Dear Valued Guests,

My name is Kenji Fukunaga, and I assumed the position of General Manager at Halekulani Okinawa in April 2025. First and foremost, I would like to extend my greetings to all of you and express my great honor in welcoming you as part of the ‘ohana (which means “family” in Hawaiian) at Halekulani Okinawa.

At the property, we deeply cherish this spirit of ‘ohana, striving to create unforgettable moments for our guests and to earn your continued support. This July, we proudly celebrated our sixth anniversary, and I would like to express my deepest gratitude for your patronage over the years.

In this issue of Living, you will find content that highlights the charms of Okinawa, including the rich history of Ryūkyū lacquerware, the depth of Okinawan food culture, contemporary crafts, and the story behind Hawai‘i’s beloved aloha wear. We hope these stories inspire you to rediscover the beauty of Okinawa and Hawai‘i.

During your stay, we invite you to take a moment to relax and enjoy Living magazine as well as the beautiful nature and culture of Okinawa. We are here to ensure your visit is nothing short of memorable, and we look forward to serving you with heartfelt sincerity.

Kenji Fukunaga General Manager Halekulani Okinawa

私は2025年4月にハレクラニ沖縄の総支配人として着任いた しました福永健司です。まずは、皆さまにご挨拶申し上げますとと もに、ハレクラニ沖縄のOHANA(ハワイ語で「家族」という意味) の一員として皆さまをお迎えできることを大変光栄に思います。

ハレクラニ沖縄のOHANAの精神を大切にしながら、皆さまに とって忘れられないひとときを提供し続けられるように努めてま いりますので、今後ともどうぞよろしくお願い申し上げます。 また、ハレクラニ沖縄は2025年7月に開業6周年を迎えます。こ れまでのご愛顧にOHANAを代表し、心より感謝申し上げます。 さて、今回のLiving誌では、琉球漆器の歴史文化、沖縄の食 文化や現代アートなど沖縄の魅力やアロハウェアのストーリー を存分に感じていただける内容となっております。沖縄とハワイ の魅力を再発見するきっかけとなることを願っております。 ご滞在中にLiving誌もお手にとっていただきながら、ゆったり としたお時間をお過ごしいただければ幸いです。沖縄の美しい自 然や文化に触れ、心身ともにリフレッシュしていただければと存 じます。皆さまのご滞在が思い出深いものとなるよう、私たちは 真心を込めてお手伝いさせていただきます。どうぞ素晴らしいひ とときをお楽しみください。

ハレクラニ沖縄 総支配人 福永 健司 皆さま、こんにちは。

ハレクラニ沖縄

GENERAL MANAGER, HALEKULANI OKINAWA

KENJI FUKUNAGA

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING

SHOKO MAESHIRO

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

JASON CUTINELLA

CORPORATE AFFAIRS

JOE V. BOCK JOE@NMGNETWORK.COM

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

LAUREN MCNALLY

MANAGING DESIGNER

TAYLOR NIIMOTO

OKINAWA.HALEKULANI.COM

+81-98-953-8600

1967-1, NAKAMA, ONNA-SON, KUNIGAMI-GUN, OKINAWA, 904-0401, JAPAN

PUBLISHED BY

VP FILM GERARD ELMORE

NMG NETWORK

41 N. HOTEL ST. HONOLULU, HI 96817

NMGNETWORK.COM

© 2025 by NMG Network, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted without the written consent of the publisher. Opinions are solely those of the contributors and are not necessarily endorsed by NMG Network.

Volume 2.1 | 2025

アート 14

伝統を重ねて 26

伝統と革新のハーモニー

文化 40

物語に満ちた歴史 52 アロハなデザイン 64

希望と試練の狭間で 食 76

大地を映す一皿 92

家族が守る島の味 新しい何かを探して 104 ヤシの木々の間から

上:是枝麻紗美さんは、沖縄のあちこちに自生する クバ(葉が扇状のヤシ)など天然素材を使った民具 を丁寧に手作りしている。

Masami Koreeda crafts items from natural materials such as kuba, a fan palm abundant in Okinawa.

表紙について

伊平屋島を拠点に活動する工芸作家、是枝麻紗美さんの作品(写真:大城亘)

ハレクラニのダイニング「ハウス ウィ ズアウト ア キー」は、ハワイを舞台 に1920年台に書かれたアール・デ アビガーズの小説にちなんで名付 けられた。

The name of Halekulani’s dining venue House Without A Key was inspired by an Earl Derr Biggers novel set in 1920s Hawai‘i.

Photographed by Wataru Oshiro, this creation is the work of Masami Koreeda, an artisan based on Iheya island.

響の行方

DIVERGENT HARMONIES

著名な師の下で学んだ2人の三線奏者が、それぞれの道を 歩み、まったく違ったかたちで三線の魅力を現代に伝える。

Guided by their esteemed mentors, two sanshin players take radically different approaches to bringing the art form to modern audiences.

アロハなデザイン

PATTERNS OF ALOHA

番 組 Living Okinawa TV is produced to complement the Halekulani Okinawa experience, with videos that focus on the art of living well. Featuring cinematic imagery and compelling storytelling, Living Okinawa TV connects guests with the arts, culture, and people of Okinawa and Hawai‘i. All programs can be viewed on the guest room TV and online at living.okinawa.halekulani.com.

客室内でご視聴いただけるリビン グ沖縄TVは、ハレクラニ沖縄なら ではの上質なひとときをお過ごしい ただくために、豊かで健康的なライ フスタイルをテーマにしたオリジナ ル番組をお届けしています。臨場感 あふれる映像と興味をかきたてるス トーリーで、沖縄とハワイの芸術や 文化、人々の暮らしぶりをご紹介し ます。すべての番組は客室TVまたは living.okinawa.halekulani.com からご視聴いただけます。

アロハウェアはファッションにとどまらない。数多な文化が 織り重なり、ハワイの島々に息づく精神と物語を多彩に紡 いできた証だ。

More than a style of clothing, aloha wear is a diverse tapestry woven from the many cultures that have shaped the spirit and story of the Hawaiian Islands.

大地を映す一皿

A TASTE OF PLACE

南城の丘陵に佇むレストランでは、沖縄の大地と森、そして 珊瑚の海で育まれた豊穣の恵みをフランスやイタリアの料 理文化と重ね合わせる。

In the hills of Nanjo, a restaurant celebrates the culinary traditions of France and Italy and the bounty of Okinawa’s farms, forests, and coral seas.

家族が守る島の味

FAMILY INGREDIENTS

本部町で、何世代にも渡って受け継いできた伝統の製法を守り ながら、ゆし豆腐や手作りの菓子を丁寧に作り続ける家族。

A family preserves Okinawa’s tofu-making traditions in Motobu village, producing yushi dofu and handcrafted confections using methods passed down through generations.

ヤシの木々の間から

AMONG THE PALMS

自然のサイクルと古来の伝統を尊重しながら、伊平屋島に自 生する植物で民具を編み上げる元ファッションスタイリスト。

Honoring the cycles of nature and the traditions of old, a former fashion stylist weaves folk tools from the native flora of Iheya island.

伝統を重ねて

A LAYERED LEGACY

TEXT BY LAUREN MCNALLY

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE

角萬漆器の器には、琉球漆器の伝統と時代を 超えた美しさ、そして現代の感性が静かに息づ いている。

At Kakuman Shikki, the tradition of Ryūkyūan lacquerware lives on in pieces that balance timeless beauty with modern-day function.

Go Kadena, the sixth-generation head of Kakuman Shikki, lifts a large, unfinished piece of lacquerware off a shelf with both hands and gives it a gentle shake. Though it’s composed of a separate lid and body, the two parts fit together so precisely that they don’t shift or make a sound. “It has very minimal warping, so it doesn’t wobble or rattle,” he says. The piece is still a work in progress, but its meticulous construction is already a testament to the craftsmanship that his family’s lacquerware business has upheld throughout its more than 120-year history.

At the far end of the workshop, a cache of wood awaits transformation into Kakuman Shikki’s esteemed lacquerware. Logs of shitamagi, a dense Okinawan hardwood used to make bowls, cups, and other small items, stand upright against the wall. Stacked to the ceiling on metal shelves above them are thick cross-sections of deigo, the prefectural tree of Okinawa. This lightweight wood, prized for its stability and resistance to warping, is ideal for crafting large pieces of lacquerware like the one in Go’s hands.

In the room next door, a young artisan is applying shitaji (base coating) to the bare wooden surface of a cup. From there, it will receive seven to nine layers of lacquer before it is decorated and polished to a lustrous sheen. “The more layers it has, the sturdier it becomes,” Go says, adding that areas most prone to wear are also reinforced with fabric and paper. With equal care devoted to form and function, these are objects meant to be used, not just admired.

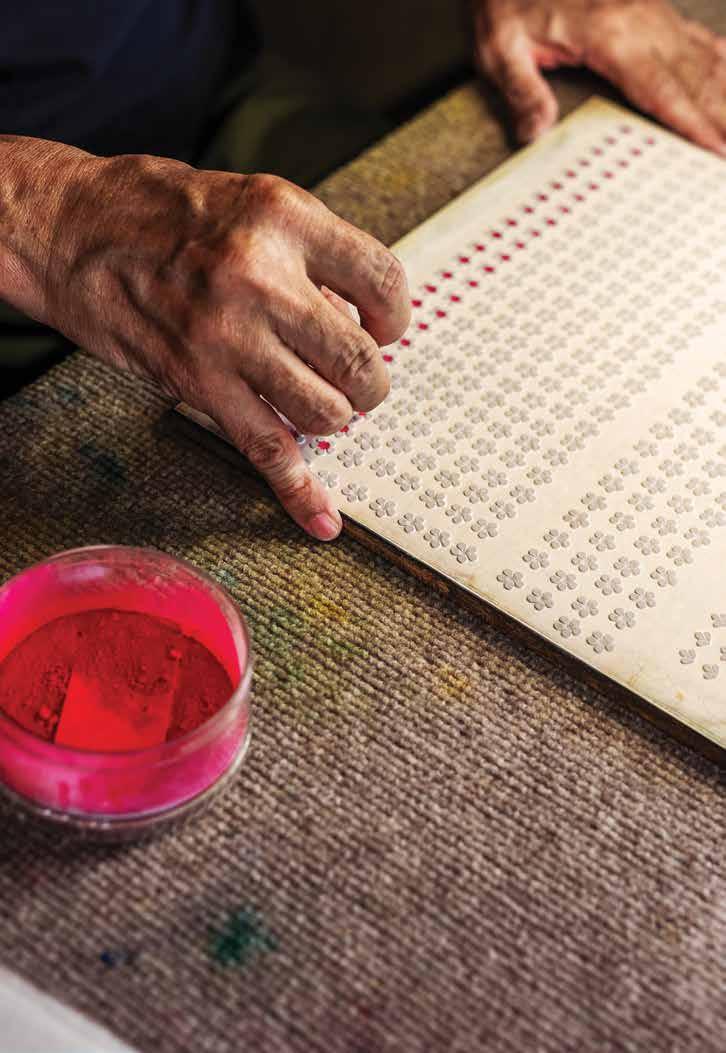

Nearby, a senior craftsman is hunched over a wooden board lined with hundreds of tiny plum blossoms delicately formed from lacquer. Using a cotton swab, he carefully dots pink pigment onto the center of each flower. Later, he’ll apply them to the vases beside him to create a raised, brocade-like effect on their surface, a distinctive feature of Ryūkyūan lacquerware.

那覇にある角萬漆器の2階の工房で、家業である漆器店の6代目当主 をつとめる嘉手納豪さんは、作りかけの大きな器を両手で持ち上げ、静 かに揺さぶった。蓋と本体は別々に作られているにもかかわらず、2つ のパーツはぴたりと噛み合い、ずれもせず、音ひとつ立てない。「歪みが 少ないので、ぐらついたりカタカタ音がしたりすることもないのです」と 嘉手納さんは話す。まだ仕上げの途中とはいえ、その緻密なつくりから は、120年余の歴史の中で同社が大切に守り続けてきた職人技が静か に伝わってくる。

工房のいちばん奥には、名高い角萬漆器社製の器となる木材が、 ひっそりと出番を待っている。壁には、碗やコップ、小物を作るために 用いるシタマキ(エゴノキ)という沖縄産の堅木の丸太が立てかけられ ていた。丸太の上の金属棚には、沖縄県の県木であるデイゴを厚めの 輪切りにした木材が天井まで積み上げられている。デイゴは安定性が あり歪みにくく軽量な木材なので、さきほど嘉手納さんが手にしていた ような大ぶりの漆器を作るのにうってつけだという。隣の部屋では、若 い職人がコップの素地に下地(下地塗り)を施している。そこから漆を 7〜9回塗り重ね、装飾と研磨の工程へ進む。「塗りの層を重ねれば重 ねるほど、しっかりとしてくるんです」と話す嘉手納さんは、摩耗しやす い部分は布や紙で補強するのだと付け加える。形と使い心地のどちら にも細やかな心を注いで仕上げられる器は、ただ美しく眺めるだけでな く、日々の暮らしの中で実際に使用してこそ、その真価を発揮する。

そのすぐそばでは、年配の職人が1枚の木板の上に身をかがめて いる。そこには、漆で繊細に形作られた何百もの小さな梅の花が並んで いる。綿棒を使い、花の中心に点々と薄い紅色の顔料を丁寧につけてい く。こうして彩られた梅の花をいくつもの花器にあしらうと、琉球漆器な らではの美しさである錦織りのような浮き彫り模様が誕生する。

嘉手納さんによると、装飾模様にはそれぞれに込められた意味が あるという。渦巻き模様は長寿と豊穣、瑞々しい果物や花は子孫の繁栄

かつて漆器の産地として

栄えた那覇の若狭で創業 した角萬漆器。

角萬漆器 Kakuman Shikki was originally established in Wakasa, a former lacquerware district in Naha.

These decorative patterns carry symbolic meaning, Go explains: Curlicues represent longevity and abundance; lush fruit and flowers signify fertility and many offspring; a traditional motif known as “sansui”—an idyllic landscape of mountains and water—reflects the craft’s influences from East Asian art and philosophy.

