THE STUDENT PERSPECTIVE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Country, the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and the Boon Wurrung Bunurong Peoples of the Kulin Nation.

We pay our respects to and recognise the contributions of their Elders past and present.

Figure 2. Footscray Park, view through the trees.Image credit: Eliza Kane.

INTRODUCTION

This Chapter 1 (Introduction) provides an overview of the Professional Practice intensive unit and the Compact City design studio and introduces us as students of the Master of Urban Planning and Design.

Figure 3. MUPD students, semester 1 2024. Image credit: Yiming Li.

1.1 INTRODUCTION

In the first semester of the Master of Urban Planning and Design (MUPD) course, we undertook:

z a semester long studio / planning projectthe Compact City: Targeting a more liveable Footscray; and

z a two-week intensive Professional Practice unit (during the semester),

focusing on housing and liveability - using Footscray as our case study ‘Compact City’.

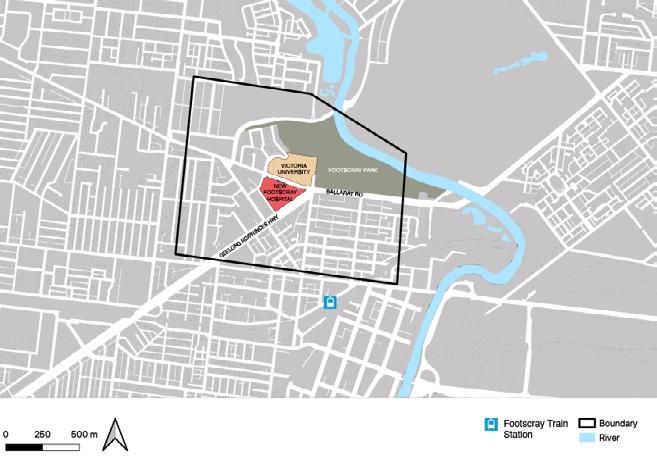

The focus of the Compact City design studio is to plan and design for a more liveable Footscray. Each group focuses on a different ‘precinct’ within Footscray to map out a range of strategies and actions to achieve improved outcomes for housing, the natural environment, transport and community and activation.

The focus of the Professional Practice unit is to explore the professional roles and responsibilities of urban professionals and the implications of urban planning and design on outcomes in the built and natural environments.

While two separate subjects, these units are taught in parallel to give students an in-depth insight into the role and responsibilities of urban professionals and then be able to apply the professional practice context to the planning and designing of a more liveable Footscray.

This publication documents our learnings and reflections from the Compact City design studio and Professional Practice intensive unit, including the key outcomes and a summary of the final design report documenting our strategies, actions and implementation plans for our focus area in Footscray - the Health and Education Precinct.

Within this document, we highlight the concepts and ways of learning we have explored and engaged with. Through these lenses, we also share our key takeaways and reflections on how urban professionals and considered urban planning and design can enhance the liveability of the urban environment.

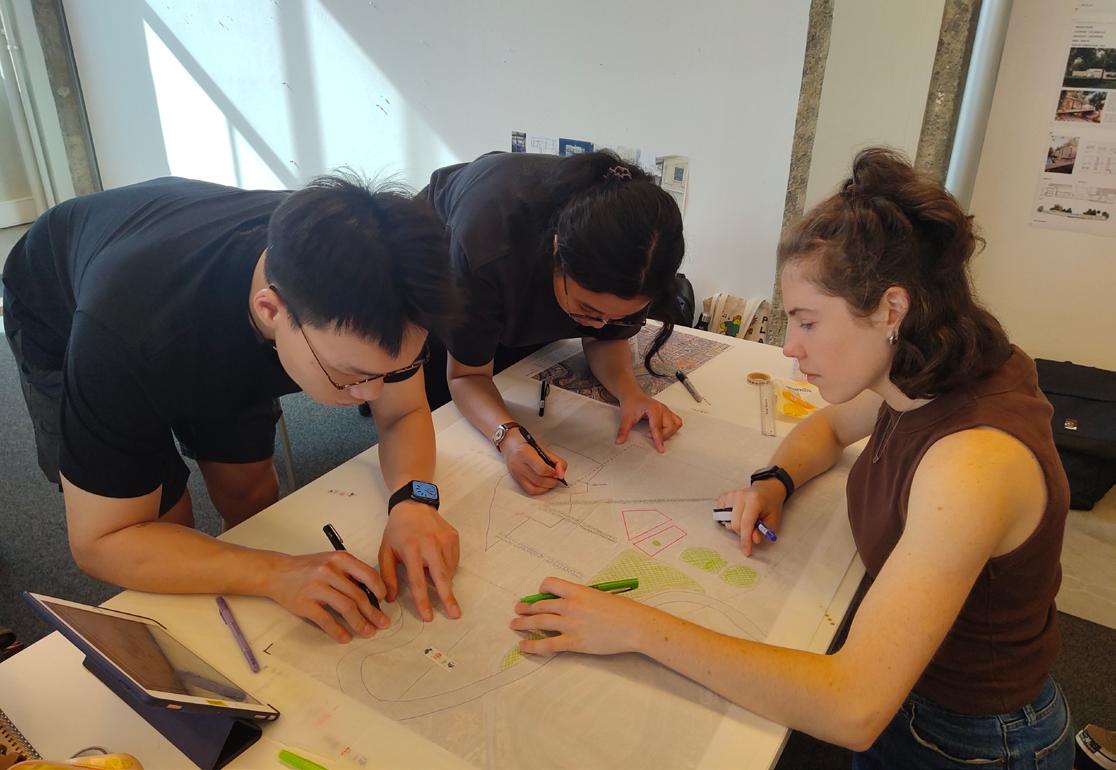

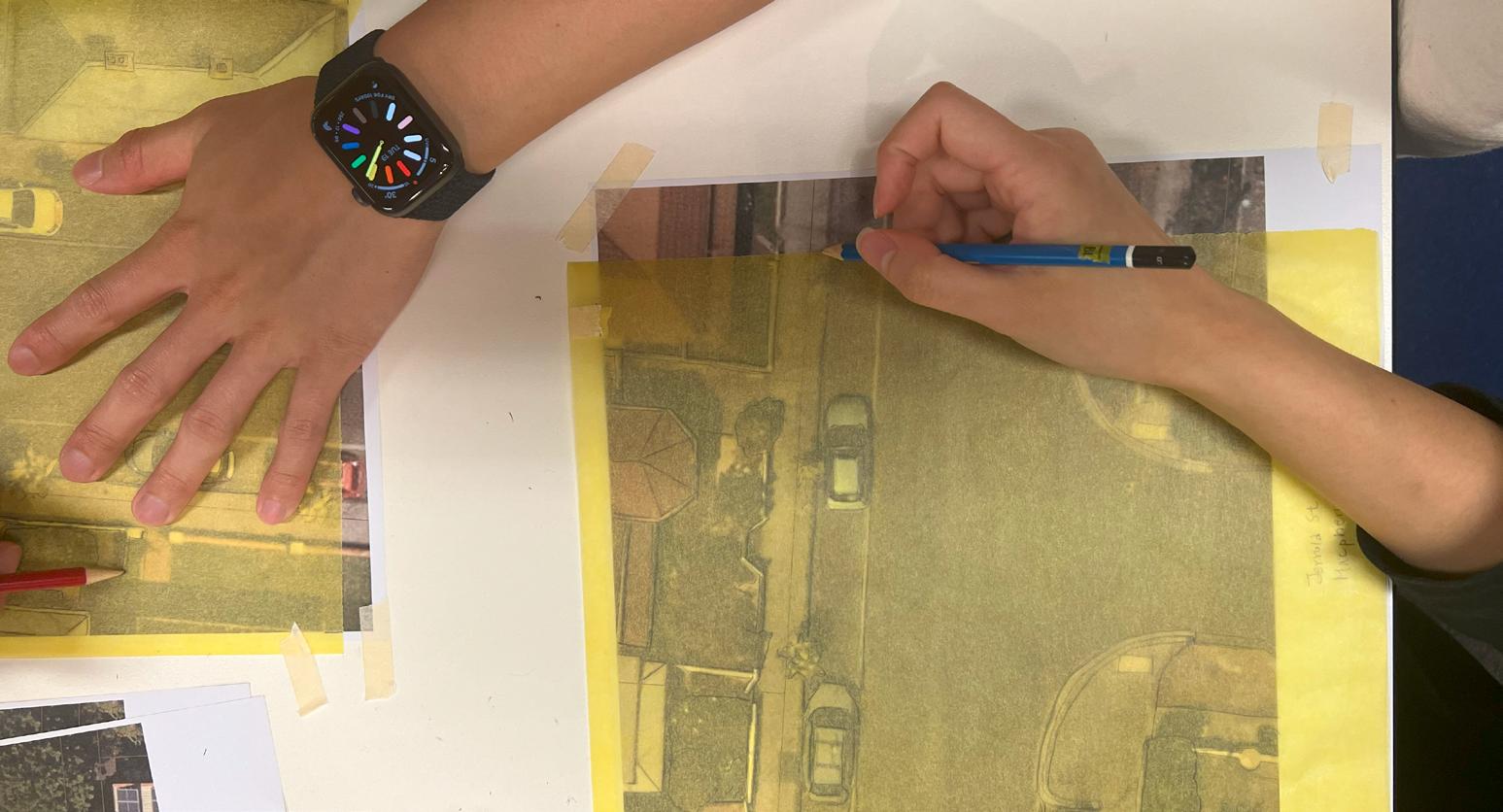

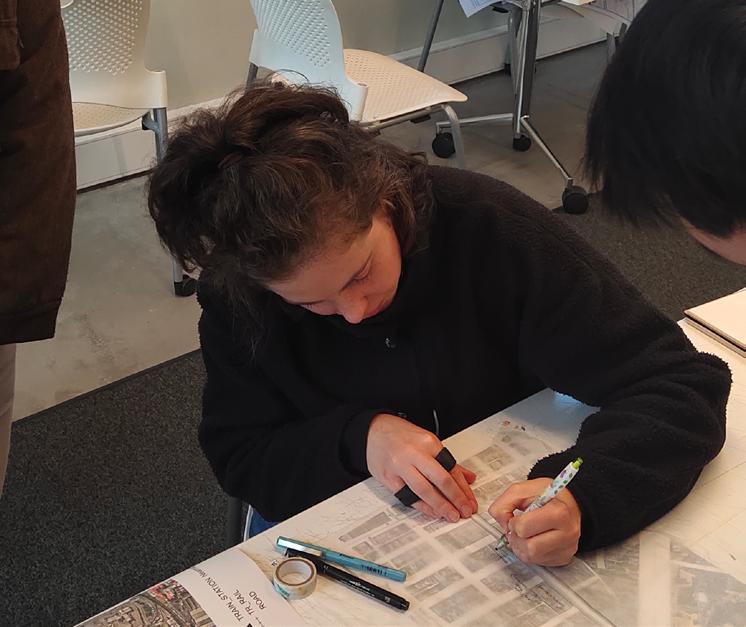

Figure 4. Mapping and tracing exercise. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Figure 5. Walking tour of Footscray with council officers. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

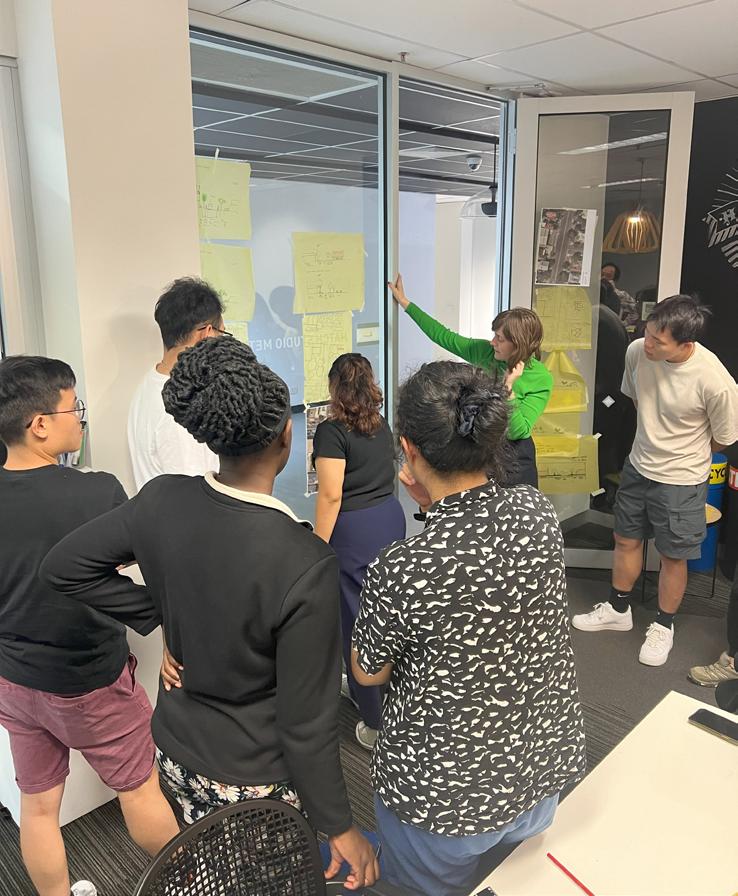

Figure 6. Issues and opportunities brainstorming exercise. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

1.2 ABOUT US

Like many prospective students and urban professionals, we have come to the MUPD program from different countries and with different educational and professional backgrounds, but all with a keen interest in the built and natural environments. Our diversity of backgrounds, skill sets and knowledge enables us to approach urban planning and design issues from a range of perspectives and to learn from each other as we navigate each day of the design studio and intensive unit.

