Quando a arte passou a fazer parte da vida de Claudia Andujar, ela carregava consigo a lembrança de, aos 13 anos de idade, ter voltado para a sua casa, na Hungria, e encontrado a mesa de jantar feita, porém vazia. Durante a refeição, o seu pai fora deportado para um campo de concentração nazista, onde foi morto com parte de sua família paterna. Ao tornarse artista, vivendo no Brasil, ela se dedicou a se aproximar dos povos em perigo, como (ainda) o são as mulheres, os homossexuais e os povos da floresta. Sua concepção de arte fundiu-se com a vida, tornou-se experiência. A exposição Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão, com curadoria de Eder Chiodetto, propõe um percurso por seus experimentos, esses que a conduziram à dimensão de iluminar histórias distintas. Este catálogo é um registro visual dessa trajetória, analisada em textos a partir do olhar dos pesquisadores Thais Lopes Camargo, Ronaldo Entler e Peter Pál Pelbart. Carlo Zacquini e Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, companheiros de luta da artista, também nos oferecem seus pensamentos e testemunhos das travessias vividas ao seu lado em seu esforço permanente para garantir a existência do outro. Nessa busca, Claudia Andujar expandiu as fronteiras da linguagem fotográfica. E, ao fazê-lo, tinha um objetivo: afetar os espectadores com a presença de múltiplos universos e ser afetada por eles da mesma forma. É quando o ato de fotografar reinventa narrativas e processos luminosos, e a produção de imagem passa a dar conta de mostrar, também, aquilo que se enxerga apenas de olhos fechados: sonhos e espíritos. Esses ganham cores e texturas em imagens feitas pela artista que compactuam com a permanência da vida e, ao fazê-lo, ampliam a nossa ideia de coexistência entre tantos mundos.

Na Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural (itaucultural.org.br), é possível encontrar outras informações relacionadas a Claudia Andujar e sua contribuição para a arte e o ativismo. Reconhecido com o Prêmio Milú Villela –Itaú Cultural 35 Anos, o trabalho da artista marca um olhar para a formação social do Brasil e a salvaguarda dos seus povos originários.

Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão

Eder Chiodetto

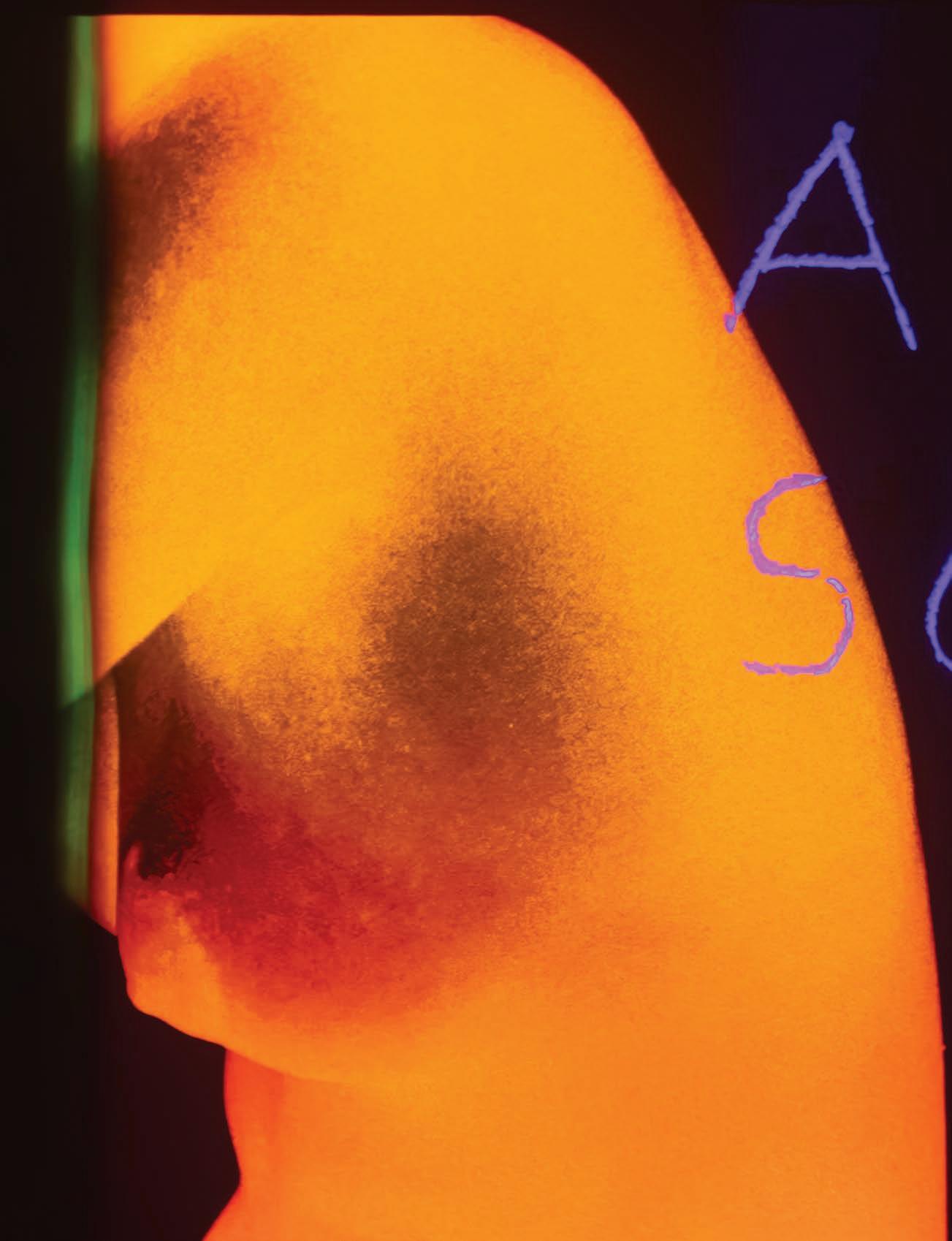

Pesadelos, 1970

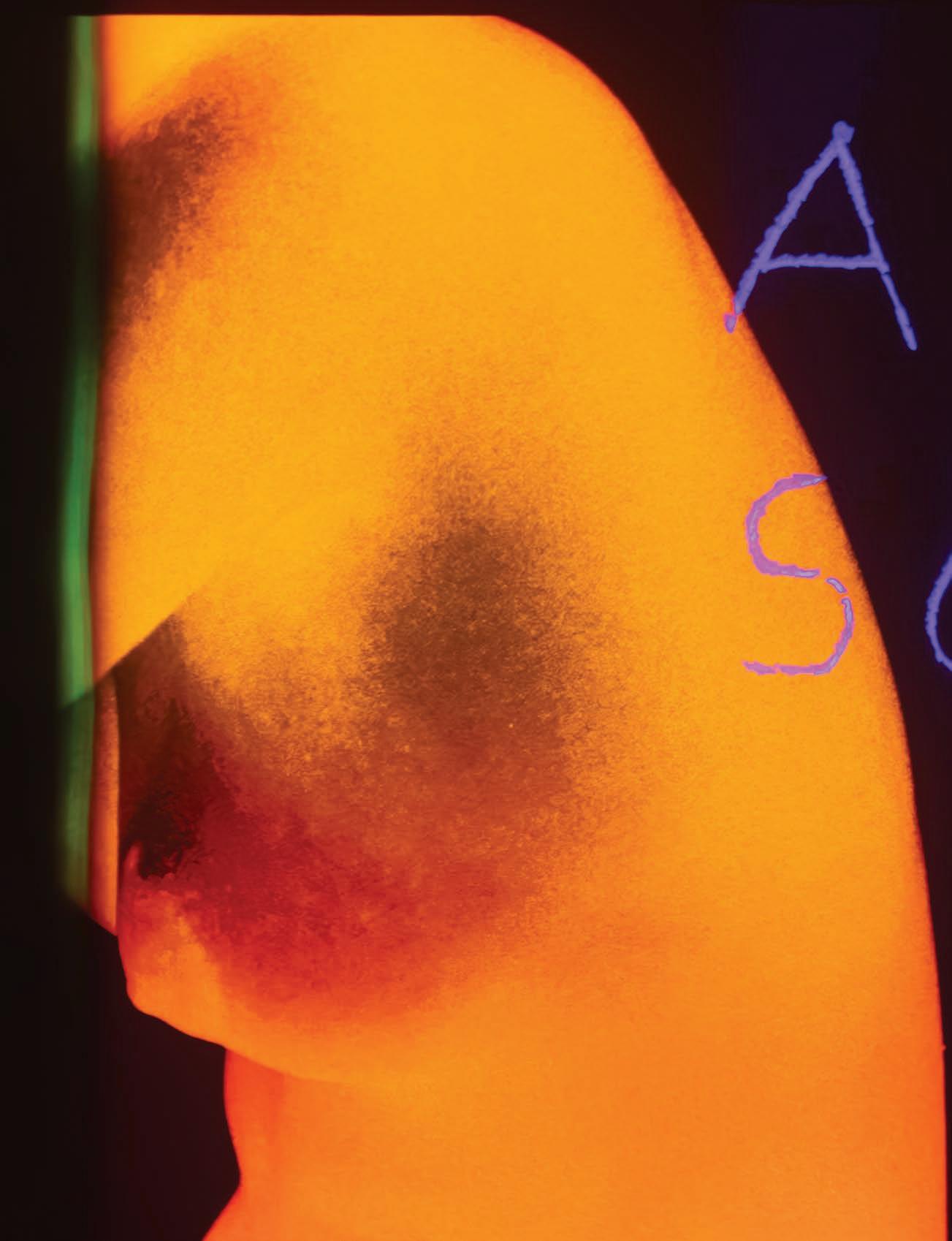

Homossexuais, 1967

Minha vida em dois

mundos, 1970

Cidade gráfica, 1970-1974 A

, 1978

Entre mídias, entre mundos

Thais Lopes Camargo

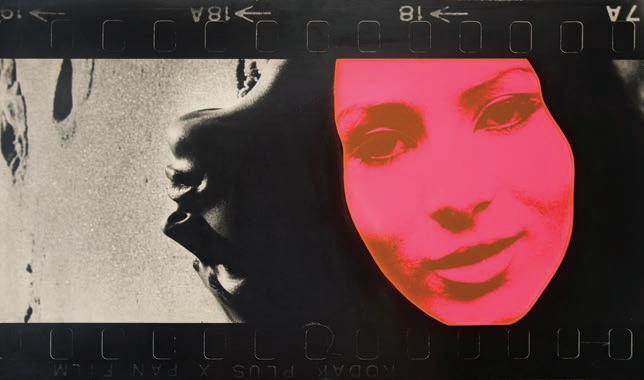

A Sônia, 1970

Um fusca preto, a Amazônia e a salvaguarda dos povos Yanomami

Carlo Zacquini em diálogo com Mariana Lacerda

O voo de Watupari, 1976-2024

Arco da vida

Peter Pál Pelbart

Malencontro, 1980-1989

Amar a terra-floresta: eu conheci a alma dela

atrás do sorriso

Davi Kopenawa

Yanomami em diálogo

com Isabella Guimarães

Rezende

O sonho verde-azulado, 1972-1982

Reahu, o invisível, 1974-1976

Sonhos Yanomami, 2002

Cronologia

Thais Lopes Camargo

English content

Captions Ficha técnica | Credits

Certas artistas, na obsessão pela legítima e precisa expressão, não se atêm a fazer o uso da linguagem de forma tradicional e passiva. Rompem estatutos e, pautadas por intuição, alguma rebeldia e muitas experimentações, criam novas possibilidades formais, simbólicas e narrativas no campo da investigação artística. Essas são artistas que expandem o léxico das linguagens e se tornam referências para a história.

