Maria Cholakova @_maria_cholakova_

Julianna Smith, a Concordia Student Union (CSU) full-time sta member, was working from her o ce when she received an email from Concordia University’s director of Campus Safety and Prevention Services (CSPS), informing her that she had been barred from campus inde nitely.

e email, sent on Oct. 29, accused the CSU campaigns coordinator of helping student protesters in the Oct. 6 pro-Palestine strikes by allegedly “participat[ing] in preparing and equipping persons who then engaged in aggressive harassment of students and others and caused many class disruptions.”

e email further claimed Smith “assisted others in gathering and wearing disguises and masks, all so that the individuals could not be identi ed or face consequences for their behaviour."

Context matters

As the campaigns coordinator at the CSU, Smith’s role is to mobilize students and assist in the coordination of mobilization e orts on campus. She said it is her responsibility to work with students on campaigns aligning with political positions held by the CSU that undergraduate students have collectively voted on.

“Undergraduate students have all had the opportunity to voice their opinion on the di erent political positions that the student union takes,” Smith said. “As a sta member, I don't have a say in what these political positions are.”

On Oct. 6 and 7, ten Concordia student associations went on strike, demanding that Concordia divest from companies complicit in Israel’s genocide in Gaza.

Alongside Concordia, student associations from McGill University, Université de Montréal, Université du Québec à Montréal, CEGEP Saint Laurent, Maisonneuve College and CEGEP Marie Victorin were also on strike. is totalled over 80,000 students o cially on strike, according to Students for Palestine’s Honour and Resistance Concordia.

On the morning of Oct. 6, Smith said she was present at Le Frigo Vert as part of her CSU responsibilities, which included listening to student concerns, documenting testimonies a er altercations between students and CSPS, and ensuring safe and successful mobilization.

Le Frigo Vert was the students’ home base for strike action and is a self-described anti-capitalist, anti-colonial and anti-oppression food collective.

According to CSU external a airs and mobilization coordinator Danna Ballantyne, although the CSU was not o cially part of the strike, the union still has responsibility towards students.

“ e CSU had no part whatsoever in picketing or blocking of classes. We did have a role to play in educating students

on what purposes strikes can serve in an academic context,” Ballantyne said. “When it came to the strikes, there was a lot of work done to educate students on their rights as students and to protect themselves from repression on campus.”

As part of her CSU responsibilities, Smith is expected to be present during any student mobilization events.

“Anytime there's a strike, I'm working 14-hour days to make sure that there's someone there to help support students and be on the ground making sure that things get done,” Smith said. “ ere's a lot of logistical work that happens when there's a big event.”

Smith also clari ed that, because strike action had become a common occurrence at Concordia in recent years, her help was not as necessary.

“ e students already have the institutional knowledge within their communities,” Smith said. “ ey don't need me, and so I'm not going to hold their hands when they don't need that.”

e Oct. 6 strike ended in two arrests and a case of CSPS o cers kneeling on one protester’s back. e university at the time also accused protesters of being violent towards other students and CSPS o cers.

Accusations of repression of pro-Palestine voices on campus

A er receiving the letter barring her from her workspace, Smith spoke to her lawyer and decided to ght the ban.

Smith’s lawyers sent a cease and desist letter to CSPS director Darren Dumoulin. Communication regarding the ban is continuing only through the lawyers of each respective party.

Smith claims that she was not given any prior warning for her ban, nor was the CSU as her employer. She said she was not given any resources to contest the claim, nor provided with any evidence supporting the university’s claims. e claims that led to her ban include Smith assisting in the preparation and equipping of protesters who then engaged in aggressive harassment of students.

Despite being in what she calls “solution mode,” as time passed, Smith became increasingly frustrated by what she sees as the university repressing her.

“ ey were weaponizing a policy that is meant to keep dangerous people o of campus, and they were using it to target me,” she said. “Just the accusation that I could ever be dangerous or a threat to a student, [...] it really hurts me.”

Ballantyne says the university’s reaction is part of what she calls an ongoing suppression of pro-Palestine voices on campus.

“ e university is bypassing good faith conversations with student leaders, student activists and organizers,” Ballantyne

said. “It really does just come down to the fact that the administration is making these choices and removing people from campus based purely on unfounded or unproven allegations relating to their political activism on campus.”

Ballantyne explained that the university’s decision to ban a CSU full-time sta member is an escalation.

“[ e ban] is a step further than they had gone in the previous years,” Ballantyne said. “ e targeting of a CSU sta member, a full-time employee of the student union, is one step further than [sending] students to the O ce of Rights and Responsibilities (ORR).”

Brittany Allison, the CSU Student Advocacy Centre’s interim manager, says the centre has seen a large increase in ORR complaints in the past three years.

In the 2022-23 academic year, the centre saw an average of 15 ORR complaints. e following academic year, 202324, they saw approximately 50 cases. e 2024-25 academic year has seen a similar number of cases to the year prior: since the start of this academic year, the centre has already seen close to 15 cases.

Ballantyne stressed that the CSU is taking the university’s ban very seriously, as she believes it might set a “dangerous and harmful” precedent for future student organizations.

Concordia spokesperson Julie Fortier denied that the university is suppressing speech or action on campus, “unless it turns violent.”

Fortier also outlined the Code of Rights and Responsibilities, which states that obstruction or disruption of university activities, unauthorized entry into any university property, concealing one’s identity, and encouraging community members to engage in such disallowed activities are prohibited.

“Individuals external to the university, including CSU employees, are expected to conduct themselves in line with our Code and policies,” Fortier said in an email to e Link. “Both the Code and the Policy on Campus Public Safety and Security outline that external individuals who do not respect this can be banned from university premises.”

Activists have widely criticized Concordia’s policy prohibiting the wearing of masks or face coverings on campus, due to their importance in protecting against doxxing and academic repercussions for activists, as well as infectious diseases more generally.

Where do we go from here?

As Smith is barred from Concordia’s campus, she is working from home or from Le Frigo Vert.

Despite being able to work remotely, Smith said she still feels a ected by the ban.

“I have a team of people that I work with. Now, I can't be in the o ce with them and work together,” she said. “We work extremely collaboratively together. e thing that's been impacted is the richness of that collaborative nature, which I think really is a shame.”

Smith’s department at the CSU has released an open letter for students to sign in her support.

e letter demands that the university take immediate action to reverse the inde nite ban from campus; issue a formal apology; restore the suspended students' full rights and access to campus; and mitigate further instances of security and police violence against students and community members on campus, by emphasizing de-escalation as the primary mode of response and limiting police presence.

According to Ballantyne, since the news of the ban has spread among the community, Smith has received an enormous outpouring of support.

“With that came a lot of con dence that we are doing the right thing. at we are supported not only by our community within Concordia but by many communities on the outside,” Ballantyne said. “Any attempt by the university to repress that kind of mobilizing is not only clear repression and clear interference in student politics, but it's also an a rmation and a testament to the e ectiveness of those kinds of strategies.”

Cedric Gallant

Inuit and Cree fought tooth and nail for this agreement, but at what cost?

Fi y years ago, on Nov. 11, 1975, lives were changed forever a er the Cree and Inuit of Quebec signed the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA).

e document was the rst modern treaty between Canada and Indigenous nations, and set the tone for every agreement that came a er.

In the early 1970s, Quebec announced its “project of the century,” which was a $13.7 billion hydroelectric dam project stretching from the La Grande-1 dam to the Caniapiscau Reservoir. at amounts to 800 kilometres in length.

e Cree, who have lived in this region of Quebec for thousands of years, were not noti ed that this project was going forward. ey knew all too well the damage that would ensue: ooding of traditional hunting grounds and mass displacement of ecosystems and people.

e Inuit joined in the conversation, knowing that the Caniapiscau Reservoir eventually feeds the Koksoak River, a major travel-

ling and hunting river for Inuit living near the Ungava Bay.

