Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Faust

Fassang László koncertje

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Faust

László Fassang in concert

Müpa – Bartók Béla Nemzeti Hangversenyterem

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall OKTÓBER 10. | 19.30

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Faust – némafilm orgonakísérettel

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau 99 éve, 1926-ban bemutatott némafilmje a korszak egyik legköltségesebb és legtöbb újszerű technikai megoldást felvonultató alkotása volt. „A Faust-film varázslat” – írta a film budapesti bemutatója után a Színházi Élet című lap. „Goethe a Faust-mondával egy bábszínházban találkozott. A bábszínház primitív históriájától a goethei tragédiáig hosszú az út, de nem fejeződött be. A folytatása: a Faust-film.” Az elbeszélt történet ugyanakkor csak részben követi Goethe világirodalmi klasszikusát, a cselekmény egyes fordulatai a Faust-legenda német népköltészeti hagyományából származnak. Hevesy Iván (1893–1966), a legendás filmesztéta és nem mellesleg Wagner operáinak szakértője, a Nyugat filmrovatának állandó szerzője úgy látta, a film alkotói „helyes érzékkel ismerték fel, hogy az eredeti, irodalmi szöveghez és koncepcióihoz való ragaszkodás csak ártalmára lehet a filmnek. Más a színpad, az irodalom, és más a film. Goethe Faustját a maga egészében filmre erőltetni szerencsétlen vállalkozás, elhibázott kísérlet lenne. Ez a kísérlet két lehetőségre vezetne: vagy megkapnánk a külső mesét a dráma belső tartalmának értelme nélkül, vagy pedig – ami talán még rosszabb lenne – a filozofikus tartalmat olvasnánk el a felírások kivonatolásában, és a film ezeket a passzusokat csak illusztrálná.” (1926. október 16.) Mohácsi Jenő ugyanakkor éles hangon kifogásolta, hogy a film alkotói Goethe nevét is feltüntették a „stáblistán”. Szerinte „a Faust-témát kétféleképpen lehetett volna megfilmesíteni: vagy a régi monda alapján, vagy pedig Goethe nyomán. A forgatókönyvíró Hans Kyser filmszcenáriuma, mely egyébként írói munka, e két Faust-forrás vizeit összezavarta. Murnau, a film tehetséges rendezője, ebben a zavarosban kénye-kedve szerint halászott, ehhez joga is lehetett, hiszen ezért filmrendező, művészete szuverén, sőt diktátori. Azonban Goethe neve alatt hirdetni ezt a filmet: félistenkáromlás.” (Századunk, 1926)

A film eredeti zenéjét a maga idejében igen népszerű Werner Richard Heymann és a budapesti születésű Rapée (Rappaport) Ernő (1891–1945) szerezte, de a későbbiekben számos további változat született a monumentális alkotáshoz. Hogy az 1926-os magyarországi vetítések alkalmával milyen zenei aláfestés hangzott el, arról a korabeli beszámolókból kevés derül ki. Hevesy Iván mindenesetre csalódottan jegyezte meg, hogy

For the English version see page 5.

