MAHURANGI CRUISING CLUB YEARBOOK 2025

FIERY CROSS

Frank Young recalls growing up on a boat with a canting keel

GERRY CLARK

Sailing deep into the Southern Ocean on a bird-watching voyage

TONNANT

A major refit and a sail around New Zealanddoes life get better?

Easy breezy

Specialist boat insurance allows you to protect your yacht and spend more time on the water, worry free. We’re on the water too. See you out there!

Local experts making insurance easy.

SAFETY COMPANIONS TO TAKE ON YOUR NEXT ADVENTURE

COMFORT FOR THE WHOLE FAMILY OR THE OFFSHORE ADVENTURE!

DECKVEST LITE & LITE+

Available in a range of colours the jackets designed to be lightweight, low profile added comfort. The Deckvest LITE+ range has an integrated deck safety harness with a soft loop safety line attachment point.

DECKVEST 6D

Designed for open water, coastal and offshore activities. Available in 170N & 275N models

NEMO

Recommended for infants more than 15kgs and children between 15-30kg. Comes with a back harness for a safety line (keeps small hands away from the clips) and has a front hand-only grab handle for adults to life the child to safety, cleverly designed to reduce snagging risk.

FIDO

Designed with the same precision and quality as marine safety equipment, the FIDO flotation vest provides buoyancy and comfort, allowing dogs to embrace adventures with confidence.

PROVEN TO SAVE LIVES

PLB1

Compact, light and the smallest personal locator beacon in the world utilises advanced technology to broadcast your distress signal to global search and rescue authorities, ensuring swift assistance when it matters most.

EPIRB1

Your lifeline on the water. Fitted to your vessel, it sends a distress signal with precision, facilitating a rapid response to your location.

MOB1

The best chance of rapid rescue if you fall overboard comes from your own vessel. Once activated your MOB1 will transmit an alert to all AIS receivers and AIS enabled plotters in the vicinity. The integrated GPS ensures precise location is sent to your vessel and any others that may be able to assist.

PLB3

Multiple levels of integrated signalling technology including 406 MHz and GNSS (GPS, Galileo, Glonass) positioning. The addition of AIS (Automatic Identification System) transmissions means the PLB3 AIS Personal Locator Beacon simultaneously alerts all vessels equipped with AIS transponders within the VHF radio range of the PLB’s distress position. This greatly increases both the likelihood and speed of rescue since nearby vessels receive the alerts.

Deckvest 6D Nemo

Fido PLB EPIRB1 PLB3 MOB1

MAHURANGI CRUISING CLUB

Encouraging cruising and the ownership, use and restoration of wooden boats

Warkworth, New Zealand. Website: mahurangicruisingclub.org

Mahurangi Cruising Club

Issue 24 - December 2024 - ISBN 1174-9725

DESIGN, PRODUCTION & EDITING

STEPHEN HORSLEY - Ngatira srhorsley@gmail.com M: 027 280 7497

SUB EDITORS & PROOFREADING TEAM

Jill Hetherington - Tuna

Margaret Howson FACT CHECKING

Martin Howson

EDITOR’S NOTES

I came to the realisation lately that perhaps I’m in the category of a person who prefers to work tirelessly on his boat rather than go sailing. Perish the thought! But reality you can’t scupper. It’s been five years since trucking my beloved Ngatira home to fix a few leaks. A worldwide pandemic and some other work commitments slowed the process somewhat and the list of jobs developed and grew into a tome of enormous proportions. Finally, at the time of writing this, she is only weeks away from relaunching. Enjoyable? Sometimes. Frustrating? Definitely, but very satisfying and a certain pride at what I have achieved encircles me. I only hope I do get to enjoy being on the water and not worry about scratching the varnish!

We all have a certain pride in our boats no matter what the shape or size and I would like to remind you that this Regatta is sailed under COLREGs - Preventing Collisions at Sea.

Rule 5 requires that “every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision

So technically, luffing a boat is not the proper sailing etiquette. Particularly in the starting procedures where things can get a little tense. Please be mindful of this.

It was sad news for the Club to farewell Helen Johnson earlier in the year, a founding member and partner of Peter Oxborough. She worked unstintingly as the Club treasurer from the very beginning and at the beach entry tent every year. Helen was ‘old school’ and computers were not her thing, all records and financial reports were meticulously handwritten.

As always a huge thanks to our regular contributors and Roger Mills for his stunning photos all of which make this Yearbook a decent publication. I know I can be a bit like a terrier chewing on a trouser leg to get those words out of you but we are grateful when you do respond with your wonderful stories and tales.

Cover: The newly restored Rogue.

Photo: Roger Mills. Hummingbird Video and Photography Proudly printed by

MAHURANGI CRUISING CLUB

OFFICE HOLDERS and Committee 2024 - 2025

COMMITTEE

Selene Buttle

John and Carolyn Caukwell

Jacques De Kervor

Jill Hetherington

Ngaire Hopwood

Stephen Horsley

Margaret Howson

Svetlana and Boris Penchev

CONTACT:

MAHURANGI CRUISING CLUB office@mahurangicruisingclub.org

COMMODORE & SECRETARY office@mahurangicruisingclub.org

VICE COMMODORE hughgladwell@gmail.com

Copies of this Yearbook are available from the Club’s address at $20.00 each, or free in exchange for a copy of their Yearbook, to any club with similar interests.

Payment can be made online to 12-3095-0126805-00

ACTING CLUB CAPTAIN

TECHNICAL ADVISOR

JAMES BUTTLE Achernar

REGATTA TEAM

Handicappers

Hugh Gladwell

Richard Dodd

Yearbook Team

Start Boat

Richard Dodd

Bryan Taylor

Selene Buttle

Stephen Horsley Editor - Design & Production

Victor Hopwood Sales

Debbie Whiting Advertising

Proofing Team

Margaret Howson - Captain

Jill Hetherington - First mate

Martin Howson - Referee

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Become a member and be informed of our yearly activities.

Still the cheapest in the Southern Hemisphere $15 for the coming year.

Payment can be made online to 12-3095-0126805-00 with or without your entry fee by 12th January 2025.

RICHARD DODD

VICTOR HOPWOOD Starlight Lorax

HUGH GLADWELL Gallivant

HUGH GLADWELL Gallivant

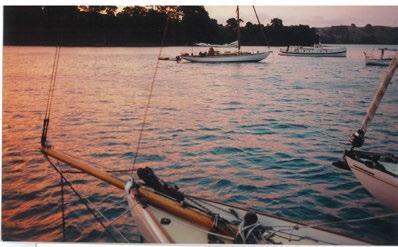

IVice Commodore’s Report 2024

t would be fair to say that the Mahurangi Cruising Club is basically an eating and drinking club with a side hustle of some occasional light air sailing. It was started by a group standing around a fire on Motutara Island in 1988 discussing how much they disliked yacht clubs. They decided to form a yacht club where there would be no points of order, no protests, no working bees and no assets. If there was any significant disagreement at any time the Club would be wound up immediately and they would forget it ever existed.

Thirty-six years on we can say that we have achieved that level of inactivity we aspired to so long ago. Other clubs in that time have built large clubhouses, hard stand areas and marinas. Our fixed assets consist of some rusty anchors and four inflatable buoys, three of which suffer from erectile dysfunction. Meetings used to be held aboard various members’ yachts, initially Sorceress in a mud berth in the Mahurangi River (near Warkworth) then Maggie, the large schooner at Sandspit. We had about 10 sailing events each year initially but have managed to whittle them down to two or three. With advancing age most of us are creek crawlers these days, sailing timidly along the coast, but the days of gales at sea during ocean passages are relived vividly, with a lot of exaggeration, at meetings which have now moved ashore.

Our bona fides as a yacht club have only been saved by this Yearbook and the Mahurangi Regatta. The Yearbook first came out in 1999 with doubt from some of us that it would ever see the light of day again, but it has continued almost every year since as a high-quality publication, with a collection of all copies now worth thousands. Someone reported that a friend had read one in a dentist’s waiting room in France. A friend of Des Townson, the yacht designer, told me that he asked Des if he could borrow a copy when he was at Des’ house. Des said he could read it there, but it wasn’t going outside the door. That must be high praise indeed. I heard that Des had looked over a recently launched boat from another designer and he said on leaving that he could see a certain amount of thought had gone into it but he couldn’t countenance the appearance of it!

The Mahurangi Regatta allows the Club to bask in the reflected glory of the magnificent fleet of classic yachts and launches which

grace our shores each year. Some have had a fortune spent on them. A study recently looked at why older men often spent so much money on classic boats. The answer was that when you get old there is nothing else to spend money on. The days of wild parties which leave you feeling ill for a week are gone. You are invisible to women beyond a certain age. There is no point in rattling around in a big house and people comment that the latest car is wasted on an old guy.

We as a Club have sadly suffered the ravages of time. Some of our founding members are no longer with us. We lost Helen Johnson earlier this year. Helen was our treasurer for countless years and valiantly carried out a job which none of the rest of us wanted to know about. Mike Webster was a long-time member who has also crossed the bar. He owned Northerner the 50ft A-class Keeler for many years. He used to hoist the spinnaker during the Devonport Yacht Club single-handed race and told me that he would try and get under the lee of an anchored ship to drop it!

Many older yachtsmen tell me that their partners won’t sail with them anymore. The decision is probably sensible recognising the skipper’s declining physical and mental abilities. There is some good news. The University of Sheffield is trialling a robot to crew on a yacht. It can hoist sails, pull in the jib, cook a basic meal, bait your hook, fillet fish and light a fag. The female version wears a bikini all year round and the male version a pair of Speedos. The cost will be about NZ$40,000 which is expensive but a regular crew which you will no longer need can probably eat and drink their way through that amount in a few seasons.

Enjoy the summer!

Hugh Gladwell Vice Commodore

"The cabin of a small yacht is truly a wonderful thing; not only will it shelter you from a tempest, but from the other troubles in life, it is a safe retreat."

- L. Francis Herreshoff, Boat Designer

Beach gathering on Motutara. STEPHEN HORSLEY

UPDATES:

Following on from Nick Atkinson's article Bananas For Each Other in the 2021 issue (p60), Tom and Beth Bertenshaw tied the knot in March 2024 at the Duke of Marlborough, Russell. Not only did they get married but have had a beautiful daughter and upgraded from weekend sailing on the Townson 28 Rosana to living aboard the Warwick 44 Alice Bee (formerly Pacific Belle). They've spent

these last few years sailing between Auckland and the Bay of Islands - which is now looking to be their base of operations for their next adventures.

Presented by

REGATTA EVENTS 2025

The Mahurangi Regatta an annual event held every Auckland Anniversary Weekend - this year on Saturday 25th January 2025.

Mahurangi Cruising Club conducts the sailing events on Mahurangi Harbour.

Mahurangi Cruising Club www.mahurangicruisingclub.org office@mahurangicruisingclub.org

REGATTA PRIZE-GIVING

Will be held at Scotts Landing from 1900 hours or as soon as results are confirmed.

