Hannah Scott-Talib @hannah.sctt

money to landlords straight from tenants’ pockets.”

Justpast noon on Jan. 19, a group of a dozen demonstrators gathered outside the o ce of the Tribunal administratif du logement (TAL) in Montreal’s Olympic Village.

Together, they held up a large banner that read, “Refuse together, every tenant needs a union.” Behind them, spraypainted on the building’s brick wall in bright yellow, was a straightforward message: “Fuck landlords.”

“We believe that housing should be distributed based on need and not nancial means,” said a spokesperson for the Montreal Autonomous Tenants’ Union (MATU), the organization behind this surprise action.

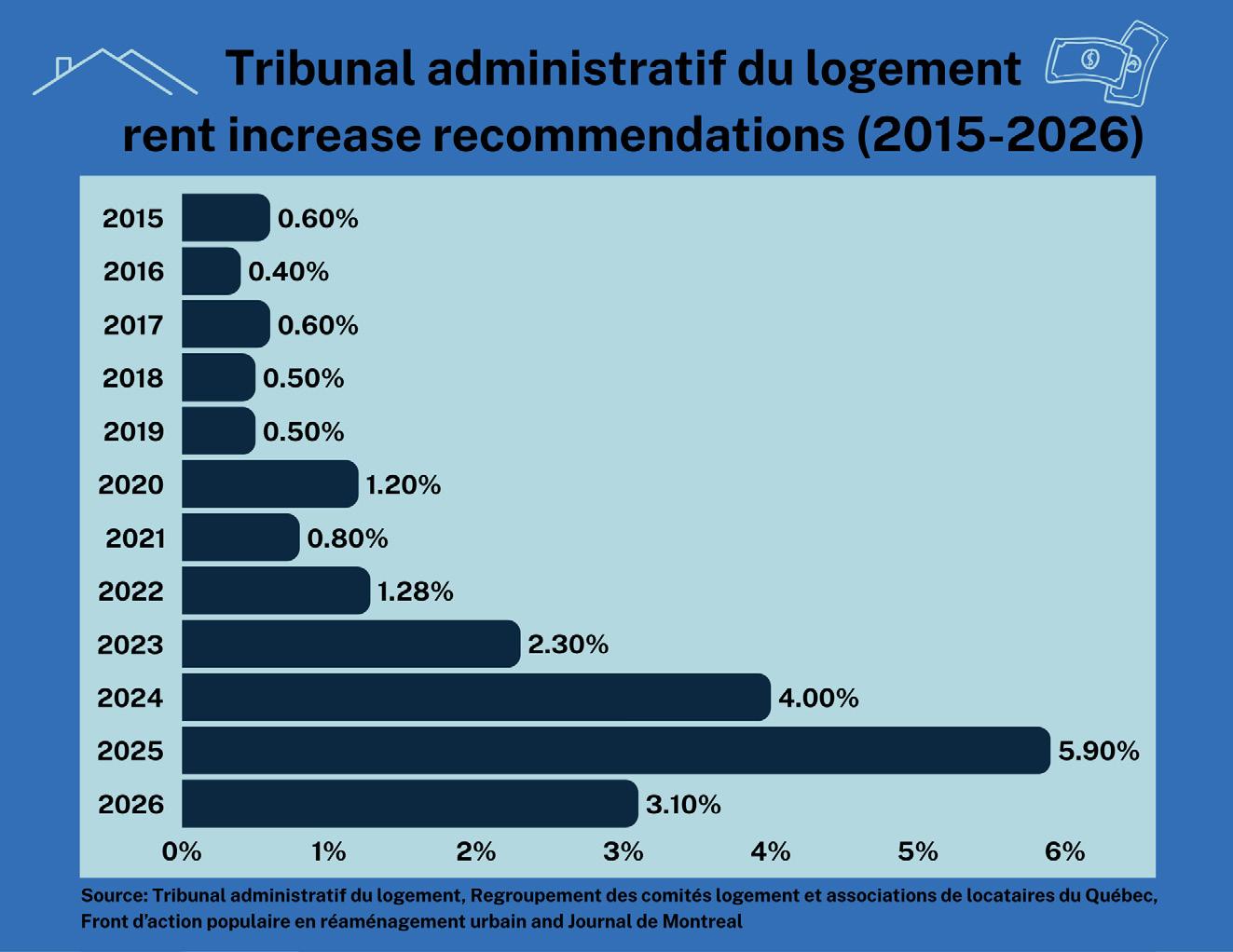

e last-minute demonstration was organized in response to the TAL’s recently implemented basic rent increase recommendation for 2026. e tribunal is recommending a 3.1 per cent rent hike for all Montreal apartments that have not undergone major renovations.

While this rent increase percentage is smaller than the 5.9 per cent increase from 2025, some tenants’ rights groups believe this year’s increase is still too high.

“It’s not exactly good news in the sense that 3 per cent is still fairly high,” said Steve Baird, a community organizer with the Regroupement des comités logement et associations de locataires du Québec (RCLALQ). RCLALQ is an advocacy group focused on the right to housing and tenant solidarity.

For years before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, all of the TAL’s annual rent increase recommendations for basic apartments were under 1 per cent, Baird explained.

“ ree is a lot compared to less than 1 per cent, so this is going to keep pushing rent up,” he said.

Baird added that the new calculation being used to de-

termine the rent increase recommendation this year is a signi cant change from years prior. is year, the TAL is taking into account the past three years of in ation in its calculation, whereas in previous years, the calculation was based on the last year of in ation.

“Right now, in ation has just come down, and we’ve just paid really big rent increases for the in ation of last year and the year before,” Baird said. “Now that it’s nally come down, all of a sudden, [the TAL] has decided, ‘Well, let’s calculate the last three years [of in ation].’ at’s why it hasn’t come down that much; that’s why it’s still 3 per cent and not less than that.”

RCLALQ is not the only housing organization speaking out against “una ordable” rent in Montreal, despite lower ination predicted for 2026 compared to 2025.

“Rent is already too high for too many tenants, who nd themselves with no options due to the shortage of social housing,” said Véronique La amme, a member of the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain. “Residential insecurity is on the rise, as is food insecurity due to high rents.”

Demonstrators at MATU’s Jan. 19 protest expressed resentment towards the TAL, a system they said primarily serves landlords.

“We don’t support this new calculation. We don’t support rent increases,” said the spokesperson for MATU to the crowd. “[ e TAL] helps [landlords] to develop strategies to trap tenants, maximize pro t, spend the least amount of money and simultaneously use various strategies to push people from their homes.”

According to Baird, Montrealers can expect to see “signi cant upward pressure on rent” this coming year, with high rent prices being increased even more.

“ e short story of this is that this exploding rent in Montreal still isn’t over yet,” Baird said. “It’s still really worrying for tenants who are on a tight budget, or the homelessness crisis, or for all sorts of people.”

However, Baird, along with several members of MATU present at the demonstration, said actions like applying pressure on landlords and building tenant solidarity could have a real impact this year.

“We’ll keep pushing for the TAL to change [the recommendation] again, or have something that’s better for tenants,” Baird said.

Meanwhile, MATU members distributed yers in front of the TAL’s headquarters, encouraging Montreal residents to refuse rent increases from their landlords this year.

e yer urged residents to “not accept what your landlord o ers you,” adding that the new three-year in ation-based calculation “will mean more

Baird said that, for tenants who are unsure of where to start when it comes to negotiating a rent increase, websites such as locataire.info are a good place to start. e website contains information on tenants’ rights, how the TAL works, mobilization tools and more.

“If you know how that [rent] calculation works," Baird said, "it puts you in a better position to maybe negotiate lower.”

La amme reinforced the sense of urgency surrounding the housing situation in the city, expressing that more and more tenants are “just one unexpected event away” from not being able to pay rent.

“New housing coming onto the market is contributing to the acceleration of the rise in average rents in Quebec,” Laamme said. “We must tackle the crisis for what it is: a crisis of una ordability.”

Montreal to donate unsold food to food banks

Montreal is considering legislation that would require restaurants and grocery stores to donate unsold food to local charity organizations and food banks. e general manager of Maison de l’innovation sociale is working with the city on the project in an attempt to curb Montreal's annual 740 tonnes of food waste, she said in an interview with TVA Nouvelles.

Carney claims "no intention" for free trade agreement with China

Canada Prime Minister Mark Carney told reporters on Jan. 25 he has "no intention" to pursue a free trade deal with China, but is instead looking to “rectify some issues that have developed in the last couple of years.” e announcement came a er U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to impose 100 per cent tari s on Canada if the country "makes a deal with China."

Quebec to remove British crown from coat of arms

Quebec announced that it will remove the British crown from its o cial coat of arms to rea rm the province’s autonomy. Justice Minister Simon Jolin-Barrette said in a statement following the decision that the “vast majority of Quebecers have no attachment to the British monarchy” and that the removal will ensure that “Quebec's institutions and national symbols respect the Quebec population.”

