Kara Brulotte

Students are having trouble accessing health care in Montreal, showing a broader pattern of sti ing bureaucracy and burnout in Quebec.

Concordia student Megan Brown saw the impact of these shortages rsthand during a recent ER visit.

“ ere’s six patients in the back with IVs in their arms, trying to get the help they need, but the nurses can't, because they're doing 15 other things at the same time,” Brown said. “Even the doctors are coming out to get patients as if they're nurses, and I think there's a tendency to not recognize the urgency of situations unless they're dire.”

A er visiting the Concordia University Health Services clinic and a private physician for a week of non-stop migraines, Brown was sent to the Lakeshore General Hospital ER. She waited 12 hours before receiving IV uids, a chest x-ray and an electrocardiogram to rule out blood clots or a heart attack— and was ultimately told that it was probably just stress.

“ e only concern for them was the fact that it could have been a heart attack, and they didn't really take the time to investigate any further because there were so many people waiting,” Brown said. “ e only thing they cared about was if I was dying.”

In Brown’s experience, the hospital was burdened to the point that accessing care was extremely di cult. e diculty to access care can also be seen in the number of Quebec residents without a primary care physician, which has risen from 22 per cent in 2019 to 31 per cent in 2022, according to an OurCare report.

is rise—along with an increase in family doctors going straight into the private sector—has sparked concern in the Quebec government, leading to several reform bills. Among them are Bill 83, which aims to keep physicians in the public system for a minimum of ve years a er they begin practicing. Another is Bill 106, which aims to tie the payment of family doctors to their achievement of performance goals set by the government.

However, these bills have been met with some pushback from doctors.

“As frontline workers, we know what we need, we know what our struggles are, and changes in policy don't always re-

ect the way that we experience it,” said Laura Sang, a family physician in Montreal. “I think it's very important to consider what we have to say and take it seriously.”

Sang pointed to the fact that family doctors are o en a patient’s rst point of contact and are responsible for guiding them through the healthcare system. Referrals, bloodwork, doctor’s notes and a large amount of the administrative work all go through family doctors. ey must follow strict practice rules, such as working within a designated region where most of their billing must take place, and they are prohibited from working in both the private and public systems.

Sang added that the government is quick to blame family physicians for broader issues.

“ ere's already a culture of lack of respect,” Sang said. " at's only been worsened by the villainization from the government on family doctors and blaming us for the inadequacies of the healthcare system when we are really some of the duct tape that's holding it together.”

Paul Brunet, the chair of the non-pro t healthcare advocacy organization Conseil pour la protection des malades, said that the focus should be on the rest of the healthcare system as well.

“ ey are pushing on the doctors so that they become more e cient,” Brunet said. “ e problem is that there are only 15,000 [doctors], whereas employees in this whole system are more or less 300,000.”

According to Brunet, eight out of 10 no-shows to hospital appointments stem from poor communication and administrative errors.

With the recent passing of Bill 83 and the potential amendments to Bill 106, the e cacy of the bills will be seen in the upcoming months and years. Additionally, an increase in family medicine residents this year could lead to more family physicians in the province.

Brunet said that the solution lies in action, rather than bureaucracy and contemplation.

“ e way I've always thought is, ‘What's wrong? What do we need more of?’” Brunet said. “We don't need more managers or thinkers. We need do-ers.”

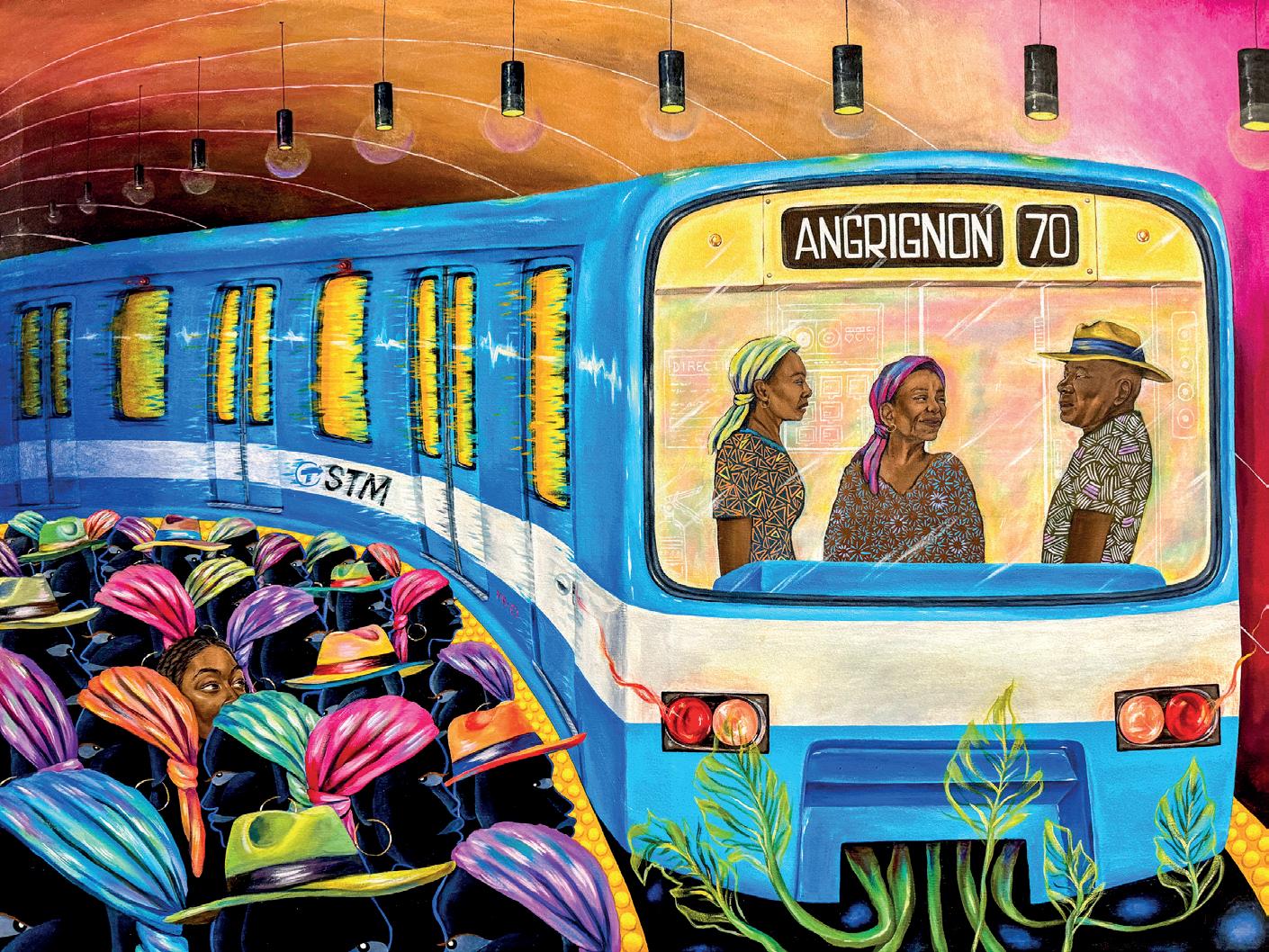

e Société de transport de Montréal (STM) maintenance workers’ strike is set to take place from Sept. 22 to Oct. 5, unless the parties involved reach an agreement. Bus and Metro schedules will be limited on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with Metro trains running only during peak hours: 6:30 a.m. to 9:30 a.m., 2:45 p.m. to 5:45 p.m., and 11 p.m. to the usual Metro closing time.

Carney allots $13 billion to ‘Build Canada Homes’

Prime Minister Mark Carney has allocated a $13 billion budget to the new Build Canada Homes agency. CTV News reports that the agency plans to oversee the construction of 4,000 a ordable homes on

six di erent federally-owned sites. Specific locations have not yet been announced, but Carney said some homes will be built in Longueuil. Construction is expected to begin next year.

Future Metro Blue Line station names released

Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante announced on Sept. 9 the names of ve new Blue Line stations, slated to open in 2031. ree of the new stations, Station MaryTwo-Axe-Earley, Station Césira-Parisotto and Station Madeleine-Parent were named a er prominent historical women from the Montreal community. Out of the two remaining stations, Station Vertières was named as a tribute to Montreal's Haitian community and Station Anjou was named a er its location.

named as a tribute to Montreal's Haitian

Quebec residents eligible to claim share in $500-million bread price- xing settlement

e Montreal Gazette

Loblaw Companies Ltd. has been accused of participating in an unlawful bread price- xing scheme for 20 years, according to reporting by . e accusation has resulted in a class-action lawsuit with a settlement of $500-million. Residents of Quebec who are at least 18 years of age in 2025 and who purchased packaged bread between Jan. 1, 2001 and Dec. 31, 2021, are eligible to claim their share of the settlement. No proof of purchase is required to le a claim.

Maria Cholakova

Several artists have withdrawn their work from Concordia University’s Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, joining activists in a boycott over what they describe as the university’s censorship of pro-Palestine voices.

On Aug. 18, Regards Palestiniens, Academics and Sta for Palestine Concordia, and the collective Stop Artwashing released a statement advocating for the full boycott of the gallery. e organizations claim that artists featured in a screening of the video installation An Image Before Last withdrew their work, leading to the screening’s cancellation.

e artists’ decision was made in protest against the use of their work “to artwash Concordia University’s suppression of Palestine solidarity at the gallery and on campus,” according to the organization’s statement.

According to a Facebook post made by the gallery, the two-day screening program of An Image Before Last was cancelled following the request of the participating lmmakers— Noor Abed, Batoul Faour, Yazan Khalili, Maissa Maatouk, Walid Raad, Ghassan Salhab and Ghinwa Yassine—to have their lms withheld from the program. is also includes the works of Chantal Partamian, which were on display in the gallery vitrine.

e gallery says the artists have deemed Concordia a site “incompatible for the presentation of their works,” according to the Facebook post.

e boycott comes a er months of tensions between the Concordia administration and the gallery’s artists and advisory council.

On Oct. 11, 2024, the gallery, alongside the Regards Palestiniens collective, organized a screening and fundraiser of the documentary Resistance, Why? at Concordia’s J.A. DeSève Cinema. On the evening of Oct. 10, the university’s Campus Safety and Prevention Services (CSPS) sent the gallery a notice for the postponement of the screening due to a need for additional information and review.

