18 minute read

Chapter 6

from Real and Right

Organizing Work as Governor

I have often described the job of governor as ten different overlapping jobs, with the gravitational pull of nonstop opportunity, a ticking time clock, and a steady supply of new problems creating a job with virtually endless potential demand. If the governor was willing to meet with people at 2 a.m., there would be no shortage of takers. While I was never very successful in modulating my pace, I worked at it constantly. I found ways to multiply my productive output and keep normal life at least within sight.

A Short-Term Plan with Long-Term Results

In the Governor’s Office, things changed so fast we would often find ourselves responding randomly. I found it useful to get the senior team together for a couple of days to essentially recalibrate how we deployed. We did this twice a year. Most commonly these outings would be in the late spring, after the legislature and bill signing had concluded, and then again by early fall as we approached the next legislative session. There was no exact time on the calendar; it was more when I felt our (and my) focus was wandering. We got better at this as the administration matured. If I were to serve again, I would formalize the process.

One thing that improved these recalibration meetings was something I learned after visiting Australia shortly after the Sydney Olympics in September and October of 2000. I had made a trip to Australia in order to learn from their experience, specifically, to understand how they exploited the games to stimulate economic expansion. While there, I met a key figure who had led the Australian government’s efforts in managing the Olympic Games. He described how both a short-term and long-term plan needed to be developed and recounted how Australian leaders created benchmarks for their progress, quantifying accountability by measuring goals completed within a specified number of days.

I realized I wanted to apply this concept, not just to the Olympic games but also to Utah economics as a whole. On the plane ride home Rich McKeown and I conceptualized a concept I referred to as a thousand-day plan with a ten-thousand-day horizon, and I have used this model ever since. It was a thousand-day plan for economic renewal in Utah, to do things like bring unemployment down or strengthen education. The thousand days are a rolling period of time that is recalibrated periodically—priorities are added and deleted due to changing circumstances. The larger number is the vision horizon, the smaller number reflects a shorter tactical period where we do things in order to shape the world toward the longer-term outcome.

Thousand-day plan, tenthousand-day horizon.

I have varied the time periods to fit the circumstances. For example, during my time as Health and Human Services secretary, I used a five-hundredday plan with a five-thousand-day horizon. We did a formalized recalibration every 250 days, and the five thousand days took us to the end of our term.

In my service as governor, we had the benefit of a clear set of purposes—the five key principles I established when first running for office in 1992. They were refined as we went but did not fundamentally change.

At the retreats, the senior staff and I would start by reviewing the five primary objectives. Then we would start listing all the things we were working on or wanted to work on. Typically, we would then prioritize them considering their urgency, the opportunity, or ripeness for progress and how well they moved one of our major objectives forward.

At the end of the retreat, our goal was to have a consolidated list of things to work on, with staff assignments laid out according to how we prioritized in coming months. The lists tended to be divided into three groups: (1) Our state agenda, (2) Problems we had to solve, and (3) National and regional initiatives (National Governors Association, Western Governors’ Association, etc.). The Washington D.C. office tended to be the center of activity on national and regional agenda items and all others were driven by our state capitol team. It was the chief of staff’s job to coordinate it all.

Over time, we figured out we could travel to some fun and interesting places for these retreats— without great expense. For example, several times we went to my family ranch in Loa. We used a friend’s retreat in Palm Springs once, visited Antelope island, and even went to a National Guard facility at Camp Williams.

Scheduling Meetings

Our strategic objectives wouldn’t be met unless we allocated time to them. Therefore, the most important routine meeting of the week was the scheduling meeting.

Ours often lasted two hours. We would hold them either in the Governor’s Office or in the small dining room at the Governor’s Mansion. I generally conducted the meeting. The staff that usually came was Alayne Peterson, the chief of staff, communications director, head of the security detail, and a representative of the lieutenant governor’s office, as well as Jackie and her staff. While the meetings were not designed as such, they inevitably became strategic sessions as we sorted among competing demands and priorities.

Alayne would bring a pre-screened collection of requests that had been received during the week, generally thirty to forty. One at a time we would discuss whether the request fit into our priorities. The schedule was divided into fifteen-minute blocks.

We developed different tools to multiply or leverage my time. For example, if I was doing appointments with people from outside the office, we would try to do them in blocks so I could have time for preparation and staff work. If a meeting needed to be held, but it could held by the lieutenant governor, a cabinet member, or a senior staff member, it was managed that way. Another favorite time extender was the “cameo.” Under this arrangement a staff member would meet with the person, and I would stop by for the last five minutes. The staff member would quickly summarize the meeting, define the issue, and then say what he or she recommended. I would either concur or make a suggestion.

