CONTENTS EDITORIAL

Lucinda M. Vardey

PRINCE OF PEACE: JESUS AND BEING NON-VIOLENT

Scott Lewis S.J.

BEING BEAUTIFUL: A CAUTIONARY TALE IN THE BIBLE

Kathleen MacInnis Kichline

REMAINING UNBROKEN: MARGARET OF CASTELLO

Lucinda M. Vardey

LIKE A NET CAST INTO THE SEA

Giulia Vannini O.S.A.

THE MAGDALA INTERVIEW

Gregory Rupik with Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz

THE POINT OF OUR BEING

Mary Jo Leddy

THE ADVENT OF A.I. AND ITS EFFECTS ON BEING HUMAN

John Dalla Costa

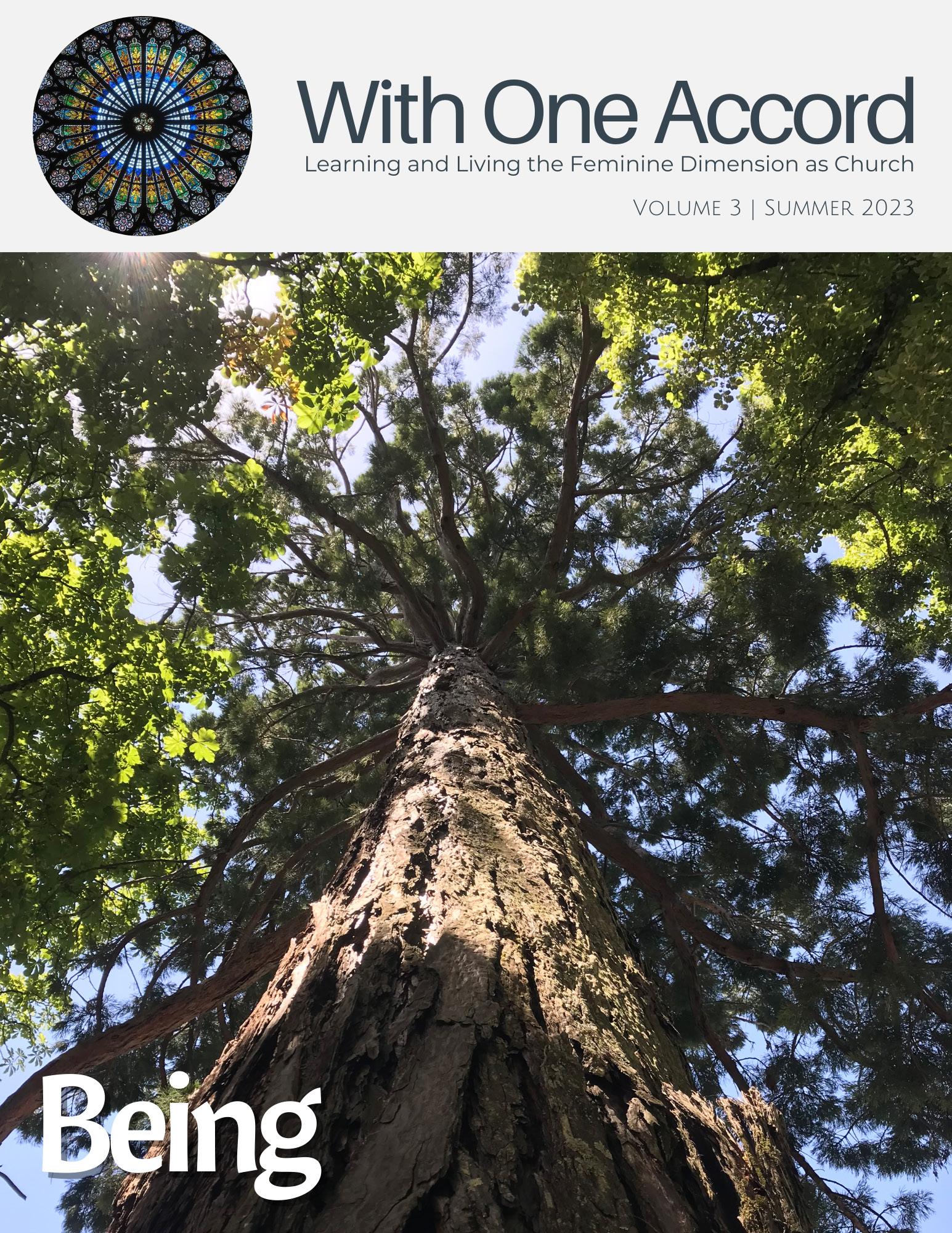

With One Accord Being Volume Three, Issue 3 Summer 2023

www.magdalacolloquy.org 1

The cover photograph for this issue speaks many words. It describes being held by that vast trunk (which must equally have deep roots) to grow towards the light and spread out its many branches. All the life-giving activities go on invisibly inside to make this happen which is certainly a metaphor for the spiritual life.

In this issue we explore the process of being securely rooted in God in and through differing choices, experiences and occurrences. Scott Lewis explains Jesus’ non-violence as a radical turn from the previously accepted “norm” of being in the Bible. Kathleen Kichline addresses the hazards of being physically beautiful through her portrayal of a few women recognized as such in Scripture. The story of recentlycanonized Margaret of Castello is a reminder that outward appearances are nearly always deceptive when it comes to knowing the truth of a person’s soul. And Giulia Vannini describes the course and everyday challenges of discipleship as a young and consecrated member of a monastic community.

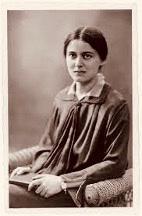

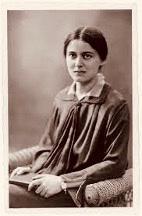

The Magdala interview concentrates on the particular discoveries in the study of “being” made by Edith Stein (St. Teresia Benedicta of the Cross) as an atheist philosopher turned Carmelite nun. Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz provides a compelling account of Stein’s search for meaning and the changes she underwent to come to her conclusions.

In her piece, “The Point of Our Being” (extracted from her book) Mary Jo Leddy shares why engaging in what we love brings meaning and purpose to our lives. And we conclude with the advancing development of Artificial Intelligence which brings with it numerous concerns on how we will be relating in the future. John Dalla Costa cites Pope Francis’ recommendations while addressing the imbalances occurring through these technological advancements.

As Jesus advised his disciples to ”be as wise as serpents and innocent as doves” (Matt. 10:16), we hope that this issue reflects the message of both.

Lucinda M.

www.magdalacolloquy.org

Editorial

Vardey Editor

“To be in God is Being.”