Q: Where do I come from?

Deyna: Indonesia. I have been surrounded by family who work for community welfare such as policy makers, doctors and lecturers.

Q: What is my background?

Deyna: I graduated as an interior architect in 2016. I was an interior practitioner in private consultancies and a researcher of building technology.

Q: What skills / experience have I brought to the studio?

Deyna: I bring my way of thinking as a designer which I apply in analysing the challenges and potentials the site has, specifically in relation to the housing theme.

Q: What have I learnt from the studio?

Deyna: I previously thought that the absolute decision in planning and designing cities is always in political power. After the studio, I have learnt that with comprehensive and critical planning, the right stakeholders and democracy, the proper urban fabric can indeed be sewn.

Q: What is a highlight from the intensive / studio?

Deyna: Despite the intensive nature of professional practice, the two-week experience enhanced my focus on learning urban planning in group work. Lectures were the most engaging aspect of the planning project studio, with clear topics divided each session and relevant experiences from diverse lecturers.

Q: Where do I come from?

Joyce: Hong Kong. Growing up and spending most of my life in Asia, I am familiar with Asian culture and context.

Q:What is my background?

Joyce: I studied Geography and Resources Management in Hong Kong. This undergraduate degree included research-based courses about understanding different natural and urban phenomenon in the Hong Kong context.

Q: What skills / experience have I brought to the studio?

Joyce: With my personal and academic background, I bring inspirations from Asian examples and research skills from my undergraduate studies to our studio projects.

Q: What have we learnt from the studio?

Joyce: What is remarkable to me is the planning system and government structure in Victoria – it is completely different from the one I am familiar with, especially the type of housing and development strategies.

Q:What is a highlight from the intensive / studio?

Joyce: Both the intensive and studio units improved my understanding of the values and thoughts of Victorians, as well as their concerns and interests about local planning systems and communities. In addition, developing a strategic plan for promoting liveability of a neighbourhood of Footscray and highlighting the local features from a planning perspective was a highlight of the design studio.

Figure 7. From left to right: Eliza, Jamie, Joyce, and Deyna. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 8. Deyna (left) researching and Jamie (right) tracing. Image credit:

Deynanti Primalaila

Joyce Siu

1.2 ABOUT US

Eliza Kane

Q: Where do I come from?

Eliza: Melbourne, Australia.

Q: What is my background?

Eliza: I have a commercial, legal background - I graduated Bachelors of Commerce / Law from Monash University (Clayton) in 2019 and worked as a lawyer, specialising in major infrastructure and construction projects, for a number of years prior to embarking on the MUPD.

Q: What skills / experience have I brought to the studio?

Eliza: Through my educational and professional experience, I have obtained an insight into the construction industry and state government planning activities, which I have been able to apply to the MUPD. I also have an understanding of how to interpret and apply regulatory frameworks - like a planning scheme!

Q: What have I learnt from the studio?

Eliza: The first eight weeks has been a steep learning curve! As someone who has limited design and visual communication experience, learning how to present and communicate information graphically (through photographs, maps and diagrams) has been a challenging but valuable experience.

Q: What is a highlight from the intensive / studio?

Eliza: Presenting to urban professionals, including Maribyrnong City Council officers was definitely a highlight. This was a great opportunity to present our vision and strategies for the Footscray Health and Education Precinct in a safe and supportive environment and receive practical and insightful feedback.

Jamie Lam

Q: Where do I come from?

Jamie: Hong Kong.

Q: What is my background?

Jamie: I graduated with a bachelor’s degree in environmental science. After that, I spent a few years working as an environmental consultant, focusing on green building projects before coming back to study.

Q: What skills / experience have I brought to the studio?

Jamie: What I bring to the studio is my international background and passion for the environment. Being an international student, I have different perspectives and ideas to contribute about urban planning. This helps make our studio a place that is not just about local views, but also about global thinking.

Q: What have I learnt from the studio?

Jamie: In our studio, I have a great opportunity to learn from others (such as cultural knowledge), exchange different cultural values and beliefs and develop skills to understand and respect each other’s cultural backgrounds. I have also gained valuable professional knowledge through courses, practical experiences and guest lectures. This includes learning software, improving my drawing skills, mastering presentation skills, and practising my data analysis abilities.

Q. What is a highlight from the intensive / studio?

Jamie: The highlight of the studio is that we could meet and learn from the Maribyrnong City Council. It was a valuable and exciting experience that I could meet industry people during the study period.

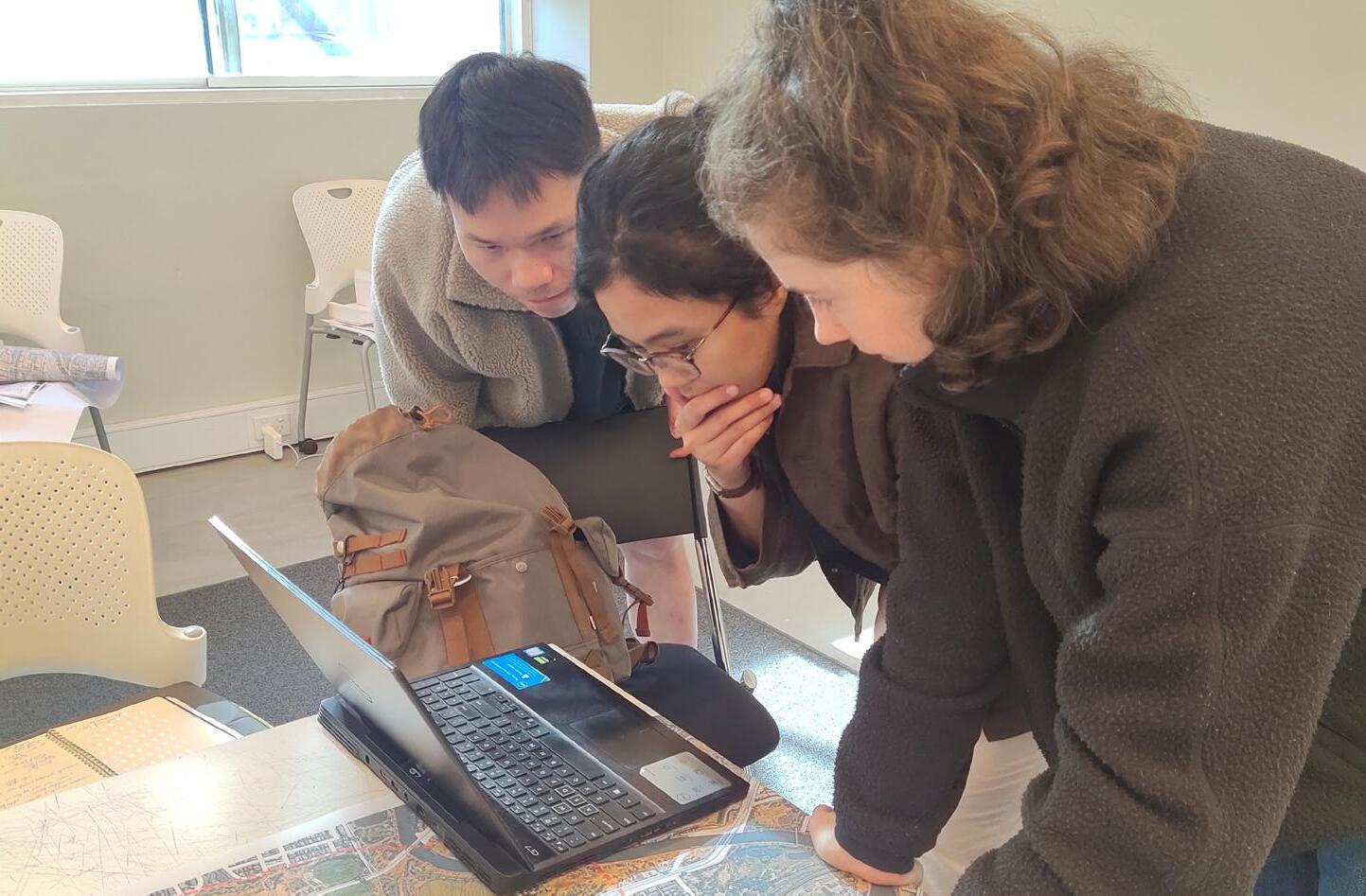

Figure 9. Jamie (left), Deyna (middle) and Eliza (right) working on implementation plans of Footscray project. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 10. Jamie (left), Deyna (middle) and Eliza (right) during a site visit in Footscray. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

1.3 STUDIO OVERVIEW

Planning project - the Compact City: Targeting a more liveable Footscray

Week 1 Week 2

Defining the challenge

Week 5 Week 7 Week 3

Learning from elsewhere

Week 6

Understanding context (Footscray Intensive)

Place and vision (Footscray Intensive)

Week 8 Week 4

Refining our message

Bringing it all together

Precinct strategies

Precinct strategies

1.3 STUDIO OVERVIEW

Planning project - the Compact City: Targeting a more liveable Footscray

Week 9

Implementation and catalyst projects

Week 10

Week 11

Synthesis and storytelling Implementation and catalyst projects

Week 12

Presenting a compelling strategy

Week 13

Final Report

Week 15

Studio walk through

1.3 STUDIO OVERVIEW

Planning project - the Compact City: Targeting a more liveable Footscray

The MUPD planning project – ‘the Compact City: Targeting a more liveable Footscray’ explores the concept of liveability in the context of the urban environment.

Using Footscray as our case study ‘Compact City’, we:

• investigated urban planning and design concepts and strategies,

• applied different ways of learning, design thinking and strategic and data analysis; and

• been on the ground, observing and engaging with the physical features and cultural values,

in order to:

• identify key issues and opportunities, through the lenses of ecology, landscape and public realm; transport and connectivity; built form and housing; and culture, community and activation; and

• develop strategies, actions and implementation plans to enhance the liveability of Footscray in the future.

Highlights

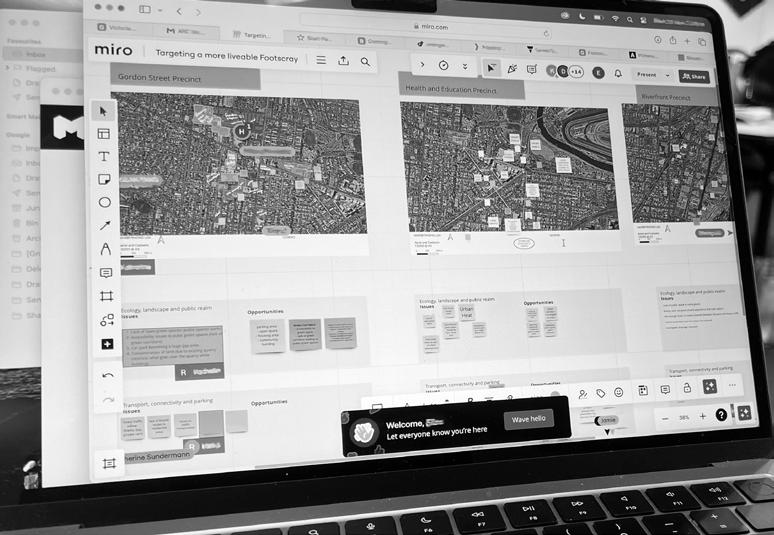

z Guest speaker: presentation by Ashley Minniti (Acting Director Planning and Environment Services, City of Maribyrnong), introducing the issues and opportunities for urban intensification in Footscray.

z Bus tour: experiencing different housing models around Melbourne - Studio Nine (Richmond), Clyde Mews (Thornbury) and Nightingale Village (Brunswick).

z Workshop: introduction to QGIS software and plan making, spatial analysis, scales, layers and themes of a place.

