22 minute read

Chapter 17

from Real and Right

Staying Close to People

The first governor of Utah I ever met was George Dewey Clyde. I was an eight-year-old Cub Scout, and our den paid a visit to the El Escalante Hotel in Cedar City to see Governor Clyde, who was conducting business in Southern Utah that day.

I have no idea why he was in town; he was possibly just meeting with citizens at large. I do remember waiting in an outer office for a long time and then being ushered into another room where we met the governor. I have little memory of any conversation that occurred, but the man and the moment were not lost on me. It simply felt significant that he was a governor.

I often thought of that meeting during my own time in office as I met Boy Scouts and other citizens. I also recall the framed retirement certificates hanging on the walls of both my grandfathers’ houses, acknowledging their years of service as public employees. The certificates were proudly displayed because they were signed by the governor of Utah.

Those memories underscored for me the impact and significance of the office, the highest public office in Utah. No matter the party affiliation or even the personality of the individual serving, society bestows social importance upon the office itself, an air of gravitas beyond even the officeholder’s legal authority.

Offering Advice

Early in my third term, a newly elected governor from another state and his wife flew to Salt Lake City to spend the evening with Jackie and me. They confided that they were struggling with the public role of being governor. He said, “I feel like I’m trying to act like a big shot and it makes me uncomfortable.”

With more than eight years of experience at that point, Jackie and I felt capable of providing some insights. “Governors are not just a formalized state legal power,” we said, “They are guardians of a franchise brand: The Governor. There is only one at a time in each state.” We suggested the two of them think of the role as that of a “public symbol.” “It has very little to do with the individual who is the governor and everything to do with the role itself. Rather than be embarrassed by it,” we said, “think of it as an obligation and a great privilege. A way, like few others, to uplift or bless the lives of people.”

Rooster today, feather duster tomorrow.

People like to stand by the public symbol and have their picture taken. They like the governor to turn up at their event, because if the public symbol is there, it means the event is important. People feel free to say things about the public symbol that are unfairly harsh. And sometimes they ascribe far more virtue or power than exists.

Early in my service, I realized that as governor I could “minister” to people in a secular sort of way. I could raise their spirits, cause them to think, increase their self-esteem. When the designated public symbol takes an interest in you, it’s an important moment. People put pictures taken with you and letters from you on their wall. I often likened it to having “magic dust” in my pockets, which I could sprinkle around and make people feel better. It’s a nonstop supply of magic dust, up until the day you leave office.

I’ve also observed that the opposite can be true. A governor can fill his or her pocket with coal dust, and when he or she sprinkles it, it will make everything black. So there is a unique opportunity and an obligation that falls to a governor—and others with celebrity.

It should never be taken for granted, since it does indeed vanish or subside dramatically almost instantly upon leaving office. An old Australian proverb gets it right: “Rooster today, feather duster tomorrow.”

Having positive contact with people is not only an important way to provide service—it is essential to governing. Power to govern in a democracy comes from having the support of the people. The public supports and follows those it likes or at least respects, so being likeable and respected builds the capacity to get things done. This is among the most important potential advantages the leader of the executive branch has over the legislative branch. The governor has a personality, while the legislature has only a collective brand, generally negative.

Here is a good example of what I’ve been saying. I was at the Allen & Company Sun Valley Conference one year, and I met the actor Tom Hanks. We’d never met before, but I felt that as a fan of his movies we had something of a connection. I was a bit put off when we greeted each other and he didn’t seem quite as pleased as I felt. It was an important reminder that within Utah, my being the highest-ranking public object meant most people felt they had a relationship with me. I needed to convey warmth, or they felt discounted. Hanks struck me as having no such connection to me as a fan.

For my part, the warmth factor remained important, and there are lots of small nuances one learns to help with this. For example, I quit saying, “Nice to meet you” and replaced it with, “Good to see you.” If we had met before, the “Nice to meet you” greeting was interpreted as, “You’ve forgotten that we know each other.”

One learns the value of calling people by name as well. In many situations it is overly familiar, but if you’re the public symbol people feel reinforced in their relationship. I learned from George W. Bush the value of mentioning people’s names in a microphone. He often just recited a list of prominent people and friends compiled by staff. Still, it is always important when the president of the United States, the ultimate public object, says your name.

