Elevated Amenities, Unforgettable Moments

The Launiu Ward Village residences are an artful blend of inspired design and timeless sophistication. Expansive views extend the interiors, and a host of amenities provide abundant space to gather with family and friends.

Studio, One, Two, and Three Bedroom Residences

THE PROJECT IS LOCATED IN WARD VILLAGE, A MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT IN HONOLULU, HAWAII, WHICH IS STILL BEING CONSTRUCTED. ANY VISUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF WARD VILLAGE, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, RETAIL ESTABLISHMENTS, PARKS, AMENITIES, OTHER FACILITIES AND THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS THEREIN, INCLUDING THEIR LOCATION, UNITS, VIEWS, FURNISHINGS, DESIGN, COMMON ELEMENTS AND AMENITIES, DO NOT ACCURATELY PORTRAY THE CONDOMINIUM PROJECTS OR THE MASTER PLANNED DEVELOPMENT. ALL VISUAL DEPICTIONS AND DESCRIPTIONS IN THIS ADVERTISEMENT ARE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY. THE DEVELOPER MAKES NO GUARANTEE, REPRESENTATION OR WARRANTY WHATSOEVER THAT THE DEVELOPMENTS, FACILITIES OR IMPROVEMENTS OR FURNISHINGS AND APPLIANCES DEPICTED WILL ULTIMATELY APPEAR AS SHOWN OR EVEN BE INCLUDED AS A PART OF WARD VILLAGE OR ANY CONDOMINIUM PROJECT THEREIN. EXCLUSIVE PROJECT BROKER WARD VILLAGE PROPERTIES, LLC, RB-21701. COPYRIGHT ©2025. EQUAL HOUSING OPPORTUNITY.

WARNING: THE CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF REAL ESTATE HAS NOT INSPECTED, EXAMINED OR QUALIFIED

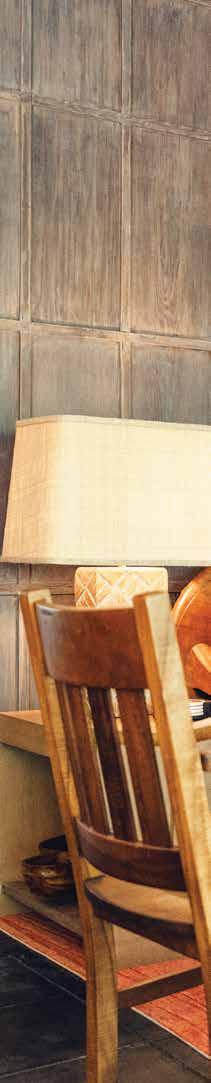

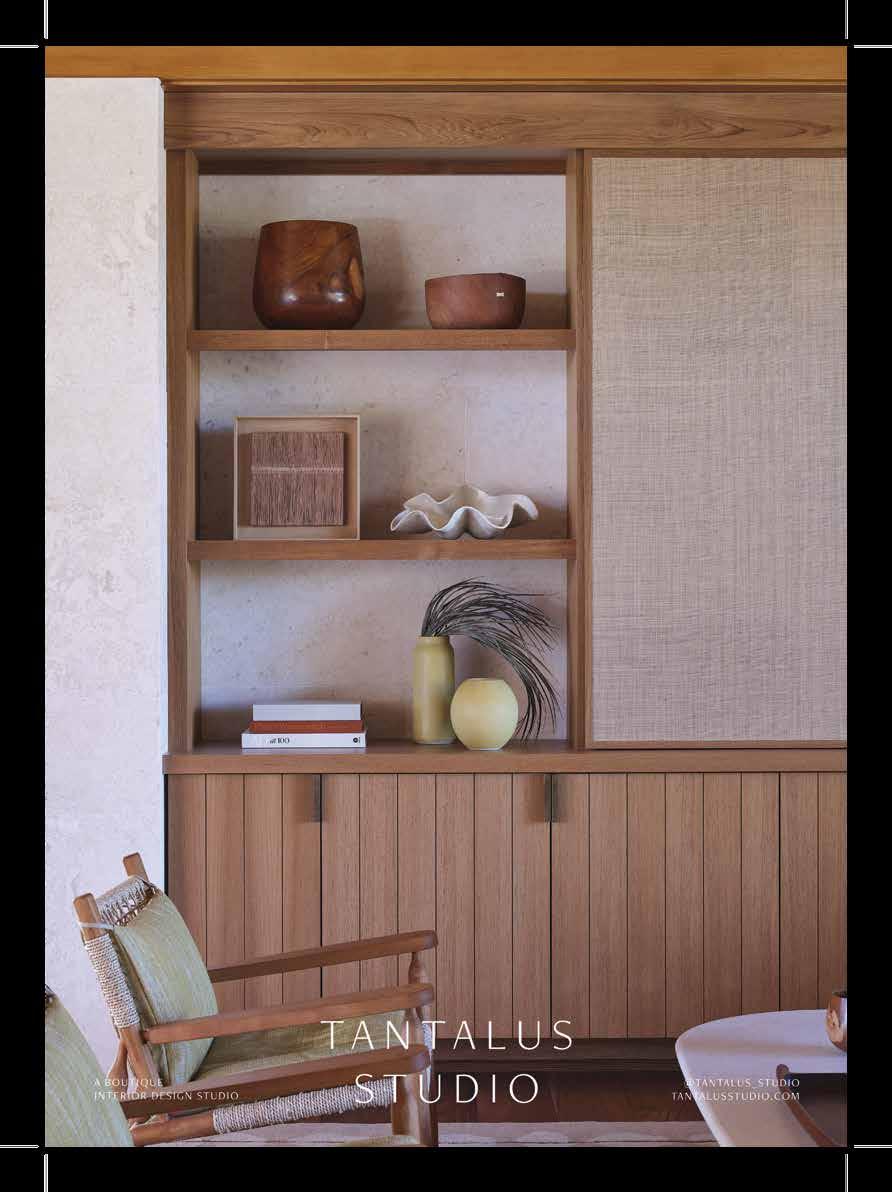

THE LAUNIU WARD VILLAGE AMENITY LOBBY

Matthew Beall owner & ceo

HL1 DIRECTORS

Josh Jerman R(B)

Noel Shaw R(S)

Erik Hinshaw R(B)

Neal Norman R(B)

Dave Richardson R(B)

Kahea Zietz

co - owner , vice president

HL1 MEMBERS

O‘ahu

Cedric Choi R(B)

Julianna Garris R(B)

Kaua‘i

Ben Welborn R(B)

Tiffany Spencer R(S)

Roni Marley R(B)

Amy Frazier R(B)

Lauren Pingree R(S)

Maui

Leslie Mackenzie Smith R(S)

Greg Burns R(S)

Brad MacArthur R(B)

Hawai‘i Island

Robert Chancer R(B)

James Allison R(S)

Steve Hurwitz R(B)

Beth Thoma Robinson R(B)

Jake Chancer R(B)

HL1 Members are listed by island and shown in the order they appear throughout this issue. ABOUT THE COVER

Anthony Arnold creative director

EDITORIAL PARTNERS

Jason Cutinella CEO & Publisher, NMG Network

Joe V. Bock Partner & General Manager, Hawai‘i

Lauren McNally Editorial Director

Taylor Niimoto Managing Designer

Matthew Dekneef Executive Editor

Eleazar Herradura Designer

Alejandro Moxey Head of Partnerships, Hawai‘i

Sabrine Rivera Operations Director

Martha Cheng Contributing Editor

A hīnano flower, photographed by Erica Taniguchi near the Marmol Radziner residence featured on page 52.

Aloha and welcome to the ninth edition of HL1 Magazine.

There’s a certain gravity to Hawai‘i. That pull—of land, culture, and context—shapes more than how you live. It shapes what you choose to build, what you hold onto, and what you let go. Attempting to describe those intangible qualities—the sense of place; historical significance; the built environment and its architectural relevance—is akin to describing gravity itself. Even if you understand it (somewhat) intellectually, it’s more felt than anything. And, it’s … relative.

In Issue 9 of HL1 Magazine, we find ourselves in a time of meaningful shift. The market is recalibrating—subtly in some places, more dramatically in others. It’s a fascinating moment, sometimes quiet, sometimes electric. I speak more to that in the HL1 Market Report, which offers a wide-lens view of luxury and ultra-luxury activity across the islands.

In Craft, we begin with the legacy of Mary Philpotts, whose vision helped shape the design language of Hawai‘i. Her family home in Nu‘uanu on O‘ahu remains a place of gathering and creative exchange—a living reflection of her values. We then travel to Kīlauea, where architect Ron Radziner and the homeowners share how clarity, intention, and restraint gave form to a deeply rooted modern home. And we visit the studio of Mark Chai, whose sculptural lighting draws inspiration from the natural rhythms of the islands.

In Discover, we explore what it means to connect with Hawai‘i in ways that are elemental and visceral. From conservation-focused hunting tours, to the long restoration of Waihe‘e Refuge,

to opera singer Laurie Rubin’s work increasing access to the performing arts at Ohana Arts, these stories reflect presence, care, and a deep sense of relationship with place.

In Showcase, we share select listings from the HL1 Collection— homes that speak not only to place, but to perspective. Distinctive, design-forward, and deeply considered, these properties offer something more than beauty—they offer resonance. Like many of the homes we’ve had the privilege to represent in previous editions, some of these will set the market, not follow it.