Though Go is now a wellspring of knowledge on Ryūkyūan lacquerware, he admits he wasn’t always interested in the family trade. It was the 2008 financial crisis that prompted him to leave his job in audio equipment manufacturing in Tokyo and return to Okinawa to learn the business. He completed a lacquerware training program at the Okinawa Craft Industry Promotion Center, located in Haebaru at the time. His wife, Yukari, pursued the same training after they were married.

“When I first encountered the world of Ryūkyūan lacquerware, I was shocked by how little it was known,” Yukari says. “I also realized that both the number of people making it and the number of people using it were declining—it felt like a craft in crisis. It made me feel all the more strongly that it has to be carried on.”

や家系の継承を表している。山河の風景を様式化した「山水」と呼ばれ る伝統模様からは、東アジアの芸術と哲学が、この工芸に深く息づいて いることが感じられる。

いまでこそ琉球漆器についての知識が豊富な嘉手納さんだが、昔 から家業に興味があったわけではない。東京の音響機器メーカーに勤 務、2008年の世界的金融危機を機に退職し、沖縄に戻って家業である 漆器づくりを学ぶことにした。沖縄県の技術支援機関である工芸振興セ ンター(当時は南風原にあった工芸技術センター)で漆工研修を終了。 妻のゆかりさんも結婚後に同センターにて漆工研修を終了した。

「琉球漆器の世界に初めて触れた時、その認知度の低さに驚き ました」とゆかりさんは振り返る。「そして、作り手も使い手も減っていて、 このままではこの伝統工芸は途絶えてしまうのではないかと危機感を おぼえたのです。だからこそ、この伝統を継承していかなければという思 いが強くなりました」

「変え方は、ちゃんとしていきたいなと思っています」

嘉手納豪、角萬漆器

“I want to make sure that any changes we make are done the right way.”

—Go Kadena, Kakuman Shikki

約500年の歴史ある琉

球漆器を継承する現代の 職人たち。

角萬漆器 Contemporary lacquerware artisans perpetuate a craft that dates back nearly 500 years.

Yukari now plays an integral role at Kakuman Shikki alongside Go, who took over from his father five years ago. Together, the couple work side by side to carry the company into its next chapter, ensuring not only the continuity of the craft but also its ongoing relevance.

In the retail space beneath the Kakuman Shikki workshop in Naha, formal wares such as oju (tiered food boxes), obon (serving trays), futatsuki owan (lidded bowls), and kashiki (confectionery vessels) are increasingly joined by more casual items like chopsticks and hand mirrors. “Traditionally, Ryūkyūan lacquerware was made primarily for gifts and ceremonial use,” Yukari says. “But going forward, we’re gradually shifting toward creating items people might buy for daily use.”

She points out a display case of lacquer jewelry. “I think there’s a sense that [this craft] no longer quite fits the needs of modern life, so we started designing accessories with the idea that it might help more people discover and connect with Ryūkyūan lacquerware,” she says.

ゆかりさんは現在、5年前に父の後を継いだ嘉手納さんと共に、 角萬漆器を支える存在として欠かせない役割を担っている。夫妻は共に 肩を並べて歩み、伝統工芸の継承だけでなく、現代における意義と価値 を保ち続けるために、この老舗の新たな一歩を踏み出している。

那覇の工房階下の店舗には、角萬漆器が手がける商品がずらり と並ぶ。お重、お盆、蓋付きお椀、菓子器といった格式ある器のほか、最 近では箸や手鏡といったカジュアルな商品も増えてきている。「もとも と琉球漆器は主に贈答品や儀式用に作られてきました」とゆかりさん は話す。「けれども、これからは徐々に、日常使いするために購入してい ただける商品も展開したいと考えています」。ゆかりさんは、漆のジュエ リーが並ぶショーケースを指差しながら「(この工芸は)もはや現代の 生活様式には不要だと思われているのではないかと感じたのです。だ から、琉球漆器をより多くの人に知ってもらい、共感してもらえることを 願って、身近に使えるアクセサリーのデザインを始めました」と語った。

同社はさらに、漆器をより手に取りやすい価格で提供できるよう に、素材選びや製造工程の見直しを進めている。「木材も漆も価格が

角萬漆器

漆で模様を浮かび上がら

せる技法は「堆錦(ついき ん)」と呼ばれている。

The technique of creating these raised lacquer motifs is known as “tsuikin.”

The company is also in the process of reevaluating its materials and production methods to keep its offerings accessible to customers. “With the cost of wood and lacquer constantly rising, it’s important to make sure everyday items don’t become too expensive,” Yukari says. “If they’re priced out of reach, it defeats the purpose.”

Still, Kakuman Shikki remains committed to tradition. “I want to make sure that any changes we make are done the right way,” Go says. “Ryūkyūan lacquerware is defined by its techniques, materials, and craftsmanship—I think the best approach is to preserve those core elements while making changes to everything else. We want to cherish those foundations as we move forward.”

上がっていく一方ですが、毎日使ってもらうものは高価になりすぎない ことが大切です」とゆかりさんは語る。「手の届かない価格になっては、 本末転倒になってしまいます」

それでも、角萬漆器は伝統を礎としたものづくりを貫いている。 「変え方は、ちゃんとしていきたいなと思っています」と嘉手納さんは話 す。「琉球漆器を琉球漆器たらしめているのは、技術と素材と技法です。 それを守りながら、それ以外を変えていくっていうのが、自分たちの変 え方なのかなと思っています。大切な土台はそのままに、これからも制 作を続けていきたいのです」

伝統と革新のハーモニー

TEXT BY NOEMI MINAMI

TRANSLATION BY CATHERINE LEALAND

IMAGES BY EGAFILM, HIROSHI NIREI, AND COURTESY OF ARAGAKI MUTSUMI

伝統と革新を融合させながら、名匠の導きのもと、 歌三線の芸術に向き合う二人のアーティスト。

Blending tradition and innovation, two artists explore the art of the uta-sanshin under the guidance of renowned masters.

KUNIKOは、沖縄音楽に おいて伝説的存在である

大城美佐子のもとでその

技を磨いた。大城美佐子 の写真(右)は、仁礼博に よるもの。

KUNIKO honed her craft under Okinawan music legend Misako Oshiro, pictured on opposite page in a photograph by Hiroshi Nirei.

KUNIKO

KUNIKO was working as a DJ in Tokyo when, in 2011, following the loss of her mother, she found herself drawn to the homeland of her father’s family in Okinawa. She recalls of that formative time: “Her passing made me question who I was and what path I should take. When I visited Okinawa, it felt as though a gentle voice called out to me, saying, ‘This is where you are meant to be.’ Within a week, with nothing but a backpack, I made it my home.”

In Okinawa, KUNIKO’s yearning to delve deeper into the island’s musical heritage grew stronger. She began with classical sanshin before turning to folk songs, studying under Misako Oshiro, a revered singer of Okinawan minyō (folk) music. In a postwar era dominated by male voices, Oshiro emerged as a rare and powerful female presence. Beyond captivating audiences with her extraordinary vocal gift, Oshiro was lauded for devoting her life to sharing the soul and history of Okinawa through song. “I was not born in the era when these folk songs first took shape, so I can only imagine their original spirit,” KUNIKO says. “That is

KUNIKO

東京でDJとして音楽キャリアをスタートしたKUNIKOは、2011年に母 を亡くしたことをきっかけに、父方のルーツである沖縄へと拠点を移す。 「母を亡くして、自分のアイデンティティや存在意義を改めて考えさせ られました。自分にできることは何なのかを見つめ直したとき、自然と足 が沖縄に向かっていたんです。そして訪れた沖縄で『ここで生きていきな さい』という声が聞こえた気がして。一週間後にはリュックひとつで移住 していました」と当時を振り返る。

移住後、「沖縄の音楽を深く学びたい」という思いが強く芽生え ていった。そして、三線の古典音楽から始め、後に「沖縄民謡の偉大な る唄い手」と称される大城美佐子のもとで民謡を学ぶようになる。男性 中心だった戦後の沖縄民謡界において、大城美佐子は数少ない女性 の民謡歌手として地位を築き、長年にわたり第一線で活躍した。その 卓越した歌唱力だけでなく、沖縄の心と歴史を歌い続けた生き様その ものが「伝説」として語り継がれている。「私は民謡が生まれた時代に 生きていないので、思いを馳せることしかできません。だからこそ、師匠

why I immerse myself fully in learning the stories of my mentors and predecessors, carrying their legacy forward through my own voice.”

Today, KUNIKO continues to study and perform traditional music while also creating contemporary music with the label Bigknot Records. Other projects in recent years include composing the evocative soundtrack for the Okinawa-based drama series Fence (2023) and collaborating with the Okinawan hip-hop artist Awich on the 2023 track “The Union.” “It is because of those who have preserved our traditions that we exist today,” she says. “That is why I want to make music that crosses borders, languages, and skin colors, allowing the spirit of Okinawa’s music to reach hearts everywhere.”

Driven by her desire to expand the reach of Okinawan music, much of KUNIKO’s work features modern arrangements that blend hip-hop and pop. “Even here in Okinawa, people don’t listen to traditional music every day,” she says. “That’s why I consciously create songs with the Bigknot team that many can enjoy. I want to make music for everyone, music that even children can dance and sing along to.”

Beneath KUNIKO’s deep respect for Okinawan classical and folk traditions is another, more profound aspiration: to perpetuate a legacy of peace. “Okinawa experienced war, but it is an island that overcame the hardest times through song and dance,” she reflects. “This history has nurtured the spirit of peace, coexistence, and mutual support—the ‘yuimāru’ culture. I hope this spirit will reach the people of the world who, today, are suffering.”

や先人たちのお話をきちんと聞いて、その思いを歌にのせて繋ぎたいと 思って学んでいます」とKUNIKOは話す。

現在は、伝統音楽を学び演奏し続けながら、レーベル「Bigknot Records」のアーティストとして活動している。他にも、沖縄を舞台にし たドラマ『FENCE』(2023)の劇伴制作や、楽曲「THE UNION」での Awichとのコラボレーションなど、現代の沖縄音楽を盛り上げる存在と して注目を集めている。彼女は、「伝統を継承してきた方々がいてこそ、 私たちがいる。だからこそその存在を大切にしながら、国や言語、肌の 色を越えて、沖縄の音楽が共振共鳴できるようなクリエイティブを生み 出したいと思っています」と語る。

そんなKUNIKOの音楽には、HIPHOPやポップスの要素を取り 入れた現代的なアレンジの楽曲も多い。そこには、沖縄音楽の入口を広 げたいという思いがある。「沖縄の人たちでも、民謡や古典音楽を日常 的に聴いているわけではありません。だからこそ、たくさんの人に沖縄音 楽を知ってもらえるような曲作りをBigknotチームで意識しています。 みんなが聴きやすくて、子どもたちも一緒に踊ったり口ずさんだりでき るような作品を届けたいと思っています」

古典や民謡に深い敬意を抱くKUNIKOにとって、伝統とは「これ を残したい、つなぎたい」という“思い”そのものだ。願うのは、その“思い” をより多くの人に届け、次の世代へとバトンをつないでいくこと。そして そういった彼女の活動の根底には、「平和」への思いがある。「沖縄は戦 争を経験しました。本当に苦しいときこそ、歌と踊りで乗り越えてきた島 です。そうした歴史のなかで、平和や共生、助け合いの精神である『ゆい まーる』の文化が育まれてきました。この精神が、今まさに戦争で苦しん でいる世界の人々に届いたらと願っています」

Aragaki Mutsumi

Born in Okinawa to Okinawan parents, Aragaki Mutsumi grew up in Nagoya surrounded by the stories of her heritage. Thanks to her grandparents in Okinawa, who were deeply involved in Okinawan music, she was exposed to the island’s emblematic three-stringed instrument, the sanshin, from an early age, but it was not until high school that it captured her heart. During a time of self-reflection and exploring her roots, she heard Okinawan folk music on the radio, a moment that sparked a deep connection. “Since middle school, I have been drawn to roots music, like African music,” she explains. “I think that's why Okinawan music resonated strongly with me.”

At university, Aragaki began learning sanshin and, after graduating, moved to Okinawa to deepen her practice. There, she received formal training under the head of the sanshin school she had attended in Kansai. Her teacher was a disciple of Chōki and Kyoko Fukuhara, two iconic figures in Okinawan music. Chōki was a celebrated composer and producer, often called the “father of Okinawan new folk songs.” Kyoko was a legendary singer from the golden age of Okinawan folk music, known for recording many songs alongside Chōki. Together, they shaped the postwar Okinawan music scene and left an enduring influence on its evolution. Aragaki recalls her teacher’s style vividly: “He was skilled in both classical and folk music, and his singing was deep and soulful, with dynamic shifts in tempo and intensity. The way the sanshin wavered so freely—it felt almost like jazz. That influence is very much alive in my music today.”

