With One Accord

With One Accord

Volume Five, Issue 2 Spring 2025

EDITORIAL

Lucinda M. Vardey

EXPRESSING COMMON FAITH AND WORSHIP

Michael Pirri

A PERSONAL JOURNEY WITH THE ROSARY AND HOLY MARY

Tania Brosnan

MIXED MARRIAGE: EMBODYING ECUMENISM

Kathleen MacInnis Kichline

THE MAGDALA INTERVIEW: EMBRACING IN THE IN-BETWEEN

Emily VanBerkum with Lidiya Lozova

“A NEW WIDER AND DEEPER ECUMENISM”

John Dalla Costa

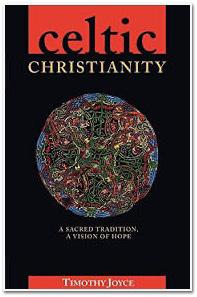

BOOKS OF INTEREST: ON CELTIC CHRISTIANITY

Lucinda M. Vardey

When compiling a book of women’s prayers from all religions, I found that there were five virtues shared across cultures. One is “unity.” Edith Stein, St. Teresa Benedicta of the Cross wrote, “The deepest feminine yearning is to achieve a loving union…such yearning is an essential aspect of the eternal destiny of woman. It is not simply a human longing but is specifically feminine.”1 The desire for loving union is pertinent to most mystics, particularly women; in fact it informs their lives and their interior prayer. But Jesus prays that all believers be interiorly and exteriorly united “just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me” (John 17:21).

Ut Unum Sint: On Commitment to Ecumenism Pope John Paul II wrote that being children of God and one family, the Church is to be for all an “inseparable sacrament of unity” (# 5).

John Dalla Costa reminds us that ecumenism has a much larger scope. Etymology reveals the core meaning of the Greek word ouikomene to be “the whole inhabited world.” This represents an invitation to think widely and deeply about unity.

In contemporary usage, though, ecumenism is primarily associated with dialogue between Christians, and receptivity to the gifts from other different denominations. In my experience, I have for decades appreciated and valued how gospel music enlivens faith and worship. And I recall the nourishment of long dinners talking about God and scripture with my evangelical friends. These moments of encounter have provided diversity in ways to pray, love God and be in relationship with Jesus.

In this issue Michael Pirri outlines the progress made from Vatican II and suggests ways in which we can more readily, as lay people, create liturgical opportunities to pray together. Tania Brosnan, previously a Methodist and now a Quaker, shares how reciting the rosary for peace began a growing relationship with Mary and had a ripple effect on others. Kathleen McInnis Kichline’s accounts of balancing worship and prayer in mixed marriages, gives us a glimpse of how to embody ecumenism in the everyday.

The commitment to ecumenism is widely shared among Orthodox Christians. Associate editor, Emily VanBerkum enters into a conversation with Lidiya Lozova from Ukraine about her call to the work of ecumenism, peacemaking and praying with icons, her experiences living and working now outside her country, and her suggestions on how to witness injustice and respond from our hearts.

A book review of Celtic Christianity: A Sacred Tradition, a Vision of Hope by Benedictine monk Timothy J.Joyce concludes this issue. It describes the pagan origins that easily embraced Christianity particularly in Ireland, and outlines the basic tenets that informed the culture of Celtic Christianity over the first 12 centuries. Along with the present re-emergence in Celtic-Christian consciousness, the reflections in this issue all contribute to a hopeful model for a renewed and holistic Christianity that manifests the unified desire of Jesus that we all be One.

Lucinda M. Vardey Editor

“Ecumenism (is) a duty of the Christian conscience.”

(Pope John Paul II)

Ut unum sint: on commitment to Ecumenism 1985 No. 8

Michael Pirri is a member of the Magdala Conciliary and Director of Community Engagement at St. Basil’s Catholic Parish, in Toronto, Canada. In this role he fosters meaningful connections within the parish, as well as in the wider community. In addition to being Production Co-Ordinator of With One Accord, Michael also works as a small business and non-profit consultant, where he focuses his attention on developing purpose driven missions, and implementing complementary management strategies. Michael leads the music program at St. Aidan’s in the Beach Anglican Church in Toronto. He is Chair of the Royal School of Church Music Canada, Toronto Chapter, and serves on the nationwide executive of the same organization. Additionally, he is the Editor of The Liturgical Psalter, Plainsong Edition, an innovative online Psalter launching in 2025. Michael is a recent graduate in the Master of Sacred Music program at Emmanuel College of Victoria University in the University of Toronto.