Land defenders from both Indigenous communities, led by a group of young advocates, brought the Quebec government to court.

In a landmark 1973 decision by Quebec Superior Court Judge Albert Malouf, the Cree and Inuit won against the Government of Quebec. Not a week later, Quebec’s Court of Appeal suspended the ruling, but enforced that the government sit down with both Indigenous groups to negotiate.

e project continued, and its feared environmental damages became reality. e dam would ood an area of 11,500 square kilometres and force the displacement of 2,300 people living in the village of Fort George.

Only a er Malouf's decision did both Indigenous groups enter the negotiation table, advocating for better health care, better education and establishing reliable services in the region, but the Government of Quebec made sure there was a cost to that.

Provision 2.1 of the JBNQA states that the Inuit and the Cree

of Quebec needed to “cede, release, surrender and convey all their Native claims, rights, titles and interests” of their territory, Eeyou Istchee and Nunavik, to Quebec and Canada.

is one provision became the standard in modern treaty agreements.

Since then, Canada and its provinces have signed 26 agreements with Indigenous communities. ey have used similar language to extinguish Indigenous rights to their land up until 2005, with the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement.

The JBNQA established local governing agencies in the Grand Council of the Crees and the Kativik Regional Government, and in their regional health boards and school boards. Many questions remain about whether the agreement had a positive or negative impact on the self-governance capacities of the 25 Indigenous communities it represents.

Faculty in precarious roles say they feel betrayed as the university moves to trim $1 million from steep deficit

India Das-Brown

The start of November has been marked by grief, outrage and betrayal, shared several Concordia University faculty members. Word has spread quickly that the administration will not renew any limited-term teaching contracts next year.

“I felt like a school kid getting expelled,” said limited-term English professor Reza Taher-Kermani, describing the a ernoon he received the news. “ e university is tossing us o , throwing us like garbage.”

According to the university, the decision comes as part of e orts to stay within its approved de cit target of $31.6 million for scal year 2025-26. Back in May, president Graham Carr said in a statement that the shortfall could reach $84 million without any intervention.

For limited-term classics professor Lauren Kaplow, the news arrived during class via email.

“My students were taking an exam, and I was supervising the exam,” Kaplow said. “I was really upset.”

e devil’s in the details

Limited-term appointments (LTAs) are contract positions with a xed end date, o en one year in length, and no guarantee of renewal or consideration for tenure, according to the collective agreement signed between the Concordia University Faculty Association (CUFA) and the university in 2023.

Anna She el, principal and professor of Concordia’s School of Community and Public A airs, calls the timing of the cancellations “particularly cruel.” She el was under the impression that next year would be the rst year LTAs could apply to convert their positions into extended-term appointments (ETAs), positions that o er renewable terms and greater job security under the collective agreement.

e collective agreement stipulates that if the provost approves a department’s LTA “for four consecutive years to respond to the same speci c teaching needs [...] and the positions are lled in each of the rst three years,” then in the

fourth year, “the limited-term position shall be allocated as an extended-term position.”

If the countdown began in the 2023-24 academic year, following the rati cation of the agreement, the fourth year would come next year, in 2026-27. Concordia’s deputy spokesperson Julie Fortier, however, said the agreed timeline for conversion would be 2027-28, not 2026-27.

“ e agreement between the university and CUFA was that 2024-2025 would be year one of counting LTA positions toward a possible conversion to an ETA position, meaning that the eligibility for possible conversion would start three years later, in 20272028,” Fortier said in an email to e Link

Several faculty interviewed for this article said they were not aware of the information presented by Fortier before being questioned on it by e Link, and were under the impression that the conversion would take place next year.

Read the full feature online at thelinknewspaper.ca.

A small outdoor pantry in downtown Montreal seeks to help in a time of rising food and rent prices

Maria Paula Rojas Diaz

At the corner of Atwater and Lincoln Ave., a small wooden cabinet lled with canned goods, bread and toiletries stands as a symbol of solidarity.

e Atwater Community Pantry, a 24/7 outdoor food-sharing space, is helping Montrealers cope with the city’s rising cost of living, one jar at a time.

“It’s an outdoor space open to anyone, no matter their age or background,” said Juliana Saroop, a member of the Atwater Community Pantry team. “It’s really meant to be a sharing space where people can give and take whatever they need. We want to make sure there’s no stigma.”

e pantry rst appeared ve years ago as a student project proposal from Dawson College’s Green Earth Club. When the school didn’t approve their proposal, Saroop and a group of friends partnered with the Congregation of Notre Dame to host the pantry on its grounds.

“We were inspired by online mutual aid projects,” Saroop said. “We wanted something that re ected our values: community care, accessibility and ghting individualism.”

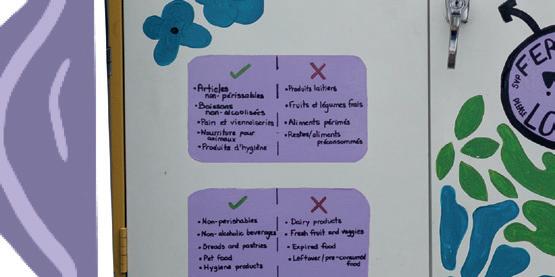

Today, the pantry is stocked with non-perishable food items, hygiene products and sometimes even pet food and spices. ey are small luxuries that can make a di erence, according to Saroop.

“We accept everything from canned food to soap,” Saroop said. “What we don’t take are expired goods or anything that might spoil in the winter.”

e project’s success re ects a growing need in Montreal. According to Statistics Canada, grocery prices have risen by more than 20 per cent in the last three years. Average rent for a

two-bedroom apartment in the city has climbed to over $1,900 a month, an increase of around 70 per cent since 2019. As a result, food insecurity has become more widespread.

“Food has become our second biggest expense,” said David Chapman, executive director of Resilience Montreal, an Indigenous-led community centre located near Cabot Square.

Like the Atwater Community Pantry, Resilience Montreal seeks to o er food supplies to the community.

"We spend about $50,000 a month on food, and that’s a er donations,” Chapman said. “Every month, more people show up

than the unhoused population.

“A lot of people we serve are recently housed or barely holding on to their apartments,” he said. “If your monthly check is $800 and rent costs the same, you’re le with nothing for food.”

For Magnolia Rodriguez, a recent immigrant from Mexico and a user of the Atwater Community Pantry, that project has made all the di erence.

asking for groceries.”

Still, Chapman explained that food insecurity a ects far more

Zach Jutras

“When I arrived in Montreal, everything was really hard,” Rodriguez said. “I have to pay for everything by myself: rent, food, clothes. Sometimes, when I don’t have enough for the month, I come here. It really helps me.”

Rodriguez added that she o en gives back when she can.

“When I have extra, I bring things too. It’s not just about taking, it’s about helping each other,” she said. “I think many people don’t know about it yet, but it’s really helpful for the whole community.”

According to Saroop, the response to the pantry has been overwhelmingly positive.

“We’ve had people reach out with stories about how it helped them through tough times,” Saroop said. “ ere’s a mom who visits with her daughter every week and takes pictures in front of it. It’s sweet. It shows how much this small project means to people.”

Montreal resident Melissa Li was in the driver’s seat.

Still, Saroop said that keeping the pantry running is not easy.

“Some of our partnerships have stopped donating, and many of us have moved away,” Saroop added. “We need more hands, more local businesses involved.”

In a city where prices keep climbing and resources are scarce, Saroop said that the Atwater Community Pantry stands as a reminder of what community care looks like.

It was a car ride between strangers. No money exchanged, just transportation and conversation.

“I was joking with my friends that it felt like I was a politician just listening to the complaints of the people,” Li said, a er driving a stranger to the hospital to help out during the most recent STM maintenance workers' strike.

When the month-long strike was announced in October, Li took to Facebook to o er free rides. In her post, she speci ed that she could o er rides to the elderly, people with low income or “folks with limited mobility” to the hospital, if needed.

