MOTION IN A PLANE CHAPTER 3

■ To describe a scalar quantity, we require

Chapter Outline

3.1 Scalars and Vectors

3.2 Multiplication of Vectors by Real Numbers

3.3 Addition and Subtraction of Vectors

3.4 Resolution of Vector

3.5 Vector Addition (Analytical Method)

3.6 Parallelogram and Triangle Law

3.7 Motion in a Plane

3.8 Motion in a Plane with Constant Acceleration

3.9 Relative Velocity in Two and Three Dimensions

3.10 Projectile Motion

3.11 Circular Motion

3.1 SCALARS AND VECTORS

■ All measurable quantities are called physical quantities. Most of the physical quantities are classified into scalars and vectors

■ Physical quantities having only magnitude are called scalars.

■ Examples: Length, time, volume, density, temperature, mass, work, energy, electric charge, electric current, potential, resistance, capacity, etc.

the specific unit of that quantity;

the number of times that unit is contained in that quantity,

■ Example: A bag contains 100 kg of sugar. Here, kg is the unit and 100 is the number of units of sugar present in the bag.

Key Insights:

■ Unit is not a compulsion to represent a scalar.

■ Example: Specific gravity, refractive index

■ Displacement, velocity, acceleration, force, momentum, angular momentum, moment of force, torque, magnetic moment, magnetic induction field, intensity of electric field, etc.

■ To describe a vector quantity, we require:

the specific unit of that quantity;

the number of times that unit is contained in that quantity;

the orientation of that quantity.

■ Example: A plane is flying from west to east with a velocity of 50 ms–1. Here, ms–1 is the unit, 50 is the number of units of velocity, and west to east is the direction.

Key Insights:

■ A physical quantity having magnitude and direction but not obeying laws of vector addition is treated as a scalar.

■ Example: Electric current is a scalar quantity.

■ Electric current is always associated with direction, but it is not a vector quantity. It does not obey the law of vector addition for its addition.

+ i2)

■ The resultant of i 1 and i 2 is ( i 1 + i 2 ) by Kirchoff’s current law. The resultant does not depend on the angle between currents i1 and i2.

■ Velocity of light and velocity of sound are also not vectors.

3.1.1

Position and Displacement Vectors

■ To describe the position of an object moving in a plane, we need to choose a convenient point, say O, as origin. OP is the position vector of the object at time t. An arrow is marked at the head of this line. It is represented by a symbol r, i.e., OP = r

3.1.2 Equality of Vectors

■ Two vectors, A and B, are said to be equal if and only if they represent the same physical quantity with same magnitude and the same direction.

Fig (a) Two equal vectors, A and B (b) Two vectors A’ and B’ are unequal though they are of the same length.

Key Insights:

■ Two or more vectors (representing the same physical quantity) are called equal if

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

their magnitudes and directions are same.

■ Example: Suppose two trains are running on parallel tracks with same speed and direction. Then, their velocity vectors are equal vectors.

■ If a vector is displaced parallel to itself, its magnitude and direction do not change.

3.1.3 Types of Vectors

■ Let us discuss the different types of vectors.

Polar Vector

■ The vector whose direction does not change even though the coordinate system in which it is defined changes is called polar vector or real vector. Direction of polar vector remains unchanged in its mirror image. Direction of polar vector does not depend on any convention; direction comes naturally and physically.

■ Examples: Force, momentum, acceleration.

Axial Vectors

■ Axial vectors are associated with rotational motion of objects. Its direction is determined by right hand thumb rule or rotation of right handed screw. In its mirror image, direction of axial vector is reversed. Direction of axial vector depends upon convention (right hand thumb rule).

■ Examples: Angular velocity, torque, angular mome-ntum

■ Like Vectors or Parallel Vectors: Two or more vectors (representing same physical quantity) are called like vectors if they are parallel to each other. However, their magnitudes may be different.

■ Unlike Vectors or Anti-parallel Vectors: Two vectors (representing same physical quantity) are called unlike vectors if they act in opposite directions. However, their magnitudes can be different.

■ Coplanar Vectors: A number of vectors are said to be coplanar if they are in the same plane or parallel to the same plane. However, their magnitudes may be different.

■ Negative Vector: A vector having the same magnitude and opposite direction to that of a given vector is called negative vector of the given vector.

■ Co-initial Vectors: The vectors having same initial point are called co-initial vectors.

■ Unit Vector: A vector whose magnitude equals one and is used to specify a convenient direction is called a unit vector.

■ A unit vector has no units and dimensions. Its purpose is to specify the direction of the given vector.

■ In Cartesian coordinate system, unit vectors along positive x, y, and z axes are symbolized as ˆˆˆ ,andk,ij respectively. These three unit vectors are mutually perpendicular and their magnitudes are equal to 1.

1. ===ijk

■ If A is a non-zero vector, then the unit vector in the direction of A is given by

■ Collinear Vectors: Two or more vectors are said to be collinear when they act along the same line. However, their magnitudes may be different.

■ Example: Two vectors A and B , as shown, are collinear vectors.

■ Null Vector or Zero Vector: A vector whose magnitude is equal to zero is called a null vector. Its origin coincides with terminus and its direction is indeterminate.

Examples of zero vector:

■ The velocity of a particle at rest.

■ The acceleration of a particle moving at uniform velocity.

■ The displacement of a stationary object over any arbitrary interval of time.

■ The position vector of a particle at the origin.

■ At the highest point of a vertically projected body, its velocity vector is a null vector.

Key Insights:

■ 0 +=

■ In our study, vectors do not have fixed locations. So, displacing a vector parallel to itself leaves the vector unchanged. Such vectors are called free vectors. However, in some physical applications, location or line of application of a vector is important. Such vectors are called localised vectors.

TEST YOURSELF

1. Of the following the scalar quantity is (1) Moment of force (2) Temperature (3) Magnetic moment (4) Moment of couple

2. A vector is not changed if (1) It is rotated through an arbitrary angle (2) It is multiplied by arbitrary scalar (3) It is cross multiplied by a unit vector (4) It is displaced parallel to itself

3. Among the following, the vector quantity is (1) Pressure

(2) Gravitation potential (3) Stress (4) Impulse

Answer Key (1) 2 (2) 4 (3) 4

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

3.2 MULTIPLICATION OF VECTORS BY REAL NUMBERS

■ Multiplying a vector A with a positive number λ gives a vector whose magnitude is changed by the factor λ but the direction is the same as that of A , if λ is positive.

■ The direction is opposite to that of A, if λ is negative.

■ For example, if A is multiplied by 2, the resultant vector 2A is in the same direction as A, and it has a magnitude twice of A , as shown in Fig. (a). A 2A

Fig. (a)

(a) Vector A and the resultant vector after multiplying A by a positive number 2

3.3 ADDITION AND SUBTRACTION OF VECTORS

■ The addition and subtraction of vectors involve combining or finding the difference between two or more vectors, respectively.

4.3.1 Representation of Angle between Two Vectors

■ The angle between two vectors is represented by the smaller of the two angles between the vectors when they are placed tail to tail by displacing either of the vectors parallel to itself.

■ Example: The angle between A and B is correctly represented in the following figures.

If the angle between A and B is θ, then the angle between A and K B is also θ, where ‘K’ is a positive constant.

If the angle between A and B is θ, then the angle between A and –K B is (180° – θ ), where K is a positive constant.

Now, we observe that the angle between A and B is 60°, B and C is 15°, and A and C is 75°.

Solved example

2. A man walks towards east with a certain velocity. A car is travelling along a road which is 30° west of north, while a bus is travellingt on another road which is 60° south of west. Find the angle between velocity vector of (a) man and car, (b) car and bus, and (c) bus and man.

Sol.

Angle between collinear vectors is always zero or 180°.

1. Three vectors ,, ABC are shown in the figure. Find the angle between (i) A and B (ii) B and C (iii) A and C

Sol. To find the angle between two vectors, we connect the tails of the two vectors. We can shift the vectors parallel to themselves, such that tails of ,B A and C are connected as shown in the figure.

From the diagram, the angle between velocity vector of man and car is 90° + 30° = 120°.

The angle between velocity vector of car and bus is 60° + 60° = 120°.

The angle between velocity vector of bus and man is 30° + 90° = 120°.

Try yourself:

1. A vector A makes an angle of 30° with the positive y-axis in anti-clockwise direction. Another vector B makes an angle of 30° with the positive x -axis in clockwise direction. Find the angle between vectors A and B . Ans: 150°

3.3.2 Addition of Vectors (Graphical Method)

■ When two vectors are acting in the same direction:

Let the two vectors P and Q be acting in the same direction.

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Associative law: Vector addition obeys associative law. While adding more than two vectors, the resultant is independent of the order in which they are added.

■ If ,and PQR are three vectors, then ( ) ( ) ,

PQRPQR as shown in the figure.

■ When two vectors are acting at some angle: First, join the initial point of Q with the final point of P and then, to find the resultant of these two, draw a vector R from the initial point of P to the final point of Q . This single vector R is the resultant of vectors P and Q .

R represents the resultant of P and Q both in magnitude and direction. So,

3.3.3

Laws of Vector Addition

■ There are three laws of vector addition.

Distributive law:

Vector addition obeys distributive law. If k, k1, k2 are scalars, then ( )

and ( ) 1212 +=+

Key Insights:

■ Vector addition is possible only between vectors of same kind.

■ What is the result of adding two equal and opposite vectors? Consider two vectors A and - A , shown in figure.

■ Their sum is ( ) +AA Since the magnitudes of the two vectors are the same, but the directions are opposite, the resultant vector has zero magnitude and is represented by 0 , called a null vector or a zero vector.

PQQP , as shown in the figure.

