2 CHAPTER #

Copyright © 2023 Michael O. Leavitt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reveiwers, who may quote brief passages in review.

ISBN: 979-8-218-18739-2-072-9

Publisher: Lairdhouse Trust

Permissions: Deseret News, The Salt Lake Tribune

Disclaimer: The author and publisher take no responsibility for any errors, omissions, or contradictions which may exist in the book.

Cover Photo: Howard Jackman

Writer: Michael O. Leavitt

Contributing Writers: Laurie Sullivan Maddox

Editor: Megan Anderson

Designer/Production Coordinator: Roxanne Bergener

Special thanks to: Utah State Archives

First printing October 2023

Real and Right

VOLUME 2

The personal history of Michael O. Leavitt

1

Preface

I am a westerner. My hometown is Cedar City, Utah, where I was raised with my five brothers by two loving parents. Time, place, and purpose all begin there.

My forebears had become westerners in the mid-nineteenth century. The Okerlund branch of the family settled in Loa, Utah, while the Leavitts put down roots in Bunkerville, Nevada. One of those ancestors was Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt, who in an unpolished hand wrote down an overview of her life in six pages. Her story describes her conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the persecutions she suffered as a result. She experienced the loss of child and spouse, hunger, exhaustion, freezing cold, searing heat, and a journey both on foot and by handcart to settle this western home of mine.

Sarah’s essay and others on both sides of my family, close and distant, not only inspired me—they stirred an innate feeling of duty to capture what I have experienced and learned. Through genealogy, geography, faith, and affection, I am a westerner because of them.

So now I have concluded seven decades, it is my turn to add chapters to the history of my family, church, state, and nation. I do so with the aspiration that my reflections will offer similar benefit to future generations. Because of my forebears, my life has been much different than those gritty ancestors of mine. I have visited every continent; interacted with kings and presidents; come to know the poor as well as the powerful of the world; and witnessed historical events both triumphant and tragic—none of which would have occurred without my forebears’ sacrifices, goodness, and endurance.

Life and leadership are a generational relay. In fact, the compelling need I felt to write this personal history may have been driven by a desire to discover for myself whether my contributions met my obligations.

A personal history falls on a continuum of candor somewhere between a journal and a published autobiography. It is not a substitute for a journal that records the activities from each day, whether important or trivial. However, it provides the luxury of length and the inclusion of whatever I want to recount.