Michael Pirri

Commemorating the 500 th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017, The Lutheran World Federation and The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity published Communion in Growth: Declaration on the Church, Eucharist, and Ministry. This document builds on the ecumenical dialogue called for in both Paul VI’s Lumen Gentium and Unitatis Redintegratio in 1964. Communion in Growth was prompted by Pope Francis in 2016 as he invited theologians to explore the possibility of shared communion between the Lutheran and Catholic Churches.

While the current official teaching on shared communion requires a shared ecclesiology, discussions and practices begun in the period following Vatican II continue in episcopal circles today. They include the specific understanding and meaning of

“communion” and the present official directive that if the Eucharist is requested by non-Catholic baptized Christians, it can be given under certain circumstances.1 The theological basis for this is evident in Lumen Gentium which opens up salvation outside of the Roman Catholic Church, and strengthens links between Baptism and the Church as the Mystical Body of Christ. The link between Baptism, Eucharist, and the Mystical Body of Christ is also focussed on in The Ecumenical Directory, the Directory for the Application of Principles and Norms in Ecumenism published by The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. As American priest, Virgil C. Funk wrote “The Eucharist is, for the baptized, a spiritual food which enables them to overcome sin and to live the very life of Christ, to be incorporated more profoundly in Him and share more intensely in the whole economy of the Mystery of Christ.”2

The tension that has developed between a common ecclesiology and a common worship remains a major stumbling block to unity caused by differing beliefs about sacramental worship. Jesuit theologian, Thomas Rausch notes: “To accept a liturgical practice from another community is to acknowledge a shared faith which comes to expression through a ritual. The same holds true for doctrinal formulations. When the representatives of churches in dialogue are able to arrive at a statement of consensus or agreement on those issues which have previously divided them, the completion of the dialogue process represents more than the mutual acceptance of a linguistic formula; it also implies the recognition of a common faith.”3

How is it possible to describe what is indescribable? Is there a particular way of praying to God, a specific set of phrases that truly shape spiritual realities? Finite linguistic formulas for expressing God are inherently flawed. By comparison, an artist could paint several versions of a scene before settling on a colour palette, which does not make any of the prior attempts less effective in representing that scene, because combined together they are not equal in representing the scene itself. Could the same analogy be used in describing the language of worship? Is it right to believe that early Christians did not celebrate a common Eucharist because of a lack of uniform language?

In the Roman Missal, all four Eucharistic Prayers do not convey the exact same realities yet this does not diminish their validity. Instead, this plurality communicates distinct aspects of the person of God, and of Christ’s sacrifice that no single Eucharistic Prayer, no matter how perfect, could ever completely encompass. Can the admission of the inadequacy of language itself be a path to widening our embrace of ecumenism?

The aim of ecumenical worship is, perhaps, to share in the catholic (i.e. universal) understanding that our lives, and our prayers, are common simply by being companions and followers of Jesus. This is where non-Eucharistic celebrations ought to thrive. Yet, instead, there seems to be an ever-widening gap between worshipping communities. For example, congregations are reluctant to engage with one another in communal celebration of Evening Prayer. There is a particular hesitance on the part of liturgical

traditions (Catholics, Anglicans, Episcopalians etc.) whose members, almost always, insist that communal prayer be led by someone who is ordained.

I believe it is up to lay people, empowered by Synodality, to lead the way to create ecumenical connections through prayer and community. When speaking about the desire for a sole expression of worship in the Anglican Church, Anglican priest, Percy Dearmer (1867-1936) wrote words that are as fresh today as they were in 1923, “Diversity in worship has been a sign of organic unity […] Uniformity is uncatholic”4 For Dearmer, “True catholicity is that which paid attention to the whole (kata’holos) according to the whole, the Greek phrase from which the word ‘catholic’ is derived, not by making the whole look exactly like one part.”5 Perhaps Dearmer, seeking to bridge the gap between Anglo-Catholic and Evangelical Anglicans, unintentionally explored a path for understanding ecumenical relationships. The same perhaps can be said of Pope Francis: the Synod on Synodality may yet prove to be a catalyst that empowers lay people to form their own ecumenical relationships and liturgies. This will not come about by adapting existing liturgies—or even modelling new ones after existing structures—but instead through the organic and unpredictable path set forth by the Holy Spirit. ■

Tania Brosnan was brought up a Methodist. After taking the East Anglican Ministerial Course in England which opened her to other traditions and spiritualities, she trained in spiritual direction and was ordained a presbyter in the Methodist Church in 2009. She has worked as a hospital chaplain, radiographer and mammographer, finishing her career as manager of the Breast Imaging Unit in York. She has now retired to the Yorkshire Dales where she lives a quiet, contemplative life with her husband and worships as a Quaker at the Leyburn Local Meeting, North Yorkshire.