As always, HL1 is a reflection of the relationships, ideas, and values that move us. Whether you’re a client, collaborator, or longtime reader, we hope this issue offers a sense of connection—to Hawai‘i, and to something lasting.

Enjoy, Matthew G. Beall Owner & CEO, Hawai‘i Life

HAWAI‘I LIFE ONE LUXURY MARKET REPORT

Sales and trends in Hawai‘i’s high-end real estate market.

INTRODUCTION

Hawai‘i isn’t for everyone. As any of us who are fortunate enough to call this place home are keenly aware, there’s a certain gravity to Hawai‘i. It either sucks you in, or it flings you out.

It’s arguably one of the most exclusive places on the planet, especially in the context of real estate. It may not be a coincidence that the most geographically remote location on Earth also has the highest home prices in the United States.

Despite escapist fantasies to the contrary, however, Hawai‘i is not a place to disappear or to avoid the problems affecting the rest of the world. It’s a high-context relationship culture, with a very different set of values than a lot of the Western world. This is precisely why the people who belong here know it when they feel it.

The pandemic brought an onslaught of new faces to Hawai‘i, all during a time of relative panic, which led to impulsive purchase decisions. Many of us expected—some may have even hoped— that many of these new residents would realize Hawai‘i wasn’t for them. That expectation may have been short-sighted. These weren’t vacation-home buyers. They enrolled their kids in schools. They got involved in their local communities. They got sucked in.

It’s nearly impossible to truly describe the benefit and fulfillment that comes from having active relationships with the ocean, the land, and the people here. Of course, even the most transient visitor can enjoy surf sessions, hikes, farm tours, and innumerable outdoor activities. But when the experience of those activities transcends the superficial and becomes an actual relationship with this place and its people—that’s where real ontological magic happens.

Along the way in the last few years, mortgage interest rates spiked, leading to a “lock-in” effect for many homeowners. Remote work has become more of a reality than pundits predicted. Volatility in the stock market and global economies has led to drops in consumer confidence.

As a result, the years following the pandemic were among the slowest years in the state’s real estate market since the Great Recession.

Several years on, we may be seeing the shakeout that many anticipated following the pandemic—a noticeable rise in inventory across Hawai‘i’s real estate markets. On the islands, any uptick in inventory tends to stir echoes of 2008’s economic collapse. But the story this time is different. Much of the new inventory, particularly in the ultra-luxury segment, doesn’t represent financial distress or market-driven urgency. These properties are rarely primary residences. The decision to sell at this level often reflects changes in lifestyle, personal priorities, or family dynamics, not economic hardship. Unlike the broader market, ultra-luxury real estate moves to a different rhythm.

If you’re tuned in, you see the opportunities. Quiet shifts are changing how the luxury and ultra-luxury markets are behaving, recalibrating old paradigms. And with shakeouts come golden opportunities. A convergence of factors is opening the door for once-in-a-lifetime acquisitions. We’re seeing buyers start to grasp that, whether intentionally or through unintended discovery. Estates are changing hands, some for the first time in history, and the moment is now. This isn’t a fire sale, but rather a quietly compelling window for those who know where and how to look. In Hawai‘i’s luxury market, you rarely get the same opportunity twice.

METHODOLOGY

For the purposes of this report, we refer to the “luxury market” as the market for homes and condominiums listed for sale at or above USD 3 million, and the “ultra-luxury market” as properties listed at or above USD 10 million. While these are certainly broad metrics, viewing the data over time provides context for the activity in each segment. That context can better inform the acquisition or disposition decisions of our clients, which is our goal.

Prices in the HL1 Collection are rounded to the nearest tenth of a million for consistency. Figures are based on recorded or listed prices.

A Note on “Luxury”…

The word “luxury” may well be one of the most bastardized words in the English language, to such a degree that it’s almost devoid of any real meaning. We recognize how subjective “luxury” is, and there may well be luxury properties that are not accounted for in these two data sets. Certainly, not every home in these brackets is truly “luxury.” Indeed, many fall short. For the purposes of this report, however, we use this vernacular generally to make sense of the top tiers of Hawai‘i’s real estate markets.

OVERVIEW

“Sales

volume across nearly every luxury segment still exceeds prepandemic benchmarks.”

Since the pandemic, Hawai‘i’s luxury and ultra-luxury markets have certainly fared better than the real estate market at large. While definite similarities exist, the volume of sales activity in the luxury and ultra-luxury markets, measured against previous years, is much higher than in the broader real estate landscape.

Sales volume across nearly every luxury segment still exceeds pre-pandemic benchmarks. While not as robust as the frenzy of record-setting activity during those unprecedented years, it’s clearly higher than at any point prior to 2020. Meanwhile, the larger market is slower than at any time since the Great Recession. You might call this the Great Pause, unless you’re shopping above $3 million.

Meanwhile, the steady rise in luxury and ultra-luxury listing inventory is consistent with nearly every other market segment. We anticipated a relative shakeout of inventory after the pandemic. Well, that shakeout has arrived, due to the realities of remote work, changing lifestyles, and a host of other factors. As a result, the active listing inventory across Hawai‘i’s luxury and ultra-luxury market segments increased steeply over the past two years, gaining further momentum in 2025.

On Hawai‘i Island and Maui, for example, the inventory of luxury real estate listings are at their highest levels in history, with Kaua‘i and O‘ahu close behind.

These figures exclude “off-market” listings, which have also climbed. In many ways, “off-market” inventory has been a leading indicator of the overall inventory, in that the volume of “off-market” inventory in the luxury segments increased before the market at large, and it remains high.

Let’s be clear. More inventory equates to a broader set of opportunities, especially as asking prices begin to soften. Sellers are becoming more flexible, even despite overall prices holding strong.

Case in point: We’re currently representing some of the most extraordinary listings in the luxury and ultra-luxury markets, more than at any point in Hawai‘i Life’s history.

ON CONDOMINIUMS

Traditionally, the trendlines of condominium and single-family home sales went hand in hand. But something changed last year. Across the island chain, there has been a significant bifurcation in the two markets, and not in favor of condominiums. Volatility in the insurance market and potential legislative changes to vacation rentals have put downward price pressure on condominiums and led to a spike in inventory. Some of these properties are facing increased homeowners’ association fees, and some

may be impacted by looming legislation attempting to limit short-term rentals. Still, there are opportunities in both segments, especially in well-positioned condominium projects. What has softened for sellers may well translate to a sweet spot for the right buyers.

What has softened for sellers may well translate to a sweet spot for the right buyers.

ON HIGH-END RENTALS

While the broader luxury sales market is recalibrating, Hawai‘i’s toptier rental segment is showing notable strength. Demand has remained remarkably consistent, even as the “revenge travel” wave has settled elsewhere.

A new group of seasoned travelers is driving this trend. They tend to be less price-sensitive and more focused on experience, seeking fully serviced stays

in premier locations. For these guests, Hawai‘i Life’s concierge team routinely arranges private chefs, personal trainers, curated excursions, and other elevated services that go well beyond the basics.

In Hanalei Bay on Kaua‘i’s North Shore, rental revenue growth has been especially pronounced. Since 2019, properties there have seen increases ranging from 108 percent to 214 percent, with one standout home recording an 885 percent rise in rental income. On Maui, the resort community of Wailea continues to perform at the highest level, seemingly buffered from island-wide headwinds and pending legislative changes. In 2025, a penthouse unit in Wailea commanded rates more than double those seen just two years earlier.

This strength isn’t solely about demand. It also reflects the strategic rate management and deep market insight of Hawai‘i Life’s rentals team. In this segment, success depends as much on timing and positioning as it does on the property itself.

What defines a truly exceptional rental today goes beyond location (though proximity to the ocean remains a near-constant). Homes that perform well as rentals often feature newer construction, refined design, upscale furnishings, and private amenities such as spas, saunas, cold plunges, or pools.

Buyers are continuing to explore more flexible ways to engage with Hawai‘i real estate. And as they do, the high-end rental segment is becoming an increasingly important part of the broader luxury market landscape.

Maui is among the most complex and nuanced real estate markets in the State of Hawai‘i at present time. The market faces industry headwinds of high mortgage interest rates, equity market volatility, tariff whiplash, and fewer international visitors, alongside the long recovery process from the 2023 wildfires and related political and economic ramifications.

But there is a caveat to every market indicator on Maui. We’re past the point of “how it’s always been.” Maui is in a new era. While the overall trading volume in the Maui real estate market at large is at its lowest level since the Great Recession, an outsized portion of that sales volume has come from the luxury and ultra-luxury market segments, where activity is higher than even pre-pandemic years.

Active listing inventory of luxury and ultra-luxury real estate are at their highest levels in Maui’s history. While sales in these segments remain higher than in the pre-pandemic period, the significant increases in inventory are beginning to create downward price pressure. Ratios of sales price to listing price are also beginning to drop, as the average days on market for most listings have increased.

Despite the broader market slowdown and outsized inventory, the luxury and ultra-luxury segments are holding their own. But make no mistake, momentum is tilting toward buyers. We shouldn’t mistake this for value evaporating, but rather leverage shifting.

