25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DOCTORAL SCHOOL

25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DOCTORAL SCHOOL

HEDVIG HARMATI HEAD OF THE DOCTORAL SCHOOL

MOHOLY-NAGY

UNIVERSITY

Gutta cavat lapidem, “a drop hollows out a stone”. The Latin proverb vividly exemplifies that persistence will eventually win the day, whether we are talking about carving a marble statue with great artistic care, the life-saving invention of an antidote to epidemic disease, or even the founding and ongoing restructuring of a school. Without benevolent faith—and here I don’t necessarily mean in a religious sense—there is no way to create something that is worthy of existence and serves the noble goals and basic mental and spiritual needs of our smaller and larger communities. The Doctoral School of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design also began its life as a raindrop, and in the past quarter of a century it has developed in a way that we can be justly proud of, and this gives us confidence in the future as well.

The need to establish a doctoral school at the legal predecessor of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, the Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts, was first formulated in 1983 in the Modernization Program

of the highly progressive era led by rector István Gergely. The realisation of this program is one of the greatest achievements of the Hungarian design movement. The “rocket” —as the program became known, based on László Zsótér’s infographic—already envisioned a three-cycle training plan more than a decade and a half before the start of the Bologna process.

In the end, however, the Doctoral School could only launch after the regime change in Hungary in 1990, under the leadership of Imre Schrammel, at which time—and partly due to the cataclysmic collapse of Hungarian industry—an arts and crafts course that operated in the spirit of traditional craftsmanship, compared to the original design-based model, was accredited. This actually served the higher-level, masterful deepening of knowledge and various specialist skills, and had corresponding theoretical aims. This is also true for the Applied Art Theory program led by the Head of the University Doctoral Council, Gyula Ernyey, where the methodological considerations helping arts and crafts

(cf. with the idea of “tools for better design”) and the art history of design approach were decisive. The Doctoral School was renowned at that time because the world-famous Ernő Rubik was an active professor here, along with his fellow founding members, Zoltán Bohus, Judit Droppa, Gyula Ernyey, István Ferencz, István Janáky jr., Tamás Nagy, Vladimír Péter, Csaba Polgár, József Scherer, Károly Simon, and Gábor Turányi.

During Judit Droppa’s rectorship, Péter Reimholz was already the leader of the Doctoral School and tried to take careful steps to bring the training back to the path of the Gergely era. He invited László Zsótér back to the university to lead the Visual Communication and later the Media Arts DLA subprogram. At that time, not only applied arts, but media arts as well as architecture DLA training took place in the Doctoral School. Especially in the latter program, and thanks to masters of such calibre as Reimholz himself, István Janáky jr., István Ferencz, Gábor Turányi, Tamás Nagy, and Péter Mátrai, an extremely intimate and high-level living professional community was forged during those years.

During the time of István Ferencz, who succeeded Reimholz, this system continued to function, but at the same time, several attempts were made to start a PhD program. In 2013, in the publication SHARE Handbook for Artistic Research Education of the European League of Institutes of the Arts (ELIA), one of the case studies presenting good practices was dedicated to the Doctoral School of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design—this was a serious recognition for a doctoral school, which had only been operating for more than a decade at the time!

József Tillmann, the former secretary of the Doctoral School, who first became the head of the Institute for Theoretical Studies and then of the Doctoral School, was a liberal humanist and involved his younger colleagues in the setting up of the school first involving the new secretary of the Doctoral School, Bálint Veres, and then Márton Szentpéteri more intensively in this work. The latter, who was joint head of the departments of product designers, fashion and

textile, and silicate designers, had previously participated in the unsuccessful accreditation process of the PhD program in 2009 to replace Ernyey’s Applied Art Theory DLA program with Ágnes and Gábor Kapitány, and András Ferkai and Tillmann. In 2011, Szentpéteri became a member of the Doctoral and Habilitation Council at the Doctoral School, and at the request of Rector Gábor Kopek, led the finally successful theoretical PhD accreditation, which fundamentally defined the reform of the Doctoral School in 2016 within the framework of design culture studies. From December 2014, he was the head of the program that started the following year. The 2016 reform, which, following the newly launched PhD program, registered Bálint Veres as senior advisor to the rector and acting head of the DLA programs, built the multidisciplinary Doctoral School of the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design from the three existing DLA programs and single PhD program within the framework of the newly introduced doctoral training system. The basic principles set out in the

university’s Institutional Development Plan (IFT) and the contemporary Integrated Institutional Development Program (IIP) have probably been followed most faithfully by the Doctoral School ever since, as its work is still based on the same three pillars, which guarantee that higher education in art and design should be implemented in terms of liberal education and learning instead of pure vocational training, as universities of sciences and arts do in the fields of humanities, social sciences, technical engineering and natural sciences. These three pillars embody the areas of interest of “artistic research”, “design research” and “design culture studies”, which are in constant dialogue with each other. This book intends to shed light on these research attitudes with illustrations taken from graduation works and a list of the names of people involved in our story either as student or faculty.

I took over the management of the Doctoral School from József Tillmann in 2020. For the first time, I became the head of the Doctoral School as a domi doctus university

person who obtained both her diplomas and her doctorate at the Moholy-Nagy University of Arts and Design and its legal predecessor. From the very beginning, it has been my definite goal that the Doctoral School, which actively involves all the university’s academic actors, should be transformed into a truly living community of supervisors, instructors, researchers, consultants, and students. A community that strengthens academic identity of its members both at an individual and community level, especially in the light of the common cause of the supply of researchers and teachers. My goal is also to integrate the Doctoral School into the university as a whole and in both domestic and international professional life, continue the modest but productive work that my program leaders and predecessors have already begun with the aim of making the Doctoral School a real living leaven of domestic third-cycle design and art courses in-house and outside, in the next quarter of a century.

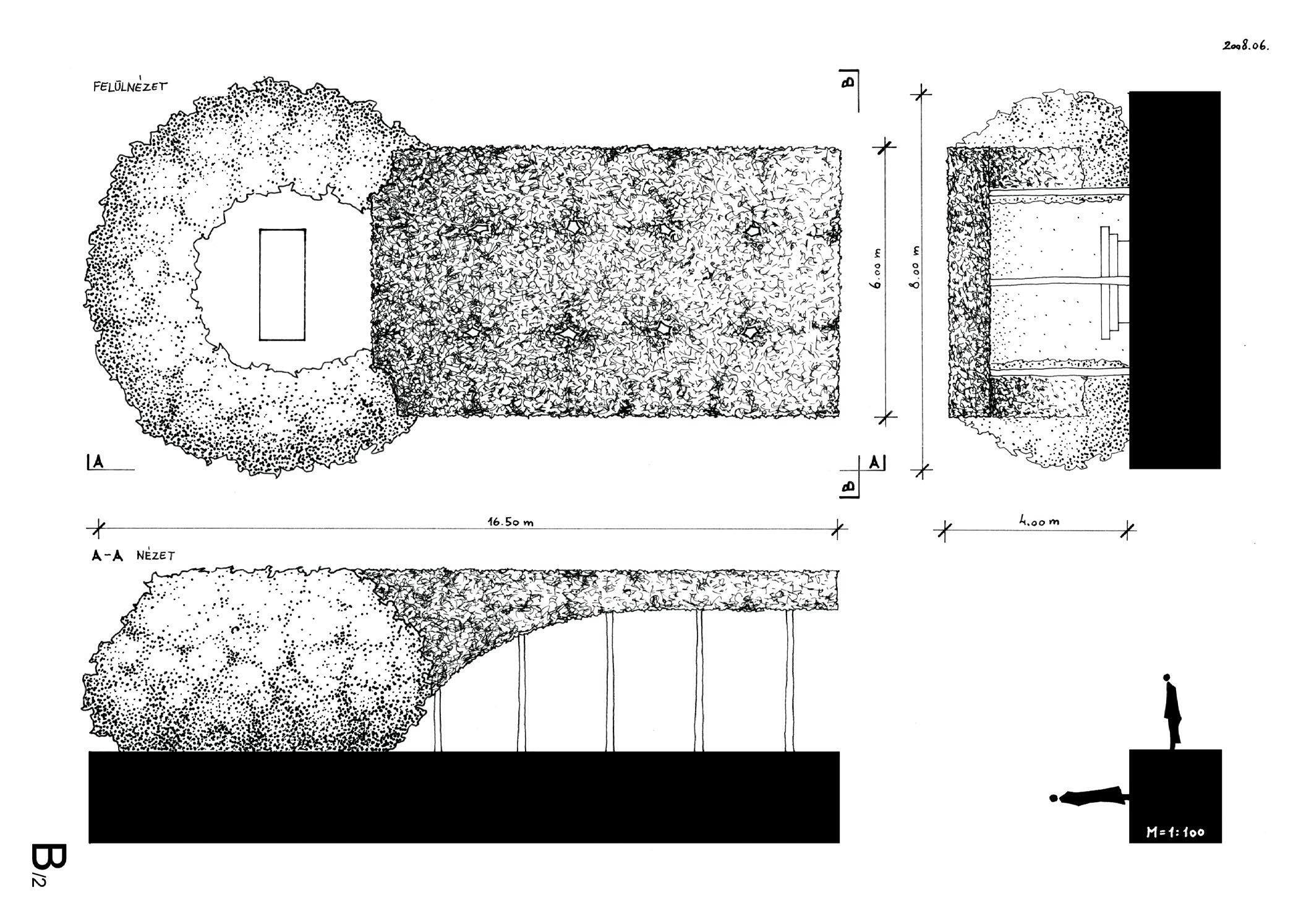

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK WINE TERRACE AND SPA, EGER, ALMAGYAR

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION METAMORPHOSIS — SEDIMENTATION AND ORIGINALITY SUPERVISORS ANDRÁS GÖDE, TAMÁS TOMAY PHOTO DÁVID LUKÁCS