Being a writer who works from home, Li said she felt she was in a position to help others out during this time of limited transit options.

“I'm happy to give someone a ride because I have the luxury of having a car,” she added. “I can't imagine people who can't afford to take Ubers everywhere and need to go to the hospital.”

According to Geneviève Paradis, spokesperson for the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux (CIUSSS) du Centre-Sud-de-l’Île-de-Montréal, some patients preferred to nd ways around getting to their medical appointments.

In an email statement to e Link, Paradis said the CIUSSS has not been able to link a connection to the STM strike and cancellations or no shows. “ at said, we have noticed that several users prefer to postpone scheduling appointments until a er the STM strike period,” said Paradis.

Meanwhile, paramedic Daniel Castillo said he has witnessed firsthand how residents improvised transportation during this time. ree weeks ago, during his shi , Castillo was dispatched to a senior who said she was feeling sick. e woman wanted the ambulance to bring her to the hospital, for what Castillo thought wasn’t an emergency.

“It’s a Band-Aid solution,” Saroop said, “but it’s a beautiful one. One that proves people are willing to look out for each other.”

How one volunteer stepped up to help vulnerable people during the STM strike

paratransit service could still access it during regular hours.

Yet when public transportation became less accessible, private transportation, such as Uber’s ride-hailing service, became more expensive as prices surged.

“I think it should be the opposite,” Li said. “In a time like this, people should be making it more accessible, not less accessible, so I de nitely don't believe in any Uber hikes.”

Li said she was encouraged to volunteer with an organization in Villeray that o ers free ride services to seniors year-round. However, she said the organization rejected her application because she doesn’t speak French.

e maintenance workers’ strike was suspended on Nov. 12, ending the scheduled month-long strike. e bus drivers’ strike that was scheduled for Nov. 15 and 16 was also cancelled; a strike that would have stopped service for two full days.

Still, even with the strikes having been suspended, Li said if she discovers an organization with a free carpooling service, she would look into signing up. that and

Li’s post blew up on the Facebook page “Montrealers Helping Montrealers,” garnering 386 likes and 67 replies. She said she received close to 10 direct messages, with some requesting help beyond what Li was willing to do.

Two requests, however, turned out to be perfect matches. One person with a disability needed a li to the hospital, and someone with low income needed one to a legal appointment.

e stranger she took to the hospital was a former New Yorker, like Li. ey chatted about old neighbourhoods and other New York-related topics during the drive.

According to Li, the person would have had to walk 75 minutes had it not been for the ride.

“ ey were really grateful that they didn't have to do that because it was raining that day as well,” Li said. “ ey were just really lovely.”

“She would get there by bus. She can’t afford a taxi, and an ambulance is free for those 65 and up,” Castillo said. “It makes sense [since] the ambulance is free. It's not the right resource, but there isn’t another resource.”

An ambulance is free in certain cases, such as for people receiving welfare benets and people older than 65 with a physician's approval. For those not exempt, an ambulance ride costs $125 plus $1.75 per kilometre.

During the maintenance workers’ union strike, STM service was limited to rush hour periods. However, those registered with the STM’s

Faculty and students say the university moved ahead with AI service

despite their concerns

Matthew Daldalian @mattdaldalian

AConcordiaUniversity student’s request for a human note-taker this fall semester has raised wider questions about privacy, academic freedom and university governance.

ird-year sociology honours student Gabrielle Place said she contacted the Access Centre for Students with Disabilities (ACSD) in August to ask for note-taking support. Instead of being assigned a student note-taker, she was told via email from the ACSD that the university would o er Genio, an AIbased service, if it “is something you think can work for you.”

While Place said she initially agreed to let ACSD contact her instructors for consent, every single one of them declined. e ACSD then informed her she could try negotiating directly with her instructors, but she chose not to.

“I didn’t want to create con ict between me and the professors,” Place said.

Place added that being pushed toward a so ware she viewed as “an unreasonable accommodation” felt out of step with a university already cutting resources elsewhere.

“I was basically told that they switched [from human note-taking] to using Genio,” Place said.

Concordia spokesperson Julie Fortier wrote in an email to e Link that the university “did not shi from human notetakers to Genio.”

“ ere is no plan to replace human notetakers and transcribers by AI so ware,” Fortier said.

Shortly a er a meeting with her ACSD advisor on Sept. 22, Place was eventually granted a human note-taker.

Genio Notes lets students record classes and generate transcripts and AI-produced outlines.

Among those following Genio’s attempted integration into Concordia is Christopher Hurl, an associate professor of sociology and anthropology, and one of Place’s instructors.

Hurl said his worries about the so ware surfaced well before this fall semester. Discussions surrounding Genio, he said, appeared repeatedly at the university’s Senate meetings and within the Concordia University Faculty Association (CUFA) and Arts and Science Federation of

Associations (ASFA).

bristle at the idea of being recorded. He described many professors as being “very conservative” about protecting their lectures and slides.

Place said part of her objection is that AI might not replace the judgment a seasoned note-taker brings to the table.

Marie Gravran, communications o cer for the Quebec Association for Equity and Inclusion in Postsecondary Education, said the association has heard “a lot” about there being note-taker shortages.

“It can take time. Sometimes, a student won’t get a note-taker until later in the session,” Gravran said.

At the same time, Gravran said technology must not be imposed against students’ objections.

“We don’t want that to be a one-size- ts-all solution,” Gravran said.

ere are currently 72 student employees providing accessibility services through the ACSD, according to Fortier, most working as note-takers or transcribers.

Fortier added that the centre “assesses on a continuous basis the various tools and supports it o ers, including Genio, to ensure it continues to meet the needs of the community.”

Student representatives say many of the same issues were debated at Concordia’s Senate meetings last winter and this fall.

“A question that we think is pretty pertinent is, how much did this cost to implement, especially in the time of austerity that Concordia has,” said Adam Semergian, academic coordinator for ASFA.

ASFA currently has no o cial stance on AI accommodations.

Semergian recalled that students and faculty had raised concerns about the so ware at Senate last year, and that many were surprised to learn it had been implemented over the summer despite those objections.

Anna She el, principal of the School of Community and Public A airs, described a “super contested” Senate meeting in early 2025, where faculty and students raised questions about recording classes for ASCD services.

She el said she believes classroom realities won’t always be compatible with the use of Genio. She explained that, contrary to a typical lecture, most of her courses are built around open discussion, which can make audio-based tools di cult to manage.

“It’s a misunderstanding of how classrooms work,” She el said.

She el added that she would be more comfortable recording classes herself, as it would allow her to pause recordings more easily if a student wanted to share something personal or sensitive.

Isabella Providenti, an undergraduate student who also serves as academic and advocacy coordinator for the Concordia Student Union, said she believes the university’s adoption of AI tools has unfolded with limited clarity.

Providenti described the broader policy environment as “a bit of a black box.” She noted that students can’t easily see how decisions about AI are made, what data agreements look like, or how these tools t into Concordia’s wider cost-cutting measures.

“On one hand, they’re being told in classes that they can’t use AI for schoolwork, and then on the other, it’s like they’re being given explicitly these tools that are using generative text,” Providenti said.

Place plans to keep her human note-taking support.

“At times like the widespread austerity measures,” Place said, “students and professors need to be working together.”

REM opens new Deux-Montagnes line

“My aim in the classroom is to establish an environment in which students feel comfortable sharing their thoughts,” Hurl said in an email to e Link. “I’m not convinced that their privacy will be protected with the

new so ware.”

Hurl said he’s uneasy about how the company might handle professors’ intellectual property and whether their lectures could end up training large

language models.

According to Fortier, Genio is approved strictly as a note-taking aid rather than a live transcription ment promising to stop recording when their

“I cannot violate that student's privacy and tell everybody they're being recorded,” She el said. “You can't really count on someone [to stop recording]. at's a pretty unreasonable burden to put on the student.”

tool. She noted that students must sign an agreepeers are speaking.

