Movin the Maine ’ ’

TOWNSHIP ANALYSIS

Planning Project 3: Transforming city

Master of Urban Planning and Design

Monash Univiersity

Eliza Kane

Hillary Namitala

Rochelle Fernandez

June 2025

Planning Project 3: Transforming city

Master of Urban Planning and Design

Monash Univiersity

Eliza Kane

Hillary Namitala

Rochelle Fernandez

June 2025

Improving regional mobility and accessibility go beyond strategies for transport networks and transport infrastructure. Where people live impacts their ability to access transport services, as well as other essential amenities and services to meet daily needs. It can also exacerbate the consequences of inadequate transport networks –resulting in an increase in private car ownership and usage.

So, what if increasing housing density could be the driver to justify greater investment in mobility options and community infrastructure and amenities?

Housing as a key to unlock regional mobility and spatial accessibility

Historical, social and spatial analysis and research indicates that housing location and typologies in the Castlemaine Township inhibits spatial accessibility.

Examining the current housing stock, as well as existing community infrastructure and transport and mobility options, provides an insight into constraints and the challenges the region is facing - but also highlights opportunities to deliver housing in a way that can also improve spatial accessibility.

To undertake this analysis, the Castlemaine ‘Township’ scale has been reframed as a collection of

neighbourhoods. Focusing on specific neighbourhoods enables a deeper analysis and understanding of place. This provides an insight into the strategies and actions which could be deployed to improve spatial accessibility in response to the different categories of neighbourhoods which are characteristic of regional townships.

Rethinking the planning approachProject Postcode

Project Postcode - as a planning project - takes a holistic view of and approach to enhancing spatial accessibility. It centres on housing as a resource to provide opportunities for neighbourhood mobility, and as a lever to drive investment in community infrastructure.

This report summarises the research and analysis of the Castlemaine Township and key ‘neighbourhoods’the Castlemaine town centre, McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill, which provide an evidence-base foundation for Project Postcode.

It details how the planning project is informed by and responds to stakeholder and community engagement, and how experiences in Castlemaine have informed the Project Postcode as a planning project.

Finally it details the Project Postcode ‘toolkit’ - strategies and actions covering housing, neighbourhood mobility, community infrastructure and environment and climate resilience - to keep Castlemaine connected.

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners, the Djaara people of the Kulin nation, as the original custodians of the lands and water on which the Castlemaine Township is located.

We pay our deep respects to Indigenous communities and to Elders past and present. We recognise and value the ongoing contribution of Indigenous people to the sustainable development that supports our communities.

The Castlemaine Township is situated on Dja Dja Wurrung Country— the lands of the Djaara people, who have administered care for tens of thousands of years. These lands, waters, skies, and stories are living, interconnected systems, deeply embedded with meaning and cultural significance.

Here, we focus on ‘Listening to Country’—an act that goes beyond a symbolic gesture. It is an active process of paying attention, of learning from the knowledge embedded in landscape and memory, and of rethinking how we relate to the places we live and plan for.

“Country is known ...it has its stories that are taught, learned and told. ...It has its rituals. It can be painted, ... and one can care for and love it...”

-

Michael Dodson. (Excerpt from Hromek, 2020)

The group had the privilege of doing a walking on Country tour with Uncle Rick Nelson, a respected Aboriginal Djaara Elder and cultural leader in Castlemaine. Uncle Rick’s stories and reflections offered a powerful lens through which to see the town’s past and future. He shared insights about the ecological and cultural changes the Castlemaine Town and surrounding landscapes had undergone, especially during the Gold Rush, and emphasised the importance of water, Country, and kinship and foundational elements of life.

One of the most striking lessons we learned was about the relationship between Castlemaine’s development and its waterways. Creeks and waterholes are not only ecological lifelines but also deeply spiritual and cultural sites for the Djaara people. The development of Castlemaine during and after the Gold Rush disrupted these systems, often irreversibly. Creeks were ‘shifted’ to make place for roads and infrastructure.

‘Upside down’ Country

Uncle Rick spoke about the landscape being turned “upside down”—a phrase that powerfully captures the impact of gold mining, which quite literally involved digging through Country in search of gold. This violent inversion of the land had long-lasting effects on both ecological systems and cultural heritage (eg. the sinkholes).

The concept of ‘upside down Country’ resonates deeply with the work of scholars and designers such as Dr. Danièle Hromek, who writes that engaging with Country is about learning from it as a teacher, rather than treating it as a resource.

In her article ‘An Approach for Engaging with Country’, Hromek (2020), foregrounds Country as a living entity, and that design and planning practices should seek to understand and respond to its values, stories, and needs rather than imposing deliberate frameworks upon it—shaping development to respect and regenerate land and not the other way around.

In planning for Castlemaine’s future, while Project Postcode focuses on connecting people and building communities, it also seeks to link people back to place and develop an identity that recognises indigenous heritage. In doing so, Project Postcode hopes to contribute to a vision of Castlemaine that learns from past experiences and respects Country’s never-ending presence.

Lastly, listening to Country is also about humility. Recognising that Aboriginal knowledge holders have stewarded these lands far longer than any other settlers is essential along with acknowledging their understanding of how to live sustainably with Country. To plan responsibly, we must listen to these stories—not just with our ears, but with our minds and actions.

Planning analysis

History and context

Social and spatial analysis

Mobility and transport analysis

From the community and site observations

Learning from elsewhere

Project

Overview: Project Postcode

Housing strategy

Neighborhood mobility strategy

Community infrastructure strategy

Project Postcode in place: McKenzie Hill case study

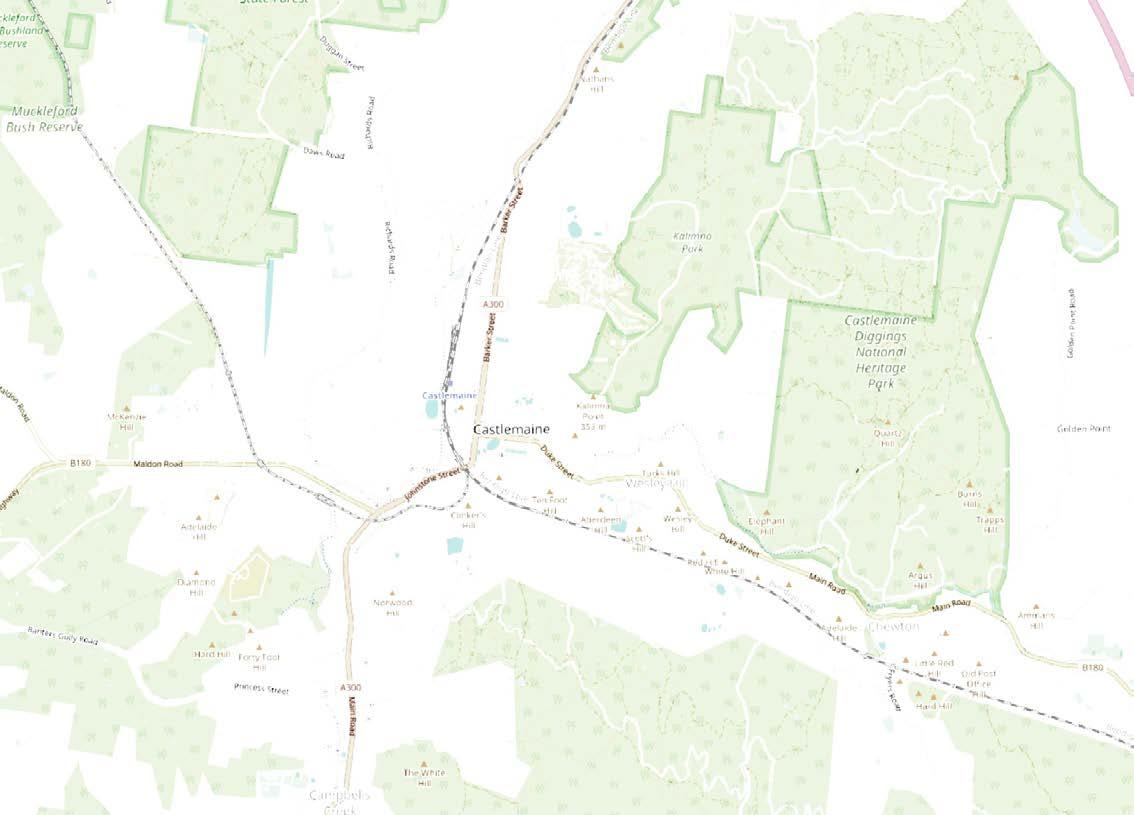

The Castlemaine Township is the primary urban and economic centre of Mount Alexander Shire, encompassing the central town of Castlemaine along with the neighboring suburbs of Chewton, Campbells Creek, McKenzie Hill, Golden Point, and Moonlight Flat (see image above).