Classic Yacht Assn. Takes entries for the Classic Launch Parade. admin@classicyacht.org.nz

NOTICE TO ALL REGATTA PARTICIPANTS:

Regatta start times have been bought forward and will now start at 1100hrs

FRIDAY 24 JANUARY 2025

Passage Races from Auckland to Mahurangi. (Devonport Yacht Club, CYA and other yacht clubs). Sandspit Yacht Club Perna Cup Mahurangi Weekend.

SATURDAY 25 January MAHURANGI REGATTA

0930 hours CYA Parade of Classic Launches from Scotts Landing to Sullivans Bay.

1100-1600 hours Mahurangi Regatta. Refer to the Notice of Regatta and Sailing Instructions.

1900 hours Prize-giving starts on the lawn adjacent to Scott Homestead at Scotts Landing. Some Barbecues will be provided.

SUNDAY 26 January

1030 hours CYA B Classic and Modern Passage Series race to Auckland.

1100 hours CYA A Classic and Modern Passage Series race to Auckland.

1800 hours Gather at the Kawau Boating Club, Bon Accord Harbour. All welcome.

Ponsonby Cruising Club race from Mahurangi to Bon Accord Harbour.

MONDAY 27 January AUCKLAND ANNIVERSARY DAY REGATTA

Auckland Anniversary Day Regatta with starts from Westhaven. Auckland Anniversary Day Regatta Passage races back to Auckland from Mahurangi and Kawau Island.

MAHURANGI REGATTA

The Regatta will be held in the classes and divisions outlined below. These races will be held in accordance with the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea.

Entries to the Regatta are made online.

For detailed information about participating in the Regatta, please refer to the Notice of Regatta and the Sailing Instructions obtainable from mahurangicruisingclub.org, or our facebook page.

MAHURANGI REGATTA DIVISIONS

TE HAUPA DIVISION

For traditional small boats under 20ft overall. This will include all traditional New Zealand classes like Zeddies, IA’s etc. Includes any other traditional style of boats such as sailing outriggers, proas, and sailing dories.

SAILING DINGHY DIVISION

Frostbite, Mistral, Zephyr, Sunburst & other centreboard classes.

A CLASS DIVISION

For yachts previously registered as A class yachts and other pre 1985 yachts over 12.2m (40ft) length on deck, unless an exemption is applied for and granted by the Regatta Committee. They sail for the A class Trophy and the Logan Trophy.

MAHURANGI DIVISION

For wooden boats pre 1955 design. Only for all-wooden construction. Includes Mullet Boats other than the L class.

L CLASS MULLET BOAT DIVISION

Traditional class of 22ft ballasted centreboard yachts.

TRADITIONAL SPIRIT DIVISION

For boats of any age, type, materials and construction that conform to the traditional spirit of a design pre-dating 1955 and is not eligible for the Mahurangi Cup. i.e., Is a modern design which is a close replica and built in the spirit of a traditional design but perhaps has more modern materials or construction. Includes H28 Class.

MID-CENTURY CLASSIC DIVISION (Modern Classics)

For yachts of any construction designed before 1985 and are longer than 6m (20ft) on deck and not eligible for the Mahurangi Cup or the Traditional Spirit Division. Includes Stewart 34 class, Reactor class.

REGATTA GENERAL INFORMATION

PLACE NAMES

On N.Z. Maritime charts, place names do not appear with their commonly used names. Sullivans Bay, where beach and dinghy races are held is marked Otarawao Bay. Scotts Landing where the prize-giving is held is not named on charts. It is situated between the wharf carpark at the end of Ridge Road and Casnell Island and is easily recognised by the Scott Homestead, the only building on the waterfront.

SCOTTS LANDING WHARF AND PONTOON

The wharf is only accessible by yachts at high tide. At low tide it almost dries out. Please use the wharf only for the transfer of people and supplies and not for docking. Ensure the working side of the pontoon is kept clear at all times especially when tying up dinghies to the wharf.

CLEARWAYS

There are clearways marked by buoys in Sullivans Bay for the Launch Parade and the shore activities. Be aware that your boat may swing into the clearways as the wind direction moves or on the change of tide.

PLEASE KEEP CLEAR AT ALL TIMES.

PARKING AT SCOTTS LANDING

Due to the very limited parking available at Scotts Landing and the narrow unsealed road towards the end, please use the signposted parking areas. Access must be kept clear for St John Ambulance and other emergency vehicles.

SANITATION

Some portaloo toilets are provided at Scotts Landing near the Scott Homestead. Please use your holding tank responsibly. Do not discharge boat sewage from vessels in the harbour. This is very important with the large influx of vessels in the harbour for the weekend. Mahurangi Harbour supports a large area of marine farming and we wish to keep the water quality high and also clean and safe for swimming. Please use rubbish bags where available, otherwise take your rubbish with you when you leave.

PRIZE-GIVING

Trophies and prizes will be presented as soon as the results have been decided about 1900 hours in the vicinity of Scott Homestead at Scotts Landing. The recipients can take photos with their trophies. Trophies must be returned to the trophy table before the end of the evening.

REGATTA COURSES

For information about the courses sailed in the Regatta, please consult the Sailing Instructions 2025. Also available at mahurangicruisingclub.org

TIDES FOR THE MAHURANGI HARBOUR

SATURDAY 25 JANUARY 2025 High Water 04:31 hrs 2.38m

Water 10:40 hrs 1.09m

Water 16:33 hrs 2.38m

Water 23:03 hrs 1.00m SUNDAY 26 JANUARY 2025

REGATTA 2024

Janette, Morvarch, ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Orion II, ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Classico - Frostbite ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

InnIsmara A81 STEPHEN HORSLEY

Korora ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Destiny II

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Rose ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Ida ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Kaikoura ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Mistress ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Kotuku ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Scott, Gloriana ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Melita ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Allons-y ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Karina ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Buccaneer

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Lady Adelaide ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Kumi ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Launch Parade ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Jane Gifford and Rogue ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Orion II ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

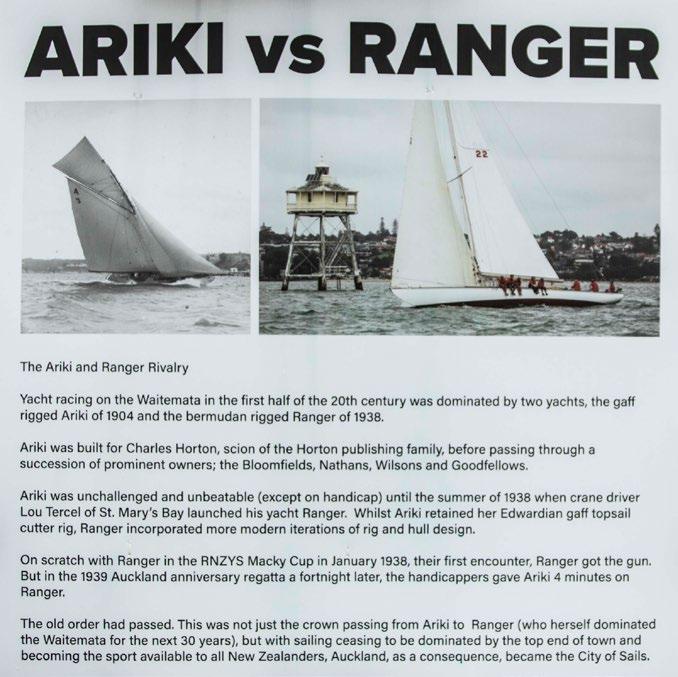

Ariki ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Talent 3116, Diamonds 5910

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Carona ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Buona Sera ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Korora ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Nordic ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Nor West ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Launch Parade, Sullivans Bay ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Raindance STEPHEN HORSLEY

Coastal Rover ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Raiona ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Nereides ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Moana Lua ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Lucinda ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

My Girl ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Ferro ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Carona ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Morvarch

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Jane Gifford ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Princess ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

RAWHITI STEPHEN HORSLEY

Innismara ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Strega ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Love ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Animal House

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Lady Shirley ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Gloriana, Kate, Frances, Gypsy, Princess ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Penury ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

St Clair ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Vega ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Meola ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Rainbow ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Zarapito

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Feather ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Ngaio ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Breeze ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Prize ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Flyaway, Shearwater II

ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Gypsy ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD Hannah ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD Komuri ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD Scout ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Jane Gifford ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Karina ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Launch Parade ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Eileen Patricia ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

Surprise ROGER MILLS - HUMMINGBIRD

NICK ATKINSON Putting the rad in Trad

Bring back the Mahurangi lay day!

Iwas lucky enough recently, to become the proud owner of a vintage opinion. Indeed this particular point of view was long past its heyday. The fresh water and hard southern sunlight had weathered it until a change of the racing calendar had made it all but obsolete. But over the winter I tended this opinion, hoping to restore it to its former glory. I’d be lying if I said there weren't moments when I’d wanted to cut down its lofty scope. I even considered constructing a political abomination that would rise above its original sweeping sheerline. This winter however I’ve tried to keep it simple, sanding and shaping a minimum of new phrases and digging out the soft wood of other agendas. As Herreshoff once said: “Perfection is achieved not when there’s nothing left to add, but when there’s nothing left to take away”–or were those the words of Bruce Lee? Actually it was the pilot and writer Antoine de Saint-Exupery, but perhaps this entire argument needs a roundhouse kick to the bilges.

Launching a freshly refitted opinion into the boisterous seas of social media and gale-force comments /threads can be daunting. Before I grease up the slipway in readiness for this point of view I must haul tight on the first reef of public discourse; this is not personal in any way. If you sail, crew or merely gaze appreciatively upon an old boat you have my eternal and sincere goodwill. It's a precious community we share, but I’d be naive to think that the lines of this opinion won't offend the eyes of some local mariners.

Without further ado let us smash the champagne bottle on the bow of this opinion before we hoist and trim its sails, while appreciating its original craftsmanship and storied history.

Bring back the Mahurangi lay day!

I'm not trying to diminish the considerable legacy of the Anniversary Day races on the Waitemata. The epic fleets with crowds lining the shoreline are memories we’ll always treasure, but we're not anywhere near recreating that atmosphere and I dare say we never will again. That time has passed, which doesn’t make it any less wonderful or worth celebrating. For the last few years the classic fleet for the Anniversary Day harbour race has been no better or worse than many of the excellent traditional boat races laid on by the CYA and associated clubs. But that race comes at the cost of the Mahurangi lay day and our precious long weekend and while it may be difficult to pin down the price of losing that lay day I do want to try.

As we know the Mahurangi Regatta in its current form is by far the largest annual gathering of traditional boats in this country and you’d have to travel for quite some time to find an event that attracts more wooden boats and on-thewater spectators. I’m preaching to the choir talking about the time and effort that goes into campaigning a vessel at Mahurangi and it seems such a shame to break up the fleet so quickly and head for home when we’ve all got an extra day off. Isn’t that kinda mad?