CASA EN MAUI

$28.6M

HL1 MEMBERS: MATT BEALL R(B), JOSH JERMAN R(B) & LESLIE MACKENZIE SMITH R(S)

24 COCONUT GROVE LN #24, LAHAINA, HI

$5.1M

HL1 MEMBERS: GREG BURNS R(S)

The luxury condominium market on Maui is even more dramatic on all fronts. A proposal to phase out vacation rental use of approximately 6,000 units, referred to as the “Minatoya List,” rattled the condominium market significantly. The proposal triggered historically high spikes in Maui condominium listing inventory. In the luxury segment, there are now nearly twice as many condominium units listed for sale than the average of the pre-pandemic years.

And this is where the whiplash comes in. Despite these headwinds, sales volume for luxury condominium units remains higher than pre-pandemic levels. There is still demand, buyers still value the quintessential beachside condo lifestyle, and they may be sensing opportunity amid the changes. Sometimes the best moves happen right before the dust settles.

These nuances create a delicate dance between timing and potential. Ultra-luxury properties that have never before been on the market are becoming available. Hawai‘i Life represented both the seller and the buyer in the listing and sale of Casa En Maui, a beachfront home on South Maui’s Keawakapu Beach which sold for $28,560,000. NOTABLE

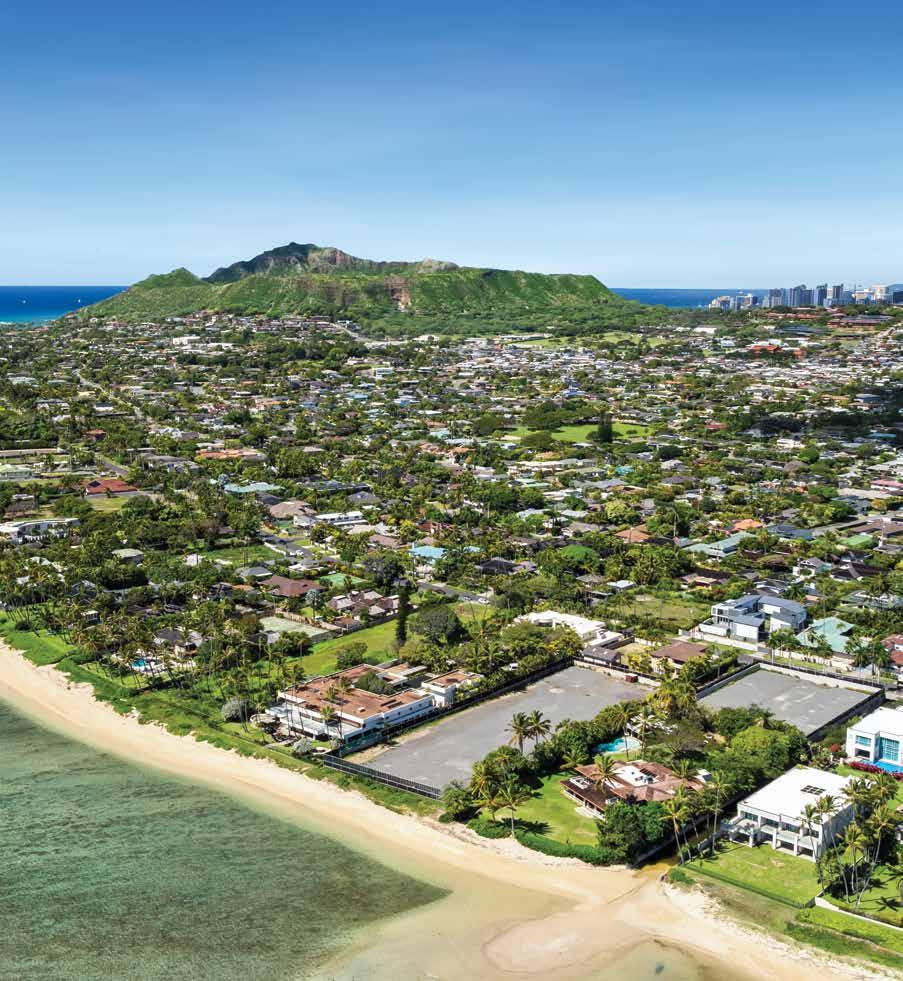

Rarity drives desire, and nowhere is that more evident than on O‘ahu. The island’s luxury and ultra-luxury housing stock is generally older than its neighbor-island counterparts, making modern construction and new remodels extraordinarily valuable and relatively rare. O‘ahu represents just over half (about 55 percent) of the total real estate market in Hawai‘i. But it has the lowest share of out-of-state buyers— approximately 10 percent for single-family homes and 20 percent for condominiums.

O‘ahu’s market has historically been more impacted by foreign buyers, especially from Japan and other Asian countries, than the neighbor islands. During the pandemic, these overseas buyers dropped off significantly, for a host of reasons. International travel ground to a halt during those years. Exchange rates between the U.S. dollar and the Japanese yen have remained unfavorable for Japanese buyers. International arrivals to Hawai‘i have been steadily decreasing, with doubledigit declines in the first part of 2025, even when compared to a slow 2024.

O‘ahu’s luxury and ultra-luxury markets are their own unique ecosystem, largely due to inventory constraints. Listings have climbed since 2022, but only one segment has hit a record high inventory: ultra-luxury condominiums, fueled by a combined wave of both newly completed and underway developments in Honolulu.

Howard Hughes and Discovery Land Company are partnering on a new ultra-luxury condominium project with a private club element. Congruently, The North Shore Club at Turtle Bay, another private club development, is underway. Both properties are drawing buyer attention and feeding a familiar appetite. When it’s new, it moves.

Making the right move on O‘ahu is about selection. For buyers seeking rarity, modern design, and long-term hold value, the island offers a tight lane—but one worth running.

“O‘ahu’s luxury and ultra-luxury markets are their own unique ecosystem …”

NOTABLE SALES

4823 KAHALA AVE, HONOLULU, HI

$65.8M

HL1 MEMBER: NOEL SHAW R(S)

4679B KAHALA AVE, HONOLULU, HI

$15.4M

HL1 MEMBERS: CEDRIC CHOI R(B) & JULIANNA GARRIS R(B)

“It’s less about casting a wide net and more about being in the right current.”

KAUA‘I

Kaua‘i is off doing its own thing—nothing new. As the smallest market of Hawai‘i’s four largest islands, Kaua‘i is a little more idiosyncratic than even the neighbor islands of Maui or Hawai‘i Island. The luxury and ultra-luxury markets were, of course, dramatically impacted during the pandemic, with historic sales volume and activity. The years following were correspondingly quiet in both segments.

Kaua‘i’s inventory increase is slower than the other islands, and it’s not straight across the board. Aggregate luxury inventory reached record levels at the beginning of 2025, but inventory in the ultra-luxury segment is actually lower than even pre-pandemic years. Only 12 homes listed for sale are at or above the $10 million mark.

If Kaua‘i is the lagging indicator in the pandemic-era surge shakeout, then we can expect inventory to keep building in the coming months. It’s unlocking rare opportunities for trades that don’t often come up in this market. On Kaua‘i, it’s less about casting a wide net and more about being in the right current.

NOTABLE SALES

2727 KAUAPEA RD, #A, KILAUEA, HI

$6.8M

HL1 MEMBERS: BEN WELBORN R(B) & TIFFANY SPENCER R(S)

2620 KAUAPEA RD, #A, KILAUEA, HI

$20M

HL1 MEMBER: RONI MARLEY R(B)

3704 ANINI RD, KILAUEA, HI

$5.9M

HL1 MEMBER: AMY FRAZIER R(B)

NOTABLE SALES

62-3768 KAUNAOA NUI RD, KAMUELA, HI

$10M

HL1 MEMBERS: ROBERT CHANCER R(B) & JAMES ALLISON R(S)

HAWAI‘I ISLAND

Hawai‘i Island has quietly outpaced the rest when it comes to luxury and ultra-luxury sales. The quality of the inventory on Hawai‘i Island is generally quite high, with newer projects and construction concentrated in and around the Kohala Coast resorts.

While luxury market inventory on Hawai‘i Island peaked in early 2025, it didn’t reach the highs of the pandemic years, nor did it break records the way other islands have this year. Even so, sales volume in both the luxury and ultra-luxury segments remains strong, well above pre-pandemic norms.

Ultra-luxury inventory is at a record-high level, however, with as many as 25 homes listed at or above the $10 million mark in early 2025.

Luxury condominiums have also seen a dramatic spike in inventory, although sales activity in that segment is outpacing the rest of Hawai‘i. When we consider that there are fewer condominium projects impacted by insurance premium increases on Hawai‘i Island, and less legislative pressure related to short-term rentals, it makes sense.

The permit-processing time for a single-family home on Hawai‘i Island is shorter than any other island, which bodes well for both new construction and remodel permits.

61-150 KAMAHOI PL #39, KAMUELA, HI

$8M

HL1 MEMBERS: JAMES ALLISON R(S) & STEVE HURWITZ R(B)

UNDERWHELMING & OVERPRICED

As it turns out, A.I. isn’t the only thing that’s subject to hallucinations.

As listing inventory grows in Hawai‘i’s “luxury” market, we’re confronted with a painful reality: A lot of that inventory is both overpriced and, more importantly, underwhelming—especially to prospective buyers. The median age of a home in Hawai‘i is 44 years old, and it often shows. Countless homes need significant updates, if not full-scale remodels.