Commutative law: Vector addition obeys commutative law. Addition of two vectors is independent of the order of the vectors in which they are added. If P and Q are two vectors, then +=+

()0+-=AA

■ Since the magnitude of a null vector is zero, its direction cannot be specified.

■ The null vector also results when we multiply a vector A by the number zero. The main properties of null vector are 0;(0)0;0()0 +=λ== AAA

Application

■ Suppose, a person has 3 m displacement towards east and 4 m displacement towards north. In vector form, displacement towards east is ˆ 3i .

Displacement towards north is 4 j

■ Magnitude of displacement 22 345=+= S

■ Angle made by the vector with x -axis is 4 tan 3 θ=

3.3.5 Laws of Vector Subtraction

∴ Vector makes an angle tan14 3 -

with +x axis in anti-clockwise direction.

3.3.4 Subtraction of Vectors

■ The process of subtracting one vector from another is equivalent to adding vectorially the negative of the vector to be subtracted.

■ Let P and Q be the two vectors, as shown in the figure. We want to find the difference . -

PQ Let a vector Q be added to the vector P by the laws of vector addition. Their resultant gives the value of

■ The vector subtraction does not follow commutative law, i.e., ,but

The vector subtraction does not follow associative law, i.e.,

Vector subtraction follows distributive law. ()-=mPQmPmQ

TEST YOURSELF

1. The vector that is added to ( ) 5 ˆ 2 ijk -+ and ( ) 36 ˆ 7 ijk -+ to given a unit vector along x -axis is:

(1) ( ) 35 ˆ ijk -+

(2) ( ) 3

5 ijk ++

(3) ( ) 311

9 ijk-+-

(4) ( ) 36 ˆ 5 ijk +-

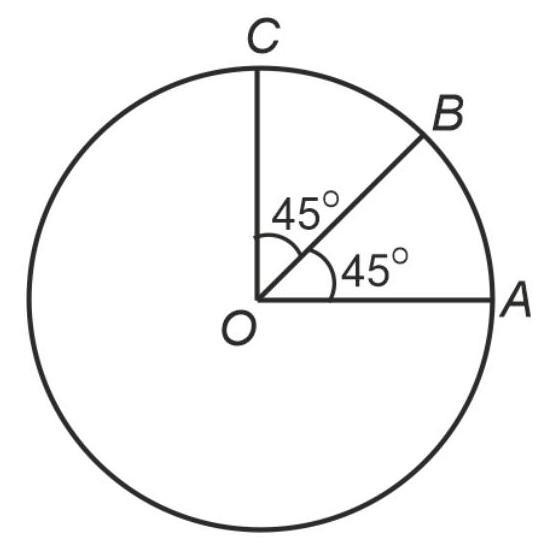

2. Find the resultant of three vectors OA,OB

and OC

shown in the following figure. Radius of the circle is R.

(1) 2 R (2) ( ) R12 + (3) R2 (4) ( )R21 -

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

3. The unit vector parallel to the resultant of the vectors 36 ˆ 4 Aijk =++ and B38 ˆ ijk=-+ is

(1) ( ) 1 362 7 ijk + (2) ( ) 1 362 7 ijk ++ (3) ( ) 1 362 49 ijk + (4) ( ) 1 362 49 ijk -+

4. Given two vectors A2 ˆ 3 ijk=- and B2 ˆ 46ijk=++

. The angle made by ( ) AB + with the Y -axis is (1) 0 (2) 45 (3) 60 (4) 90

5. A particle is moving such that its position co-ordinates ( ) , xy are ( ) 2m,3m at time t0,(6m = , 7m) at time t2s = and ( ) 13m,14m at time t5s = . Change in position vector of the particle from 0 t = to 5 ts = is

(1) ( ) 1314ij + (2) ( ) 7 ij + (3) ( ) 2 ij + (4) ( ) 11 ij +

6. The resultant of two forces 2 N and 3 N is 19N . The angle between the forces is (1) 30 (2) 45 (3) 60 (4) 90

7. The greatest and least resultant of two forces are 7 N and 3 N respectively. If each of the force is increased by 3 N and applied at 60°. The magnitude of the resultant is (1) 7 N (2) 3 N (3) 10 N (4) 129N

8. Four forces ,2,3 PPP and 4 P act along sides of a square taken in order. Their resultant is

(1) 22 P (2) 2 P (3) /2 P (4) Zero

9. There are two force vectors, one of 5N and other of 12 N . At what angle the two vectors be added to get resultant vector of 17,7NN and 13N respectively

(1) 0,180 and 90

(2) 0,90 and 180

(3) 0,90 and 90

(4) 180,0 and 90

10. Two forces whose magnitudes are in the ratio 5: 3 are acting at a point at an angle 60 simultaneously. If the resultant of the two forces is 35 N , then the magnitudes of two forces respectively are

(1) 3N,5N

(2) 25N,9N

(3) 25N,15N

(4) 12N,20N

Answer Key

(1) 3 (2) 2 (3) 1 (4) 4 (5) 4 (6) 3 (7) 4 (8) 1 (9) 1 (10) 3

3.4 RESOLUTION OF VECTOR

■ Resolution of a vector is the process of obtaining the component vectors which, when combined, according to laws of vector addition, produce the given vector.

3.4.1 Resolution of a Vector into Rectangular Components

■ Consider a vector r in the xy plane. It makes an angle θ with the x-axis, as shown in the figure. ˆ i and ˆ j are unit vectors along

the x-axis and y-axis, respectively. =+

OROPOQ ............ (1)

If OP = x and OQ = y, then and = = OPxiOQyj

From equation (1), =+ rxiyj ....... (2)

ˆˆ (cos)(sin) =θ+θ rrirj

From right-angled triangle OPR, 2222 or =+=+ OROPPRrxy

Solved example

3.Find the resultant of the vectors shown in the figure. O A B C x y 4cm 3cm 5cm 370

Sol. =++

ROAABBC ( ) ˆˆˆˆ 5cos375sin3734 Rijij =°+°++ ˆˆˆˆ 4334=+++ Rijij 77,72cmandRijR=+∴=

α = 45° with horizontal

Solved example

4. Find the resultant of the vectors ,,and, OAOBOC as shown in the figure. The radius of the circle is r. 450 450 A B C O

Sol. =++ ROAOBOC

ˆˆˆ cos45sin45 Rririrjrj =+°+°+

Try yourself:

2. A vector A makes an angle of 30° with the positive y-axis in anti-clockwise direction. Another vector B makes an angle of 30° with the positive x -axis in clockwise direction. Find the angle between vectors

A and B .

Key Insights:

Ans: 1F = 6 N, 2F = 10 N

■ Method involving resolution of vectors into components to find the resultant of the vectors is known as analytical method.

■ The components of a vector are independent of each other and can be handled separately.

■ Theoretically, a given vector can be made the diagonal of infinite number of parallelograms. Thus, there can be infinite number of ways to divide a vector into components.

Solved example

5. Vector A is 2 cm long and 60° above the x-axis in the first quadrant, and vector B is 2 cm long and 60° below the x-axis in the fourth quadrant. Find +

AB . Sol.

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Solved example

6. A vector has x component of –25.0 units and y component of 40.0 units. Find the magnitude and direction of the vector.

Sol. Consider a vector ˆˆ

= 47.16 47.2 units.

40.0 tan1.6 25.0 y x A A α===-∴ α = tan–1 (–1.6) = –58.0° with –ve x-axis. (This is in clockwise direction.) This is equivalent to (122°) in anti-clockwise direction with the x-axis.

Try yourself:

3. A vector P of magnitude 2 units makes an angle of 45° with x-axis. Find the vector.

Ans: ˆˆ 22 Pij =+

Application

■ A block is placed on a smooth horizontal surface and pulled by a force ‘F’, making an angle ‘ θ ’ with horizontal.

■ The component of force along horizontal = F cos θ

■ The component of force along vertical = F sin θ

■ A block of mass m is placed on an inclined plane of inclination angle θ . Then, the component of weight

parallel to the inclined plane is mg sin θ , and the component of weight perpendicular to the inclined plane is mgcos θ . x 22

Solved example

7. A vector ˆ 3 + ij rotates about its tail through an angle 30° in clockwise direction. What is the new vector?

Sol. The magnitude of ˆ 3 + ij is 31 + = 2. The angle made by the vector with x-axis is

■ A simple pendulum having a bob of mass m is suspended from a rigid support and it is pulled by a horizontal force F . The string makes an angle θ with the vertical, as shown in the figure.

■ The horizontal component of tension = T sin θ

■ The vertical component of tension = T cos θ

■ When the bob is in equilibrium, T sin θ = F, ........(1) T cos θ = mg ....... (2) cos22 == θTmgmgl lx

From equations (1) and (2),

( ) 22=+ TFmg

Key Insights:

■ If a vector is rotated through an angle other than integral multiple of 2 π (or 360°), it changes, but its magnitude does not change.

= 30°

When the given vector rotates 30° in clockwise direction its direction changes along x-axis but its magnitude does not change.

∴ The new vector is ˆ 2i O x y 2i

Try yourself:

4. A vector of magnitude a rotates through on angle of θ. Find the magnitude of its change.

Ans: 2sin 2 a θ

Key Insights:

■ If the frame of reference is rotated, the vector does not change (though its components may change).

3.4.2 Resolution of a Vector into Three Rectangular Components

■ Let us consider a vector A represented by

OP , as shown in the figure. With O as origin, construct a rectangular parallelopiped with three edges along the three rectangular axes which meet at O. A becomes the diagonal of the parallelopiped.

,

xy AA and z A are three vector intercepts along x, y, and z axes, respectively. These are the three rectangular components of A .