Gowrish Subramaniam, a second-year political science student who is legally blind, said he’s o en experienced instructors

A new Montreal Réseau express métropolitain (REM) branch was opened to the public on Nov. 14 connecting downtown Montreal to the Deux-Montagnes municipality. According to CBC News Montreal, the line is expected to transport over 40,000 people daily during morning rush hour alone. Two additional REM branches, connecting downtown Montreal to Anse-à-l'Orme and the Montreal Trudeau airport, are expected to be completed by 2027.

The festival’s 46th edition highlights Montreal talent through Audet’s reflective, narrative performance

Andréas Fleury

The 46th edition of the Montreal International Jazz Festival kicks o June 25, 2026, with a programming choice that speaks volumes about the festival's commitment to showcasing Quebec talent.

Since its founding in 1980, the festival has become the world's largest jazz event, known for balancing international and homegrown talents. Modibo Keita, part of the festival’s programming team, says the goal is to “re ect the diversity of the metropolis while honouring the pillars of jazz tradition.”

He emphasizes the festival’s mandate to connect with generations of artists.

" e most important thing for a festival is to serve as a meeting place between established artists and those who are still developing,” Keita says.

He adds that having world-class talent gathered in Montreal is a “real gi ” for its audiences and artists. is year, composer and pianist Viviane Audet embodies that commitment to local artistry. Set to perform her album Le piano et le torrent at the Gesù theatre on opening night, Audet o ers festivalgoers a glimpse of the reasons behind her selection to lead the 2026 edition: a strong performance that blends instrumental composition and narrative storytelling.

" ere are people who don't know me, but because of the jazz festival's presence, they'll come out of curiosity," Audet says. "So, in terms of discoverability, it's really something quite special.”

For years, Audet took a winding path to this moment. Before focusing on her own personal projects, she composed for others. Her work on the Polytechnique documentary sparked a new creative direction, leading to projects such as Les lles montagnes and later Les nuits avancent comme des camions blindés sur les lles, two albums charged with feminist activism.

When she began focusing on her own projects, she found herself exploring more intimate, re ective ter-

rain and turning storytelling and music into a process of growth and healing.

"It's the thing I created that changed my path, the reason I now have the chance to be on a jazz festival stage," she re ects. e 15-track instrumental album was born during a period of personal turmoil and composed through disciplined daily writing. But Audent insists the project is more than music.

than just another booking for Audet. It o ers both validation and community.

“Le piano et le torrent is a show where the music obviously plays a major role. But what also takes centre stage is the storytelling,” Audet explains. “It’s what I share between the pieces, the narrative thread that unfolds as the performance progresses.”

"Seeing that programmers trust us gives me a real boost. It really builds my con dence,” Audet says. “[...] When you go to see other shows, you can meet people and make connections.”

Maryse Dubé, Audet's project manager, witnessed this evolution rsthand and recognized the signi cance of the album early on.

Audet’s opening-night performance cements the Montreal International Jazz Festival’s role as a stage where local stories find global resonance.

"When I saw her album, I told her, ‘Viviane, torrent is your breakthrough album,'” Dubé says. “I already knew her [work], but this album is truly a stepping stone.”

Audet's theatrical approach comes naturally. Originally dreaming of becoming an actress, she honed her sensibility through years of composing for lm and documentaries.

"I wanted to be an actress," Audet recalls, noting audiences’ surprise at the theatrical aspect of her shows.

Le piano et le really

"I'd say 99 per cent of people wouldn't expect this," she adds. " ere's a theatrical dimension to the show that really catches you o guard."

Audet's approach to instrumental music challenges common practices. Her attention to track titles and themes of displacement invites audiences to map out their own experiences.

“I want people to experience the show as an immersion,” Audet says. She emphasizes that audiences are free to engage with it however they wish. Listeners o en share deeply personal responses, writing to tell her they play her music during surgeries, births or sleepless nights.

“People have an astonishingly intimate connection with instrumental music,” Audet says. “I never would have imagined that.” is response has given her work new meaning. Even though the show has only been performed once so far, preparing and presenting it has already become part of her healing process.

Released on Jan. 31, 2025, Le piano et le torrent marks a turning point in Audet's career, which she describes as her milestone.

“I found peace that night,” Audet says. “It has helped me mourn this torrent and to look at it with more gentleness.”

Used to collaboration, she describes this album as a moment of intimate self-re ection.

"I love working with people. I'm not solitary at all,” Audet says. “ at's why Le piano et le torrent was so surprising, it was the rst time I found myself completely alone.”

Audet fell in love with the Gesù theatre during her September 2025 show at the venue. She praised the acoustic intimacy of the 425-seat venue, one of Montreal’s oldest performance spaces.

"In my jazz festival concert, I want that same sense of sonic closeness to come through," Audet says.

Being selected for the jazz festival represents more

Ryan Pyke @pykenotpike

Concordia University is home to many talented musicians and ways to get involved in the music scene. e community represents more than just a collection of artists; it is a network of spaces, student collectives, programs and collaborations that bleed into Montreal’s creative fabric.

Whether you’re looking to perform yourself or just discover new sounds, Concordia’s network of musicians makes it easy to plug in.

Shae Powell, known musically as shaedolla, is an electroacoustics major who’s deeply connected to the scene. She runs Stereo Field Trip, a radio show that airs on CJLO, Concordia’s community radio, where listeners can discover local and underground artists.

“I get people to send me their music and I end up learning a lot about who’s making what in the city,” she said. CJLO makes it easy to get familiar with the scene. Anyone can tune in or volunteer to learn broadcasting, sound production and live recording. Volunteers can even rent the station’s studio at a discounted rate, making it a very accessible place for new musicians to be heard.

Powell, once involved in Montreal’s punk scene herself, now leans toward folk. While getting started in the music world didn’t come easy, she found that talking to other people involved was a simple and e ective way to kickstart her career. She also recalled a friend who got gigs by walking into bars and cafés along Ste. Catherine St. and asking if they needed music.

“If you do end up performing at a venue, stay there,” Powell said. “Don’t leave a er your set, stay and hear what the other people are making, tell them they did a good job, get the pat on the back.”

For Powell, that sense of community is what keeps the music scene alive. It’s more than just performing, but about showing up for others and sharing the same spaces.

Mai/son and Lamp House are both house venues where students can play or listen, with Lamp House being run by a

Concordia alumnus. ese o er a much more intimate environment for students to nd their footing. Powell pointed to it as the perfect place for beginners who want to perform without the pressure of large crowds.

at same spirit extends beyond venues. e Concordia Electroacoustics Studies Student Association also provides compilation albums of student work, o ering another way to discover what’s being created on campus.

Powell’s biggest piece of advice for those just starting out is simple: show up and stay connected.

“Meet musicians, follow them, they will post their posters,” Powell said, “and then go to their shows and stick around because that’s how you enter the scene.”

Aria Tessler, an electroacoustics major and DJ, has also found her rhythm between Concordia and Montreal’s nightlife. She o en collaborates as much with peers at the university as with artists from outside it.

Like Powell, Tessler sees Concordia as a starting point where students can make connections with fellow artists who can help them get going locally.

“I think a lot of people take what they’re doing at Concordia and they take it a bit elsewhere and involve themselves more generally with parts of the music scene in Montreal,” Tessler said.

On campus, that sense of community is visible almost everywhere.

e eighth oor of the John Molson School of Business is occupied by music students. It’s covered in posters for open mics, jam sessions and student shows. ese posters o en include call-outs for musicians, giving newcomers another easy entry point.

“ ose always have kind of up-to-date things going on,” Tessler said.

Powell mentioned a music club run by a residence advisor at Grey Nuns Residence, which she discovered through one of these posters. e club allowed students

to showcase their original work and perform with other musicians during their end-of-year show.

“ e best way to get involved is to just get involved with the community,” Tessler said, echoing Powell’s sentiment. It is impossible to separate Concordia’s music scene from the vibrant broader scene in Montreal. e university’s music community remains open to those who do not attend the school.