Marguerite Porete (The Mirror of Simple Souls).

2

Scott Lewis S.J. is Associate Professor Emeritus of Regis College at the University of Toronto and is currently on the faculty of Campion College in Regina, Saskatchewan. He served in the U.S. Navy for several years and entered the California Province of the Society of Jesus in 1979. After ordination in 1987, he studied Scripture in Rome, obtaining the Licentiate in Sacred Scripture from the Pontifical Biblical Institute and the Doctorate in Sacred Theology from the Gregorian University. He taught and worked for two years in Jerusalem before coming to Toronto in 1997. His expertise is in the Gospel of John, the Letters of Paul, the Bible and Religious Violence, and the history of exegesis. From 2008 to 2014 he was director of the Jesuit Spiritual Renewal Centre in Pickering, Ontario. In addition to his teaching duties, he presents weekly insights on the Sunday Gospel readings in the Catholic Register, lectures on Scripture and gives retreats both in Canada and internationally. Author of many books, his latest is “How Not to Read the Bible” (Novalis/Paulist Press, 2019).

Prince of Peace

Jesus and Being Non-Violent

Scott Lewis S.J.

“For a child has been born for us, a son given to us; authority rests upon his shoulders; and he is named Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (Isa. 9:6).

The prophet Isaiah has often been referred to as the fifth gospel, for the four evangelists draw on its beautiful and moving prophetic passages in telling the story of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. It was written by various individuals in the lineage of Isaiah over a period of at least a century, which was one that was characterized by terror, violence, destruction, and exile. The world was as scary a place then as it is now. The prophetic passages that envision redemption at the hands of a saviour-like figure, followed by peace and prosperity, were intended to give hope and comfort to the people of Israel in the late 7th to late 6th centuries BCE. Israel had been attacked first by the Assyrian killing machine and then the resurgent Babylonian empire, ending with the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in 586 BCE. The prophecies were intended for those living through this experience and the subsequent exile in Babylon. But the meaning of biblical texts, especially prophetic texts, is never exhausted by one interpretation—they have a second life and beyond. The authors of the New Testament followed midrashic practice by re-appropriating these texts to depict the life, mission, and death of Jesus. The primary texts were those portraying an enigmatic figure we call the “Suffering Servant” (Isaiah chapters 52 & 53). This unnamed martyr stands silent and unresisting before his tormentors. The title ‘Prince of Peace’ (Isaiah 9:6) is the title associated with Jesus that resonates with many people, and it has been expressed in music,

www.magdalacolloquy.org 3

poetry, and art. But, as we will see, Jesus is a different sort of prince.

This is where we run into difficulty, for the New Testament portrayal of Jesus is not without contradiction and ambiguity. Jesus insists that he has not come to bring peace but the sword (Matthew 10:34-36). He rages at the Pharisees and portrays them in the darkest of terms (Matthew chapter 23). He kicks over the tables of the moneychangers in the temple and drives them out with a whip (John 2:13-17). Finally, there is the chilling image of Jesus as the ruthless commanderin-chief of the divine army calmly surveying the slaughtered enemies of God in the Book of Revelation (Rev 18). The more militant and violent depictions of Jesus enjoy favour with more fundamentalist streams of Christianity, especially among racist or other extremist groups.

The New Testament books were written by several authors in various genres and reflect the tensions and struggles of the time in which they were written. Scholars agree that not all the words attributed to Jesus were actually spoken by him but were products of the early church. The core message and life of Jesus is overlaid with the residue of doctrinal disputes, Christian-Jewish rivalry, and apocalyptic fervour.

A DIVINE PATTERN

To understand the non-violent nature of Jesus it is necessary to focus on the heart and essential core of the portrayal of Jesus in the New Testament. The point of departure should be the Beatitudes in Matthew chapter 5 and the extended discourse in the succeeding chapters 6 and 7. They describe what a person should be rather than what one should do—it is a divine pattern for the fully spiritualized human person in harmony with the divine source.

The Beatitudes are variations on the themes of humility and compassion. Humility should be understood not as passive submission to the demands and whims of others, but as acting out of a heart in harmony with God rather than the ego and its selfish needs. The poor and the meek are declared ‘blessed’ (makarios). The poor are not necessarily those without money but the powerless. This reflects the Old Testament characterization of the anawim—the poor who are faithful to God in all circumstances and who rely totally on divine mercy and strength. Meek is not a positive word in our lexicon, for it denotes passivity and lack of courage. But meek is a translation of praus, which is best translated as gentle and non-violent. The list goes on: those who have the compassion and emotional maturity to mourn for the plight of the people and the nation; the pure in heart— those whose hearts are not scattered and divided but focussed relentlessly on divine principles and values. Mercy is another name for God; to be merciful is to manifest God to others. Peacemakers are those who engage in the frustrating and exhausting process of working for peace rather than mouthing platitudes. Finally, blessed are those who patiently, and with Christ-like forbearance, endure rejection and abuse because of living by these principles and who do not return evil for evil.

Jesus then raises the bar—it is not enough to refrain from striking or killing someone, we must eliminate even hateful or violent thoughts. The thought is the parent of the deed. The same applies for words, that have the power to build up and heal or injure, kill, and destroy. This is most evident in our polarized and hate-filled world. Both thoughts and words are things and have power for good or evil.

This extended discourse contains one of the most difficult—and ignored—teachings

www.magdalacolloquy.org

4

in the Christian tradition (Matthew 5:38-42). When slapped, turn the other cheek. Resist not the evil doer; if anyone forces you to go one mile, go two. Lend to all who ask and hold nothing back. It sounds like a recipe for becoming a slave or a doormat. New Testament scholar Walter Wink illuminated these teachings in the culture in which they were proclaimed. What is involved is renunciation of retaliation and revenge, and in a patriarchal honour-shame based culture, this was no easy task. Jesus manifested what would have been considered feminine traits in the culture of the ancient Mediterranean. Jesus calls for the victim to seize control of the situation. Turn the other cheek in defiance and dignity instead of cowering and cringing. Get the Roman soldier who forced you to go the statutory one mile of service in trouble by continuing on for a second. Shame publicly the creditor who literally takes the clothes from off your back. Jesus continually uncouples from the culture around him, refashioning people of a different order in the process. Jesus is not a pacifist and does not ask us to be. He is non-violent—it is far more effective and its results longer lasting.

