Seven student associations vote in favour of striking for divestment, more to

vote this week QUICKIES

Hannah Scott-Talib

Seven Concordia University student associations representing over 6,800 students have voted to go on strike for Palestine from Oct. 6 to Oct.7, with several more set to vote to strike in the coming days.

e strike motion, brought forward by Students for Palestine’s Honour and Resistance (SPHR) Concordia, seeks to demand that the university cut all ties with companies complicit in the ongoing genocide in Palestine.

More precisely, it calls on the university to end its employment partnership with Lockheed Martin and divest from Palantir, Boeing, Spirit AeroSystems, Triumph Group and Booz Allen Hamilton.

According to an SPHR spokesperson who was granted anonymity for safety reasons, the strikes will take place from Oct. 6 to Oct.7 due to the signi cance of Oct. 7, 2023, as the beginning of Israel’s escalated retaliation attacks and subsequent genocide in Gaza.

“We ended last academic year with a disclosure win, and over the summer and the beginning of this year, UN reports came out that show very clearly what the role of the universities is in this deep violation of human rights on their own campuses,” the SPHR spokesperson said. “Concordia is de nitely not an exception to that fact.”

ey said that a protest will also take place during the strike dates to add more pressure on the university’s administration, and that SPHR hopes to see students mobilize and engage with the signi cance of the strikes by supporting picket lines and attending the protest instead of classes.

“It’s been two years of genocide in Gaza, and we can’t let this go further,” the spokesperson said. “ e student body in all its levels must act—everyone has a role to play in divestment.”

In November of last year, over 11,000 Concordia students went on strike for divestment. Eleven student associations within the Arts and Science Federation of Associations (ASFA), as well as all students in the Fine Arts Student Alliance (FASA), joined the strike.

So far this year, FASA, the Political Science Student Association, the Women’s and Sexuality Studies Student Association, the Geography Undergraduate Student Society, the Teaching English as a Second Language Student Association, the Linguistics Student Association and the Concordia Association for Students in English (CASE) have voted for the

strike motion at their respective general assemblies (GAs). e Concordia Urban Planning Association is the sole student association to have voted against the motion thus far.

“It’s our job to give students the option to decide on these things as they wish, to inform them about what’s going on with the political situation at the university,” said Jonah Doniewski, FASA student life coordinator. “[At the GA], people were very eager to talk about it and to vote on the matter.”

Doniewski added that FASA will hold a meeting to further discuss mobilization tactics and how students wish to strike.

ey said that it’s important for students to become informed about di erent ways to strike and how to stay safe.

“Recently, with strikes for Palestine, they’ve been met with a lot of combative behaviour, high levels of surveillance and general pushback from the university,” Doniewski said. “It’s important that students know that, so that they know what they’re getting into.”

On its end, CASE voted to amend the motion to “enforce the strike through a hard picket, blocking classes ensuring their cancellation” at its GA on Sept. 29.

“Change starts small, so if we’re able to push Concordia to divest and to boycott with us then that’s an important and meaningful step towards ending the genocide,” said CASE VP of Publications Tobias Walma. “In the upcoming week, there will be opportunities for students to get involved and join picketing workshops.”

According to Doniewski, there is strength in numbers when it comes to striking.

“ ose things only become really dangerous when there are not a lot of students at the protest,” they said. “So having a lot of people there, present, protecting each other, is a really huge factor.”

Doniewski added that FASA will not publicly announce the date and time of the strike mobilization meeting, but that students interested in attending may reach out to the association via Instagram or email.

From Sept. 30 to Oct. 3, ve more student associations representing community and public a airs, communications studies, history, psychology, and sociology and anthropology will present and vote on the strike motion.

With les from India Das-Brown

Statistics Canada says Quebec had the highest in ation rate in the country in August, climbing to 2.7 per cent. Groceries and housing costs contributed the heaviest, with food prices up more than 27 per cent since 2020. e national average rose to 1.9 per cent, while Prince Edward Island had the lowest in ation rate at 1.1 per cent.

Canada Post workers launch nationwide strike e Canadian Union of Postal Workers has called 55,000 employees to the picket lines a er the federal government ordered major reforms, including ending home delivery and closing rural post o ces. Canada Post says no new mail or parcels will be accepted during the strike, though government bene t cheques and live animals will continue to be delivered. e postal service currently loses about $10 million per day despite a $1 billion injection by the federal government earlier this year.

Dubai chocolate linked to Salmonella Quebec’s Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food has advised the public not to consume any Dubai chocolate from the Montreal store Sour Bites sold between April 7 and Sept. 5 due to risks of Salmonella. is is in line with a nationwide Salmonella outbreak. e Public Health Agency of Canada has con rmed 105 cases of Salmonella linked to pistachio and pistachio products in the country, with 66 con rmed cases in Quebec.

Microso blocks Israel’s use of its technology in secret spy project

Following an investigation by e Guardian, Microso cut o the Israeli military’s access to its AI and data services used for mass surveillance of Palestinians, citing terms of service violations. Unit 8200, Israel’s spy agency, used the platform’s near-limitless storage and computing capabilities to collect, play back and analyze Palestinian civilian phone calls made each day in Gaza and the West Bank. e blockage has not changed Microso ’s wider commercial relationship with the Israel Defense Forces.

Sidra Mughal

The Breakfast Club of Canada estimates that one in three children across the country is at risk of going to school on an empty stomach. In 2025, Statistics Canada found that nearly 2.5 million children live in food-insecure households, displaying a 20 per cent increase in just a year.

In Montreal, many teachers and educators agree that the problem features

prominently and visibly every day. Despite existing meal programs, too many

showed up in the classroom as crying, anger or withdrawal.

“A small snack made a huge di erence,” she added.

social pressure,” Olivares-Wueshner said. “Meal programs directly a ect learning.”

Meal programs help, but gaps remain While Montreal schools tives, their reach even. Emma stated that her school,

as subsidized lunches for families below a certain income level.

Nationwide, the Breakfast Club of Canada has seen the demand for such programs surge by 30 per cent in recent years. Today, the organization supports over 880,000 children in more than 4,900 school nutrition programs. Yet demand

“More o en than not, when I ask if a student has eaten, the answer is no,” D'Alessandro explained.

On average, D'Alessandro said she encounters one or two students a day who haven’t had breakfast or lunch, though she

Meanwhile, Laura Olivares-Wueshner, a specialized educator who visits multiple schools across Montreal, said she has seen the e ects of hunger vary by neighbourhood.

“In wealthier areas, it wasn’t common to see children without food. But in places like LaSalle and Lachine, I notice it much more frequently. Many parents struggle to a ord snacks and meals,” Olivares-Wueshner said, adding that hunger o en

dro said.

students crowd into the cafeteria during lunch and recess to get something to eat.

Olivares-Wueshner said she has also seen how programs can build inclusion. In her classroom, she sometimes hosted monthly breakfasts out of her own pocket so all students had access to healthy food.

“Providing lunches and snacks helps reduce bullying and

Kara Brulotte

Researchers at Concordia University have created a new system to quickly track how pathogens travel in indoor spaces.

e model tracks a contagious person as they move through a space and models how the pathogens disperse. is can function in tandem with air ventilation systems to keep high-tra c areas, such as rooms in a hospital, free of infection.

“We're trying to emphasize the element of time. With the existence of smart systems around sensors and cameras, we would be able to respond to the dispersion of pathogens in a more timely manner,” said Concordia professor and research co-author Fuzhan Nasiri.

According to research author and PhD student Zeinab Deldoost, the model improves on two major limitations of previous research: long computational time and needing to know the exact path of the person before they walk.

Deldoost said they accomplish this by reducing the human

being tracked to a box that represents them, which simpli es calculations and does not signi cantly a ect accuracy.

In turn, this short calculation time lets the model integrate with a real-time movement detection algorithm, allowing it to track people and quickly calculate the pathogen spread. is process, Nasiri explained, used to take hours, while now pathogen spread can be mapped within seconds of it occuring.

“ is makes the model particularly suitable for dynamic real-world applications, such as hospitals and other shared spaces, where paths of the infected person are unpredictable,” Deldoost said. “Rapid decision-making is essential for these places.”

According to the researchers, this method could be deployed in future disease outbreaks to ensure minimal spread of pathogens. ey added that, with this model, cameras, and a smart ventilation system, people could know almost immediately if and when they had come into contact with someone contagious, and avoid it before it happens.

She explained that all donations must pass

the bene ts of school meals and said that well-fed students and con dent. dents come back from lunch

Even with these existing meal programs, many Montreal with more

their studies,” Emma said. “No child should ever be hungry during school hours. Hopefully, in the future, free lunches can be provided to all students across the province.”

“In the hospital, there are a lot of sick people coming in and moving out,” said Concordia professor and research co-author Fariborz Haghighat. “And in case one of them is contaminated and goes to di erent places, we have the ability to simultaneously follow this person and nd out with whom he or she's been in contact with.”

Haghighat added that this research, coming in the wake of the pandemic, could revolutionize the way that countries deal with future disease outbreaks, allowing increasingly complex technology to keep buildings free of disease. He said the faster they can track the pathogens, the better they can control the spread of diseases.

“With the emergence of pandemics such as in uenza, SARS and COVID-19, pathogens have become key factors contributing to the contamination of indoor spaces,” Deldoost said. “Understanding the behaviour of pathogen dispersion in indoor environments is crucial.”

The Claudine and Stephen Bronfman Fellowship in Contemporary Art is under fire for its ties with the IDF

Bellefeuille

The anonymous MFAs Against Genocide movement announced on Sept. 24 a call to boycott the Claudine and Stephen Bronfman Fellowship in Contemporary Art at Concordia University. ree days a er the campaign's launch, over 100 people signed the pledge to boycott the award.