Tania Brosnan

It was at Morning Prayer in 2023 while reciting Psalm 125 with its last verse “Peace be upon Israel!” that my personal journey with the Rosary and Holy Mary began. Like so many others, I was in despair and shedding tears over the war in Israel.

As a former Methodist and now Quaker, I have never owned a rosary and knew nothing of the structure around praying the Rosary. I didn’t even know the words of the Hail Mary and, if truth be told, I had always been fearful of Mary, believing her to be beyond my reach as a woman!

For months I had felt sadness and a helplessness at the amount of violence I was witnessing through all the media outlets. Wars, confrontations, abuse allegations, stabbings…I could go on. We have all experienced something similar. Then a light shone into my darkness.

On 25th November 2023 I attended With One Accord’s virtual webinar entitled Nonviolence and Peace: The Reality of Jesus Today. Fr. John Dear talked of the gospel of Jesus being a Gospel of Total Nonviolence. He challenged us to do three things in order to live a life of nonviolence:

(i) To practise nonviolence towards self.

(ii) To practise nonviolence toward all people and creation.

(iii) To join the global grassroots of nonviolence to change the world.

How was I going to respond to that challenge?

In mid-December my answer came. I heard about the Global Rosary at an online gathering of women with a shared spirituality. The commitment was to pray the Rosary

each day for the first hundred days of 2024, each decade devoted to the following intentions:

1. For the Healing of Violence against Women, Children and those of Different Gender Identities.

2. For the Healing of Violence against the Earth.

3. For the Healing of Violence against Religious Affiliations, Practices and Beliefs.

4. For the Healing of Violence between Nations and Races.

5. For the Healing of Violence in Families and Homes.

I was sure this was an invitation from the Divine, and in my enthusiasm, I said “Yes.”

As I reflected on nonviolence, I recognized that anything in creation that is subject to violence is denied its own freedom. So in solidarity with all who experience any kind of violence, I decided to curtail my own freedom and remain for those hundred days in my hometown, choosing not to travel and visit friends or family.

At first I stumbled with the words and the repetition of the Rosary. I found it helped to also have a visual focus and chose an image to represent each decade.

Praying the Rosary was now a totally sensory experience. Wherever I happened to be I could see, feel and hear the Rosary. I loved the rhythm of the prayer; it became for me a song in praise of the Divine.

As I sat each evening reciting the Rosary, the words began to disappear. I could hear them but rather than from my mouth, they arose from the centre of my being; they became my desire, the desire that is God. By the end of the Rosary I would find myself in a place of contemplative prayer, silent in God. As Wendy Robinson, psychotherapist and associate of The Community of the Sisters of the Love of God, observed in her essay, Exploring Silence, not only was I exploring the silence of God, the silence of God was beginning to explore me.

Within this intimate space I discovered a love for Mary. She would sit with me in the silence, holding this sacred encounter, sharing herself as Mother, Sister, Friend and Enabler. During those hundred days, we became companions: she was no longer aloof and unattainable, she was a woman who had also responded with a “Yes” to God’s invitation.

Forty-seven days into 2024, on 16th February, it was announced to the world that Alexei Navalny, the Russian opposition leader, lawyer and anti-corruption campaigner, had been killed in a detention camp in the Russian Arctic. I was appalled and saddened.

However, instead of despair my reaction was to add a sixth decade to my Rosary; For the Healing of Violence against Prisoners of Conscience and War.

It was now becoming evident that my encounters with the Rosary were firmly planted and flourishing in my heart.

I was beginning to witness how an openness to the Divine enables the grace of God to scatter the seeds of the Spirit.

During those first hundred days of delight in praying the Global Rosary, I spoke enthusiastically to others about my joyful discovery of this precious and enriching way of praying. I chose to share in my Quaker Meeting for Worship and at an ecumenical Lent group about my deepening awareness of Holy Mary, of the Rosary as the gateway into contemplative prayer, of the hope for the world and all its peoples, in offering all into the circle of the Rosary, where it is received and held.

To my amazement I began to have responses to my ramblings. On hearing about the Global Rosary, a Catholic man, who was brought up to recite the Rosary as a child— and had become negative toward this way of praying in adulthood—found his faith reignited in his desire for its treasures. He became one of the many pilgrims committed to praying for one hundred days.

A Quaker woman said she had been given a rosary many years ago and had no idea what to do with it or why she had been given it…now she knew! An elderly Anglican woman spoke emotionally of her mother’s precious rosary beads. She felt the Communion of Saints and joined the Global Rosary prayers for nonviolence and peace. A Methodist woman bought her first rosary at the age of 76, and informed me she is still using it as part of her spiritual practice.