The value of the lay day is priceless and this community has potentially deprived itself of so many connections and experiences while trying to follow the frowning pursuit of four consecutive days of racing. The one-two punch of the Friday night race followed by the Saturday Mahurangi

Regatta and party is not to be underestimated. A day off on Sunday makes sense on so many levels. The skippers, crew and support teams all need a chance to recover and this lay day is such a unique opportunity to explore the islands and meet other sailors.

They say we enjoy our leisure time less when it’s planned in great detail. That may not strictly apply to

classic yacht racing, but it’s certainly true of your average day off. We all know the feeling of dread as an intricate itinerary of travel and events looms up on the weekend horizon.

Anniversary Weekend can feel a bit like that too. There are so many people we only see at Mahurangi and we just want the chance to chew the fat with them, maybe plan some grand restoration and perhaps found a new boatyard. At least we could share a nice anchorage nearby and enjoy a swim. One of your budding crew might truly fall in love with old boats during the lay day, rather than be scared off forever at the relentlessness of the racing programme. I think we’ve lost the only day of the year when all the lovely old boats and their crews are all together with a little time on their hands. This is such a precious asset – a Sunday at a beautiful anchorage with endless legendary boats cast about like some epic lolly scramble of timber. Let us race home on Monday with a little more gas in the tank.

You know what they say about opinions, eh? I guess my conviction that Anniversary Weekend had a far more festive feel with the race back to Auckland scheduled for the Monday is pretty deep rooted. That was my first experience of Mahurangi in the early 2000s when as I skippered Tawera we won the Mahurangi Cup after a ding-dong battle with my boss at the time, Chad Thompson welded to the helm of Prize. The following Sunday I rowed around the crowded anchorage catching up on the gossip from the night before, cooked some eggs for the crew and read a couple of articles in the Yearbook. I don't know who suggested a sail to one of the nearby islands, but I do remember the passage felt effortless, with the crew now well-drilled after two demanding days racing.

We’ve given the current four-days-of-racing format a good run for several years now and the turnout for the Anniversary Day harbour course is, on balance a little less than the more popular CYA harbour races during the rest of the season. A number of the boats that do end up racing home on Sunday don't compete on Monday for the simple reason that they're completely spent. I think the Mahurangi Regatta and the values and atmosphere surrounding the event have helped pave the way for the growing enthusiasm for traditional boats. It’s also a unique chance to live aboard for a few nights with mulleties, A-class, Townsons and Woollacotts all bobbing around in close company. A day off on Sunday means we can improvise, we can jam. Even the bass player can take a solo before the band comes together to bring it on home on Monday with one last resounding chorus of sail headed south. Who would have the tireless sailor work on a Sunday?

Especially in this tidal paradise.

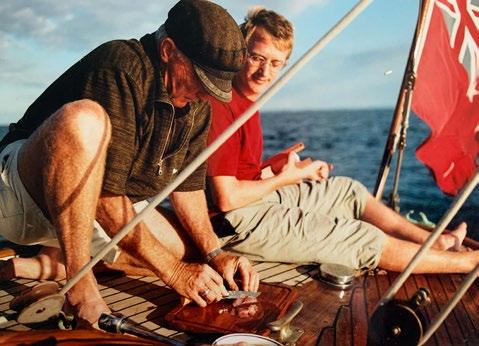

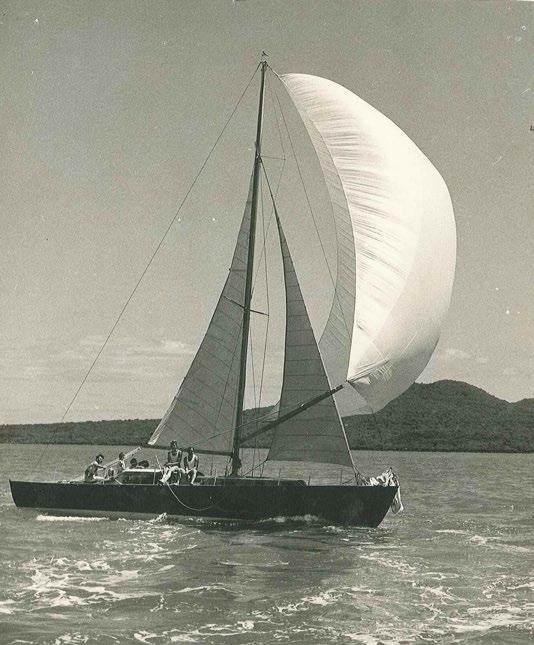

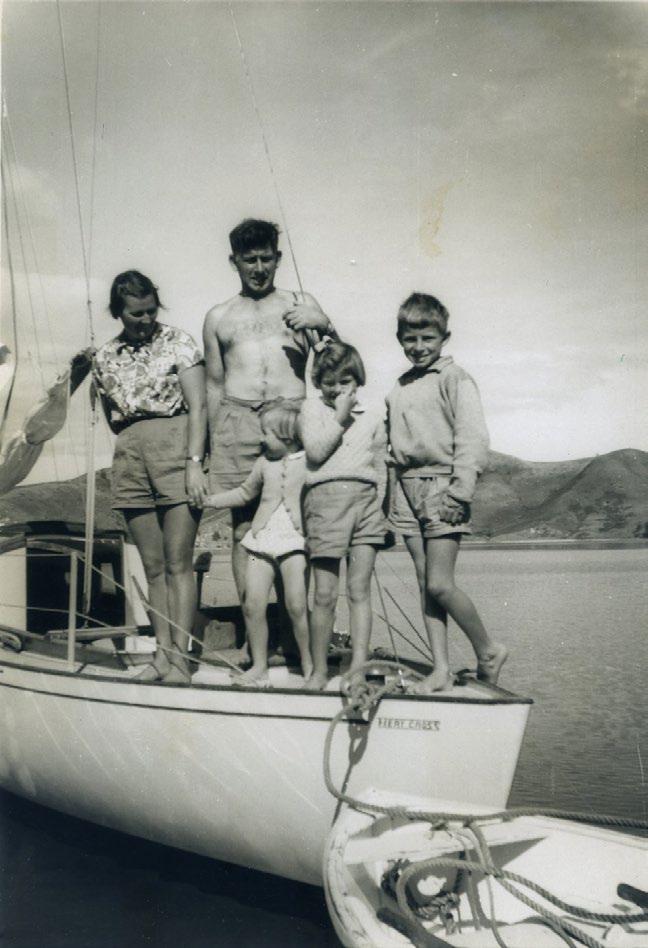

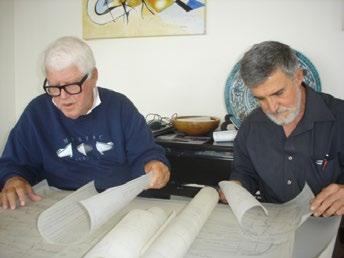

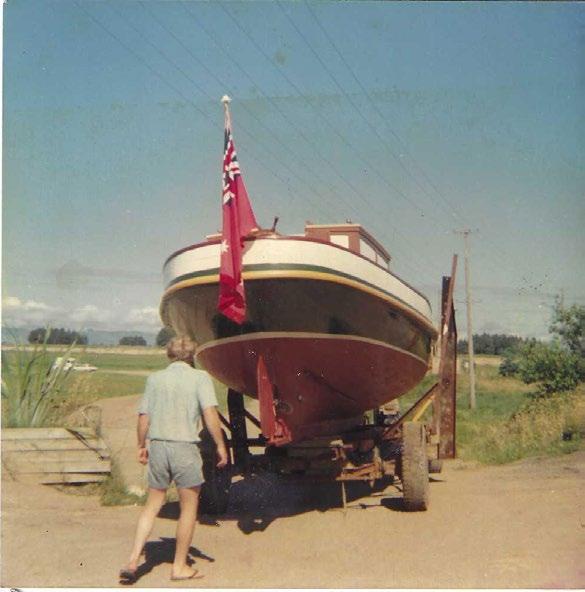

Growing up with the Fiery Cross and a canting keel.

A PERSONAL STORY BY Frank Young (son of Jim Young)

The swinging keel, known nowadays as a canting keel was a novel idea that attracted my father very much. He felt vindicated when canting keels were finally allowed in racing in recent years, but it took a long time. He had always been fascinated by new ideas in boats and always willing to try them right until his last days. He maintained that the fun you have while sailing is directly related to how fast you are sailing and being close to the water makes it better yet.

“Keep quiet, I am on the phone to America”. Wow, America! That was a big event in 1955. Book the call with the Post & Telegraph. Make sure the budget was sufficient to pay for the call. Be sure you had everything ready so not a minute was wasted on the limited and expensive call time allocated.

Why the big call? My father Jim Young was in regular correspondence with noted American designer L. Francis Herreshoff whose book The Commonsense of Yacht Design was a guiding reference for him as it has been for many other yacht designers. Earlier correspondence had convinced my father that Herreshoff’s ideas about a canting keel for a sailing yacht were worth a try. Herreshoff was more than happy to find somebody prepared to do it. Now the design of this 45ft-long boat was nearing completion and construction was about to start. Questions, doubts, reassurance? His belief that yacht design was too conservative and new ideas were actively discouraged was being put to the test. Time for an international phone call. A big event in those days. That is my earliest memory of the Fiery Cross.

My mother Margaret Paterson was a successful yachtie in her own right, rising to national prominence in the Silver Fern class in the late 1940s when competitive female sailors were unheard of. The daughter of a yachting family with family history going back to the first settlement of Great Barrier Island in the 1870s she married a nearpenniless boatbuilder, and successful yachtie, Jim Young.

The area of Willow Bay, Birkenhead, the sheltered western corner of Little Shoal Bay near Needles Eye (Upper Waitemata Harbour) had been owned by the Taylor family, who are cousins. The Lady Stirling was built and owned by the Taylor family and was kept on the slipway in Willow Bay. The skipper of Lady Stirling was my grandfather Arnold Paterson. So this corner of Willow Bay was a good spot for boatbuilding, complete with a slipway, and a family history. My father managed to acquire the property and that is where he started his boatbuilding business.

My mother always wanted a boat for cruising in the Hauraki Gulf. My father went into boatbuilding because he wanted to be a yacht designer and he soon saw that the only way to get your designs built was to build them yourself. So the objectives were somewhat aligned - the design vision perhaps not so much. The design that became the Fiery Cross was not quite what my mother had in mind. Her preference, with my grandfather’s backing, was for a slightly bigger version of the recently built Tango being about as advanced as could be considered reasonable. There is that yachting conservatism again which my father battled with throughout his career. Something as different and ahead of its time as the Fiery Cross was certainly stretching things.

