48 minute read

Chapter 15

from Real and Right

Politics

I have Republicanism in my blood. My Grandmother Okerlund was treasurer of the Wayne County Republican Party for nearly fifty years. She often told me it was just fine if I married a Catholic, but she wanted it known that she would not be pleased with a Democrat.

By fourth grade, it had taken root. In 1960, I represented Richard Nixon in a school version of the Nixon-Kennedy presidential debates.

My father, Dixie Leavitt, became a Republican state legislator when I was in the sixth grade. So, naturally I felt it was a shot at me—and my dad—when a school principal made announcements over the public address system about the mistreatment of teachers by the legislature.

I would spend a week at the legislature with my father each year, and because of that, from high school on I was aware of current events and politics. And in college, for a class in which I had to write about a political figure I admired, I chose Tennessee Senator Howard Baker, a Republican who handled himself with dignity and competence as ranking minority member at the Watergate hearings in 1973. The first Utah Republican convention I attended as a delegate was a year later, in 1974.

It was in 1976, however, when I became heavily involved in the Republican Party. My father had decided to run for the GOP nomination for governor. As a twenty-five-year-old, I managed his campaign. His candidacy came much to the displeasure of party leaders, who had determined in their wisdom that another candidate, Attorney General Vernon Romney, would be the Republican nominee. Our campaign greatly exceeded expectations, finishing first in the state convention and forcing Romney into a primary. We came close in the primary but could not eke out the win. Through that process, though, I became a player in the Republican Party of Utah.

The campaign of 1976 triggered a long string of future campaign involvements. From 1978 through 1990, I managed the lead race in the state in each of the general election years, starting with Congressman Dan Marriott in the Salt Lake-based 2nd Congressional District. In 1980 and 1986, I led the two reelection campaigns of Senator Jake Garn. In 1982 and 1988, my efforts were devoted to Senator Orrin Hatch. In 1984, I spent nine months working on President Ronald Reagan’s reelection and helped get a new Republican governor, Norm Bangerter, elected. There were additional races as well, some in other states, others on specific ballot issues. Through it all, I was involved in the party’s most senior councils, both formal and informal.

Delegates and the Republican Party

All of that is background to 1992, when I was elected governor of Utah and, as such, became the informal head of the state party—wielding power above and beyond the party structure due to the gravitas of the office I held.

There is a special irony in that. From the beginning of my time in politics, I have disliked party politics. However, I quickly recognized that political parties have a function, and I well understood that I had to learn to navigate—and hopefully guide—those processes. Political parties are the mechanism for nominating candidates to public office, from the county and legislative levels up through congressional and statewide races. They have real power, though a surprisingly small group of people control them.

In Utah, the nature of the nominating process at that time made this particularly true. Delegates were elected in small neighborhood meetings— precinct caucuses—during election years and participated in nominating candidates for general election offices. The theory was that delegates could meet all the candidates, get to know them on behalf of their neighbors, and then attend a party convention to winnow the field. At the convention, only delegates vote, eliminating the less viable candidates. If a candidate for office gains the support of 60 percent of the delegates, he or she advances to the general election. If no single candidate received 60 percent, the top two vote-getters run against each other in a primary election.

The system, at least in design, has virtue. But the process assumes that the delegates are a cross-section of the population of people who have a Republican ideology or view of the role of government. During my time in politics, whether as a consultant or officeholder, I did not find delegates to be representative; they did not mirror the population of people who considered themselves Republican or even conservative. Three-quarters of the delegates tended to be men, and a large swath of them, I believe, held political views that were not consistent with the center-right ideology of the typical Utah Republican voter.

Some of the most active delegates were more interested in the gamesmanship of politics than the statesmanship of it. They adopted dogma over practicality. They formulated partisan purity tests that were assigned greater value than workable solutions to thorny problems where honest disagreement existed. The delegate system created a class of “party hobbyists” whose primary joy was winning at the game.

There is nothing ignoble about being willing to serve in a political party. Rather, it is a real public service. But I’ve come to understand that motive is a critical component in service. Service is selfless. Society often looks with suspicion on lobbyists because they trade influence for money.

Well, the political party equivalent of a lobbyist is a “hobbyist,” though I apply that label to a small group of obstructionists who love the intrigue of the party itself rather than the public good they claim to be doing. And, unlike lobbyists, they are unpaid volunteers.

The majority of delegates elected in party caucuses considered their job done once the election was over. However, a core of hobbyist delegates understood that in the off-years when a general election was not to be held, the party held an organizing convention, and it was there that the party chair and other officers were elected by the delegates. Generally, of 2,500 delegates, only 800 to 1,200 will attend. Getting the non-hobbyist regular citizen delegates to attend is often a challenge. They usually have better things to do on a springtime Saturday morning. If the regular citizen delegates don’t come, the hobbyists have great influence at the nominating convention and use the opportunity to implement policies and processes that protect their influence.

Regularly, factions of party hobbyists would conflict with one another. This was particularly true at the county-party level. It was not unusual to have party members suing others over rules debates. It was foolish and embarrassing. The worse it got, the less regular citizens wanted to participate.

Making the matter more complicated, at the party convention a central committee is elected. This is a group of about three hundred delegates who serve as a board of directors for the party, making decisions between conventions. The state central committee meets regularly. Consequently, only the most devoted of the party hobbyists seek to serve. Both the size of the group and the nature of their ideology makes them a very difficult group. This had a significant impact not just on the major offices but also the quality and ideology of the people who served in the legislature. It also required candidates to adopt fewer mainstream positions in order to qualify for the primary ballot.

In a future volume I will recount how in 2013 I organized a citizen’s petition drive and successfully changed Utah’s nominating system. But to understand politics in Utah during the time of my service as governor, it is necessary to understand the challenge the party presented and how important it was to have a party chair who could manage all these dynamics.