“We call for a boycott of the Fellowship because we refuse to have our art used to provide cover for the Israeli genocide and occupation of Palestine,” said a spokesperson for MFAs Against Genocide in an email to e Link, who was granted anonymity for safety reasons.

“We know where this money comes from, so we cannot a ord to accept it,” the spokesperson added.

e fellowship is awarded to two recently graduated or near-graduation students from Concordia and Université du Québec à Montréal’s faculties of arts every year. It derives its funding from cyber surveillance rms working with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), according to the MFAs Against Genocide collective’s social media.

“We know from speaking with past winners that there is a moral hangover that comes with this funding, and it lasts so much longer than the two years of funding,” said the MFAs Against Genocide spokesperson.

e Claudine and Stephen Bronfman Fellowship in Con-

temporary Art was established in 2010, and the funds for this fellowship, valued at more than $88,000, are distributed to the winners over two years. e funds are raised and managed by Montreal-based private investment rm Claridge Inc., which opened its parallel rm, Claridge Israel, in Tel Aviv in 2015.

MFAs Against Genocide states on their website that in 2018, Claridge Israel “invested $30 million USD in Cyberbit Ltd., a cyber security, warfare, and espionage company with the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) as one of their key clients.” e investment is publicized on Claridge Inc.’s own website.

Cyberbit Ltd. was founded as a subsidiary of Elbit Systems Ltd. in 2015 by Adi Dar, who, according to Forbes, “spent nearly 15 years as a decorated o cer in the Israeli Army and a key member of e 8200, an elite national intelligence branch.”

e Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto discovered in its 2017 investigation of Cyberbit Ltd. that the company was involved in developing, marketing and selling spyware to multiple governments for the purpose of surveilling political dissidents.

Cyberbit Ltd. claims on its website that its products are “proven in the eld,” a claim also made by its parent company.

In 2023, Al Jazeera reported that Elbit Systems Ltd. “provides up to 85 percent of the land-based equipment procured by the Israeli military and about 85 percent of its drones, ac-

cording to Database of Israeli Military and Security Export.” e MFAs Against Genocide spokesperson said they hope that the more student artists know where their awards funding is coming from, the more it motivates them to sign petitions like theirs.

“ is is not only a boycott campaign, but an opportunity for us to strengthen and expand our community of artists, educators, and cultural workers who put action behind their beliefs and refuse to provide cover for the artwashing of genocide,” they said.

ey added that MFAs Against Genocide plans to host multiple events within the upcoming months as part of its campaign to force Concordia to give alternative scholarships to students.

In an email statement to e Link, Concordia spokesperson Julie Fortier wrote that the university is not looking to reduce fellowship opportunities for artists at the moment.

“Applying for and accepting a fellowship is an individual choice, made by each student. Many artists struggle to fund their art and fellowships such as these can be pivotal in their careers,” Fortier said. “We also hope that those who have bene ted from the fellowship in past years will not be the subject of attacks for making that choice.”

Claridge Inc. declined to comment for this article.

Maria Cholakova

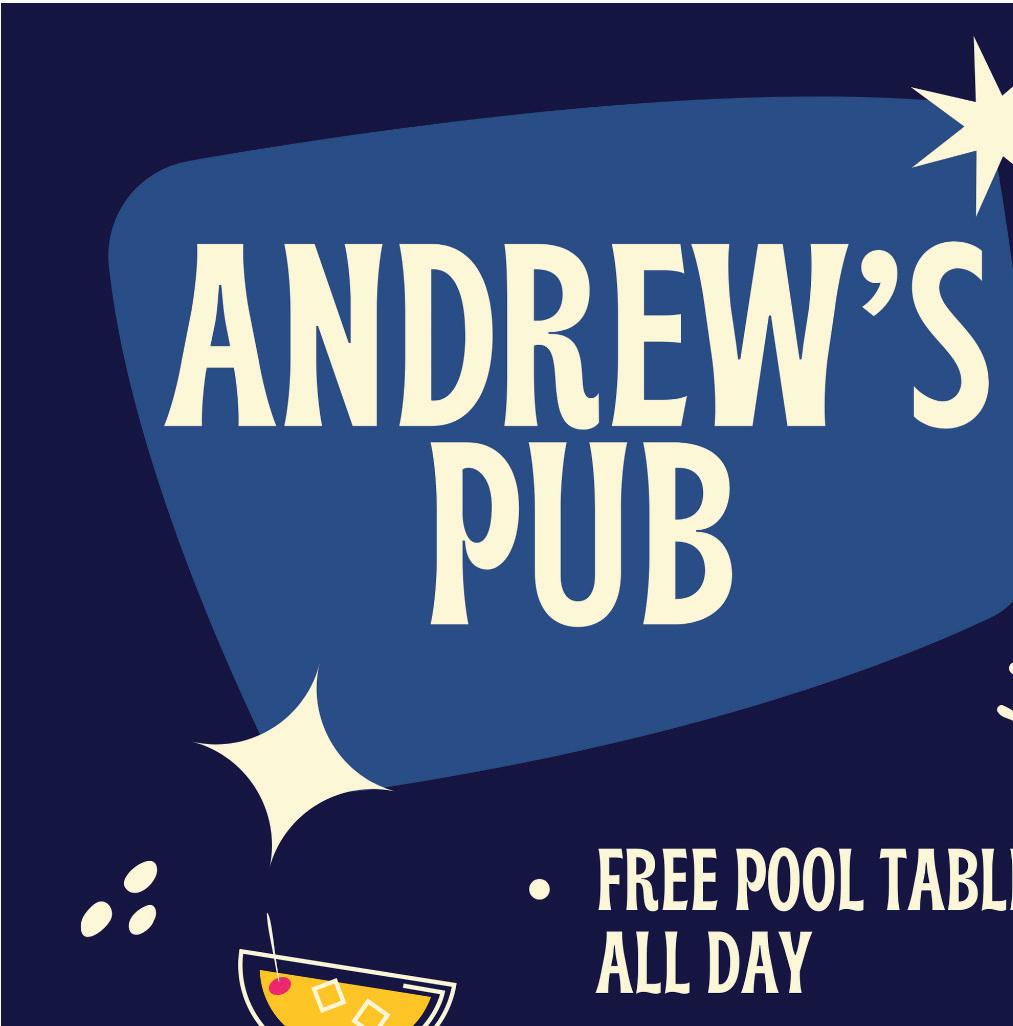

During a weekly irsty ursdays event on Sept. 18 hosted by Reggies, Concordia University’s campus bar, a man broke the laptop of the bar’s DJ, Alex Dalipaj.

According to the SPVM, the 23-year-old man was detained and charged with mischief for breaking an item valued at under $5,000, and was released later that evening.

According to Dalipaj, the man falsely claimed he owned the bar during the altercation.

“He wasn’t respecting my personal space, so I asked him to step down and enjoy his night,” Dalipaj said. “He replied by threatening my job and that of the bouncer.”

Soon a er the man’s interaction with Dalipaj and Reggies security, he was removed from the premises. He later attempted to return.

“I’m doing my thing, and then I look up and somehow he’s crashing into my setup and knocked my laptop down,” Dalipaj said.

Dalipaj’s laptop display was shattered and stopped functioning properly, putting an early end to his set. According to Dalipaj, the man agreed to pay him back for the $2,000 in damages.

“ e damage is currently preventing me from completing school, but I’ll rent a computer from the library if it takes any longer to repair,” the DJ said.

Nonetheless, Dalipaj returned to DJ at Reggies the week a er the irsty ursdays incident.

According to Alex Rona, the bar’s operations manager, the campus bar has faced property damage before.

“ is isn’t the rst time, but it was a pretty unique one,” he said.

Rona said that despite the night’s events, Reggies sta attempted to keep the party going, but without a DJ, he said, the night was not the same.

He also explained that the bar has been attracting more customers during its irsty ursdays events, and the bar managers are evaluating how to ensure safer parties.

“We’ve increased security measures. All our irsty ursdays so far this year have been at maximum capacity for large portions of the night,” Rona said. “With more people attending Reggie’s than ever comes the responsibility to ensure that our customers, sta , DJs and venue are all protected and accommodated properly.”

Content warning: This article contains descriptions of sexual harassment and inappropriate sexual behaviour.

Melissa Pappas has clocked into work at various nightclubs and bars in Montreal for nearly two decades. One Friday night, she’s dressed in all black as she shakes cocktails and pours shots until 4 a.m. for the drunken clients coming up to the bar. She’s friendly as she takes their order. She smiles and makes jokes in hopes that her cheery nature will bring her a hefty tip.

The “largely male clientele,” as she describes it, doesn't always make it easy for her.

“On one occasion, I had a regular male client call me a whore,” Pappas says. Stunned by the comment, she says she asked the male bar owner to have the customer kicked out. The owner refused.

Experiences like Pappas’ are common among women in Montreal’s nightlife industry since they constantly interact with customers, according to a 2020 Statistics Canada report.

The report found that women working in service and sales industries were most likely to experience inappropriate sexualized behaviours at work compared to women in most other industries. Women working rotating shifts, evening shifts or irregular schedules—typical in bars, nightclubs and strip clubs—reported higher rates of such experiences.

Male clients often act in threatening ways towards women because of the power difference between customer and employee, say Dr. Jill Poulston and master’s student Beth Waudby in a 2017 study from the International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research.

Poulston and Waudby found that respondents of their study felt that restaurants and bars are places where sexual behaviours are expected. The researchers found that sexualization of labour can lead to customers behaving sexually and generating harassment. Managers prioritize customer loyalty and expect women to expect sexual behaviours from customers, they say.

