1 CHAPTER #

Copyright © 2021 Michael O. Leavitt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reveiwers, who may quote brief passages in review.

ISBN: 978-1-68564-073-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021921581

Publisher: Lairdhouse Trust

Permissions: Deseret News, The Salt Lake Tribune

Disclaimer: The author and publisher take no responsibility for any errors, omissions, or contradictions which may exist in the book.

Cover Photo: Chris Curtis, Shutterstock

Writer: Michael O. Leavitt

Contributing Writers: Laurie Sullivan Maddox

Editor: Megan Anderson

Designer/Production Coordinator: Roxanne Bergener

Special thanks to:

• Paula Mitchell, Special Collections Librarian, Gerald R. Sherratt Library

• Utah State Archives

• Ellie Sonntag, Mansion fire restoration

• Anna Daraban, The Salt Lake Tribune

First printing October 2023

In Service as a Family

VOLUME 4

The personal history of Michael O. Leavitt

Preface

I am a westerner. My hometown is Cedar City, Utah, where I was raised with my five brothers by two loving parents. Time, place, and purpose all begin there..

My forebears had become westerners in the mid-nineteenth century. The Okerlund branch of the family settled in Loa, Utah, while the Leavitts put down roots in Bunkerville, Nevada. One of those ancestors was Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt, who in an unpolished hand wrote down an overview of her life in six pages. Her story describes her conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the persecutions she suffered as a result. She experienced the loss of child and spouse, hunger, exhaustion, freezing cold, searing heat, and a journey both on foot and by handcart to settle this western home of mine.

Sarah’s essay and others on both sides of my family, close and distant, not only inspired me—they stirred an innate feeling of duty to capture what I have experienced and learned. Through genealogy, geography, faith, and affection, I am a westerner because of them.

So now I have concluded seven decades, it is my turn to add chapters to the history of my family, church, state, and nation. I do so with the aspiration that my reflections will offer similar benefit to future generations. Because of my forebears, my life has been much different than those gritty ancestors of mine. I have visited every continent; interacted with kings and presidents; come to know the poor as well as the powerful of the world; and witnessed historical events both triumphant and tragic—none of which would have occurred without my forebears’ sacrifices, goodness, and endurance.

Life and leadership are a generational relay. In fact, the compelling need I felt to write this personal history may have been driven by a desire to discover for myself whether my contributions met my obligations.

A personal history falls on a continuum of candor somewhere between a journal and a published autobiography. It is not a substitute for a journal that records the activities from each day, whether important or trivial. However, it provides the luxury of length and the inclusion of whatever I want to recount.

2

Volume IV: In Service as a Family

Volume IV turns the focus onto family, with a central question: How did my service as governor affect each of them? When I was elected, Jackie’s and my five children ranged in age from two to fifteen years old. Jackie was thrust into a whirlwind of new expectations and duties, her life no longer her own in many ways. My entry into public life had a profound impact not just on us, but on our parents, my brothers, and her sisters.

To capture this part of our family’s life during these years with accuracy and integrity, I invited Laurie Sullivan Maddox, who served as a speechwriter in the Governor’s Office, to be my co-author on the entire volume. Our desire has been for Volume III to be a means by which each of the family members could tell their story and perspective. Laurie interviewed each family member at length and then wrote a portion of the book devoted to their account. Each member of the family was given an opportunity to review the chapter for facts and tone.

My contributions to Volume IV came in the form of the introduction and a series of short essays— personal reflections on each of my family members’ experiences—placed at the end of their chapters. I also recount my thoughts as a parent during this demanding time and how our family preserved traditions and order.

My personal history will consist of at least four volumes:

• Volume I: A Sense of Place and Purpose

This volume encompasses both my Leavitt and Okerlund heritage, as well as my own recollections, beginning with my birth in 1951 and ending in 1993 when I was inaugurated governor of Utah at the age of forty-one. This volume includes my upbringing and young adulthood; my early professional life; marriage to Jackie; and the beginnings of our own family together.

Most of Volume I was drawn from two separate books I wrote in 2007 and 2008 with the help of a former colleague in the Governor’s Office, Therese Anderson Grinceri. Those were titled A Sense of Place and A Sense of Purpose. The 2021 version consolidated the two into one— A Sense of Place and Purpose.

• Volume II: Real and Right

Volume II recounts my stewardship as governor of Utah between January 1993 and November 2003, when I resigned to become a Cabinet officer in the administration of President George W. Bush. The title of this volume, “Real and Right,” was the theme of my campaign for governor in the 1992 election. I wrote this book with the intent to provide a window into my approach to governor, as well as give some insight to the unique aspects of being governor in Utah. I detail how I chose my Cabinet and other important staff members, how I dealt with the media, and how I worked with the state legislature. I give a general overview of the important tasks a governor has, such as giving speeches or staying close with the people.

3

And since I could not have been governor without my dear wife, Jackie, I have included a chapter on her own initiatives, which have also had a huge impact on Utah. I have also included a chapter on my recollections of September 11, 2001, and some events that occurred because of it as that was also a day that irreversibly affected our country.

• Volume III: A Sacred Trust

In my first inaugural address, I used the phrase “a sacred trust” to describe the responsibility I felt as governor of Utah. I have chosen to use the same phrase as the title of Volume III. Volume III responds to a question I am often asked: how would I summarize our most impactful accomplishments during the time I was governor? It takes time for the answer to such a question to mature; real impact occurs over many years. It has now been nearly twenty years since my service concluded, which is plenty of time to get a good sense of what worked and what did not.

• Volume IV: In Service as a Family Future Writing Projects

I plan to write additional volumes of my personal history, since there are many more experiences I hope to write about, such as my time serving on President Bush’s Cabinet, founding and contributing to the success of a group of health care businesses named Leavitt Partners, and my current position as the president of the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square. I also plan to write a volume devoted to my spiritual feelings and experiences. While I have alluded to spiritual feelings and my faith in various parts of volumes one through four, because some of these are more personal in nature, I will write about them separately in a volume that will be held more closely then the others.

It is my hope that these volumes will resonate with readers and take hold in subsequent generations’ histories the same way Sarah Sturtevant Leavitt’s handwritten six pages of personal history galvanized mine.

In a history like this, one cannot write in great detail about everything, so I asked myself a question: What initiatives produced change and an impact beyond twenty-five years? This book seeks to answer that question by detailing eight legacy accomplishments I believe shaped the future of Utah long-term. Against that standard, I have written chapters on subjects such as the 2002 Olympic games; the land exchange we did with the federal government involving reform of the state’s school trust land system; my role in returning control of welfare to the states; the founding and establishment of Western Governors University; creation of a charter schools movement in Utah; the Centennial Highway Fund, which organized forty-four highway projects, including the rebuild of Interstate 15 and construction of Legacy Highway; and an initiative to double the number of engineering graduates from Utah’s colleges and universities via a partnership between high schools and higher education, which produced forty thousand new engineers and positioned Utah as a technology capital.

4

Acknowledgments

In 2018, I invited Laurie Sullivan Maddox, a speechwriting partner from my days in the Governor's Office, to help me with the compilation of my history. I first worked with Laurie when she was a news reporter with the Associated Press and The Salt Lake Tribune . She joined the governor's staff during my second term and became a co-author of many of my important speeches. Laurie has a creative flair and native capacity to give life to words. Throughout this project, she improved my words, always pushing me for clarity by asking the right questions.

In Volume IV, Laurie has taken a more primary role. I asked her to interview members of my family and to summarize their feelings and experiences. Hence, we have bylined those sections to designate her work.

Megan Anderson, a busy mom and extraordinary editor, later joined our team. She has added order and consistency to the project. Megan also introduced us to Roxanne Bergener, whose skill as a layout artist has combined shape and beauty into a wonderful design. She has a keen eye for choosing photos and artifacts that bring our work to life. Like Megan, Roxanne has given our text generation effort structure and discipline. Her dry and irreverent sense of humor enables her to keep us grounded, focused, and on schedule. These friendships have been a meaningful part of this experience for me.

As with the other volumes that make up this history, choosing among a wealth of subjects, thousands of pictures, and artifacts has been difficult. Hundreds of people contributed in important ways to the events described. Not all of them will be mentioned or credited in the way they deserve. For that I have regrets. I hope they will know of my affection and properly attribute the omissions to the complexity of the task.

5

5

6 Introduction 7 1 Everything Changed 9 2 Mansion Fire 16 3 Jacalyn Smith Leavitt. ........................................................................... 32 4 Mike S. 44 5 Taylor 56 6 Anne Marie 64 7 Chase .......................................................................................... 77 8 Westin 92 9 Dixie & Anne 105 10 Getaways ..................................................................................... 115 11 The Brothers 131 12 Jackie's Family 145 TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