Delphine Vise and Iris Lou Dune, part of a musical duo known as 17sport, represent one example. eir project made an appearance on Powell’s show, bridging Concordia’s network with Montreal’s.

“CJLO is just a very accessible place, I nd,” Dune said. “It’s just a really nice way to nd new music and new artists from Montreal and Concordia.”

For them, Powell’s show provided a way to get their music heard.

e duo, only recently becoming musicians, has performed at Concordia events like the Concordia Fashion Business Association’s showcase, as well as collaborated with students to lm music videos using the university’s green-screen facilities.

“ e art scene in Montreal is Concordia,” Vise said.

Dune agreed, but amended that this applied mostly in the case of young people.

She pointed to the intermedia program at the university, which blends sounds, video and performance.

“It’s fun that, in this school, there’s literally a program that does that,” Dune said.

For those looking to get their foot in the door, Vise and Dune agreed with Powell and Tessler, emphasizing sending emails, DMing on Instagram, and following artists as the best ways to get started. ey stressed that other musicians generally welcome newcomers.

“Everyone wants to upli everyone,” Vise said.

For students hoping to start performing, Concordia’s scene proves that all it really takes is curiosity, community and the courage to show up.

Where Vietnamese tradition meets experimentation, and goes viral along the way

Safa Hachi @safahachi

OnBishop St., just steps away from Concordia University’s downtown library, is a small sandwich counter quietly carving out its place in the city’s food scene. Hidden inside Kaizen Manga Café, Bánh Mì Cu Lắc, nicknamed “Culac,” doesn’t stand out much from the street. Unless you’ve already seen it online.

Scroll through TikTok or Instagram, and you’ll nd Wendy Tran, the owner, speaking directly to the camera as she assembles sandwiches that mix Vietnamese roots with unexpected twists.

For Tran, Culac isn’t just a business but also a creative outlet.

“The name Culac actually comes from my brother,” Tran says. “In my family, all the boys’ nicknames start with ‘Cu.’ His name is Culac. ‘Lac’ means shaking. He just has so much energy, he would run around and ask questions, be very curious and very adventurous, and that's kind of the energy that I want to bring to this brand.” at same energy extends beyond the food. When Tran’s friend Linh Tran suggested sharing her experiments online, the project took on a new life.

Testing the algorithm

Culac’s online presence is run with help from Linh Tran, a Concordia marketing graduate and longtime friend. Linh, who now works as a marketing analyst, started freelancing for Vietnamese-owned small businesses to stay connected to her culture.

When Linh rst suggested TikTok, Tran wasn’t convinced.

“For the longest time, I didn’t have the password to that account, because they would come shoot and edit and post,” Tran recalls with a laugh. “I’m just like, do your thing. I don’t think this is going to work. I’m skeptical. And they just kept doing what they thought would work.”

eir rst playful video, lmed with friends at Kaizen Manga Café, picked up tens of thousands of views and brought new people through the door.

“Whenever a TikTok video of mine went viral, it was like the next day, a bunch of people would come in. It’s very instantaneous,” Tran says.

Finding a voice online

Linh describes Culac’s online presence as playful but genuine. She helps shape the brand’s voice, managing content ideas and posting plans while Tran runs the kitchen.

“I think she has a very clear mindset and image of the brand, which is great for marketing, because you don't have to create that from scratch,” Linh says. “I just add elements I

think would be funny or experimental.”

e result is a mix of humour and honesty that mirrors the restaurant’s approach to food itself. eir videos range from lighthearted skits about daily life at the counter to re ections on what it means to run a small business, and even quiet moments where Tran simply talks about food and creativity.

What stands out to Linh the most is how audiences connect to that authenticity.

“I noticed that when we started to be more personal and share the real story, people also started to like that," Linh says.

Each post feels like an extension of Tran’s personality: experimental, yet grounded in care. For a newly opened spot like Culac, that connection has made a di erence.

“It’s de nitely helped people nd us,” Tran says.

Community in every bite at connection goes beyond the screen. Ruby Challita, a regular customer, rst met Tran during her early pop-ups at Kaizen Manga Café.

“I’m a regular member of Kaizen’s community, and even used to be their community manager at one point,” Challita says. “I got to meet Wendy while she was still setting up the kitchen space and got to see her make her rst bánh mìs.”

Challita still stops by regularly for her favourites: the miso chicken and the bò lá lốt sandwich.

“ e avours are amazing,” Challita says. “I genuinely did not expect that a [bánh mì] place could have such new avours incorporated into their foods.”

She’s also watched the restaurant’s online following grow rsthand.

“I am super proud seeing how Culac has gotten a lot of recognition, especially on TikTok,” Challita says. “I see how much e ort Wendy and her [marketing] manager put into outreach through online exposure.”

Doing things right

Culac’s small menu re ects Tran’s perfectionism.

“I would lose sleep over the fact that a product doesn't leave the store the way that I want it to,” Tran says. “I want people to taste like how I tested it, how I make it and how it's supposed to be.”

Tran hones her culinary skills down to the ner points, such as never using refrigerated bread.

“At Culac, we focus very much on taste,” Tran says. “So if

it's not the right temperature, if it's not the right texture, we will try our best to correct that, so that people have the best experience possible.”

at level of care doesn’t come without sacri ce, and Tran admits the work can be relentless. Running a restaurant means trading creative hours for long prep sessions, supplier calls and kitchen shi s. Still, she doesn’t mind.

“I live my life when I can,” Tran says, “and I'm so happy doing this that I don't feel like I'm at work.”

When disruptions happen, like the recent STM strikes, Tran leans on her community. She says regulars still showed up, and online orders increased as people tried to support the business from home.

Moments like those, Tran says, remind her why she started. Seeing familiar faces return week a er week is its own kind of reward. For her, success isn’t measured in numbers, but in consistency and care.

“Obviously, growth is great, but if I can pay my bills, if my sta can go home to a roof over their head, then I think we're doing our job,” Tran says.

Playing the long game

After a year of pop-ups and six months in a physical space, Tran isn’t rushing growth. She’s focused on refining her craft and building a foundation strong enough to last.

“For the next few years, [I’d like to] have my own space, have my own dining room, have basically the entire experience being the Culac experience,” she says. “We’ll see how it goes. We’re still new, we’re still learning.” at patient mindset doesn’t mean she lacks ambition. Tran dreams of expansion but wants it to happen organically, on her own terms.

As she puts it, with a laugh, “In the far, far, far future, we want to make it big. Many stores.”

For Linh, the journey already represents something bigger. She sees Culac’s growth as a way to broaden how Vietnamese creativity is seen in Montreal.

“What I want is for more people to see Vietnamese culture,” Linh says. “We’re young people experimenting, trying to show that it can be so much more.”

And for Wendy Tran and Bánh Mì Cu Lắc, that seems to be the point.

Not all fee levies are created equal Concordia Recreation and Athletics’ failure to secure a fee levy increase displays a disconnect between students and their democracy

For the second year in a row, Concordia University’s Recreation and Athletics (RA) will not receive an increase to its fee levy. A er a Fall 2024 vote failed to pass, students voted against the same campaign again during the Fall 2025 Concordia Student Union (CSU) by-elections.

e current fee levy sits at $2.92 per credit, unchanged since 2009, and represents around 40 per cent of the department's revenue. But as enrolment decreases and course loads drop, RA revenue decreases too.

“As those numbers have also been going down, it's been a challenge,” RA director D’Arcy Ryan said. “Our fee levy compared to similar institutions in Quebec universities is much lower.”

Funds from the fee levy help support student jobs at the athletics complex and the maintenance of intramural sports. It also goes towards gym equipment and activities at the university’s two campus tness centers.

CSU nance coordinator Ryan Assaker said that students may not have fully understood the RA’s movement. e group faces an additional hurdle to its status as an administration-run organization rather than a CSU-a liated group, he explained.