Likewise, the power of appropriate touch, such as a handshake, is important to understand. When combined with looking people in the eye and a nanosecond’s pause, the person will feel a connection.

Utah Parades

Jackie and I attended lots of parades as one way to connect with the people of Utah. My favorites were the smaller parades, like the Bountiful Handcart Days celebrating the July 24th Pioneer Days commemorations. Many communities have fruit-and-vegetable-themed parades, traditions that likewise date back to pioneer times when earlier Utahns began celebrating the harvest or a county fair. Utah has Peach Days in Brigham City, Onion Days in Spanish Fork, Strawberry Days in Pleasant Grove, and many other celebrations in different cities, some with and some without parades.

Then there is a class of parades that are megaevents unto themselves. Utah has two: the Days of ’47 Parade in Salt Lake City celebrating the July 24th state holiday, and the July 4th Parade and Freedom Festival in Provo, celebrating America’s Independence Day. Both of these draw over 300,000 people and statewide television audiences.

By the time our public service had concluded, Jackie and I had turned parades into an art form. We learned to use them as personal interactions with thousands of people rather than an impersonal display of two people in the back seat of a convertible.

We proactively engaged people with contact, which could come in several forms. I learned to segment crowds by looking slightly ahead of the car, choosing a person or a small, connected group of people and engaging with them. Eye contact was critical, and was made even better, if possible, with conversation. I would attempt to get a response from whoever I was engaging with at the moment. Quickly, the people around them would become engaged in a light conversation. Often, I would see people I recognized. If the governor calls a person by name in a parade, it gets attention and provides a nice moment for the person. I would then look ahead another short distance and repeat the process. If Jackie was with me, she would engage the other side, but periodically we would share exchanges with the same people.

I found it important to leave the car at various times during a parade and actually mix with the crowd. The security detail wasn’t crazy about that, but in reality it was never a significant problem. I would shake hands, bend down, and talk to a child or adult. Often I would move to the other side of the street and do the same thing. Parades always stop for periods of time, so rather than sit and wait, I found this to be a great time to engage people.