After over a decade of training in classical and folk traditions, Aragaki shifted her focus to making music, gradually cultivating the distinctive style she embodies today. In this creative journey, she found renewed inspiration in the works of Chōki and Kyoko. Aragaki was deeply moved by listening to their music on vinyl records and phonographs. “I was deeply captivated by the powerful intensity and sharp contrasts of pace, all delivered with grace and delicate nuance in their uta-sanshin performance,” she recalls. “It reminded me of the feeling I get from music I’ve always loved, such as soul, jazz, and classical music. What made it even more meaningful was knowing that these musicians were the very mentors of my teacher. In that moment,

Aragaki Mutsumi

沖縄出身の両親を持つ新垣睦美は、沖縄で生まれ、名古屋で育った。 祖父母が伝統音楽に携わっていたこともあり、三線の存在は幼い頃か ら知っていたものの、その音楽との出会いは高校生の頃。自身のルー ツやアイデンティティについて思いを巡らせていた時期に、ラジオから 流れてきたのが沖縄民謡だった。大きな衝撃を受け、沖縄の伝統音楽 に興味を持つようになる。「もともと中学の頃から、アフリカ音楽など、 ルーツミュージックが好きでした。沖縄の音楽もそういう要素に強く惹 かれたのだと思います」と彼女は振り返る。

その後、関西の大学に進学。ある日、大阪で開かれていたエイ サーの大会で三線を演奏していた人に声をかけ、教室を紹介してもら う。それをきっかけに2年ほど三線を学び、大学卒業後には沖縄へ移 住。関西で通っていた教室の家元のもとで本格的に学び始めた。その 家元の師匠は、沖縄音楽界を代表する普久原朝喜·普久原京子の弟子 にあたる人物だった。朝喜は、「沖縄新民謡の父」と称される作曲家·プ ロデューサーであり、京子はそんな朝喜とともに多くの楽曲を録音した 沖縄民謡の黄金期を代表する歌手。二人は戦後の沖縄音楽を牽引し、 その後の発展に決定的な影響を与えた存在だ。そんな流れをくむ師の 演奏について、新垣はこう語る。「先生は古典も民謡も両方されていた のですが、歌が底深く、緩急がありソウルフルで三線も自由自在な揺ら ぎ方がジャズみたいでした。そういった影響は今の私の音楽に、少なか らずあると思います」

古典や民謡を10年以上学んだのち、今のスタイルへとつながる 音楽作りを始めた新垣。自身が表現したいことを模索していたところ、 普久原朝喜と普久原京子の音楽に出合い直したのがきっかけだった。 蓄音機盤やレコード盤のアーカイブを聴き漁り、改めて大きな感銘を受 けたと彼女は振り返る。「力強い迫力と緩急のキレがあり、かつ、優美で 繊細な歌三線に、心底魅せられました。それが自分のなかでもともと大 好きなソウル音楽やジャズ、クラシックなどを聴いて感動する感覚と似 ているなと気づいたんです。しかも、その音楽をつくったのは、私の師匠 が直接学んだ方たちだったんです。だからこそ、今まで教わってきたテク ニックと感動が、自分のなかでひとつにつながった感覚がありました」

新垣睦美の近年の作品は沖 縄伝統の空手や古武道、印象 派の絵画、古謡や祈りの唄な どから着想を得ている。 all the techniques I had learned and the emotions I had experienced came together naturally.”

In recent years, Okinawan pop musicians have embraced this heritage with songs that incorporate sanshin and folk music. Yet Aragaki forges a unique path in this ever-evolving soundscape, remaining rooted in tradition while weaving in contemporary influences, including elements of jazz and electronic music. At the core of her artistry lies a heartfelt desire to celebrate the spirit of Okinawan music. “Tradition can sometimes feel rigid, but for me, I’ve always loved the unique sound and playing techniques of the sanshin, as well as the vocal tones and singing styles of Okinawan music, which is truly one of a kind—and before I knew it, I had been doing it for decades,” she shares. “I used to wrestle with what it meant to be Okinawan. Now I see that my roots, intertwined with my life in Nagoya and beyond, have shaped my voice as a person and a musician.

近年の沖縄音楽には、三線や民謡を用いたポップスなど、築かれ てきた独自のスタイルがある。新垣は、そういった音楽の方程式から一 歩離れ、コアな伝統音楽と向き合いつつ、ジャズや電子音楽を取り入れ るようになっていった。その根底には常に「自分の愛する沖縄音楽の良 さをどうしたら伝えられるだろうか」という思いがある。「『伝統』って言 葉は堅いイメージがあるけど、私は本当に唯一無二である沖縄音楽の、 三線の音色や奏法と、声色や唱法が大好きで、気がついたらずっと続け ていたという感じです。私は沖縄で育っていないからこそ、「沖縄らしさ とは何か?」にとらわれて葛藤した時期もありました。でも今は沖縄に ルーツを持ち、名古屋で育ったことなど、いろいろな要素がミックスされ ていることが自分らしさだと思っているし、それが音楽にも投影されて いるように感じます」

Aragaki Mutsumi’s recent work draws inspiration from traditional Okinawan karate, kobudō (martial arts), Impressionist paintings, and ancient songs and prayer chants.

「『沖縄らしさとは何か?』にとらわれて 葛藤した時期もありました」 新垣睦美、ミュージシャン

“I used to wrestle with what it meant to be Okinawan.”

—Aragaki Mutsumi, musician

BY

IMAGE

JOHN HOOK

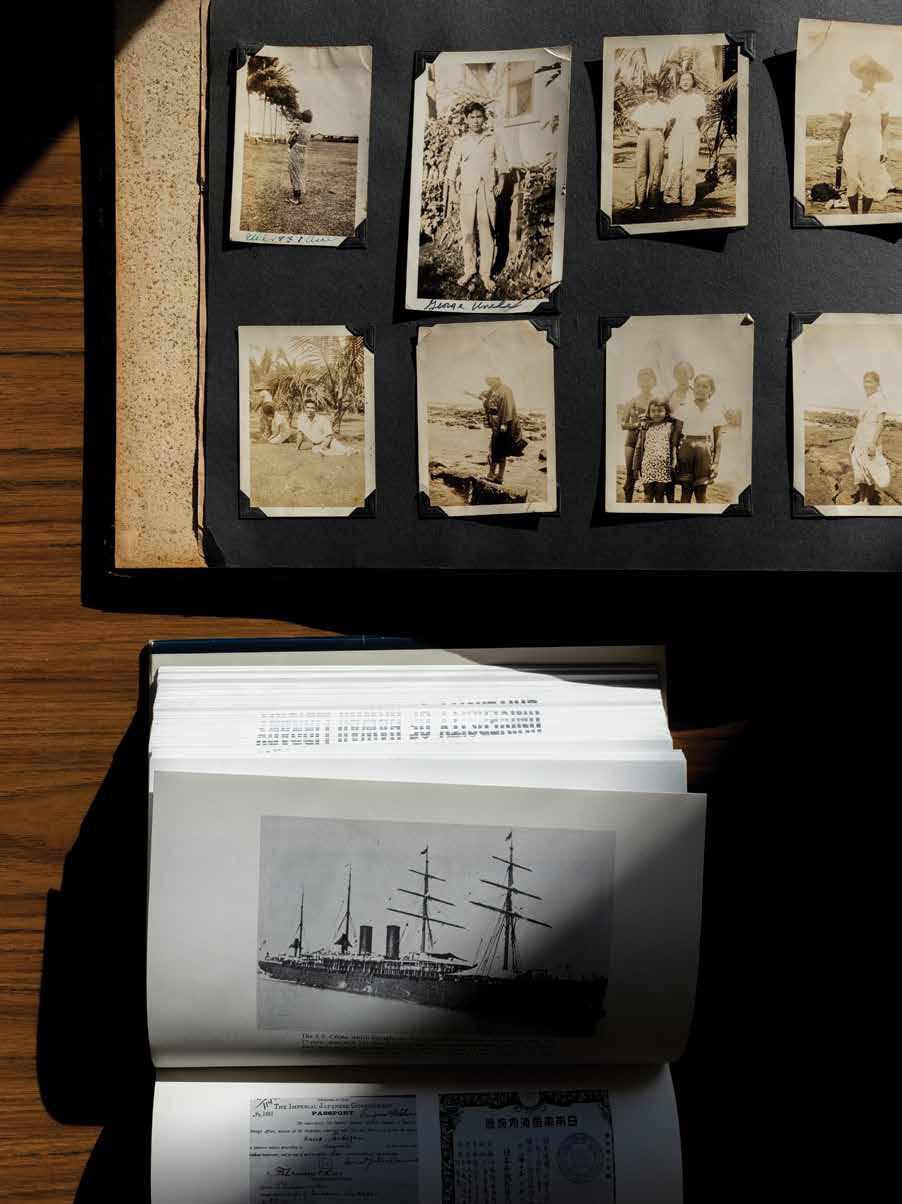

STORIED PAST

TEXT BY EMILY CHANG

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO SHIMA

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK, LILA LEE, MICHELLE MISHINA, AND LAURA LA MONACA

アール・デア・ビガーズの殺人ミステリー小説にちな んで名付けられた「ハウス ウィズアウト

ノスタルジーに浸る。

At House Without A Key, inspired by Earl Derr Biggers’ murder mystery novel of the same name, a writer basks in nostalgia for what once was.

ア キー」の

“That’s how the murder happens,” says Hi‘inani Blakesley, cultural advisor at Halekulani, as we stand in front of the hotel, facing Kawehewehe channel. It is the same channel that Kamehameha I sailed through in 1795 to land his troops on O‘ahu in his mission to unite the islands, Blakesley tells me. It is a clear, wide channel of sand through Waikīkī’s reef, stretching all the way to the breakpoint, where today we can see surfers waiting for waves at Pops. This is the channel that (spoiler alert) enables the murder in Earl Derr Biggers’ The House Without a Key

In 1919, Biggers stayed at the hotel Gray’s-By-TheSea, which stood near where we are now, and where the idea of the novel came to him. Many people know that Halekulani’s bar and restaurant House Without A Key was named after the novel, but few realize the story’s title itself was inspired by the hotel he stayed in, previously J.A. Gilman’s home, an actual house without a key—and so the name comes full circle.

Despite loving Raymond Chandler’s detective novels of the same era, I had never read The House Without a Key until now. Part of it might have been the idea of a Chinese detective written by a white person in the ’20s—I pictured something like the ridiculous bucktoothed Mickey Rooney playing Mr. Yunioshi in the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s . But when I picked it up recently, I was captivated. Sure, there are cringe-inducing moments, particularly in detective Charlie Chan’s stilted speech, but Chan is also often depicted as the most observant and smartest person in the room—particularly astonishing in the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act. It turns out, Biggers was inspired by a real-life Chinese police detective in Honolulu at the time, Chang Apana, who stood at 5 foot 3 and carried only a bullwhip. The stories about him are legendary: the time he rounded up 40 gamblers single-handedly, the time he was thrown from a second-story window and landed on his feet, the time he had been run over by a horse and buggy. Charlie Chan launched Biggers’ fame, spawning six books and more than four dozen movies centered on the detective, but it’s the quieter moments of the book that really draw me in, the snapshot of Hawai‘i in the 1920s. Among many depictions of the era, Biggers describes a trolley that “swept over the low swampy land between Waikiki and Honolulu, past rice fields where bent figures toiled patiently in water to their knees, past taro patches, and finally turned on to King Street … [past] a Japanese theater flaunting weird

ハレクラニの文化アドバイザーを務めるヒイナニ・ブレイクスリーさんは ホテルの前に立ち、カヴェヘヴェヘ水路のほうを向いて「そうやって殺 人は起こるんですよ」と話す。1795年、ハワイ諸島の統一を目指したカ メハメハ大王が軍隊をオアフに上陸させるために使った水路だと彼女 は教えてくれた。ワイキキのリーフの間を通る幅広の砂の水路は、波待 ちをするサーファーたちの姿が見える「ポップス」と呼ばれるサーフブレ イクまでまっすぐに伸びている。これがアール・デア・ビガーズ著の小説 『ハウス ウィズアウト ア キー(鍵のない家)』で殺人を可能にした水路 である。(ネタバレ注意) 1919年、ビガーズは今私たちがいる場所の近くにあったホテル、グ レイズ・バイ・ザ・シーに滞在して小説の構想を練った。ハレクラニの バー&レストランのハウス ウィズアウト ア キーがこの小説にちなんで 名づけられたことはよく知られているが、小説のタイトルそのものが、 以前はJ・A・ギルマンの家だった彼の滞在したホテルが「鍵のない家」 だったことに由来していることを知る人は少ないだろう。

私は、同時代のレイモンド・チャンドラーの探偵小説は好きだったが、 『ハウス ウィズアウト ア キー』は読んだことがなかった。1920年代 に白人が書いた中国人探偵という設定から、映画『ティファニーで朝食 を』でミッキー・ルーニーが演じた出っ歯のミスター・ユニオシのような キャラクターを想像していたからかもしれない。ところがこの本を初め て手に取った私は、すっかり夢中になってしまった。探偵チャーリー・ チャンのたどたどしい話し方には多少の不快感を覚えるが、そのキャラ クターは多くの場面で最も観察力に溢れる賢い人物として描かれてい る。中国人排斥法の時代にあって、それは驚くべきことだ。ビガーズは、 当時ホノルルに実在した中国系アメリカ人の刑事、チャン・アパナをモ デルにしていた。身長160センチで牛刀のみを持ち歩いていた彼には、 たった一人で40人の賭博師を捕えたり、2階の窓から投げ出されて両 足で着地したり、馬と馬車に轢かれたりといった伝説的なエピソード が尽きない。

チャーリー・チャンによってビガーズは名声を高め、この探偵を題材 にした6冊の本と48本以上の映画が生まれた。だがこの本を読んで私 が一番の魅力と感じるのは、1920年代のハワイを描いた静かな情景 である。ビガーズによる当時の風景の描写の中に、路面電車についての 以下のようなものがある。「ワイキキとホノルルの間の低い湿地の中を 走り、膝まで水に浸かって辛抱強く屈んで働く人たちのいる水田やタロ イモ畑を過ぎ、やがてキングストリートに入った。フォードのサービスス テーションの近くにある怪しいポスターを掲げる日本の劇場を過ぎる と、王国の宮殿とわかる建物の前を通る」。この本を読むと、およそ100 年前にビガーズがホノルルで目にしたものを想像できると同時に、何

ハウス ウィズアウト ア キーは、今なお地元エンターテイン メントの拠点として賑わいを見せている。上:ザ·ワイティキ 7のバイオリン奏者、ヘレン·リウ博士(撮影:ローラ·ラ·モナ カ)右:フラダンサーのブルック·マヘアラニ·リー(撮影:ミ シェル·ミシナ)

House Without A Key remains a vibrant venue for local entertainment. Above, image by Laura La Monaca of violinist Dr. Helen Liu of The Waitiki 7. At right, image by Michelle Mishina of hula dancer Brook Māhealani Lee.

ハウス ウィズアウト ア キー

チャーリー·チャンによって

ビガーズは名声を高めて、

この架空の探偵を題材に した6冊の本と48本以上 の映画が生まれた。

The character Charlie Chan launched Biggers’ fame, spawning six books and more than four dozen movies centered on the fictional detective.

posters not far from a Ford service station, then a building he recognized as the palace of the monarchy.”