■ Applying triangle law of vectors, =+

OPOKKP .................... (1)

■ Applying parallelogram law of vectors,

From (1) and (2), OPOTOQKP =++

But , =∴=++

KPOSOPOTOQOS

,or, zxyxyz AAAAAAiAjAk ⇒=++=++

Again, OP2 = OK2 + KP2 = OQ2+OT2+KP2 or, A2 = A x 2 + A z 2+A y 2 [ KP = OS = Ay] or, 222=++ xyz AAAA

■ This gives the magnitude of A , in terms of the magnitudes of components ,,xy AA and

z A .

3.4.3 Direction Cosines

■ The direction cosines , m and n of a vector are the cosines of the angles α , β, and γ,

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

which a given vector makes with x -axis, y-axis, and z-axis, respectively.

k

■ α , β , γ are angles made by A with positive x-, positive y-, and positive z-axes respectively, then cosα, cosβ, cosγ are called direction cosines.

=cos=,=cos=,=cos= y xz A AA mn AAA∴αβγ

Squaring and adding cos2 α + cos2 β + cos2 γ = 2222 222 22222 1 ++ ++=== yxyzxz AAAA AAA AAAAA ⇒ cos2 α + cos2 β + cos2 γ = 1 and, sin2 α + sin2 β + sin2 γ = 2

TEST YOURSELF

1. A bird moves in such a way that it has a displacement of 12 m towards east, 5 m towards north and 9 m vertically upwards. The magnitude of its displacement is

(1) 52m

(2) 510m

(3) 55m

(4) 5 m

2. A vector 34ij + rotates about its tail through an angle 37 in anticlockwise direction then new vector is

(1) 5 i

(2) 5 j

(3) 3i4j(4) 34ij-+

3. The rectangular components of a vector lying in xy plane are ( )1 n + and 1 . If coordinate system is turned by 60 . They are n and 3 respectively the value of ‘ n ‘ (1) 2 (2) 3 (3) 2.5 (4) 3.5

4. If 34 ˆ 2 Aijk =-+ the magnitudes of its components in yz plane and zx plane are respectively (1) 13 and 5 (2) 5 and 25 (3) 25 and 13 (4) 13 and 29

Answer Key (1) 2 (2) 2 (3) 4 (4) 2

3.5 VECTOR ADDITION (ANALYTICAL METHOD)

■ Let us consider the addition of two vectors P and Q in terms of their components.

have

■ Let R be the resultant vector with component. R x and R y are the components along x and y axes, respectively. Then, ˆ = xx RRi and ˆ . = yy RRj

tan tan y x yy xx R R PQ PQ ∴α= + α= + tan1 yy xx PQ PQ+ ∴α= +

Solved example

8. Find the magnitude and direction of the resultant of the vectors ( ) ˆˆ , =+ aij ( ) ˆˆ 5 =+ bij and ( ) ˆˆ 2.cij =-

Sol. ( ) ˆˆ 34=++=+ Rabcij 22 34unit5units R ∴=+=

Direction, 14 tan53 3α==° with positive x-axis.

Try yourself:

From the diagram, R x =Px+Qx and R y =Py+Qy ( ) ( ) ˆˆ , ∴=+=+ xxxyyy RPQiRPQj ( ) ( ) ˆˆ ; ˆˆ xy xxyy RRiRj RPQiPQj ∴=+ =+++ ( ) ( ) 22 =+++ xxyy RPQPQ

5. A particle is moving eastwards with a velocity of 5 m/s. In 10 s, the velocity changes to 5 m/s Northwards. Find the average acceleration in this time.

Ans: 21directionNorth-westm/s; 2

3.6 PARALLELOGRAM AND TRIANGLE

LAW

■ There are different graphical methods of vector addition.

3.6.1 Parallelogram Law of Vectors

■ “ If two vectors are drawn from a point so as to represent the adjacent sides of a parallelogram, both in magnitude and the direction, the diagonal of the parallelogram

drawn from the same point represents the resultant of the two vectors, both in magnitude and direction.”

Special Cases

■ Let the two vectors P and Q , inclined at angle θ, be acting on a particle at the same time. Let them be represented in magnitude and direction by two adjacent sides OA and OB of parallelogram OACB, drawn from a point O.

■ According to the parallelogram law of vectors, their resultant vector R will be represented by the diagonal OC of the parallelogram.

■ Magnitude of resultant: 222cos =++θRPQPQ ........ (3)

■ Direction of resultant:

■ If the line of action of the vector P is taken as reference line, the resultant R makes an angle α with it. This angle indicates the direction of R Then, from right-angled triangle ONC, sin tan cos θ α=== ++θ CNCNQ ONOAANPQ ....(4)

Key Insights:

■ If β is the angle between the resultant R and the vector Q , then tan1sin cos P QP

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

■ If the magnitude of P > Q then α < β, i.e., the resultant is closer to the vector of the larger magnitude.

■ When the angle between two vectors increases, the magnitude of their resultant decreases.

■ When two vectors are in the same direction (parallel),

RPQ P Q

then θ = 0°, cos 0° = 1 and sin 0° = 0.

From eq.(3), 222(1)=++ RPQPQ

2 ()()=+=+PQPQ

from eq. (4), 0 tan0 (1) × α== + Q PQ or α = 0°.

■ Thus, for two vecto rs acting in the sa me dire-ction, the magnitude of the resultant vector is equal to the sum of the magnitudes of two vectors, and it acts along the direction of P and Q .

■ When two vectors are acting in opposite directions (antiparallel), RPQ P Q

then θ = 180°, cos 180° = –1 and sin 180° = 0.

From eq. (3), 222(1)=++-RPQPQ

2()=-PQ = (P – Q) or ( Q – P)

From eq. (4), 0 tan0 (1) × α== +Q PQ

or, α = 0° or 180°.

■ Thus, for two vectors acting in opposite dire-ctions, the magnitude of the resultant vector is equal to the difference of the magnitudes of the two vectors, and its direction is along the vector of the larger magnitude.

■ When two vectors are perpendicular to each other, θ = 90°, sin 90° = 1, and cos 90° = 0

Q P R

From eq. (3), 2222 2(0) =++=+ RPQPQPQ

From eq. (4), tan(1) (0) α== + QQ PQP

or, α = tan–1 Q P

■ If the resultant of two vectors is perpendicular to any one of the vectors, then the angle between the two vectors is greater than 90°.

■ The resultant vector is perpendicular to the vector having smaller magnitude.

We know,

sin tan cos θ α= +θ Q PQ

sin tan90 cos θ °= +θ Q PQ P + Q cos θ = 0

cosandθ= P Q

22 , =RQP

sin,cos,tan. φ=φ=φ= PRP QQR

The angle between P and Q is θ = 90° + φ

■ maxmaxmin minmaxmin and. + + = = RRR PQP RPQQRR

■ If magnitudes of P and Q are equal and the angle between them is θ , then their resultant is

222cos =++θRPQPQ

2222cos =++θRPPP [P = Q]

22 22cos, =+θRPP ( ) 2 21cos =+θRP

22 22cos,2cos 22 θθ = ∴= RPRP

and the resultant makes an angle ‘ α ’ with P

∴α== +θ+θ QP PQPP

sinsin tan coscos θθ

( ) 2 sinsin tan 1cos2cos/2 θθ α= = +θ θ P P 2 2sincos tan22tan 2cos/22 θθ θ

∴α= = θ

tantan, 2 θ

∴α= 2 θ ∴α=

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

If θ = 60°, then R = 3P and α = 30°.

If θ = 90°, then R = 2 P and α = 45°.

If θ = 120°, then R = P and α = 60°.

The unit vector parallel to the resultant of two vectors P and Q is ˆ + = +

PQ n PQ

Application

■ Magnitude of difference of two vectors:

Solved example

9.Two vectors A and B have precisely equal magnitudes. For the magnitude of + AB to be larger than the magnitude of AB by a factor n, what must be the angle between them?

Sol. += ABnAB ( ) 2cos2sin 22

The magnitude of PQ is 222cos =+-θ SPQPQ and tansin(180)sin

Key Insights:

■ If , PQ

∴=SP

2sin 2 θ

■ When two vectors P and Q have same magnitude and θ is the angle between them, the values of resultant and difference are as given in the following table.

Solved example

10. The resultant of two vectors A and B is perpendicular to A and equal to half of the magnitude of B . Find the angle between A and B .

Sol. Since R is perpendicular to A , the figure shows the three vectors ,Band AR . Angle between A and B is ( π – θ ).

⇒ θ = 30° ⇒ Angle between A and B is 150°.

Try yourself:

6. The resultant of two forces whose magnitudes are in the ratio 3: 5 is 28 N. If the angle of their inclination is 60°, then find the magnitude of each force.

Ans: 20 N, 35 N

Application

■ If iv is initial velocity of a particle and vf is its final velocity, then change in its velocity is given by ∆= fi vvv

222cos ∆=+-θ ifif vvvvv

where ‘ θ ’ is the angle between initial and final velocities.

■ When a particle is performing uniform circular motion with a constant speed V, the magnitude of change in velocity when it describes an angle θ at the centre is

∆=

2sin. 2 VV

■ If velocity of a particle changes from iv to vf in time t, then the acceleration of the particle is given by .= fi vv a t

■ and PQ are two sides and and RS are two diagonals of a parallelogram. Then, 22222()+=+ RSPQ =+

RPQ

Q

R and RS

Q -

Q

Q

and RS

Magnitude of R :

222cos =++θRPQPQ

2222cos......(1) =++θRPQPQ

SPQ

=-

Magnitude of S : 222cos() =++π-θ SPQPQ

2222cos........(2) =+-θSPQPQ

From (1) and (2), 22222()+=+ RSPQ

Key Insights:

■ We can add a vector to another vector of same kind but we cannot add a vector quantity to a scalar quantity.

3.6.2 Triangle Law of Vectors

■ “If two vectors are represented in magnitude and direction by the two sides of a triangle taken in one order, their resultant vector is represented in magnitude and direction by the third side of the triangle taken in reverse order.”