1

Volume II: Real and Right

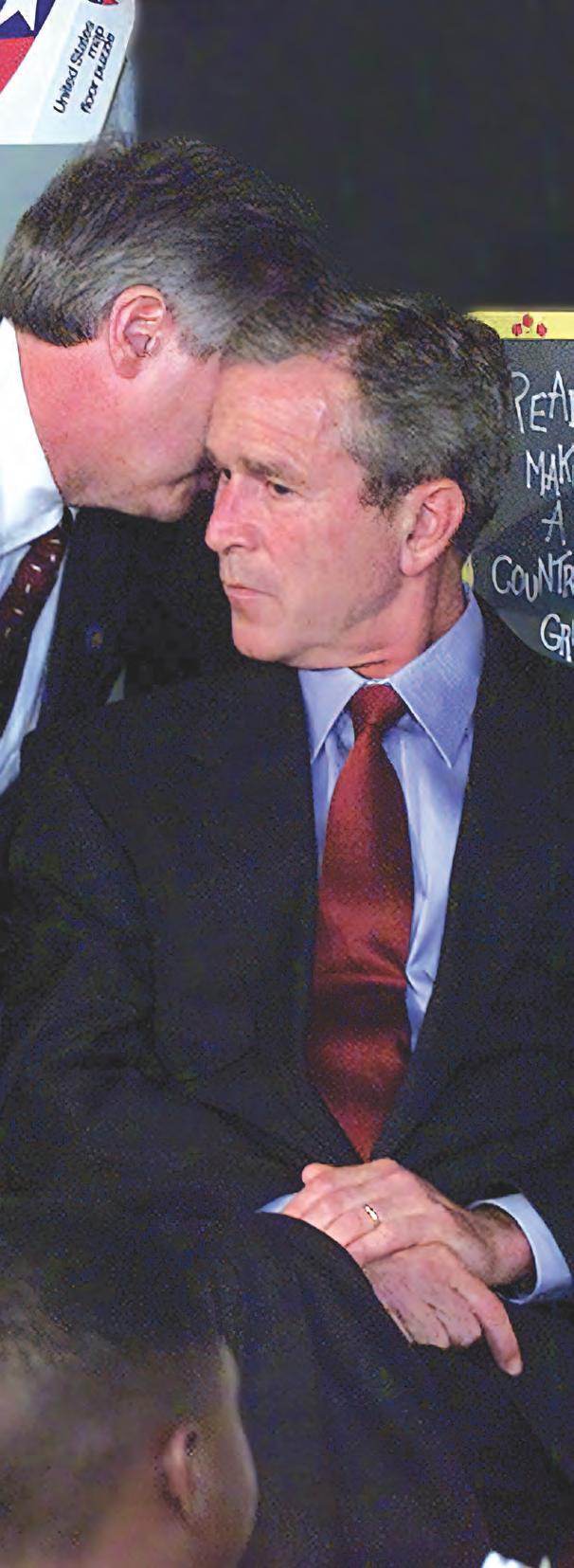

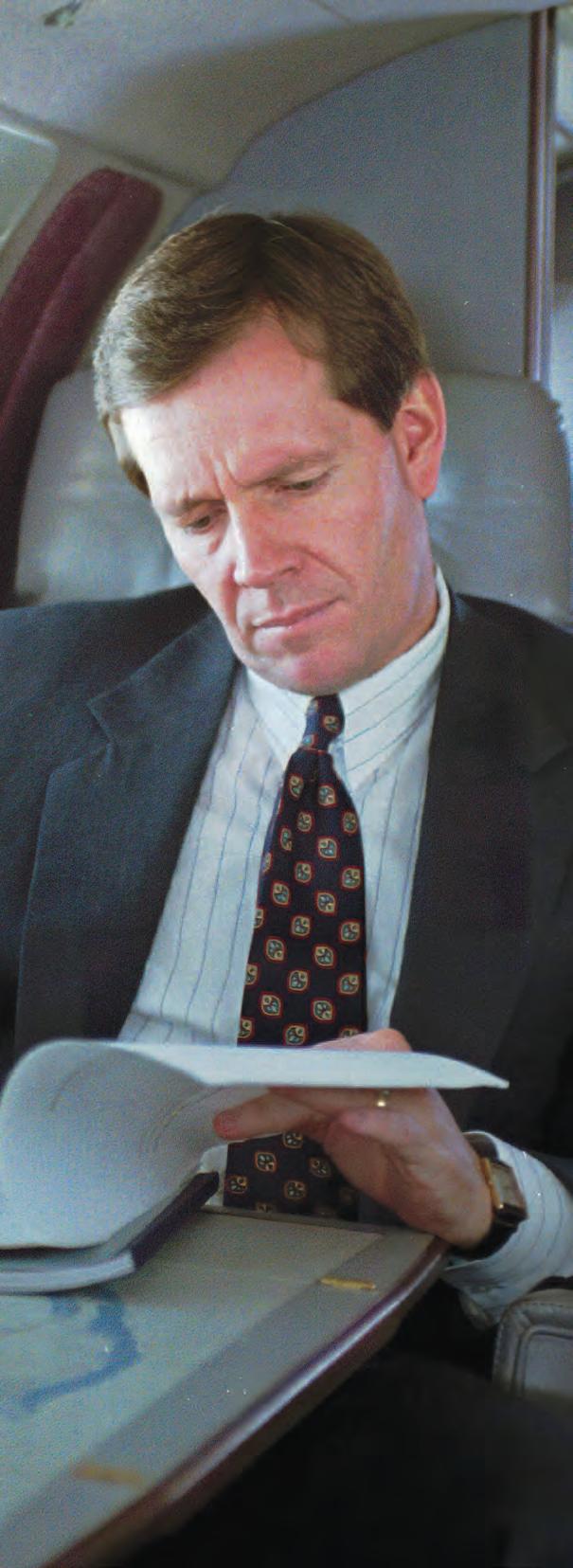

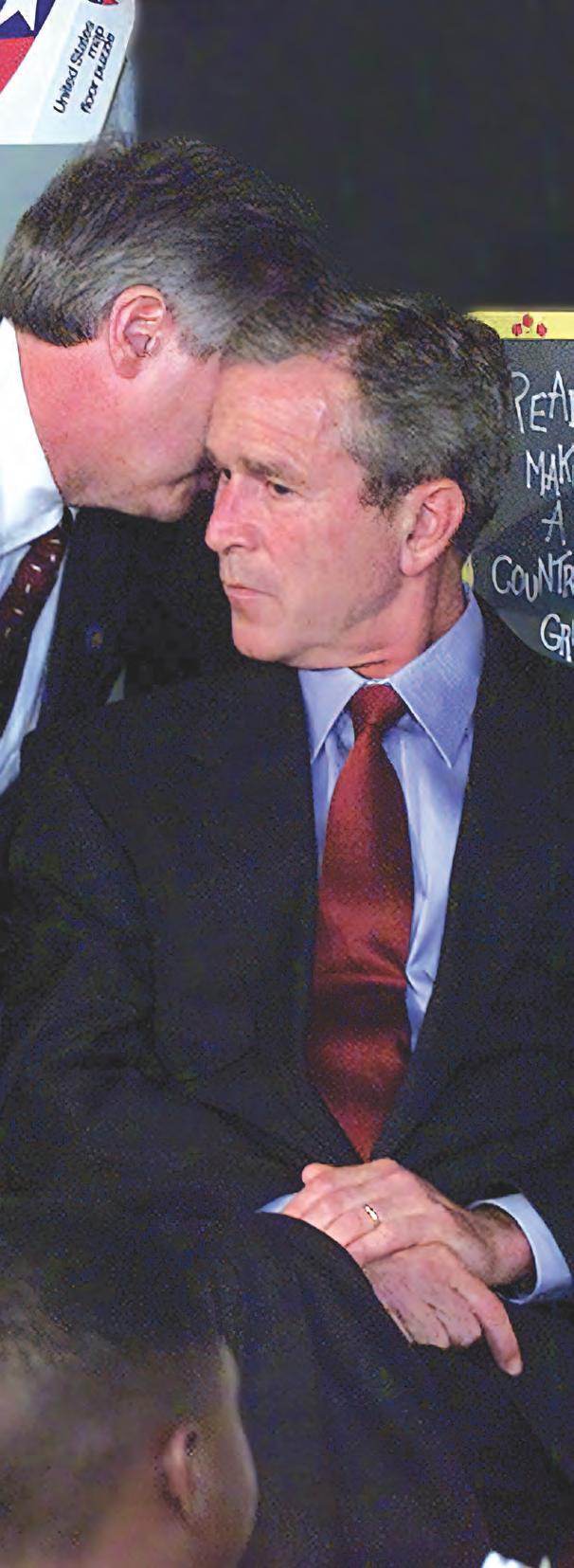

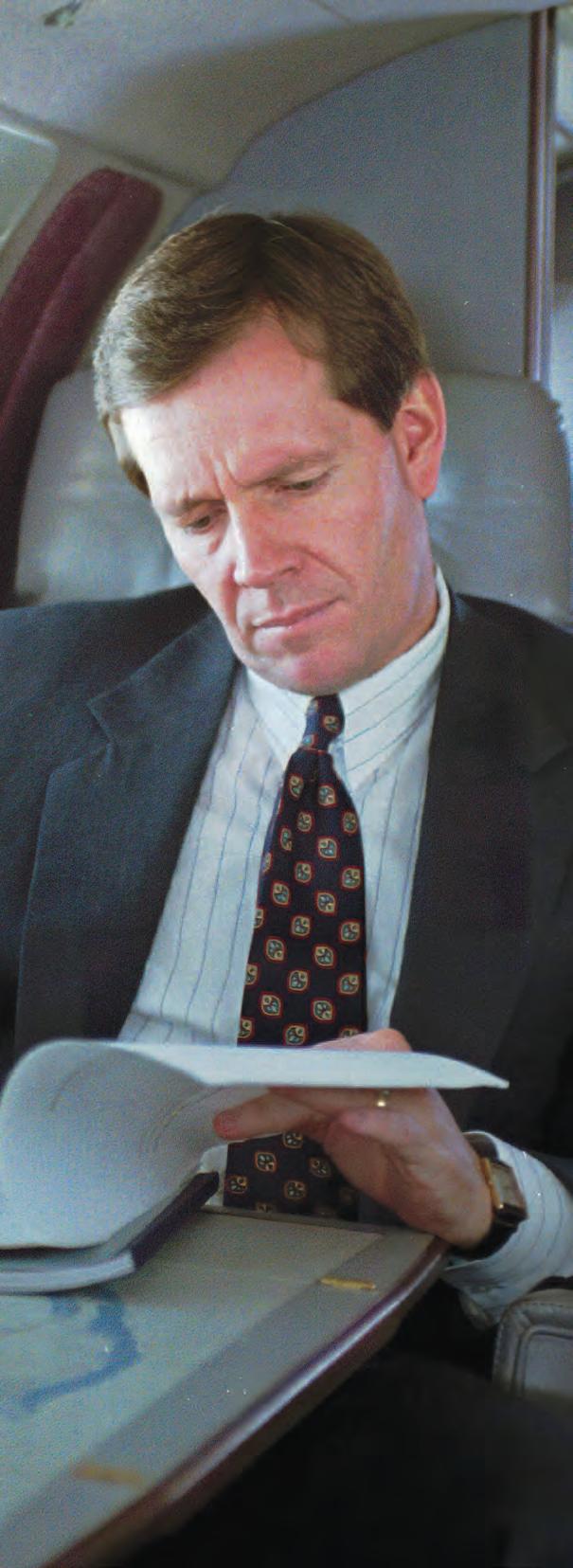

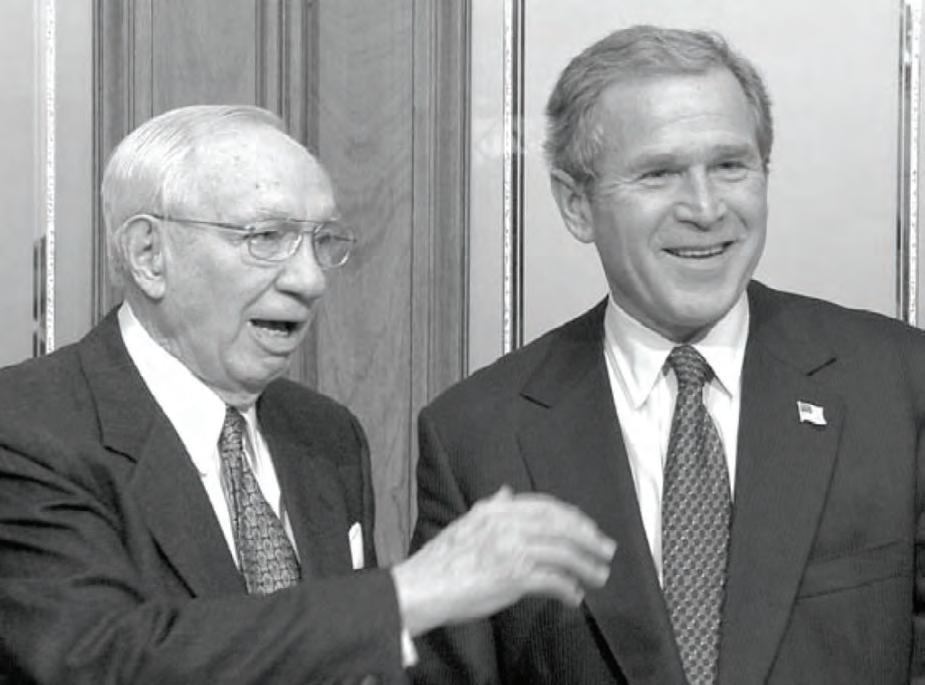

Volume II recounts my stewardship as governor of Utah between January 1993 and November 2003, when I resigned to become a Cabinet officer in the administration of President George W. Bush. The title of this volume, “Real and Right,” was the theme of my campaign for governor in the 1992 election. I wrote this book with the intent to provide a window into my approach to governor, as well as give some insight to the unique aspects of being governor in Utah. I detail how I chose my Cabinet and other important staff members, how I dealt with the media, and how I worked with the state legislature. I give a general overview of the important tasks a governor has, such as giving speeches or staying close with the people.

And since I could not have been governor without my dear wife, Jackie, I have included a chapter on her own initiatives, which have also had a huge impact on Utah. I have also included a chapter on my recollections of September 11, 2001, and some events that occurred because of it as that was also a day that irreversibly affected our country.

My personal history will consist of at least four volumes:

• Volume I: A Sense of Place and Purpose

This volume encompasses both my Leavitt and Okerlund heritage, as well as my own recollections, beginning with my birth in 1951 and ending in 1993 when I was inaugurated governor of Utah at the age of forty-one. This volume includes my upbringing and young adulthood; my early professional life; marriage to Jackie; and the beginnings of our own family together.

Most of Volume I was drawn from two separate books I wrote in 2007 and 2008 with the help of a former colleague in the Governor’s Office, Therese Anderson Grinceri. Those were titled A Sense of Place and A Sense of Purpose. The 2021 version consolidated the two into one— A Sense of Place and Purpose

• Volume II: Real and Right

• Volume III: A Sacred Trust

In my first inaugural address, I used the phrase “a sacred trust” to describe the responsibility I felt as governor of Utah. I have chosen to use the same phrase as the title of Volume III. Volume III responds to a question I am often asked: how would I summarize our most impactful accomplishments during the time I was governor? It takes time for the answer to such a question to mature; real impact occurs over many years. It has now been nearly twenty years since my service concluded, which is plenty of time to get a good sense of what worked and what did not.

In a history like this, one cannot write in great detail about everything, so I asked myself a

2

question: What initiatives produced change and an impact beyond twenty-five years? This book seeks to answer that question by detailing eight legacy accomplishments I believe shaped the future of Utah long-term. Against that standard, I have written chapters on subjects such as the 2002 Olympic games; the land exchange we did with the federal government involving reform of the state’s school trust land system; my role in returning control of welfare to the states; the founding and establishment of Western Governors University; creation of a charter schools movement in Utah; the Centennial Highway Fund, which organized forty-four highway projects, including the rebuild of Interstate 15 and construction of Legacy Highway; and an initiative to double the number of engineering graduates from Utah’s colleges and universities via a partnership between high schools and higher education, which produced forty thousand new engineers and positioned Utah as a technology capital.

• Volume IV: In Service as a Family

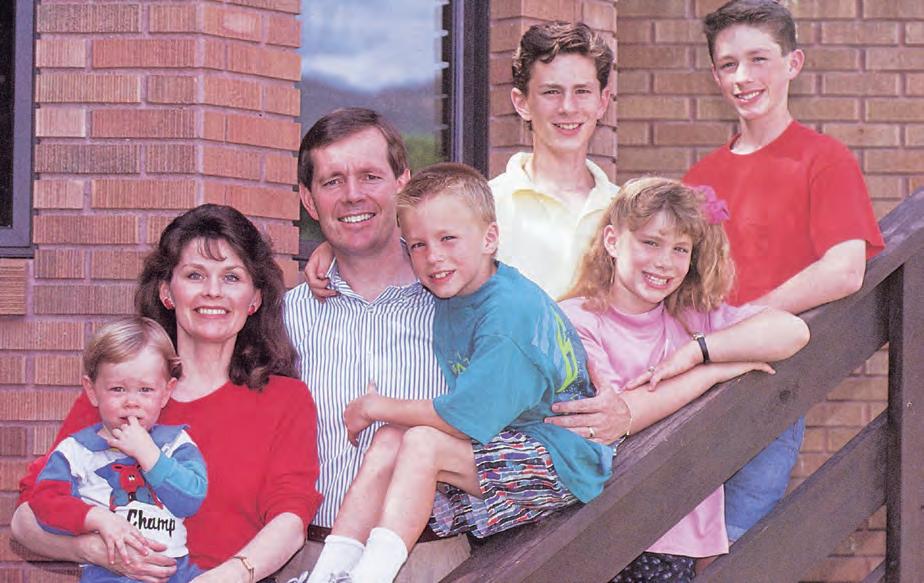

Volume IV turns the focus onto family, with a central question: How did my service as governor affect each of them? When I was elected, Jackie’s and my five children ranged in age from two to fifteen years old. Jackie was thrust into a whirlwind of new expectations and duties, her life no longer her own in many ways. My entry into public life had a profound impact not just on us, but on our parents, my brothers, and her sisters.

To capture this part of our family’s life during these years with accuracy and integrity, I invited Laurie Sullivan Maddox, who served as a speechwriter in the Governor’s Office, to be my co-author on the entire volume. Our desire has been for Volume

III to be a means by which each of the family members could tell their story and perspective. Laurie interviewed each family member at length and then wrote a portion of the book devoted to their account. Each member of the family was given an opportunity to review the chapter for facts and tone.

My contributions to Volume III came in the form of the introduction and a series of short essays— personal reflections on each of my family members’ experiences—placed at the end of their chapters. I also recount my thoughts as a parent during this demanding time and how our family preserved traditions and order.

Future Writing Projects

I plan to write additional volumes of my personal history, since there are many more experiences I hope to write about, such as my time serving on President Bush’s Cabinet, founding and contributing to the success of a group of health care businesses named Leavitt Partners, and my current position as the president of the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square. I also plan to write a volume devoted to my spiritual feelings and experiences. While I have alluded to spiritual feelings and my faith in various parts of volumes one through four, because some of these are more personal in nature, I will write about them separately in a volume that will be held more closely then the others.

It is my hope that these volumes will resonate with readers and take hold in subsequent generations’ histories the same way Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt’s handwritten six pages of personal history galvanized mine.

3

Acknowledgments

In acknowledging those who contributed so much to the completion of this history project, I also wish to describe the process used to write and compile these volumes in hopes my blueprint may be useful to those who feel a similar obligation to capture the events of their lives.