As an act of protest, the collective projected the lm onto the wall of Concordia’s Henry F. Hall Building at the corner of Mackay St. and de Maisonneuve Blvd. W. ere, they were surrounded by nine cop cars, including a cop van, and more cops than people, the collective told e Link at the time.

Two weeks later, on Oct. 31, 2024, around three dozen autonomous students led a demonstration in front of the Concordia GuyDe Maisonneuve building, calling for an end to police presence on

campus. e demonstration resulted in two arrests, which were made outside the gallery and followed by detention inside its premises.

A month later, in November 2024, the gallery hosted a silent protest against Concordia’s lack of action regarding student arrests on campus and the termination of the gallery’s then director, Pip Day.

In January 2025, ve members of the gallery’s advisory council resigned in protest following the dismissal of Day. In their resignation letter, the members said they believed Day’s dismissal was due to “her support of artists, students, and community groups who have spoken out on behalf of Palestinians.”

With the ongoing call for a boycott of the gallery, participating organizations have continued to demand on their Instagram that Concordia reschedule the censored Resistance, Why? screening and its fundraisers.

According to Vannina Maestracci, Concordia’s spokesperson, the university asked the organizers if they wanted to reserve the space for a later time and reschedule the screening. Space can be booked at the university by following the process for doing so and providing the relevant information.

Regards Palestiniens also demand that the university investigate the role of donor intervention in the gallery’s censorship, to divest from funds related to the occupation of Palestine, and to set up guidelines to prevent police brutality, student arrests and repression of Palestinian voices on campus.

According to an anonymous representative from Regards Palestiniens, the group's communication with the university has been met with “a pattern of avoidance and non-acknowledgement.”

“While the admin is aware of our demands, they have not been addressed,” they said in an email to e Link. “Neither

the university nor the new directorship of the Leonard & Bina Ellen gallery has acknowledged these events. eir ongoing silence is a deliberate choice to avoid engaging with their culpability in the political suppression that occurred on campus.”

According to Maestracci, the current director of the gallery has reached out to Regards Palestiniens representatives. She also claimed in an email to e Link that the university has not restricted any demonstrations or events.

“It’s regrettable that some groups have called for artists, including Palestinian ones, to boycott the Ellen Gallery, and by doing so are restricting these artists’ capacity to showcase their work,” she said.

Maestracci further clari ed that the gallery’s new director, Nicole Burisch, has established new protocols to avoid intervention by the police and is also working with CSPS to sensitize agents to the particularities of exhibition spaces on campus.

“ e gallery has no input into decisions made by the Montreal police,” Maestracci said.

Regards Palestiniens said they hope that the boycott serves as a protest against the exploitation of artistic work to artwash the university’s suppression of pro-Palestine voices both at the gallery and across campus.

How housing organizations are seeking to help tenants recognize their rights

Sean Richard

Concordia University attracts students from across the country and the world who want to pursue higher education in Montreal. Finding housing in the city, however, remains an issue that continues to impact students’ lives.

e university o ers residence at the Gray Nuns Building, Hingston Hall, and the Jesuit Residence, mostly reserved for graduate students. According to the Concordia website, on-campus housing can cost over $12,000.

With limited space and high costs, some students opt to play their hand in the housing market.

Rent in the city has increased by 71 per cent since 2019, according to Statistics Canada's quarterly rent statistics report published in June. is drastic cost increase has le many struggling to pay for housing and other basic needs.

Ela Piñero-Tabah is a second-year liberal arts student at Con-

cordia. A er her rst year renting and a bad experience with a previous landlord, she felt a lot of pressure to nd a decent apartment.

“It kind of felt like once you had a good enough choice, you kind of had to go for it because you wouldn’t nd something better,” she said.

Her previous landlord made her pay a security deposit, even though it is illegal in Quebec for a landlord to require a tenant to pay a deposit. ey can only request the rst month’s rent when a tenant signs their lease.

According to Piñero-Tabah, the renting process can be extremely intimidating when you are unsure of your rights as a tenant.

e Concordia Student Union’s O -Campus Housing and Job Resource Centre (HOJO) is a centre that provides education and housing information for students.

Ates Balsoy, an assistant at HOJO, rst used the organization’s

classi ed page to nd students looking for roommates or lease transfers. He says that most students ask HOJO for help with lease transfers and cancellations and to refuse rent increases.

“There are a lot of landlords, especially in Montreal, who give really high and exaggerated amounts for rent increases,” Balsoy said.

Tenants can challenge rent increases through Quebec’s rental tribunal, the Tribunal administratif du logement (TAL), which provides guidelines on rent adjustments that landlords aren’t required to follow.

According to Adam Mongrain, director of housing policy at Vivre en Ville, one solution would be a public rent registry that would allow renters to contest large increases.

Vivre en Ville, a non-pro t organization, created its own online rent registry in May 2023, which allows tenants to contest large rent increases.

Mongrain said he wants the Quebec government to take their project to facilitate the process.

“We can count on the government to have all the information it needs to make sure that all the information in the rental registry is available online,” Mongrain said.

For students like Piñero-Tabah, having access to resources remains crucial to eliminating the fears around nding housing.

“It can feel so overwhelming to go at that alone,” she said. “To protest the rise of my rent, am I really going to get into that and bring it to the government and to court?”

According to Mongrain, however, the government has shown no interest in running the rent registry.

“ e government said, ‘We don’t need this because landlords already have to provide this information,’” he said. “So, a rental registry would be redundant with the law.”

On top of rising costs, a large number of tenants are not aware of their rights. Namely, eighty-four per cent of tenants in Montreal are not aware of section G of the Quebec lease, according to a 2024 poll conducted by Vivre en Ville. Under section G, a landlord must provide new tenants with a written notice of the lowest rent paid in the last 12 months.

Mongrain said he believes that this particularly a ects students because of the prevalence of students living with roommates who sublet. According to him, the majority of these ten-

ants do not know the previous rent because they have never seen the lease.

Additionally, the passage of Bill 31 in February 2024 e ectively allows landlords to terminate a lease transfer for any reason.

“If [the Quebec government] wanted to make life easier for a student population, [they] would bring back the old terms for lease transfers,” Mongrain said.

Mongrain also proposed that the government give student housing providers di erent conditions, such as tax exemptions and exemptions from zoning bylaws, to build their projects.

In an increasingly una ordable city, Balsoy said tenants must organize and apply pressure on the government to recognize housing as a human need, not a market-driven one.

“I think as tenants we also need to bargain together [and] build a mobilization e ort to ght rent increases and a ordability,” Balsoy said. “Housing is not seen as a human right; it’s still seen as a commodity.”

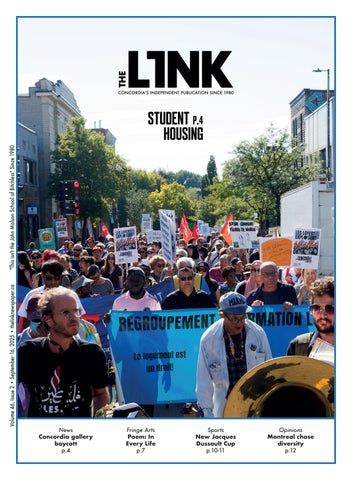

With costs on the rise, on Sept. 13, protesters gathered at Place-Saint-Henri Metro station for a demonstration organized by the Coalition of Housing Committees and Tenants Associations of Quebec (RCLALQ).

Attendees showed up to contest the rise in rent costs and recent modi cations to the calculation of rent hikes by the previous housing minister, France-Élaine Duranceau.

Duranceau admitted in a memorandum obtained by Le Devoir that the modi cations risk increasing rent prices for the most vulnerable tenants.

Noémie Beauvais works as a community organizer for RCLALQ. She said she hopes that the new housing minister, Sonia Bélanger, will be more sensitive to the issues faced by tenants.

According to Beauvais, the housing crisis targets students, as they generally work part-time and have to worry about school fees.

“What we are asking her to do is to completely withdraw the proposed regulation on rent setting and freeze rent increases for the next year,” Beauvais said.

Some organizers at the protest expressed that they aren’t hopeful that the situation will change.

“ e former housing minister, who made terrible decisions regarding the situation of tenants, was [promoted],” said Carl Lafrenière, a community organizer for the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain.

For demonstrators like Lafrenière, the government has sided with landlords.

“ is clearly shows that it is not a question of person, but is really the vision of the CAQ (Coalition Avenir Québec),” Lafrenière said.

Defne Feyzioglu and Matthew Daldalian

Polarization on social media is no new phenomenon. But researchers and student activists at Concordia University are concerned that arti cial intelligence can take it to the next level—and that platforms aren’t prepared to stop it.

“Instead of being shown footage of what’s happening or content from the journalists who are reporting on it, we’re instead seeing overly dramatized AI art of things we should care about politically,” said Danna Ballantyne, external a airs and mobilization coordinator for the Concordia Student Union.

“It really distances people and removes accountability,” Ballantyne added.

Her worry lands as new Concordia research warns that arti cial intelligence can supercharge polarization online.

In their paper on maximizing opinion polarization using reinforcement learning algorithms, professor Rastko R. Selmic and PhD student Mohamed N. Zareer found that reinforcement-learning bots can sow division on social media networks with minimal data by pinpointing in uential accounts and inserting targeted content.

“Our goal was to understand what threshold arti cial intelligence can have on polarization and social media networks,” Zareer said, “and simulate it […] to measure how this polarization and disagreement can arise.”

Instead of needing access to private data, the researchers’ simulation showed that simple signals like follower counts and recent posts were enough for an AI algorithm to learn how to spread division.

“It’s concerning, because [while] it’s not a simple robot, it’s still an algorithm that you can create on your computer,” Zareer explained. “And when you have enough computing power, you can a ect more and more networks.” is concern goes beyond academic theory. Zareer argued that the ndings raise concerns about the responsibilities of platforms and policymakers to safeguard public discourse.

However, Zareer said that the question remains: who decides what counts as harmful manipulation and what counts as free speech?

“ ere is a ne line between monitoring and censoring and

@defne.fey @mattdaldalian

trying to control the network,” Zareer said.

He added that platforms risk tipping into censorship if they clamp down too aggressively, yet do little if they ignore the problem altogether.

“If you are trying to detect these kinds of bots from happening, in uencing the network, and creating echo chambers, then that’s extremely important,” Zareer said. “However, if you move the control so much, then you will not be able to share [your opinions].”

While researchers warn about AI destabilizing online discourse, those involved on campus worry that AI risks replacing lived realities.