Fast forward a couple of years. The Fiery Cross is a mostly planked upside down hull, (yet another innovation at the time) on one side of the boat shed in Willow Bay. Dad is building her in his “spare time”. His words, not mine. At the same time he, with two or three employees,

is building other boats for customers in the same shed to try to keep food on the table and finance the Fiery Cross. Launches such as Gazelle, Moehau, Lady Claire, Tide Ryder, Ngarunui, and the motor sailer Vermona were some built alongside Fiery Cross. Also a few catamarans. The shed was less than 40 feet long and about 25 feet wide. It was useful that Fiery Cross had only 7ft 2in beam which left enough room in the shed to build other boats, even if her stern stuck out of the shed by about 10 feet and was covered by a tarpaulin.

Spare time boatbuilding and lack of money too, meant that progress was slow. She was constructed with dressed heart kauri diagonally planked over longitudinal stringers, glued with Aerodux Resorcinol glue, and nailed with copper nails. Most work was in the evenings and weekends, often with a bit of help from friends and relatives, my uncle, Alan Young, helping after school with the dolly underneath to clinch the copper nails dripping with Aerodux glue. I was also pressed into work on the

PREVIOUS SPREAD: Surfing past Tapeka Point, Bay of Islands 1964. TOP: Turning over the planked hull in the shed. The canting keel nacelle is clearly visible. ABOVE LEFT & RIGHT: The hull completed, ready for deck and cabin

dolly, especially in the narrow spaces at the bow and stern because I was still young and small enough to squeeze into the tight spaces. I was also required to climb into the small spaces under the cockpit and in the bow and stern to apply the red lead primer.

Slowly the dream was becoming a reality. Fiery Cross was taking shape and attracting sceptical comments. All glued construction? “Never been done in New Zealand before. Won’t last 10 years.” Separate spade rudder? “No use in a sea. You’ll never control the boat. It’ll fall off Tango’s hadn’t yet but it will soon. Just lucky so far.” And a swinging keel? “That is just to cheat in racing. It will never work and it will fall off soon too. Who would ever build a boat like that? I wouldn’t go past North Head in that.” A deck stepped mast? “That will never stand up. The cabin top won’t take it. It's dangerous.” Yeah well, press on regardless. Innovators are not always well understood.

The keel inevitably became a big part of the Fiery Cross

story. First was the lead ballast. One-and-a-half tons of lead had to be acquired by a broke boatbuilder. Some was accumulated by scrounging around building sites and scrap merchants for old lead waste pipes, batteries, and similar. But the main source of the lead was a story on its own.

My grandfather, Arnold Paterson, lived on his 28ft launch Wild Thyme mostly on a mooring in Shoal Bay, Tryphena on Great Barrier.

An old 30ft yacht had ended up wrecked or abandoned on the mud further up Shoal Bay. After being alerted by my grandfather Dad bought the wreck from the insurance company with the idea of salvaging various parts, some of which may be useful on Fiery Cross. The main objective was the lead keel. Just as well he wasn’t relying on anything else because by the time he got to the wreck the only thing left was the lead.

The Barrier locals had helped themselves to anything else of value that could be moved or removed, including the Villiers engine which was soon seen powering a local

TOP: Melting the lead. ABOVE LEFT: Launching day – a good group of helping hands push high tide. RIGHT: Stepping the mast.

trailer contraption, which became something of an icon itself.

The 1959 Easter holidays find the family at Shoal Bay staying in Otways' guest cabin quite close to the remains of the wrecked yacht. High tide meant playing on the beach and swimming. As kids, my sisters Adrienne and Wendy and I were always exposed to boats as you might guess. Wendy was a little young at that stage but my model at that time was a small ship which Dad used to teach me about the characteristics of wave formation by boat hulls, towing it on a stick along the beach. Adrienne’s toy for the beach was a skinny double-ended model made from a piece of kauri. It was called Mummy’s Boat. It was in fact a model of the Fiery Cross and I think was a bit of a selling job by Dad on Mum and the family.

Low tide saw Dad working feverishly to unbolt the lead from the wrecked hull and cut it up into small enough pieces so they could be lifted for transport back to Auckland. A chainsaw was the tool of choice. Not very efficient but effective. Lead is not easy to cut especially lying in mud. After a full two weeks work the lead is ready to transfer to Auckland, along with some night watch work to ensure the now-movable pieces of lead did not go the way of the rest of the wreck’s valuables, although we suspected some did.

Barely able to be lifted by one or two men, the lead lumps are transferred into a 15ft flat-bottom punt that Dad had built as a workboat for the Little Shoal Bay boatshed. This had been towed out to Great Barrier behind Wild Thyme. The lead, total weight perhaps about one ton was loaded onto Wild Thyme with some remaining in the punt, and back to Little Shoal Bay in Auckland we go where the Fiery Cross is nearing

completion, waiting for a keel.

The kiwi do-it-yourself tradition was alive and well in Birkenhead which, before the Harbour Bridge, was a fairly small community where most residents knew each other and helped out. That coupled with financial necessity meant that the lead ballast was to be cast in the yard next to the Fiery Cross. A further advantage was that the hollow mild steel fin could be attached to the lead right where it was cast, the hull then lifted and dropped on, the pins inserted in the canting hinges in the hull keelson, and the keel is attached. The keel assembly consisted of a hollow fin fabricated from 6mm-thick welded mild steel. In the central part at the bottom of the fin is a channel in which a 30 degree angled stainless steel shaft keys in on a square swivelled shoe that slides in the channel. When the shaft is rotated 90 degrees the effect is to angle the hinged keel by 30 degrees. The lead was a simple bulb on the bottom of the fin–not the kind of bulb commonly seen today but an early version, advanced for its time. The mould was built of plywood, reinforced externally with timber, lined and shaped internally with concrete that had been been carefully heated and dried, meant to withstand the molten lead and allow it to be cast and cooled safely.

The big day for the keel casting arrives. There are several yachties and Birkenhead locals there as volunteer labour and “advisors”. Several sacks of coal and coke have been brought over from the Northcote gasworks on the other side of Little Shoal Bay. The mould is ready. Two large cast iron vats have been obtained and set up on bricks and the fires are going, the lead slowly melts, the beer flows, food is served, and everybody is having a great time. Health and safety? Bare feet was the common footwear. Some had gumboots.

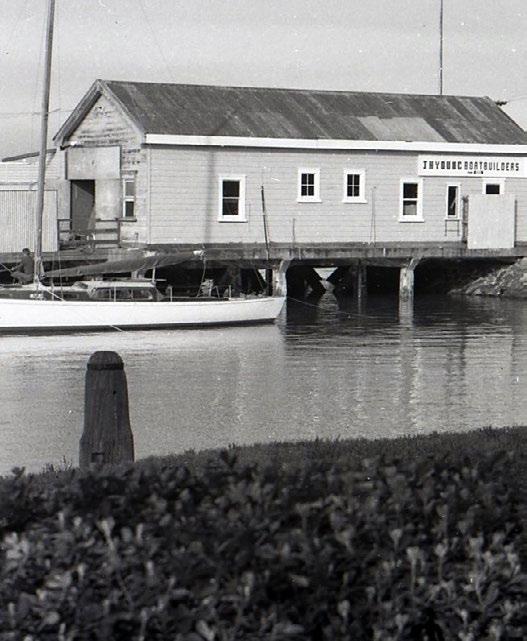

ABOVE: Fiery Cross first sail with a spinnaker, with bamboo spinnaker pole 1959. ABOVE TWO: Lifted at Auckland port for transport to 1962 Boat Show. OPPOSITE: Birkenhead wharf and boat shed 1961.

The molten lead starts to pour out of the pipes into the mould but only after some coaxing with gas torches after it solidified in the cold feed pipes. The mould is filling and the pour is looking good until it is about 75 percent full. Then part of the mould breaks. Hot molten lead is pouring over the ground. Remember those bare feet? Some quick stepping needed but no damage done. Frantic efforts follow to get bricks and pieces of wood to shore up the leaking portion of the mould and avoid a complete disaster. Lots of expert opinions. The pour is stopped while that is done. Still-molten lead is shovelled back into the melting pots or separated into small puddles that can be handled as they cool. Finally things are repaired sufficiently that it is decided to continue.

All this is highly entertaining to me as an eight-year-old spectator being kept a respectable distance away sitting on a stack of timber with instructions to stay there or else! The fires are stoked up again and finally the pour resumes into the evening. Fortunately with no further mishaps.

When the lead finally cools three days later and the mould is removed, two things are apparent. There is an obvious line between the first pour and the second pour and the lead has a large bulge on one side where the mould had sagged and given way. The visible line was determined to be of little consequence and was later filled. However the bulge required removal to fair the lead into the proper shape. A very painful process for some weeks with planes and chisels, the result being that some lead was lost and the keel ended up slightly lighter than intended. A few calculations and it was decided that the lighter keel was not a problem, and so it turned out.

A 2in-thick kauri spacer was added to the top of the lead between the lead and the fin. The righting moment was restored or perhaps improved and all was good.

As Christmas 1959 approaches, Fiery Cross is to be launched and sailing for the Christmas cruise. If not

then the remaining support from my mother might have entirely evaporated. The keel is attached. The boat is painted with a new innovative high tech paint called “Vinylon”. She looks a treat in dark red. The spruce mast is stepped and she is launched on the December spring tide. Wild Thyme assisted to tow her from the cradle, and then a line was attached part-way up the mast, to heel her over enough to float out over the shallow water. Even that was a risky affair as the spring tide was starting to ebb before Fiery Cross was coaxed to move. The keel had its first test although not yet a canting test.

Within a couple of weeks we load up, nothing stowed, and off we go for our first Christmas cruise. Kawau is the first stop. Our arrival in Mansion House Bay on the first evening of the first cruise was greeted by the booming voice of Boy Belvie, owner of Ladybird at the time, “has that boat got as much room inside as it does outside?” A valid question as she was 45ft long and 7ft 2in beam on a double-ended hull. A long and narrow canoe and the interior accommodation was indeed more like that of a 35 footer than a 45 footer.

Then a run to Port Fitzroy in a fresh south westerly, finally anchoring in Smokehouse Bay where Wild Thyme awaits us with my grandfather keen to see that we made it.

Three weeks of cruising at Great Barrier follows. Then by mid-January, not long after returning to Auckland, it becomes apparent that something is not right with the red paint. It is developing big grey patches and looking terrible. This was drawing many questions and comments. Discussions with the supplier did little to establish the cause and I don’t know if it was ever resolved. However by May 1960, Fiery Cross is hauled out at Needles Eye Little Shoal Bay (there was still an eye there then) and the now red/grey blotchy Vinylon is removed. Easier said than done. That stuff was some kind of plastic. It was impossible to sand. Removal was only possible by

burning it off with a blowlamp and scraper and sanding afterwards. A laborious job that lasted much of the 1960 winter. Fiery Cross acquired her white topsides with normal paint after that.