THE PRIMACY OF LOVE

Love serves as a golden thread that runs throughout the entire New Testament—all four of the gospels, the letters of Paul, and the letters of John. Luke and Matthew are uncompromising: it is not enough to love those who love you. In order to be a child of the Most High God one must love without distinction or conditions, even one’s persecutors and enemies. God gives equally to the good and wicked, the grateful and ungrateful. It is clear that Jesus is departing from human cultures and societies, for this is not the usual human response. Here it is a commandment and a new direction. In John’s gospel, he commands his followers to love one another as he has loved them and

to lay down their lives for one another. Divine love is limitless and all-encompassing and ours should be too.

The commitment of Jesus to the principles of the kingdom are most evident in his arrest and death. He tells the cynical Roman procurator that if his kingdom were of this world—if he played according to the world’s rules—his followers would be fighting on his behalf. In Matthew 26:52, he orders one of his hotblooded apostles to put his sword away— those who resort to violence will perish by it. And finally, following his modelling of the Suffering Servant of Second Isaiah, he stands mute before his accusers and does not resist.

In crafting this New Testament image of a non-violent Jesus, it is not a matter of cherrypicking agreeable passages. It is necessary to look for a reasonably consistent portrayal of Jesus, omitting outliers such as Revelation (which was viewed with suspicion from the beginning). He is portrayed as embodying love and non-violence in the gospels. The letters of Paul and some of the pastoral epistles repeat his insistence on the primacy of love.

The non-violent teachings taught and manifested by Jesus have seldom really been put into practice. They are thought to be utopian and unrealistic. But those who guide their lives by these principles have been able to do wonderful things and change the world. Francis of Assisi, Mahatma Gandhi, Leo Tolstoy, Martin Luther King, Mother Teresa, Dorothy Day, and Hildegard of Bingen are just some examples.

Teilhard de Chardin (The Eternal Feminine).

www.magdalacolloquy.org 5

“Only love has the power to move being.”

Pierre

Kathleen MacInnis Kichline holds a Masters of Divinity from Seattle University where she also served as adjunct faculty teaching on spiritual retreats. Currently retired from Seattle, she continues active ministry in retreats and presentations both online and in person. She is the author of “Sisters in Scripture: Exploring the Relationships of Biblical Women” (Paulist Press, 2009) and “Never on Sunday: A look at the Women NOT in the Lectionary” soon to be published in Spanish. Her most recent book is “Why These Women: Four Stories You Need to Read Before You Read the Story of Jesus” www. sistersinscripture.com.

Being Beautiful A Cautionary Tale in the Bible

Kathleen MacInnis Kichline

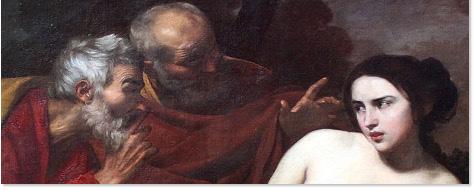

“The woman was very beautiful” (2 Sam. 11:2). This is all the Bible ever tells us about Bathsheba, aside from being identified as “the wife of Uriah the Hittite” (2 Sam. 11:4). Everything that happens to Bathsheba in the biblical narrative proceeds from that initial premise. Whatever else we might think we know about her, we gather from the way she is remembered and referred to outside the scriptures—and those descriptions are many: “tempting, seductive, adulterous, scheming…” Though none of these find support in the text itself, the impression remains.

I recently led a retreat on my book, Why These Women: Four Stories You Need to Read Before You Read the Story of Jesus. When we discussed Bathsheba, one of the women shared that when she was quite young, her grandmother told her that Bathsheba’s sin was being beautiful. This woman internalized that message and grew up not wanting to see herself, or have others see her, as beautiful, an inhibition that had long-lasting and painful consequences. What an incredible message to give a young girl.

Yet, I know it to be true. I have a similar, more subtle memory and message from when I was ten years old. I was walking with my grandmother when we came to a corner. As we waited for the light to change, another woman, about my grandmother’s age, remarked to her about me, “What a pretty little girl! Why, I bet she’s exactly what Grace Kelly looked like at her age.” My grandmother turned on her heel and upbraided the other woman saying, “What are you doing saying such things in her hearing? You will make her vain!”

The grandmothers may have been on to something. Being called beautiful is, perhaps, something to avoid, especially in the Bible. It can bring all sorts of unwanted attention and it starts early in the story. Because Sarah is beautiful and Abraham fears for his life, he passes her off as his sister and she becomes twice part of a harem. A generation later, Isaac does the same to Rebekah. Much later in the story of Israel, the beautiful Esther is torn her from her home and thrust into the harem of an evil king to satiate his ego, lust, and consuming power. David’s son, Absalom, lusts after the beauty of his sister, Tamar; she is raped and discarded. In the Book of Daniel, the beautiful and virtuous young Hebrew wife, Susanna, is,

www.magdalacolloquy.org

6

like Bathsheba, spied bathing and lecherous voyeurs force her to choose between blackmail or submitting to their advances.

As a kind of biblical morality tale, avoiding beauty is a cautionary as strong and numerous as the medieval tales of the big, bad wolf. Some women, like Rachel, are loved for their beauty, the only woman in the Bible to be kissed by a man. And David was attracted to Abigail for her intelligence and beauty (cf.1 Sam. 25:3). But these are minor notes within the larger problematic text.

Proverbs advises “Charm is deceitful, and beauty is vain, but a woman who fears the Lord, she shall be praised” (Prov. 31:31). This sets up an either-or dichotomy that has not served women well down the years. In today’s parlance, we use phrases like “body positivity” and recognize the importance of women feeling good about their bodies and appearance, a value we cherish for girls and women of all ages. As aware as we now are, it is dismaying to discover that our own sacred texts can undermine these efforts. So what are we to do with these disturbing, not-so-subtle messages?

The Song of Songs offers language that is a surprising correction to this pattern.The word “beautiful” is employed numerous times in its short eight chapters.“I am black and beautiful” (1:5), “How beautiful you are my love, how very beautiful” (4.1), “You are altogether beautiful” (4:7), “Most beautiful among women” (5:9), “How beautiful are your feet” (7:1). To read it is to exult in the power of beauty to arouse.

But, the most powerful corrective within our sacred Scripture, is the life of Jesus Christ. There is nothing in the life, words, or example of Jesus that was anything less than respectful and empowering of women. Women were his confidants and supporters. He called them by name, listened to them, entrusted them with his mission and held them up for example.