Construction permits in Hawai‘i take approximately three times as long as the national average. Single-family home permits can take a year or more to process. Import tariffs will likely drive up the cost of construction materials and appliances.

The great majority of prospective buyers for Hawai‘i’s luxury real estate market are coming from out of state. Even the most ardent of them are aware of the realities of organizing a construction project from afar.

Many sellers, however, are still basing their pricing on the pandemic-related surge that occurred in the market, despite

the market’s subsequent contraction and the evolution in buyer sentiments. We understand wanting to hold onto the pricing run that sellers experienced during the surge, but that ship has sailed.

Indeed, the real estate market in Hawai‘i during the pandemic broke every historic record possible: overall trading volume, units sold, remarkably short days on market, bizarrely short escrow periods, record-pricing, and more.

But that was years ago. Since then, the margins between listing prices and sale prices have continued to drop significantly across the island chain, all while inventory continues to increase. A lot of that inventory is … well, not great, resulting in a price-value disconnect.

“Taste” also plays a role here. The fashion of architecture and interior design changes more rapidly than Hawai‘i’s construction market can keep up with, and the demographics and psychographics of buyers have shifted as well, especially among the off-shore set.

Immediate gratification is in more demand than ever. Let’s just say that the appetite for project homes is on a strict diet. This dynamic bodes well for new development projects, but it also results in a highly competitive environment for “new” homes.

ON AUCTIONS

We’ve conducted innumerable auctions of luxury real estate over the years. (Full disclosure: I sit on the Board of Advisors for Concierge Auctions, with whom we’ve exclusively conducted dozens of auctions since they were founded in 2008.)

Luxury real estate auctions are triggering for brokers.

Nothing stirs up the “coconut wireless,” especially among real estate brokers, as much as luxury property auctions.

Despite market evidence to the contrary, many brokers and agents still jump to the conclusion that auctions mean desperation. That opinion is amplified by the general sense of insular provincialism that’s rampant in Hawai‘i real estate. Especially since auction companies need to have a broad international reach to be truly effective. This beckons notions of “interlopers” coming from afar and somehow shaming the apparent inefficacy of real estate brokers and agents.

The market, however, is set by buyers and sellers, not brokers or real estate agents. The only answer to whether or not an auction was “successful” is if, in fact, the property sold at auction. But that simple formula is often lost on brokers who wish to bend the market to their own will.

I get it. When Concierge Auctions first started doing business in Hawai‘i, I, too, treated them with a stiff arm that would make even the Heisman Trophy proud. But that was during the Great Recession. At the time, it was difficult not to attribute some sense of extreme market pain to a seller’s decision to go to auction.

But that stigma is long gone. And whether real estate brokers realize it or not, buyers and sellers certainly do.

Real estate is not a liquid asset, especially in the top tiers of the market. The great majority of buyers, especially for the top quartile of Hawai‘i’s real estate, come from off-shore. They don’t reside on the islands. They arrive seasonally, and their

The market … is set by buyers and sellers, not brokers or real estate agents.

reasons for visiting Hawai‘i have little to do with the presence of a particular real estate listing. Instead, they’re arriving on their schedule, which may or may not be seasonal. Rather, it is influenced by school breaks or holidays or unfavorable weather elsewhere. It could be that they’re not even looking for a real estate acquisition—the timing just happens to be right, and something catches their eye.

The result is that conventional assumptions about days on market simply don’t apply to the great majority of high-end real estate in Hawai‘i. Sellers are quite literally waiting for someone to get off a plane. When we’re hired to market and sell a property in the uppermost bracket of the market, we have to be prepared for that reality and budget our resources and expectations accordingly.

But what if a seller doesn’t want to wait? What then?

That’s where auctions come in—when sellers want to control the timing of their sale, generate some semblance of fear of loss in the market, and issue a clear call to action tied to a deadline.

It’s not complicated, and it has nothing to do with the efficacy of listing brokers. Marketing luxury real estate in Hawai‘i requires the endurance of a marathon runner. By contrast, auctions are a 40-yard dash. The variable is the time value of money.

Auctions are not for every seller. But for those who have a timesensitive plan for their proceeds, they’re effective.

ON.

OFF. PRIVATE. PUBLIC…

“On Market”

“Off-Market”

“Private Listings”

“Public Listings”

Who can keep up? …

I’ve written for years about our growing inventory of listings that aren’t included in the Multiple Listing Services (MLS) and the variety of motives our clients have for taking this approach. It’s not exactly a secret.

Despite the obvious difference in market exposure of those listings, many of our clients have valid and varying reasons not to list their properties in the MLS or on countless public-facing websites. I don’t need to repeat them here.

This issue, however, has been the source of exhaustive intraindustry debates among real estate professionals, tech executives, and pundits embroiled in vitriolic arguments about MLS policies related to “off-market” listings. All of this is on the heels of and further fueled by the National Association of Realtors settling a massive class-action lawsuit in 2024, related to the way in which brokers are compensated. (The result of which is utterly simple: Buyers’ brokers are compensated by buyers, and sellers’ brokers are compensated by sellers. Riveting stuff.)

Self-interested parties (tech executives, CEOs of MLS organizations, owners of giant publicly traded real estate companies) have all weighed in, complete with hyperbolic absurdity.

While we’ve had (a lot of) success in marketing and selling private listings, the decision for any seller is nuanced. Any decreased market exposure (i.e., withholding a listing from the MLS) may negatively impact the ultimate selling price of a property, as well as the timing of the sale. As the policies governing “off-market” listings are changing in real-time, we’re available to describe their implications in detail with any of our clients. Our commitment is for our clients to be extraordinarily well-informed. From there, we take their instruction, not the other way around.

At present, we’re listing more luxury and ultra-luxury real estate than at any point in the firm’s history, both for “off-market” listings as well as properties that are listed publicly.

FORBES GLOBAL PROPERTIES

In 2021, Hawai‘i Life joined a partnership with Forbes Media and a small group of other independent brokerages from around the world to develop Forbes Global Properties. The idea was to leverage the reach of Forbes Media’s 100-year history and worldwide audience on behalf of a members-only network of distinguished real estate companies around the world.

Somewhat surprisingly, especially given the real estate market’s turbulence in recent years, Forbes Global Properties has seen phenomenal growth and is now in 23 countries (and growing) around the world. The mandate is quite different from that of a publicly owned company or a large franchised operation. The primary driver for growth isn’t market share or sales volume, but rather a sense of quality representation capacity for the top tiers of key real estate markets around the world.

It’s working. By virtue of the relationships we’ve built with Forbes Media and the brokerages selected from around the world, we’ve sourced an entirely new and robust referral channel, especially for the ultra-luxury market. We’ve also built a network that we can leverage on behalf of our clients who may wish to venture into another market.

FORECAST

Markets tend to overreact, and Hawai‘i’s luxury and ultraluxury real estate markets are no exception. Part of the reason for the regular comparisons to the “pre-pandemic” market is an attempt to look back to a time of relative normalcy, and perhaps even some degree of predictability, both of which may have long passed.

Hawai‘i’s luxury real estate markets are still reeling from the impact of the pandemic. The shakeout we predicted during that market run is finally here, and while it was slower to develop than we may have anticipated (especially from a trading volume standpoint), the spike in inventory has come on quickly in 2025.

Along the way, equity markets have seen dramatic volatility, enough to leave investors feeling dizzy and not exactly certain about the markets’ future prospects. Even though luxury real estate should generally be considered more of a consumptive purchase than an investment, per se, general uncertainty in financial markets complicates planning and long-term investment considerations, for businesses and individuals alike.

As a result, a lot of prospective buyers of luxury real estate are understandably “pressing pause.” But not all of them—Hawai‘i’s luxury and ultra-luxury markets are still trading at a much higher pace than even the “normal” pre-pandemic years. Some buyers are taking advantage of the increased inventory and the options it offers. Many are bullish, as are we, about the long-term value of Hawai‘i real estate. Some are “buying the dip.”

“Hawai‘i’s luxury and ultraluxury markets are still trading at a much higher pace than even the “normal” prepandemic years.”

That “dip” may not have fully played out yet. Price contractions are usually a lagging indicator of market realities. Median prices during the Great Recession, for example, didn’t drop in earnest until the period between 2010 and 2012, years after the recession was well underway.

Even though trading volume remains surprisingly high in the luxury and ultra-luxury segments, inventory in most of the markets is at record levels. Simple supply-and-demand dynamics will likely lead to further price contractions, which have already started in many of the islands’ markets.

The margin between sales prices and listing/asking prices is also continuing to widen, indicating that sellers are more willing to negotiate.

Even with a contraction in listing and sale prices, we don’t expect prices to settle back to pre-pandemic values, even if or when they’re adjusted for inflation. The market flurry that happened during the pandemic may have been an overreaction of its own, but it anchored a very real value perception for luxury real estate that is not likely to fully reset. There are, however, still innumerable aspirationally priced listings in the market, which will need to soften before they trade.

More sellers are electing to auction their properties than during “normal” market conditions, which is itself an indication of market sluggishness. These auctions represent current opportunities in the market and are an indication of more opportunities to come.

CLOSING

Patience is a virtue in times of market transition. For those considering a purchase, the coming quarters will present a lot of opportunity, perhaps even into 2026. For sellers, pricing is the predominant driver in a contracted market with high inventory.

