avenue. The fast-casual café has recently reintroduced the occasional ‘awa night since the pandemic, and ‘awa is available on the daily menu. Elsewhere, kava has seen a resurgence in the form of kava wellness shots and sparkling kava drinks, but at Da Cove you’ll find Pu‘u O Hōkū’s ‘awa still served the traditional way: mixed with just water. According to the staff, when Da Cove first opened in 2003, mostly locals would come for the ‘awa; these days, it’s mainly visitors. Still, on a recent late afternoon, after most of the açaí bowl-hungry crowds have cleared out, a group of kama‘āina (local residents) are gathered at a table in the back, chatting over sandwiches, smoothies, and ‘awa. Kava, after all, is made for conversation.

ヴァ滝の上流で見つかった品種。「知名度は低いですが、モロカイの在 来種というところが気に入っています」

とある月曜の夜、〈オールド・ワイアルア・シュガー・ミル〉の黄色いサ イロのなかにあるカヴァ・バー、〈カヴァ・クイーン〉では、二人の男性 がカヴァ・モクテルを注文していた。片方の男性の着ているTシャツに は、おむすびがふたつと“kinda fit kinda fat(そこそこ締まってて、 そこそこデブ)”の文字。ふたりは濃縮カヴァにパイナップルジュースと ハイビスカスを重ねたドリンクを手にして外のテーブルに着いた。バー では、その夜、店をまかされていたアヴァ・タエサリさんの父親が、カウ ンターの女性客に近く開催予定のオープン・マイク・ナイト(誰でもパ フォーマンスできるイベント)の説明をしている。アヴァさんは、去年の 10月にこのバーを開いた(彼女の名前はサモア語の“カヴァ”と同じだ が、それは単なる偶然なのだそう)。果汁を合わせたカクテル風ドリン クのほか、バヌアツやフィジー産のカヴァの粉末を水で溶き、ココナツ の殻で供する伝統的なスタイルも健在だ。わたしは、ココナツの殻で カヴァを二杯飲み干した常連風のマイケル・ハスキンスさんに声をか けた。

ハスキンスさんが初めてアヴァを試したのは、数年前、モロカイから シアトルへ会議で出張したときだそうだ。「そのとき飲んだカヴァが、 〈プウ・オ・ホークー牧場〉のものだったところがおもしろいでしょう」 カヴァの存在を初めて知ったのはFacebookで、その歴史文化やアル コールの代替品としての可能性に魅力を感じていたそうだ。今では、オ アフ島に来れば〈カヴァ・クイーン〉に立ち寄り、自宅でも〈プウ・オ・ホ ークー牧場〉の冷凍アヴァや粉末を使ってカヴァをつくる。コーヒーを 淹れるときと同じように水の温度や種類をいろいろ試して研究してい るそうだ。(水はワイアーケア社のボトル入りがお気に入りとのこと。) 不安を鎮め、フットボール選手時代から続く体の痛みもやわらげてく れるというアヴァを、週末にはたっぷりつくって大勢で楽しむ。

アヴァは会話をはずませる。モンサラット通りにある手軽なカフェ、〈 ダ・コーヴ・ヘルス・バー&カフェ〉では、かつて毎週行われるライブつ きの『アヴァ・ナイト』が人気だった。パンデミック以降も不定期に開催 されていて、『アヴァ・ナイト』ではないときもメニューにアヴァがある。 ほかの店では健康にいいカヴァ・ショットやカヴァ入りのスパークリン グ飲料などカヴァの新しい飲み方も人気だが、〈ダ・コーヴ〉では今も〈 プウ・オ・ホークー牧場〉のアヴァをただ水で溶いただけの伝統的なス タイルで提供している。スタッフによれば、2003年の開店当時、アヴァ を注文するのはおもにローカル客だったが、今では観光客が中心だ。 それでも、アサイボウル目当ての客が引けたある午後、店の奥にはサン ドイッチやスムージー、そしてアヴァが並ぶテーブルで語らうカマアー イナ(地元の住民)の姿があった。

カヴァはやっぱり会話を楽しむための飲みものなのだ。

流れに逆らって

Text by Martha Cheng

文:マーサ·チェン

Images by McKenna Conforti, Josiah Patterson, and Brent Rand

写真: マッケナ・コンフォルティ、ジョサイア・パターソン、ブレント・ランド

Bizia Surf transforms one of Hawai‘i’s most destructive trees into a sustainable alternative for the surfboard industry.

ハワイの生態系を脅かす木を サステナブルなボードに 変貌させるビジアサーフ

What’s first striking about the surfboards is how beautiful they are. Made with lengths of invasive albizia, they feature striations of blonde and light brown, like the highlights in a surfer’s hair. Then, upon picking them up, what’s most noticeable is how light they are—the fish model weighs the same as a standard twin fin, the 9-foot longboard is barely heavier than a typical noserider. In the water, too, they are surprisingly lively—buoyant, even.

Made by Bizia Surf, these surfboards take one problem—the environmentally toxic production process and materials of modern-day boards—and address it with another: invasive albizia, one of Hawai‘i’s most destructive trees. Introduced to the islands in 1917 from Indonesia as a reforestation effort, Hawai‘i’s albizia are among the fastestgrowing trees in the world, crowding out native ecosystems as they gain more than 15 feet a year. In 2004, heavy rains and albizia debris caused the flooding of Mānoa stream and an estimated $85 million in damage. In 2014, albizia became known as “the tree that ate Puna” when thousands of them fell during Hurricane Iselle, destroying houses, downing power lines, and blocking roads.

Because of how quickly albizia grows, it was commonly assumed that the wood was weak. Still, in 2015, Joey Valenti, then an architecture graduate student, lamented when he saw huge albizia

最初に目を奪われるのは、その美しさだ。侵入 種であるアルビジア材を用いたサーフボードは、 ブロンドや淡いブラウンの縞模様をまとい、まる でサーファーの髪に差し込むハイライトのよう に輝いている。そして手に取れば、その軽さに驚 かされる。フィッシュモデルは標準的なツインフ ィンと同じ重さで、9フィートのロングボードで すら一般的なノーズライダーよりほんの少し重 い程度だ。さらに水に浮かべてみると、その動き は驚くほど軽やかで、確かな浮力さえ伝わって くる。

ビジアサーフが生み出したサーフボードは、 環境に有害な製造工程や素材という現代のボ ード業界が抱える課題に対し、もう一つの問題 となっているハワイの自然を脅かす侵入種ア ルビジアを活用することで挑んでいる。1917 年、植林を目的にインドネシアから持ち込まれ たアルビジアは、世界でも最も成長の早い樹木 のひとつで、年間4.5メートル以上も伸びて在 来の生態系を圧迫してきた。2004年には豪雨 とアルビジアの倒木がマノア川の氾濫を招き、 推定8,500万ドルの被害をもたらした。さらに 2014年、ハリケーン·イゼルの猛威で何千本も のアルビジアが倒れ、家を破壊し、電線を寸断 し、道路をふさいだことから、この木は「プナを 飲み込んだ木」と呼ばれるようになった。

アルビジアは成長の早さゆえに、長らく「脆弱 な木」と決めつけられてきた。だが2015年、建 築学の大学院生だったジョーイ·ヴァレンティ は、リヨン樹木園で高さ45メートルにも及ぶ巨 木が次々と伐採され、本来なら建材となり得る

Translation by Akiko Shima 翻訳 = 島有希子

trees, some 150 feet tall, cut down during a removal project at Lyon Arboretum and learned that the logs— free potential lumber—were just being dumped. With the help of a structural engineer, Valenti found that the wood was just as strong as Douglas fir, a common lumber, and set out to prove that you could build with albizia.

In the process, he went to visit master woodworker Eric Bello at his millwork shop in Wahiawā. In that first meeting, he spotted an albizia surfboard behind Bello. “I felt like I was in the right place,” Valenti says. For years, though, his attention was diverted by his architecture thesis project, and with Bello’s help, he set to work on “Lika,” a proof of concept for albizia as a building material. When the arched wooden structure resembling the Waikīkī Shell was completed in 2018 and displayed on the front lawn of UH Mānoa, demand for Valenti’s work immediately grew. High-profile clients like the Patagonia store at Ward and 1 Hotel in Princeville tapped him to design albizia elements for their properties. “And then, at some point,” he says, “I just started chipping away at the surfboard idea on the side, very covertly.”