At the time I was elected, Bruce Hough was the party chair. Bruce did a fine job. However, when it became clear that he was not going to run for reelection, I actively recruited Joe Cannon, a savvy businessman, attorney, and friend who had run for the United States Senate unsuccessfully in 1992. As a candidate, Joe had mastered working with the delegates and come within a few delegate votes of getting the Republican nomination for U.S. Senate. He lost to Bob Bennett in a primary. Interestingly, Bob Bennett later lost his Senate seat when he was defeated by two newcomers at the 2010 Republican State Convention—an outcome that upset many Utahns, including me.

When we approached Joe about becoming chair, he agreed to do it, but only if I would help him make significant changes to the party structure. I was a willing participant. The goal was two-fold: get more regular Republicans elected as delegates and change the party’s constitution to diminish the capacity of a small number of ultra-right delegates to tie up the business processes.

I will not detail the efforts to get a better cross-section of people involved, but it was extensive. It included enlisting the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, asking them to urge their members to become good citizens, attend the party caucuses, and step up their engagement with the process.

Efforts to get the party constitution changed were even more colorful. The changes were relatively minor—for example, there were tweaks to the percentages used in appointing members to the central committee. Change-making required getting a super-majority vote at the Republican State Convention. But there was a shortcut. Only a simple majority of delegates was needed if the party’s central committee recommended the changes. For us, it was essential to go the central committee route; the difficult trick was getting the more rational members of the committee to attend.

I put my political team to work. They organized the meeting at a state facility behind the Capitol and called the delegates in my name, asking as a favor to the governor that they come. Many of these people had to travel from rural Utah, so it was not a casual request.

The rules of the party required a quorum be present for voting. We got enough people to reach a quorum at the beginning of the meeting. However, it became obvious that the hobbyists who opposed our proposals had a plan. They would ensure that the debate went on all day so that gradually members would become disgusted, give up, and leave. Once the number fell below a majority, a quorum no longer held and the meeting could be closed down.

The meeting started at 8 a.m. By late morning, people were beginning to leave. By noon, people were hungry and angry. If just a small number left, the effort would fail.

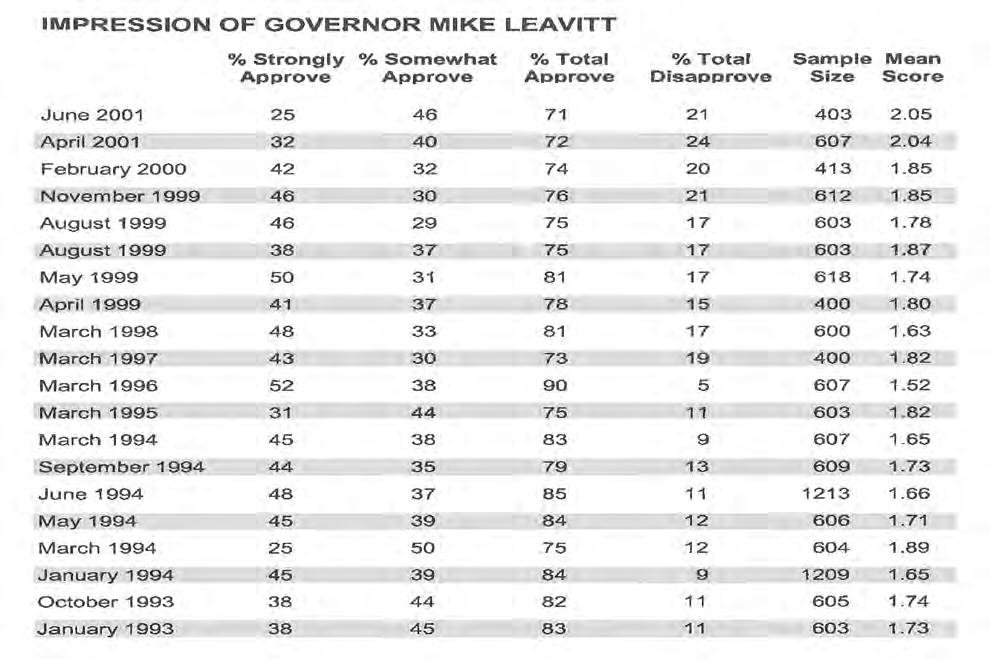

Do you have a favorable or unfavorble impression of Mike Leavitt?

There are three doors in the auditorium where we met. I asked the lieutenant governor to sit at the fire door. I asked the state troopers who provided security at the Capitol to secure a second door with instructions to ask those who tried to leave to use a different door. I placed a chair squarely in front of the third main door, and there I sat. Nobody was getting out of that room until we had voted. People were getting quite impatient. As they approached the door I would say to them, “If you have an emergency, you’re certainly welcome to go. But if you do leave, the obstructionists here will win and everyone who made the effort to come will have wasted their day.” People voluntarily stayed.

Finally, around 2 p.m. we had a vote, and the measure passed. At the state convention there was a similar amount of drama, though it was not necessary or possible for the governor to sit in front of the door. However, this episode demonstrates why it is so important to have strong leadership at the party level. It also illustrates the mentality of the ideological hobbyists that are attracted to party politics.

Political Health

Through the eleven years I was governor, people were gratifyingly supportive. I think that was in part because of the culture of Utah—we tend to sustain our leaders—and partly because of a strong economy. Then, too, people tended to agree with my policies and found our interactions acceptable.

Like any new governor, my first campaign introduced me, but it takes time for a public official to become known. Over time, you become well enough known that you begin to feel a relationship with every citizen in the state. You don’t know them personally, but people feel like they know you, and most folks had an opinion—one way or another. There is a familiarity exhibited that allows immediate connection.