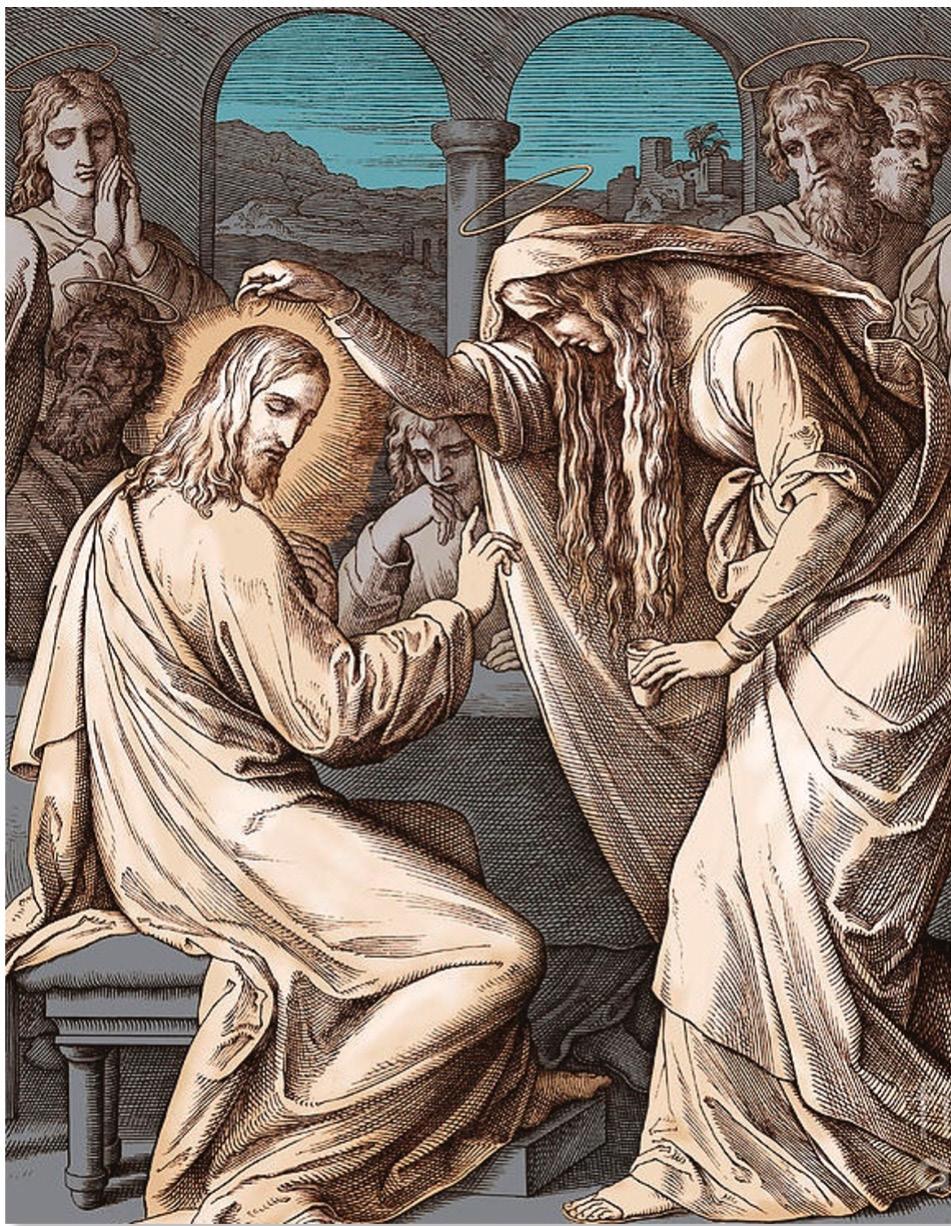

In the story of Jesus’ anointing as told by both Mark and Matthew, the story takes place in the home of Simon the leper. When the woman with the alabaster jar breaks it open and uses “very costly” (Mk 14:3) nard to anoint Jesus’ head, onlookers berate her extravagance.

www.magdalacolloquy.org 7

But Jesus responds, “Let her alone” (Mk 14:6). In Jesus’ protective words, I hear echoes of Nathan’s parable about the little lamb who is Bathsheba, blameless in God’s sight (ref.2 Samuel 12:4).

“She has done what she could” (Mk 14:8). By receiving and praising her kindness, Jesus draws attention to all the women in scripture, including those women who suffered for the fact of their beauty, women whose lives were so much more than their appearance.

With his words, “What she has done will be told in remembrance of her”(Mk 14:9), Jesus predicts a future when she and other women will be honoured for what they have done. He proclaims what is meant to be, though has not yet happened, a time when the stories of women will be remembered and searched out for the lessons they hold, a time when their names will spring readily to our lips and not be forgotten.

Such a hoped-for time can begin by seizing the opportunity whenever the lectionary provides us with a text that focuses on women. An occasion to proclaim and explore such stories, particularly within the context of liturgy, has the power to speak to every woman and young girl, calling her from the periphery into the central action of the Gospel. The simple act of attending to women in scripture particularly touches the young in ways far beyond the actual words spoken. That effect is further magnified when a woman is part of the proclamation or its interpretation. It is no less than a reenactment of Luke 13:10-17, when in the middle of worship, Jesus calls forward the bent woman to restore her to health and dignity, a story that, alas, is never proclaimed on Sunday as it is not included in the lectionary.

www.magdalacolloquy.org

8

Remaining Unbroken: Margaret of Castello

Lucinda M. Vardey

Lucinda M. Vardey

Lucinda M. Vardey is the editor of With One Accord. For more on her background please visit our website.

There can be little doubt that a life of holiness is infused with much suffering. From reading about the saints we learn of the ways they bore their crosses. They all bear witness to the constancy, courage, faith and love Jesus exemplified.

The story of Margaret of Castello has touched many as one of the greatest examples of how attitude and actions similar to Christ’s can be expressed. She lived in the 13th & 14 th centuries, a transitioning period between the age of chivalry and early modernism. Most saints underwent conversions at some point in their lives. Margaret didn’t. Her journey was a seamless one from the moment she was born to her death at the age of thirty-three.

As those who bear physical limitations are able to teach us compassion towards people unable to fend for themselves, Margaret received none. Her radical path of remaining unbroken by her circumstances and by the behaviour of others towards her, is truly unique.

She was the first child born in 1287 to noble parents in the Marches, Italy. Famous for his military prowess and his wealth as a landowner, her father anticipated celebrating the birth of a son. But only silence was the response in their castle when a deformed, blind baby girl arrived. After recovering from

their shock, they placed her in the care of a maid in the castle with strict instructions to keep the baby’s existence a secret from everyone outside their immediate staff. The local priest, however, demanded she be baptized and the maid took the baby to the local church and gave her the name “Margherita” which means “pearl.”