The canting keel attracted much attention. The first was from the New Zealand Yachting Association who required that if Fiery Cross was to participate in any races in New Zealand an undertaking must be signed that the keel will be locked at all times and not moved in any way. Without that Fiery Cross would not be permitted to take part in any racing. With the necessary papers signed, her first race was the 1960 Auckland Anniversary Regatta. No canting keel. No sheet winches. No engine. Heavy cotton sails and a borrowed spinnaker with spinnaker pole fashioned from a large bamboo that grew near the boatshed in Willow Bay. The race was not a great success as we were not really set up for it but our position among finishers ended when we nudged Moana lightly on the stern while rounding Motuihe Black buoy. We thought we had done well to keep up with Moana on our first race. However we were informed by Alf Miller, owner/skipper of Moana that “you’re out, I’m afraid”. The Corinthian yachting attitude in those days was to then withdraw and go home,

OPPOSITE: Collecting water at Governors Pass, Great

but Dad would not let that stop the day’s fun so we sailed to the finish in a respectable position but did not record a result. So went Fiery Cross’s first race. Memorable but not entirely satisfactory.

Then came the efforts to make the canting keel work. Finances had not improved, not helped by the paint debacle. Dad's Vindex launch design was starting to look like a money-maker but not yet. He obtained two hydraulic rams of a type typically used in front end loaders. They were painted a nice light green, suitably adapted, and installed in the bilge on a steel mounting plate that had been built into the bottom of the boat for the purpose and to secure the keel hinge bolts to.

These rams had a heavy chain attached to each. The chain went around a 700mm diameter wheel. This chain wheel was part of a hollow steel shaft assembly of 100mm diameter which was secured at its top end in the cabin top by a bearing in a steel frame and passed through a watertight gland in the steel keel plate and kauri keelson to the 30 degree canting shaft inside the keel. When one ram pulled the chain the shaft would turn and the keel would cant outwards. The opposite ram would pull it back and out the other way.

LEFT: Jim Young and family, Christmas 1960. ABOVE TWO: Jim and family often cruised together with Des Townson when Des built Serene. Picture at Port Fitzroy c 1963. Fiery Cross in her first race Auckland Anniversary Day, January 1960.

Barrier Island.

This was accomplished by a hand pump and a control valve under the cockpit seat. And it worked … sort of. What went wrong? The problem was the hydraulic rams, they leaked – a lot. This meant that air got into the hydraulic system and it was inoperative without frequent system bleeding – like every time the rams were used. The pump would have no effect if any air was in the system. The keel could be pumped to windward if the system was bled, and then would slowly fall back as the system leaked.

Hydraulic fluid is an effective paint stripper. It leaked into the bilges and stripped all the paint from the bilges, up under the bunks, and in the galley too as it made its way everywhere along the stringers as the boat heeled. All a bit of a disaster and no money to buy new better hydraulic rams.

Not to mention more or less the final straw for my mother who just wanted to go sailing and the money had run out. So finally Mum won out. No more money was spent on the hydraulic system and the canting keel continued, unused. The rams were removed along with the hydraulic gear and the bilges were repainted.

However Dad did not give up completely on the canting keel. How about just unpinning the keel and letting it fall to leeward then pin it and tack? Away you go with the keel out to windward. Initial reactions were: What happens if you let the keel loose and it goes 30 degrees to leeward and the boat lays over so far that it cannot recover or you lose control or sink because of water pouring through the cabin windows and the cockpit or ….?

Dad did some calculations and concluded there was no real risk of anything serious happening – although not

completely confident as I recall. So on a nice moderate south westerly day in the summer of 1963 we are on the harbour near Northern Leading Beacon, with Des Townson aboard too. Dad and Des spent a lot of time together in the early 1960s. The decision is made to give it a go. Fiery Cross is luffed up. When upright with no pressure on the keel shaft, the locking pin is removed from the chain wheel which is all that remains of the hydraulic canting mechanism, and then we head off on port tack towards Takapuna. She lays over … quite a long way. The leeward rail is under water but that is as far as she goes. I was there watching with some trepidation, being told by my father that there is nothing to worry about. The keel is pinned in the fully canted position. Then we gybe (not tack for reasons we see later) and head for Browns Island. Off we go, sitting nearly upright and belting along at a good 11 or 12 knots. Relief all round and a bit of “I told you so”, that turned to excitement as the extra performance became apparent.

Call that proof of concept if you like. Not quite the system as originally intended but it made the canting keel a useable and useful attribute. The unpin/lay over/pin and tack method was used on many occasions when we had a good reaching passage, the most memorable being a trip from Auckland to the Bay of Islands in a fresh south westerly. We averaged over 12 knots from Rangitoto Beacon to Cape Brett. Maybe not that impressive these days but quite something in the early 1960s.

How was she to sail with the keel canted? First of all – wet. The long narrow hull was designed to sit fairly upright with the keel canted, be easily driven and slice along on a reach, just as we were doing. That worked very

well but the narrow hull and the added power of the canted keel meant she just sliced through waves and plenty came along the deck.

The loss of lateral resistance with the keel canted meant that at lower speeds there was a lot of lee helm. Similar to a centreboard dinghy with the centreboard up. Upwind sailing was not a big success with the canted keel and tacking with the keel canted was quite difficult. This is why modern canting keelers also have daggerboards but that idea was well in the future. This shows how much was really unknown at the time. The canting keel on Fiery Cross can be considered a qualified success, given the knowledge at the time. Much has been learned about canting keels since, but that knowledge had to start somewhere. A lot of it started with Fiery Cross

The swinging/canting keel was a central part of the Fiery Cross story for some years in several ways. The mild steel fin was a constant maintenance problem. It had not been grit blasted and suitably primed at the beginning, partly due to no money being available, so was constantly showing rust stains and bubbles. The job of sandblasting and priming was finally done on the grid at Westhaven in 1964 which helped a lot. The keel had 3 chambers. The chambers at the front and back were supposedly airtight and dry although that was doubtful as water would trickle out for days after she was hauled out. The central chamber had a removable door on one side for access to the canting shaft, hull gland, and sliding shoe at the bottom. That chamber was always full of water and was a rusty, dirty, maintenance job every time the boat was antifouled. The rusting of the fin looked bad. Electrolysis caused some perceived problems too. It all gave rise to concerns about the long term strength and durability of the fin. Would it fall off one day? These fears were much overstated as it turned out.

The solid lead bulb ballast on the keel was about 600mm wide on its base with a fairly flat bottom at the widest third of its length. It was a hydrodynamic shape and tapered away towards the aft end. The low centre of gravity and the flat bottom section of the keel caused some consternation one night. Christmas 1964 we were anchored in Mercury Cove. A peaceful night with a light easterly wind. About 2 a.m. there is a loud crash, a splash and the sound of water. The boat is now lying over

TOP: Jim in his favorite position. MIDDLE: A typical view forward.

Note the canting keel shaft in the cabin. BOTTOM: Fiery Cross in her revised paint scheme 1961

at about 20 degrees heel. Mum has catapulted across the cabin from her bunk onto Dad. I have fallen out of my bunk. My sisters are OK as they are in the quarter-berths.

Dad gets up in the dark and steps right into water –horrified (you can guess at the commentary) he switches on a cabin light. There we are, heeled as if we are sailing hard pressed. All is quiet except for a tadpole swimming in the water on the floor. It is not immediately clear what has happened in the dark and now quiet night, but the story slowly unfolds. There was a small localized tsunami in progress causing a rise and fall of the tide of about one metre or more at about 30 minute intervals. The tide had receded, and Fiery Cross had sat neatly down on the keel, staying perfectly upright on this calm night as the water level dropped probably to a level that left much of the hull clear of the water.

A slight puff of wind was enough to push her over and over we did go with a big splash. Soon the water came back in and we were upright and afloat again with the anchor straining to hold us against the current. Throughout the rest of the night and much of the next day the cycles of rising and falling tidal surges continued. We moved to a deeper anchorage and safely watched the phenomenon continue. And the water in the bilge? That was a tadpole in a jar of water on the sink bench that my sisters and I were keeping after finding it in a pond ashore! Father was not impressed.

Fiery Cross was used a lot as a family cruiser right from when she was launched. We would go away most Friday nights for the weekend during my schooldays. She had no auxiliary engine for her first two years, again mainly due to money. That meant arriving at school late on a few Monday mornings with a note from Mum explaining that we were becalmed getting home. I think my teachers came to expect it.

The one-and-a-half horsepower British Seagull mounted on the Young 2.8 dinghy tied alongside was good for about three knots but that meant slow progress against an outgoing tide off Devonport. A somewhat marinized Ford 10 petrol engine was installed in the winter of 1962, with

a folding prop and no gearbox – just a clutch. That meant no reverse gear which made for some interesting moments especially when berthing. She is a very easily driven hull being so narrow, 7ft 2in beam, 45ft length and only fourand-a-half tons displacement. The Ford 10 could easily push her along at eight-and-a-half knots and she would carry her way some distance. She was not easy to stop and there were occasional robust arrivals alongside piers or sudden stops in unexpected shallow water.

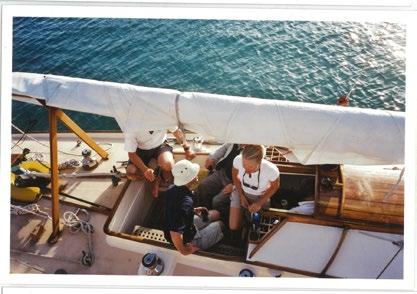

We cruised frequently in company with Des Townson after he built Serene. Des and Dad were good friends in the early 1960s. We first cruised with Des when he owned Storm a 25ft Woollacott which he sold and then built Serene. We cruised on many occasions together with Serene with Alan Young sometimes joining in his catamaran Vitesse.

Des designed the 11ft Dart in 1962. Dad liked the design. It was essentially a hard chine Mistral and Dad built the first three, one of which became mine. It was an early introduction to marketing. My Dart was given number 12. I asked why not number one? I was told that number 12 would make people think there were more around so the boat would be seen as a popular choice. The Dart was part of the entourage often towed by Fiery Cross when we were cruising, along with two Young 2.8 dinghies. It was a great little two-child or adult-and-child boat, fun to sail and easy to build. A shame that the Dart class never managed to achieve the popularity of the Mistral or some other two-man classes.

From a close association, Des and Dad diverged somewhat in the mid 1960s as Des became attracted to the Sparkman and Stevens design style. Dad had a poor opinion of Sparkman and Stevens designs.

On our Christmas cruise in 1966/67 we were in Taemaro Bay between Whangaroa and Doubtless Bay, anchored and having lunch. The usual crowd of seagulls was hanging around looking for scraps. We noticed one not flying and on closer inspection saw that it was dragging its left wing in the water.

Dad always had a love of birds, seeing in them the

Ngarunui and Fiery Cross Port Fitzroy wharf 1962.

unity with nature that he also saw in sailing yachts so we hopped in the dinghy and soon caught up with this obviously crippled seagull. It had been shot through the inner wing joint and the wing was dead, hanging on only by a shred of living skin. We took it aboard, even though it had plenty of fight, biting and scratching as seagulls can. The wing was cut off with scissors and the remaining stump was dressed and bandaged. It was left in the cockpit to recover along with some fish or crayfish which it made short work of. We thought it would not survive the trauma but after a few days it grew stronger and was soon on the aft deck, defending its new territory against all comers.