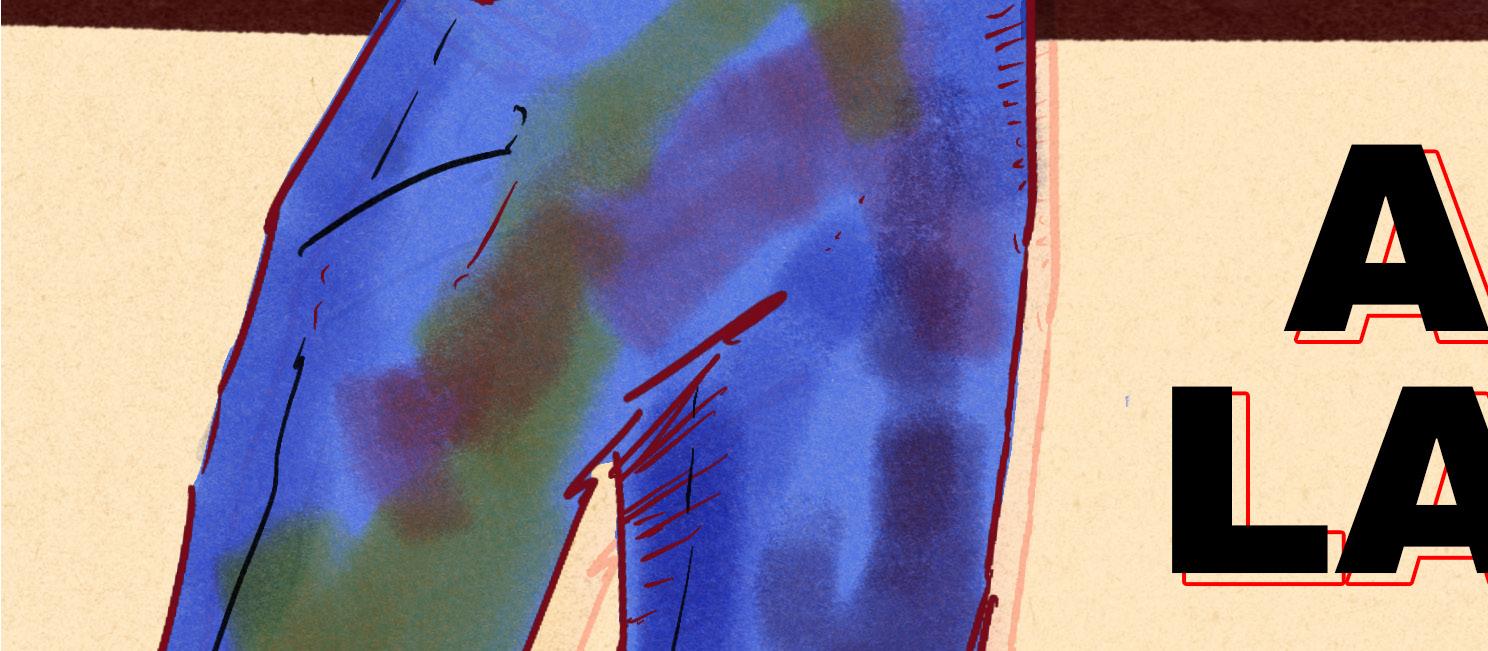

Alec Nikoghossian’s short film explores nostalgia, tension and loss

Safa Hachi @safahachi

Born in Beirut, raised in the U.A.E. and now based in Montreal, Armenian-Lebanese lmmaker Alec Nikoghossian began exploring the concept of home during his time at Concordia University, examining what it encompasses, what holds it together and what it quietly absorbs.

His latest short lm, “Closer in Strife,” perfectly condenses those questions into 10 minutes of domestic intimacy, silence and tension, inspired by real family conversations and the 2020 Beirut port explosion.

Nikoghossian recently graduated from Concordia’s Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, but lmmaking has been part of his life far longer.

He began making videos as a child, initially for fun, before realizing in high school that lm was something he wanted to pursue seriously. Still, he says it wasn’t until his second year at Concordia that his work began to take shape more deliberately.

“It was only up to two years ago when I started to really realize my style,” he said. “I kind of realized I had this attachment to home and my culture.”

at realization emerged gradually, through experimentation and re ection.

Like many Armenians and Lebanese individuals, Nikoghossian grew up with a strong sense of cultural pride, but also a lingering distance from the places and stories that shaped his family.

While "Closer in Strife" is a ctional narrative, it is closely informed by moments Nikoghossian has witnessed and conversations he remembers within his family home. Set in Beirut in the lead-up to the 2020 port explosion, the lm re ects how domestic life continues under the weight of an approaching rupture.

“Every piece of dialogue in that lm is based on an actual conversation I’ve had,” he said, referring to exchanges with his family.

Rather than depicting the explosion itself, "Closer in Strife" centres on the emotional atmosphere that precedes it.

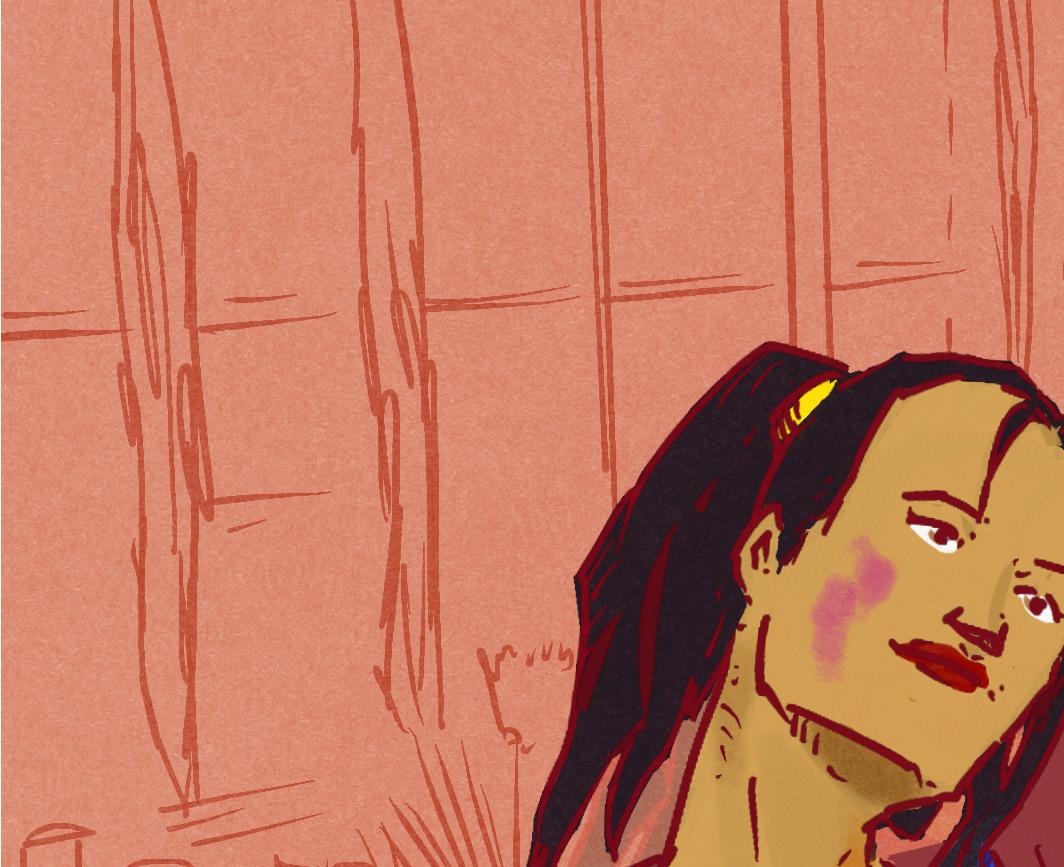

e lm follows a grandmother and her young grandchild in the hours leading up to the blast, allowing tension to build through silence, routine and shared space. e catastrophe remains o screen, but its inevitability shapes every interaction.

at grounding gives the lm its emotional weight. Rather than dramatizing catastrophe, “Closer in Strife” explores how intimacy and distance coexist within families, especially across generations.

Nikoghossian points to the disconnect that o en exists between grandparents and children—not necessarily because of a lack of love, but because of time, language and experience.

“No matter how close you are, there is always kind of this disconnect,” he said. “ ey grew up in a completely di erent time.”

Language plays a role in that distance as well.

Nikoghossian notes how English often overtakes mother tongues for younger generations, creating subtle barriers to communication. That tension is present throughout the film, not as conflict, but as quiet misalignment.

e decision to keep the lm slow and largely silent was intentional. Nikoghossian wanted viewers to sit with discomfort as much as familiarity.

“I wanted it to feel nostalgic, but with a sense of mystery,” he said. “I didn’t want music. I just wanted silence.”

at silence mirrors the unpredictability of life in Beirut at the time.

“People were just going about their normal a ernoons until suddenly everything ipped,” Nikoghossian said.

e lm was made with a small, close-knit crew, mostly friends from university, which helped maintain the intimacy Nikoghossian was a er. On set, there were rarely more than four to ve people.

“Film sets tend to be very hectic,” he said. “I wanted this to feel as calm and intimate as possible.”

A key collaborator was cinematographer Jérémie Urbain, one of Nikoghossian’s closest friends. e two have worked together since their early university days, and their familiarity shaped both the process and the nal look of the lm.

Urbain remembers rst discussing the project during a long subway ride.

“We straight up talked visuals, mood, colour and shots,” Urbain said. “It all organically came together.” at collaboration extended into the lm’s visual language. e camera stays close, o en intruding into the living room space, emphasizing texture and detail over orientation.

“The shots needed to be extreme close-ups to immerse the audience in a different time and space,” Urbain explained.

Working in a tight apartment came with constraints, but those limitations encouraged creative solutions. Bright, almost comically yellow lters were added to set lights, and Vaseline was applied to the lens to create a so ened image, giving the space a nostalgic, ethereal quality.

“ at warmth was essential to creating the lm’s nostalgic feeling,” Urbain said. “It helped us put the audience into a timeless Armenian-Lebanese apartment.”