Ballantyne said the shift from seeing real footage of events online to seeing dramatized, political AI representations undermines years of organizing rooted in personal storytelling and community relationships. She said online, AI-generated content can create the illusion of awareness without the substance of real engagement.

“AI completely scraps that,” Ballantyne said.

And for some students, the presence of AI on social media is a downright invasion of privacy.

“[It’s] always there, anytime you want to type a message to someone, it’s always suggesting [something],” said Concordia student Valérie Chénier. “It’s just invasive and annoying.”

said it organizing will adapt.

Meanwhile, Ballantyne said she believes misinformation generated by AI is advancing so quickly that it may mislead the average digitally literate student. What once seemed laughably fake is now sophisticated enough to spread confusion, she explained, and that pace of change makes her uneasy about how student engagement and

Algorithms o en bene t from steering attention in particular directions, sometimes toward extreme hateful and misogynistic content. For students who are already relying on social media to engage with issues, Ballantyne worries this makes it harder to tell what’s genuine.

“I kind of hope that people are able to balance that with what they see in the real world, with what they see from the lived experiences of their friends and colleagues,” she said.

Last February, as the city was teetering back to normalcy after back-to-back historic snowstorms, Montrealers put on their dancing shoes and lined up along snowbanks on St. Laurent Blvd. on a Saturday morning.

Their destination, though, was not one of the many clubs that dot the commercial artery.

They were waiting to enter Cass Café, where DJ Bassil Sawaya was spinning groovy French house music. He wore a T-shirt with the words “cool people party at 11 AM” and a drawing of a croissant with dancing legs.

The usually calm and brightly lit café, a neighbourhood refuge for those seeking to get some work done, dimmed the lights and cleared the tables. People danced and shouted to beats, the ambience accentuated by hisses from milk frothers, which had morphed into fog machines. For uppers, there were espressos and croissants aplenty.

No alcoholic beverages were in sight.

That was the first of nine morning DJ sets that Lisa Rey, co-owner of the alcohol-free events company Croissound, has organized across Montreal and Paris. The biggest event at Le Central drew 1,500 people.

Inspired by TikTok videos of morning raves in Los Angeles, Rey and her boyfriend, Sawaya—both in their early 30s—decided to create a sober alternative to their erstwhile booze-filled, late-night party lifestyle.

“We're not drinkers anymore. We don't go out. So the alcohol is just less trendy, I feel, for our generation,” Rey said. “Everybody that is coming is saying that you don't even need to drink. The energy is so high.”

While the majority of guests at Rey’s events are between the ages of 25 and 35, they attract everyone from kids to grandparents and are a hit, particularly among sober individuals.

“[Sober people] appreciate that they have a party where the people around them are not drinking, so they don't feel alone,” Rey said.

Croissound represents one of many innovations—events, spaces and dealcoholized drinks—that are gaining popularity across the country among sober people and those seeking a different relationship with alcohol.

Looking to the West Coast, Angela Hansen founded Mocktails, a Vancouver-based “alcohol-free liquor store” last year, based on her own experience with alcohol. After getting sober two years ago, Hansen, who likes hosting parties, looked for alternatives to her favourite drinks.

While she discovered great products, Hansen realized there was no single place to shop for mocktail ingredients catering to people like her.

Despite initial skepticism from landlords and investors, Mocktails became an instant success.

“We opened our doors and there was a flood of people, there was a ton of media attention,” Hansen said. “It really was that story of ‘build and they will come.’”

Over 500 products line the physical and online store shelves of Mocktails.

From local beers, wines and spirits with names like Abstinence, Dr. Zero Zero, AmarNo, Free Spirits, Monday Mezcal, the variety is a far cry from the early days of sugary or fruity mocktails or the one non-alcoholic beer found at the end of a menu in bars.

A NielsenIQ study showed that the non-alcoholic beverage market grew by 24 per cent between June 2023 and June 2024 in Canada. Another NIQ study showed that alcohol sales declined by 0.8 per cent in 2024 compared to the previous year.

Jordan LeBel, a professor at the John Molson School of Business who specializes in food and beverage marketing, said that two major factors came together to fuel the phenomenon.

“[Gen Z] had a very different attitude towards health and how alcohol consumption fit into their worldview and their definition of health,” LeBel said. “They were also a little bit more adventurous and explorers in terms of seeking out different flavours, unusual flavour combinations.”

About a decade and a half ago, when members of Gen Z first came of age, they consumed less alcohol than previous generations (although recent NIQ research shows a shift).

In addition, wider social media trends like “Dry January” and “Sober October” showed that people consumed less alcohol by choice. LeBel added that, starting with millennials, the preference for locally sourced products increased.

LeBel said the industry caught on to these changing consumer preferences and developed new products.

“Now distillers have figured out, ‘Oh gee, people like local stuff. All right, so let's use herbs and fruits and things from Quebec to flavour gins or vodka or what have you, and have something uniquely local in the hope of seducing consumers,’” LeBel said.

Both distillers and flavour manufacturers like International Flavors & Fragrance are also increasingly using technology like AI to digest large datasets on consumer preferences to create new permutations and combinations of flavour mixes, LeBel explained.

All these innovations help create new and sophisticated non-alcoholic versions close to the real deal, which then find purchase among consumers.

“You look at mocktails [now], they're a little bit more complex and interesting in terms of the flavour, the drinking experience they provide,” LeBel said. “So, of course, that has turned on more people to this.”

From a marketing and distribution perspective, too, companies started to dedicate more shelf space to non- and low-alcoholic drinks.

For example, Croissound founder Rey recently signed a partnership with the Société des alcools du Québec (SAQ), the Quebec government-owned liquor store chain, to promote all non-alcoholic offerings at their events.

Emerson Pereira, a cocktail bartender who works at Pub Saint-Pierre in Old Montreal, said he added a non-alcoholic Negroni to the menu at the behest of one of his amaro suppliers who launched a non-alcoholic version of the spirit.

While the drink has been a hit ever since the bar introduced it, Pereira felt its popularity could rise even further if the prices came down. Right now, the bar prices the mocktail just a couple of dollars below the classic Negroni, even though the regular and dealcoholized bottles of spirits cost the same, around $30-35 apiece.

“We cannot charge the same because I'll be thinking I'm ripping someone off if they have a Negroni with alcohol and one non-alcoholic,” Pereira said. “I'll be damned the day that I'm gonna sell them for the same price.”

LeBel said he was unsure to what extent the prices of dealcoholized spirits might affect the growth of the industry. He added that smaller distillers who produce over two-thirds of the dealcoholized spirits might lose the ability to reduce prices if they don’t sell a high enough volume needed to achieve economies of scale.

In addition to the relatively low volume of dealcoholized spirits, Hansen pointed to the production process itself as the source of the high costs. But she doesn’t see that as a deterrent to customers.

“You have to bring everything to the alcohol state, and now you have to remove that alcohol. So that's a whole other process that costs,” Hansen said. “Once you explain that to the customer, they completely understand.”

Hansen said that the nascent industry is seeing rapid growth as more people discover the products and figure out how they fit into their lifestyle.

“It's just life changing for some people,” she said. “They can now enjoy something with their friends and they don't feel like they have to have the alcohol included.”

17

Rawan, Khaled, Mohammed, Obaida, Mohammed, Mohammed, Bashshar, Fawzyeh, Mohammed

My people are hopeful

Carrying the keys to doors le ajar

We will need them when we return.

16

In honour of the children murdered by israel in the 2021 attack on Gaza and all those taken from us in the years of genocide since.

Ibrahim, Tawfeeq, Rashid, Islam, Said, Lina, Muhammed. You remind us of what we are ghting for, Not what we ght against.

at for each story cut short, ten more are written And in the same way that I was chosen to love you, I was chosen to lose you

So that I might speak of the truth you le behind.

15

Dima, Ahmed, Mahmoud, Mohammed

My people are rooted

In the Fall, we harvest Olives and dates.

In the Winter, Strawberries, oranges, lemons, and thyme In the Spring, Almonds and watermelon

All year long, we bury our dead.

Hala, Lina, Yahya, Hana

14

Before anything, we are children. Future troublemakers, problem-solvers, Advocates and visionaries.

13

Yousef, Hamada, Suheib, Ahmed, Yazin, Hala, Doaa

Before anything, we must learn

To love ercely, And grieve deeply, And pray for a liberation without prerequisites or conditions.

So that we might walk on the beach, And slice an orange, And take a hot shower. And grow old, And die before our children do.

12

Tala, Hamza, Meera, Abdallah

My people are strong Digging through rubble with bare hands Unearthing fragments of a shattered past They say they stand in solidarity with the children they slaughtered but never the living.

11

Rafeef, Yusef, Ibrahim

You were their eyes and ears. My heart and soul, Telling the stories that are woven into the tatreez of our grandmothers’ thobes and grow in the roots of our olive trees.

10

Ammer, Yahya, Raha , Dima

My people are proud Grounded and principled, We would choose this life in every lifetime Dancing not to teach lessons in paci city Our smiles are not to relieve your discomfort.

9

Bilal, Ameer, Yara, Dana, When it was all over, We could have sat together on my balcony drinking mint tea. And you could have told me at my love had met you Even when my hands and words had not.

8

Maryam, Abdulrahman, Zeeyad, Hussein, Islam, Yehya, Zain

In our homeland,

Every person is a storyteller.

And every grain of sand is a witness. In our homeland, to speak the truth you must face it directly, Be with it, And not let go.

Ismail

7

At night, when it feels too hard to bear, I go back to the land.

To the place where we grew,

Where you lived.

And I wait.

6

Aymen, Osama, Rula, Amira, Marwan, Adam, Buthaina, Do you remember

How the sea carried warnings

We dared not say aloud, And li ed them to places we might never reach?

Do you remember,

How you taught me to tie hope like the string of a kite, Even when the winds were still?

5

Amir, Zaed

My people are eternal

Never begging for sympathy from a cruel world, we rise and resist. I will miss the sunsets over the cities I couldn’t rebuild.

Baraa

4

What part of his humanity was hardest for you to hold?

Was it his grief?

His rage?

His power?

3

Adam, Mohammad, Mariam, Mouna

And while this world forgets us, We will etch our names into the limestone cli s And the so bark of our olive trees.

We will scatter our stories like wild owers, beyond checkpoints and barbed wire

To the places we cannot follow.

2

Yazan, Hoor, She’s running. First it’s the slapping of her shoes. en the thumping of boots e rst shot is so loud my hands y up to keep my head from splitting in two.