By Michael O. Leavitt

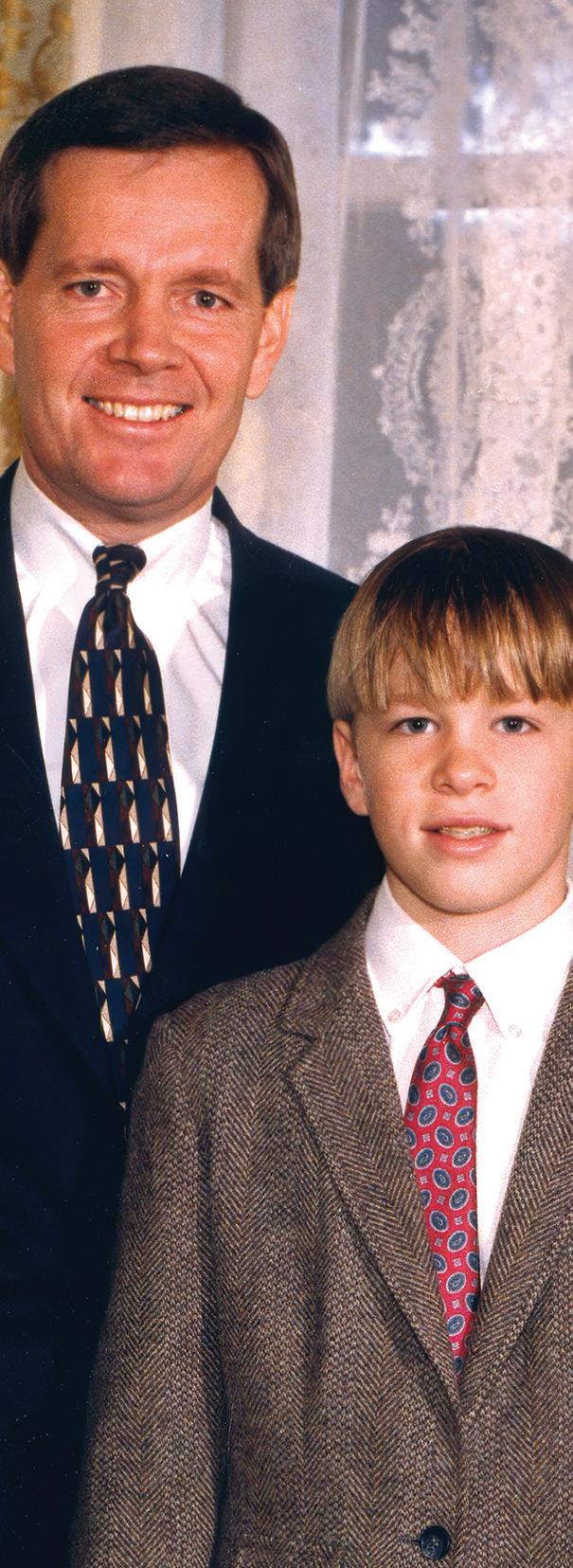

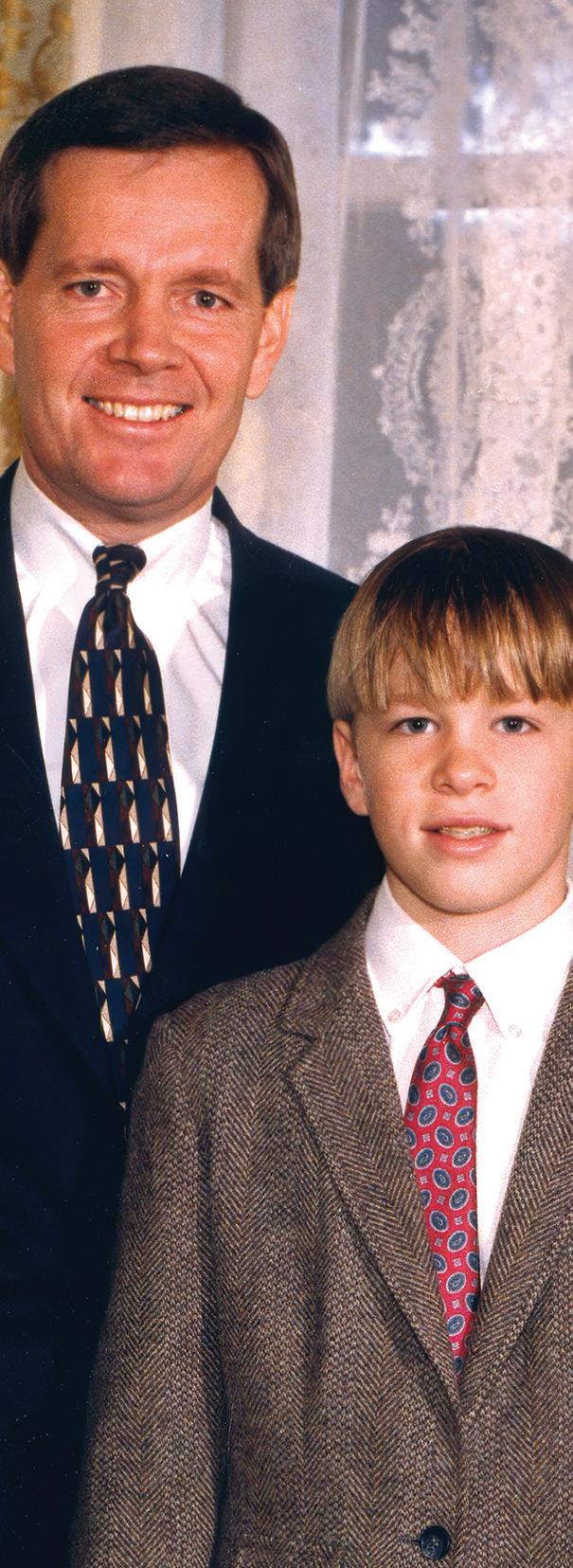

Prior to November 3, 1992, life had been fairly ordinary for the Leavitt Family. Then, with the closing of the polls and a flurry of election night projections, it wasn’t.

The precise moment of change became visibly apparent when I walked down the corridor of the Little America Hotel toward the ballroom and the vote-counting had reached the point of near certainty. Four uniformed Utah Highway Patrol troopers surrounded me, squared up by twos in front and back in a protective formation. Though I was not technically governor yet, just the mathematically likely governor-elect, it was electrifying.

A few minutes later, my parents, Dixie and Anne, saw the same thing—an abrupt indicator of change—as a contingent of troopers materialized and extended around the family.

This was the most immediate and observable adjustment to a high public office. I would have near-constant executive protection for the next eleven years in Utah (plus five more years as a member of the Bush Cabinet). But there were additional changes in lifestyle and comportment that came with the office.

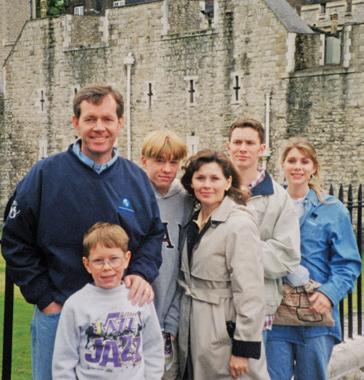

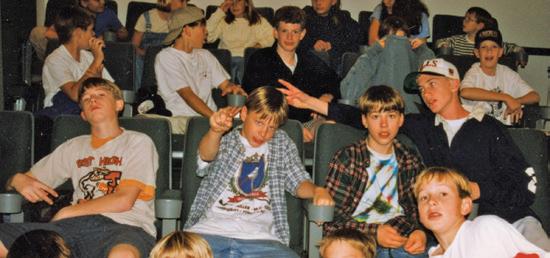

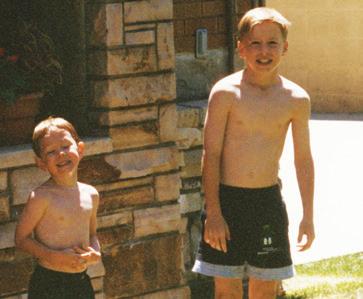

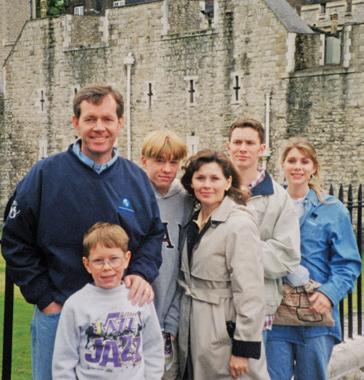

Ours was a First Family both younger and larger than most, with teenagers, a toddler, and a couple preadolescents, all with lives revolving around home, school, church, jobs, sports, family, and a congenial neighborhood on Laird Avenue in Salt Lake City.

My own time with loved ones would be inevitably changed. Family members had already adjusted to time demands and a higher profile during the campaign. Now, that would intensify and become everyday life.

Becoming Utah’s First Family was a shared journey, as Jackie and the kids stepped into their new roles and carried on a semi-private way of life

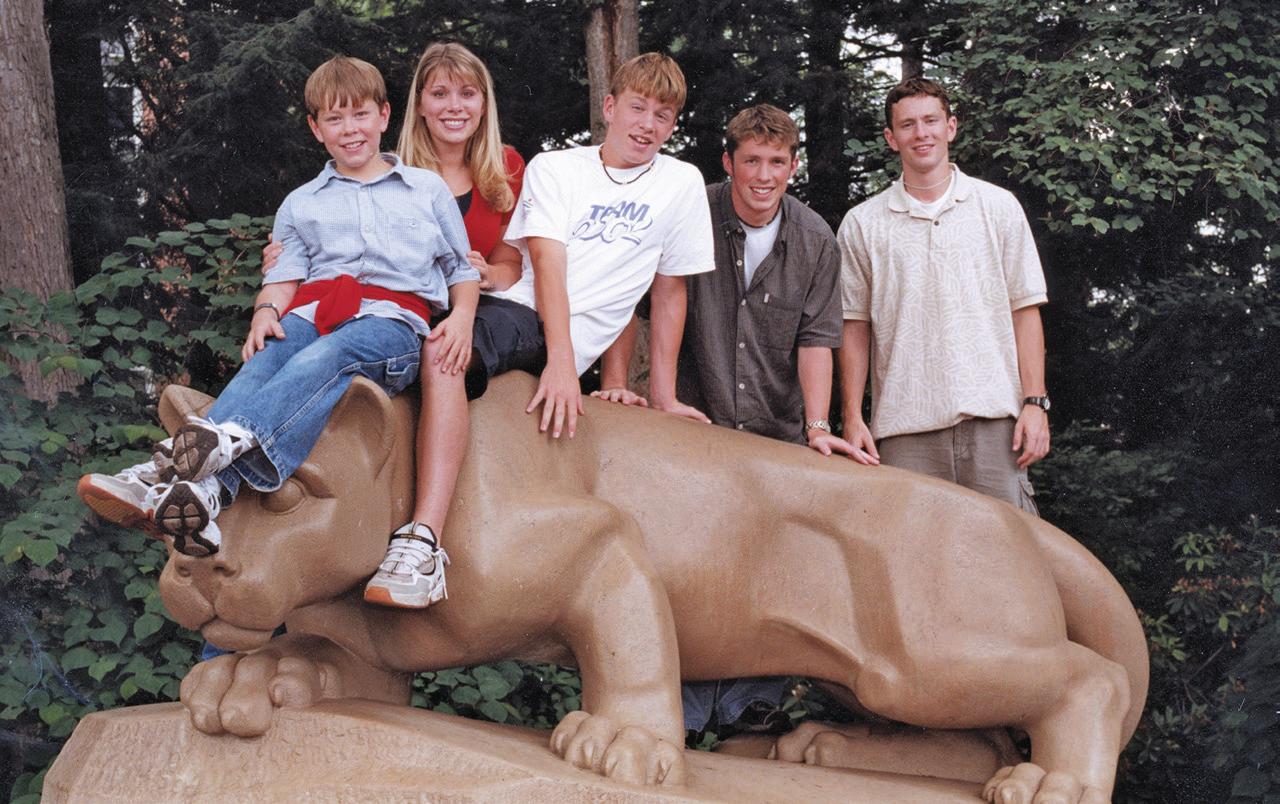

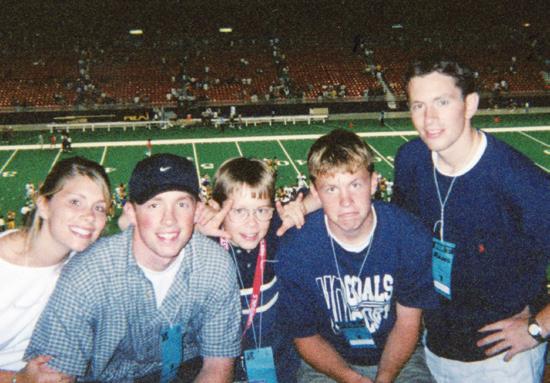

for the ensuing decade. Fittingly then, volume four of Sense of Service will be shared with Jackie, my wife; my parents, Dixie and Anne Leavitt; my children, Mike S. Leavitt, Taylor Leavitt, Anne Marie McDonald, Chase Leavitt, and Westin Leavitt; and my brothers, Dane, Mark, Eric, David, and Matthew. Jackie’s parents Lewis and Cleo Smith, and sisters Christy, Dixie, and Kathie, and their children, deserve to be acknowledged and understood as part of this odyssey, for they, too, were rebranded, imposed upon and affected by my decision to seek this path. Each contributed in their own ways.

They had all rolled with me on this adventure, some working nearly as hard as I had, some taking blows intended for me, others supportive but more removed or oblivious to the ups and downs because of time or distance. Some had trepidation and went all-in anyway.

All of them gave of themselves, even when it meant an unsparing spotlight and living with the awareness that proximity to public service means you, too, will become public. Likewise, it brings excitement, opportunity and an engagement with the world around you, sometimes with a front-row seat to extraordinary times.