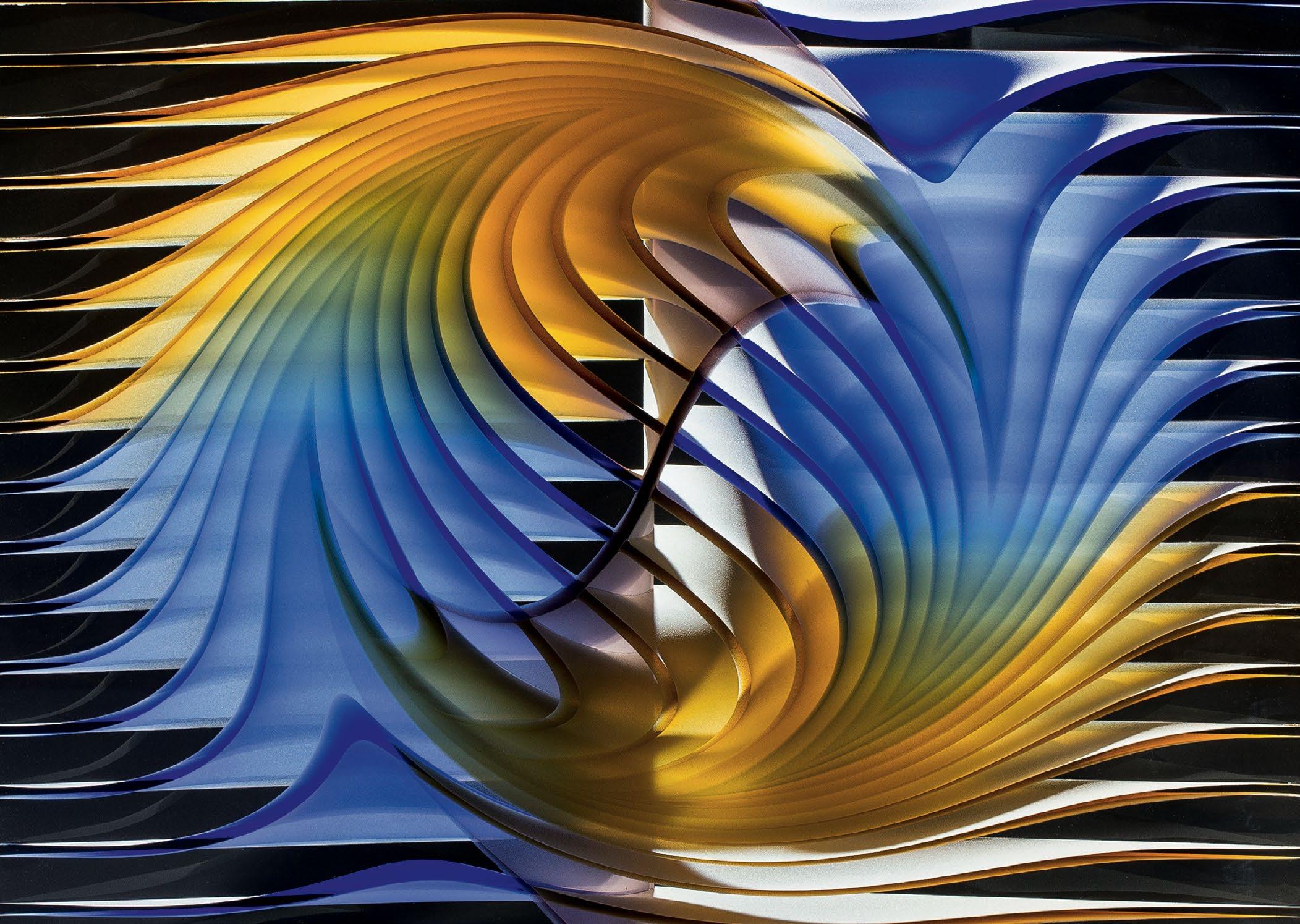

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK GENESIS SERIES

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION CREATIVE FORCES IN NATURE

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK

PHILEMON’S DREAM

THE IDEA OF ETERNAL MARRIAGE

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

PHILEMON’S DREAM —

THE IDEA OF ETERNAL MARRIAGE

SUPERVISOR

GÁBOR KOPEK

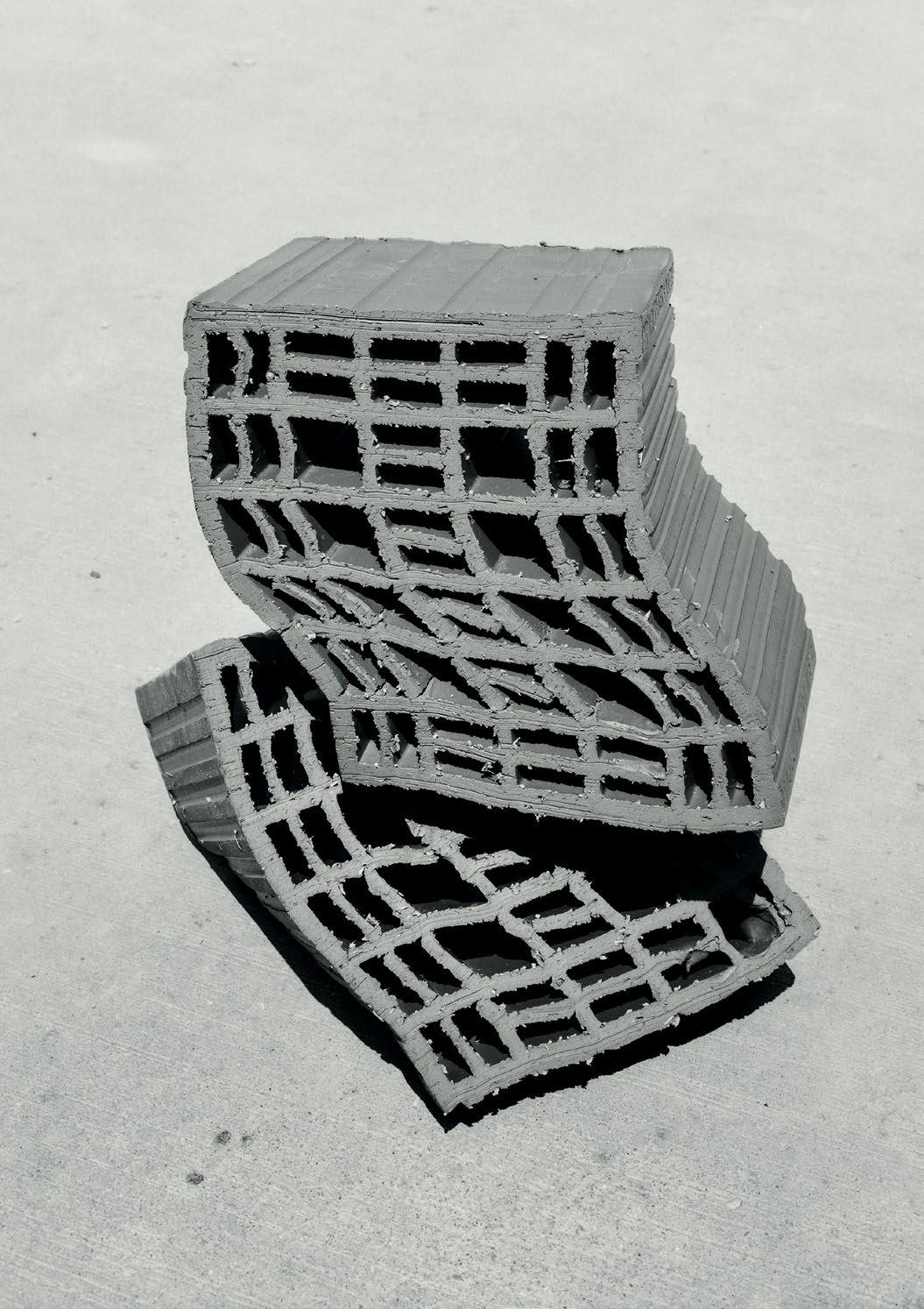

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK

XXVII HUMAN

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

HUMAN. HUMAN SCALE — FROM BRICK TO THE HORIZON OF THE TECHNOLOGICAL ERA

SUPERVISORS

ÁGNES KAPITÁNY

GÁBOR KOPEK

GÁBOR ARION KUDÁSZ DLA IN MULTIMEDIA

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK COLOR-FRONT FILM POST-PRODUCTION STUDIO, BUDAPEST

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION CITY WITHIN THE HOUSE — THE HISTORICAL CITY STRUCTURE AS A MODEL FOR CONTEMPORARY SPACE-FORMING

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK TABLE OF THE FUTURE

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION THE TASTE OF MEMORY SUPERVISORS

JONATHAN VENTURA SHENKAR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND DESIGN

The gesture of searching, in which one does not know in advance what one is looking for, this testing gesture known as “scientific method,” is the paradigm of all our gestures. It now holds the dominant position that religious ritual gesture did in the Middle Ages [...] At present, every gesture, including every ritual one, is shaped by the structure of scientific research

—Vilem Flusser, Gestures

The reason thinking is serious is that it is a social act, and that one is therefore responsible for it as for any other social act. Perhaps even more so, for, in the long run, it is the most consequential of social acts

—Geertz, Available Light

Prior to designing a product that would influence the lives of millions, the designer needs to conduct in-depth research, understand the socio-cultural context of the various design partners and outline the possible pitfalls and lacunas along the way. This is fairly obvious and agreed upon by all. Or is it? While we all think we know what design research is, we don’t necessarily agree on its applicability, necessity, or its place in the design process. While a broad survey through the evolution of design research surpasses the scope of this essay, I wish to present several thinking points relating to the history of the concept, its contemporary use, and a few reflections towards its future. The two epigraphs are markers of the evolution design theory and indeed design research have undergone. More so in the case of Flusser, but Geertz as well, symbolizes the worldview and attitude of a good design researcher—broad-minded, trans-disciplinary (if not in education, then in practice), humanistic, curious, articulated and open to new ideas.

Before we highlight this broad issue, let us try to define the concept of design research. In one of his ventures into communication theory, Vilem Flusser (2001, 93) describes three types of messages “that humans emit and receive towards and from each other: (a) messages of knowledge, (b) messages of desires, and (c) messages of sensations and feelings.” While seemingly unrelated to design, Flusser continues and describes these three types of messages as being (a) epistemological,

(b) ethical and (c) aesthetic. In other words, they represent science (a), politics (b) and art (c). As we have seen throughout design history, specifically with cutting-edge thinkers, such as Tomas Maldonado of the Ulm School in the 1960s, design is or should be a meeting point of art, science and a political standpoint. Interestingly, these three types of message also correlate with Aristotle’s (2010) classic depiction of rhetoric, shifting between ethos (credibility of the speaker), pathos (the emotional state of the audience) and logos (proving or seemingly proving what is true). Indeed, when a design researcher stands before a client or their colleagues, presenting a thesis, conclusions or a call for action, they need to be first and foremost excellent persuaders. They need to persuade their listeners that they possess previous knowledge (theory/history), that they were in fact in the field, talking to various design partners, and that their reasoning is sound. Much as Flusser describes it, design research is indeed a combination of science, politics and art. Moreover, much like anthropologists who have had a big impact on this discipline, design researchers do not always present an image or conclusions that the client wants to hear, but they still need to make their claim. In some venues of design research—for example, social design—the political aspect of design research becomes crucial. So, does the softer scientific aspect of conducting a collaborative foray with and for the various design partners and relevant communities. The responsibility of conducting valid research, then, is even more important in design research than other fields of academic research since its outcome influences thousands or in some cases millions.

Let us go back to the beginning. While it is fairly difficult to define what design research is (versus its epistemological roots or practical methodologies), Cross (2006, 100) offers a fairly simple, yet precise, definition, claiming that “our concern in design research has to be the development, articulation and communication of design knowledge. Where do we look for this knowledge?

I believe that it has three sources: people, processes and products.” Indeed, Margolin and Margolin (2002) offer another approach to the classic “market approach” viewing design as a practical mediator between entrepreneurs and the market. Their definition of the differences between the two models is important to our discussion as well:

The primary purpose of design for the market is creating products for sale. Conversely, the foremost intent of social design is the satisfaction of human needs. However, we don’t propose the “market model” and the “social model” as binary opposites, but instead view them as two poles of a continuum. The difference is defined by the priorities of the commission rather than by a method of production or distribution. Many products designed for the market also meet a social need, but we argue that the market does not, and probably cannot, take care of all social needs, as some relate to populations who do not constitute a class of consumers in the market sense. We refer here to people with low incomes or special needs due to age, health, or disability. (ibid, 25)

Therefore, a key difference lies in the need to cater for people situated outside the “consumption sphere”, thus imbuing design research with values such as empathy and care. Their approach rests on participatory research following key stages: engagement, assessment, planning, implementation, evaluation, and termination. These two approaches are interesting, since they bridge other lacunas, to focus not on history, theory or practice, but rather on points of importance and values. Thus, to focus on people means we deal with the essence of “how people design”. Upon adding “processes” to the equation, we present another layer of “tactics and strategies of designing”, i.e., delving into the various techniques designers use to design. Finally, when researching products, we investigate manufacturing technologies, consumption, materials, techniques of use (alluding to Marcel Mauss’ famous theory he calls “techniques of the body”), aesthetics, semiotics and more. To summarise simply: this means addressing end-users, the designer, and the designed product.