Pollsters use a handful of questions to measure a public figure’s political health. One of the most common is the “favorability rating.” Specifically, it is phrased: “Do you have a favorable or unfavorable impression of Mike Leavitt?” And the question is expanded to list other officeholders or candidates as well. Each response is then pushed to establish the strength of the feeling. For example, if the response was favorable, the interviewer would ask, “Would that be very favorable or just somewhat favorable?”

My favorability ratings remained strong throughout my time as governor. They rose higher in the first few years and seemed to peak about midway through my second term. Toward the end of my time, three factors began to weigh my numbers down. The first was Olympic controversies, written about in a separate chapter. The second drag on ratings was a weakening economy. Lastly, over time a public person just accumulates “rocks in his backpack.” But all said, my favorability never got below 70 percent. To this day, I feel nothing but gratitude for being able to serve and feeling the sustaining support of so many Utah people.

The following chart was compiled by pollster Dan Jones on my behalf and lists favorability ratings each year of my time as governor.

Fundraising

For a host of reasons, governors are constantly fundraising. Not just for elections, but also for official duties where resources are needed, such as entertaining state guests at the Governor’s

Mansion, or traveling to events with a mixed political and official purpose. And all of these require non-public funds. Fundraising for a public official can be a very delicate matter because of the possibility of a donation being interpreted as an attempt to influence policy decisions. On a seemingly regular basis, a governor in the U.S. is convicted of criminal behavior because they let their guard down or stepped over an ethical line.

I feel nothing but gratitude for being able to serve.

I was grateful for the safeguards we had in place to keep a safe distance from anything that could be considered unethical. The first was a quite sensible law in Utah. Our state has few restrictions on how one can give money or how much. However, the law requires complete transparency. We were required to report publicly any donation to the state’s chief election officer within the Lieutenant Governor’s Office. Second, I had a staff who worked hard to avoid putting me in any situation that could be misinterpreted. Third, governors before me had established a method of fundraising that was understood and disclosed. It was a separate account called the Governor’s Gala Account by my predecessors and redubbed the Governor’s Special Projects Account during my tenure. Lastly, I simply felt no temptation to even come close to the line on this kind of thing.

We did fundraising mostly through events. Each year we held a Governors’ Gala, a large and somewhat lavish social event with entertainment and a meal. Some of the notable galas had well-known performing acts—the band America one year; country music star and actor Glen Campbell in another. At one gala, after the Olympics scandal had died down a bit, there was a humorous audience participation song about the Olympics “The Twelve Days of Scandal”—adapted from the “Twelve Days of Christmas.” That same gala also had a comic rendition of Harry Belafonte’s hit song “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” renamed “The Legislature Song,” and performed by sports broadcaster Craig Bolerjack and members of my security detail.

Besides the galas, we also held a corporate event each year called the “Cast and Blast.” It was held at my family’s ranch in Loa and became a favorite among attendees. During that period our family was operating a “rod and gun” club where members could fish in our private ponds and hunt pheasants in our fields. Both the fields and the ponds were managed to ensure success. At the Cast and Blast fundraiser, we recruited several governors to join me, and donors fished and hunted alongside them. It was what fundraisers call a high-dollar event. Each participant donated ten to twenty-five thousand dollars. The proceeds were shared among the campaigns who organized the event. One year, Governor Christine Todd Whitman came out from New Jersey. As an added attraction, the two of us put on a cutting horse exhibition, where a rider and horse work together to separate a single cow from a herd.

Lastly, each year, I would hold a golf tournament. All of these events were handled through the Governor’s Special Projects Account, with proceeds transferred to our campaign committees or whatever entity that was required. Both contributions and expenditures were reported quarterly.

We raised money to maintain and improve the Governor’s Mansion through an Artist Series we created. Every quarter we would honor a particular Utah artist at a ceremony, designating that person a “Mansion Artist,” complete with a beautiful medal. A group of about fifty patrons paid $2,000 a year to attend. The event was held in the Governor’s Mansion ballroom. During the renovation period, of course, we did not hold these. But when we did, they were lovely events. I really enjoyed the lift it gave Utah artists.

We had a wonderful team of people who year after year did the hard work of putting on events. Max Farbman was involved for nearly the entire time I was governor. He was mostly a manager of relationships. The people who really drove the process and made the events happen were Amy Hansen and Allyson Bell. They were joined by a group of volunteers who were extremely loyal to Jackie and me.

The Republican county party organizations financed themselves in major part by a Lincoln Day dinner. It was a well-known pattern and tradition. Typically, these had a guest speaker and a local party chair who felt it necessary to ask for brief remarks from a dozen officials. The aggregate always added to a very long night. After a few years, I quit trying to be at many of them. Sometimes Jackie would attend one, but always under protest.

Campaign Years

I did not have serious opposition in my first run for reelection in 1996. Democrat Jim Bradley, a Salt Lake County commissioner, decided to run. He is a fine man and a friend. The truth is, he never mounted a serious campaign. I had an 80 percent job approval rating at the time. Things were going well in the economy and otherwise. I won by a record margin, more than 74 percent. I won every county in Utah, something that had never been done before statewide by a Republican candidate. Charlie Evans managed the campaign, and my Governor’s Office team supplemented it heavily.

Leavitt is no shrinking violet.

The year 1996 was also a presidential election year. Because I had been working so closely with Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole via the Republican Governors Association, it was natural for me to support him for president. However, I waited until January 16, 1996, to endorse him because of my role as RGA chair.

Senator Dole stopped in Utah at the State Capitol for my public endorsement. He said some nice things about my role in negotiating Medicaid and welfare reform on behalf of the governors. He also publicly referenced a somewhat tense exchange we had on the phone a few months earlier over what the governors felt we needed in the proposed laws enacting the reforms. Dole told the Deseret News, “Leavitt is no shrinking violet. We’ve had some tough telephone conversations.”1 Dole had been obviously angry in the previous phone call with me, provoked, I believe, by a remark I made in the media. His follow-up comment was a way of saying he was over it and wanted to move forward as friends.