For the next four years, he developed prototypes for surfboards made entirely out of albizia and, in 2021, won a $250,000 USDA Wood Innovations Grant to build the boards. In 2023, he debuted the boards at the Bizia Surf storefront in Wahiawā, situated across from Bello’s mill. At the hybrid coffee shop and surf store, the various surfboard models line the walls like artwork.

The wood is scavenged from around the island when utility companies, land owners, and community members are looking to clear out albizia. Valenti calls the diverted wood, which might otherwise be destined for the dump, a “resource misplaced.” And while Valenti uses a high-tech process at Bello’s shop to manufacture the surfboards, the philosophy underlying them is an old one. Native Hawaiians made the first surfboards out of koa and other local wood. “Obviously they figured out the properties of the different woods, what worked best— buoyancy and all that,” Valenti says.

Then in the late ’20s and through the ’30s, as the sport spread beyond the islands, surfers experimented with hollowing out the solid wood boards. These laid the groundwork for the chambered designs that famed shaper Dick Brewer would popularize in the ’60s and ’70s. That albizia board that Valenti first saw in Bello’s shop? It was modeled after a Dick Brewer gun. But while guns are typically heavy and made for massive waves, Bizia’s other, more everyday models are much lighter and crafted from hollowed-out lengths of albizia, making them strong yet nimble and versatile. Valenti partners with Carson Myers, Chris Miyashiro, and other local Hawai‘i shapers to produce Bizia’s growing lineup of boards, which includes a tow board and twin

丸太がただ廃棄されていく様子を目にし、深い無念を覚えた。そこで彼は 構造エンジニアとともに木材の強度を検証。その結果、アルビジアは一般 的な建材であるダグラスファーに匹敵する強度を備えていることが判明 し、彼はその建築資材としての可能性を証明する道を歩み始めたのであ る。

その道程の中で、ヴァレンティはワヒアワにある工房を訪ね、木工職人 のエリック·ベロと出会う。初めて顔を合わせたその日、ふとベロの背後に 立てかけられたアルビジア製のサーフボードに目を留めた瞬間、胸に直 感が走ったという。「ここに導かれてきたのだと感じました」と、ヴァレンテ ィは振り返る。とはいえ、その後数年は建築学の修士論文に注力し、サー フボードのことはいったん脇に置かざるを得なかった。だがベロの協力 を得ながら、彼はアルビジアを建材として証明するための試作プロジェク ト“Lika”に取りかかっていった。

ワイキキ·シェルを思わせるアーチ状の木造構造物が2018年、ハワイ 大学マノア校の芝生に完成·公開されると、ヴァレンティの名は一躍注目 を集めた。ほどなくして、ワードのパタゴニア店舗やカウアイ島プリンスヴ ィルの1ホテルといったハイエンドなクライアントから、アルビジアを用い たデザイン依頼が舞い込むようになる。「ある時から、ひそかに片手間で サーフボードのアイデアにも取り組み始めていたんです」と彼は振り返る。 その後の4年間、彼はアルビジアのみで削り出しすサーフボードの試作を 重ね、2021年には米国農務省から25万ドルの助成金「ウッド·イノベーシ ョンズ·グラント」を獲得。製作の本格化へと踏み出した。2023年には、ワ ヒアワにあるベロの工房の向かいに店舗をオープンし、自らのボードを披 露。コーヒーショップとサーフショップを融合させた空間では、壁一面に並 ぶサーフボードがまるで美術作品のように展示されている。

原木は、電力会社や土地所有者、地域住民がアルビジアの伐採を行う 際に、島のあちこちから回収される。本来なら廃棄されるはずの木材を、ヴ ァレンティは「行き場を失った資源」と呼び、新たな命を吹き込んでいる。

ヴァレンティはベロの工房で最新技術を駆使してサーフボードを製作して いるが、その根底にある哲学は古来のハワイ先住民に通じるものだ。彼ら はコアをはじめとする在来の木材で最初のサーフボードを作り、材ごとの 特性や浮力の違いを見極めていた。「彼らは当然のことながら、どの木が 最適で、どの材が浮力に優れるかを熟知していたんです」とヴァレンティは 語る。

1920年代後半から30年代にかけて、サーフィンがハワイを越えて広ま ると、サーファーたちは無垢材のボードをくり抜く実験を始めた。この技術 はやがて発展し、1960~70年代には名シェイパー、ディック·ブルーワー が普及させたチャンバー構造の原型となる。ヴァレンティがベロの工房で 初めて目にしたアルビジア製のボードも、実はブルーワーのガンを模した ものだった。通常ガンは重量があり、巨大な波を相手にするための道具だ

fin fish along with traditional Hawaiian paipo and alai‘a boards. His team has also been developing a new line of sustainable expanded polystyrene boards with a proprietery albizia stringer technology for highperformance surfing.

Bizia Surf presents an alternative to the toxic processes that have dominated the surf industry since the ’50s, when polyurethane boards became the norm— favored by shapers because they were quicker and cheaper to make. Other similarly toxic materials, like epoxy and fiberglass, soon saturated the market. “The world today is all messed up in terms of where materials come from and our supply chains,” Valenti says. “There’s so much damage that we’ve done.”

Despite surfing’s overtones of environmental sustainability, it’s an issue that the industry is still learning to contend with. “We’ve gone completely away from sustainability,” Valenti says. “So having some avenues to go back in the direction of traditional surfing and still have the performance—to me, that’s the most compelling part of it all.”

が、ビジアサーフが手がけるその他のモデルは、日常的なサーフィンを想 定している。アルビジアをくり抜いて成形することで、軽さと強度、そしてし なやかさを兼ね備え、汎用性にも優れているのだ。ヴァレンティはカーソ ン·マイヤーズやクリス·ミヤシロら地元ハワイのシェイパーたちと組み、ビ ジアサーフのラインナップを次々と広げている。トウボードやツインフィン· フィッシュに加え、伝統的なハワイアンのパイポやアライアまで。さらに現 在は、高性能サーフィン向けに独自のアルビジア·ストリンガー技術を組み 込んだ、サステナブルな発泡ポリスチレン製ボードの新シリーズ開発にも 挑んでいる。

ビジアサーフは、1950年代以降サーフ業界を支配してきた有害な製造 プロセスに対し、新たな選択肢を示している。ポリウレタン製のボードが 標準となったのは、シェイパーにとって製造が速く、安価だったからだ。そ の後はエポキシやグラスファイバーといった、同じく有害な素材が市場を 席巻していった。「いまの世界は、素材の出どころもサプライチェーンもす っかり混乱しています」とヴァレンティは語る。「私たちが積み重ねてきた 環境へのダメージは計り知れません。」 サーフィンには「自然と共生するスポーツ」というイメージがあるが、業 界の現実はその理想からいまだ遠い。「僕たちはサステナビリティからす っかり外れてしまったんです」とヴァレンティは言う。「だからこそ、伝統的 なサーフィンのあり方に立ち返りながら、なおかつパフォーマンスも保て る。その可能性こそが、何より魅力的だと思うんです。」

時を超えて息づくハワイ建築

Text by John Wogan

文 = ジョン・ウォーガン

写真 = マーク・クシミ

As cookie-cutter new-builds become the norm on O‘ahu, a group of homeowners and architects are leading a quiet resistance by restoring its midcentury treasures.