At the emotional centre of "Closer in Strife" is the grandmother, played by Rosalia Evereklian Vassilian, an actress with over four decades of experience in Armenian theatre.

Vassilian grew up surrounded by performance, as her father was an actor and director, and she rst stepped on stage at nine years old. Over the years, she has acted in comedies and dramas, and later took on directing roles herself.

When Vassilian read the script, what struck her was the character’s patience.

“The patience and the love of this grandmother for her granddaughter, going along with her silence without any remarks,” she said.

Nikoghossian's story resonated personally with her.

Having grown up in Lebanon during the civil war, Vassilian said she immediately understood Nikoghossian’s approach. She described the lm as a courageous act, one that preserves family experiences shaped by instability and loss.

For Maria Azadian, Nikoghossian’s cousin, watching the

lm was both emotional and a rming. e two share the same grandparents, whose lives and home inspired much of the lm. Seeing Armenian-Lebanese identity represented on screen felt signi cant.

“It felt validating to see their stories on screen,” Azadian said. “It rea rmed that our stories are worth telling.”

Certain moments were instantly familiar, like a scene involving a tower of playing cards, which recalled childhood games. More broadly, Azadian connected to the lm’s depiction of generational distance.

“Tragedy is o en the trigger to building a closer relationship,” Azadian said.

She also emphasized the importance of situating Armenian life within Beirut itself.

Armenians have lived in the city for over a century, and their presence is deeply woven into its fabric. In her family’s case, the 2020 explosion caused severe damage to Azadian's grandparents’ home, only a few streets from the port.

Since its completion, “Closer in Strife” was screened in Beirut and at Armenian-focused film festivals, and will screen at the Slamdance Film Festival in Los Angeles as part of its Narrative Shorts program. e lm will have in-person screenings on Feb. 21 and Feb. 24, with virtual screenings available on the Slamdance Channel from Feb. 24 to March 6. A wider public online release is expected this summer.

For Nikoghossian, the recognition is encouraging, but the most meaningful responses remain personal.

“Anytime I hear it moved someone, it moves me too,” he said. “It kind of keeps you motivated to focus more on personal stories.”

Ultimately, “Closer in Strife” is less about depicting disaster than about observing what happens around it. e lm lingers on the fragility of ordinary moments, reminding viewers how quickly the familiar can shi .

For Nikoghossian, that focus feels inevitable.

“You just never know what’s coming next,” he said. “So you just go for it.”

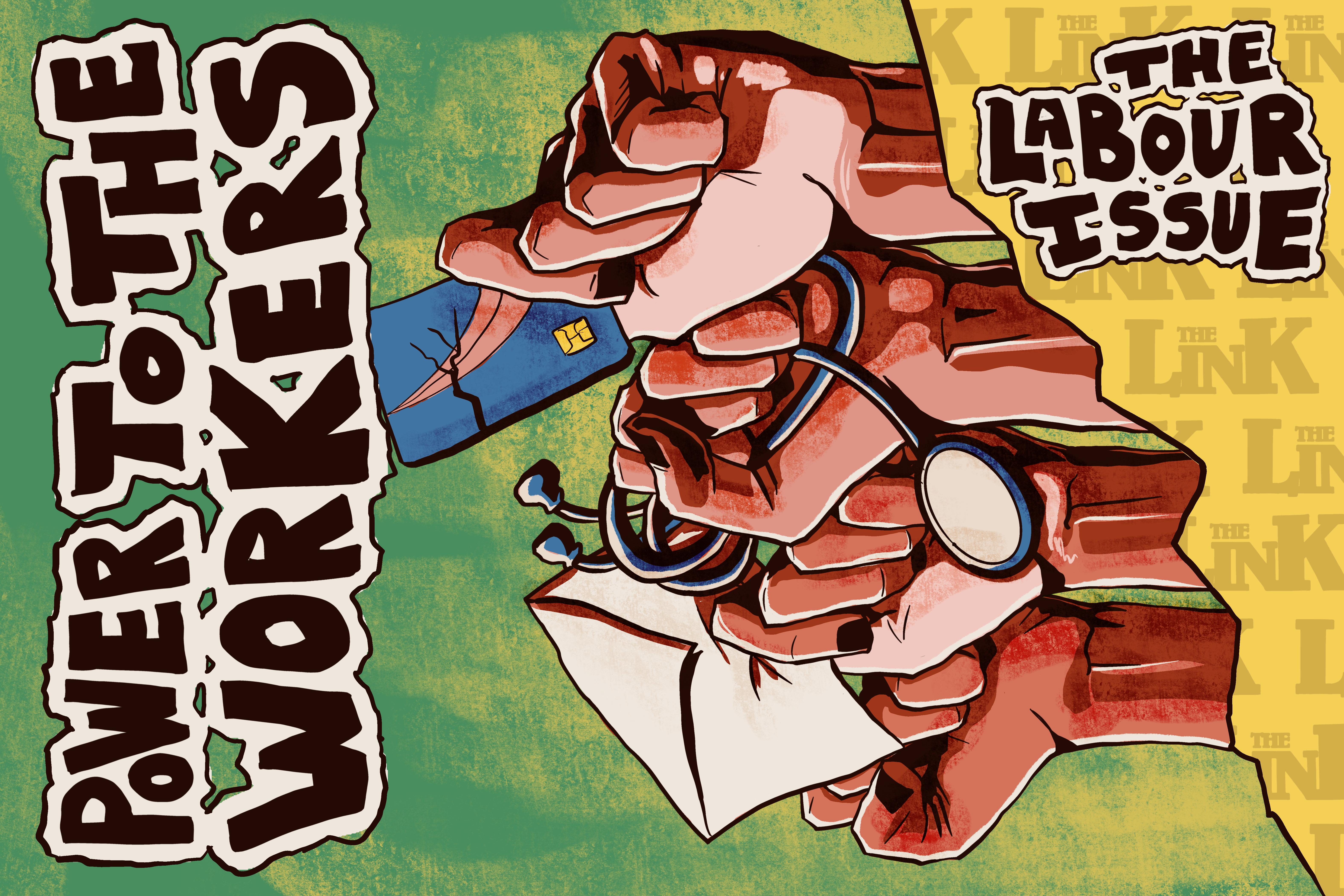

If you paid attention to the Société de transport de Montréal (STM) strike in late 2025, you likely saw how quickly public discussion turned on transit workers. Online threads lled with accusations of workers holding the population “hostage,” coupled with demands that the government intervene and claims that unions were harming people’s lives. at response didn’t only come from political elites or corporate executives. It came largely from workers themselves—people who rely on public transit, who work xed shi s, who balance jobs, family obligations and rising costs.

It is in this climate that Quebec’s Law 14, formerly Bill 89, now operates. e law presents itself with reassuring language. It promises to “give greater consideration to the needs of the population” during strikes and lockouts. To the aforementioned frustrated folk, this might sound like a quick x.

But herein lies the problem: the “population” this law claims to protect is overwhelmingly composed of workers. And when workers are led to believe that other workers stand in the way of their well-being, something has gone wrong.

During the STM strike, the focus shi ed away from why negotiations stalled for so long and instead toward how fast the strike could be shut down.

Law 14 formalizes that shi . It gives the labour minister the authority to intervene in strikes and lockouts deemed to cause serious or irreparable harm to the population’s social, economic or environmental well-being. is criteria so broad that almost any large-scale labour action could qualify.

What was once political pressure is now legal power.

Strikes are not spontaneous acts of disruption. ey are the outcome of unsuccessful ne-

gotiations, democratically voted on by workers who understand the risks involved.

e right to strike exists because inconvenience is o en the only leverage workers have when employers refuse to bargain.

By lowering the threshold for government intervention, Law 14 changes the balance at the bargaining table. Employers now have a reason to wait. Why compromise if the state can just step in once pressure builds?

François Legault’s CAQ government didn’t just wake up one day and start worrying about your commute.

In practice, unions argue this turns a core bargaining tool into a switch the government can ip o once the pressure starts working. at’s why major federations like the Confédération des syndicats nationaux went to court almost immediately a er the law came into force.

Even Québec solidaire’s Alexandre Leduc raised that concern during the STM strike, arguing the dynamic was already shi ing before the law had even o cially taken e ect.

So yes, the public su ers during strikes; that is the leverage. at is what forces powerful institutions to treat workers like human beings instead of line items.

What’s changed lately is how quickly the su ering gets redirected, not toward governments that underfund services or employers who stonewall, but toward the workers who keep those services alive.

We’ve watched the same re ex beyond Quebec. In federally regulated sectors, Ottawa has increasingly leaned on Section 107 of the Canada Labour Code. It’s a mechanism unions and critics say has been used to shut down strikes and lockouts by forcing disputes into binding arbitration.

And let’s not pretend this is brand new. When Canada Post workers struck in 2018,

Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government passed Bill C-89 to legislate them back to work.

Every time a government normalizes strikebreaking, whether through a vote in Parliament or a quiet referral mechanism, it lowers the political cost of doing it again. is isn’t just a Quebec story, or even a Canada story. In France, unions have repeatedly turned to mass strike days in response to budget cuts and austerity, and the public reaction there is o en just as furious.

e di erence is that France has a stronger cultural muscle memory of collective disruption: the idea that sometimes nothing moves because the people who make everything move are demanding to survive.

We need that memory here because the backlash has begun to do the government’s work for it.

When workers turn on workers, power wins twice: it gets to keep wages down and keeps us blaming each other for the mess.