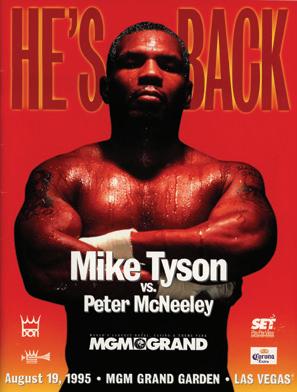

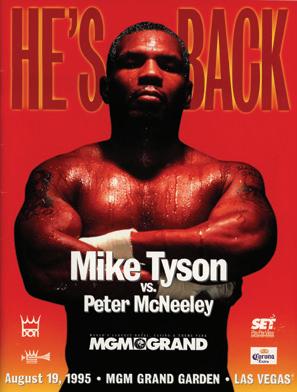

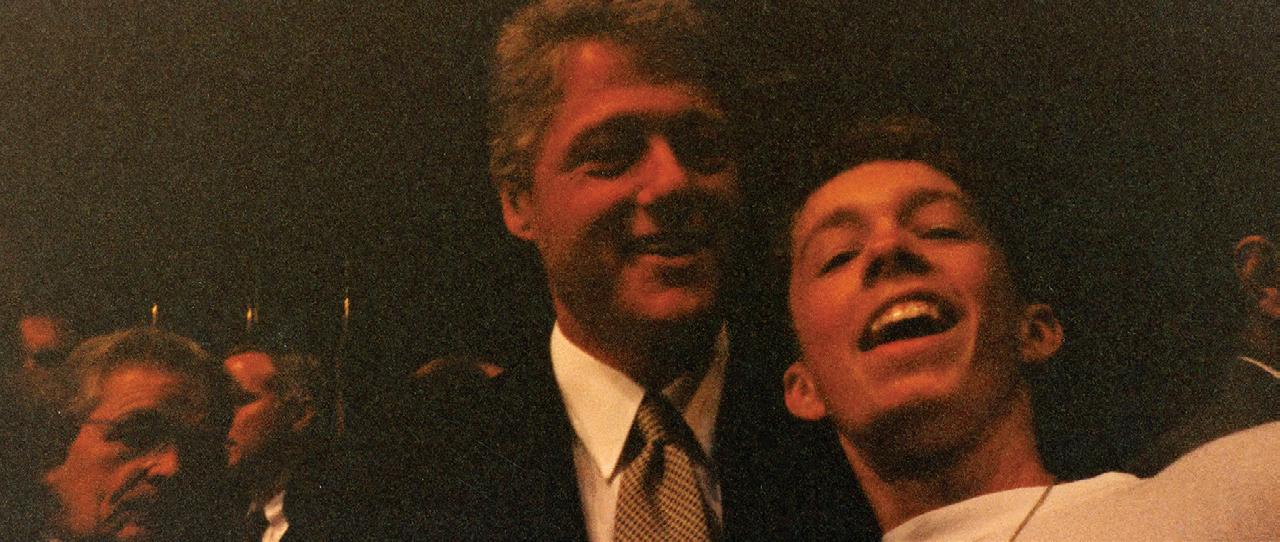

The entire Leavitt family knew that winning the governorship would impose some changes in lifestyle; we had discussed it periodically. Early in the campaign, Dane and Mark had been thrust into the spotlight when the whirling disease episode involving the family fisheries became news. Later, they both had to bear the harshest criticism and scrutiny apart from me when I became chief executive. Chase experienced a media fixation while still a high schooler, when everyone wanted to talk about Fight Club. On the other hand, he also got to meet Michael Jordan and the Dalai Lama.

Yes, this impacted those I love most in ways both anticipated and unforeseen, some briefly, others more enduring. Moments large and small left an imprint, as did the succession of people, places, and events over the course of my time in state office.

7

In order to capture this collage of perspectives and experiences represented by various family members, I invited my colleague and collaborator in compiling this history to co-write volume three of Sense of Service Laurie Sullivan Maddox’s career includes journalistic reporting for national and regional news organizations. She also experienced parts of this story firsthand when she served as my speechwriter for many of my most important public moments as governor.

Laurie interviewed family members to capture their feelings and recollections about this unique decade in our lives—the good and the bad. I felt it might be difficult for me to separate myself enough from my own perspective to capture it objectively. Laurie will.

We will deploy an unusual literary device in this section by alternating voices. Laurie’s writings will reflect her interviews with family members. I will respond with my own perspective and details as I remember them. Most often, they align. At times they do not—but both are honest perspectives shared in love because, to my knowledge, there were no relationship casualties in this experience, a blessing of heaven I want to acknowledge and speak gratitude for.

It is my aspiration that Volume IV will provide insight into not just the unusual and unique aspects of our life as a family, but also the ordinary. Jackie and I navigated the challenges of raising children, while our children navigated the challenge of being children during this time. We celebrated successes and worked to lighten insecurities. We experienced good behavior and not so good. We experienced happy moments and sad ones. We were a normal family in a quite abnormal situation.

There is a temptation when writing about something so dear as one’s family to want to capture every detail, event, and emotion. In relatively few pages it is impossible to capture the totality of a family’s experience over a period of eleven years. So this is not a journal or anything approximating a comprehensive history; It is a mosaic of experiences which I hope will radiate the spirit of our family.

8 INTRODUCTION

Everything Changed

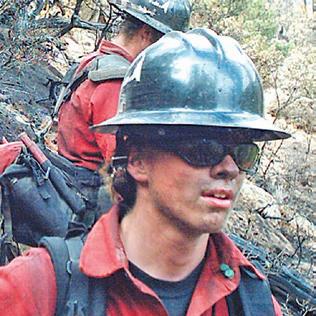

By Laurie Sullivan Maddox

The large Leavitt family—immediate and extended—was there, of course, on election night as the vote totals climbed and the protective trooper screen descended with the victory.

Anne Leavitt watched with composed jubilation and a whirlwind of thoughts, one just a little bit unsettling. “That was very impactful, the minute it was announced,” she recalls. “Michael’s children were surrounded by security. For me, it

was a realization that things were going to be different from that moment on, like there was a barrier erected. For the first time there was sort of a wall we would have to cross that would be different.”