画一的な新築住宅が当たり前になりつつあるオアフ島で、 かつての時代が息づくミッドセンチュリー建築をよみがえらせようと、 静かに抵抗の炎を灯す住まい手と建築家たち

Translation by Akiko Shima 翻訳 = 島有希子

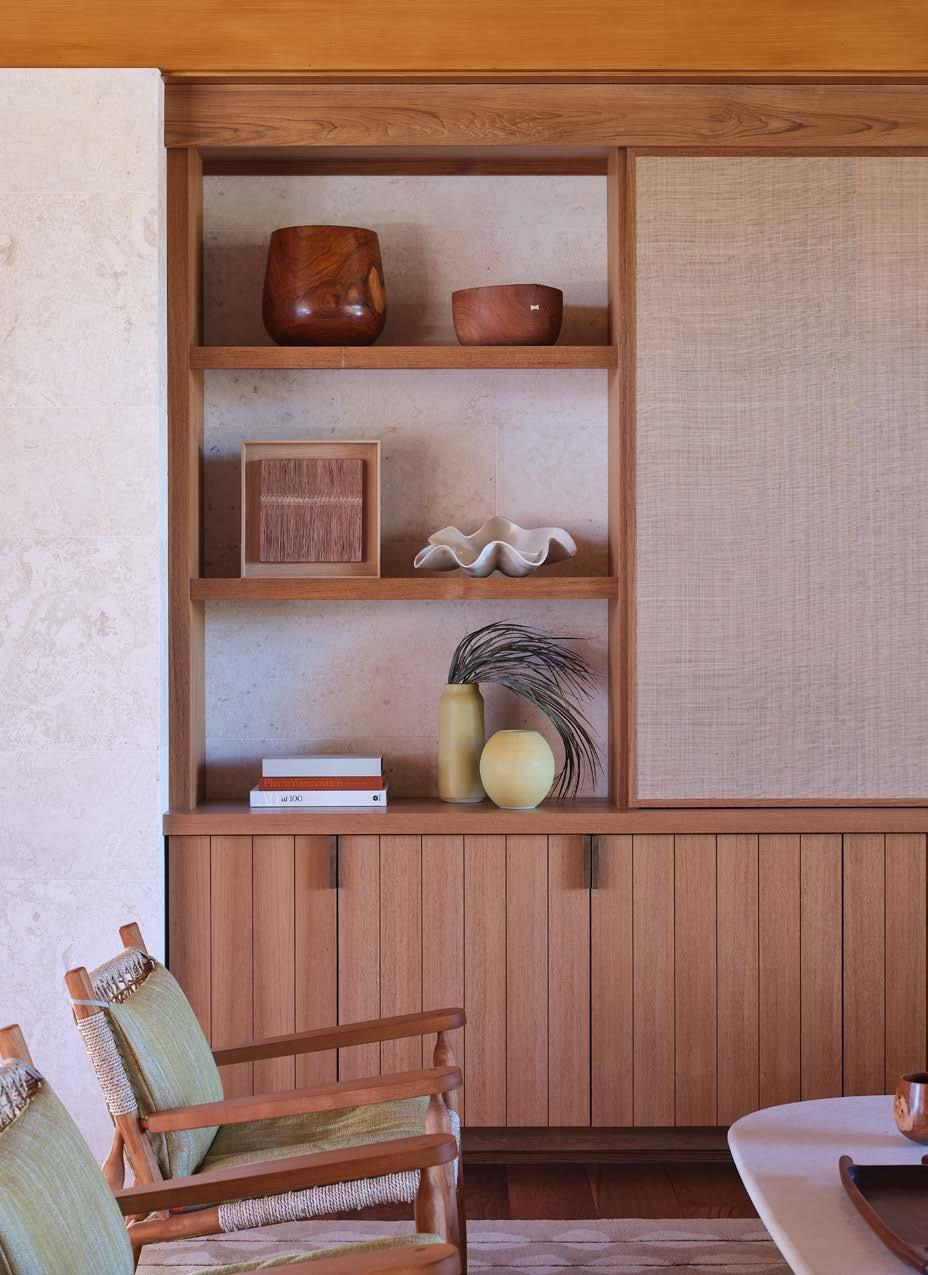

Tucked into the valleys, ridgelines, and coastal enclaves of O‘ahu are some of the most quietly remarkable houses of the Pacific. These midcentury homes defined the residential architecture of the ’30s through ’70s and reimagined island living, blending modernist principles with an acute sensitivity to climate, topography, and local materials. They are also becoming increasingly rare. As newer builds crowd the island with sealed glass towers and air-conditioned convenience, a small but devoted group of homeowners are preserving the legacy of O‘ahu’s historic homes. They’re choosing not just to live in these spaces, but to restore and reimagine them with reverence.

オアフ島の谷間や稜線、海辺の入江に抱かれるように佇む家々。その静か な存在感は、太平洋の景観の中でもひときわ印象的だ。1930年代から 70年代にかけて建てられたこれらのミッドセンチュリー住宅は、近代建 築の精神を礎としながらも、気候や地形、そして島の素材に寄り添うこと で、“ハワイらしい暮らし”の新たな形を描き出してきた。しかし、こうした家 々は今、急速に姿を消しつつある。密閉されたガラスの高層ビルや、空調 設備の快適さに依存する新築住宅が島を覆うなか、オアフにはなお、過去 から受け継いだ住まいを守り続ける人々がいる。彼らはただそこに暮らす のではなく、敬意を込めて修復し、未来へとつなぐべく新たな命を吹き込 んでいるのだ。

For this devoted group of homeowners, preserving midcentury homes is less about nostalgia as it is about a dedication to thoughtful, place-based design.

Brian Lam knows better than most what that devotion looks like. The founder of the product recommendation service Wirecutter (which he sold to the New York Times in 2016) and a self-taught craftsperson, Lam spent five years restoring an Albert Ives-designed home tucked near Diamond Head with a motor court, courtyard, lānai, yard, and pool, all looking toward the ocean. “It was hell on earth,” Lam admits. “I didn’t go on vacation for four years. I wanted to quit all the time.” By the end of the renovation, though, he’d not only rebuilt the house, he had also reshaped his own life. In the half-decade since he acquired the home, he transformed from a novice admirer of woodwork to an apprentice in Japanese carpentry.

Lam’s approach to restoration was shaped by a deepening appreciation for both the structural intentions of Ives and the lineage of Japanese design that influenced Hawai‘i’s architectural language. The project also became a study in material limitations and craft traditions. “There isn’t anything too exotic in Ives’s homes—redwood, fir, a little koa,” Lam says. “But all owners of historic houses live in absolute terror of finding craftspeople sensitive enough to work on them as well as appropriate materials of high enough quality.” That anxiety—of loving a home but not knowing how to care for it—drove him to become a student of traditional methods. “I had zero woodworking experience [when I bought the house],” he says. “But I went to Japan to look at buildings with an architect

その揺るぎないこだわりを、誰よりも体現しているのがブライアン・ラム だ。商品推薦サービス「Wirecutter」を立ち上げ、2016年にニューヨー ク・タイムズに売却した後、独学で職人の道を歩み始めた彼は、ダイヤモン ドヘッドの麓にあるアルバート・アイヴス設計の邸宅を、5年の歳月をかけ て修復した。モーターコートや中庭、ラナイ、庭、そして海を望むプール。あ らゆる空間が海とつながるその家を甦らせる作業は、「地獄のようだった」 とラムは振り返る。「何度も投げ出したくなり、4年間、一度の休暇さえ取 らなかった」と。しかし、修復を終えた頃には、彼は家を再建しただけでな く、自らの人生もまた新たに形づくられていた。家を手にしてからの5年間 で、木工を愛でる初心者だったラムは、日本の大工技術を学ぶ弟子へと変 貌を遂げたのだ。

ラムの修復への姿勢は、アイヴスが込めた構造的意図、そしてハワイの 建築に息づく日本的デザインの系譜への敬意を深めるなかで育まれてい った。その過程はまた、素材の制約と、受け継がれてきた職人技を探る旅 でもあった。ラムは語る。「アイヴスの家に使われているのは、特別に珍し いなものではない。レッドウッドやモミ、それにほんの少しのコア材くらい さ。でも歴史的住宅のオーナーにとって一番の恐怖は、その価値を理解し てくれる繊細な感性を持った職人を見つけられるか、そして十分に質の高 い材料を確保できるかというなんだ。」 「家を愛していながら、その守り方がわからない。」そんな不安がラム を伝統的な技法の学びへと駆り立てた。彼は振り返る。「家を買ったとき、

who worked at a carpentry firm. Witnessing them craft the most beautiful wood joinery I had ever seen left an impression, and I finally picked up some tools two years later. By the end of the restoration project, I was able to help with some of the carpentry.”