Assaker noted the di erence in perception when students see CSU groups on the ballot as opposed to Concordia ones.

tion services at e People’s Potato throughout the campaign period. According to Assaker, the fee levy groups that failed in the vote did not have the CFC’s level of student outreach.

“Speci cally for administrative-run services, they're not able to reach the students that are going to vote there,” Assaker said. “ ey need to be very acutely aware that these students need to be talked to.”

During its campaign, RA tried to launch a student-based outreach program. ey created a dedicated fee-levy-increase account on Instagram to appeal to screen-loving students.

“You constantly see students scrolling on either TikTok or Reels,” RA director Ryan said. “We're hoping we're speaking their language. We're on a platform that they're going to see and recognize.”

But when it comes to student democracy, Assaker acknowledged the high probability of fee levy failures and groups like RA lacking the necessary support.

“ e CSU fee levies usually come across as something that has the purpose of funding student-run initiatives,” Assaker said. “[...] When they go to the ballot, I think that also is something that contributes to their vote, to their decision making.”

Concordia women’s hockey head coach Julie Chu lamented a lower voter turnout, but also praised student-athletes and community members for spreading the word.

“It's hard because participation in voting is low in general,” Chu said. “I think that the more we can get out in our communities and let people know, I think that's the better o that we can be, but it's always a tough part of it.”

Assaker emphasized the importance of grassroots movements to drum up support for an upcoming vote.

He referred to the Concordia Food Coalition (CFC), which passed its fee levy increase during the same vote, as an example, describing its e ective promo-

more e ective. He placed partial responsibility on the shoulders of the union regarding e orts to support student democracy around Concordia.

“We have the comms department, we put out reels on our Instagram account and all of that, but it needs improvement across the board in terms of that,” Assaker said.

For Chu, the votes represent missed opportunities for students to strengthen their communities. She urged students to take the time to understand what each fee levy supports.

“I think the knowledge of some of those additional fees, although the impact on each person is fairly low, I don't think they understand the impact of the resources that they can gain from it,” Chu said.

But for now, RA will have to wait.

With les from Aylee Ahmadzadeh.

“We want to encourage them to get a fee levy,” Assaker said, “but we have to be realistic with them.”

Even within the CSU, Assaker believes student outreach could be

The Professional Women's Hockey League has announced the team names and logos for its

Aylee Ahmadzadeh

Samuel Kayll @sdubk24 @ayleezadeh

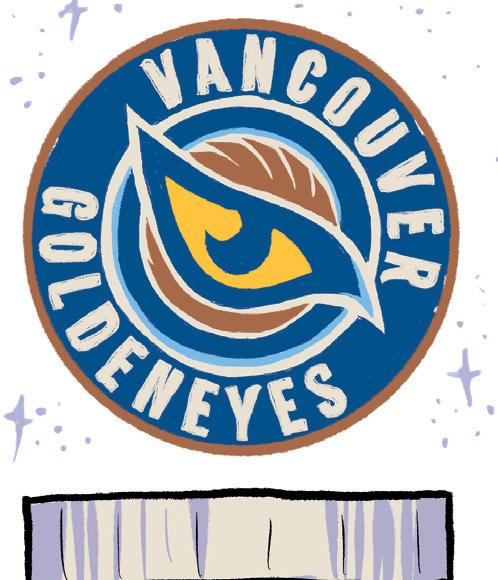

The Professional Women's Hockey League (PWHL) has unveiled nature-inspired branding for the league's new west coast additions, the Seattle Torrent and the Vancouver Goldeneyes. Vancouver and Seattle’s new identities in the PWHL go beyond aesthetics; they carry deep meaning. Between the Goldeneyes’ wildlife symbolism and the Torrent’s aquatic imagery, the PWHL has delivered branding that balances creativity with strong regional identity.

"In both Vancouver and Seattle, nature is such an incredible

presence," said Kanan Bhatt-Shah, PWHL VP of brand and marketing, in a press conference unveiling the branding. "Everywhere you look, all around you, it plays such a huge role in everyone's life, and that was something that we wanted to make sure we captured."

e Goldeneyes’ name stems from the goldeneye duck, a species found around the coastlines of Vancouver and much of British Columbia. e logo highlights a sharp golden eye surrounded by a wing angled upwards, pointing toward the Paci c

Northwest. Its colour palette features Paci c blue, coastal cream and earthy bronze, with hints of sunset gold and sky blue, the team’s primary colours.

e Torrent nickname and S-shaped logo, with the word “Torrent” written across, re ect the powerful rivers and waterways of Washington. ese natural features are central to the state’s identity. It is accompanied by its colour palette of foam, haze grey and basalt black.

Hilary Knight, the rst captain in Seattle Torrent history, expressed her excitement to unveil the logo and identity to family and friends.

“Whenever you’re looking at the culture of a group, you want it to be a really strong room,” Knight said, “and to pair that with an incredible city with a storied sports legacy and a brand-new identity that speaks to all of that, it’s a great recipe for us.”

Branding and logos in sports bring identity to a team. Jennifer Gardiner, who was born and raised in Vancouver, re ected on the personality and representation behind the Goldeneyes logo.

“ is identity is a perfect re ection of who we are and where we come from,” Gardiner said. “When I think of the Goldeneyes, I think of the landscape of British Columbia, the mountains, the ocean, and the grit that comes with growing up here.”

Creativity and branding in sports logos have grown beyond mascots and classic crests, especially in women’s hockey. Today’s designs lean

into storytelling, symbolism, and regional elements to re ect a team’s identity beyond just its name.

Instead of relying on standard logo designs, teams use local artists and storytellers to blend local culture, geography and emotion into a team identity. The result: a new era of logos that are more expressive, meaningful and memorable, built to resonate with fans not only in jerseys but off the ice as well.

While merchandise featuring the new designs is available for sale, the new branding and logos will not be used on team jerseys for the 2025-26 season. Instead, teams will have jerseys with their city name.

e decision stems from the branding not being nalized in time for the PWHL to place jersey orders, as trademark checks and legal requirements can delay the process.

e PWHL’s third season o cially starts on Nov. 21 with a doubleheader.

e Toronto Sceptres will take on the Minnesota Frost at Grand Casino Arena in Saint Paul, Minnesota, at 6:00 p.m. CST. en, the Vancouver Goldeneyes and Seattle Torrent will go headto-head at Paci c Coliseum in Vancouver at 7:00 p.m. PST, kicking o what promises to be a heated West Coast rivalry.

Jayde Lazier

Many have heard about the recent gambling scandal involving Portland Trail Blazers coach Chauncey Billups, Miami Heat guard Terry Rozier, and former Cleveland Cavaliers player-turned-assistant coach Damon Jones.

But for those who haven’t, the three men were recently arrested in gambling investigations involving illegal sports betting and rigged poker games backed by the American Ma a. is current scandal is unfortunately just one of many gambling-related issues plaguing the NBA. It highlights a larger issue within the league: gambling has become deeply embedded in the fan experience through the numerous NBA partnerships with betting companies.

Many people argue that the league prioritizesnancial gain over the safety of its image and players. Some may contest this, responding with the claim that the NBA places warnings on its advertisements. at’s true; with a couple magnifying glasses over each other, viewers can see that warning loud and clear. ese legal disclaimers are small and practically invisible compared to the onslaught of ashy, in-yourface gambling ads. For example, an ad recently released in collaboration with the NBA and Dra Kings featured Shaquille O’Neal surrounded by bright green colours, ashy bolded text. en in the corner underneath it all, a small legal disclaimer.

During games, we consistently see logos or in-game prompts on screen that normalize sports gambling. For heavily invested sports fans, especially younger ones, it can make it very challenging not to fall prey to this temptation.

Critics have been avidly raising concerns that this intensive advertising could be in uencing young people to gamble or bet when they don’t fully grasp the risks involved.

e NBA has indeed participated in some responsible gambling campaigns with the American Gaming Association, like “Have a Game Plan. Bet Responsibly” or “Never Know What’s Next,” which aims to educate fans about the risks involved with betting.