The market is sobering up. And in that sobering, we’re seeing smarter moves, clearer pricing, and rare properties quietly changing hands. Not out of panic, but timing. For the right buyer or seller, that timing might just be now.

Hawai‘i’s appeal shines through. As the landscape shifts, we’re focused on what doesn’t change: the enduring value of place, timing, and informed decisions. For those paying attention, that’s where the real opportunity lives.

A LIFE BY DESIGN

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON

IMAGES BY MICHELLE MISHINA

The legacy of late interior designer Mary Philpotts McGrath reveals the fruitfulness of taking care in work, art, and life.

Off a quiet street in Nu‘uanu Valley is the entrance of ‘Āhuimanu, the final home of the late Hawai‘i interior designer Mary Philpotts McGrath. Its driveway, lined with palapalai and bromeliads, passes between a hedge and over a burbling ‘auwai (canal) before revealing a lawn shadowed by angel’s trumpet flowers and a monkeypod tree. The intimate courtyard entrance, which features a cherubic water fountain and colonnade, enchanted Mary at first sight, as did the salmon-hued plaster exterior that recalls the architecture of the Mediterranean.

Built in 1924 by architect Hart Wood for Dr. Gideon M. Van Poole, the home blends Mediterranean, Colonial, and Renaissance influences, reflecting Wood’s attempt to integrate classical architectural forms into a distinct Hawai‘i aesthetic. When the house came onto the market for only the second time, in 1992, Mary had just remarried and owned a house in the nearby Dowsett Highlands area. Her daughter, Marion Philpotts-Miller, decided to tour it with childhood friend Poppy Hopper and family friend Pegge Hopper and invited Mary to tag along. “The four of us walked into the driveway, and it was like my mom fell over, she was so enchanted,” Marion recalls. Mary and her second husband, John McGrath, promptly sold their home to buy the place, spending many hours gardening and hosting gatherings there.

“My mom had the graceful ability to hold space for the people in her life, whether they be family, friends, clients, partners, collaborators, peers, as well as our greater community,” says Billy Philpotts, Mary’s younger son. “A testament to this conviction was her choice to name her property ‘Āhuimanu, [meaning] ‘where the birds gather.’” The name is also an homage to the Macfarlane family farm in Kahulu‘u, also called ‘Āhuimanu, where Mary’s mother, Muriel Macfarlane Flanders, spent many of her childhood summers.

Mary grew up on O‘ahu with her three sisters, except for a brief period during World War II when they lived at a convent in California. Her childhood home was a Pali Road house in Nu‘uanu designed by midcentury modern architect Vladimir Ossipoff, who later became a collaborator and family friend. “Our feet were stained black with mud from trapping crayfish in the stream and picking gardenias by the armful in the backyard,” writes Mary’s sister, Alice Flanders Guild, of their mountain valley upbringing. Mary also chose to raise her three children, Douglas “McD” Philpotts, Marion, and Billy, in Nu‘uanu with her first husband, Douglas Philpotts.

In all her homes and professional projects, Mary wove art into every space. At ‘Āhuimanu, this included works by Madge Tennent, John Kelly, Arthur Johnson, and Paul Jacoulet, along with a set of five portraits of family matriarchs she often draped with maile lei. At their center is Mary’s great-grandmother Abigail Maipinepine Bright, who married businessman James Campbell. To Abigail’s left is Mary’s grandmother, Kamokila Campbell, with Kamokila’s sisters completing the group. In the dining room is a koa cabinet made for

Family portraits hang above wooden calabash, or bowls, which can be found throughout the home, and furniture that came with the Nu‘uanu property.

Kamokila by James Campell. “My mom came from an art background, but my grandmother had amazing taste, so she was exposed to it,” Marion says.

Mary’s ancestry hints at the rich creative and cultural influences that manifested in her career and life. To call her an interior designer, while accurate, is only part of the story. She was also an entrepreneur, artist, mentor, and a matriarch of her family and community. Through the decades, her abundant energy and attention shaped the ambiance of countless homes, resorts, and businesses in the islands. Her interior designs artfully layered cultural Hawai‘i references with an emphasis on local craftsmanship and art, creating a signature Philpotts aesthetic. As she writes in the introduction of Hawai‘i, A Sense of Place: Island Interior Design by Mary Philpotts McGrath with Kaui Philpotts, “The best contemporary Island interiors

use design elements essentially unchanged for hundreds of years, showing respect for these elements and for the people who inhabit the rooms.”

‘Āhuimanu embodies this approach. The house came with antique furniture, wood-paneled walls, even a large marble garden sculpture, all of which she embraced. In the airy living room with an ‘ohiawood floor, an ornate Italian mirror contrasts with shelves of wood bowls and a contemporary couch. A lauhala mat and wrought-iron coffee table from the Royal Hawaiian center another seating area. Flowing from the living room is an enclosed lānai featuring two designer Gump’s tables and a Henry Weeks bench. There is a nook anchored by an ‘uluwood board, originally used to carry roasted whole pig, that Mary converted to a coffee table and put alongside a vintage Gump’s chaise lounge and classic Pegge Hopper painting of a Hawaiian woman in a red mu‘umu‘u reclined over a pink background. Each space has a moment, whether it’s the large daybed in the kitchen or the lush back lawn that overlooks the Nu‘uanu Stream, where her children remember playing as youth.

After graduating from Punahou School in 1955 and briefly attending the University of Colorado Boulder, Mary returned home and completed her fine arts degree at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. There, Mary developed a deep bench of mentors, studying with professor Kenneth Kingrey and artists Jean Charlot, Ed Stasack, J. Halley Cox, and Harue McVay and spending time with art scholar Dr. Gustav Ecke, who was her neighbor. This influence informed Mary’s philosophy that culture and art are the backbone of good interior design, which she carried through her life.

My mom had the graceful ability to hold space for the people in her life.

Mary founded Philpotts Interiors in the 1960s under the name Creative Decorating with her friend Allison Holland. One of their first major jobs was for The Pacific Club, a Honolulu club that at the time was for men only, which they landed through a recommendation by Ossipoff. “If you think about it, during her professional career, it was a man’s world,” Billy says. “If you’re going to go in and do a corporate office downtown for a big law firm, to be on a peer-to-peer level with your clientele, you’d be dealing with men. I’m sure she got challenged, but she never let it phase her to the point of giving up.”

While building her business and studying for the American Society of Interior Designers exams, Mary also nurtured her children’s artistic inclinations. McD, her eldest son, who was born in 1958 and grew up to be a talented woodworker and craftsman, remembers his mom teaching art to him and other neighborhood kids during summer break, including how to make prints from fish he caught. Marion recalls the yellow-and-orange patterned wallpaper in her childhood bedroom, which she selected from samples Mary brought home for her. Douglas Philpotts, McD and Marion’s dad, was a banker but also a builder. “They were both makers at heart,” says Marion, who remembers her parents sitting at the kitchen table with an old adding machine, crunching numbers for Mary’s growing business.

Mary Philpotts McGrath’s children read a poem she wrote for her Philpotts Interiors team titled “Tree of Life,” which begins, “In another life I want to be / a tall and graceful coco tree.”

In 1981, Mary renamed Creative Decorating to Philpotts & Associates Inc. as the firm gained momentum. An early project she later revisited was Kona Village Resort, where she may have been the first to showcase the work of Pegge Hopper, her neighbor who became a renowned artist and gallery owner. Mary left her fingerprint on a wide range of interiors, from the Hawai‘i governor’s home to Moloka‘i Ranch, where her attention was so meticulous she nailed cowboy boots to the floor to suggest the presence of paniolo. Her touch is so recognizable that when Billy attended a wedding at Fairmont Orchid in Waikōloa Village, he knew immediately his mom had designed the interiors.

By the time Billy later joined Philpotts Interiors in 2002 as director of operations, the firm had grown to 45 employees. Under the guidance of family members and longtime leadership, the company continues to flourish. Marion joined Philpotts

Interiors from San Francisco in 2001 as a senior designer and later became a managing partner. Billy now serves as chairman of the board, having handed off operations to Mary’s grandson Kainoa Philpotts. Kainoa’s wife, Arianna Philpotts-Blasco, is an architectural designer there. Marion’s daughter Maree Miller is operations manager at the floral company Bloom, one of two businesses started by Philpotts Interiors alongside the design atelier Place. Even in semi-retirement, Mary remained involved, chiming in on everything from Bloom to the interiors of Aulani, a Disney Resort and Spa. “It’s so interesting working for a firm that has such a longstanding legacy and one that involves your family member,” Kainoa says. “I feel as though I learn things about [my grandmother] and her career every day or week.”

Mary was a natural collaborator and mentor. One artist who became like family to Mary was Doug

Mary and artist Doug Po‘oloa Tolentino named the printing press at her ‘Āhuimanu studio “‘Ō‘ō” after the extinct black honeyeater that once frequented Nu‘uanu, a word that also reflects the physical process of printmaking.

Po‘oloa Tolentino. They met through family on Maui in the 1980s, as they share Maipinepine lineage, but it wasn’t until around 2010, when they both enrolled in a lithography class at Linekona School, that they reconnected over artmaking. Mary converted her garage into a printmaking studio and invited Doug and other artists to use the space. “She automatically gave me the feeling that she wanted to impart some of her knowledge and her experience, her mastery of the printmaking, and her design ideas,” Doug says. “She was an expert in design and abstractions, and I was good with figural representations, so she felt we could

do something together.” The two collaborated on a number of prints, including one of Pele, a tribute to Mary’s grandmother and Doug’s wife’s grandmother, who were best friends and revivalists of the culture of Pele.