I wrote this article just over a year after first hearing John Dear speak. How little I had known then what blessings were going to unfold. I continue to use the Rosary as a spiritual practice, being open to other themes for each decade. This enriches, nourishes and deepens my prayer life.

In praying the Rosary I have found my song and I want to continue to sing it and receive its numerous blessings. I pray that maybe I have encouraged a few others to join in the song.

Let me end with some words from Jim Cotter, Anglican priest and wordsmith:

God of mystery and revelation at the extremes of our distress and despair when you are the only hope left, let us hear your name again, and so take courage on the journey.1 ■

The Webinar referred to in this article Nonviolence and Peace: The Reality of Jesus Today can be viewed on News and The Meeting Place at www.magdalacolloquy.com

“Ecumenism must mean the unity of the Church in the service of life, not the unity of a particular ecclesiology or dogma.”

(Mercy

Amba Oduyoye)

Daughters of Anowa: African Women and Patriarchy

Kathleen MacInnis Kichline holds a Masters of Divinity from Seattle University where she also served as adjunct faculty teaching on spiritual retreats. Currently retired from Seattle, she continues active ministry in retreats and presentations both online and in person. She is the author of “Sisters in Scripture: Exploring the Relationships of Biblical Women” (Paulist Press, 2009) and “Never on Sunday: A look at the Women NOT in the Lectionary” also published in Spanish. Her most recent books are “Why These Women: Four Stories You Need to Read Before You Read the Story of Jesus” (2022) and “Royal Wives: David & His Wives: Michal, Abigail & Bathsheba” (2023). www.sistersinscripture.com

Kathleen MacInnis Kichline

Jesus used the parable of the Good Samaritan to answer the question,“Who is my neighbour,” a query that grew out of the Golden Rule, “Love your neighbour as yourself.” If the questioner, an expert on the law, was looking for a loophole he was given anything but. Jesus answered in the particular, for it is in the particular that faith is lived out. It is, to use a colloquialism, “where the rubber hits the road,” or to paraphrase in theological jargon, “where orthodoxy meets orthopraxis.”

Marriage is the up-close and personal meeting ground between this theory and practice. Certainly, it is true that all couples navigate the various stages of life, from newlyweds learning to accommodate differences, to elderly couples caring for one another’s infirmities. But when it comes to ecumenism, it is those couples from different denominations who truly embody it, who live out ecumenism in the particular.

My husband and I exchanged vows on 11th May 1968 in a Catholic ceremony at the US Coast Guard Academy Chapel in New London, Connecticut. As baptized persons— he, Lutheran, and I, Catholic—we were the ministers of that Sacrament. Our words to one another, the promises we made, effected the grace of Matrimony by virtue of the power that is ours as baptized persons. The priest was there as witness, along with family and friends on both sides of the aisle, but it was we who officiated. To be honest, those were not the thoughts going through my mind in that moment, though I knew them to be true, but I have returned to that foundational belief many times in the years since. Additionally, marriages between Catholics and the nonbaptized, though not sacramental, are also blessed and holy in the eyes of the Church as people have the natural right to marry, a union blessed by God.

Often, in a mixed marriage one person is more dedicated to their religious practice than the other and this sets the tone for the marriage. This was our pattern. Brian’s promises, after all, were only to allow me and our children the freedom to practice our Catholic faith which he did commendably, including with Catholic schools, auctions, donations, volunteering, etc. But his own faith practice languished even as he found no attraction to the Mass when he attended. I recall the times when I struggled to get children up, dressed, and off to church on my own, or when I felt guilty at the envy stirring inside me on seeing other couples kneeling side by side in a pew.

Our story in a mixed marriage has its share of mixed blessings. Some things, like raising our kids, we did well; some things, like Sunday mornings, we didn’t do well. Only in retirement, when I encouraged my husband to pursue his own spiritual journey, did he return to the Lutheran church of his childhood. He is now flourishing and walking the path of a faithful companion of Christ.

Those for whom solo-on-Sunday becomes too hard to maintain without their partner’s support, find much of the actual practice gradually falls away. Its decline is not to be a judgement upon their belief in God. It is certainly not predictive of what is next on their faith journey in the mystery beyond our knowing. It is simply the pattern of their lived experience.

There are also examples of singular commitment. We have a friend who grew up in New York City, the child of a Catholic mother and a Jewish father. His parents were married in the Catholic Church, had twin sons, and for reasons not known to me, the mother rarely went to church. Nonetheless, the father went to Synagogue every Saturday and then on Sunday took the boys by the hand and walked them to Mass while he had coffee across the street. Each family finds their own path.