As a toddler, Margaret, who was dwarfed with one leg shorter than the other, found her way around the castle on crutches, with much friendliness and sociability. Yet she was always warned to stay clear of her parents and any visiting guests. After an incident when she was discovered by a woman visitor, her parents, ensuring that this wouldn’t happen again, placed 6-year-old Margaret in a small cell beside the local parish church in the mountains. There she could feel the altar nearby through a hole in a wall, which served as a means of passing food and drink to her. Her parents intended to leave her in this small prison for the rest of her life.

Apart from the maid, her only other visitor was the parish chaplain who took it on himself to educate her. He found her mind to be “luminous” and her patient understanding of life and its problems truly remarkable. Margaret was led to accept not only her physical afflictions, but her incarceration as a special gift from God. Along with enduring the intense cold and heat of the seasons, she never complained and asked for nothing.

A POSSIBLE MIRACLE

Twelve years later, in 1305, after a French cardinal was elected Pope Clement V and

www.magdalacolloquy.org 9

moved from Rome to France, many Italian papal states and republics were made vulnerable to attack. Wary of her being discovered by intruding soldiers, her father moved Margaret to the family palace in the nearby town.

She was delighted to be with her parents as they escorted her by carriage, but any hope of reconciliation or relationship was dashed after they placed her in an underground vault, furnished only with a simple bench and table. Instructed to remain silent, she could only speak to the servant who brought her daily meals. Here Margaret was to undergo more intense suffering of solitude without the visiting priest and participation in the Mass and the Eucharist.

After a peace treaty was signed with her father, her parents learned from some German pilgrims about cures of the disabled and sick at a tomb of a Franciscan brother called Fra Giacomo in nearby Cittå di Castello in Umbria. Overjoyed, Margaret, now nearly 20 years old, was escorted early one morning by her parents to the site. The whole family attended early morning Mass and prayed for a miracle cure for her.

When no visible signs of change occurred, her parents left her at the church, with a promise that they’d return for her in the late afternoon, which they never did. They abandoned her and left town. The warden, locking up the church for the night, directed this lone, diminutive figure outside. Cold and hungry, Margaret spent the night on the church steps in a town she didn’t know.

Befriended by a couple of beggars the following morning, she learned how to locate the fountains for drinking and washing and where to shelter for the night. Close to Christmas, these friends found her covered in snow in a doorway, so invited her to sleep with them in a stable. This experience had profound spiritual significance for Margaret, as she took it as a sign that she was no longer the daughter of nobility, no longer orphaned from her family, but a daughter of God. God was now her only parent; Jesus, Mary and Joseph at Bethlehem, her one and only family.

MOVEMENTS OF THE SPIRIT

Margaret’s joyful and loving disposition caused suspicion among the townsfolk. They asked, what could she possibly be joyful about in her state? Over time, however, she won their admiration and respect and was invited into their homes. Any act of generosity extended to her was rewarded one hundredfold: families experienced extraordinary healings, peaceful outcomes to feuds, and the sick were cured.

Margaret’s faith, zeal and devotion to God led her to be recommended for convent life but her entry was to cause unrest within the community because of her disciplined adherence to the religious Rule mostly ignored by the other sisters. Margaret’s strict behaviour disrupted the nuns so much, she was asked to leave.

Life on the streets was not the same as before. Cast out of the convent, Margaret underwent ridicule, and shameful gossip about her began to spread. She never answered or defended

www.magdalacolloquy.org

10

the accusations against her, only expressed remorse at disappointing the nuns.

Following a retreat with local Dominican friars, Margaret joined the Third Order of Penance, and entered a life of ceaseless prayer and loving service to others. She visited the sick and the dying and brought much comfort and healing to those in need.

She was given a job of teaching religion to the children of a rich family and moved into a garret on the grounds of their palace. Although unsafe for women, Margaret, began also to visit prisoners.

She foretold her impending death in 1320 and died with a smile on her lips. As they took her body to its tomb, a young couple, whose child could not walk due to an extreme curvature of the spine, pushed their daughter towards Margaret’s body. Witnesses claimed that her left arm rose from its shroud, reached towards the child and cured her.

Patron of the physically challenged, Margaret was beatified on November 18, 1609, and canonized by Pope Francis on April 24, 2021.

St. Margaret of Castello is loved and remembered to this day. Her uncorrupted body lies encased under the high altar of the Dominican Churcn in Città di Castello. People come to light a candle and say a prayer.

A child unwanted, unloved and rejected let nothing that happened to her be of concern. She is an example of acceptance to the purest degree. Her strong interiority disallowed outside circumstances to affect the innocence of who she was at her core. A great soul, a woman of mercy and lover of God, her short life exemplified the perfect embodiment of Jesus’ Beatitudes.

Pope Francis (Audience 5 March 2023).

11

www.magdalacolloquy.org

“Wherever women are present the Church is changed and directed forward.”

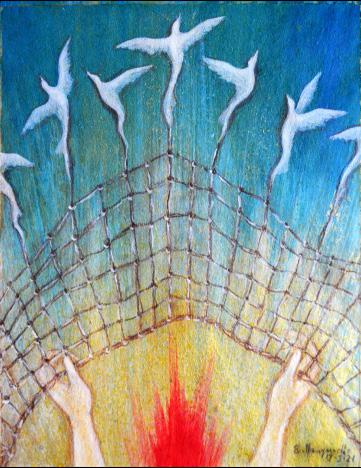

Giulia Vannini an Augustinian nun, has lived for the last nine years at the Augustinian monastic community of Pennabilli (Rimini, Italy), along with 13 other sisters, in a life of prayer, study, work and hospitality and sharing with anyone who visits the monastery. Born 1992 in Florence, she entered the same monastery in 2014 and on June 25, 2022, together with Sr. Chiara, her companion on the journey, she made her Solemn Profession. During her initial formation years she pursued a Baccalaureate in Theology together with other sisters in the community, which was completed in 2020 at the Augustinianum Patristic Institute.

Like a Net Cast into the Sea

Giulia Vannin O.S.A.

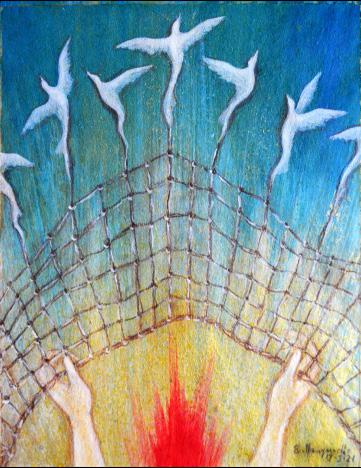

“The kingdom of heaven is like a net cast into the sea, gathering fish of every kind” (Matt. 13:47).