The 2020 Statistics Canada report “Workers’ experiences of inappropriate sexualized behaviours, sexual assault and gender-based discrimination in the Canadian provinces,” found that the public-facing nature of service occupations encourages harassment or demeaning behaviour from clients.

“There was one time when this guy was kind of stalking me, showing up at the bar all the time,” says Lola Bakel, an employee at Negroni Room and Buvette Pastek, “and after, showing up where I live.”

The 2020 Statistics Canada study found that, of the female service and sales workers who had experienced inappropriate sexualized behaviour in the workplace, 53 per cent of them had at least one incident perpetrated by a customer.

Waudby and Poulston also found that managers sometimes require staff to wear clothing that accentuates their sex appeal to increase customer loyalty and spending.

“My friend was working at [a club on St. Laurent St.] and she would wear, you know, like dress pants and a nice top, something like what the men were wearing,” Bakel says. “And they put up a notice that women can only wear skirts or dresses, and they had to be a certain length.”

Waudby and Poulston report that managers’ desire for customer satisfaction can condone difficult behaviours from customers and restrict female employees’ ability to reject unwanted sexual behaviour. This rings true specifically in environments offering alcohol and anonymity, like bars, they say.

The researchers also found that female employees sometimes report feeling the need to act in a sexual manner at work to maintain customer satisfaction.

“I can honestly say that I have actively flirted, worn different clothing and behaved less like myself in the hopes of making a greater dollar—especially when I was younger,” Pappas says.

In a 2011 testimony entitled “Sexual Exploitation Industry Makes Both Victims and Victimizers,” Dr. Mary Anne Layden says that the sex industry normalizes the belief that women’s bodies are sex objects meant for male entertainment, which gives male customers a false sense of permission to cross sexual boundaries with female strippers. Layden says most strippers have been sexually harassed and that the activity of stripping produces violence.

demic researchers Harley J. Paulsen, and Dr. Ericka Kimball, found that 84 per cent of strippers reported “unwanted groping, rape, forced or coerced unwanted sexual acts.” The study also found that 63 per cent experienced verbal abuse, 59 per cent experienced harassment and 53 per cent experienced physical assault.

“In this profession, the minute you walk through the door, you're an object,” Komonka says. “I think there is just kind of like an anything-goes mentality with clients where [consent] goes out the window. So it's like you're just consenting by being there and being a sex worker, in their brain.”

Power differentials

Power differences can further exarbate sexual harassment, according to nightlife workers and researchers.

In a 2008 article from the SAGE Handbook of Organizational Behavior, Dr. Lilia Cortina and Dr. Jennifer L. Berdahl state, “Power inequality facilitates sexual harassment, and sexual harassment reinforces power inequality.”

According to Waudby and Poulston, power inequality in nightlife industries is linked to the economic power that customers have over workers’ tips.

“I understand you're paying your bill. That's cool,” Bakel says. “I'm still a human fucking being.”

The 2020 Statistics Canada study reported that workers may avoid reporting incidents to avoid losing tips.

“Sometimes I'm desperate enough for the money that I just, like, smile and keep going, stare at the wall, you know,” Komonka says.

Taking action

A 2023 report entitled “Sexual Harassment in the Hospitality, Gaming, and Airline Sectors in Canada,” by the Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children (CREVAWC), found that hospitality workers particularly experience a lack of support from management.

“There are times where women will have issues with clients being inappropriate or touching them inappropriately, and management’s like, ‘Oh well, look at your outfit, or you're just a pretty girl,’” Bakel says.

Pappas says sometimes, management is the problem.

“I've had people slide their hand under my underwear, like into my vagina,” says Jules Komonka, a stripper at a club in the Plateau.

A 2018 study conducted in Portland, Oregon by aca-

“There were under-the-breath comments and sometimes direct comments about how [the female staff] all looked,” Pappas says about former employers.

Since managers are often the only avenue to report incidents of sexual harassment in these industries, harassment by both customers and managers can often go overlooked, according to the CREVAWC report.

“You can't always rely on them,” Komonka says. “It kind of depends on, like, what mood they're in and if they're going to stand up for you.”

Change has got to come

A 2022 economic report by the MTL 24/24 found that women hold 54 per cent of nightlife jobs in Quebec. However, women in management positions are scarce. A 2023 report from Diversity for Social Impact found that women account for only 34 per cent of leadership positions in the hospitality industry in Canada.

Bakel said she wants to see more female staff in managerial roles.

Research shows that more women in management reduces harassment in the workplace. In a 2021 paper titled “Does Board Gender Diversity Reduce Workplace Sexual Harassment?” researchers found that each additional female director is associated with a decrease of 20.71 per cent in the rate of sexual harassment. Komonka says the managers at the club she works at are all men.

“I think that's pretty much like every club, at least in Montreal,” she says.

“This is an industry predominantly held up by women, though not necessarily run by women,” Pappas says. “Kinda bullshit, if you ask me.”

Montreal’s

Maya St-Antoine

Anew exhibition showcasing Montreal’s history through street photography will be on show at the McCord Stewart Museum until Oct. 26.

Pounding the Pavement, sectioned by artists, features 30 series of photographs curated from the McCord collection, representing different points of views of Montreal’s culture since the 1800s.

The show features six main themes, such as “Events and Incidents” and “Talking to the Street,” as well as a short film featuring Concordia University photography students Daniel Cross, Jack Belley and Japhy Saretsky, as they shoot photos at night.

The idea for the exhibition first came to curator Zoë Tousignant in 2019 as a reaction to the museum’s most recent acquisitions, as a way to showcase the McCord collection. The images, consisting of over three million items, are almost entirely handpicked.

The project, which blends social, urban and political photographs, aims to show the legacy street photography in Montreal's history. Some series aim to represent day-to-day life in the city, while others are more political and show protests throughout the years.

Tousignant calls the exhibition an “homage to the city” and said she wanted to highlight multiple perspectives, portraying all sides of Montreal, flattering or not.

“The history we have of Montreal is often one-sided,” she said. “I wanted to find these different voices that explore the different sides.”

She wanted the exhibition to not only celebrate the city but also showcase critical elements, to expose both the good and bad sides of its history.

Stylistically, the exhibition features not only traditional street photographs as we know them, taken spontaneous-

Valerie Akinyi Ogweno

The bike path that leads to Sage Creek is an everlasting river of divinity. The gravel beneath me, white and chalky, earthy and grounding, acts as waves shifting and sifting to move me across swiftly. As I forget myself in the abundance of greenery, bright and intense like LSD; as the trees stretch to greet me, bushes rattle to entertain me. Birds fly to whisper to me secrets of life. I can’t help but slow down in wonder of my surroundings, bowing to the unlinked presence. To my left, a pond stays situated within life; it houses breathing beings, grey and white, muted and mobile, as that life inhabits life, filled wombs, creation manifesting within the metaphysical act of manifestation.

To the right of me, red roses flourish, rich in colour, blushing as the sun winks a twinkle of flirtatious light. My beautiful man-made suburb planted in a sea of houses fighting to be seen. My beautiful man planted in a neighbourhood of people fighting to have their place, waving his hand frantically, waiting to be seen, unwrapped and unravelled a little gift for me. Yet still, my slice of realness is within my suburb.

As I continue to walk, there stands a tall pillar, a rock, and at the bottom, another one sits. One stands to support the likeness of a primal act. Two conscious souls engaging to find physical engagement in one another. One hand on a chest another one on a lower back, Lips connected, Secreting secrets no one could ever understand. As they are lost within each other, an elderly couple walks by, hand in hand, stealing glances and smiling. Their secrets are shared in their souls’ admiration for another, for the young couple, for the man-made suburb. For the man. For as fake as it is, they feel real within it.

ly, but also images that show urbanism and architecture.

“I included artists that might not see themselves as street photographers but nonetheless depicted the city in very dedicated ways,” Tousignant said.

The exhibit also has a special focus on the artists, featuring full series instead of individual photographs. This way, viewers experienced a bigger body of work from each artist and appreciated their unique style and technique.

Among the featured photographers is Concordia professor and acclaimed artist Clara Gutsche. After moving to Montreal in 1970, she quickly fell in love with the city and with photographing it.

Her series “The Windows” (1976-1980) documents storefront displays across Montreal.

“Windows are a visual expression of urban culture. The conscious or unconscious decisions of the shopowners reflect the culture of the city and neighbourhoods,” Gutsche said of her work.

Her series centers more around aesthetics and urbanism. She talks about finding the juxtaposition of unlikely objects amusing, and the photos reminiscent of her summer walks through the Mile End.

Bertrand Carrière’s series “Chronique Nocturne” marks another highlight, with one of its images as the face of the exposition. Carrière reflects on his experience as a street photographer in the ‘70s.

Frank to [William] Klein,” Carrière said. “American photography had a huge impact here.”

He also mentioned Weegee as an inspiration for his series, saying he would go to big events and use the crowd as camouflage to get his pictures.

“I was looking to do something humanistic, a testament to this period of time,” Carrière said.

His series offers a deeply human and cultural side of Montreal, revealing his affection for the city.

“It was the trend, influences were huge, from Robert

The exhibition has many more series to explore, from acclaimed photographers like Brian Merrett, Serge Clément and Gilbert Duclos. It also spotlights lesser-known but equally striking artists, including Edith H. Mather, David W. Marvin, Alan B. Stone and John Taylor.