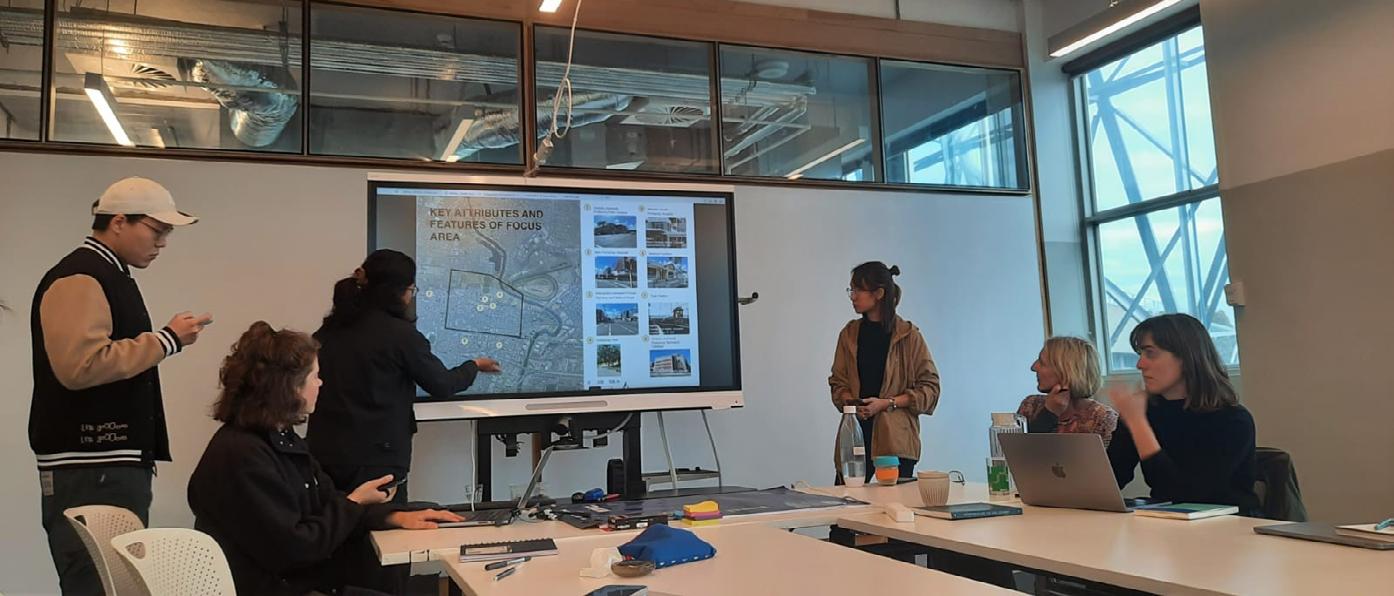

z Site visit: guided tour of Footscray focus areas with Maribyrnong City Council council officers.

z Presentations: presenting our final presentation to Maribyrnong City Council officers and urban professional panel guests.

Figure 12. Nicholson Street, Footscray from site visit in Footscray. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 13. Mapping and tracing exercise. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Figure 11. Site visit to Nightingale Village (Brunswick). Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Applied Professional Practice: Urban Planning and Design Communication

DAY1 DAY2

Understanding the profession

Spatial context

DAY5

Understanding place identity

DAY6

Governance and context

DAY7 DAY3

DAY4

Understanding place

Issues and opportunities

DAY8

Vision and targets

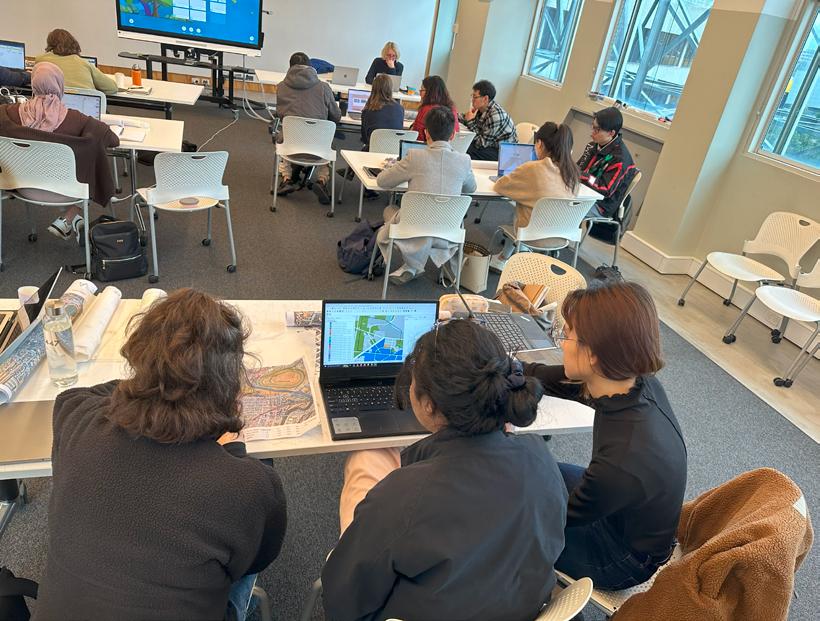

1.3 INTENSIVE UNIT OVERVIEW

Applied Professional Practice: Urban Planning and Design Communication

The Professional Practice intensive unit held in Footscray explored two major themes over two weeks: context in the first week and vision and place in the second week.

In the first week, we investigated the geographical, political, social, and strategical background of each of our designated Footscray precincts, to determine the potential directions for the precinct for our upcoming project.

In the second week, we continued to explore and research our precincts, including through a number of physical site visits, in order to identify specific issues faced by our studied precinct and potential opportunities to enhance the liveability of this compact city.

Highlights

z On-site experiences: exploring the studied precincts to experience and understand the daily life, neighbourhood character and built environment of Footscray.

z Photography workshops: photography skills workshop led by photographer Tobias Titz, who provided useful photography tips and highlighted the importance of capturing ideas in the built environment.

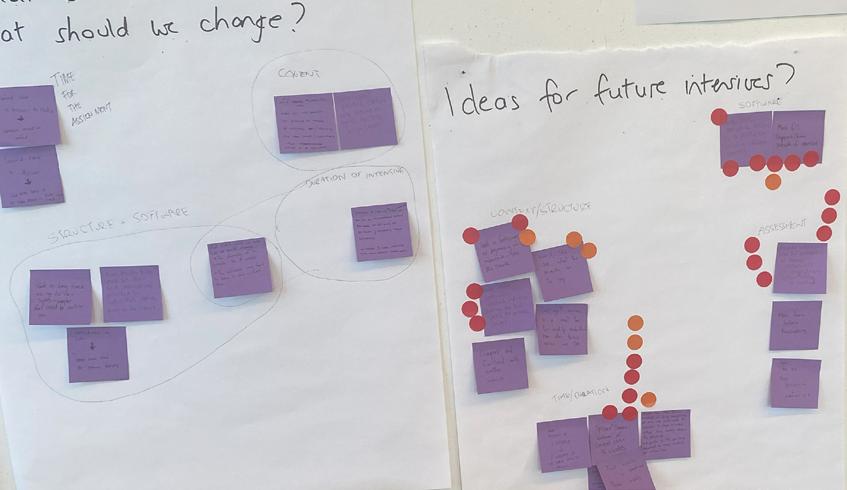

z Group feedback session: using techniques and strategies which would be employed in planning community consultation sessions to provide feedback on the intensive course. Tools like stickynotes and dot stickers enabled different personalities (introverts and extroverts) to discuss ideas and provide feedback effectively.

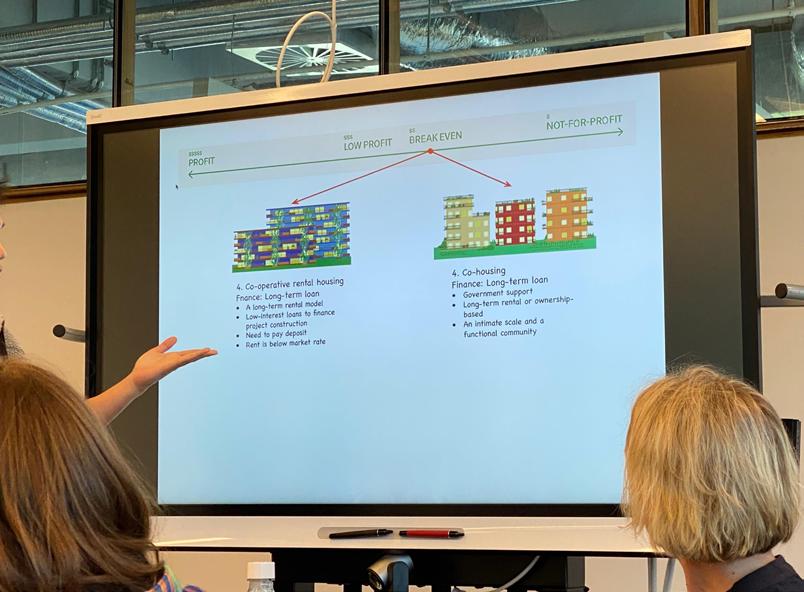

Figure 15. Guest lectures held in Footscray. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 16. Exploring targeted precinct in Footscray. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 14. Activity during photography workshops. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

UNDERSTANDING THE PRACTICE 2

This Chapter 2 (Understanding the Practice) documents our understanding of the role, responsibilities and impact of urban professionals and how this has been informed through the Professional Practice intensive unit and the Compact City design studio.

Figure 17. Site visit to Nightingale Village (Brunswick) with lecturers. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

2.1 UNDERSTANDING THE PRACTICE

Many of us have come to the MUPD program with limited experience or understanding of who urban professionals are and what they actually do, and what we could do if we enter the profession ourselves.

Learning about the urban profession from the urban professionals themselves.

However, through the Compact City design studio and the Professional Practice intensive unit, in a short period of time, we have been introduced to a number of practising urban professions - on site visits, walking tours and guest speakers. All of these professionals come from different areas of the profession and with a diverse range of agendas and experience as urban professionals.

Hearing about real-world experiences and projects from these guest speakers has given us valuable insights into the profession, including how wide ranging the impact that we could have to achieve liveability in the built environment. In addition to giving us an understanding of the urban profession, this also provided us with further awareness of issues and opportunities in the built environment.

Figure 18. Guest speaker, Pat Fensham (SGS Economics) discussing lot consolidation strategies.

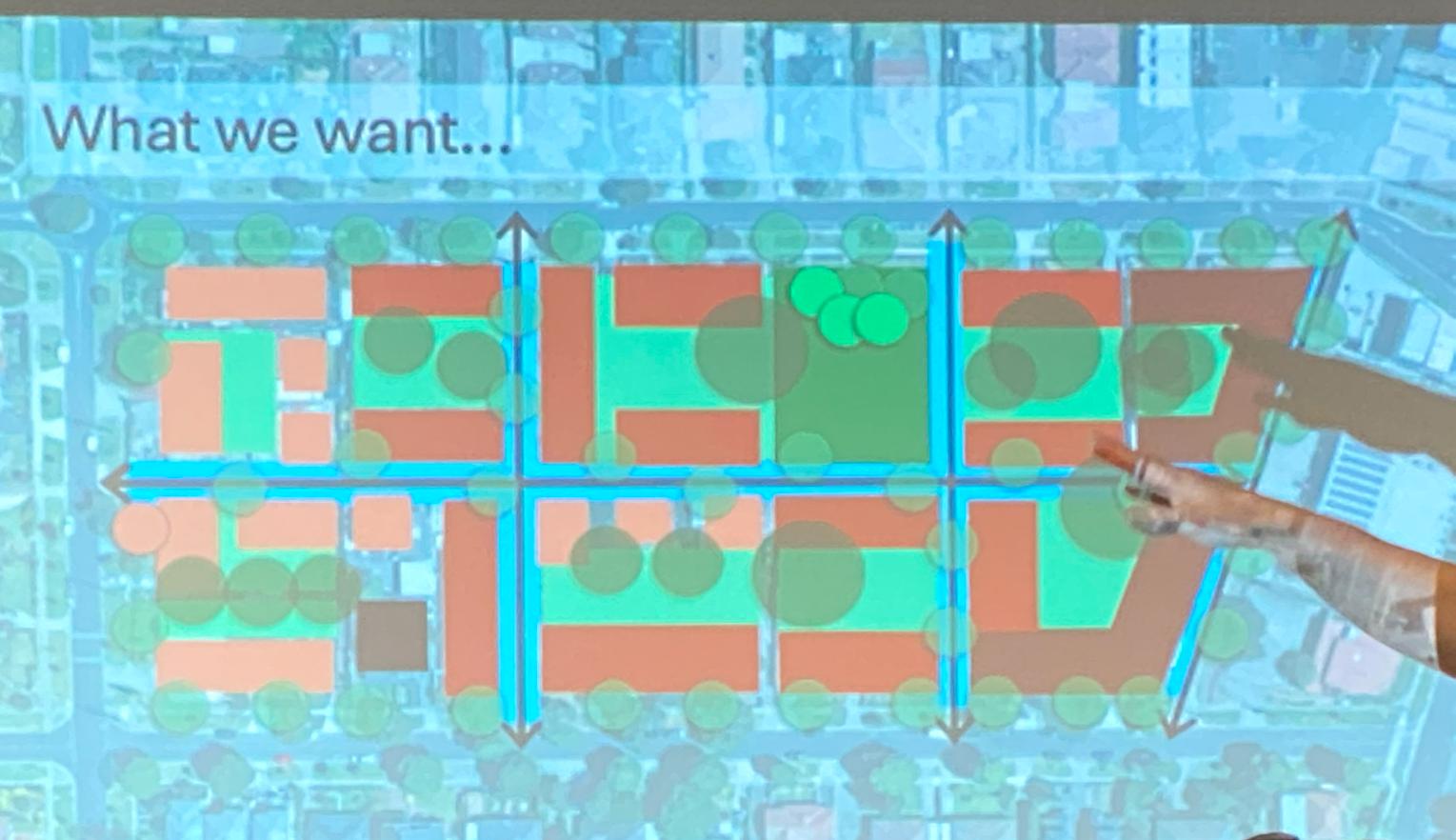

Figure 19. Extract of presentation - “Introduction to issues and opportunities in Footscray” - Ashley Minniti (Maribyrnong City Council) in week one.