Mary’s hospitality toward artists was at the heart of ‘Āhuimanu. Kainoa remembers boisterous gatherings there as a child and quieter moments in his adulthood. “Everyone has a detailed memory of who she was or how much she cared about one particular aspect of their lives,” he says. “She would pick up on things that most people would pass over. And I think that was her talent as a designer as well as a friend and family member.”

Mary also contributed to civic organizations around O‘ahu, including Honolulu Printmakers, Ballet Hawai‘i, Assets School, and Hawai‘i Land Trust. A multigenerational member of Outrigger Canoe Club, she became its first female president in 1998. She even helped establish the Washington Place Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the historic governor’s residence, with First Lady Vicky Cayetano. “Mary was instrumental in making sure that the people of Hawai‘i had access to Washington Place,” Vicky is quoted in Mary’s obituary, “so they could learn more about the legacy of Queen Lili‘uokalani and the role Washington Place played in Hawai‘i’s history.”

‘Āhuimanu is yet another project Mary poured herself into, according to McD—and, significantly, her last one. The home is a manifestation of her lifelong creativity. “My parents, they were the original flippers,” McD recalls. “They took houses and made them the best on the block before they moved

out.” When she and Douglas were selling their Pali home, McD remembers people were eager to own it because it was a piece of art, “a Mary house.’”

Interiors are, by their nature, personal and adaptable. They are adjusted to reflect new occupants, trends, and ways of living. At their best, they benefit and delight those within while continuing the story of what came before. While the physical legacy Mary created may diminish, as walls are re-papered and furniture is replaced, Mary’s imprint on the aesthetic of Hawai‘i interiors will remain. Her legacy also endures in the people she employed, the artists she uplifted, the organizations she empowered, and the family she shaped. Even after Mary passed in 2023, Philpotts Interiors continues to inform, and be informed by, the aesthetic of life in Hawai‘i.

Or, as Mary once wrote: “Hawaiian living is a state of mind. At its best, it’s living with the spirit of aloha—with harmony and affection for others, with cool breezes, bare feet, and the smell of flowers.”

SHELTER AND FLOW

TEXT BY LEILANI MARIE LABONG

IMAGES BY ERICA TANIGUCHI

On Kaua‘i’s north shore, trade winds, volcanic stone, and a modernist’s touch shape a home that’s as intentional as it is elemental.

Seeking more sunny days than rainy ones on Kaua‘i’s famously drenched north shore, Los Angeles-based celebrity business manager Michael Karlin strategically built a vacation home on the island’s northeastern corner. By the time the trade winds reach the low-lying town of Kīlauea, they’ve shed much of their moisture and downshifted in gusto, thanks to the inland mountains bearing the brunt.

Even so, Kīlauea’s “drier” microclimate averages 60 to 80 inches of annual rainfall, which is still sopping, even for Hawai‘i, but considerably less than the 80 to 100 inches that saturate the rest of Kaua‘i’s north shore. Having sojourned on the island for 25 years before building his own private getaway, Karlin has come to observe that the heavier rainfall starts “around the Shell gas station,” just two miles shy of his house. Along with his wife, Natalie, a jewelry designer, the couple is now naturally positioned to bask in more sunshine than most of their northern brethren.

“He chose a good spot,” confirms architect Ron Radziner of L.A. design firm Marmol Radziner, which has completed several residential projects across Hawai‘i and is known for quietly integrating

its modernist structures into highly atmospheric environments. The Karlins’ down-sloped oceanview perch certainly qualifies: facing west toward bursting sunsets and the emerald chisel of the Nāpali Coast, the 1.7-acre former field of sugarcane—a crop first cultivated in the area’s ironrich soil by the Kīlauea Sugar Plantation in the late 19th century—is just a half-mile south from Kīlauea Lighthouse.

Naturally, the architecture of the 4,500-square-foot new build, completed in April 2021 after two years of construction, takes some cues from Hawai‘i’s plantation vernacular. Radziner’s modern interpretation is like an arrow straight to his client’s logician heart. “As a numbers person, I like things to have a purpose,” says Karlin, a lifelong architecture buff who “always wanted a Marmol Radziner house” for its union of style and substance. “I don’t

want to look at something and wonder, ‘Why did they do that?’”

The home’s long, linear form and crisp lines are visually tidy and seem to echo the horizon in the distance. A simple gable roof features deep eaves for protection from the elements. “You need big roofs in this part of the world,” the architect says. While the street-facing facade sits on level ground, the back is raised on piers to accommodate the slope, to account for occasional flooding, and to maximize views from the central lānai and the spaces that flank it, namely the primary bedroom and Karlin’s office. To conceal the understructure, Marmol Radziner, who also designed the landscaping, wrapped the home’s base in tropical flora such as pink ginger, Samoan dwarf coconut palm, and banana trees. “The house looks like it’s floating above a wild garden,” Radziner says.

The home is on a picturesque perch half a mile south of Kīlauea Lighthouse.

Turns out Kīlauea has an architectural style all its own. In 1926, sugar plantation manager L. David Larsen built houses of fieldstone, specifically basalt. Many of those masonry structures still exist, including his Kuawa Road estate, whose ground level was built of the same material. Nearly a century old, the home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

“There’s nothing like building with something that truly belongs to a place,” Radziner says. “If I could do anything in Hawai‘i, it would be to design a house with all solid walls of lava rock.” That personal ambition may one day materialize on his family’s property farther up the shore near Hanalei, but at the Karlin residence, the architect nods to it with a monumental wall of ‘a‘ā—a type of craggy lava rock with a frothy surface and dense core—anchoring the entrance. Since lava is both the literal bedrock of the islands and the embodiment of the Hawaiian goddess Pele, Radziner quickly discovered that sourcing the material with sensitivity and care is “not as easy as one might think,” he says, and “quite expensive.” Commercially procuring just enough for this edifice connects the home to Hawai‘i in a way that feels priceless.

Other builder’s materials also evoke the tropics: lofty, red cedar-panel ceilings are reminiscent of Hawai‘i’s plantation homes; the lānai is lined with ipê, a Brazilian hardwood that resists the elements; and, depending on the light, the exterior stucco shifts between a sandy hue or warm tan, both apropos of the beachy setting. Inside, the walls are dimmer and duskier, akin to dark greige. “This makes the house feel like a sanctuary,” Radziner says. “If

it’s overcast or rainy, it’s cozy. If it’s bright and radiant outside, it’s still cozy.”

For the homeowner, the darker walls are nonetheless neutral—all the better to showcase his chromatic collection of fine art. Speaking by phone from his car while stuck in L.A. traffic, Karlin nimbly describes the pieces that animate the home, notably the great room. A dynamic canvas by Ethiopian American contemporary artist Julie Mehretu, layered with expressive strokes of pencil, pen, and acrylic, hangs in the lounge, while one of Cincinnati artist Jim Dine’s iconic bathrobe paintings—a triptych—looms over the dining area. At the top of the entry stairs, a grid of nine mixed-media screenprints of giant emojis—from a zesty yellow lemon to a shapely green avocado—adds unexpected levity to an otherwise polished tableau of simple, modern furnishings. Of his 2017–2018 series, the late godfather of conceptual art John Baldessari once said, “How can you not be interested in emojis? They just look so stupid!” (For the record, Karlin prefers the term “whimsical.”)

But for all the visual impact inside and out, it’s the natural elements that most shape the experience of being here. The gentle trade winds, for instance, flow through the house each day, a steady, whistling presence built into the design. All that fresh air functions as natural ventilation: deep, cleansing, well-oxygenated breaths for both house and inhabitants. Karlin, however, takes a more practical view, describing the currents—easing in from the east and then slipping out to sea—as a way to “keep ocean spray off the windows.” Still, there’s something about the direction and dependability of the breeze that just feels right. “The wind will always be at our back,” he says.

LIGHT AND

FORM

TEXT BY KATHLEEN WONG IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER

Sculptor and lighting designer Mark Chai creates sinuous, interlocking forms inspired by the natural world.

Greeting guests by the front door of Mark Chai’s single-level home in ‘Aiea is a display of six hanging lamps fashioned from white plastic and wood veneer in varying shades. Each lamp is different—elongated, circular, and hourglass forms featuring interlinked geometrical patterns or accordion-like folds that Chai cut by hand. “Everything’s kind of experimental,” he says, explaining that he’s always trying out new shapes, materials, and forms of illumination.

The sculptor, who is of Native Hawaiian and Chinese ancestry, has long been fascinated with art and craftsmanship. While he was born in Honolulu and spent most of his life there, he vividly recalls the roughly three years he lived in Japan as a child, during his father’s military service. He says he watched in awe as Japanese carpenters effortlessly assembled a fence, cutting and chiseling the wood pieces to seamlessly fit into each other, no nails required. “That stuck in my head, and at that age, I kept thinking, I can do that,” Chai says.

He studied ceramics and sculpture at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, graduating with a BFA in 1976 before going into work as a graphic designer for Duty Free Shoppers and then a local

advertising agency. It was the pre-Adobe software days, and he learned to sketch designs by hand. He manually assembled the ads with a typesetter, stripping and cutting the elements before pasting the layout together. This tactile process continues to influence him as an artist today.