As they continue to walk, a small boy runs out of a sub path, lips painted blue, tongue painted red, hair ruffled. As he runs, his parents chase behind him. As I reach the end of the path, I look at the ecosystem of God. I go about my day, do my bidding, tithe my soul away, and as I walk back, the sun begins to set. The air is cool. The crickets are chirping, and around are the minds of people who are contemplating their thoughts in the sky. I look to the sky as well, to bear my spirit. As I fix my gaze, the bright colours become clear. Yellow like gold, burnt oranges like expensive cloth, accents of pink and purple as exclamation. As I look, I see the little boy grow to come and contemplate, I see the man bury his wife and come to the path to find her in the sky, I see the young couple steal glances, but eventually resent themselves for those very glances. The pond fights to survive; the sky towers over in darkness. The roses dwindle and show their thorns. The birds fly up above to condemn us for our ways. The trees wilt away in a resounding goodbye. Yet still, the river of a man remains. ces.

Juliet Mackie keeps Métis beadwork tradition alive through her shop, Little

Sarah Housley

JulietMackie was introduced to beading at a young age through her grandmother, who o en stayed busy cra ing at the kitchen table, creating traditional Métis art such as birchbark baskets or beading moccasins.

Beading has long been woven through Mackie’s family history. Her mother, Cathy Richardson Kineweskwêw, shares fond memories of beading with Mackie all around the world, from Aotearoa to Hawai’i and Wales. Together, they have carried this practice across continents and generations.

“It’s a very grounding practice that connects [Métis people] to their culture and makes them feel like they are embodying a living practice,” Mackie said.

She added that beading helps her feel connected to her family and ancestors who practised the same art before her.

Mackie initially found beading di cult as a teenager and didn’t have the headspace to make it a regular practice. It wasn’t until her undergrad in 2016 that she came back to beading a er facilitating an arts and cra s workshop during a volunteering internship at the Montreal Native Women's Shelter. Mackie recalls excitedly calling her grandmother a er beading a keychain.

en in 2019, she took an earring-making workshop with Cory Hunlin, the founder and maker of is Claw, a business that sells beadwork earrings. e rest is history.

“I found that practice right before COVID, so then I had so many earrings, I was giving them as gi s,” Mackie said. “It was also very helpful for my mental health to have something to do, a very mindful practice, so that really distracted me and kept me occupied.”

Mackie launched her Etsy shop, Little Moon Creations, in fall 2020. Anyone can wear her earrings, unless listed otherwise. Today, Mackie operates the business entirely on her own, from making the earrings to packing orders to doing the mail runs.

“I'm really proud of Juliet,” her mother, Richardson Kineweskwêw, said. “I believe she is channelling our ancestors who worked with beads many generations ago.”

Curator and friend Alexandra Nordstrom met Mackie in 2018 when they co-curated an exhibition together and have collaborated on many projects since. Nordstrom even curated Mackie’s rst solo show, Matrilineal Memory, at the Shé:kon Gallery in 2023.

“It’s been such a pleasure to witness Juliet grow Little Moon Creations,” Nordstrom said. “Juliet's business carries a broader signi cance, sustaining and innovating within contemporary Métis beadwork. [...] She brings beauty and con dence to people all over the world by selling her wearable art.”

e Métis people represent one of three recognized Indigenous groups in North America. Mackie’s Métis family traces its roots to Fort Chipewyan in Alberta and Red River, but she grew up a citizen of the Métis nation of British Columbia, in the small shing village of Cowichan Bay.

“Being near the ocean is very important to me,” Mackie said. “Just spending time in that sort of ecosystem is really comforting.”

Mackie explains that Métis beadwork is important not only because it connects people to their ancestors, but because it's a living practice that was not always accessible due to colonization or forced assimilation—times when many cultural practices were outlawed or banned.

“Many Indigenous families were impoverished by colonization and are now applying their energy, creativity and resources to build businesses that are productive and life-sustaining,” Richardson Kineweskwêw said. “Buying from Indigenous artists can be considered an act of reconciliation.”

Mackie’s work re ects that principle. All of her earrings are unique and one of a kind. She does not replicate an earring more than once. at’s why she nds it especially frustrating when fast fashion companies like Temu and Shein appropriate Mackie and other Indigenous artists’ designs.

“ ey are not made to last. Who knows what conditions they are being made in, whatever’s going on,” Mackie said, expressing her concerns over the matter.

“It’s unethical,” she added.

Mackie said supporting fast fashion brands fuels a cycle of exploitation that harms Indigenous artists who rely on their art for income.

“Ethical purchasing can promote social justice and help community members, particularly women, many of whom are mothers,” Richardson Kineweskwêw said.

Meta makes it less likely that followers will actually see her posts unless she pays for advertising.

“You’re just giving them money when they could have just been showing your work to the people who want to see it,” Mackie said.

To adapt, she now sends out a newsletter to stay connected with her customers. She admits the change has frustrated her and slowed her momentum over the years, though her e orts still work.

Despite the obstacles, Mackie said starting Little Moon Creations has brought many positives into her life, including a strong and supportive network of beaders across Montreal and North America.

“It's brought a lot of community and connection to my life,” Mackie said.

Her friends also celebrate her success.

“She brings beauty and con dence to people all over the world by selling her wearable art,” Nordstrom said.

Even with her business, Mackie said her favourite memories involve beading with her mother and grandmother. She recalls how, even in old age, when cataracts made it hard to see, her grandmother would still spend hours on little earrings.

“She was very in awe of my work and very supportive,” Mackie said. “ at was a really nice thing that we shared.”

Her grandmother taught Mackie's mother to bead, and the tradition continues today.

Another major hurdle came when U.S. President Donald Trump got rid of the duty-free “de minimis” shipping exception, meaning all packages under $800 are now subject to border fees. is has deterred many of Mackie’s American customers, who make up between 35 and 45 per cent of her

buyer base.

“We sometimes listen to music, sit with family or just talk with each other, catching up on our news,” Richardson Kineweskwêw shared. “It's so lovely to be working with our hands and feeling calm and relaxed together.”

Instagram has also become a challenge. Once a thriving platform for audience growth, it is now harder to rely on. e new, non-chronological algorithm introduced by

Mackie plans to keep beading. ough she dreamed of expanding Little Moon Creations, she now prefers to keep it small-batch, producing one-of-a-kind pieces made by herself.

ful if people were still interested and supported me,” Mackie said.

“ at’s the dream, really, and have people

“I would be so excited and gratepeople enjoy it.”

Serena Abouljoud

For decades, Palestinians have grappled with memories of their homeland—or at least, what it could have been.

e MAI (Montréal, arts interculturels) opened its doors for the display of e Lost Paintings, a reimagining of the late Maroun Tomb’s last exhibition in Palestine, recreated by Palestinian artists from around the world. Tomb, a Palestinian-Lebanese artist, launched an exhibition featuring 53 oil paintings on Nov. 29, 1947, in Haifa, Palestine.

His opening coincided with the UN’s approval of the partition plan for Palestine, which triggered the Nakba. Known as the catastrophe in Arabic, the Nakba is a term used to reference the expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinians from their homeland between 1947 and 1949.

Soon a er, Tomb and his family were forcibly exiled and never allowed to return. He lost his 53 paintings, along with most of his work before 1948.

Nevertheless, Tomb never stopped painting. His family’s displacement from Haifa led them to Lebanon, where he worked in Tripoli as the head of the art department at the Iraq Petroleum Company. Tomb later opened his own graphic design o ce in Beirut.

He passed away from a heart attack in 1981, just days before the planned opening of his 10th solo exhibition at Galerie Damo in Beirut.

e curators of e Lost Paintings—Joelle Tomb, Haidi Motola and Rula Khoury—have invested in this project for about three years. Joelle and Motola initially connected through Facebook a er discovering that their grandfathers knew each other and belonged to the same group of artists in 1940s Palestine.

Joelle was Tomb’s eldest grandchild. Only she and her sister had the chance to meet him. He passed away when she was two years old.

“I’m the only one who has a photograph with him, so somehow, I feel like it was destiny to start this process and meet Haidi,” she said. “Now I need to continue this. He continued his career until he passed away.”

Shortly a er they connected, Motola’s grandfather passed away. While emptying his apartment, she came across archival material that became the foundation of this exhibition. Among them: an invitation letter for Tomb’s exhibition, written just months before he and his family were expelled.

Another archive revealed a document featuring the titles of Tomb’s 53 oil paintings, many of which referenced speci c

Khoury to join the project. Khoury then reached out to many artists she knew would t well for this exhibition.

Artists chose the title that resonated with them most from Tomb’s paintings and used it as inspiration for their work.

places in Palestine, speci cally Haifa. is inspired a deeper reinterpretation of these sites.

“[ e titles] make you think and imagine Palestine before ‘48,” Motola said. “[Artists] would imagine what Maroun Tomb saw when he was painting this, but also how they themselves see this thing.”

In 2023, a er receiving a grant, Joelle and Motola invited

ey were also encouraged to bring their own family stories into this project.

Joelle, Motola and Khoury also sought to diversify the mediums represented for this project, inviting artists to submit photographs, documentaries, paintings, installations, sculptures and even a virtual reality experience.

“It was a combination of having some framework and direction, while also giving them some freedom to express in their own medium,” Joelle said. “[ is diversity] adds layers of perspective, narratives and opinions. It’s a very rich way of interpreting what’s happening.”

e process shi ed a er the start of Israel’s genocide against the people of Gaza in October 2023. Many of the works ultimately included direct response to the violence in Gaza.

“It’s the same feeling we had in ‘48. It’s similar to what Maroun Tomb had [experienced] in Haifa. It’s happening now again,” Khoury said.

Artists explored themes ranging from displacement to

identity, memory and the power of imagination. Many pieces are coated with symbols related to Palestinian culture and history, including olive trees, oranges, landscapes and tatreez textiles.