É o caso da fotógrafa e ativista Claudia Andujar, que nasceu em 1931, na Suíça, e veio para o Brasil em 1955, refugiada do nazismo. Esta exposição, de caráter inédito, visa mostrar como a artista manejou de várias formas os registros fotográficos por meio de estratégias que a levaram a fundir de modo original o registro documental e jornalístico com expressões artísticas e subjetivas.

Reconhecida mundialmente pelo seu complexo e abnegado trabalho com os Yanom a mi, Claudia usou a arte para denunciar o descaso histórico do Estado com esse povo. Ao fazê-lo, produziu em imagens a sabedoria ancestral e a refinada espiritualidade dos povos originários desta terra. A força dessa produção iconográfica, não por acaso, domina quase por completo a vasta bibliografia e os projetos expositivos da artista.

Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão , além de enaltecer essa trajetória, mostra como a inquietude e a inventividade dessa artista diante da linguagem fotográfica foram fundamentais para que, em sua maturidade, ela conseguisse representar poética e enfaticamente dimensões não visíveis – o que parece uma questão paradoxal para a fotografia –, como as imagens oriundas da miração dos Yanom a mi em seus rituais xamânicos.

Entre as dez séries exibidas na exposição e reproduzidas nesta publicação, Claudia mostra grande desenvoltura para criar tensões e atmosferas inesperadas nos registros fotográficos por meio de experimentações, desde o momento em que atuou como fotojornalista na revista Realidade (de 1966 a 1971), atitude correlata

ao espírito libertário e comportamental que predominou na geração pós-1968.

A atuação de Claudia no Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), de 1971 a 1976, ministrando aulas, organizando exposições e coordenando o departamento de fotografia ao lado do artista George Love (1937-1995), foi paradigmática para que a fotografia fosse finalmente legitimada dentro do campo da arte no Brasil e começasse a ser incorporada ao acervo dos museus.

No final dos anos 1960, uma novidade tecnológica mobilizou artistas, entre eles Claudia e Love, a criar possibilidades de exibir imagens: o projetor de slides. A ideia de a fotografia still se tornar um “quasi-cinema”, como apregoava Hélio Oiticica, impulsionou a exibição da série A Sônia, que Claudia levou ao Masp em 1971, como uma projeção audiovisual. Pela primeira vez, 53 anos depois, essa obra é recriada – a partir de pesquisa feita pela assistente de curadoria Thais Lopes Camargo – por Leandro Lima, artista que já realizou outros projetos em parceria com Claudia.

As séries que compõem a exposição e o catálogo Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão dão a ver, ainda, o uso de filmes infravermelhos, de cromos com a película arruinada e de filtros monocromáticos, assim como de imagens refotografadas com distorções e mutações de luzes e cores, justaposições e duplas exposições, entre outras estratégias criadas pela artista para aproximar a representação da percepção sensorial, o testemunho documental da visão crítica e onírica.

A cosmovisão dos Yanomami, que amplia e aprofunda os sentidos das existências, encontra aqui uma relação análoga na atuação de Claudia com a fotografia, que ela faz atravessar fronteiras para representar dimensões que estariam fora do alcance dessa linguagem. A fotografia deixa de mimetizar uma visão para ter a potência de uma cosmovisão.

É o que acontece na série Sonhos Yanomami. De certa forma, esta exposição foi pensada a partir do percurso experimental percorrido por Claudia para culminar justamente nessa série. Após

décadas frustrada por não conseguir representar as imagens das mirações que os indígenas relatavam ao retornar do transe xamânico, a artista finalmente obteve êxito trazendo à luz representações até então verbais quando, por acaso, sobrepôs cromos na mesa de luz em que editava seus trabalhos. A sobreposição das imagens havia gerado uma terceira fotografia, que lhe chamou atenção.

Acasos acontecem a alguns artistas a fim de provocá-los a ir além na lida com a sua matéria investigativa. Atenta aos sinais, Claudia percebeu, na fusão dos cromos, ou seja, na soma de dois ou mais tempos-espaços distintos, a formação de uma temporalidade outra: não o tempo linear do Ocidente, mas o tempo elíptico e sagrado que os Yanomami professam.

No segundo semestre de 2023, estimulada pelas ideias, pela produção e pelos conceitos desta exposição sobre suas práticas mais experimentais, a artista reviu a série O voo de Watupari, registro da viagem que realizou com seu fusca, em 1976, de São Paulo até o território Yanomami em Roraima. As imagens, em preto e branco, ganharam a sobreposição de peças de acrílico colorido. Agora, as cores conferem a esses registros, feitos em ritmo de diário de viagem, um caráter pop e lisérgico. Ao registro documental justapõe-se um prisma que sinaliza uma visão múltipla, crítica, que refuta a certeza que as fotografias cismam em querer afirmar.

Um belo gesto dessa artista que, aos 92 anos, espia novamente pelo retrovisor de seu “carrinho”, como ela diz, e percebe que sua viagem pelo Brasil e pela linguagem fotográfica tem sido uma jornada de transformações profundas para si mesma, para o povo Yanomami (que a chama de mãe) e para a fotografia, que terá em Claudia Andujar sempre um farol a iluminar as novas gerações. Os registros fotográficos da viagem que a levou de vez em direção à sua causa humanista e ativista, fundamental para a demarcação da Terra Indígena Yanomami, têm agora uma nova versão, que dialoga com o espírito libertário e lisérgico da época que inspirou uma das artistas mais instigantes do nosso tempo.

É o curador da exposição Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão. Nascido em 1965, em São Paulo, é jornalista e mestre em comunicação pela Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Foi repórter, crítico e editor de fotografia do jornal Folha de S.Paulo entre 1991 e 2004. Atua, desde 2004, como curador de fotografia independente. Em 2011, fundou o centro de estudos Ateliê Fotô e, em 2016, a editora de fotolivros Fotô Editorial. Foi membro do conselho de artes e curador de fotografia do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM/SP) entre 2005 e 2021. Entre 2019 e 2020, foi mentor do programa Arte na fotografia, no canal Arte1. Como curador, já realizou mais de 160 exposições no Brasil, na Europa, nos Estados Unidos e no Japão. É autor dos livros O lugar do escritor (Cosac Naify, 2002), Geração 00: a nova fotografia brasileira (Edições Sesc, 2011), Curadoria em fotografia: da pesquisa à exposição (Ateliê Fotô/Funarte, 2013) e Ser diretor (Ateliê Fotô, 2018), entre outros. Como editor, coordenou publicações de artistas como Rosângela Rennó, Eustáquio Neves e Luiz Braga.

Sem título, 1972 série Magia transparente acrílico e fotografia analógica em preto e branco Acervo da artista

Bichos apavorantes, seres mutantes sinistros, imagens instáveis e ameaçadoras. Em fevereiro de 1970, Claudia Andujar publicou um ensaio fotográfico na revista Realidade para ilustrar uma reportagem sobre os avanços da ciência no campo psíquico. O recém-inventado eletroencefalógrafo começava a desvelar a origem dos pesadelos, “a mais terrível experiência psíquica que o homem pode ter”, segundo Edwin Diamond, autor da reportagem. Claudia demonstra sua desenvoltura técnica e conceitual ao propor imagens enigmáticas e perturbadoras por meio de sobreposições, mutações cromáticas e descolamento da gelatina do negativo ao revelá-lo com altas temperaturas. Um gato e uma boneca, entre outros elementos de sua casa, protagonizaram as fotografias.

Em 1967, Claudia Andujar fotografou, para a revista Realidade, os “entendidos” (como eram chamados os gays na época) em bares, boates e ruas das cidades de São Paulo e Rio de Janeiro. Ela também levou um casal de rapazes ao seu próprio apartamento para fotografá-los como em uma fotonovela. Para ocultar suas identidades, a então fotojornalista fez uso de recursos da linguagem fotográfica, com composições que ocultavam os rostos e privilegiavam as silhuetas obtidas em contraluz, com baixa velocidade de obturador para borrar a cena.

Apesar desses recursos, a reportagem foi publicada sem as fotos, que foram vetadas por se tratar de um tema ainda tabu no Brasil sob a ditadura militar. Com o título “Homossexualismo”, o texto tinha um viés opressor. É o que mostra a chamada da reportagem: “Na Idade Média, eles eram queimados vivos. Hoje são considerados criminosos em muitos países… O jornalista viveu o mundo triste e desumano dos homens que negam sua condição de homens”.

Foi apenas em 1990 que a Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS) retirou o “homossexualismo” da lista de distúrbios mentais. O sufixo -ismo, que indica uma patologia em medicina, cairia em desuso e seria trocado pelo sufixo -dade, com “homossexualidade” referindo-se a uma orientação.

Causa espanto que essas mesmas fotografias, 56 anos após terem sido realizadas, ainda tenham suscitado polêmica na Hungria. Em 2023, a série foi classificada como imprópria para menores de 18 anos na mostra individual da artista realizada no Museu de Etnografia de Budapeste. Uma faixa de advertência cercando as imagens e um vigilante na porta do espaço expositivo foram exigidos pelo governo de extrema direita húngaro para que as imagens permanecessem no local.