For Lam, though, the desire to preserve an older home such as his extends beyond aesthetics. The best homes in Hawai‘i, he says, were designed for “the way we live in this corner of the world.” Often, older residences were built to be in harmony with the islands: floorplans harness the tradewinds, deep eaves shade from the encroaching sun, covered outdoor spaces extend living areas into the garden. As such, these historic houses are inherently more conducive to island living. The effect is particularly pronounced when compared to the “square boxes from Southern California architects we see these days,” Lam says. “What happens to these foolish designs when they are closed off from the breezes or it starts raining when the windows are left open on a house with no eaves?”

Across town, art advisor Kelly Sueda took a quieter, but no less intentional, approach to restoring his family home, which was designed in 1959 by Vladimir Ossipoff, the most celebrated architectural modernist in Hawai‘i. Sueda grew up steeped in midcentury design. His father was an architect who briefly worked with Ossipoff in the late ’60s. Inside their family home in Mānoa, Wasilly and Eames chairs and Saarinen tables were fixtures of daily life. So when Sueda and his wife stumbled across an unlisted Ossipoff property nestled behind a stand of trees, just eight houses from their own, the decision to buy was immediate. “The second I saw it, I called my wife and told her to wake up the kids from their nap and walk over,” he recalls. “Three weeks later, we owned it.”

The renovation was driven by a desire to update the home for modern living while staying true to Ossipoff’s principles, including an indoor-outdoor fluidity, deep connection to the landscape, and a restrained palette of natural materials. “We opened up the kitchen to the dining room and removed the shoji doors to the living room, which unlocked ocean and Diamond Head views from the heart of the home,” Sueda says. But nothing was changed without thought. Every redwood scrap was saved, repurposed, or matched. “One of the greatest compliments I received from an Ossipoff purist was asking if I had done anything to the home,” he says. “I really wanted it to feel like what could have been the original design.”

Sueda’s favorite details are the ones that serve both function and the story of the house. A coral tree once

大工仕事の経験はゼロだったんだ。でも建築事務所の建築家と一緒に日 本を訪れ、歴史的建築を見て回った。そこで目にしたのは、これまで見た 中で最も美しい木組みを作り上げる職人たちの姿で、強烈な印象を受け た。2年後にようやく自分でも道具を手に取り、修復が終わるころには、い くつかの作業を手伝えるまでになっていたんだ。」

ラムにとって、古い家を守り続けたいという思いは、単なる美観を超えた ものだ。ハワイにおける最良の住まいとは、「この土地ならではの暮らし方 に合わせて設計されている」と彼は言う。古い家の多くは、島の自然と調 和するように建てられていた。間取りは貿易風を巧みに取り込み、深いひ さしは容赦なく照りつける太陽を遮る。屋根付きのアウトドア空間は、居 住空間を庭へと自然に広げていた。だからこそ、こうした歴史ある家々は、 生まれながらにして島の暮らしに心地よく寄り添っている。その魅力は、近 ごろ目にする「南カリフォルニアの建築家が設計した四角い箱」と比べれ ば一層際立つとラムは語る。「環境に合わない設計の家では、風を遮って しまったり、ひさしのない家で雨が降り込んできたら、一体どうなってしま うだろう?」

街の反対側では、アートアドバイザーのケリー・スエダが、家族の住まい を修復するにあたり、控えめながらも確かな意図を込めた手法を選んだ。 その家は1959年に、ハワイで最も名高いモダニズム建築家、ウラジミー ル・オシポフによって設計されたものである。スエダは、幼い頃からミッド センチュリー・デザインに親しんで育った。父親は建築家で、1960年代後 半にオシポフのもとで短期間働いた経験がある。マノアにある一家の家で は、ワシリーやイームズの椅子、サーリネンのテーブルが、日常の風景の 一部として自然に存在していた。ある日、スエダ夫妻は、自宅からわずか八 軒先の木立の奥にひっそりと佇む未公開のオシポフ設計の家を偶然見つ け、即座に購入を決めた。「見た瞬間、すぐに妻に電話して、子どもたちを 昼寝から起こして一緒に見に行こうと言ったんだ」と彼は振り返る。「そし て三週間後には、もう僕たちの家になっていたよ。」

改修は、現代の暮らしに合わせつつオシポフの設計理念を尊重して進 められた。屋内と屋外が自然に溶け合う空間、周囲の風景との深い結びつ き、落ち着いた自然素材の色調。こうした要素を大切にしながらの改修だ った。「キッチンとダイニングをつなげ、リビングへの障子を取り払ったこ とで、家の中心にいながら海やダイヤモンドヘッドの景色を楽しめる」とス エダは語る。しかし、何も考えなしに手を加えたわけではない。すべてのレ ッドウッド端材は捨てずに再利用するか、必要に応じて同材で補った。「オ シポフの熱心な愛好家から『本当に何か手を加えたの?』と尋ねられたと

shaded the lānai, helping frame the angular structure in nature. When it fell in a storm, the loss felt personal, but Sueda soon found a replacement to keep the spirit of the original tree intact. Today, a juniper grows in its place.

Ossipoff’s trio of fireplaces—traditional brick in the living room, a copper freestanding one in the den, and a rare hibachi-style fireplace—remain untouched. “We still use it when we barbecue with friends,” Sueda says of the kitchen hibachi. “It’s a unique double-sided hibachi that opens and closes from inside and outside the house. So if we’re entertaining or cooking steaks for family night, we can have charcoal-cooked barbecue from inside the kitchen. I love it.”

Twelve years after completing the renovation, Sueda still finds himself learning from Ossipoff. He once considered removing a wall to expand the living room view, until he realized they housed pocket doors. “When we experienced the first Kona windstorm, I understood why they were designed that way,” he says. “He cleverly placed all the venting windows east and west so the air could flow through the room but not endanger the interior from inclement weather. These kinds of things shaped my views on architecture.”

Architect Graham Hart, co-founder of Kokomo Studio, also understands the power of restraint. Along with his business partner, Brandon Large, Hart took on the renovation of a midcentury residence for homeowner clients Taea Takagi-Jones and Grant Jones in 2022, completing the project in 2024. Built along Tantalus, a winding neighborhood along the Ko‘olau’s slopes, the

き、最高の褒め言葉だと感じたよ。まるで最初からそうだったかのような 設計にしたかったんだ。」

スエダがとりわけ気に入っているのは、機能性と家の物語の両方を兼 ね備えたディテールだ。かつてラナイを覆っていたデイゴの木は、角ばっ た建物を自然の中に巧みに収める役割を果たしていた。しかし嵐でその 木が倒れたとき、その喪失感は個人的なものに近かったという。ほどなく してスエダは後継の木を見つけ、現在はネズの木がその場所に根を張り、 かつての精神を受け継いでいる。オシポフ設計の家にある三つの暖炉は いずれも手を加えずに残されている。リビングの伝統的なレンガ造りの暖 炉、書斎の銅製独立型、そして珍しい火鉢スタイルの暖炉だ。キッチンの 火鉢についてスエダは言う。「友人たちとバーベキューをするときは、今で もこの火鉢を使っている。屋内と屋外の両方から開閉できるユニークな両 面式の火鉢で、家族のディナーやステーキを焼くときでも、キッチンの中か ら炭火焼きが楽しめるから、とても気に入っているよ。」

改修を終えて12年が経った今も、スエダはオシポフの設計から学び続 けている。かつてリビングの眺めを広げようと壁を取り払おうと考えたこ ともあったが、よく見るとその壁には引き込み戸が仕込まれていることに 気づいた。「初めてコナ風の嵐を経験したとき、なぜこう設計されていたの かが腑に落ちた」と彼は語る。「オシポフは風通しの窓を巧みに東西に配 置し、部屋の中に空気を循環させつつ、悪天候から家を守っていた。こうし た細やかな工夫の数々が、僕の建築観を形作ってくれたんだ。」

建築家でココモ・スタジオ共同設立者のグラハム・ハートも、控えめな美 の力を理解している。ビジネスパートナーのブランドン・ラージとともに、

home was designed by Philip Fisk, another important but lesser-known architect from Hawai‘i’s postwar boom. Fisk’s homes were clean and clever, marked by fixed grids, honest geometry, and a precise logic in materials. Yet, time hadn’t been kind to the Forest Ridge bungalow. The kitchen had been haphazardly expanded, its layout confused by decades of ad hoc remodeling.