1 Year

Mohammad, Qusai, Ibrahim, Mohammed, Hoor

My people are patient ey said the old would die and the young would forget But the land remembers for us.

Throughouthistory, the human body has shouldered the burden of beauty standards that exclude the vast diversity of shapes, sizes, and identities that make us unique.

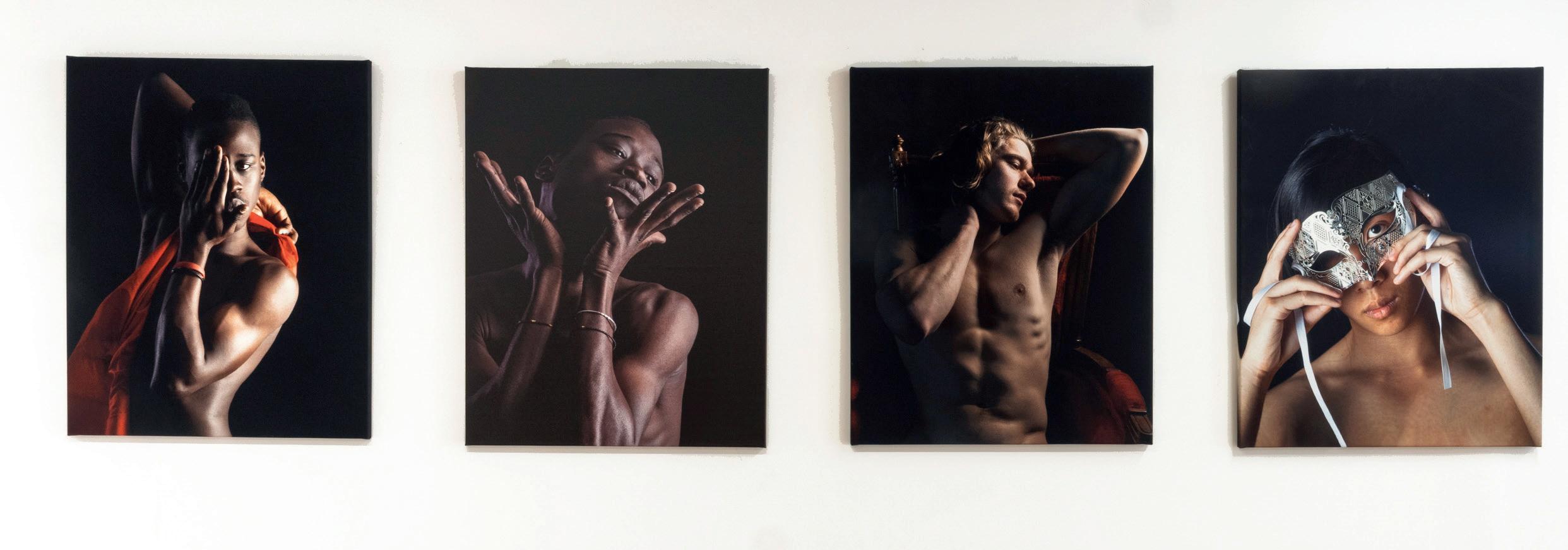

e exhibition e Body in Question? explores di erent understandings of the body, using photography, paintings and other mediums to showcase the vulnerability, beauty and diversity of bodies that fall outside the norm.

e show displays nine artists from contrasting artistic and cultural backgrounds, o ering a multitude of perspectives on the human body.

e curator, Professor Norman Cornett, highlights the need to move beyond binary concepts of the body and the makeshi boundaries of the human condition. As a doctor of religious studies, Cornett sees the exhibition as a transitional space between the material and spiritual realms.

“Everything we think, everything we wish, everything we feel, everything we desire, everything we wish for, it’s bodybased,” Cornett said.

Upon entering the gallery, visitors experience a sense of freedom. e exhibit frames the body as not just a subject, but a crucial part of identity, vulnerability and strength. From nude paintings and drawings to more mixed-media pieces, the show invites attendees to rethink learned narratives about the body.

e exhibit a rms that the body can not be merely de ned by its size, or its sex, or its colour. Professor Cornett assembled artists whose work challenges and rede nes the conventional view of the body. He sought out artists with a strong voice and something meaningful to say.

Among them is Won Ch. Kimetarx, a PhD student in architecture at Université du Québec à Montréal, who merges academic and artistic approaches. His work uses a complex symphony of lines, motifs, and buildings to represent the human body.

“I would like to translate the theme itself in the form of the human body in the architectural world and describe the world of architecture that is not dominated by modernist ideologies

or spatial-centric,” Kimetarx said.

Other artists, such as Josée St-Amant, o er a di erent outlook on the human body. Her pieces explore the female nude body, the human form at its most original and authentic state. By removing the sexual associations o en tied to nakedness, StAmant invites the viewer to see the nude as divine and natural.

“I hope that the audience will bring home a new look on nudity, to be more comfortable, to realize that nudity can be ancestral, natural and beautiful,” St-Amant said.

Comparatively, Olivier Bonnet approaches the female body through bright colours and vintage-inspired imagery, drawing from his experiences growing up all over the world. ough rooted in a heterosexual male gaze, his work treats the female form not as something to dominate or conceal, but as something to celebrate.

While St-Amant’s pieces invite viewers to confront nudity as natural, and Bonnet invites viewers to appreciate the aesthetics of the female body, other artists in e Body in Question? take the body in opposite directions.

rough photography, Claude Gauthier captures the body in motion, using live models from around the world. His work explores the male body through the male gaze, bringing forward the intersection between the body and queerness.

Annouchka Gravel Galouchko and Lisette Duquette also delve into the male body, but from a female perspective. Duquette’s mixed-media works combine erotic drawings with bright colours and images, all superimposed with a computer. Together, their works allow for a complex take on male vulnerability.

e exhibition also features the work of artists like Soon Ja Park, Erik Nieminen and Lousnak, whose perspectives further enrich the conversation. e Body in Question? demonstrates that there is no singular way of seeing or understanding the human body.

For attendees such as Steven Loucks, this exhibition offered an unexpected entry point into art.

“When you rst look at a piece, you might think it’s nothing. But if you study it, you can nd something human inside it,” Loucks said. “ at’s why galleries put seats—you need to sit and really look.”

e Body in Question? exhibition will run at Éclats 521 until Sept. 21, 2025.

Geneviève Sylvestre

@gen.sylvestre

Tucked away at the edge of Jeanne-Mance Park lies a small bar bubbling with energy, community, joy and pride.

Co-op Bar Milton-Parc, or BMP for those in the know, is a solidarity cooperative that hosts a number of community events, including the bi-weekly Queer Karaoke.

Always free and always fun, Queer Karaoke o ers members of the community a space to gather, belt their hearts out and order a late-night vegan poutine.

Not tied down to one genre, the night bounces from pop divas to guilty-pleasure 2000s soundtracks, with every song met by a rush to the mic.

According to Avery Haley-Lock, co-host and founder of Queer Karaoke, the project came from a desire to have more inclusive queer spaces in the city.

“ ere's a lot of physical spaces […] and places in the village where when you go it's very dominated by cis men, and speci cally cis gay men,” Haley-Lock said. “But, we wanted to see more spaces that were kind of just a mix of queer people, and not really speci cally for any one person.”

Out of this desire, Haley-Lock and some friends organized an “o -the-cu ” queer open mic event at the at-the-time brand new BMP, which drew a decent crowd.

“It didn't even have taps yet, like beer taps. ey were serving stu out of cans, so it was really new, and it was looking for events to bring people in, so that made it really easy,” Haley-Lock said.

Following the event’s success, they turned their open-mic into a series, this time with a karaoke segment. Two years later, people still gather at that same bar under the same garland of fairy lights to sing and be in community with other queer people.

Silas Dixon, a member of BMP’s board of directors, says having queer karaoke as a xture at the bar has been nothing but a positive experience.

“ ese are people who were involved with the bar from the beginning of it, so we have very intimate personal relationships with them,” Dixon said. “ ey're great friends, and it's just kind

of nice that they choose to keep coming back to our space.”

Dixon adds that growing in symbiosis with Queer Karaoke has been a great experience for BMP, with bigger and bigger crowds drawing more people to both the event and the bar.

“In tandem, I think that it feels important to have this event be in a space that feels safe for people to come to, that feels like home, that feels, you know, inclusive,” Dixon said. “Because I don't think you can have an event like this at any venue.”

Gabriel Gaston, an organizer and co-host for Queer Karaoke, found out about the organization a er a friend invited them to Haley-Lock’s rst open mic. Intrigued, they later received an invitation to the rst o cial Queer Karaoke event, and from there, he was hooked.

“It felt very serendipitous […] having friends dragging me to this event and to connect with Avery,” Gaston said. “I got involved with it shortly a er because Avery saw my potential. As they like to say, they're like, ‘I scouted you.’”

Avery agreed.

the LGBTQIA2S+ community in Montreal’s youth, Gaston thinks it's important to foster safe spaces in the current political climate.

Dixon agrees, saying that collaboration with queer organizations remains a priority for BMP, which is sta ed entirely by queer workers.

“As workers, we want the space to be shaped around, you know, an idea of community,” Dixon said. “Obviously, we bring in all kinds of di erent communities into the space, but it's really nice that we're able to have inclusive events for everyone.”

For Haley-Lock, it's especially important for the event to be not only trans inclusive but also “trans forward.”

“It's more important now than ever that trans people can nd each other and can nd community and solidarity while our very existences are under attack,” Haley-Lock said. “I'm trans and society does not want me to exist, you know, and that's scary.”

“He's putting his whole soul into this performance,” Avery said, “and I'm like: ‘OK, theatre kid, I see you.’”

Jonah Doniewski, the Concordia University Fine Arts Student Alliance (FASA) student life coordinator, regularly attends Queer Karaoke events. First dragged to an event by a friend, they now try to attend as many as possible.

they free

Wanting to share the experience, Doniewski helped organize a free event between Queer Karaoke and FASA for the Concordia student body at the start of September.

“On that [ rst] night I had a really good time, and I met some really cool people,” Doniewski said. “So then I sort of kept going repeatedly every second weekend and became familiar with the people organizing it because I was there so o en.”

For Gaston and Haley-Lock, keeping the events free and accessible to everyone is part of the core values of Queer Karaoke, especially as queer and trans people have an increased chance to earn lower incomes, experience job discrimination, and face barriers in advancing employment.