a „film előtt és közben áriák hangoztak el Gounod Faustjából és szavalatok Goethéből. Méghozzá színházi szcenírozással. Sikerült ezekkel a film hangulati egységét megzavarni, és egyveleget teremteni az irodalmi, színpadi, operai, mondai és filmhatásokból. Hát ezért fáradozott Kyser és Murnau a hatásegység megteremtésével, hogy most oda nem illő ráadásokkal felforgassák azt?” Hevesy nem tudhatta, de maga Murnau kérte arra Rapée Ernőt, hogy a németországi premiervetítésekhez összeállított zenében dolgozzon fel részleteket Gounod operájából. Ennyiben tehát a budapesti kísérőzene nem is állt annyira távol a rendező eredeti szándékától. Fassang László orgonaváltozatában ugyancsak felbukkannak idézetek, de nem Gounod Faustjából, hanem Liszt háromtételes programszimfóniájából. A régi némafilmek zenei újragondolásáról így vélekedik Fassang: „A zenei stílusok tekintetében három fő választási lehetőségem van. Az első: visszamegyek abba a korba, amelyikben a film játszódik. A második: azt a kort választom, amelyben a film keletkezett – kiválasztok egy zeneszerzőt az 1920-as évekből, és elképzelem, vajon mit tudott volna kezdeni ezzel a feladattal. A harmadik lehetőség pedig az, hogy a mából indulok ki, és a mai filmzenei eszköztárat használom, úgy, hogy közben Liszt Faustszimfóniájának egyes motívumait is felidézem. Azt remélem, sikerül ezt a három réteget egységes egésszé komponálnom. Az egyik legizgalmasabb kihívás számomra, hogy a zene olyan egésszé váljon, amely akkor is működne, ha valaki a film megnézése nélkül hallgatná végig. Ugyancsak kihívás úgy játszani, hogy azoknak, akik eljönnek a Müpába, elsősorban a filmről legyen élményük, ne a zenéről. A film a főszereplő, a zene pedig azt szolgálja, hogy a befogadása teljes művészeti élménnyé álljon össze. Maga a film a partitúra. A vásznon történteket nem befolyásolja a zene, mégis el lehet érni azt a hatást, mintha a zene indítana el bizonyos folyamatokat. A kamarazenéhez tudnám ezt hasonlítani, azzal a különbséggel, hogy ebben a viszonyban az egyik fél teljesen változatlan. Vannak olyan helyzetek, amelyeknél nagyon precíznek kell lennem, akár tizedmásodpercnyi pontossággal kell lekövetnem vagy megelőlegeznem egy-egy jelenetet. Más részeknél nagyobb szabadságom van abban, hogy közel kerüljek a jelenethez, az egyik szereplőhöz, majd eltávolodjam tőle. Mintha objektívet használnék, rázoomolhatok egy részletre, aztán újra a nagy egészet láttathatom. Ezeknek a játékára épül a partitúra.” Közel száz évvel a Faust elkészülte után Martin Ferenc (Filmvilág, 2020) így értékelt: „A Faustban az identitáscsere és a látszatteremtés motívumát nagyszabású létdrámába ágyazza Murnau. A témából adódóan jó néhány jelenetben újra hangsúlyos szerepet kap a természet, de a korabeli kritikusok azért fanyalogtak, mert túlzottan kulisszaszerűre, mesterkéltre

sikerült a miliő- és tájábrázolás. Ezt a természetellenes hatást nem pusztán a stúdiófelvételek és a trükkök alkalmazása vagy a pénzügyi kényszer diktálta. A Faust nem csupán az akkori német filmgyártás technikai bravúrjainak látványos felvonultatása. A természet és a tér szervetlen életidegensége kifejezi az ördög által megszállt világ antihumánus karakterét, a főhős kiábrándulását az érzéki örömökből, amit a Mephistóval kötött szerződése után élvezett, valamint melankóliáját tartalmatlan élete miatt a látszólagos szabadság állapotában. A miliő expresszionista stilizáltsága, helyenként absztrakt formája az irracionális fenyegetettségen túl azt is érzékelteti, hogy egy látszatvilág tereit láthatjuk, amit Mephisto démoni akarata kreált. Sorozatos illúziókeltéseivel csalja csapdába Faustot, így akarja megkaparintani a lelkét. Ennek az ördögi célnak a megvalósításához a legfontosabb eszköz a fénnyel és árnyékkal történő manipuláció. A Faustot megtévesztő illúziók mind valamilyen fényforrásból erednek. Mephisto szemfényvesztő akcióival, varázslataival épp úgy ejti rabul áldozatát, mint a film lélegzetelállító képeivel a nézőt.”