As per ABS (2021), population of the Castlemaine Township region was recorded at 11,352 people (accounting for over 55% of the Mount Alexander Shire population). This highlights the

CastlemaineTownship scale map (image credit: ABS (2021), Rochelle Fernandez, using QGIS and Nearmap)

critical role of the area in supporting the daily needs of more than half the Shire’s residents.

The significance of the township scale lies in its spatial and functional connectedness with its surrounding neighborhoods. It represents not just a population core, but a shared catchment for education, health services, employment, retail, and a variety of cultural activities. The towns constituting the township are distinct yet interdependent on one another, contributing to a collective urban identity.

‘Centreless’ towns

Historical and contemporary urban development has influenced the urban layout of the Castlemaine Township, which focuses on the Castlemaine town centre as its core ‘hub’. Investment in the town centre has led to commercial and community facilities largely being confined in a limited area of the Township. Over time, residential areas have emerged spreading radially out from the town centre. Subsequently, these residential areas lack the amenities to create ‘centres’ and build strong place identity and community connections.

Another key planning issue concerns housing - specifically where it is located around the Castlemaine town centre, and the diversity (or lack thereof) of housing which is being delivered in the Castlemaine Township.

Despite planning policy direction to increase housing diversity and encourage infill development (Mount Alexander Shire Council, 2004), planning has not achieved the desired outcomes. This has flow-on effects for mobility and spatial accessibility within the region.

Development patterns influencing formation of Centreless Towns like McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill (image source/ credit: Geoscape (n.d.), DEECA (2025), ABS (2021), DTP (2024). Rochelle Fernandez, using QGIS and Nearmap)

LEGEND

Roads/ Transport routes 0 km 1 km

Creeks

Spatial accessibility

Patterns of urban development and the delivery of housing ultimately impact spatial accessibility within the Castlemaine Township. This is to the extent that a concentration of amenities and services, and lack of appropriate housing, affects the ability of residents to meet their daily needs and reliance increases on private car use to do so.

It is important to recognise that what it means for an area to be ‘well-serviced’ by amenities and essential services in Regional Victoria is not the same as what this may require in metropolitan areas (Regional Cities Victoria, 2025).

Roads/ Transport networks

Education facilities

Recreational open spaces

Community facilities

Health facilities

Train Station

Grocery/ shopping

Sports facilities

Despite this, improving spatial accessibility— by bringing more services to people in place— can reduce the burden of inadequate transport systems and the need to rely on private car use within the region. Simultaneously, this can be used to strengthen community connections by bringing more people together, closer to where they live.

Planning for regional townships, as an area centering around a commercial hub, rather than as a collection of neighbourhoods, influences the location and diversity of housing, limits spatial accessibility, and exacerbates regional mobility issues.

The symptoms of this planning approach have broader implications — affecting social and community ties and the ability to create place identity and connection to place.

Project Postcode is a planning initiative focused on addressing the challenges of spatial accessibility and housing development across the Castlemaine township. Drawing from research into the region’s planning history, transport networks and connectivity, and housing pressures, the project responds to the emergence of ‘centreless towns’— neighborhoods devoid of a clear identity, accessible services, and infrastructure connectivity.

At the core of project is the idea of ‘Housing as a resource’—housing as a catalyst for change. Rather than viewing housing solely as a response to demand, the project repositions it as an asset to shape better planning outcomes.

The project also recognises the importance of reconciliation with ecology. It advocates for a planning model that not only improves connectivity and accessibility for its residents, but also restores and strengthens the built environment’s relation to water and landscapes, previously affected by colonial and extractive land uses.

In considering restoring relations to the environment while planning for liveability, Project Postcode emerges as a holistic approach to enhancing both community well-being and spatial accessibility, giving neighborhoods a renewed identity and a stronger connection to services, people, and place.

Project Postcode envisions a connected Castlemaine by strengthening neighbourhood identities, enhancing mobility, and improving spatial accessibility—ensuring that all residents, regardless of location, are linked to place, each other, and the broader township.

The implementation of Project Postcode is based on a set of tools consisting of tactical urban planning and design interventions for the township to keep Castlemaine connected This ‘toolkit’ is centered around four interrelated elements:

1. Housing:

The key driver of change; increasing affordable and accessible housing options that support inclusive growth while serving as anchors for neighborhood identity.

2. Neighborhood mobility:

Improving spatial accessibility through diverse mobility options, better transport links, walkability, and local access, enabling residents to connect easily to services, and each other.

3. Community infrastructure:

Strengthening local infrastructure to build resilient, well-serviced neighborhoods that can function as local centres and enhance residents’ quality of life.

4. Environment and climate resilience:

Integrating ecological restoration and climate-sensitive planning to support both environmental health and community wellbeing.

While each of these themes addresses distinct challenges, they are designed to work together to deliver holistic and adaptable planning outcomes. Project Postcode aims to implement these strategies across different township neighbourhoods, ensuring tailored yet cohesive responses to local needs.

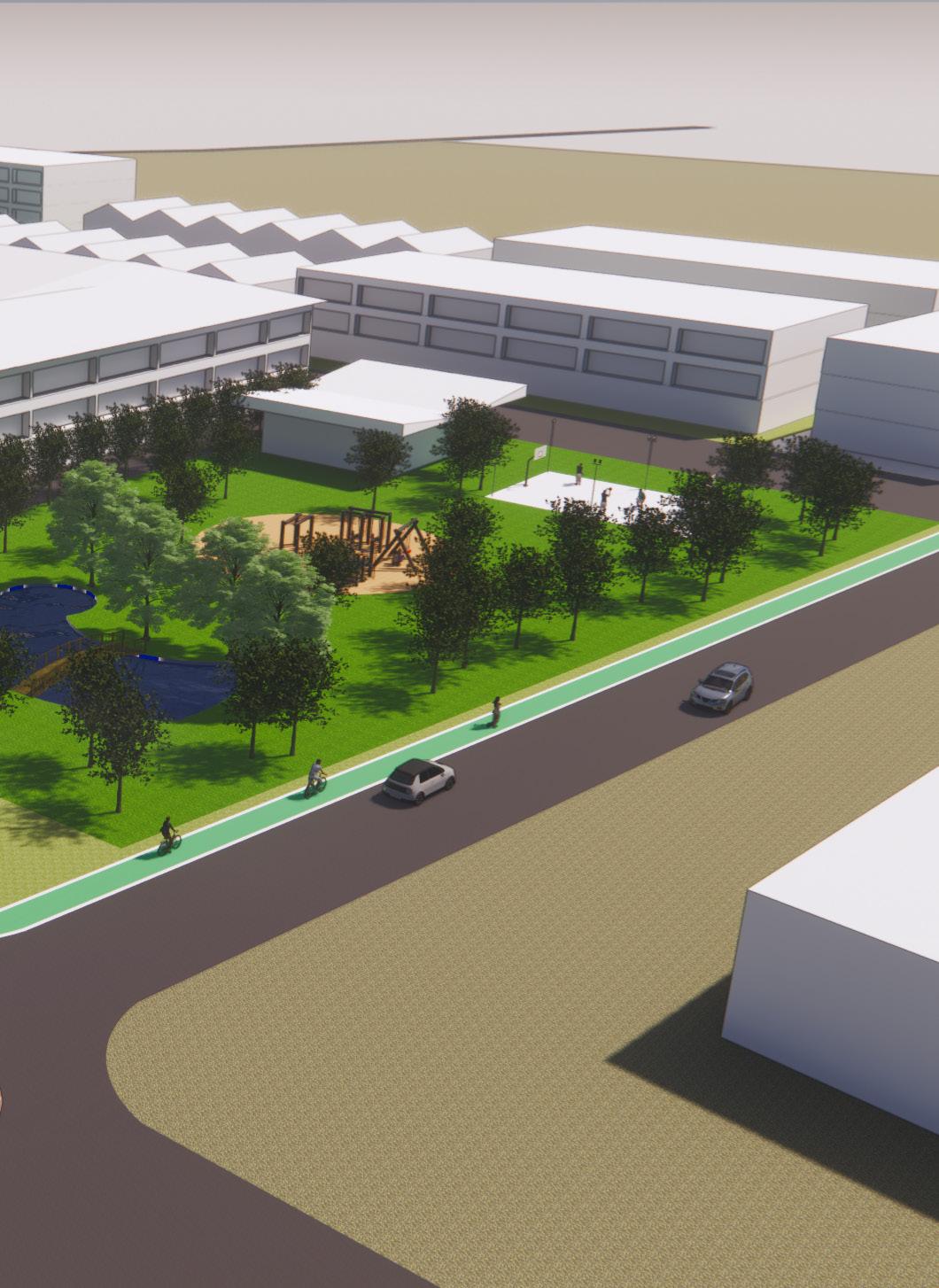

Diverse housing typologies to increase density, facilitate aging in place, etc.