These words from Jesus provide a perfect image of my life with God and my monastic journey. In the Old Testament the word “net” has a negative connotation that describes stumbling and falling or a set of evil, dangerous things—”The arrogant have hidden a trap for me and with cords they have spread a net, along the road they have set snares for me” (Ps. 140:5): “The desires of the wicket are a net of evils” (Prov. 12.12). “Net” is also a metaphor used by God to indicate God’s strong and decisive action towards rebellious people: “I will spread my net over him, and he will be caught in my snare” (Ezekiel 17:20). However, in the Gospel, “net” sheds all negativity. It becomes instead a positive metaphor for the Kingdom, portraying the environment and everyday reality in which Jesus lived. Fishermen formed part of that environment.

How do these quotes speak to me as a young Augustinian nun? As I continue monastic life, I often think about the nets mentioned in the Gospel.

“Passing along the Sea of Galilee, Jesus saw Simon and Andrew, Simon’s brother, casting a net into the sea—for they were fishermen. He said to them, ‘Come follow me and I will make you fish for people.’ And immediately they left their nets and followed him” (Mark 1:16-17).

My call to a life in the monastery was similar to the gospel accounts of Jesus’ call to the first disciples. Mine, too, was a leaving of nets to follow a desire stronger than all others, apprehending a unique love for my life. What I have found is that there are innumerable leaving of nets on my journey. Whenever a choice has to be made—and there are many along the way requiring me to leave something behind—I have to continually throw nets overboard. This throwing requires me not to keep them for myself, not to hold on, or have proprietary over them.These nets are not just for leaving but throwing. To throw is a constructive leaving, a leaving that bears fruit. Luke emphasizes this in his account of the calling of the disciples: ”Jesus said to Simon, ‘Put out to sea and cast your nets for a catch.’ Simon replied, ‘Master, we have toiled all night and caught nothing; yet if you say so, I will let down the nets” (Luke 5:4-5).

This casting of nets within my own life is an experience that changes over time, yet it still

www.magdalacolloquy.org

12

draws from the same source. The Augustinian Rule (1:3) says “Claim nothing as your personal possession; on the contrary, let everything be common among you,” and “Let the common good come before the individual good, and not vice versa” (ibid 5:2). It has to do with trying to renounce everything that is private and exclusive: in things, relationships, thoughts, feelings and in loving. This way of life for St. Augustine is the proper mode for living poverty, chastity and obedience. It requires not only renunciation, but sharing.

Giving up all that is personally exclusive, and being occupied instead by what is common, is not an easy experience, nor is it immediate. Yet it contains within itself the promise of a life of abundance, which is discovered only after casting the nets.

“When they had done this, they caught so many fish that their nets were beginning to break. So they beckoned to their partners in the other boat to come and help them. And they came and filled both boats, so that they began to sink” (Luke 5:6-7).

I feel that my life as a young nun has to do with casting nets and choosing each day not to pull them back up. That is, to be in an attitude of casting nets, of nets at sea, on trusting that these will not break, or be lost, or broken, even when it seems that life is asking too much of me, that I have too little to give, or even that I cannot sustain all that comes my way. For it is He who, as soon as I choose to throw them away, keeps them with me and sustains them: “When they came to shore, they saw a charcoal fire there with fish on it, and bread. Jesus said to them ‘Bring some of the fish that you have just caught.’ So Simon Peter went aboard and hauled the net ashore full of a hundred and fifty-three large fish, and though there were so many, the net was not torn” (John 21:9-11).

The net is mine: it is my freedom. Every day I must choose whether to trust or not, whether to give myself or not, but it has to be first to Him, the promise of God for me and for all. Only within this promise of life—unique to each person—can we too dare to leave and cast our little net.

I feel that the promise of God for my life today is contained in Matthew’s Gospel verse, “The kingdom of heaven is like a net cast into the sea, gathering fish of every kind” (Matt 13:47).

How do I hold together in one specific form of life all that I am, all that I feel, all that I desire? The restlessness caused by these questions is preceded by a Love that can hold it all together. This is the first net cast into the sea of my life: His. A net, a Love that holds together every kind of fish, every part of me; that promises to gather everything so that nothing is lost.

www.magdalacolloquy.org 13

14

www.magdalacolloquy.org

The Magdala Interview

Greg Rupik with Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz

Greg Rupik is a contributing editor of With One Accord. For more information on his background, please visit our website.

Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz is a philosopher and theologian who has published in the fields of cultural anthropology, feminism and gender, philosophy of religion (as well as philosophy of the 19 th and 20 th centuries) and in a branch of philosophy known as phenomenology. Her scholarship includes a special focus on theologian Romano Guardini and Edith Stein (Saint Teresia Benedicta of the Cross). For the last 12 years she has been Head of the Institute for European Philosophy and Religion at Hochschule Benedikt XVI in Heiligenkreuz, Vienna, Austria. Most recently, she was awarded the 2021 Ratzinger Prize for Theology presented by Pope Francis in Rome.

www.magdalacolloquy.org 15

“The feminine operates on the level of the structure of being: it is not “the Word” but the womb of creation.”

Paul Evdokimov (Woman and the Salvation of the World).

Click to view the interview

Mary Jo Leddy is a writer, speaker, theologian and social activist. She was the founding editor of the newspaper, Catholic New Times. After some years as a member of the Sisters of Our Lady of Sion, she began working and living with refugees and founded a house of welcome which later became the Romero House community. She has taught in many theological schools receiving several honorary doctorates. She is a Senior Fellow at Massey College, University of Toronto, and a board member of PEN Canada and Massey College. A recipient of the Human Relations Award of the Canadian Council of Christians and Jews (l987), the Ontario Citizenship Award (l993) and the Order of Canada (l996), her many books include “Say to the Darkness We Beg to Differ” (Lester & Orpen Dennys, l990); “Reweaving Religious Life: Beyond the Liberal Model” (Twenty Third Publications, 1990); “At the Border Called Hope: Where Refugees are Neighbours” (HarperCollins, 1997) and”The Other Face of God: When the Stranger Calls Us Home” (Orbis 2011). The following is an excerpt from “Radical Gratitude” by Mary Jo Leddy (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2002).Used with kind permission of Orbis Books. For more information search Mary Jo Leddy on www.novalis.ca.

The Point of Our Being

www.magdalacolloquy.org

16

Mary Jo Leddy

You are the Point of all Being. Every tree stretches up to You. Each plant reaches down to You. All the roads go on to You. The many waters run toward the vastness of Your love. The air breathes in and unto You. Every heart wants to turn to You.

How unhappy we are when we miss the Point of all Being. How blessed are we when we follow our longing and leaning into Your direction.