Since the key person conducting design research is the designer, let us focus on them first. Following this train of thought on design research, Frayling (1993) offers three possibilities: research into design, research through design, and research for design. Cross (2006: 9) highlights the unique knowledge of the first, since “designers have the ability both to ‘read’ and ‘write’ in this culture: they understand what messages objects communicate, and they can create new objects which embody new messages.” To these three, Jonas (2024, 32) offers a fourth option he terms “research as design”. While this seemingly

simplistic approach was accurate at the time of publication, it needs some development, as we shall see. All in all, we can safely claim that design research rests on previous data, with the addition of newly acquired and interpreted knowledge through the use of consistent, coherent and accepted methods.

Following this logic, Bayazit (2004, 16) outlines five attributes of design research:

• Design research is concerned with how design products perform their jobs, and how they work;

• Design research is concerned with how designers work, how they think, and how they carry out design activities;

• Design research is concerned with what is achieved at the end of a purposeful design activity, how an artificial thing appears, and what it means;

• Design research is concerned with the embodiment of configurations;

• Design research is a systematic search and acquisition of knowledge related to design and design activity.

In other words, “[t]he objectives of design research are the study, research, and investigation of the artificial made by human beings, and the way these activities have been directed either in academic studies or manufacturing organisations” (Bayazit 2004, 16). These attributes echo the

classic theory of Herbert Simon focusing on the “sciences of the artificial” (2019 [1968]). According to Simon, design in general and design research specifically, found itself in an organisational problem, as well as a philosophical and methodological one. As a discipline, design had to reframe itself vis-a-vis colleges, universities, and more generally, the sciences or epistemological sphere of “scientific knowledge”. This complexity is further highlighted by the very broad scope of design, ranging from a creative artistic side to a practice-based and rational side. In other words, design found itself between art and practice (or applied knowledge, in some countries). As several attempts to bridge this gap were made during the twentieth century—the Bauhaus and De Stijl, naturally, but more importantly the Ulm School of Design (HfG)—contrary to other disciplines, wherein research is inherently embedded, in the case of design, other options needed to be highlighted.

The complexity of the journey design research has undergone, can be seen through two well-respected definitions. Jonas (2023, 24) refers to the discipline as a “trans-domain of knowing”, which aims at shaping complex social problem areas and emerges from a convergence of design and science.” This seemingly simple definition alludes to three key attributes of design research— it deals (in some cases) with wicked problems of design, it brings together various bodies of knowledge and methodologies, and it is scientific in essence. To this we can add Cross’s famous definition, which describes the unique stance of design research as a “designerly way of knowing”. Indeed, thinking as a designer is a unique and important trait, yet when it comes to broader knowledge,

“what designers know about their own problem-solving processes remains largely tacit knowledge—i.e. they know it in the same way that a skilled person ‘knows’ how to perform that skill” (Cross 2006, 9). Conversely, design research is exactly the tool to bridge this crucial gap.

As in every other aspect of human history, there is a lot we do not know. For example, what did a Roman design brief look like? Did a Spartan or Athenian craftsman conduct user-centred research or market research? We can surmise, based on other designed products, that because Roman craftsmen offered “catalogues” for various “mass-produced” objects, and they had branding and marketing, they probably conducted some type of research (see Ventura and Ventura 2017). Interestingly, the Roman Era, with its elaborate lifestyle, consumer culture, marketing, and shipping processes, is the closest pre-modern period to our own we can identify. However, we can presume that actual design research evolved from mass-produced products in a competitive market—hence, from the Industrial Revolution onwards. Thus, we can say that design research is about products that are relevant to a large group of people, in a competitive market, and is based in a socio-cultural context (following the classic “marketmodel”, proposed by Margolin).

Indeed, in one of the key books on user research, Designing for People, Henry Dreyfuss (1955, 18–9) describes the shift from pre-modern to contemporary design:

Some manufacturers were reluctant to accept this point of view. They considered the industrial designer merely a decorator, to be called in when the product was finished. They asked, “can you fix this up and make it look pretty?” Indeed, for a time in this chaotic period a person who knew how to enamel something black and put three chromium strips around the bottom was considered an industrial design. In time manufacturers learned that good industrial design is a silent salesman, an unwritten advertisement, an unspoken radio or television commercial, contributing not merely increased efficiency and a more pleasing appearance to their products but also assurance and confidence.

Dreyfuss’ description is highly important on two accounts—first, from this description of his contemporary historical standpoint, we understand that design research did not previously exist. Second, as a harbinger of inclusive design and people-centred design research, Dreyfuss understood that the designer’s role is primarily to understand the people who would use the designed product at the end of the process. In addition, he understood the potential friction between these needs and those of the manufacturer/client, as well as key competitors and the relevant market in general.

Naturally, when trying to understand what people— potential consumers of each design outcome—think about this product, its usability and the ways it influences their life, designers needed access to this knowledge. Thus, a crucial part of design research became embedded in its methodologies and the technologies used both in design research and practice. For that matter, by the 1990s a crossroads of two paths symbolised a shift in the present, as well as implications for the future. While IDEO presented a business or practice-oriented approach, Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design (HHCD), as part of the London-based Royal College of Arts, presented a people-oriented approach. Thus, while the former rested on B-School methodologies, the latter focused on Social Sciences in general and on design anthropology in particular (see Clarke 2011; Gunn, Otto, and Smith 2013).

While the definition of “science” and scientific research surpasses the scope of this essay, the essence of scientific research trickled into design from WWII onwards. During the 1980s and 1990s, design departments throughout the world bolstered their curriculum to become closer in their approach to social science departments and business schools (see Gal and Ventura 2023). Interestingly, following the ground-breaking work of Dreyfuss, Scandinavian design schools highlighted the end-user part of design research as early as the 1960s. However, in many ways, it was IDEO’s (2015) 1 focus on user research that added a significant portion of design research that focused on these empirical methodologies. While at the beginning of this process, they tended to focus on classic ethnographic methods, research

See also IDEO’s research methods platform: https:// www.designkit.org/ methods.html.

methodologies in the last three decades evolved to encompass innovative methodologies, some of which were exported from design practice, and mixed methods research, while others developed through deeplyrooted qualitative or quantitative research philosophies (see Beyer and Holtzblatt 1998; Blomberg et al. 1993; Julier 2006; Lu Liu 2010).

As the DRS (Design Research Society) was founded in London in 1966 and is still one of the most influential agents in the discipline, dedicated journals influenced researchers and the very definition of design research as well. Dixon (2023, 19) describes two key approaches that have driven design research since the 1980s. First, a focus on “a rigorous analysis of designers’ actions and interactions”, primarily in the ways designers seek solutions and frame problems, leading to what is called now design studies. The second path combines design research and practice, or “research into design”, as previously mentioned. To these two, we might add design theory and design for social change, as we shall see shortly.

In the last decade, design research has become integrated into most design schools, as an inherent part of the curriculum. As such, research methodologies are taught throughout the various courses, and should include design theory as well. Furthermore, an important addition to this discipline, apart from the spread of ecological approaches and sustainability practices in design, is the human factor. Starting with designing for “design partners”, rather than “customers” or “end-users”, design research is more inclusive, less Euro-centric and more sensitive to excluded and marginalized communities.

For example, researchers “re-discovered” the influential India Report, written by Charles and Ray Eames after their visit to the National Institute of Design in April 1958. 2 In this important report, the need for function, socio-cultural context and learning for local communities is highlighted, as well as professional research. Janning (2023, 5) describes this shift as follows:

Socially-informed research in design is the ethical and intentional incorporation of human-centred data gathering and analysis throughout the design process. It is the iterative and systematic practice of gathering, analysing, and sharing input from people who occupy and engage with the built environments that architects and interior designers create as the designs are created and built.

Other key additions were the frames of “care” and ‘empathy’, as well as the integration of people-centred approaches such as inclusive design, participatory design, design activism and more (see Ventura and Bichard 2017). Naturally, there’s a lot more ground to cover, for while academia is advancing, research in and for the industry has still to make this jump, either due to added cost or a shift in mentality.

If we ask what has changed in the last thirty years, the answer might be disappointing. More than twenty years ago Buchanan (2001, 7) argued that:

Some see no need for design research, and some see in the problems of design the need for research that is

2 http://echo.iat. sfu.ca/library/ eames_58_india_ report.pdf

modelled on the natural sciences or the behavioural and social sciences as we have known them in the past and perhaps as they are adjusting to the present. But others see in the problems of design the need for new kinds of research for which there may not be entirely useful models in the past—the possibility of a new kind of knowledge, design knowledge, for which we have no immediate precedents. We face an ongoing debate within our own community about the role of tradition and innovation in design thinking.

In a way, as educators and practitioners, we still argue about the definition of design research, as well as its purpose and implementation. Indeed, research in the world of design practice has had a problematic start.

As Muratovski (2016, 58) puts it: “design practice is not the same as doing design research, but that the study of design practice can be considered as design research. Even so, I have to add that studying design practice alone is a limited way of looking at design research”. Cross (2016, 102) correctly summarizes the traits of good research in general, including being purposive (based on an issue or problem worthy of investigation), inquisitive (seeks to acquire new knowledge), informed (relates to and built upon previous research), methodical (planned and carried out in a disciplined and planned manner) and communicable (presenting results that are understandable and testable by others).

And yet, changes were introduced into design research. Encompassing human, as well as non-human design

partners; introducing care, compassion and empathy as key values in research; embedding design ethics and bridging theory and practice; developing vernacular knowledge and working with and for local communities. These changes have been triggered. Indeed, this key shift could be seen in recent major publications, as well as in dedicated networks, workshops, and conferences. Rodgers and Yee (2023, 4) correctly portray the future of design research in the second edition of their influential book:

Looking to the future, we hope that this book will help design research to continue to play a leading role in the social, cultural, economic, and environmental health and wellbeing of nations across the world [...] Design is an inherent part of human activity and creativity. However, design research can also be disruptive; it doesn’t simply build on what has gone before; it overhauls, starts again, rethinks and remoulds; it returns to first principles to avoid assumptions (both good and bad) of earlier iterations, and in so doing, it finds answers to questions that perhaps have not even been asked. This is why design research is so important, and why it is such a force for change [...] Design research is a creative and transformative force that can help to shape our lives in more responsible, sustainable, meaningful and valuable ways.

Indeed, since we understand design to cater not only to processes of solving concrete problems, design research should also tackle the broader wicked problems of society. As the role of the designer in society shifts from

working for the industry to working for society and local communities, so too will the definition of design research. As the temporal nature of design always influences its practice, its research should target not only the past and present but the future as well. Thus, the essence of democracy—the core of design practice in general—as well as the dialogue between design and the public sphere comes to the fore (Matthews et al. 2022). As we have seen, design research revolves around several key paths outlined in various professional terms. However, I wish to offer another complementing perspective that will help outline the disciplines’ course vis-a-vis complex and extensive future challenges. Before delving into this, let us create a common denominator for design research in general which includes a theoretical and historical background, empirical research which might include qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods or design-driven research methodologies (when needed), and extensive reflective interpretation of the project. Following this assertion, we can outline three major paths for design research.

1. Design theory: while this was spread across various sub-disciplines—design philosophy, design studies and others—it can now be focused under the banner of the relatively new sub-discipline of “design theory”. As its name suggests, design theory will delve into the theoretical dimensions of all disciplines of design. These can include reflection on design, defining various layers of design ethics, offering insights into wicked problems of design and more. Although this venue is related to practice, it has not yet necessarily been applied.