After the news conference, we held a legislative reception in the Capitol and then a fundraiser. I agreed to serve as Dole’s Utah chair.

Co-Chair of the National Platform Committee

Haley Barbour was chair of the Republican National Committee (RNC) in 1996. He was the finest leader the party had during my active involvement. A well-respected lobbyist from Mississippi, he had worked in political affairs in the Reagan White House and was a very savvy, affable, and folksy character. He understood the potential that Republican governors had as a group to affect national policy and so was heavily involved in brokering the full participation of governors with congressional leaders. Later, Haley ran for governor in his home state of Mississippi, where he served for two terms.

Haley called to ask if I would serve as a National Platform Committee co-chair at the RNC convention in San Diego. Note, there is no job I aspire to less than co-chairing the platform committee at a national convention. I had avoided those types of platform dramas regularly in my own state. I knew the RNC assignment would be a week of intense party hobbyists who saw this as a task of utmost importance to the nation, and thus would fight over every word. I also knew it would make virtually no difference in what actually happened.

The fact is, it did matter, but not for the reasons they thought it would. Ultimately, I agreed to co-chair the platform committee on the condition that I would be allowed to speak at the convention. The committee chair was Illinois Representative Henry Hyde, and I was co-chair along with Senator Paul Coverdell of Georgia.

Most of the document was written before the convention by a team at the national committee, but each state party nominated two delegates for the job. The experience turned out about the way I expected. Long debates during sessions, and then behind-the-scenes bickering and posturing on issues like abortion, immigration, and getting the United States out of the United Nations.

In the end we turned out an acceptable platform. It did not become an issue at the convention or in the election. The payoff for me was the relationships I built with the co-chairs and the party, plus the speaking slot during the convention.

Speaking at a national political convention is an honor. It is the highest forum a party has to offer. My selection made sense, in that I was chair of the Republican Governors Association and had paid my dues.

National Conventions are different on television than they are in the hall. The scene on the floor of a convention is pure chaos. There are thousands of conversations happening simultaneously with people moving about conducting personal political business. With the exception of the nomination speeches and a few other notables headlining the evening, nobody pays a bit of attention to who is speaking.

Generally, the conventions are televised at length on cable television, and a couple hours of prime time would be picked up by the major networks. I was assigned to speak at 6:45 p.m. on a Thursday night. That was just a little over an hour before the nomination of the candidate, so it was an excellent time slot.

I prepared intensely, highlighting the theme of federalism that I had become well known for. George W. Bush, who was governor of Texas at the time, introduced me.

I walked onto the stage facing the mammoth San Diego Convention Center. Fortunately, I had been warned about what I would face or it would have been quite disconcerting, and a bit ego deflating.

Nobody was listening. People were walking around, having loud conversations—it was a festival. The task was to speak to the television audience of two to three million viewers. I used a teleprompter, so things went just fine. However, it felt somewhat anticlimactic and, frankly, quite strange.

Yet my work done in the trenches did not escape notice. Right after the convention, Time magazine had a feature on the rising stars in the Republican Party. My name was among them.2

Since Utah was a reliably Republican state, Senator Dole visited Utah only once during the campaign. With my own election on remote control, I spent most of my time campaigning for state legislators.

The only real startling thing that election year occurred when Bill Orton, a Democratic member of Congress from Utah’s 3rd congressional district, was defeated. He was a victim of President Clinton’s creation of the Grand Staircase National Monument in Southern Utah earlier that year. Republican businessman and venture capitalist Chris Cannon, younger brother of Joe Cannon, won the seat.

Orton’s defeat would have an unexpected impact on my political life.

The 2000 Election

I never seriously considered not running for a third term. I liked the job, I was in the middle of preparing for the Olympics, we had I-15 all torn up amid a rebuild, and I was healthy politically. However, the election of 2000 did not turn out to be the cakewalk 1996 had been. The challenges came from the political right—within my own party. Plus, third-term elections will always be more difficult than second-term reelections.

Shortly before the legislative session of 2000 was to begin, I became aware that Republican legislators were actively exploring a campaign to nominate Speaker of the House Marty Stephens in a primary challenge. They had begun to sense some discontent in certain parts of my political base— primarily among the party hobbyist crowd and in certain parts of rural Utah. Although I was running very high approval ratings statewide among the general population, these two groups had some Leavitt fatigue and also felt a bit ignored. There wasn’t fire, but clearly there was smoke, and legislators smelled it.

I had taken positions on two issues that troubled these groups. One was my stance that a concealed weapon permit should not provide carte blanche to carry a concealed gun into a church or school. Second Amendment groups loudly and vociferously took issue with that position, although the National Rifle Association continued to support me.

The second issue related to my efforts to settle wilderness and road disputes in rural Utah with the federal government. I held the view then and still today that it is not in Utah’s interest to continue pretending that federal laws do not exist. I had been trying to resolve some of the long-standing disputes as opposed to litigating or militating against the federal government. They viewed that as capitulation on my part.

The New York Times previewed the gun contentiousness in a March 12, 2000, story by Michael Janofsky about three western states where gun initiatives were in the forefront—Utah, Colorado, and Oregon.

“In Utah, an effort to ban guns from schools and churches was a centerpiece of Governor Leavitt’s legislative agenda this year. After it failed, a coalition of groups, led by the Utah Parent-Teachers Association, organized to collect signatures to place an initiative on the ballot in November.”