LIFELINES FROM THE PAST

In the past, the underlying narrative structure of our lives was supplied by our culture, by our country, or by religion, sometimes even by sports. The modern myth of progress carried our lives forward by the sheer force of its optimism even since the founding of America. The American spirit was essentially expansive and, at its best, extremely generous. The founding vision of the republic and the ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness carried the nation forward as it grew. The mainline religions preached a biblical story that revealed the origin and the destiny of the human person.

These lifelines still exist, but they no longer seem strong enough to pull us out of the cultural currents of consumerism. The events of the twentieth century, simultaneously barbaric and eminently modern, have raised doubts about the myth of progress in a way that no philosophical critique could do. The founding ideals of the republic are becoming lost in the imperatives of empire. To the extent that the mainline religions tied their message to the dominant myths of the culture, their voices too have become uncertain and lost.

A simple yet sure sign of the loss of spirit and meaning is fatigue. When I reflect on the times I have worked because I believed in what I was doing and had a conviction about its purpose, I realize that I could work for hours and wake refreshed. It is when I was not convinced of the purpose of what I was doing that I became easily tired, took long breaks, began to plan holidays, took courses on how to manage my time and on how to set boundaries.

I recall a conversation with a friend of mine who was fretting about caring for her young son. She is very busy, as is her husband. They get up, get the child ready for day care, go to work, come home, make supper, get the child ready for bed, prepare for work the next day. “Sometimes I feel my life is just a collection of pieces,” she said. The conversation would have been usual enough except for the fact that she went on to say: “But what I love to do, later in the evening before I go to bed, is to go into my son’s room and just look at him. I just love looking at him. And then all the fatigue falls away and I know the point of it all.”

The point of our lives concentrates all that we are and all that we do and fills us with the energy of purpose. That point becomes the line that gathers unto itself all the other points of our lives.This may not mean our lives are progressing or even getting better, but it does mean that we know why we are here and what we are for.

JESUS AND THE POINT OF HIS BEING

Those of us who are Christians can also remember the example of Someone who lived with a sense of meaning and purpose in the most chaotic and oppressive time. We have only to recall that Jesus lived with God as the point of his being. Again and again, he told his disciples that he had come from God and was going to God. He knew who he was, that his deepest identity lay in the mystery that he was born of God. And he knew that he was for God, that he had come to announce the great dream of God, the dream of the reign of God and the great economy of grace.

www.magdalacolloquy.org 17

This was the meaning and purpose of his life. It was his passion. His affirmation of the point of his life was profoundly based on his gratitude for being born of God. This deep connection between gratitude and trust in the future has been simply expressed by Dag Hammarskjold: “For all that has been, Thanks; for all that shall be, Yes.”

Jesus has left us with this vision, a vision worthy enough to summon every aspect of our being and the whole of our lives. Yet, the vision is not a blueprint. It is not a detailed plan of what we are to do and how we are to do it. It has been left to us to fill in the blanks, as it were.

The great dream of God for the world is not a concrete plan, but it is compelling. It gives us a sense of how the story of the world and of how our own story will end. It will end as it began—in goodness. It makes all the difference in the world to believe that the dream of God for the world is going to happen.

I learned this from a very holy older woman as she lay dying. Her name was Kieran Flynn. She was a Sister of Mercy who was widely respected for her wisdom about the spiritual life, about life.

Kieran had been diagnosed with multiple melanomas—a particularly virulent and painful form of cancer. She had been taken to Massachusetts General Hospital toward the end of her illness and had been given multiple doses of morphine to ease the pain. Rather quickly she went into complete unconsciousness. What impressed those of us who had gathered around her was that she was almost constantly saying short prayers in a rhythmic, mantralike fashion: You are the way, You are the truth, You are the life, bless the poor, have mercy. The prayers could not have come from a level of consciousness but had to have come from some deeper level of the unconscious and the imagination. At the deepest level of her being, she had been shaped by the word of God. She was breathing from God and for God and with God. She had become a prayer.

Then one afternoon, as three of us were sitting by her bed in the hospital room, it was as if she awoke but she could not have been conscious. In a very clear voice she said: “I had a dream. I dreamt that all the men and women were all seated around a round table, all equal, all free. It will take a thousand years but it doesn’t really matter because it’s going to happen.”

And then she slipped back into wherever she had come from. I heard this as the dream of God or what has traditionally been called the vision of the reign of God or the kingdom of God. It is a dream of justice, peace, and love.

Kieran’s dream was part of God’s great dream for the world. We, each and every one of us, are part of this great dream. Our smaller dreams and hopes are part of God’s point for the world. It is sometimes difficult to hear that “it will take a thousand years,” but it makes all the difference in the world whether we believe in the power of this dream to prevail. It is this dream that has the power to sustain us in struggle and the power to endure through the collapse of our particular hopes.

www.magdalacolloquy.org

18

The Advent of A.I. and its Effects on Being Human

John Dalla Costa

John Dalla Costa is an ethicist, theologian, and author of five books. For more on his background please visit our website.

The uncertainties unleashed by artificial intelligence bring anxieties as deep and complex as the algorithms that drive machine learning. Innovations always cause what economists call “creative destruction.” However—as but one example—artificial

intelligence is so powerful that business forecasters believe that it will displace 300 million jobs in the not-too-distant future.1 Advocates promise all-encompassing techutopia without answering the vexing moral dilemmas that accompany such destruction. A decade ago, the physicist Stephen Hawking, warned that A.I. posed “an existential threat to humanity.”2 Alarm bells are now more shrill as technology migrated from developmentlabs to real-life applications.

www.magdalacolloquy.org 19

In May, 2023, over 350 technologists, A.I. pioneers, scientists, academics, and industry leaders published a missive pleading with governments around the world to urgently regulate the development, spread and use of artificial intelligence. Those immersed in the intestinal workings of A.I. now want those outside the industry to see what they see: A.I. has the same potential as an “extinction event” as nuclear weapons or climate change.3

Pope Francis has addressed A.I. numerous times. He acknowledges the immense possibilities from this technology, while insisting that A.I. be used ethically for the human and common good. In March 2023, he went further, summoning the lived experience of women to fully engage the “momentous changes” and “wounds of our time.” The Pope notes that artificial intelligence raises “new and unpredictable dynamics of power.” Women’s perspective and counsel is crucial here, “for they are uniquely able, in their way of acting, to synthesize three different languages: the language of the mind, the language of the heart and the language of the hands. All at once. A mature woman thinks what she feels and does; she feels what she does and thinks; she does what she feels and thinks. All in harmony.”4

This interpretation from harmony Pope Francis describes is both subversive and transformative. A.I. is based on the language of numbers. Infinitely complex, these digits are forever binary. They can be combined and compounded for computation, but miss the most basic capability for relationship because of the abyss between each digit. A.I. developers are trying to program black-boxes and robots to express empathy, care and other human emotions. While machine-sentience may or may not come to fruition, a heart of numbers will always be much more akin to the self-isolating “heart of stone” than the “heart of flesh” beckoned by God’s prophets (e.g. Ezekiel 36:26).