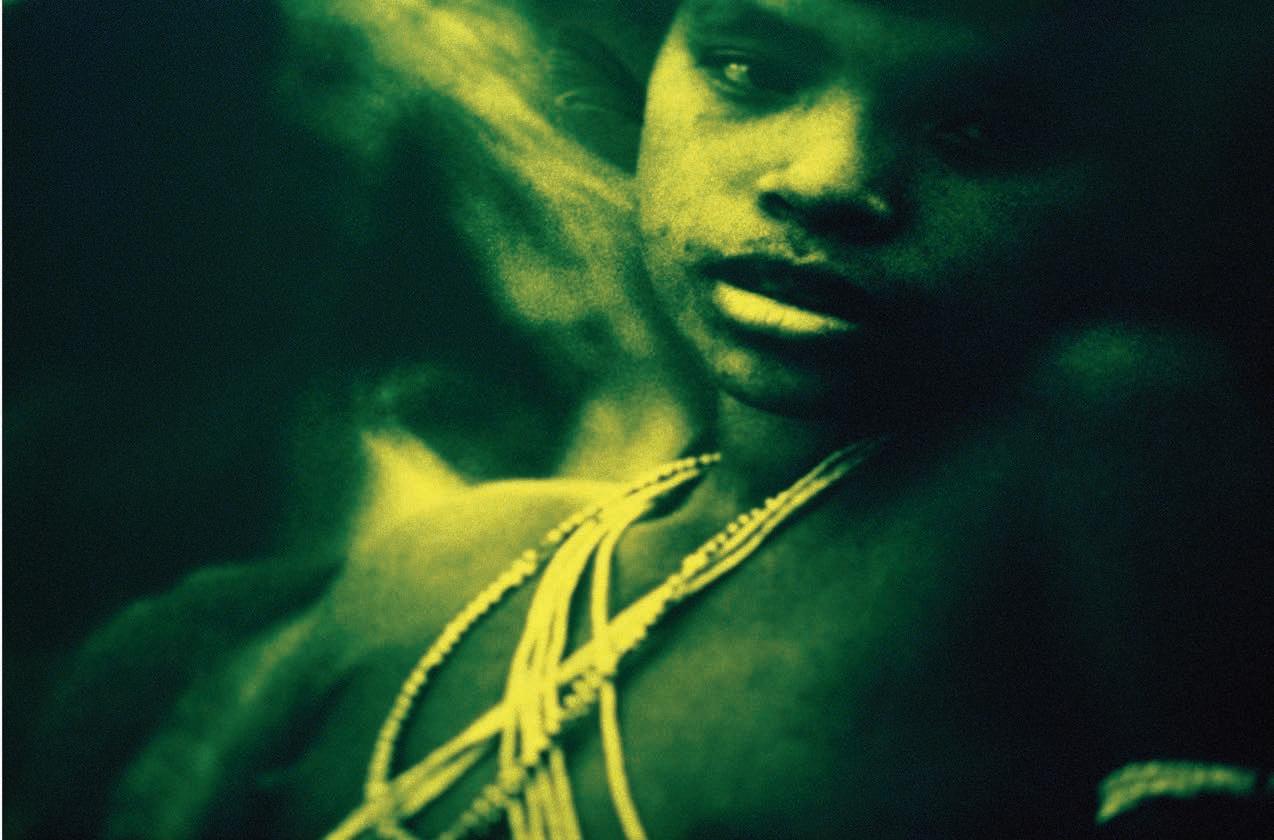

Entre as experimentações que visavam descobrir novas fronteiras de representação via fotografia, Claudia Andujar investiu com afinco nos filmes infravermelhos, que ela obtinha em viagens fora do Brasil, já que o seu uso aqui era controlado pelas Forças Armadas por questões de segurança. Criado um pouco antes e usado largamente na Segunda Guerra Mundial, o filme infravermelho tem a capacidade de registrar imagens pela detecção de zonas de calor, possibilitando, por exemplo, encontrar um inimigo escondido durante um ataque. Em seu uso artístic o, Claudia se valeu da mutação cromática na qual o verde se transforma em vermelho sanguíneo quando fotografado com esse recurso. Dessa forma, ela fez mais de uma vez com que a floresta em torno dos Yanomami se tornasse uma perturbadora imagem que emulava o sangue derramado nas invasões das aldeias ou o fogo criminoso na mata.

Nos anos 1970, a artista sobrevoou São Paulo e fez registros com esses mesmos filmes. Com ar futurista e distópico, a urbe surge entre luzes ácidas e árvores vermelhas, com uma aparência sinistra.

1970-1974

Claudia Andujar mora há décadas no 20o andar de um edifício localizado na Rua São Carlos do Pinhal, paralela à Avenida Paulista, em São Paulo (SP). De seu apartamento, ela tem ampla vista para a cidade. As janelas de sua sala funcionam como um visor de câmera pelo qual observa as mutações da capital paulista, na qual ruína e construção quase se confundem. A partir dessa observação, Claudia editou imagens feitas em 1970, finalizando essas justaposições em 1974. O conjunto torna ainda mais aguda a sensação de um contexto urbano emaranhado entre esquadrias, fios e prédios que não oferecem saída ou horizonte.

Claudia Andujar atravessou muitas fronteiras. Algumas viagens eram busca, outras exílio, mas todas conjugavam afeto e política. No meio do caminho, começou a produzir imagens. Elas foram se tornando difusas à medida que tentavam enquadrar mais do que o visor da câmera permitia ver. Claudia aprendeu a se sentir em casa em lugares para ela distantes, partilhou muitas histórias sem dominar os idiomas, sentiu a dor alheia em suas próprias feridas. Fez da sobrevivência do outro uma questão crucial para a sua existência. Foi cruzando fronteiras que descobriu a importância do território. É preciso que ele exista para que haja pertencimento e, ainda, a experiência da travessia e do acolhimento.

pela ditadura militar (que, em seguida, chegaria a outros países da América Latina); de outro, o fortalecimento dos movimentos sociais, que, aqui e ao redor do mundo, respondiam a urgências diversas: cerceamento de direitos civis, guerras, políticas coloniais, genocídios etc. Atravessada por esse contexto, Claudia se interessou de modo crescente pelos debates sociais e ambientais, na mesma medida em que encontrava no jornalismo um espaço cada vez mais refratário às pautas e às experimentações que lhe interessavam.

Desde que deixou a Hungria, com 13 anos de idade, Claudia fez um longo trajeto até chegar ao Brasil, aos 20 e poucos anos. Buscou seu lugar no mundo seguindo os passos de familiares, que, sob o impacto da Segunda Guerra Mundial, tiveram destinos muito diversos. Quando se instalou em São Paulo, em 1955, Claudia já trazia uma vivência como artista. Aqui, ela trocou a pintura pela fotografia e, com a câmera na mão, transitou por cidades do Brasil e da América Latina, desta vez construindo seu próprio caminho.

Sua inserção no mercado da fotografia foi difícil e, no início, seu trabalho encontrou mais espaço fora do que dentro do país. Em 1966, quando ela se tornou parte do seleto time de freelancers da revista Realidade, da Editora Abril, o Brasil já havia se tornado uma ditadura militar. Por algum tempo, ela ainda encontraria, naquele contexto de conservadorismo crescente, as brechas possíveis para fazer do jornalismo uma experiência contracultural, abordando temas polêmicos como corpo, sexualidade, drogas, loucura, imigração, misticismo, exclusão social e diversidade cultural.

Ao final daquela década, Claudia assistiu a dois movimentos não apenas concomitantes, mas profundamente interligados: de um lado, o recrudescimento das violências produzidas

A edição especial da revista Realidade sobre a Amazônia, de 1971, representa bem o momento em que essa tensão se estabeleceu. Foi seguindo pistas para a sua reportagem que Claudia chegou a Maturacá, no Amazonas, e teve seu primeiro contato com os Yanomami, com quem viria a desenvolver um forte vínculo político e afetivo. Pressionada pela censura, a relevância da revista logo se dissolveria com o desmantelamento de sua equipe e o fim das pautas investigativas com que havia feito história. Em 1968, Claudia tinha se casado com o fotógrafo estadunidense George Love, que, naquele momento, já havia construído uma trajetória profissional no Brasil e também integrava a equipe da Realidade. Mas foi apenas ao deixar a revista que o casal começou a realizar trabalhos em parceria. Em 1971, eles se tornaram colaboradores do Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), oferecendo cursos, orientando a aquisição de obras para o acervo e organizando exposições.1 Naquele mesmo ano, Claudia foi contemplada com uma bolsa da Fundação Guggenheim, que lhe permitiu viajar com George ao encontro de outra comunidade Yanomami, que vivia às margens do Rio Catrimani, em Roraima. Ali ela conheceu Carlo Zacquini, que se tornaria seu amigo e parceiro em muitos projetos.

Claudia Andujar resiste a estabelecer relações diretas entre o seu trabalho fotográfico e as suas primeiras experiências artísticas, focadas na linguagem da pintura,2 mas é evidente que, já nas pautas feitas para a Realidade, ela adotava

procedimentos pouco familiares ao campo do fotojornalismo. Com alguma frequência, ela refotografava suas imagens, acrescentando filtros e luzes ou sobrepondo fotos. Para o olhar que fez da fotografia uma ferramenta de escavação das aparências, não será muito produtivo distinguir entre documentação e experimentação estética, entre registro e agenciamento. Precocemente, Claudia descobriu algo que seria fundamental para pensar o trabalho que faria com os Yanomami: às vezes, é preciso manipular a imagem para ajustá-la à realidade.

Os experimentos com a cor já eram uma característica marcante do trabalho de George Love, fotógrafo reconhecido pelo domínio que tinha dos processos técnicos da fotografia e da impressão gráfica. Em algumas entrevistas, Claudia assume essa influência,3 mas seria enganoso reduzir suas inquietações aos caminhos já traçados por George. Em muitos sentidos, sabemos que o trabalho dela é menos movido pelo sentimento de segurança do que pela disposição para o risco. Apesar dos importantes parceiros e interlocutores que teve em sua vida, ela sempre soube enfrentar por conta própria, e às vezes de forma solitária, as fronteiras dos territórios, das linguagens e dos tabus.

Com a colaboração de Claudia e George no Masp, a fotografia ganhou um espaço importante de formação e pesquisa. Na esteira do Museu de Arte Moderna de Nova York (MoMA), que, em 1940, criou um departamento de fotografia, diversos museus do mundo começaram a formar acervos e acolher programações dedicadas a essa linguagem. Não cabe retomar o infrutífero debate sobre a dignidade artística dessa técnica. Fato é que a fotografia, que já tinha um lugar privilegiado na cultura de massa por meio da página impressa, começou a encontrar espaços mais sistemáticos nas paredes e nas programações dos museus de arte.

No Masp, Claudia e George realizaram uma série de experimentos com o audiovisual, como foram chamadas as narrativas que articulavam som (geralmente música) e projeção de fotografias. Naquele momento, o projetor de slides impactava as formas de fruição da fotografia, ampliando

a escala da imagem e construindo por meio dela um ambiente imersivo. Essa tecnologia já havia conquistado um espaço importante nas salas de aula e nas salas de visita de fotógrafos amadores, e, na mão dos artistas, expandia as formas de exibir narrativas e de ocupar os espaços expositivos. Nessa perspectiva, os trabalhos com audiovisual realizados por Claudia e George no Masp aproximaram a fotografia das linguagens da instalação e do happening

Além de explorarem como tela superfícies de escalas e materialidades diversas, tecnologias acessórias, como o dissolve control, permitiam aos artistas coreografar a ação de vários projetores, criar efeitos de fusão na passagem entre um slide e outro e sincronizar imagem e som. Pelos efeitos dinâmicos que o audiovisual dava à fotografia, a comparação com o cinema é inevitável, sobretudo agora, quando o termo “audiovisual” nomeia a convergência do cinema, da televisão e dos jogos eletrônicos. Mas, num contexto artístico que investia na dissolução das fronteiras entre as linguagens artísticas, essa expansão da fotografia tem menos a ver com a intenção de compensar uma defasagem da imagem estática do que com o desejo de ocupar um lugar indefinido, de estar na posição de um “quasi-cinema”, para usar uma expressão cunhada por Hélio Oiticica nesse mesmo período. Diferentemente da imagem emoldurada e pendurada na parede, o audiovisual se assumia muitas vezes como imagem impura, em que os dispositivos, o emaranhado de fios e os ruídos do aparelho se tornavam parte da obra.

Não é simples reconstituir os experimentos feitos por Claudia e George no Masp, entre outras coisas, porque a projeção dá à fotografia uma existência volátil e uma espacialidade mais complexa se comparada às impressões fotográficas que já tinham encontrado lugar adequado nas reservas técnicas dos museus. Mas essa instabilidade interessa profundamente a Claudia Andujar, que sempre pensou a fotografia como matéria viva e, por isso, nunca se contentou em fazer do arquivo o lugar em que obras prontas repousariam em paz.