However, these isolated e orts are not enough. Responsible messaging should be embedded into every campaign, not treated as a side project.

ere also needs to be a reduction in the amount of advertising and sponsorship that endorses gambling and betting that we see. While understanding that it will never disappear en-

tirely, there need to be safer ways to get involved. Teams can invest in responsible gambling programs for the fans and increase their players’ education and overall protection.

e NBA needs to implement better programs to inform players and coaches not just about the legal repercussions of betting and gambling but also about the mental and emotional toll it can take.

To restore the league's integrity and rebuild fan trust, the NBA needs to move beyond damage control. How many times can this issue just be swept under the rug before the rug starts to li from the oor?

Players’ poor actions are re ecting badly on the association, and the lack of accountability tells fans that this is normal and,

therefore, OK. e NBA needs to stop issuing meaningless press statements a er players or coaches are arrested for illegal gambling, betting, or other similar issues. It should be creating an environment where it can get in front of these issues before they happen. Educate. Support. Implement. Don’t just put a Band-Aid over the gaping wound that is betting and gambling in major league sports. Start asking why players and coaches feel that it’s acceptable to revert to these illegal acts. Ask the associates within the company why they aren’t taking proactive measures to combat these issues, and ask yourself: why aren’t we holding the NBA accountable?

we eat

Once a niche bodybuilding supplement, protein powder has become a billion-dollar health trend

Alex Merchant, 21, has trained at the gym for several years. He says he began taking supplements two years a er starting to workout regularly, and that in uencers promoting these products with visible success convinced him to give them a try.

Realizing that his body no longer bene ted from the expensive additives, he recently cut out all supplements from his gym routine that focused on bulking.

For Merchant, the initial interest in adding protein supplements to his diet stemmed from watching in uencers share their tness routine and meals online.

“I think they do kind of push the diet side a lot as well with the workout, and many of them have their own supplement partnerships,” Merchant said, adding that in turn, these partnerships support these creators.

“Seeing the progress between each video is sort of evidence that their products work,” he said.

e number of food and beverage products marketed as being high-protein has quadrupled between 2013 and 2024, according to market research rm Mintel. In uencers, supplement brands, and tness podcasts have turned protein into a symbol of health and productivity. Consumer demand is high, with the American alternative protein market already valued at US$7 billion in 2024 and projected to grow 13.5 per cent by 2030.

According to Montreal-based registered dietitian Olivia Carone, many adults she works with look to improve their relationship with food, and some use protein powders to assist with that.

“In terms of the trend and interest, I feel like it’s changed,” Carone said. “It's not just people who are going to the gym and looking to gain muscle.”

Low-calorie, high-protein products and supplements have taken over the Canadian packaged food landscape. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada reported that products in Canada with high protein content comprised C$1.3 billion of total packaged food sales in 2022.

How much is too much?

Nutritionists agree that the amount of protein you need depends on your body weight and age more than anything, but recommend about 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight per day.

For an adult weighing 68 kg, that's about 54 grams of protein. is amount of protein can be found in a large chicken breast or eight eggs, a quantity that most adults can consume in a standard, balanced diet. Carone said that most people do easily get enough without altering their diet, unless they have a lower appetite.

Dr. Susan Woolhouse, a Toronto-based physician, said that some groups of people bene t from protein supplements, such as very active or competitive athletes, older adults and people recovering from illness.

“All these groups might nd it hard to get enough protein from their diet,” Woolhouse said, “[but] most people are able to get the recommended amount from a well-balanced diet.”

If increasing protein with an extra steak or hard-boiled egg is not an option, taking a supplement can be effective and convenient.

To enhance the muscle growth that typically occurs with exercise, evidence supports consuming 20 to 40 grams of protein immediately before or a er exercise. Any more than that can reduce muscle-building potential.

In uencing the market

For high-performance athletes and those focused on muscle gain, research has shown that adding protein to your diet in quantities greater than recommended may be bene cial, but there is not enough evidence to support de nitive conclusions.

Since the 2010s, in uencers have marketed protein as the key to tness, longevity and energy, a “one-stop shop” nutrient that promises a near-universal solution to good health.

One of those gures is Alex Clark, a podcast host associated with conservative nonpro t Turning Point USA and a leader in the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

Figures like Clark have merged wellness with conservative culture, Clark herself having amassed millions of views across social media. She promotes slogans like “Less Prozac, more protein” to frame high-protein diets as both a lifestyle and a moral stance.

to muscle maintenance, metabolism and longevity. His podcast, Huberman Lab, has over seven million subscribers on YouTube, where he discusses health and wellness tools.

Huberman recommends up to 2.7 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, almost 200 per cent more than the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends. Huberman attributes protein in the diet directly to living longer.

Carone also links adequate protein to better long-term health.

“It helps you with strength and especially, through aging, you’re likely to be able to do more,” Carone said. “You have more strength on you, which does help with longevity.”

Still, Carone said she thinks the focus on protein powders as a “cure-all” is “a little overexaggerated.”

“Protein powder could be an option and would help you with energy levels,” Carone said. “It would help you with muscle mass and make sure you're not losing it, especially through aging. But you can get that protein through [regular] food.”

Woolhouse echoed a similar sentiment to Carone.

“I think we have to be careful of fads,” Woolhouse said. “Put on your critical thinking cap when reading advice about any health intervention, especially if someone is trying to sell you something.” e cost of maxing one, minimizing the other

As protein-rich supplements, shakes and forti ed snacks gain traction, experts warn that other nutrients, like bre, can become neglected.

“A client who's asking me how to get enough protein, generally a supplement isn't my rst recommendation.” Carone said. She added that natural sources of protein from plant or animal products o er other bene ts like bre, iron and magnesium that aren't necessarily in protein powders, which make them a more balanced option.

Meanwhile, since Merchant stopped taking protein supplements, he said he believes his general health has gotten better.

Meanwhile, CrossFit culture and tness YouTubers have helped to normalize protein tracking as a daily ritual for strength and self-discipline.

Popular podcasters and wellness gures such as neuroscientist Andrew Huberman routinely emphasize protein as essential

“People just end up using them to replace meals instead of supplementing, which is something that is probably pushed online too much,” Merchant said. “I don’t think I’ve ever drank a protein shake and not felt a bit sick a erwards. I think my body appreciates real meat and vege-

Reza Taher-Kermani

Alarge portion of the teaching at Concordia University is done by part-time instructors and by faculty appointed on shortterm contracts, positions that are provisional, contingent and subject to periodic approval.

I am one of those faculty members. My position is called a limited-term appointment (LTA), which means that my contract lasts only a year.

Each spring, I must reapply for the job I am already doing: a new application letter, a new teaching dossier, new uncertainty. In the last two years, I was interviewed for the job afresh and asked to provide new reference letters, as though my ongoing work here could not, in itself, speak to what I o er. is year, I was asked to provide a teaching demo too, as though four years of teaching in these classrooms were not already part of the record the university keeps. Each renewal allows me to continue my work here, but also reminds me that I may not be allowed to remain. It is a painfully uncertain place to be.

On Oct. 30 , that uncertainty ended. e university announced that it would not be issuing renewal calls for LTA positions. e announcement was brief, framed as an administrative adjustment in response to budgetary constraints. But the e ect was immediate: our jobs will no longer exist next year, and with them goes not only a category of employment but also a lived continuity of teaching, mentorship and care.