Let’s be clear about what’s at stake: strikes are not meant to be comfortable. ey exist because, without disruption, those in power have no reason to move. Hostility toward labour action doesn’t just hurt unionized workers; it erodes the only leverage most people will ever have against employers or governments that bene t from exhaustion and delay.

Our power as workers exists only so long as we act together. When the right to strike is treated as a nuisance rather than a democratic tool, that collective power is deliberately weakened in the name of the status quo.

But workers are not acting against “the public.” Workers are the public. And when we accept laws that hollow out the right to strike because the disruption is inconvenient, we aren’t protecting ourselves. We’re making it easier to be ignored.

Despite grim academic and job markets, many students embark on their PhD journey for the sheer love of research

Varda Nisar @varda.nisar

Weare currently in the age of academic in ation, where academic degrees and achievements are devalued, according to recent reports.

“I knew what I was getting into when I decided to do a PhD. A declining eld. Few, if any, permanent jobs,” says omas MacMillan, a PhD candidate in Concordia University’s history department.

Over the years, the number of people obtaining a PhD has grown, but the same has not been true for academic jobs.

TRaCE McGill, in 2021, traced the post-graduation journey of McGill University's 4,500 PhD alumni who had graduated between 2008 and 2018.

e report found that only 54 per cent held jobs in academia, spread across universities, colleges, CEGEPs and university research centres and institutes. However, only 23 per cent secured tenure-track jobs.

Despite the precarious status of the current academic climate, for students like MacMillan, PhD research provides “an opportunity to really dive deep into a topic meaningful to myself and hopefully others.”

However, he expressed that the opportunity comes at a deep personal and nancial cost.

Concordia’s Doctoral Graduate Fellowship offers a base package of $14,000 per year to PhD students, totalling $56,000 over four years.

“I was able to negotiate for the maximum funding a er a previous professor advised me to,” said Tim Chandler, a PhD candidate in Concordia’s art history department.

“Some of my peers entered the program with no departmental funding at all,” Chandler added.

In an email to e Link, Julie Fortier, Concordia’s deputy spokesperson, pointed out that in 2019, the university increased the Doctoral Graduate Fellowship from $10,800 for three years to $14,000 for four years.

Fortier further outlined that the total nancial support from Concordia donors to PhD students—a di erent pot of money than that of the Doctoral Graduate Fellowship—was double in 2024-2025 compared to what it was 10 years before.

But even if one were to get the maximum package offered by Concordia, data shows it would barely cover the cost of living and tuition.

As per the Institut de recherche et d’informations socioéconomiques, the cost of living for a single person in Montreal in 2025 was $40,084, an increase of 4.2 per cent from 2024.

Professor Kevin A. Gould of the geography, planning and environment department emphasized that funding from the Doctoral Graduate Fellowship has remained the same since 2019.

“ e package is not great, and it has stayed the same in geography for a long time as in ation has hollowed out the value,” Gould said.

However, geography professor Damon Matthews suggested that graduate student funding can be seen as a joint e ort from the university’s internal scholarships, the department’s teaching assistantships, research bursaries and other external scholarships that the student nds themselves.

A PhD program is a full-time, 40-hour-per-week commitment that takes most students three to six years or longer to complete.

For external funding, students can rely on provincial sources such as the Fonds de recherche du Québec (FRQ) or federal funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

e results from the 2024 competition cycle reveal that, of the 2,201 eligible applications, SSHRC awarded only 935. Most students end up applying for several cycles in the hopes of being awarded funds that may ease their academic journey.

"I only applied for FRQ once because my capacity to take rejection is very low,” said Sneha Kumar, PhD student at the department of lm and moving image studies. “But I know people who applied for SSHRC and FRQ two or three times before succeeding."

For people like MacMillan, it became necessary to ll funding gaps through various other means.

“I had four years of university funding, $14,000 per year. I was a TA seven times. I taught a course in my department. I received small scholarships and borrowed a bunch of money through the US Department of Education,” MacMillan said.

MacMillan added that he also worked as a research assistant, substitute teacher, union o cer and for political campaigns in the U.S.

Yet, according to Chandler, there is another problem at hand for PhD students.

“Virtually no humanities students can nish their PhD in four years, setting us up for failure at the end of our degrees, when we have a higher workload teaching than ever and more thesis work than ever,” Chandler said.

For some international students, the high cost of tuition creates an additional barrier to achieving their dream of earning a PhD.

“Financial stress of this magnitude is not just an economic hardship. It directly a ects well-being and academic performance,” said Ahmed Musa, an international PhD candidate who was granted a pseudo-

nym for fear of academic repercussions.

“An international PhD student spends ve or more years of the most productive period of their life working essentially at minimum wage or below, while carrying research expectations equivalent to full-time professional positions,” Musa added.

While the responsibility is shared, some feel that Concordia’s nancial situation has placed an additional burden on PhD students, which is o en overlooked.

As Concordia faces what president Graham Carr recently called “the most serious [ nancial] challenge in Concordia's recent history,” there have been cuts across the board, leading to more competition for the limited resources available.

In 2023, Concordia made signi cant cuts to the Conference and Exposition Allowance that allowed emerging scholars to share their research. More recently, Concordia also made the decision to not to renew limited-term appointment (LTA) teaching contracts, leading to anger across the board.

Chandler said these cuts have led to PhD students carrying a considerably larger academic load.

“It just feels like Concordia's administration keeps pushing work down the chain of instructors,” Chandler said. “First, our department had to freeze hiring professors, then LTAs. And a lot of that work falls to PhD students who are teaching courses.”

Fortier called it “inaccurate” to say the university is increasingly relying on PhD students to deliver core teaching.

She said the allocation of teaching assignments, including to graduate students, is governed by collective agreements, and said the number and type of courses taught by graduate students have not changed.

The Concordia Research and Education Workers union (CREW) went on strike for better pay in March this year. The union said in its collective agreement that its student members deserve a living wage, a fairer workload and better job security through indexed contract hours for teaching and research assistants.

“I think there’s de nitely an over-reliance on student labour at Concordia, even beyond the fact that all of the university’s biggest courses can’t function without the work of teaching assistants,” Chandler said.

Many PhD students also come to the program while balancing their caregiving responsibilities for families, partners and children.

According to Musa, this includes the issue of health insurance coverage for family members. While international PhD students are covered under the university’s compulsory health insurance plan, their dependents are not.

“ is is not for lack of willingness," Musa said. "International students are willing to pay [for dependent health coverage]."

Fortier said the university has “considered” insurance for dependents and consults with the Concordia Student Union and the Graduate Students' Association (GSA) on the matter regularly. She claimed it was last discussed in the summer of 2025, where the “student association did not endorse any of the proposed options for dependent coverage.”

In the 2025 GSA general election, a referendum question asked the graduate population whether they wanted to negotiate for extended coverage for dependents to be added to the international students’ health insurance plan.

e question received 283 votes in favour, with 112 against and 32 abstaining.

For international PhD students like Musa, there remains a stark contrast between what PhD programs are advertised as versus what they actually entail.

“Instead of a stable, supportive environment fostering innovation,” Musa said, “many nd themselves navigating nancial instability, insu cient support systems and institutional policies that have not adapted to the realities facing global scholars today.”

Moon Jinseok @la_ville_de_moontreal

Recentlegislation by the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) government has drawn criticism and large demonstrations from both workers and unions across the province who see Law 14 as an attack on the entire labour movement.

Quebec’s Law 14, formally known as Bill 89, was assented to on Nov. 30, 2025, as an act “to give greater consideration to the needs of the population in the event of a strike or a lock-out.”

“It doesn't respect the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Canada,” said Québec solidaire MNA Alexandre Leduc. “[ e principles] in the law are way too vague, way too vast.”

Law 14 allows the labour minister to intervene to stop a strike or a lockout to maintain “services ensuring the well-being of the population.” It aims to prevent disproportionate impacts on the social, economic or environmental security of vulnerable groups, as written in the bill.

“[Negotiation outcomes] might become political decisions instead of working relations decisions,” said Caroline Senneville, president of the Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN), the second largest trade union federation in Quebec.

“Health and security are already secured by [these] essential services," Senneville added. " at's why we strike. [...] It's an economic inconvenience for the employers.”

Law 14 draws criticism from unions, who say workers have lost a crucial bargaining tool

“Almost everything can fall under this criterion, so we had a hard time de ning or restraining this criterion. It's an all-included bu et at this point,” he said. “I think that's what [Boulet] wanted, to have the power to unilaterally cancel any strike anywhere in Quebec.”

Boulet attempted to implement Bill 89 earlier in November 2025 to stop the strike of maintenance workers and bus drivers of the Société de transport de Montréal (STM).

However, the attempt failed because workers suspended the strike, following a last-minute deal between the transportation workers' unions and the STM.

Leduc claimed he warned Boulet that Law 14 could undermine unions’ bargaining power by providing employers a reason to wait for ministry intervention. Leduc said this shi in structural dynamics had already started during the STM strike in 2025, even though the law had not yet been enacted.

Senneville said she believes the law will infringe on workers' rights across the province, depriving unions of the right to strike, a crucial negotiating tool.

“[If] any government can end a strike that has been democratically voted on, do I really have the right to strike?” she said.

Leduc said the law gives too much power to Jean Boulet, Quebec’s labour minister.

point an arbitrator, insisting that the strike has caused economic damage, which, under Law 14, would allow the government to suspend their right to strike.

Law 14 grants the labour minister the authority to direct the dispute to an arbitrator if he considers that a strike or lockout “causes or threatens to cause serious or irreparable injury to the population.”