A Sônia (1971), uma das instalações audiovisuais que Claudia apresentou no Masp, parte de um ensaio feito com uma mulher negra que tinha vindo da Bahia para São Paulo e tentava sem sucesso construir uma carreira como modelo. A série, que teve também uma versão impressa publicada numa revista editada por George Love, era constituída de fotos manipuladas com alteração de cores e sobreposição de imagens. Na instalação, é possível que esses efeitos fossem intensificados pela fusão dos slides. Também não é difícil imaginar que a artista se identificasse com as interferências a que os audiovisuais estavam sujeitos, como luzes que podiam vazar para dentro da sala e outros corpos que, eventualmente, atravessavam a projeção.

O corpo é uma questão-chave desse trabalho, mas ele não é aqui reduzido a uma paisagem de formas sensuais. Claudia sabe que, assim como muitos dos personagens de suas reportagens, e como os Yanomami, o corpo de Sônia transitava entre a invisibilidade e a curiosidade exótica de boa parte dos consumidores de imagens. A seção de fotos com ela foi embalada pela música “I had a dream”, na versão ao vivo cantada por John Sebastian no Woodstock, que ainda se tornaria a trilha sonora do audiovisual exibido no Masp. Os sonhos, representados também pelas imagens difusas e pela materialidade volátil da projeção, ganham aqui o sentido de uma utopia, seja aquela que trouxe Sônia a São Paulo, seja a que levou multidões a Woodstock.

As colaborações de Claudia no Masp aconteceram em meio a diversas viagens que fez entre São Paulo e a Amazônia. Em 1974, após uma longa temporada que ela passou sozinha fotografando os Yanomami, Claudia e George se separam. Mas seguem trabalhando juntos no museu até 1976, quando deixaram a instituição, e também no projeto do livro Amazônia, publicado em 1978. Desde que fez a primeira incursão ao Catrimani, em 1971, Claudia teve uma colaboração intensa de Carlo Zacquini, missionário italiano que atuava na região e tinha forte inserção na comunidade Yanomami.

Até cer to ponto, ela soube conciliar a vida entre esses territórios distantes e os anseios de uma produção que se movia entre a arte e a militância política. O desejo de partir para viver com os Yanomami está bem representado numa série de fotografias feitas em 1976, quando ela viaja com seu fusca de São Paulo a Roraima ao lado de Zacquini. Ali, vemos o edifício do Masp ficando para trás, num dia chuvoso, com ares de despedida. Na outra ponta da viagem, vemos o carro sendo levado de barco em direção à floresta. Acostumada a inventar dispositivos para a manipulação da imagem, Claudia converte seu fusca preto numa espécie de câmera escura que reenquadra a paisagem com o traçado característico de suas janelas.

Já na Amazônia, a baixa incidência de luz que encontra na mata fechada e dentro das malocas seria um problema se Claudia estivesse preocupada em mostrar a superfície mais nítida das paisagens e dos gestos que fotografa. Na série Reahu, o invisível (1976), que mostra os rituais funerários dos Yanomami, ela tira proveito dos borrões de movimento e dos pontos estourados de luz gerados pela longa exposição. Também recorre a filmes infravermelhos, filtros e lâmpadas a óleo, e borra os contornos da imagem passando vaselina nas bordas de um filtro que cobre sua lente. Nada mais adequado do que a escuridão para vasculhar aquilo que não está ao alcance do olhar.

Claudia sempre precisou de tempo para produzir e maturar seus projetos, um luxo ainda disponível naqueles anos da revista Realidade , mas cada vez mais raro no jornalismo e, de modo geral, numa cultura voltada para a produtividade.

Ainda que algumas de suas fotos tenham se tornado icônicas, ela sempre preferiu pensar seus trabalhos como ensaios ou séries que, às vezes, demoravam a se configurar. Uma imagem estática como a fotografia pode ser capaz de representar o tempo que antecede e sucede a cena captada. Esse recorte de tempo que arrasta consigo os momentos anterior e posterior foi chamado

de “instante pregnante” pela estética clássica. Isso era pouco para ela. No intervalo entre os cliques de uma dupla exposição, na duração das intervenções que reconfiguram uma imagem captada ou na latência de uma foto que permanece em seu arquivo até encontrar a ocasião de produzir sentido, Claudia gesta uma temporalidade que não é a do relógio e mostra conexões que não cabem no enquadramento do olhar. Assim, entenderemos que suas imagens operam mais ou menos à maneira dos mitos.

A relação de Claudia com os Yanomami não é mediada apenas pela fotografia e, na medida em que ela se envolveu com a preservação de sua cultura e de seu território, deixou muitas vezes a câmera em segundo plano. Em 1974, ela chegou ao Catrimani trazendo na bagagem papéis e canetas hidrográficas e convidou os Yanomami a produzir uma série de desenhos. Alguns colaboradores criaram grafismos semelhantes aos que estavam desenhados em seus corpos. Mas o projeto avançou numa direção mais complexa quando três deles começaram a traduzir no papel sínteses de suas narrativas míticas. Com a ajuda de Carlo Zacquini, que domina o idioma Yanomae, a produção dos desenhos foi acompanhada de um trabalho sistemático de coleta e tradução dessas narrativas. O resultado dessa pesquisa foi mostrado no livro

Mitopoemas Yãnomam, publicado em 1978. Se nem todas as camadas da realidade são visíveis, há também imagens que circulam sem a dependência do olhar. É esse potencial imagético da oralidade Yanomami que esses desenhos nos ajudam a enxergar.

Em contrapartida, parece que algo dos mitos sempre esteve presente nas fotografias de Claudia Andujar. Na tradução literal dos mitopoemas coletados por ela e por Zacquini, percebemos uma construção estranha à nossa linguagem, com sentenças pouco subordinadas, que nem sempre se articulam de forma linear. Há muitas repetições que demarcam a intensidade de um acontecimento. Há também um ir e vir das palavras que vai lentamente dando contorno à ação que se quer descrever:

Tudo acaba.

Céu desaparecerá.

Com os napepe4 todos caem.

Tudo acaba.

Cai tudo, de cima desce.

Tudo acaba, longe irá para o fundo.

Cai, tudo acabará.5

Como as sentenças dessas narrativas, as imagens de Claudia se constroem muitas vezes por gestos que se somam sem subordinação, por imagens e efeitos que se conectam por justaposição. As fotografias que ela acrescenta ao livro, impressas em páginas transparentes, operam nessa mesma chave. Não se podem reduzir as intervenções poéticas que Claudia faz em suas imagens a um mero efeito ornamental, como não se podem entender os mitopoemas como narrativas estilizadas. Chamar um discurso de “poético” significa reconhecer que sua forma é parte inseparável do conteúdo expresso.

Os mitos não são formulações abstratas, são reservas de conhecimento acumuladas a partir de vivências. De forma análoga, as fotografias de Claudia são imagens construídas, mas sempre a partir de apropriações de fragmentos da realidade. Ambos são discursos que interpretam o mundo e que, ao mesmo tempo, estão impregnados dele.

As teorias da imagem nos lembrariam de que essa conexão entre imagem e mundo – a indicialidade – é uma qualidade superestimada da fotografia analógica, definitivamente desmistificada pela fotografia digital, que, de forma mais evidente, é resultado de um processamento de informações. Isso é, aqui, irrelevante. Claudia Andujar nunca manifestou grande fidelidade à imagem captada pela câmera e, em trabalhos mais recentes, não deixou de utilizar as tecnologias digitais para realizar suas intervenções. O contato físico que está em questão não tem a ver com a formação técnica da imagem, mas com a produção de um sentido. Para ela, não bastou posicionar a câmera diante de um grupo de indígenas. Foi preciso conviver com eles para que suas imagens pudessem dizer algo sobre sua cultura. Mais do que isso: foram

a duração e a profundidade desse convívio, feito muitas vezes sem a câmera, que permitiram a Claudia perceber que seria preciso manipular suas imagens para dar conta de sua cosmologia. Não se trata da sensibilidade da película, mas daquela do corpo de quem fotografa. Apesar disso, não se pode negar que a câmera fotográfica – esse artefato que, ainda hoje, insiste em convidar os artistas a saírem a campo em busca de imagens – foi parte da motivação que a levou a lugares tão distantes.

A relação de Claudia com os Yanomami não se constrói apenas por meio de suas imersões naquele território. Foram necessárias muitas idas e vindas para enxergar as aproximações possíveis, mas também as distâncias que mereciam ser guardadas entre o seu mundo e o deles. Foi importante percorrer muitas vezes a Perimetral Norte para enxergar a catástrofe a que conduzia essa estrada. Foi preciso refazer o caminho de volta para que pudesse negociar, no território e no idioma dos invasores, as possibilidades de sobrevivência daquele povo.

Em 197 7, Claudia foi enquadrada na Lei de Segurança Nacional e expulsa do território Yanomami. No ano seguinte, junto com Carlo Zacquini e o antropólogo Bruce Albert, ela fundou a Comissão pela Criação do Parque Yanomami (CCPY), que teve papel fundamental na luta pelos direitos territoriais e culturais desse povo. A essa altura, suas fotografias já tinham constituído um corpo robusto que seguiu fazendo seu trabalho, levando a causa Yanomami para o mundo. As imagens têm vida própria e Claudia também soube dialogar com suas latências. Nos anos 2000, quando o território Yanomami já havia sido reconhecido pelo governo, ela retornou aos seus arquivos com a mesma disponibilidade para descobertas que a havia levado até a Amazônia três décadas antes.

Desse movimento surge a série Sonhos Yanomami (2002), em que Claudia sobrepõe retratos e paisagens para dar forma a outro universo de imagens da cultura Yanomami que circulam à revelia do olhar. É provável que, sob o pretexto de dar materialidade aos sonhos dos Yanomami, ela tenha encontrado em seus arquivos o modo como eles

habitam os sonhos dela mesma: como corpos em cuja pele um território sempre esteve demarcado. Não há contradição. Para os Yanomami, os sonhos representam uma dimensão expandida da realidade por meio da qual se pode tomar contato com os desejos de pessoas ausentes a respeito daquele que sonha.6 Se é possível percorrer essa distância, não é surpresa que os sonhos dos Yanomami tenham vindo habitar os arquivos de Claudia para dar forma ao afeto que a vincula a eles.

A série Marcados nasce de uma intervenção mais simbólica sobre imagens de um arquivo, mas nem por isso menos radical. A fotógrafa parte de retratos que fez entre 1980 e 1985 em razão da necessidade de identificar membros da comunidade Yanomami que estavam sendo vacinados por uma missão de saúde coordenada pela CCPY. Nessas imagens, vemos indígenas que portam em seus pescoços placas com numerações. Essas imagens se convertem em trabalho artístico quando, duas décadas depois, Claudia estabelece um paralelo entre esses corpos “marcados para viver” e aqueles dos judeus “marcados para morrer”,7 seja nos guetos, com a estrela de davi pregada em suas roupas, seja nos campos de extermínio, com números tatuados em seus braços. Esse paralelo não é uma tentativa de explicar um trauma local a partir de uma história mais universalizada. Tem a ver com empatia, sentimento raro que faz a dor do outro latejar um trauma inscrito em sua memória.