To read the book is to see what Biggers saw almost a century ago in Honolulu, to realize what is gone, and recognize what remains. There’s the kiawe tree under which a character smokes every night, the tree which fell in 2016, but still stands—and grows—in front of the bar and restaurant House Without A Key with the same resiliency that has enabled it to live since 1887. There is also, by the small, sandy beach fronting the hotel, Halekulani’s oldest hau tree, which even a hundred years ago was “seemingly as old as time itself,” wrote Biggers in The House Without a Key

But what is really as old as time itself: nostalgia. Even in the 1920s in Hawai‘i, Biggers’ characters long for what once was. “‘The ‘eighties,’ [Winterslip] sighed. “Hawaii was Hawaii then. Unspoiled a land of opera bouffe, with old Kalakaua sitting on his golden throne.’ … ‘It’s been ruined,’ he complained sadly. ‘Too much aping of the mainland. Too much of your damned mechanical civilization—automobiles, phonographs,

がなくなり、何が今も残っているかを知ることができる。そこには毎晩、 登場人物が下でタバコを吸うキアヴェの木も登場する。1887年からハ ウス ウィズアウト ア キーのバーとレストランの前に立っているこの木 は、2016年に倒れてからも変わらぬ強い生命力を見せ、今も成長し続 けている。ホテル前の小さな砂浜にあるハレクラニ最古のハウの木につ いてもビガーズは、100年前の当時すでに「時間そのものと同じくらい 古いようだ」と『ハウス ウィズアウト ア キー』の中で書いている。 時間そのものと同じくらい古いものとは一体何か。それはノスタル ジーである。1920年代のハワイを舞台にしたビガーズの描いた登場 人物も、その昔を懐かしんでいる。「80年代、あの頃のハワイはハワイ だった。老いたカラカウア王が黄金の玉座に座していた手つかずの喜 劇オペラのような国。それが台無しになってしまった」とウィンタース リップは悲嘆のため息をつく。「本土の真似をしすぎた。自動車や蓄音 機やラジオのような忌まわしい文明の利器が多すぎなんだ。それなの に、ミネルバ。この地下深くにはまだ水が流れているんだ」 ビガーズがハワイを訪れてから間もなく、ハレクラニは現在のハウス

文 化

文 化

ビガーズのハワイ滞在後

間もなく、ハレクラニは現

在のハウス ウィズアウト

ア キーがある場所に建っ ていたアーサー・ブラウン

保安官の家を買い取った。

Not long after Biggers’ visit to Hawai‘i, Halekulani acquired Sheriff Arthur Brown’s home, the present-day site of House Without A Key.

radios—bah! And yet—and yet, Minerva—away down underneath there are deep dark waters flowing still.’”

Not long after Biggers’ visit to Hawai‘i, Halekulani acquired Sheriff Arthur Brown’s home, the present-day site of House Without A Key. The hotel Biggers stayed at, Grays-By-The-Sea closed, and Halekulani bought that too. Waikīkī was already rapidly changing in the ’20s, and as I idle at House Without A Key at sunset—the time that Biggers’ likely loved best in Waikīkī, based on his descriptions—I see more people, more buildings, more “mechanical civilization” than Biggers did during his stay. And yet, just as the deep, dark waters still flow in the springs under Halekulani, it is hard not to be swept into the age-old spell of Waikīkī while facing the ocean and listening to the De Lima ‘Ohana sing Queen Lili‘uokalani’s “Aloha ‘Oe,” “the most melancholy song of good-by,” Biggers declares in The House Without a Key . To know that someday, despite grumbling about how much life has changed, we will remember these days by the kiawe tree, right now, with fondness.

ウィズアウト ア キーの場所にあったアーサー・ブラウン保安官の家を 買収し、ビガーズが滞在したホテルのグレイズ・バイ・ザ・シーも、閉鎖 後に買収した。1920年代のワイキキは急速に変化していた。滞在中の ビガーズが最も愛したであろう夕暮れ時、私がハウス ウィズアウト ア キーでぼんやりしていると、当時に比べてはるかに多くの人や建物、そし て機械文明が目に飛び込んでくる。それでも海の方を向いて、デ・リマ・ オハナが歌うリリウオカラニ女王の「アロハ・オエ」を聞いていると、ハレ クラニの地下深くの泉から今も水が流れ出てくるように、いにしえのワ イキキの魔力にのまれずにはいられない。それは、ビガーズが『ハウス ウィズアウト ア キー』の中で、これほど哀しい別れの歌はないと言って いた曲だ。いつの日か、世の中がどれほど変わってしまったことかと憂い ながら、私たちは今のように、キアヴェの木のそばで過ごした日々を懐 かしく思い出すことだろう。

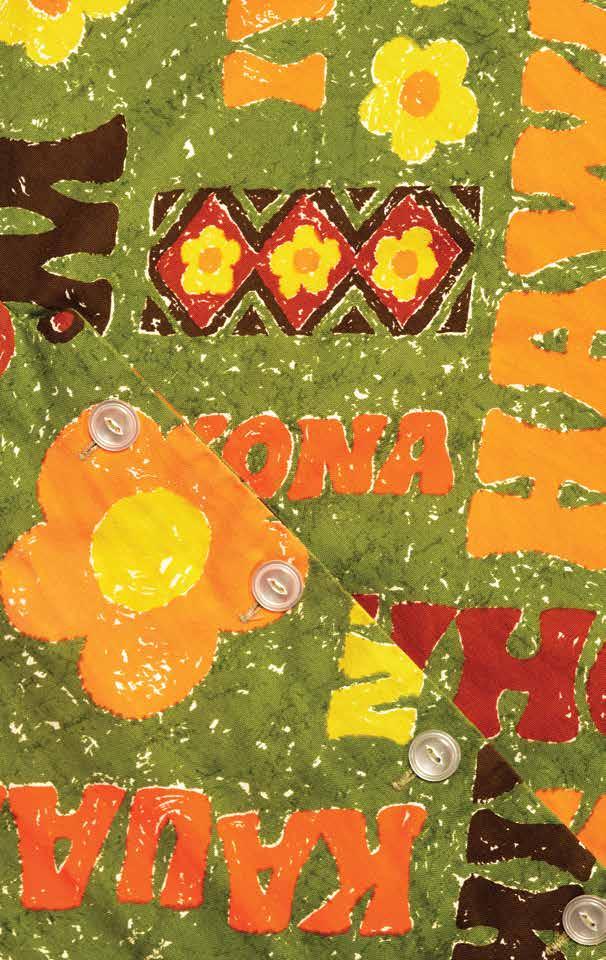

PATTERNS OF ALOHA

TEXT BY TRACY CHAN

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO SHIMA

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK, CHRIS ROHRER, AND MEAGAN SUZUKI

アロハウェア:芸術と文化と伝統が織り成す ファッショナブルな生地と世界貿易の黎明期 アロハなデザイン

A fashionable tapestry that blends art, culture, and tradition, aloha wear represents the islands’ early days of global trade.

With its vibrant motifs and rich cultural history, aloha wear is more than just clothing—it’s a storytelling medium, one that weaves together the diverse influences of Hawai‘i’s multicultural society. Native Hawaiian, Tahitian, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and other cultures all played a role in shaping the styles and designs of aloha wear recognized today.

This unique regional style can be said, however, to have begun with kapa, the barkcloth that Hawaiians utilized as their primary covering fabric. In pre-contact society, Hawaiians created kapa by soaking and pounding wauke (paper mulberry) with an i‘e kuku (wooden kapa beater), which they then dyed and scented with berries, flowers, or leaves before

鮮やかなデザインに文化的魅力と歴史が詰まったアロハウェアは、単 なる衣服ではなく、多文化社会のさまざまな影響を織り交ぜたハワイ の物語を伝える媒体である。ハワイ先住民、タヒチ、日本、中国、フィリピ ンなど、多様な文化が今日のアロハウェアのスタイルやデザインの形成 に寄与している。

実は、このハワイ独特のユニークなファッションは、かつてハワイ 先住民が主に身にまとっていた樹皮布のカパから始まったといえる。西 洋文化の影響を受ける前、ハワイ先住民はワウケ(コウゾ)を水に浸し、 イエ・ククと呼ばれる木製の棒で叩いてカパを作っていた。この平らに 伸ばした繊維に木の実や花、葉の染料で色や香りをつけ、複雑な模様

初期のホロク(ハワイアンドレス)は、ヨーロッパ風のエンパイアドレスを アレンジしたものだった。

The first holoku, or Hawaiian dress, was a modified European-style empire gown.

applying intricate patterns to the flattened fibers. But as Hawai‘i became a popular stop for seafarers and traders, the population was introduced to international clothing styles. Fashions from both the East and the West—Indian cotton under-slips, Chinese silk shawls, Western pantaloons and waistcoats—were soon incorporated into the wardrobes of the ali‘i.

When the first American missionary wives made landfall in the early 1820s, the female ali‘i (chiefs) noticed their beguiling fashions. Intrigued, Queen Kalākua Kaheiheimālie requested a dress of her own inspired by the variety of cuts and cloth she observed on the newcomers. Given the queen’s large stature, her dress makers soon realized the need to create a custom garment that was fashionable yet befitting for her form and frame. Within two days, they presented her with the very first holokū, or Hawaiian dress—a modified, European-style empire gown in white cambric.

What the ali‘i did, their people soon followed. By 1860, kapa production had dwindled, and Hawaiian men and women of all social classes wore Western garments in public. The elite classes imported their clothing from Europe, and as women’s styles in France, England, and Italy changed, so did the ones in the islands, influencing the neckline, accents, train, and cut of the original Hawaiian holokū dress. Over time, the fitted-front holomu‘u, an elegant day dress with no train, and the shorter, more relaxed and popular mu‘umu‘u emerged.

By the turn of the 20th century, the islands’ growing reputation as a safe yet exotic destination beckoned well-to-do travelers. Enchanted by Waikīkī’s golden shores and turquoise waters, tourist numbers steadily rose, and visitors remained for extended stays. “The idea of holiday and leisure becomes Hawai‘i’s marketing device,” says Tory Laitila, curator of textiles and historic arts of Hawai‘i at the Honolulu Museum of Art. “So, people start coming here to live and want to dress as if they were on vacation.”

Such vacation attire often included floral motifs, a popular design that soon became synonymous with hospitality in the islands’ growing tourism market. Although the first person to coin the term “aloha shirt” is still up for debate, a Japanese-owned shop in Honolulu called Musa-Shiya Shoten was the first recorded clothier to use the term in print: In 1935, it placed a newspaper advertisement selling finely crafted “aloha shirts” for just 95 cents, heralding the onset of a genre that would soon gain a beloved following across the globe.

を作り出していたのだ。ところが、ハワイが海運業者や貿易業者の間で 人気の寄港地になると、人々は国際的なファッションに触れる機会が 増えた。やがてインドの綿の下着、中国の絹のショール、西洋のパンタ ロンやベストといった東洋と西洋のファッションが、ハワイのアリイ(王 族)のワードローブに取り入れられるようになった。

1820年代初頭、最初のアメリカ人宣教師の妻たちがハワイに 上陸すると、女性アリイ(首長)はその魅惑的なファッションに目を留め た。興味をそそられたカラカウア・カヘイヘイマリエ女王は、宣教師の妻 たちが着ていたさまざまなカットや生地のドレスを所望した。女王は大 柄であったため、ドレス職人たちは、ファッショナブルでありながら女王 の体型に合うカスタムドレスを仕立てる必要があることに気づく。2日 後、彼らは女王に「ホロク」と呼ばれる、最初のハワイアンドレスを差し 出した。このドレスは、白いキャンブリック生地を使ったヨーロッパ風の エンパイアドレスであった。

アリイたちの間で広まったこの流行は、すぐに民衆にも受け入れ られた。1860年までに、カパの生産は減少し、ハワイのあらゆる社会階 級の男女が公共の場で西洋の衣服を着用するようになったのだ。 エリート階級はヨーロッパから衣服を輸入し、フランス、イギリス、イタ リアの女性たちの流行が変化するにつれ、ハワイの女性ファッションも 進化していった。この影響はハワイアンドレスの原型であるホロクのデ コルテや装飾、トレーン、カットにも及んだ。やがて、トレーンのないエレ ガントでタイトな日中用ドレス「ホロムー」や、丈が短くカジュアルで人 気の高い「ムームー」が登場した。

20世紀に入ると、ハワイは安全かつエキゾチックな旅行先として 評判が高まり、富裕層の旅行者が訪れるようになった。ワイキキの黄金 色の砂浜とターコイズブルーの海に魅了され、観光客は着実に増え、長 期滞在するようになった。「休暇やレジャーという言葉がハワイの売り 文句になりました」と語るのは、ホノルル美術館でテキスタイルとハワイ の歴史的文化財の展示を手がける学芸員のトリー・ライティラさん。 「これにより人々はハワイに移住し、バカンスに出かけているような服 装を求めるようになったのです」

そのようなバカンスの服装には花のモチーフがよく使われるよう になり、この人気のデザインは、成長するハワイの観光業におけるホス ピタリティの代名詞となった。アロハシャツというネーミングを誰が思 いついたのかについては諸説あるが、この言葉を印刷物に最初に使用 したとされるのは、ホノルルにあった日本人移民の仕立て屋「ムサシヤ 商店」である。1935年の同店の新聞広告によると、丹精込めて作られ た「アロハシャツ」がわずか95セントで販売されていた。それは、やがて 世界中で愛されるファッションの到来を告げるものであった。

アロハウェアはファッション

だけではなく、ハワイの人々

や場所を映し出すものだ。

More than just a style, aloha wear is a reflection of the people and places that make up Hawai‘i.

Hand-blocked prints on silk with island designs like ‘ulu (breadfruit) and hula girls were popular in stores in the 1930s. By the late 1940s, the production of aloha shirts transitioned from custom, hand-tailored items to mass-produced garments. Hawai‘i textile designer Alfred Shaheen emerged as a key player in the local clothing industry. Shaheen hired a team of local artists to design tropical shirts and dresses inspired by Hawaiian, Japanese, and Chinese culture, many of which can still be found on the collector’s market.