Public open green space with allocations for different recreational acitvities.

Shared mobility options to support diverse and sustainable mobility and ease household transport costs.

Separated bike paths and footpaths with nature strips to encourage and enhance active mobility.

In-between shared open spaces to facilitate low-traffic neighborhoods and access to nature.

Multipurpose community facility to encourage community activities and social relations.

Improved bus services to optimise public transport networks and enhance accessibility /mobility.

Constructed wetland as an element of WSUD* to restore ecological connections.

This report is comprised of the following:

1. Planning analysis - this section details the findings of the historical, social and spatial analysis. It first sets out the research and analysis which covers the broader Castlemaine Township. Second, the analysis focuses in on the different study areas within the township - being the Castlemaine town centre, McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill - to understand the different conditions, constraints and opportunities that are present in these study areas.

2. What we learned - this section sets out the insights gained in a real life context (community engagement and site observations) as well as from planning concepts and case study and precedent projects. It describes how these have informed the direction and outcomes of the planning project.

3. Planning Project: Project Postcode - finally, this section details the planning project and the Project Postcode Toolkit, along with strategies and actions for implementing the toolkit.

From top: Map of Castlemaine Township produced in research and analysis phase (image source: Rochelle Fernandez); Project Postcode group engaging with local stakeholder group representatives (photo credit: James Whitten); Mundingburra Housing Project used as a precedent (photo credit: Andrew Rankin, n.d.); Project Postcode new housing model (image source: Rochelle Fernandez)

Phase 1

Preliminary research February

Phase 2 Community engagement

Phase 3

Scope and refine the project

Phase 4 Present the project

Phase 5

Finalise the project

The report details the process and the activities undertaken over a number of months to research, understand, scope and refine the planning project.

The content of the report outlines and reflects the holistic approach adopted by the group to develop a deep understanding of not only the symptoms of the mobility and accessibility issues that regional towns such as Castlemaine

face, but the underlying causes contributing to these issues.

This is critical in order to develop rational and workable, but still ambitious and innovative, solutions to improve regional mobility and accessibility.

The planning analysis investigates the development patterns and spatial inequalities across Castlemaine’s Town Centre, McKenzie Hill, and Wesley Hill to understand how different planning legacies are continuing to shape urban outcomes. These three areas are selected as case studies due to their contrasting urban conditions, Castlemaine as the established civic and commercial centre, Wesley Hill as a peripheral area with emerging community needs, and McKenzie Hill as a growing residential fringe lacking a defined centre.

The analysis is framed around four key themes: historical influence, transport and mobility, housing patterns, and environmental and climate challenges. Through this lens, the analysis explores how infrastructure distribution, environmental constraints, and legacy growth patterns are producing uneven access to housing, services, and transport.

It also examines why development is unfolding in particular ways, what environmental risks and planning controls are shaping growth, and where accessibility opportunities are arising through infill and greenfield diversification. This work underpins Project Postcode by revealing how gaps between housing, services, and jobs drive affordability and access issues, and points to targeted solutions for each area.

The Commercial Hub

The Growth Area

The In-between

Town formed quickly around mining camps and trade routes.

1900 1850

Infrastructure such as roads and waterways laid the urban fabric.

1950

Adaptive reuse of old buildings for cafes, galleries, and local businesses.

Castlemaine reemerges as a creative and cultural hub with strong community identity.

The towns developed organically around the mines unlike planned towns therefore early roads, buildings, and services were positioned near creeks and diggings, rather than following a structured layout. The mining sites were created around elements of the natural landscape which left a gap in the urban fabric of the townships (Harper, 2016).

The town’s expansion was dictated by gold-bearing areas, leading to irregular land subdivision and fragmented property ownership, which still impacts development today.

From top (Image source: Parks Victoria, 2024; State Library Victoria, n.d., Goldfields Guide Victoria, n.d., Hillary Namitala)

Castlemaine’s rectilinear grid, enabled clear land division and zoning, shaping the town’s orderly structure today.

Map showing Castlemaine’s settlement patterns (image credit: Geoscape (n.d.), DEECA (2025), Hillary Namitala using QGIS)

McKenzie Hill developed as part of regional growth and housing expansion. Its pattern reflects contemporary suburban development.

Map showing McKenzie Hill’s settlement structure (image credit: Geoscape (n.d.), DEECA (2025), Hillary Namitala using QGIS)

Wesley Hill developed along the route to the Chewton Goldfields, forming a linear settlement around facilities established along the road.

Map showing Wesley Hill’s settlement structure (image credit: Geoscape (n.d.), DEECA (2025), Hillary Namitala using QGIS)

Creeks Rail line

Arterial Road

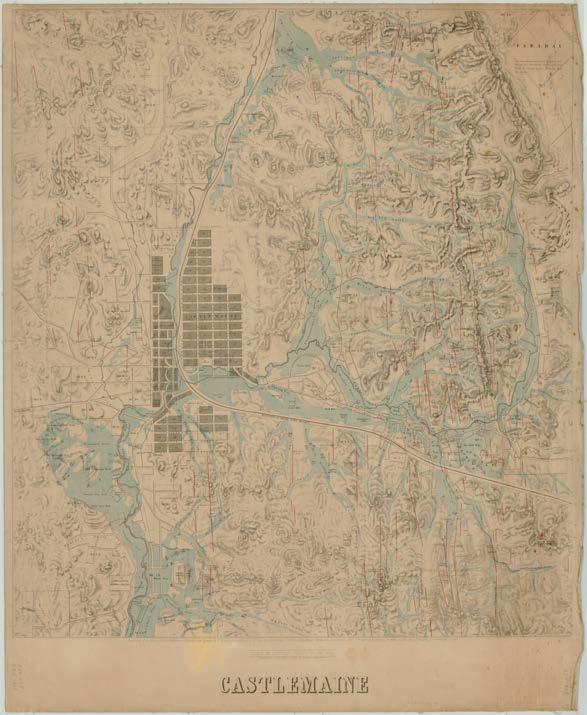

A historic map of Castlemaine in 1890 (image source: State Library Victoria, n.d.)

Castlemaine’s urban development has long been shaped by its natural environment, with factors like topography, environmental risks, and past mining activities creating both opportunities and constraints. The town’s settlement patterns, infrastructure, and land use have had to adapt to challenges such as flooding, bushfire risk, and landscape fragmentation, often leading to an uneasy balance between growth and environmental preservation.

Historical mining and development disrupted natural drainage in Castlemaine, heightening flood risk. Climate change has worsened this by increasing extreme rainfall, complicating urban planning (Castlemaine Gold Rush Relics, 2025).

In contrast, McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill, located on the fringe, are exposed to bushfire risk due to their proximity to dense bushland and vegetated ridgelines. These areas developed through incremental subdivision and housing on the urban-rural fringe, often without coordinated fire management or access planning. The result is a vulnerable urban edge, where bushfire overlays restrict further development and pose challenges. As Castlemaine continues to grow, managing these risks while supporting sustainable development will be essential to ensure long-term resilience and safety.

Flooding and bushfire poses risks for urban development, and highlights considerations for future development

Flooding overlay Bushfire Management Overlay Environmental Significance Overlay

Significant Landscape Overlay

Demographic characteristics and trends, including age, family composition and needs for assistance, provide key insights into the diversity and needs of the current and future population - in particular, needs for housing, accessibility options and community infrastructure and essential services.

Age profile

The Castlemaine Township has an older, aging population. This is reflected in the population’s median age of 50 years old, and the dominant age cohort being persons aged between 65 to 69 years old (ABS, 2021).

Family composition

The dominant family structure is couples with no children (ABS, 2021) (refer figure overleaf), being almost 50% of all families. This is consistent with what would be expected of a region with an the aging population. Relevantly, however, a significant proportion of families have children, of which more than 18% are single parent families (ABS, 2021).

Needs for assistance

In line with the trend of an aging poulation, Castlemaine Township has experienced an increase in the proportion of the population recording a need for assistance with core activities (ABS, 2016; ABS, 2021).