Em suas imagens, Claudia Andujar encontra lugar para diversas modalidades do invisível. Ela se interessa pelo modo como a memória interpreta e organiza o presente, pelas imagens que se inscrevem na voz de quem narra um mito, pelas formas etéreas dos sonhos, dos espíritos e de uma realidade convocada pelos ritos. Esse gesto assume uma dimensão política quando enfrenta as representações deformadas pelo preconceito ou quando devolve contorno aos corpos invisibilizados pelos discursos de poder. Mas essas imagens nunca estão totalmente reveladas. Elas permanecem

sensíveis tanto às vozes que ainda ecoam da ancestralidade Yanomami quanto às transformações assimiladas por essa cultura. E, assim, seguem demarcando o território de um povo que permanece sob o risco de desaparecer.

É crítico de fotografia e pesquisador do campo das imagens. Formado em jornalismo pela Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP), é mestre em multimeios pelo Instituto de Artes da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (IA/Unicamp), doutor em artes pela Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo (ECA/USP) e pós-doutor em cinema pelo IA/Unicamp. Leciona nos cursos de comunicação e artes da Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado (Faap) e é autor do livro de contos Diante da sombra (Confraria do Vento, 2018). Foi editor do portal Icônica e é colunista do site da revista Zum, do Instituto Moreira Salles (IMS).

1. Referências sobre a atuação de Claudia Andujar e George Love no Masp foram tomadas da dissertação de mestrado de Thais Lopes Camargo, “Museu de arte, fotografia e arquivo: a atuação de George Love e Claudia Andujar no Masp (1971-1976)”, apresentada no Programa de Pós-Graduação Interunidades em Estética e História da Arte, da Universidade de São Paulo (USP), em 2023.

2. ANDUJAR, C. [Entrevista cedida a] Thyago Nogueira. In: NOGUEIRA, Thyago (org.). Claudia Andujar: no lugar do outro. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2015. p. 243.

3. Ibid., p. 245.

4. O termo “napepe” quer dizer “não Yanomami”.

5. Fragmento de “O fim do mundo”, em: ANDUJAR, Claudia. Mitopoemas Yãnomam. São Paulo: Olivetti do Brasil, 1978.

6. LIMULJA, Hanna. O desejo dos outros: uma etnografia dos sonhos Yanomami. 2019. Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia Social) – Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2019. p. 89.

7. Marcados para viver, marcados para morrer é o título dado a uma montagem desse trabalho na Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery, em Londres, em 2005.

Maloca rodeada de folhas de batata-doce, 1974-1976 série A casa impressão com pigmento mineral sobre papel Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta 315 g

Coleção Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (MAM/SP)

Autores: Claudia Andujar e

George Love Design: Wesley

Duke Lee Editor: Regastein

Rocha Editora: Práxis

Este livro, seminal para a história da fotografia, é o ápice da parceria criativa entre Claudia Andujar e George Love. A publicação veio à luz em um momento em que artistas, antropólogos e indigenistas, socialmente organizados, se manifestavam contra o evidente genocídio dos povos indígenas na Amazônia. A tragédia era comandada de forma drástica pelo então governo militar, que estava explorando a região, com a abertura de estradas que rasgavam a Amazônia visando ao acesso às reservas de minério e à extração de madeira.

A edição desta sequência de cerca de 150 imagens é um marco da estratégia narrativa que amalgama objetividade e subjetividade. A qualidade expressiva das fotografias alia-se ao uso de imagens espelhadas, às outras que induzem ao movimento. Há ainda pontas de cromos com luzes erráticas e o manuseio de filmes infravermelhos que mostram um viés poético que contrasta com a forma como o governo também utilizava esse recurso fotográfico para localizar jazidas de minérios.

As imagens aéreas realizadas por George –ele tinha asma e conseguia permanecer poucos períodos no solo úmido amazônico – criam uma visão caleidoscópica de luzes, cores e reflexos. São visões paradisíacas, lisérgicas. Ao pousarmos desse sobrevoo na floresta, somos levados por Claudia ao universo de completa harmonia entre os Yanomami e a natureza.

O livro, feito para ser um manifesto, nos conduz à sequência final, quando Claudia denuncia o “malencontro” dos povos indígenas com o homem branco, que fez a doença e a miséria se alastrarem pelas aldeias. Referência hoje e sempre, Amazônia é um raro projeto em que a imbricação entre fotografia e cinema cria um êxtase visual.

A obra foi censurada por ter o prefácio escrito pelo poeta Thiago de Mello, considerado subversivo pelo regime. Em uma passagem do texto, que não pôde ser impresso na obra, Mello diz: “A verdade é que no céu dos índios, apodrecido pelo furor branco, já se apagam as últimas estrelas”. A editora Práxis foi fechada pelo governo militar logo após a publicação da obra.

Meu trabalho ainda não encontrou sua forma definitiva, que na verdade creio que não existe. Como os mitos, se adapta, incorpora novas imagens e toma novas formas, passa pela transcodificação [das imagens] para se atualizar, numa bricolagem virtual infinita. ¹

Claudia Andujar

Realidade, out. 1971

revista

Editora Abril

A maleabilidade com que Claudia Andujar compõe seus ensaios visuais nos coloca diante de temporalidades sobrepostas, rememora passados ainda presentes enquanto busca por futuros possíveis. A artista mobiliza recursos poéticos, como múltiplas camadas, longas exposições e bricolagens, que, conforme ela mesma descreve, atualizam os significados das imagens a cada nova série configurada. Ao mesmo tempo, trazem à visualidade algo captado por outros sentidos. Como nos diz Ailton Krenak, “a câmera não é neutra, se o olho que está por trás dela enxerga de maneira profunda, a imagem também vai refletir essa alma profunda”.2 Ao nos aproximarmos da trajetória de Claudia, percebemos que ela fez de suas dores e seus sonhos a força motriz para o cultivo de relações de alteridade que transformaram sua vida e sua arte.3

A prática fotográfica de Andujar é fruto indissociável de sua experiência de vida em território brasileiro, onde aportou ainda em 1955. Em suas viagens por estas terras, ela aprimorou o domínio da câmera, da linguagem técnica da fotografia, à medida que se embrenhava no convívio com seus novos conterrâneos, originários ou não.4 É possível que das fronteiras (geográficas, culturais, subjetivas, artísticas, políticas) atravessadas por ela antes e durante sua vivência no Brasil tenha emergido o sentido profundo com o qual vê o(s) mundo(s) e seus habitantes, visíveis e invisíveis. O mergulho na cosmologia Yanomami potencializou a jornada de Claudia à procura de possibilidades de reencantamento do mundo e da sua própria existência por meio da arte, gerando imagens que vislumbram uma dimensão intangível.

O encontro da artista com os Yanomami coincide com suas experimentações com as novas mídias e tecnologias surgidas no início dos anos 1970, assim como com os anos mais duros da última ditadura civil-militar brasileira (1964-1985). Esse foi um período de transição e de muitos desafios na trajetória de Andujar. Nesse sentido, a parceria artística com o fotógrafo George Love,5 com quem teve um relacionamento amoroso, parecia dar pistas das poéticas de criação adotadas por Claudia e

revelar suas práticas mais experimentais, que têm raízes em sua passagem tanto pelo fotojornalismo quanto por museus de arte da cidade de São Paulo.

Em meados da década de 1960, Andujar já havia publicado em revistas internacionais, como Time, Life e Jubilee, e suas fotografias constavam em acervos de instituições como o Museu de Arte Moderna de Nova York (MoMA) e o George Eastman House. No entanto, segundo ela, “não foi fácil ser reconhecida como fotógrafa no Brasil”.6 As fotos de Claudia tinham pouca ressonância com o fotojornalismo praticado no país na época, via de regra sensacionalista, principalmente quando se tratava de povos originários.7 Tampouco os fotógrafos gozavam do status de artistas ou a fotografia havia sido assimilada às coleções de arte de museus brasileiros. Esse fato a motivou a divulgar seu trabalho em Nova York, cidade onde se refugiara com o término da Segunda Guerra Mundial e na qual tivera os primeiros contatos com o mundo da arte. Em uma dessas viagens, conheceu George Love, tendo como propulsores os movimentos sociais por direitos civis, os ideais de contracultura e o entusiasmo pela investigação da linguagem fotográfica.

Nos anos 1960, George esteve envolvido na organização de mostras na Heliographers Gallery, mantida pela Association of Heliographers,8 da qual tanto ele quanto Claudia foram membros.

Além disso, ambos compartilhavam o fato de terem sido atravessados por eventos traumáticos ainda na infância: ela pela ascensão do nazismo no Leste Europeu, ele pelo regime de apartheid em sua cidade natal (Charlotte, Estados Unidos).

Claudia e George se casaram em 1968. Love havia chegado ao Brasil em 1966 e passado a fazer parte da equipe de fotógrafos da Editora Abril, para a qual Claudia já trabalhava como freelancer. Publicaram em diversas revistas do grupo, em particular na Realidade, participando da escolha de pautas e da edição final das matérias. Andujar afirma que a Realidade marcou um momento de valorização da

profissão de fotógrafo no país.9 As pautas que ela cobria demonstravam seu forte interesse por grupos socialmente marginalizados da população brasileira, sem retratá-los de maneira estereotipada.

A edição especial da revista sobre a Amazônia, lançada em outubro de 1971, veiculou – inclusive na capa – as imagens nascidas do encontro de Claudia com os Yanomami da região de Maturacá, no Amazonas. A matéria com as fotos de Andujar traçava um histórico das lutas de resistência indígena à invasão de seu território e denunciava o genocídio da população originária ao longo do tempo. Abordagem no mínimo incomum para a imprensa da época. Apesar de o tom geral da revista reverberar os discursos desenvolvimentistas defendidos pela ditadura, tal reportagem motivou a censura da publicação e a perseguição política da equipe. Após essa edição, Claudia abandonou o fotojornalismo e concentrou-se na criação artística em seus próprios projetos.

Como consequência, ela se engajou na promoção da fotografia em espaços institucionais de arte num momento de diluição das tradicionais fronteiras entre as linguagens artísticas, até então mantidas com relativa estabilidade. Em companhia de George Love e de fotógrafos como Maureen Bisilliat, Cristiano Mascaro e Boris Kossoy, Andujar participou da organização de exposições e de atividades que atualizavam os debates acerca da introdução da fotografia nos acervos de museus de arte, bem como sobre os deslocamentos provocados pelo uso da linguagem fotográfica em práticas de artistas vindos principalmente da arte conceitual e da arte pop

Antes de se envolver mais intensamente com o Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), Claudia Andujar expôs obras que já investigavam a expansão da fotografia em outros museus da capital paulista. Entre esses trabalhos estão duas composições, Sem título (1970) e Inês (1971), nas quais se utilizou de acrílico sobre fotografia, segundo ela, para potencializar a emoção sugerida pela imagem, e que ainda traziam as bordas dos negativos, revelando a própria linguagem fotográfica. Já em Sem título (1970), em autoria compartilhada com Love, a

Sem título, 1970

acrílico, fotografia analógica em preto e branco e ampliação sobre papel resinado colado sobre madeira

Acervo Pinacoteca de São Paulo

Inês, 1971 fotografia sobre papel e acrílico sobre madeira

Claudia Andujar e George Love

Sem título, 1970 fotografia em preto e branco sobre papel sobre madeira

111,5 x 111,5 x 5 cm Aquisição MAC/USP

Páginas da Revista de Fotografia, ano 1, n. 1, jun. 1971

Acervo Centro de Pesquisa do Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp)

Claudia Andujar e George Love O homem da hileia, 1973 cartaz

Acervo Centro de Pesquisa do Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp)

engrenagem que movimenta a roda do trem salta do quadro, rompendo com os limites da moldura. É de se pontuar, ainda, a relevante participação de Claudia e George no Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo (MAC/USP). Ambos colaboraram como artistas, curadores e membros do comitê de fotografia organizado pela instituição sob direção de Walter Zanini.10

Entre 1971 e 1976, Andujar e Love atuaram conjuntamente em exposições e eventos do Masp, cujo diretor-fundador, Pietro Maria Bardi,11 nutria um “interesse antigo por fotografia”.12 Além de terem organizado um laboratório e um departamento de fotografia, com o intuito de formar uma coleção para o museu, eles contribuíram como artistas em mostras nas quais propuseram novos meios de exibição de fotografias, com seus “audiovisuais”.13 “Audio-visual”, na grafia da época, foi como ficou conhecida a montagem específica de projetores de slides em carretel sincronizados com sons mixados em fitas cassete, podendo ter mais de um projetor emitindo imagens ao mesmo tempo. Algumas dessas montagens contavam com tecnologias como o controle de fusão (dissolve control), que mesclava as fotografias projetadas fazendo a transição de uma para a outra. Claudia e George exibiram “audio-visuais” no Masp em ao menos quatro oportunidades. Destacarei dois deles por terem ressonância direta com obras que agora se apresentam na exposição Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão (2024).