FASSANG László

Fassang László generációjának egyik legsokoldalúbb orgonaművésze. Kivételes adottságokkal rendelkező improvizáló művészként zenei világában egyaránt fontos szerepet játszanak a klasszikus és a kortárs kísérletező műfajok. A klasszikus orgona mellett zongorán, Hammond orgonán és különböző elektronikus hangszereken is rendszeresen koncertezik. Diplomáit a Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetemen és a párizsi Conservatoire-on szerezte. Versenygyőzelmei közül kiemelkedik a Calgary Nemzetközi Orgonaverseny Improvizációs Nagydíja (2002), valamint a Grand Prix de Chartres első díja és közönségdíja (2004). 2004 és 2008 között a San Sebastián-i Musikene improvizációtanára, majd 2008 és 2024 között a Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti egyetem orgonatanára volt. Jelenleg a Müpa rezidens orgonistája és a párizsi Conservatoire improvizációtanára. 2022 óta Kepes Julival közösen vezeti a Zenélj szabadon mozgalmat, melynek keretében improvizációworkshopokat és előadásokat tart. Tevékenységét 2006-ban Liszt- és Prima díjjal, 2013-ban Gramofon-díjjal ismerték el. 2016-ban Magyarország Érdemes Művésze kitüntetésben részesült.

FASSANG LÁSZLÓ

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau: Faust – a silent film with organ accompaniment Premiered 99 years ago, in 1926, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s silent film was one of the most expensive productions of its time and featured a wealth of novel technical solutions. ‘The Faust film is magical,’ wrote the reviewer of Színházi Élet after the Budapest premiere. ‘Goethe got to know the myth of Faust while at a puppet theatre. There is a long way from the primitive tale of the puppet show to Goethe’s tragedy, but the journey does not end there. The sequel is: the Faust film.’ The plot only partly follows Goethe’s classic, with some of the turns borrowed from the German folk tradition of the legend of Faust. Iván Hevesy (1893–1966), a legendary film critic and regular contributor to the cinema column of Nyugat, as well as an expert on Wagner’s operas, was of the opinion that the makers ‘rightly intuited that insisting on the original, literary text and concept would only be detrimental to the film. Stage, literature and film are all different. It would be a mistake, a disastrous enterprise, to force the entirety of Goethe’s Faust on celluloid. Such an attempt could lead to one of two results: we would either get the external tale without the meaning of the internal content of the drama, or – and this would be even worse – we would be reading the philosophical meaning in the abstract of the subtitles, and the film would merely illustrate these passages’ (16 October 1926). By contrast, Jenő Mohácsi was sharply critical of the fact that Goethe’s name appeared in the credits. He thought ‘the subject of Faust could have been adapted for the screen in either of two ways: either on the basis of the old legend or on the basis of Goethe. The script of Hans Kyser, which is incidentally a work of literature, mixed and muddled the waters of these two sources of Faust. Murnau, the talented director of the film, fished in these troubled waters as he pleased – and he had a right to do so because he is a director, his art is autonomous, even dictatorial. But to advertise this film under the name of Goethe: that is semi-blasphemy’ (Századunk, 1926).

The original music of this monumental piece of cinema was written by Werner Richard Heymann, a very popular composer of his age and Ernő Rapée (Rappaport, 1891–1945), who was born in Budapest. It was followed by many other versions over time. The reviews of the 1926 screenings in Hungary reveal little about the musical accompaniment. Iván Hevesy, on his own part, was disappointed to hear ‘arias from Gounod’s Faust and recitals of Goethe before and during the film. With theatrical staging, to boot. They successfully disrupted the atmospheric unity of the film and created a melange of literary, theatrical, operatic, legendary and cinematic effects. Did Kyser and Murnau go to the trouble of creating a unity of effects so that now it can be thrown into confusion with out-of-place additions?’ Hevesy could not know that Murnau

himself had asked Ernő Rapée to include excerpts from Gounod’s opera in the music for the German premiere screenings, and thus the music in Budapest was not that far from the director’s original intention. László Fassang’s organ score also includes quotations, but instead of Gounod’s opera, from Liszt’s three-movement programmatic symphony. When it comes to reimagining the music of old silent films, Fassang is of the opinion that ‘I have essentially three options with regard to musical styles. The first is to go back to the period in which the film is set. The second is to choose the time when the film was made – select a composer from the 1920s, and try and imagine what he would have done with the task. Film music is less likely to be my preference on such occasions; I am more interested in classical composers we still know. The third option is to start from the here and now and use the apparatus of today’s film music, while also employing certain motifs from Liszt’s Faust Symphony. I hope to fuse these three layers into a unified whole. One of the most exciting challenges is to make the music into a whole that would work even if you listened to it without watching the film. It’s also a challenge to play in such a way that the primary experience of those who come to Müpa Budapest is about the film and not the music. The star is the film, and the music serves to make its reception a complete artistic experience. The film itself is the score. What happens on the screen is unaffected by the music but you can still make the impression that the music sets off certain processes. It’s a bit like chamber music, with the difference that in this relationship, one of the partners remains unchanged. There are situations where I have to be very precise and have to follow or anticipate a scene with tenth-of-a-second precision. Elsewhere, I have more freedom to get close to the scene or a character and then to increase the distance. I can zoom in on a detail, as if using a lens, and then show the picture again. The score is based on the play of these.’