When the Gulf War hit and businesses cut budgets, Chai was laid off. He took a job at The Queen’s Medical Center as a patient transporter. Serendipitously, it was there that he fell back in love with sculpture, taking home pieces of furniture the hospital was throwing away and reimagining them as works of art. One such piece lives in the back corner of his house: a rescued cabinet that he turned into an orange modular storage unit by mounting it on splayed legs, giving it a ’60s flair.

Throughout his spacious and airy home, Chai displays a selection of art and furniture that speaks to his penchant for minimalistic, fluid forms. Almost all of it, Chai made himself. He often finds inspiration wandering Reuse Hawai‘i, seeing what materials can be revitalized. Chai has established a reputation for utilizing secondhand materials, and people are constantly offering him discarded items. He’s transformed tree branches into floor

lamps, distorted plastic barrels into armchairs, and an old washing machine drum into a sculpture.

When something, whether manmade or natural, catches his eye, he tinkers with the curiosity of a child, the innovation of an artist, and the precision of a mathematician. “It’s really funny that, in school, we had to take geometry and trigonometry, and I said to the teacher one day, ‘When are we ever going to use this?’ Little did I know, I use [those] formulas to figure out all my lamps now,” he says with a laugh.

Trial and error take place in the carport that serves as his open-air studio. On a large work table, tools mingle with sheets of two-ply veneer, which he’s using to craft several lamps for a client’s kitchen. With their rhythmic pattern of overlapping wood, the designs allow light to shine through like sunlight through swirling clouds.

After the Honolulu Museum of Art displayed his work in 2016, Chai was commissioned to create a large-scale sculpture for a Georgia O’Keefe exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden. Influenced by her painting of a vivid heliconia, he began sculpting a literal interpretation of the tropical flower when he realized he could up the ante. “It’s gotta look like something I would do, right?” he says. In his signature style of playing with shapes and angles, he connected the flower’s beak-like bracts in a perfect loop so that they evoked a sunburst from the front but kept their distinct, spiky floral pattern when viewed from the side. As always, the design for the large, stainless steel outdoor installation was cut by hand, down to each bract. Staying true to his early

days as a graphic designer, Chai does everything manually, without computer-aided design programs, so as always, he cut everything by hand, down to each bract.

Chai often finds himself inspired by Hawai‘i’s natural elements—the shapes, patterns, and meanings they hold in Hawaiian culture. In the Mauka Terminal at Honolulu International Airport, two iridescent cylindrical sculptures hang from the ceiling—one inspired by a rain cloud from Native Hawaiian mo‘olelo (legend) and the other designed to evoke a flock of soaring ‘iwa birds. He was initially asked by Hawaiian Airlines to incorporate scraps of airplane parts, but when he saw the space and observed how sunlight floods through it, he immediately shifted gears. He envisioned artwork that was prismatic, reflecting the light at different angles throughout the day. He crafted the sculptures out of dichroic polycarbonate that radiates different colors, depending on where the viewer is. From one perspective, they gleam turquoise, blue, and purple. From another, they refract yellow and gold. Viewed directly head-on, they appear orange.

Most recently, Chai has been drawn to pōhaku, or stones. Several, gathered from Makapu‘u and Alan Davis Beach, are mounted in his front yard, appearing to levitate. He calls the stones guardians—sources of grounding and strength when he became caretaker for his parents, who faced dementia at the end of their lives. When his mother was bedridden, Chai passed the time at her bedside carving wooden vessels, nesting the smaller pōhaku in his collection within them.

On display as part of his exhibition Echoes From the Ahupua‘a at First Hawaiian Bank in downtown Honolulu in the first half of 2025, the cigar boxes capture this chapter of Chai’s life—his relationship with his parents and the emotional transition of losing them. The catalyst for the exhibition was a gift of kamani wood he received from the Kalihi-Pālama Hawaiian Civic Club the week after his father died. Looking at the wood, a canoe crop that Polynesian voyagers brought with them to the Hawaiian Islands and that was once used for houses, bowls, and trays, “I started thinking, what could I do [with it]?”

When he peeled back the outer bark to reveal the reddish, raw texture underneath, it immediately reminded Chai of the topography of the Hawaiian Islands. Sculpting a circular form out of the wood, he carved nesting spaces for two pōhaku, representing the unspoiled, uninhabited land that the first Polynesian settlers sighted. “I’m going to start with the ‘āina (land),” he remembers thinking. “And it occurred to me, I came to tell the story of Hawai‘i.”

BEYOND THE TROPHY HUNT

TEXT BY MARTHA CHENG IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

In Hawai‘i, non-native Axis deer are both a nuisance and sustenance. Hunting expeditions like the Pineapple Brothers on Lāna‘i help to manage their populations.

We have been hearing the deer all morning. Driving in the darkness down Lāna‘i’s main road before dawn broke, we heard the call of the bucks—like a crow’s caw, but more guttural. Then, as we edged along tall brush on foot, does gave warning barks. And now, crouched among lantana shrubs, we have been listening to the bucks’ roar and the rustling of their antlers against the dense vegetation around us. Here on Lāna‘i, where deer outnumber residents about 10 to one, our hunting guide, Alec Pascua, of the hunting outfit Pineapple Brothers, is finely attuned to their sounds. He can identify different bucks by the tenor of their voices, and he tells his client for today, David Merriman, a hunter from Missouri, that when the bucks call in threes, “that’s usually a good indicator that there’s a good buck around.”

But they have all been frustratingly out of reach. We have been waiting for more than an hour, hoping for one to move into the open. As the summer sun rises, the day grows hotter, and we are losing our window. Soon, the deer will bed down in the shade and not emerge until the evening. Pascua decides to try a new spot before it’s too late. He goes to retrieve

his truck, about a mile down the dirt path that we had walked down, and when he drives back with it, the sound of his vehicle startles the deer into movement. They emerge from the brush and dart across the open lane. Merriman shoulders his rifle, but they are moving too quickly for a clean shot. “There were probably 40 of them,” Merriman says in wonderment and frustration. “The wildest thing is that they’ve all been probably within 100 yards of where we’ve been standing all morning.”

Axis deer, native to India, were introduced to Hawai‘i from Hong Kong in 1867 as a gift to King Kamehameha V. They were initially released on Moloka‘i, and their offspring were moved to Lāna‘i and Maui for hunting opportunities. In their native habitats, the predator pressure is so high that Axis deer have evolved to reproduce more quickly than other deer species. But in Hawai‘i, free from their natural predators, their numbers have exploded. It’s estimated that Axis deer left unchecked can increase their population by 25 to 30 percent each year. Today, the approximately 30,000 deer on Lāna‘i, as well as their even larger numbers on Maui and Moloka‘i, devastate the islands’ native ecosystems and vegetation. Their impact on native species, such as ‘ōhi‘a lehua, the backbone of native forests—the deer nibble and rub against the trees’ bark, leaving the trees susceptible to disease—means their damage ripples out to Hawai‘i’s watershed. In addition, they’re such a threat to crops that Hawai‘i’s past and present governors have issued eight emergency proclamations, the most recent in 2023, to help farmers obtain loans to control deer on their land.

But on islands where nearly all food is imported, the deer are also sustenance. Particularly on Lāna‘i

and Moloka‘i, where deer hunting is woven into the islands’ self-reliant culture, many families have extra chest freezers stocked with venison. Pascua, like many born and raised on Lāna‘i, grew up hunting to put food on the table, and he has taught his own son to hunt starting at age 10.

A few commercial operations have taken hold, including Maui Nui Venison, which Jake Muise started with his wife, Ku‘ulani, in 2017 to help balance the deer populations on Maui. It offers some of the only wild and hunted game meat that can be sold in the U.S. (“Game” meat, like buffalo that’s often sold in stores, is usually farmed.) It’s a process that requires USDA inspectors to accompany hunters on overnight hunts, which is costly and logistically challenging but produces a more ethically harvested meat. As Muise discovered when he sent some of the venison to a food lab to be tested, it also results in some of the world’s most nutrient-dense and protein-rich red meat, in part due to the wild grazing habits and stress-free harvest of deer.

And importantly, the deer are also delicious. Its tender meat, with its clean and almost sweet finish, is so prized that fine dining restaurants, including The French Laundry in Napa and Alinea in Chicago, have included Maui Nui’s venison on past menus. And Hawai‘i’s venison is found in restaurants throughout the islands: in a ragu at Lāna‘i City Bar & Grill, presented as a tartare at Arden Waikīkī.

“This was not the hunting that I was expecting,” Merriman says. Given the deer’s numbers, “I thought it would be like shooting fish in a barrel. It’s a lot harder shooting than I was expecting, and

Thanks to wild grazing and a stress-free harvest, Hawai‘i venison is especially nutrient-dense and protein-rich.

definitely different terrain.” We are perched on a hill overlooking a former pig farm, glassing for deer. It’s a tricky target area, adjacent to a work site and threaded with telephone poles and lines. Pascua has spotted big bucks here earlier in the week. This is Merriman’s last chance for a deer.

He had chosen Lana‘i for his and his wife’s anniversary celebration—it being one of the few places in the world where he could go for a day hunt while she could get a Four Seasons spa treatment. If he couldn’t go home with a trophy buck, he was hoping he would at least be able to stock his freezer with the meat from a doe. But the allure of a trophy buck is too tempting to resist.