Census data highlights a potential relationship between age and increasing needs for assistance to undertake daily activities, with more than 50% of people requiring assistance being 65 years and older (ABS, 2021).

Icons sourced from The Noun Project, Nico Bokenkroger, Bailey, Kevin and Adrien Coquet, accessed 23 March 2025

Castlemaine TownshipDemographic Stats (Source: ABS, 2011, 2016, 2021 and 2024)

50 years old (median age)

Largest increase in age profiles (2011 - 2021): 65-69, 70-74, 95-99

Increase in % of population with needs for assistance for all Castlemaine Township localities (2016 to 2021)

Almost 50% of family structures are couples with no children

>18% of families are single parent families

Castlemaine Township has an aging population and a diversity of family structures

Change in age profiles (over 10 years) in Castlemaine Township localities: age profile data highlights that between 2011 and 2021 there has been an increase in older age cohorts, specifically 65-69, 70-74 and 95-99 years old. At the same time, younger demographics, between 1519 and 20-24 years old have decreased.

Graph of Change in Age Profiles in Castlemaine Township (2011 - 2021) (image source: Eliza Kane, data source: ABS, 2011 and 2021)

Change in Age Profiles (%)

Family composition across the Castlemaine Township: the dominant family composition in almost all localities within the Castlemaine Township is couples with no children.

Graph of family composition in Castlemaine township (2021) (image source: Eliza Kane; data source: ABS, 2021)

Analysis of dwelling typologies, dwelling structure, household composition, and building approvals indicate that the current (and future) housing stock does not meet the diversity or needs of the current and future population of the Castlemaine Township - contributing to a housing mismatch.

Separate private houses comprise the majority of housing typologies in the Castlemaine township. In certain localities, this proportion is greater than 90% - for example, in Chewton, McKenzie Hill and Moonlight Flat (ABS, 2021). Three and four bedroom houses also make up a majority of residential dwellings in the Castlemaine township (~66% of all housing stock) (ABS, 2021).

Lone and two-person households are a significant proportion of households within the Castlemaine Township (ABS, 2021), with lone person households comprising as high as 39.7% of all households in Castlemaine.

Despite the mismatch between existing dwelling structure and household composition, building approvals data reflects that this trend will continue.

92% of building approvals in the broader Castlemaine region were for separate private houses. This is compared with only 8% of building approvals for dwellings being other private residential development (ABS, 2024).

Icons sourced from The Noun Project, Atif Arshad, Adrien Coquet, PC-SSH, and Sophia, accessed 23 March 2025

Castlemaine TownshipHousing Stats (Source: ABS, 2021 and 2024)

~34.3% of households are lone person households

3+ bedrooms is the dominant dwelling structure

~85% of housing stock is separate dwellings ~92% of building approvals for private houses between 2019-2024 were single separated dwellings

Household composition vs dwelling structure: lack of appropriate housing for lone person and twoperson households, and an excess of three and four bedroom dwellings.

Graph of household composition vs. dwelling structure in Castlemaine township, 2021 (image source: Eliza Kane; data source ABS, 2021)

Building approvals (dwellings): number of building approvals for dwellings between 2019 and 2024 have predominantly been for single, separated dwellings (houses).

Graph of building approvals for private dwellings (houses and excluding houses in Castlemaine SA2) 2019 - 2024 (image source: Eliza Kane; data source: ABS, 2024)

The result of the housing mismatch is a housing stock which is inappropriate and expensive for many people in the Castlemaine Township region - for example, houses that are too big and therefore unaffordable for people to purchase, rent or otherwise continue to live in.

The housing mismatch is likely to have contributed to a significant proportion of households within the Castlemaine Township experiencing mortgage and rental stress - which arises as a result of housing costs being a significant portion of household income (REMPLAN, 2025).

Affordable housing sold and rented is declining across Castlemaine (including Moonlight Flat and McKenzie Hill) and the Mount Alexander Shire more broadly (REMPLAN, 2025), reflecting a lack of availability of affordable dwellings within the region.

Economic and social consequences of the housing mismatch

The housing mismatch and lack of appropriate and affordable housing have wide ranging consequences, include:

• Inability for local employers to attract and retain staff (D’Agostino, 2022).

• Childcare access, (which has implications for ability to work or study) (Mount Alexander Shire Council, 2024).

• Introduces systemic barriers to economic participation and community ties (Mount Alexander Shire Council, 2024).

Region

Mortgage and rental stress: the housing mismatch contributes to high rates of people experiencing mortgage or rental stress.

Graph of mortgage and rental stress in Castlemaine township localities, 2021 (image source: Eliza Kane; data source: REMPLAN, 2025)

Affordable dwellings sold: the graph indicates that there has been a general downward trend in the number of affordable dwellings sold in Castlemaine, Chewton and Campbells Creek.

Graph of number of affordable dwellings sold - MAS vs Castlemaine, Chewton and Campbells Creek, 2015-2024 (image source: Eliza Kane; data source: REMPLAN, 2025)

Affordable rentals: the graph indicates that there has been an increase in the number of affordable rentals from 2021 to 2022. However, this number has been declining since.

Graph of number of affordable rentals - MAS vs Castlemaine, Chewton and Campbells Creek, 2015-2024 (image source: Eliza Kane; data source: REMPLAN, 2025)

Significant efforts are being made within the Castlemaine Township and broader Mount Alexander Shire region to address the housing mismatch, and the symptoms and consequences of this issue (such as housing affordability.

Initiatives are being undertaken by community, non-profit organisations, as well as the local government. This covers both policy and strategic planning interventions, as well as facilitating and delivering new models of housing to improve diversity of housing stock and affordability for Castlemaine residents.

Examples of these initiatives include:

• Housing affordability strategies developed Mount Alexander Shire Council, as well as community organisation, My Home Network.

• Delivering affordable housing on Council-owned land.

• Establishment of charitable trust to hold affordable housing in perpetuity.

• Private and community-led housing developments, which have a focus on community and sustainability, such as The Paddock and Munro Court.

From top: My Home Network (image source: Midland Express, 2022); Proposed Council-led affordable housing site (image source: Google Street View, accessed June 4, 2025); Wintringham affordable housing in Castlemaine (image source: Wintringham, accessed June 4, 2025); Munro Court sustainable housing development (photo credit: Andrew Lackey, n.d.); The Paddock Ecovillage in Castlemaine (image source: Bush Project, n.d.)

Current and future residential development across Castlemaine Township

In addition to innovative housing initiatives being implemented in and around the Castlemaine Township, housing in the future will be supplied by way of greenfield development in areas such as McKenzie Hill, and Campbells Creek. Greenfield developments are expected to supply 700 lots for housing across Mount Alexander Shire (Mount Alexander Shire Council, 2023).

This reflects the reality that infill development will not be able to meet all regional housing needs and that developing outside of town centres has different implications for regional areas, compared with metropolitan areas (Regional Cities Victoria, 2025).

However, careful planning is required to ensure that continuing to develop housing outside of town centres does not compromise mobility and spatial accessibility for future residents.

Map of current housing stock and residential areas under development in Castlemaine Township (image credit/ source (above): Geoscape (n.d.), DTP (2019, 2024), Mount Alexander Shire Council (2023), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez, using QGIS NearMap, )

An analysis of transport and mobility patterns within the Castlemaine Township show significant gaps in both public and active transport networks. These deficiencies are particularly evident in the outer, centreless towns such as Wesley Hill and McKenzie Hill, where limited spatial accessibility is further strained by the region’s carcentric development patterns.

As per ABS (2021) Census data, 54.2% of residents travelling to the Castlemaine Township for work rely on private vehicles, and 92% of households in the region reported owning at least one car. While these numbers represent only a few parameters/ measures (Place of Work data), assumptions can be made to the general characteristics of high car-dependency in the region. This also reflects the nature of public transport service available. Infrequent local bus operations (refer to map on next page) render them inadequate to meet mobility needs. Similarly, with the active transport networks, while strategic cycling routes are present within Castlemaine, they often lack continuity, and do not extend reliably to the outer towns. This coupled with road safety concerns and the absence of essential infrastructure such as bike storage or parking, makes active transport less viable, further exacerbating spatial accessibility.

Another implication of the inadequacy of transport networks is the subtle pressure on informal modes of mobility led by neighbors and the community, such as car-pooling and community-run buses. While these forms of transport help bridge the gap to some extent, without appropriate measures to make them reliable, they risk becoming unsustainable or equitable long-term solutions.