This clause gives the Tribunal Administrative du Travail the right to determine whether stalled services must be maintained during a strike or a lockout, effectively suspending unions’ striking power.

Five labour unions led a legal dispute against Law 14 with the Quebec Superior Court in December 2025.

ese included the CSN, the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec, the Centrale des syndicats du Québec, the Centrale des syndicats démocratiques, and the Alliance du personnel professionnel et technique de la santé et des services sociaux.

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a strike is a constitutional component of the freedom of association under Section 2(d) of the Canadian Charter, explained Mathilde Baril-Jannard, former CSN lawyer and labour law course lecturer at McGill University.

“Some people at the bus service and the union [said,] ‘Why should the [STM] negotiate and try to nd some compromise?”

“If the minister interrupts that [labour law process] and forces the arbitration mechanisms—of course, a third party can help, but this third-party arbitrator will impose a solution that the parties didn't negotiate—I'm not sure that the con icts between the parties will be resolved,” Baril-Jannard said.

Leduc said. “' e issue is going to be solved by the government in a few weeks by using this law.'”

She said that the International Labour Organization has consistently de ned an “essential service" as a service whose interruption would endanger the life, personal safety or health of the whole or part of the population.

Senneville said she had the same concern.

“ e rst change will be that employers won't negotiate,” Senneville said. “I think it's an incentive to employers not to bargain fairly. at will be the main impact.”

Senneville said that if workers bargain through collective action, Quebec employers could call on the government to ap-

“ e Canadian law should follow the international law regarding essential services,” Baril-Jannard said.

She drew attention to the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling in the Saskatchewan Federation of Labour case, which ruled that the right to strike is constitutionally protected under and essential to meaningful collective bargaining, in alignment with international law.

“We should always understand labour law as a dialogical process between an employer and a union,” Baril-Jannard said. “To maintain this [process] is essential to resolve con icts.”

With limited-term contracts

cut

and Quebec’s

court

ruling against French requirements, the future of francization is unclear

Maria Cholakova @_maria_cholakova_

In the months following Concordia University’s announcement that it will not renew any limited-term teaching contracts, many have raised concerns for a ected professors and their classes. But, some Concordia faculty warn that students hoping to learn French may also su er the consequences.

e decision to cut limited-term appointments (LTAs), announced in early November 2025, came as the university continues to ght signi cant budget challenges and aims to hit its $31.6 million de cit target for the 2025-26 scal year.

Now, some professors warn the decision could a ect the university’s recent francization e orts, precipitated in early 2025.

New French immersive courses

In April 2025, Concordia announced that it would launch new French language courses available to all students.

e decision followed a battle with the Quebec government over Bill 96.

Bill 96 was announced in October 2023, when now-resigned Quebec Premier François Legault and former Minister of Higher Education Pascale Déry announced that tuition rates for out-ofprovince and international students attending anglophone universities would be drastically increased.

e Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) government subsequently added a requirement for 80 per cent of out-of-province graduating students in English universities in Quebec to learn French at an intermediate level.

e requirement is part of ongoing government e orts toward francization—the expansion of French language use by social groups who had not before used the language as a common means of expression in daily life.

On April 28, 2025, Concordia announced that Quebec’s Superior Court ruled in Concordia’s favour in its case regarding tuition hikes and mandatory French requirements, meaning

French-language pro ciency requirements were removed.

Despite the win, the university stated in the same announcement that it had a “deep commitment to helping students achieve French-language pro ciency.”

According to Concordia spokesperson Vannina Maestracci, the university is still in discussion with the government on the speci cs around the mandatory French courses.

Now, in January, the French courses o ered under the program announced in April may have a shaky future.

Concordia’s new French curriculum was created by and is led by LTA instructor Geneviève Bibeau. Bibeau’s contract, along with those of her 62 other LTA coworkers, will not be renewed a er expiry. Some professors at Concordia question whether the program can feasibly continue without Bibeau.

One of those professors is Stephen Yeager, former chair of the English department and current English professor at the university.

Yeager says LTA positions at Concordia are tied to “really important program needs.”

“Every year, as chair, I had to write requests for LTAs, and I had to justify them according to our program needs,” he said. “If I had not been able to do that in a really compelling way, they would not have approved the LTAs. ey didn't just hand these things out. So the 63 positions are all 63 positions that are extremely important in one way or another.”

Chair of Concordia’s French studies department, Denis Liakin, said that grievances have been led, though he did not specify the nature of the grievances or to whom they were led. Liakin further stated that he hopes for a “successful resolution of problems,” but declined to comment on the situation further.

Bibeau also declined to comment, stating that there was insu cient information at the time of publication for an interview.

Maestracci says that despite the LTA cuts, the program is not in jeopardy.

“We have expertise in teaching French,” Maestracci said in an email to e Link. “ is expertise does not depend on a single LTA position. Once the francization pathway is fully implemented, it could lead to an increase in demand and we will reassess our teaching needs then, if that is the case.”

Anna She el, principal of and professor at Concordia’s School of Community and Public A airs (SCPA), believes that for any program to run, there needs to be proper university support.

“To actually develop the curriculum, you need continuity, you need some kind of stability,” She el said.

LTAs and public support

In the months following the announcement that LTAs will not be getting their contracts renewed, Concordia’s community has voiced its disapproval.

e advocacy group Concordia Academic Solidarity Coalition created an open letter early this month, calling for “more democratic governance and decision making.”

Since its creation on Jan. 9, the letter has received over 700 signatures, and counting.

Saraluz Barton-Gomez, a SCPA and political science student, worked alongside Sheftel over the summer to gather data about Concordia’s administration and the university’s financial constraints.

“In the Senate meeting in November 2025, the administration was questioned, with senators asking the university to justify these decisions with data and numbers,” Barton-Gomez said. “ e university’s leadership strategically makes their nances and data on sta extremely inaccessible.”

During the Senate meeting, a faculty member stated that they had not been provided any evidence supporting the need for layo s or numbers on budgets.

“We have never been given this information; so while we do not disagree that there's a crisis, I disagree that there's only one way to deal with it, because I've been given no evidence that this is the only way.”

Barton-Gomez believes that the administration’s nancial decisions a ect their most vulnerable faculty rst.

“ ese [LTA] professors each teach about seven classes, and are essential to the university,” they said. “ ey are hired on a year basis. eir contracts make them some of the most vulnerable faculty in the university.”

Maestracci reiterated that no LTA contracts will be renewed, but will be honoured until their expiration.

Yaeger thinks the university should take more time in updating its faculty, sta and students on its francization process.

“ e basic principle of making Concordia more bilingual is a very sound one for many reasons,” Yaegerhe said. “If there's a new plan that's re ned based on what they put into place last April, I don't think they should hide that.”

With les from India Das-Brown.

In the bustling neighbourhood of Cotes-des-Neiges—Montreal’s largest borough, known for its vibrant community of immigrants from di erent backgrounds—lies an essential service.

e Immigrant Workers Centre (IWC) provides legal information to some of the most vulnerable workers in Quebec.

According to Fatima Beydoun, a case worker who conducts intake evaluations for the IWC, some people take long commutes from outside the Greater Montreal Area just to access the services. ese include workers' rights education and help mobilizing around issues that can arise in the workplaces such as accidents, harassment and unpaid wages.

“Most people come from places where they sold everything before coming,” Beydoun said.

Accessing immigration brokers or lawyers to help complete permits or residency applications can cost hundreds of dollars. For example, Toronto law rm Matkowsky Immigration Law charges $250 for a 30-minute consultation and $8,000 for refugee claims as well as hearings.

For Azul Gonzalez, a public health researcher who immigrated from Mexico to Montreal in 2021, dealing with permits and immigration bureaucracy has been a di cult part of their integration.

Last November, a er paying $300 for a consultation with a lawyer, they began their application for the Programme Experience Quebec (PEQ). e PEQ is an accelerated immigration program meant to target foreign workers and students who graduated from a Quebec institution.

It was scrapped last November, and its sudden closure has le Gonzales searching for other avenues.

“When applying to any permit, it feels like you're putting all of your documents in a bottle and throwing it into the ocean, because there's no feedback until you get a yes or a no,” Gonzalez said.

Newcomers to Canada can be stuck in “bureaucratic limbos” according to Émile Baril, a postdoctoral fellow at Concordia University’s Institute for Research on Migration and Society.

“If your application is delayed,” Baril said, “some people can wait up for like 14 months, and they still need an income.”

Gig work organized through digital platforms is exible, and while it can give autonomy to workers, it is not always transparent with its pay structure. A majority of the time, Uber drivers, for example, are o ered di erent wages for the same trip as determined by an algorithm. It is unclear what factors are at fault for the dis-

crepancies, as reported by e Globe and Mail.

“Platform labour in Toronto and Montreal is built on a large pool of largely racialized young immigrant workers needing to make ends meet,” Baril outlined in his September 2025 research on food couriers in Canada’s major metropolitan cities, including Montreal.

Recruitment agencies also charge thousands of dollars to place migrants in domestic or warehouse work, which are both environments prone to workplace abuses, according to Beydoun. Domestic workers, the majority of whom are women, are more likely to face sexualized violence and to be pressured into working longer hours that aren’t properly compensated, she said.

e IWC Women’s Committee published a study last December revealing that 42 per cent of women without status in Quebec have faced sexual harassment in their workplace.

Warehouse workers, on the other hand, tend to be subject to unsafe environments and a lack of safety training in an environment where injuries are quite common. Over 80 per cent of Dollarama warehouse employees surveyed by IWC in 2019 reported excruciating back pain.

ese conditions put workers at a disadvantage, especially when they possess a closed work permit, which ties their status in Canada to a speci c employer.