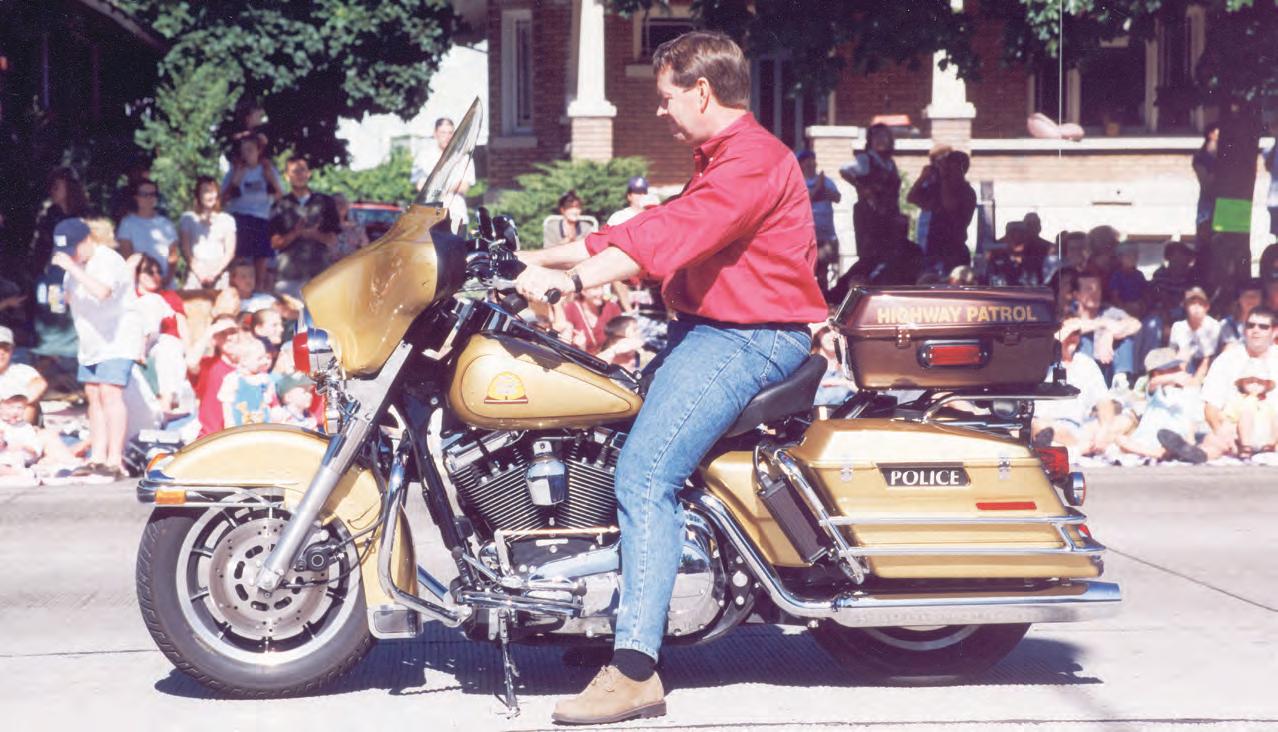

Early on in our service, I began engaging the Highway Patrol Motorcycle Squad. This was a special unit of highway officers who rode Harley Davidson bikes and did different formations and drills as they rode down the street. They made a lot of noise and used their sirens, creating a lot of excitement and commotion around our car. Often, I would signal a highway patrolman and change places with him. He would sit in the backseat of the convertible with Jackie, sort of awkwardly waving, and I would ride his Harley. It got so I could do some of the simple drills they did. People loved it, and so did I.

My favorite parades were the ones where I could walk rather than ride. I would never stay in the middle of the road but rather move from side to side, talking with people as I walked. It felt much more intimate and people were always responsive. One year in the Bountiful Handcart Days parade, it started to rain in a massive downpour. It was a beautiful, warm summer rain, and the crowd just stayed put, so we just kept walking. Crowd and participants alike got soaked. But it was like a giant party where everyone had the same exuberant experience—perhaps one of the most memorable parades ever.

Often, I would wear cowboy boots and a big cowboy hat in parades. One year, I was working the crowd as the parade moved along. I walked by a couple of adolescent boys sitting on the curb, and as I passed, one of them said, “So who are you?” I responded, “Who do you think I am?” One boy looked at the other, and then at my cowboy hat. He guessed and said, “George Strait.”

I enjoyed the really small-town parades. In many of them, there were more people in the parade than watching the parade. The parade would even go one direction down the main street and then do a U-turn so the people who were in the parade could see each other.

Perhaps one of the most charming parts of parades like that was the tradition of throwing candy to the children. It was like a combination of Halloween and the 4th of July, because every entry tossed wrapped candy. One particularly interesting twist on that theme is in Kamas, Utah, where the parade entries toss out candy on the way down the streets, and then parade viewers on the side of the road throw it back at the parade entries as they return.

“Let Me Speak to the Governor”

In the beginning of our service, I found it hard to turn things down. A governor gets multiple event invitations every day. I wanted to be accessible and to do a good job, but it became quite evident that being selective was a necessity if one were to have any life at all as a family. I realized I needed to find ways of communicating with large masses of people electronically.

Dale Zabriskie was executive director of the Utah Broadcasters Association, which represented the state’s radio stations. Dale suggested that we assemble a radio program once a month for an hour where I would take telephone calls directly from listeners. I readily agreed.

Dale assembled seventeen radio stations throughout the state who would carry the program during evening drive time, ensuring a very large audience. I don’t know the estimated size, but it had to be measured in tens of thousands. The stations would rotate having their personnel host the show. I did the show nearly every month for at least ten years.

We called it “Let Me Speak to the Governor.” I wanted the hallmark of the show to be both engagement and action. So it was not just an opportunity to talk with the governor—you could bring us a problem, and we’d get something done. I had every cabinet officer agree to stand by their phone while listening to the program. If a question or problem came up that involved their area, I would listen carefully to the caller’s question or request and either answer myself, or ask the caller to continue listening, and we would get an answer before the program was over.

Typically, we would handle twelve to fifteen calls per night. Sometimes the issues they raised were policy matters. Other times they were personal. I had people call about abuse they were experiencing. Prisoners called from jail. Complaints about roads, state services, or other branches of government were lodged. Not only did the program help me stay connected with people, it was a wonderful way to know what was on their minds.