2.1 UNDERSTANDING THE PRACTICE

In a short period of time, we have had the opportunity to learn from people from different areas of the profession, for example:

Using realworld professional experiences as a road map to a more liveable Footscray.

• Ashley Minniti (Acting Director Planning and Environment Services, City of Maribyrnong) provided us with an early insight into the strategic direction for Footscray, sharing with us key issues and opportunities for Footscray. This was a helpful introduction to Footscray and the Council’s current thinking of proposed actions for the area, prior to us visiting Footscray for the intensive unit.

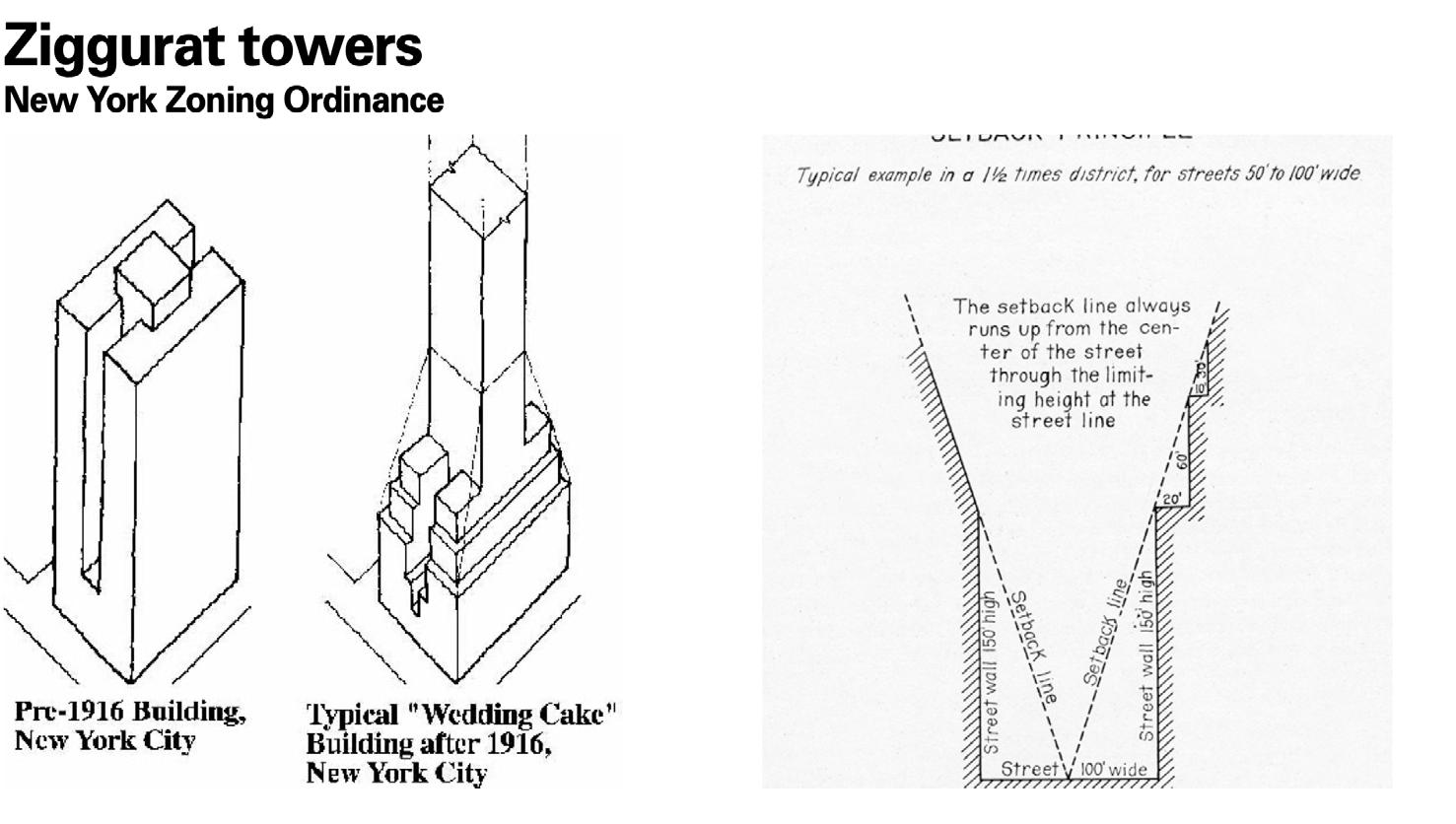

• Andy Fergus (Assemble Communities; Urban Design Forum) introduced us to the urban profession, from both a planning and design perspective. From his experience in the public and private spheres, and using local and international case studies, Andy explained the role that regulation and stakeholders play in planning and design and the way that these tools can be employed to achieve specific design outcomes. This prompted us to think about how this could be used in the Footscray context.

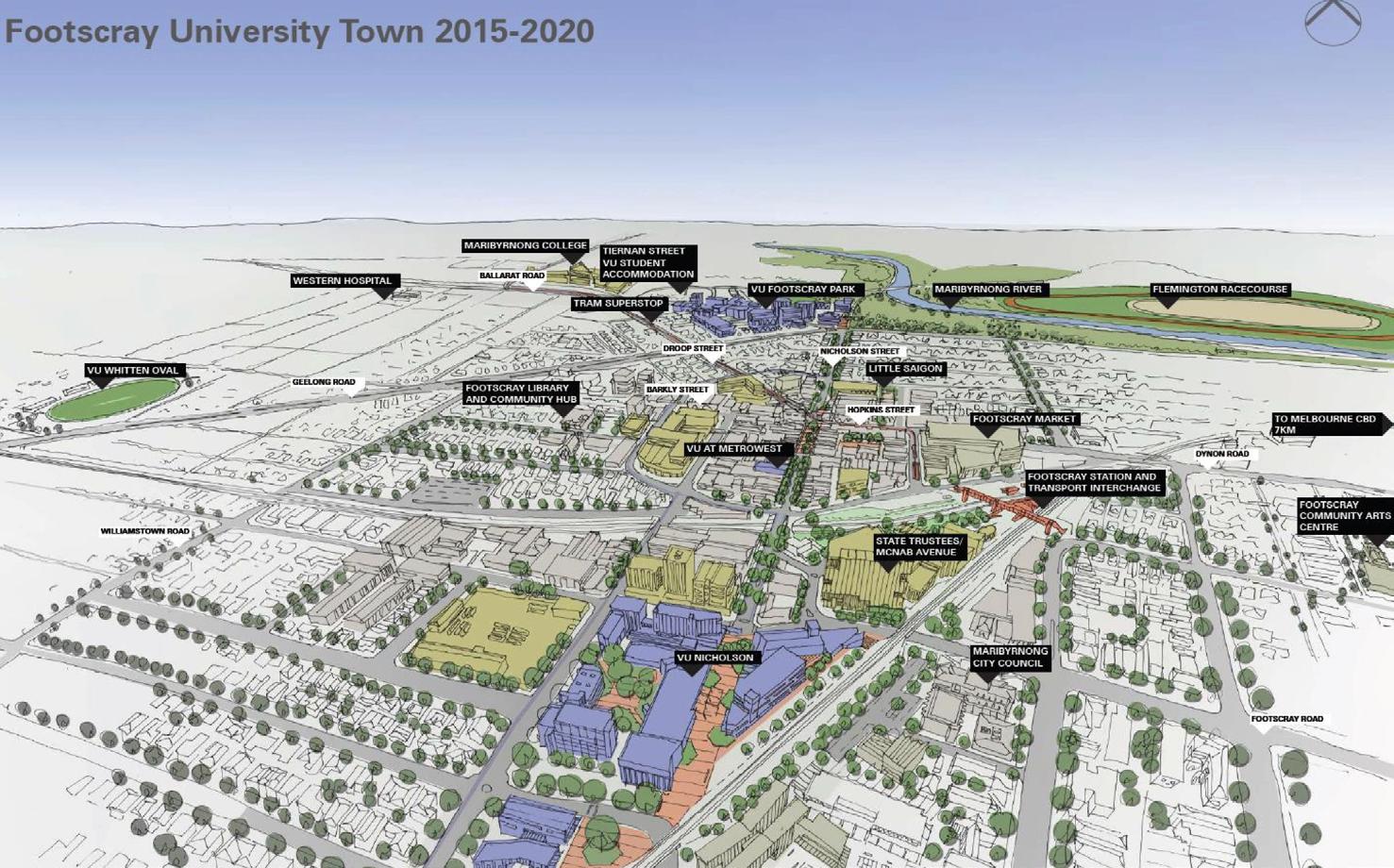

• Rob McGauran (Director, MGS Architects) provided us with a different perspective of Footscray, from his experience working with Victoria University on the University Town Strategy and in relation to the New Footscray Hospital.

Figure 20. Extract of presentation by Rob McGauran (Director, MGS Architects) - big picture of Footscray University Town 2015-2020.

Figure 21. Extract of presentation by Andy Fergus (Assemble Communities; Urban Design Forum)architectural and planning concepts case study.

CONCEPTS

This Chapter 3 (Concepts) details different practical and theoretical concepts we have explored through the Professional Practice intensive unit and Compact City design studio, specifically:

• theoretical concepts

• spatial context

• place and place identity

• governance and strategy

• issues and opportunities.

Figure 22. Tracing and mapping exercise. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

3.1 THEORETICAL CONCEPTS

At the beginning of the semester, students were assigned to conduct a literature review task relating to urban planning and design theory as an introduction to the complex realm of urban planning and design. This learning approach, involving presentations and discussions, efficiently and collaboratively fostered our understanding and engagement with related core concepts.

Core theoretical concepts are addressed collaboratively to shape the initial thinking and learning framework of urban planning and design.

The main concepts we learned were living close together; understanding the DNA of a place; open space, public realm, and ecology; transportation and connectivity; housing approach; creating lively and livable places; sustainability and resilience.

Through this exercise, we delved into the concept of the compact city and identity of a place. We also explored the themes of livability and sustainability as our ultimate goal. These concepts are crucial for our learning process and assisted us in investigating and recognising issues and opportunities and developing targets, vision, strategies, and implementation plans properly for our focus area of the Health and Education Precinct in Footscray.

Figure 23. Photos of a neighbourhood to understand the DNA of a place from theoretical concept presentation. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 25. Student presenting range of housing as one of the core concept. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 24. Diagram of theoretical approach as learning framework from Footscray studio presentation. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

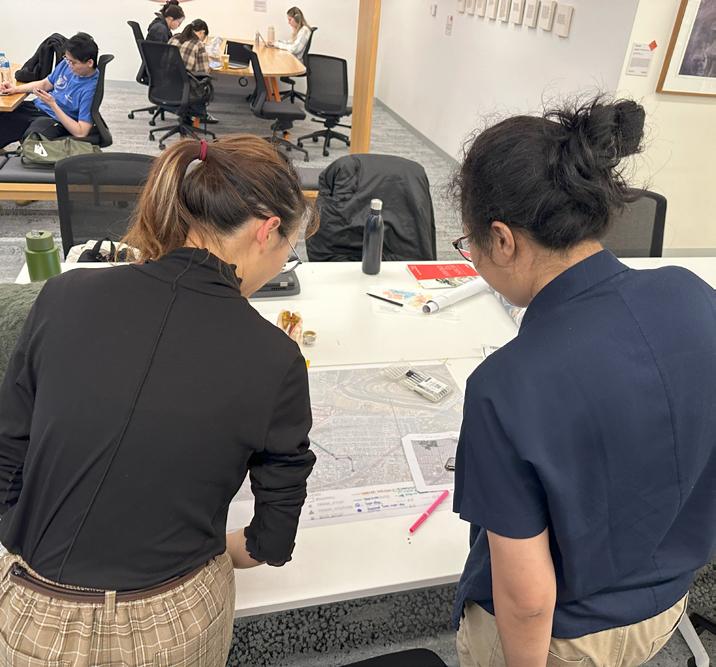

3.2 SPATIAL CONTEXT

Spatial context is like having a mental map of where things are. It helps us to understand how places connect and how people interact with them. In urban planning, this is important as it helps us plan and design cities which are aligned with how people truly live within them.