“There's not really a lot of spaces anymore that you can go to that are specifically queer, not just queer friendly but queer forward and trans forward, where you can just exist and that's not gated by money or a cover charge,” Haley-Lock said.

Gaston notes they can keep costs low thanks to BMP letting them host the event for free, which allows them to pour their own money into the little extras.

“For little things that we want to add to the event, like the lm photos that I started taking back in the day and continue to take, that's money coming out of my own pocket,” Gaston said, “and that's just me and my own choice to put that money back into my community.”

Given the rise in hate crimes targeting sexual orientation in Canada and the growing intolerance towards

BMP holds Queer Karaoke events every other Saturday, with the occasional open mic or collaborative event thrown in the mix. Information for all upcoming events can be found on the organization’s

The case competition program takes a fresh approach to its sports coalition this season

Samuel Kayll

@sdubk24

Business, accounting, management, sustainability—sports?

For the John Molson Competition Committee (JMCC), all these are possible. Based out of Concordia University’s John Molson School of Business (JMSB), the JMCC selects the school’s top minds to compete in academic case competitions regionally, nationally and internationally.

With top-three nishes at major competitions like Jeux du Commerce (JDC) and JDC Central (JDCC), JMCC has built a reputation as a powerhouse in the world of case competitions.

But these contests go beyond academics, featuring sports, debate, social studies and other disciplines outside business. is balanced approach creates a more well-rounded competition with a variety of xtures, not just a select few.

Ivan Belichki competed during his rst two years at JMSB and rose to the position of VP of sports this year. He sees athletics as an essential part of JMCC’s competitions, providing students with an opportunity to compete in areas they may have missed out on.

“Being in university, it's hard for people to nd time to play sports,” Belichki said. “ is is an opportunity for people to be part of a team.”

JMCC co-president Alexandre Siriwardhana played AA and AAA basketball before joining Concordia’s business program. He expressed his excitement at the opportunity for JMSB students to represent their school in a familiar, personal way.

“ ere are a lot of athletes that decide to go to business school and don't pursue playing sports at university level,” Siriwardhana said. “It gives an opportunity for students to still play at a competitive level at some of the biggest competitions in the country.”

Team selection begins early, with the committee selecting its cohort of athletes and training them throughout the semester.

For gatherings like JDCC, schools compete in two sports: one revealed at the beginning of the year, and a “surprise sport” unveiled a month before competition. is leads teams to search for well-rounded athletes, not just specialists.

While sports don’t get as much attention as academics, they highlight the friendly rivalries between schools. JMCC co-president Alexandre Tawil celebrated the athletic events as a way to provide a di erent form of competition.

“In sports, it's much more confrontational, where students have to manage di erent emotions,” Tawil said. “It resembles fair play and sportsmanship, and all of these values that are extremely important to thrive for.”

However, over time, the divide between the athletic and academic delegations at JMCC has only grown. Athletes train separately from their contemporaries in business, divided by elds and classrooms. Even during competitions, the sporting events are o en held separately from the host schools. is can lead to a clique-like divide between the delegations.

As VP of sports, Belichki wants to change that. As a competitor, he saw the disconnect rsthand—and this year, he plans to bridge the gap.

“I'm picking the best team that's gonna go and bring a win back for JMSB,” Belichki said. “But I'm also looking for players that are going to reach out and make friends and build their team around the rest of the delegation.”

Spirit and participation play a role in team success—not just in team chemistry, but as a legitimate area of scoring that helps determine the top school. Tawil, alongside Siriwardhana, made a point of emphasizing connection in the coalition’s mandate and uniting the team before competition.

“A er competition, that's when students are usually the closest because they went through those two days of intense competition and they bonded,” Tawil said. “And it happens every single year— people say, ‘I wish we had bonded before the competition and we could have gone there already close.’”

As the JMCC gears up for its yearly competitions, past successes have the team riding high on expectation. But there’s also a sense of change. And Siriwardhana believes that change can push the coalition to even greater heights.

“We want to show to every other school that JMCC dominates in every single aspect— academics, sports, etc.,” Siriwardhana said. “Last year we dominated at JDC and JDCC, but this year we want to leave a lasting impression that we can take on any discipline.”

Coaches and colleagues reflect on the man who helped transform Francophone football in Quebec

Alex Hall

Quebec university football’s top prize has a new name. Earlier this season, the Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec (RSEQ) announced that the historic Dunsmore Cup would be renamed the Jacques Dussault Cup.

is gesture honours Jacques Dussault, a trailblazing coach from Quebec City who elevated Francophone representation in the sport and helped make Canadian football one of the province’s fastest-growing pastimes.

Dussault began his coaching career in 1975, with early stops at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières and the University at Albany, where his relentless work ethic quickly earned him respect as well as valuable coaching relationships.

In 1982, he broke new ground as the Canadian Football League’s (CFL) rst Francophone coach, joining the Montreal Concordes’ defensive sta under Joe Galat. e decision held

tremendous signi cance for a community eager to see greater representation on CFL sidelines.

“ e Francophone community was emerging in the football ranks right around then,” recalled legendary ex-Concordia coach Pat Sheahan. “To have the rst French-Canadian coach was a very symbolic appointment, and a well-deserved one at that.”

For Sheahan, who coached in Montreal throughout the 1990s, Dussault’s impact extended beyond X’s and O’s.

“He was a hard worker,” Sheahan said. “He put in long hours, and of course, he did a lot of work developing football across Quebec, so he was truly a marquee gure.”

A er ve seasons in the CFL, Dussault returned to the collegiate ranks following the Alouettes’ dissolution in 1987, coaching at various programs across Quebec and the Maritimes, as well as internationally.

In 1991, he led the Montreal Machine, Canada’s lone World League of American Football franchise, before rejoining the Alouettes in 1997. In 2002, he was named the inaugural head coach of the Université de Montréal Carabins, laying the groundwork for one of Quebec’s premier university football programs.

From sidelines to spotlights

One of Dussault’s greatest strengths was his ability to connect not just with players, but with the media and the wider Francophone community. Ted Karabatsos, a former member of Dussault’s Carabins coaching sta , called him a pioneer in this regard.

Upon joining the Montreal Concordes sta in 1982, Dussault regularly represented the team in French, hosting clinics and appearing in media interviews.

“At a time when football knowledge wasn’t widely accessible in French, Jacques understood the importance of this communi-

cation,” Karabatsos said. “He wasn’t afraid to use the media to grow the sport.”

As French-language coverage expanded, Dussault emerged as a trusted voice. His extensive resume gave weight to his commentary and distinguished him within a small pool of Francophone personalities.

is credibility provided him with a platform to educate fans and elevate the sport’s pro le across Quebec. Newspapers such as La Presse regularly featured him, and his consistent use of French football terminology made the game more accessible to local audiences.

“He pushed for inclusivity and worked relentlessly to open those doors,” Karabatsos said, “and eventually, it stuck.”

A lasting legacy

Dussault’s contributions were formally recognized with his induction into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 2023 and the Quebec Sports Hall of Fame in 2024.

e RSEQ sees the new trophy as a tting tribute to his legacy.

“It is an honour to see the provincial championship now bear the name Jacques Dussault,” said Gustave Roel, RSEQ chief executive o cer, in a press release. “His dedication, leadership, and impact continue to inspire the football community, and this trophy will stand as a living symbol for generations to come.”

To kick o this new era, the RSEQ has opened a call for proposals from artists and design rms to create the new Jacques Dussault Cup. e process will be documented on social media

throughout the season, leading up to an unveiling on the eve of the championship game in November.

Regardless of its nal design, the

symbolism is clear: Quebec football now competes for a trophy that bears the name of one of its greatest architects.

When the inaugural champion is crowned this November, the rst team will etch its name alongside Jacques Dussault, a pioneer who helped pave the way for future generations.

Trent Deschamps-Coinner

As the 2026 FIFA World Cup draws ever closer, soccer fans have many reasons to be excited. With quali ers in full swing and the upcoming tournament featuring 48 teams (12 more than the previous format), the excitement seems almost palpable.

However, many soccer fans are concerned with Donald Trump’s involvement in the tournament as president of one of the three host nations, alongside Canada and Mexico.

In fact, Trump’s already made a poor rst impression with the global soccer audience. is past summer saw the FIFA Club World Cup hosted by the U.S., where Trump sparked multiple controversies.

During the championship ceremony for eventual winners Chelsea F.C., Trump was seen pocketing an extra medal meant for the players. e U.S. president also crashed the

team’s championship photo.

One might think FIFA President Gianni Infantino would try to do as much damage control as possible, but he seems to be just ne with Trump. In fact, Trump claimed that the actual Club World Cup trophy was given to him by Infantino, with the eventual champions, Chelsea, only receiving a replica.

Infantino has even been compared to Trump for using his wealth to maintain his power behind closed doors. Some even point out that the new format, with its larger size, is purely a profit-driven reform. Trump, of course, has also repeatedly drawn international ire for, among many other things, his general lack of respect when addressing other nations and their peoples. e two other host nations know this all too well. Canada dealt with taunts about becoming the 51st state for months, and Mexico was subject to many racist remarks by President Trump, alongside the whole border wall ordeal.

During the early years of his first presidency (nearly 10 years ago), Trump made references to African and Haitian immigrants coming from “shithole” countries, and said the U.S. should take more immigrants from Norway instead.

With Norway likely to qualify alongside at least nine African nations, one could wonder if there will be bad blood towards Norwegian fans from many African teams’ supporters for a comparison that Norway had no part in. is gets at the larger issues here: the U.S. has the potential to negatively impact Canada’s reputation and, to a lesser extent, Mexico’s. ere is already a general sentiment that “Americans” (mostly the U.S.) in general don’t get the sport or its culture; in fact, the supremely popular show Ted Lasso was built upon this stereotype.

Yet, instead of creating a welcoming atmosphere for soccer fans of the world, the U.S. has created an environment where the largest of the three host nations is supremely controversial and the two other host nations have increasingly souring relationships with the former.

Additionally, with multiple global military con icts still raging and the increasing prevalence of political violence in the U.S., some fans are worried about a more violent type of political expression from fans. is would not be a new or American phenomenon; soccer fans have long engaged in violence under the veil of fandom.

An example of this plays out in the Scottish Premiership, where two Glasgow clubs (Celtic F.C. and Rangers F.C.) have seen their matches against each other tainted by violent sectarianism.

It doesn’t require an overactive imagination to see how a similar environment could form during the World Cup, seeing as fans from 48 di erent nations will share stadiums this summer.