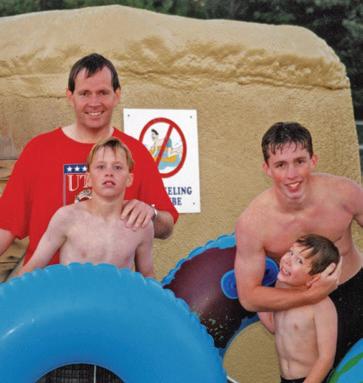

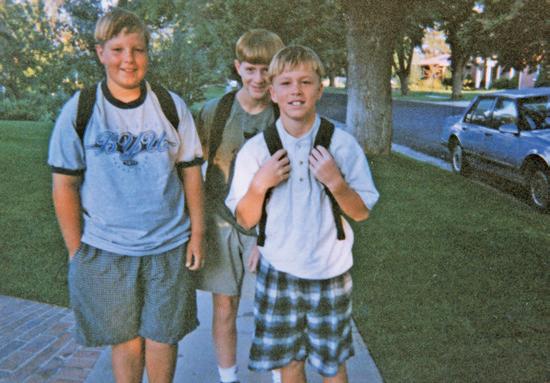

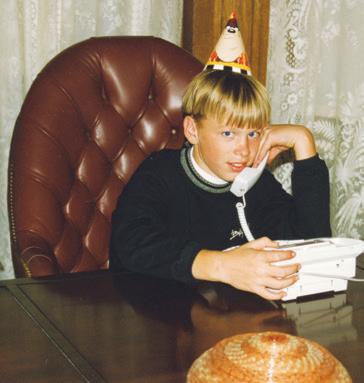

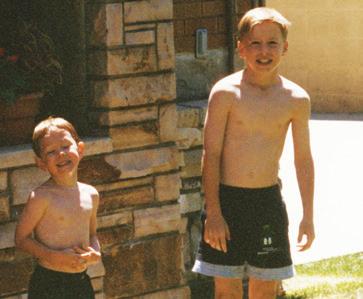

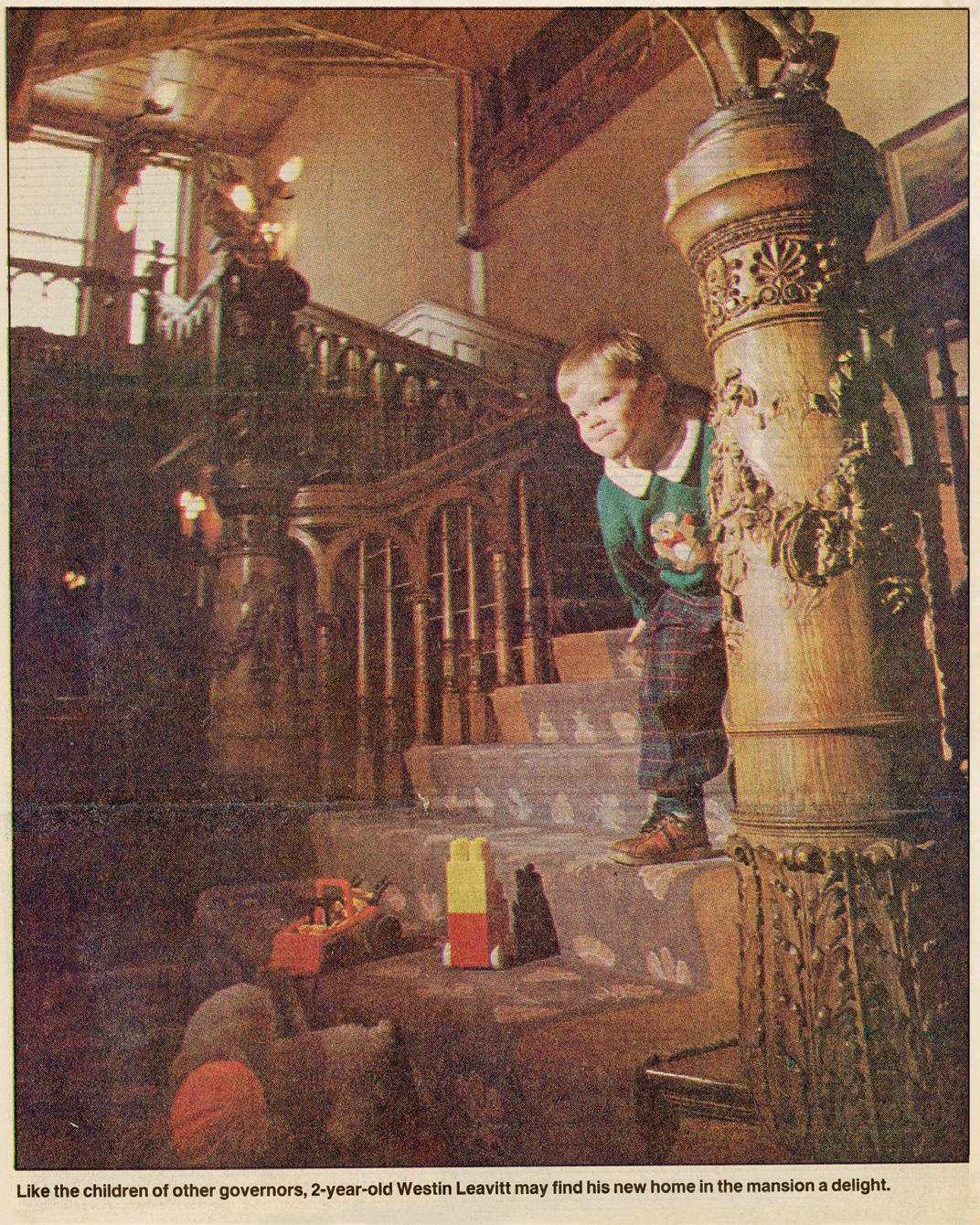

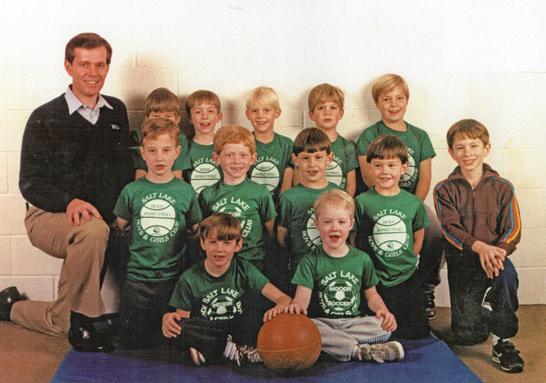

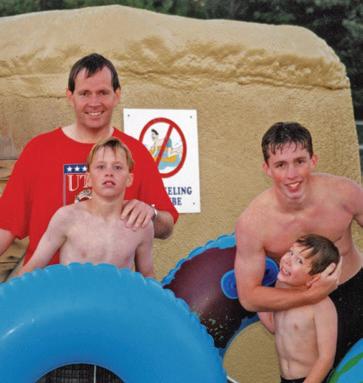

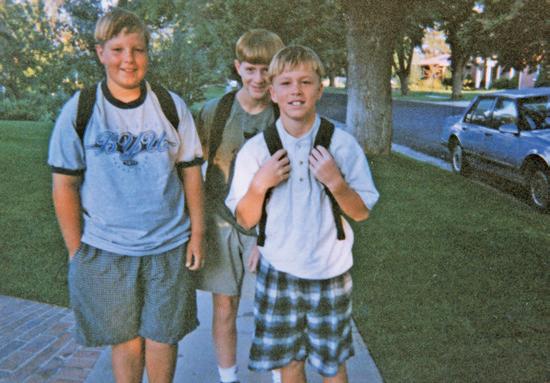

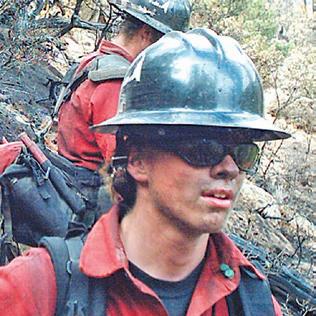

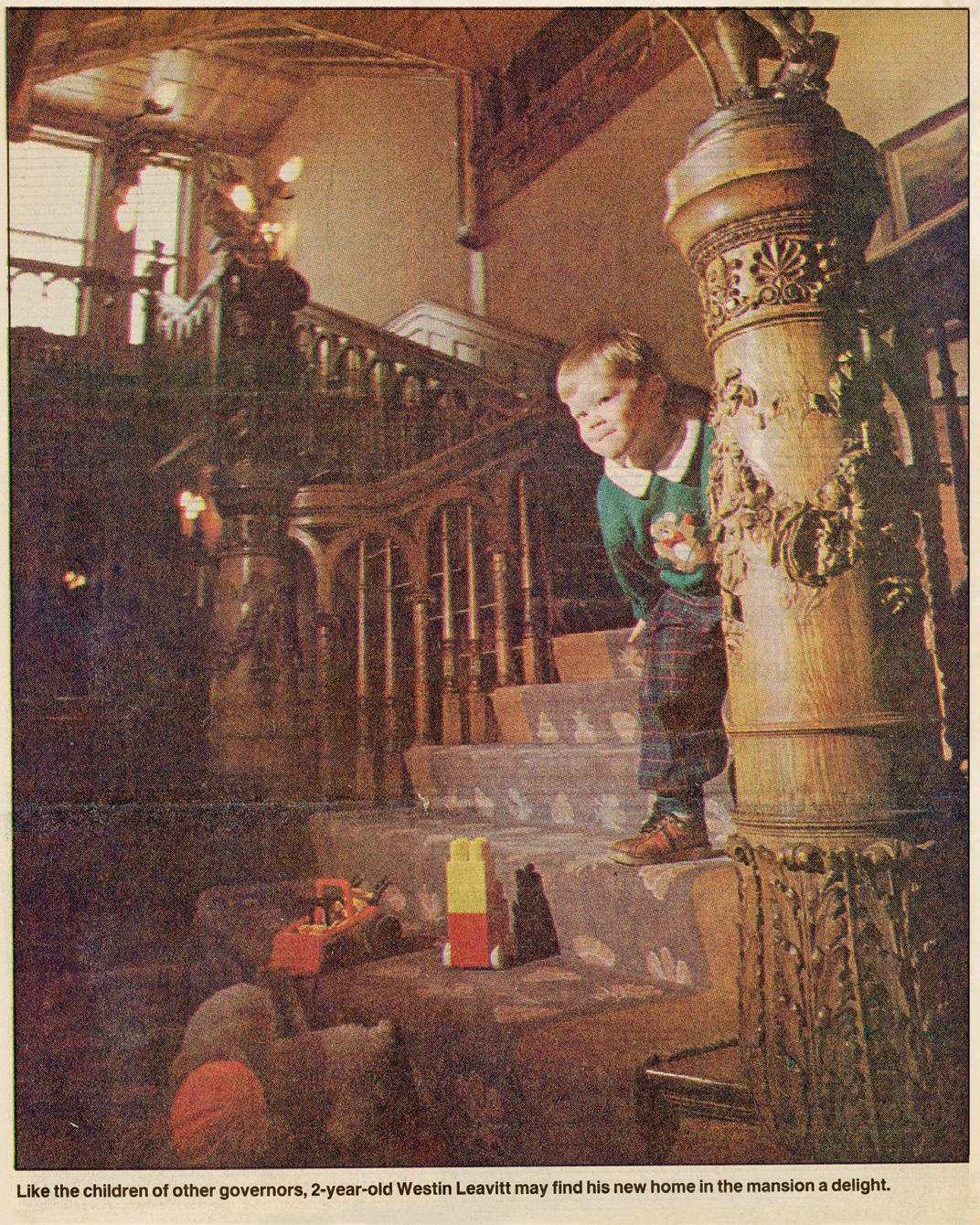

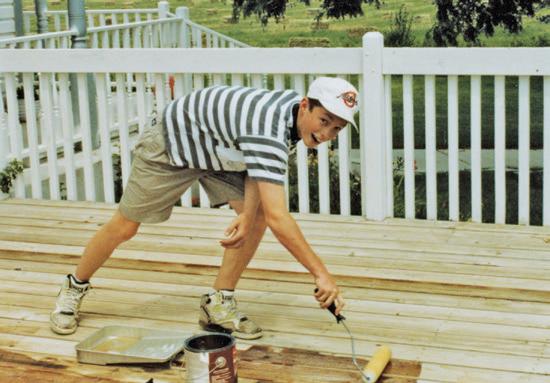

For the five children, ranging in age from sixteen-year-old Mike to two-year-old Westin, it was a happy blur of confetti, cheers, friends, lights, cameras, and limitless M&Ms. They had won!

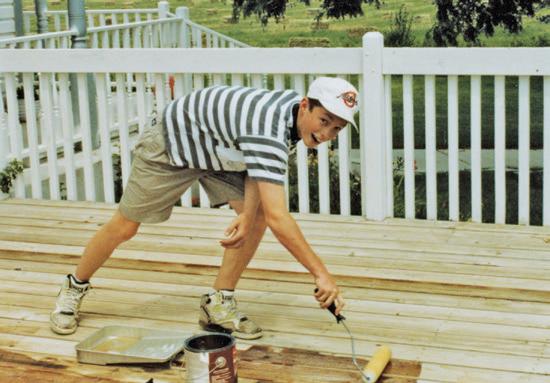

A tender momment

election night 9

between Mike and Jackie on

01

EVERYTHING CHANGED

Earlier that night, Candidate Leavitt had driven to the hotel with Jackie in the 1984 Dodge Caravan. After the victory, a security detail escorted the couple to a new Lincoln Continental, recently purchased for the next chief executive. The minivan was left behind in the parking garage to be retrieved later. From that point on, the fourteenth governor of Utah, even just an incoming governor that night, would always be driven and regularly accompanied by security.

“ I was standing right by my dad when the results came in, and as soon as it flashed that he was the projected winner, it was just such an amazing moment. Everything changed. ”

“It was an amazing night,” says Mike S., who had been informally renamed “ Bud” during the campaign—a name not particularly to his liking—to differentiate him from his father. “I was standing right by my dad when the results came in, and as soon as it flashed that he was the projected winner, it was just such an amazing moment. Everything changed.”

The second oldest, Taylor, fifteen years old at the time, remembers a shock of realization as well, and thinking, “My gosh. This is so different from everything we’ve ever experienced. This is really happening.”

Their Grandma Anne had experienced her initial pang of trepidation and tabled it. This really was happening. The campaign had been a bit of a roller coaster already—the low being what she and other Leavitts considered the obnoxiousness of the Republican primary that preceded the general

election—particularly the irksome personage of Richard Eyre, whose behavior still grated despite his having been vanquished months earlier.

Her grandkids laugh at the thought, even many years later, that Eyre was the only person on the planet to ever cause the straightlaced and proper Anne to unleash the words, “That’s bulls--t!,” after hearing him on a news program. They agree he had it coming.

Anne and Dixie knew well from Dixie’s years in the legislature, his senate leadership, and past campaigns, including his own bid for the governorship in 1976, that slings and arrows, doubletalk, and strained alliances are part of the game. The interplay of truth, decency, competition, and expediency creates unique pressures on the candidate or officeholder, but also ricochets among those in their orbit.

Loved ones sometimes feel the attacks and negative currents even more acutely. Hits leveled at a prominent public figure can glance off the intended target and land a resounding blow to the inner sense of decency, fair play, and well-being deep within the heart of the family member standing nearby. The Leavitt brothers, parents, and children had experienced it to various extents, as had the one standing closest, new First Lady Jackie Leavitt.

Amid the poise, smiles, and easy-going interactions with her fellow Utahns during the campaign, Jackie had worries as well, complicated by the fact that being First Lady meant integrating that profile and public persona with the essentials of family stability. This wasn’t a temporary campaign timetable anymore. It was their new life.

She had to be the one to nail the path to normalcy—the down-home sensibility of the prior life and also the simplicity of it, letting five kids be kids and maintaining the regular routines, all while complementing the chief executive, whose own time as a family man and hands-on partner would be significantly curtailed.

Outgoing First Lady Colleen Bangerter had described it to her during a preliminary tour of the Governor’s Mansion as simply a “different

10

11 CHAPTER 1

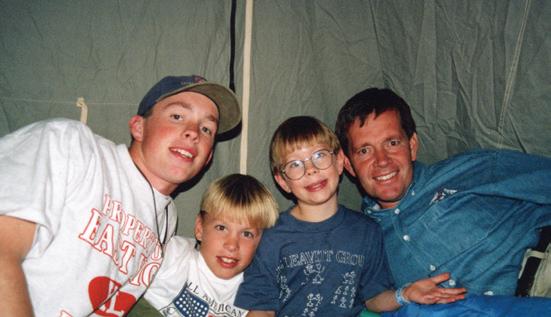

1 The new residence of the Leavitt family—the Governor’s Mansion.

2 Governor Leavitt in the Gold Room of the Utah State Capitol.

3 Utah State Capitol at sunset.

4 Jackie and Mike in front of the mansion. This photo was on the cover of the Governor’s Mansion brochure.

1 2 3 4

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock

EVERYTHING CHANGED

level” of lifestyle. Jackie wondered what that might mean exactly. As she readied her family for the move to the Mansion, and the myriad of other changes to come, she had advice to ponder as well from a conference sponsored by the National Governors Association for new governors-elect, first spouses, and their families.

“It is an adjustment to an entirely different space or ‘intensity,’” she says. “And the goal, especially with children, is to make it as smooth as possible. I wanted to keep their routines and their lives: routines of chores, homework and school, activities and athletics. They had their old neighborhood friends over all the time. They had church and time with grandparents. All these things needed to stay the same. They are vital to keep consistent.”

For the five unique individuals in her care, and the husband Utahns had just elevated, Jackie set about making it so. It did not come painlessly. There was a period early on, shortly after the change of residence from the more relaxed family home on Laird Avenue to the fishbowl stateliness of the Governor’s Mansion, when things became overwhelming. Too many people with too many demands, and the unspoken expectation that she be everywhere at once, and unerringly correct at every turn.

These crosscurrents could be unbearable at times. There were scores of requests for her involvement, but also the regular needs of a busy household. Home was her turf, and the primary domain where she and the family could be themselves. And then there were public expectations and obligations. The demarcation lines were unclear early on, leading to some discomfort.

“I felt intensity about that. The pressure. Always more requests than time, and then people were always around at the Mansion because I never had control of my schedule,” she says. “That was really hard, and it took a year before I caught on.”

When the pressure would mount, Jackie found herself exclaiming, “There are just so many things to do!” Her husband told her he had to fulfill his government responsibilities and needed to stay constantly engaged, but she could choose. “It took me a while to understand him,” she says.

On a handful of occasions, there was a ready and willing understudy. Anne Marie, an extroverted eleven-year-old who loved accompanying dad on jaunts across the state in a rickety small plane during the campaign, did not find greeting and glad-handing distasteful in the slightest. When Jackie needed a respite, the First Girl would act as executive hostess.

“I remember being at every party and at the head of the table,” Anne Marie says. “I sat right next to my dad and made conversation with the people next to me. I knew my mom wasn’t feeling well, so I took over and I loved it. The parties were the best part of it.”

The cross-town move to the Mansion following the inauguration had evoked mixed reactions from the kids. Mike S. had no complaints. Cool place, new adventure. Chase was agreeable; Anne Marie loved it; Westin, a toddler, was blissfully unaware. Home was wherever mom was.

Taylor was resistant—not wanting at all to leave the old neighborhood or alter the comings and goings of his social whirl at East High School. He was placated with first pick of bedrooms and chose a third-floor hideaway with its own bathroom.