The seagull became a family pet, cruising with us on Fiery Cross, and later Notre Dame and living by the goldfish pond at home in Narrowneck when not on the boat. It spent the night on the floor of the forward cabin next to my bunk on Fiery Cross. A point that anchored an article in the Northern Advocate two years later, about the seagull “staying in the cabin with the son of the family, Frank”. It spent the night in my parents’ shower when at home and became sufficiently tame that it would quite readily walk indoors with minimal encouragement. When away cruising on Fiery Cross it would defend that long aft deck but in the excitement it would often fall over the side when it forgot it could not fly. It would then swim ashore where we would leave it for hours until we went ashore to catch it and put it back in the cockpit while sailing or in the forward cabin for the night.

The pet seagull became quite famous around the Gulf as an addition to Fiery Cross. It lasted seven years as a pet. It had the measure of all the local cats but a hawk finally took it one day in the yard at Narrowneck.

My mother grew to love Fiery Cross – a very easily handled boat, a very capable passage-maker, enjoyable to sail, and economical to own. In many ways she is a 35 footer with the performance of a 45 footer. All of which appealed to Mum, but perhaps the family time spent cruising the Hauraki Gulf was the main thing that Fiery Cross gave her and that she treasured to her last day.

While I have used the name Fiery Cross throughout this story, as with so many boats the name was only decided weeks from launching when final painting was in progress. Until then it was just “the boat”. There has been some speculation about the origin of the name. It is a simple story but is an insight into my father’s character and interests. Perhaps also some of his motivation in boat design.

My father had a deep interest and fascination with sailing ships and all their history and tradition. Some who knew him may particularly remember his enjoyment of sailors’ sea shanties. He spent many hours telling me about sailing ships and their rigs, the names of the different sails, and some of the famous sailing ship stories. The clipper ship Fiery Cross was arguably the most successful clipper ship of them all. Built in Liverpool, she was the second ship of the same name. The first Fiery Cross was wrecked on what is now known as Fiery Cross Reef in the South China Sea and a subject of some current geopolitical discussion. Preceding Cutty Sark, and the famous 1872

race by several years, Fiery Cross was the first ship home in the tea seasons of 1861, 1862, 1863, and 1865 and was a very profitable performer for her Scottish owners. She was fourth in the Great Tea Race of 1866, finishing just 28 hours after the winner Taeping, and following Ariel and Serica. She did however post the best 24-hour run of all the competitors in this race on 24 June 1866, when she sailed 318 miles, averaging 13.7 knots. So the name came from a very successful clipper ship.

By 1967 the time came to sell Fiery Cross. Dad had decided that he would like to do a bit more competitive racing in an NZ 37 in view of the success of Namu and others built to the same design. The canting keel is back in the picture again. This time it was an obstacle to selling Fiery Cross. A number of potential buyers expressed interest but all were wary of the keel. The idea of laying the boat over and repinning the keel to actually use it was definitely not a selling point. The rust spots on it didn’t inspire confidence and the general impression inevitably led to the question of how reliable it might be and could it fall off? Reluctantly Dad concluded that to sell, the canting keel would have to go and a conventional laminated wood fin structure with the same profile would replace it using the same lead ballast bulb. The remaining canting mechanism was removed and she became a conventional fixed keeler. Today the keel looks the same as it did when it was a canting assembly but a unique development had reached its conclusion. Soon after the keel surgery she was indeed sold. Payment was $8000 plus a 32ft Yachting World Diamond keelboat. Dad wanted nothing to do with that boat so it was mine for a year until it was sold and Notre Dame was acquired as a new project leading to some years of close racing with Flap Martinengo in Namu

Fiery Cross was raced regularly from about 1963 onwards after Dad could afford some decent sails and such luxuries as sheet winches. The success of the Vindex launches after 1960 made a big difference to finances. We broke the spruce mast in 1963 off what is now the Ferguson container terminal. It was rebuilt but eventually replaced by an aluminium spar. She took part in successive Balokovic Cup races including the year that Northerner hit Bollons Rock and sank – 1964 I think. It was blowing a strong north easterly and Fiery Cross was great in a heavy weather reach. I was not aboard on that occasion but was told the story often by my father.

Close behind Northerner and in a good position to win on handicap, they sailed past Tiri, surfing towards home. Then they saw distress flares nearby. They dropped most sail and made it back upwind to where the flares were sighted. They finally found the coaster that had rescued the Northerner crew and came close alongside. One of the rescued crew was Max Carter who built Northerner He called across “Hey Jim, we sank the Northerner”. Not usually lost for words my father could think of no response until he finally said “Oh bad luck”. To his last day he wondered what else he could have said. They were given a one hour time allowance for the rescue effort but that was not quite enough to win.

Most of the longer races were run under the RORC

rating rule, predecessor to IOR. Fiery Cross with her light displacement and narrow easily-driven hull was heavily penalized under that system so was not competitive on handicap. That might have been the day but it was not to be. My father never agreed with the philosophy of the rating rules which he believed penalized performance and encouraged poorly performing boats that were difficult to handle and in some cases demonstrably unsafe. He relented somewhat when he designed the half tonner Mama Cass, then later the One Tonners Checkmate and Heatwave, all aimed at IOR racing.

The swinging keel, known nowadays as a canting keel was a novel idea that attracted my father very much. He felt vindicated when canting keels were finally allowed in racing in recent years, but it took a long time. He had always been fascinated by new ideas in boats and always willing to try them right until his last days. He maintained that the fun you have while sailing is directly related to how fast you are sailing and being close to the water makes it better yet.

This philosophy drove him to design, build, and promote catamarans through the 1950s and 1960s, again with strong resistance from the marine establishment.

Difficult to imagine today with all the catamarans around but in those days they were seen as a dangerous threat. The success of Kitty in the 1959 12ft Interdominion champs only added to the resistance, with catamarans immediately banned.

Fiery Cross was a unique boat, very advanced for her time. Dad’s innovations on her, and his love of catamarans, were a personal part of his life-long crusade for higher performance and more fun in yachting within the reach of the ordinary bloke. I hope Fiery Cross finds an owner who can take care of her and add to the story.

A recent posting on facebook had Fiery Cross hauled out at a Whangarei Yard and free to anyone on the proviso that it would not be chopped up. Looking tired – it has been rescued and is currently under a slow restoration. The hull is sound but the decks are rotten and the interior looking very scruffy.

No One Ever Regretted Buying A Colin Wild Boat.

by Alan Houghton: PHOTOS: Waitematawoodys.com

Aquestion often asked around the docks isdid Colin Wild design/ build anything other than beautiful boats? The classic launch Rehia (Maori translation is pleasure) is testament that he did not.

Rehia was built for Gordon Bartlett and launched on 26th January 1939, her measurements being LOA 37’4”, beam 11’10” and a draft of 3’3”.

Bartlett’s ownership was brief and she was sold shortly after launching to a Frank Pidgeon. Fast forward a couple of years to 1943 when New Zealand was at war and Rehia was one of many motor vessels enlisted into service by the New Zealand Navy for harbour boom patrol operations. Several New Zealand harbours were protected with anti-submarine net booms during the war. Rehia’s patch was the boom off North Head, Auckland and during this period she sported the NAPS (Naval Auxiliary Patrol Service) number Z15 and her owner Frank Pidgeon was skipper.

Post World War II

Rehia was sold to Bill Ryan who deserves a medal as Bill resisted the urge to modernise the layout/style of Rehia Post war this was a common trend that coincided with the arrival of American boating magazines like The Rudder. In New Zealand it is very rare for an early classic to survive without having being fiddled with by, at the time, well-intentioned wooden boat tradespeople.

For Rehia to have reached the grand old age of 86 years and still be more-or-less as launched, is probably down to two factors, the first being that her designer/builder got it right first time. The quality of materials, construction and craftsmanship is evident throughout Rehia, the second is having a succession of educated, respectful owners who appreciated what they were custodians of - a craft that retained her original aura, character and pedigree. And if there was a third factor - deep pockets or at least enough to retain the best tradespeople to care for her.

TOP: The Telfords enjoying Rehia during the summer months. REMAINDER: Work being carried out at The Slipway Milford Yard.

Throughout the years Rehia has been maintained to a standard that would make Colin Wild smile, and at the same time had the addition of modern systems and technology to ensure the best in safety and home comforts.

After an extended period of ownership Rehia changed hands in late 2021 to the Telford family - Amanda and Joe - who are committed to continuing the rolling restoration having already committed to upgrading her systems and addressing some deferred maintenance issues. They commissioned a JPPJ (a Jason Prew paint and varnish

job) at The Slipway Milford yard. The Telfords use Rehia every summer as she was designed - a comfortable family cruiser - then undertake her upgrades and maintenance in the off-season.

Rehia always gathers admiring looks and comments when under way or at anchor, but I believe the true measure of a boats beauty is found in a saying that I believe originated from L. Francis Herreshoff that goes like this - “if as you walk away or row away from your boat, you do not look back at her, you own the wrong boat”.