I always wanted people who came to the Governor’s Office for an appointment to feel like we were pleased they came; a meeting with the governor was usually a very big deal and of real importance to them. The key was to have someone else do most of the listening and summarize their request. I would always try to repeat back to the person what I understood them to want.

On particularly busy days we would organize a “dental model.” We called it this because it was like having patients in multiple dental chairs at the same time, with assistants getting ready for the dentist to work. Staff members would organize meetings in multiple rooms at the same time, telling those in the meeting that the governor would join shortly. I would move from meeting to meeting, spending a minute to make our guest feel I was focused on them. I would ask the staff member to summarize what had occurred already rather than starting the meeting over. Their job was to tee up the appropriate response quickly. I would either confirm the conclusion or make another suggestion and then excuse myself, moving to the next room. The staff member would then be responsible to carry out the required follow-up.

This dental model was particularly useful when we were meeting with groups for proclamations or bill signings. We could have meetings with a dozen groups in an hour, including pictures.

Today, I carry my schedule on my phone. The capacity to do that didn’t exist before, so every day Alayne would provide a 3x5 card with the play-by-play schedule taped to it. If there was a change, she would substitute the card.

When I was out of the office, the staff member accompanying me or a member of the security detail would keep Alayne updated by phone as to whether we were on schedule, behind or ahead. That would allow her to be working ahead if adjustments were needed.

Security Detail

Under state statute, the governor is provided security protection by a special detail of the Utah Highway Patrol, referred to as Executive Protection. While emphasis is placed on the security aspect of their job, I came to understand that they actually served four important roles. The first, and most important, is security. The reality is, the governor and the governor’s family are routinely the subject of threats—some that law enforcement becomes aware of, others they do not. While most threats don’t amount to anything, it only takes one time for something to happen, so I was always appreciative of law enforcement’s thorough and conscientious protection.

The additional roles of the protective detail are less recognized but critical to a governor’s success. The security detail takes responsibility to transport the governor safely and expeditiously from place to place. They are also the communication link between the governor and the rest of government. It is absolutely necessary for various officials to communicate with the governor immediately, twenty-four hours a day. The security detail carried a dedicated phone that was in my presence constantly. In addition to communication, they provided other quasi-staff functions. For example, when staff was not available to advance an event, the executive protection officer would brief me on what to expect as I approached a venue.

Finally, while you won’t find it listed on a formal job description, the camaraderie my security detail provided was unforgettable and priceless to me. They became my friends; we shared many experiences together. They cared about me and my family, and I cared about theirs. I watched them grow in their abilities, their careers, and as people.

Initially I just accepted the people the superintendent of the highway patrol assigned. However, I quickly realized three things: First, I was going to spend a lot of time with them and therefore needed to be careful with my choice. I am not the kind of person who could treat them as invisible fixtures; they were part of my team. Second, I was going to depend on them and I needed people with the right skills to interact with the public and to carry out their tasks skillfully. Lastly, they were going to be interacting with my family constantly, and I could tell the troopers were going to have influence on them. I wanted to know who these folks were. So it soon became standard operating procedure that I was the final interview before anybody was assigned to executive protection.

While it was a different kind of duty than most of the officers signed up for at the Utah Highway Patrol (UHP), I think they quickly came to understand that it put them in a position to observe the operation of government, including public safety, from a very close view. They were able to travel the state, country, and world with all of the enrichment that comes with those experiences. I encouraged the leadership of the highway patrol to identify early career, high-potential persons and put them on the detail, because the job should be considered leadership training. The truth is, if you look at the leadership of the highway patrol over a period of years, it will become evident that many of the men and woman who emerged as leaders spent time on executive protection.

Eight or nine people served on “The Detail,” as we called it, at one time. Over the course of the entire period of my service, twenty-three people were assigned. I could fill a book on this topic alone—stories about our experiences, the interesting times we shared, and the friendships gained. They were almost uniformly positive.

When the detail and I were clicking, it was a well-oiled machine. They worked in teams of three: One would drive me, a second would advance the first event, and a third would advance the second. Once concluded with an event, the advance man on event one would move to advance event three, and so on in a rolling forward movement. In between events I was either preparing for the next event or making phone calls.