Hart’s job, as he saw it, was to subtract. “We didn’t add square footage and didn’t drastically change the location of rooms. Instead, we simplified and cleaned up the design,” he says. One challenge was structural. The kitchen had a load-bearing wall bisecting the space. Removing it required a new beam and an ‘ōhi‘a post to pick up the roof load, an elegant solution that now blends into the open plan. Another hurdle was material: The original redwood tongue-and-groove, tight-grain and unpainted, was irreplaceable. Most of the salvaged wood couldn’t be reused. Against the odds, the contractor found a local mill with a matching supply. After multiple finish tests, they achieved a tone that blended seamlessly with the old wood, and it could even be applied to new oak cabinetry. “Now that the kitchen is done and it’s opened up to the rest of the living space, it feels rightly situated as the center of the home for both school nights and entertaining,” Hart says. “It is a continuation of the rest of the house, and though all of it is new, it reads as old.”

The location also shaped the renovation. Tantalus is some degrees cooler than town, and it is one of the few places in Hawai‘i where a fireplace isn’t just ornamental. “These single-wall houses have no insulation, so it’s actually necessary,” Hart explains. Yet the home still had to manage solar heat gain, so they added horizontal fins to shade the southern facade, and swapped out windows for sliding glass doors to increase airflow. “Keeping the internal spaces open with minimal walls, and having as much permeability to the exterior walls, also helps in keeping the space naturally ventilated on those humid days in the mountains,” Hart says.

The throughline with each project is a shared ethic of care, a belief that these historic homes are more than relics. They are living systems, responsive to climate and culture, that only survive when inhabited with knowledge and humility. “If I were to build a new home now, I would utilize all the gifts Ossipoff gave us in this house,” Sueda says. “Intelligent design, I’ve learned, can also be aesthetically beautiful.”

ハートは2022年、オーナーのタエア・タカギ=ジョーンズとグラント・ジ ョーンズのためにミッドセンチュリーの住まいの改修を手掛け、2024年 にプロジェクトを完成させた。コオラウ山脈の斜面に沿って曲がりくねる 住宅街、タンタラスに建つこの家は、戦後のハワイで活躍した、もう一人の 重要だがあまり知られていない建築家、フィリップ・フィスクによって設計 された。フィスクの住宅は、整然としたレイアウト、無駄のない設計、素材 への論理的なアプローチに支えられた、清潔で巧妙なデザインが光る。し かしフォレスト・リッジのバンガローには、時間の影が色濃く残っていた。 キッチンは無秩序に増築され、数十年にわたる場当たり的な改装によって 間取りは混乱していた。

ハートが考えた修復の方針は「引き算」だった。「延べ床面積を増やした わけでも、部屋の配置を大きく変えたわけでもない。その代わり、デザイン をシンプルにして整えたんだ」と彼は語る。最初の課題は構造だった。キッ チンには空間を二分する耐力壁があり、それを取り除くために新しい梁と オヒアの柱を設け、屋根を支える必要があった。その結果、開放的な間取 りに自然に溶け込む、洗練された解決策となった。次の課題は素材だ。も ともとのレッドウッドの羽目板は木目が細かく無塗装で、代えのきかない ものだった。回収できた材のほとんどは再利用できなかったが、幸運にも 施工業者が同じ質感を持つ材を扱う地元の製材所を見つけ出した。仕上 げのテストを何度も繰り返し、古い木材となじむ色合いを実現。新しいオ ーク材のキャビネットにも同じ仕上げを施すことができた。「キッチンが完 成し、リビングスペース全体とつながったことで、平日の食事からホームパ ーティーまで、家の中心にふさわしい場所になった」とハートは語る。「す べて新しく作り直したはずなのに、家全体と連続して感じられ、まるで昔 からそこにあったかのように感じられるんだ。」

立地もまた、改修の方向性に影響を与えた。タンタラスは町よりも数度 気温が低く、ハワイの中でも暖炉が単なる装飾ではなく、実際に役立つ数 少ない場所のひとつだ。「こういうシングルウォールの家には断熱材が入 っていないので、実際に暖炉が必要なんだ」とハートは説明する。しかし日 中には太陽の熱もコントロールする必要があった。そのため南向きの外壁 には水平の庇を設け、窓はスライディングガラス扉に替えて風通しを良く した。「内部空間は壁を最小限にして開放的に保ち、外壁とのつながりを 増やすことで、山間部の蒸し暑い日でも自然な通風を確保できる」とハー トは語る。

どのプロジェクトにも共通しているのは、家に対する思いやりの精神だ。 そこには、これらの歴史的な住まいが単なる過去の遺物ではなく、今も生 き続ける場所であるという信念が息づいている。気候や文化に応じて呼 吸する生きたシステムであり、知識と謙虚さをもって住まうことで初めて、 その価値は保たれる。「もし今、新しい家を建てるとしたら、この家でオシ ポフが教えてくれたあらゆる知恵を生かすだろう」とスエダは語る。「学ん だのは、知的なデザインは美的にも優れているということだ。」

Infusing the Phillip Fisk-designed home with a midcentury asceticism meant paring back, rather than adding onto, the space’s design.

Latin Grammy award nominee Erik Canales retreats to a private estate on the south shore of O‘ahu, where relaxed silhouettes and breezy fabrics evoke an air of coastal modernism.

Photography by Mark Kushimi

Art Direction and Production by Kaitlyn Ledzian

Wardrobe Styled by Jade Alexis Ryusaki

Wardrobe Assistance by Cory Ching

Hair and Makeup by Tamiko Hobin

Modeled by Erik Canales

experiences

both

faraway and familiar

ハーマークアに今もあるもの

Text by Eunica Escalante

文 = ユーニカ・エスカランテ

Images by Anna Pacheco

写真 = アナ・パシェコ

Along the windward shoulder of Hawai‘i Island, the Hāmākua Coast holds its past close even as change edges in.

ハワイ島東部をなぞるハーマークア・コースト。押し寄せる変化 の波にのまれず、身近なところに過去が今も息づくエリアです。

Translation by Eri Toyama 翻訳 = 外山恵理

Driving through the Hāmākua Coast, the phrase “old Hawai‘i” tends to float to the front of one’s mind. There is an archetypal romance in the ever-present ocean along the horizon, the former sugar towns’ scatter of plantation-style houses, the way that the vegetation seems to grow with a restless energy. It is possible to visit Hāmākua and only see this rote rendering—the bucolic roadside fruit stands and the Instagram-ready vistas. But if that is all you take in, then you have not seen Hāmākua at all.

The coast begins where the road curves north of Hilo and ends just beyond the last of the sugar towns, where the cliffs give way to the rolling cattle pastures of Waimea. It is a place best understood in motion, seen

ハーマークアの海岸に沿って車を走らせると、“古きハワイ”という言葉が 頭をよぎる。水平線まで果てしなく続く海。かつて砂糖産業でにぎわった シュガー・タウンに散らばるプランテーション・スタイルの家屋。とどまる ことなく生い茂る植物。いかにも旅の浪漫をかきたてる風景が続く。ハー マークアを訪れる人の多くは、のどかな道端の果物スタンドなど、インスタ 映えする景色を見て満足してしまうが、じつはそれだけではハーマークア を本当に見たことにはならない。

ハーマークアの海岸線はヒロの北、道がカーブするあたりからはじまり、 最後のシュガー・タウンを通り過ぎ、断崖がワイメアの牧草地に変わるあ たりまで続く。この地を理解するには、ハワイ島東部を縫うように走るハワ イ・ベルト・ロードをドライブしながらその起伏を感じるのがいちばんだ。

from the contours of Hawai‘i Belt Road as it threads along the eastern hem of Hawai‘i Island. The Pacific here is not the lapis blue of a postcard but a kind of mutable slate, burnished silver in the rising dawn and blackened by afternoon squalls. Visitors are often surprised that it rains here. In their minds, Hawai‘i is a place of perennial sunshine. Yet, in Hilo and upward along the coast, it is as much a part of the landscape as the gulches and waterfalls and steep cliffs overlooking the Pacific.

“‘Ele‘ele Hilo, panopano i ka ua—Hilo is black, dark with rain,” goes one ‘ōlelo no‘eau, or Hawaiian proverb. Here, rains are etched into the collective memory, their testament in the landscape. In thickets of strawberry guava and parasol trees that crowd the road’s shoulder. The monstera leaves that grow wider every season. The houses, with their spacious lānai and peeling, pastelhued exteriors, sinking deeper into the green.