We have learnt about spatial context through techniques like mapping and section drawing.

Spatial

context is

an important visual tool which enables us to understand and communicate information about the urban environment.

Mapping and section drawing are visual tools to show the physical elements of a specific area from different perspectives, such as an aerial view (mapping) and a vertical cut transecting a particular area (for a section drawing).

Spatial context can be explored through different layers and themes such as public realm, transport networks, building heights and density, as well as culture and activation. Mapping of layers allowed us to form an in-depth understanding of the spatial context of a place (see fig 28).

Through the design studio, we have also learnt different perspectives of spatial context by observing and discussing others’ drawings. As everyone has their unique perspective on space, we saw a diverse range of mappings and section drawings which planned out future strategies (see fig 27).

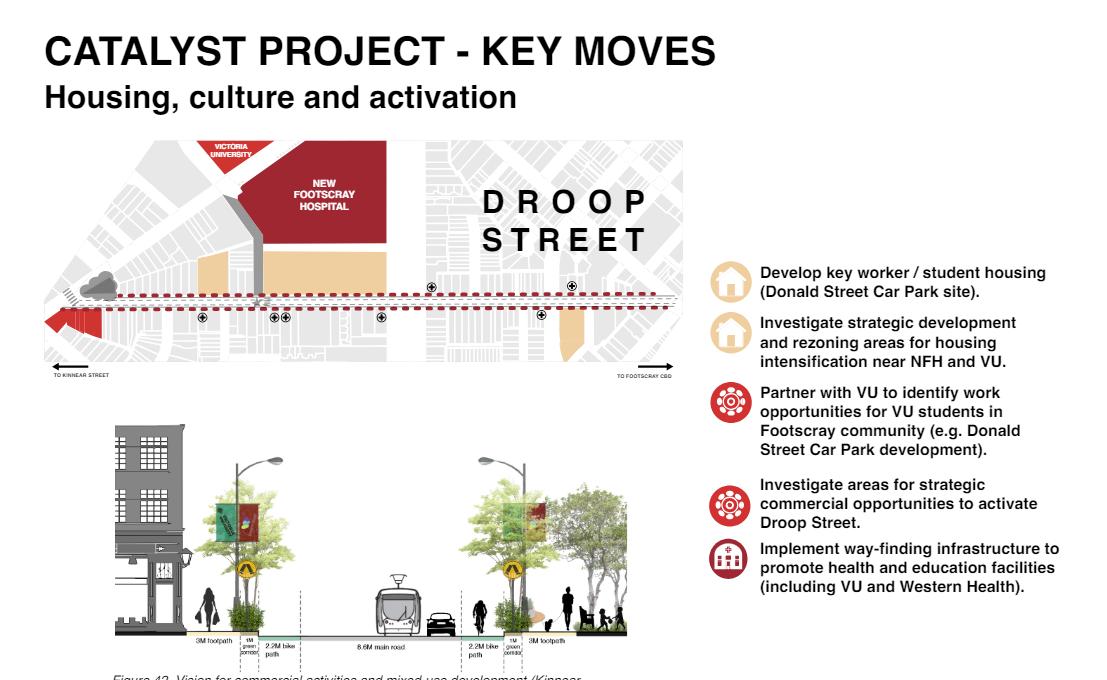

Figure 28. Section of proposed development of Droop Street in Footscray’s health and education precinct. Image credit: Jamie Lam.

Figure 27. Discussing each other’s plans and section drawings. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Figure 26. Learning mappings and section drawings. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Figure 29. Collage of proposed development of Droop Street in Footscray’s health and education precinct. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

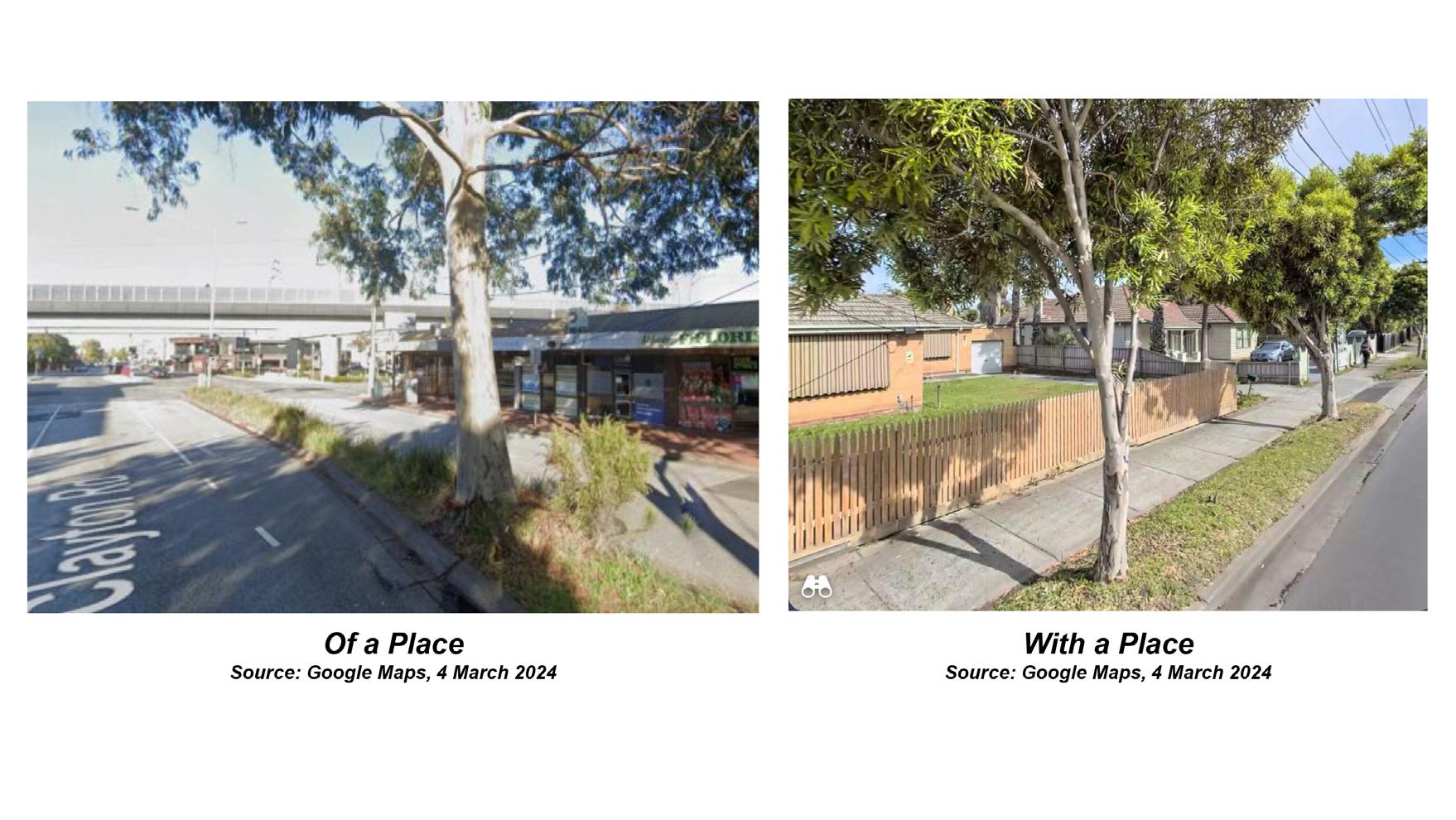

3.3 PLACE AND PLACE IDENTITY

The liveability of an urban environment is so much more than the sum of its physical components and built form.

No plan or design can be created in isolation of the place which it is created for. Designing, developing and implementing effective urban plans and strategies for a city requires urban planners and designers to have an in-depth understanding of its DNA:

Meaningful understanding of ‘place’ and ‘place identity’ is fundamental to effective urban design and planning strategy.

How does a place look, feel and sound?

How do people move through or remain still within its spaces?

What is valuable and unique about a place?

We have explored place and place identity, through photography workshops, site visits and design analysis tools, to gain an understanding of the importance of these concepts in creating relevant and appropriate strategies and targets for enhancing the liveability of an urban environment.

Figure 30. Walking tour of Footscray with council officers. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 31. Site visit to Clyde Mews (Thornbury). Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 32. Legibility analysis map (design tool) of Footscray ‘health and education precinct’. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

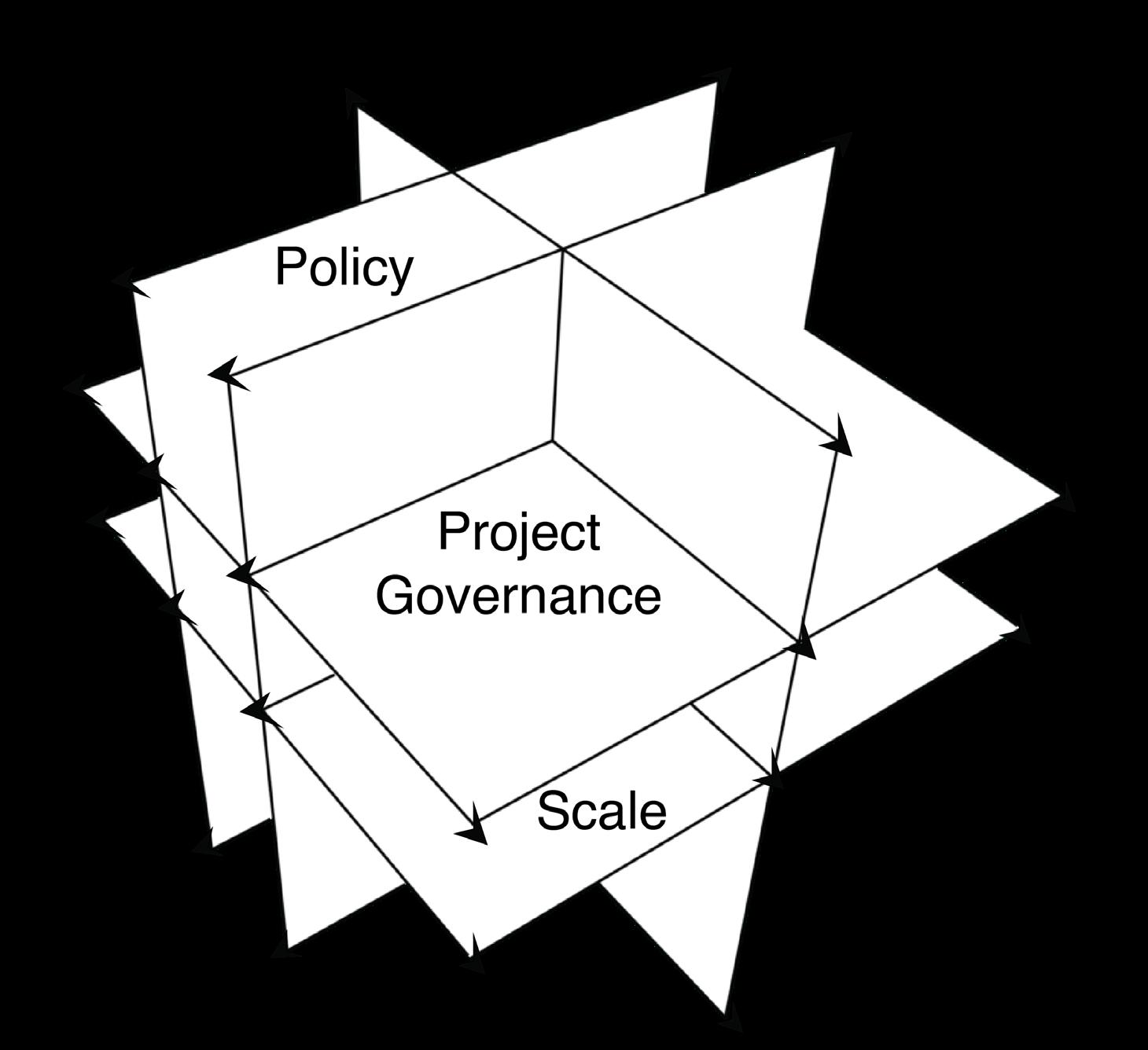

3.4 GOVERNANCE AND STRATEGY

Knowing the players and strategic context provides guidance and direction to develop urban environments which are appealing and achieve social outcomes.