The New York Times noted the difficulty in collecting signatures from ten percent of the registered votes in twenty of Utah’s twenty-nine counties, the minimum needed to get the initiative on the ballot. The article added: “Governor Leavitt, who is not expected to encounter any problems winning election to a third term this year, is taking no chances, nonetheless, letting others take the lead in campaigning for the initiative.”3

In the end, the gun ballot initiative effort sputtered, and the measure never made it onto the 2000 election ballot. But that issue, along with the public lands issues, foreshadowed a larger divide that I had not seen coming.

The truth of the matter is, I had simply not spent enough time in rural Utah. It was an important part of my political base, and for the first six years I spent a lot of time—more than any other governor in history—in rural Utah. The two years before the 2000 election, however, had taken considerable amounts of my time outside the state on National Governors Association business and other matters. I had simply lost touch with rural Utah.

My relationships with the legislature had begun to chill a bit, too. I’m not sure my perspective is still very good on why, but over time people wear on each other. I had become quite skilled at getting what I needed from the legislature, often taking my cause to the people.

Marty Stephens had become Speaker of the House after an earlier unsuccessful attempt. Though we were friends, he had lost the previous speaker’s election because some said he was “too close to the governor.” That was a factor in him potentially mounting a primary challenge for governor. At the very least, saying he was going to run against me clearly signaled that his purported closeness was not true.

There were people who wanted to move into legislative leadership, and if Marty stayed another term, it blocked more opportunities for them. Therefore, getting Marty to run for governor cleared a path for others to run for leadership. The rural disconnect that arose late in my second term also played out prominently within the legislature as well.

I was in Palm Springs, California, at an RGA event when the news broke that the Stephens forces were seriously considering a challenge. It caught me somewhat by surprise. I decided to call Marty directly to confirm it. We had a civil but tense conversation, and he said it was true.

This presented a very complicated situation. I could imagine going through the entire legislative session with this dynamic hovering over everything. I was also disappointed in people whom I considered friends, who appeared to be either involved or, at minimum, not standing up for me.

I knew no House members in their right mind would buck legislative leadership and support the governor. It would be awkward and viewed as disloyal. However, I could not show any weakness or it would trigger all kinds of difficult consequences.

We began working to solidify support from the business community, donors, and state senators who we knew would be offended by the House making a move on a Republican governor. The newspapers became full of intrigue and drama very quickly.

Marty ultimately decided not to run. I think three things contributed to his decision. First, he met with a group of donors led by my friend Dell Loy Hansen, who, in very direct terms, told Marty they would not support him, and that they were doubling down on their support of me. They told him it was disloyal and hurtful to the party, and that he should not get in. Second, the strategy of those who were supporting Marty was to take me out at the convention. They knew that if it got to a vote of the people, they would lose and not only would Marty not be governor but he wouldn’t be Speaker any longer. Finally, Marty and I have been friends for a long time, and I think in the end, it just felt too disloyal to him.

Despite Marty’s withdrawal, it signaled that we had entered a period of heightened tension with the legislature. The day after Marty’s withdrawal, it was the Legislature's Executive Appropriations Meeting, and he and three other Republican legislative leaders, Kevin Garn, Jeff Alexander, and David Ure grilled my budget director, Lynne Ward, for three hours over a roads proposal and tobacco settlement recommendations. It was obvious they wanted it to be clear that the legislative branch would be challenging the executive branch.

In reality, checks and balances in government require tension. I did not mind the tension because I felt it made us more productive. In fact, many legislators told me in subsequent years that our office was more proactive than other administrations. We made proposals, had opinions, and challenged the legislature for influence.

Do I have your vote?

In order to give the legislators a comfortable way to back down, and also solve some of the problems that were driving their discontent, I agreed to bring a former speaker of the House, Glen Brown, into my office to be an interface with rural legislators on land issues.

I welcomed a chance to work with Glen; he had been a great supporter of mine. He was disappointed in not being selected as head of the Department of Agriculture earlier in my administration, but we had worked through that. Glen pitched in and made a big difference in our office, mending our relationships with the legislature.

What would have happened if Marty had run?

As it turns out, the vulnerabilities the legislators sensed in important areas of my base actually existed. Those became manifest in the state convention just a few months later, when a virtual unknown received 43 percent of the delegate vote, pushing me into a primary election. It’s possible then, I suppose, that the legislators’ plan could have worked. Not many years later it happened to Senator Bob Bennett. Delegates, for reasons not substantially different, ousted him at convention, and his seat ultimately was won by Senator Mike Lee. While Bennett had approval ratings in the general public and among Republicans significantly below mine at the time, it really didn't matter. Even the public doesn’t matter at that point in the process— only Republican delegates matter. I knew I would have a major advantage in a primary. But I still consider the experience to be one of the more important political lessons of my life, and I was about to learn another one.

Convention 2000

I have always wondered why more people don’t run for governor or the U.S. Senate. For the cost of a filing fee—and that can be waived if you plead poverty—a person gets a license to speak at county conventions, be featured on television, and more. To a person with the right personality, it can be good, cheap fun.

In each election I’ve been involved with, there are people who file without a prayer’s chance of winning. However, that’s the way a democracy works. Some of them are characters, others have touching human stories. In 2000, there was a candidate named Tim Lawson, who would drag a ball and chain up to the stage with him and drop it on the floor to great effect at the beginning of his speech.

The Salt Lake Tribune had a funny column about one of Lawson’s stump-speech gimmicks. Lawson tried to work up the GOP crowd, claiming the Leavitt administration had increased the size of government, and then shouted, “Are we all Republicans?”

The crowd responded, “Yes!”

“Are we for smaller government?” Lawson asked.

“Yes!” yelled the crowd.

“Do we want lower taxes?”

“Yes!”

“Do I have your vote?” The crowd bellowed back, “No!”