Social lives continued apace and hit peak crescendo one night during the second term of office when a spring gathering of some of Mike and Taylor’s college friends—mostly Taylor’s Mike says— set a record unmatched by subsequent or prior administrations for young people milling about exuberantly on the Mansion grounds.

Such high-octane events at the Mansion were memorable for the kids but rare, and largely came after the family was living back at their old home on Laird Avenue following the Christmas fire at the Mansion ten months into the first term. In what would be the best of both worlds, they lived at their familiar home for the rest of the time in office and used the Mansion for gatherings, events, and celebrations.

For Jackie, the first year was the craziest because of the uprooting and unknowns. Living at the Mansion had the dual demands of showcasing the grand

12

residence, a historical landmark and architectural beauty, and making it a home.

The split functions made for some disquieting moments sometimes, simply because of the building’s layout. Family quarters on the second floor were clearly viewable from the first floor where Mansion staff were omnipresent and tours came and went.

The family area was not marked private until after the fire and was accessible from the showstopper of a staircase that rose to all three floors, disembarking second floor occupants onto an ovalshaped and railed mezzanine-type hallway.

Doors with glass windows were the only barrier to curious onlookers, and inevitably there were “sightings,” such as a teenage Leavitt boy in boxers walking around unaware—or unabashed—since the floor plan of the family quarters made absolute privacy impossible.

Jackie once was spotted going about her day by a touring group and had to politely decline a tour guide entreaty. “Look, there’s Mrs. Leavitt!” the guide remarked, as if a safari had just encountered a rare gazelle, “Won’t you come talk to us?” On a couple occasions, strangers simply walked right into the family quarters.

The Mansion was part of the First Lady’s purview, but the boundaries of that responsibility were not always apparent. Others were regularly around—office staff, someone cleaning, someone fixing something, some group from the executive branch using the place for a meeting. “That was the positive and the challenging part both,” Jackie says.

One Saturday morning shortly after the family moved in, only Jackie was home with two of the kids. She was giving Westin a bath and a man kept ringing the buzzer at the gate. Still unfamiliar with the gate, she asked over the intercom what he wanted, and he replied that he needed her to come get some legal papers he had brought over. Can a new First Lady ignore incessant ringing of the gate bell? On a Saturday? Were these hand-delivered papers an urgent matter of state? Jackie whisked Westin out of the bath and went downstairs to the gate, but the episode didn’t sit well.

A bit more unsettling were when members of the public would gawk in windows from outside the gates and even train binoculars on the residence— and on family members inside. Even the shower wasn’t an absolute refuge.

A Mansion assistant once knocked on the bathroom door and called Jackie out of the shower to come downstairs and greet retired television host and local celebrity Eugene Jelesnik when he came by to give the family tickets to an event. “Just put on a robe and a towel over your hair,” the assistant suggested. Unsure of her rights of refusal, Jackie went down to say hello.

Soon, enough was enough. Jackie brought up the episode with her husband, and his solution was a relief: “When you’re on the second floor, you don’t have to come down,” he told her. And she no longer did. Soon enough, she would be the one setting the boundaries.

“You want groups and people to learn about the grandeur of the mansion, and when you invite people to meetings, dinners or events, they always want to come,” she says. Even so, it was a welcome development when the Mansion’s security and privacy were enhanced after the fire. All it took were an additional set of doors leading to the private quarters and a lock.

Outside the grounds, there was not much that could be done. Public curiosity ranged from the bold to the brazenly discourteous, as with the gawkers and their binoculars.

Occasionally, too, neighbors were not necessarily neighborly. Sometimes, someone had nothing better to do than turn an everyday occurrence into a political jab.

State government, policy, and politics were all legitimate and appropriate areas for public scrutiny and interest, the family knew. They accepted that and adapted. More uncertain was how or when their personal, everyday lives merited scrutiny and at what point did that cross a line.

One way to determine a quick mental cost/ benefit on a potential activity was just to picture it ending up on the news—or having it become snarkbait in “ Rolly and Wells,” a news-gossip column

13 CHAPTER 1

EVERYTHING CHANGED

14

1 The famous 1985 tan van that the family drove for many years, including to the election night event. It was replaced by stateowned vehicles and fell into Taylor’s control, becoming an object of great note at East High School. It is parked in front of the Laird home.

2 The family leaving the Laird home to do some campaigning.

3 Chase and Westin playing pre-fire. The gate next to them was put in after the family arrived because the public tours keep wandering into their family space.

4 Chase, Taylor, Westin, and Anne Marie playing in the mansion kitchen.

5 The family in front of the Governor’s Mansion

2 3 4 5 6

6 Riley the dog with Chase

1

in The Salt Lake Tribune that trafficked in busybodies and scolds.

Not long after moving into the Mansion, the family adopted a dog from the pound—Sammy. Someone in the neighborhood soon complained to Rolly and Wells that the dog barked too much and disrupted the peace. When the family had the pooch trained with shock-collar conditioning to curtail the barking, new complaints arose, suggesting the dog must have been surgically de-barked.

Erroneous, petty, and all part of the new life, where an everyday occurrence could become a headline, and a headline turned into an outsized news event. The family gave up the pet and did not have a dog again until the move back to Laird after the fire.

It was expected as part of public life that episodes like this could happen for any reason at any time. The surprising thing was what would set someone off, or who could turn on them, even an acquaintance or friend.

A birthday cake for Anne Marie resulted in “Vanillagate,” courtesy of Rolly and Wells. The cake was picked up late from an ice cream shop in their old neighborhood because a staff assistant had a death in the family a day earlier. The shop owner, whom the family had known and given business to for years, had contacted the columnists about the late pickup.

And so, the guidance conveyed in one form or another to the five kids over time centered on the way seemingly normal things could have a “magnified consequence.”

The admonitions were along the lines of “use your head;” “consequences will reflect more on you and on the family;” or “you have a responsibility here that you have to stand up to.” And for the most part they did.

At the National Governors Association meetings for incoming officeholders, sitting governors and spouses had helpful advice based on firsthand experience. There were one or two tales, however, about how badly someone’s children had been treated by the press or public. Those were outlier anecdotes, but they appalled Jackie.

Utah was different, Jackie and Michael hoped and believed at the time—and ultimately it was. The family dealt with shocking or harsh moments as they occurred the way they felt most naturally inclined—shrugging it off and moving on. Or, as it is more commonly known in the twenty-first century—Keeping Calm and Carrying On.

Each family member had his or her sweepstakes winner when it came to strange occurrences or weird encounters with someone in the public. More importantly, each had exponentially more favorite moments and favorite people from the time in office, along with lasting friendships and endless memories. All are quick to say that the fun times and opportunities that resulted directly from the role as First Family and the proximity to power outnumbered any downsides—by far.

There were insecurities in their roles. There were regrets about having to sacrifice time with dad. There were harsh moments under a news media microscope. There were snide remarks or hurtful statements from people unable or unwilling to decouple the politics from the person.

There also were front row seats to once in a lifetime events, unforgettable encounters with extraordinary people, and unshakeable bonds that the experience forged among them.

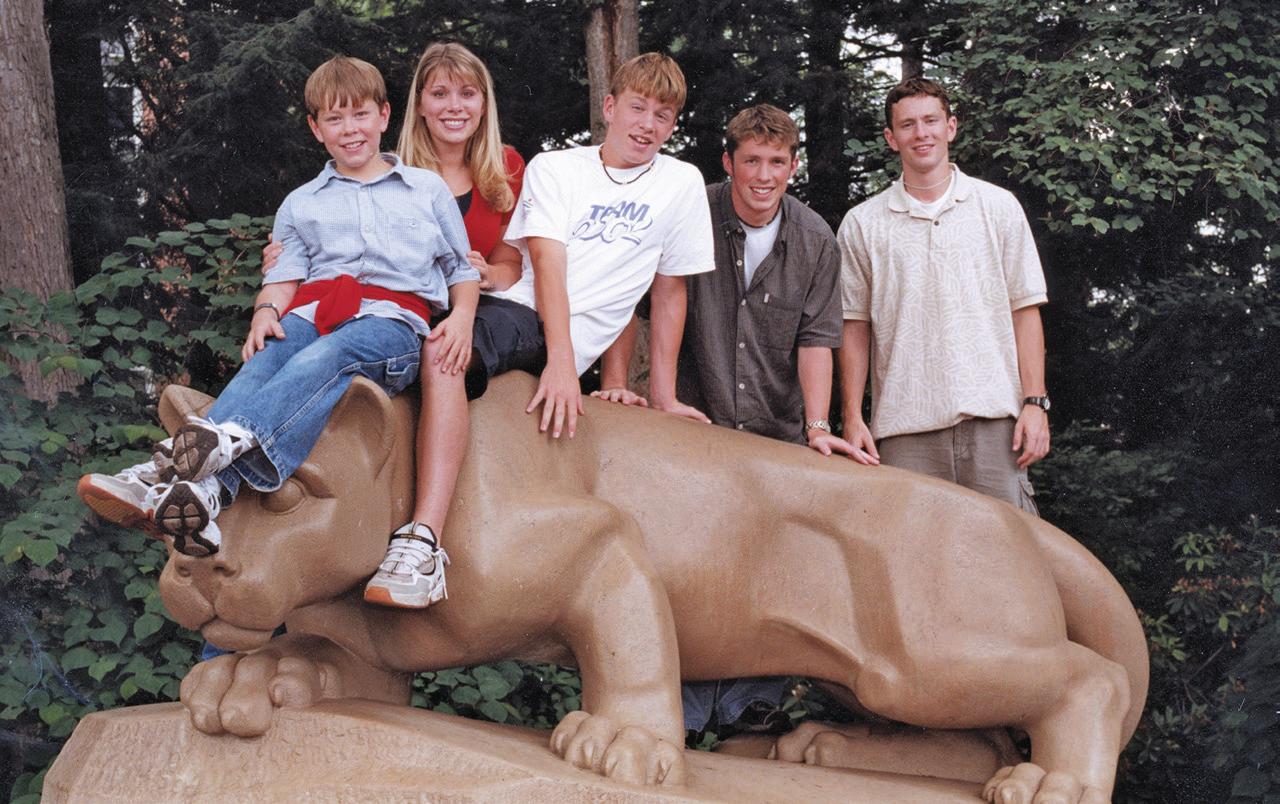

On Inauguration Day 1993, the governor was forty-one; Jackie, forty-two; Mike S., sixteen; Tyler, fifteen; Anne Marie, ten; Chase, nine; and Westin, two. Four family members with February birthdays turned a year older just weeks later—the governor, Mike S., Anne Marie, and Westin. Jackie, Taylor, and Chase all have October birthdays. Mike S. would be the first to leave home and have the shortest time living under the First Family structure. Westin would spend his entire childhood in that unique framework.

Looking back many years later, the adult kids— some older than their dad was upon becoming governor, and all but one married with children of their own—affirm that their parents’ quest to maintain as normal a life as possible was successful. They have distinct perspectives and vivid memories, running the gamut from hilarious to head-scratching to insightful. They also have gratitude.

15 CHAPTER 1

02

The Mansion Fire

This same chapter is also in volume two, Real and Right , because of how it affected both my personal service as governor and my family during the time I served as governor.

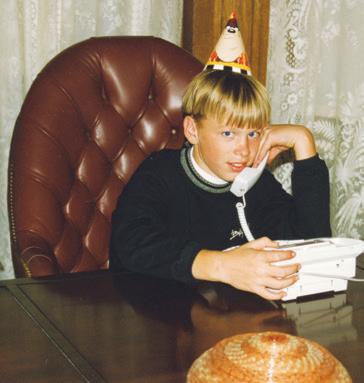

The days leading up to our first Christmas in office were merry and busy. In December 1993, the state capitol and the Utah Governor’s Mansion were bedecked in holiday finery, and both were abuzz with events, festivities, and the regular order of business heading into a legislative session just a few weeks away.

I was slated to give my first budget address to the legislature at midday on Wednesday, December 15. Later that evening, Jackie and I were hosting the Governor’s Mansion Artist Series, which would be attended by some of the state’s most prominent citizens.