The inspiration I derived from reading my ancestor Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt’s six-page, handwritten history first surfaced in the late 1990s. I was serving as governor at the time and had realized early in my tenure that the telling of personal stories could be an effective way to entertain audiences and convey complicated subjects. However, I suspected I was wearing out some of the stories I used most often. One Sunday afternoon, I decided to create an inventory of events in my life that could be illustrative and would provide a larger pool of possible subjects. Within a short time, I had filled a page. These were not profound stories but rather a list of small, unique, and relatable details.

The list sat for a couple of years. It was then that I read Sarah’s history and concluded that I should not be intimidated by the process of writing. Sarah’s writing was hard to read and had many misspellings, and yet it was a treasure to me. The thought took hold that anything I wrote would be better than nothing at all.

On Sundays and at other moments when I had time, I began to write details around each small tidbit, realizing as I went that the stories could be aggregated into subject matter categories, which then began to tell a larger story. After I transitioned from state government to the federal position in Washington, I recruited Therese Anderson Grinceri to help me compile my memories into a book. In 2006 and 2007 we completed the first two volumes that are now merged into one, A Sense of Place and Purpose

After that, my writing was varied and inconsistent until 2018, when I decided to get more serious about the project. Therese was no longer available, so I reached out to another speech-writing partner from my days in the Governor’s Office—Laurie Sullivan Maddox. I had first known Laurie as a news reporter with the Associated Press and The Salt Lake Tribune. She joined the governor’s staff during my second term and became a co-author of many of my most important speeches, as governor and as administrator of

the Environmental Protection Agency. Laurie has a creative flair and native capacity to give life to words. I wanted to capture that style again for my history venture, and Laurie was persuaded to reenlist. Our working partnership has taken two forms. Through all the books written so far other than Volume IV, I have generated the words and the history, and she has made them better by pushing me for clarity, asking the right questions, and rewriting or refining select portions.

At the beginning of 2021, I set a goal that during the calendar year we would complete at least Volumes I and II, and possibly Volume III. To do that we added two additional people to our little team. Megan Anderson, a busy mom and extraordinary editor, joined our effort. With her editing experience, she has brought order and consistency that neither Laurie nor I could focus on.

Megan also introduced us to Roxannne Bergener, whose skill as a layout artist has combined shape and beauty into a wonderful design. She has a fantastic eye for choosing photos and artifacts that bring our work to life. Like Megan, Roxanne has given our text generation effort structure and discipline. Her dry and irreverent sense of humor enables her to keep us grounded, focused, and somewhere near on schedule. These friendships have been a meaningful part of this experience for me.

Gary Doxey, who was my general counsel in the governor’s office, is a trained historian. He gave me a piece of advice years ago that continues to prove true. He said, “In writing a history, the hardest thing is deciding what to write about. You have to make priority decisions and write.”

As with the other volumes that make up this history, choosing among a wealth of subjects, thousands of pictures, and artifacts has been difficult. I have also suffered over the fact that hundreds of people contributed in important ways to the events described. Not all of them will be mentioned or credited in the way they deserve. For that I have regrets. I hope they will know of my affection and properly attribute the omissions to the complexity of the task.

4

1

One is 10-41

2 A Campaign

3

.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

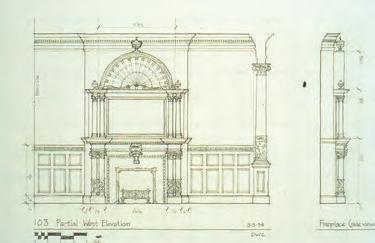

4 Sta te Capitol, Room 200. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. .

. .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 6

5 T he Cabinet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 1

6 Or ganizing Work as Governor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 2

7 T he Mansion Fire. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72

8 Sta ying Healthy as Governor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

9 T he Media . . . . . . . . . . . .

5

Indtroduction 7

. . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Car

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. .

. . . .1 6

Fl ashback . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 6

Transition.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . .

.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96 10 Speech Writing and Delivery . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .103 11 The Appointments Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 12 Other Constitutional Relationships . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115 13 The Legislature. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124 14 Governors Organizations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135 15 Politics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 145

Church and State . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 165

Staying Close to People. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 181 18 Office of The First Lady . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 190 19 September 11, 2001 and War . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 205 Index 224

16

17

6

7

Car One is 10-41

State Street does not just extend the full length of the Salt Lake Valley; it declares itself the dominant road, running eighteen miles from the southern suburbs to the metropolitan center. It leads directly to a hillside where a domed neoclassical building majestically stands—the Utah State Capitol. The State Capitol was completed in 1916 and was subsequently celebrated with immense joy and pride by Utahns just two decades into statehood. In many ways, it symbolized the promise of the twentieth century. Citizens stood at the top of the granite stairs to view the panorama of the Salt Lake Valley and the American West as it unfolded before them. I too have stood at the top of those granite steps to overlook the Valley.

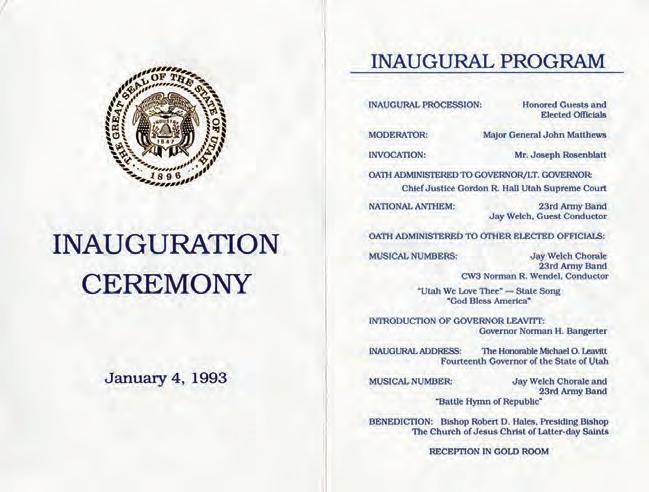

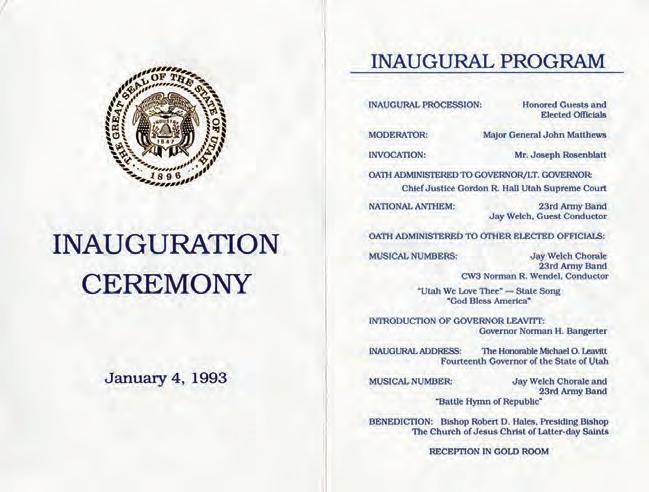

That building and I have a long history. Ever since I was a boy, after spending time with my father as he served in the legislature during the early 1960s, the State Capitol has held significance for me, as well as a special place in my heart. However, January 4, 1993, would link me to the Capitol building forever. It was Statehood Day, the ninety-seventh anniversary of Utah becoming America’s forty-fifth state, and inauguration day for me as Utah’s fourteenth governor.

Driving up State Street this particular day, the dramatic reveal of the Capitol complex at the top was unforgettable for me. Framed by bare trees in the winter gray, the massive white

8

01

building radiated splendor. Giant flags adorned the great columns; soldiers milled about the grounds, attending to artillery pieces, which would fire a salute precisely at noon as the oath of office was completed. The place bustled with electricity and formality. Inaugurations may be the incoming governor’s show, but they’re the Utah National Guard’s production.