Another candidate whom I admired was Dub Richards. He also ran in 1992. Dub had been injured in an accident and was paraplegic. His political ideas were not well formed, nor were they well delivered. He sounded almost delusional sometimes, but he ran—and worked hard at it. He would haul a few signs around in his specially-equipped van. He had no staff, volunteers, or even family that traveled with him most of the time. It was a very hard thing he was doing. It seemed evident to me that this was more about proving something to himself than anything else.

One night on the county convention circuit, we passed Dub changing a tire on the side of the road. That is nearly impossible from a wheelchair. We stopped, as did other candidates and staff, to help. There was a general appreciation for the fortitude he had.

So, when a handful of minor candidates filed in 2000, I thought nothing of it. One of them, Glen Davis, never showed up at any of the county conventions. He was simply absent from the race. I presumed he had changed his mind after having filed. However, on the morning of the state convention, he showed up, ready to participate. Literally no one who had been running that year had ever met him. Nor had any Republican Party official.

Glen’s family owned a novelties business called Loftus Novelties. I knew the store well. As a kid, it was a favorite place to visit on Main Street in Salt Lake City whenever I accompanied my dad during his legislative sessions. Over the years, Loftus Novelties had grown to a much more substantial business and the Davis family was well respected in their neighborhood and community. Glen is a smart and able man. He is also a man with strong opinions and the ability to express them.

He entered a state convention that was clearly in an angry mood. Because of inadequate security and poor management, several dozen hardline, non-delegate gun advocates had seated themselves in the front section of the convention hall—the E Center in West Valley City, later renamed and known today as the Maverik Center. It is impossible to know how many were there, but the Deseret News reported that some of those jeering at me and others may not have been delegates. “GOP leaders certified 3,500 delegates, but the hall had more than 5,000 in it when candidates gave their short speeches,” the newspaper reported.https://www.deseret.com/2000/5/7/19505290/leavitt-cook-face-primaries-br-both-are-booed-and-jeered-at-republican-state-convention

The anger felt in rural Utah about the federal government over land and road issues was palpable that election year, and I had become an accessible symbol of their discontent, as had Senator Orrin Hatch, also running for reelection that year.

At a Republican Convention, each candidate is allocated a specific amount of time. During that period, a nominating speech and a seconding speech need to be made. Following those presentations, the candidate speaks for the balance of the time. The candidate order is typically drawn from a hat or some other random process.

I was rehearsing my speech in a room offstage. My campaign manager, Amy Hansen, came to the room to report two things. First, that the convention was an ugly crowd—Orrin Hatch had been booed. It was shocking, she said. The second report was that Glen Davis, the mystery candidate, had given a fiery speech that was enthusiastically received by the convention. Lots of red-meat rhetoric. Neither was particularly good news.

When my turn to speak came, Jackie accompanied me. Normally, when a sitting governor with high popularity addresses his own party, one can expect a warm reception. This was not a normal day.

As I began to speak, it was clear there were two different crowds. Immediately in front of me was a large group of loud, disruptive men who were clearly there to demonstrate, mostly about guns and public lands. The second crowd was the normal convention group.

As they had with Senator Hatch, the group right in front of me began to boo, trying to disrupt me. Offended by this behavior, the rest of the crowd responded by trying to cheer me. There were people arguing in the crowd, yelling at each other to shut up. It was a horrible atmosphere. I remember very little about the speech except that I finished it and got off the stage. I retired to a nearby room to wait for the voting to occur.

The convention had adopted a multi-ballot process where the lowest candidate would be eliminated and delegates would vote again. Those who had voted for the eliminated candidate would then reallocate themselves to the remaining candidates. This also meant that the time dragged on. This time, however, there was no one to sit in front of the door to keep people from leaving. Many people cast their ballot the first time and left. The disaffected stayed.

The voting took a couple of hours. Finally, Amy Hansen returned. Her first words were, “Governor, we have a problem.” She went on to detail how Glen Davis had won 43 percent of the vote—which meant that I would be facing Davis in a primary election. Orrin Hatch had escaped the same fate by a handful of votes.

Governor, we have a problem.

The voting took a couple of hours. Finally, Amy Hansen returned. Her first words were, “Governor, we have a problem.” She went on to detail how Glen Davis had won 43 percent of the vote—which meant that I would be facing Davis in a primary election. Orrin Hatch had escaped the same fate by a handful of votes.

Situations involving unexpected news or disappointment tend to settle on me over time. I was concerned but mostly a bit angry. I knew I needed to face the media and manage the fallout as best as possible. I congratulated Davis, and said, “This is the way the process works. If one wants to be governor,” I said, “there are no shortcuts.” For the election, I would conduct a rigorous campaign, and I expected to win.

However, the next few days were rugged ones for me. I was angry, embarrassed, and hurt. It had come as a surprise, though it probably shouldn’t have. The Marty Stephens episode should have been a warning, and there were other indications I should have read differently. No matter, it hurt. Within a few days, the bruises began to heal, and I began to settle into the task at hand.

In its coverage of the convention, the Deseret News provided a bit of color commentary. “Delegates cheered when one county GOP chairman, during their ‘reports from their counties,’ warned the governor to stop ‘giving away’ land to the federal government. Leavitt has been working on wilderness and school trust land swaps with the Clinton administration.”

And this: “Nearly every candidate promised to defend gun rights—and all were cheered loudly. Leavitt has been criticized from his party’s right wing for advocating that all weapons, including legally permitted concealed weapons, be banned from public schools and churches.”5

I concluded first of all that I needed to understand what had happened and why. It was evident that I had political trouble in rural Utah and needed to get to the bottom of it. I asked my team to organize a series of meetings for me in a dozen rural communities. I wanted to meet with the people in those towns who had been my supporters and organizers. The meetings were all held in airport hangars. A group of chairs would be put in a circle. I would land at the airport and sit with my friends and listen. I would start the conversation by saying, “I need to understand what happened at the state convention, help me understand it, and tell me what I need to do to fix it.”