These rains served the titans of industry well, particularly the sugar barons who came here in the late 1800s to turn land into profit. For nearly a century, Hāmākua was sugar country. Swaying stalks of cane dominated the landscape. Tens of thousands of migrants arrived to the islands over the decades in boatloads from Japan, China, and the Philippines, drawn by promises of a new life. Instead, they disembarked as indentured laborers, bound to harsh contracts enforced by a legal system that proved nearly impossible to navigate across linguistic and cultural barriers. Many found themselves in Hāmākua’s sugar fields. The work was long, and the hours longer still. The wages, never enough. Housing was company property, stores were company stores, and the lines between labor and life blurred until it was impossible to tell where one ended and the other began.

ここから見る太平洋は、絵葉書のような瑠璃色ではなく、灰色がかった移 ろいやすい青。日が昇る夜明けには銀色に輝き、午後にはスコールで黒 々と染まる。訪れる人は雨の多さに驚く。いつでも太陽が降り注ぐのがハ ワイと思っているのだろう。だがヒロも、海岸沿いから北へと向かう一帯 も、渓谷と滝、断崖、そして雨は景色の一部だ。“エレエレ・ヒロ、パノパノ・ イ・カ・ウア(ヒロは黒、雨で暗い)”というハワイ語の言いまわしがあるよ うに、人々の記憶には雨が風景と一緒に刻まれる。道沿いに茂るストロベ リーグアバの木立ちやパラソルツリー、季節を重ねるごとに大きくなるモ ンステラの葉。広々としたラーナイを持つ色あせたパステルカラーの家々 は、緑のなかに深く埋もれている。

豊かな雨は、有力な実業家、とくに19世紀後半にやってきた砂糖王た ちには恵みの雨そのものだった。ハーマークアはおよそ1世紀にわたって 砂糖の一大産地で、あたり一面にサトウキビが揺れていた。日本、中国、フ ィリピンから、毎年数千人の移民が船でやってきた。だが、人生の新たな 門出に胸をふくらませて船を降りた彼らを待っていたのは、年季奉公だっ た。過酷な仕事に長い労働時間。少ない賃金。社宅で暮らし、買い物も会 社の店でしかできない労働者たち。仕事と生活の境はぼやけ、区別がつか なくなっていく。それでも彼らはやってきた。希望と必要が生み出した夢を 抱いて……。

かつてのサトウキビ農園は姿を消し、ハーマークア砂糖会社も1994年 に閉鎖された。跡には牧草地とコーヒー畑、マカダミアナッツの林が広が るばかりだ。それでも古い町の名前は残っている。パアウイロ。ラウパーホ エホエ。ホノムー。それだけではない。オノメア湾の海岸にはコンクリート の杭が突き出ている。沖に停泊する船にサトウキビを積み込むクレーンの 残骸だ。ハカラウ・ビーチ・パークでは、古い製糖所の壁が落書きと蔦に覆

Still, they came, drawn by a dream shaped as much by hope as necessity.

The old sugar plantations are gone now; Hāmākua Sugar Company, the last on the island, shuttered in 1994. In their place are pasturelands, coffee fields, and macadamia groves. Yet, the old town names remain: Pa‘auilo, Laupāhoehoe, Honomū. Other things remain, too. At ‘Onomea Bay, concrete posts jut out from the shoreline, remnants of sugar derricks that sent sugarcane down to the ships anchored offshore. At Hakalau Beach Park stand the walls of an old mill, graffitied and veiled under a tangle of vines. In Honoka‘a, near the center of town, a simple memorial of wooden posts are crowned by a Japanese tiled roof. Inscribed on the plaque is a newspaper excerpt from 1889: “A Japanese storekeeper, K. Goto, was found dead this morning at 6 o’clock, hanging to a cross arm on a telephone pole about 100 yards from Honoka‘a jail.” Katsu Goto was 28 when four men lynched him. It was retaliation, supposedly, for a nearby canefire the night before. More likely, it was to prevent him from making more labor demands on behalf of plantation workers. It would be some decades before the unions made any real progress in Hāmākua. Yet, even as signs of the plantations wear away each year, Goto’s memory continues to stand along Mamake Street. The past does not rest quietly in Hāmakua. It presses itself against the present, like the kudzu that grows over the abandoned cars on the roadside.

Here’s where the disequilibrium of the Hāmākua Coast sets in. It feels eternal, yet it is continually changing, more so in recent decades as tourism creeps along its edges. The main street of historic Honoka‘a Town, once an avenue of stores that sold provisions for working-class locals, is lined now with antique shops of overpriced Hawaiiana souvenirs. The century-old hardware store, B. Ikeuchi & Sons, has shuttered its doors and sold the last of its inventory. On the road to Akaka Falls, there are signs advertising bicycle rentals and a zipline over Umaumau Falls. Along a bluff overlooking ‘Onomea Bay, a former bed-and-breakfast is now a four-star luxury hotel, Hāmākua’s first.

Yet, it is still possible to live in Hāmākua and not be confronted by the crowds and the tour buses. The harshness that once made this place good for little but sugarcane has kept the rest of the coast relatively untouched, held apart from the development and tourism rampant elsewhere. Here, there are no broad sand beaches to draw the casual tourist. Only the waves breaking against the craggy shoreline in a white churn that does not invite swimming. There are no all-inclusive resorts, no luxury shopping districts. Instead, one must come to Hāmākua for other reasons: to watch the light shift on the Honoka‘a cliffs, to stand on the rim of Waipi‘o

われていた。ホノカアの町の中心に、木の柱に日本の瓦屋根をいただく質 素な慰霊碑があった。刻まれているのは1889年の新聞記事。“今朝6時 頃、日本人商人、後藤勝(かつ)がホノカア刑務所から約100ヤード離れ た電信柱の横木に首を吊った状態で発見された”。28歳のカツ・ゴトウは 4人の男のリンチを受け、殺された。表向きは前夜、近隣のサトウキビ畑で 起きた火災への報復とされたが、おそらくサトウキビ農園の労働者の権利 を主張する彼を黙らせたのだろう。ハーマークアで労働組合が実際に発 言力を持つようになるのはそれから数十年先のこと。それでも、プランテ ーション時代の痕跡が年ごとに薄れていく今でさえ、ゴトウの慰霊碑はマ マケ・ストリートに立っている。ハーマークアの過去の記憶は静かに眠ら ない。道端で朽ち果てた廃車を覆うクズの蔦のように、現在にまとわりつ いている。

だが、ハーマークア・コーストのいびつさを感じるのはこんなときだ。永 遠に変わらないように見えるのに、つねに変化している。近年はツーリズ ムがひたひたと忍び寄り、変化はとくに著しい。歴史を感じさせるホノカ ア・タウンのメインストリートは、かつて労働者の生活必需品を売る店が 並んでいたが、今や高価なハワイアナのみやげ物を売るアンティークショ ップが軒を連ねる。100年以上続いた金物店〈B・イケウチ&サンズ〉は最 後の商いを終え、閉店してしまった。アカカ・フォールへ向かう道には自転 車のレンタルやウマウマウ・フォールを見下ろすジップラインの看板が並 ぶ。オノメア湾を望む断崖には、かつての民宿を改装した四つ星ホテルが 登場した。ハーマークア初の高級ホテルだ。

それでも、観光バスや人混みと関わることなくハーマークアで暮らすこ とは可能だ。かつてはサトウキビ以外に何も育たなかった厳しい自然のお かげで、ハーマークアの海岸はほかの地域のような猛烈な開発やツーリズ ムから守られてきた。ここには、無邪気な観光客を引き寄せる広い砂浜は ない。岩だらけの磯に荒波が白く砕ける海は泳ぎには向かないのだ。食事 やアクティビティがすべて料金に含まれるリゾート施設もなければ、高級 ブランドが並ぶショッピングセンターもない。ハーマークアを目指す人は、 求めるものが違う。彼らの目的は、ホノカアの断崖に映る光の移り変わり を眺めたり、ワイピオ渓谷の縁に立って霧にけぶるタロ畑を眺めること。ハ ワイがハワイを演じる前の、ありのままの姿を見つけることなのだ。 ハーマークア・コーストの旅を振り返れば、海や断崖だけでなく、ちょっ とした一瞬もよみがえる。ホノムーにあるエドズ・ベーカリーの外で、ふた りの見知らぬ女性と話が弾んだ朝のひととき。オールド・マーマーラホア・ ハイウェイ沿いの牧草地で戯れていた子牛。パーパーイコウで雨に降ら れ、湿った苔と土の匂いに包まれた瞬間。そうした一瞬こそが、ハーマーク ア・コーストがほかの場所とは違うことを思い出させてくれる。ハーマーク アは容易に本当の姿を見せない。急ぎ足で通り過ぎる人や、来るだけの 価値があると証明する何かがないとだめな人には向かない場所だ。ハー

The plantations may be gone, but the memories of labor, resilience, and migration remain etched in the landscape.