A B N O θ α γ R Q P

∴=+ RPQ

Magnitude of resultant R : 222cos =++θRPQPQ

Direction of resultant R : sin tan. cos θ α= +θ Q PQ

■ Statement of triangle law when three forces keep a particle in equilibrium: When three forces acting at a point can keep a particle in equilibrium, the three

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

forces can be represented as the sides of a triangle taken in order, both in magnitude and direction.

3.6.3 Polygon Law of Vectors

■ “If a number of vectors are represented by the sides of a polygon, both in magnitude and direction, taken in order, their resultant is represented by the closing side of the polygon taken in reverse order in magnitude and direction.”

Solved example

11. ABCDEF is a regular hexagon with point O as the centre. Find the value of

Key Insights:

■ Let be x is the side of a regular hexagon ABCDEF, as shown in figure.

Then,

AB = x, AC = 3 x , AD = 2x, AE = 3 x , AF

Sol. From the diagram, ( ) ( ) ; ABDEBCEF =-=-

Try yourself:

7. Magnitude of three vectors ,,and PQR are 4, 3, and 5, respectively. If +0,PQR+= find the angle between and. PR Ans: 143°

3.6.4 Equilibriant

■ A vector having same magnitude and opposite direction to that of the resultant of a number of vectors is called the equilibriant. (or)

■ Negative vector of the resultant of a number of vectors is called the equilibriant (). E

■ If 123 ,and FFF are the three forces acting on a body, then their resultant force is 123=++

R FFFF ( ) ,123.∴=-=-++

R EFEFFF

Key Insights:

■ Single force cannot keep the particle in equilibrium.

■ The minimum number of equal coplanar forces required to keep the particle in equilibrium is two

■ The minimum number of unequal coplanar forces required to keep the particle in equilibrium is three

■ The minimum number of equal or unequal non-coplanar forces required to keep the particle in equilibrium is four

Application

■ Lami’s theorem: “If three coplanar forces acting at a point keep it in equilibrium, then each force is proportional to the sine of the angle between the other two forces.”

■ F1, F2, F 3 are the magnitudes of three forces and α , β , γ are the angles between forces 2

F and 3,

and

F , and 1

F and 2

F , respectively, as shown in fig. Then, according to Lami’s theorem,

12. In the given figure, the tension in the string OB is 30 N. Find the weight W and the tension in the string OA

Sol. Let T1 and T2 be the tensions in the strings OA and OB, respectively.

According to Lami’s theorem,

(T2 = 30 N)

On solving, 303 W = N and T1= 60 N

Try yourself:

8. A block of mass 2 kg is suspended by two strings strings 1 and 2, as shown in figue. Find the tensions in the strings. Take g = 10 m/s2

3.7 MOTION IN A PLANE

■ In this section, we shall see how to describe motion in two dimensions, by using vectors.

3.7.1

Position Vector and Displacement

■ Position vector of any point, with respect to an arbitrarily chosen origin, is defined as the vector which connects the origin and the point, and it is directed towards the point.

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

■ If ‘O’ is the origin, then OP is called the position vector (),rrxiyjzk =++

Magnitude of r is 222=++ rxyz

The unit vector along r is given by 222 ˆˆˆ ˆ ++ == ++ rrxiyjzk rxyz

■ Displacement Vector:

A s (x2, y2, z2) (x1, y1, z1)

■ If 1 r is the initial position vector of the particle and 2 r is the final position vector of the particle, then the displacement vector of the particle is given by 21 . =srr ( ) ( ) ( ) 212121 ˆˆˆ =-+-+ sxxiyyjzzk

■ The magnitude of the displacement vector is ( ) ( ) ( ) 222 212121 ==-+-+ SABxxyyzz

Solved example

13. A (2, 0) and B (0, 2) are two points and C is the midpoint of the line AB. Find the position vector of C

Sol. Coordinates of C are ( ) 2002 ,i.e.,1,1. 22 ++

Therefore, ( ) 1.1.. c rijij =+=+

Try yourself:

9. A particle moves from point A (2, 3) to point B(5, 7). Find the unit vector along its displacement.

Ans: 34 55ij

3.7.2 Velocity

■ The average velocity () v of an object is the ratio of the displacement and the corresponding time interval.

■ Since r v t ∆ = ∆ , the direction of the average velocity is the s ame as that of ∆ r T he velocity (instantaneous velocity) is given by the limiting value of the average velocity as the time interval approaches zero.

Application

■ Condition for collision: Consider that two particles, 1 and 2, move with constant velocities 1 v and 2 v . At initial moment ( t = 0), their position vectors are 1 r and 2 r .

■ If the particles then collide at the point P after time ‘t’ seconds.

From the diagram, x y 1 2 P O r1 r2 r 11 svt 22 svt

rrvvt ... (1) or, 1221 -=-

rr t vv

Substitute t in equation (1).

Therefore, ( ) 21 vv is parallel to ( ) 12 -

3.7.3 Acceleration

■ The average acceleration a of an object for a time interval ∆ t moving in x-y plane, is the change in velocity divided by the time interval:

vectors may have any angle between 0° and 180° between them.

Solved example

14. The position of a particle is given by 2 ˆˆˆ 3.02.05.0=++ rtitjk , where t is in seconds and the coefficients have the proper units for r to be in metres. (a) Find v ( t ) and a ( t ) of the particle. (b) Find the magnitude and direction of v ( t ) at t = 1.0 s.

Sol. 2 ()(3.02.05.0) drd vttitjk dtdt ==++

■ In terms of x and y , a x and a y can be expressed as

■ Acceleration, xy aaiaj =+

■ The instantaneous acceleration is the limiting value of the average acceleration, as the time interval approaches zero:

Since , xy vvivj∆=∆+∆

0

we have

(or) , xy aaiaj =+

where , xy xy dvdv aa dtdt ==

Key Insights:

■ In one dimension, the velocity and the acceleration of an object are always along the same straight line (either in the same direction or in the opposite direction).

■ However, for motion in two or three dimensions, velocity and acceleration

ˆˆ 3.04.0=+itj ˆ ()4.0 ==+ dv atj dt a = 4.0 m s–2 along y-direction (b) At t = 1.0 s, ˆˆ 3.04.0 vij =+ Its magnitude is 221 345.0ms=+= v and direction is 114 tantan53 3

y x v v with x-axis.

Try yourself:

10. A particle moves from position A(1, 2) to point B(4, 5) following a curved line in 3 seconds. Find the vector expression for the average velocity of the particle.

Ans: ( ) ij +

3.7.4 Kinematical Equations of Motion of a Particle Moving along a Straight Line with Uniform Acceleration

■ Consider a particle with initial position i x S uppose, it starts with initial velocity u and moves with uniform acceleration a , and v is its final velocity after t seconds with f x as the final position.

■ Now, the equations of motion are as follows.

Velocity as a function of time: vuat =+ (or) v = u + at

Displacement as a function of time: 2211 (or) 22 =-=+=+

Position as a function of time: 2211 (or) 22fifi xxutatxxutat =++=++

Velocity as a function of displacement: ..2. -=

vvuuas (or) v2 – u2 = 2as

Displacement in nth second of motion: 11 (or) 22nn SuanSuan

Displacement = (Average velocity) time: and 22

3.8 MOTION IN A PLANE WITH CONSTANT ACCELERATION

■ Suppose, an object is moving in x–y plane and its acceleration a is constant over an interval of time, and the average acceleration will be equal to this constant value. Now, let the velocity of the object be 0 v at time t = 0 and v at time t By definition, 00 0 0 or, vvvv a tt vvat ===+

■ In terms of components: v x = v ox + a x t

v y = v oy + a y t

■ Let us now find how the position r changes with time. We follow the method used in

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

the one dimensional case. Let 0r and r be the position vectors of the particle at time 0 and t and let the velocities at these instants be 0 v and v .

■ The average velocity over this time interval t is ( 0 v + v )/2 . The displacement is the product of the average velocity and the time interval:

■ It can be easily verified that the derivative of the above equation, i.e., dr dt , gives the equation for velocity and it also satisfies the condition that at t = 0, r = 0r . The equation for position vector can be written in component form as:

2 00 1 2 =++ xx xxutat

2 00 1 2 =++ yy yyutat

■ The motion in x-and y-directions can be treated independently of each other. Time is common to both horizontal and vertical motions.

Key Insights:

■ The motion in a plane (two-dimensions) can be treated as two separate simultaneous one-dimensional motions with constant acceleration along two perpendicular directions.

■ If an object is moving in a plane with constant acceleration 22 xy aaaa ==+ and its position vector at time t = 0 is 0r

then at any other time t, it will be at a point given by:

2

00 1 ; 2 rrvtat =++ and its velocity is given by:

0 vvat =+ , where 0 v is the velocity at time t = 0.

■ In component form:

■ Motion in a plane can be treated as superposition of two separate simultaneous one-dimensional motions along two perpendicular directions.

Application

■ A frictionless wire is fixed between A and B inside a sphere of radius R. A small ball slips along the wire. Find the time taken by the ball to slip from A to B.

2 ∴= R t g

The time is independent of the inclination of the wire.

Solved example

15. The coordinates of a body moving in a plane at any instant of time t are x = α t2 and y = β t2. The velocity of the body is

Sol. 22 =α⇒==α x dx xtvt dt 22 =β⇒==β y dy ytvt dt

( ) ( ) Velocity,2222 22 ∴=+⇒α+β xy vvvtt

222 =α+β t

Solved example

16. A particle starts from origin at t = 0 with a velocity ˆ 5.0m/s i and moves in x–y plane under action of a force which produces a constant acceleration of ( ) ˆˆ 3.02.0 + ij m/s2

(a) What is the y-coordinate of the particle at the instant its x-coordinate is 84 m?