As the program matured, we began to hold it most frequently at KSL Radio with Doug Wright as the host. He is very good in that format, and we acquired a rhythm that both of us seemed to enjoy.

The program worked so well that we decided to try a similar effort on television. At first, we did it at an independent station owned by the Larry Miller family, with Spence Kinard, a former news director at KSL television, as the host. The show was well done. On one occasion, the station arranged to do the show from our ranch in Loa. They sent a satellite truck and we set up chairs on the ranch house lawn. As the sun went down and the familiar shadows crept across our farm fields, I answered viewer questions. It was a unique show. The station changed hands and we moved the show to KBYU, where David Magleby, a political science professor, took over host duties.

Because KBYU was an educational television station, students managed and produced the program. The program was conducted in a very business-like manner and provided good information. However, the combination of live television and students at the controls produced some hilarious moments.

Television and radio stations often use a seven-second delay system. This allows them to preempt any unanticipated problems from being broadcast to the public. For the first several programs, KBYU did not have such a system in place. David Magleby would simply push a flashing line on a phone, and just like that the caller would be speaking to us and thousands of listeners. It wasn’t unusual for people, usually students, to call with something a little edgy. It was David’s job to manage those situations.

One evening, a caller said, “I would like to talk about sales tax collections. But before I do, I want to tell you about a new technology that allows one to mind-meld with Howard Stern’s genitals.”

David lurched for the phone to cut the caller off. To do so, he hit another flashing light on the phone to get another caller, catching the person next in line by complete surprise. The new caller, a man who seemed to be in his sixties, had been listening to the previous caller and was obviously talking to his wife. “. . . I don’t know,” he said, “it was something about Howard Stern’s genitals. . .” David lurched for the phone again, this time accidentally hitting an intercom button that led to the control room of the station. There, student producers were panicking, realizing that two references to Howard Stern’s privates had just been broadcast over the airwaves. A student producer said, “Oh shit!” This, too, was broadcast.

By this time, I was unconstrained in my laughter. We had to take a commercial break to compose ourselves and start again. Needless to say, by the next program, a seven-second delay system had been installed.

On another show, we got a string of just goofy questions. The last question put us over the top—a woman called asking me to intervene in a situation with her car-repair shop, which had charged her for an oil change she hadn’t ordered.

I glanced at David and noticed that the corners of his mouth had begun to quiver as he tried to restrain laughter. That triggered the same impulse in me. Suddenly, almost without warning, both of us were on live television laughing so uncontrollably that neither of us could speak. David would get two or three words out and we would both be compelled into an even deeper laughter. This went on for more than sixty seconds, which is eons on live TV. By this time, we both had tears of laughter rolling down our cheeks. Finally, I managed to say, “David, I believe we need a break.” The producers cut and went to commercial break. We fought to regain our composure and were able to finish the program. However, to this day, David and I break into the same uncontrollable laughter whenever we talk about this experience.

Visiting Schools

During my first campaign, I made a commitment that I would stay close to education. Without thinking about the logistical challenge and time commitment that entailed, I pledged to visit a school every week. I later reshaped the promise to include the words, “on average,” in order to cover me when I couldn’t get to a school in a particular week. And during my first term I kept that commitment.

It actually turned out to be a very helpful process. It did keep me in touch with schools and also provided me with an ongoing platform on education. I discovered, too, that we could make it into a wonderful way to touch a community.

I realized fairly soon that although the kids liked our interactions and I got more skilled at talking with them, we needed to attract more adults to the schools. So we developed a means by which the parents would be invited to attend, and then we provided materials—or “leave-behinds”—that the children carried home. If people in a community didn’t attend, at least they knew I was there. In the years since I was governor those children have grown into adults. With some frequency one will say to me, “You came to my school.” It was for them the same experience I had with George Dewey Clyde as an eight-year-old cub scout.

One of those instances was at an event featuring Tony Finau, a prominent PGA golf professional. Seeing me in the crowd he noted, “Governor Leavitt is here. He came to my school in Rose Park when I was in elementary school.”