A potential to optimise existing networks arises from increasing housing density and stimulating urban activity to activate neighbourhood centres, and make transport networks more efficient. The analysis suggests that improving mobility infrastructure alongside housing interventions can create more accessible and connected communities.

TownshipTransport and Mobility Stats

Source: ABS TableBuilder, 2021, ABS QuickStats, 2021)

92%

Households with at least one car

Travelling to work (Place of workCastlemaine Township)

Deficiencies in PT and AT networks exacerbate spatial accessibility issues.

Bus Route 3 (Castlemaine to Harcourt)

- 3 buses (Mon-Fri), 8 stops

Bus Route 2 (Castlemaine Townloop)

- 5 buses (Mon-Fri), 15 stops

Bus Route 4 (Castlemaine to Maldon)

- 3 buses (Mon-Fri), 9 stops

Bus Route 6 (Castlemaine to Chewton via. Loddon Prison)

- 5 buses (Sat-Sun), 11 stops

Bus Route 5 (Castlemaine to Taradale via. Chewton)

- 5 buses (Mon-Fri), 13 stops

Bus Route 1 (Castlemaine to Campbells Creek)

- 3 buses (Mon- Fri), 25 stops

Regional bus routes Existing cycling routes Proposed cycling routes

Walkability is a crucial aspect of equitable and sustainable neighbourhood design, influencing health, accessibility, and community interaction. In Castlemaine and its fringe areas such as McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill, walkability varies significantly due to differences in urban form, infrastructure investment, and topography. The town centre benefits from a fine-grain street network, flat terrain, and proximity of services, allowing for convenient pedestrian movement.

In contrast, McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill are characterised by dispersed residential development, limited footpath networks, and low street connectivity, which reduce the feasibility and appeal of walking for daily needs.

Catchment analysis indicates that many residents in fringe suburbs are located beyond a comfortable 10-minute (800m) walking distance from key community infrastructure such as childcare centres, libraries, and recreation spaces. Topographic constraints, like hills and uneven paths, further limit walkability, particularly for older residents and those with mobility aids.

The lack of shaded footpaths, lighting, and safe crossings also contributes to car dependency, even for short trips.

Improving walkability in these areas requires targeted interventions: adding continuous footpaths, creating flat and accessible green corridors, and clustering services within emerging neighbourhood centres. These improvements can encourage more active lifestyles, reduce transport disadvantage, and strengthen local ties, especially for families and older residents that consistently highlighted mobility challenges during community engagement sessions.

A 10 minute walkability catchment analysis was undertaken for Castlemaine Town Centre, McKenzie Hill, and Wesley Hill to assess proximity to key community and social infrastructure. In Castlemaine’s town centre, most residents fall within a 10-minute walk of essential services, including the library, restaurants, schools, parks, and civic facilities demonstrating strong access and compact urban form.

10 minute walking catchment of community infrastructure in the Castlemaine township (image credit: Geoscape (n.d.), DEECA (2025), DTP (2025), Hillary Namitala)

The catchment analysis helps identify how accessible community infrastructure is to residents across the township. This includes facilities such as community halls, early childhood centres, parks, and libraries which are critical for social cohesion, wellbeing, and equitable development (Planwisely, n.d.).

Catchment analysis provides valuable insights into the demographics and mobility patterns around a specific location revealing who lives or works nearby, how they access the area, and by what means, making it a vital tool for planners and related professionals across diverse projects (Planwisely, n.d.).

Using an 800-metre buffer which is equivalent to a 10-minute walk, the research is analysing the spatial distribution of key infrastructure within the township. The analysis revealed that Castlemaine Town Centre is well served by a concentration of amenities, including Victory Park, the Castlemaine Library, a community hall, and multiple gathering spaces. However, McKenzie Hill, is experiencing significant housing growth, lack walkable access to childcare, recreational facilities, and community hubs. Residents in these areas often

rely on private vehicles, highlighting a mismatch between residential development and infrastructure delivery (Infrastructure Victoria, 2021).

Furthermore, the absence of nearby agefriendly infrastructure in McKenzie Hill, such as accessible paths or healthcare services, affects older adults’ ability to age in place, a challenge exacerbated by topography and poor public transport (Wesley Hill Hall Committee, 2024).

Families also face a shortage of nearby playgrounds and public gathering spaces, as noted during community workshops. This analysis supports Project Postcode’s strategy to embed neighbourhood centres, walkable hubs with essential services into growing areas like McKenzie Hill. It provides an evidence base for addressing spatial inequalities and enhancing liveability beyond the town centre.

Most facilities in Castlemaine are concentrated in the Castlemaine Town Centre, creating a centralised hub for services, amenities, and community activity.

(image credit: DEECA (2025), Geoscape (n.d.), Hillary Namitala using QGIS

Creeks Rail line Playgrounds

With no established town centre and very limited local infrastructure, McKenzie Hill residents face significant barriers to accessible, everyday services.

(image credit: DEECA (2025), Geoscape (n.d.), Hillary Namitala using QGIS)

Wesley Hill hosts only a handful of scattered amenities, with limited pedestrian infrastructure—making everyday access difficult for those without a car.

(image credit: DEECA (2025), Geoscape (n.d.), Hillary Namitala using QGIS)

Childcare centres 10-Minute Walking Catchment

Planning controls across the three study areas highlight the considerations, barriers and opportunities, that arise for the purpose of delivering new models of housing and the provisions of other services in the broader Castlemaine Township.

• Castlemaine town centre: Residential zones surrounding the town centre commercial area highlights opportunities to integrate more housing into commercial areas, to seamlessly transition between commercial and residential land uses.

• McKenzie Hill: Largely residential zoning reflective of the limited community and commercial amenities in the area to service residents.

• Wesley Hill: Concentration of residential land uses highlights potential to strengthen community ties, and connection to surrounding environment (conservation areas).

• Castlemaine town centre: There are a significant number of heritage places within the Castlemaine town centre. This highlights the importance of housing development to be responsive to heritage character (if required).

• McKenzie Hill: Development controls, in particular, Development Plan Overlays, are failing to achieve sustainable subdivision and built form outcomes. This is observable, for example, in approved subdivision plans for sites which are subject to the Development Plan OverlaySchedule 1. This highlights the potential to bolster development built form controls to achieve more sustainable outcomes (see below).

• Wesley Hill: There are limited built form controls which apply to Wesley Hill residential area. This indicates the potential for increased density through infill development. Similarly, this highlights that built form controls could be applied to guide built form outcomes for future housing stock.

Subdivision plan for 34 Ireland Street and 7 Martin Street prepared in accordance with Development Plan Overlay - Schedule 1 provides limited sustainability or built form outcomes.

Extract of approved Subdivision Plan (image source: Spiire, 2021)

Castlemaine town centre - zoning map (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), DEECA (2025), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

McKenzie Hill - zoning map (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), DEECA (2025), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Wesley Hill - zoning map (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), DEECA (2025), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Planning controls not facilitating desired housing and development outcomes - but suggests potential and opportunities to implement these tools more effectively

Castlemaine town centre - overlays map (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), DEECA (2024), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

McKenzie Hill - overlays map (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), DEECA (2024), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Wesley Hill - overlays map (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), DEECA (2024), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

An analysis of the diversity of lot size and site coverage between and within the study areas provides an insight into the models of housing which could be implemented in the different residential areas within the Castlemaine Township.

Castlemaine town centre: Smaller lots and higher density of site coverage in the Castlemaine town centre highlight opportunities for infill development (e.g. shop-top housing). Larger lots around the edge of the town centre, and close to the train station may provide opportunities for higher density developments, including mid-size (three to four storey) apartment buildings which are in keeping with its heritage character, but appropriate in light of the more developed nature of the town centre.

McKenzie Hill: As a newer residential area, McKenzie Hill contains larger lots which reflect its “growth area” character. A number of these larger lots are subject to development / subdivision plans, indicating the future greenfield

development which will occur in this area. To date, this development is largely characterised by large lots with single, separated dwellings. As the area is being progressively developed as a residential area, however, there is potential for these greenfield areas to accommodate higher density development and encourage the community infrastructure and essential services this growth area requires to transform it into a neighbourhood centre.

Wesley Hill: Residential blocks in Wesley Hill are characterised by large lot sizes, with limited site coverage (large areas of open space and street setbacks). This indicates opportunities to discretely increase density in the area through infill development, including by way of subdivision, smaller secondary dwellings and internal divisions in Wesley Hill.