(b) What is the speed of the particle at this time?

Sol. The position of the particle is given by 2 0 ()1 2 =+ rtvtat ( ) ( ) ˆˆˆ25.01/23.02.0 =++itijt

( ) 22ˆ ˆ 5.01.51.0=++ttitj

Therefore, x(t) = 5.0t + 1.5t2; y(t) = +1.0t2

Given: x(t) = 84 m; t = ?

5.0t + 1.5t2 = 84 ⇒ t = 6 s

At t = 6 s, y = 1.0 (6)2 = 36.0 m

Now, the velocity ( ) ˆˆ 5.03.02.0==++ dr vtitj dt

At t = 6 s, ˆˆ 23.012.0 vij =+ Speed 221 231226ms - ==+= v

Try yourself:

11. Velocity and acceleration of a particle at time t = 0 are ( ) ˆˆ 23m/s=+ uij and ( ) ˆˆ2 42m/s,=+ aij respe ctively. Find the velocity and displacement of the particle at t = 2 s.

Displacement = ( ) ˆˆ 1210 + ij m

Ans: Velocity = ( ) ˆˆ 107 + ij m/s

3.9 RELATIVE VELOCITY IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS

■ Graphical and analytical methods of finding velocity of one moving object relative to another moving object are explained below.

3.9.1 Relative Velocity in Two Dimensions

■ When we consider the motion of a particle, we assume a fixed point relative to which the given particle is in motion. For example, if we say that water is flowing or wind is blowing or a person is running with a speed ‘ v’, we mean that these are relative to the earth (which we have assumed to be fixed).

Key Insights:

■ If A v and B v are velocities of two bodies A and B relative to earth, then the velocity of A relative to B is = ABAB vvv .

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

If two bodies are moving along the same line in the same direction with velocities vA and vB relative to earth, then the magnitude of velocity of A relative to B is given by

vAB = vA – vB .

■ If vAB is positive, the direction of vAB is that of A and if negative, the direction of vAB is opposite to that of A or along the direction of B.

■ If two bodies are moving towards each other (or, away from each other) with velocities v A and v B, then the magnitude of velocity of A relative to B is given by vAB = vA – (–vB ) = vA + vB and directed towards A (or, away from A)

■ If two bodies A and B are moving with velocities v A and v B in mutually perpendicular directions, then the magnitude of velocity of A relative to B is given by 22=+ ABAB vvv

■ The direction of vAB with vA is tan. B A v v α=

■ If two bodies A and B are moving with velocities A v and B v , and θ is the angle between the velocities, then the magnitude of velocity of A relative to B is given by 222cos,ABABAB vvvvv=+-θ and the direction of v AB with v A is given by ( ) ( ) sin180 tan cos180 B AB v vv °-θ α= +°-θ sin cos B AB v vv θ = -θ

Differentiating equation (1) with respect to time, ( ) ( ) ( ) ′′ = PSPSSS ddd vvv dtdtdt

'' PSPSSSaaa∴=-

............. (2)

■ If two bodies A and B are moving with accelerations and ABaa , with respect to ground, the acceleration of A relative to B is = ABAB aaa 222cos,ABABAB aaaaa=+-θ

Where θ is the angle between A a and B a

Application

■ Relative motion on a moving train: If a boy is running with velocity BTV relative to a train, and train is moving with velocity

TGV relative to the ground, then the velocity of the boy relative to the ground BGV will be given by: =+ BGBTTGVVV

So, if the boy is running along the direction of the train,

VBG = VBT + VTG

■ If the boy is running on the train in a direction opposite to the motion of the train, then

VBG = VBT – VTG

Solved example

17. An object A is moving with 5 m/s and B is moving with 20 m/s in the same direction (positive x-axis). Find a) velocity of B relative to A; b) velocity of A relative to B.

Sol. a)

ˆˆ 20m/s;5m/s; = = BA ViVi

ˆ 15m/s BABA VVVi =-= b)

ˆˆ 20m/s,5m/s; = = BA ViVi

ˆ 15m/s=-= ABAB VVVi

Solved example

18. Ship A is 10 km due west of ship B. Ship A is heading directly north at a speed of 30 kmph, while ship B is heading in a direction 60° west of north at a speed of 20 kmph. Find their

closest distance of approach and the time taken for the closest approach.

Sol: 30,20sin60()20cos60()AB VjVij ==°-+°

10310 B Vij

If φ is the angle made by BAV with x-axis, then 202 tan 1033 φ== and 2 sin 7 φ= From 2 ; 107 ∆= x ABC 20 7 = x = 7.56 km Time10cos10(3/7)3hr 7007

Try yourself:

12. Two objects A and B, are moving, each with a velocity of 10 m/s. A is moving towards East and B is moving towards North from the same point, as shown. Find the velocity of A relative to B () ABV

Ans: 1102SEalongms -

3.9.3 Motion of a Boat across a River

■ When considering the motion of a body across a river, one must account for both the velocity of the body relative to the water and the velocity of the river current. By employing vector addition, the resultant velocity of the body with respect to the riverbank can be determined.

■ To cross the river over the shortest distance:

■ Suppose a boat starts from a point ‘A’ on one bank of the river of width ‘d’. To cross the river over the shortest distance, the boat should move by making an angle θ with the normal to the flow of water, as shown in the above figure.

■ Let VWG be the velocity of the water with respect to ground and VBW be the velocity of boat in still water or velocity of boat relative to water.

■ ∴ Velocity of boat with respect to ground is given by =+

BGBWWGVVV

∴ From the triangle ABC, 22 =BGBWWGVVV ........(1) and cos θ= BG BW V V ........(2)

sin θ= WG BW V V ........(3)

■ To cross the river at the shortest path, the angle made by the velocity of the boat with the flow of water is 90° + θ = 90° + sin–1

WG BW V V

■ The component of velocity of the boat normal to the flow of water is = VBW cos θ

■ The time taken for the boat to cross the river is cos = θ BW d t V ......... (4)

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

(5) [from (1)]

■ Shortest time: To cross the river in the shortest time, the boat should be rowed along the normal to the flow of water or by making an angle of 90° with the flow of water. d

■ The minimum time taken to cross the river is min = BW d t V .......(5) [from (4), θ = 0]

■ The velocity of the boat with respect to ground is 22=+ BGBWWGVVV .......(6)

■ In this case, the boat reaches the other bank at point ‘C’, due to the flow of water.

■ The displacement of the boat along the direction of flow of water or drift is given by x = VWG (tmin), () = WG BW d xV V .... (7)

■ The displacement of the boat is 22=+ sdx

Key Insights:

■ The time can be obtained by dividing the distance in a particular direction by velocity in that direction. === BWWGBG ABBCAC t VVV

■ Suppose the boat starts at point ‘A’ on one bank with velocity VBW and reaches the other bank at point ‘D’, as shown in the diagram.

Vsin

■ The component of velocity of boat parallel to the flow of water is sin. VBW θ

■ The component of velocity of the boat normal to the flow of water is of VBW cos θ

■ ∴ The time taken for the boat to cross the river is cos BW d t V = θ

■ The horizontal displacement of the boat (or) drift is ( ) sin =-θ WGBW xVVt ( ) sin cos WGBW BW d xVV V =-θ θ

■ If V WG > V BW sin θ , the boat reaches the other end of the river to the right of B.

■ If V WG < V BW sin θ , the boat reaches the other end of the river to the left of B.

■ If VWG = VBW sin θ, the boat reaches exactly the opposite point on the other bank, i.e, at B.

Solved example

19. A boat is moving with a velocity VBW = 5 km/ hr relative to water. At time t = 0, the boat passes through a piece of cork floating in water, while moving downstream. If it turns back at time t1 = 30 min,

a) when does the boat meet the cork again?

b) Find the distance travelled by the boat during this time.

Sol. t = 0

Consider an observer attached to the cork. The boat has the same speed upstream and downstream, relative to the cork. Hence, if the boat travels for 30 minutes while moving away from the cork, it travels for the same time while approching the cork.

Therefore, the boat meets the cork at T = 2t = 60 min. = 1h

The distance travelled by the boat in this time is: S = VBW × T = 5 × 1 = 5 km

Solved example

20. Two persons P and Q cross the river, starting from point A on one side to point B on the other side of the river exactly opposite to point A.The person P crosses the river at the shortest path. The person Q crosses the river in shortest time and walks back to point B. Velocity of river is 3 kmph and speed of each boat is 5 kmph w.r.t river. If the two persons reach the point B at the same time, then what is the speed of Q’s walking?

Sol. For person (P): For person (Q):

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

, 5 == Q B dd t V tP = tQ + ∆ t , 45 =+ man ddx V But = W B d xV V , 45 =+ W Bman ddVd VV ( ) 3 455 =+ man ddd V

113 , 455 -= man V 13 205 = man V

( ) ( ) 320 512kmph== man V

Try yourself:

13. A swimmer crosses a flowing stream of width ‘d’ to-and-fro in time t1. The time taken to cover the same distance up and down the stream is t 2. If t 3 is the time the swimmer would take to swim a distance 2 d in still water, then what is the relation between t1, t2 and t3 Ans: 123 ttt =

3.9.4 A Man in Rain

■ The magnitude of velocity of rain relative to man is 22=+ RMRM VVV

■ If α is the angle made by the umbrella with the horizontal, then

α= α= RRM MRMRM VVV VVV

■ If β is the angle made by the umbrella with the vertical, then

tan(or)sin(or)cos β= β= β= MMR RRMRM VVV VVV

■ Let us consider that rain is falling with a velocity

RV and a man moves with a velocity

MV relative to ground. He will observe the rain falling with a velocity . =-

VVV Since VR is assumed as a constant (for the rain falling at a constant rate), the man will record different velocities of the rain if he moves with different velocities relative to ground.