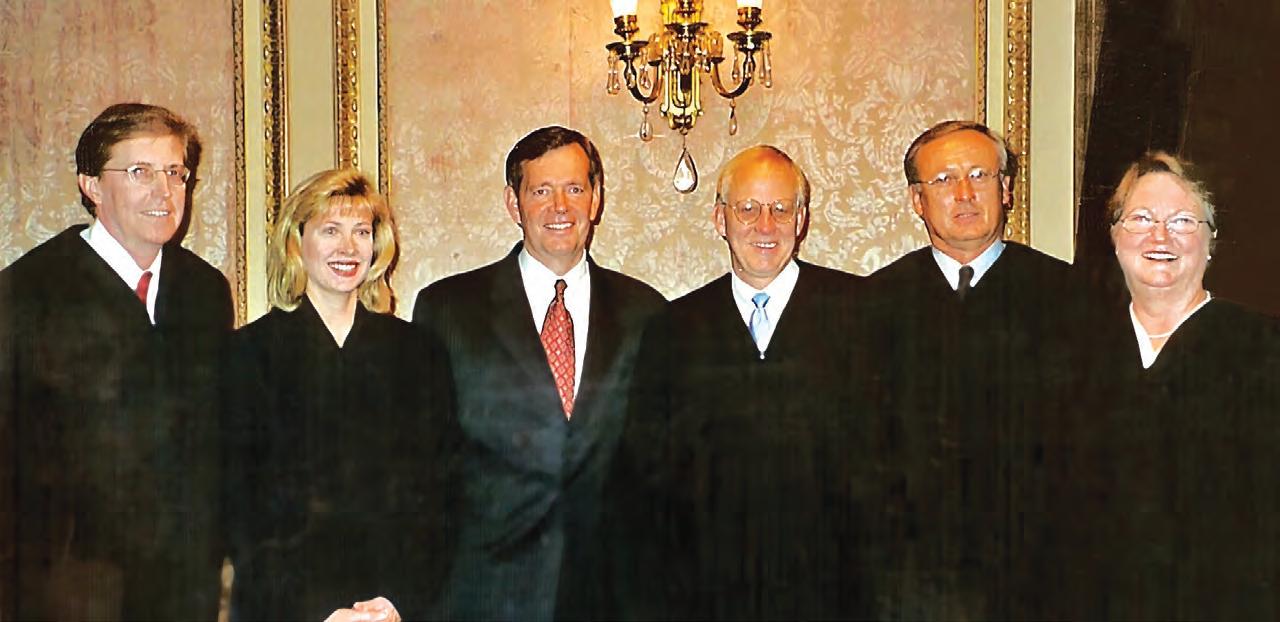

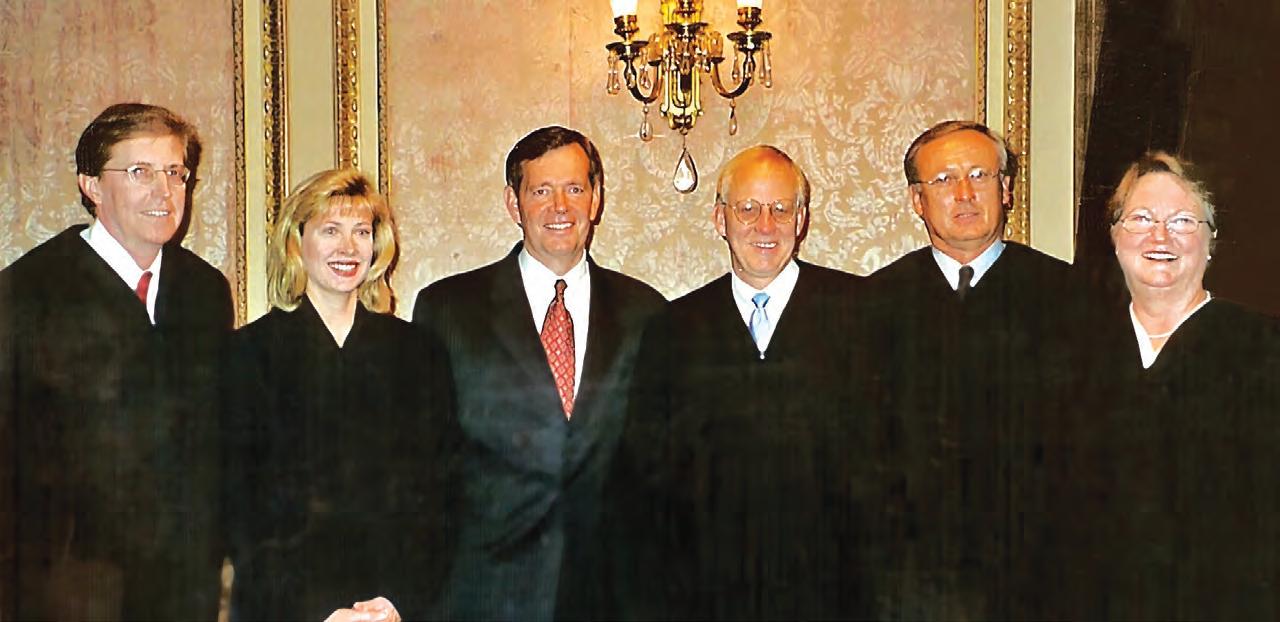

Jackie and I entered the building at the west doors. The rotunda was filled with row upon row of chairs; staging had been erected on the midpoint landing of the east rotunda steps that led to the Supreme Court. People had begun to arrive, and their early-bird status was rewarded by the Jay Welch Chorale and 23rd Army Band, both finishing brief rehearsals. Television camera crews were testing the equipment that would broadcast the ceremonies simultaneously on the state’s television and radio stations. Arrangements had been made for our children to be transported separately so they wouldn’t have to wait—a practical concern for Jackie, who knew the difficulty of containing five children ranging from two-and-a-half years old to sixteen. We were ushered to a committee room within the legislative wing to greet other podium guests and wait for events to start.

“ Ladies and gentlemen, the Governor-Elect, Michael O. Leavitt!“

Protocols called for each platform guest to be introduced separately while standing on the west stairs, then for the guest to proceed down a pathway to the east stairs where the stage stood. There were many guests; members of the Supreme Court, legislative leadership, former governors and first ladies, current and former statewide officers, newly elected officials, outgoing Governor Norm Bangerter and Mrs. Colleen Bangerter, and finally, the new First Lady. Jackie looked beautiful in a striking red jacket and black skirt. She waved at the crowd as she walked, with the poise and confidence

acquired from many occasions in the spotlight as a pageant queen, musical performer, and elementary school teacher.

I was introduced last, accompanied by Adjutant General John Matthews, who would conduct the ceremony. As I stood on the far landing, a man I had known for many years was sitting in the audience directly behind where I was to be introduced. He apparently had a matter he wanted to lobby the new governor about, and I guess he thought this was the perfect chance. He tugged on my pant leg. I looked down to acknowledge him, expecting we would exchange smiles. “I need to talk with you about…” his voice trailed off. Timing is everything. “Do you think we could talk about this later?” I whispered back as the announcer intoned, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Governor-Elect, Michael O. Leavitt!” It was one of the earliest reminders of the duality of elective office. I was both chief executive and public servant.

On I went toward the stairs, and what a lovely walk it was. The band played a Sousa march, and the crowd was made up mostly of my friends and supporters. There were smiles, waves, winks, and thumbs up as I passed. We were all there together to share this particular milestone in both the state’s and my history. They stood and applauded; I walked and choked back tears.

We reached the bottom of the white marble stairs. I intuitively took the steps two at a time, realizing halfway up that I had taken my military escort, General Matthews, by surprise with my double-time ascent. I paused to wait for him. We both laughed and finished the climb. It was a spontaneous expression of how I felt—ready to get started with the job. Possibly, too, it was a younger man’s impatience: at forty-one, I was the second youngest governor in Utah history.

Once settled in my seat I could see the faces of all the people I love the most. Jackie was by my side; I could see my children, dad and mom, and Jackie’s parents. Both grandmothers were there, as well as my brothers and their families, friends, the campaign team who had fought long odds and won. One would like to savor a moment like that, and I wish I could report some profound thoughts.

9 CAR ONE IS 10-41

But up to this point, it was mostly an adrenaline rush constrained by the practical considerations of simply carrying out the process. There was only one nagging little worry. I reminded myself more than once, “Do not mess up the oath.”

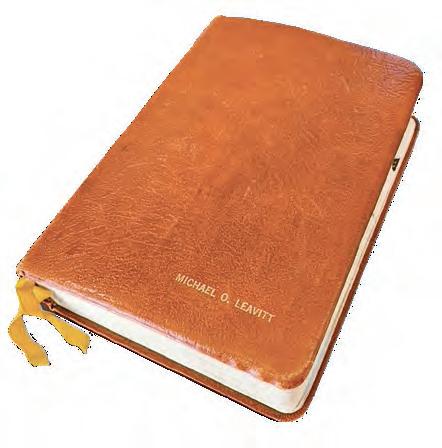

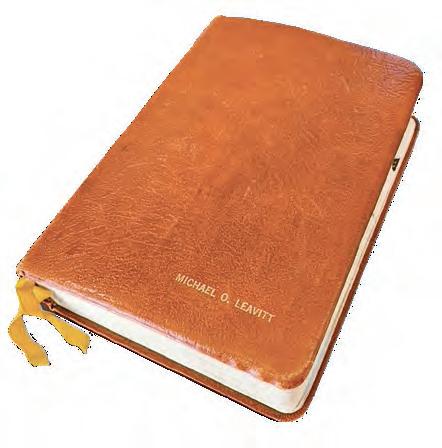

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Richard Howe officiated. Jackie stood by my side, holding my brown leather Bible, upon which I would swear an oath of office five times over the next sixteen years. Justice Howe began: “I, Michael O. Leavitt.” I took a deep breath and in a strong voice designed to push away the tears welling in my eyes, I spoke, departing slightly from the script: “I, Michael Okerlund Leavitt, do solemnly swear...” The use of my middle name was an important tribute to my heritage and a way of honoring my maternal Okerlund grandparents. The oath went off without hitch. A dozen seconds to complete, and with that I was governor.

A number of impressions flood your mind during an occasion like this. You take in all the sights and sounds of such a grand assemblage. You’re aware, abstractedly, of the enormity of the moment. You’re vividly clear on what you need to do to execute it, and know that you must perform in a sense, but not overdo it.

I was aware that history would capture this moment, and that my actions should comport in a certain way. I clasped Jackie’s hand and we raised our other arms in a celebratory wave.

Amid the satisfaction of having achieved a high position and the excitement and grandeur of the event itself, there was a humorous flashback that kept me grounded. Standing on those marble stairs outside the Supreme Court chambers, my mind

raced back to my friend, Dan Eastman. We met twenty years earlier as aspiring professionals, and had become the closest of friends. He had called the night before to say he was driving down the road when the thought popped into his head: “Tomorrow, Mike Leavitt is going to be governor.” The idea of his buddy elevated in that manner struck him as hilarious. He had just burst out laughing.

The retelling had cracked me up as well when he told me, and it made me smile now. To some extent I felt the same way—I knew I was going to be governor, but the thought of it didn’t overwhelm me as much as it amused me. The absurdity of it deep down, that this had actually happened, gave me considerable mirth.

Then, as a twenty-one-gun salute shook the walls, I stepped forward to the podium for the inaugural address.

Inaugural speeches should be different than other speeches a political leader gives. They are personal expressions of vision, leadership, and values, and less about programs, strategy, or tactics. They are a place where a bit of moralizing is acceptable. In retrospect, my first inaugural, while sincere, was too long, included too many stories, and could have been stated with more efficiency. However, it firmly established the purposes of my service and expressed my view of government’s role.

“ I, Michael Okerlund Leavitt, do solemnly swear...“

The speech highlighted five objectives, which would carry on through all three of my terms as governor:

1) Improving Utah’s education system; 2) Building a stronger economy around higher-paying jobs; 3) Protecting our state’s quality of life;

4) Assuring that government did not grow faster than the private sector; and 5) Using government to reinforce and foster self-reliance and personal charity. It also affirmed my view that the federal government had become too large and dominant in

10 CHAPTER 1

Bible used for swearing in.

11 CAR ONE IS 10-41

1 Decorative pillar in the Utah State Capitol

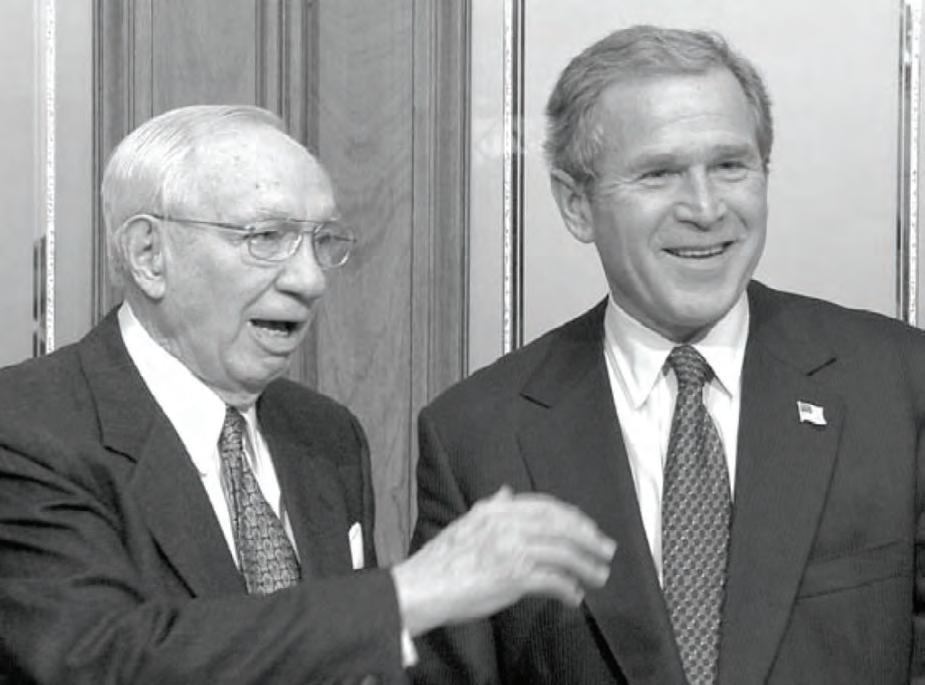

2 Governor Norman Bangerter standing with Mike during the inauguration ceremony.

3 Presenting the flags of the United States of America and the State of Utah

4 Lt. Governor Olene and Myron Walker

1 2 3 4 5

5 Members of the Jay Welch Chorale performing on the rotunda stairs

12 CHAPTER 1

1 Justice Richard C. Howe

2 State Treasurer Edward T. Alter

3 Attorney General Jan Graham

1 2 3 4 5

4 Mike and Jackie at the ceremonial swearing in 5 Mike giving his inaugural speech.

CAR ONE IS 10-41

the lives of Americans. “I believe governors of this nation will ultimately need to take a historic stand to demand discipline, sanity and a better balance in the federal system,” I told the gathering. “I intend to be part of that effort.”