Interestingly, I remember my visits to elementary schools in Rose Park. There were lots of Hispanic and Polynesian kids sitting on the floor in front of me. At the time, I remember thinking about what these children would be like as adults. I hoped my visits communicated their importance.

Being in touch with people is not just about public relations. It is the only way you stay in touch with problems. I had many experiences that were valuable in helping me understand the difficulties that play out in children’s lives and how schools are often at the epicenter of those dramas.

At a school in central Salt Lake City, I had just finished a student assembly and was walking toward the door when a small boy, probably a second-grader or close to that age, began to talk to me, tears streaming down his face. I stopped and knelt down so I could hear him and understand what was wrong. I said, “Are you okay?”

“No,” he said, “It’s my mom. They won’t let me see my mom.” He began to weep uncontrollably.

I put my arms around him and said, “Let’s go see if we can figure this out.” I took the boy to a teacher and related to her what had occurred. She whispered to me that the boy had been removed from his home by Child Protective Services, workers and was distraught over it.

It was evident that this little boy didn’t know what to do, but he saw somebody that was supposedly important, and in desperation he had reached out to me. Before I left, I knelt down again and thanked the little boy for talking to me. He had by this time composed himself. I promised him that the people who were working with him and his mother wanted them to be back together and said I would check to make sure they did their best.

It would have been inappropriate for me to intervene in the situation; I had to have confidence in the people handling the case. But I left that day with a different perspective on child welfare—the perspective of a child.

On another school visit, this time in West Valley, the children, probably third or fourth graders, were sitting on the floor of the gym listening to a program. To mix with them, I sat down on the floor next to some of the kids and began talking with them. One young Hispanic boy hadn’t said anything, so I tried to engage him by asking how he liked school. He did not respond. I tried two or three additional questions, but still no response. Finally, one of the other children then whispered in my ear, “He doesn’t speak English.”

“ I miss the enhanced capacity to minister to people individually, and to have a relationship with every citizen of the state, no matter who they were or whether we had met formally.”

Afterward, I spoke with the teacher. She told me that the child had been enrolled in their school several days earlier. He was from a migrant family who was in Utah temporarily. She said, “This happens all the time. He’ll be here a few weeks and then he’ll just disappear as the family moves on. We just do the best we can while he is with us.” Through experiences like that, I became more sensitive to the dilemma faced by teachers, students, and families.

In another elementary school visit, this time in the Rose Park area of Salt Lake City, I visited a school where nineteen different languages were spoken and more than a third of the students had a parent in jail. It’s hard to understand this kind of problem until you see it firsthand.

I also witnessed great things. I remember a special program I visited at a high school in Utah County where they had integrated art, history, and English into a three-hour class. Students studied history, but also wrote about it and created works of art to help them learn artistic skills. It made the lessons of history dynamic for them. When I was there, the teacher had given each student a roll of paper calculator tape and had the students sketch depictions of each historical event they studied. Their final exam was to review their tape with the teacher and recount the details of the events they had studied. I was inspired by what I saw. I would have loved learning that way.

As it turned out, visiting a school a week not only helped me stay in front of people, but it was one of the most productive learning experiences I had. I continued to visit schools during my second and third terms. Over the course of my service, I’m sure I visited a meaningful percentage of the schools in Utah.

Another important way we found to maximize the Governor’s Office as an influence for good was to participate in public service campaigns. Both Jackie and I did this often. I did television and radio campaign messages for water conservation, carpooling, anti-smoking, and drug abuse. These campaigns moved the community in ways we believed were right. At the same time, the frequent engagement built a strong relationship with the people of Utah.

Some years following my service, the Western Governors’ Association invited me to attend their annual meeting to reflect on how to continue making a difference after one’s time as governor had concluded. Someone asked what I missed most about being governor. My answer was unequivocal. “I miss the enhanced capacity to minister to people individually, and to have a relationship with every citizen of the state, no matter who they were or whether we had met formally. If the governor tells a thirteen-year-old they did a good job, it lifts them. If the governor listens in a way that causes a person who is suffering to know they have been heard, it provides a sense of relief.” I went on to tell them it is instances where you use your personal capacity to affect people that will be your most poignant memories, not the exercise of constitutional authority. And so it is for me. Being governor of Utah was singular privilege because it put me close to people.