■ He should hold the umbrella against the direction of velocity of rain relative to man () RMV .

■ If rain is falling vertically with a velocity

VR and an observer is moving horizontally with velocity MV , the velocity of rain relative to the observer will be:

When the man is moving with a velocity 1MV relative to ground towards East, and the rain is falling with a velocity VR relative to ground by making an angle θ with the vertical, then the velocity of rain relative to man 1RMV is as shown in the figure.

From the diagram, tan θ= x y ......... (1) and tan1β= M xv y .......... (2)

If the man speeds up, at a particular velocity 2 VM , the rain will appear to

fall vertically with 22, =-

VRM2 VR VM2 VM2VRM2

RMRMVVV as shown in the figure. VM2

If the man increases his speed further to 3MV he will see the rain falling with a velocity 3RMV as shown in the figure. VRM3 VM3 x y

(where x and y are components of velocity of rain RV in horiz ontal and vertical directions respectively).

■ From the above three cases, we understand that sometimes, the man observes the rain falling forwards, sometimes vertically downwards, and sometimes, the rain appears to fall backwards. Hence, the velocity of rain relative to man depends upon the velocity of man relative to ground.

Solved example

21. Rain is falling vertically with a speed of 20 ms–1. A person is running in the rain with a velocity of 5 ms–1 and a wind is also blowing with a speed of 15 ms–1 (both from the West). What is the angle with the vertical at which the person should hold his umbrella so that he may not get drenched?

Sol.

Resultant velocity of rain and wind =

20K

10i Vertical

Now, Velocity of Rain relative to man = RMRGM VVV =-

ˆˆˆ (2015)(5)=-+-kii

ˆˆ 2010=-+ki

1 11 tantan 22α=⇒α=

Solved example

22. Rain is falling vertically with a speed of 35 ms–1. Winds start blowing after sometime with a speed of 12 ms –1 in East to West direction. In which direction should a boy waiting at a bus stop hold his umbrella?

Sol. The velocity of the rain and wind are represented by the vectors and rw VV in the figure and are in the direction specified by the problem. Using the rule of vector addition. We see that the resultant of and rw VV is R , as shown in the figure. The magnitude of R is

222211 3512ms37ms=+=+= rw Rvv

The direction θ that R makes with the vertical is given by 12

tan0.343 35 θ=== w r v v or, θ = tan–1 (0.343) = 19°

Therefore, the boy should hold his umbrella in the vertical plane at an angle of about 19°, with the vertical towards the East.

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Try yourself:

14. To a man walking at the rate of 3 kmph, the rain appears to fall vertically. When he increases his speed to 6 kmph it appears to meet him at an angle of 45° with the vertical. Find the angle made by the velocity of rain with the vertical and its value.

Ans: kmph3245, °

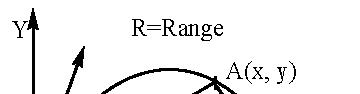

3.10 PROJECTILE MOTION

■ Any body projected into the air at an angle other than 90° with the horizontal near the surface of the earth, is called a projectile.

■ The science of projectile motion is called ballistics.

■ Examples: A cricket ball thrown by a fielder

A bullet fired from a gun

A javelin thrown by an athlete

A jet of water from a rubber tube impelled into the air

3.10.1 The Trajectory of Projectile

■ Let a body be projected at ‘O’ with an initial velocity u that makes an angle θ with the x-axis.

Since horizontal acceleation is zero, x = u x t = (u cos θ )t ........(1)

■ Now, let us consider the vertical motion. In vertical direction, the acceleration of the projectile is equal to the free fall acceleration which is constant and always directed downward ˆ =agj i.e., a y = –g

■ The equation for vertical displacement of the projectile after time t can be written by 12 2 =+ yy yutat , we get (sin)12()......(2) 2 =θ-= y yutgtag

This velocity can be written as ( ) ( )

cossin

uuiujuiuj .

■ Due to the fact that two dimensional motion can be treated as two independent rectilinear motions, the projectile motion can be broken up into two separate straight line motions:

Horizontal motion with zero acceleration [i.e., constant velocity, as there is no force in horizontal direction]

Vertical motion with constant downward acceleration = g ( It is moving under gravity)

■ By substituting the value of ‘ t’ from (1) as , cos = θ x t u in equation (2), 2 1 sin cos2cos =θ-

xx yug uu ( ) 2 22 tan 2cos ∴=θ- θ g yxx u

■ The values of g, θ and u are constants. The above equation is in the form y = ax – bx2 where a = tan θ; 222cos = θ bg u

■ This is the equation of a para bola. So, the path of the projectile is a parabola.

Solved example

23. A particle is projected from the origin in the x–y plane. Acceleration of particle in y direction is α . If equation of path of the particle is y = ax – bx2, then find the initial velocity of the particle.

Sol. y = ax – bx2

Try yourself:

15. An enemy plane is flying horizontally at an altitude of 2 km with a speed of 300 ms–1. An army man with an anti-aircraft gun on the ground sights an enemy plane when it is directly overhead and fires a shell with a muzzle speed of 600 ms–1. At what angle with the vertical should the gun be fired so as to hit the plane?

Ans: 30°

3.10.2 Motion Parameters of a Projectile

■ The motion parameters of a projectile, including time of flight, maximum height, and range, are crucial aspects that characterize its trajectory and motion dynamics.

Time of Ascent (t a)

■ For a projectile the time to reach maximum height is called time of ascent.

■ For a projectile, the vertical component of velocity v y is zero at the highest point.

v y = u sin θ – gt, Here, v y = 0 and t = t a

Time of Flight (T)

■ F or a projectile, the total time to reach the same horizontal plane of projection is called the time of flight. It is the total time for which the projectile remains in air. (sin)12 2 =θyutgt ; Here, t = T, y = 0 2 120(sin)2sin 2 θ

Key Insights:

■ Time of descent = timeofflight 2 = time of ascent

Solved example

24. A particle is projected with a velocity of 102 m/s at an angle of 45° with the horizontal. Find the interval between the moments when speed is 125m/s . (g = 10 m/s2)

Sol. u x = 10 m/s, u y = 10 m/s, v x = 10 m/s t S 222 =+ xy vvv 1251002 y v ⇒=+ v y = 5 m/s 225 1s 10 × ∆=== y v t g

Try yourself:

16. A golfer standing on the ground hits a ball with a velocity of 52 m/s at an angle θ above the horizontal if 5 tan. 12 θ= Find the time for which the ball is at least 15 m above the ground? (g = 10m/s2)

Ans: ∆ t = 2s

Maximum Height (Hmax)

■ The vertical displacement of a projectile during time of ascent is the maximum height of the projectile.

■ In the equation, 12 (sin), 2 =θyutgt we use

y = H max and t = t a

222 max sin 22 θ ∴== y uu H gg

Key Insights:

■ When θ = 90° 2 max2 = u H g

■ This is equal to the maximum height reached by a body projected vertically upwards.

Horizontal range (R)

■ This is defined as the horizontal distance covered by projectile during its time of flight.

Thus, by definition,

■ Range, R = horizontal velocity × time of flight

i.e., ( ) ( ) 2sin coscos θ =θ=θ RuTuu g

22 sin2 Range, θ ⇒== xyuuu R gg H Range θ

Solved example

25. The ceiling of a long hall is 20 m high. What is the maximum horizontal distance that a ball thrown with a speed of 40 ms–1 can go without hitting the ceiling of the hall (g = 10 ms–2)?

Sol. Here, H = 20 m, u = 40 ms–1. Suppose, the ball is thrown at an angle θ with the horizontal.

Now, 22 sin 2 θ = u H g 2220(40)sin 210 θ ⇒= × or, sin θ = 0.5 or, θ = 30°

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Now, 22 sin2(40)sin60 10 θ×° == u R g 2 (40)0.866138.56cm 10 × = =

Solved example

26. A particle is thrown over a triangle from one end of a horizontal base, and grazing the vertex if falls on the other end of the base. If α and β are the base angles and θ is the angle of projection, prove that tan θ = tan α + tan β

Sol. The situation is shown in the figure. From the figure, we have

tantanα+β=+yy xRx ( ) tantanα+β=yR xRx ........ (i)

But equation of trajectory is tan1 =θ- x yxR ( ) tan θ=yR xRx ........ (ii)

From equations(i) and (ii), tan θ = tan α + tan β

Try yourself:

17. A grass hopper can jump a maximum distance of 1.6 m. It spends negligible time on the ground. How far can it go in 10 seconds?

Ans: 202m = S

Key Insights:

■ For a given speed of projection ‘ u ’, the ranges are equal for angles (a) θ and (90° – θ ) (b) (45° + α ) and (45° – α )

(90°–θ)or θ θ or(90°–θ)

X θ=45

Solved example

27. A cannon and a target are 5.10 km apart and located at the same level. How soon will the shell launched with the initial velocity 240 m/s reach the target in the absence of air drag?

Sol. Here, v0 = 240 ms–1, R = 5.10 km = 5100 m,

g = 9.8 ms–2, α = ?

2 0 sin2α= Rg v ⇒ α = 30° or 60°

Using =T = 0 2sin α v g

2 0sin2α = v R g

When, α = 30°, T1 = 22400.5 9.8 ×× = 24.5 s

When, α = 60°, T2 = 22400.867 9.8 ×× = 42.41 s

Try yourself:

18. A cannon ball is fired making on angle of 30° with horizontal. The cannon ball hits a target on ground after 4 second, when the cannon ball is fired with same velocity making a different angle with horizontal, it hits the same target after time T. Find T.