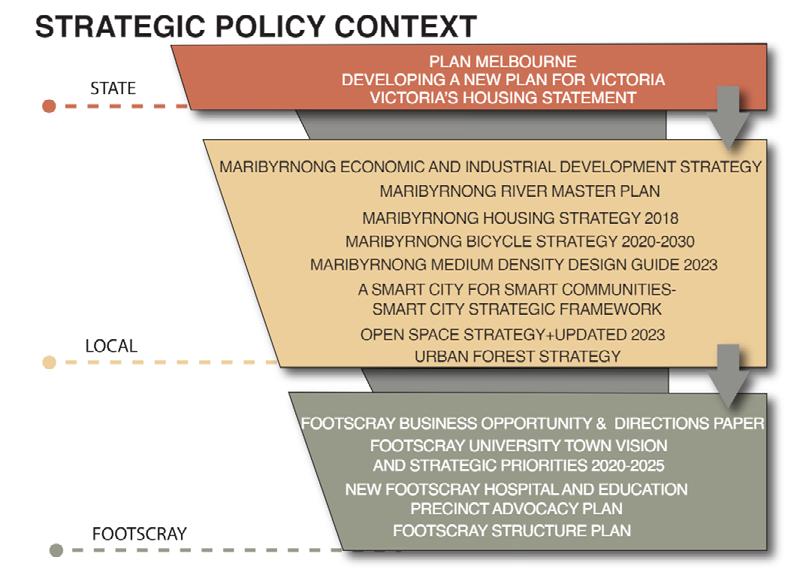

Understanding the governance framework and strategic context is critical to urban planners and designers. Within this context we can identify issues and propose solutions for the built environment. In any urban planning project, there are also a large number of stakeholders who may need to be considered, engaged or even partnered with for the development of a project and to ensure its viability.

The significance of the governance and stakeholder context was highlighted to us through guest lectures, including from Rob McGauran (Director, MGS Architects) who explained this using his experience with Victoria University and New Footscray Hospital as an example of the different actors that can be involved.

Using this as background to the concept, we were then able to explore and map the stakeholder and strategic context relevant to Footscray during in-class activities (see fig 33 and 35). For example, for our studio project, we identified Victoria University and New Footscray Hospital as major stakeholders for the development of Footscray’s health and education precinct (see fig 33).

Figure 35. Diagram of strategic policy context from Footscray studio presentation. Image credit: Jamie Lam.

Figure 33. Victoria University (left) and New Footscray Hospital (right) are two major stakeholders in our Footscray project. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 34. Diagram of actor mapping from Footscray studio presentation. Image credit: Jamie Lam.

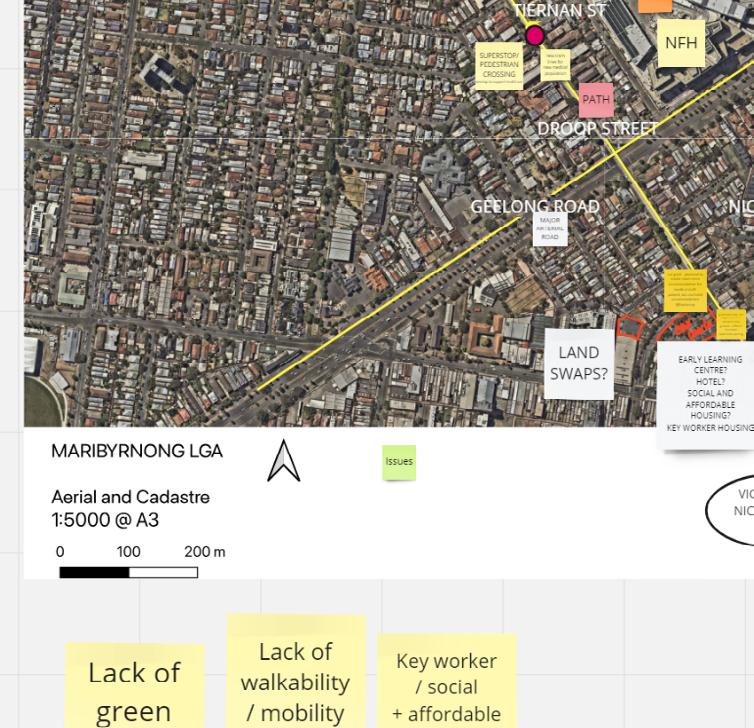

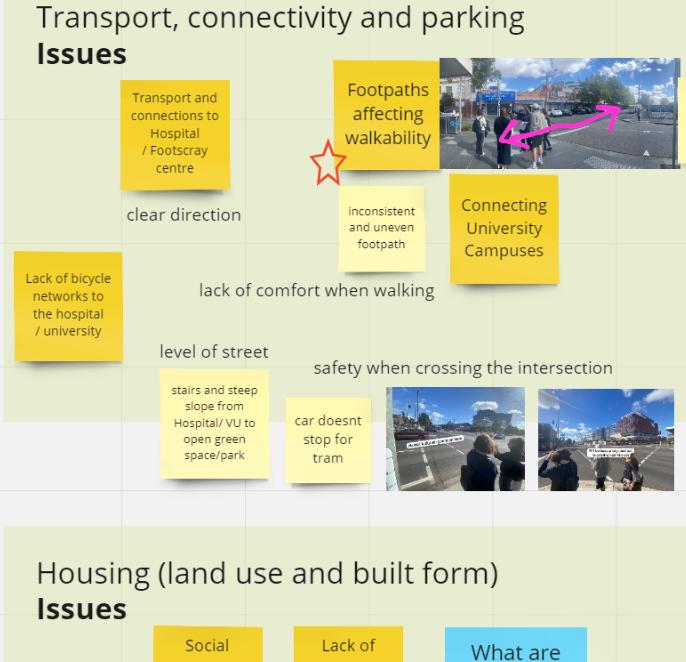

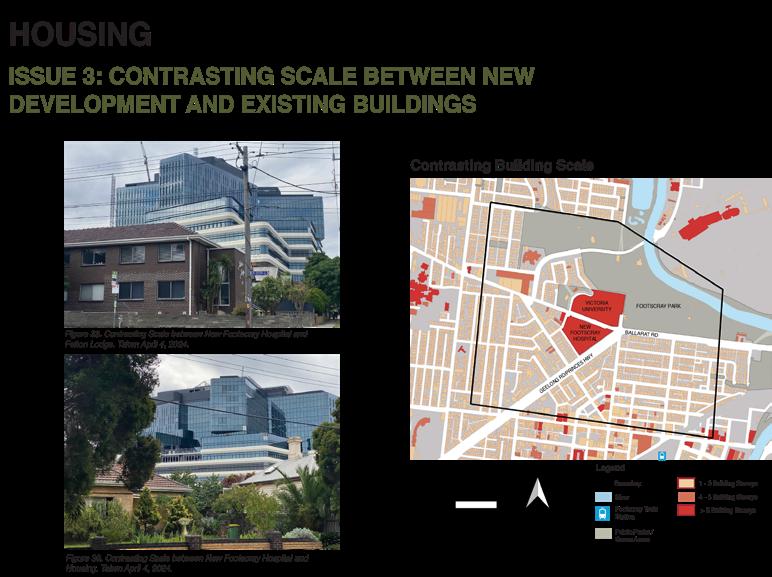

3.5 ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES

To plan comprehensively, planners need to identify the issues that exist in the place. In the Compact City design studio, issues are being defined by themes - housing, transport, ecology, and community. In our focus precinct, we have identified areas where mobility could be improved, with the challenge being to enhance connectivity through transport networks (see fig 35 and 36).

Critically analysing the issues and opportunities is crucial for placebased planning, as they will synthesise into a vision and targets for a better and more liveable place.

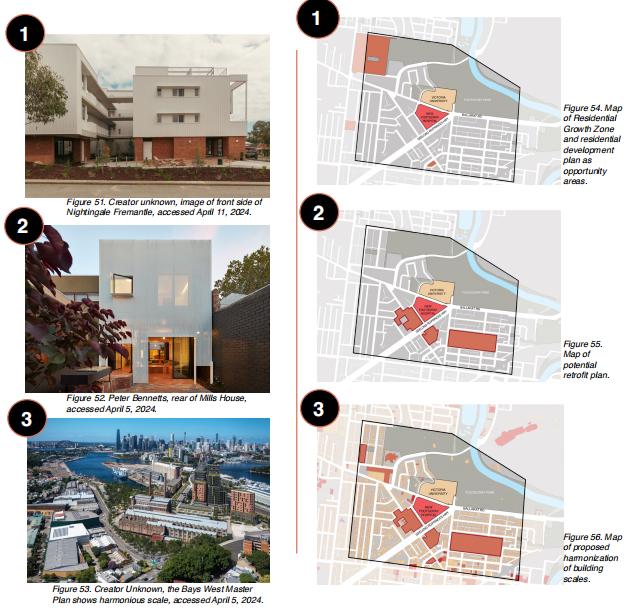

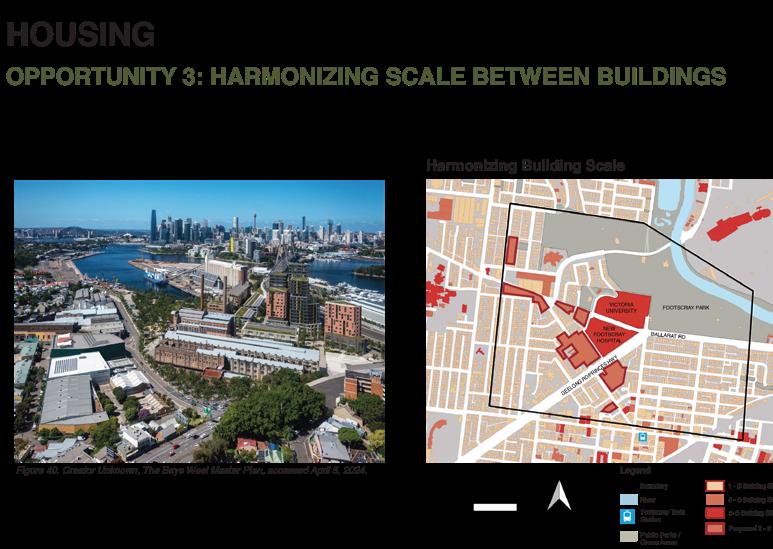

The next step is then developing solutions, by identifying opportunities which correspond to each of the issues. For example, one of the opportunities for improving and increasing housing stock in our precinct is the Residential Growth Zone, an area where medium density housing growth and diversity are encouraged by the government (see fig 37).

By understanding the DNA of a place, planners can then develop a vision to guide the strategy for future development. Visions are created by defining principles and targets, allowing planners to break down the vision to be more specific. For example, a core element of the vision for our precinct is to be responsive to the wellbeing of Footscray’s people.

Figure 36. Brainstorming process to identify relating issues for transport theme after site visit using Miro online platform. Image credit: Eliza Kane, Deynanti Primalaila, Jamie Lam and Joyce Siu.

Figure 37. Identifying issues and opportunities through transport and housing as two of the four themes. Image credit: Eliza Kane, Deynanti Primalaila, Jamie Lam and Joyce Siu.

Figure 38. Mapping opportunities with real project examples for housing theme. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 39. Diagram identifying principles of key themes regarding an emerging vision for the precinct. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

WAYS OF LEARNING

This Chapter 4 (Ways of Learning) details different methods of learning that we have experienced through the Professional Practice intensive unit and Compact City design studio, specifically:

• working collaboratively

• site visits

• activities and workshops

• presentations.

Figure 40. Group presenting final Design Studio presentation. Image credit: Rochelle Fernandez.

4.1 WORKING COLLABORATIVELY

Developing and implementing any urban policy, plan or design is a massive task, and which regularly involves working closely with different people, including other urban professionals and stakeholders. Working as part of a group is an important learning experience, as it is closely aligned with how urban professionals often work in the field.

We have found working in groups to be incredibly valuable, specifically:

Working collaboratively is fundamental to the urban profession and contributes to achieving more creative and thoughtful outcomes in the built environment.

Supporting each other: working as a group has allowed us to inspire each other’s creativity and boost our own critical thinking skills. We have found that the best solutions or ideas arise through our collective contributions, from us brainstorming together, providing feedback to each other on our contributions and practising our presentations to ensure our presentations run smoothly.

Leveraging diverse strengths: each group member brings their unique skills to each group activity. For example - Eliza’s logical thinking skills, Deyna’s and Joyce’s strong design sense and Jamie’s fast-paced execution. We work more effectively and efficiently by using each person’s strengths in the allocation of work tasks, but also recognise there are learning opportunities when people test themselves to develop new skills.

Encouraging continuous learning: our team environmental encourages mutual learning and growth, as we share our different skills sets, experiences and resources with each other through each group project assessment.

Figure 43. Working together on mapping. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Figure 42. Group presentation of our understanding of Footscray. Image credit: Zahrul Basimah.

Figure 41. Every group member noticed different things during site visiting, developing ideas from various perspectives. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Being on the ground and experiencing a space provides critical insight into an environment that you will not get from behind a screen.

Everything that urban planners and designers do is based in the real world - experiencing the physical environment and its atmosphere is therefore critical to understanding the space for which you are planning and designing.