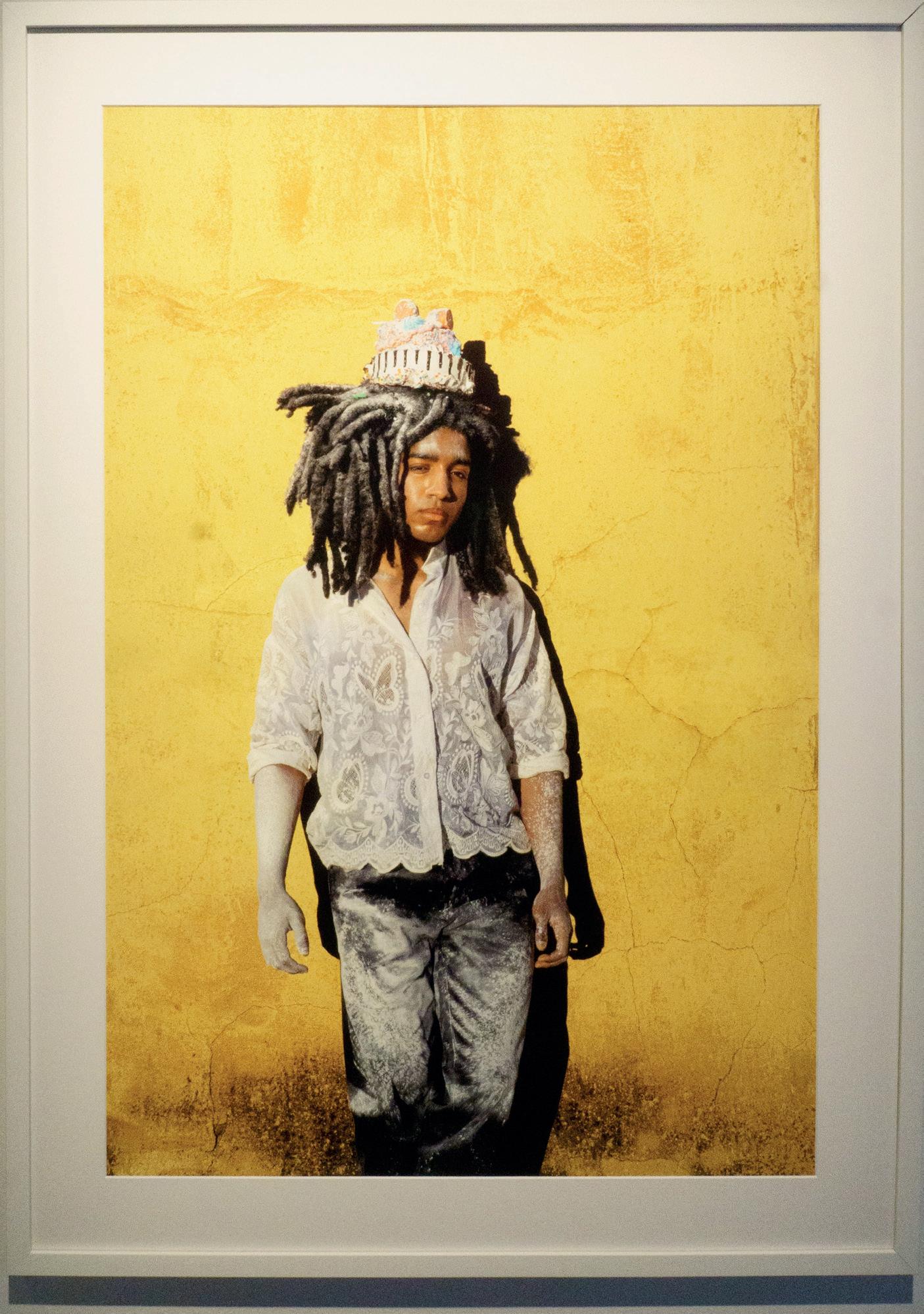

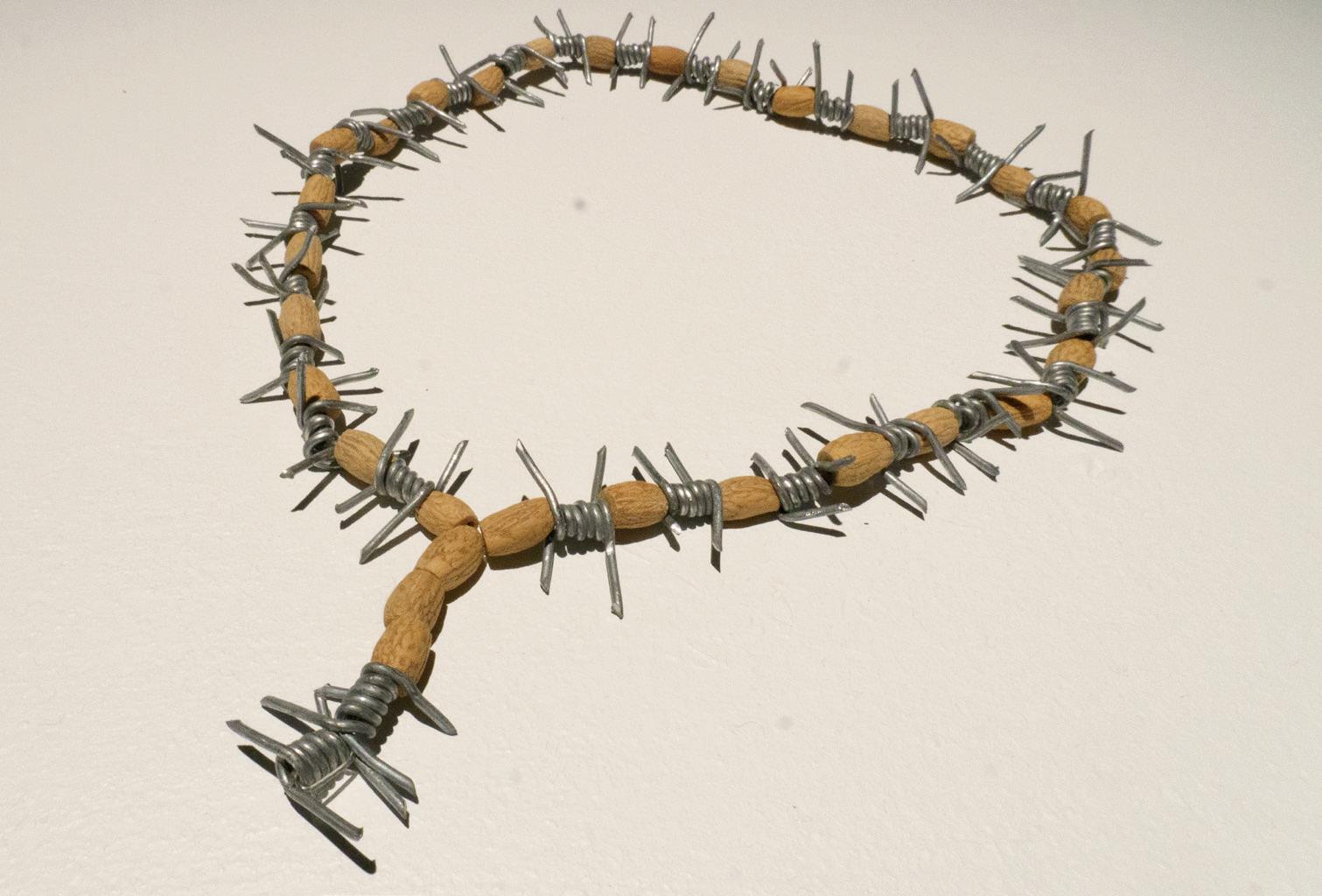

One of the artists, Khaled Jarrar, created a piece confronting the brutal conditions Palestinian political prisoners are forced to endure in Israeli jails. His work showcases a set of prayer beads made of barbed wire, olive pits and rope.

As a child, Jarrar paid his neighbour a visit shortly a er his release from jail. He noticed the man holding prayer beads made of olive pits that he had hidden and dried during his imprisonment. is work alludes to the ways in which Palestinian prisoners nd practices that enable them to express themselves despite the walls that constrain them, a testament to their resilience in the face of time.

Another piece that re ects a similar creative expression is by Raed Issa, an artist from Gaza who used charcoal and natural pigments from co ee, tea and hibiscus. His pieces document genocide, and the ones displayed are the only ones that survived.

“He continued painting while being displaced. He continued painting what he saw around him, using materials he could nd,” Motola said. “In that way, he was also telling the story of what is happening right now.”

Motola also highlighted that the exhibition doesn’t just highlight the 53 lost paintings, but also symbolizes a larger loss and the ongoing colonial erasure of the Palestinian people.

“It’s very essential to be talking about ‘48, not as an event of the past, but an ongoing Nakba and connecting what is happening now to the loss that was back then,” Motola said.

One of the curators’ main objectives for e Lost Paintings was to facilitate connections between artists from all over the world and create an international platform in which they can discover new stories, as well as initiate dialogues rich in perspective.

For Joelle, art used as a powerful tool can give people a privileged position to discuss what they cannot resolve directly. She noted many pieces re ect the artists’ personal selves.

“You can contest history, but you can’t contest personal narratives,” Joelle said.

While Motola believes that art plays a major role in the building of lives and realities, and how they change through creation, envisionment and political imagination, it’s not the only tool at people’s disposal.

“Especially not in times of genocide. We still have to do other things as artists, like being in the streets and putting pressure [on the government],” Motola added.

Khoury sees art as a way of facilitating the understanding of Palestine’s history by spreading the information and elevating the voices of the artists.

“It’s also [a show of] solidarity with what’s happening,” Khoury said.

e exhibition will remain on display at MAI and the artist-run centre articule until Oct. 4.

Max Sinclair-Carter

The Stingers hockey leadership cores will see two new faces spearheading the programs this season.

e men’s team, fresh o its rst Ontario University Athletics (OUA) Championship in program history, now have fourth-year defenceman Simon Lavigne manning the helm. Last season, Lavigne logged a stellar 22 points in 24 games, including 12 goals, en route to capturing the OUA Defenceman of the Year award.