THE WORLD’S FINEST WOODEN BOAT VIDEOS

Norwegian Faering

Alaskan Trawler Bahamian Runabout

Mullet Boat

STRICTLY FOR THE BIRDS

WORDS: Frances Walsh

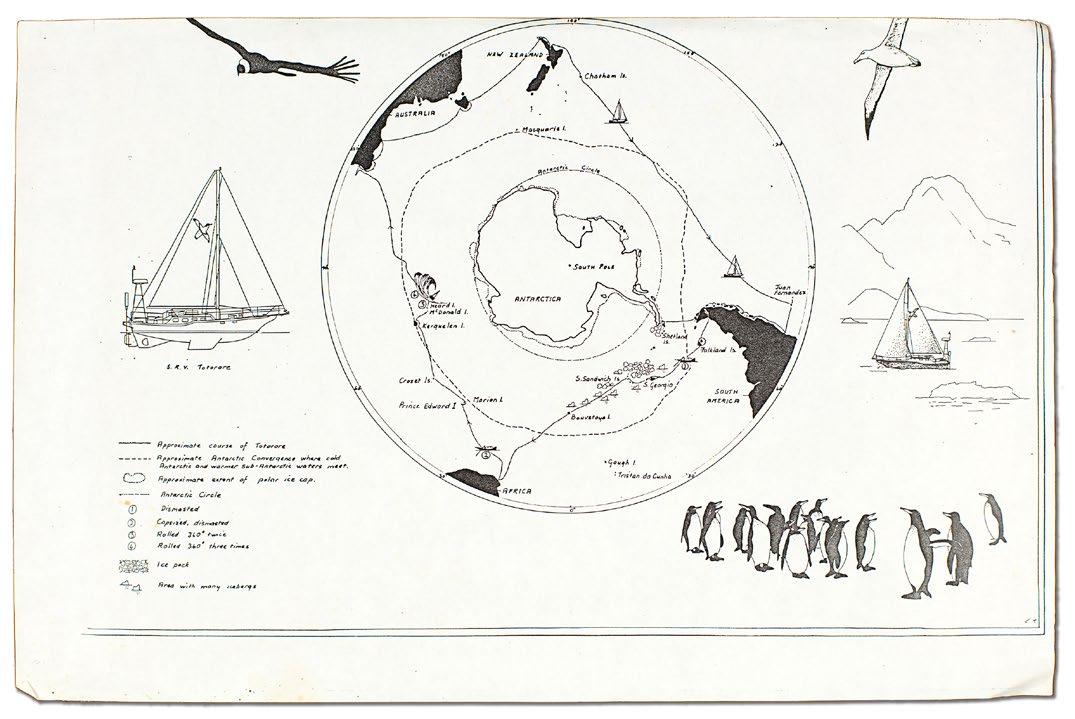

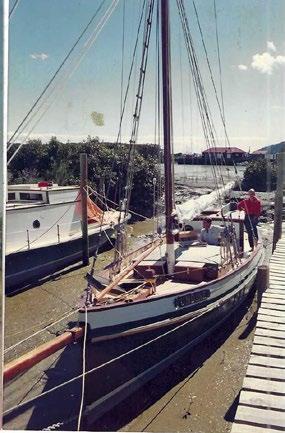

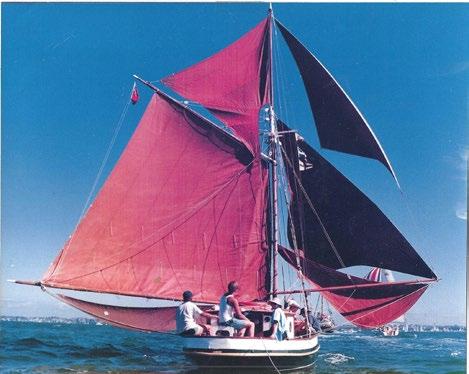

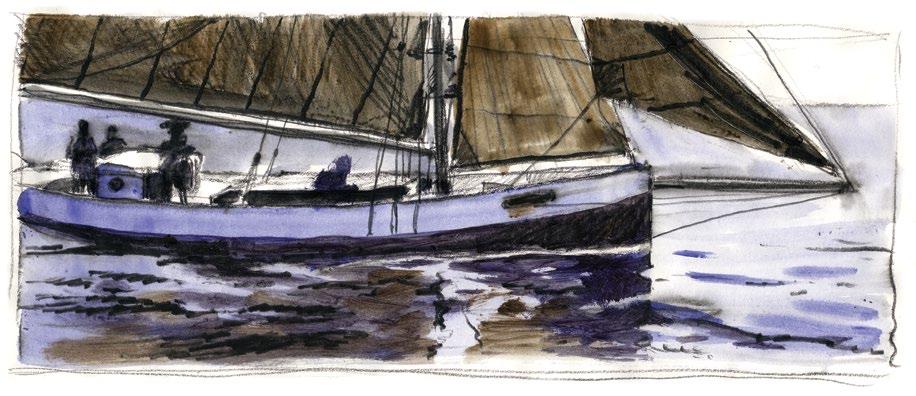

For three years, eight months and 16 days in the 1980s Gerry Clark was a man on a derring-do mission. In his small yacht Totorore he chalked up 38,500 nautical miles, sailing from Kerikeri to southern Chilean archipelago and then to Antarctica all in the service of the seabirds of the Southern Ocean.

By 1958 the English-born Gerry Clark was living in Te Tai Tokerau with his wife Majorie and their four children, developing an organic orchard. At least initially, Clark was out of his depth. The family had arrived in Kerikeri by way of Singapore where he had been an assistant marine superintendent for the Straits Steamship Company, the apex of a seafaring career begun in 1941 at the Thames Nautical Training College in Kent, scene of mute swans gliding across the estuary. Fourteen at the time, cadet Clark was already five years into what was to become a serious birdwatching habit.

In Kerikeri, while attempting to deal with mites and cottony cushion scale, Clark also kept his hand in. He took on skippering jobs and delivered ships and boats across the oceans to supplement the family income and to fund his odysseys. After taking boatbuilding lessons at night-school, he built Ketiga in 1968 and a couple of years later sailed the 7-metre engineless yacht in a singlehanded trans-Tasman race.

In 1972 Clark embarked on what he described as a “bird-watching voyage” in Ketiga — circumnavigating Aotearoa and taking in subantarctic islands, observing the loss of seabird breeding grounds and speculating that over-fishing, introduction of predators and other human interference were to blame. Citizen science duties aside,

Gerry Clark at the helm of Totorore somewhere in the treacherous Drake Passage, between Cape Horn and Antarctica, December 1983. NZMM 2017.40.473.

Photograph by Cowan, Alan. NZMM 2017.40.473

Hand-illustrated map of the route taken by Totorore (1983-1988), with locations of two dismastings, and five 360°rollings marked. NZMM 2017.40.1752

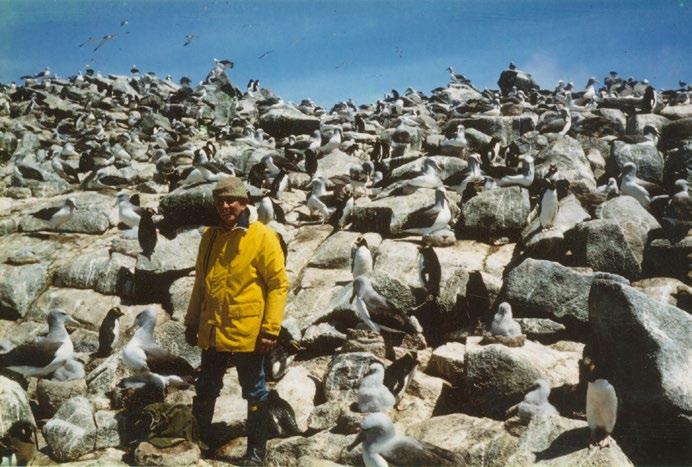

Gerry Clark in his element, on Bounty Island with erect-crested penguins (Eudyptes sclateri) and Salvin’s albatross (Thalassarche salvini), 1970s. NZMM 2017.40.283

Clark used the 3,000-plus mile voyage to raise funds for the Society for the Preservation of the Kerikeri Stone Store Area; members of the public sponsored Clark at 50 cents a mile. In Ketiga’s logbook Clark also recorded a deeper motivation for his offshore wanderings: “It is only at sea that I really feel at peace and in harmony with my surroundings. I love seabirds, the creatures in the sea, and the sea itself.”

Photograph of a light-mantled albatross (Phoebetria palpebrate) on the Auckland Islands, taken during Gerry Clark’s 1972/3 ‘bird-watching voyage’ on his homebuilt yacht Ketiga. 2017.40.4034

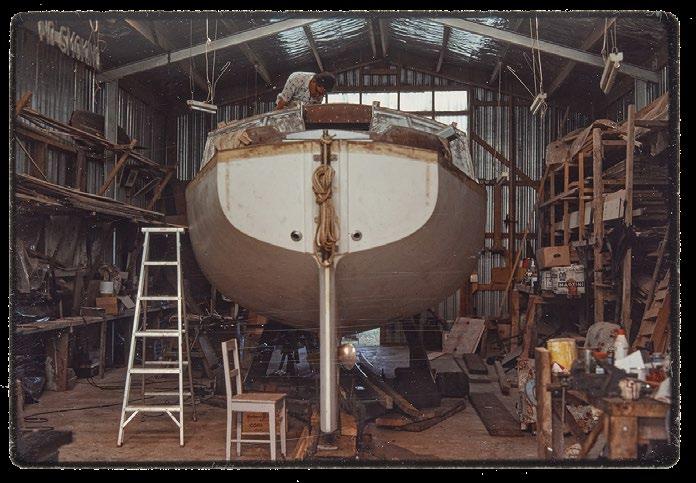

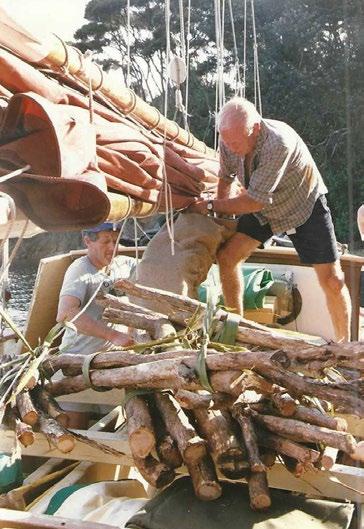

Back in Kerikeri Clark became highly focussed. He joined the Ornithological Society of New Zealand, as well as the Australasian Seabird Group. Then there was more boatbuilding — from 1975 and in the following seven years he upscaled Ketiga, constructing — “painfully slowly” he wrote — a 4-berth, 11-metre motorized kauri cutter with a draft of 1.4 metres and twin ballast keels for landing and resting on a beach or rock shelf in parts of the

ABOVE: Totorore under construction at the Clarks’ Homeland Orchard, circa 1980. NZMM 2017.40.2432

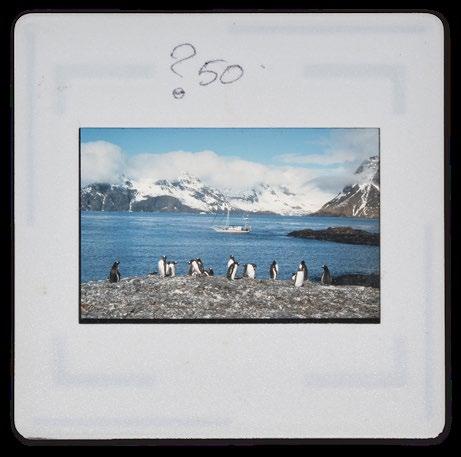

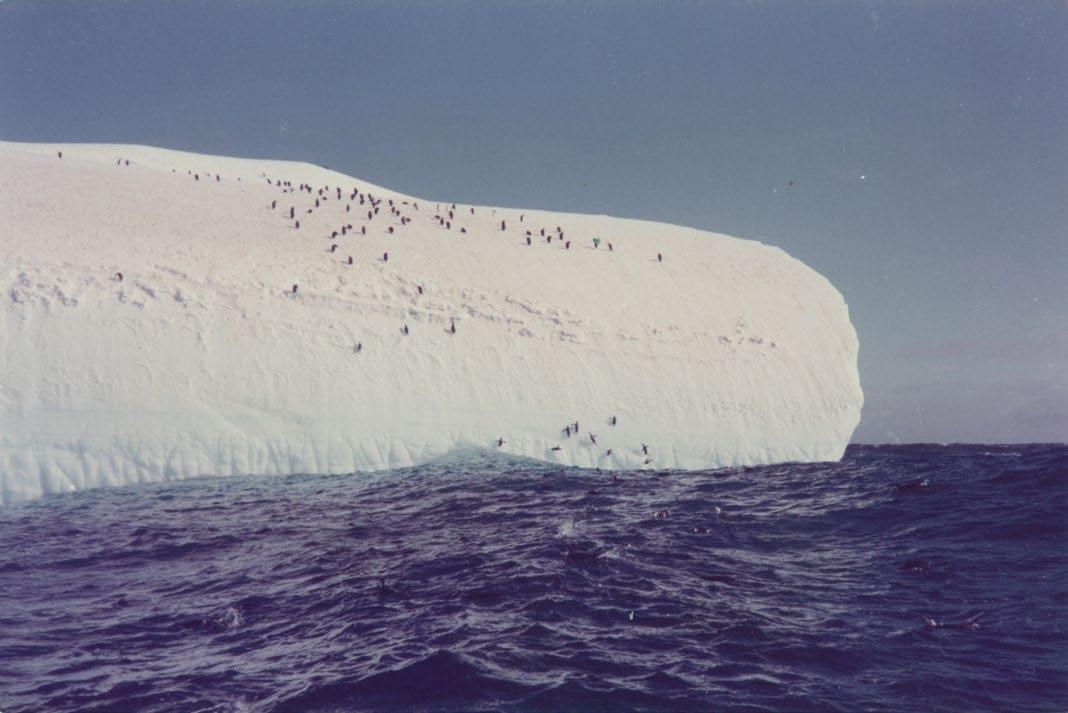

TOP SLIDE: A colony of chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarcticus) photographed from Totorore, near Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, 4 September 1985. NZMM 2017.40.728