Sometimes couples marry who both have a strong commitment to their own religious tradition. In this case, an easy optout by one of them is not a choice. Both the challenge and the reward are seen to be greater. I spoke with Ron shortly after Rose, his wife of 56 years, had died. As he tells it, his family was “very Lutheran” and hers was “very Catholic.” Neither set of parents objected to their marriage but

he said, they expressed their reservations. Ron and Rose had their children baptized in a Lutheran church, but they attended Catholic schools through to their early teens. Rose went every Sunday to Catholic Mass and Ron joined her and the children often, also serving on the Parent/Teacher Association at the school. And Ron continued to worship at the Lutheran church whenever he was able. After elementary school, their daughter continued attending weekly Mass with her mother, but their son chose to go to the Lutheran services. With the children grown, and the freedom of retirement, Rose and Ron eventually settled into a pattern of attending Saturday night Mass and Sunday morning Lutheran service. Ron said, “We found that we just liked it better being together. We’d rather go twice together than go once and be alone.” Rose’s funeral Mass at the Catholic Church was attended by a large contingent of Lutheran parishioners and pastors who had come to know and love her as one of them.

For many years, I worked as a pastoral associate in Catholic parishes. Among my duties was to originally meet with couples preparing for marriage. Later they would meet with the counsellor and the priest, but mine was a first-entry ministry of hospitality and gentle conversation. I always listened deeply to their stories, especially the stories of their faith. Even with those who professed no particular faith or were uncertain of what they believed, I never wavered in expecting that I would encounter the Holy in our conversations. Over the years I found this always to be true. In honouring the faith journey of another, however hidden it may be, we allow the light of God’s grace to be revealed.

For me, there is no other model for

mixed marriage or for ecumenism than the belief that God is involved in the life of the other in ways beyond our expectations, knowledge and understanding. To create a language to express that and to live out its particulars is a holy walk.

Those in a mixed marriage who honour the walk of their partner, provide a path for us all. Theirs is the story and the example of how to truly embody ecumenism. ■

Lidiya Lozova has been a researcher at the European Humanities Research Centre at the University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, a book translator and editor. She completed her Bachelor’s and two Master’s degrees in cultural studies and intercultural humanities from National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy and Jacobs University Bremen, Germany. Her doctoral thesis focussed on History and Theory of Culture/Art History at the Modern Art Research Institute of the National Academy of Art of Ukraine in 2015. Her dissertation examined the theological dimension of the Leningrad School of Avantgarde Art from the 1920s-1960s. Her current research project is at the University of Exeter in England and concerns the social ethos of Eastern Christian icons, specifically modern icons and icon-like images that appear during wartime in Ukraine. Her areas of academic interest include iconography, Orthodox social ethos, the encounter between traditional Orthodox spirituality and the challenges of modernity, and religious peacemaking.

Emily VanBerkum is Associate editor of With One Accord. For more information on her background please visit our website.

John Dalla Costa

John Dalla Costa is an ethicist, theologian and author of five books. For more on his background please visit our website.

The original meaning of the word ecumenism is worth recovering as it could provide the spiritual resources to confront the issues from ideology and politics that are causing so much pain, violence and splintering today. We have primarily understood and used the word ecumenism as meaning to promote engagement and unity among the divided Christian Churches. However, by etymology, the word ecumenism actually signifies “those who dwell in the inhabited world.” If we dare take to heart the deeper possibility invited by this meaning, then our horizons for spiritual learning and contemplation shift radically. Not only all religions and cultures, but all the earth’s natural bounty become wellsprings for enriching our faith and values as disciples of Jesus Christ.

This is but one implication discovered in Tomáš Halík’s profound and accessible book The Afternoon of Christianity. This book, in my view, prepares the heart for the Holy Spirit by reading the signs of this time with implications that are as unsettling as they are inspiring. Drawing on his experiences as a Czech Catholic priest, theologian, and philosopher shaped by life under communism, Halík

stresses that this moment when faith seems overwhelmed by secularism is not of decline, but of transition. Indeed, the metaphor of “afternoon” signifies something immensely positive—if we grasp it—which is to assume the responsibility for maturing in one’s faith.

Breaking our usual certitudes about faith and Church, Halík helps create the space within and outside our comfort zones so that, by grace, both creativity and conversion may incubate. Two processes are required:

1) To be contemplative, to pray not with words, but in silence so as to allow a kind of mystical wisdom to be born within. In this “unknowing,” we fathom what doctrine so often dulls, which is the profound wonder, awe and love of God.