Em julho de 1971, Claudia projetou A Sônia no pequeno auditório do museu, ao som de uma gravação ao vivo de “I had a dream”, de John Sebastian, no festival Woodstock de 1969. Sônia, mulher negra vinda da Bahia para realizar o sonho de ser modelo em São Paulo, encontrava-se desiludida por não atender aos padrões publicitários vigentes na época. Segundo a artista, a música inspirou as poses oníricas da modelo,14 que parecia voltar a sonhar. O ensaio já nasce audiovisual. Claudia trabalhou os cromos fazendo cortes,

invertendo as polaridades e refotografando-os com a ajuda de equipamentos que permitiam a utilização de filtros de diferentes cores, a manipulação da exposição e a sobreposição de camadas.15 É possível constatar, em A Sônia, a radicalidade das experimentações de Claudia na edição e na composição das imagens, recortando, manuseando e intervindo nos filmes, além da aplicação intensa de cores saturadas. A série sugere uma espécie de ruptura com uma estética puramente documentária, que já vinha sendo investigada por ela e por Love em meios impressos. As imagens foram publicadas na primeira edição da Revista de Fotografia, da qual Love era editor, no mesmo mês da exposição.16

Para a projeção, a artista chegou a uma sequência de 90 slides, que transicionavam conforme o ritmo e o significado da música. As imagens fixas em diapositivo eram multiplicadas por pequenos espelhos e pedaços de acrílico colocados estrategicamente em frente às lentes dos projetores e movimentadas com a ajuda de ventiladores. O formato “audio-visual” devolve o movimento às imagens estáticas, e a relação com a trilha sonora potencializa os sentidos da música, cuja letra fala de um sonho lindo e, no entanto, pouco compreendido. O sentido de transcodificação mencionado por Andujar no início deste texto fica ainda mais evidente nesse cenário. É notável a recorrência de obras suas, nesse período, com imagens de mulheres, sugerindo ao mesmo tempo a investigação do universo feminino e a busca de si, como se procurasse meios de atuação do próprio corpo no mundo.17 Os sonhos de Claudia parecem apontar os caminhos por vir.

Naquele mesmo ano, a artista recebeu a primeira de duas bolsas de pesquisa concedidas pela Fundação Guggenheim. Em dezembro de 1971, ela chegou em companhia de George à bacia do Rio Catrimani, em Roraima, onde se concentra a maior parte de seu trabalho com os Yanomami. Foi quando conheceu o missionário Carlo Zacquini, que dali em diante se tornaria seu companheiro na luta em defesa dos povos indígenas até hoje. A partir desse momento, Claudia passou a dividir sua vida entre São Paulo e a Amazônia.

SONHO VERDE-AZULADO

No final de 1972, foi inaugurada no Masp a exposição Hileia amazônica, na qual Love e Andujar exibiram O homem da hileia. O “audio-visual” apresentava pela primeira vez imagens dos Yanomami em um espaço institucional dedicado à arte, feitas nas imersões iniciais de Andujar na região do Rio Catrimani, muitas vezes acompanhada de Love. Em contraponto à narrativa geral da época, que previa a integração dos povos indígenas à sociedade branca dominante, a obra de Claudia e George retratava pessoas vivendo saudáveis, em harmonia com a floresta e seus seres, humanos e não humanos, visíveis ou invisíveis. Uma reportagem sobre a exposição trazia o subtítulo “Claudia vê os índios como seres, humanos”,18 deixando escapar a visão racista disseminada na sociedade.

O texto curatorial sobre O homem da hileia indica que “a sequência de cromos resultou da refotografia de ampliações em preto e branco com filme colorido”,19 evidenciando a técnica de Andujar para a adição de luzes e camadas coloridas em imagens em preto e branco. O áudio era de um milenar instrumento musical japonês chamado koto, tocado sobretudo por mulheres, mixado com sons da floresta e cantos captados na aldeia. A montagem contou com dois projetores com controle de fusão e espelhos que multiplicavam cada imagem em sete outras diferentes, projetadas em sete telas instaladas no espaço expositivo. Percebemos também uma noção de performatividade na proposta, na medida em que os artistas previam a movimentação do corpo para a ativação da obra. Uma versão modificada do “audio-visual” O homem da hileia foi incluída na representação brasileira na feira Brasil export de Bruxelas (1973), na Bélgica, organizada por Pietro Maria Bardi. A data do cartaz que anunciava o trabalho corresponde à da exibição internacional. Além disso, Andujar exibia a montagem original em seus cursos no laboratório de fotografia do Masp. Os slides de O homem da hileia deram origem, posteriormente, à série Sonho verde-azulado (2012).20

A intenção de organizar um livro sobre os Yanomami existia desde essa exposição, mas o desejo se realizaria apenas no final da década.

Nesse meio-tempo, Claudia passou a circular suas fotografias cada vez mais vinculadas à luta indígena por seus territórios originários e contra o genocídio de Estado, nos anos de maior repressão da ditadura militar. Permaneceu longos períodos na floresta, voltando para a cidade para revelar seus filmes, que poderiam se deteriorar com a intensa umidade, e para estudar técnicas para fotografar em ambientes de baixa luminosidade.

As montagens criadas por Andujar e Love na década de 1970 acionavam hibridações entre fotografia, cinema, artes visuais e novas tecnologias, num espaço que se compunha entre imagens e entre mídias.21 Estavam em plena experimentação de práticas artísticas transdisciplinares. Artistas como Iole de Freitas, Lygia Pape, Antonio Dias, Julio Plaza, Regina Silveira, Carmela Gross, Cildo Meireles, Frederico de Morais e Anna Bella Geiger desenvolveram pesquisas com “audio-visuais”. Os chamados “quasi-cinema”, de Hélio Oiticica, como as Cosmococas, são dessa mesma época. Entre os artistas que se dedicaram mais intensamente à linguagem fotográfica e experimentaram práticas entre mídias, destacam-se Miguel Rio Branco e Arthur Omar. A Expoprojeção73, organizada por Aracy Amaral, mostrou obras de muitos desses artistas ainda na época.22 As práticas artísticas dos anos 1960 e 1970, tais como a videoarte, o cinema experimental e os filmes de artista no contexto de expansão do campo das artes, podem ser consideradas como mídias de passagem, estágios iniciais das poéticas que hoje conhecemos como instalação e performance 23 No Brasil, em resposta ao contexto repressivo dos anos mais duros do regime ditatorial, potencializou-se a radicalização dessas experiências artísticas.

No Masp, Andujar também deu aulas de fotografia. Entre 1973 e 1975, nos períodos em que não estava na floresta, ela organizou cursos pelo laboratório de fotografia do museu, nos quais ensinava técnicas que aplicava em seus trabalhos e compartilhava

referências visuais de outros fotógrafos. Entre eles estavam Henri Cartier-Bresson, W. Eugene Smith, Duane Michals, Robert Frank, Syl Labrot, Linda Parry e Larry Clark, evidenciando as diversas tendências fotográficas que lhe inspiravam. Claudia cuidava da parte conceitual e teórica das aulas, enquanto outra pessoa (Hugo Gama, George Love, Roger Bester ou Irene Goralski) orientava na prática do laboratório. Alguns cursos foram ministrados em parceria com Love, outros não. Eles se separaram oficialmente em 1974 e continuaram a colaborar até a publicação do livro Amazônia, em 1978. É possível, ainda, que muitas das imagens de Andujar sobre a cidade de São Paulo tenham sido captadas em saídas fotográficas com seus alunos, atividade prevista em alguns de seus cursos. A ideia de documentar a cidade e seus problemas talvez tenha surgido nessas caminhadas.

Além disso, Claudia e George colocaram na agenda do laboratório do Masp exposições com a produção fotográfica dos alunos e seminários e eventos sobre fotografia que discutiam sua intersecção com diversas áreas do conhecimento, incluindo as artes. Dos desdobramentos dessas atividades surgiu o departamento de fotografia do museu,24 gerido por Andujar desde sua fundação, em 1975, até o ano seguinte. No Arquivo Histórico do Masp existem correspondências tanto dela quanto de Pietro Maria Bardi solicitando ou agradecendo doações para a formação de um acervo de fotografia no museu. Tais obras, no entanto, não compuseram oficialmente a coleção de arte do museu, que registraria a entrada de fotografias apenas em 1989 e, mais sistematicamente, com a Coleção Pirelli/Masp de fotografia, em 1991. Alguns impasses institucionais e divergências conceituais entre Bardi e Andujar na condução de exposições, paralelamente à urgência em dar respostas à situação de perigo atravessada nas terras Yanomami, fizeram com que Claudia optasse por se desvincular do museu em favor da floresta.

Naquela altura, a construção da Rodovia Perimetral Norte, braço da Transamazônica, já havia atingido o território Yanomami, e suas avassaladoras consequências – desmatamento,

violência, doenças e mortes – foram testemunhadas por Claudia. Em 1976, em companhia de Carlo Zacquini, ela embarcou em seu fusca preto –chamado de Watupari pelos indígenas –, carregado de equipamentos fotográficos, papéis e canetas hidrográficas, com direção a Roraima. Tais materiais seriam utilizados na realização do projeto de desenhos e interpretação da percepção de mundo Yanomami. Viabilizado por bolsa concedida pela Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (Fapesp), o projeto resultou na criação de Mitopoemas Yanomãm, livro de desenhos, de poemas e de fotografia a um só tempo. Os desenhos dos Yanomami são acompanhados da narrativa poética sobre a sua visão expandida do universo, junto com algumas fotografias de Andujar impressas em transparências, revelando mais uma vez o diálogo entre diversas formas expressivas. Essa viagem simboliza o salto definitivo de Andujar em direção ao engajamento na causa Yanomami. A travessia foi registrada por ela utilizando a janela do fusca como frame para as imagens, que apenas em 2013 compuseram a série O voo de Watupari. 25 O mergulho na floresta e a compreensão da cosmovisão indígena, somados à destreza técnica e à sensibilidade artística, foram determinantes para Andujar conseguir traduzir fotograficamente um vislumbre do mundo Yanomami. Ainda em 1974, ela escreveu em suas anotações: “Constato que me sinto à vontade neste mundo Yanomami. Não me sinto mais estranha. Este mundo ajuda a me compreender e a aceitar o outro mundo em que me criei. Os dois mundos estão se juntando, num grande abraço. É, para mim, um mundo só. Não sinto saudades”.26

Os três livros publicados por Andujar em 1978 –Mitopoemas Yanomãm; Yanomami – frente ao eterno; e Amazônia – são frutos desses anos de intenso convívio com os Yanomami e uma resposta poética ao contínuo agravamento das invasões às suas terras.