“Unsafe environments for work are not just physically unsafe,” Beydoun said. “Usually, there's harassment that's also paired with it, or you can have a very apathetic employer who dangles your work permit like a carrot.”

Assia Malinova, a community organizer at IWC, primarily works with warehouse or factory employees.

Malinova says it can be intimidating for workers to report abuse or malpractices at work when they’re not familiar with what resources they can access. ese include services o ered by the Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST), Quebec's government body that manages employment standards, pay equity and workplace health and safety.

“We have a lot of workers that come here, people who have recently arrived in Canada, who don't know what the CNESST is,” Malinova said. “ ey don't speak the language, they cannot understand what rights are broken, so we help them identify, and we have to also help them make the claim.”

Budget cuts imposed by the provincial government at the

CNESST in 2025 further aggravated delays for workers seeking justice. Scapegoating by politicians and challenges of securing a permanent status in Canada contribute to the precarity of immigrant workers, according to Beydoun.

“We need to invest in communities and in housing," Beydoun said, "instead of scapegoating immigrants for the incompetencies of the government."

Cedric Gallant @gallant_perspective

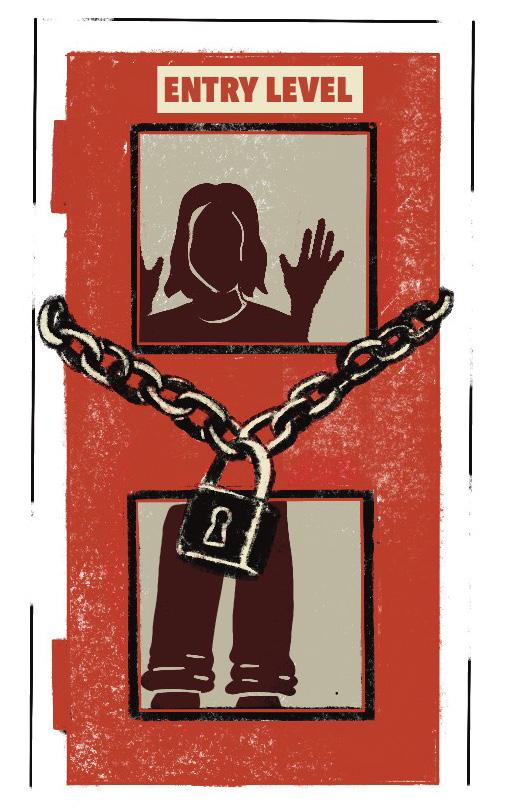

InAugust 2025, Canadian bank CIBC reported that 15 to 24-yearolds are struggling to nd work in Canada.

Canada's youth unemployment rate is slowly rising, with an over ve per cent increase between 2022 and 2025, and is considered to be “worse than average” relative to other age groups, the report said.

While the report does not provide a direct cause, it suggests that technological advancements are replacing some entry-level positions, especially those with high exposure and low complementarity with AI, meaning it would be hard for the two to co-exist in one workspace. is is cited as a potential cause for the worldwide trend of rising youth unemployment rates.

According to Statistics Canada, high-exposure, low-complementarity jobs are those "that may be highly exposed to AI-related job transformation and whose tasks could be replaceable by AI in the future."

Negar Kazemipour graduated from Concordia University in 2023 with a Master’s degree in computer science. She was one of the lucky ones, landing an internship and a fulltime job during her degree.

“I did not wait to graduate [to get a job,] because it was only a matter of six months between the time I applied and the time that it was starting to be really hard to get interviews,” she said.

To get her job, Kazemipour messaged directors and researchers directly, looking for work, focusing on human connection to secure her place. Some of her peers were not so lucky; some graduated two years ago, and they are still trying to nd work, according to Kazemipour.

“Ever since I got hired, almost three years ago now, I have been the newest member of my team,” she added. “No one else got hired a er me at the entry level.”

According to Kazemipour, the computer science industry has implemented AI for tasks such as database management, simple algorithm creation or folder nding. ese are jobs that were usually given to interns and entry-level employees to ramp up their skills.

Since the implementation of AI, Kazemipour said she hasn't felt any operational shortfalls at her company.

“Unfortunately, I don’t think the company is missing anything,” she said.

Encode Canada leads the way in youth advocacy for justice and human rights in relation to AI. According to the organization’s co-director, Aimee Li, technology disrupting the job market is not something new. But she said AI is unique in its disruption.

“AI offers a more unique angle,” Li said. “It is not only automating manual jobs like data entry, but it is also automating critical thinking.”

is automation of critical thinking is what Li and others refer to as “cognitive o oading.”

According to Li, since AI’s information is based on past data, the danger of o oading idea generation and decision-making to it is that it removes authenticity and innovation from the process.

“At the end of the day, AI is just a very sophisticated regression model that uses past data to predict the most likely outcome,” Li said. “It is unable to progress further than what we have already.”

She believes that, by replacing their interns and freshly-graduated employees with AI, companies are severing themselves from new ideas.

“Everybody has a unique perspective to contribute,” Li said. e introduction of AI also creates an inverse-pyramid within companies, according to Simon Blanchette, a management lecturer at Concordia University and McGill University, whose research o en specializes in AI. Blanchette explains that senior-level employees are o en running the company whilst AI does the work interns would do.

“I feel it is a shortsighted perspective, because you are pretty much killing your future pipeline of talent,” Blanchette said.

He added that many companies use AI as a cost-cutting strat-

AI has been a driver for change in the entry-level job market, forcing industries to adapt

egy: small businesses use it as a way to scale their company for cheap, whilst large corporations use it to stay lean.

“You’re dooming yourself to never training talent in-house, and always relying on hiring or approaching already experienced talent,” Blanchette said.

Economic factors, such as in ation and geopolitical tensions, need to be considered when discussing the entry-level job market, as they also contribute to companies being more risk-averse in their hiring practices, warns Blanchette.

“It is kind of a perfect storm; it is a di cult job market at the moment,” he said.

Some industries have more experience than others in dealing with AI’s disruption.

According to Christine York, translation professor at Concordia’s French studies department, the translation industry has been dealing with AI chipping away at their entry-level jobs since 2016, with the arrival of AI translation models like Google Translate taking up low-level translation work.

e industry was forced to adapt early on, and still faces diculty to this day, she said.

“ e bottom rung of the ladder is broken,” York said.

e professor says AI took away their low-level market almost a decade ago, and the advent of new large language learning models is also chipping away at the middle-market.

Middle-market in translation takes the form of in-house business documentation, memos and emails that used to require translators, but now can be bypassed by a ChatGPT entry. ough York explains that there is a detriment to that.

“People are realizing now that there is a cost to relying on machine-translation,” York said.

According to the professor, any document with a long shelf life—such as those published in scienti c or government contexts—carries too much risk to rely on AI for translation.

e industry has adapted to AI by integrating it into its process, explained York. Translators o en use so ware called the translation memory, which collects a database of the translator's work. In future translation work, the so ware will bring previous instances of sentences back, increasing e ciency.

“Yes, there is disruption from AI,” York said. “ ere is also this shi ing of what services are being o ered by translators and the translation industry.”

York also works as the academic director of Concordia’s co-op program in translation. Internships and entry-level jobs have been di cult to nd, she said, but she has found a certain stability in the opportunities on o er recently.

“[ e department has] worked very hard the last few years trying to deal with this sudden disruption,” she said, adding that they were educating employers and clients on the necessity of translators. “It was a di cult period, but it is starting to fall into place again.”

Hope remains. Blanchette believes that human contact remains the best way to get your foot in the door of the job market, even if only to make sure that your resumé is read by a human being.

AI literacy is also important. Skills like prompt engineering are now marketable to employers who are implementing AI in their companies.

Li agrees. She believes AI can make our lives easier, and that trying to escape it is unproductive.

“ e most realistic way to approach AI governance is through examining the technologies themselves, and the potential harm that they can do to the world,” she said.

Kazemipour encourages students not to lose hope. People are getting hired, she says, even if the gap between graduating and getting hired is a little bit bigger.

"Take your time, develop projects and put them on GitHub,” she said. “You have to push yourself to be higher than entry-level experience.”

AI has taken the role of a tool, similar to translation memory, where instead of competing with the translator, the translator uses it to become more ecient at what they do. Combining the databases from ChatGPT, the translation memory and the translator's experience increases their e ciency.

Aren da Costa Scarano @deconstructingaren

Pole dancing has become increasingly popular in recent years, moving beyond strip clubs into studios, gyms and performance spaces.

On Instagram, "#poledancer" has amassed over 5.7 million posts, and new studios continue to open in major cities. Even mainstream gyms like Callisthenics Montreal now o er pole classes. In a city with a strong circus and dance presence, pole is increasingly embraced as both a tness practice and an art form.

However, for most people, the image that comes to mind when thinking of pole dance is a stripper—and for good reason. Modern popular pole dancing developed in strip clubs, particularly by Black dancers in U.S. cities like Atlanta and Houston.

Chris is a retiring stripper who now primarily performs pole at events and shows. His name, like those of the other sex workers interviewed for this article, has been changed for safety.

Chris began learning pole in the strip club. He started working at gay clubs to make quick money.

One day, one of his coworkers noticed his potential and began mentoring him. Over time, Chris became far more interested in pole dancing as a sport and performance, rather than giving private dances and irting with clients.