Modes of Travel

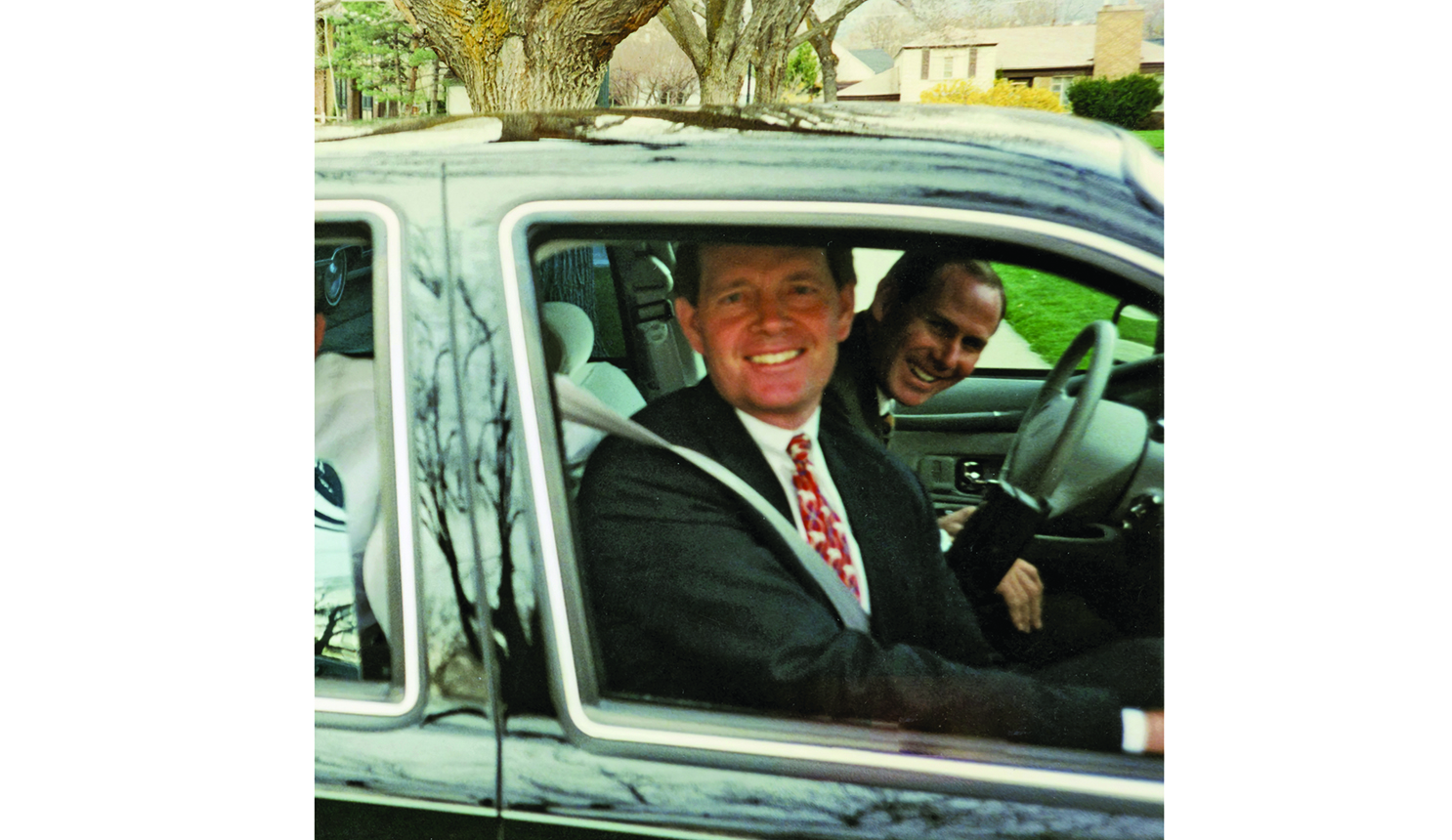

Every two years, the security detail would get a new car to transport the governor. They were part of a Ford Motors arrangement where the company subsidized a lease in order to have state chief executives traveling in their automobiles. Consequently, we drove Lincoln Town cars for most of the time I was governor. I loved the cars; they were roomy and comfortable. Generally, I would sit in the front seat, but if I had a lengthy drive, I could spread out in the back seat, making it into a mobile office. Or, on occasion, I’d take a nap.

The state of Utah owned two aircraft during my tenure. Both were King Air planes, one a nineseater, the smaller one seating six. Before State Aeronautics bought the smaller King Air, they flew a twin-engine Beechcraft Baron. I used the airplanes a lot, for both in-state and out-of-state travel.

What I really wanted the state to own was a helicopter. We could never have justified the expense just to transport the governor, but I knew it could save considerable time when making trips to Provo, Ogden, Park City, and the shorter in-state trips with greater road congestion. There were weeks when I could spend hours in the car driving. While I would try to make them productive, it was still transportation time.

After a few years in office, State Aeronautics was able to buy two used military helicopters. They were old. They looked like the helicopters on the television show M*A*S*H*, though they were painted to look nice. We started using them when they were not deployed on business. Why not? The pilots were just sitting around with nothing to do otherwise. It was great. I loved taking off from the front lawn of the Capitol. It wasn’t as dramatic as having Marine One pick you up on the south lawn of the White House, but it was close.