Lot size highlights potential for increased housing density and diversity of housing models which could be deployed

Castlemaine town centre - lot sizes (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), Geoscape (n.d.), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Smaller, built up lots provide opportunities for infill development (e.g. shop-top housing and apartments) in the Castlemaine town centre. (photo credit: Eliza Kane)

McKenzie Hill - lot sizes (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), Geoscape (n.d.), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Wesley Hill - lot sizes (image source/ credit: DEECA (2024), Geoscape (n.d.), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Large lot sizes reflective of ‘growth area’ character of McKenzie Hill and opportunities for greenfield development (image source: NearMap, accessed June 3, 2025)

Larger lots, with low site coverage and ample setbacks, in Wesley Hill provide opportunities for subdivision, additions and infill development (photo credit: Eliza Kane)

While vegetation is not intuitively related to regional and neighbourhood mobility, tree density is closely tied to connection to nature, biodiversity and climate resilience – all of which are critical elements underpinning urban and transport planning strategies to ensure that we can plan and design for a more sustainable future.

Patterns of tree vegetation and density across the Castlemaine Township provide an insight into the impact of urban development on the natural environment. It also provides important context for the housing and spatial accessibility strategies that Project Postcode proposes to implement.

Castlemaine town centre: Consistent with more developed, urbanised town centres, tree density within the Castlemaine town centre is medium to sparse to effectively non-existent. This has important implications for how people move within the centre, for example, to the extent it compromises shade and protection from urban heat.

McKenzie Hill: The farming areas of dense tree coverage transition to medium and sparse coverage, to completely cleared of trees in areas which have been recently developed as greenfield residential areas. Prioritising landscaping and biodiversity in greenfield areas can assist to achieve a balance between residential development and the natural environment, and strengthen connections to nature for residents.

Wesley Hill: Similar to McKenzie Hill, Wesley Hill is an predominantly urban area, which is surrounded by dense vegetation and conservation areas. Large trees are accommodate on larger residential blocks and within ample setbacks. Increasing density (including through infill development) in Wesley Hill must be carefully designed and implemented to avoid compromising residents’ connection to nature and biodiversity.

Castlemaine town centre - tree density (image source/ credit: DEECA (2025), Geoscape (n.d.), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

LEGEND (TREE DENSITY)

Built up commercial precinct contributes to limited tree density in the Castlemaine town centre (photo credit: Retno Palupi)

McKenzie Hill - tree density (image source/ credit: DEECA (2025), Geoscape (n.d.), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Wesley Hill - tree density (image source/ credit: DEECA (2025), Geoscape (n.d.), Eliza Kane and Rochelle Fernandez using QGIS)

Trees and vegetation cleared to make way for new McKenzie Hill housing development (image source: NearMap, accessed June 3, 2025)

Canopy trees connect residential areas of Wesley Hill to the surrounding conservation areas in Wesley Hill (photo credit: Eliza Kane)

In addition to research and analysis of the Castlemaine Township providing a solid evidence-base for the proposed planning project, Project Postcode has been informed and guided by the insights gained from the stakeholder and community engagement workshops.

Further, site observations from the studio trip to Castlemaine back in March 2025 provided critical experience of the township and the communities that we are planning for.

Research and analysis can provide a foundation for what planning and urban design interventions work to improve regional and neighbourhood mobility. The insights from the community and experiences of being in Castlemaine, however, also provide justification for why these interventions fit the Castlemaine township context - and therefore have greater chance of creating sustainable change within the Castlemaine region.

Planning concepts, precedents and case studies (detailed further in this section) provides further support for the viability of Project Postcode strategies and interventions. This also increases the potential to implement the Project Postcode toolkit in other regional areas, to improve mobility and accessibility.

the ‘centre’ of a town

A key takeaway from the stakeholder and community engagement workshops was the value that residents place on community connection and social ties. While the township is centred around a dominant commercial hub (that is, the Castlemaine Town Centre), there was a clear desire for a greater sense of connection between residents, outside of a traditional precinct.

Project Postcode is founded on the idea of creating ‘neighbourhood centres’by increasing urban density (that is, housing), it is possible to create more activity and greater connections. The Castlemaine town centre performs, and will continue to perform, an important function for residents. It is not necessary to create an additional ‘town centre’.

Project Postcode moves away from focusing on the town centre as the sole resource for the region. It instead proposes to create disagregated centres. This is in response to community members’ desire to build upon the existing connections within the region. The aim is to bring more services and activities to people in place, as a way to improve neighbourhood mobility and spatial accessibility.

“As soon as this happens, they’re disconnected... [this has a] significant impact on the community and [it’s] social fabric...” Quote:

Housing can be just as much a mobility and accessibility issue as transport networks are.

Through our engagement with the community, it became clear how passionate residents and stakeholders are about where they live and finding ways to improve and enhance connections within their neighbourhoods.

Relevant to regional and neighbourhood mobility, we began to understand where and how people live can play a key role to reduce the number of people who are underserved by existing transport infrastructure and connectivity (or at least mitigate the impacts of the gaps in transport infrastructure).

Housing provides people with access to employment, social and community amenities. Beyond this, the stakeholder and community engagement workshops emphasised how secure and stable housing is critical to “social fabric” of a township.

A critical turning point from the engagement workshops came from hearing about a common occurrence in the Castlemaine area, which connected the dots between housing, mobility and community and social connections. This was about the experience of people unable to stay in Castlemaine due to

losing their rental or who cannot afford to stay in Castlemaine. Without a car or access to public transport, the loss of their house had broader ramifications - affecting their employment, social connections, and access to essential services.

It was stories like this which emphasised the importance of rethinking how housing is delivered in and around the Castlemaine township. Further, by implementing strategies to improve housing for residents, how housing could be a resource to improve neighbourhood mobility and spatial accessibility for the current and future populations.

There is a hesitancy to change the ‘vibe’ of Castlemaine

While the current housing stock is not meeting the needs or diversity of households in and around the Castlemaine township, residential development contributes to the “vibe” of the regional township. Sentiment from the community and stakeholder engagement workshops was that this is valued by residents and that, in general, there is a reluctance to change this. Many people are attracted to the area and to live in houses with large front and backyards, being a style of house which characterises much of residential development in the region.

...but there is a desire to do things differently

Despite this, residents and stakeholders expressed an understanding that in order to meet the needs of current and future populations, things will need to be done differently. There is also a desire to change the way that people live, from traditional single separated (and sometimes, isolated) dwellings. This came through from discussions with residents who expressed concerns about the impact of certain population groups living independently (in particular, single older women). Residents expressed a need for initiatives which encourage

and facilitate aging in place and multigenerational living as a means to both build and strengthen community ties and to enable people to be supported to live where they would like to.

...and there is potential to deliver new models of housing, and good local examples to learn from

Being in Castlemaine enabled us to observe where there was potential to deliver new housing models, and what types of housing might be suited to both the residents and the ‘vibe’ of Castlemaine.

Further, we were able to learn about, and experience, initiatives being implemented in the region to address the housing mismatch. In addition to those discussed as part of our housing analysis (such as the Paddock EcoVillage - refer page 38), representatives from the Castlemaine Institute introduced us to different housing innovations. This included “Home Share” - a service to match people looking for accommodation with people who have spare rooms in their houses. This provided critical insight into the important connection between community and housing.

Single, separated dwellings contribute to Castlemaine’s distinct ‘vibe’.

House in Castlemaine (photo credit: Eliza Kane)

There are opportunities within existing residential areas to showcase new ways of delivering housing - to increase density and build good neighbourhoods.

Development opportunity in Wesley Hill (photo credit: Eliza Kane)

The Paddock EcoVillage is an example of delivering housing density in regional Victoria, without compromising landscaping and connection to nature and community.

The gardens at the Paddock Eco-Village (photo credit: Eliza Kane)

Through the community engagements and field trip to Castlemaine, a number of key themes and lived experiences emerged around mobility and accessibility. These reflections not only highlight the current limitations of the transport and mobility systems but also reveal opportunities for improving equitable and inclusive access across the broader Castlemaine Township.

Walking and biking are loved, but safety is a concern…

A strong community desire for walking and cycling was evident throughout the engagement process. Multiple participants expressed how much they valued active transport—both for environmental and health benefits. However, there was a shared concern about road safety. People felt unsafe walking or cycling due to high-speed vehicle traffic, inadequate bike lanes, and poorly maintained footpaths. For many, the fear of accidents, often based on past experiences, acted as a significant barrier—demonstrating that simply providing infrastructure isn’t enough without addressing perception, behaviour, and design quality.

to inclusive mobility

Several comments focused on how existing infrastructure limits mobility for people with disabilities, older residents, and young children. A striking example was the presence of large open gutters

(image below), which especially present obstacles for people using mobility aids or prams. These observations reinforce the need for universal design principles that cater to people of all ages and abilities.

affects people’s decisions to use active transport

Extremely cold winter mornings and scorching hot summer afternoons identified as barriers for active transport, particularly for school children and elderly individuals. Such factors exemplify the need to improve public transport networks, especially since these groups may also have restricted access to cars. Improving the public transport networks assists in facilitating independent mobility for these demographic groups, which means more independence for family members (or parents, in the case of school children).