Since its initial popularity through the midcentury, aloha wear has been about making a statement, particularly in so far as upending the formality of the workplace and defying traditional notions of sophisticated clothing. In 1962, the Hawaiian Fashion Guild launched “Operation Liberation,” a campaign that sent two aloha shirts to each member of the Hawai‘i House of Representatives and the State Senate for the “sake of comfort and in support of the 50th state’s garment industry.” The creative campaign encouraged government

ウル(パンノキの実)やフラガールといったハワイらしいモチーフ をシルク素材に手作業で版画したシャツは、1930年代に店頭で人気 を博した。1940年代後半になると、アロハシャツの生産は手仕事のカ スタムメイドから大量生産へと移行する。ハワイのテキスタイルデザイ ナー、アルフレッド・シャヒーンさんは、地元の衣料品業界のキーパーソ ンとして頭角を現した。シャヒーンさんは地元アーティストのチームを雇 い、ハワイや日本そして中国の文化をモチーフにしたトロピカルなシャ ツやドレスをデザインさせた。これらのデザインの多くは、今でもコレク ターズアイテムとして残っている。

20世紀半ばにかけて人気を博したアロハウェアは、とくに職場 の堅苦しさを取り払い、洗練された衣服に対する従来の概念を覆す ファッションという地位を築く。1962年、ハワイアン・ファッション・ギル ドは「Operation Liberation(解放大作戦)」と題したキャンペーンを 展開し、ハワイの下院と上院の各議員に2枚のアロハシャツを送り、そ の快適さを知ってもらうと同時に、第50州目であるハワイの縫製産業 を支援するように訴えた。この大胆なキャンペーンは、地元の製造業を

文 化

文 化

1860年頃には、カパ(ハワ イの樹皮布)を使った衣服 はほとんど見られなくなり、

多くのハワイの人々は西洋 風の衣服を身に着けるよう になっていた。

By 1860, use of kapa (Hawaiian barkcloth) garments had dwindled as more Hawaiians wore Western-style clothing.

workers to wear aloha shirts on Friday in an effort to boost local manufacturing. It was widely embraced, leading the state to formally recognize the beloved weekly tradition as Aloha Friday in 1966. This, in turn, sparked a similar trend, popularly known as Casual Friday, embraced by workplaces across the nation. Today, contemporary designers continue to honor the genre. “Aloha wear is one of those things that can be considered ‘fossilized fashion,’” Laitila explains, explaining that while fabrics and detailing have evolved over time, the modern holokū, for example, still adheres to the standard, iconized garment of the 19th century. “Some designers are still making the traditional holokū dress, but for others, it’s a lot of separates: three-quarter sleeve, asymmetrical necklines, off-the-shoulder, tank tops to pair with pants,” Laitila says. “It’s aloha wear, so it really is how you wear it.”

活性化させるため、毎週金曜日に政府職員にアロハシャツの着用を奨 励するものであった。この試みは広く受け入れられ、1966年には州が この愛すべき毎週恒例の習慣を「アロハフライデー」として正式に認定。 これがきっかけとなり、同様の風潮が「カジュアルフライデー」として全 米の職場に広まることとなる。

現代のデザイナーたちは、今なおこのファッションに対して敬意 を払い続けている。「アロハウェアは、『変化していないファッション 』と いえるもののひとつです」というライティラさんは、生地やディテールは 時代とともに進化しているが、たとえば現代のホロクにおいては、19世 紀の象徴的スタンダードなスタイルがいまだに守られているのだと教 えてくれた。「伝統的なホロクドレスを作り続けているデザイナーもい ますが、近年では、七分袖やアシンメトリーなネックライン、オフショル ダー、パンツに合わせるタンクトップといったセパレートデザインも増え ています」とライティラさんは言う。「アロハウェアは、どう着こなすかに かかっているのです」

希望と試練の狭間で

HOPE AND HARDSHIP

TEXT BY JACK KIYONAGA

TRANSLATION BY KYOKO HAMAMOTO

IMAGES BY KINGO ARAKAKI, LAURA LA MONACA, IJFKE RIDGLEY, AND COURTESY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA LIBRARY

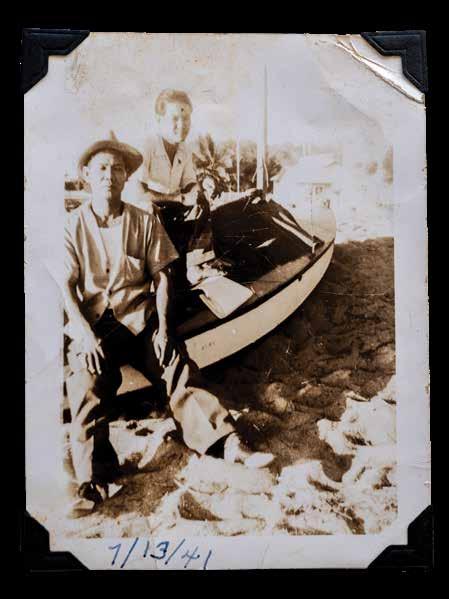

「沖縄移民の父」と称えられた當山久三の 交錯する遺産

A writer delves into the complicated legacy of Kyuzo Toyama, a statesman hailed as the “father of Okinawan emigration.”

We all have a story about where we came from, one that is the byproduct of a swirling combination of geopolitical, economic, and other forces that have collectively shaped us and wherever we call home. The more than 50,000 people of Okinawan descent living in the state of Hawai‘i today can trace this trail through the narrow gate of one man: Kyuzo Toyama, a young Okinawan who lived and worked over 120 years ago.

Born in 1868 in the town of Kin on Okinawa’s eastern coast, Toyama arrived in a world on the precipice of change. Until 1879, the Ryūkyū Kingdom ruled the chain of sandy, volcanic islands located between southern Japan and Taiwan. Following the Meiji Restoration in mainland Japan, the Japanese government sought to quickly modernize and expand—annexing Okinawa as a prefecture shortly thereafter. A young Toyama, 11 years old at the time, would go on to witness his island home change dramatically.

“Understanding Toyama’s place in history is also understanding the history of discrimination and colonization from Japan,” explains Norman Kaneshiro, co-director of Ukwanshin Kabudan, an O‘ahu-based group dedicated to Okinawan classical arts. This colonial relationship could be felt throughout Okinawan society: in the instalment of government officials from other Japanese prefectures in high-ranking Okinawan positions, in the banning of the Okinawan language in schools, in the sentiment toward Okinawan traditions like raising pigs and practicing hajichi, the tattooing of a woman’s hands, which were looked down upon by mainland Japanese.

It was while studying in Tokyo for two years that Toyama formulated a theory of economic improvement for his home island. Influenced by his friendship with Okinawan civic leader Noboru Johana, along with his own independent studies,

私たちには誰しも、自分がどこから来たのかというストーリーがある。

それは地政学的要因や経済的要因、そしてその他さまざまな力が複雑 に絡み合いながら、私たち自身と私たちが故郷と呼ぶ場所を形作って きたものだ。今日、ハワイで暮らす沖縄系住民は5万人を超える。その 移民の歴史をたどると、ひとりの人物へと行き着く。それが、120年以 上前に沖縄からハワイへ渡り、新たな未来を切り開いた青年、當山久 三である。

歴史の転換期にあった1868年、當山は沖縄本島東海岸の金武 (きん)の町に生まれた。琉球王国は南日本と台湾の間に連なる島々 を独立した王国として1879年まで統治していた。しかし本土での明治 維新後、日本政府は急速な近代化と領土拡張を目指し、沖縄を県とし て併合する。当時、わずか11歳だった當山は、故郷が劇的に変貌する 様を目の当たりにしていた。

「歴史における當山の立場を理解することは、日本による沖縄へ の差別と植民地支配の歴史を理解することでもあります」と語るのは、 オアフ島を拠点に沖縄古典芸能の継承に取り組む団体「御冠船歌舞 団(ウクゥワンシンカブダン)」の共同代表を務めるノーマン・カネシロ さんだ。その植民地的な支配の痕跡は、沖縄社会の隅々にまで刻まれ ていた。沖縄の要職に他県出身の官僚が送り込まれ、学校では沖縄の 言葉が禁じられ、伝統的な暮らしも蔑まれた。本土の日本人の目には、 豚を飼うことも、女性の手に施される「ハジチ」と呼ばれる入れ墨も、見 下されていたのだ。

東京で勉学に勤しんだ2年の間に、當山は故郷である沖縄の経 済を改善するための理念を打ち立てた。沖縄の市民活動家だった謝花 (じゃはな)昇さんとの交流で影響を受けながら、自身の独学を通じて 導き出した結論は、出稼ぎ労働による沖縄経済の再生だった。沖縄の 人びとが海外で働き、故郷に送金することで、急増する人口と乏しい資 源にあえぐ島の経済を支え、発展へと導くというものだ。

20世紀前半、當山久三はハワ イへの沖縄移民における重要 な役割を果した。

During the early 20th century, Kyuzo Toyama played a pivotal role in Okinawan immigration to Hawai‘i.

Toyama theorized that Okinawan migrant laborers could fortify the Okinawan economy by working abroad and sending money home—spurring growth for the struggling island beleaguered by an expanding population and scant resources.

Upon returning home from Tokyo, Toyama set about convincing others, most notably the governor of Okinawa, Shigeru Narahara, of the merit of his plan and the right of Okinawans to follow the example of mainland Japanese and emigrate. “Toyama asked, ‘If the mainlanders can emigrate, why can’t we, the Okinawans, emigrate?’” explains Masato Ishida, director of the Center for Okinawan Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “Okinawans deserve the same kind of freedoms.”

Eventually, the governor reluctantly agreed, and Toyama gathered an intrepid group of young men, ages 21 to 30, to relocate to Hawai‘i.

While daring in his ambition and verve, Toyama seemingly did not account for the harsh reality that awaited these migrants. Arriving on O‘ahu on January 8, 1900, the 26 immigrants quickly found themselves confronting a climate of hardship and oppression. Bound to labor contracts on sugar plantations, they toiled under a heavy sun and hot whip, enduring brutal working conditions worsened by the discrimination they faced from the mainland Japanese workers on the plantations. “Emigration didn’t happen in a vacuum,” Kaneshiro says. “Okinawans were immigrant laborers within Hawai‘i’s own colonization by the United States.”

According to Lynette Teruya, the Okinawan Studies librarian at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, the way Okinawans talked and dressed set them apart from the naichi (mainland Japanese) communities that immigrated to Hawai‘i before them, starting in 1868. “The Okinawans were the newcomers in an already-established Japanese community,” Teruya says. “Some of them were made to feel embarrassed about their practices.”

Nevertheless, Okinawans continued to immigrate to Hawai‘i, including Toyama, who arrived in 1903. By 1924, over 16,000 Okinawans had made the journey. Today, their descendants continue to explore the complexities of Okinawan identity while navigating life far from their ancestral homeland. “I grew up hearing how important it was to be Okinawan but not knowing exactly what that meant,” says Kaneshiro, who was born in Hawai‘i but whose grandparents are all from Okinawa.

Since World War II, when the Nisei (second generation) of naichi and Okinawans banded together to

東京から故郷へ戻ると、當山は周囲を説得することに乗り出す。 中でも奈良原繁沖縄県知事に対し、自身の構想の意義を訴え、沖縄の 人びとにも本土の日本人と同じように移民の道が開かれるべきだと説 いた。當山は「本土の人間が移住できるのに、なぜ沖縄の人間が移住 できないのか」と問いかけた。ハワイ大学マノア校沖縄研究センターの 石田正人所長は「沖縄の人びとにも、同じ自由が認められて当然なの です」と語る。

やがて知事は渋々ながらも同意した。そして、ハワイへの移民を 希望する21歳から30歳までの勇敢な若者を當山が集めた。

野心と情熱を抱いていた當山だったが、移民たちを待ち受ける 過酷な現実が十分に見えていなかったようだ。1900年1月8日、オア フ島に到着した26人の青年を迎えたのは、厳しい試練と抑圧の現実 だった。彼らは砂糖農園との労働契約のために、灼熱の太陽の下、容赦 ない鞭に耐えながら働き続けた。さらには、同じ農園で働く本土出身の 日本人労働者による差別にも苦しめられる。「移民は、さまざまな要因 があって起こったものでした」と、カネシロさんは語る。「沖縄出身者は、 アメリカによるハワイの植民地化の渦中に移民労働者として巻き込ま れていったのです」

ハワイ大学マノア校の沖縄研究専門司書であるリネット・テルヤ さんによると、沖縄からの移民は、その話し方や服装から、1868年以 来ハワイに移住していた内地(本土)の日本人とは明らかに異なってい たという。「沖縄の人たちは、すでに確立していた日本人社会において 新参者でした」と指摘するテルヤさん。「沖縄からの移住者は、異なる文 化や習慣のせいで、恥ずかしい思いをすることもあったのです」

それでも沖縄の人びとのハワイへの移住は続いた。當山自身もそ のひとりとして1903年にハワイの地を踏んだ。1924年までに、その数 は1万6,000人を超える。時は流れ、彼らの子孫たちは、祖先の地を遠 く離れながらも、自らの沖縄人としてのアイデンティティの複雑さと向 き合い続けている。「沖縄人であることがどれほど大切なのか、小さい 頃からずっと聞かされてきました。でもそれが具体的に何を意味するの かは、よくわかりませんでした」とカネシロさんは話す。彼はハワイで生 まれたが、祖父母はみな沖縄出身者だ。

第二次世界大戦では、内地系と沖縄系の二世たちが団結し、歴 史に名を刻む「第442連隊戦闘団」に加わった。アメリカ軍史上にお いて、最も多くの勲章を受章した同部隊の活躍により、ハワイ生まれの

多くの沖縄出身の女性た

ちは、写真撮影時にハジ チを隠すことを余儀なく された。写真提供:ジョ ディ·マトス

Many Okinawan women chose to cover their art when being photographed. Image courtesy of Jodie Matos.

form the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team—the most decorated military unit in American history—divisional tensions between Hawai‘i-born Okinawans and Hawai‘i-born Japanese have diminished. “There’s been a change in attitude about what it means to be Okinawan,” Teruya says. “People really started to feel proud.” That pride has blossomed into annual Okinawan fairs, leadership summits, and dedicated cultural groups throughout the state, many of which celebrate Toyama’s legacy.