Although I have painted a fairly grim picture of how the increase in political tensions may taint the World Cup, I’d like to conclude with a potential alternative.

While international sporting competitions can provide a potential breeding ground for expressions of political violence, they can equally be an outlet for those who feel politically dispossessed, powerless or attacked to have a relatively harmless outlet for their political anxieties.

We saw this less than a year ago during the National Hockey League’s new 4 Nations Face-O , which saw Canadian fans boo “ e Star-Spangled Banner.” But in terms of actual political violence, the worst of it happened on the ice, and Canadians got their catharsis with their eventual triumph over the American team.

Defne Feyzioglu

@defne.fey

Ashark in bright sneakers walks out of the sea to meet a bat-wielding anomaly. I catch myself asking, “Why? What’s the point—am I missing the joke?”

Maybe the answer is that there isn’t a single joke to get. And maybe that’s the point. We call it “brainrot,” but what if it’s the honest genre of the algorithmic age? Fast, contextless, intentionally absurd—it isn’t cultural decay so much as scrappy, unpolished art.

Slop mirrors our broken information world through rupture and play. We keep treating it as a symptom of boredom and decline. But what if this addictive, rotting content suggests something bigger? Symptoms point to conditions, and the condition here is absurdity: too much information, too little trust and everything sped up.

A century ago, Dadaists answered a senseless world with scissors and glue. ey cut newspapers into nonsense, staged anti-art and challenged social norms. Today, the canvas is a vertical screen, and the tool is a timeline.

Dada met absurdity with scissors; slop meets it with speed. If art helps us see what’s real, the ugliest, silliest posts might be doing exactly that. e joke’s not on us—it’s for us.

Looking closely, the techniques match: juxtaposition becomes split-screen chaos, chance becomes stitches and remixes and spontaneity becomes a pass-it-on joke that belongs to everyone. A loop like “tralalero tralala” or “tung tung tung sahur” gets layered over Minecra parkour, then a sitcom cutaway, then cap-

tions that spiral into in-jokes. It isn’t a puzzle with a correct answer but a chant—until nonsense coheres for a beat and a crowd laughs together.

Of course, not all slop is good. Some is spammy, cruel or noise, and some is just AI garbage. And yes, the attention economy rewards speed over care. But craft isn’t the only measure of value. Relief counts. Permission counts— the sense that you’re allowed to make something dumb and joyful without begging for polish. And community counts—the short-lived crowds that form around a chaotic, uncanny edit and then vanish on the next swipe.

e deeper tension is who gets to call it art. Dada proved rupture could be art; brainrot stress-tests that lesson at feed speed. e frame changed from curator to algorithm, plaque to caption, but the wager is the same. If art is a way of seeing the world as it is, slop might be our most honest mirror: fast, glitchy, collective and a little feral. It doesn’t pretend to x the absurdity; it plays into it.

So, let’s name it without apologizing. Slop is the feed’s col-

lage—roughcut and participatory. Keep your symphonies, novels and your careful lms. But save space for the nine-second joke that isn’t a joke. In an age of too much and too fast, this is how we breathe together—one ridiculous stitch at a time.

Mani Asadieraghi

@mani.asadieraghi

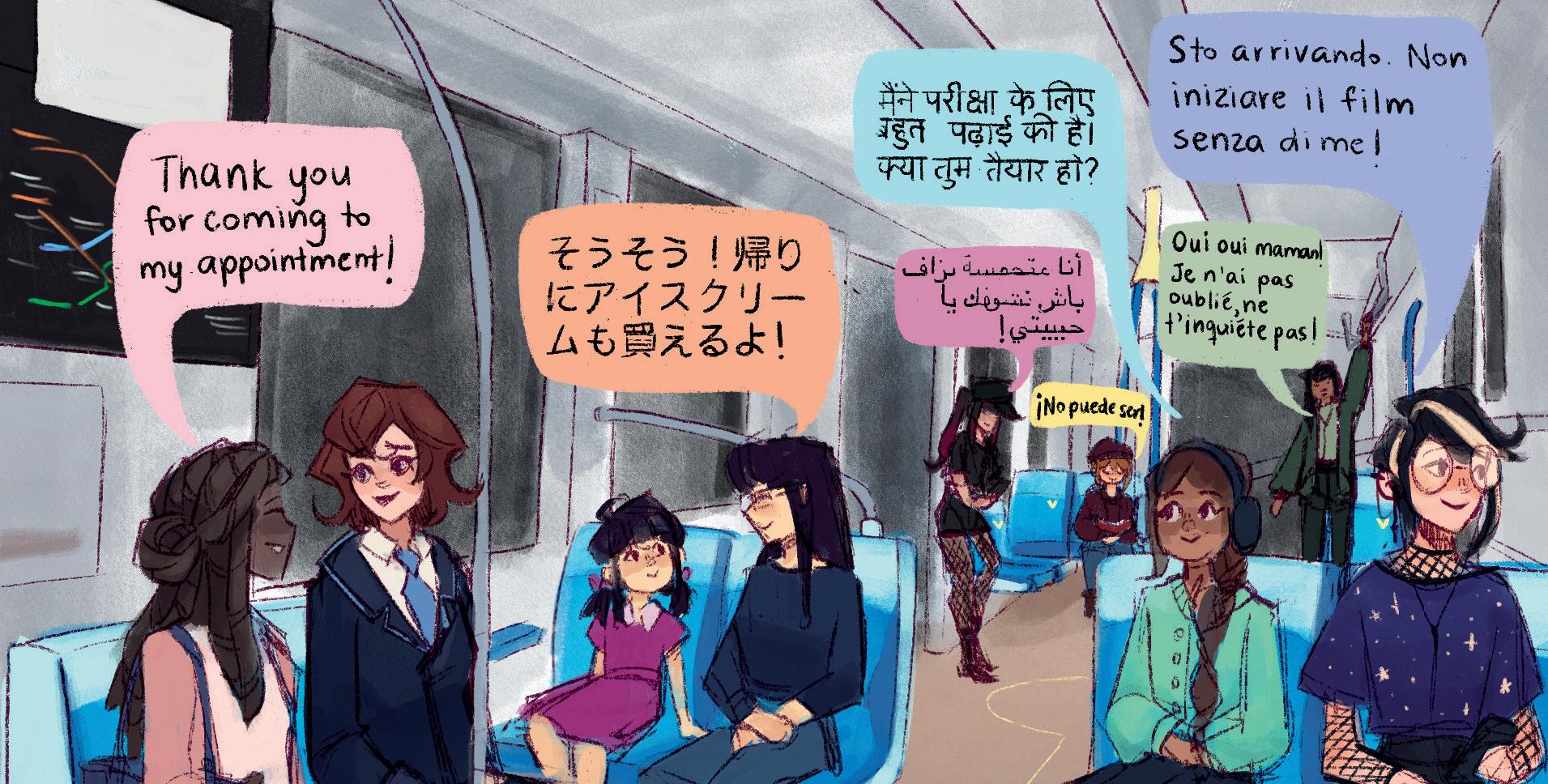

Onthe Montreal Metro, French merges with Arabic, English ows into Persian, and Spanish dri s into Mandarin. e city pulses with diversity. Yet Quebec politics give way to a new refrain: diversity is only welcome if it conforms.

Montreal’s multiculturalism isn’t decorative—it’s foundational. In the 2021 Statistics Canada population census, nearly 40 per cent of residents identi ed as visible minorities. Many of those surveyed also spoke a mother tongue other than French. Yet laws such as Bill 96 and Bill 21 don’t nurture that tapestry.

Bill 96 forces businesses and public services to operate in French. It allows the government to override certain protections in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms through the notwithstanding clause, imposing what its opponents dread is a “Charter-free zone” across wide parts of civil life.

Meanwhile, Bill 21 bans public employees, like teachers or judges, from wearing visible religious symbols such as hijabs or turbans, sending a message that religious minorities are not fully welcome in public roles. Together, these laws impose strict controls over language and personal expression.

Anyone who calls Montreal home can feel this contradiction. Montreal thrives on openness, yet Quebec’s legal framework quietly insists: “You belong here, but only on our terms.”

Stakes climb as politicians grow bolder. e Quebec government recently oated a ban on public prayer, alarming civil rights groups who believe it disproportionately targets Muslim communities and undermines democratic freedoms.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court of Canada has agreed to hear a landmark challenge to Bill 21, a ruling that could rede ne the balance between rights and provincial powers. And abroad, the U.S. has now labelled Bill 96 a non-tari trade barrier, accusing it of imposing costly burdens on transborder commerce.

Quebec's legislation no longer involves asserting provincial authority against the federal government or contrasting itself with English Canada; it's now a ecting the province's reputation nationally and internationally.

We also need to acknowledge the fear motivating these stat-

utes—here, the French language faces extinction. Preservation is necessary. But re exive repression isn’t strength; it’s eradication.

If the province truly wants French to flourish, it should treat Francisation Québec, the government’s French-language program for newcomers, as an invitation, not a hurdle. All too often, these programs sit underfunded and rigid, with limited availability, long waitlists and class structures that don’t accommodate people balancing work, study or family responsibilities. Instead of supporting integration, they often leave newcomers frustrated and disconnected.

Envision an education system with exible schedules, properly funded instruction and cultural programming that reframes francization as the key to inclusion rather than a symbol of exclusion. A strong province invests in the ability of its people to adopt its language—it doesn’t sanction them for not doing so quickly enough.

Montreal’s universities already show coexistence between rights and language. Concordia University actively promotes bilin-

gualism through French courses, exchanges and community partnerships. Rather than presenting such institutions as threats, the government should view them as bridges connecting the world's talent with Quebec society, while fortifying the French language.

And if Quebec hopes to demonstrate con dence in its culture, it must look beyond bans. Sti ing religious symbols or public prayer signals insecurity, not strength. Secularism constitutes the neutrality of the state—not the erasure of its citizens.

e paradox remains self-evident: for the sake of uniformity, not inclusion, Quebec risks its future. Montreal’s cultural heartbeat and global face prove that Quebec culture can thrive alongside diversity. Multiculturalism and our francophone culture can coexist, but fear directly opposes con dence.

Montreal has already chosen con dence over fear; now Quebec must decide whether it will do the same.