To cap the speech off, I reached back to home and family, specifically the words of my mother, Anne Leavitt. She had written a note to congratulate me, and in it was a nugget of motherly advice. I read the note verbatim:

Dear Michael,

When you were a little boy and television had just come to our town, the show you never missed was Gunsmoke. Strangely, the part you liked the most occurred before the episode began. It was the part where Matt Dillon rode his horse up the ridge, paused, leaned forward on the saddle horn, and described the rigors of being a U.S. Marshall in Dodge City. In a perfect imitation, you used to gallop your stick horse though the house, stopping at appropriate intervals to declare in your deepest four-year old voice, “It’s a chancey job, and a little lonely.”

Well, here you are again, son… a chancey job, this time for real. But I have a strong sense of security knowing what you understand so well. That in this job, as in any other, even when you feel lonely, you really never need to be alone.

The following day, when I was by myself in the governor’s ceremonial office, I felt a distinct and familiar impression that my mother’s reminiscence was right—I need never be alone in that role.

After the inaugural ceremony, a reception was held in the Gold Room of the Capitol. It was a festive moment, but it was also very much something we wanted and needed. We felt profoundly indebted to so many people who had sustained us and helped us win. We knew nearly everyone who attended, more than a thousand people. We hugged or shook hands with each and celebrated for just a moment with all.

All the newly sworn state officers were in the line, and so it moved at a snail’s pace. I was getting increasingly uncomfortable having people wait. Necessity being the mother of invention, Jackie and I invented the reverse moving reception line. Rather than wait for people to travel to us, we grabbed the security team and said, “Follow us.” We began working our way up the reception line. The hand shaking, hugging, and celebrating continued, but at a much faster pace.

Mid-afternoon, we left the Capitol to officiate in further inaugural events, which would go on for an entire week. And in my first “official” trek down State Street, I had a new handle as well. Utah Highway Patrol Sgt. Alan Workman, who would be with me as part of my security detail for the entire period in office, handed me the UHP radio and said, “Tell them, ‘This is Car One, I’m 10-41.’” The car the governor is riding in, no matter what car it is, carries the law enforcement handle of “Car One,” he explained. A series of codes or shorthand must be memorized by every police officer for radio use. Each one starts with the number 10. Code 10-41 means, “I’m signing on duty.”

My thumb pressed the key. “This is Car One,” I said. “I’m 10-41.” And so I was. 10-41 for the next 3,961 days, three elections, and one turn of a century.

14

Entering the Capitol rotunda, Mike is being escorted by Adjutant General John L. Matthews. 23rd Army Band, Utah National Guard seen in the background.

15

A Campaign Flashback 02

How had we gotten here? Looking back, the campaign for governor almost felt surreal. Implausible in some ways at the outset, but eminently—and obviously—winnable.1

When I made the decision to run in March 1991, I had just turned forty. Family and friends comprised my base of support—my only support at that point. I had guided other candidates to victory before as a political consultant, but

had never run for office myself. There were more than a dozen better-known candidates making sounds about running. And when the first newspaper polls on the race came out, I was at the bottom of the candidate pack at one or two percent.

I was not thinking of running for public office until Senator Jake Garn called me just before Christmas in 1990 to say he would not be running for reelection. He urged me to run for his seat

CHAPTER 2

16

1. A more detailed history of my first campaign can be found in the first book of this series, A Sense of Place and Purpose.

and promised to support me. A month earlier, on November 29, Governor Norm Bangerter had announced that he would not seek a third term. Two of Utah’s top political offices would be open seats in the 1992 election.

I seriously considered the Senate run, assessing it from all angles, before ruling it out. It just didn’t feel quite right. The governor’s race was nowhere in my equation—until one day, it was. A few weeks after the senate decision, I was talking with pollster Dan Jones, and he stunned me with a suggestion. “The person who really ought to run for governor is you,” he said.

The idea lingered in my mind and then took hold. It felt audacious and magnetic at the same time, and there was a deep sense of rightness about it. I felt a certainty to run and a rational belief that I could win. From that point on, I was essentially in.

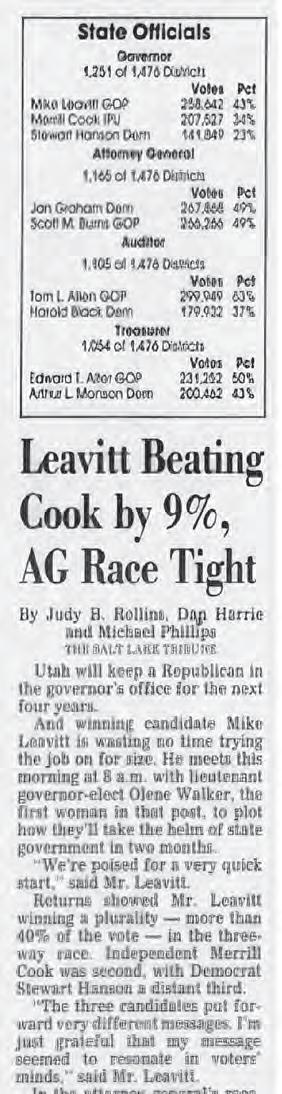

We were victorious, of course. Eighteen months of hard work and worry, constant fundraising, impactful advertising and messaging, and a number of key decisions—some risky—combined to deliver the victory on November 3, 1992.

Into the Arena

Anyone running for office must first make an honest appraisal of whether they can win. Though I had never run before, there were several reasons I was viable.

First, I knew Utah’s political process and players from the inside out, having managed or chaired eight statewide campaigns in the previous fourteen years, including two major ballot initiatives. I was experienced with debates, speeches, public engagement, television interviews, town halls—and liked them. Being at one to two percent in the polls when I started did not worry me. Almost every successful candidate starts small and then becomes elevated through the process.

A second rationale was my appetite and aptitude for public policy. Through my service on the Utah Board of Regents and Southern Utah University’s Board of Trustees, as well as the Legislative Strategic Planning Committee for Public Education, I had developed serious ideas I wanted to

see implemented. The voter initiative campaigns I led helped me develop a working knowledge of the state budget and the way the system worked. I had come to believe I was pretty good at solving significant problems.

I also had noticed an interesting pattern regarding Utah’s gubernatorial races. None of the past four governors had ever held statewide office before. All of them came from the business community, had backgrounds outside Salt Lake City, and were not widely known when they started.

Starting out, one of my most significant deficiencies was that I did not have a political base, and in order to make it through the caucuses, conventions, and into the primary election, I needed one.

The business community, rural Utah, and educators were all possibilities, given my background and professional experience. But it was state legislators I targeted—and who ultimately became a solid base and formidable advantage.

Early on, I undertook an aggressive schedule of visiting House and Senate members, traveling the state to talk with them individually and help them get to know me. Month after month, and under the radar of other prospective candidates, I developed relationships, giving them the time to make up their minds. Initially, my goal was to gain the support of one-third of all GOP legislators. By the fall of 1991, I had pledges of support from all but two.

“ The person who really ought to run for governor is you.“

Money was another key consideration in the early days—and an ongoing challenge for the duration of the campaign. Financing the campaign of any first-time candidate is not unlike raising money for a start-up business; most of the money is raised by personal appeal of the candidate or entrepreneur, and both look initially to friends and family.

I leaned heavily on our family businesses, borrowing $20,000 from the Leavitt Group to

17

CAMPAIGN FLASHBACK

A

get started. I also turned to each of the Leavitt Group agencies, and to other insurance companies as well. Were it not for early money like that, starting a statewide campaign would have been extremely difficult.

A campaign memo from October 1991 laid out my finance plan, which had three basic categories of fundraising: large donors, a finance committee, and direct mail. The large donor plan was straightforward—find 150 people capable of giving $1,000 or more, and I would call on each of those people personally. For the finance committee, we planned to recruit people in every county for the committee, asking them to nominate potential donors that the campaign would further cultivate with letters and mail. Our direct mail plan involved sending letters over a rolling period of time asking people interested in the campaign to donate.

“ Bring quality jobs and quality education to Utah.“

The memo set our goal at $400,000 by February 1992, but we fell short. It took us until the June convention to raise the first $400,000. However, we raised more than our competitors and spent it wisely. I would estimate 65 percent of the $1.8 million raised during the entire campaign was raised by me personally. There is no other way unless a candidate self-funds their campaign.

Up to that point, I had a regular traveling aide-intern, but no staff. Nolan Karras, a good friend and former Utah House speaker, was chairing the campaign, and my friend and former consulting partner, Bud Scruggs, headed my strategy committee. Rob Glazier, one of Bud’s students at BYU, came on as manager, along with KayLin Loveland as scheduler and office manager. And in one of the most important decisions I made, I asked LaVarr Webb, former political editor and later managing editor of the Deseret News, to join the campaign. He agreed, bringing enormous talent, leadership, and intellectual power to the endeavor. As 1991 gave way to election year 1992, we were rolling.

Election Season

On January 7–8, 1992, we kicked off the campaign with a news conference at our house on Laird Avenue and a twenty-four-stop tour of the state. I announced my candidacy, promising to “bring quality jobs and quality education to Utah.”

By candidate filing day, April 15, 1992, the field was set: Democrats Pat Shea and Stewart Hanson Jr.; Independent Merrill Cook; and five Republicans—me, Richard Eyre, Mike Stewart, Dixie Minson, and Dub Richards.

Eyre, a well-known Utah consultant, public speaker, and author of several best-selling books on family life, was my greatest threat for the Republican nomination. Education issues became a key distinguisher between us through the party caucuses, county and state conventions, and into the primary election.

The Eyre campaign centered on a school voucher system, which played well among his more conservative constituency in the GOP. Under Rick’s plan, parents would be given a government-issued voucher for $1,000 to go toward the child’s education at a school of their choice—public or private. Rick believed it would encourage free-market competition among schools.

I believed wholeheartedly in markets and considered public education to be a monopoly in need of a challenge. However, my plan to inject market forces into public education centered on charter schools, which provided choice to parents without reallocating existing public-school funding and subsidizing wealthier families with children at high-priced private schools.

My education plan borrowed heavily from the state strategic plan I had worked on the previous four years and centered on competency-based education, local control of schools, and the use of new technologies in the classroom.

Competency-based advancement and technology enablement in education were introduced in the first campaign and remained primary themes throughout my time as governor.

18 CHAPTER 2

In the campaign, my position on education and work on the education strategic plan were central to gaining the endorsement of the Utah Education Association, a step critical to getting me through the state convention. The UEA was never going to endorse Rick Eyre, but I had to head off an endorse ment of the next strongest candidate in the race, Mike Stewart. Stewart was a former history profes sor with a PhD in constitutional law who was will ing to say he would raise taxes for education—a key UEA goal. I would not make that pledge.