16

Photo courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune

The morning of the fifteenth started like most other days. I awoke around 6 a.m. in the master bedroom of the Mansion, where windows along the eastern wall framed the snow-covered branches of a large cottonwood tree outside.

I went over the day’s events in my mind before heading to the shower in the white-and-black-tiled master bath. The bathroom fixtures were more modern than the room felt; years earlier, Governor J. Bracken Lee had reportedly moved out of the Mansion in frustration over a showerhead that water-bombed him from every direction.

The opulence of an earlier time and an air of history permeated the place. The Mansion had risen lavishly at 603 East South Temple soon after the turn of the nineteenth century and became an entertainment showpiece as well as a residence. President Teddy Roosevelt had slept there, and President Dwight Eisenhower had dropped in for a visit.

French Renaissance Splendor

The building is a mansion by every conceivable measure. It was built in 1902 by Thomas Kearns, the son of a farming family from the Midwest, who traveled to Utah in 1883 to seek his fortune. He found it in mining. Kearns struck it rich by buying up a handful of mines in Park City where silver was found in abundance, including the Silver King Mine—one of the greatest silver mines in the world. Kearns became a prominent citizen, a co-owner of the The Salt Lake Tribune newspaper, and a US senator for one term. When he and his business partners became wealthy, each built their mansion along South Temple near downtown Salt Lake City.1

The Kearns mansion, designed in the French Renaissance architectural style by Utah architect Carl M. Neuhausen, was a twenty-eight-room marvel with six baths, ten fireplaces, an all-marble kitchen, electric lights, steam-heated radiators, a call board, dumb waiters, a billiard room, a thirdfloor ballroom, a bowling alley in the basement, and ornate trims and fixtures throughout. Kearns’s wife, Jennie Judge Kearns, traveled to Europe to

hand-select the finest art, furniture, and decor. The Mansion had turrets on three of its four corners, carvings around the windows and doors, and a carriage house on the grounds—initially for Thomas Kearns’s eight carriages, and later for cars. Kearns also had three vaults in the home, according to the Deseret News, to store his “copious wealth and wine stocks.”2

Following Kearns’s passing, Jennie donated the building to the state in 1937 with the condition that it serve as the official residence of the governor. A succession of governors resided there until 1957, when the property was turned over to the Utah Historical Society for two decades until the administration of Governor Scott Matheson, who launched a renovation of the Mansion in 1977 and restored it to its role as the governor’s residence by 1980.

“And a Merry Christmas to You All”

In line with that renewed tradition, our family had moved in upon my inauguration. I was observing another tradition on December 15 as well; my first event that morning was a breakfast meeting at 7:30 a.m. with the editorial boards, publishers, and owners of the major news organizations in the state to preview the budget message I would be delivering to legislators later that day. The budget-review breakfast with the media was an annual event started by one of my predecessors.

There had been a festive gathering of cabinet and governor’s office staff and families the night before in the ballroom, one of several held that year with music, cheer, and lots of food. People loved to come to the Governor’s Mansion anytime, but especially at Christmas.

Volunteers had begun decorating the Mansion inside and out right after Thanksgiving. Holly berry draped every wreath. Tiny lights made the woodwork and marble floors twinkle. Christmas trees animated nearly every room, including a twenty-two-foot fresh pine that reached from the main floor though an open ceiling all the way to the third floor. This was a masterpiece of tree

17 CHAPTER 2

1. Brooklyn Lancaster, “Thomas Kearns Mansion and Carriage House.” Utah Historical Markers, University of Utah. https://utahhistoricalmarkers.org/c/slc/thomas-kearns-mansion-and-carriage-house/ 2. Jerry Spangler. “Loss is a blow to ex-First Lady,” Deseret News, 16 December 1993

18 THE MANSION FIRE

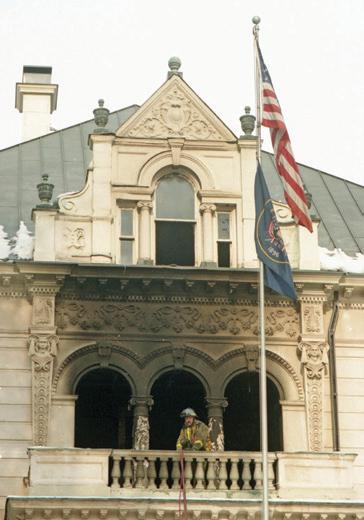

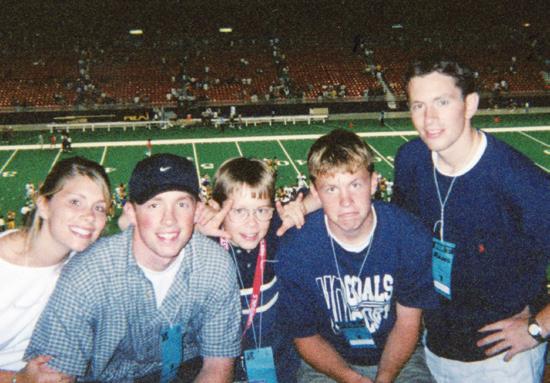

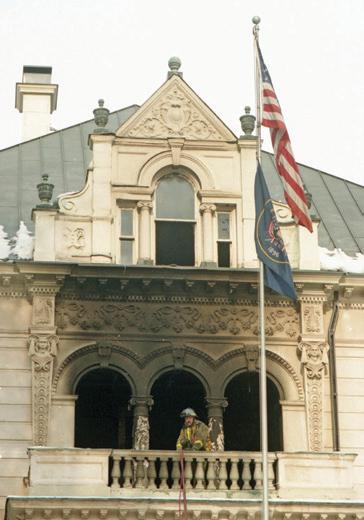

1 Smoke from the fire coming from the mansion roof

2 Press conference with family in front of the mansion

3 Chase and Mike walking to safety after fire.

4 Firefighter on balcony

5 Damage from the fire inside mansion

1 2 3 4 5

Photos courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune

19

Photos courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune

20

decoration, complete with yule logs at the base and cotton on the branches to connote snow, along with hundreds of carefully placed ornaments and two thousand lights.

I was joined at the kitchen table by my older sons, Mike and Taylor, who were hurriedly eating bowls of cereal before rushing off to East High School. As the first guest arrived, I could hear Jackie getting Anne Marie and Chase ready for the drive to Bonneville Elementary in our old neighborhood.

Our guests assembled in the formal dining room on the main floor. As they ate, I laid out the details of the budget, taking care to pause on my priorities in hopes they would provide editorial support in their publications.

As I talked, I noticed a staff member walk through the grand hallway and plug in the big Christmas tree. An immediate brilliance filled the room, and we all paused to enjoy the moment. “And merry Christmas to you all,” I said, before moving on with my remarks. The editors and publishers asked questions and expressed their opinions. When we finished, I bid them goodbye, walked upstairs to make sure Jackie knew the details of when she needed to arrive at my office for the budget address, and off I went to the Capitol.

“ Governor, there has been a small tree fire on the second floor of the Mansion.“

It was interim day for the legislature, which meant committee meetings for lawmakers in preparation for the general session in January. Beyond the buzz of legislators, staff, and lobbyists circulating around the Capitol, the spirit of Christmas livened the scene. A large Christmas tree sparkled in the rotunda, and a high school choir sang carols on the east steps, their harmonies cascading along the granite walls and up toward the domed ceiling.

I still had preparation to do for the budget address, which was the main event of the day. I had already decided not to read a prepared speech, but rather to speak from talking points, using large charts as supporting materials. I wanted to take questions from legislators and engage them in a dialogue. It was the first budget my administration had developed entirely on our own, and I wanted the legislature to know I understood it and was prepared to defend it.

A Small Fire on the Second Floor

About 11:15 a.m., I was working with budget director Lynne Ward and chief of staff Charlie Johnson at the oval table in the formal office when Lee Perry, one of my security detail, appeared suddenly at the door of the office.

“Governor, there has been a small tree fire on the second floor of the Mansion. Apparently, they have it all put out and things will be okay,” he said.

My mind flashed back to when I was fourteen years old and our family home had caught fire. It was a traumatic experience for my family and me, and I knew that any such event would be unsettling to Jackie. Lee Perry’s brief report also was troubling; the second-floor tree he referred to was an artificial tree—not likely to be involved in a fire.

“I need to get down there,” I told Charlie and Lynne. “If I am delayed, ask the legislative leadership to delay the starting time of my appearance.”

It takes roughly seven minutes to drive from the Capitol to the Mansion. When in a hurry, security would turn on 2nd Avenue and drive toward G Street. As we got closer, I could see smoke. “That doesn’t look like a small tree fire on the second floor,” I said out loud.

As we passed G Street, I could see fire trucks and emergency equipment, with men operating in full emergency mode. We turned the corner and pulled into the parking lot of the adjacent Utah Arts Council building, where I could see Jackie standing with Westin. My anxiety level dropped immediately after seeing them safe. However, just as I stepped from the car, there was an explosion, with a shattering of glass and a roar of flames jumping skyward. A light snow began to fall as Jackie began to tell me what happened.

21 CHAPTER 2

Jackie’s Firsthand Account

As she described it in a personal written account of the event:

“I planned to drive to the Capitol and join Mike at noon as he made his budget address to the legislature. Westin had settled in to watch a favorite video in the family room on the second floor, and I took a few moments to walk through the parlor and dining room on the first floor, checking on details for our next event.

Truly, the Mansion was in its finest with the colorful Christmas decorations—poinsettias lining the carved wooden staircase up to the third floor; garlands on the fireplace mantles; a large nativity scene; and the large, fresh, blue spruce Christmas tree that had been cut and brought into the Grand Hall. The residence was spectacular.

Special tours had been going on, as the Mansion was open to the public every day of the week before to share its holiday grandeur. The glorious sights and sounds of Christmas music filled this impressive structure as musical groups performed carols during these tours and at the other public gatherings.

Judith George and Carol Bench, the Mansion office staff, informed me that two men had arrived for the purpose of checking the fire alarm system. Two other maintenance men had also come to do some work on the furnace in the basement. Lauralee Hill, Mansion assistant, was in the second-floor kitchen as I went to the master bedroom to change from my casual clothes into my suit before traveling up Capitol Hill.

“ There’s a fire! Run! “

I heard a strange sort of popping noise just outside my open bedroom door. The sound came from just below the large oval opening, which overlooked the first floor Grand Hall. I stepped out and looked over the wood railing to see a shocking sight—a fire racing up the twenty-two-foot Christmas tree approaching

the second level hallway. I instantly yelled, “Fire!” and started to run toward Westin. My mind raced, “What have those crazy fire alarm men done!”

I heard Carol Bench calling out from the first floor, “Get out, get out, get out!” As I ran toward the family room, I yelled, “Westin, Westin!” He came directly into the hall and I swooped him up. Hearing the commotion, Lauralee Hill ran into the hallway. “There’s a fire! Run!” I said to her.

The three of us hurried down the back stairway within seconds. At the bottom of the stairs, I handed Westin to Lauralee to quickly grab two coats from the closet. I threw one around Lauralee, wrapping it around them both. Then, we ran past the office reaching the back door of the Mansion, Judith, Carol, and the two men who had been on the first floor checking the alarm system, quickly fell in behind us, and I yanked on the door.

I pulled forcefully on the back door, but it would not budge. Intense suction of the air, affected by the flames—which had now burst upward from the tree past the first floor to the large, open, third-floor ceiling dome—caused a powerful backdraft. The two fire alarm technicians at the rear of our group quickly came forward and together were able to pull the door open. A loud whoosh of air blew by us as we ran out, and the door slammed shut with a bang.

We stood together in the parking lot looking in shock at the home when someone asked, “Is everyone out?” In just a moment, the two furnace repairmen who had been in the basement came out. Luckily, they had been near the back stairway of the Mansion, saw the smoke, and ran up the stairs and out the door.

We exchanged anxious words as smoke poured from the windows. Carol’s yells for us to get out quickly had alerted Judith, who in turn had placed a call to 911 before she joined us at the back door. Carol had been walking through the Grand Hall at the moment the

22 THE MANSION FIRE

23 CHAPTER 2

1 Dome

2 Grand Hall fireplace

3 Fire destroys grandfather clock in the Grand Hall.

4 Taylor looking through the oval

1 2 3 4 5

5 Firefighters and inspectors looking over the tree and source of fire..

fire actually started. She heard the popping noise and saw the sparks that ignited the tree. The speed with which the fire leapt up the tree made it impossible for her to get an extinguisher or do anything to stop the burst of flames exploding up the tall tree.