Valley and look down at the taro patches in the mist, to see a Hawai‘i that is not yet a simulacrum of itself. Thinking back on it later, there are recollections not only of the ocean and the cliffs but the moments in between: the two ladies who spent a morning talking story with you outside of Ed’s Bakery in Honomū, the calf frolicking in a pasture along Old Māmālahoa Highway, the damp smell of moss and earth as the rain came down outside of Pāpā‘ikou. These are the small markers of a coastline that resists summary, for Hāmākua does not give itself away easily. It is not for the hurried nor for the ones who need constant affirmation that they have arrived somewhere worth being. To experience Hāmākua, you must be willing to be slowed down by it: by the winding roads, by the rain, by the green that grows over everything. It is for those willing to follow the road north and see where it takes them, knowing it is less about what has been preserved and more about what persists.

マークアを知りたければ、ハーマークアに足並 みをそろえよう。曲がりくねった道。雨。すべてを 覆い尽くそうとする植物。何が待っているのか 見てやろうという気持ちで、北へ向かう道を進 もう。そこでは、残されたものではなく、生き残 ったものたちが待っている。

台北のその先

Text by Martha Cheng

文 = マーサ・チェン

Images by Eagan Hsu, Bells Mayer, Alex Robertson, and Kevin Wang

写真 = イーガン・シュー、ベルス・メイヤー、アレックス・ロバートソン、ケヴィン・ワン

From surfing Taiwan’s wild east coast to sampling food in its oldest city, a writer explores a nation facing an ever more uncertain future.

野生味あふれる台湾東海岸でのサーフィンに、台湾最古の町 での食の探求。不確かさを増す未来に直面する台湾を歩いて みました。

Translation by Eri Toyama 翻訳 = 外山恵理

There was definitely a swell. We stood on the seawall at Jinzun Harbor and watched the shorebreak slam against the coastline’s giant concrete tetrapods, artificial structures meant to dissipate the ocean’s energy.

“Let’s go,” I told my boyfriend.

“But no one’s out,” he said.

“Isn’t this the reason why we travel to surf?” I said impatiently. “For empty waves?”

We paddled out, but I did not end up riding a single wave. Instead, the current swept me out, and when it released its grip, the only way I could reach the shore was to paddle straight into the breakwater barriers. But I couldn’t get back in without getting thrown against the

うねりは確かに入ってきていた。わたしたちは金樽(ジンズン)漁港の防 波堤に立ち、巨大なコンクリートのテトラポッドに砕けるショアブレイクを 見つめた。テトラポッドは海のエネルギーを分散させるための人工構造物 だ。

「入ろうよ」と、わたしは彼をうながした。

「でも、誰も入ってない」

「だからこそ旅をしているんでしょ?」わたしは彼に迫った。「誰もいない 波を求めて来たんじゃない?」

結局パドルアウトはしたが、わたしは一本も波に乗れなった。強いカレン トに流され、ようやく解放されたと思ったら、岸に戻るには不気味にそびえ

ominous-looking concrete structures. Finally, I ditched my board and let the water pitch me as I reached out for one of the legs of the tetrapods and clung to it like a starfish. In a brief pause between waves, I climbed up the breakwall.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. A few hours later, we happened on another break. This time, there were people surfing the perfect, peeling waves. My boyfriend joined them while I sat on shore, bruised and bleeding.

This is not the Taiwan I grew up knowing. The one I knew was the one most visitors to the island likely picture: its capital, Taipei, with its bustling night markets, the birthplace of Din Tai Fung and its famous soup dumplings, and where my parents and I would pilgrimage for niu rou mian (beef noodle soup) so spicy it would make my dad sweat even more in the city’s humidity. We’d cool off with shaved ice heaped with grass jelly and sweetened taro and start every morning with a Taiwanese breakfast of savory soy milk, fan tuan (sticky rice rolls), and shaobing (flat bread).

My parents were part of the wave of Chinese immigrants that fled to Taiwan starting in 1949 after the Nationalists lost to Mao in China’s civil war. My maternal grandfather was a general to Chiang Kai Shek, whom my mother idolized. But in more recent years, I learned the darker side of his rule: the martial law he imposed for 38 years, one of the longest impositions of martial law, and the suppression of Taiwanese culture and language. The more I learned about Taiwan, the more it reminded me of Hawai‘i, with its layers of history and waves of settlers beginning with Taiwan’s Indigenous populations—to which Polynesians trace their origins.

A different facet of Taiwan drove me to the island on each visit. The surf led me to Taiwan’s rugged east coast, lush and junglelike. While Taiwan’s larger cities like Taichung in the west and Kaohsiung in the south match the energy of its teeming capital, the lack of high-speed rail connections in the east coast keeps this side of the island rural. After a few days surfing near Dulan, we headed inland to Chishang, biking around its rice paddies and stopping in open-air cafés for locally grown coffee as well as tea steeped with dried mulberry leaves and cakes baked with milled rice. We stumbled across a tofu skin factory, where sheets of soy hung like clothes on the line to dry.

It wasn’t until I read Clarissa Wei’s 2023 cookbook Made in Taiwan, in which she declared that Tainan is the best place in Taiwan to eat, that I started exploring that southern city. I couldn’t believe that I knew so little about it, despite it being the oldest city in Taiwan and its capital for 200 years, until the capital was moved north in 1887.

るコンクリートのテトラポッドに正面から突っ込むしかない状況に陥って いた。テトラポッドに叩きつけられるのは必至だ。結局、わたしはボードを 捨て、波に翻弄されながらテトラポッドの脚に必死に手を伸ばし、ヒトデ のようにしがみついた。そして、波と波の一瞬の合間にどうにか防波堤を よじ登ったのだ。

だが、悲劇はそこで終わらなかった。数時間後、わたしたちは別のブレイ クを発見した。そこにはちゃんと人がいて、美しくブレイクするパーフェクト な波を楽しんでいた。わたしの彼はその人たちに仲間入りしたが、わたし は打ち身と擦り傷だらけで浜辺に座って待つしかなかった。

そこは、わたしが育った台湾とは違った。わたしの知っている台湾は、た いていの旅行者が思い浮かべる台湾と同じだ。活気に満ちた夜市で知ら れる首都、台北(タイペイ)。小籠包で有名な〈鼎泰豊(ディンタイフォン) 〉発祥の地。両親と通ったニューロウミェン(牛肉麺)の店。湿気の多い台 北で、汗かきの父がスパイシーな麺を食べてますます汗だくになったあと は、仙草ゼリーや甘いタロイモがてんこ盛りのかき氷で涼をとる。朝は豆 乳に飯 糰(ファントゥア台湾おにぎり)、焼餅(シャオビン 中華風フラット ブレッド)の台湾式朝食ではじまる。

わたしの両親は、1949年以降、国共内戦で毛沢東に敗れた国民党とと もに台湾に渡った中国人移民だ。母方の祖父は、母が崇拝する蒋介石に 仕えた将軍だった。しかし近年になって、わたしは38年という異例の長さ の戒厳令、台湾文化や言語への抑圧など、蒋介石時代の闇を知った。台 湾について知れば知るほど、わたしの頭のなかで、もとからいた先住民族 にはじまり、さまざまな民族が押し寄せては定住した歴史を持つハワイと 台湾が重なった。ポリネシア人のルーツもまた、台湾の先住民族だと言わ れている。

訪れるたび、また別の顔に魅了されるのが台湾だ。荒々しい緑におおわ れた、ジャングルみたいな東海岸を訪れたのは、サーフィンが目的だった。

西の台中(タイチュン)や南の高雄(カオシュン)は首都台北に似た喧騒 に満ちているが、高速鉄道が伸びていない東部には今も島らしい牧歌的 な風景が広がる。都蘭(ドゥーラン)で数日サーフィンに興じた後、わたし たちは池上(チーシャン)へと足を延ばし、田んぼ道を自転車でめぐり、オ ープンカフェで地元産のコーヒーや桑の葉茶、米粉の菓子を味わった。偶 然見つけた湯葉工場では、洗濯物みたいに干された湯葉が風に揺れてい た。

2023年に出版されたクラリッサ・ウェイの料理本『メイド・イン・タイワ ン』で“台湾でいちばんおいしい街は台南”という一節を読むまで、わたし は台南を訪れたことがなかった。台湾最古の街で、1887年に台北に移る

Since then, I’ve become so taken with the city that on my most recent trip, I bypassed Taipei entirely, taking a bullet train directly from the airport and arriving in Tainan about 90 minutes later.