The endorsement came to me in the end, and it was a turning point. We achieved it after a stee ley-eyed conversation with UEA leadership, fol lowed by one-on-one meetings with all twenty members of the union’s political committee. I would not hedge on taxes; instead I urged UEA leaders to look beyond the pledge to the longer game. Mike Stewart couldn’t beat Rick Eyre, but I could. If they pledged their support to Stewart on the strength of his tax pledge, they would end up fighting Rick Eyre for the next eight years.

The endorsement gave me significant advantage. More than nine percent of the delegates at the state convention elected at the party caucuses were educators.

Two days before the caucuses, we received more positive news. The Deseret News reported on April 25, 1992, that I had pulled ahead of Eyre in the polls, leading 34 percent to 24 percent among all respondents, regardless of party. Among Republicans, I had a two-point lead over Eyre. I never again trailed in public opinion polls throughout the primary and general election.

The state convention, three months later in June, brought a stumble, but not a setback. It also required two more strategic campaign decisions that made a substantive difference in the successful outcome of the campaign.

One was the selection of Olene Walker as my running mate. Olene had served for eight years in the legislature, including time as the Utah House majority whip. She grew up in Ogden and had earned a bachelor’s degree in political science

from Brigham Young University, a master’s degree in political theory from Stanford, and a PhD from the University of Utah. After the legislature, she directed the state Division of Community Development and was vice president of Country Crisp Foods. She was a terrific pick and a valued partner who worked side by side with me for the next eleven-and-a-half years.

The other critical decision was whether to draw on personal savings to buy advertising, which would boost my momentum and standing in the polls in the immediate post-convention period heading into the primary.

Jackie and I ended up loaning $20,000 to the campaign—money we had saved up to buy a new car. In addition, $20,000 was borrowed from the Leavitt Group. The campaign spent all of it on billboards and radio advertising. It was enough to sustain a noticeable showing for three weeks of advertising at a level we believed could break through. It was a big bet, and had I not survived the convention, it would have been a total loss.

19

Indeed, I survived the convention, although it was not my campaign’s finest hour. The convention was a two-day event on June 27–28. On the first night, an ultra-right group circulated a nasty, negative tabloid about me containing groundless assertions about my ideology. My campaign protested to the party chairman, who declined to do anything about it.

The next day, my candidate presentation was lackluster. We had a group of student performers from Southern Utah State College, whose act was a bit amateurish. Then I mixed up my speech pages on the podium and had to awkwardly lapse into my stump speech.

By the time voting started, I felt deflated and disappointed, sensing a letdown in our momentum and, conceivably, diminished chances of coming out of the convention. It was one of the hardest moments of the entire process. Eyre took first place, and we were second. We had lost our lead by thirty-eight delegate votes—enough to propel us into the primary, but still a bitter disappointment.

The Primary

We had to project the look, feel, and trajectory of a winner. And we did it with a shakeup in our advertising strategy; a creative genius named Chuck Sellier; and our most memorable television ad.

Based on a gut reaction—and a proposal and compelling vision laid out by Chuck on how to reach voters at the level of their values through storytelling—I brought Chuck on board to create our television spots. It cost us our relationship with our existing advertising agency, R&R Partners, but Chuck Sellier became one of the most important people involved in my political success.

His first ad for us became the “Real and Right” tractor ad, based on my grandfather’s story about a farmer down the road who had more land than he could afford. It was a remarkably beautiful piece of work, and a brilliant way of introducing me. Without stating it blatantly, the ad spoke of my values, my family, and what was important to me.

Other ads followed. To counter Rick Eyre’s charge that I was captive to the UEA, we produced an ad about rewarding good teachers and firing

bad ones. The public loved it; teachers hated it. We also did an ad that emphasized the need to provide quality jobs so that our children wouldn’t have to look outside the state for work.

Real and right; reward good teachers, fire bad ones; and quality jobs—those were the three messages we used for the primary election.

I had already decided coming out of the state convention not to attack Eyre or Cook, despite the risk involved in not negatively defining them before they attempted to define me. We remained positive in tone and messaging, even when opponents lashed out or made themselves look bad by their behavior or tactics. As the frontrunner heading into the primary, I increasingly came under fire.

Rick Eyre regularly leveled condescending barbs that I was young and lacked substance on issues, while Merrill Cook attempted to make a big deal of the whirling disease outbreak found in fish at the family’s hatchery business in Loa. I maintained composure in the face of attacks, and the personality differences on display only bolstered my momentum.

Just before the primary election, Governor Bangerter endorsed me. Senator Jake Garn had publicly announced his support of me earlier in the summer, and the two endorsements were impactful, since sitting officeholders rarely take sides in their party’s primary. Bangerter’s endorsement particularly antagonized the Eyre camp, which then tried to capitalize by claiming I was the establishment candidate and Norm’s handpicked successor.

In the final days before the primary, the candidates’ respective positions on issues had been clearly formulated. My belief in federalism became prominent as I spoke of Utah needing greater flexibility from the federal government in providing welfare and other services. I also spoke of wanting to lead the nation’s governors in a crusade to restore the proper balance between state and federal governments. My five campaign themes—quality jobs, quality education, quality of life, fostering self-reliance, and limited government—had been regularly conveyed and would continue through the general election.

20 CHAPTER 2

21

A CAMPAIGN FLASHBACK

1 Mike, Olene Walker, and Jake Garn on the campaign trail. Logan, Utah

2-4 On the campaign trail

5 Working with R&R Partners advertising agency on campaign ideas.

6 Filming our first commercial at Laird Park. We gathered friends from the neighborhood to serve as extras.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

7 Leavitt family hits the trail to do some campaigning.

On the ideological spectrum, there were obvious delineations as well. I was center-right, Eyre was to my right and favored by a more conservative element, and Cook cast himself as a populist anti-establishment type in the Libertarian mold.

On Tuesday, September 8, primary day, my name appeared for the first time on a statewide election ballot. We had maintained a substantial lead in tracking polls for weeks on end, and by 10:00 p.m. that night the outcome was clearly established. More than 46 percent of registered voters had cast a ballot. Olene and I won 56 percent of the vote, compared to 44 percent for Eyre and his running mate Steve Densley.

The biggest surprise of the night was on the Democratic side. The more liberal Stewart Hanson Jr. beat moderate, pro-life attorney Pat Shea for the Democrat nomination. Though Hanson was behind in the polls, the pro-choice community had turned out in massive numbers to push him over the finish line.

With the primary election over, I would face off with Merrill Cook and Stewart Hanson in the general election.

General Election

Pat Shea likely would have appealed to middleof-the-road voters in the general election, drawing some of that support from me, but now he was out of the race. With a more left-leaning Stewart Hanson as the Democrats’ nominee, I began to view Merrill Cook as my main opponent. A Deseret News poll taken before the primary, but released five days afterward, indicated as much. That first general election snapshot had me at 44 percent; Cook at 26 percent; and Hanson at 17 percent.1

Utah is a Republican state, and people intuitively presumed that I would win. However, with just fifty-three days to go, and my opponents behind and running out of time, it was clear that both would train the focus of their attacks on me.

Our strategy had four imperatives: First, we needed to consolidate the Republican party and bring Eyre and his supporters over to my side. If they moved toward Cook, victory was not automatic. The second imperative was to raise the money required to fuel a solid campaign. Third, because our opponents had every reason to gang up on me, we had to control the agenda by raising new issues and ideas. Finally, we had to avoid mistakes. Bad decisions on how we responded to attacks could hurt us; likewise, becoming too aggressive could backfire as well.

National politics also were a significant variable; Utah’s governor’s race was directly impacted by the presidential race. Ross Perot, a wealthy businessman from Texas, had formed an Independent Party, qualifying on the ballot in all fifty states. His politics bridged the gap between Republican and Democrat ideologies, appealing to the conservatives and moderates who were skeptical of the establishment. Merrill Cook was running within this surge of independent zeitgeist, and Perot’s race gave him a template. Perot had started out nearly even with Republican President George H.W. Bush and Democrat Governor Bill Clinton in early polling conducted in February 1992. By June, he was the frontrunner, with 39 percent to Bush’s 31 percent and Clinton’s 25 percent. The existence of Perot’s campaign allowed Cook to harness the energy of the national effort, using many of the same volunteers. It was the perfect atmosphere for a thirdparty effort.

Merrill Cook saw an opportunity to attack when health care reform surfaced as an issue in the presidential election and trickled down to state campaigns. I had not spent much time thinking about it, but Cook pounced at one of the debates, blasting me for being part of the insurance industry—therefore part of the problem—and for having no solution or plan. He proposed using the state’s worker compensation fund as a pooling mechanism for health insurance for the state’s uninsured, which was not a bad idea. But then he also proposed a payor-play system where small businesses could either buy private health insurance for employees or pay up to five percent of payroll into the state fund for

22 CHAPTER 2

1. Bob Bernick Jr., “Republicans Hold Healthy Leads over Major Foes,” Deseret News, 13 September 1992. https://www.deseret. com/1992/9/13/19004487/republicans-hold-healthy-leads-over-major-foes

employee insurance. I knew this part of Cook’s solution was problematic, but because I didn’t have a solution of my own, I couldn’t counter it.

I dug into the issue with assistance from several health policy experts. The position we carved out acknowledged the problem and listed a series of policy reforms, and I committed to initiate a process to look at the big picture. Many of the reforms I recommended were enacted in my administration as part of Utah Healthprint, which I initiated during my first two years in office.

Cook continued his aggressive posture, running attack ads contending that I couldn’t fund my education reform package without raising taxes, that I was beholden to the health insurance industry because of campaign donations, and that I was a political crony who had been selected by the Republican Party to stop Cook’s tax-cutting initiative in 1988. We responded with an ad saying that despite the attacks, we would not go negative but would continue highlighting our “real and right” initiatives.

A little more than three weeks from the election, however, we had a major scare when our daily tracking polls, conducted by Dan Jones, began showing downward movement for me and an upward trend for Cook. The trend persisted over successive days, and within a week or so, our lead had shrunk from more than a dozen percentage points down to five or six. The numbers were deeply unsettling. Emergency meetings were held, and our strategy team was divided over whether the surveys were an unexplainable anomaly or a true measure of an upswing for Merrill, for which we would need to counterattack. The campaign team of Senate candidate Bob Bennett, who were also conducting tracking surveys, shared their results with us, showing I was still ahead. But we were uncertain of the poll’s reliability. My spirits sunk. It felt as if the atmosphere of discontent Cook had tried to foster with his Independent candidacy was taking root in the final weeks of the campaign, and we were slipping uncontrollably toward a loss. For me, it was the lowest point of the campaign.

Finally, Dan Jones suggested we get a different pollster to conduct a brushfire survey. I called

a friend of mine, Todd Remington, who had a polling company in California. Within days we had his results. They were consistent with the Bennett poll, so we were indeed ahead. Dan Jones never determined what happened, but our campaign’s restraint in holding back a counterattack or making brash decisions served us well.

Two days away from the election, a Deseret News/KSL-TV poll showed me nine percentage points ahead of Cook.

Money was flowing easier by this stage in the game. Many people waited to see how the race developed before they committed their contributions. We had seen a boost just after the primary, then a leveling. In the final week before the election, a wave of “smart money” came rolling into the campaign.