2. Industry-embedded design research: we might call this path research for design, or problem-solving research, but framing it as industry-embedded adds an important element. This path focuses mainly on two options, the first could be called “evolutionary design practice”, which means adding another rung to an evolving “ladder” (for example, another version of a tablet in an existing series). The second could be focused on designing an innovative, ground-breaking product (the Oculus Quest is a good example). The common denominator for both options is the focus on a specific problem that needs a visual/ material/digital solution through an act of design. For example, a new plastic-moulded chair will have innovative features but will rest on the previous research of its predecessors. However, ground-breaking design research, such as unchartered territories of healthcare design, for example, will need innovative research and understanding of unmapped user behaviour. Newly formed products to benefit newly evolved behaviours or situations will call for in-depth research and prototype testing.

3. Social design: this path, while practical in essence and might end with practical outcomes, stems from an ethical and critically defined set of values. This path might end with a design product, a suggestion or a blueprint, or even opt for a non-design alternative. However, the process will rely heavily on in-depth research, participatory strategies and active involvement of the relevant stakeholders and design partners

in each project. Contrary to the previous path, in social design, theory may play an important role. However, while in the first path, theory can be developed in and for itself, this path could integrate design theory as a basis for practice.

Like many other products of human creativity, design research stands at a crossroads. The foreboding clouds of the future herald the rise of populism, seclusion, violence, and disaster. In this dark unknown, we must broaden the possibilities of this important discipline, embed it throughout all venues of design practice and continue developing innovative and creative research tools, practices and methods. As Buchanan (2001, 4) mentioned more than twenty years ago, the true ancestor of design was Galileo Galilei. He writes that-

Instead of turning to investigate the human power or ability that allowed the creation of the instruments and machines of the arsenal of Venice, Galileo turned to an investigation of the two new mathematical sciences of mechanics. This reflects a general tendency following the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries to turn towards theoretical investigations in a variety of subject matters, laying the foundations of the diverse fields of learning that are now institutionalized in our universities.

Facing the dark clouds of the future, this has never been more relevant. And as a finishing thought, let us go back to the beginning. In the first act of the famous play

by Oscar Wilde, whose title has been borrowed for this essay, Algernon says: “I don’t play accurately—anyone can play accurately—but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life.” Design research is based on various traits, rules, professional etiquette and more, yet above all, and due to its unique influence on us all, let us at least be earnest.

Aristotle. 2010. Rhetoric, edited by Edward Meredith Cope and John Edwin Sandys. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bayazit, Nigan. 2004. “Investigating Design: A Review of Forty Years of Design Research.” Design Issues 20(1): 16–29.

Beyer, Hugh, and Karen Holtzblatt. 1998. Contextual Design: Designing Customer‐Centered Systems. San Francisco: Academic Press.

Blomberg, Jeanette, Jean Giacomi, Andrea Mosher, and Pat Swenton‐Wall. 1993. “Ethnographic Field Methods and Their Relation to Design.” In: Participatory Design: Principles and Practices, edited by D. Schuler and A. Namioka, 123–156. Hillsdale: Laurence Erlbaum.

Buchanan, Richard. 2001. “Design Research and the New Learning.” Design Issues 17(4): 3–23.

Clarke, A. J. 2011. Design Anthropology: Object Culture in the 21st Century. Vienna: Springer. Cross, Nigel. 2006. Designerly Ways of Knowing. London: Springer-Verlag.

Dixon, Brian S. 2023. Design, Philosophy and Making Things Happen. Abingdon: Routledge.

Dreyfuss, Henry. 1955. Designing for People. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Flusser, Vilém. 2014. Gestures. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Flusser, Vilém. 2016. The Surprising Phenomenon of Human Communication. Metaflux.

Frayling, Christopher. 1993. “Research in Art and Design.” Royal College of Art Research Papers 1(1): 1–5.

Gal, Michalle and JonathanVentura. 2023. Introduction to Design Theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

Geertz, Clifford. 2000. Available Light: Anthropological Reflections on Philosophical Topics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gunn, Wendy, Ton Otto, Rachel Charlotte Smith, eds. 2013. Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

IDEO. 2015. The Little Book of Design Research Ethics. https://www.ideo.com/post/ the-little-book-of-designresearch-ethics

Janning, Michelle. 2023. A Guide to Socially-Informed Research for Architects and Designers. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jonas, W. 2023. “A Cybernetic Model of Design Research Towards a Trans-Domain 1 of Knowing: Introduction to the Second Edition.” In The Routledge Companion to Design Research New Edition, edited by P. Rodgers and J. Yee, 24–25. Abingdon: Routledge.

Julier, Guy. 2006. “From Visual Culture to Design Culture.”

Design Issues 22(1): 64–76.

Lu Liu, Tsai. 2010. “Every Sheet Matters: Design Research Based on a Quantitative User‐Diary of Paper Towels.” Design Principles & Practices: An International Journal 4(1): 231–239.

Margolin, Victor, Sylvia Margolin. 2002. “A ‘Social Model’ of Design: Issues of Practice and Research.” Design issues 18(4): 24–30.

Matthews, Ben, Skye Doherty, Jane Johnston, and Marcus Foth. 2022. “The Publics of Design: Challenges for Design Research and Practice.” Design Studies 80: 1–25.

Muratovski, Gjoko. 2016. Research for Designers: A Guide to Methods and Practice. London: SAGE.

Rodgers, P. and Yee, J. 2023. “Introduction to the Second Edition.” In The Routledge Companion to Design Research New Edition, edited by P. Rodgers and J. Yee, 1–5. Abingdon: Routledge.

Simon, Herbert A. (1968) 2019. The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ventura, Jonathan, and Jo-Anne Bichard. 2017. “Design Anthropology or Anthropological Design? Towards ‘Social Design’.” International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation 5(3–4): 222–234.

Ventura, Gal, and Jonathan Ventura. 2017. “Milk, Rubber, White Coats and Glass: The History and Design of the Modern French Feeding Bottle.” Design for Health 1(1): 8–28.

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK FRIGATE CHAIR COLLECTION

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION FROM HUMANS TO HUMANS INNOVATION IN THE SERVICE OF USE. BODILY WELL-BEING AND THE CULTURE OF SITTING SUPERVISORS

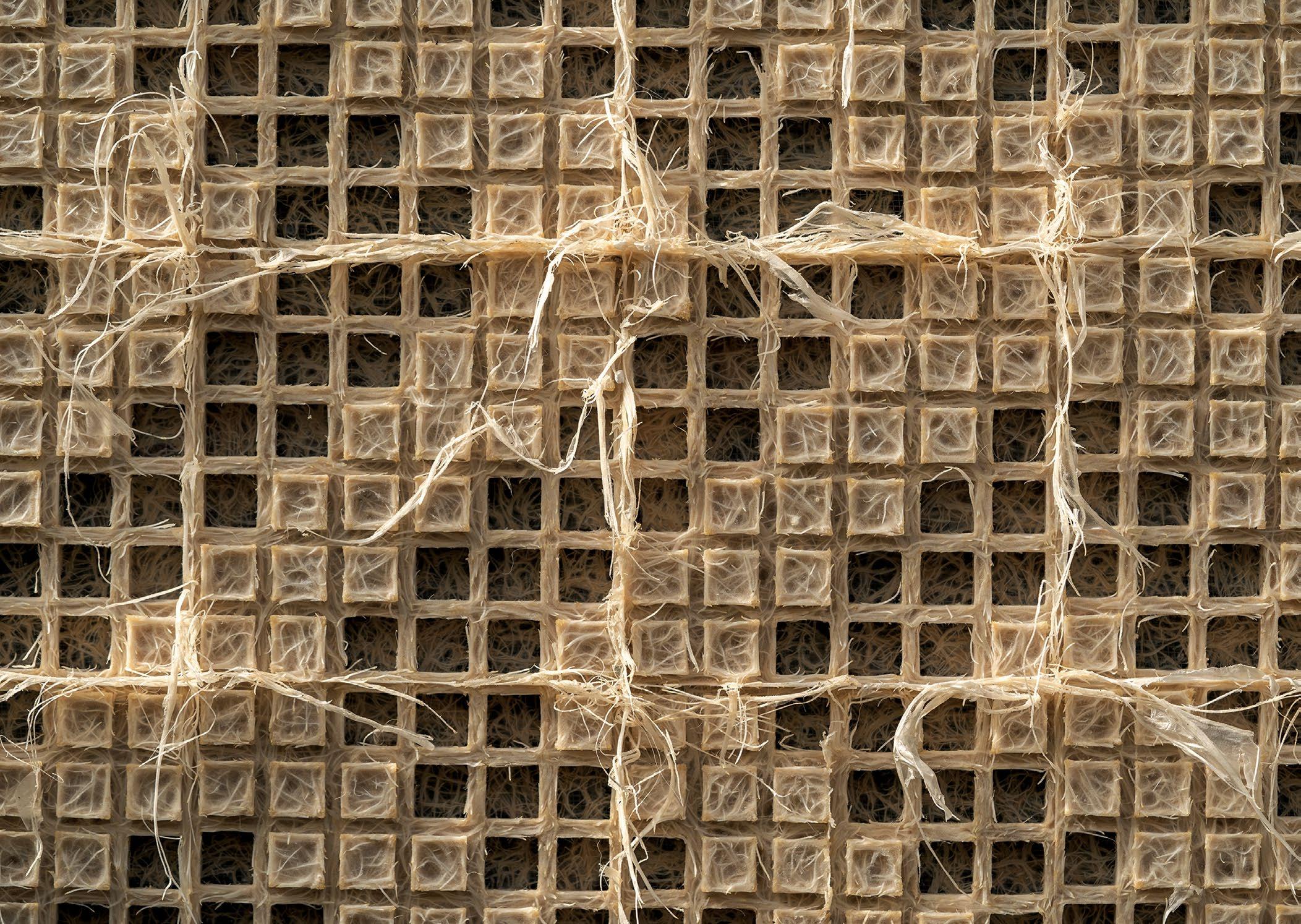

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK

BRAIDING POSITONS

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

APPLIED AUTONOMOUS

SUPERVISOR

JUDIT DROPPA PHOTO GÁBOR MÁTÉ

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK PLANT ARCHITECTURE ETUDES FOR PLANT FUNERAL HOMES

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

SPACE AND LANDSCAPE — PLANT ARCHITECTURE IN RURAL CEMETERIES SUPERVISOR ANIKÓ ANDOR

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK SPATIAL LEARNING UNIVERSITY SUBJECT

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION PRE ARCHITECTURA — LEARNING THROUGH SPACE

SUPERVISOR: ANDRÁS GÖDE

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK EXCURSION

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION EXCURSION

THE PICTORIAL REPRESENTATIONS OF BEING ELSEWHERE

SUPERVISORS

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK BEYOND THE FORM

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

INVERSE TRADITION — THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE PROVINCE IN THE FUTURE

SUPERVISOR: ANDRÁS FERKAI

PHOTO: ANDREA HAIDER

DLA IN MULTIMEDIA

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK STONE – METAMORPHOSIS

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

THE LAYERS OF THE ’MULTIPLE AND THE ONE’ — THE GRAPHIC PRINT LEAVING AS THE ELEMENT OF THE INDIRECT IMAGE CONSTRUCTION, ITS ALTERNATIVES IN CONTEMPORARY FINE ARTS AND ART EDUCATION

SUPERVISOR JÁNOS SZIRTES

PHOTO KRYSTYNA

BILAK

In the past two decades, MOME has become an important centre for the development of Design Cultures Studies. With its rigorous interdisciplinary exploration of the meanings and functions of design in contemporary societies, this still emergent discipline sits at the edge of the art school, both warmly embracing the practices it observes and gently—or not-so-gently—critiquing them.