While Okinawan heritage is a source of pride for many of Okinawan descent in Hawai‘i today, Toyama remains a more complex subject—his legacy intertwined with the histories of two colonized island nations, both shaped by migrant labor. “Toyama

沖縄系と本土系日本人の間にあった隔たりは、次第に和らいでいった。

「沖縄人としての自覚が変わり始めたのです」とテルヤさんは言う。「多 くの人たちが、沖縄人であることを誇りに思うようになりました」。その 誇りは、毎年開催される沖縄フェスティバルやリーダーシップ・サミッ ト、また州内各地の沖縄文化継承団体の設立などへと繋がっていった。 そして、その多くの活動が、今もなお當山の功績を称え続けている。

今日のハワイでは、多くの沖縄系住民にとって沖縄のルーツは 誇りの根幹だ。しかし、當山の存在はそれだけでは語れない。彼の遺 したものは、移民労働によって築かれた2つの植民地化された島国の 歴史と深く絡み合い、単なる偉業の物語では済まされない複雑さをは らんでいる。「當山は、政治権力に立ち向かうことを恐れなかった」と石 田所長は語る。彼の文書や提言、そして揺るぎない指導力は、ハワイに

女性の手に入れ墨を施す「ハジチ」といった沖縄の伝統文化 は、ハワイに移住した日本人から否定的な視線を向けられる ことが多かった。三線奏者KUNIKO(写真:新垣欣悟)

Okinawan cultural practices such as hajichi, the tattooing of a woman’s hands, were often frowned upon by the early Japanese population in Hawai‘i. Image by Kingo

Arakaki of the sanshin artist KUNIKO.

文 化

沖縄人としての誇りは、毎年 開催されるフェスティバルや リーダーシップ·サミット、ま た州内各地の沖縄文化継承 団体の設立などへと繋がって いった。ホノルルを拠点に活 動する非営利団体「御冠船歌 舞団」のメンバー。(写真:アイ フク·リッジリー)

Okinawan pride has blossomed into annual fairs, leadership summits, and cultural groups throughout Hawai‘i. Image by IJfke Ridgley of a member of the Honolulu-based nonprofit Ukwanshin Kabudan.

was not afraid of challenging political authorities,” Ishida says, emphasizing the significance of his writings, advocacy, and leadership in guiding immigrants to Hawai‘i. “In that sense, he is a symbol of freedom for Okinawans.”

Still, Kaneshiro cautions, “It’s very easy for us to romanticize the work that Toyama did. It’s important to really closely examine the motivations and the climate around how these events happened.”

Yet for the tens of thousands of Okinawan descendants born in Hawai‘i, Toyama’s impact is undeniable. “I’m grateful that he made that effort,” Teruya says. “Without him, the Okinawans probably wouldn’t have been here.”

For Toyama, the man who started it all, life ended in 1910, shortly after securing a seat in the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly. His ashes were interred at the Mililani Memorial Park on O‘ahu.

Today, he is honored with statues in his hometown of Kin and on O‘ahu. In Kin, Toyama’s statue faces Hawai‘i, his stone eyes challenging the vast distance between.

渡った沖縄の人びとに新たな未来への道を示した。「そういう意味で、 彼は沖縄人にとって、自由そのものを象徴する存在なのです」

とはいえ、カネシロさんは強調する。「當山の功績を美化するのは 簡単です。しかし、彼がどのような動機で動き、どのような時代に生きて いたのか、それを冷静に見極めることが、とても重要なのです」

それでも、ハワイに生まれた何万人もの沖縄系住民にとって、當 山の影響は疑う余地がない。「彼の尽力に感謝しています」とテルヤさ んはしみじみと語った。「もし彼がいなければ、沖縄の人びとが、ここハ ワイの地に根を下ろすことはなかったかもしれません」

沖縄移民の歴史を動かした當山の人生は、1910年に幕を閉じ た。沖縄県議会の議員となった矢先のことである。遺灰はオアフ島のミ リラニ・メモリアルパークに葬られた。今日、當山の故郷である金武町 とオアフには銅像が建てられ、その功績を称えている。金武町に立つ 銅像の瞳は、遙かなるハワイを見据え、その隔たりを越えようとするか のようだ。

BY WATARU OSHIRO

大地を映す一皿

A TASTE OF PLACE

TEXT BY PAUL SEAN GRIEVE

TRANSLATION BY AKIKO MORI CHING

IMAGES BY WATARU OSHIRO

南城の霧に包まれた山あいに佇むレストラン。

沖縄の大地と森、そして珊瑚の海で育まれた 豊穣の恵が珠玉の料理に生まれ変わる。

Amid the misty peaks of Nanjo, a restaurant celebrates the bounty of Okinawa’s farms, forests, and coral seas.

The morning in Nanjo is overcast, and as a fine drizzle falls from the low-hanging clouds, chef Norihiko Hinata watches a long, narrow gyosen (Japanese fishing boat) sputter toward the dock at Umino Fishing Port. He banters amicably with the boat crew while the dock workers rinse and sort the day’s catch in preparation for the morning auction.

Ambling along the orderly rows of fish displayed in ice-filled trays on the cement floor, Hinata inspects the offerings. Heeding the piercing blast of a whistle, he joins the other buyers around the auctioneer, whose cap and uniform are embroidered with the logo of the

曇り空の南城の朝、低く垂れこめた雲から細かな霧雨がしとしとと降 りそそぐ。シェフの日向紀彦は、細長い漁船がぷつぷつとエンジン音を 響かせながら海野漁港の岸へ向かう様子を見つめている。船が接岸 すると、彼は船員たちと気さくに言葉を交わす。その傍らでは、港の作 業員たちが水揚げされた魚を洗い、仕分けし、もうすぐ始まる競りの準 備を進めている。

日向さんは、セメントの床に並べられた氷詰めトレイの間をゆっ たりと歩きながら、整然と並ぶ魚を丹念に見て回る。甲高い笛の音が鳴 り響くと、競り人を囲んでいる買い手たちの輪に彼も加わる。競り人の 帽子や制服には、知念漁業協同組合のロゴが刺繍されている。競りが

食

日向紀彦シェフは毎朝

海野漁港に足を運び、

鮮魚を仕入れている。

Chef Norihiko Hinata visits Umino Port every morning in pursuit of fresh catch.

Chinen Fisheries Cooperative. The bidding commences, and the auctioneer, his tone brisk and business-like, calls out each tray one by one, naming a price.

When the auctioneer arrives at a tray of three large kobanzame (remora)—the fish Hinata plans to prepare that afternoon for patrons of his restaurant, Be Natural—Hinata drops his tag. He is the only bidder for his catch of choice, and, when the auction ends, he bows with gratitude and collects his prize.

Hinata has been attending the auction at Umino Port every morning for more than 20 years. Since opening Be Natural in 2000, his careful selections—at the fish auction and beyond—have garnered the restaurant a loyal following and a well-earned reputation for outstanding quality, unparalleled freshness, and a commitment to both tradition and innovation. (Reservations are required, and the restaurant is unable to accommodate vegetarian requests.)

Waving farewell to the fishermen, port workers, and other bidders, Hinata turns out of the parking lot,

始まると、競り人は、一つひとつのトレイを指差しながら、独特のキビキ ビとした口調で価格を唱えていく。

競り人が、三尾の大ぶりのコバンザメが並ぶトレイの競りを始め ると、日向さんは迷うことなく札を投げ入れた。その日の午後、自分のレ ストラン「Be Natural」で出す料理に使うつもりだ。入札は彼一人のみ だった。競りが終了すると、日向さんは感謝の気持ちを込めて一礼し、 戦利品のコバンザメを受け取った。

日向さんは20年以上にわたり、毎朝この海野港の競りに通ってい る。2000年に「Be Natural」を開店して以来、魚のみならず、あらゆる食 材選びにおける確かな目利きが評判を呼び、常連客がレストランに足を 運んでいる。傑出した料理と抜群の鮮度、伝統を大切にしながらも柔軟 に新しい感性を取り入れるスタイルが店の人気を支えているのだ。(レス トランは予約制で、ベジタリアン対応はしていない) 漁師たちや港の作業員、そして競りに参加していた顔馴染みに軽 く手を振りながら、日向さんは駐車場を後にした。細い舗装道路の両脇 には、立派なフクギの木々が立ち並ぶ。国道331号線を西へと車を走ら

「 Be Natural」のメニュー

は、日向さんと小規模生 産者との信頼関係の上に 築かれたものだ。

The menu at Be Natural is built on Hinata’s relationships with smallscale producers.

driving past the stately fukugi trees lining both sides of the narrow, paved road. Heading west on Route 331, he soon arrives at his next destination, an unassuming herb garden about 30 paces on each side, where he cuts lemongrass, peppermint, and basil—herbs destined for the French- and Italian-accented fare at Be Natural. Located a few kilometers west of the fishing port, the herb garden belongs to his wife’s family and serves as her family’s vegetable plot.

The harvest from this little field is a vital component of Hinata’s ever-evolving ingredient base, which is rooted in seasonality and combines a carefully selected mix of yields from regional producers, local farms, and nearby farmers markets. Together they are a testament not only to the trusted relationships Hinata has cultivated with local farmers and fishermen but also the strength, spirit, and self-sufficiency of the island’s food system as a whole.

“When I use milk, it’s from Tamaki Farm right here in Nanjo,” Hinata says. “And I use Miyagi Farm eggs,

せ、ほどなくすると縦横20メートルほどの小さなハーブ園にたどり着い た。ここで、彼はレモングラスやペパーミントそしてバジルを収穫する。

それは、「Be Natural」で出すフランスやイタリアのエッセンスを織り 交ぜた料理に欠かせない。漁港から数キロ西に位置するそのハーブ園 は、彼の妻の家族のもので、家庭菜園として使われている。

この小さな畑からの恵みは、日向さんの進化し続ける食材の土台 を支えている。その根底には、それぞれの季節ならではの食材を中心に、 地域の生産者や地元の農園、近隣のファーマーズマーケットから厳選し た素材を自分の料理に取り入れるという彼の姿勢がある。それは、日向 さんが地元の農家や漁師と築いてきた信頼関係であり、同時に沖縄と いう土地の食文化が持つ力強さ、逞しさ、そして自立精神を映し出して いる。

「牛乳は、ここ南城市にある玉城牧場の牛乳を使っています」と、 日向さんは語る。「卵は宮城農場のものを、肉類は島内各地の小規模生 産者による肉から厳選したものを使っています」

「国澤さんのような農家と一緒に仕事をすることで 私の料理の幅もぐっと広がるのです」

日向紀彦、シェフ

“Working with farmers like Kunisawa-san lets me take my creations to another level.”

—Norihiko Hinata, chef

日向さんの手によって、そ

の日水揚げされた魚は、沖

縄の大地と海の恵みを映 す一皿へと生まれ変わる。

Hinata transforms the day’s catch into an expression of the surrounding land and sea.

as well as meat from various small-scale producers around the island.”

Hinata’s final stop before heading to the restaurant is a nearby greenhouse at the foot of a steep, forested ridge. The rain intensifies, and a dense gray mist shrouds the mountains in the distance. Hinata gets out of the car and stretches, then bends down over a long, narrow clay pot near the entrance to clip fresh rosemary, which he’ll later use to season his renowned focaccia.

Greeting him at the doorway of the greenhouse is Takao Kunisawa, a 74-year-old farmer who produces a lush bounty of edible flowers and microgreens under contract with Be Natural. Kunisawa holds the door open for Hinata before lifting the bug netting from a tray of baby greens.

“These add a powerful snap to salads,” Hinata says as he trims leaves from the planter of komatsuna (Japanese mustard spinach), gently dropping them into a large bowl.

レストランに戻る前、日向さんが最後に立ち寄ったのは、森の急 な斜面の麓にある温室だ。雨脚は強まり、遠くの山々は灰色の濃い霧 に包まれている。車を降りた日向さんは軽く伸びをした後、入口近くに 置かれた細長い素焼きの鉢に身をかがめ、ローズマリーの新鮮な葉を 摘み取る。このハーブは、レストランの名物であるフォカッチャに香りを 添えるものだ。

温室の入り口で日向さんを迎えたのは、74歳の国澤孝夫さんだ。 国澤さんは、「Be Natural」の契約農家で、色鮮やかな食用花やマイク ログリーンを栽培している。国澤さんは日向さんのためにドアを開け、ベ ビーリーフを栽培しているトレイにかけられた防虫ネットを持ち上げた。 「この小松菜を加えると、サラダにパリッとした食感が出るんで すよ」と言いながら、日向さんはプランターから小松菜の葉を摘み取り、 大きなボウルにそっと入れていく。「でも、暑さと湿気で小松菜は夏には 育たないんです」と国澤さん。「だからこそ、日向さんのように食材の旬 に合わせて料理を考えてくれるシェフがとてもありがたいのです」

“Unfortunately, komatsuna can’t be grown in the summer months—it’s too hot and humid,” Kunisawa adds. “That’s why it’s so important for chefs like Hinatasan to plan their meals around a seasonal menu.”

Hinata moves on to several beds of petunias blooming at the center of the greenhouse. Their coronet-shaped flowers add vibrant color to the salads and desserts he serves as part of the restaurant’s fixed-course menu. “There is no way I could afford to buy flowers like this from a commercial grower,” Hinata says. “Working with farmers like Kunisawa-san lets me take my creations to another level.”

At lunchtime, the restaurant beckons with a worn, lived-in charm. Nestled on a secluded hillside and shaded by a dense row of tall hydrangea shrubs, it seems to merge with the landscape. A sanctum of tranquility and character, the dining room and open kitchen are an ever-changing tableau that Hinata has lovingly filled with personal touches and the abundance of the season.

The kobanzame arrives in the form of an artful sashimi salad, tucked under a delicate scattering of microgreens and petunias from Kunisawa’s greenhouse and flavored with a sauce made from locally grown cucumber and papaya. Beverages are infused with the herbs from Hinata’s wife’s family garden. When the meal ends, it’s with a delicate pudding made from the milk and eggs Hinata sources from his Okinawan suppliers, served with a scoop of ice cream made with lemongrass from the garden. Like the meal before it, the dessert bears the essence of the land it came from— zesty, green, and alive.

More than just a culinary experience, every dish Hinata creates is a quiet tribute to the changing seasons and the hands that fish, farm, and forage. At its heart is a chef who acts as both curator and steward, one who knows that the foundation of flavor lies in the soil, the sea, and the untold story behind every ingredient on the plate.