Head coach Marc-André Elément pointed out a few of the many quality traits Lavigne possesses that one would look for in a captain.

“His experience—he played pro—his accountability,” Elément said. “You want a guy who has the respect of the locker room, but also a guy who’s really accountable. He’s going to bring that to our team for sure.”

Last year, Lavigne donned the A for the Stingers. He now nds himself several years into a leadership role, but says he’s spent season a er season learning to become a better leader, particularly from last season’s captain and graduate Gabriel Proulx.

“He was a guy that was there for everyone,” Lavigne said. “No matter who you are, where you’re from, they’re your teammates.”

Lavigne also adds emphasis on the importance of welcoming the new team members, saying he wants to make the di cult transition as easy as possible for them.

Lavigne’s veteran presence will not go unnoticed either. With four seasons in the Quebec Maritimes Junior Hockey League, a handful of international games under his belt and a tryout at the Montreal Canadiens’ recent rookie camp, the 24-year-old knows rsthand what his experience can bring to the team through both performance and presence.

“On the ice, I give my 100 per cent every day, I bring my energy. O the ice, I want to help [my teammates] succeed, be someone that anyone can come talk to for advice,” Lavigne said.

Both coach Elément and captain Lavigne a rm that although bearing the C crest is a big duty, it’s the leadership mentality embodied by the whole team that really makes the di erence.

“It’s not only the captain, it’s the leadership group,” Elément said. “ ey could all have C’s. It’s their locker room, it’s their team.”

For the women’s team, le winger Jessymaude Drapeau will be leading the team in her h year of play, which is only tting a er winning the Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec Leadership and Social Engagement award last season.

She’s looking forward to the new challenges being a captain will bring.

“I’ve been a part of the leadership group for three years, but being the captain, I think it’s the next step,” Drapeau said. “I’m really proud of that honour. It’s exciting.”

With the team looking up to her, Drapeau knows she has to lead by example—but she doesn’t feel any pressure. To her, the captaincy isn’t a burden, but a con rmation.

“Just being who I am, I think people elected me for who I am; I don’t need to change,” she said.

Drapeau’s competitive edge has always been a big factor in her game, too, which will certainly play a role in hopefully leading the Stingers back to the U Sports women’s hockey national championship game.

Last season, they nished fourth at the tournament, marking the rst time in four years they failed to reach the nals and

leaving a bitter taste in their mouths.

“We know that we could’ve nished on a better note,” Drapeau said. “But we’re here and we’re ready more than ever. I have so much trust in this team, I know we’re going to reach new levels.”

New levels bode extremely well for the Stingers, considering they’ve won the national championship twice in the last four years. But if there was ever someone to lead alongside Drapeau and make that happen, head coach Julie Chu would be that someone.

Decorated in accolades in both her playing and coaching career—including the U Sports Coach of the Year award in the past two seasons—Chu knows what it takes to bounce back from a disappointing result.

“She’s a great leader,” Drapeau said. “She’s not only a coach, but she leads our team in every way.”

Drapeau says Chu has really helped mould her into the leader she is today, thanks to her social and “people-person” approach to coaching. She believes that her coach’s teaching is a big reason why she’s captain of this season’s team.

“In my rst few years, I couldn’t care less about people, I was just there to win hockey games,” Drapeau said. “Starting in year three, I really became a people-person. I love my people around me.”

Drapeau and the women’s team hit the road to take on the Université de Montréal Carabins in their rst match of the season on Friday, Oct. 17, and Lavigne leads the men’s team against the Royal Military College of Canada Paladins on Saturday, Oct. 4.

While both teams enter another season with high expectations, their captains have shown they’re up for the challenge.

Samuel Kayll

As the 2025-26 U Sports university athletic seasons continue throughout the fall, each team holds optimism for change and improvement. However, starting next season, a di erent kind of change could upend the balance of university sports for good.

Beginning in the 2026-27 season, the U Sports governing body has announced that student-athletes in their rst or second academic year will be able to transfer without penalty. e decision focuses on improved player empowerment, providing young athletes with the opportunity to make decisions to bene t their future.

" is is an important step forward for U Sports and for our student-athletes,” said U Sports CEO Pierre Arsenault in a press re-

lease. “ e landscape of post-secondary sport is evolving, and our role is to ensure our policies re ect the needs of those we serve.”

Previously, non-graduating transfers had to sit out 365 days from their last date of competition, with special exceptions made for academic progression and sports like cross-country, swimming, and track and eld.

“A meaningful amount of transfer activity takes place during the rst two academic years of a student-athlete’s journey, o en when they are working to nd the right t academically, athletically and personally,” said Tara Hahto, U Sports’ director of compliance and eligibility. “ is policy change responds directly to that reality.”

D’Arcy Ryan, Concordia University’s director of recreation and athletics, noted that the new transfer rule didn’t come as a surprise.

“We've been having conversations with regard to this one time on encumbered transfer rules for a couple of years now at U Sports,” Ryan said. “ ey've seen the number of appeals increase over the past several years.”

At the outset, it’s easy to imagine the impact the rules could have on teams and their rosters. In a conference like the Réseau du sport étudiant du Québec, Ryan acknowledged that a lack of continuity and roster stability could tank a team’s aspirations.

“When you're trying to build a program and you put a lot of e ort into recruiting, and your vision for that student is poten-

tially in year three or four, but they jump ship sooner than that, there's that continuity issue,” Ryan said.

However, while the changes mark a clear movement in the direction of player empowerment, they aren’t as drastic as the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s free-for-all between players and schools in the U.S. e U Sports change focuses its attention on providing exibility and fairness to the students who may not have found the right program.

Arsenault echoed this message in his statement.

“By providing a more responsive system for student-athletes at the start of their academic careers, we are empowering them to

nd their best program t—both in the classroom and in competition,” he said.

Ryan agreed, noting that the onus falls on the athletes to make decisions and interact with other programs.

“When a student is committed to an institution, other schools and coaches cannot initiate contact with them,” Ryan said. “So it's up to the student if they're not happy in the program that they're in to reach out.”

But that’s not to say that teams won’t feel the impact. As stronger programs attract transfers from lesser-known schools, the possibility of a recruiting surge in the competitive imbalance

looms, with the pillaged teams le to pick up the pieces.

“We're gonna have to really sell the strengths of our individual programs to try and retain these students,” Ryan said. “But in the end, if they're not happy, then those conversations happen early on with the coach so that they can start to plan.”

As schools prepare for the changes to come, it’s hard to predict exactly how teams will adjust. But for the moment, there’s one clear winner.

“We believe this decision puts student-athletes rst, which is exactly where they belong,” Arsenault said.

How schools adapt remains to be seen.

It’s time for governing bodies to eliminate the international double standard and make a change

Samuel Kayll

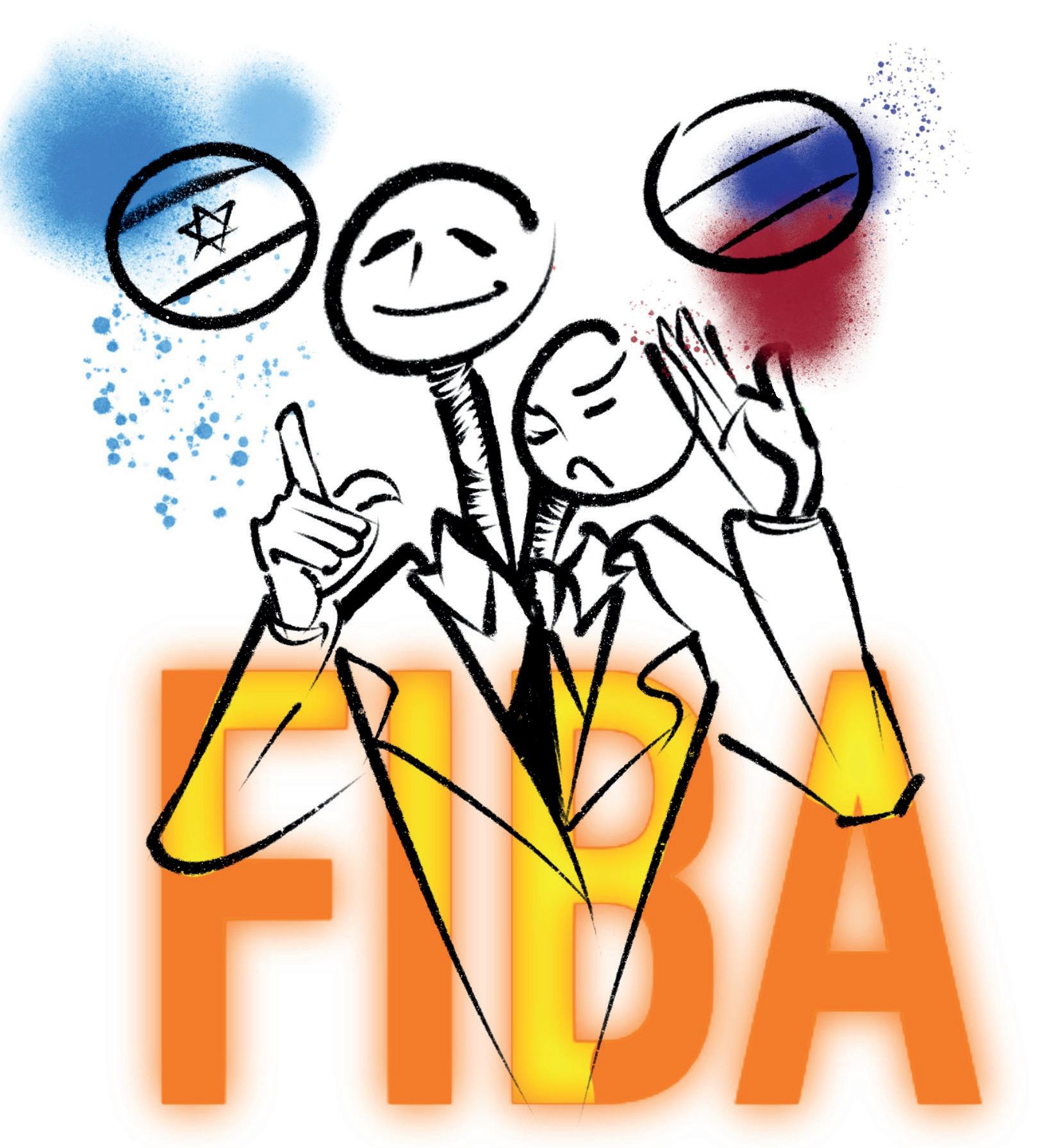

This August, 24 countries gathered in Cyprus, Finland, Poland and Latvia to compete for the 2025 EuroBasket championship. Among them, a questionable selection: Israel.