Community members voiced the positive difference that trees planted along the streets and footpaths made to their experience in walking and cycling. Nature strips were recognised not only as environmental assets, but also a vital factor in enabling enjoyable and feasible active transport journeys. This observation aligns with Project Postcode’s broader aims of improving climate resilience and liveability through nature-based planning.

…my kids have activities after school, and without bus services post 3pm on most days, I am forced to drive them.

- Penny (from the community workshop, who lives in McKenzie Hill)

Most community members noted that, while bus routes technically exist, service frequency and operating hours were major drawbacks of the network. Buses commonly run only between 9am and 3pm on weekdays, with few or no services on weekends. This makes them unviable for after-school activities, work shifts, or social outings—particularly for those without cars. These limitations make reliance on buses impractical, especially for families and people living in fringe areas.

Beyond infrastructure, deeper cultural and social issues were also raised. For example, some residents shared that the condition and location of bus stops in inaccessible areas (like on top of a slope) discouraged them from even attempting to use public transport. Others highlighted that attitudes toward public transport—including a preference for cars due to convenience or necessity— also play a role in mobility choices.

One recurring theme was the way in which rising housing costs are pushing people out of Castlemaine’s core, distancing them from essential services like healthcare, education, and shops. As people move to more affordable areas on the town’s periphery, the gaps in transport and mobility infrastructure become more visible and pressing. This directly supports the need for improved spatial accessibility and more complete neighborhoods.

These community insights show that mobility and accessibility challenges in Castlemaine are multi-dimensional— shaped by physical infrastructure, social context, environmental conditions, and personal experiences. Addressing them will require integrated strategies that go beyond transport alone, supporting the wider goals of Project Postcode to build more connected, inclusive, and resilient neighborhoods.

There is a need for community hubs in the centreless towns...

The workshop gave participants a chance to share with the team some of the challenges they face with community infrastructure. They expressed gratitude for the inclusive design engagement process and shared genuine enthusiasm for the initiative. Many voiced strong support for placemaking initiatives and highlighted the importance of “aging in place,” ensuring that community infrastructure supports people across all life stages. A recurring concern was the lack of essential services and facilities in areas beyond the Castlemaine town centre particularly in Wesley Hill and McKenzie Hill. Participants identified limited childcare options, no formal child play spaces in Wesley Hill, and the need to increase the capacity of the Wesley Hill Hall. Others advocated for a dedicated structure for the local market to improve access, shelter, and usability. Residents from McKenzie Hill noted the absence of a community centre and the challenge of having to travel into Castlemaine for most daily needs, compounded by limited mobility and transport options.

Accessibility of community facilities is hard for residents...

In a conversation with community advocate and member Margaret, she highlighted the emotional and cultural value of shared spaces. She reflected on how local cafés, gardens, and public meeting spots create essential opportunities for connection and

belonging. For Margaret and others, it’s not just about buildings, it’s about creating social bonds and a shared sense of place within the community. Residents noted the lack of local barbecue areas and expressed concern over the poor maintenance of local public swimming pools, making them less appealing and usable. As a result, many choose to travel to Chewton for better swimming facilities, underscoring the need for improved aquatic infrastructure within their own community.

The world building exercise

Presentation after session (photo credit: Hillary Namitala)

Workshop held at Victory Park Castlemaine

Students during the workshop (photo credit: James Whitten)

Mobility bingo session

Students participating (photo credit: James Whitten)

Parents would love to take their kids to play but there are no play areas...

As part of our engagement, we held a “Day in the Life Of” session where participants shared their daily routines, revealing how they interact with local infrastructure and services. Penny, a mother living in McKenzie Hill, described the challenges of accessing leisure and sporting facilities for her children, most of which are located in Castlemaine. Although she would prefer to cycle, the distance and lack of safe routes compel her to rely on a car. Her children also lack independent mobility, requiring her to drive them to various destinations.

The elderly population rely on community spaces for social interaction but there aren’t any in some neighborhoods...

Margaret, a retiree, shared how older residents rely on access to shops, medical facilities, cafés, and parks not only for practical needs but also to support their mental health and overall wellbeing. Daily routines that include social interactions, gentle walks, or a visit to a café are vital for maintaining a sense of purpose and connection. However, many in her age group face mobility challenges, making walking difficult and cycling unfeasible. As a result, driving becomes the default, even for short trips. Those using mobility aids require flat, accessible surfaces, often travelling to Victory Park or the Botanic Gardens spaces that offer comfort and social opportunities. Wesley Hill,

however, lacks equivalent facilities, limiting options for older residents and contributing to social isolation. The need for inclusive, accessible public spaces in neighbourhoods like Wesley Hill is not just about convenience, it’s essential for sustaining mental health, independence, and community connection in later life.

Underserved communities are seeking more local facilities...

During the world-building exercise, participants shared aspirations for improved local infrastructure in the underserved areas like Wesley Hill and McKenzie Hill. Key suggestions included upgrading the Wesley Hill Market, establishing a neighbourhood community hub in McKenzie Hill, and increasing access to child play areas and public open spaces. There was a strong desire to reduce reliance on travel into Castlemaine by bringing essential services such as retirement facilities, community amenities, and recreational spaces closer to where people live. Participants also expressed interest in integrating ecological corridors to support both environmental health and community wellbeing through connected, nature-based design.

A core principle underpinning Project Postcode is the importance of planning and designing for ‘neighbourhoods’, as a means to improve housing diversity and affordability, and enhance spatial accessibility.

Project Postcode is informed by research which considers the benefits of developing at the neighbourhood scale. In particular, research conducted by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) into delivering ‘mixed tenure’ housing (Khor et al., 2023) and ‘sustainable’ housing at the neighbourhood scale (Dhur et al., 2023).

‘Mixed Tenure’ Neighbourhoods

Snapshot: ‘Mixed tenure’ (MT) refers to a “variety of dwelling products across a range of dwelling tenures, and is usually delivered on government-owned land” (Khor et al., 2023a, p. 7). Research conducted by AHURI (Khor et al., 2023) into MT neighbourhoods (distinct from with individual MT developments) follows earlier research which demonstrated the benefits of planning, designing at this scale (Khor et al., 2023).

Developing at a neighbourhood scale brings greater attention to the appropriate mix and location of dwelling types (Khor et al., 2023), as well as to the community amenities and infrastructure required to ensure the viability of increasing housing density and achieve neighbourhood

renewal.

Key lessons: MT neighbourhoods provide advantages for the delivery of more social and affordable housing, such as enabling social housing developments to be cross-subsidised, and deliver greater diversity of dwellings (Khor et al., 2023, p.2) in an urban area.

A coordinated approach, however, is required to “[maximise] the social and economic uplift” (Khor et al., 2023, p. 2) of MT neighbourhoods.

This is because ownership and governance structures of MT neighbourhoods involve a high degree of complexities, due to the number of actors involved in the development and delivery process (Khor et. al, 2023).

Relevance to Castlemaine Township: Principles and strategies for the delivery of MT neighbourhoods can be applied to areas within the Castlemaine Township to increase housing diversity and, importantly for Castlemaine residents, improve housing affordability.

This model provides a framework for Council to work with government and non-government actors (including community organisations), to coordinate the delivery of housing and community infrastructure.

By taking a staged, but coordinated, approach to development could also help to overcome resourcing and financing constraints that regional councils and towns face.

Sustainable housing at the neighbourhood scale

Snapshot: Developing at the ‘neighbourhoods scale’ provides advantage for delivering sustainable housing. Benefits go beyond improving the sustainability of individual buildings, to being able to reduce waste, energy and water use at scale, as well as encouraging sustainable communities.

Key lessons: Similar to MT neighbourhoods, more sustainable neighbourhoods requires the coordination of a significant and diverse group of stakeholders. In addition to regulatory and policy reform, education and engagement are key pillars of a holistic approach to achieving more sustainable outcomes in the built environment - these include to bring

stakeholders and community along the journey to reduce the risks associated with “untypical developments” (Dhur, 2023, p. 3).