Ans: seconds43

■ Velocity of the Projectile at Any Instant (t): The horizontal component of the projectile remains constant all the time. (because acceleration due to gravity has no component along the horizontal)

■ ∴ Horizontal component of velocity after any time t is v x = u x = u cos θ

■ Vertical component of velocity after any time t is v y = u y – gt = u sin θ – gt ( ) ˆˆ xy vvivj =+ ( ) ˆˆ cossin vuiugtj =θ+θ

■ Then, the magnitude of resultant velocity after time t is ( ) ( ) 2222 cossin xy vvvuugt =+=θ+θ-

■ The velocity vector v makes an angle α with the horizontal, given by tan1 y x v v α= at this instant. v vx vy y x α

■ At any vertical displacement ‘h’, velocity is ( ) ˆ22ˆcossin2 vuiughj =θ+θ

Solved example

28. The velocity of a projectile when at its greatest height is 2 5 of its velocity when at half of its greatest height. Find the angle of projection

Sol. Step 1: We know that, velocity of a projectile at half of maximum heigh = 2 1cos 2 +θ u

Step 2: Given that 2 21cos cos 52 +θ θ=× uu Squaring on both sides,

Try yourself:

19. A particle is prohected with velocity 10 m/s making an angle of 30° with horizontal. Find its velocity vector at t = 1 second.

Key Insights:

■ The horizontal component of velocity remains constant all along (since acceleration due to gravity has no component along the horizontal).

■ The vertical component of velocity

goes on decreasing during the ascent

goes on increasing during the descent

becomes zero at the highest point

■ Velocity of a projectile is maximum at projection point (equal to u) and velocity of the projectile is minimum at highest point (equal to u cos θ ).

■ Change in the velocity of the projectile is equal to 2u sin θ

Solved example

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

29. A particle is projected from the ground with an initial speed v at an angle θ with the horizontal. The average velocity of the particle between its point of projection and highest point of trajectory is

Sol. Y

■ Similarly, change in momentum = 2musin θ

■ Average velocity of the projectile during the entire journey

totaldisplacementrange totaltimetimeofflight

Try yourself:

20. A particle is projected with 10 m/s. Its velocity at the highest point is 5 m/s. Find its average velocity during the time of flight. Ans: 5 m/s

Key Insights:

■ Angle between velocity and acceleration of a projectile

is between 90° to 180° during the ascent, i.e., the dot product of velocity and acceleration is –ve during the ascent

is between 0° to 90° during the descent, i.e., the dot product of velocity and acceleration is +ve during the descent

is 90° at the highest point, i.e., the dot product of velocity and acceleration is 0 at the highest point

■ At the projection point, total energy 12 2 == to Emu (i.e., it is purely kinetic)

■ At the highest point of the projectile

kinetic energy 1222 coscos 2 =θ=θ kto EmuE

potential energy

sinsin 2 =θ=θ pto EmuE

ratio of potential to kinetic energies = 2 tan =θ p k E E

Solved example

30. Projectile of 2 kg was travelling with velocities

3 m/s and 4 m/s at two points during its flight in the uniform gravitational field of the earth. If these two velocities are ⊥ to each other then what is the minimum KE of the particle during its flight is

Sol.

Try yourself:

21. A particle is projected with velocity u making angle α with horizontal. Find its height when its kinetic energy is equal to its potential energy.

Ans: u/42g

Key Insights:

■ If ‘T’ is the time of flight of a projectile, maximum height, 12 8 = HgT |

Proof: We know that

Tu

■ For a projectile, angle of projection [ θ ], range [R] and maximum height [H] are related as

Proof: Maximum height, 22 sin 2 θ = u H g .....(1)

Range, 2sin2θ = u R g .....(2) ( ) ( ) 22 22 22 2 1sin 22sin sin 22sincos θ ⇒× θ θ =× θθ ug gu ug gu tan4 tan 4 θ ⇒=⇒θ=HH RR

■ The time of flight (T), range (R), and angle of projection ( θ ) are related as, (gT2 = 2R tan θ )

Proof: 2sin θ = Tu g .........(1) and 2sin2θ = u R g ........(2) ( )2222 22 14sin (2)sin2 θ ⇒=× θ Tug Rgu ( ) 22 22 4sin 2sincos θ =× θθ ug gu 2 2tan22tan θ ⇒=⇒=θ T gRgTR

■ tan412 2 θ== RHgT

■ Range of a projectile is maximum when angle of projection = 45° ( 2sin2 , u R g θ =

R is maximum if sin 2 θ is maximum, i.e., if 2 θ = 90° or θ = 45°)

■ Range of a projectile = maximum height if θ = tan–1 4 = 76°

Proof: We know that 4 tan θ= H R . From this, 1 tan4tan476=⇒θ=⇒θ==°RH

■ For projectile, in the case of complimentary angles:

a) Ranges are same

Proof: If θ and (90°– θ ) are angles of projection, we have ( ) 22 12 sin2sin290 and uu RR gg °-θ θ = = ( ) 22 12 12 sin2sin1802 and uu RR gg RR °-θ θ ⇒= = ⇒=

b) If H1, H2 are maximum heights, H1 + H2 = 2 2 u g

Proof: We have, 22 1 sin 2 θ = u H g , ( ) 22 2 sin90 2 u H g °-θ = 2222 12 sincos 22 θθ +=+ uu HH gg 2 122∴+= u HH g

c) 1212 4 === RRRHH

d) If T1, T2 are times of flight, T1 T2 = 2 R g

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Proof: We have 12 2sin2sin(90) and uuTT gg θ °-θ = = 2 122 4sincosθθ ⇒=TTu g 2 2 2sin2θ = u g 1212 21 2 R TTRgTT g ⇒=∴=

■ If horizontal and vertical displacements of a projectile are, respectively, x = at and y = bt – ct 2 , then velocity of projection 22=+ uab and angle of projection

tan1 - θ= b a

■ For a projectile, ‘y’ component of velocity at half of maximum height = sin 2 θ u

By app lying, v 2 – u 2 = 2 as, for upwa rd journey of a projectile, we have, u = u sin θ , a = –g, 2211sin 222 θ == u SH g

Substituting these values, we get ( ) 22221sin sin2 22 θ -θ=-×× u vug g 2222

222sinsin sin 22 ∴=θ-=θθ uu vu sin 2 θ ⇒= u v

■ Velocity of a projectile at half of maximum height = 2 1cos 2 +θ u

Velocity at any instant is 22=+ xy vvv

θ ∴=θ+

But v x = u x = u cos θ at any point while, sin 2 θ = y u v (at half of maximum height) ( ) 2 2sin cos 2

u vu

Simplifying, we get,

2 1cos 2 +θ = vu

■ For a projectile, Y = Ax – Bx2

i) Range, = A R B

ii) Max height, 2 4 = A H B

iii) Angle of projection θ = tan–1 (A)

■ =+ uxiyj ( i along horizonal, j along vertical)

222 ,, 2 === yyxyHTR ggg

■ =++

uaibjck [ i -east, j -north, k -vertical]

22=+ x uabu y = c ( ) 22 222 ;, 2 + === abc cc THR ggg

■ The physical quantities that remain constant during projectile motion are

acceleration due to gravity, g

total energy, 2 0 1 2 = Emu

horizontal component of the velocity u cos θ

■ The physical quantities that change during projectile motion are

speed

velocity

linear momentum

KE

PE

Key Insights:

■ A particle is projected up from a point at an angle with the horizontal. At any time ‘t’, if p = linear momentum, y = vertical displacement and x = horizontal

displacement, then the kinetic energy (K) of the particle plotted against these parameters can be:

K-y graph:

From conservation of mechanical energy, K = K c – mgy ............(1)

(Here, Kc= initial kinetic energy = constant) i.e, K-y graph is a straight line. K Y

■ It first decreases linearly, becomes minimum at highest point, and then becomes equal to Kc in a similar manner.

■ Therefore K-y graph will be as shown in the figure.

■ K-t graph: Equation (1) can be written as 12 2

iy KKmgutgt K t

i.e, K-t graph is a parabola.

Kinetic energy first decreases and then increases.

K-x graph: Equation (1) can also be written as K x 2 2 tan 2

i x KKmgxgx u

Again, K-x graph is a parabola.

K-p2 graph:

Further, p2 = 2Km

i.e., p2 ∝ K or, K versus p 2 graph is a straight line passing through the origin.

■ In a projectile motion, let v x and v y be the horizontal and vertical components of velocity at any time t and x and y be displacements along the horizontal and vertical from the point of projection at any time t. Then,

vy-t graph is a straight line with negative slope and positive intercept (v y = u sin θ – gt)

x-t graph is a straight line passing through the origin ( x = u cos θ t)

y-t graph is a parabola.

vx-t graph is a straight line parallel to time-axis (v x = u cos θ )

■ If air resistance is taken into consideration then

trajectory departs from parabola

time of flight may increase or decrease

the velocity with which the body strikes the ground decreases

maximum height decreases

striking angle increases

range decreases

■ A projectile is fired with a speed u at an angle θ with the horizontal. Its speed when its direction of motion makes an angle α with the horizontal v = u cos θ sec α

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

■ Explanation: Horizontal component of velocity remains constant.

∴ v cos α = u cos θ

v = u cos θ sec α

■ A body is dropped from a tower. If wind exerts a constant horizontal force, the path of the body is a straight line.

■ The path of projectile as seen from another projectile:

x1 = u1 cos θ 1t 2 111 1 sin 2 =θyutgt

x2 = u2 cos θ 2t 2 22 1 sin 2 =θyutgt

( ) 1122 coscos ∆=θ-θ xuut

( ) 1122 sinsin ∆=θ-θ yuut 1122 1122 sinsin coscos θ-θ ∆ = ∆θ-θ yuu xuu

If u1 sin θ 1 = u2 sin θ 2 i.e., initial vertical velocities are equal, then, slope = 0 ∆ = ∆ y x

⇒ The path is a horizontal straight line.