Rather than simply sitting behind a screen looking at Google Maps and aerial views, in the Compact City design studio and the Professional Practice intensive unit, we have been on the ground and out walking the streets. This has ranged from from small scale walking tours to investigate Footscray’s footpath, to site visits of different high(er) density housing models located around Melbourne and, at larger scale, walking tours through the Footscray precincts with Maribyrnong City Council council officers.

Through these activities, we have been able to gain an insight into the environment which we are studying and why real-world experience of an urban environment elevates urban professionals from being good to being impactful.

Figure 44. Walking tour of Footscray’s footpaths with Yvonne Meng (PhD candidate, Circle Studio Architects). Image credit: Eliza Kane.

Figure 46. Site visit around Footscray with council officers. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 45. Site visit to Studio Nine (Richmond). Image credit: Joyce Siu.

4.3 ACTIVITIES AND WORKSHOPS

Participating in diversified, handson activities helps us to develop essential skills effectively and efficiently.

Unlike common practices in many university courses (which are conducted mostly through lectures and tutorials), we have been learning about and practicing planning and design skills through various in-class activities and hands-on workshops. To date, we have undertaken software workshops using Adobe Creative Suite programs and QGIS, physically mapped issues and opportunities for our Footscray precinct, and even participated in a ‘community consultation’like session - to provide feedback on the Professional Practice intensive unit (see fig 50).

These practical experiences have enabled us to understand how to implement different practical planning and design tools and equipped us with foundational skills frequently employed by urban professionals. While many of us came to the MUPD program with little design experience, we are now able to generate visually appealing presentations and reports, and understand how to use visual mediums (e.g. maps, sections and plans) to illustrate our planning ideas and visions (see fig 49).

Figure 48. Our works during InDesign tutorial. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 50. Comments by sticky-notes and voting by dot stickers for intensive unit review. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 49. Our base map from Footscray studio with usage of QGIS and Adobe Illustrator. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 47. Mapping for implementation plans in Footscray Project. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 51. Mapping issues and opportunities for Footscray project. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

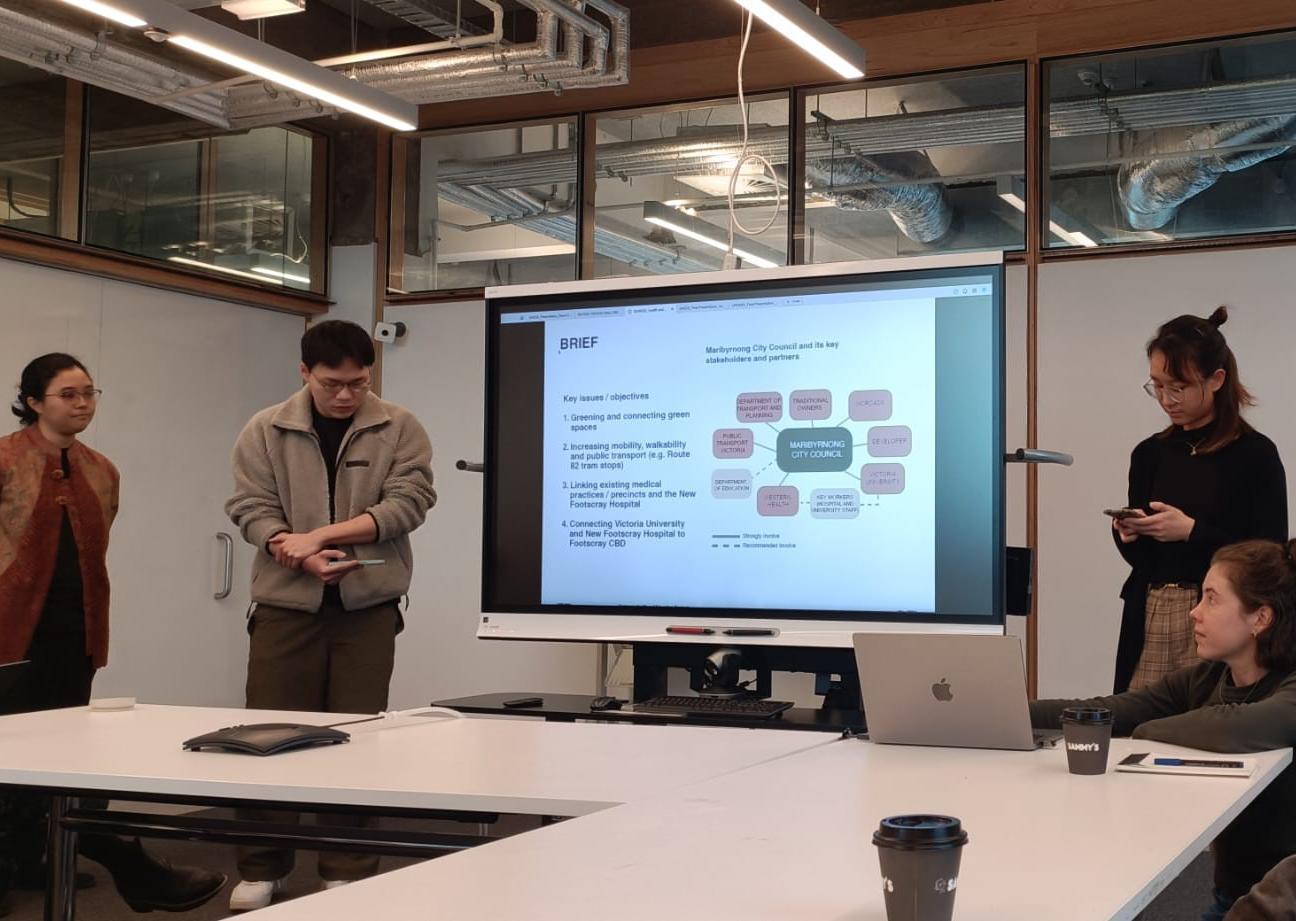

4.4 PRESENTATIONS

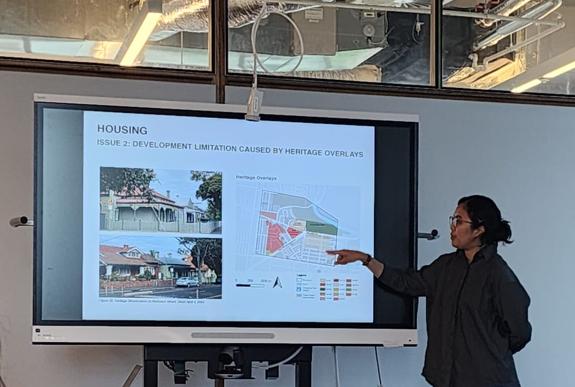

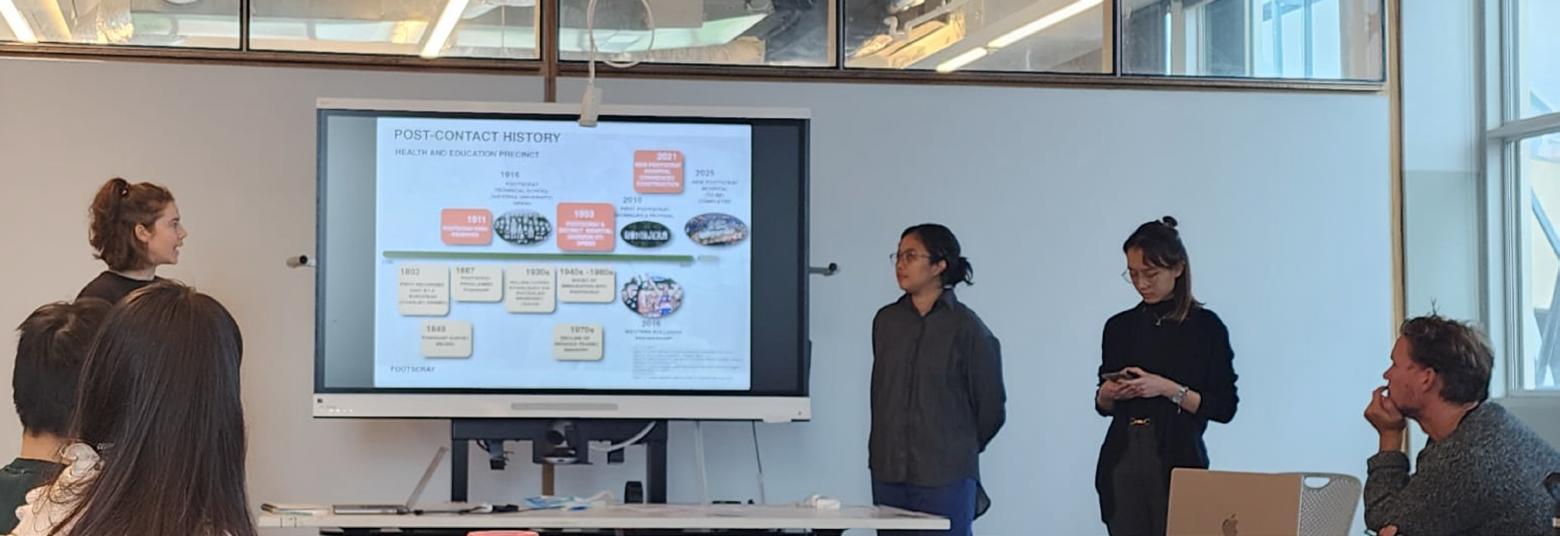

Presenting is one of the most important skills of being a planner as it makes them truly a facilitator for all relevant stakeholders. In addition to increasing confidence and public speaking skills, presenting also demonstrates how planners are able to curate materials and findings from their work into a concise message to reach their target audience properly.

Presenting is a chance for professional planners to be able to prioritise what key messages they want to deliver to their audience.

These units also gave us the opportunity to present the results of our collaborative group work from the two week intensive studio to Maribyrnong City Council officers and other panel guests.

Following the presentations, the panel also provided valuable and insightful feedback on the presentations. This feedback then enabled us to refine our thinking in planning. This style of presentation, which is closely aligned with how urban professionals may be required to present to clients and stakeholders, is what makes the design studio at Monash University stand out for students who aim to pursue a career as an urban professional.

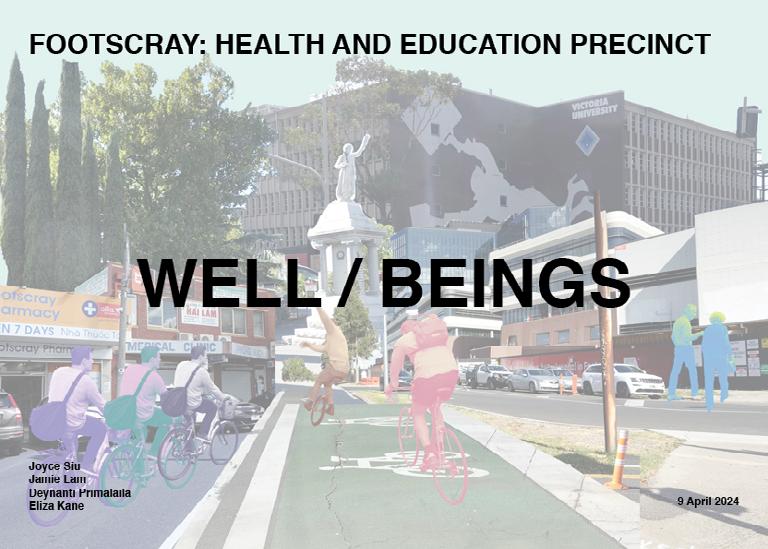

Figure 52. The cover of our presentation. Image credit: Joyce Siu and Eliza Kane.

Figure 55. Eliza (left) presenting history of Footscray regarding health and education precinct to Maribyrnong City Council officer (right). Image credit: Rochelle Fernandez.

Figure 53. Deyna presenting issues of housing in the precinct. Image credit: Rochelle Fernandez.

Figure 54. Extracts of our presentation describing issues and opportunities of the housing theme in the precinct.