This essay explores how disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity are understood and re-produced in design. In particular, it sets out how, within these, design is affected by its own advocacy and solutionism. Three disciplinary scenarios are mapped out here. The first resides within design as a discipline, noting that this is not fixed. The second considers design as a discipline whose identity is always defined in relation to others. In the third, the wider context of political economy that encourages interdisciplinarity in design is explored. A space might also be made for a more disinterested analysis—which Design Culture Studies would take up—and which may, in turn, lead to a more enriched and knowing practice of design.

There is no shortage of books that articulate what design is and advocate its benefits. Some explain how much design can take organisations or companies to a new level of consciousness—to flourish (Dunn, Cruickshank, and Coupe 2024); they may be dedicated to communicating how an organised and considered approach to design may help to build social innovations (Heller 2018); they may show what lies behind public infrastructures in terms of their design and how these can be strengthened (McKay and Meyboom 2022); or they could articulate how design can create new mindsets for organisations—particularly working in novel or emergent areas of public or commercial interest—through design research (Valtonen and Nikkinen 2022).

These books often begin with broad claims about the power and importance of design before recounting project after project that apparently proves the point. Perhaps the latter is done in the hope that the sheer number of examples is reason enough to take better notice of design. They tell the story but also ask you to believe the authors and their messages about design, mixing the reporting of design research with the championing of it. This mix of advocacy and reportage is also found at more focused and smaller scales. A certain orthodoxy in the presentation of design research has evolved in

conference papers and journal articles in order to do this. Articles in specialist design research journals often start with the statement of a wider problem—climate change, social inequality, loss of biodiversity, for example— followed by some brief namedropping of authors in design who have written about these problems. There then follows a description of the more specific geographical, human, or other context where the design research was carried out that touches on one or more of these problems. This is followed by a detailed explanation of the processes that took place to work with that particular problem. Devices—such as events, installations, montages, enactments, models—are frequently documented and displayed as part of the design experiment of finding a way to do things. Stereotypically, reflection on the design process is then synthesised into a summarising diagram. The core of the presentation is a focus on the doing of the design project and this forms the epistemological basis of the claims to knowledge that are being made. This tendency towards thick description of creative practices has a long history. Pamela Smith (2022) analyses medieval, early renaissance and enlightenment treatises on the arts or metiers that explain and codify craft skill. She observes four things useful to the question of disciplinarity: writing itself is a form of experimentation facilitating new ways of ordering practical knowledge; verbal articulation is a means of representing processes of coming to expertise; artistry as knowledge captures the characteristic of managing process (making decisions in the moment, for instance); there are specific ways of knowing in these fields, for example through what Smith calls

“material imaginary” or “artisanal epistemology” (similar, indeed, to what Nigel Cross [1982] long ago suggested). Put together, these resonate richly with how a discipline of design might be described. They are not dissimilar to what design researchers are trying to capture when describing and analysing “the project”. They also suggest that the process of writing, of recording and articulating, are also transformative, nudging the discipline into something else, feeling ahead in the semi-darkness, suggesting that a discipline is never static but subject to continual adjustments or challenges. This, in turn, removes the suspicion that a discipline might get stuck in its orthodoxies. As new artefacts, relationships and contexts come under consideration, the discipline changes shape as it gets pushed at its edges. Let us briefly consider what constitutes a discipline. Barry and Born (2011) provide a useful list:

• foundational knowledge—what needs to be known in order to do the discipline;

• methodologies—general agreement on how the discipline is done, how research is carried out—sometimes very central and agonistic, like in anthropology;

• understanding of objects of study—what the research focuses on;

• shared language—buzzwords, jargon, common points of reference;

• reflexivity—self-understanding of its origins, its ideological drivers, limitations, institutions that make it, internal tensions, a critical view of its academic and professional contributions and functions such that this knowledge is imbricated into its doing.

At its most introductory level, design fulfils this list (except the last one, but we’ll return to that). There are basic things that are and should be taught in the skilling of design students. Later on, its skills-based elements may vary between its specialisms: for instance, knowing what Swiss School typography is often foundational for graphic designers; knowing the difference between a model and a prototype is useful for industrial designers; descriptive terms like “user-research”, “white space”, or “clean lines” take on more or less significance according what is being designed. A rich language of description abounds in design, anchored to its disciplinary identities.

Disciplines are disciplining, as Simon Schaffer (2013) notes. They encourage restraint and constraint. Schaffer goes on to observe how Michel Foucault in his discussion of the processes of disciplining was most fascinated by two institutions: the prison and the school. And once you’ve been locked in somewhere long enough, you want to make a break for it, kill off your discipline and start afresh. This view seems particularly redolent in design literature: copious examples tell us that “the designer is dead” (Richardson 1993) or “it is a discipline without a centre” (Jonas 2010; Bremner and Rodgers 2013; Rodgers and Bremner 2017; Bailey et al. 2018).

Invariably, at some point in the kinds of project descriptions mentioned in the previous section, a claim is made to a particular kind of designing—growing design, posthumanist critical design, organisational ontological design, upstream legal design, inverted service design thinking, alter-disciplinary speculative design, or whatever. The thick description of the process leads to a declaration that it has discovered another way of designing that might have value for others. The overall cacophony that results often seems like a rhizomatic landgrab, where new subsub-fields upon new sub-fields are constantly invented and re-invented. However, the different processes that are described and lead to such declarations are seldom compared. Each seems to be a sub-discipline with a membership of one lone designer.

This dynamic of claiming of designerly territory bears some resemblance to a lot of the self-presentation in the design profession, where studios stake claims to particular kinds of design processes. In part, this is to clearly inform potential clients what to expect. But it is also a way of differentiating themselves and make claims to uniqueness in a competitive market for design services. The same may go for the proliferation of design specialisms—new trends like organisational design, legal design, strategic design, experience design, UX, UI, IxD, CX, and so on tumble out of the profession as new clients, design objects or design processes get identified.

This is not a criticism. It is merely an observation of a sociological phenomenon that has something to do with the conditions of designing. The outward gaze of designers and design researchers—where they are always adjusting to whatever problem they find themselves in—means that their chief concern is engaging with whatever client, public, or technology that is presented. This is further compounded by the lack of normative standards and requirements to be a designer—unlike, say, architecture, accountancy, or medicine. While, and as we have already seen, there are basic, foundational aspects to design education, they do not add up to legally enforceable or coherent standard requirements across the discipline. The result, as Wang and Ilhan (2009) observe, is that designers self-define themselves relationally to other bodies of knowledge rather than to their own discipline. They call this process ‘sociological wrapping’ as designers draw on knowledge that was hitherto external to their profession. In turn, this knowledge becomes intrinsic to it; its re-positioning and translation is always contextual and unstable rather than universal. Thus, legal design brings in understandings of how different specialisms and systems of law are enacted, service design pulls in the knowledge of specific customer offers and processes according to the particular kind of commercial or public service offering, and so on.

The same “sociological wrapping” takes place in much design research as projects touch on various problem spaces, professional or public contexts, disciplinary approaches, technological fields or otherwise. To claim that design is therefore everything, in a disciplinary

sense, can make for big statements. In inventing an overarching design specialism, van der Merwe (2010), for example, claims that his concept of “cyberdesign”:

[…] is design scholarship. It is the academic study of any and all design phenomena. It addresses the physical, psychological, aesthetic, social, cultural, political, and historical concomitants of design, design creation, design perception, and design discourse. It incorporates a blend of sciences and humanities and is grounded in design practice. It involves a wide range of non-design disciplines and corresponding research methods. (9)

The idea here is that designers and design researchers attend to all these different demands. This results in a design discipline that is nothing but a practice of doing other stuff and transgressing its own disciplinary makeup. According to this view, the outward, networked notion of design is backed up by a range of literature from the humanities and the social sciences that argues that rhizomes, ecosystems, and relations prevail over centres and directives. After all, haven’t you read A Thousand Plateaus (Deleuze and Guattari 1988), The Rise of the Network Society (Castells 1996), or Reassembling the Social (Latour 2007)? And if there aren’t any centres in our sociotechnical environments, why should design have one?

There is, it seems, an a priori understanding of design as being eminently and unavoidably interdisciplinary or, at least, not very disciplinary. An ambition to go beyond one’s own discipline and find one’s natural home in dialogue with other disciplines doesn’t come solely from an intrinsic motivation. Contemporary conditions in the academy are meeting structural changes outside it. My own institution, Aalto University—which was founded just over ten years ago—has a distinct vision of encouraging “interdisciplinary collaboration” across its six schools. Indeed, its architecture is arguably conceived to encourage openness and teamwork, with the copious inclusion of internal windows, multiple breakout rooms and open meeting spaces. As stated on the website, this materialises the university’s ambition to:

[…] create a better world by bringing quantum engineers, urban economists and fashion designers to collide and to elevate each other. Our way is to accelerate curiosity and responsibility towards solving the biggest challenges in the world. (Aalto University 2023)

This aligns “interdisciplinarity” with ambitions to address what are termed “complex problems”. It has been argued that multi-level, multi-scalar complex problems can only be properly considered by teams of multiple

specialists working together (Ese and Ese 2022). Connected to this viewpoint, design and, particularly, design thinking have taken up a renewed significance. Their focus on empathy for the user, their collaborative stakeholder and problem space mapping, their iterative ideation through materialisation, prototyping and testing aligns with much of the language and practices to be found in agile and fast product and service development. These tools provide a focus for such mixed teams to speed the process through. Elsewhere, an interdisciplinarity that is less problem-solving focused and geared more towards generating material and digital products and services has come to dominate economic imaginaries in recent years (Gerosa 2020; Simpson 2021). Needless to say, the “start-up” has become a paradigmatic organising trope for this thinking.

As the last two sections have suggested, it is impossible to produce a unified theory of design. Nonetheless, it is safer to talk in terms of broad palettes. Problems in the design process are identified and addressed in different orders and with varying motivations. Perhaps what the multiple and variable models of design and design thinking have that Kimbell (2009) identifies have in common is that problems are not taken as singular. Rather, the interdisciplinary team works with a series of problems— sometimes conflicting, sometimes coherent—within the overall programme of work.

But what drives and shapes this enthusiasm for interdisciplinary, solutionist work relating to design and a related start-up paradigm? There are probably multiple socio-economic and political factors, but here I suggest

the following four background drivers. First, there has been a shift in approach to innovation that focuses processes around foregrounding optimum outcomes as opposed to the organisational structures that deal with these. In public sector innovation, for example, we have in places seen a move towards so-called “Outcome-Based Budgeting” to get to solutions fast and ensure complex welfare problems are pursued pragmatically (Julier 2017, chap. 8). This often means working across departments, producing, for instance, a health solution in sport and leisure. Second, a turn in economic and urban planning has emphasised the spatial clustering of specialisms for example, as through such instruments as “creative quarters” or (replacing the latter) start-up hubs (Moisio and Rossi 2020) to encourage interdisciplinary interaction and fertilisation. Knowledge intensities are formed that demonstrate and symbolically champion a certain entrepreneurial, solutions-oriented mindset. Third, digital culture has laid emphasis on a certain hegemonic power of the software-supported ‘product as solution’ achieved as a synthesising agent in response to multiple problem considerations (Morozov 2013). A fourth driver of this start-up imaginary has been the presence of historically low interest rates from 2009 until 2020, itself facilitating a venture capital boom in gig economy platforms, crypto currencies, and driverless cars, but also many other design-led new products and services (McNamee 2020). These considerations may seem disparate and indeed distant from a discussion of interdisciplinary design research. However, together they produce a certain entrepreneurial sensibility, setting a discursive field to which design research is also connected.