If u1 cos θ 1 = u2 cos θ 2, i.e., initial horizontal velocities are equal , then, slope = ∆ =∞ ∆ y x

⇒ The path is a vertical straight line.

u1 sin θ 1 > u2 sin θ 2 u1 cos θ 1 > u2 cos θ 2 ⇒ The path is a straight line with +ve slope.

u1 sin θ1 > u2 sin θ2 ; u1 cos θ1 < u2 cos θ2 or, u1 sin θ 1 < u2 sin θ 2 ; u1 cos θ 1 > u2 cos θ 2

⇒ The path is a straight line with –ve slope.

■ Two bodies that are thrown with the same speed from the same point at the same instant, but at different angles, can never collide in air.

■ (x = u(cos θ) t, y = u(sin θ) –1 2 gt2; x and y coordinates always differ)

■ A body is projected up with a velocity u at an angle θ to the horizontal from a tower of height h, as shown. It is clear that such a body also traces a parabolic path.

■ The time taken to reach ground is obtained as explained below. usin θ ucos θ u θ

Try yourself:

22. A particle is projected from the top of a tower of height 50 m with velocity 10 m/s making an angle of 60° with horizontal. Find the maximum height attained by the ball above the ground. Take g = 10 m/s 2 . Ans: 53.75 m

■ A body is projected down with a velocity u at an angle θ to the horizontal from a tower of height h, as shown. It is clear that such a body traces a parabolic path. The time taken to reach ground is arrived, as explained below.

■ The components of velocity are as shown.

■ Here, the body can be treated as a body projected vertically upwards with a velocity u sin θ from a tower of height h. Hence, the equation of motion on reaching the foot of the tower is

2 =-θ+ hutgt by using the formula for height of tower.

Solved example

31. A ball is thrown from the top of a tower 61 m high, with a velocity 24.4 ms –1 at an elevation of 30° above the horizontal. What is the distance from the foot of the tower to the point where the ball hits the ground? Sol. usin θ ucos θ

■ The components of velocity are as shown. Here, the body can be treated as a body projected vertically downwards, with a velocity u sin θ from a tower of height h. Hence, the equation of motion on reaching the foot of the tower is (sin)12 2 =θ+ hutgt

121 (using1,wheresin) 2 Sutgtuu =+=θ

Solved example

32. A particle is projected from a tower, as shown in the figure. Find the distance from the foot of the tower to where it will strike the ground. (g = 10 m/s2)

150050032 5 35 =×+tt

⇒ 300 = 20t + t2

On solving, t = 10 s

∴ Horizontal distance = u cos θ T

50044000 10m 353 =××=

Try yourself:

23. A particle is projected from the top of a tower making on angle of 30° with horizontal in the downward direction. Height of the tower is 100 m. If the particle hits the ground after 4s, find the velocity of projection

Ans: 10 m/s

Application

■ Motion of a Projected Body on an Inclined Plane: A body is projected up the inclined plane from the point O with an initial velocity v0 at an angle θ with the horizontal.

■ The inclined plane OA is inclined at an angle α with the horizontal. The projectile is fired from the bottom of the inclined plane upwards with velocity u and making an angle α with the horizontal.

■ The initial velocity of the projectile is resolved along and perpendicular to the plane. Similarly, the acceleration due to gravity g is also resolved along and perpendicular to the inclined plane.

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Acceleration along x-axis, a x = –g sin α

Acceleration along y-axis, a y = –g cos α

Component of velocity along x-axis, u x = u cos ( θ – α )

Component of velocity along y-axis, u y = u sin ( θ – α )

■ Let T be the time of flight along the inclined plane.

■ When the projectile is at A, s y = 0.

0sin()(cos) 2 =θ-α+-α uTgT

2sin() cos θ-α = α Tu g

■ Horizontal distance OB covered by the projectile, OB = (u cos θ )T (cos)2sin() cos θ-α =θ α u u g

2 2cossin() cos θθ-α = α u g

■ In the right angled triangle OAB, cos α= OB OA cos = α OB OA

Therefore, 2 2 2cossin() cos θθ-α = α u OA g

2 22cossin() cos = θθ-α α u g

Using the formula,

2 cos A sin B = sin(A + B) – sin(A – B) we get,

2 2[sin(2)sin] cos = θ-α-α α u OA g

Solved example

33. A projectile has the maximum range of 500 m. If the projectile is now thrown up making 60° with horizontally on an inclined plane of inclination 30° with the same speed. What is the distance covered by it along the inclined plane?

Sol. 2 max = u R

Try yourself:

24. A particle is projected horizontally with a speed ‘ u’ from the top of a plane inclined at an angle ‘θ ’ with the horizontal. How far from the point of projection will the particle strike the plane?

Ans: 22 tansec u g θθ

3.10.3 Horizontal Projection from the Top of a Tower

■ Suppose a body is projected horizontally with an initial velocity u from the top of a

tower of height ‘h’ at time t = 0. As there is no horizontal acceleration, the horizontal velocity remains constant throughout the motion.

■ Hence after time t, the velocity in horizontal direction will be v x = u.

■ Let the body reach a point ‘ P ’ in time t Let x and y be the coordinates of the body.

For the y-coordinate, after time t seconds, 22

For the x-coordinate, after t seconds, x = ut ( the horizontal velocity is constant) ⇒= x t u ............ (2)

From equations (1) and (2), we get 2 2 2

g and u being constants, 22

g u is a constant.

If 22 = gk u then y = kx2

■ This equation represents the equation of a parabola.

Solved example

34. Two paper screens A and B are separated by a distance of 100 m. A bullet pierces A and then B. The hole in B is 10 cm below the hole in A. If the bullet is travelling horizontally at the time of hitting the screen A, calculate the velocity of the bullet when it hits the screen A. Neglect the resistance of paper and air.

Sol. The situation is shown in the figure.

0.1m R u Q P x A B 100m

Try yourself:

25. A body is projected horizontally with a velocity 10 m/s from the top of a tower of height 80 m. Find its range on horizontal ground. Ans: 40 m

3.10.4 Motion Parameters of a Horizontal Projectile

■ Let us discuss the motion parameters of horizontal projectile.

■ Time of Descent: It is the time the body takes to touch the ground after it is projected from the height ‘ h’.

For y = h and t = td we get

2 12 2 =∴= dd hgtth g

■ The time of descent is independent of initial velocity with which the body is projected, and it depends only on the height from which it is projected.

Range

■ The maximum horizontal distance travelled by the body while it touches the ground is called range ( R). It is shown as AB in the figure.

■ As the horizontal velocity is constant,

■ Range = horizontal velocity × time of descent

R= (u)td.

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

But, ( ) 22 =∴= d hh tRu gg

■ Velocity of the Projectile at Any Time ( t)

■ Let the body be at point P after the time t.

■ Let v x and v y be velocities along x-and y-directions.

■ The horizontal velocity remains constant throughout the motion. Hence v x = u

■ The velocity along y-axis is

■ v y = u y + gt and u y = 0 as the body is thrown horizontally initially.

So, the magnitude of the velocity 22222=+=+ xy Vvvugt

■ If velocity vector v makes an angle α with the horizontal, then tan1 (or)tan -

y x vgtgt vuu

Key Insights:

■ For an easier understanding, we consider that, motion of horizontal projectile = motion in y-direction (like a freely falling body) + motion in x-direction with constant velocity.

Application

■ If a body projected horizontally with velocity u from the top of a tower strikes the ground at an angle of 45°,

V y = V x, gt = u ∴= u t g

■ A body is projected horizontally fro m the top of a tower. The line joining the point of projection and the striking point make an angle of 45° with the ground. Then, h = ut

450 u h x

12 2 = gtut

2 = u t g

■ A body is projected horizontally from the top of a tower. The line joining the point of projection and the striking point make an angle of 45° with the ground. Then, the displacement 2=2hX =

450 u h x A B C

■ From the figure, tan451°==⇒=hhX X

∴ displacement, AC ( ) ( ) 22 =+ABBC

222=+=hHh (or) 2(since) = XhX

■ Two towers having heights h 1 and h 2 are separated by a distance ‘d’. A person throws a ball horizontally with a velocity u from the top of the 1 st tower to the top of the 2nd tower, then

Time taken, ( ) 212= hh t g u h1 h2 d (h1-h2)

■ Distance between the towers, ( ) 212== hh dutu g

■ An aeroplane flies horizontally with a velocity ‘ u ’. If a bomb is dropped by the pilot when the plane is at a height ‘h’, then

the path of such a body is a vertical straight line, as seen by the pilot

the path is a parabola as seen by an observer on the ground

the body will strike the ground at a certain horizontal distance. This distance is equal to the range given by 2 == h xutu g

■ A ball rolls off the top of a staircase with a horizontal velocity u . If each step has height h and width b, then the ball will just hit the nth step if,

35. A staircase contains three steps, each 10 cm high and 20 cm wide, as shown in the figure. What should be the minimum horizontal velocity of a ball rolling off the uppermost plane so as to hit directly the edge of the lowest plane? [g = 10 m/s2]

Try yourself:

26. Two particles move in a uniform gravitational field with an acceleration ‘ g ’. At the initial moment, the particles were located at the same point and moved with velocities u 1 = 0.8 ms –1 and u 2 = 4.0 ms –1 horizontally, in opposite directions. Find the distance between the particles at the moment when their velocity vectors become mutually perpendicular. (g = 10 ms–2)

CHAPTER 3: Motion in a Plane

Hint: 12 12,()==+ uu txuut g

Ans: 0.8586 m

Key Insights:

■ From the top of a tower, one stone is thrown towards East with velocity u1 and another is thrown towards North with velocity u 2 . The distance between them after striking the ground