日向さんが次に向かったのは、温室の中央で咲き誇るペチュニア の苗床だった。その王冠のような花は、レストランのコース料理で出す サラダやデザートに鮮やかな彩りを添える。「こういう花を商業ベース の生産者から仕入れるのは、コスト的に無理なんです」と日向さんは語 る。「国澤さんのような農家と協力することで、私の料理の幅もぐっと広 がるのです」

昼どきになると、レストランは時を重ねてきた場所ならではの温 もりと魅力に包まれる。人里離れた丘の中腹にひっそりと佇み、紫陽花 の茂みに囲まれて、まるで風景の一部になったかのように溶け込んでい る。日向さんのこだわりと季節の恵みが随所に息づいたダイニングルー ムとオープンキッチンには静けさと個性が満ち、豊かで変化に富んだ空 間が広がっている。

コバンザメは、彩り豊かな刺身サラダとなって登場する。国澤さ んの温室で育まれたマイクログリーンとペチュニアがあしらわれ、地元 産のキュウリとパパイヤを用いたソースが繊細な味わいを引き立てる。

飲み物には自家栽培のハーブが香りを添えている。食後のデザートは、 沖縄の農家の牛乳と卵で作った繊細な味わいのプリンと紅芋パウダー を散らしたレモングラスのアイスクリーム。家庭菜園で育てたレモング ラスの風味がやさしく香る一品だ。食事と同じように、デザートにもこの 土地の恵みが息づいていて、爽やかで瑞々しく、生き生きとした味わい が広がる。

日向さんが手掛ける料理を食することは、単なるグルメ体験には とどまらない。一皿一皿には、季節のうつろいと、海で魚を獲る人、土地 を耕す人、山野に分け入って食材を探す人の手仕事への静かな賛辞に 満ちている。そこでは、シェフは素材の魅力を見極め、案内する役目を担 う。彼は知っているのだ。味わいの本質は、大地や海、そして皿の上に広 がるすべての食材が秘めている物語から生まれるということを。

FAMILY INGREDIENTS

TEXT BY LAUREN

MCNALLY

IMAGES BY GERARD ELMORE TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

代々受け継いできた製法で、ゆし豆腐をはじめと する沖縄の豆腐文化を守り続ける家族の物語 家族が守る島の味

A family preserves Okinawa’s tofu-making traditions, producing yushi-dōfu and other specialties using methods passed down through generations.

Dawn has only just begun to illuminate the windows of the Yamashiro Tofu factory in Motobu village, but 74-year-old chairman Yoshimitsu Yamashiro has already been at work for hours. He stands before a steaming vat of soy milk, scanning the bubbles forming on the surface. With an intuition honed over nearly four decades of tofu making, he watches for subtle signs that it’s time to add the coagulant and seasoning, ingredients that will transform the soy milk into the uniquely Okinawan delicacy of yushi-dōfu.

When the moment arrives, Yoshimitsu transfers some of the milk into a bucket containing nigari

本部町にある山城とうふ店の工場の窓辺が、朝の光でほんのり 明るくなり始める。だが、74歳の会長、山城好充さんは、すでに何時間 も前から作業に取り組んでいた。湯気が立ちのぼる豆乳の大釜の前に 立ち、長年の経験で鍛えられた眼差しで、表面に浮かぶ泡をじっと見 つめている。約40年にわたって豆腐作りに携わり、培った直感を頼り に、山城さんは微妙な兆しを見逃さず、豆乳から沖縄名産のゆし豆腐 を作るための凝固剤と調味料を加える瞬間を見極める。

そして、その瞬間がくると山城さんはにがり(凝固剤)と塩が入っ たバケツに少量の豆乳を移す。その混ぜ合わせたものを大釜に戻すと、

食

毎朝午前2時に工場で作

業を始める豆腐職人の山 城好充さん。

Tofu maker Yoshimitsu

Yamashiro starts work at the factory each day at 2 a.m.

(a coagulant) and salt, then pours the mixture into the vat. Soon the milk begins to coagulate, its skin thickening into pillowy clouds of curd. Using a saucepan as a ladle, he gently scoops the milky-white curds into buckets to cool in a basin of water.

“You get the best texture and consistency by letting it finish cooking [off the heat], like steak continuing to cook after it’s removed from the heat,” explains Narimi Nakazato, Yoshimitsu’s daughter and CEO of the business. Narimi has spent the past several years learning the family’s small-batch tofu-making techniques, but the critical step of adding nigari and salt still rests with her father. Timing is everything: Wait too long, and the savory crust that forms inside the vat will burn, taking the flavor from delicately roasted to overly smoky. “It’s a trade secret,” Yoshimitsu chuckles, noting that he’ll eventually teach Narimi to manage this delicate task.

“Back when my mother originally ran the factory, she used seawater from the bay [instead of nigari and salt],” Yoshimitsu recalls, explaining that the water is

ほどなくして豆乳は固まり始め、まるでやわらかい雲のように浮かび上 がり、おぼろ状に変化していく。ひしゃく代わりの片手鍋で、丁寧にすく い上げた乳白色の擬固物をバケツに移して、水を張った盥(たらい)の 中で冷やす。

「ゆし豆腐は一旦火を止めて、余熱で調理することによって、最 高の食感とやわらかさが生まれるのです。ちょうど焼いたあとのステー キに、余熱でじんわりと火が通っていくように」と、山城さんの娘で店の 代表取締役を務める仲里奈理美さんが説明する。家族が守り続けてき た少量仕込みの豆腐作りを学んで数年になる奈理美さんだが、にがり と塩を加える重要な作業は今も父親が担当しているという。この作業 はタイミングがすべてだ。ほんの少し遅れると、大釜の中にできる擬固 物が焦げてしまい、本来の豆腐のやさしく香ばしい風味が、強い焦げ た香りへと変わってしまう。「これは企業秘密なんだよ」と山城さんは 静かに笑う。そして、この慎重を要する作業もいずれは奈理美さんに教 えて託すつもりだと話した。

「私の母がこの工場を始めた頃は、にがりや塩の代わりに、すぐ そばの入り江の海水を使っていたんだ」と山城さんは懐かしそうに語

具志堅あきのさんは、自身が経営するカフェ&スイーツ店 SOYSOYで、実家の豆腐工場で作られた豆腐を使った料理 や菓子を手がけている。

At SOYSOY, her cafe and sweets shop, Akino Gushiken creates dishes and confections using tofu from her family’s factory.

now too polluted to use for tofu making. His mother, Tomi Yamashiro, began producing tofu in the years after World War II, when the American government distributed soybeans and other provisions to Okinawan citizens to stimulate economic recovery and local industry. At the time, at least three tofu shops operated in the Sakimotobu area; Yamashiro Tofu is the only one that remains.

Distinct from the tofu of mainland Japan, yushi-dōfu is loose, custard-like, and eaten immediately after cooking—typically within a day. At Yamashiro Tofu, the soft curds are sold piping hot, or they’re pressed into dense, hearty shima-dōfu (island tofu). The factory also makes atsuage (deep-fried tofu), as well as raw ingredients for tofu making, and is among the few still producing traditional Okinawan-style tofu by hand.

Like all tofu, the process of making yushi-dōfu begins with soaking and grinding soybeans, then separating them into soy milk and okara, or soybean pulp. The okara is traditionally repurposed as animal feed or used in home cooking, Narimi says—but most of the time, it’s discarded.

“I grew up watching tofu being made, and I saw that a lot of okara is thrown away in the process,” says Yoshimitsu’s eldest daughter, Akino Gushiken. From a young age, Akino loved finding inventive ways to cook with tofu from her family’s factory, an interest that only deepened in adulthood. Eventually she realized she could use the okara to make muffin batter.

“It all started as a hobby,” Akino says of the passion that inspired her to launch Soysoy, a café and sweets shop specializing in tofu-based dishes and confections. “I found it really fun to experiment with delicious ways to use tofu, and as I kept creating different sweets and dishes, I started to feel like I wanted more people to know about the different ways tofu can be used and enjoyed.”

Since opening SOYSOY a decade ago, Akino has grown the business into three locations across the island. “As the daughter of a tofu maker, I dream of expanding internationally,” Akino says. “My dream is to share this incredibly delicious yushi-dōfu—Okinawa’s soul food—with the world.”

Though Japanese food safety regulations limit its sale in many retail settings, small-scale producers continue to make traditional yushi-dōfu, usually selling directly to customers. Today, Narimi has been seeing a revival of this beloved heritage dish—one that reflects the enduring spirit of achikōkō, the Okinawan custom of savoring foods hot and fresh from the source.

る。今ではその海水は汚染され、豆腐作りに使えなくなってしまったと いう。山城さんの母親のトミさんが豆腐作りを始めたのは、第二次世 界大戦後まもなくの頃だった。アメリカ政府が、沖縄の人々に大豆など の物資を配給し、経済復興や地元産業の建て直しを図っていた時代で ある。当時、崎本部地域には豆腐店が少なくとも3軒あったが、今でも 残っているのは山城とうふ店のみだ。

本州の豆腐とは異なり、ゆし豆腐はゆるく、とろんとしたプリンの ような口当たりで、調理後すぐ食べる。たいていはその日のうちに食べ きるものだ。山城とうふ店では、ふわふわのゆし豆腐を湯気が立つほど 熱々の状態で販売しているほか、ゆし豆腐に重しをして作るずっしりと 重みある「島豆腐」も作っている。工場では厚揚げや豆腐作りに必要な 原材料も手がけており、今なお沖縄伝統の手作り豆腐を守り続けてい る数少ない店の一つである。

ほかの豆腐と同じように、ゆし豆腐作りも水に浸した大豆をすり つぶし、豆乳とおから(豆腐粕)に分けることから始まる。おからは昔か ら家畜の飼料として再利用したり、家庭料理に使われたりしてきたが、 今はそのほとんどが廃棄されてしまうのだと奈理美さんは話す。

「豆腐作りを身近に見て育ちましたが、その過程でたくさんのお からが捨てられているのに気づいたんです」と、山城さんの長女である 具志堅あきのさんは語る。小さい頃から、実家の工場で作った豆腐を 使って新しいアイデア料理を試すのが好きだったというあきのさん。大 人になり、その興味はさらに深まったという。やがて、おからを使ってマ フィンの生地が作れることを知った。

「趣味から始まったんですよ」と語るあきのさんは、豆腐を使っ た料理や甘菓子専門のカフェ&スイーツ店SOYSOYを立ち上げた きっかけについて語る。「豆腐のおいしい食べ方をあれこれ試すのが本 当に楽しくて、いろいろなお菓子や料理を作っていたのです。そうこうす るうちに、豆腐にはこんなにたくさんの使い道や楽しみ方があるんだっ てことを、もっと多くの人に知ってもらいたいと思うようになりました」

SOYSOYを立ち上げてから10年、あきのさんは島内に3店舗を 展開するまでに事業を拡大した。「とうふ屋の娘として、いつかは海外 にも広げていけたらと思っています」とあきのさんは語る。「とびきりお いしい沖縄のソウルフードであるゆし豆腐を、世界中の人々に届けた い。それが今の私の夢なんです」

日本の食品衛生規制のために、店頭での販売は難しい。今日、伝 統的なゆし豆腐を作り続けているのは、ごく少数の小規模生産者のみ だ。多くは小売店舗を持たず、直接顧客に販売する方法をとっている。 そういった状況にもかかわらず、奈理美さんは、愛され続けてきた郷土

山城豆腐店

Around late morning, two women appear at the entrance of the factory. Having heard about Yamashiro Tofu through word of mouth, they’ve come seeking the family’s renowned yushi-dōfu. When Narimi tells them it won’t be ready for another hour, the women decide to wait, content to pass the time until it cools enough for her to sell it to them.

の味に再び関心が集まりつつあると感じている。ゆし豆腐の復活は、で きたてを熱いうちにその場で味わうという沖縄の食文化である「アチ コーコー」の心が今も息づいている証なのだ。

そろそろ昼が近づく頃、工場の入り口に二人の女性の姿があっ た。山城とうふ店の評判を口コミで耳にし、家族代々で受け継がれてき たゆし豆腐を買おうとやってきたという。あと1時間ほどかかると奈理 美さんが告げると、女性たちはにこやかにうなずいて、豆腐が冷めるま でゆっくりと待っていた。

ハレクラニ沖縄

家族に受け継がれてきた豆腐作りの伝統手法を守るため、夜明けから 日暮れまで工場に立ち続ける仲里奈理美さん。

on

Narimi Nakazato works from sunup to sundown to carry

her family’s traditional tofu-making methods.

ヤシの木々の間から

AMONG THE PALMS

TEXT BY TOM FAY

TRANSLATION BY MUTSUMI MATSUNOBU

IMAGES BY WATARU OSHIRO

自然のサイクルと古来の伝統を尊重しながら 伊平屋島に自生する植物で民具を編み上げる

元ファッションスタイリスト

Honoring the cycles of nature and the traditions of old, a former fashion stylist weaves folk tools from the

Gentle waves lap the sandy white shores of Iheya island, and colorful fish fill the fringing reefs beneath the surface of its startlingly turquoise waters. You might expect a steady stream of sunbathers and snorkelers in such a picturesque place, but not here. Isolated by an 80-minute ferry ride from the small port of Unten on Okinawa’s main island, and with only two sailings a day (weather permitting), few tourists ever venture to the idyllic hideaway that is Okinawa’s northernmost inhabited island. And with fewer than 1,500 residents, it’s no surprise to find Iheya’s pristine beaches conspicuously empty.

白い砂浜に穏やかな波が打ち寄せる伊平屋島。鮮やかなターコ イズブルーの海では色とりどりの魚が珊瑚礁の間を泳ぎ回ってい る。その美しさから、日光浴やシュノーケリングを楽しむ人でにぎ わっていても不思議ではないが、ここは違っているようだ。沖縄本 島の運天港からフェリーで80分、1日2便(天候次第)という限ら れたアクセスのため、この静かな楽園を訪れる観光客はあまりい ない。沖縄県最北端の有人島であり、人口は1,500人にも満たな い伊平屋島の手付かずの浜辺には、今日も人の姿はほとんど見 当たらない。

native flora of Iheya island.

伊平屋には伝統工芸に適 した葉が扇状の特有なヤ シが自生している。

Iheya is home to a unique variety of fan palm that is ideal for traditional handicrafts.

But that is just how Masami Koreeda likes it. A former fashion stylist who now crafts traditional folk tools on the island, she left Tokyo over a decade ago in search of the slow life. “I liked living in Tokyo,” she says with a warm smile. “But I was so busy working for a fashion magazine, sleeping for only three or four hours every night. It was exhausting. I realized it was time for a change of pace.”