STUDENT REFLECTIONS

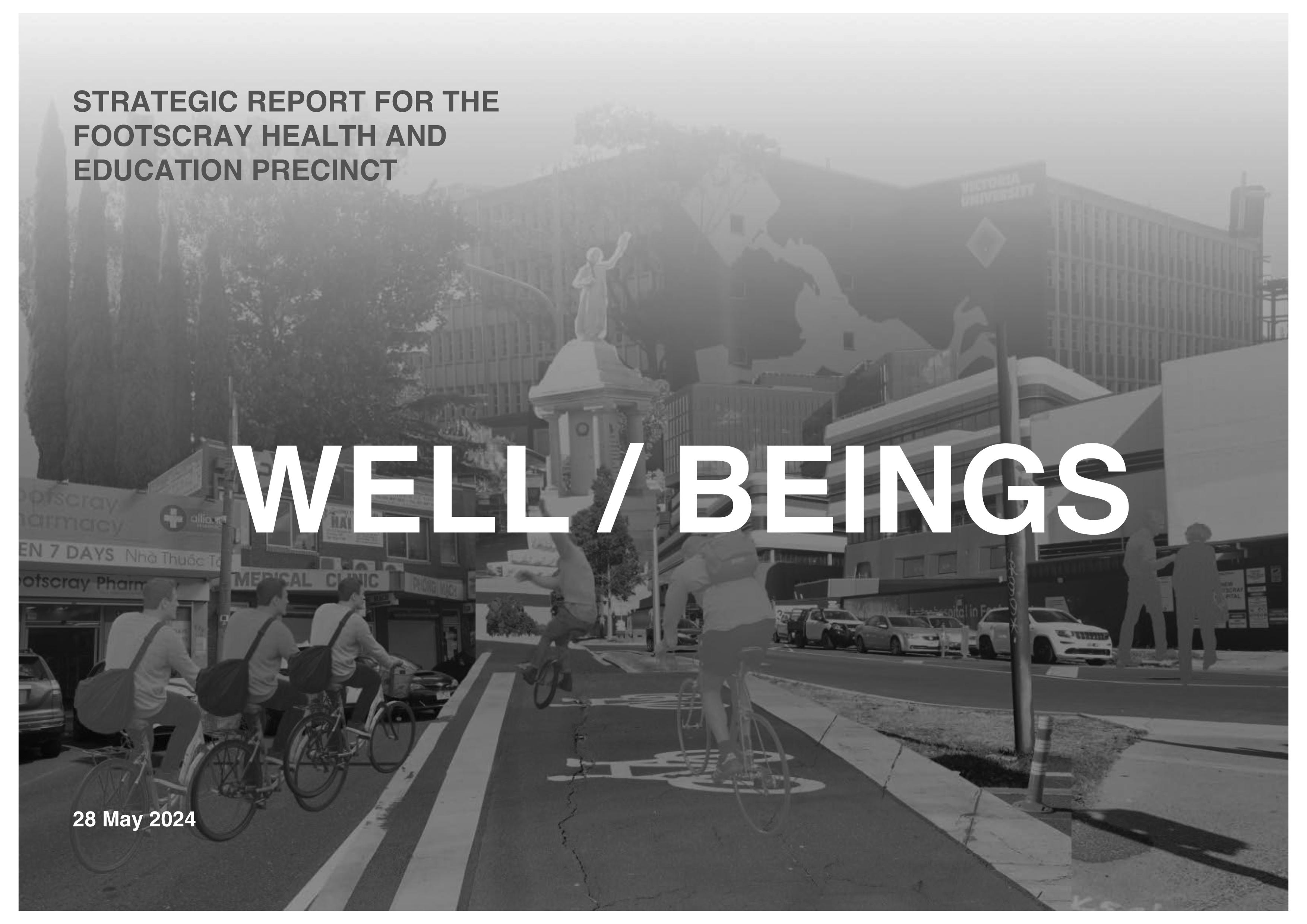

This Chapter 5 (Student Reflections) sets out the key outcomes from the Compact City design studio, a summary of our final studio report - WELL / BEINGS - and a reflection on the design studio from each of us.

Figure 56. Front cover of final Design Studio report. Image credit: Joyce Siu and Eliza Kane.

5.1 KEY OUTCOMES - STUDIO

Key learning outcomes and highlights from the Compact City design studio include:

• Experiencing strategic planning progress: from spatial and context analysis, to developing strategic plans and devising catalyst projects for urban environments, we have begun to develop fundamental practical skills required as emerging urban professionals.

Acquiring ways of thinking and skills as urban planners and designers through learning from each other, from professionals and our surroundings.

• Learning from one another: not only did we learn from each other’s knowledge and experience when working as a group, but our learning was also enhanced by presenting to each other as we were being exposed to alternative methods to develop plans and express ideas.

• Observing surroundings: in addition to lectures, observations from daily life are also meaningful in helping ourselves to explore potential opportunities in urban planning. For example, observing the design of tram stops can inspire ideas for improving active transport infrastructure in the future.

• Liveability is more than just housing: besides the consideration of housing provided, liveable cities are comprised of various elements which make them socially viable, culturally vibrant and environmentally friendly. Public realm, transport, built form and land uses are all factors which, when designed and implemented effectively, contribute to the liveability of the built environment and the wellbeing of the natural environment and community.

Figure 57. Highlighting the key moves of the catalyst project. Image credit: Eliza Kane and Jamie Lam.

Figure 58. Mapping out all strategic actions for different elements along Droop Street as catalyst project. Image credit: Jamie Lam.

5.1 KEY OUTCOMES - STUDIO REPORT

The final design report enabled us to consolidate our learnings and investigations from the semester and communicate our vision for Footscray’s Health and Education precinct.

Report is a showcase for urban professionalism by communicating and exercising the vision of the planning and design.

The final report for the design studio combines the final vision, strategies and actions and implementation plans for Footscray’s Health and Education precinct. Building on the work in the first half of the semester to investigate and understand the context and issues and opportunities within the Health and Education precinct, we developed our ‘WELL / BEINGS’ vision. This vision guided the documented strategies and actions for transport and connectivity, landscape and ecology, housing, culture and activation to create a more liveable Footscray. These actions were then set out in an implementation plan, which included a catalyst project which combined a number of the targeted actions for the precinct.

Preparing the final report for the design studio helped us to learn about the concept and role of compact cities and how this form of urban planning and design can contribute to liveability. In researching and developing the contents of the report, we gained a better understanding of the different elements of the liveable cities. While appropriate and affordable housing stock is critical, other ‘layers’ such as a complete public and active transport network, public realm, urban greenery and cultural interaction - including with Indigenous Traditional Owners and local and international residents - play a vital role in enhancing the areas in which people live.

Figure 59. Collage of proposed development in the health and education precinct. Image credit: Joyce Siu and Deynanti Primalaila.

Figure 60. Strategies for archiving more liveable Footscray. Image credit: Eliza Kane.

5.2 STUDENT REFLECTIONS

Urban planning and design challenged my interior architecture background with its complex systems of interconnected layering components, diverse policies and stakeholders, and the powerful link between design and public good. My initial skepticism vanished – learning to be an urban planner means learning not to be naive.

Urban planning and design is a process of intricacy consisting of layering dimensions.

I also learned that different countries’ systems for urban planning are very influential. In Indonesia, urban planning regulations are not strictly implemented, resulting in significantly fast development but inconsistencies in its built environment’s identity. In Victoria, a planning and design process that focuses on results over specific terms is crucial. In Victoria, a planning and design process that focuses on results over specific terms is crucial. This means that development may take a long time, but the intention of this system is to carefully maintain the DNA and the sustainability of the place and the society.

Collaborating with others is something I have done in my previous academic and professional worlds. However, I have only done this with people of similar backgrounds, considering the exclusivity of the interior and architecture world. Exchanging ideas and collaborating with friends from legal, commercial, geography, and environmental science backgrounds provides a new perspective to my way of thinking about urban planning and design. Urban planning and design is not just large-scale design; it consists of layers with various dimensions that people from diverse backgrounds could even relate to them.

Deynanti Primalaila, June 2024.

Figure 61. Cartesian coordinate diagram of interpreting urban planning and design as layering dimensions. Image credit: Deynanti Primalaila.

5.2 STUDENT REFLECTIONS

Before taking part in this course, although I was familiar with built environment as I have grown up in cities, it was hard to understand the principles behind the planning and designs, how and why communities are shaped by the built environment. The MUPD has given me an understanding of the elements and mechanisms. With this knowledge acquired, I can observe and appreciate the beauty of different neighbourhoods every time when I visit new places.

A great opportunity to understand how to make a better place and enjoy the beauty around us.

With knowledge shared by professionals and comments given by our lecturers, I understand that efforts mean a lot to strategic planning. There are many parties involved in every planning project and detailed studies (case study, context and field visit) are critical to generate quality implementation plans. Yet, it takes long time to see the result of proposed ideas to be applied into real-life. I have learnt to be patient and openminded through the development of strategic plans in our course.

Last but not least, I am so grateful to be a part in my group. Sometimes I could hardly understand the mechanisms of planning in Victoria as it varies a lot from my hometown’s planning system and culture. My group mates helped me brainstorm and gave me ideas and comments all the time when I could not catch up or did not understand the issues or topics. I am so glad to be in such a nice group!

Joyce Siu, June 2024.

Figure 62. Presenting our ideas to lecturers and guests in final presentation. Image credit: Suraya Abd Halim.

Figure 64. Daily observation of streets for enhancing pedestrian experience. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 63. Sharing ideas and observations for constructing the action plans in the precinct. Image credit: Jamie Lam.

5.2 STUDENT REFLECTIONS

In only a short period of time, I have gained an indepth insight into the role of urban professionals and the practical skills employed to drive liveability outcomes in the built environment.

Coming to the MUPD, I had a keen interest in urban planning and design as a subject matter. Shortly after starting the program, it became apparent to me of the limitations of my understanding of the scope and breadth of the role (and impact) of urban planners and designers in shaping our cities and liveability outcomes.

But already in our first semester, I have gained an insight of the role of urban professionals - including from a number of professionals themselves. We have also begun developing a number of practical skills - from policy analysis to physical mapping to preparing design reports and presentations - which urban professionals would regularly employ. This has felt like a marked (and challenging!) shift from my previous academic experiences, where the emphasis was largely on learning and applying theories and principles.

These practical elements of the Compact City design studio and Professional Practice intensive unit, which also include other real world experiences such as site visits, consulting with industry professionals and presenting to professional panel guests, have been a true highlight. Not only has this enhanced my understanding of the practice of urban planning and design, but it has been critical to ground theoretical concepts of urban planning practice and professionals in the real world.

I look forward to continuing this exploration of the practice of urban planning and design and the role of urban professionals - with the group of likeminded, enthusiastic and engaged people that are the MUPD cohort.

Eliza Kane, June 2024.

Figures 65 - 67. Left to right: Eliza, Deyna and Joyce participating in strategies exercise. Image credit: Jamie Lam; MUPD first year students with lecturers, Suzanne Barker and Katherine Sundermann (centre). Unknown creator. Eliza tracing a map. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

5.2 STUDENT REFLECTIONS

For the first semester design studio, I am grateful for this meaningful opportunity to learn about urban planning and design and to work with the support and cooperation of my group members.

From each meeting and revision of our work, we continued to progress and made the direction of a “more liveable” Footscray clearer.

It was a thankful and meaningful period to not only learn about urban planning but to also realise the mutual support and cooperation among group members.

Even though the process was complicated and required a lot of time to collect information, when I saw the results, I felt a great sense of accomplishment and learned a lot from it. The application of software - InDesign, QGIS, Illustrator etc..., the way of thinking, the way of making reports, Victorian planning system, are all what I have gained from this special course!

Of course, I have made mistakes in the production of projects but this experience and the assistance of my team members has helped me learn from this. However, I also learn how to find problems and find ways to solve them, and also learn how to check and confirm repeatedly to improve the quality and accuracy of the results. I think this will enable me to face difficulties with a more positive attitude in the future.

I really like the process of working together for the goal, even though we have different things going on in our lives and everyone is busy. But when it is necessary to discuss, everyone cooperated with and helped each other. I feel very lucky to have such a good group of partners.

Jamie Lam, June 2024.

Figure 68. Left to right: Jamie, Deyna and Eliza. Discussing in strategies exercise. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

Figure 69. Left to right: Joyce, Deyna and Eliza. Discussing in strategies exercise. Image credit: Jamie Lam.

The MUPD has already given us an insight into and experience of the role and responsibilities of urban professionals - and we are only just at the beginning!

Through the combination of the Compact City design studio and the Professional Practice intensive unit, we have gained practical skills and an understanding of the strategic and regulatory context of urban planning and design and how this contributes to improved liveability outcomes in the built environment.

We hope that this publication has provided a valuable perspective of the MUPD and our experience to date.

But why just take our word for it? Come and experience it for yourself...

Figure 70. Group site visit in Footscray precinct. Image credit: Joyce Siu.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A - STUDENT CONTRIBUTIONS

APPENDIX B - REFERENCES

“United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.” United Nations. Updated September, 2023. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment, figure 24.

*The content of this publication has not been approved by the United Nations and does not reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States.”

Fensham, Patrick. “Compact City - Targeting a More liveable Footscray.” Lecture, Footscray Connectivity Centre, Footscray, March 22, 2024, figure 18.

Fergus, Andy. “The Invisible Hand.” Lecture, Monash University, Caulfield, March 11, 2024, figure 21.

McGauran, Rob. “The Inner West A case for transformation.” Lecture, Footscray Connectivity Centre, Footscray, March 13, 2024, figure 20.

Minniti, Ashley. “City of Maribyrnong: Issues and opportunities.” Lecture, Monash University, Caulfield, February 27, 2024, figure 19.

Unless otherwise stated, all images and photographs in this publication were created by Eliza Kane, Jamie Lam, Deynanti Primalaila and / or Joyce Siu.