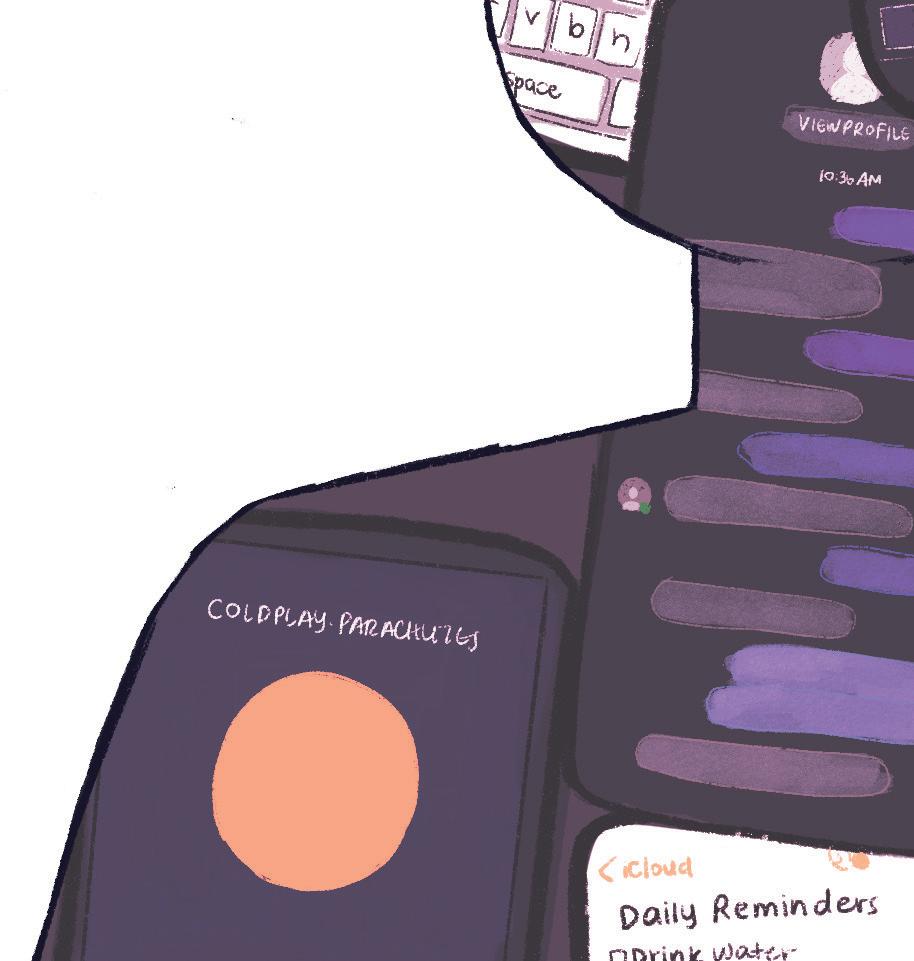

Aperson's digital closet—their playlists, camera rolls, Notes app dumps and endless screenshots—reveals much more about their psyche than the clothes hanging in their physical wardrobe ever could.

Our phones have become a curated archive: less a storage device, more an intimate extension of our desires, fears, memories and obsessions. If once a diary chronicled a soul, today it’s the mosaic of digital fragments across our screens that tells the deeper story.

Unlike traditional closets, which embody style and status, the digital closet holds unguarded moments: voice memos recorded at midnight, friendships captured in old WhatsApp threads, screenshots of texts never sent, and playlists built for moods we never admit aloud. ese are not curated for public display; rather, they accumulate quietly, presenting a raw, honest catalogue of a life in progress.

Scrolling through someone’s media library or Notes app can reveal their inner landscapes, unspoken anxieties and secret dreams, giving digital intimacy a vulnerability that physical possessions rarely achieve.

Each saved image or cryptic note re ects choices: what is worth remembering, fearing or desiring. Obsessive screenshotting and collecting digital ephemera are modern acts of meaning-making, replacing the box of old letters under the bed with a camera roll chronicling both joy and heartbreak.

Unlike physical clutter, digital hoarding o en goes un-

checked, endlessly archiving insecurities and aspirations. e digital closet thus acts as a living diary, exposing not just taste, but the evolving contours of the self.

But there is a profound risk tucked into our digital closets. What feels intensely private—the melancholy playlist, the screenshot of an old message, the note titled “For When I Leave”—is more exposed than most people realize. Every smartphone is a portal for powerful algorithms and tech companies to map our desires and vulnerabilities in granular detail, sometimes without consent.

Identity the , commercial pro ling and accidental exposures are not just distant threats: data breaches or poorly secured apps can reveal more than we ever intended, and for marginalized communities, the digital closet can become a site of involuntary outing or surveillance—or worse.

Mindfulness is essential. It’s easy to let digital clutter accumulate, but much harder to reckon with the consequences when boundaries are breached. Regularly reviewing what is kept, scrubbing sensitive notes or screenshots, and limiting app permissions are acts of self-protection, not paranoia.

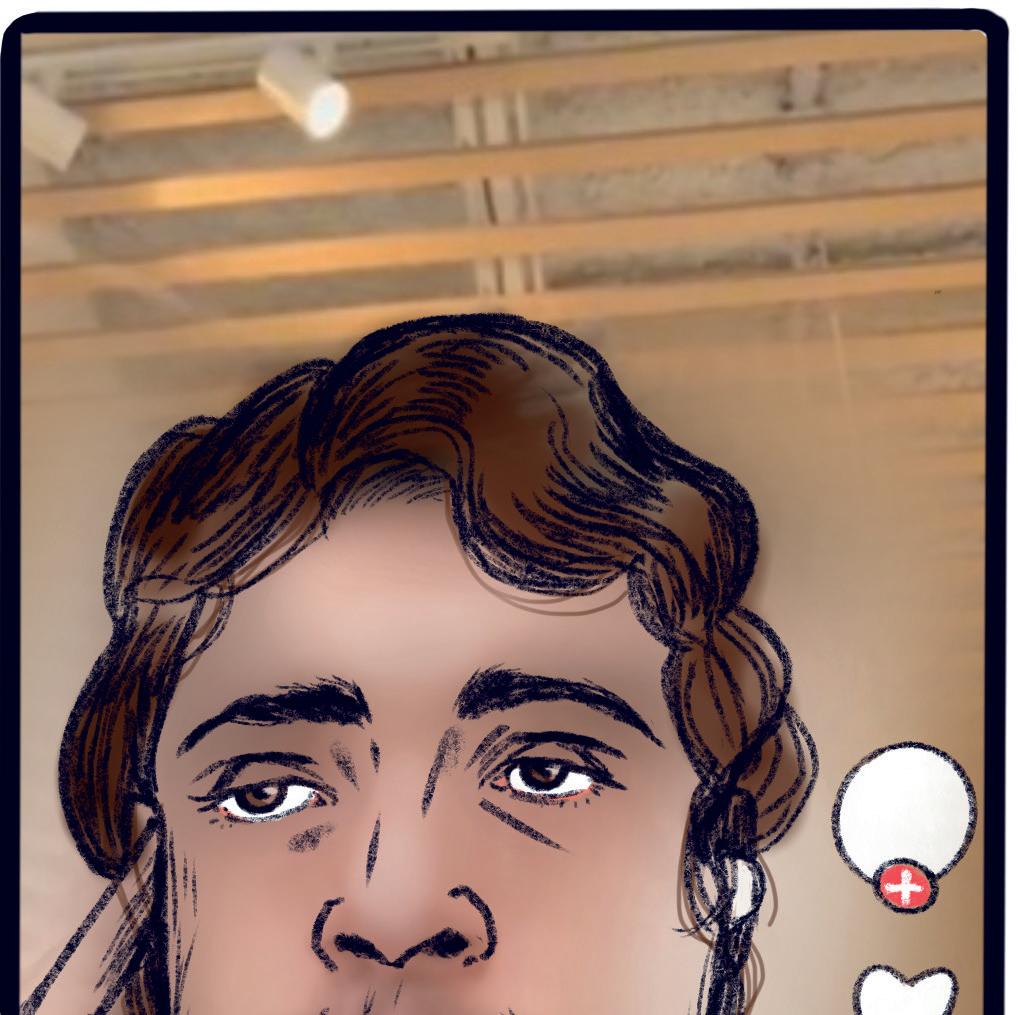

If you scroll through Instagram or TikTok, you might catch a politician lip-syncing to an ironic audio clip or hopping on the latest trends.

is is less likely satire than strategy. In an era where attention spans are measured in seconds, the podium has been replaced by the algorithm.

Social media has become the main stage for public discourse. TV ads, town halls and even billboards can’t compete with a viral 15-second clip. Everyone—plumbers, coaches, businesspeople— has become an in uencer, and politicians have followed. Politics has entered the content economy, where the golden rules are simple: be relatable, be quick, be everywhere.

But here’s the problem: politics isn’t supposed to be content. When leaders chase likes instead of trust, they trade substance for spectacle. A politician who governs by trend is no better than an in uencer selling skincare—except the stakes are far higher.

U.S. President Donald Trump is the perfect example of this type of political in uencer. His constant presence on social media, direct-to-camera videos and use of catchy slogans showed how a political gure could dominate the digital space like a content creator.

Yet, his approach also revealed some of the more troubling dimensions of this strategy. Tweets riddled with misinformation, personal attacks against opponents, and in ammatory statements not only entertained his base but also undermined democratic norms and fact-based debate. Moments such as his repeated false claims about election fraud or his use of Twitter to escalate international tensions show how his in uencer-style politics blur the line between political messaging and sensationalist content creation.

In Quebec, Ruba Ghazal, a member of the National Assembly for Québec solidaire, also embraces social media to connect with the public. However, she does this with a seemingly very di erent intention.

On Instagram, Ghazal highlights her policy priorities, com-

municates directly with constituents, and occasionally critiques political opponents, such as Premier François Legault. She o en uses trending sounds and popular songs to build an informal, approachable tone that mirrors in uencer culture.

While the style is similar to Trump’s—direct and highly visible—the purpose is fundamentally different: Ghazal uses her platform for advocacy and engagement rather than sensationalism.

This contrast shows that while certain political leaders have learned to leverage concise video formats to convey substantive messages rather than merely divert attention, others have used the same tools in ways that entertain or inflame, rather than inform.

With phone cameras and editing apps, responsible leaders permit voters to glimpse the quotidian motions of governance. is unscripted transparency builds a sense of personal accessibility and genuine involvement. e approach transcends staged performances by repurposing a familiar communication medium, thereby meeting audiences where they consume news and opinion every day.