Truth be told, those old helicopters weren’t very safe, and I should never have flown in them. Both of them crashed in different incidents later. In one situation, the helicopter appears to have just broken apart. Regrettably, the pilot who flew me, UHP Sgt. Doyle Thorne, was killed in that incident.

Later, the state obtained two very safe and modern helicopters from the Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office. The helicopters had been donated by the Skaggs family because the family concluded they could not use them efficiently. I could though—and most enthusiastically did.

The use of the state plane was always a curiosity for reporters. Every year, somebody felt a need to do a critical report on the governor’s use of the plane. It always irked me.

One year we became aware that a young newspaper reporter was reviewing the State Aeronautics logs. Reporters never found anything, but always questioned whether it was legitimate for my family to fly on it with me. Or they would challenge whether we had reimbursed the state for the proper amount of a political trip. Always something, and always with innuendo.

The reporter continued to press for an interview. I resisted. Finally, I was persuaded by Vicki Varela that I needed to do the interview. I agreed to have her accompany me and ask questions while I did my exercise walk through Memory Grove. The reporter showed up in red cowboy boots. Yes, brand-new cowboy boots. As we walked, her questions became increasingly irritating. I thought, “Two can play this game,” and I just slowly picked up the pace. The new cowboy boots had to be killing her feet. To her credit, she just kept walking and asking. I just kept picking up speed. I’m a little embarrassed now that I got satisfaction out of it, but I did.

Flying on small airplanes is not for everybody. Jackie and one of my children are very sensitive to motion sickness, and there were many others who got sick when they flew with me. Routinely, I would invite people to travel with me in order to conduct business or to get better acquainted with them. If things got bouncy, we would have awkward moments. I was very sensitive to the motion sickness because of Jackie and did everything I could to relieve the discomfort and the embarrassment anyone experienced by getting sick in the governor’s plane—in front of the governor. However, there was one occasion, I have to confess finding the experience a bit satisfying.

I had flown to Bryce Canyon on a snowy spring day to address a gathering of the Utah Association of Counties. I found that a good friend of mine, Senator Scott Howell, had driven with a highway patrolman to Bryce Canyon so he could also speak. As we finished, I said, “Scott why don’t you fly back with me?” He readily agreed.

During the flight, Scott explained to me that his party was encouraging him to run against me. He told me it wasn’t personal, which I understood. However, he continued to press the point a bit.

As we were approaching the Salt Lake Valley, the air became very turbulent, and for nearly twenty minutes we were being bounced every which way. It was actually quite miserable. Just as we touched down, Scott lost it in a fairly spectacular way.

As we taxied toward the hangar, we were trying to clean up. I put my hand on Scott’s knee and earnestly said, “Scott, it’s like this every day.” He didn’t run for governor.

Using the Mansion

The Utah Governor’s Residence, or the Governor’s Mansion, has historically been the place of residence for the governor and family. However, the fire at the mansion on December 15, 1993, caused our use of it to be unique. We actually lived at the mansion for the first eleven months of our service, then spent nearly three years restoring it, and used it as a work asset the balance of the time. In this portion, I will discuss only our use of the mansion as a work asset.

Blair House is a residence within the White House complex of buildings in which diplomatic guests, particularly former heads of state, are invited to stay. For President Kennedy, it represented a neutral ground with major prestige that made people feel fortunate to visit. If he invited people to the White House, it was different.

For us, the Governor’s Mansion was a similar asset. I would often work there when I had meetings that required some degree of sensitivity and privacy. People could slip in and out of the Governor’s Mansion without feeling conspicuous. Sometimes it would be an interview or a session involving a request or tasking someone to do something specific. Doing so at the Governor’s Mansion made the experience more intimate and special.

Jackie worked there nearly every day, since the offices of the First Lady were housed at the Mansion.

It was also a place for us to entertain at our highest level. It’s a magical light show when the large table in the main dining room is set with china and the silver service from the U.S.S. Utah, and the settings and highly polished cherry wood in the room are reflected off the crystal chandeliers overhead. Guests always knew they had been invited someplace special.

The ballroom on the top floor provided a private venue we used to great advantage. Once, I needed to persuade the state’s police agencies to cooperate on a project. Had I invited them to the Governor’s Board Room, the conversation would have been combative. By inviting them to the Governor’s Mansion, it was dignified.

We regularly invited families to have dinner. For example, when we formed the Utah Foster Care Foundation, Jackie and I hosted dinner on two separate evenings for prominent Utah families. We ate in the dining room and then retired to the parlor to talk about how they could help the children of the state. A more dignified ask could not be made.

Often, we would invite guests to stay the night. On the night of my State of the State speech, we would invite important economic development guests to sit in the balcony. We would then go to the mansion for dinner and they would stay the night.

We had heads of state stay overnight. The Dalai Lama spent an entire week—an unforgettable experience. As was the Mansion itself. A magical place, and I loved working there.