“I have good memories of working at [a speci c club], but it’s really taxing, mentally. It’s hard work, and it can really take a toll on your mental health," Chris said. "Now I work at [a di erent club], where I get to dance on stage a lot more, and I’m way happier.”

e use of a pole in dance can be traced back to ancient Indian and Chinese sports, but these disciplines have little bearing on what is taught in most pole studios today. Instead, these distant references are o en used to distance the practice from its much more recent, club-based origins.

Scrolling through pole content online, you’ll o en nd "#notastripper" in the caption of a post. As Instagram becomes a key site for visibility and advertising, associating with sex work in the public eye is still viewed as unsafe or unprofessional by many. is lack of respect exists just as much o ine.

Many strippers are also in the greater pole scene, where many of them continue to face signi cant discrimination despite a growing cultural openness around sexuality.

Chris’ goal is to perform on stages full-time and he is working toward applying to the National Circus School of Canada. However, when moving into Montreal's broader performance world, he encountered numerous barriers.

“ ere’s a lot of stigma at auditions. People really discredit what you do in the club," Chris said. "As soon as you tell them, ‘Oh, I started dancing at clubs, that’s my background,’ they kinda shut you down, like, ‘Maybe stay in the club then.'”

Even in a city like Montreal, with a booming sex industry, judgment remains pervasive. While a stylistic change may be inevitable when your audience is di erent, sex workers are o en expected to cover their tracks to be considered legitimate artists completely.

Chris’s experience highlights how clubs and performance spaces function as two separate economies.

While they require many similar skills, such as stamina, creativity and stage presence, it can feel di cult to transfer the skills from one area to another. Formal training is o en treated as the marker of legitimacy, where who taught you can matter more than what you learned.

Julie is an active stripper and a coach at a circus studio. She rst learned pole in studios before beginning work at a strip club during university, an experience she says gave her valuable, o en overlooked skills like style and presence.

As a coach, much of her labour involves translating those embodied skills into teachable techniques for students with little or no dance background. While she doesn’t actively hide her work, she doesn’t tell just anyone, even within pole studios.

“ e studio I train at most of the time was very sex-worker-friendly, thankfully," Julie said.

Even in safer spaces like this, judgment persists. Julie shared a story about being in the changing room of that very same studio and chatting with a friend, who is also a stripper, about work. A girl she barely knew came up to them to say, “Wow, you guys don’t look like strippers.”

“What does that even mean?” Julie said. “What do you think strippers are supposed to look like?”

Beyond studios, sex workers face additional structural barriers. Various pieces of legislation, particularly in Bill C-36, or the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act, o en put sex workers in harm’s way.

Alice Quezada is an outreach worker at PIaMP, a non-government organization supporting the needs of sex workers, usually regarding nances, food and housing.

Quezada has seen rsthand how the legislation fails to protect workers and actively makes sex work more dangerous. Although strippers exist in a legal grey zone and cannot be prosecuted for their work, that status does little to protect them from everyday discrimination.

“Housing is the big one, really,” Quezada said. “As soon as you tell a landlord that you’re a sex worker, they’re signi cantly more likely to refuse to rent to you. Buying a house can be near impossible.”

Explicitly pro-sex work shows and events are becoming more prominent in Montreal’s nightlife, but these spaces remain relatively small.

Outside of them, sex workers are o en alienated from the broader art world not only because their labour is dismissed as illegitimate, but because their lived experience of dance is so di erent from those who were classically trained.

One person working to bridge these gaps is U.S.-based dancer Redd. A stripper since 2017, Redd launched Redd Light erapy in 2024, a virtual studio and resource hub by and for strippers that prioritizes mutual aid and self-organization where traditional infrastructures fall short

“Working at studios, it can be very gymnastics, pole-sports [centred], kind of, and that wasn’t what I was doing,” Redd said. “It felt like there was just a bar-

rier between what I was passionate about in pole dancing and what I was expected to teach.”

Redd spoke about how sanitized pole dancing has become. In her experience, many dancers seek the sensual expression inherent in pole’s connection to stripping, while maintaining a careful distance from sex workers.

Julie echoed this tension, saying that studio culture is o en marketed to "young corporate women" who she says may not have many opportunities for self-expression, but do not want to be associated with sex work.

In response, Redd has worked to create spaces that centre sex workers rather than alienating them. Her studio doesn’t just teach dance but also o ers meditation, breathwork, community meetings and nancial workshops.

As pole continues to explode into studios and onto stages, the question is no longer whether the art form can evolve, but whether it can do so without erasing the people who built it.

“Everyone is scared to come near sex workers,” Redd said. “Like, ‘ at’s dirty, I don’t wanna touch that.’ I wanted to create a space where strippers don’t have to feel dirty. Where they can feel appreciated like everyone else who puts hard work into their career.”

Lory Saint-Fleur @itsjustloryy

In the fall of 2024, in a small Montreal studio, turned half-bedroom-half-workshop, Iris en ciel took its rst breath.

Founder and leatherwork artist Isabelle Mills creates pieces rooted in queer intimacy, exploration and gender-a rming care. Deeply inspired by kink culture, Iris en ciel transforms objects o en associated with sexuality into intimate, intentional art.

“I want my work to feel intimate, not just sexual,” Mills said. eir introduction to working with leather was entirely informal. What started as a sustainable way to salvage fabric from a couch evolved into a series of experimental red-leather pieces.

Over time, Mills’ work became more intentional. Rather than sourcing leather from their immediate surroundings, they started visiting local leather shops like Cuir Di Zazzo. A residency with the Fine Arts Reading Room at Concordia University allowed them to deepen their understanding of the material.

In 2025, Mills began questioning how leather could be reshaped into new forms.

ey also added a major in sexuality to their current sculpture BFA to better comprehend the history and implications behind creating more personal pieces, something that continues to inform their work.

Leather became more than a medium of art; it became skin, something that carries weight, memory and responsibility.

Designing leatherwork is a challenging task. From a stranger’s out t to a moment in nature, anything can spark an idea, but the process of creation is slow and tenacious.

Each piece requires patience, physical endurance and a willingness to sit with the material. is slowness is intentional, resisting mass production and fast consumption.

Before a piece is made, Mills begins with a conversation. ey ask clients why they want the object, what it represents, and how it will be used. While clients are free to share what they’re comfortable with, the questionnaire is essential to the process. It allows Mills to connect with their customer and design something that re ects the client’s needs rather than imposing an aesthetic.

“When I create a piece, and someone nds it, and it ts them properly, it brings them so much joy,” Mills said. “I just want it to be exactly what they want.”

When it comes to custom and kinky pieces, Mills describes the process as personal and, at times, intimidating. To navigate this, they o en dra multiple designs, carefully considering materials, textures and how each leather will feel against the body. Every element is chosen with the wearer in mind.

For Zevida Germain, client of Iris en ciel, commissioning a custom piece was a collaborative experience. Rather than placing an order and receiving a nished product, Germain was involved at every stage of the process, from early conversations to nal decisions.

“It feels like you’re getting a piece that someone really cares [about]," Germain said. " ey care about the process, and they care about whether you’re gonna love it."

As a non-binary artist, Mills discovered a gap within the leather

community, where many pieces are designed primarily through a bondage-focused lens rather than as an expression of gender.

In response, Mills created the Heart Packer series—packers designed speci cally for non-binary individuals with vaginas. e series reframes a body part that’s o en sexualized or hidden by society, and frames it as powerful.

“I want the ambiguity of like, 'I’m not going to tell you what I have, but I want to feel like I’m powerful and I love myself in my body,'” Mills said.

rough Iris en ciel, Mills has found a way to make gender a rming pieces accessible, and their work continues to be incredibly important.

Beyond the studio walls and the personal client interactions, Iris en ciel’s work resonates within broader community wellness spaces.

For Omene Akpeokhai, president of Sex and Self Concordia, Mills’ practice re ects a shared commitment to non-traditional forms of care. e student-run organization provides sexual health, gender-a rming and wellness resources to students and community members.

“Trans, non-binary and gender-diverse people are frequently viewed through a medicalized lens,” Akpeokhai said. “To engage with such work through a creative and personal outlook, especially from someone who is telling a story through their experience, is sincere and lovely to see.”

Akpeokhai understands this labour as intentionally unbound from institutional frameworks, shaped instead by the needs and voices of the community it serves.

“ e work we do is quite untraditional to typical forms of sexual and gender-based educational programming,” Akpeokhai said.

Sex and Self Concordia previously featured Iris en ciel’s Heart Packer series in its rst-ever sex magazine, Sex(Ed.), which launched in March 2025. e magazine features student submissions across mediums, exploring sex and sexuality through personal experience.

Mills’ leatherwork is more than a simple skill or a cra ; it is a constant commitment to connect and help with their community. Iris en ciel o ers safety, a sense of validation and a sense of belonging that is o en denied to trans and non-binary people. eir art is inherently rebellious, as it resists what and where art is supposed to be.

“ ere’s this idea that the art I create needs to t in a gallery setting, and this is something I constantly struggle with as an artist [who] creates work that doesn’t normally nd itself in [those places],” Mills said.

e exploration of leatherwork through intimacy, gender and kinks continues to shock, but this art is not only meant to be looked at; it’s also meant to be worn, to be used. It doesn’t only live in queer spaces, it lives in the world and deserves to be seen.

At its core, Iris en ciel makes space for everybody. e intention behind each stitch and concept speaks to the work’s purpose.

With les from Safa Hachi.