A confluência entre Claudia e George desaguou na criação do livro Amazônia. 27 Nessa obra, a dupla materializou as poéticas que mobilizava nos “audio-visuais”, tornando-se uma das poucas em autoria compartilhada que chegaram aos nossos dias. O ritmo das imagens, quase cinematográfico,

é marcado por alterações cromáticas, longas e múltiplas exposições, além de convocar uma linguagem autorreferencial com a introdução de bordas de negativos, pontas de filmes e sobras de processos fotográficos. Censurado pela ditadura militar, o livro foi publicado em baixa tiragem, sem o texto original do poeta amazonense Thiago de Mello, e distribuído de forma clandestina, permanecendo durante muitos anos numa quase obscuridade. Povos indígenas eram assunto proibido no debate público daqueles anos.28 As partes destinadas ao poema foram deixadas em branco, num gesto de denúncia. A valorização tardia de Amazônia veio no bojo do pleno reconhecimento artístico recebido por Andujar nos últimos 25 anos, quando ela passou a compor artisticamente a partir de seu arquivo, revelando grande parte da produção que não pôde circular em razão da censura e da perseguição política sofridas durante o período ditatorial.

Em 197 7, ela foi impedida por agentes do governo de permanecer na terra indígena – na mesma época em que conheceu Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, que se tornaria seu companheiro de luta fundamental. Um ano depois, fundou, com Carlo Zacquini e Bruce Albert, a Comissão pela Criação do Parque Yanomami (CCPY), com o objetivo de lutar pela demarcação contínua do território Yanomami por vias jurídicas institucionais.

Durante a década de 1980, ela sobrepôs a luta política à divulgação de sua produção artística e consolidou a parceria com Kopenawa. Voltou a expor no Masp apenas em 1989, com o “audio-visual” Genocídio do Yanomami, morte do Brasil, criado para a exposição de mesmo nome organizada pela CCPY. Suas fotografias já não abordavam apenas o mundo Yanomami em harmonia, começavam também a apresentar as graves consequências do contato forçado dos indígenas com os brancos. Toda a mostra foi realizada por ativistas e integrantes do movimento indígena, entre eles Ailton Krenak e Davi Kopenawa. A exposição consistiu em uma importante plataforma para pressionar o governo, em processo de redemocratização, quanto à urgência da demarcação contínua e da homologação da Terra Indígena Yanomami, que aconteceria em 1992. As

invasões diminuíram, mas nunca cessaram. Voltaram a se agravar durante a presidência de Jair Bolsonaro, culminando no cenário dramático que veio a público em janeiro de 2023 e que ainda permanece.

O livro Yanomami, de Claudia Andujar, lançado em 1998, é dedicado a George Love, possivelmente em homenagem ao antigo companheiro, falecido três anos antes. A dedicatória foi uma das pistas que apontavam para a contaminação recíproca entre suas pesquisas artísticas, reverberação que é muito delicadamente confirmada por Andujar: “Aprendi muita coisa com George. Mais esse lado técnico e a busca por novas linguagens na fotografia. Mas nunca abandonei meu interesse humano”,29 disse ela. Após revisitarmos parte significativa de sua trajetória, constatamos que Claudia trilhou seus caminhos pautada pelo desejo (e pelo sonho) do encontro sensível com o mundo, consigo mesma e com outros seres viventes através da arte. Já quanto à ideia de que haveria uma única parceria determinante em sua busca poética, o que de fato se apresenta é o oposto. Vemos surgir sua autonomia em uma constelação de conexões e parcerias de diferentes naturezas que se atualizam a cada nova transcodificação das imagens fotográficas. Seu trabalho, fruto da aliança político-afetiva com os Yanomami, não responde a um regime de autoria convencional e individualizante, é uma produção coletiva. A artista tornou-se, assim, um ser coletivo, que uniu poética e política em um passado recente que até hoje nos assombra.

Ainda em Yanomami (1998), ela nos alerta: “Sem esse passado e a sua história, a bricolagem cairia no vazio”,30 referindo-se aos seus métodos de composição e às memórias suscitadas pelo contexto histórico de produção das fotos. Cabe a nós compreender essa história passada ainda tão presente e nos aliar a quem protege a floresta e sabe segurar o céu. Talvez assim possamos todos, indígenas e não indígenas, ter a chance de sonhar com outros futuros possíveis além do que já se anuncia.

É assistente de curadoria da exposição Claudia Andujar: cosmovisão, pesquisadora, arte-educadora e documentalista em constante formação. Mestre em artes pelo Programa Interunidades em Estética e História da Arte da Universidade de São Paulo, com a dissertação “Museu de arte, fotografia e arquivo – a atuação de Claudia Andujar e George Love no Masp (1971-1976)”, atualmente investiga interações entre fotografia e práticas artísticas transdisciplinares; poéticas da memória e direitos humanos; e história das exposições e formação de arquivos e acervos de museus de arte da cidade de São Paulo.

1. ANDUJAR, Claudia. Os Yanomamis em minha vida. In: ANDUJAR, Claudia. Yanomami. São Paulo: DBA Artes Gráficas, 1998.

2. INSTITUTO MOREIRA SALLES. Claudia Andujar por Ailton Krenak e Renata Tupinambá – conversa na galeria. YouTube, 9 set. 2019. Disponível em: https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=bAJi-J-BCn8&t=1s&ab_ channel=imorerirasalles. Acesso em: 2 maio 2024.

3. A maior parte da pesquisa que embasa este texto foi realizada para a dissertação de mestrado defendida pela autora em março de 2023. Ver: CAMARGO, Thais Lopes. Museu de arte, fotografia, arquivo: a atuação de Claudia Andujar e George Love no Masp (1971-1976). 2023. Dissertação (Mestrado em Estética e História da Arte) – Programa Interunidades em Estética e História da Arte, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2023. Disponível em: https://www. teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/93/93131/ tde-22052023-112432/pt-br.php. Acesso em: 2 maio 2024.

4. São desse período as séries sobre os indígenas Karajá, autodenominados Iny (1958-ca. 1960), abordando o dia a dia de famílias brasileiras de diferentes regiões, origens e classes sociais (1962-1964); e sobre as atribuições das mulheres do povo Bororo, autodenominado Boe (1964-1965). 5. George Leary Love (1937-1995). Nascido em Charlotte, na Carolina do Norte, Estados Unidos, onde vigorava o regime segregacionista do apartheid , sua família vinha de uma longa tradição de luta por equidade de direitos raciais. Trabalhou para a United States International Cooperation Administration na

Ásia, no Oriente Médio e na Europa. Em 1961, mudou-se para Nova York e estudou matemática aplicada e filosofia na New School for Social Research. Iniciou-se na fotografia de forma autodidata e desenvolveu pesquisas com a Association of Heliographers. Esteve envolvido também com o movimento negro por direitos civis como fotógrafo de campo do Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), que realizava protestos conhecidos como sit-ins . A partir de 1966, no Brasil, trabalhou como fotojornalista em várias publicações da Editora Abril. Foi editor de fotografia de revistas especializadas, como a Novidades Fotoptica e a Revista de Fotografia . Publicou os livros de fotografia Amazônia (1978, em parceria com Claudia Andujar), São Paulo: anotações (1982) e Alma e luz: sobre a Bacia Amazônica (1995, publicado poucos meses após seu falecimento).

6. BONI, Paulo César. Entrevista: Claudia Andujar. Discursos fotográficos, Londrina, v. 6, n. 9, p. 255, jul.-dez. 2010.

7. COSTA, Helouise. Fotorreportagem como projeto etnocida: o caso da índia Diacuí na revista O Cruzeiro. In: CURY, Marília Xavier (org.). Direitos indígenas no museu: novos procedimentos para uma nova política, a gestão de acervos em discussão. São Paulo: Acam Portinari; Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da USP, 2016.

8. Fundada em 1963 por Walter Chappell, a Association of Heliographers era formada por fotógrafos como Paul Caponigro, William Clift e Carl Chiarenza, interessados em novos modos de produção e composição de fotografias.

9. NOGUEIRA, Thyago (org.). Claudia

Andujar: no lugar do outro. São Paulo: Instituto Moreira Salles, 2015. p. 243. (Catálogo de exposição).

10. As duas últimas obras citadas pertencem ao acervo do museu e foram doadas por eles na época. Ver: COSTA, Helouise. Da fotografia como arte à arte como fotografia – Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo nos anos 1970. Anais do Museu Paulista, São Paulo, v. 16, n. 2, p. 131-173, 2008.

11. Pietro Maria Bardi (1900-1999) foi diretor-fundador do Masp, à frente do qual permaneceu entre 1947 e 1989. Ele e Claudia se conheceram em meados dos anos 1950, ainda no Masp da Rua Sete de Abril. Em 1958, Bardi escreveu para a Revista Habitat um artigo sobre o trabalho de Andujar, que na época migrava da pintura para a fotografia. Esse é um dos primeiros textos de sua fortuna crítica.

12. COSTA, op. cit., p. 163.

13. Na França e na Espanha, principalmente, essas montagens ficaram conhecidas como diaporama; e, em países de línguas anglo-saxônicas, como slideshow.

14. ANDUJAR, Claudia. Ensaio: Claudia Andujar. Revista de Fotografia, São Paulo, n. 1, p. 33, jun. 1971.

15. Segundo ela, utilizava um aparelho conhecido como Repronar. Ver: NOGUEIRA, op. cit., p. 168.

16. A Sônia permaneceu praticamente fora de circulação por mais de 40 anos (até 2015) e é remontada em formato audiovisual pela primeira vez, desde 1971, nesta exposição.

17. CAMARGO, op. cit., p. 117-127.

18. Recorte de jornal. Arquivo Histórico do Masp. Pasta da exposição Amazônia B, 1972.

19. O homem da hileia [Texto curatorial].

Arquivo Histórico do Masp. Pasta exposição Amazônia B, 1972.

20. NOGUEIRA, Thyago (org.). Claudia Andujar – a luta Yanomami. São Paulo: IMS, 2018. p. 173. (Catálogo de exposição).

21. BELLOUR, Raymond. Entre imagens: foto, cinema, vídeo. São Paulo: Papirus, 1997.

22. AMARAL, Aracy. Expoprojeção73 São Paulo: Centro de Artes Novo Mundo, 1973. (Catálogo de exposição).

23. DUBOIS, Philippe. Um “efeito cinema” na arte contemporânea. In: COSTA, Luiz Cláudio da. Dispositivos de registro na arte contemporânea. Rio de Janeiro: ContraCapa Livraria; Faperj, 2009. p. 179-216.

24. CAMARGO, op. cit., p. 145-165.

25. Watupari, em língua Yanomami, significa “ser urubu”. O carro foi apelidado assim que Claudia chegou com ele à aldeia, por causa de sua cor preta e das formas arredondadas.