2) To take seriously the example and teachings of Jesus, bearing the cross of self-offering to bridge the many divides that are rupturing society, or our natural home, and even our Church. Love and kenosis (self-offering) are synonyms. Just as Jesus manifested the style of God’s love by holding nothing back, the maturing of Christian faith grows and lives by this kind of self-offering.

The interplay between the contemplative and the kenotic helps us escape the exclusions of religious certitude by making space for the dignity and needs of others. As Halik explains, “The afternoon of Christianity will not be a time of expansion but of deepening. It

will not be a time of power but of witness.” This may seem like a call to reform Church structures, but it is more an acknowledgement that Church structures are collapsing for being so out-of-step with the spiritual needs of believers and non-believers. While religious institutions may be suspect as never before, the human heart—now disoriented by the failures of the Enlightenment, of modernity, of science and technology—aches for the attentiveness and care that Jesus taught as the supreme commandment to love. In this milieu, Halík explains that, “Secular people are not our enemies but often our fellow pilgrims, just taking different paths. We must listen before we speak.”

Among my original motivations for studying theology was Swiss theologian Hans Küng’s call to raise consciousness for ethics on a global scale. Because of my background in business, I always interpreted the need for ethical dialogue as not only for interfaith or inter-religious, but also inter-sphere or inter-disciplinary. Mature faith requires that we stand on the very boundaries that others regard as exclusionary— listening and responding through the tensions between faith and science, between Islam and Christianity, between Catholic Social Teaching and business, between left and right and all the other perceived opposites. Dialogue is not easy. It requires outward empathy and compassion for others, even toward those who threaten us. At the same time, it demands that deeper participation in the Gethsemane prayer of Jesus, trusting and surrendering to the love of God.

Tomáš Halík invites dialogue with atheism, secularism, and other religions—not as threats, but as opportunities to deepen and clarify faith. As Jesus explains in Luke’s Gospel, “the good measure” that God pours out in overflowing abundance into our laps, is not earned by reciprocity or from following doctrine or laws. This blessed participation in God’s generative gifts comes from the kenotic practice of loving enemies, doing good to those who hate, blessing those who curse you, and praying for those whose violence and indifference do harm (cf.Luke 6:27-38).

Taking into account the opportunities in the “afternoon” of Christianity makes a practice of ecumenism neither a process nor an option, but an intrinsic and indispensable feature of being baptized into the life of Jesus Christ. ■

Lucinda M. Vardey

Timothy Joyce is an American Benedictine monk of Irish descent. Spurred by visiting an exhibition of Early Irish Art in Boston in 1978, his subsequent research and teaching led him to publish twenty years later, Celtic Christianity: A Sacred Tradition, a Vision of Hope.

So thorough is this book that it could be entitled A History of Irish Spirituality and Faith and its Evolution of Practices throughout the Centuries. Much of its content traces the historic and spiritual evolution of the Celts, particularly the development of Celtic spirituality within Christianity in Ireland. This book deepens our awareness of not only the roots of Celtic faith and culture but also what had been lost and why, what was regained and what is being rediscovered now in our time.

The Celts were the indigenous people of Europe, known as the “first Europeans.” Never a unified empire, they were more a “confederation of tribes united by religious outlook and practices.” They had a reputation for being fierce warriors as well as artisans. Unlike prevailing Greco/Roman customs, women held property, kept their dowries, and even fought alongside the men. The Christianization of the Celts was birthed as a grassroots movement independent of Rome and, after Saxon kings vied with the Roman Church, the Celtic Church lasted as a “distinct institution” within the larger Church up to the 12th century. Thereafter it became instead “a worldview and spirituality.”

As Rome had never invaded Ireland, and St. Patrick had brought Christianity to the isle, the Celtic Christian Church flourished. The story of how the original Celts embraced Christianity certainly provides an example of peaceful ecumenical conversion. The ancient Celts told stories and believed in the “power of the word” so there was a natural receptivity to scripture as well as the symbols of the liturgy and the sacramental “bread, wine and oil.”

The author considers St. Patrick to be “the archetypical Celtic Christian” because he loved prayer, sacred scripture, being close to God in the natural world, and had an openness to the voice of God in visions and dreams. All these elements were part of the original Celtic spirituality, as was the number “3.” Hence Trinitarian consciousness was not a problem, with the shamrock, symbol of Ireland, providing its 3-leafed clover as an emblem for faith, hope and charity.