On the court, the Blue and Whites made relatively little noise. Outside of an upset win over European powerhouse France, Israel nished fourth in Group D, quali ed for the knockout stage, and lost a close Round of 16 matchup with eventual semi nalists Greece. A solid, if not unspectacular, showing.

Yet o the court, sparks ew throughout Israel’s run. Polish and French fans booed the Israeli national anthem before matches against the two nations. Quotes from star forward Deni Avdija surfaced surrounding his enthusiasm for his service in the Israel Defense Forces.

And in the lead-up to that loss to Greece, head coach Ariel Beit-Halahmy proclaimed that the team would “need an M-16” to stop two-time NBA MVP Giannis Antetokounmpo.

To many basketball fans and millions of people worldwide, Israel’s competition in EuroBasket represents just one of several missed opportunities to take a stand against the ongoing genocide Israel is waging against the Palestinian people.

e UN’s o cial declaration that Israel has committed genocide in the Gaza Strip, alongside 156 member states o cially recognizing Palestine as a sovereign nation, has only added fuel to the re.

So why hasn’t anything happened—and what could we look to for answers?

Israel’s representation in international athletics draws controversy regardless of the sport. Pressure from fans has pushed the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) to consider eliminating Israel from World Cup qualification, but no concrete action has been taken yet.

Obeid—nicknamed the “Palestinian Pele”—and basketball player Mohammed Shaalan represent just two of the 808 athletes and coaches murdered by Israeli forces since Oct. 7, 2023.

Similar pressure still didn’t stop the Israeli national team from competing at the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris. Even in Montreal, protests erupted at the 2025 Cycling Grand Prix over the inclusion of a professional Israeli team.

In Gaza, Israel continues to cripple the growth of Palestinian sports at every turn.

Israel’s sportswashing campaign has led to the destruction of stadiums and training areas and the restriction of the movement of Palestinian athletes between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Prominent Palestinian athletes such as soccer player Suleiman

Yet up until now, Israel still competes in international events. Organizations like the Fédération internationale de basketball, Fédération internationale de football association and the International Olympic Committee continue to shu e their feet on Israel’s inclusion in competitions such as EuroBasket, the World Cup and the Olympics, despite a near-unanimous call to action from the rest of the world.

It’s time to change that.

While athletes like Jordanian tennis player Abdellah Shelbayh—who refused to face an Israeli player at a tournament in

Greece—display their bravery and integrity through their activism, athletes shouldn’t need to choose between competition and standing up for justice.

ere’s a simple solution to this: ban Israel and Israeli teams from competition to send the message that the world will not tolerate genocide.

We can see examples of this ban’s application through a similar world con ict. Shortly a er Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, international organizations brought down the hammer, banning Russia from World Cup and European Championship matches and stripping St. Petersburg of the right to host the 2025 UEFA Champions League nal.

In the case of Palestine, though, racism against those labelled as “Muslim” or “Arab” o en leads Western actors to view the genocide as simply a tragic result of a war-torn region. is implicit discrimination and tendency to only humanize white victims constitutes a double standard and has led to the disparity in the response of sports organizations.

But Russia and Israel are both guilty of violating human rights—and if one is being penalized for it, then it only follows that the other is as well.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez fuelled these proposals a er anti-Israel protesters disrupted the Vuelta a España cycling race on Aug. 27. e protesters called Israel’s genocidal campaign a “barbarity” and encouraged other nations to boycott Israel from international events. Even Israel recognizes the writing on the wall, with an Israeli official stating on the website Mako, “We are one step away from reaching the situation of Russia.”

But “one step away” won’t solve this. We can’t stand for “one step away.” UEFA unveiled a banner reading, “Stop killing children, Stop killing civilians” at the 2025 Super Cup, but half-hearted o erings like this can't mark the end of the line.

e world’s governments need to take a hard stance on the genocide in Gaza and halt Israel’s sportswashing in its tracks.

Banning Israel and Israeli teams from international competition isn’t some revolutionary, unprecedented pipedream. It’s possible, backed up by evidence—and the only way forward.

@jaidennne Jaiden Gales

Every Montrealer’s worst nightmare? Needing to pee while out and about.

Accessible public restrooms are not a luxury; they are a basic human need. As psychologist Abraham Maslow would say, they sit right alongside food, water and safety in the hierarchy of needs, essential for everyone’s dignity and comfort.

Montreal’s approach to this basic need has long been shaped by policies and social attitudes that ignored—or even punished—those who required access.

In the 1970s, former mayor Jean Drapeau had hundreds of trees on Mount Royal cut down to prevent the area from being used for illicit sexual encounters, a move rooted in homophobia. Suspicions are that the same mindset also drove the closure of public washrooms, and the few that remained were o en used as a target and scapegoat for unhoused individuals who seek shelter in the few and far between public buildings.

Today, the consequences of that infrastructure gap are felt by everyone in Montreal—from the unhoused population to delivery drivers, from those with chronic illnesses and those with disabilities.

e lack of public restrooms e ectively degrades the value and accessibility of Montreal’s public spaces. Public parks and the Lachine Canal—already scarce “third spaces”—become harder to enjoy when there’s nowhere to go.

It’s 2025, and we’re still constrained by decades-old, discriminatory policies. Montreal, it’s time to catch up.

“What about a co ee shop?”

Local businesses shouldn’t have to bear the burden of shouldering a rise in maintenance costs due to increased usage of their bathrooms. And in today’s economy, Montrealers and visitors alike shouldn’t have to buy a $7 latte just to access a restroom.

So, let’s ask ourselves: Why should anyone have to beg or buy for the right to relieve themselves?

Luckily, there is a comment on a Reddit post, “Why is there

no public bathrooms in Montreal?”, that lists public bathrooms in Montreal with details such as their location and hours of accessibility. It’s actually incredibly helpful and de nitely worth bookmarking (just in case!).

And to my fellow tummy ache survivors: hope is not completely lost! As of summer 2025, the city has invested $45 million in “projects that were both proposed and selected by the population.” One of those is constructing public washrooms along the Lachine Canal and in various parks.

Progress is nally underway, but it shouldn’t have taken our elected o cials roughly 50 years to reach this point. Everyone deserves a place to relieve themselves with dignity. It is shameful that Montreal has historically neglected this basic human right that infringes on the overall experience of this beautiful city, both for citizens and tourists alike.

Montreal can host festivals, build condo towers and continually undertake mega-projects, but somehow, a place to pee has been too much to ask.

For many Concordia University students, the challenge isn’t the syllabus—it’s surviving the waitlist.

On paper, Concordia o ers an impressive variety of courses across disciplines, from so ware engineering to cultural studies. But the reality is far more limited. A pervasive waitlist culture and limited course availability mean that many students can’t enroll in the classes they need, despite paying tuition and planning their studies months in advance.

Some professors go above and beyond to accommodate students, adding them to full classes before administrative deadlines. In

my first year, I had a professor who noticed I was waitlisted for about a month and added me to his class just before the deadline. But relying on individual acts of goodwill is not a sustainable system. is isn’t an isolated issue—it’s structural. Large lecture halls sit underutilized, online resources are abundant, and yet students are routinely shut out of courses they require.

A 2025 AACRAO survey indicated that most institutions prioritize faculty availability and preference over student needs when scheduling courses. Only 43 per cent of respondents used data on student educational plans to forecast demand. at is not to mention that a lot of courses are outdated and have no signicance to a lot of students’ careers. Something needs to change.

Scroll through Concordia’s website and you’ll find a seemingly endless catalogue. It seems extravagant that this university is able to find professors who could teach an entire course about Kanye West! But the real problem isn’t what’s listed—it’s getting a seat. Almost every student I know has hit a waitlist at some point. Capacity is limited, yes, but with massive lecture halls across the downtown campus, I nd it hard to believe that space is truly the issue.

Take my experience trying to enroll in a second-year soware engineering course. My section was merged with another, and although I was rst on the waitlist, I was pushed to fourth because three students were already waiting for the other section. By the time registration closed, I couldn’t o cially take the course without paying late fees and scrambling to catch up on missed material. When I met with an academic advisor, my only options were to take another course or risk falling behind entirely. is shouldn’t de ne the student experience at Concordia. If the university promotes a diverse and expansive course catalogue, it should ensure students can actually access those courses.

A solution is long overdue.

e university should proactively ensure that enrolment matches student demand, rather than leaving it to chance or luck. Clearer policies, expanded capacity and better scheduling would turn Concordia’s promise of educational opportunity into a reality.

Students come here to learn and build a future—Concordia needs to make sure that the system supports them, not obstructs them.