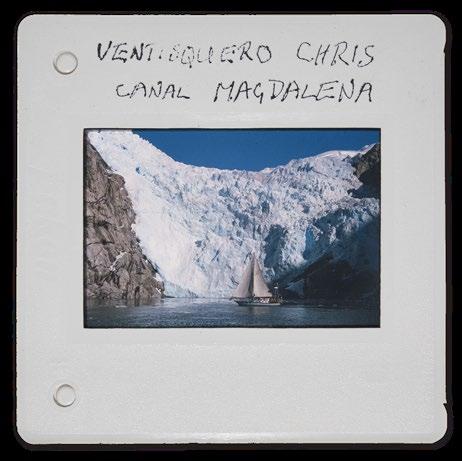

BOTTOM SLIDE: Totorore, Chile, 1984. NZMM 2017.40.2653

world where conditions routinely terrify.

He named his yacht Totorore after the abundant little bird (Antarctic prion/Pachyptila desolata) widely dispersed across the Southern Ocean, and often found storm-wrecked on the West Coast beaches of New Zealand’s South Island, come winter. ‘Totorore is built of wood, because I like wood,’ wrote Clark. ‘It is a natural substance which is pleasant to work with, and which up to a point I can understand. I can like a boat of steel, of aluminum, of fibreglass, or even of ferro-cement, but I do not like working with those materials which to my mind have no soul. Wood is different; I can love a good boat built of wood.’

Totorore motored down the Kerikeri Inlet on 26 February 1983, shortly after a vicar led a crowd in the singing of “For Those in Peril on the Sea”. Onboard were the 56-year-old Clark, two crew members (Ken Back and Squirrel Wright), and 50 vacuum-packed loaves of Vogel’s bread. The boat was Antarctica-bound via Chile on an expedition that was to take close to four years, the aim to assess the numbers and distribution of seabirds in order to inform conservation policies. Clark had developed a programme of work after seeking advice from ornithologists around the world. On the itinerary were the outer islands of the southern Chilean Archipelago and various subantarctic islands, since bird surveys of both regions were few and far between — largely because of the harsh, hair-curling environmental conditions. Experts approved: the expedition received the imprimatur of the International Council for Bird Preservation and the Ornithological Society of NZ . Although sometimes sailing alone, for much of the expedition Clark was assisted by one or two companions.

In all 26 sailors and ornithologists did voluntary stints on Totorore. Ideally when surveying bird habitats at least three crew were required, two to make landings and one to stay with the boat. Writing Clark’s obituary in 1999 ornithologist Mike Imber (gadfly petrels genus Pterodroma a specialty) noted master mariner Clark was often content to stay onboard Totorore ‘and keep her shipshape while others did the birdwatching, the major trips ashore, and if sufficiently well (for Totorore challenged almost every stomach) the cooking.’

But sometimes Clark headed to shore. His journal entries for April 1984 record trips in an inflatable dinghy from Totorore to Cape Horn, the rocky headland on Hornos Island in southern Chile’s Tierra del Fuego archipelago where the Pacific and Atlantic oceans converge and go extremely wild. Clark was on the dinghy with crew members Anthea Goodwin and Julia von Meyer— their mission to nab blue petrels (Halobaena caerulea). ‘Every landing and embarkation had been a worrying, uncomfortable, traumatic experience’, wrote Clark.

Once on the Island-proper things were similarly action-packed. After climbing a 406-metre cliff the threesome waved nets about and were in imminent danger of falling down the cliff. They were attempting to catch incoming petrels as they flew in from foraging trips way out on the ocean and headed to their burrows after sunset. In a tent hauled from Totorore Clark and co then went about their taxonomic work: ‘Back in the more friendly world of the tent…in the warming glow of the small hurricane lamp, we measured our blue petrel,’ Clark wrote. ‘A very pretty little bird...he was rather lively and bit Anthea vigorously, drawing blood. We then deloused him…and put him to bed in the sack in the porch of the tent, to await having his photograph taken in the morning.’

Clark and his crew were to make some of their most significant ornithological observations in southern Chile. Blue petrels aside, they documented breeding colonies of black-browed mollymawks (Thalassarche melanophris), thin-billed prions (Pachyptila belcheri), sooty shearwater, (Ardenna grisea) and rockhopper (Eudyptes chrysocome) and macaroni penguins (Eudyptes chrysolophus). Further south at South Georgia the expedition further ensured mention in journal articles and scientific studies for years to come by conducting accurate counts of wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans) and king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus) along the entire indented coastline of the 160km long subantarctic island as well as its satellite islands—a feat which occupied two winters.

Impressive accomplishments weren’t restricted to the birds. In a storm between Cape Town and Marion Island in the Indian Ocean Totorore lost its mast. Clark was sailing on alone with a jury rig when off Heard Island the boat rolled 360 degrees five times in seas with 35-metre waves. ‘I was soaked, frozen and battered, and in mortal terror of the next roll,’ he wrote. Only the thought of his family stopped him from stepping over the side and ending it all. He managed to keep Totorore afloat for another 68 days, drifting and sailing to the Australian coast near

and base for bird surveying atop Cape Horn, April

Gentoo penguins (Pygoscelis papua) photographed during the Totorore expedition at Bird Island, South Georgia, October 1984. NZMM 2017.40.3072

Fremantle, tarpaulin strapped between bipod masts made of spinnaker poles.

Clark eventually motored home and up Kerikeri Inlet on 7 November 1986. Not long after, he was asked by the journalist Brigit Manning of The Press what was so special about birds. ‘Hard to say,’ said Clark, rallying: ‘I just love birds. They’re fascinating, the orderliness of their lives, their grace of movement and freedom. They’re so beautiful, so much a part of the quality of life. I wouldn’t care to go to sea if there were no birds to look at. I never feel alone when there are birds. They’re always around down south.’ Manning still in need of convincing, asked Clark if the Totorore expedition was really just about the birds of the Southern Ocean. Wasn’t he also pitching himself against nature and other legendary explorers? ‘When you go down there, there’s nobody to watch,’ Clark replied. ‘It’s not a competitive thing. The way I sail, there’s no particular skill in it. I don’t know the finer points of sailing and they don’t particularly interest me. As long as I can get home safe, know where I’m going and get to the places I want to go, I’m quite happy.’

TOP LEFT: Totorore’s inflatable dinghy and crew member after a hairy landing on Cape Horn, 30 April 1984. NZMM 2021.43.70 Expedition campsite

1984. NZMM 2017.40.5360

In the next decade Clark kept up his conservation efforts, undertaking several voyages in Totorore assisting scientists count, map and study birds. On 11 June 1999 shortly after dropping two albatross researchers on Antipodes Island, and as gale force northerly conditions were about to hit, Clark radioed that Totorore was losing battery power. Clark and his companion Roger Sale were never heard from again, and only small pieces of Totorore’s wreckage have ever been found. This despite comprehensive searches of the island, its coast and of 70,000 squares miles of surrounding ocean, including by the ketch Ranui and an Air Force Orion. Such was the regard for the then 72-year-old Clark’s powers of survival that his whãnau found his loss unimaginable. Three weeks after all contact with Clark and Sales was lost, Majorie Clark was to tell the New Zealand Herald: ‘We are not a

LEFT: Gerry Clark refuelling at Bird Island. NZMM 2017.40.2248

RIGHT: Gerry Clark and Totorore’s homecoming, Kerikeri wharf, 7 November 1986. NZMM 2017.40.3865

bit worried about him. We think he won’t have a clue of what has been going on and will be rather distressed if he knew the trouble he is causing.’

Gerry Clark’s daughter Elsa donated her father’s archives to the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui o Tangaroa in 2017. The Gerry Clark Collection is now digitised. Go for a browse of the collection at https://collection.maritimemuseum.co.nz/explore

Frances Walsh is the inhouse writer/editor at the NZ Maritime Museum.

TOP: A colony of chinstrap penguins (Pygoscelis antarcticus) photographed from Totorore, near Sandwich Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, 4 September 1985. NZMM 2017.40.728

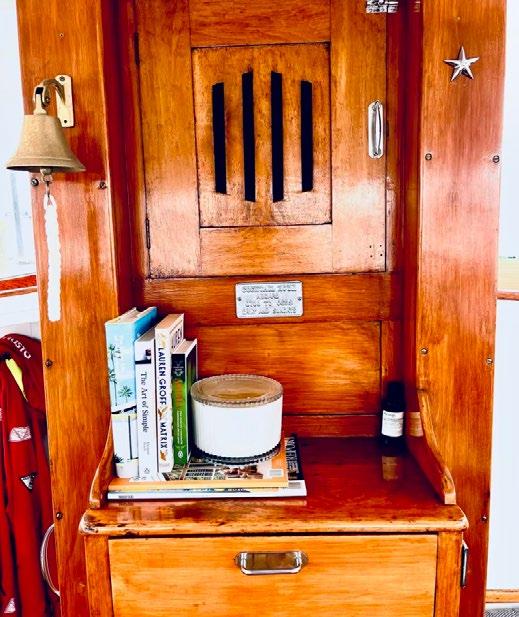

Tonnant Creation Crucifixion and Resurrection

Emigrating from Bulgaria, our family followed suit. We rebuilt and sailed a Guzzwell’s Trekka, runabouts, dinghies, a Stratus 747, Logan’s Gypsy (partially), and a Davidson 31 – Tonnant.