Nor was the communion of saints a foreign idea to the Celts. They believed that ancestors and heroes of the past lived in the present: they saw reality “from the lens of eternity, with no beginning or end, no distinction of the seen and unseen” and they

would pray for protection against the “dark forces.”

The major difference during the early centuries of Christianity, was that the Celts did not lose their relationship with the land and place. Unlike much of Augustinian theology embraced by Rome, Celtic Christians kept their inherited nondualistic approach to their beliefs and practices. For instance, there is a belief in the presence of God in both spirit and matter, that God is found “in all of created nature.” Celtic tradition believed in a graced universe, “full of the grandeur of God.” God’s immanent presence was sensed in the sacredness of the land and place, in islands and on mountains, that all the earth and its creatures “was a source of beauty to delight in order to live with that reality.” This aspect of the earlier Celtic tradition continued to be central in Celtic Christianity, where the doctrine of reparation for sins and punishment was largely absent. Pilgrimages too had formed a part of Celtic worship, with journeys to sacred wells and places perceived to be holy from ancient times. Church governance was more communal and relational. Women continued to have positions of authority and leadership and there is evidence that deaconesses called Conhospitae had a liturgical role in the Eucharist.

The fusion of Celtic culture and faith with Christian belief began to flourish with the emergence of the monasteries. The life of a monk was viewed as

a way of Christian life, not just for those in monasteries, but even when married with children. Religion had to be an integral part of life in general.

The monasteries were built on Druid foundations. Monks were called “the new Christian Druids” the old Druids being the religious leaders, lore keepers and advisors. Celtic monasticism was lived quite differently from the traditional Roman Church structures. Monasteries were formed as villages with beehivetype huts. These served as centres for “commerce, trade, agriculture, recreation and education.” They included men and women, priests and lay, and sometimes a bishop or two. Abbesses too were leaders of these communities, the more well known of them being St. Bridget, who was acknowledged a bishop, and St. Ita, who was renowned as a confessor. Over time, however, the Rule of Benedict was imposed on Celtic monasteries and in the 12th century the Cistercians and Augustinians orders overwhelmed the old Celtic way of monastic life.

The author gives us a detailed account of the suppression of Celtic Christianity with the invasion of the Normans, the English Reformation with Cromwell’s colonization of Ireland in the 17th century. The displacement of the Irish from the tragic potato famine of the 19 th century further dissipated the Celtic sensibility. The Roman Church “swallowed up in clericalism” institutionalized Christianity in Ireland with over 2000 parishes, which eroded much of the Celtic original “force and flavour.” In this top-down

hierarchy God was segregated from the land, no longer an imminent presence but “out there somewhere.” Sacraments were all expected to be received within a Church building, and even the famous Irish wake was forbidden (although it did continue as a people’s tribute). This institutional “renewal” brought in a number of the religious orders and among them the nuns who provided education and service to the poor.

The wave of Irish emigration to the U.S.A., Canada and Australia brought on by the Great Famine, spread the Irish Christian experience into the world. In fact, the author correctly claims that Irish immigrants were largely responsible for the way the Catholic Church developed in those countries. Along with this spread, came the renewed interest in Celtic roots and culture, perceived as a “Gaelic Renaissance” which was also happening in Scotland and the northern parts of England and Wales. With their genius for words, Irish writers in the 20 th century contributed much to “the Celtic gift of Soul” as did organized pilgrimages, music, prayers and blessings. Gaelic language courses were soon being offered in leading universities.

History is always a great teacher and this book serves as an excellent background to what is presently unfolding within our Church and world. With the diminishment of participation in institutional religion, a turning to the land as sacred, to a practice of creation spirituality is especially growing due to the challenges with climate change. The movement from dualism to unity is being reflected in the present synodal process, of equality between men and women, lay and clergy, an openness to embrace other faiths, and a way of praying together to the one common God.

The author notes how Celtic spirituality can be a model for much of what is now occurring. “To wish to learn from the Celtic Christian,” he writes, “is to wish to sense the passionate presence of God in all of life. It is to find God in the ordinary events of life, love, eating, working, praying. It is to learn from the ancient saints, the medieval poets, the later prayers…that everything is grace and blessing…aiming at bringing into consciousness the holiness of every moment.”

With the present growth in secularism, re-introducing Christianity in the Celtic vein could well provide a doorway for new communities. The two areas of community and personal spirituality can certainly be exercised and experienced. The non-hierarchical, non-patriarchal organization of faith could provide men and women equal leadership. Episcopal de-centralizing that Pope Francis had recently called for aids response to local needs and concerns. Mystical spirituality needs to be taken seriously and allowed expression, metaphoric sensibilities are to be awakened, and Christian life to be experienced not just on Sunday but every day of the week, every moment of the day.