I asked Lauralee to take little Westin to her apartment. The frightening sight was distressing to adults and certainly much more so to a three-year-old.

Finally, the fire engines arrived and the men began their task.

Mike arrived at the scene and the group of us moved to the larger parking lot east of the Mansion to give the firefighters more space and for us to be at a safer distance. It was clear the fire was spreading throughout the home.”

The Kids

Watching his Disney video in a room on the north side of the building, Westin had heard his mother’s urgent calls. Running out to her, he saw the south side of the family quarters, where he shared a bedroom with Chase, erupt in flames.

“I remember loud pops and booms and pieces of wood just being shot up,” he recalled. “Where my room was, that was gone. If I had been in my room, I would’ve been trapped. But I happened to be in the farthest possible room.”

He remembers the scramble down the stairs with Jackie and Lauralee, the difficulty getting out the back door, and then congregating in the parking lot next door.

That is where I met up with Westin and Jackie and, gratefully, found them safe.

It was clear that news of this would spread quickly. Large crowds had amassed on the periphery, and news media were broadcasting the scene live. We were concerned our four older children, all at school, would hear the news, possibly in second-or-thirdhand distorted ways, and would have undue concerns about our safety. They needed to be with us, so I sent two members of the security

detail to retrieve them, one to East High and the other to Bonneville Elementary. We had previously established emergency protocols with the schools in case the kids needed to be quickly picked up, so within thirty minutes, all four joined us at the Arts Council building.

“ If I had been in my room, I would’ve been trapped.”

Taylor, then a sophomore at East High, was walking down a hallway at school when a friend of his brother slammed him in the arm and told him, “Your house is on fire.” Taylor then heard an announcement over the school public address system to come to the office and had “a premonition of what was about to happen.”

When Mike S. got to the office, school officials told them, “Everybody is safe. There has been an incident.” The office had a small television where the boys could see live news coverage showing smoke and flames billowing out of the Mansion.

“Oh boy,” Mike thought, as he and Taylor checked out of school and headed over. “I wouldn’t say it was traumatic. I think when you’re seventeen or however old I was, your brain just hasn’t fully developed. You don’t understand what could have happened to my mom and my little brother.”

Taylor recalled listening to an Eric Clapton song play on the radio as Mike drove and wondering to himself, “Is the house totaled?” Once at the scene, he remembers a fire department official tearing up as he informed the group how badly the building was charred.

Lee Perry, the UHP officer who first told me about the fire, picked up Chase and Anne Marie from Bonneville Elementary and brought them to join the family. Chase was struck by the number of emergency vehicles and the sea of flashing lights as they arrived. He saw Taylor, red-eyed in the parking lot. “I always looked to him,” Chase said, “so I knew, ‘Oh no, this is bad.’”

24 THE MANSION FIRE

Perspective and Gratitude

Jackie and I drew them close. It was a moment when perspective benefitted all of us. “I said to them, “Everyone is safe. No one was hurt. Things can be replaced.” We all hugged each other.

When the fire was out, an official—I believe from the state fire marshal’s office—came over and gave a dreary report to the group. Though the building’s interior and contents were a total loss, we were heartened that the exterior walls still stood firm. The officer explained that the fire department had preplanned how to fight fires in certain buildings. In the Mansion’s case, part of the effort had been to build dams or berms inside the structure to direct the massive amounts of water needed to fight the fire outside, thereby protecting the integrity of the building from additional damage.

The fire official then invited me to go inside and view the extent of the damage with him. I asked each member of the family if they wanted me to bring anything out. Jackie needed her purse. Chase wanted a pair of shoes that Utah Jazz star Karl Malone had given him after he wore them in a game. The shoes were damaged, but not totally unsalvageable. Jackie’s purse and wallet were destroyed.

The house was still smoldering. The Christmas tree now looked like a twenty-two-foot stick man, scorched and devoid of any sign of life. The woodwork and floors were blackened; the gears and workings of the eight-foot grandfather clock in the Grand Hall had melted together; a woodcarved statue of Neptune was completely charred.

Gratefully, the framework of the home was intact. But what was not burned was melted, saturated with smoke, or both.

The chief explained how a fire like this works. In a dry tree, as the once-fresh pine in the Grand Hall had become, fire burns so quickly and so hot that once ignited, there is no way to stop a conflagration. Within forty-five seconds the fire was burning at four thousand degrees. I asked about the explosion I observed as I drove up. He said that fire needs oxygen to survive and goes in pursuit of it, and the fire had found a weakness—the windows— and blew them out looking for life-giving air.

Likewise, the chief said, that was why the door was sealed shut when Jackie tried to exit. It was a vacuum caused by the fire suctioning air from the interior rooms. The chief used a screwdriver to take the cover off a light switch. He showed me signs of smoke and heat under the screws, explaining that the fire was looking for oxygen even under the screws of the light socket.

I left the Mansion that day eternally grateful that no one was hurt, and tried to avoid thoughts of the tragedy that could have happened if the fire had occurred at a time when a hundred people were in the house. We were truly blessed.

The Aftermath

I still had work to do. Jackie and I had to meet with the media and answer their questions. At that moment, there were more questions than answers, but people needed to know that we were all right and feeling resilient. There was a universal concern, of course, for our young family. We felt the love and prayers of people who had extended both on our behalf. And once we knew the family was safe, there was a palpable calm.

There were three things that needed my immediate attention. I called the security team together and said, “I’m going to need your help.” I gave one the assignment to find a place for us to stay. Second, we needed clothes and basic supplies. I took credit cards out of my wallet and gave one to Jackie, since hers were melted by the fire; the remaining cards went to highway patrolmen. Jackie then divided

25 CHAPTER 2

26 THE MANSION FIRE

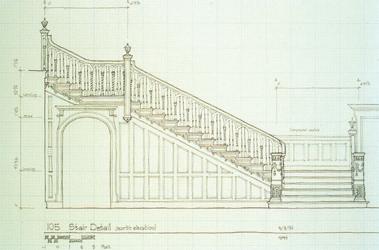

1 Structural repair to dome

2 Painter working on the large ballroom turret

3 Gold leaf being applid to decorative border

4 Stencil work for walls redrawn

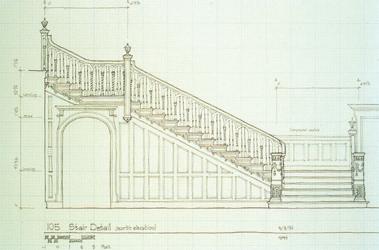

5 The process of rebuilding the detailed spindles of the staircase banister

2

4 5

Photos courtesy of Ellie Sonntag

1

3

27 CHAPTER 2

1 Informal dining room after fire restoration

2 Cherubs decorate the Mansion, and these were remolded after fire damage

3 Formal dining room after restoration

4 Intricate column restored in the Grand Hall. Stencil of wall in background was all redone.

5 View of grand staircase from above after restoration

1 2 3 4 5

Photos courtesy of Ellie Sonntag

the children up into teams, saying, “Let’s each think what we would need if we were packing a bag for a trip.” One trooper took off with the older kids to shop for necessities; another went with Jackie and the younger children. Two days earlier I had dropped off two suits and a few shirts at the dry cleaners, so I asked one of the detail to stop and pick them up. Lastly, I had a budget address to give at the State Capitol. We agreed we would all meet back up at a hotel to be determined later, and we started the task of putting our lives back together.

A couple hours later, at two p.m., I walked into the House of Representatives chamber for the budget address. Legislative leaders had offered to cancel it, but keeping the commitment seemed like the right way to convey that everything was okay. It also was a chance to express my gratitude in a public way and lift the mood with a bit of humor. I said, “Thank you for deferring our meeting. About 11:30 this morning I learned about a need to amend the state budget.”

People immediately understood my light reference to a serious situation. I reported that we were all safe, and that I had been assured that the structure was insured properly, in a way that would cover repairing the house and maintaining the historical integrity of the building. I finished the budget address and went immediately to find the family.

I was notified that we would be staying at the Marriott University Park Hotel in Research Park at the University of Utah. Then, within a few days, we moved into a very nice condominium in American Towers in downtown Salt Lake City.

We stayed there for about three months, including the Christmas of 1993. Many of the children have remembered that as one of their favorite Christmas memories. My aunt and uncle—Jane and John Piercey—brought us a Christmas tree. We had Christmas Eve dinner at Lamb’s Grill across the street from American Towers. And it became a poignant and cheery time, uncomplicated by many of the more commercial aspects of the holiday, because all we had were each other.

But we did need a more permanent home. Jackie and I had leased our family home on Laird Avenue to a couple upon moving into the Mansion nearly

a year earlier, and we decided to approach them about buying the lease out. As it turned out, they were mulling a return to Las Vegas, where they had lived previously. The payment from us made that possible, and we were able to move home. At the time, we didn’t know how long the Mansion would take to restore, or how we would feel about things when the restoration was completed. However, we knew for now that moving back to the house on Laird Avenue was the right thing to do.

So, we moved back. The security team built a small office in the basement of the house and put up a large communications tower so that our home could be monitored day and night from the Capitol building. I wasn’t sure how I felt about that. I imagined the protective team there watching early in the morning as I dodged onto the front porch in my underwear to get the newspaper. But, we were back living an extraordinary experience while surrounded by the feel of ordinary life.

Restoration and Reconstruction

The Mansion’s return to life from the fire, which was determined to have been caused by an improperly spliced electrical wire in the base of the tree in the Grand Hall, would take two-and-a-half years and nearly eight million dollars to complete.

“ My thoughts were how in the world were we going to put it back together. ”

The Salt Lake Fire Department had taken the first immediate steps toward mitigation when they placed dams in the building while fighting the fire to prevent water from further damaging floors and woodwork.

Further damage was averted by nightfall that evening by state employees from the Division of Facilities Construction and Management (DFCM) and mitigation contractor Utah Disaster Kleenup, who moved quickly to restore heat to the building and begin vacuuming up water, drying out the

28 THE MANSION FIRE

29

Photos courtesy of Ellie Sonntag

Mansion, and topically cleaning windows, woodwork, and other surfaces of smoke and soot.

Officials next had to assess the extent of damage and determine a plan going forward. The assessment team included DFCM, the State Fire Marshal’s Office, and the Division of State History. Their consensus was that the structural integrity of the building was good, with enough original materials retained, to warrant reconstruction.

Going forward, the basic philosophy was to preserve the building’s original craftsmanship to the extent possible; replace original features lost in the fire; and clean, repair, and restore items that were salvageable. Additionally, the effort expanded to make the Mansion more user-friendly as an actual residence to governors and their families, and to modernize the building with seismic upgrades and a comprehensive updating of heating, ventilating, cooling, electrical, lighting, computer/communications, and fire suppression systems. Other changes were made to allow better exiting in the event of a future fire, which was done with hallway and corridor reconfigurations rather than the addition of a new stairway. Also, the family quarters were made more private and secure.

Max J. Smith and Associates was selected as the project’s architect and Culp Construction as the general contractor. A number of specialist firms were brought in as the work continued, week after week, month after month.

“My thoughts were how in the world were we going to put it back together,” Fred Fuller, an architect with DFCM, told the Provo Daily Herald newspaper about the day he first surveyed the destruction at the Mansion.3 Beyond the charred interior, smoke and soot had permeated spaces within interior walls and had to be cleaned. More than eighty percent of all plaster had to be removed from the Mansion’s interior walls to expose all the framing materials of the building.

Soot and smoke remediation alone took ten months and one million dollars, according to Culp Construction. An innovative new process called sponge blasting—which shoots small particles of highly absorbent sponge at high velocity onto contaminated surfaces—was employed, along with grit blasting, to remove soot. Ozone generators also were used for deodorization before walls were replastered.