I learned three important things on that tour. First, that I still had friends in rural Utah. Second, they were sending me a message—they still wanted me to be governor, but they felt I had forgotten them. Third, the gun issue wasn’t about guns. It was about their frustration with government.

That third lesson was an important one for me. It crystallized during a meeting in the hangar at the Duchesne Municipal Airport. We took a break to snack on orange juice and donuts when one of the participants casually said to me, “Governor, you really need to understand this gun thing. I don’t think a person should take a gun into my house or have one at church.” The man then proceeded to explain to me how the gun issue was more about his truck.

His story was compelling. One day, he set about hauling a backhoe to a neighboring county to dig a trench. At a highway checking station he was told his truck was now a commercial vehicle and that he needed a commercial license. He got the license, which required him to submit fuel tax records. Amid the process of submitting fuel tax records, the U.S. Transportation Department notified him of a requirement to be drug tested.

“Governor,” he said, “I just wanted to dig a trench for a friend in Vernal. If they can do that to my truck, imagine what the government could do with my gun.” I realized then what the real issue was. I thought people were responding to a question about guns. People didn’t see the gun problem. What they saw—the true underlying problem— was government’s outsized impact on their lives. I immediately changed tactics when it came to gun issues. I never responded to a question related to guns without talking first about the threat of oppressive government. Once people knew I understood their concern about government, they were willing to listen to my logic on the gun issue.

I spent the next four months and nearly $600,000 in campaign funds repairing my relationship problems with my base. I traveled rural Utah extensively. I also instigated litigation against the federal government on a matter they had ignored, and I worked with core Republican leaders.

Governor, you really need to understand this gun thing.

Once the campaign was waged among the larger primary universe of voters, Glen Davis was at a disadvantage and I won handily. However, I had clearly suffered political erosion over the previous four years. In 1996, I won every county in a general election. In the primary election of 2000, I lost in some small Southern Utah counties that were symbolically important to me—Kane and Garfield Counties. In the general election, things normalized. My political base had sent me a message, and it was received. All in all, it was a very important lesson.

Incidentally, Glen Davis surfaced one more time before the general election. A few days after my primary victory, we made an appointment for Davis to meet with me and Rich McKeown at the Governor’s Mansion. Davis walked in with his campaign running mate, Greg Hawkins. There was a bit of tension, but we exchanged pleasantries. Glen started defining the election the way he saw it and then reached into his pocket and pulled out a piece of paper. I instantly surmised it was a list of conditions or some such thing, and I pulled him up short.

“Glen, if that’s a list of things that you want, you can just put it back in your pocket,” I said. “The problem here is you think this is about you. You think the race was about you. It wasn’t. It was about me. They were mad at me and I understand that. But I won the primary, and I’ll win the general.”

I continued to hammer home the themes that had carried my administration from the beginning: jobs, education, and quality of life.

I further told him that if this was a negotiation over his endorsement, I didn’t think much came with his endorsement. He and Hawkins left and Glen later endorsed my general election opponent, Bill Orton.

General Election 2000

I had an interesting history with Bill Orton, the former congressman who became my Democratic opponent in the 2000 general election. He had served as a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the same Oregon mission as me, but our paths had crossed only a short time.

Bill was an attorney and a highly independent and intelligent guy. Frankly, he was probably the best possible candidate the Democrats could have fielded. He had represented the Provo area and rural Utah in Congress for several terms—very notable for a Democrat. Moreover, he continued to be reelected in one of the most staunchly Republican congressional districts in America.

His initial win came after a strange miscalculation by the favored Republican candidate. The congressional seat was open that year. Howard Nielson, a four-term member of Congress, had retired in 1990. The vacancy attracted a dozen candidates in a very competitive race. Ultimately, Karl Snow, a respected BYU professor and former state senator, won a contentious primary. It was presumed that as the Republican, Snow would inevitably go on to win. Bill Orton, a single man in his mid-thirties, was the only serious Democrat that filed.

In the closing weeks of the campaign, an ad was placed in the Provo Daily Herald titled “Family Values.” There was minimal text; just a picture of Karl Snow’s large family—a Christmas photo showing several adult children, their spouses and a dozen or so grandchildren—with the headline: “Karl Snow and his family.” Next to the photo was a picture of Bill Orton, alone, with the words, “Bill Orton and his family.” The ad ignited a firestorm of anger within the community, which cascaded over the final week of the campaign, resulting in an amazing defeat of Snow in the most Republican district in America. Bill Orton won by 22 percent. It was nearly unthinkable in the 3rd district of Utah.

To survive politically, Congressman Orton had to cut a centrist path ideologically and regularly buck the Democratic establishment. People in Utah liked Bill’s somewhat maverick reputation.

Orton continued to be reelected until 1996, when President Clinton, in a surprise announcement, declared a 1.7 million-acre swath of southern Utah as a national monument. The people of Utah, and particularly Bill’s district, were outraged. Though Bill quickly protested the monument and did everything he could to distance himself from the controversy, he was toast. People still liked Bill personally, but they wanted some way to retaliate. Un-electing a Democratic congressman seemed like the only option available. Bill lost the 1996 race to Chris Cannon. However, people in rural Utah liked Bill, and given that they were a little bit grumpy about my efforts to settle some of our disputes with the federal government, having him as an opponent had the prospect of being problematic.

Bill Orton was a tough opponent—better than any I had faced up to that point. He was an effective debater, came across well and pulled no punches. He had married several years earlier—to a woman also named Jackie—and they had two children.