Safa Hachi @safahachi

Long before performance or product, there are hours spent warming up bodies, answering emails, planning schedules and holding together work that doesn’t end when the creative part does.

e demand for artistic labour is shaped as much by circumstance and time as by talent. And it doesn’t look the same across disciplines.

For multidisciplinary visual artist Poline Harbali, labour takes a quieter, more continuous form, structured around routine, solitude and sustained focus.

Harbali’s days o en begin outside. She describes physical activity and time spent walking as essential to her process, a way of grounding herself before settling into work.

“ e experience of nature, of being in relation to nature, of being able to go outside,” Harbali said, explaining that time outdoors is not separate from her practice, but part of it.

Unlike artists whose schedules shi daily, Harbali approaches her work with a structured approach. She views her artistic practice explicitly as labour.

“I really see my artistic work as work,” Harbali said. “I have a schedule, I have a fairly rigid work routine.”

e work, she explained, takes up most of her time, leaving little room for other commitments, especially with her recent decision to return to school.

Making a living as an artist, however, remains di cult. Harbali draws much of her work directly from her own life, a reality she described as both generative and stressful.

“A large part of my work is very closely tied to my life. It creates a certain stress to see how much life experience is tied to earning a living,” Harbali said.

Despite the intensity of her schedule, Harbali does not frame her practice as a source of burnout. While long production periods o en lead to fatigue, she described that exhaustion as cyclical rather than harmful.

“It isn’t related to artistic work,” Harbali said. “On the contrary, it’s a place of joy, security and pleasure.”

Whereas Harbali organizes her labour around routine and sustained focus, poet Misha Solomon describes a practice shaped by fragmentation. He doesn’t follow a daily writing schedule, and his work rarely unfolds in a predictable rhythm.

Instead, writing happens between freelance contracts, academic responsibilities and the administrative labour that comes with publishing. Solomon explained that he does most of his writing “for a speci c purpose,” whether for a course, a writing group, or a prompt he has set for himself, rather than as part of a xed daily practice.

at lack of routine doesn’t mean the work is casual. Much of Solomon’s labour takes place away from the page entirely. Preparing for his upcoming book tour meant weeks of organizing logistics on his own, from coordinating with bookstores to reaching out to poets in other cities.

“Tour sounds glamorous,” Solomon said, “but I don’t have roadies. I don’t have an assistant planning it for me. It’s just me sending emails.” at behind-the-scenes work, he

noted, is rarely visible to audiences and rarely compensated. Payment for poetry itself remains inconsistent.

“Most journals do pay something, but that can be as little as $20 for a poem,” Solomon said.

As a result, Solomon supplements his practice through freelancing, teaching workshops, and academic work.

Even when people take his work seriously, Solomon is cautious about its framing. He acknowledges how lucky he is to be in a community with poets and scholars who take it seriously as a pursuit. However, he resists calling poetry a job outright.

“A job has a lot of connotations,” Solomon said, explaining that he feels less comfortable applying that language to his work.

What matters more to Solomon is the recognition of the practice as deliberate and sustained, rather than dismissed as something eeting or ornamental. Recognition may validate the work, but it does little to ease the instability that o en surrounds it.

Where Solomon hesitates to call poetry a job, trumpeter Rafael Salazar is explicit about what music requires. He laments that people rarely see or value the labour that makes that entertainment possible.

Salazar, a recent graduate of McGill University’s jazz performance program, described his days as physically and administratively demanding long before a gig ever begins. His mornings start with breathwork, not the instrument itself.

“Without breath, we don’t have vibration," Salazar said. "We can’t create without the breath."

Before touching the trumpet, he spends time preparing his body, emptying his mind and going through what he calls a maintenance routine, where the exercises are not creative but necessary. at routine alone can take over an hour.

“ at’s just maintenance,” Salazar said. “It’s not practicing music or anything at all.”

Only a er that does he move into actual musical work: learning repertoire, composing or preparing for upcoming gigs. On days with performances, he avoids additional practice altogether to preserve his body.

What looks like a three-hour set onstage o en amounts to six or more hours of labour. Salazar counts warm-up time, the gig itself and commuting as part of the workday.

“That’s without counting listening to music,” he added, noting that music remains a constant presence even outside active practice.

Much of that labour happens o stage and unpaid. Booking gigs, coordinating musicians, sending emails, tracking payments and following up on late transfers make up a part of the job.

Salazar described waiting weeks to receive payment for multiple performances, money that a ects not only him but the other musicians relying on that income.

Late-night performances create additional costs.

Many gigs end a er public transit has stopped running, forcing musicians to pay for expensive rides home. A er factoring in preparation, travel and administrative work, Salazar recalled a time when all that was le a er additional costs was around $90 for an entire night.

For Salazar, the issue is not simply low pay, but the perception of musicians.

“People don’t see the business behind the art form,” Salazar said.

If they did, he believes they would recognize musicians as workers providing a service.

Because of this, Salazar is deliberate about how he presents himself to venues. He insists on contracts, clear rates and professional boundaries.

Respect, he explained, o en comes before the music itself, through how a musician negotiates, communicates and asserts their value.

At the same time, Salazar is critical of how low pay has become normalized within the industry. When musicians accept poorly paid gigs or undercut standard rates, he argued, it drags wages down for everyone.

“People will play for peanuts,” Salazar said.

Across disciplines, the labour looks di erent, but the impulse to continue is shared. For Harbali, Solomon and Salazar, the work persists not because of its stability or reward, but because stepping away is rarely an option.

Despite the physical toll, long hours and nancial instability that shape their days, none of the artists describe their work as something they could simply give up.

As Salazar put it, “I have no choice. I feel it in my blood and my veins.”

With les from Sarah Housley and Ryan Pyke.

Yoan Safar & Nicolas Brunetti

Verylittle is more synonymous with life in the Great White North than the sport of hockey. For Montrealers in particular, the mania of the frigid arena has been a source of civic pride for over 150 years.

Indeed, ice hockey’s origins are deeply enshrined in Montreal culture. Although more ancient origins can be traced back to medieval Ireland and England, the rst organized game in Canada was played at the Victoria skating rink in 1875. Many of the o cial rules were published just two years later in the Montreal Gazette us, the home of the oldest hockey franchise in the world has cultivated an unrivalled history of dominance. Its players are not just athletes, but icons to fans both on and o the island. For many, the game has become a ritualistic endeavour, whether by directly lacing up the skates or watching it through the TV screen.

However, despite hockey’s seemingly uncontested monopoly on the Canadian athletic space, youth participation has signicantly declined over the last decade. It has dropped from over half a million in 2010 to just over 400,000 in 2022-23.

Unlike the other “Big Four” North American sports (basketball, American football and baseball), hockey has a signi cantly higher nancial barrier to entry. With the average cost of playing hockey reaching upwards of $5,000 annually per child, signing kids up for youth hockey has become an increasingly di cult decision for parents to make every year.

is phenomenon does not spare Montreal, with organizations across the city seeing similar trends in player enrolment and participation.

“I've heard of 15-year-olds having to quit before they get to do anything, because it's just too expensive,” said Kayli Dubé, hockey coordinator at Sun Youth, a Montreal-based organization that o ers low-cost practices for families in need.

What speci cally breaks the bank for these parents? According to the Associated Press, transport and equipment costs are major contributing factors, especially given the rate at which children grow, forcing families to replace gear frequently.

“Some normal skates, not even high-quality skates, could cost upwards of $300, which is crazy,” Dubé said.

For Geneviève Paquette, VP, community engagement and

foundation general manager of the Montreal Canadiens Children’s Foundation, it’s not just registration costs and equipment that hike the prices for families.

“If you add tournaments, which are not necessarily included in your registration fee, then things add up,” Paquette said.

Deepening worries on the ice e nancial strain is re ected on the ice, with more and more kids having to rely on organizations like Sun Youth and the Canadiens Children’s Foundation to nance the sport.

Once an issue that primarily targeted low-income families, Dubé noticed that this issue has gone beyond that.

“It's making it so that even middle-class parents are having a tough time a ording it, especially if they have multiple kids that want to participate,” she said.

Infrastructure is also a major contributing factor.

O entimes, rinks must split time between sports like hockey, gure skating and ringette. e lack of proper infrastructure is a key issue in the development of youth players, especially for those who may not be able to a ord a car or live far from public transportation, limiting their ability to seek alternative rinks. is can cut down on practice time, making it harder for kids to improve or build on their love of the game.

“It's already happened twice this year that our ice time has been cut unexpectedly because they needed the rink for someone else,” Dubé said. “It takes away from programs like us who don't necessarily pay these places as much for the ice.” ose o ering a helping hand

For families feeling pushed out of the ice, the reality can feel daunting. Programs such as Sun Youth and the Canadiens Children’s Foundation, built on affordability and inclusion, are stepping in.

e foundation has built 15 refrigerated rinks around Montreal, with a 16th on the way, so that youth can freely access NHL-standard hockey rinks until the snow melts. Sun Youth is o ering discounted practices ($100 for 24 sessions rather than $100 per hour in some cases) and, on top of that, o ers equipment for all the kids who need it.

Parents are also nding ways around the immense costs of equipment by nding second-hand gear.

“ ere's a store in the West Island called Play It Again Sports, and we'll go in there, so that de nitely makes it much more a ordable,” said Dan Aaron, a parent of a child playing in U11 hockey.

In Paquette’s eyes, there is a silver lining even in the face of decreasing general youth hockey participation.

“ ere's [also] a growth in girls' hockey, which I believe is quite interesting and probably linked to the increase of visibility for girls’ sports and girls’ hockey with the arrival of the professional women's league,” Paquette said.