The restoration team took the building interior apart and documented all surfaces and elements for restoration or replication. Then, over time, the interior was put back together. Throughout the process, photographs and historical records guided the work.

Among the specialists called in for highly skilled artisanal restoration was Agrell and Thorpe, Ltd., a California wood-carving company.

Woodcarving and plasterwork were unique architectural features of the Mansion. The original French white oak carvings were of extraordinary quality, crafted in Europe at the turn of the century by German or Austrian artisans. The fire destroyed most of the carvings, with the worst damage occurring in the Grand Hall where the Christmas tree stood.

The burned carvings sent to Agrell and Thorpe to replicate included a large volume of intricately carved balustrades, newel posts, figures, capitals, columns, and egg-and-dart molding. The company’s Master carver, Ian Agrell, described the Mansion carvings replication as the largest wood carving project undertaken anywhere in the world in the previous ten years. The company’s twelve craftsmen spent nearly twenty-thousand hours over two years recreating the mansion’s original carvings—by hand, just as it was originally done.4

Another unique restoration involved the golden dome centered over the balcony of the second and third floors above the staircase. Remaining sections of it were removed and carefully rebound, and the Baltimore firm of Hayles and Howe used

4. “Case Study: Utah Governor’s Mansion Fire,” Agrellcarving.com , https://agrellcarving.com/2016/07/12/case-study-utah-governorsmansion-fire/

30 THE MANSION FIRE

3. Donald Meyers. “Governor’s mansion remodeled, restored to Victorian splendor,” Provo Daily Herald , Utah State Archives (No date is mentioned, but context indicates this was August 1996.)

historic photos and drawings of the charred pieces to cast a replica of the original dome. After the new dome was assembled, craftsmen from EverGreene Painting Studios in New York City gave it a brilliant golden hue.

Back to Life

It had cost Thomas Kearns $350,000 to build his mansion at the turn of the twentieth century. The $7.8 million-dollar restoration brought the home back to its original 1902 style, with twenty-first century upgrades.

Work concluded in mid-1996, and the magnificent building officially reopened to tours on July 29, 1996, as Utah was celebrating its centennial-year anniversary of statehood.

“This is one of the most outstanding historic restorations in the country,” the Park Record newspaper quoted me as saying on July 6, 1996. “The painstaking work of the many artisans and craftsmen to restore this architectural treasure is remarkable. This is one of the great treasures of the state of Utah. Its reopening is a grand moment in our Centennial celebration.”5 Our family had been settled back in our Laird home for two years, but there was great happiness to have the Mansion restored to glory—and back in our lives.

We used it regularly for meetings, ceremonies, and grand events. Guests, both of the family and

the state, stayed there, and the building was filled with light and life again for holidays and special occasions, such as the Winter Olympics in 2002.

“ This is one of the most outstanding historic restorations in the country.”

And ten years after the fire, a First Family moved back in. I had accepted an appointment from President George W. Bush to head the Environmental Protection Agency and was succeeded as governor by Lt. Governor Olene Walker, who was sworn in as Utah’s first woman governor on November 5, 2003. She and her husband, Myron, moved in that fall.

A few weeks later, she invited KSL-TV over to see the building decked out for Christmas and told them of her plans to celebrate the holiday there with six of her seven children, and twenty-five grandchildren. Christmas trees sparkled throughout the building, lit up in all its finery.

“It is beautiful,” Olene said. “And I didn’t even have to put a string of lights up.”

31 CHAPTER 2

5. “Public invited to tour newly restored governor’s mansion.” Park Record , Utah State Archives, 6 July 1996.

Jacalyn Smith Leavitt

By Laurie Sullivan Maddox

Life was going very well, in Jackie’s estimation, when her husband decided to run for governor. She was hesitant, foreseeing that it would impact all their lives in untold ways. “He wanted to do it, he had spent time thinking it through, and I will say I absolutely had doubt. It changes your lifestyle, and it impacted our lives.”

There were so many positives, though, about the endeavor, the public trust, and the life it brought, she says.

The difficulty she foresaw—and then lived— was how to lighten the load on the children. “I said to Mike, ‘Can’t we do this when they’re older?’ I felt things were stable, they’re progressing. And he just felt the timing was right. He has a phrase, ‘You have to catch the wave, and the wave is here.’”

With that, Jackie became supportive but remained concerned for the children. Once she grew accustomed to the role, and the years passed, others in high-profile public positions came to her for advice, eager to know how she had guided her own kids through it.

“I always tell them there are real challenges when you have children who are not grown up. It can have more of an impact on them. Also, each child will respond differently depending on how they handle challenges—and depending on their age.”

32

03

That is the primary reason she placed so much emphasis on regular things, making sure each child did their chores, made their beds, and picked up their clothes, even though there was housekeeping help at the Mansion. “Because that’s life,” she says.

Routines beyond chores were just as important, including all of the typical school and extracurricular activities, plus family time and church. “Particularly with the differing personalities among the kids, if you don’t have those routines,” Jackie says, “it just doesn’t work so well.”

Family living at the Mansion was a big initial adjustment, and then was reshuffled again just ten months into the term by the Christmas fire. Once back in the family home on Laird Avenue by mid1994, much of the pressure subsided.

The best part of the new lifestyle and the association with high office, Jackie says, was how interesting it was. The engagement in current events, the people she met around the state, and all the ways fellow Utahns were willing and able to commit to causes and projects that helped others.

Another fulfilling aspect was her own impact on projects and events—the First Lady initiatives she associated herself with from the beginning of the Leavitt Administration, working on them throughout the time in office and long after.

Jackie’s premier efforts were the Immunize by Two and Baby Watch childhood immunization and health programs; the Governor’s Initiative on Families Today (GIFT); and its subsidiary, the Utah Marriage Commission.

More were developed in the second and third terms in office: the literacy-boosting Read to Me campaign for children; the Worth Remembering series of books she wrote, emphasizing values associated with events such as the 2002 Winter Olympics and state centennial; and a series of children’s books and far-reaching programs tied to Faux Paw the Techno Cat, all part of the Internet Keep Safe Coalition, which Jackie further developed and advanced during the follow-on years in federal service.

First Lady Confidence

By the second term of office, the job of First Lady had become second nature for Jackie. Meshing the public and private roles while managing kids, household, initiatives, invitations, and expectations smoothed out over time, as did the ease of saying yes—or no.

Saying no had been nerve-wracking early on, particularly for one so gracious, who felt obliged to be all things to all people.

Very soon after the family had moved into the Mansion in February 1993, the governor was in demand as a speaker at the Republican Lincoln Day dinners typically held around the state that same month. He had accepted an invitation from the Davis County GOP, but a trip to Washington, D.C., bumped it from his schedule. Jackie was asked by a campaign supporter to go in his place.

Swamped with the move into the Mansion and so many comings and goings, she still accepted. “It was so long and crazy!” she recalls. “They were giving away loaves of bread, and everybody was speaking, and I’m thinking, ‘Oh, I got to get home to my kids!’”

She stayed to the end, and then worried later whether her remarks had been too saccharine or apolitical. “It was way too long, and it lasted so late. You come to realize you just do not have to say yes to everything. It was fine if Mike couldn’t make it. People understood that he was in D.C.”

It took a year, Jackie says, to decline some invitations, say no to competing requests, and resist the pressure to accommodate everything and everyone.

During the campaign she had attended numerous events and spoken publicly, an activity she enjoyed because of her comfort with performing and her college education in speech and drama. She also enjoyed visiting with people and did not consider herself shy. Impassioned political speechmaking, however, was her husband’s forte, not her thing.

Mrs. Bangerter had simple descriptors about how to carry oneself in public settings. “Put on your First Lady confidence,” was one. The other was about adopting a certain tone, inflection, or projection. “You have to use your voice in ‘that way,’” she advised.

33 CHAPTER 3

34

JACALYN SMITH LEAVITT

1 Jackie singing the “Star-Spangled Banner” at Rice-Eccles Stadium for the Fourth of July celebration.

2 Franklin Elementary School, third grade, December 14, 2001

3 Artist Series at Governor's Mansion

4 Governors Initiative on Families Today, (GIFT)

1 2 3 4 5

5 Immunize by Two event at Hogle Zoo

“That was something that took some practice because you have to say more than ‘Hello’ when introducing yourself when talking to groups,” Jackie says. “You have to express yourself and express ideas more perfectly than in a casual conversation. These are not casual conversations. They expect you to have something important and polished to say. I realized I needed to shine up my First Lady persona.”

“It isn’t that you aren’t approachable or caring. It’s just . . . you have to be ‘On.’ You have to be alert, and you have to be ready. How many times when you just go into a meeting you’re just there to listen and look? No, you have to be ‘On.’”

“ You need to do this job the way that suits you, that you feel comfortable with. ”

Jackie felt her persona was that of a teacher, and she engaged with others in that fashion—someone welcoming and glad to see you, interested in what you had to say. When it came to policy or issues, she demurred, except for those she had specifically put herself forward to promote or felt fluent in discussing.

Family Safety

Family safety was not an everyday concern, and the ever-present security detail, who had offices at the Capitol and Mansion, and a makeshift office later at the house on Laird, was always reassuring. “We always knew they were on our side,” she says.

Jackie recalls two threats involving the children that the detail, headed by Alan Workman, acted upon quickly. One was a man who had communicated something to the Governor’s Office about knowing what time the children went to school. The First Couple wondered if someone was parked outside the Mansion, watching. Or if it was something even more sinister.

Executive Protection would analyze how real a threat was, she says. In the case of the schooltime stranger, they investigated and did not go into depth or provide any details, simply telling Jackie, “This has been resolved.”

The security detail regularly kept a list of people who had come to their attention for any number of reasons, whether a questionable remark, cyberbullying of the kids, or something more. One of the boys had come across the list one day taped up inside the security office at the Mansion and was surprised by it.

The kids heard mentions of things from time to time. A school friend had once informed Chase that he knew about “someone who wants to kill your dad,” Jackie says. That happened more than once, and security would “jump on it and try and figure out if it was a real threat.”

Sometimes, everyday life had its perils. On a walk one evening, Jackie says, a BB whizzed past her eye and ear, missing the eye by micro-millimeters. It was just a few kids in the area goofing off with a BB gun given as a birthday present, but Jackie counted herself lucky. Another time on a walk in the avenues neighborhood she was bit by a dog and knocked down.

There was one occasion Jackie knew of when Alan Workman had to stop a man who headed aggressively toward the governor at an event after expressing some displeasure with his position on an issue.

Security matters were kept discreet for a reason, she says, even simple questions from people asking how many security officers guarded them. “We’d say there are enough, or, they do a great job.”

Being First Lady—Her Way

Among the hardest aspects of the lifestyle were the demands on her husband’s time, which Jackie found “difficult and excessive.”

The governor had explained it in general terms. He envisioned the commitment as a set duration of time proscribed by the term of office itself, and then a carve-out of daily hours within that time which a

35 CHAPTER 3

36

JACALYN SMITH LEAVITT

1 Speaking at the lunch for the International Daughters of Utah Pioneers

2 Read to Me campaign photo

3 Faux Paw the Techno Cat

4 Westin and Jackie at Centenarian Brunch for 100 and older

5 The “Motherhood Awards.” Around Mother’s day, twenty mothers were selected for an award and received praise and gifts.

1 2 3 4 5 6

6 Baby Your Baby Press Conference at the Governor’s Mansion

responsible public servant is obliged to give. Emergencies and various calamities demanded even more of his time than he thought, however. She had discussed all this with her husband and agreed with his assessment—in theory, if not always in practice.

“He was well-intentioned, but I don’t think it can easily be done,” she says. “I know he spent at least twelve hours every day and he was gone a lot. And it’s the way the office is.”

Going to National Governors Association (NGA) conferences each summer was always helpful and refreshing for all of them because there was a children’s itinerary alongside the adult sessions, plus fun and interesting off-time with sites to see and things to do, all arranged by the NGA.

First ladies who were currently serving would present on topics ranging from first-spouse initiatives and governor’s residence issues to keeping the marital relationship strong and not neglecting the marriage while in office.

“They clearly did say, ‘You need to do this job the way that suits you, that you feel comfortable with,’” Jackie says.