Through his binoculars, Pascua spots a buck about 200 yards away and nearly 50 pounds larger than one Merriman had missed early in the morning.

He points it out to Merriman, but they lose sight of it as it moves into the brush, and its reddish-brown spotted coat all but blends into Lāna‘i’s red dirt. They keep scanning, until suddenly, Merriman sees it, quickly raises his rifle, and pulls the trigger. But as we descend into the vegetation and search the area for the downed animal—or any blood on the ground or foliage—it proves to be a miss.

Not returning with an animal is an anomaly for Pascua. His success rate is nearly 100 percent, and he has led everyone from newbies (like myself, on a previous trip) to experienced hunters, including Joe Rogan, who shot a buck with a bow and arrow within 15 minutes of landing on the island. But Merriman, though disappointed, is a good sportsman. “My dad told me very early on,” he says, “there’s a reason this is called hunting and not killing.”

SOUND, SIGHT, AND SERVICE

TEXT IJFKE RIDGLEY PHOTOS BY IJFKE RIDGLEY AND COURTESY OF OHANA ARTS

Blind since birth, opera singer Laurie Rubin brings her elite music training to Ohana Arts, a performing arts school and festival in Honolulu.

When parents tell Laurie Rubin that their children have never felt as loved and accepted as they have at Ohana Arts, she knows her nonprofit performing arts school has fulfilled its mission. “For many [of the children], they were ridiculed for being in theater, or just didn’t find their people. But then they came to Ohana Arts,” Rubin says, adding with a laugh: “And theater people—we’re a unique bunch, you know?”

Born completely blind, Rubin started playing piano when she was three years old. Growing up in Encino, California, in the 1980s, her elementary school years were filled with classical music— both at home, where her father often listened to Beethoven, and at her school for the blind, where her music teacher had the students experience each instrument in an orchestra.

It wasn’t until a few years later, when Rubin started attending public school in fourth grade, that she felt she didn’t quite fit in. “It was never like a door opened in the same way [for me] as for any other sighted kid,” she says. “I had to push that door open, with lots of pushback and resistance.” She was denied entrance into the school’s gifted

and talented program because she was identified as “handicapped,” and administrators rescinded her acceptance into a summer opera program in San Francisco upon discovering she is blind.

But in ninth grade, she auditioned for the all-state honor choir, which gathered California’s most talented singers. It was the first time she made many friends—people who didn’t care that she couldn’t see and respected her ability to sing. This led her to join out-of-state summer programs and eventually attend Oberlin College and Conservatory in Ohio. For Rubin, music leveled the playing field.

During her second year of graduate school, studying in the Yale School of Music’s opera program, Rubin met her future wife, Jenny Taira, a composer, pianist, and clarinetist. Taira asked Rubin to sing in her recital, and the collaboration sparked an ongoing partnership, both romantically and professionally. After Yale, they moved to New York City, performing odd gigs and starting a chamber music group with fellow Yale grads.

One night after a performance, the two came home and thought, Well that was fun, but now what?

“There’s this feeling you get sometimes after performing, where you realize the impact is so short lived, and that it was maybe more self-gratifying— that there’s very little of an impression that you can leave,” Rubin says. That’s when they decided they wanted to work with children.

Taira, who grew up in Mililani, had received a full scholarship in high school to attend Interlochen, an elite summer arts camp in Michigan. The program had stoked Taira’s passion for music, much the way Rubin’s summer arts programs had developed her talent. But Taira would never have been able to attend without the scholarship, so she envisioned creating an international music center and festival in Hawai‘i to bring the same resources directly to Hawai‘i youth.

In 2011, Rubin and Taira moved to Hawai‘i to start Ohana Arts with Taira’s sister, Cari, an artistic and stage director. What began as an afternoon summer program for 23 students at the Hongwanji Mission School to rehearse for a musical theater production grew in enrollment and popularity the following summer, culminating in a musical showcase and stage production of The Wizard of Oz with a pit orchestra. In the years following, the program expanded to include intensive classes in acting, dance, music, and choir, along with a songwriting program that includes music theory and technology.

In 2014, Ohana Arts undertook its largest project to date: an original musical, Peace on Your Wings, composed and orchestrated by Taira with lyrics

Ohana Arts stages a production of Peace on Your Wings , an original musical that tells the true story of a young victim of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

I had to push that door open, with lots of pushback and resistance.

by Rubin. The piece is inspired by the true story of 12-year-old Sadako Sasaki, who folded a thousand paper cranes in hopes of surviving the leukemia she developed from the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. For Taira and Rubin, it is more than just a play: It teaches the message of peace through the universal language of music. The musical toured Hawai‘i, the continental U.S., and ultimately performed in Japan. The city of Hiroshima invited Ohana Arts to return to perform the musical for the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing in August 2025.

Ohana Arts has staged numerous other musical productions over the years, serving students ages six to 18 from more than 30 high schools around O‘ahu in an effort to give Hawai‘i youth—no matter their talent or background—the opportunity to experience high-caliber training in the performing arts. Today, the organization also co-hosts the summer program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Department of Theatre and Dance.

Early on in starting Ohana Arts, Rubin and her co-founders recognized that the Hawai‘i community was full of young talent hungry for guidance. “We found that lots of kids had questions and were overwhelmed by college applications, feeling like they didn’t know how to select the right song or

monologue, or what a dance call would look like and how to prepare for it,” Rubin says. “So we started a program that would focus on these things for high school students.” Many of the school’s participants come back year after year, gaining experience and confidence, with older students often mentoring younger ones.

To help students pursue a career in the performing arts, Ohana Arts maintains a faculty of acting coaches, choreographers, music directors, and songwriting teachers from New York and Los Angeles—including those who have been leads in major Broadway productions such as A Chorus Line and Wicked—to help students learn the business of being a performer, including preparing for auditions, pre-screens, and dance calls. Rubin knows the majority will not pursue musical theater professionally, saying that isn’t the goal of the program.

“We just hope that they become responsible humans,” she says. “We want to create an environment in which kids accept each other for who they are. Our goal is always to foster an environment of unconditional love.”

FROM LEGEND TO LEGACY

TEXT BY JEANNE COOPER IMAGES BY ALANNA O’NEIL

Once slated to become a destination golf resort, the Hawai‘i Land Trust has protected and led the restoration of one of Maui’s most significant cultural heritage and ecological sites.

According to one mo‘olelo, the traditional form of Hawaiian knowledge-sharing and storytelling, the very first act of conservation at Maui’s 277-acre Waihe‘e Coastal Dunes and Wetlands Refuge took place long before the area gained protected status in 2004.

In this legend, the refuge’s unique aeolian dunes— which once covered much of Central Maui—did not result from the actions of winds and waves on an eroded cinder cone, as modern science holds. “The goddess Haumea was the one to actually make these dunes in the mo‘olelo,” explains Scott Fisher, director of ‘āina (land) stewardship for Hawai‘i Land Trust (HILT), who has studied and worked at the refuge since late 2003.

“Haumea came over from Moloka‘i and brought this sacred tree known as Kalauokekahuli,” Fisher recounts. “She was looking where to plant this sacred tree, and after looking all over Maui, she decided that Waihe‘e was the place. But the winds were doing some damage to Kalauokekahuli, so

she decided to build these dunes to provide it some protection.” The dunes, which rise to 255 feet in places and still cover 103 acres, are called Mauna ‘Ihi, which means both “sacred mountain” and “mountain of ‘ihi,” the name for the nowendangered endemic portulaca growing along the sandy coast.

Carbon-dating reveals that newly arrived South Pacific voyagers began living in the area by the early 11th century, attracted to the abundant marine life of its fringing reef and two freshwater streams. The ancient Waihe‘e villages of Kapoho and Kapokea were built here, fed by a well-irrigated loko i‘a kalo (fishpond with taro patches), and they claim ties to two of Maui’s greatest chiefs: Pi‘ilani, the unifier of the island’s two kingdoms in the mid-1500s and who bequeathed Waihe‘e to his sons; and Kahekili, who defeated Hawai‘i Island chief Kea‘aumoku in the Battle of Kalae‘ili‘ili at Waihe‘e around 1766.

The mo‘olelo of Haumea’s divine protection at Waihe‘e foreshadows the later destructive human impacts on the area. “As the story goes, Kalauokekahuli was nefariously cut down and it was washed down into Kalepa Stream and floated over to O‘ahu,” Fisher says. “And when it floated over to O‘ahu, some fishermen saw it in the water and said, ‘Wow, that’s some very special tree,’ and they took it to land and fashioned it into a temple image.” Legend holds that a number of ki‘i, or temple images, on Maui and O‘ahu were made from Kalauokekahuli, but it’s unlikely any remain, due the mass destruction of ki‘i after King Kamehameha II ended the traditional belief system of his predecessors in 1819.

The refuge is a powerful reminder that when we take care of the land, it takes care of us.

In the modern era, human depredations to Waihe‘e have involved diverting stream water for sugar plantations in the late 19th century; draining its 27 acres of wetlands for cattle grazing and dairy operations that lasted from 1919 to 1970, which allowed its 7-acre fishpond to dry into a kiawe forest; and building a World War II bunker atop the remains of Kealaka‘ihonua heiau (temple).