THE IMAGE AND LIKENESS

Our current human landscape, eroded and corroded as it has been by social media, presages life in a virtual reality premised on a “heart of numbers.” Machines and technology can connect us in smart ways, but the underlying algorithms respect neither privacy nor truth. The numbers driving links and likes has already the capability to trap people into an addictive dependence while stimulating suspicion and despair that has proven to result in depression. Personal capacities for friendship are impaired, and relationships become more and more utilitarian.

The algorithms for machine learning draw on all the data points and information available on the internet— the books, articles, blogs, tweets and posts. For being in the “image and likeness of man,” this technology therefore cannot escape human foibles, faults and failures, which will only amplify mistruths, demeaning marketing, and hateful ideologies that have made their home on-line. www.magdalacolloquy.org

20

A.I. is explicitly in the image and likeness of man—not woman—in two ways. First, those programming A.I., those who lead the technology companies, and even those who have raised the shrillest warnings, are almost exclusively men. Distortions or biases from this gender imbalance cannot but be concerning. Perhaps more so is that the development and future of A.I. is in the hands of corporations. Therefore the “image and likeness” being imprinted on A.I.’s algorithms, is not human but the once-removed artifice homo economicus—not the incarnate creature of flesh and blood, body, mind and spirit, but “the economic man… characterized by the infinite ability to make rational decisions…to compete and maximize profits.” 5

The three languages of heart, mind and hands Pope Francis identifies, invoke the Incarnation as counter-point. The language of intelligence includes wisdom as well as knowledge and understanding—the gifts of the Holy Spirit by which the power from new knowledge is refashioned by moral priorities for the greater and common good. The language of the heart, source of care, concern and of all practical ethics, fills in the gap between numbers by heeding the human heart and vulnerability of others. The language of hands expresses wisdom and heart in practical relationship, in touch, in attending to another’s wounds, in serving another’s needs, in helping build shared dreams.

Pope Francis does not exclude men from this nexus of three languages, for “this synthesis is distinctively human.” The point he makes is that the “genius of women” is derived, in part, from having experienced exclusion and diminishment—from living in the wounds of a dehumanizing world; and having assumed the bulk of the responsibility to care for those suffering. With A.I. now casting a shadow over all human beings, “women can teach men to do the same” as “it is women who first achieve this harmony of expression, of thinking with the three languages.”

Created in the image and likeness of God, the task for human beings is not to make the technology more human, but to become more human ourselves, learning the language skills for relationship. In doing so, our ingenuity and the tools we create shall indeed serve with heartfelt care the God-given human dignity of all our sisters and brothers.

Works Cited

1 Jack Kelly, “Goldman Sachs Predicts 300 million Jobs Will Be Lost or Degraded By Artificial Intelligence,” Forbes Magazine, March 31, 2023, https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2023/03/31/goldman-sachspredicts-300-million-jobs-will-be-lost-or-degraded-by-artificial-intelligence/.

2 Rory Cellen-Jones, “Stephen Hawking warns artificial intelligence could end mankind,” BBC News (Tech), December 4, 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-30290540.

3 Kevin Roose,”AI Poses ‘Risk of Extinction,’ Industry Leaders Warn,” New York Times, May 23, 2023, https:// www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/technology/ai-threat-warning.html.

4 Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to the Members of the Foundation Centesimus Annus Pro Pontifice and The Strategic Alliance of Catholic Universities,” Vatican City, March 11, 2023, https://www.vatican.va/content/ francesco/en/speeches/2023/march/documents/20230311-incontro.html.

5 James Chen, “What is Homo Economicus? Definition, Meaning and Origin,” Investopedia, July 31, 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/homoeconomicus.asp.

21

www.magdalacolloquy.org

With One Accord

O God, our Creator, You, who made us in Your image, give us the grace of inclusion in the heart of Your Church.

R: With one accord, we pray.

Jesus, our Saviour, You, who received the love of women and men, heal what divides us, and bless what unites us.

R: With one accord, we pray.

Holy Spirit, our Comforter, You, who guides this work, provide for us as we hold in hope Your will for the good of all.

R: With one accord, we pray.

Mary, mother of God, pray for us. St. Joseph, stay close to us.

Divine Wisdom, enlighten us.

R: With one accord, we pray. Amen.

We welcome your comments and reactions and will consider sharing them in future editions or on our website. Please send to editor@magdalacolloquy.org

If you haven’t already subscribed, you can do so at any time at no cost due to the generous support of the Basilian Fathers of the Congregation of St. Basil. Just visit our website www.magdalacolloquy.org where you can also read past issues of the journal and be informed of our ongoing activities and news items.

With One Accord journal is published in English, Italian and French. To access the other language editions please visit our website.

With One Accord signature music for the Magdala interview composed by Dr. John Paul Farahat and performed by Emily VanBerkum and John Paul Farahat.

Images used in this edition:

Cover and Page 2: “Redwood in park” photo by John Dalla Costa.

Page 3 “Head of Christ” (1648) by Rembrandt.

Page 7 Detail from “Susannah and the Elders” (1643) by Massimo Stanzione Stådel.

Page 8 Detail from “Mary Magdalene anoints Jesus” by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (l794-1872).

Page 13 “The Miraculous Draught of Fishes)” (l545) by Jacopo Bassano..

Page 14 “Upon your word, I will cast my nets” by Elena Manganelli O.S.A.

Page 19 “Poppy field in Tuscany” by John Dalla Costa.

Page 20 Detail from Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” (1490).

This edition

Copyright © 2023 Saint Basil’s Catholic Parish, Toronto, Canada

For editorial enquiries, please contact editor@magdalacolloquy.org

ISSN 2563-7924

PUBLISHER

Morgan V. Rice CSB.

EDITOR

Lucinda M. Vardey

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Emily VanBerkum

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

Gregory Rupik

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

Michael Pirri

VIDEO EDITOR

Michael Pirri

CONSULTANT

John Dalla Costa

TRANSLATORS

Elena Buia Rutt (Italian)

Véronique Viellerobe (French)

ADMINISTRATOR

Margaret D’Elia

Lucinda M. Vardey

Lucinda M. Vardey