This turn towards interdisciplinarity has profound benefits for design research in finding new collaborations and places for application. For this author, though, a nagging feeling exists that the kinds of speedy solutionism and pragmaticism that characterise this narrative of interdisciplinarity is rather breathless. Critical discussion of the conditions, motivations, and epistemologies seems to be left behind. More prosaically, and as Felin et al. (2019) argue about lean start-ups, if there isn’t a strong theoretically reasoned hypothesis for the product, then flimsy results endure. This is where Design Culture Studies may have a role in ensuring more robust reflexivity prevails in design research to help address such issues.

So far, design and design research have been described in three ways. The first has been as a form of crafting, where close attention is paid to the minutiae of running a project, its various stages of materialisation and social interaction, and what its outcomes suggest in the wider vocabulary and taxonomies of design. The starting point is very much within the designing that may nudge the discipline along by providing new objects, techniques, ways of perceiving or understanding the design process. The second is where its meaning is found outside design in relation to something else (a client, a public or another academic discipline,

for instance). Here, the notion of a core of the discipline is arguably dispensed with; design is always outside itself in this narrative. The third has been in terms of it satisfying certain contemporary demands for innovative, interdisciplinary work in solving complex problems or, more prosaically, iterating “cooler” goods and services.

The first and second framing of disciplinarity perhaps belong closer to the internal cultures of design but are no less important if one is to understand how particular ways of enacting and reporting design are shaped. In short, these considerations address that missing element in the design discipline: reflexivity.

The last framing pays attention to factors that are mostly extrinsic to design, suggesting that design is drawn or encouraged into interdisciplinary arrangements through the influence of a range of economic and ideological factors. How design and design research are shoved in certain directions, how certain ways of doing design get foregrounded over others and how problems and their solutions are identified, organised, and valorised are important questions for their participants to consider.

To return to a point made at the beginning, a significant part of the work of design is in its advocacy. After all, designers have to win clients and design scholars have to secure research funding. They are engaged in competitive acts of what Pierre Bourdieu (1984) termed “needs production”. They have to make their case for why what they do is important, effective, and can lead to better times. Herbert Simon’s characterisation of design as “changing existing circumstances into preferred ones” (Simon 1969, 111) still haunts the design bibliography (Barnett et al. 2020;

Verganti et al. 2020; Wakkary 2021). It is therefore difficult to put aside ambitions towards solutionism, improvement, or optimisation. These are hardwired—or disciplined— into the discipline. Being transgressive, moving outside, and slamming doors behind itself is an intrinsic part of design culture.

Leaving design solutionism and advocacy behind firstly requires self-understanding of these in the first place— to adopt a tried and tested approach in psychoanalysis. Once this is done, design becomes a different place. This is where the field or discipline (we haven’t decided yet) of Design Culture Studies sits. It is a somewhat humble, minority specialism that has some relationships and differences with Design History and Design Studies. Space constraints do not allow for a full exposition of its background and direction here. In any case, an attempt to build a heroic history is liable to accusations of mounting a premature and mythologising disciplinary hagiography before its time. I accept, however, that my attempt to differentiate and advocate Design Culture Studies as a practice is open to the same critique I have already addressed to design in general. However, at least Design Culture Studies does not promote design itself—just a way of studying it.

Design Culture Studies begins with the disinterested analysis of design without any initial pretence to its improvement. It studies what produces design, how the problems that design addresses are understood or accepted as problems, what designers do (discursively as well as practically), how design is engaged with in everyday life, utilitarianly ways, symbolically, and others besides. These analyses are achieved through a different

relationship to its disciplinary relatives. Who these are may be very similar to design and design research—psychology, economics, sociology, literary theory and so on. But they are not instrumentalised to improve designing but to enrich understanding.

Design Culture Studies itself may be consigned to being an analytical form of study rather than projecting itself into the future of what could be. Its dominant tendency is to look backwards or sideways rather than forwards. Can Design Culture Studies feed back into design research in terms of not just generating understanding and awareness drawn on its interdisciplinary activities? Can it bring another sensibility to designing?

To answer these questions it might be necessary to re-frame what the designer’s role is. This might mean that the designer abandons the prioritisation of improvement, or, at least, their assumption of design being central to any betterment. Instead, design research becomes a learning space for collaborative investigation into the conditions that produces it and its role in the production of those conditions. Of course, there are many, many design solutions that are still needed as more problems are produced. But understanding how design problems are produced, both at the macro- and micro-scales, is part of the work of Design Cultures Studies and of design itself.

Aalto University. 2023. “About Aalto University.”

https://www.aalto.fi/en/ aalto-university

Bailey, Mark, Alison Pearce, Nick Spencer, Katja Mihelic, Brian Harney, and Katarzyna Dziewanowska. 2018. “Beyond Disciplines: Can Design Approaches Be Used to Develop Education for Jobs that Don’t Yet Exist?” In DS 93: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education, 538–545. The Design Society.

Barnett, Michael, Irene Henriques, and Brian Husted. 2020. “Beyond Good Intentions: Designing CSR Initiatives for Greater Social Impact.” Journal of Management 46(6): 937–964.

Barry, Andrew, and Georgina Born, eds. 2013. Interdisciplinarity: reconfigurations of the social and natural sciences. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bremner, Craig, and Paul Rodgers. 2013. “Design without Discipline.” Design Issues 29(3): 4–13.

Cross, Nigel. 1982. Designerly Ways of Knowing. Design studies 3(4): 221–227.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1988. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Dunn, Nick, Leon Cruickshank, and Gemma Coupe. 2024. Flourish by Design. London: Routledge.

Felin, Teppo, Alfonso Gambardella, Scott Stern, and Todd R. Zenger. 2020. “Lean Startup and the Business Model: Experimentation Revisited.” Long Range Plan 53(4).

Gerosa, Alessandro. 2020. “The Hipster Economy: An Ethnography of Creative Food and Beverage MicroEntrepreneurs in the Italian Context.” PhD thesis. University of Milan.

Heller, Cheryl. 2018. The Intergalactic Design Guide: Harnessing the Creative Potential of Social Design. Washington, D.C: Island Press.

Jonas, Wolfgang. 2010.

“Design: The Swampy Foundation of Our Conception Of Man, Nature, And The Natural Sciences.” Baltic Horizons 11(110): 16–25.

Julier, Guy. 2017. Economies of Design. London: Sage.

Kimbell, Lucy. 2009. “Design Practices in Design Thinking.” European Academy of Management 5: 1–24.

McKay, Sherry, and AnnaLisa Meyboom. 2022. Design Capital: The Hidden Value of Design in Infrastructure. London: Taylor & Francis.

McNamee, Roger. 2020. Zucked: Waking up to the Facebook Catastrophe. London: Penguin.

Moisio, Sami., and Ugo Rossi. 2020. “The Start-Up State: Governing Urbanised Capitalism.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52(3): 532–552.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2013. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. London: Allen Lane. Richardson, Adam. 1993. “The Death of the Designer.” Design Issues 9(2): 34–43.

Rodgers, Paul A., Craig Bremner. 2017. “The Concept of the Design Discipline.” Dialectic 1(1).

Schaffer, Simon. 2013. “How Disciplines Look.” In Interdisciplinarity: Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, edited by Andrew Barry and Georgina Born, 57–81. Abingdon: Routledge.

Simon, Herbert A.1969. The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Simpson, Isabelle. 2021. “Cultural Political Economy of The Start-Up Societies Imaginary.” PhD thesis, McGill University.

Smith, Pamela H. 2022. From Lived Experience to the Written Word: Reconstructing Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Valtonen, Anna, and Petra Nikkinen, eds. 2022. Designing Change: New Opportunities for Organisations. Espoo: Aalto University.

Van der Merwe, Johann. 2010. “A Natural Death is Announced.” Design Issues 26(3): 6–17.

Verganti, Roberto, Luca Vendraminelli, and Marco Iansiti. 2020. “Innovation and Design in the Age of Artificial Intelligence.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 37(3): 212–227.

Wakkary Ron. 2021. Things We Could Design: For More than Human-Centered Worlds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Wang, David, and Ali O. Ilhan. (2009). “Holding Creativity Together: A Sociological Theory of the Design Professions.” Design Issues 25(1): 5–21.

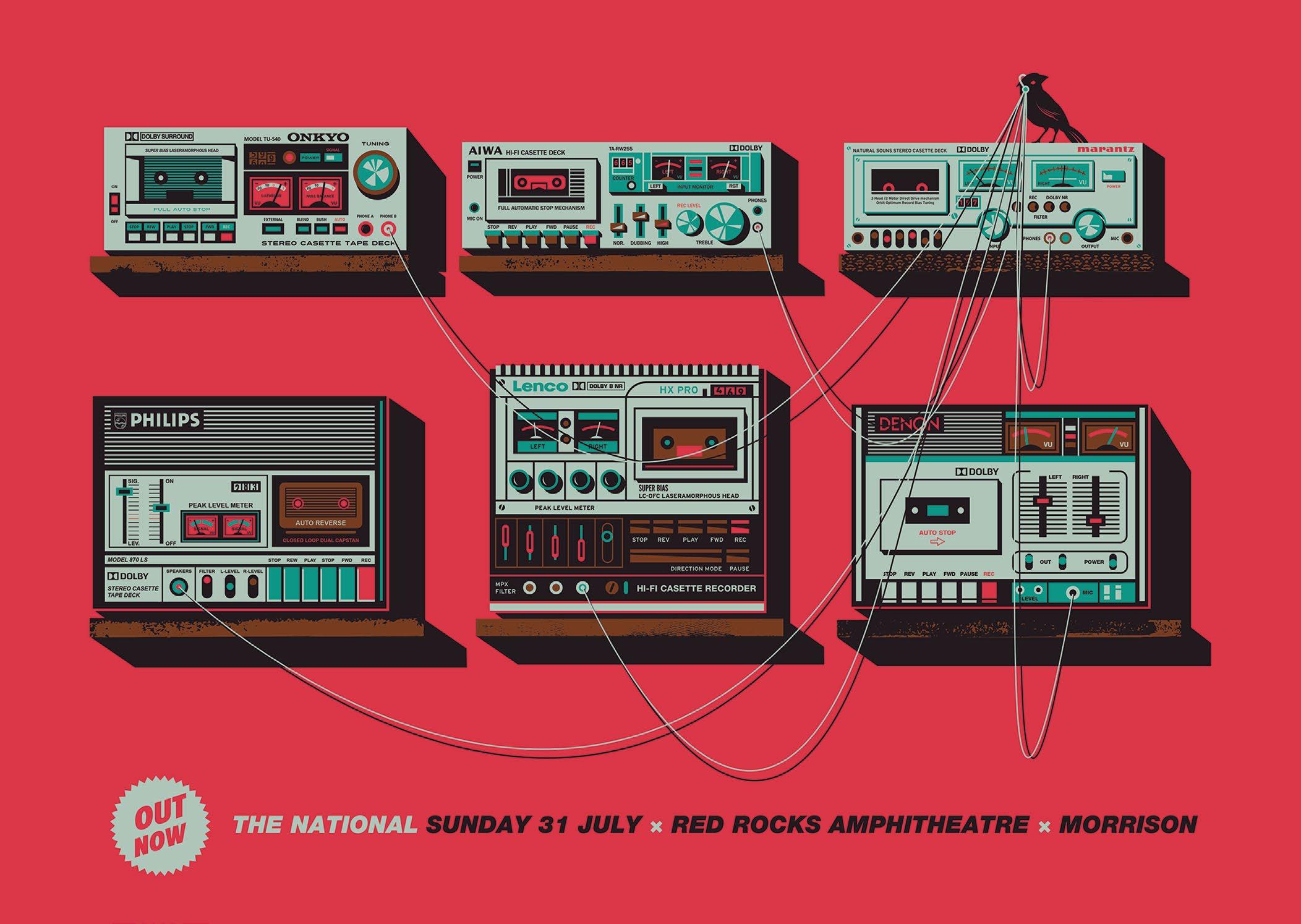

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK THE NATIONAL — SCREEN PRINTED GIG POSTER