While not well resourced, Orton attacked continuously on issues where I would be naturally vulnerable. He went after the Olympic scandal, trying to link me to that. He resurrected a controversy over a whirling disease episode at our family’s fish farm, sending a person wearing a fish costume to follow me around at various campaign events. Their campaign called the character “Whirlie.” I thought it was a clever tactic. For the most part, we ignored Orton’s attacks. He didn’t have enough money to hurt me very much, so we monitored it closely and responded quickly when necessary.

I continued to hammer home the themes that had carried my administration from the beginning: jobs, education, and quality of life. Of course, I now had a record to point to and defend.

At one point my support among men had begun to fade. My two primary consultants, Eddie Mahe Jr. and Chuck Sellier, gleaned from polling that there was a need to give male voters a proactive reason to vote for me—an energizing or galvanizing issue. We focused on my opposition to the Goshute Tribe’s proposal to store high-level nuclear waste on their reservation that was close to the Salt Lake metropolitan area. We recorded a series of rather hard-hitting radio ads on the issue. Those were effective, and in short order my support ticked up among men. In the end, I was reelected comfortably, winning with 55.77 percent of the vote to Orton’s 42.27 percent.

Sadly, Bill Orton was killed in an ATV accident at Little Sahara Sand Dunes in 2009. Election periods are inherently adversarial, but Bill and I seemed to never take our political contest personally. While we didn’t spend time together before or after the election, I felt that we had a respectful friendship.

The 2000 Presidential Election

The year 2000 was also a presidential election year. I was an early supporter of Governor George W. Bush, the GOP candidate that year. In fact, I was with him in Israel during a time when he was deliberating whether to run for the presidency. In the fall of 1999, most of the Republican governors endorsed Bush, giving him an early boost.

My friend Orrin Hatch, who had always felt he was somewhat destined to run for president, concluded he, too, would enter the race. That obviously presented me with a problem. I was running for reelection. One of the issues was that I was spending too much time on national issues. It was evident that Orrin didn’t have a chance from the beginning, but it would be insulting if the governor of his state, his former campaign manager, didn’t support him. I talked to Bush and his team, told him that I was not withdrawing my endorsement, but that I would need to speak encouragingly of Orrin. They understood. I basically told the media that I supported both of them, and if it came down to a contest between the two of them, I’d have to decide then. We all knew it wouldn’t. Early in the primaries, Orrin dropped out.

I agreed to chair the Bush reelection in Utah. My deputy chief of staff, Vicki Varela, became the western states chair for the campaign. However, our first priority was my reelection.

All but assured of Utah’s support, Bush only came to the state a couple of times, once to raise money, another time for an airport rally. It was fun to see a friend rise in national politics that way, and to ponder the thought that my buddy George W. could very well become president of the United States.

The presidential election came down to a historically close race ultimately settled by the Supreme Court in a battle over who won Florida. It was a historic moment.

Shortly after the Supreme Court issued rulings that effectively declared George W. Bush the forty-third president of the United States. I flew to West Texas to visit the president-elect at his ranch, along with a number of other Republican governors. It is a working ranch about an hour outside Waco. George wanted to show me the ranch, so we drove the entire property in his pickup truck. His truck was light violet in color, and I poked fun at it, asking, “Who decided on the color of this truck?” “Mikey,” he replied, “It takes a real man to drive a purple truck.” Enough said. As we drove, George pointed out trails he had been clearing so that he could ride his mountain bike and run.

We went by the construction site of a ranch house George and Laura were building. They wanted it to be an environmental showplace. Water was drawn from collection cisterns; the cooling system was supplemented by natural design features so that breezes would cool the entire home; a private fish pond was being built next to the house. George seemed genuinely pleased to be showing it. The Secret Service had already begun construction on facilities they would need, including a helicopter pad.

That year, I was able to watch the election of a president in unique ways. On our trip to Israel, I saw him being recognized for the first time as a potential world leader. We spent time talking about the decision he faced. I witnessed the campaign, visited him at the ranch as he prepared to take office, and then to top it off, I participated in the electoral college.

During the same Republican convention where I was booed and pushed into a primary, I was elected to represent the state as an elector. This was a special year to do so, being one of the rare times in U.S. history that the ultimate victor—Bush— was elected despite getting fewer popular votes than his opponent, Al Gore. The entire nation was schooled on the electoral-college process outlined in the Constitution as we waited for the Supreme Court to rule on the election.

On the day designated for the electoral votes to be cast, Utah’s four electors gathered in the Governor’s Board Room. It was like casting a mail-in ballot today. The ballots had been printed and specially sent to the Lieutenant Governor’s Office. We ceremoniously marked our ballot, placed it in the special container provided and sent our votes to Washington.

That year I also attended the inaugural ceremony, sitting just behind the official party. All the governors were invited to sit together. It was bitter cold, but a wonderful celebration.

Footnotes:

1. Bob Bernick Jr., “Dole Gets Endorsement from Leavitt,” Deseret News, 16 January 1996. https://www.deseret.com/1996/1/16/19219591/dole-gets-endorsement-from-leavitt

2. Time, “Rising Republicans,” vol. 148, 19 August 1996, http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,984995-1,00.html

3. Michael Janofsky, “Citizen’s Groups Pushing Gun Initiatives in the West,” The New York Times, 12 March 2000. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/03/12/us/citizens-groups-pushing-gun-initiatives-in-the-west.html

4. Bob Bernick Jr., and Edward Carter, “Leavitt, Cook face primaries; Both Are Booed and Jeered at Republican State Convention,” Deseret News, 7 May 2000. https://www.deseret.com/2000/5/7/19505290/leavitt-cook-face-primaries-br-both-are-booed-and-jeered-at-republican-state-convention

5. Bob Bernick Jr., and Edward Carter, “Leavitt, Cook face primaries; Both Are Booed and Jeered at Republican State Convention.”