Relevance to Castlemaine Township: Sustainability principles and bestpractice are, and continue to, be embedded into the frameworks, strategies and planning controls which guide future development. This is particularly important for those which apply to developing growth (greenfield) areas. This is to the extent these areas will be the source of a significant proportion of housing in the Castlemaine Township in the future (Mount Alexander Shire Council, 2023) and also provide opportunity for development at the neighbourhood scale.

A core element underpinning Project Postcode is that densifying housing can act as a key to unlock regional mobility. Project Postcode also recognises the need to densify housing sustainability (particularly in the context of the increasingly worsening climate crisis).

Two case studies from White Gum Valley, Western Australia provide an insight into how sustainable density could be achieved in the Castlemaine Township.

Case study: White Gum Valley, WA

Snapshot: A residential development located on a 2.2 hectare site in White Gum Valley in Western Australia. The site, which has also been identified as an example of MT development (Khor et al., 2023), has been developed as a result of different delivery models (cooperative led, competition-led and private partnerships) (Martin, 2021). It demonstrates a variety of higher density residential developments which embrace principles of affordability, community and sustainability.

Key lessons: Departing from traditional ways of developing housing is not without its challenges, particularly at a neighbourhood scale. Having a space in which to experiment with housing and sustainability initiatives, plays an important role in understanding how these solutions can be deployed in different regions.

Government intervention plays a key role in establishing the framework which facilitate the development of housing prototypes (Dhur et al., 2021).

Relevance to Castlemaine Township:

Demonstration projects could play a crucial role in showcasing how density can achieve positive outcomes for the community, as well as from a sustainability perspective.

Case study: Hope Street Housing, White Gum Valley, WA

Snapshot: A medium density housing project in White Gum Valley, WA. The development is comprised of 28 dwellings and prioritises landscaping to promote connection to nature and biodiversity (2024 National Architecture Awards Jury, 2024).

Key lessons: The considered siting of the townhouses enabled landscaping to be incorporated into setbacks and secluded open space so that increasing density does not compromise good design outcomes (MDC Architects, 2024).

Relevance to Castlemaine Township:

Residential development in growth areas has come at the expense of native vegetation (see discussed on page 50). Leveraging planning policies and urban design tools can avoid these outcomes for future housing developments.

White Gum Valley is an “experimental” (Martin, 2021) residential development located on 2.2 hectare site in Western Australia, featuring different and innovative models of housing.

Aerial image of White Gum Valley sustainable residential development (image source: NearMap, accessed June 7, 2025)

Two models of housing at WGV: (1) Sustainable Housing for Artists and Creatives and (2) David Barr Architects’ affordable housing units.

Not far from the White Gum Valley sustainable housing development is Hope Street Housing - an example of higher density living (townhouses) which balance “increasing yield and ensuring amenity for its inhabitants and neighbours” (2024 National Architecture Awards Jury, 2024).

Hope Street Housing, White Gum Valley, Western Australia (photo credit: Robert Firth, n.d.)

A key objective of Project Postcode is enhancing spatial accessibility, and building connected, resilient neighborhoods. This is done to reduce car-dependency, and subsequent transport costs on households, along with ensuring efficient public transport service and quality active transport infrastructure.

Research on the challenges small, underserviced towns like McKenzie Hill and Wesley Hill face, highlight barriers in mobility and the subsequent financial burdens on households with respect to owning private cars. In view of this, initiatives for shared mobility like carshare, bike-share or car-pooling, as well as intermodal transportation systems and low traffic neighborhoods are explored. While these initiatives ensure spatial accessibility at affordable costs, they also recognise Project Postcode’s aim to be environmental-friendly by ensuring equitable, inclusive, and sustainable mobility options for everyone.

Case study 1: Integrating shared mobility (ShareDiMobiHub Project, Europe)

The ShareDiMobiHub project is a crossborder initiative implemented across pilot locations in Belgium and the Netherlands. Co-funded under the Interreg North Sea Region Programme, the project aimed to

test and implement neighbourhood-scale shared mobility hubs—small, integrated nodes offering access to shared bikes, e-scooters, cargo bikes, cars, and public transport information (EU Urban Mobility Observatory, 2025).

Key Interventions

• Pilots across 10 cities, including urban centres and smaller communities, with emphasis on inclusive access, particularly for those without private vehicles or digital literacy.

Key Outcomes and Lessons Learned

• Users encouraged to shift from private cars to more sustainable options, especially for short trips.

• Placing hubs in lower-density and underserved areas, helped reduce transport disadvantages and improve local accessibility.

• Low-cost modularity and integration with existing public transport systems make the hubs highly replicable across European towns.

Relevance to Project Postcode/ Castlemaine Township

The project’s focus on mobility equity, digital access, and localisation aligns with Project Postcode’s goal of reducing spatial inequality and improving links between housing, services, and environment. Mobility hubs can help bridge the gap between infrequent public transport and the needs of residents in low-density townships—without large infrastructure investments.

Walthamstow Village in the London Borough of Waltham Forest was one of the first areas in London to implement a Low Traffic Neighbourhood (LTN) under the borough’s Mini Holland program in 2015. The scheme involved restricting through-traffic by using modal filters, calming traffic on residential streets, improving active transport infrastructure, and enhancing the public realm (Waltham Forest, n.d.).

Key Interventions and outcomes:

• Modal filters (such as planters and bollards), to prevent through-traffic on smaller residential streets resulting in motor traffic reduction (up to 44%).

• Re-allocation of road space for walking and cyling infrastructure resulting in increased activity (walking increased by 32% and cycling by 18%). (Liveable Cowley, n.d.).

• Air pollution decreased; fewer car journeys were reported.

Lessons for the Castlemaine Township:

Walthamstow shows how reducing car dominance can restore local identity and walkability—goals shared by Project Postcode. LTNs enhance accessibility for non-drivers (e.g. children, the elderly, people with disabilities), especially critical in regions with limited public transport (like in McKenzie Hill). Additionally, the example highlights how transport planning can double as community building and climate resilience.

The rapid expansion of Australia’s urban areas, particularly in greenfield sites, has often prioritized housing development without adequate investment in essential social and community infrastructure (Pawson, Randolph, & Troy, 2021). This oversight has led to more communities with limited access to vital services such as schools, healthcare facilities, and recreational spaces, thereby impacting residents’ quality of life and social cohesion.

Randolph et al., 2020 in Ahuri’s report underscores the critical importance of embedding social infrastructure planning within the early stages of residential development. The report highlights that in rapidly growing areas of Sydney, Brisbane, and Perth, the provision of social infrastructure frequently lags behind housing construction, resulting in accessibility challenges for residents just like Castlemaine. For instance, the study found that access to schools and hospitals within a 30-minute transit ride was significantly lower in these growth areas compared to established urban regions.

Project Postcode adopts an approach that encourages the design of neighbourhoods and new estates to embed community infrastructure from the outset, rather than retrofitting it later.

A strong precedent for this is the Oak Rise Housing project by Cumulus Studio in West Hobart, Tasmania. This project integrates high-quality housing with shared green spaces, communal gardens, and accessible pathways that encourage social connection and a sense of belonging (Cumulus Studio, 2025). Similarly, Project Postcode aims to promote developments that include play areas, local gathering spaces, walking trails, and essential services within walking distance of homes. By embedding infrastructure such as childcare facilities, neighbourhood hubs, and ecological corridors into the initial planning, new communities particularly in fringe areas like Wesley Hill and McKenzie Hill can grow in a more equitable, sustainable, and connected way.

Developed in partnership with Housing Choices Tasmania and the Department of Communities, the project delivers 48 single storey homes organized around shared green spaces and pedestrian-friendly pathways. The layout encourages passive surveillance, incidental social interaction, and a strong sense of place which are critical elements for building resilient communities.

Key design features such as communal open spaces, accessible pathways, and integration with nature landscapes highlight how infrastructure and housing can be codeveloped to support social connection, active lifestyles, and inclusivity.

For Castlemaine’s fringe areas, such as Wesley Hill and McKenzie Hill, Oak Rise demonstrates how new developments can embed community infrastructure from the start. As residents in these areas face limited access to parks, childcare, play spaces, and local hubs, a place-based design model like Oak Rise offers a blueprint for delivering both housing and vital community assets together to reduce car dependency and improve everyday livability.

An image of the Oak Rise project (image source: (Cumulus Studio, n.d.)

Community spaces designed to be adaptable, and flexible to support various uses, from community meetings and fitness classes to performances and social gatherings to be adopted Project Postcode.

Creating stormwater management areas in residential neighborhoods to provide access to blue infrastructure.

River lee’s New Epping (image source: (Riverlee, n.d.)