Almost a hundred years after the film was made, Ferenc Martin (Filmvilág, 2020) wrote: ‘In Faust, Murnau embeds the motif of identity change and the creation of appearances in a large-scale existential drama. Owing to the subject, nature is again given a prominent role in a number of scenes, but contemporary critics found the representation of the milieu and the landscapes too stagy and artificial. This artificial feel did not simply follow from the use of studio shots and special effects or financial constraints. Faust is not just a spectacular display of the technical feats of German film-making at the time. The inorganic alienness of the land and the spaces expresses the anti-human character of a world possessed by the devil, the hero’s disillusionment with the sensual pleasures he enjoyed after he had entered into a contract with Mephisto, as well as his melancholy over what is a meaningless life despite a state of apparent freedom. The expressionist stylization of the milieu, its sometimes

abstract form, suggests – in addition to an irrational sense of being threatened – that we see the spaces of an illusory world that has been created by Mephisto’s demonic will. He keeps creating illusions to trap Faust and get hold of his soul. The foremost means in service of this diabolical intention is manipulation by means of light and shadow. The illusions that deceive Faust all come from some source of light. Mephisto captivates his victim with dazzling acts and tricks, just as the film captivates the viewer with breathtaking images.’

László FASSANG

One of the most versatile organists of his generation, László Fassang is an improviser with exceptional abilities. Classical and contemporary experimental works play equally important roles in his world of music. In addition to the classical organ, he also regularly performs on piano, Hammond organ and various electronic instruments. He is a graduate of the Liszt Academy and the Paris Conservatoire. His notable competition wins include the Grand Prix for Improvisation of the Calgary International Organ Competition (2002), as well as the First Prize and Audience Award of the Grand Prix de Chartres (2004). Between 2004 and 2008, he taught improvisation at the Musikene (San Sebastián), and from 2008 to 2024, organ at the Liszt Academy. He is currently organist-in-residence at Müpa Budapest and professor of improvisation at the Paris Conservatoire. Since 2022, he has been co-leading the Make Music Freely movement with Juli Kepes, as a part of which he holds workshops and lectures. His work was acknowledged with the Liszt Prize and the Prima Prize in 2006, the Gramophone Award in 2013, and the Artist of Merit award in 2016.

A Liszt Ünnep Nemzetközi Kulturális Fesztivál ingyenes kiadványa

Kiadja: Müpa Budapest Nonprofit Kft. Felelős kiadó: Káel Csaba vezérigazgató Nyomdai kivitelezés: Pátria Nyomda Zrt.

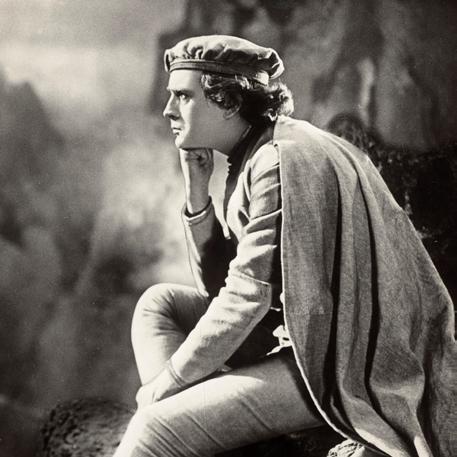

Címlapfotó: Gösta Ekman Faust szerepében, 1926

Szerkesztő: Molnár Szabolcs

A szervezők a szereplő- és műsorváltoztatás jogát fenntartják.

E-mail: info@lisztunnep.hu

Telefon: +36 1 555 3000

lisztunnep.hu