Yet we must be careful not to mistake this content for the whole truth. When the lines between media and reality blur, it becomes easy to forget what is carefully cra ed content and what is substantive fact—and leaning on these glimpses alone risks oversimplifying the complex work of governance.

e issue isn’t that politicians are online. e problem arises when the goal becomes merely to gain views.

Consider: Is every piece of this digital archive worth the price of privacy? Or is it time to curate not just for memory’s sake, but for security too?

Our digital closets are no longer silent witnesses; they are outspoken re ections, revealing more than we ever planned. e real dilemma isn't what we’re curating, but how much of ourselves we’re giving away with every swipe, save and screenshot. It's time to pause, re ect and only let the most intentional pieces live on in this archive of self.

When politicians post silly skits or chase trends just to stay visible, it cheapens the conversation. Politics begins to feel more like a popularity contest than a civic responsibility, and important debates risk being overshadowed by spectacle. Beyond the potential to undermine democratic norms, this approach erodes public trust, discourages informed engagement, and makes political discourse increasingly shallow and performative.

In the end, when politics becomes content, democracy itself becomes the

Michael Lecchino

Astrangerstopped mid-walk in the Vanier Library at Concordia University and whispered, “Wait—this is by a Concordia grad?”

It was.

Since 2024, our Library Services Fund Committee (LSFC) and Art Volt have installed a set of works by recent ne arts graduates at the Vanier and Webster libraries, right where students spend their days—between chargers, course reserves and group-study areas.

e moment landed exactly as we hoped it would. It didn’t just decorate the wall; it reframed the room and reminded someone hustling through midterms that a peer from this campus had made something moving, public and lasting.

For years, we’ve highlighted “student experience” as if it were a policy line item. is experiment proves that the experience is physical. It’s where your eyes fall while you’re waiting on a printer queue, what interrupts your stride on the way to an exam, what turns a hallway into a conversation.

We identi ed a few high-tra c spots in each library, worked with Art Volt to co-curate pieces from recent grads, and hosted

You don’t need a degree in art history to feel something shi . You just need to pass by o en enough for a piece to catch you on a day you didn’t expect it to. e surprise becomes a campus habit: lingering, reading the information card, recognizing a name, telling a friend, seeing the library di erently. at’s how public culture should work at a university. No velvet rope, no eld trip required, just daily encounters with ideas.

is isn’t just a feeling. e World Health Organization’s synthesis of more than 3,000 studies clearly outlines that the arts play a “major role” in preventing ill-health, promoting well-being and supporting treatment across the lifespan.

In health settings, patients don’t just notice artwork; they report better mood, lower stress and a stronger overall impression of care when surrounded by art. If that’s true in hospitals, imagine the stakes inside libraries during midterms. We already invest in extended hours, device-lending, course reserves and wellness corners; curating student-made art into the same spaces is an evidence-based way to support students’ mental state where it matters most.

a vernissage where the artists shared process, meaning and context. We committed to rotating the selections regularly so new voices keep surfacing. And then we let the space do its work. e results are visible and human. At the Vanier Library, an acrylic painting plants a Black-Indigenous woman in the landscape, forcing erased histories back into view; downtown, a bustling metro platform scene folds diaspora and city together.

In its last issue, e Link published an editorial entitled “You only know half the story.” Ironically, this was also exactly what this piece was doing by cherry-picking and arranging events to t e Link’s narrative.

The Link focuses on “advocacy journalism” meaning it supports specific points of view on several issues. This is clearly stated in its mandate –but who looks at a mandate before reading an article? is advocacy might not always be obvious. e Link uses elements associated with journalism, mimicking the style you might see in a newspaper and by extension giving readers the impression that the same journalistic standards are applied. Yet, on closer inspection, one might notice some di erences.

And if health doesn’t move you, economics might. Canada’s culture sector generated $63.2 billion in 2023—2.3 per cent of the national GDP—with notable growth in visual and applied arts and live performance. That’s not ornamental; it’s infrastructure.

e best part? e simplicity. We didn’t build galleries; we used what we already had.

Pick the walls with natural dwelltime: elevator banks, tunnel junctions, study nooks. Partner with Art Volt to feature recent grads and include short process texts so non- nearts students can walk in with no background and still feel invited. Rotate the works on an annual basis so each graduating class leaves a trace. Document the locations and repeat.

Some will say, “We already have galleries for that.”

Galleries are wonderful—and not enough. They ask you to make time. Hallway installations give time back by sneaking reflection into the commute between a lab and a lecture. Galleries select a few; rotating walls broaden exposure to many.

When an engineering student recognizes a classmate’s name on a label or a business student stops to read an artist’s note about materials and memory, the campus starts to feel more like a single community than a collection of silos.

So here’s the ask, plain and doable: If you’re a department

chair, pledge one wall and a two-hour window for installation. If you’re a dean, set aside a tiny yearly budget for hanging hardware, labels and refreshes. If you’re a faculty association, help recruit artists and collect feedback. If you’re Facilities Management, publish a safe, reversible, simple hanging guide so any unit can copy-paste. No committees for the sake of committees, no endless planning sessions. Just a few permissions, a short checklist and a schedule.

I’ve spent three years on the LSFC, advocating for art accessibility and helping make this collaboration with Art Volt happen. I’ve seen the patient, deliberate work of coalition-building pay o in a very Concordia way: modest resources, clear intent, shared stewardship, big human return.

If we believe this university is a city of ideas, we should let our students speak through every wall we have. Start with the pieces in the Vanier and Webster libraries. Read the placards. Feel the room tip a little. en pick the next wall.

e Link routinely uses anonymous sources, something that in journalism is only done very sparingly, in exceptional cases. It likes to quote “organizations” making “statements” – words that give weight but that o en refer to a social media account with no mention of if it represents one, ten or 1,000 people.

e Link o en foregoes context entirely. In the editorial, it writes that “over 11,000 Concordia students went on strike” last year. is is technically true and you’d be forgiven for thinking that thousands gathered on campus. But 11,000 is the number of students represented by the student associations who voted for the strike. Only by clicking on the hyperlink in that paragraph will you nd out that “around 100 people” started o the demonstration and that “over two dozen students were picketing classes.”

e Link also regularly omits parts of answers provided to

them, even when it directly answers an issue raised in the article. Writing about the university’s investments, the editorial names two companies in the portfolio. It however does not mention this part of an answer given to them back in April: “ e companies you mention are with portfolio managers from which we plan to withdraw as part of the nal phase of our transition to 100 per cent sustainable investments, which we announced more than ve years ago and are completing this year.”

e Link is of course a student publication, a learning space where mistakes will be made. But by proclaiming itself an advocacy publication, it can’t in the same breath claim to provide the full story. In the words of the editorial itself: “we invite you to remain critical and resist taking everything at face value.”

Concordia University spokesperson, Vannina Maestracci

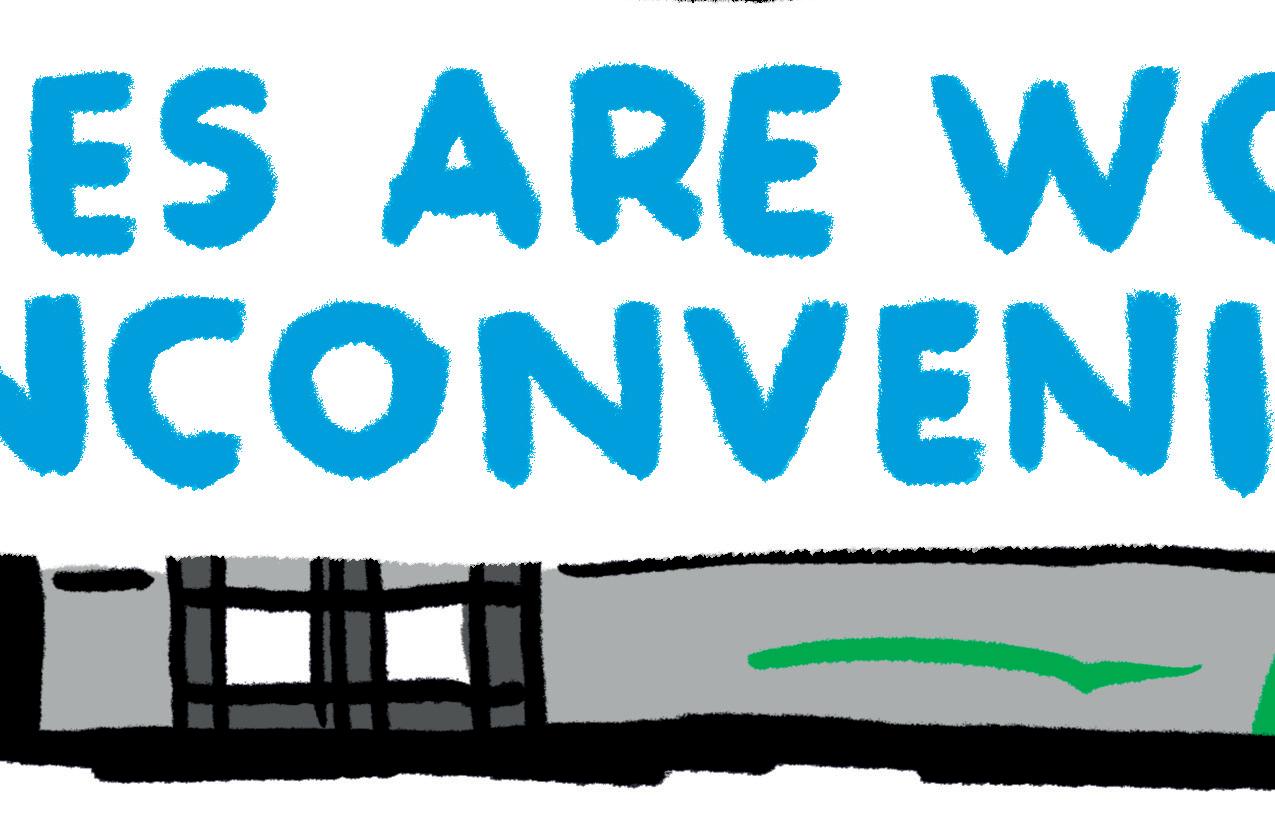

As the upcoming Société de transport de Montréal (STM) maintenance workers’ strike looms at the end of this month, many Montreal residents—including Concordia University students—may feel discouraged by the limited transportation hours.

However, e Link believes it’s crucial not only to support, but to upli workers during strike action.