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION GRAPHIC SCREENPRINTING HISTORY, METHOD AND DEVICES SUPERVISOR: DÓRA BALLA

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK NATURING_MATERIAL IN MOTION

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION MATTER IN MOTION_ NATURING INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN THE PLASTIC AMBITIONS OF TEXTILE AND THE FORMS OF EXPRESSION IN CONTEMPORARY ART SUPERVISORS

HEDVIG HARMATI

DÁNIEL BARCZA

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK BLOOMFIELD HOSPITAL

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION THE MYTH OF IDLENESS

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK

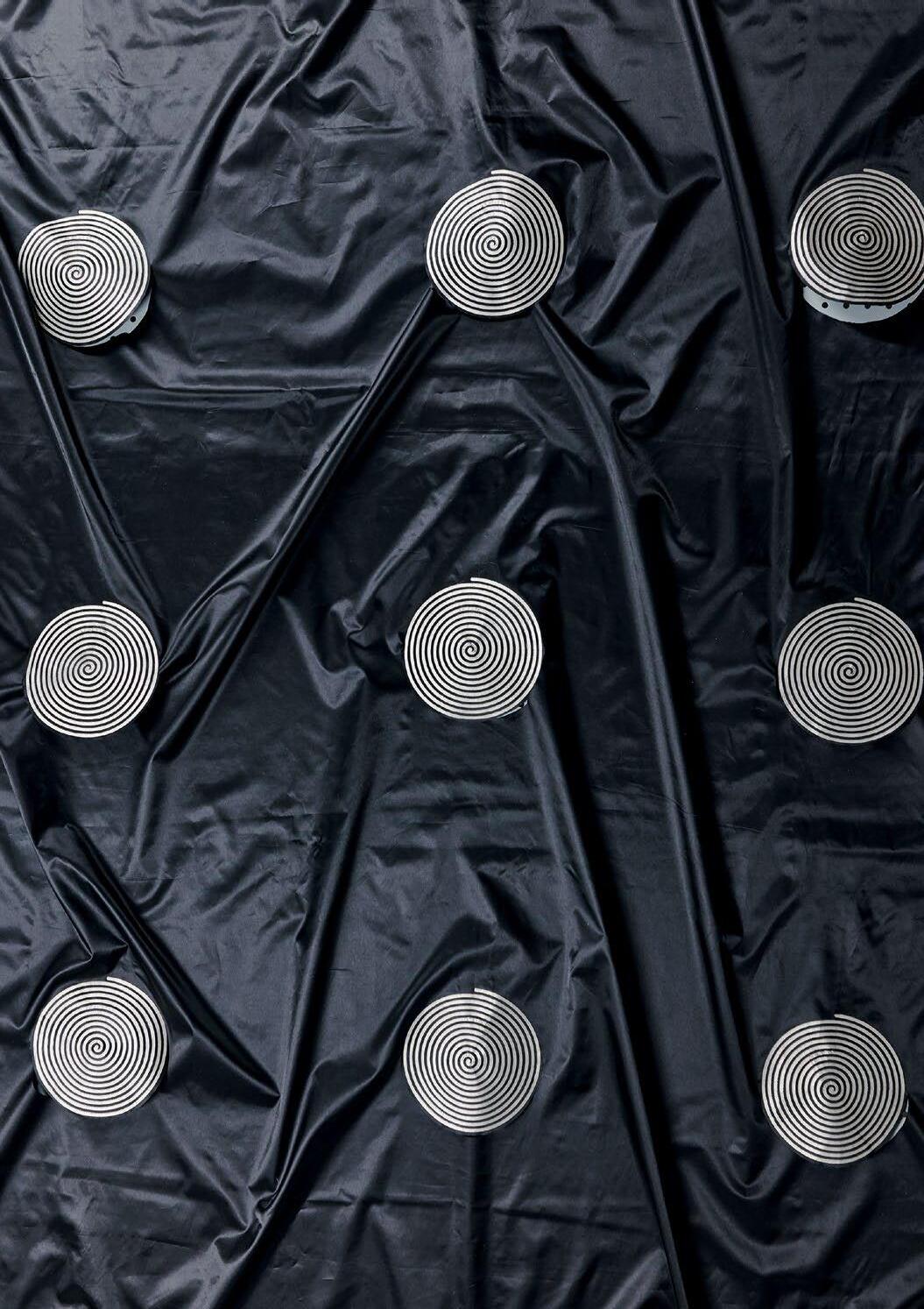

SOFT SOUND

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

SOFT INTERFACES — CROSSMODAL TEXTILE INTERACTIONS

SUPERVISOR

HEDVIG HARMATI

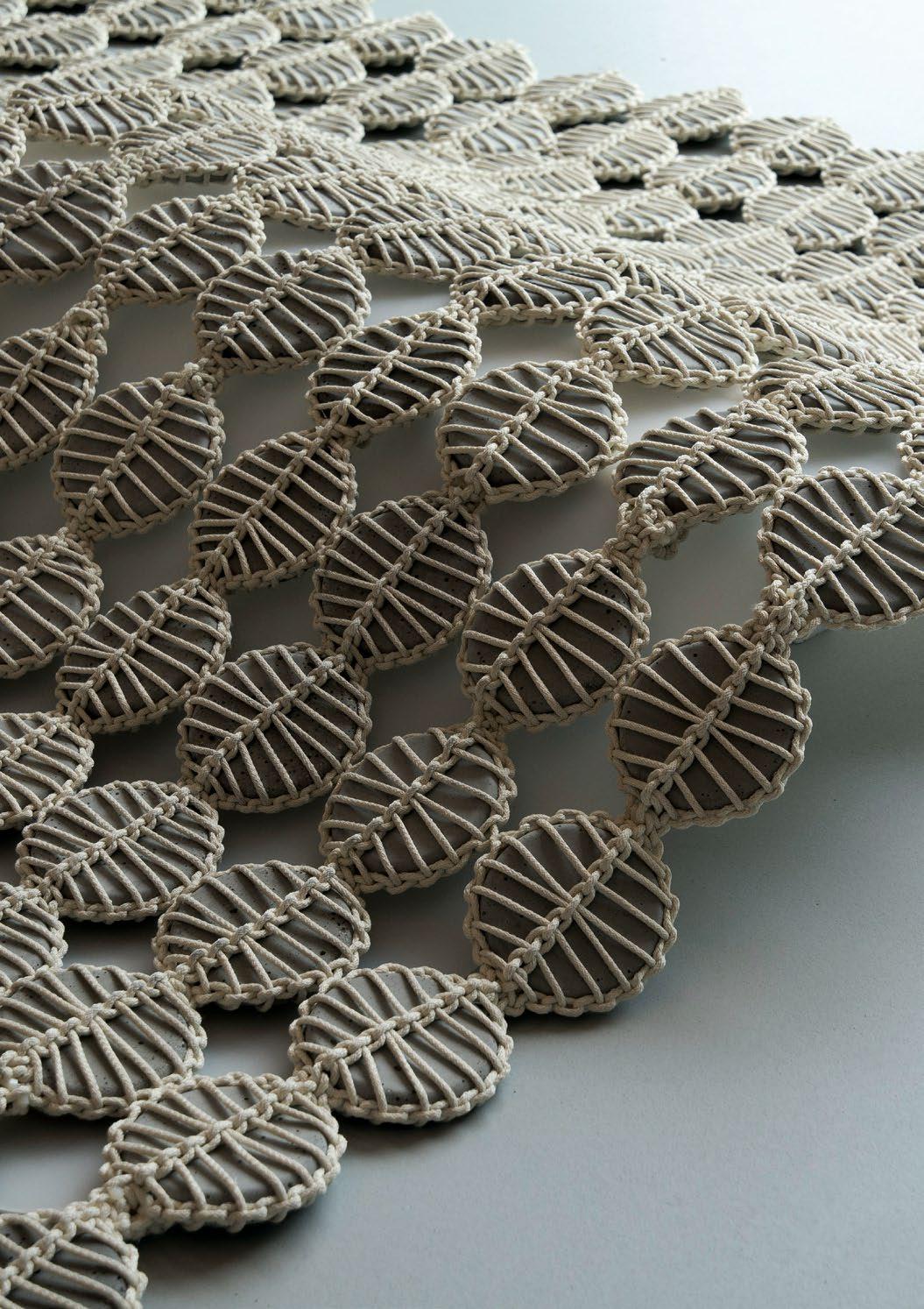

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK CHAINS — ORDER AND CHAOS 2.