Everyone wants to feel heard—but how o en do we really listen? Did you hear what your friend just told you? Or were you already thinking about what to say next?

If that hits close to home, you’re not alone. Society has conditioned us to see speed as an inevitable part of life—prompting us to keep moving, think ahead, plan our next steps—because in a fast-paced world, stopping feels like falling behind.

We live in an outcome-driven capitalist society that attempts to condense time to fast-track the product. We accelerate the pace of our everyday actions in the hopes that it will maximize productivity and, by extension, pro t.

It goes without saying that technology has only increased the pace of our day-to-day lives. The instant gratification associated with social media and the internet reinforces this relentless need for speed. It’s no wonder our conversations have become fast-paced— and it comes at a cost.

Being so preoccupied with the future ultimately prevents us from showing up as our full selves in the moment.

We’re not present. We’re distracted. Our minds are 12 steps ahead of our bodies.

As a result, we’re not fully registering each other’s words. Sure, our ears may pick up on what is being said, but we're not letting it affect us. We’re not hearing one another. We're just responding to keep moving forward rather than engaging with each other meaningfully.

Conversations have become more like simultaneous interjecting monologues rather than true dialogue.

I came to this realization while studying acting in CEGEP.

For most of my life, I was so focused on what I wanted to say in a conversation that I wouldn't fully grasp what was being said to me. My passion for the topic of conversation would o en override my ability to genuinely take in the words being spoken. I was so wrapped up in my own experience that I wasn’t fully cognizant of what the other person was bringing to the table.

And I de nitely wasn’t alone in this. A study conducted by the authors of e Plateau E ect suggests that the human brain can only retain about half of what we hear. is means most of us may miss more than we realize in conversation.

It was a piece of acting advice from my professor that changed my perspective on listening. She emphasized the importance of letting the words hit me, absorbing their impact, before responding to my scene partner. at imagery alone completely transformed how I viewed listening. Not only as an actor, but as a human being.

At the end of the day, we all want to feel seen, valued and heard. Human connection is essential—we thrive in community, not in isolation. To truly show up for one another, we need to slow down, be more present and listen with intent. Only then can the words of others land, resonate and shape the way we relate to each other.

Breathe in. Breathe out. Let the words hit you.

@notsostylin

Ihave to confess: I’m not the best at keeping in touch.

If you know me, chances are I’ve ghosted you before or suggested plans and then failed to follow through. I struggle to maintain meaningful connections with people who expect instant replies and constant availability. Between the chaos of the world, the whirlwind of starting university, and simply surviving my 20s, I’ve learned to value the friendships with the fewest expectations.

Time feels like it’s always running out and keeping up with everyone online is increasingly exhausting. But over time, I’ve realized that friendship today is o en performative. Texts and social media check-ins aren’t enough; meaningful connections take e ort, patience and presence. I might not answer right away, and I might not always be available—but too o en, we measure friendship in all the wrong ways.

I’ve received countless well-meaning, guilt-ridden “just checking in” and “I miss you so much” texts, but few people have sat with me at my lowest, without expecting me to look good or act happy. e friends who do go out of their way prove that real connection is earned, not assumed.

Once, while I was away, I asked a friend in Montreal to wake up before 8 a.m. to hand my spare keys to someone because I’d forgotten to plan ahead of my departure. She did it—and the next day, she sent me a post on social media perfectly describing the situation: “Inconvenience is the price of community.” is small act is exactly what I mean when I say meaningful friendships require e ort—they’re about showing up in real, sometimes inconvenient ways.

With technology becoming more intrusive and companies getting greed-

ier, relying on people has never felt more important. But building a “village” requires e ort. It requires patience and the courage to let go of the fear of being awkward, cringe or too much. Real life isn’t as neat as an Instagram grid; people are messy and multidimensional. Social interactions can be uncomfortable, and people can be annoying— but that’s part of the deal. If you want meaningful friendships, you have to give something in return.

I don’t care if we haven’t talked in years, or if responses are spread out over months. If you need me, I’ll show up. Because friendship isn’t about appearances or constant messaging; it’s about presence. In a world full of performative check-ins, showing up authentically is the statement I choose to make.

The right album

Emma Augello

play, and the music hits—but rst, your eyes land on the album cover. at image grabs you before a single note does, hinting at the story, the vibe, the feeling inside.

For me, an album cover is just as important as the music itself. It’s the rst thing you see, the image that draws you in—and sometimes even the reason you give the album a chance. Album covers shape our listening experience; they spark cultural conversations and build identity.

Some covers stick with us and become timeless icons. On a friend’s wall, printed on a worn-out T-shirt, or even scrolling past them in our feed. They spark something familiar in us. In that instant, the image brings the music rushing back, along with the feelings and memories tied to it.

Without them, music would lose meaning.

Cover art serves as the bridge between artist and listener; it creates unity. In today’s digital age, artists have access to endless creative tools and di erent media at their disposal, and album covers have become another canvas for them to express their vision. ey allow the artist to tie the theme of the album together. ese covers aren’t just pretty packaging; the visual art ampli es the sound and feeling.

Critics have called it demeaning to women, labelling it as “regressive” and suggesting that it shows a power imbalance. Others defended it as merely satire, arguing that Sabrina was playfully commenting on how patriarchal societies objectify women. e mix of outrage and support shows just how deeply album art can engage an audience, turning a single image into a

pressed play. is is what great album art does: it sparks conversations, provokes the listener and allows them to feel.

Of course, not every album cover is groundbreaking. Some are simple portraits, others are minimalist designs that don’t add much depth. But even these covers contribute to an album's identity. Imagine scrolling through Spotify or ipping through vinyl racks and seeing nothing but blank covers. e music might still be good, but the experience would feel incomplete.

Album covers also create conversation.

Take Sabrina Carpenter’s recent cover for her new album, Man’s Best Friend. e image of the artist kneeling, hand resting on a man’s thigh as he holds her hair, set o a wave of controversy across her fandom.

focal point for debate and re ection. Album covers don’t just reect the artist’s vision; they become a shared experience, shaping how the music is interpreted and remembered.

Whether you view it as o ensive or satire, the fact remains: the image got a lot of people talking. It added a layer of interpretation to the album, engaging the audience before they even

Some covers even become cultural touchstones. Take Pink Floyd’s album e Dark Side of the Moon, for example. Its prism refracting light into a rainbow is one of the most recognizable images in music history. Minimalist yet profound, it captured the band’s exploration of time, existence and perception. e prism didn’t just decorate the album; over time, it became closely associated with psychedelic rock, turning a simple design into a lasting symbol.

So yes, album covers still matter. ey're vital. ey give us something to hold onto in a world of endless streaming and playlists. For me, imagining music without album art feels impossible; it would be like reading a novel with no cover or watching a movie with no poster. e art pulls you in, sets the tone, and stays in your memory long a er the songs fade.

Album covers are the rst hello, a preview of what's to come. A striking cover can make you pause, wonder and make assumptions even before you press play. Cover art gives music personality and story, making the whole experience richer.

Album covers remind us that music isn’t just sound, it’s an experience. And without art to frame it, it would be far less meaningful.

Olivia Morello @morellooooo

isn’t always synonymous with exclusion. But too o en, that’s exactly how it works.

Gatekeeping is the activity of trying to control who has access to certain opportunities, power, or resources, and who does not. The idea is that by keeping certain spaces or communities closed, we protect them from harm, and in some cases, that’s true. Without boundaries, marginalized groups can lose safe spaces, subcultures can be watered down, and unique communities can be commodified.

I’ve experienced the value of protective gatekeeping rsthand.

At a queer rave, my friends and I felt more at ease knowing the space wasn’t advertised to everyone; it gave us the freedom to express ourselves authentically. e same applies to other communities, like BIPOC spaces, which need protection from voyeurism and appropriation.

Marginalized groups create and maintain safe spaces as buffers against microaggressions, discrimination, and cultural appropriation. Gatekeeping in this context could be essential for preserving safety and self-expression.

But gatekeeping doesn’t always serve that purpose. Sometimes it looks like someone refusing to share the location of a spot from their Instagram story, the name of an underground bar, or even the brand of clothing they’re wearing. In those moments, it’s not about protection, but about exclusion.

It’s natural to want to hold onto something special, to shield it from becoming commodified or overrun by the mainstream crowd.

But we have to ask ourselves: is this really about preservation, or ego? And more importantly, who gave us the authority to decide?

e truth is, we’re not the owners of these spaces, artists or brands. So why do we feel entitled to restrict access? Sometimes, what the creators, artists and business owners actually need most is support and visibility, not secrecy.

Most of the time, gatekeeping doesn’t function as protection, and o en, it slips into elitism, where people decide who is “worthy” of knowing.

Gatekeeping in the music industry, for example, can be deeply damaging because it o en leads to exclusion, stagnation and inequality within communities.

By dismissing new members and labelling certain artists as “not real” musicians, gatekeepers create barriers that prevent fresh talent from entering the scene. is exclusion not only alienates fans and emerging artists but also limits diversity in musical expression.

Humanity is fundamentally rooted in forming communities, sharing resources and working together cooperatively. Humans have an intrinsic need to belong, rooted in our survival through connection and cooperation. Gatekeeping works against this drive

by creating barriers to sharing, collaboration and community. Necessary boundaries o en appear naturally. A niche rock bar will always attract people who love that type of music, and those who don’t will naturally gravitate toward something else. So we could take the chance to share, and maybe the person we think “doesn’t belong” will surprise us and discover a new passion, or their new favourite place.

Instead of deciding who deserves access, we should focus more on creating meaningful spaces. Gatekeeping might preserve one’s ego, but openness develops community.

The Longueuil police murdered a child on Sept. 21. His name was Nooran Rezayi, and he was 15 years old.