A exposição O voo de Watupari, com imagens da viagem feitas através da janela do fusca, foi apresentada pela primeira vez em 2013, na Galeria Vermelho, em São Paulo.

26. ANDUJAR apud NOGUEIRA, op. cit., p. 193.

27. SILVA, Vítor Marcelino. A construção coletiva de “Amazônia”: fotografia e política no livro de Claudia Andujar e George Love. 2022. Tese (Doutorado em História da Arte) – Programa Interunidades em Estética e História da Arte, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2022.

28. MAUAD, Ana Maria. Imagens possíveis – fotografia e memória em Claudia Andujar. Revista Eco-Pós, v. 15, n. 1, p. 136, 2012.

29. NOGUEIRA, op. cit., p. 242. 30. ANDUJAR, op. cit., s/n.

Em 1970, Sônia, uma mulher negra e baiana, sonhava em se estabelecer como modelo em São Paulo. Para tanto, necessitava de boas fotografias para levar às agências de publicidade. Sem recursos, porém, ela não conseguia que algum profissional a fotografasse. Claudia Andujar a socorreu, propondo um acordo: Sônia teria as imagens de que necessitava, e a artista utilizaria parte delas para um projeto pessoal.

Após uma sessão fotográfica com dez rolos de slides, totalizando 360 imagens, Claudia selecionou cerca de 90 delas e submeteu-as a uma série de interferências: realizou cortes abruptos, utilizou filtros coloridos e, ainda insatisfeita, refotografou os cromos com o Repronar –equipamento que permitia reproduzir os cromos adicionando filtros coloridos, manipulando a exposição e justapondo imagens.

Em 1971, Claudia expôs esse ensaio no Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp), no formato de audiovisual, utilizando projetores e trilha sonora. O projetor de slides, com o sistema de carrossel, havia sido patenteado pela Kodak em 1965 e tornou-se um dispositivo que auxiliava as criações artísticas daqueles que, como Claudia e George Love, queriam tirar a fotografia do seu modo de exibição habitual para criar atmosferas e imersões sensoriais.

Nesse ambiente de busca de novos horizontes para a fotografia, ela realizou algumas exposições no Masp utilizando o audiovisual no lugar de cópias em papel. Radicalizando esse gesto, em sintonia com o espírito libertário e lisérgico da época, em algumas montagens as imagens eram filtradas por plásticos colocados no meio da sala expositiva e por espelhos que as refletiam como num caleidoscópio. Com o recurso sonoro, essas mostras se tornavam ambientes imersivos, abriam novas frentes para a percepção e tiravam o espectador de uma posição passiva, colocando seu corpo em relação ativa com a obra. São dessa época também as experiências intituladas “quasi-cinema” do artista Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980), como a icônica Cosmococas, feita em parceria com o cineasta Neville D’Almeida. Segundo Oiticica, esses ambientes se “contrapõem ao objeto de arte como mero produto de consumo do mundo

capitalista. O suprassensorial levaria o indivíduo à descoberta do seu centro criativo interior, da sua espontaneidade expressiva adormecida, condicionada ao cotidiano”.1

O artista Leandro Lima, parceiro de Claudia em outros projetos, foi convidado especialmente para recriar pela primeira vez, 53 anos depois, a projeção de A Sônia a partir de pesquisas da curadoria que restituem as experimentações da fotógrafa nos anos 1970.

Na página seguinte, reprodução de publicação da Revista de Fotografia de junho de 1971, pertencente ao Acervo Centro de Pesquisa do Museu de Arte de São Paulo (Masp). Nas demais páginas, imagens da série

A Sônia, 1970

NOTA

1. OITICICA, Hélio. Aspiro ao grande labirinto. Seleção de textos: Luciano Figueiredo, Lygia Pape e Waly Salomão. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1986. p. 73.

Claudia Andujar A Sônia, 2024 videoinstalação: Leandro Lima

Carlo Zacquini

em diálogo com Mariana Lacerda

Eu estava chegando de umas férias na Itália, e então acertamos de subir juntos de São Paulo para cá [Boa Vista, Roraima]. Lembro que Claudia queria ir sem data para voltar e, assim, preferiu levar o seu carro. Ela organizou e combinou as coisas e preparou os mapas. Nós nos encontramos em São Paulo e saímos. Ela cuidou para que fizessem uma boa revisão no fusca, para ter certa garantia. Ela colocou, mas talvez já tivesse, um suporte para acomodar a bagagem em cima do capô. Saímos pela Avenida Paulista, estava chovendo, e seguimos rumo a Mato Grosso.

Eu lembro que fomos andando e, em certo momento, após termos parado para comer algum sanduíche ou coisa assim, já era noite e ouvimos um barulho. O bagageiro despencou no meio da estrada. Tentei ver se podia ajeitar, mas não teve jeito. Não havia oficina, estávamos numa estrada até asfaltada, porém tudo muito escuro. Não acho que eu tenha encontrado todas as peças para remontar. Fiz uns truques de mágica para tentar fazer caber tudo dentro do fusca. Aí ficou tudo socado. Em certo momento, achamos algum lugar para dormir e, um dia depois, estávamos na estrada de novo.

Até Boa Vista foram 13 dias. Nós não fazíamos paradas longas, foi uma coisa bastante puxada. Claudia fez poucas fotografias durante a viagem. Lembro apenas que ela fotografava de dentro do fusca. Tínhamos sempre um pouco de pressa em seguir viagem. Lembro-me bem dela fotografando num descampado, um tipo de cerrado.

Acho que uma das primeiras paradas foi num lugar onde tinha uns indígenas que faziam bolas de látex. Eram indígenas Paresí. Na época, eles faziam ainda umas bolas de resina, que tiravam de árvores, talvez fosse seringa. Eram bolas bonitas, dava para brincar.

Paramos em Campo Grande (MS). Não tivemos tempo de olhar muito. Depois, o asfalto acabou. Havia, em alguns lugares, máquinas do Exército, eu acho, não sei bem o que eram. E, em certo momento, a estrada era pura areia, com valas profundas provocadas pelos pneus dos caminhões. E, com o fusca, tivemos de ter muito cuidado para não ficar presos naquelas valas grandes. Fiquei

com medo de encalharmos naquelas valas e não podermos seguir.

Paramos em vários lugares para dormir. Em uma dessas vezes, estávamos em uma espécie de hotel ou motel, e havia lençóis velhos remendados. São lembranças esparsas. Víamos acampamentos em alguns lugares, que eram dos militares que estavam ali fazendo trabalhos. Mas não se via muita coisa nem muitas pessoas.

Em certo momento, nós nos encontramos com uns indígenas que andavam pela BR vestidos com trapos. Eles falavam algumas palavras em português, com dificuldade. Fiquei emocionado, tentei falar com eles, me saíram umas palavras em Yanomae e eles acharam engraçado. Acabamos tendo uma troca de informações e eles me explicaram que seu nome era Mamaindê. Paramos, conversamos com alguns deles. Pedi para saber onde eles moravam. Levaram-nos a uma pequena cobertura rudimentar, uma coisa que me parecia feita muito às pressas. Eu sei que achei muito interessante. Eles faziam colares lisos, que trocamos com alguns objetos. Comprei de uma mulher as pedras que ela usava para fazer as contas de tucum, ou talvez de outro fruto de palmeira. Eu vi pela primeira vez como eles faziam essas contas, eles foram muito atenciosos, bonitos. Mais tarde, encontramos alguém que nos explicou tratar-se de um subgrupo dos mais conhecidos Nambikwara. E fomos em frente. E então achamos um lugar chamado Espigão d’Oeste, em Rondônia. Sei que tinha uma vila nova, com não sei quantas casas feitas em série. Fomos lá, conversamos com alguém e descobrimos que, a mais ou menos 200 metros dessa vila, existiam indígenas que ainda eram bastante isolados, alguns ainda não tinham roupas. Não falavam português. Descobri que eram os Suruí.1 Eu fiquei chocado com aquilo, com o fato de eles estarem vivendo tão próximo de uma pequena cidade. Não tinha absolutamente ninguém controlando a entrada de pessoas na aldeia, e nós fomos de carro até certo ponto

e depois caminhamos até a maloca. Eu fiquei realmente impressionado, foi uma coisa que me deixou marcado: o descaso. Aquela vila era uma coisa claramente feita sob demanda do governo militar, ao lado de uma aldeia de indígenas ainda com pouquíssimo contato. Eu não lembro mais se fotografei ou se Claudia fotografou. Talvez não, porque ficamos muito tocados.

Seguimos e chegamos a Cuiabá (MT), onde dormimos. E depois fomos pela BR – talvez fosse a Cuiabá-Santarém, mas na verdade eu não lembro. Era uma rodovia com um asfalto que parecia novo. Depois, começaram a aparecer buracos fundos por todos os lados, dava a impressão de que tinham sido feitos por alguém com algum propósito particular que eu não conseguia entender. Todos eles eram quadrados ou retangulares, pareciam feitos com esquadro. Refletindo em seguida, cheguei à conclusão de que o terreno deveria ter cedido em muitos lugares porque o leito asfáltico não foi apoiado em uma base firme. Ficou claro para mim que a estrada não iria aguentar muito tempo. Bem depois, eu soube que essa estrada foi fechada. Acho que tinham colocado o asfalto em cima da lama. Até hoje me pergunto o que era aquilo.

Em algum momento, encontramos um homem arrastando uma cobra de uns 5 metros. Era uma surucucu, venenosíssima, que o homem tinha matado pouco antes trabalhando numa derrubada, com uma machadada na cabeça – ele levava consigo o machado nas costas. Pedi permissão a ele para extrair os dentes da surucucu. Ele deixou e até hoje os tenho guardados na Itália, na minha coleção de cultura material.2

Daquele jeito, acabamos chegando a Manaus (AM). A estrada de Manaus para Boa Vista já estava praticamente feita, mas ainda existiam intervenções ao longo dela. Não havia garantia de que a gente pudesse chegar aqui [Boa Vista] pela estrada. Se a gente fosse, podia ainda demorar meses, pois tinha muitas obras. A maior parte ainda era em terra batida. E, toda vez que vinha uma chuva, as obras paravam. Não dava para usar a estrada.

Daí, fui atrás de um conhecido que transportava mercadorias de Manaus para Boa

Vista pelo Rio Negro e pelo Rio Branco. Ele usava umas barcaças grandes e um motor de centro que amarrava a elas para empurrá-las rio acima. Ele tinha uma carga de milhares de sacos de cimento, sobre os quais havia estendido lonas para que não molhassem, naturalmente. O fusca acabou sendo colocado em cima das lonas, e nós embarcamos. Depois de umas horas de navegação, deu um temporal muito violento, com ventos, a coisa foi feia, porque a embarcação tinha pouco espaço e as ondas estavam altas. Se elas entrassem, com os sacos de cimento misturados com água, iríamos afundar com facilidade. Talvez nós pudéssemos nos salvar, mas a embarcação iria para o fundo, e o fusca também. O banzeiro da água ameaçava entrar nas barcaças, mas o capitão conseguiu levá-las até um remanso, onde aguardamos que o temporal passasse. Tinha lugar para amarrar as redes, e a viagem durou três ou quatro dias, navegando dia e noite.