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION CERAMICS AND SPACES

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK

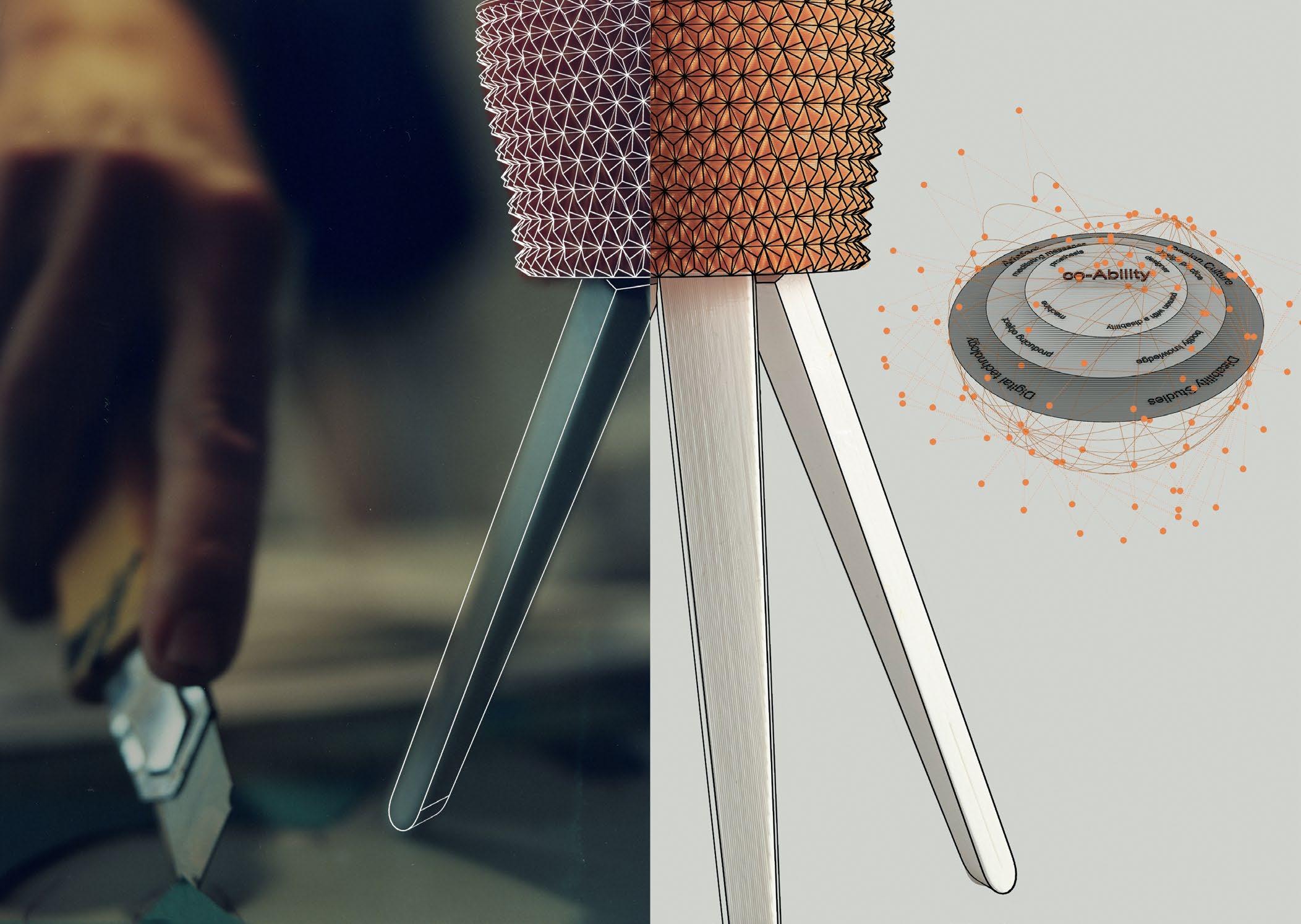

RAWFICTION

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

RESTORATIVE RAW MATERIAL CENTRIC DESIGN

SUPERVISORS

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK DEVELOPMENT OF THE GARDENS OF THE BENEDICTINE ARCHABBEY OF PANNONHALMA, LABYRINTH AND AMPHITHEATRE

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION INITIATIVE WAYS — CONTEMPORARY MONASTERIES IN LIGHT OF THE RULE OF SAINT BENEDICT SUPERVISOR ANDRÁS FERKAI

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK TONE

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

GATES

TITLE OF THE MASTERWORK

BOOK ABOUT THE BOOK — THE KNER PROJECT

TITLE OF THE DISSERTATION

THE BOOK AS THE PROCESS OF THE VIRTUALIZATION OF THE PHYSICAL OBJECT IN THE LIGHT OF GRAPHIC DESIGN

SUPERVISOR LÁSZLÓ ZSÓTÉR PHOTO ISTVÁN ORAVECZ

MOHOLY-NAGY UNIVERSITY OF ART AND DESIGN

There is a seemingly paradoxical image that is probably known to everyone in the art world: René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (This is Not a Pipe) from 1929. Notwithstanding relentless academic debates, its meaning is paradoxically rather clear, as revealed by Magritte himself: “The famous pipe. How people reproached me for it! And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it’s just a representation, is it not? So, if I had written on my picture “This is a pipe,” I’d have been lying!” (Torczyner 1977, 71)

Decades later, Roland Barthes claimed that, on the contrary, a photograph—also a form of pictorial representation—has naturally something tautological about it and a “pipe […] is always and intractably a pipe” in it (Barthes, 1982, 5). The compelling nature of the new medium in Barthes’ age undoubtedly influenced his understanding of the photographic image as identical to the object photographed. Still, there is no reason to deny the lingering validity of Magritte’s fundamental division between a pictorial image of an object and the object itself as is obvious from our next example as well.

In 1965 Joseph Kosuth introduced his notorious conceptual work titled One and Three Chairs where an everyday chair sits alongside a photograph of the same chair and a printed dictionary definition of the word chair. By distinguishing between the discursive and visual encoding of the object and the object itself, the conceptual artist primarily claimed to embody the philosophical question already apparent in Marcel Duchamp’s

ready-mades concerning the “transfiguration of commonplaces” (Danto 2013). Simply put: what makes an everyday object—together with its representations—an artwork? It is a lesser-known fact that One and Three Chairs is a redesigned installation of Magritte’s emblematic image Les mots et les images. This one depicts a horse, a painted image of the horse on canvas, and a man pronouncing the word horse with the following statement: “Un objet ne fait jamais le même office que son nom ou que son image” [an object never performs the same function as its name or its image] (Magritte 1929, 33). A text is a text. An image is not a text. An object is neither a text nor an image. Following the above one can formulate a hypothesis according to which—unlike the humanities and social sciences approach to art criticism—artistic research is more about the words’ state of being words, that is, of their “wordness”; and in turn the “imageness” of the images and the “objectness” of the objects. To put it differently, artistic research is primarily about the agency, materiality, and performativity of the literary, visual, and spatial artworks themselves and not about the classical academic analysis of them (Borgdorff, Peters, and Pinch 2020, 3–5). In this sense, we come closer to the Romanticist idea already expressed by Johann Georg Hamann in Aesthetica in nuce (1762), who claimed that “poetry is the mother tongue of the human race”, and to the modernist and avantgarde understanding of words in poetic contexts being more authentic, that is, more aesthetic than logical or functional in their everyday use for communication. The fictional use of words is capable of creating unique (life)worlds. This worlding can be seen in a magical

1

On Attila József’s theory of the “magic of names” (névvarázs) see Tverdota (2018).

2

The new translation of Szerb’s novel (2006 [1934]) by Len Rix was by comparison wellreceived in the United Kingdom.

(Attila József), kabbalistic or combinatorial (Mallarmé 2011), or an alchemical (Rimbaud 2010, 284–296) way in which one can immerse oneself in the miraculous dimensions of reading. 1 For example, when Antal Szerb (notwithstanding his unusually extensive academic knowledge of the complex topic) wrote a brilliant novel, The Pendragon Legend (1934) about Rosicrucianism instead of a general scholarly survey, his fictional approach enabled the ironic ambiguity concerning Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism which helped him avoid the artistic and scholarly traps that ambushed Umberto Eco’s world-famous Foucault’s Pendulum (1988) and The Search for the Perfect Language (1993) decades later (Penman and Szentpéteri, 2022). 2 The latter proved to be a fairly unreliable scholarly survey, driven too much by the poetic approach of bridging philological gaps with fantasy. The former, on the contrary, is a typical postmodernist novel overwritten and packed with rather boring academic expositions in unrealistic circumstances impeding readerly immersion, without which reading is a painful endeavour instead of a pleasure.

Likewise, when images and objects are experienced and handled in their own right, you cannot only “read” (Gadamer 2022) them as if they were discursive texts to be interpreted hermeneutically if you want to avoid linguistic imperialism or strong textualism that regards iconographical and spatial or architectural sorts of cultural products as readable discursive phenomena (Gadamer 2022; Ferraris 2014, 132–139). Similarly, a building cannot be interpreted as an image without losing fundamental aspects of it being a building that shelters and provides

a living space. Such a simple error would be an iconographic reduction that regards cultural products of architectural sort as pictorial representations (Szentpéteri 2010, 18–24). Employing linguistic imperialism and iconographic reduction could not be further from the real purposes of artistic research, which focuses much more on aesthetic embodiment than logical understanding driven by pure reason.

It is no surprise that the technical terminology of artistic research still sounds quite artificial and forced since the field of interest is still emerging from the period when art and design colleges gradually became part of the wider world of research, development, and innovation-driven universities and alibi terminology was needed to meet the requirements of the new context. However, it is worth mentioning at the same time that the genealogy of artistic research is rooted in early modern times and the birth of modern science. “A history of artistic research will have to uncover in detail what moments over time attest to that desire to bridge the domains or to traverse” the boundaries of science and art that were established during the seventeenth century rise of science when its lifeworld began to grow apart from that of religion and art (Borgdorff, Peters, and Pinch 2020, 3). This often-discomforting differentiation and institutionalization of different

discourses that resulted in painful losses in lifeworlds has been mitigated to a certain extent by the modern philosophy of art and Romanticist poetry since their beginnings. Philosophical aesthetics, for example, successfully emancipated sensuous knowledge, that is, aesthetics from its inferior gnoseological position to an equal rank with rational knowledge or logic (Nannini 2022). With this turn, the Cartesian polar dualism of mind and body became to a certain extent obsolete, or at least, aesthetics and logic became dynamic counterparts.

All in all, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, one finds intriguing examples of artistic research ante litteram. In his groundbreaking monograph The Poetic Structure of the World: Copernicus and Kepler, Fernand Hallyn (1990) argues that the formation of scientific hypotheses did not differ so much from the poetic invention in the early modern era as has been observed from the nineteenth century onwards. In Hallyn’s mind, the early modern scientific imagination was quite imbued with mythic or poetic ingenuity, as is clear from, among other examples, the fact that the new heliocentric model is ultimately derived from Neoplatonic and mannerist theological and artistic prerequisites, rather than pure mathematical calculations.

It is equally intriguing how Ferdinando Bologna and then in his footsteps Troy Thomas show us that Caravaggio’s notorious naturalism can be seen as a unique pictorial embodiment of the scientific and philosophical thoughts of the so-called Italian natural philosophers of his age such as Galileo Galilei, Giordano Bruno, Bernardino Telesio, Tommaso Campanella, and Giambattista

Della Porta, among others (Bologna 1992, 138–190; Thomas 2016, 163–173). 3 These authors turned to the things themselves in a pre-Kantian, non-phenomenological way, and questioned things “juxta propria principia” (through their proper principles) to use Campanella’s formula. This late Renaissance thing-oriented attitude emphasized a fundamental division between things extramental (i.e. physical entities), intramental (i.e. rhetorical contents), and words. For example, the way Caravaggio paints the light on his canvas entitled The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600) grabs the ambiguity of the metaphysical and physical understandings of light in a fascinating manner that philosophical treatises could never have done (Thomas 2016, 149–162). Similarly, the post-Tridentine theological ideas refuting the Protestant concept of sola fide are brilliantly captured by Caravaggio’s Seven Acts of Mercy (1606–1607), strengthened by the painter’s naturalism that again casts everyday poor people from the narrow Neapolitan alleyways as models, and meticulously observes their humble reality seemingly notwithstanding, but indeed in gospely harmony with the sacred themes evoked by the painting. Likewise, early modern examples of printed books that enhanced embodied reading are also potential examples of artistic research avant la lettre. One of the most compelling books of Michael Maier—the worldfamous alchemist and defender of the Rosicrucian style of thinking— Atalanta fugiens (1618) is a rich composition of texts: mainly poems and their explanations, images, and musical notes. As the title page says:

3 Bologna’s critics often claim that he is doing simple Zeitgeistism without direct philological proofs of Caravaggio being influenced by Italian natural philosophers. This is addressed in the latest movie about Caravaggio where he meets Giordano Bruno sentenced to death in a prison in Rome (Placido 2022).

Atalanta running, that is New Chymical Emblems relating to the secrets of nature, accommodated partly to the eyes and understanding, with figures cut in copper, and sentences, epigrams, and notes added, partly to the ears and recreation of the mind, with fifty musical flights of three voices, of which two may correspond to one single melody appropriated to be sung with distichons, not without singular delectation, to be seen, read, meditated, understood, distinguished, sung and heard.

As the new digital edition palpably proves, Maier meant his meditative book to be an instrument for both mind and body driving more than one of the reader’s senses at the same time while delving into the ever-mutating world of nature (Numedal and Bilak 2020). In his mind, this multisensorial method was much more efficient than logical explanations for revealing the true meaning of jokes of nature (lusus naturae) (Findlen 1990; Szentpéteri 2007).