Tainan has what I love most in cities: narrow, chaotic alleyways to get lost in and a tenacious hold on the past, whether through its architecture or its food. It has the highest concentration of temples in the country; I glimpsed their gilded and green rooftops, their corners curved skyward, in nearly every alley and road I walked down. The city’s Buddhist and Taoist temples are woven into residents’ daily lives. At Dongyue Temple, built in 1673 and dedicated to the Taoist ruler of the underworld, people communicate with the dead; on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, the birthday of Qiniangma, the protector of children, parents bring children to Kailung Temple for coming-of-age rituals; and at the temples throughout, I see students burning paper prayers for help in passing their exams.

And, of course, there is food everywhere. Vendors set up under sprawling banyan trees and sell nian gao (sticky rice cakes) from the back of motorbikes while small eateries spill out onto the sidewalks serving xiao chi (small eats) and sliced fruits sprinkled with plum powder, or what we know in Hawai‘i as li hing. Unlike in Taipei, the food feels less shaped by Japan’s colonial influence and Nationalist tastes. Most tourists come to Taiwan to eat—those that head to Tainan come to taste old-style Taiwanese cooking. That means dan zai mian, soup noodles with braised minced pork and shrimp; steamed, dense, and savory rice pudding; milkfish fillets in a clear broth. For moments of respite from the heat, I slip into the Art Deco building of Hayashi Department Store, which sells clothing and crafts from local artists. The bottom floor is dedicated to food omiyage, including Taiwan’s famously sweet dried mangoes, while the top floor houses a rooftop balcony, café, and—perhaps less expectedly—a Shinto shrine and bullet holes from a U.S. aircraft during World War II.

But it is impossible to talk about Taiwan these days without acknowledging China’s increasingly aggressive push for unification with the self-governing, democratic nation. It’s especially hard to ignore in Tainan, where Taiwan’s military jets roar overhead with the regularity of clockwork. In my mind, the pull of the past in Tainan— where Taiwanese, rather than Mandarin, is the language I hear most on the streets; where the revival of Siraya, one of Taiwan’s many Indigenous languages, is underway; and where the gu zao wei, or “ancient early taste,” flavors its dishes—feels like the island’s concrete bulwarks along the coast: protection against an uncertain future.

まで200年にわたって首都でもあったのに、それまで台南についてほとん ど何も知らなかったことが信じられなかった。それ以来、すっかり台南の 虜になった。今回の旅では、台北を素通りして空港から高速鉄道に飛び乗 り、90分後には台南に着いていた。

台南にはわたしが街を愛する理由のすべてがある。迷子になりそうな路 地、建築にしろ食にしろ、頑固なまでに伝統を重んじる気風。ここは台湾 でもっとも寺院が集中する街で、どの路地を歩いても四隅が空に向かって カーブする金色や緑色の屋根が目に入る。仏教や道教の寺は、台南人の 暮らしにしっかり根付いている。1673年建立の東嶽殿(ドンギュエ)には 死後の世界を司る道教の神が祀られ、人々は死者と会話する。旧暦の七 夕は子どもの守護神、七娘媽(チィニャンマー)の誕生日で、成人式を祝う 親子連れが開隆宮(カイルング)を訪れる。わたしが訪れたときは、受験を 控えた学生たちがひっきりなしにやってきて、紙のお札を燃やしてお参り をしていた。

そしてもちろん、どこにでも食がある。ガジュマルの樹の下に露店が並 び、バイクの荷台で年糕(ニェンガオ 餅)、歩道にあふれ出した小さな食 堂では小吃(シャオチー 軽食)やプラムパウダー(ハワイでいうリーヒ ン)をまぶした果物が売られている。台北料理には日本統治や国民党文 化の影響が見られるが、台南の食は台湾らしさを色濃くとどめている。台 湾を訪れる人のほとんどは食が目的だが、台南を目指す人は蒸した豚と えびの入った台湾ラーメン、担仔麺(タンツャイミェン)やぎゅっと詰まっ た風味豊かなおこわ、サバのすまし汁など、昔ながらの台湾を味わうため にやってくる。暑さに疲れたらアールデコ建築の〈林百貨店〉で休憩し、地 元のアーティストによる工芸品や衣服を見て歩く。百貨店の地下には台湾 名産のドライマンゴーなど土産用の食品が並び、屋上にはカフェだけでな く、神社や第二次世界大戦中の米軍機による弾痕など思いがけないもの が残っていた。

だが今日、台湾を語るとき、激しさを増す一方の中国からの統一への圧 力を無視することはできない。台湾は自治権を持つ民主国家であるのに、 だ。とくに台南では、台湾軍のジェット機の轟音が時計のように規則的に 頭上を通過する。街を歩けば北京語よりも台湾語が聞こえ、数多い先住 民族言語のひとつであるシラヤ語の復興運動もはじまり、何を食べても“ 古早味(グーザォウェイ 昔ながらの味)”を感じる台南は、あのコンクリ ートのテトラポッドのように、不確実な未来にあらがう砦のように思えた。

An iconic Gold Coast destination, on the beach in Waikīkī at Lē’ahi

Travel + Leisure, ‘Top 500 Hotels in the World’ Hau Tree Lauded by Hale ‘Āina, Wine Spectator & ‘Ilima Awards Stunning New Oceanfront Celebration Spaces, for all Occasions Mu‘u & Mimosas, A Kaimana Tea Party Golden Hour Pau Hana

delectable hidden

gems

Honolulu’s supper clubs are gaining popularity as a chic way to gather around the table.

Translation by Akiko Shima

Supper clubs, an American culinary tradition dating back to the 1930s, have long blended gastronomy and community, offering a space where meals become shared experiences. Prolific across the Midwest, supper club establishments reached their zenith in the mid-20th century, before the rise of chain restaurants led to their decline. In recent years, driven by a desire for connection in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, supper clubs are en vogue once again. Unlike the supper clubs of old, however, many of these new iterations take the concept beyond the restaurant, transforming homes, studios, and unconventional spaces into temporary dining rooms. Here, we experience three distinct Honolulu supper clubs—traveling from a bamboo forest in Pālolo to a modernist home in Hawai‘i Kai to a concept space in Kaka‘ako—where diners are invited to explore culture, artistry, and connection, one carefully plated bite at a time.

Follows the Wai

Dinner was in the middle of a bamboo forest deep in Pālolo Valley. The only sign we’d arrived—and not lost ourselves in the valley’s maze—was a small sticker on the wooden gate, marked with the emblem of our host and chef, Yuda Abitbol. Hiking down sinuous steps, we reached a clearing where two small, rustic cabins sat. Abitbol padded barefoot onto the deck, ushering us in with a smile. He had lived here for a year, in a home that felt plucked from his daydreams. The property’s bohemian asceticism—hemmed in by wilderness; room enough for a bedroom and a kitchen-cum-dining room—certainly aligns with Abitbol’s own, a chef who has distinguished himself from the local culinary scene with his wild-to-table philosophy, wherein every meal is comprised of ingredients he has personally sourced from the wild. Since 2021, Abitbol has run Follows the Wai, a dining and foraging project that takes this ethos to curious diners across the islands.