A native of Kagoshima, the southern Kyushu city known for its active volcano, Koreeda would frequent the nearby island of Yakushima to visit her close friend from high school. “I fell in love with the island lifestyle,” she explains. “I love surfing and have always enjoyed the laid-back vibe of places like Thailand and Hawai‘i.” So when it came to searching for a new place to call home, Okinawa was a natural choice.

Koreeda first moved to the small island of Irabu in 2011 to run a minshuku (bed and breakfast), and it

活火山の桜島で知られる九州南部の都市、鹿児島市出身の是枝 さんは、高校時代の親友に会うために、近くの屋久島へ頻繁に足を運 んでいた。「あの島の生活にすっかり魅せられたのです」と説明する。「私 はサーフィンが大好きで、タイやハワイのようにのんびりとした空気感を いつも楽しんでいました」。そのような彼女が次の暮らしの場に沖縄を 選んだのは、ごく自然なことだった。 種水土花

だが、それは是枝麻紗美さんの望んだ暮らしだった。かつては、 東京でファッションスタイリストとして忙しく働いていた。今は、この島 で昔ながらの民具作りに向き合う日々を送っている。スローライフを求 めて東京を離れたのは10年以上前のこと。「東京の暮らしも好きでし たよ」とやわらかく微笑む。「でもファッション誌の仕事に追われて、毎日 3〜4時間の睡眠しかとれない日々が続いていました。本当に疲れ果て ていて、そろそろ暮らしのリズムを変える時だと思ったのです」

スローライフを求めて東京から沖縄に移り住んだ是枝さん は、伊平屋島の穏やかな時の流れに安らぎを見出した。

Koreeda relocated from Tokyo to Okinawa in search of a slower pace of life, finding solace in the rhythms of Iheya island.

was there that she began to develop an interest in the local crafts. “When I visited neighboring Miyakojima, I would find discarded old baskets and other things, and it turned out that absolutely no one was making them anymore,” Koreeda recalls of these traditional items and tools, which were crafted from the leaves of kuba, a type of fan palm abundant in the hills and forests of Okinawa. “So I took them home and deconstructed them to see how exactly they had been woven and made.”

Highly valued for its strong, water-resistant leaves, kuba has long been prized both as a crafting material and for its connection to utaki, or Ryūkyūan sacred sites. In Okinawa, where spiritual practice is rooted in natural settings more than the shrines and temples common in mainland Japan, the kuba growing in these revered places have also come to be associated with the divine. But for Koreeda, it is the simple, traditional utility of her creations, along with their natural and local origin, that she hopes will resonate most with those who use them.

After five years on Iruba, Koreeda relocated to Iheya, finding even greater solace in the island’s mellow charms and natural landscape, where forested mountains run like a spine from tip to tail along its spindly and narrow 14 kilometers. Within the handful of small and sleepy settlements dotted along its eastern coast, ancient local festivals are very much a part of daily life, and the community still prays for plentiful rice harvests and hearty brews of awamori.

Although Iheya is home to a unique type of kuba—a fine, durable variety ideal for Koreeda’s craft—only one other resident was making use of it when Koreeda arrived on the island: an elderly hatmaker. The two are now good friends, regularly venturing into the mountains together to gather kuba leaves with a few local ojisan (elderly men).

Koreeda’s brand, Syumidoka—a name formed from the Japanese characters for “seed,” “water,” “soil,” and “flower”—alludes to nature’s cyclical regeneration of resources. Her wide variety of products are crafted from materials found close by: kuba leaves are woven into baskets, dried grasses serve a multitude

是枝さんが伊良部という小さな島に移住したのは2011年のこ と。民宿を経営するために移り住んだが、島で生活するうち、次第に地 元の伝統工芸に心惹かれた。「すぐ隣の宮古島を訪れた時、古い籠など が捨てられているのを目にしたのですが、作っている人はもう誰もいな いことを知りました」。是枝さんは、沖縄の山や森のあちこちに自生する クバ(ビロウ)というヤシの扇状の葉で作られた伝統的なものや道具に ついて思い返していた。「で、家に持ち帰って分解して、実際どのように 編まれ、作られているのかを調べてみたのです」

葉が丈夫で水に強いため、クバは工芸用の素材として、また「御嶽 (うたき)」と呼ばれる琉球の聖地とのつながりからも、大切にされてき た。本土のように神社や寺院が信仰の中心ではなく、沖縄には自然を 崇拝する風土が息づいている。そのため、聖地に自生するクバも、神聖 なものと考えられている。だが是枝さんは、そういった象徴性以上に、 彼女の作る民具のシンプルかつ伝統的な実用性、そして地元の自然の 産物であることを使い手に感じて欲しいと願っている。

伊良部島での5年間を経て、是枝さんがたどり着いたのは伊平屋 島だった。穏やかで魅力あふれる島、そして森に覆われた山々が島の端 から端まで14キロメートルにわたって背骨のように細長く連なる自然 の風景。そこで、是枝さんは、さらに深い安らぎを見出したのだ。東海岸 沿いに点在する小規模で静かな集落には、古くから続く地元の祭事が 暮らしの中に息づいており、今でも米の豊作と泡盛の芳醇な醸造を願 い、日々の祈りを大切にしている。

伊平屋島には、是枝さんの工芸に適した上質で丈夫な種類の クバが自生している。しかし、彼女が島に移り住んだ当初、このクバを 使っていたのは、地元の年配の帽子職人ただひとりだった。今では、そ の職人と親しくなり、地元のおじさんたちと一緒に定期的に山へ出かけ て、クバの葉を採集しているという。

「種」「水」「土」「花」という4つの漢字から成る是枝さんのブラン ド名「種水土花(しゅみどか)」は、資源を循環させていく自然の営みを 示唆しているという。彼女の作品は多種多様であるが、どれも身近な素 材から丁寧に作られている。クバの葉は籠に、乾燥させた草はさまざま

ファッションスタイリスト

だった是枝さんの作品に は、現代的な感性が息づ いている。

A former fashion stylist, Koreeda imbues her craft with a contemporary flair.

of purposes, seashells become charming ornamentation. As Koreeda puts it, her aim is “to make practical and beautiful items that put no pressure on the earth and that, perhaps, will one day return to nature after serving their use.”

It’s an ethos that echoes life on Iheya as a whole, where the culture moves in step with the rhythms of nature. Youth leave the island in their mid-teens to continue their schooling, often returning years later to harvest mozuku (edible seaweed), the island’s main industry, and to start families of their own. This natural ebb and flow remains a constant, helping to sustain the island’s traditions and ways of life that have barely changed for generations. For Koreeda and others, the quiet allure of Iheya remains—for now, at least—a well-kept secret.

な用途に使われ、貝殻は魅力的な装飾品へと姿を変える。「地球に負担 をかけず、役目を終えた後はいつか自然に還る、そんな実用的で美しい ものを作ることが目標なのです」と、是枝さんは語る。

それは、島全体の暮らしに通じる気風でもある。伊平屋では、文 化そのものが自然のリズムと寄り添うように息づいている。若者たち は、進学のために10代半ばで島を離れるが、数年後には島の主要産業 であるモズク漁に携わるために島に戻り、家庭を築く者が多い。この自 然と繰り返される流れは永続的で、世代を超えて受け継がれる島の伝 統と暮らしを支えてきたのだ。是枝さんにとって、そして島に住むほかの 人々にとって、伊平屋の静かな魅力は、少なくとも今のところは、まだあ まり知られておらず、とっておきの場所としてしっかりと守られている。

沖縄・恩納村の美しい海辺に開業した ハレクラニ沖縄はこの神秘の楽園アイランドがもつ 自然のエネルギーと、最高峰のラグジュアリーを 融合させた唯 無二のリゾートです。

Located along the beautiful coastline of Onna Village in Okinawa, Halekulani Okinawa is an unrivaled resort that seamlessly combines the natural energy of this mystical paradise with the pinnacle of luxury.

ハウス ウィズアウト

HOUSE WITHOUT A KEY

A taste of Hawai‘i at Halekulani Okinawa

The iconic House Without A Key, a cherished favorite at Halekulani in Hawai‘i, is equally beloved at Halekulani Okinawa, captivating guests with its warm hospitality, exceptional cuisine, and open-air ambiance. Start the day with a blissful breakfast buffet on the terrace, where a gentle sea breeze and morning light set the perfect tone. With nearly 100 colorful dishes to choose from—like freshly prepared pasta, Okinawan specialties, Japanese dishes, hotel-made bakery items, a madeto-order egg station, and seasonal desserts crafted by our pastry chefs—diners’ palates are in for a treat. Daily smoothies and handcrafted latte art add a touch of elegance to the morning.

In the evening, indulge in a gourmet feast, accompanied by the soothing sounds of live entertainment. Inspired by Hawaiian flavors, the menu ranges from classic poke and garlic shrimp to hearty barbecue plates, innovative dishes using local Okinawan ingredients, and a variety of healthy vegan options. Spend special moments with family and friends in a setting where the spirit of Hawai‘i and beauty of Okinawa come together to create unforgettable memories.

ハワイで長く愛されてきた伝説のレストラン「ハウス ウィズアウト ア キー」。その心地よい空間は、ここハレクラニ沖縄でも開業以来 多くのゲストに親しまれています。

朝の光が降り注ぐテラスで海風を感じながら楽しむ朝食ブッ フェは至福のひととき。日替わりのパスタや沖縄の郷土料理、和 食、ホテルメイドのベーカリー、目の前で仕上げるエッグステー ション、そしてホテルメイドの季節のデザートなど、常時約100 種類ほどの彩り豊かな料理が食欲をそそります。さらに、日替わ りのスムージーやバリスタが心を込めて描くラテアートが優雅 な朝のひと時を演出します。

夜は、心地よいライブエンターテイメントの音楽が響き渡る中、 美食の饗宴が幕を開けます。ハワイアンテイストをベースに、定番 のポキやガーリックシュリンプ、豪快なBBQプレートをはじめ、地 元沖縄の食材を活かしたオリジナルメニュー、そしてヘルシーな ヴィーガンメニューまで、多彩なラインナップが楽しめます。

大切な人と、家族と、友人と。ハワイと沖縄の魅力が融合した 空間で、特別なひと時をお過ごしください。

スパハレクラニ

SPAHALEKULANI お客さまを魅了してきたスパハレクラニのトリートメント

Captivating treatments at SpaHalekulani

Hawai‘i and Okinawa share a deep-rooted tradition of mystical healing spirit. At SpaHalekulani, we draw from these time-honored practices and healing methods to create personalized treatments that transport guests to a state of pure relaxation.

Before a treatment or massage, guests unwind in our natural hot spring, allowing its soothing warmth to calm the mind and body. Our treatments incorporate traditional Okinawan ingredients known as “nuchigusui” (life medicine) to restore the body’s natural balance.

Forget the hustle and bustle of everyday life and indulge in a supreme moment of relaxation for both body and soul.

古くより幻想的なヒーリング・スピリットが受け継がれてきた ハワイと沖縄。スパハレクラニでは、この2つの楽園で培われてき た癒やしのメソッドが融合したスパ体験を提供し、お客さまひと りひとりに寄り添ったパーソナルな施術を行います。

トリートメントやマッサージの前に、スパ内に設けた天然温泉 でゆったりお過ごしいただき「命薬(ぬちぐすい)」として親しま れてきた沖縄の伝統的な素材を取り入れたトリートメントは、奥 深いリラクゼーションの境地へといざないます。

日常の喧騒を忘れ、心も身体も解き放つ、極上のひとときをご 堪能ください。

ハレクラニ沖縄

エスケープ

HALEKULANI OKINAWA ESCAPES

沖縄独自の生活を体験「長寿の知恵」

Experience the unique lifestyle of Okinawa and its “Secrets of Longevity.”

The hotel offers five “Halekulani Okinawa Escapes” programs in which guests can experience “the island of longevity,” which has gained attention worldwide for its traditional lifestyle and dietary habits.

To “Discover the Island’s Umui (Spirit),” guests engage in the practice of mindful wellness, reflecting on their past and present, and savor meals deeply rooted in the concept of “food as medicine,” derived from our local culinary traditions.

To “Discover the Island’s Mabui (Soul),” guests enjoy a wellness experience that teaches the fundamental “kata” of karate, a martial art with a rich history dating back to the Ryūkyū Kingdom era, which is also integrated as a health practice in daily life. Wrap up your day with a healthy meal and a spa treatment infused with traditional Okinawan ingredients.

ハレクラニ沖縄では、伝統的な生活や食習慣などの理由が解明 されつつある、ブルーゾーンの一つとして世界的に注目されてい る“長寿の島”である沖縄を体感いただける「ハレクラニ沖縄 エ スケープ」として5つのプログラムをご用意しています。 「この島の想い(うむい)に触れる」では、ご滞在中にホテル外 で自身の過去・現在を見つめ、未来を創造するマインド・ウェルネ スの実践と医食同源に根付いたお食事をご堪能いただけます。 「この島の魂(マブイ)に触れる」では、琉球王国時代から盛ん な空手の歴史と日常生活で健康法として取り入れることができ る基本の”型”を学び、ヘルシーなお食事や沖縄の食物を取り込 んだスパトリートメントで一日を締めくくるウェルネス体験をお 楽しみいただけます。

HALEKULANI OKINAWA ESCAPES

神秘的な沖縄の美しさを体験

Experience the mystical beauty of Okinawa.

“Discover the Island’s Glow” and two new programs, “Connect with Nature in Yanbaru” and “Wade Through the Waters of Yanbaru,” are three precious experiences, sure to delight even the most discerning travelers.

Guided by a local naturalist, guests “Discover the Island’s Glow” with an excursion into the Yanbaru National Park shortly before sunset. After climbing in a kayak and paddling through mangrove trees, guests will witness a dazzling display of twinkling fireflies, creating a truly enchanting ambiance and unforgettable experience. This program is available from July through September, making the excursion even more unique and exclusive.

Available exclusively to guests of Halekulani Okinawa, “Connect with Nature in Yanbaru” and “Wade Through the Waters of Yanbaru” are unique private excursions that encourage travelers to harness the healing power of nature while exploring Yanbaru, one of Japan’s newly recognized UNESCO World Natural Heritage Sites.