23

CAMPAIGN FLASHBACK

A

In all, we had raised $1.8 million over the eighteen months of the campaign. The final pre-election finance report on October 28 indicated that we had spent $1.3 million on the race. Of that amount, I loaned $60,000 to my campaign. Merrill Cook had spent nearly $700,000. Eighty-two percent of that, or $574,000, came from Cook himself. The rest was made up of smaller donations ranging from $5 to $100. Stewart Hanson had spent nearly $400,000, with the bulk of his financial support coming from labor unions. I had received donations from nearly every interest group except unions.

I continued to collect endorsements as election day neared, including Richard Eyre on October 22, and sixteen prominent Democrats who announced their endorsement on November 1. The weekend before the election, my campaign distributed literature to 400,000 households. We had the phone lines running hot with calls encouraging people to vote. And we had increased our media buy in the final two weeks.

On election day, I looked back on the past year and a half. It had been long and difficult, but also empowering. The experience of listening to, and really hearing, all manner of Utahns in thousands of visits and meetings in cities and towns across the state had refined me. I felt like a different person from the one that had started down the path eighteen months before.

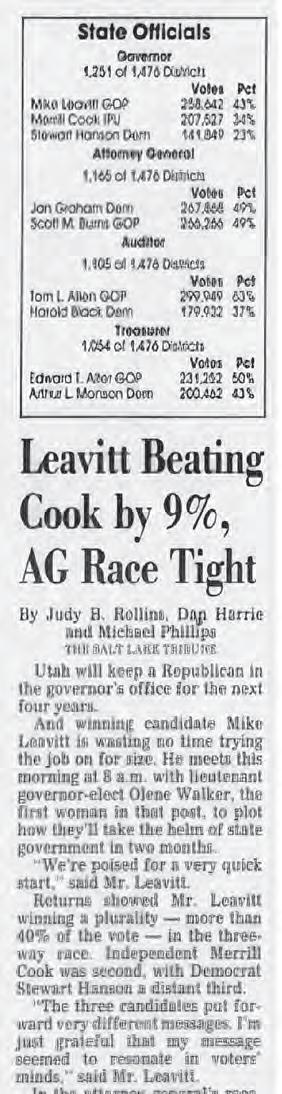

As voting continued throughout the day, I stayed away from campaign headquarters, spending time calling key supporters and inviting people to the election night gathering at the Little America Hotel in Salt Lake City. Jackie and I assembled the kids and headed down to the hotel about 7:00 p.m. Within two hours of the polls closing, it was clear that I would be the fourteenth governor of Utah. The results were Leavitt, 42 percent; Cook, 34 percent; and Hanson, 23 percent.

The scene was exuberant in the hotel ballroom. Family, friends, and supporters shared the

jubilation. Everyone who was a part of the Leavitt campaign celebrated, and the first indicator of change became evident when a security detail from the Utah Highway Patrol formed up around me as soon as the outcome appeared certain.

I barely slept that night, but it didn’t matter. The next morning could not come soon enough; everything felt new and incredibly exciting. The adrenaline rush car ried over into daylight, along with a sense of purpose and a bit of impatience. I had a meeting with the cam paign staff first thing that morning to start moving forward with the transition and to prepare for the inauguration, which was exactly two months away. We had won the day and were eager to get on with the term.

24 CHAPTER 2

Courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune

25

A CAMPAIGN FLASHBACK

1 2 3 4 5

1-5 Election night celebration

Transition 03

Waking up governor-elect was exhilarating. We had to formulate an agenda, plan an inauguration, review department heads, appoint staff, wind down the campaign, and much more. It was a dizzying list of obligations. But compared to the pressure of the campaign, it felt positively sublime.

Once a new governor is elected, the action— and the spotlight—clearly moves to them. Everybody is interested in the future, not the past. All governors get their turns as the exciting new face and the departing old hand, and it was important to me not to intrude upon Norm Bangerter’s final weeks. At the same time, however, I wanted a quick start to begin framing the construct of the new administration.

Two days after the election, with lieutenant governor-elect Olene Walker at my side, I held a press conference to announce the next steps in the transition. I also announced that I would begin appointing new department heads by month’s end, reiterating my intent to give state government the freshness that comes with a change in administrations.

“This is a new administration. This is the Leavitt-Walker administration. There will be new faces, new directors, and new priorities,” I told reporters. Additionally, I promised a different management style from the Bangerter administration. “After the first one hundred days, there will be no question in anybody’s minds about the difference between Mike Leavitt and Norm Bangerter. I think we’re in for an exciting four years.”

26

Such change is always necessary, I explained, because government cannot renew itself. “That’s why we have elections.”1

New Faces, New Priorities

Though it was a frenetic pace, we had gotten a little bit of a head start. A month before the election, I had asked Nolan Karras to head up a transition team, and he produced a remarkably detailed plan that laid out, step by step, the decisions we needed to make. Among the first recommendations was the early selection of a chief of staff, and there was a list for that, too.

One of the names that stood out to me was Charlie Johnson, Governor Bangerter’s budget director. I offered the position to Charlie in late October, and he accepted, although he could not be freed from his responsibilities in the Bangerter administration until he finished the state budget in mid-December.

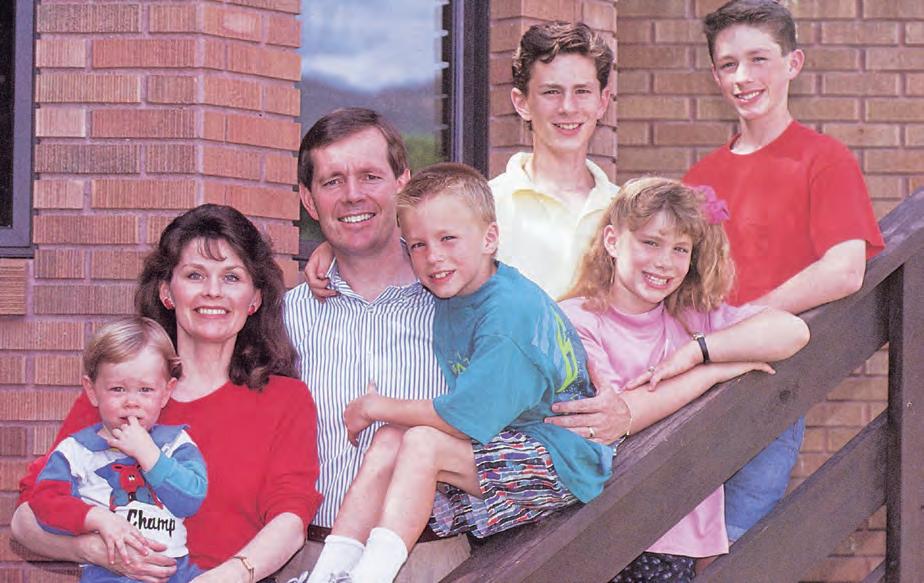

Toward the end of election week, Jackie and I took a breather. We made a quick getaway with the children to San Juan Capistrano, California, to reassure the kids that despite this major development in our lives, we were still a family. We stayed for a few days in a beach house made available by Larry Lunt, a personal friend.

The trip to California was the first time we had traveled with a security detail—a strange new reality. The highway patrol officers and I were uncertain how to handle some things. Did they really need to spend the night parked outside the house? If I wanted to go for a walk, did they have to follow and if so, how close? What degree of confidentiality could we count on? Did we need to factor their presence into conversations, or were they reliable enough to keep family things private? What exactly were their duties? Soon enough, these basic questions were answered and life with a security presence became routine.

Thankfully, Jackie and I were able to go for long walks along Capistrano Beach, where our conversations were mostly focused on how we should deal with this new family dynamic.

Our first major decision was whether we should live in the Governor’s Mansion. We had moved into our home on Laird Avenue almost fourteen years before the election. For Jackie, the prospect of leaving it felt like an abandonment of warmth, privacy, security, and peace. The Governor’s Mansion viewed from afar seemed cold, publicly exposed, and disruptive. To me, it felt adventurous, interesting, and new. Our children were quite conflicted. They sensed the adventure but also intuited a degree of change and undefined social costs. They asked where they would attend school and church and how their friendships would be affected.

We reached an important compromise: We would keep our home on Laird but rent it out; we would move to the Governor’s Mansion, but the children would stay in the same schools; and our family would attend church at the same Latter-day Saints ward.

When we returned from California, we felt more prepared to deal with the changes coming our way. Jackie called First Lady Colleen Bangerter and arranged to spend time walking through the mansion to size up the task ahead of her. I turned back to the dizzying list.

Along with the transition demands, I had been invited to the National Governors Association’s seminar for new governors in Colorado Springs, Colorado, in mid-November. Right on its heels were meetings of the Republican Governors Association in Wisconsin and the Western Governors’ Association in Las Vegas.

UVCC Vote

Additionally, there was a critical piece of business left in my tenure on the State Board of Regents—a vote on changing the status of Utah Valley Community College—looming very quickly.

During the campaign, the question of granting four-year status to Utah Valley Community College (UVCC) had become a controversial issue. It divided the higher education community, including the Board of Regents. I had not resigned as a regent

1. Lisa Riley Roche, “Leavitt Pledges a Quick Start and Fresh Style as Governor,” Deseret News, 5 November 1992, https://www.deseret. com/1992/11/5/19014388/leavitt-pledges-a-quick-start-and-fresh-style-as-governor

27 TRANSITION

28 CHAPTER 3

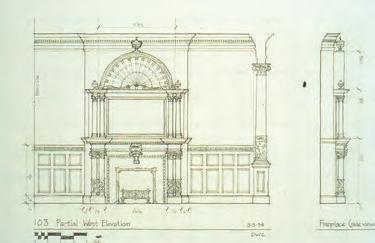

1 Governor’s Mansion

2 Night view of the Utah State Capitol.

1 2 3

3 Family photo taken at the Laird home after winning the election.

while running for governor, reasoning that if I lost, I could continue serving out the four remaining years of my term on the board.

The regents had put off dealing with UVCC’s request until after the election due to the political sensitivity. It was clear to me the vote was going to be close. In fact, I thought there was a good chance that without my vote, the vote would be tied and the measure would die. I had already decided that Utah County needed a public, four-year teaching college. Brigham Young University was limiting enrollment and making it nearly impossible for most in-state students to gain admission. And it was simply not feasible for students from the fastest-growing region of the state to depend on the University of Utah, located more than forty miles away.

Few people knew if I would attend the meeting, which was held November 10, one week after the election. I had been deliberately vague in order to keep people from pressuring me. When I walked in the door, it created quite a stir. As I recall, I said very little, conscious of my new status as governor-elect, but cast the deciding vote to allow the college to offer three bachelor’s degrees on a trial basis. I took a little heat over it from critics of the policy, but the passage of time has clearly shown it was the right thing to do. The three initial bachelor’s degrees offered were business management, computer science and information systems, and technology management. One year later, UVCC’s name was changed to Utah Valley State College, and in 2008 it became Utah Valley University.2

Transition and Staff Building

Work on the transition was moving forward. Nolan Karras and his team had appointed a series of sub-teams charged with making overviews of each department of state government. I had wanted many teams like this for two reasons. First, taking even a cursory look at an entire state government involved an enormous amount of work, and second, I wanted everyone who had played a significant role in getting me elected to feel part of the victory.