What makes the decision particularly dispiriting is that it forecloses the only pathway we had toward anything less precarious. A er years of the university’s reliance on annual contracts for meeting essential teaching needs, the new collective agreement nally introduced a route toward some form of stability: LTA positions allocated to the same teaching need for four consecutive years would be eligible for conversion to extended-term appointments, as long as the department deemed the position necessary. at conversion is now impossible (even though my position in nineteenth-century British literature has met that same need, consistently, for well over a decade). By terminating these positions now, the university eliminates our jobs but also resets the clock to zero. Whoever lls these posts next will have to begin the entire count anew.

preparing lectures, meeting you during o ce hours, marking your essays, writing letters to support your applications, revising course materials, all the while continuing with our research, publishing articles and working on books that develop slowly over time. We do all of this under contracts that expire annually, under conditions that fragment our focus and drain energy from the very work we are meant to do.

At Concordia, those of us in these roles teach seven courses per year (tenured and tenure-track faculty teach four or fewer), and we do so with minimal teaching assistance, little research funds, and salaries that re ect our contingency more than our contribution. at is, however, not unusual these days: across Canada, universities increasingly rely on short-term instructors whose positions cost less to maintain than permanent faculty lines to keep their programs running.

But the human cost of this model is real: it prevents people from building stable lives. When your employment is renewed one year at a time, you cannot make long-term plans; you cannot put down roots; you cannot build a life beyond the next contract. You have to live with the knowledge that one day you may simply not be renewed, with no explanation or recourse.

diction, one that cuts to the heart of academic life: these roles make it nearly impossible to do the research on which our future in the academy depends. e instability built into these positions, not to mention their heavy workload, erodes the very conditions that make scholarly and creative work possible: the ability to think with depth, to write with patience, to develop research that unfolds over years rather than weeks.

Research, the work that generates new ideas and keeps teaching alive, requires time, continuity and a sense of the future, and precarity removes all three. Universities ask us to publish, to innovate, to bring intellectual energy into the classroom, while structuring our employment in ways that obstruct these pursuits. is is not, in the end, only about our contracts; it is about the conditions under which learning takes place, because what happens to contingent faculty will shape the kind of university you, the students, inherit, because the values that govern one side of the classroom ultimately nd their way to the other too, because when the people who teach you are treated as provisional, the education you receive is treated as provisional.

What this means, on the ground, is that the continuity of your education is interrupted. e teachers who learn your work, who follow your development across courses and years, who become the people you turn to for guidance or support, may simply no longer be here. Degrees are not just collections of classes; they depend on relationships built over time. When the university makes those relationships impossible to keep, something essential in the learning environment is lost, not only for us, but for you.

A university is not only an institution; it is a place where lives take shape over time, yours and ours, and the decisions being made now will determine what kind of place this will be.

A university can choose to treat teaching as temporary work, to cycle through those who do it, to make knowledge something delivered in passing. Or it can choose to understand teaching as a form of commitment, continuity and care, something that takes root and grows through sustained presence.

Many of you may not know that the people teaching your courses are not all employed under the same conditions, that some of us do the same work as colleagues in ongoing positions:

The irony is that these jobs have been largely offered to those the university claims to want most to include: women, Indigenous scholars, racialized faculty—people whose presence can be held up as evidence of progress. Yet we are hired into conditions that make growth impossible. Precarity leaves no ground on which to build a career, no security from which to speak, no promise that the work we do will ever count toward a future. We are welcomed as proof of change, but never allowed to belong to the institution that displays us. is is, in many ways, a role de ned by contradiction: one in which we are relied upon for the continuity and daily life of teaching while being structurally prevented from having a say in the university’s present or a place in its future; one in which we are expected to meet full professional standards as teachers, scholars and mentors, but are evaluated repeatedly as though our competence itself remains in question; one in which we are responsible for guiding students through degrees in which we ourselves are not permitted to have a stable place. We carry out a signi cant part of the everyday work on which the university depends, yet the terms of that work ensure that we remain permanently temporary—necessary but never allowed to stay.

I would like to believe the latter is still possible here. I would like to believe that the university remembers that its strength lies not only in the programs it o ers, but in the people who carry those programs forward, year a er year, in conversation with students whose names we remember and whose paths we follow.

Beyond these institutional exclusions lies another contra-

Whether I am here next year or not, that is the university I have tried to help build.

Jaiden Gales

Ihave always been “chalant” and I will proudly always be “chalant.”

In a society hellbent on downplaying excitement so that we don’t look cringe, isolation and social disconnection reign. We pretend we’re not hurt so that we don’t seem dramatic. We act like we’re indi erent to things that actually mean the world to us.

For what? To seem unbothered? To protect ourselves?

A quick TL;DR for those who don't know: nonchalant is de ned as “having an air of easy unconcern or indi erence,” according to Webster’s Dictionary, and has recently taken over the internet, inspiring Gen Z in particular to lean into nonchalantism.

Of course, this disconnection is massively ampli ed by an increased use in personal tech gadgets such as phones, tablets and computers, and in the age of social media, it’s easier than ever to cancel, ghost or disappear. is trend reads as a result of constant bombardment by information in the digital age. Every single one of us is overloaded with new headlines, unanswered emails and the pressure to post every day. Nonchalantism is the new generation’s defence mechanism.

Mark Manson’s e Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck gained popularity in recent years and is an absolute eyesore. In his book, Manson o ers repetitive life advice under the guise of 2010s ironic epic bro humour, encouraging people to detach themselves emotionally to get ahead in life and nd "peace."

e result? A whole wave of apathetic and disengaged

nance bros with the emotional maturity of a peanut.

Not to say that being nonchalant is never warranted, but it’s been taken to the extreme thanks to social media. We have leaned too far into not caring. According to the internet, the optimal way to present now is to be detached and “chill,” whatever that means.

Ugly, bitter and raw feelings deserve to be felt, and no one, especially impressionable youth online, should feel pressured to maintain an air of nonchalance at all times. at’s absolutely ridiculous. To be nonchalant is to deprive yourself of all the beautiful ups and downs of a life lived to the fullest.

Emotions deserve to be felt, no matter the calibre.

Sometimes you have to show up when you’re not at your best, or even the opposite; maybe you just got the happiest news of your life, and you're bursting at the seams with joy. ose feelings should not be bottled inside; we all deserve to share ourselves authentically with the world.

Yet, we have collectively agreed to make e ort our enemy without realizing that human connection is about give and take. We need each other. And that requires being open and vulnerable, not hiding your emotions away so you look “cool.”

So, is there hope for Gen Z?

ere is another idea oating around the internet lately that needs to be ampli ed, a reminder to a generation risking an isolated existence: community is built through inconvenience. Real connection is created through mutual e ort and sacri ce, in other words, when we do things we may not want to do to support those we love.

As one Reddit user shares, “Building community means doing things that aren’t always easy, such as driving through annoying tra c and taking the time to give your friend a ride to the airport or helping people move. It’s saying that friendship/community is built o of knowing you can lean on your friends in times of need and they can lean on you.”

In our capitalistic society, those things de nitely do feel inconvenient a er work and countless personal responsibilities, but being nonchalant is the antithesis of this powerful message.

Will you engage in the radical act of simply giving a fuck?

Mani Asadieraghi @jaidennne

@mani.asadieraghi

Atwork, you smile politely. At home, you switch languages. Online, you become a version of yourself that no one in either world quite knows. For many who live at the intersection of cultures, genders and beliefs, this daily self-editing isn’t vanity. It’s survival.

We call it professionalism, adaptation or privacy. In truth, it’s the social expectation to divide yourself just enough to belong everywhere, yet completely nowhere.

dividuals are le to manage them privately. e result isn’t inclusion but containment: di erence becomes acceptable only in fragments.

Social psychology calls this identity incongruence, the tension between who we are and who we’re expected to be. Research shows that constantly managing others’ impressions quietly erodes life satisfaction by reducing our sense of control and increasing loneliness. e harm isn’t always loud; it lives in the hesitation before speaking, the laughter that feels rehearsed and the quiet relief of not being noticed.

Intersectionality scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw reminds us that institutions built on “single-axis” identities—treating gender, race or sexuality as separate experiences—erase those who live at their overlap. When workplaces, classrooms or even advocacy movements ignore these intersections, in-