One insight that greatly touched me was the idea of identifying and uniting “the twin sisters,” Mother Church and Sophia (holy wisdom), in equal embrace, as both are essential.

What the Celtic Christian Church once was, it can be again— a prototype for the integral possibility of this time. It will be a Church that emphasizes the rightness of incarnation (i.e. the human body is good and sexually expressive). The belonging to

one’s place and land provides for a communal spirituality that can be expressed by “the prophetic role of the Christian.” Along with a strong sense of social justice and a commitment to reading, study and being theologically informed, doing one’s inner work of the soul can “develop our unused imagination, our neglected senses, to complement our rational minds.”

In summary Celtic spirituality is ascetical, mystical and visionary. The author invites the need for change, conversion and transformation in order to deeply express “what our humanity is about so that it truly reflects the image of God.” ■

by Timothy J. Joyce

180 pages

Published by Orbis Books (1998)

Available in Paperback US $21.00

O God, our Creator, You, who made us in Your image, give us the grace of inclusion in the heart of Your Church.

R: With one accord, we pray.

Jesus, our Saviour, You, who received the love of women and men, heal what divides us, and bless what unites us.

R: With one accord, we pray.

Holy Spirit, our Comforter, You, who guides this work, provide for us as we hold in hope Your will for the good of all.

R: With one accord, we pray.

Mary, mother of God, pray for us. St. Joseph, stay close to us. Divine Wisdom, enlighten us.

R: With one accord, we pray. Amen.

We welcome your comments and reactions and will consider sharing them in future editions or on our website.

Please send to editor@magdalacolloquy.org

If you haven’t already subscribed, you can do so at any time at no cost due to the generous support of the Basilian Fathers of the Congregation of St. Basil. Just visit our website www.magdalacolloquy.org where you can also read past issues of the journal and be informed of our ongoing activities and news items.

With One Accord journal is published in English and Italian and some past issues are also available in French. To access the other language editions please visit our website

With One Accord signature music for the Magdala interview composed by Dr. John Paul Farahat and performed by Emily VanBerkum and John Paul Farahat.

Lucinda M. Vardey—Editorial

1 Edith Stein Essays on Woman trans. Freda Mary Owen in the Collected Works of Edith Stein Volume Two (Washington, ICS Publications, 1987) pp. 93/94.

Michael Pirri—Expressing Common Faith and Worship

1 See Instruction on Admitting other Christians to Eucharistic Communion in the Catholic Church under Certain Circumstances (Rome, Secretariat for Promotion of the Unity of Christians, 1972).

2 Funk, Virgil C., 2019, “Shared Communion... Revisited.” in Worship 93 (January): 54–67, page 55.

3 Rausch, Thomas P., 1986, “Reception Past and Present.” in Theological Studies 47 (3): 497–508.

4 Ibid, 164

5 Cramer, Jared C., Percy Dearmer Revisited, Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2020, page 52.

Tania Brosnan—A Personal Journey with the Rosary and Holy Mary

1 Jim Cotter, Prayer at Day’s Dawning (Cairns Publications, 1998) p. 37.

Images used in this edition:

Cover: “St. Catherine of Siena” bronze sculpture 1998 by Elena Manganelli O.S.A. Used with permission.

Page 2 Detail of “St. Catherine of Siena” sculpture by Elena Manganelli O.S.A.

Page 5 “Three Destinies” (triptych) used by permission of the artist, Karen S. Purdy, copyright 2007. www. karenpurdy.com

Page 7 “The Head of the Virgin” in Three-Quarter View Facing Right drawing by Leonardo da Vinci (14521519).

Page 8 Detail from “The Rosary” by Beatrice Offor (1864-1920). Original painting in Bruce Castle Museum, London.

Page 10 Detail from “Portrait of Mary and William of Orange, 1641 by Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641).

Page 12 Detail from “The Visitation” by Jacob and/or Hans Strueb (1505).

Page 14 “Afternoon at Montecasale, Tuscany,” photo by John Dalla Costa.

This edition

Copyright © 2025 Saint Basil’s Catholic Parish, Toronto, Canada For editorial enquiries, please contact editor@magdalacolloquy.org ISSN 2563-7924

PUBLISHER

Morgan V. Rice CSB.

EDITOR

Lucinda M. Vardey

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Emily VanBerkum

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

Gregory Rupik

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

Michael Pirri

VIDEO EDITOR

Michael Pirri

CONSULTANT

John Dalla Costa

TRANSLATOR

Elena Buia Rutt (Italian)

ADMINISTRATOR

Margaret D’Elia