Co-chairs led each of the teams, who were tasked to interview each department’s leadership, inventory the major challenges they faced, and make recommendations on any organizational changes we wanted to undertake during the first legislative session. Those reports needed to be integrated with commitments I had made during the election so that an agenda could be finalized. The timeframe for compilation of reports was three to six weeks.

During the second week following the election, we moved into a small suite of offices, which Governor Bangerter had provided for us on the first floor of the State Office Building. We also needed staff, but there was virtually no money available for transition salaries.

Charlie Johnson, who was tied up with the budget, did double duty with the transition when he could. LaVarr Webb kept the gaps filled, as he always did, and we divided the rest of the campaign staff into two groups: One to plan the inauguration and the other to help with the transition. I assured the campaign staff that an opportunity would be available in state government at some point in the near future. But there were two positions I knew we needed to fill quickly—a media spokesperson and a personal assistant.

I already knew who I wanted as my spokesperson. Vicki Varela and I had worked together on the Board of Regents and on three referendum

29 TRANSITION

2. https://www.uvu.edu/visitors/history.htm

Leavitt Home on Laird Avenue

campaigns during the previous four years. She was talented, experienced, and I enjoyed working with her. A few days after the election, I called to open the conversation. She was interested but not sure. It took several days of conversations and working through some important employment arrangements, but she finally agreed.

The job of assistant was filled after a fortuitous call from my father. He told me that a former employee of his in Cedar City, Alayne Peterson, had talked with him recently about moving back to Utah after a number of years living in Texas. It had been years since I had seen Alayne, but I remembered her as able and fun. She had helped on my

father’s own campaign for governor in 1976 for a short time before moving to Texas.

Alayne and I talked over the phone, and I invited her to come to Salt Lake so we could discuss the job face-to-face. Then I had a better idea to save time and money. Sensing that it was a great fit, I offered her the job over the phone.

LaVarr Webb’s leadership throughout the campaign had been exemplary, and I considered him as a potential chief of staff. Ultimately, I concluded the administration needed LaVarr in a position where his mastery of strategy, concepts, words, and ideas would be foremost, while Charlie could focus

CHAPTER 3

30

Utah State Capitol Rotunda

on operations. LaVarr remained by my side as an invaluable policy advisor and trusted friend.

Our transition committee reports started coming back. Each one had a series of recommendations for the new leadership of the department. In many cases, we also asked the transition committee to provide me with names of prospects for department heads. Every few days we made appointments of new personnel—each one a building block for a new administration.

There were a couple of important things we did in developing the administration. First, in choosing my cabinet, not a single person was asked if he or she was Republican or Democrat. I hired people I

thought were competent and on whose loyalty I felt I could rely. Second, I hired mature and seasoned people. There is a tendency in building government administrations to fill them with people who got there politically. We hired many young people who had helped on the campaign, but those who served in the most senior positions of my administration were experienced people with track records of success.

On November 25, I announced I would appoint four deputy governors, one of whom would be Mayor Joe Jenkins of Provo. We needed to make the announcement in a timely way so that Joe could resign as mayor and be ready by inauguration day in early January.

TRANSITION

31

Then, a few weeks later, the plan shifted. Instead of deputy governor, we changed Joe’s assignment and asked him to head up the Department of Community and Economic Development. We also dispensed with the title of “deputy governor,” going instead with a slight variation of the terminology—for example, deputy for policy or deputy for intergovernmental affairs. That kind of decision was important because it helped to empower members of the staff and began to define portfolios of responsibility.

Our first staff meeting was held on November 28. Our discussion centered on the appointments of department heads. The first two were announced shortly thereafter: Ted Stewart was named director of the Department of Natural Resources, and Raylene Ireland was announced as director of Administrative Services.

I felt the need, too, to begin reaching out to state employees. We organized meetings with the division directors of each department. Each time I have taken over a large organization, I have found it important to spend time getting to know the employees in groups of fifteen to twenty. After these meetings, I then hold a larger meeting with all employees—a pattern that evolved when I became governor. I’ve refined it over the years but generally found it to be an important and effective way of connecting with a lot of people.

In the small meetings it is important to say only a little at the beginning and to ask each person to tell me about themselves. Almost always the sessions reveal things colleagues in the same office didn’t know about each other, so there is an element of discovery. It soon becomes evident to them that the purpose of the discussion is to learn more about each other as people, not laying out policy and procedures.

I don’t introduce myself formally, but as people talk about their lives, I share bits and pieces of my own story. By the time we get to the end of an hour or so, I’ve told them a lot about me in pieces but always in a context of relating to their lives.

There are significant benefits to this approach. First, chemistry is important, and you leave knowing some people a bit better and having a story to help you remember them. Second, they leave knowing more about you as a person and understand that you value them as a person, not just as a functionary in an organization. Lastly, every detail about the conversation spreads like wildfire throughout the organization. The details aren’t as important as the firsthand reports on what the new guy is like.

New Governors Seminar

One of the most valuable experiences I had while preparing to take office came with my introduction to the National Governors Association, an organization I would become heavily involved with in subsequent years. The NGA holds a seminar for new governors every other year, where veteran governors share their experience and advice with incoming governors.

The “class of 1992” included a handful of newly elected governors like myself, plus others who had already taken office but had not attended before. Among the presenters was Governor John Engler of Michigan, who had been elected two years earlier. I spent considerable time talking with Engler. He had been in the news frequently because the Michigan Legislature, in a hostile act toward him, had repealed the property tax, throwing the state’s tax system into chaos. Rather than vetoing the bill, as legislators assumed he would, John embraced the idea as an opportunity and forced a reform on the tax system. He became a hero among conservatives.

Being so newly minted and green, I didn’t feel anywhere near the same stature as Engler, or even the longer-term sitting governors who were in attendance. I felt like a minor leaguer just being called up to the majors.

Sessions were frank and comprehensive, ranging from expectations and ethics to staffing and balancing family and work time. Spouses were included in their own sessions. What made the seminar most unique was the complete absence of partisanship. I was not sure which party several of the instructor governors belonged to.

32 CHAPTER 3

Perhaps the most lasting thing to come from that three-day conference was the relationships it fostered. Over the years, I worked with the governors I met there in different ways, and genuine friendships developed.

Afterward, Jackie and I, along with our team, flew to Wisconsin to attend the Republican Governors Association meeting. We had immediate staffing needs addressed and transition work well under way. Still, I was filled with anticipation to get back to Utah and to keep pressing forward. I had so much to do, and a narrowing window of time before inauguration day.

Media Brushfire

In early December, we had our first mini crisis with the news media. I had asked Doug Bodrero, head of the Department of Public Safety, to develop a method of conducting background checks on candidates for key positions. He recommended we use a form used by law enforcement agencies to screen new police applicants. I looked at it quickly

and approved it. Doing a background check seemed like a good idea, and I didn’t want to reinvent the process.

Several days after the first forms went out, the Deseret News reported I was asking candidates to disclose if they drank alcohol and what prescription drugs they used. The questions were clearly on the form, and although it was an appropriate inquiry for a position in law enforcement, given the religious sensitivity the use of alcohol had among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, our use of it was interpreted as a religious litmus test.

Every major news organization pounced and ignited a brushfire. Kathryn Kendall, staff attorney for the Utah chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, said of the form, “Is it legal? Yes. Is it moral? No. Asking questions about personal background … smacks to me of an ideological litmus test. The governor is precluding diversity.” Kendall went on to say that the form suggested to other employers, “it’s okay to invade the privacy of workers under the pretense of deciding who’s going to do a good job.” 3

TRANSITION

33

3. Lisa Riley Roche, “Leavitt Appointees Subject to Detailed Background Checks,” Deseret News, 5 December 1992, https://www.deseret. com/1992/12/5/19019791/leavitt-appointees-subject-to-detailed-background-checks

LaVarr Webb and I were in Las Vegas at Western Governors’ Association meetings when the story broke. LaVarr attempted to tamp down the accusations of heavy-handedness by saying, “We do want to maintain a high ethical standard and we want to make sure employees don’t have anything in their backgrounds that will cause embarrassment.” 4

The reporter then spoke with Charlie Johnson. He was asked if Governor Bangerter conducted investigations on potential appointees. Charlie replied that Bangerter interviewed candidates to determine if there were any potential problems rather than asking them to undergo background checks.

Amid the tumult, I was leaving the Salt Lake Hilton one day following a speech and was surrounded by media. All they wanted to ask about was the questionnaire. I said, “I’m taking responsibility for this. I’m not dodging the fact that the questionnaire was inappropriate. I was horrified like everyone else.” I acknowledged I hadn’t read the form closely enough, and I told them the form would be replaced.

It was an important first test. I needed to show the media I would deal directly with them and take responsibility. In addition, we learned a good lesson about the need to run a tighter ship to avoid giving multiple messages to reporters.

Countdown to the Inauguration

During the last couple weeks of the transition, we began to frame policy positions on three important controversies that continued throughout my entire first term as governor. The first was whether the state would continue to support appeals on a lawsuit challenging Utah’s abortion law. The second was litigation related to Utah’s system of child protective services. The third involved Utah’s willingness, or lack thereof, to store high-level nuclear waste. It is important to note how quickly a new governor is put into a position to make lasting and important policy decisions.

As the holidays approached, Jackie and I knew this might be the last Christmas we would have in our home on Laird. While that didn’t turn out to be true, the thought made that year especially significant. Our children were young and about to experience great change in their lives.

On December 30, The Salt Lake Tribune reported the appointment of six more department directors: Bob Wilcox, Insurance; Connie White, Commerce; Dianne Nielson, Environmental Quality; Cary Peterson, Agriculture; Ed Leary, Financial Institutions; and Joe Jenkins, Community and Economic Development. I also named Lynne Ward as my budget director.

I had earlier announced the appointment of Lane McCotter as director of the Department of Corrections, and the reappointment of Doug Bodrero, staying on as director of Public Safety. With Ted Stewart and Raylene Ireland named weeks earlier, I had eleven members of the cabinet lined up and ready to go.

Just before New Year’s, the Bangerters invited Jackie and me to accompany them to the Copper Bowl to watch the University of Utah football team in action. We traveled to Tucson, Arizona, together in the state plane. The trip was a nice way to reconcile the changeover for both of us. I took care to remain a secondary figure and to respect Bangerter’s stature as governor, if just for a few more days.

34 CHAPTER 3

4. Lisa Riley Roche, “Background Check on Leavitt Staff Sought,” Deseret News, 4 December 1992, https://www.deseret.com/ 1992/12/4/19019631/background-check-on-leavitt-staff-sought

35

View of Utah State Capitol from Memory Grove - Fall colors - Matt Morgan, Courtesy of Utah Tourism

State Capitol, Room 200 04

Walking into the Utah Governor’s Office the day after the inauguration was among the most exhilarating moments of my life. Equal parts excitement, gratitude, satisfaction, responsibility, resolve, and confidence—tempered by a dash of fear. Everything was new and interesting, and it felt as important as it was. The weight settled quickly on our new team’s shoulders, but we loved the way that felt.